Abstract

Eucommia ulmoides, a tree species native to China, holds considerable medicinal, ecological, and industrial importance. However, the absence of an efficient and stable genetic transformation system poses significant challenges to gene function studies and molecular breeding in E. ulmoides. Protoplasts, which lack cell walls, serve as effective receptors for transient transformation and are thus ideal for genetic engineering research. In this study, the optimal conditions for callus induction were identified, and formation of the embryogenic callus was confirmed by histological analysis. Furthermore, we developed an efficient protoplast isolation and PEG-mediated transient transformation system using suitable embryogenic callus as the starting material. Our findings revealed that the optimal medium for inducing embryogenic callus was B5 + 1.5 mg/L 6-BA + 0.5 mg/L NAA + 30 g/L sucrose + 7 g/L agar (pH = 5.8). In this medium, the induction rate of callus achieved 97.50%, and the rate of embryogenic callus formation was 86.30%. For protoplast isolation, the best conditions involved enzymatic digestion with 1.5% cellulase R-10 and 1.0% macerozyme R-10 at an osmotic pressure of 0.6 M for 4 h, resulting in 1.82 × 106 protoplasts/g FW with 91.13% viability. The highest transfection efficiency (53.23%) was attained when protoplasts were cultured with 10 µg of plasmid and 40% PEG4000 for 20 min. This study successfully established a stable and efficient system for protoplast isolation and transient transformation in E. ulmoides, offering technical support for exploring somatic hybridisation and transient gene expression in this species.

1. Introduction

Eucommia ulmoides Oliv., a distinctive economic tree species native to China, holds considerable medicinal, ecological, and industrial significance [1,2]. The bark and leaves of E. ulmoides are abundant in bioactive compounds like iridoids, lignans, and flavonoids, which have impressive pharmacological properties, including anti-inflammatory effects, blood pressure regulation, and bone metabolism modulation [3,4,5]. In the industrial sector, Eu-rubber stands out as a unique bio-based polymer resource in China, emerging as a natural polymer material. Predominantly found in the bark, stems, leaves, seeds, and other tissues of E. ulmoides [6,7], this polymer offers a strategic alternative to natural rubber [3,8]. Furthermore, E. ulmoides demonstrates robust tolerance to abiotic stresses such as cold and drought, making it a valuable model for exploring stress resistance mechanisms and secondary metabolism regulation in woody plants [9,10,11].

Plant protoplasts, which are plant cells stripped of their cell walls through enzymatic processes, retain their regenerative ability, viability, and metabolic activity [12]. They are crucial for plant fundamental research and serve as invaluable tools for enhancing crop genetics [13]. Protoplasts can be isolated from various plant tissues, such as leaves, cotyledons, petals, roots, hypocotyls, suspension-cultured cells, and callus [14]. Notably, using actively growing and young tissues for isolation results in protoplasts with higher yields and improved viability [15]. Plant embryogenic callus, characterised by dense cytoplasm, prominent nuclei and active cell division, is particularly well-suited for protoplast isolation [16]. Furthermore, embryogenic callus is preferable for enzymatic digestion due to its relatively thin cell walls and low levels of lignification and secondary metabolites like polyphenols and polysaccharides, resulting in a higher yield and viability of protoplasts compared to non-embryogenic callus [17,18,19,20]. The protoplasts derived from embryogenic callus are more apt for transient transformation and gene function studies, laying the groundwork for plant regeneration and genetic transformation research [21]. Consequently, this study selected embryogenic callus as the source material for protoplast isolation, with systematic optimisation of the isolation conditions.

Plant protoplasts offer a versatile tool for studying gene functions, such as subcellular localisation, protein interactions, and genome editing, and can also act as intermediaries in generating stable transgenic plants [22,23]. By employing transient plasmid transfection, protoplasts can swiftly express foreign genes, facilitating rapid functional verification. Given that Agrobacterium-mediated stable transformation is expensive, time-intensive, and technically challenging, the protoplast transient transfection system presents a rapid, adaptable, and cost-effective alternative for plant molecular research [24,25,26]. Furthermore, protoplasts serve as efficient explants for quick gene function assays, as transfected plasmids are promptly expressed within the cells, allowing for immediate evaluation of gene activity. Subcellular localisation analysis, which identifies the intracellular distribution of gene products, is a prevalent method for functional verification [27,28,29]. Transient transfection systems have been successfully implemented in various plant species, including Arabidopsis [30,31], rice [14], maize [32], wheat [33,34], soybean [35,36], and strawberry [37], to facilitate subcellular localisation studies. Previous studies on woody plants such as Cunninghamia lanceolata [38], poplar [39,40], grape [41,42], citrus [27,43], walnut [23], and Camellia oleifera [44,45,46] have shown that optimising enzyme composition, digestion time, osmotic pressure, and pretreatment conditions can significantly improve protoplast yield and viability. These findings provide valuable insights for developing efficient protoplast systems in woody species.

In woody species, the thick cell walls and high concentrations of secondary metabolites, such as polyphenols and polysaccharides, render cells susceptible to damage and complicate the maintenance of viability during protoplast isolation. As a result, yields tend to be low, and a robust isolation system remains elusive. Based on the aforementioned research background, this study seeks to achieve a high yield and viability of protoplasts derived from the embryogenic callus of E. ulmoides, while also establishing an efficient protoplast transient transformation system. Initially, the hypocotyl was utilised as an explant to investigate the impact of varying concentrations of 6-BA and NAA on the callus induction rate, alongside a microscopic examination of tissue sections to elucidate the embryogenic callus type. Subsequently, employing the embryogenic callus as the substrate, different enzyme concentrations, digestion durations, and centrifugation speeds were investigated to ascertain the optimal conditions for isolating and purifying protoplasts. Lastly, the influence of various plasmid and PEG4000 concentrations, along with transformation durations, on protoplast transformation efficiency was evaluated to establish a proficient protoplast transient transformation system. This study can offer robust technical support for somatic hybridisation and fusion, as well as for the subcellular localisation and transient expression of functional genes in E. ulmoides, providing valuable resources for functional genomics research and molecular breeding within this species.

2. Results

2.1. Embryogenic Callus Induction and Cytological Identification

A two-factor, five-level full factorial L25 experimental design was utilised to formulate media for callus induction from the hypocotyl. The results indicated that all 25 treatments successfully induced callus, with induction rates exceeding 80% in every instance. Remarkably, 12 combinations achieved induction rates above 95%, and two treatments reached a perfect 100% induction rate (Table 1). Analysis of variance revealed that both the main effects and the interaction between 6-BA and NAA concentrations on the callus induction rate were highly significant (p < 0.001), with 6-BA exerting the most substantial influence (F = 69.969, p < 0.001). Generally, low concentrations of 6-BA, when paired with appropriate NAA levels, enhanced callus induction rates. In contrast, at high 6-BA concentrations, increasing NAA was inhibitory. During the formation of callus in E. ulmoides, the colour and texture of explants undergo significant changes. In type I, the explants exhibited a yellow color, no obvious protrusions, and a loose texture with a water-soaked appearance (Figure 1A). In type II, the colour shifted to light green, and the texture became dry and firm with no discernible protrusions (Figure 1B). In type III, the explants turned bright green and maintained a dry and firm texture with spherical protrusions (Figure 1C). The results indicated that various combinations of 6-BA and NAA concentrations significantly influence the state of callus on the 30th day.

Table 1.

Impact of various 6-BA and NAA concentration combinations on callus induction rate in E. ulmoides.

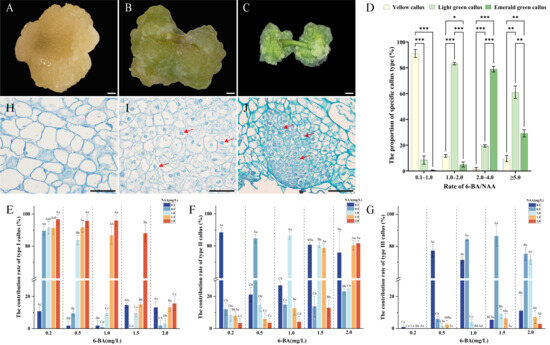

Figure 1.

Effect of hormone ratios on callus type induction and morphological and cytological observations of callus in E. ulmoides. (A) Type I callus, scale bar = 1 mm (the same for (B,C)); (B) type II callus; (C) type III callus; (D) the proportion of three callus types under varying 6-BA/NAA ratios, in which “*”, “**”, “***” denote significant differences at p < 0.05, p < 0.01, and p < 0.001, respectively. (E–G) Effects of different 6-BA and NAA concentration combinations on the contribution rates of type I, II, and III callus, different uppercase letters indicate significant differences among different 6-BA concentrations at the same NAA concentration (p < 0.05), while different lowercase letters indicate significant differences among different NAA concentrations at the same 6-BA concentration (p < 0.05). (H–J) Histological observations of type I, II, and III callus under a light microscope, scale bar = 100 µm, red arrows highlight the nuclei.

The ratio of cytokinin to auxin is crucial in regulating callus formation, prompting an analysis of the effect of 6-BA/NAA ratio on callus induction rates. The findings revealed significant variations in the proportion of three callus types under different 6-BA/NAA ratios (Figure 1D). At a ratio of 0.1–1.0, it was mostly type I callus, comprising 91.1%, while type II and type III callus were lower, at 8.5% and 0.4%, respectively. When the ratio increased to 1.0–2.0, type II callus became predominant at 83.3%, with type I and type III at 11.6% and 5.1%, respectively. A ratio of 2.0–4.0 primarily was type III callus (79.0%), while type II and type I were less frequent at 19.5% and 1.5%, respectively. When the ratio exceeded 5.0, the proportions of the three callus types were 9.7% for type I, 61.1% for type II, and 29.2% for type III. Subsequently, the contribution rate of each medium to the three callus types was analysed further. Type I callus was most prevalent in the combination of low-concentration 6-BA (0.2–1.0 mg/L) and high-concentration NAA (1.5–2.0 mg/L), with the highest contribution rate of 96.7% achieved at 0.2 mg/L 6-BA + 2.0 mg/L NAA (Figure 1E). Type II callus primarily depended on the ratio of 6-BA and NAA, exhibiting the highest quantity at a ratio of 1.0, with a maximum contribution rate of 88.4% observed in the medium containing 0.2 mg/L 6-BA and 0.2 mg/L NAA (Figure 1F). Type III callus required a 6-BA concentration of 0.5 mg/L or higher, and a relatively low NAA concentration (0.2–0.5 mg/L). The highest contribution rate of type III was 86.3% with 1.5 mg/L 6-BA + 0.5 mg/L NAA (Figure 1G).

To accurately identify embryonic callus for protoplast isolation, the three callus types were processed into permanent paraffin sections for histological observation. The analysis revealed significant differences in their cellular structures. The cells of type I callus were varied in size, irregularly shaped, loosely arranged, and had fewer nuclei, which exhibited the characteristic of non-embryogenic callus (Figure 1H). The cells of type II callus were more uniform, regularly shaped, relatively compact, and clearly visible nuclei, which exhibited the characteristics of embryogenic callus (Figure 1I). However, the nucleo-cytoplasmic ratio of type II callus is relatively low, making it unsuitable as a material for protoplasts. In contrast, type III callus cells were densely packed, orderly, with large, distinct nuclei and a high nucleo-cytoplasmic ratio, which was typical of embryogenic callus and more suitable for protoplasts (Figure 1J).

Consequently, hypocotyls from 15-day-old sterile E. ulmoides seedlings served as explants. And cultured on a medium comprising B5 + 1.5 mg/L 6-BA + 0.5 mg/L NAA + 30 g/L sucrose + 7 g/L agar, (pH = 5.8), for 30 days. The resulting emerald green callus was then utilised for protoplast isolation.

2.2. Optimisation of Protoplast Isolation System from Embryogenic Callus

Based on 30-day embryogenic callus, different concentrations of cellulase R-10 and macrozyme R-10, and various enzyme digestion times were set to evaluate their effects on protoplast yield and viability. The range analysis reveals that these three factors exert differing levels of influence on both yield and viability. Notably, the concentration of cellulase R-10 significantly affected protoplast yield, showing the highest impact (F = 746.046, p < 0.001, R = 0.957). This was followed by enzymolysis time (F = 14.426, p< 0.001, R = 0.130), with macrozyme R-10 having the least effect (F = 8.046, p < 0.001, R = 0.089). Conversely, for protoplast viability, macrozyme R-10 concentration was the most influential factor (F = 124.429, p < 0.001, R = 6.88), followed by cellulase R-10 concentration (F = 60.013, p < 0.001, R = 3.82), while enzymolysis time had the least impact (F = 0.718, p = 0.547, R = 0.50).

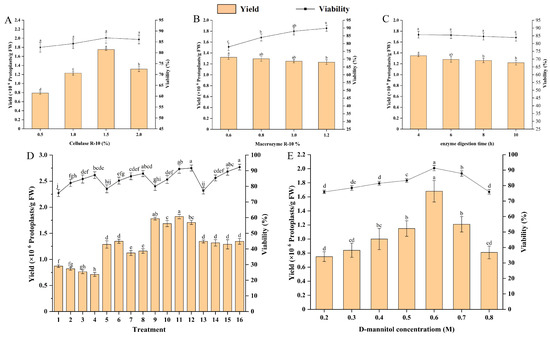

To identify the optimal levels for protoplast isolation factors, we conducted an LSD multiple comparison analysis on yield and viability at each factor level (Figure 2). The finding revealed that a cellulase R-10 concentration of 1.5% yielded the highest protoplast yield and viability (Figure 2A). Interestingly, as the macerozyme R-10 concentration increased, protoplast yield decreased, while viability improved (Figure 2B). Balancing both yield and viability, we determined that a macerozyme R-10 concentration of 1.0% was optimal. Prolonged enzymolysis time led to reduced yield and viability (Figure 2C), indicating that 4 h is the optimal enzymolysis duration. In addition, we performed an orthogonal experiment to comprehensively evaluate the effects of different concentrations of cellulase R-10 and macrozyme R-10, as well as enzymolysis time, on protoplast yield and viability. The findings showed a significant increase in yield up to treatment 11, followed by a sharp decline. Protoplast activity was highest in treatments 16 and 12, standing at 92.30% and 91.73%, respectively, but treatment 11 also exhibited a high level of 91.13%, and there was no significant difference among these treatments (Figure 2D). Consequently, we concluded that treatment 11 offers the optimal conditions for protoplast isolation, involving enzymolysis for 4 h with a combination of 1.5% cellulase R-10 and 1.0% macerozyme R-10.

Figure 2.

Optimisation of protoplast isolation system derived from embryogenic callus in E. ulmoides. (A) Effects of cellulase R-10 concentration on protoplast yield and viability; (B) effects of macrozyme R-10 concentration on protoplast yield and viability; (C) effect of enzymolysis time on protoplast yield and activity; (D) the orthogonal experiment of cellulase R-10 and macerozyme R-10 concentrations as well as enzymolysis time on protoplasts yield and viability; (E) effects of D-Mannitol concentration on protoplast yield and viability. The different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05).

We examined the influence of D-mannitol concentration as an osmotic regulator on protoplast yield and viability. The concentration of D-mannitol significantly affected both yield and viability (p < 0.05). As the D-mannitol concentration increased, protoplast yield and viability improved, peaking at 0.6 M. Beyond this concentration, both yield and viability notably declined (Figure 2E). Thus, 0.6 M D-mannitol was identified as the optimal concentration for protoplast isolation.

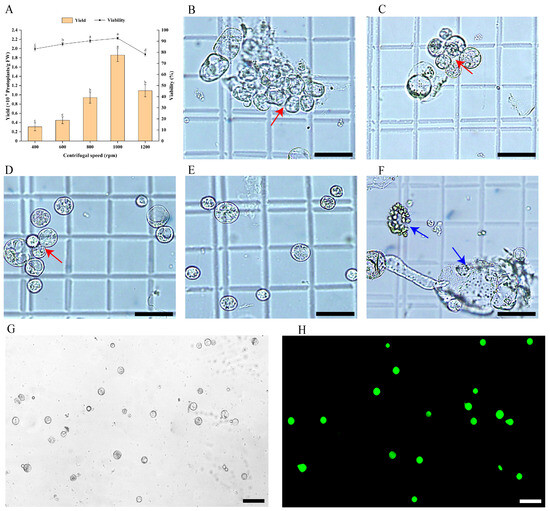

2.3. Optimisation of Protoplast Purification Conditions

To collect protoplasts and eliminate impurities such as non-enzymolysis substances, cell debris, and shrunken cells, the enzymatic mixture was filtered twice through a 70 μm cell sieve and subsequently centrifuged at varying speeds. The results indicated that centrifugal speed significantly affected both the yield and viability of protoplasts (p < 0.05), as well as their morphology (Figure 3). At 400 rpm, the protoplast yield was minimal, viability was poor, and most protoplasts clustered together (Figure 3A,B). Similarly, at 600 rpm, yield and viability remained low, with many protoplasts interconnected (Figure 3A,C). However, at 800 rpm, both yield and viability improved markedly, although the protoplasts were unevenly dispersed in the W5 solution (Figure 3A,D). The optimal results were achieved at 1000 rpm, yielding the highest protoplast count (1.82 × 106 protoplasts/g FW) and viability (92.13%), with protoplasts exhibiting complete morphology and even distribution (Figure 3A,E). Post-FDA staining, they displayed strong fluorescence and uniform staining, indicating high vitality and good physiological condition (Figure 3G,H). Conversely, increasing the speed to 1200 rpm resulted in a significant decline in yield and viability, with many protoplasts rupturing due to excessive centrifugal force (Figure 3A,F). Consequently, 1000 rpm was identified as the optimal centrifugation speed for protoplast purification.

Figure 3.

Effect of centrifugal speed on protoplast purification in E. ulmoides. (A) Protoplast yield and viability at different centrifugal speeds, in which different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05). (B) Microscopic morphology of protoplasts at 400 rpm, scale bar = 50 µm (the same as (C–F)). (C) Microscopic morphology of protoplasts at 600 rpm. (D) Microscopic morphology of protoplasts at 800 rpm. (E) Microscopic morphology of protoplasts at 1000 rpm. (F) Microscopic morphology of protoplasts at 1200 rpm. (G,H) Observation of the morphology of protoplasts under bright field and 488 nm excitation light using a fluorescence microscope after FDA staining, scale bar = 75 µm. Notes: Red arrows indicate aggregated protoplasts (in (B–D)). The blue arrow represents the damaged protoplast (in (F)).

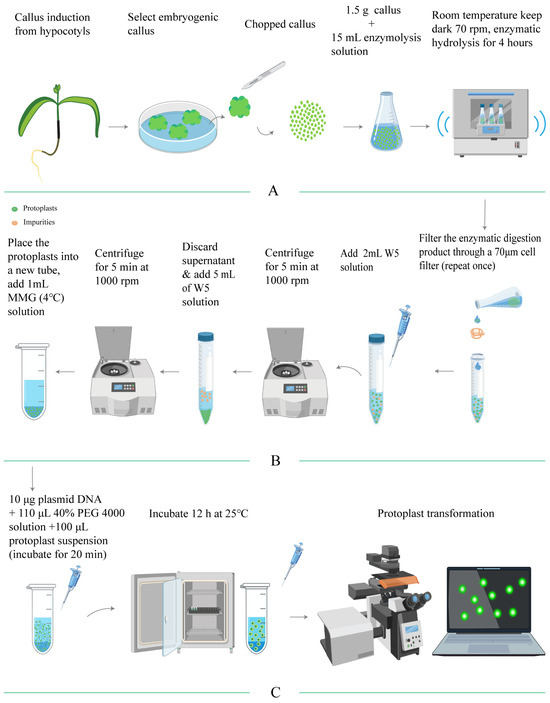

In conclusion, we have established an experimental protocol for isolating and purifying protoplasts from the embryogenic callus of E. ulmoides, which is illustrated in a flowchart (Figure 4). According to this protocol, protoplasts with a yield of 1.82 × 106 protoplasts/g FW and a viability of 91.13% could be obtained.

Figure 4.

Flowchart detailing the processes of protoplast isolation, purification, and transient transformation in E. ulmoides. (A) outlines the method for isolating protoplasts; (B) describes the purification process; (C) presents the method for transient transformation of protoplasts.

2.4. Optimisation of Protoplast Transient Transformation System

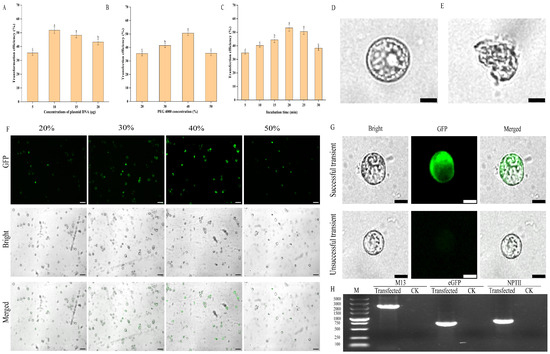

To develop an efficient protoplast transient transformation system for E. ulmoides, we assessed the influence of plasmid concentration, PEG4000 concentration, and transformation duration on transformation efficiency. Our findings revealed that the optimal transformation efficiency (51.87%) was achieved with a plasmid concentration of 10 μg. Variations in plasmid concentration, either higher or lower, significantly reduced the transformation rate (Figure 5A), and excessive plasmid levels caused visible damage to protoplasts (Figure 5D,E). Furthermore, PEG4000 concentration markedly affected the transformation rate. The optimal transformation rate of 50.63% was observed at a PEG4000 concentration of 40% (Figure 5B). Lower PEG4000 concentrations were not favourable for transient transformation, whereas higher concentrations increased protoplast rupture, thereby diminishing the transformation rate (Figure 5F). Regarding transformation time, efficiency improved with increased duration, peaking at 20 min with a rate of 53.23%. Insufficient transformation time led to inadequate contact between the plasmid and protoplasts, resulting in incomplete transformation. Conversely, extending the duration beyond 20 min caused protoplast damage, reducing the transformation rate (Figure 5C). In summary, the optimal conditions for protoplast transient transformation in E. ulmoides involve using 10 μg of plasmid with 40% PEG4000 for 20 min, achieving a transformation rate of 53.23%. The transformation process is illustrated in Figure 4C.

Figure 5.

Effects of various factors on protoplast transformation efficiency in E. ulmoides. (A) The effect of plasmid concentration on transformation efficiency. (B) The effect of PEG4000 concentration on conversion efficiency. (C) The effect of incubation time on transformation efficiency. (D) Protoplasts with complete structure, scale bar = 20 µm (the same for (E,G)). (E) Morphologically damaged protoplasts. (F) Observation of protoplast transformation under different PEG4000 concentrations by fluorescence microscope, scale bar = 100 µm. (G) Observation of successfully and unsuccessfully transformed protoplasts by fluorescence microscopy. (H) Detection of the presence of pCAMBIA3301 plasmid fragment, eGFP and NPT II in protoplasts transformed with pCAMBIA3301-35S-eGFP by PCR, in which CK represents protoplasts without transformation. Note: different lowercase letters indicate significant differences (p < 0.05) in (A–C).

The protoplasts transformed with the pCAMBIA3301-35S-eGFP plasmid maintained their regular morphology and intact cell membranes when observed under a bright-field microscope. Upon excitation at 488 nm, regions expressing the eGFP protein emitted a distinct green fluorescence, whereas the untransformed protoplasts showed no autofluorescence (Figure 5G). Additionally, PCR analysis confirmed the presence of the pCAMBIA3301 plasmid fragment and the eGFP and NPTII genes in the transformed protoplasts, but not in the untransfected ones (Figure 5H). These results indicated that pCAMBIA3301-35S-eGFP plasmid had been successfully introduced into protoplasts, resulting in transient expression.

3. Discussion

E. ulmoides is a valuable woody plant with notable medicinal and industrial applications [47]. Due to its slow growth, research on the regulation and production of its natural metabolites, functional genes, and molecular breeding primarily relies on plant tissue culture techniques [48,49]. Since 1980, numerous studies on tissue culture of E. ulmoides have been reported, investigating various parts such as hypocotyls, cotyledons, leaves, bud-bearing stem segments, and both mature and immature embryos [50,51]. Currently, the exploration and validation of functional genes in E. ulmoides predominantly utilise Agrobacterium-mediated transformation with hypocotyls as explants. However, the incomplete transgenic regeneration system significantly limits the application of functional genes and molecular breeding research [52,53]. Plant protoplasts are living cells without cell walls, can directly absorb exogenous DNA and undergo somatic hybridisation, making them widely used for genetic modification and improvement in plants [54]. Embryogenic callus is generally regarded as an excellent material for protoplast isolation and culture, forming a crucial foundation for developing an efficient protoplast isolation system [46]. Consequently, this study established a system for inducing embryogenic callus from hypocotyls, isolating protoplasts, and implementing PEG-mediated transient transformation in E. ulmoides. This provides a reliable platform for the rapid analysis of gene function and genetic manipulation.

Previous research primarily utilised MS medium combined with 6-BA and NAA to induce callus formation and proliferation in E. ulmoides [50,51]. Wang et al. [55] discovered that B5 medium significantly outperformed MS medium concerning callus growth, average budding rate, and positive bud ratio post-transformation. Therefore, this study employed hypocotyls as explants to examine the effects of varying concentrations of 6-BA and NAA in solid B5 medium on the callus type and embryogenic potential of E. ulmoides. The results showed that all 25 media combinations produced three distinct callus states, differing in colour, shape, and texture (Figure 1A–C). Traditionally, callus embryogenicity was assessed solely based on external characteristics such as colour, shape, and texture [56,57], which posed observational challenges. To address this, we conducted histological observations using the paraffin section technique. In this study, both type II and type III callus exhibited clearly observable nuclei, indicative of embryogenic cells (Figure 1I,J). However, the type III callus has a dense cytoplasm to form a higher nucleo-cytoplasmic ratio, suggesting superior potential for protoplast isolation and purification (Figure 1J). The external morphology of type III callus was described as “bright green, dry and firm texture with spherical protrusions”, aligning with descriptions in existing literature [58,59]. In this study, the average callus induction rates for 12 culture media exceeded 95%. The concentration ratio of 6-BA to NAA significantly influenced callus type. When the ratio ranged from 2.0 to 4.0, the proportion of type III callus was highest. Conversely, at ratios ≥ 5.0, the proportion of embryogenic callus decreased, and direct induction of adventitious buds was observed. Considering the analysis of type III callus proportions, the optimal callus induction medium for E. ulmoides hypocotyls was determined to be B5 + 1.5 mg/L 6-BA + 0.5 mg/L NAA.

High-quality protoplasts are essential for transformation and functional gene analysis [54]. The plant cell wall primarily comprises cellulose and pectin, with compositions varying across species and even within different organs of the same species [60]. Therefore, the enzymatic method for protoplast isolation must be tailored to the specific cell wall components of the plant material in question [23]. The choice and concentration of cell wall-degrading enzymes, along with the enzymolysis duration, are pivotal in optimising protoplast yield and viability [61]. In previous research, a complex enzyme mix (2.5% cellulase R-10, 0.6% macerozyme R-10, 2.5% pectinase, and 0.5% hemicellulase) yielded 1.13 × 106 protoplasts/g FW from young E. ulmoides stems [62]. However, our study demonstrates that a simpler combination of 1.5% cellulase R-10 and 1.0% macerozyme R-10 achieves a higher yield of 1.82 × 106 protoplasts/g FW. This could be attributed to the more intricate cell wall structure of young E. ulmoides stems compared to embryogenic callus. The results suggest that callus is a more suitable material for protoplast isolation, aligning with Russell’s results [63]. Numerous studies indicate that increasing enzyme concentration boosts protoplast yield but diminishes viability [62,64]. Interestingly, our research found that the cellulase R-10 concentration had no significant effect on protoplast viability, while higher macerozyme R-10 concentrations reduced yield but enhanced viability. This may occur because increased macerozyme R-10 concentrations improve cell wall degradation efficiency but also stress cells, causing fragile ones to rupture, leaving behind more resilient protoplasts. Enzymolysis duration varies significantly among plant species and tissues. For instance, isolating protoplasts from sweet cherry pulp takes 18 h [65], while it takes 15 h for extraction from strawberry leaves [25] and 10 h for extraction from young E. ulmoides stems [62]. In contrast, in our study, only 4 h were required for extraction from the embryogenic callus of E. ulmoides, similar to the 3–4 h needed for C. lanceolata callus [66]. This efficiency is likely due to the thinner cell walls of callus, which degrade more readily. A shorter enzymolysis period generally prevents protoplast degradation, facilitating their subsequent use [66]. The protoplast isolation system developed in this study, with its brief enzymolysis time, ensures the protoplasts remain in a good physiological state, providing a solid foundation for further studies on gene function, protein subcellular localisation, and protein interaction.

When protoplasts are devoid of a cell wall, they can contract, expand, or even rupture due to their inability to maintain isobaric conditions with the external environment [62]. To counteract this, an appropriate concentration of D-mannitol is typically added to the enzymatic solution to balance the osmotic pressure. Studies have indicated that a 0.4 M concentration of D-mannitol is optimal for isolating protoplasts in various plants, including poplar, C. lanceolata, and Camellia sinensis [67]. However, both this study and Hu et al. [62] identified that a 0.6 M concentration is necessary for E. ulmoides. This higher requirement is likely due to the elevated solute concentration in E. ulmoides cells, which contain numerous macromolecular substances like Eu-rubber, necessitating a greater concentration of D-mannitol to achieve osmotic balance.

PEG4000 facilitates the uptake of exogenous DNA into protoplasts by altering the physicochemical properties of the cell membrane surface and enhancing membrane permeability. However, its transformation efficiency is influenced by concentration, plasmid dosage, and transformation duration [12,26]. Our study identified that a 40% concentration of PEG4000 optimally supports transformation. Both excessive and insufficient concentrations markedly decrease efficiency, consistent with findings in other plant species [68]. This suggests that approximately 40% PEG4000 strikes an optimal balance between high membrane permeability and low cytotoxicity across various plants, including E. ulmoides. The results of this study indicate that a transformation rate of 53.23% can be achieved with just 10 µg of plasmid for 20 min. This plasmid quantity is notably lower than that required for other species, such as S. spontaneum [13], Camellia yubsienensis [69], and P. aegyptiaca [7]. Additionally, both the plasmid dosage and transformation rate surpass those observed in the transient transformation of protoplasts isolated from young stems [62]. This enhanced efficiency may be attributed to the higher membrane permeability of protoplasts derived from E. ulmoides embryogenic callus at 40% PEG4000. These results underscore the advantages of the protoplasts obtained through this experimental approach for further research in E. ulmoides.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Culture Conditions

The mature seeds come from the well-grown E. ulmoides trees on the campus of Northwest A&F University in Yangling City, Shaanxi Province, China. Mature seeds were removed from their shells and soaked in water for 8 h. They were then washed with a detergent containing a surfactant and thoroughly rinsed under running tap water for 30 min to ensure all residues were eliminated. Subsequently, the seeds were placed on a sterilised ultra-clean table, soaked in 75% (v/v) ethanol for 30 s, and rinsed 1–2 times with sterile water. Following this, they were immersed in 10% NaClO (v/v) for 20 min and rinsed 4–5 times with sterile water. The sterilised seeds were trimmed at both ends and inoculated onto Murashige and Skoog (MS) (Coolaber, Beijing, China) [70] medium containing 10 mg/L Gibberellin acid (GA3) (Macklin, Shanghai, China), with a pH of 5.8 ± 0.2. The cultures were maintained at a temperature of 24 ± 2 °C under a 16 h/8 h light-dark cycle. After 15 days, the sterile seedlings of E. ulmoides reached a height of 5–8 cm, with hypocotyls measuring 3–5 cm.

4.2. Callus Induction and Embryogenic Callus Identification

The hypocotyls were sliced into 5–8 mm and inoculated onto B5 medium (Solarbio, Beijing, China) with varying concentrations of 6-Benzyl Aminopurine (6-BA) and α-Naphthaleneacetic acid (NAA) (both from Solarbio, China). A two-factor, five-level, full factorial experimental design was employed, 6-BA and NAA concentrations set at 0.2 mg/L, 0.5 mg/L, 1.0 mg/L, 1.5 mg/L, and 2.0 mg/L, respectively, resulting in 25 distinct treatment combinations (Table 1). Each treatment included 30 explants and was replicated three times. The culture conditions for explants were the same as those for sterile seedlings. After 30 days, the induction rate of callus was calculated by (Number of explants with callus/Total number of explants) × 100%. The state of callus was observed using a light microscope (OLYMPUS BX61, Tokyo, Japan) on the same day. The contribution rate of different callus types was calculated by (Number of callus with specific type/Total number of callus) × 100%. The proportion of different callus types was calculated under different ratios of 6-BA to NAA by (Number of callus with specific type and ratio/Total number of callus with specific ratio) × 100%.

The paraffin sectioning method, adapted from Li’s approach [71], was utilised to distinguish between embryogenic and non-embryogenic callus. In brief, the callus was fixed in a 5% Formalin-Aceto-Alcohol (FAA) (90 mL 50% alcohol, 5 mL acetic acid, 5 mL formaldehyde) solution for 24 h, dehydrated through a gradient ethanol series, embedded in paraffin, and then sliced into 8 μm-thick sections, stained with safranin-fast green, sealed with neutral gum, and observed under a light microscope (OLYMPUS BX61, Tokyo, Japan). The cytological characteristics of embryogenic callus were observed with reference to the description by Qin [72].

4.3. Protoplast Isolation and Purification

The isolation and purification of protoplasts were optimised according to the protocols of Yang [40] and He [46]. Briefly, 1.5 g of embryogenic callus was sliced into 1–2 mm particles and swiftly transferred into 15 mL of an enzyme solution (pH = 5.7) containing 0.1% Bovine serum albumin (BSA) (Solarbio, China), 10 mM CaCl2, 0.1% 2-(N-morpholino)ethanesulfonic acid monohydrate (MES) (Macklin, China), 0.6 M D-mannitol (Coolaber, China) and varying concentrations of cellulase R-10 and macerozyme R-10 (both from YAKULT, Tokyo, Japan). The mixture was then subjected to enzymatic treatment at 25 °C and 70 rpm in darkness for 4–10 h to dissolve the cell wall and release the protoplasts. To determine the optimal conditions for protoplast isolation, A three-factor and four-level orthogonal design was employed, and each treatment was performed in triplicate to ensure reproducibility. This design examined the concentrations of cellulase R-10 (0.5, 1.0, 1.5, 2.0%) and macerozyme R-10 (0.6, 0.8, 1.0, 1.2%), alongside the enzymatic hydrolysis duration (4, 6, 8, 10 h), resulting in sixteen distinct treatments. Following the identification of the optimal enzyme concentrations and digestion time, various D-mannitol concentrations (0.2, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 0.6, 0.7, 0.8 M) were tested to ensure the ideal osmotic pressure was maintained, and each treatment was performed in triplicate.

For purification, the hydrolysate was filtered twice through a 70 μm cell strainer to remove larger tissue. Subsequently, centrifugation was conducted at varying speeds (400, 600, 800, 1000, and 1200 rpm) for 5 min at room temperature to investigate the enrichment effect of centrifugal force on protoplasts. Each treatment was performed in triplicate. Then, the obtained protoplasts were resuspended in 5 mL of W5 solution (comprising 154 mM NaCl, 125 mM CaCl2, 5 mM KCl, 5 mM glucose, 2 mM MES) and washed three times. Finally, the protoplasts were resuspended in 1 mL of MMG solution (containing 15 mM MgCl2, 4 mM MES, 0.6 M D-mannitol, pH = 5.7) and incubated on ice for 30 min to assess the yield and viability of the protoplasts and perform transient transformation.

4.4. Protoplast Yield and Viability Assessment

The yield of protoplasts was assessed using a haemocytometer under a light microscope (Olympus BX61, Tokyo, Japan,). Protoplasts were stained with 0.1% (w/v) fluorescein diacetate (FDA) (Solarbio, China) in darkness for 5 min, after which their viability was examined using a fluorescence microscope (Carl Zeiss, Gottingen, Germany, Axio Imager M2), and FDA reacted with living cells to fluoresce green under excitation light of 488 nm. Protoplasts exhibiting green fluorescence were deemed viable. The calculations for protoplast yield and viability were as follows: Protoplast yield (protoplasts/g FW) = total number of protoplasts obtained/fresh weight of calls; Protoplast viability (%) = (number of the fluorescent protoplasts/total number of protoplasts) × 100%. Each treatment was conducted in triplicate.

4.5. Protoplast Transformation

Polyethylene glycol (PEG)-mediated protoplast transfection was carried out as described by Zhang [37] and Yang [40] with slight modifications. In brief, freshly isolated protoplasts were suspended in MMG solution to reach a final concentration of 1 × 105 protoplasts/mL. The purified pCAMBIA3301-35S-eGFP plasmid was introduced into a 2 mL round-bottom tube containing 110 μL of PEG buffer (containing 0.6 M D-mannitol and 0.1 M CaCl2) and 100 μL of the protoplast suspension, then gently mixed. After infection for various durations at 25 °C in the dark, we added 420 μL of W5 solution to terminate the transformation. Then, the mixture was centrifuged at 1000 rpm for 5 min, and the supernatant and protoplasts were washed twice with W5 solution.

To optimise transformation conditions, transient transformation experiments were conducted using varying concentrations of plasmid DNA (5 μg, 10 μg, 15 μg, 20 μg) with 40% PEG4000 and an incubation period of 20 min. Additionally, different PEG4000 concentrations (20%, 30%, 40%, 50%) were tested, maintaining a 20 min incubation and using 10 μg of plasmid. For the combination of 40% PEG4000 and 10 μg plasmid DNA, incubation times were varied at 5, 10, 15, 20, 25, and 30 min. The transformed protoplasts were cultured in darkness at 25 °C for 12 h before being examined under a fluorescence microscope. Green fluorescent protein (GFP) expression in the transfected protoplasts was observed using a fluorescence microscope with an excitation wavelength of 488 nm. Transformation efficiency was calculated using the formula: Transformation efficiency (%) = (number of fluorescent protoplasts/total number of protoplasts) × 100%. Each combination of conditions was performed in three independent experiments, observing five fields per replicate.

4.6. Detection of Transfected Protoplasts by PCR

Total genomic DNA from transfected and untransfected (control) protoplasts was extracted using the DNAsecure Plant Kit (TIANGEN, Beijing, China). M13 universal primers and enhanced GFP (eGFP) and neomycin phosphotransferase (NPTII) specific primers were used to detect the presence of pCAMBIA3301-35S-eGFP in the transfected protoplasts but not in the untransfected ones (Table 2). The PCR procedure was pre-denatured at 94 °C for 3 min; 35 cycles of denaturation at 94 °C for 30 s, annealing at 58 °C for 30 s, extended at 72 °C for 1 min; and extended at 72 °C for 5 min. Subsequently, PCR products were analysed by 1% (w/v) agarose gel electrophoresis.

Table 2.

Primer information for detecting the pCAMBIA3301-35S-eGFP plasmid [64].

4.7. Data Analysis

All quantitative data are presented as the mean ± standard deviation from at least three independent replicates. The statistical analysis was conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics Version 21.0 (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA). Data from the two-factor full factorial experiment (callus induction) were analysed by two-way ANOVA to assess main and interaction effects, followed by simple effects analysis and Fisher’s Least Significant Difference (LSD) test where appropriate. For the orthogonal experiments (protoplast isolation), significant factors were identified by ANOVA, and optimal conditions were determined via range analysis (R). All single-factor optimisation experiments (including those for mannitol concentration, centrifugation speed, and transient transformation conditions) were analysed by one-way ANOVA with LSD post hoc tests. Prior to all ANOVAs, assumptions of normality (Shapiro–Wilk test) and homogeneity of variances (Levene’s test) were verified. Statistical significance was defined as p < 0.05.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we established an efficient and reproducible system for embryogenic callus induction, protoplast isolation, and PEG-mediated transient transformation in E. ulmoides. Hypocotyls from 15-day-old sterile seedlings of E. ulmoides served as explants and were cultured on B5 solid medium supplemented with 1.5 mg/L 6-BA, 0.5 mg/L NAA and 30 g/L sucrose for 30 d, resulting in a contribution rate of 86.3% for embryogenic callus. The embryogenic callus was digested in an enzyme solution containing 1.5% cellulase R-10 and 1.0% macrozyme R-10 under 0.6 M D-Mannitol osmotic pressure for 4 h, followed by collection through centrifugation at 1000 rpm. High-quality protoplasts were obtained, yielding 1.82 × 106 protoplasts/g FW. When incubated with 10 μg of plasmid and 40% PEG4000 for 20 min, the transient transformation efficiency reached 53.23%. Furthermore, the developed method presents a convenient technology for applications such as protein subcellular localisation, protein-DNA interaction, protein–protein interaction, genome editing, and various other molecular biology research endeavours in E. ulmoides.

Author Contributions

H.Z. (Hongrun Zhou) was responsible for designing and conducting the experiments, analysing the data, and drafting the manuscript. Z.Z. contributed to the experiments and reviewed the manuscript. J.Z. (Jiangyuan Zhang) focused on data analysis. H.K. also participated in performing the experiments. Both M.Y. and H.Z. (Han Zhang) were involved in data analysis, while L.W. handled data analysis and image processing. J.Y. managed the project, secured funding, designed the experiments, and reviewed the manuscript. J.Z. (Jie Zhao) was involved in securing funding and reviewing the manuscript. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received financial support from the National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant No. 32360397 and Grant No. 32001913) and the Shihezi University Young Innovative Talents Program (No. CXBJ202101).

Data Availability Statement

All data are included in the present study.

Acknowledgments

The authors extend their heartfelt gratitude to Xiaojian Zeng for her meticulous guidance and patient assistance in experimental design and key technical operations. Appreciation is also due to Ke Meng for his collaborative support throughout the experiment. Special thanks are due to Xiaolei Cao for providing the pCAMBIA3301-35S-eGFP plasmid. The authors are also grateful to Zhaoqun Yao for his valuable suggestions for this research. During the preparation of this manuscript, Sci Draw https://scidraw.io/ and Bio GDP https://biogdp.com/ were utilised for creating scientific research vector graphics.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Dong, C.; Zhang, Z.; Shao, Q.; Yao, T.; Hu, H.; Huang, J.; Liang, Z.; Han, Y. Deciphering the effects of genetic characteristics and environmental factors on pharmacological active ingredients of Eucommia ulmoides. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 175, 114293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, Q.; Song, K.; Wang, L.; Du, L.; Du, H.; Li, B.; Li, H.; Yang, L.; Wang, Y.; Liu, P. Integrated transcriptomics and metabolomics analysis promotes the understanding of adventitious root formation in Eucommia ulmoides Oliver. Plants 2024, 13, 136. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Gong, H.; Feng, M.; Tian, C. Phenotypic variation in leaf, fruit and seed traits in natural populations of Eucommia ulmoides, a relict Chinese endemic tree. Forests 2023, 14, 462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Zeng, Q.; Li, Y.; Ding, Y.; Xue, D.; Guo, X. Improving antioxidative and antiproliferative properties through the release of bioactive compounds from Eucommia ulmoides Oliver bark by steam explosion. Front. Nutr. 2022, 9, 916609. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pan, Y.; Ming, K.; Guo, D.; Liu, X.; Deng, C.; Chi, Q.; Liu, X.; Wang, C.; Xu, K. Non-targeted metabolomics and explainable artificial intelligence: Effects of processing and color on coniferyl aldehyde levels in Eucommiae cortex. Food Chem. 2024, 460, 140564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Guo, J. Research progress on breeding of Eucommia ulmoides and application prospect. J. Zhejiang For. Sci. Technol. 2024, 44, 111–118. [Google Scholar]

- Han, Z.; Wang, Q.; Li, Y.; Liao, X.; Sun, R.; Xie, M. Extracting Eucommia ulmoides gum from Eucommia ulmoides Oliver and exploiting the residue as sustainable filler. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 222, 119585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duan, C.; Han, X.; Chang, Y.; Xu, J.; Yue, G.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, Y. A novel ternary deep eutectic solvent pretreatment for the efficient separation and conversion of high-quality gutta-percha, value-added lignin and monosaccharide from Eucommia ulmoides seed shells. Bioresour. Technol. 2023, 370, 128570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bao, L.; Sun, Y.; Wang, J.; Li, W.; Liu, J.; Li, T.; Liu, Z. A review of “plant gold” Eucommia ulmoides Oliv.: A medicinal and food homologous plant with economic value and prospect. Heliyon 2024, 10, e24851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Hu, F.; Yao, Z.; Zhao, X.; Chu, G.; Ye, J. Comprehensive genomic characterisation of the NAC transcription factor family and its response to drought stress in Eucommia ulmoides. PeerJ 2023, 11, e16298. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zuo, Y.; Li, B.; Guan, S.; Jia, J.; Xu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Lu, Z.; Li, X.; Pang, X. EuRBG10 involved in indole alkaloids biosynthesis in Eucommia ulmoides induced by drought and salt stresses. J. Plant Physiol. 2022, 278, 153813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Du, J.; Zhang, H.; Li, W.; Li, X.; Wang, Z.; Zhang, Y.; Xiong, A.; Li, M. Optimization of protoplast preparation system from leaves and establishment of a transient transformation system in Apium graveolens. Agronomy 2023, 13, 2154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaganathan, D.; Ramasamy, K.; Sellamuthu, G.; Jayabalan, S.; Venkataraman, G. CRISPR for crop improvement: An update review. Front. Plant Sci. 2018, 9, 985. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poddar, S.; Tanaka, J.; Cate, J.H.D.; Staskawicz, B.; Cho, M.J. Efficient isolation of protoplasts from rice calli with pause points and its application in transient gene expression and genome editing assays. Plant Methods 2020, 16, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, H.H.; Naing, A.H.; Kim, C.K. Protoplast isolation and shoot regeneration from protoplast-derived callus of Petunia hybrida Cv. Mirage Rose. Biology 2020, 9, 228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, N.; Liu, J.; Zhang, X.; Dong, J.E. Preparation and vitality detection of protoplast in Salvia miltiorrhiza Bunge. Chin. J. Biotechnol. 2014, 30, 1612–1621. [Google Scholar]

- Blanc, G.; Lardet, L.; Martin, A.; Jacob, J.L.; Carron, M.P. Differential carbohydrate metabolism conducts morphogenesis in embryogenic callus of Hevea brasiliensis (Müll. Arg.). J. Exp. Bot. 2002, 53, 1453–1462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baskaran, P.; Kumari, A.; Naidoo, D.; Van Staden, J. In vitro propagation and ultrastructural studies of somatic embryogenesis of Ledebouria ovatifolia. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol.-Plant 2016, 52, 283–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Neves, N.; Segura-Nieto, M.; Blanco, M.A.; Sánchez, M.; González, A.; González, J.L.; Castillo, R. Biochemical characterization of embryogenic and non-embryogenic calluses of sugarcane. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol.-Plant 2003, 39, 343–345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudiam, M.K.R.; Ng, T.L.M.; Karim, R.; Tan, Y.S.; Teh, H.F.; Danial, A.D.; Ho, L.S.; Khalid, N.; Appleton, D.R.; Harikrishna, J.A. Amino acid and secondary metabolite production in embryogenic and non-embryogenic callus of fingerroot ginger (Boesenbergia rotunda). PLoS ONE 2016, 11, e0156714. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, J.; Wang, N. Development of multiplex genome editing toolkits for citrus with high efficacy in biallelic and homozygous mutations. Plant Mol. Biol. 2020, 104, 297–307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Omar, A.A.; Murata, M.M.; El-Shamy, H.A.; Graham, J.H.; Grosser, J.W. Enhanced resistance to citrus canker in transgenic mandarin expressing Xa21 from rice. Transgenic Res. 2018, 27, 179–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, Y.; Tang, T.; Cao, W.; Ali, M.; Zhou, Q.; Zhu, D.; Ma, X.; Cai, Y.; Zhang, Q.; Wang, Z.; et al. Protoplast transient transformation facilitates subcellular localization and functional analysis of walnut proteins. Plant Physiol. 2025, 197, kiae627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Zhang, M.; Han, M.; Rong, J.; Peng, W.; Wang, Y.; Zhao, Y.; Lei, X.; Zhang, J.; Wang, Y. Development of a transient expression system for Panax ginseng based on protoplast isolation from its embryoids. Hortic. Plant J. 2025, 11, 459–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gou, Y.; Li, Y.; Bi, P.; Wang, D.; Ma, Y.; Hu, Y.; Zhou, H.; Wen, Y.; Feng, J. Optimization of the protoplast transient expression system for gene functional studies in strawberry (Fragaria vesca). Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2020, 141, 41–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Chen, J.; Pi, X.; Huang, L.; Li, N. Isolation, purification, and application of protoplasts and transient expression systems in plants. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 16892. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Ren, J.; Liu, W.; Liu, D.; Xie, K.; Zhang, F.; Wang, P.; Guo, W.; Wu, X. An efficient transient gene expression system for protein subcellular localization assay and genome editing in citrus protoplasts. Hortic. Plant J. 2023, 9, 425–436. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, P.; Sun, Y.; Sun, X.; Li, Y.; Wang, L. Optimization of preparation and transformation of protoplasts from Populus simonii × P. nigra leaves and subcellular localization of the major latex protein 328 (MLP328). Plant Methods 2024, 20, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jin, J.; Gui, S.; Li, Q.; Wang, Y.; Zhang, H.; Zhu, Z.; Chen, H.; Sun, Y.; Zou, Y.; Huang, X.; et al. The transcription factor GATA10 regulates fertility conversion of a two-line hybrid tms5 mutant rice via the modulation of UbL40 expression. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2019, 62, 1034–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jung, H.; Yan, J.; Zhai, Z.; Vatamaniuk, O.K. Gene functional analysis using protoplast transient assays. In Plant Functional Genomics: Methods and Protocols; Springer: New York, NY, USA, 2015; Volume 1284, pp. 433–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzak, M.A.; Lee, J.; Lee, D.W.; Kim, J.H.; Yoon, H.S.; Hwang, I. Expression of seven carbonic anhydrases in red alga Gracilariopsis chorda and their subcellular localization in a heterologous system, Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Rep. 2018, 38, 147–159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Xiao, K.; Li, S.; Li, J.; Huang, J.; Chen, R.; Pang, S.; Zhou, X. Genome-wide analysis of the NAAT, DMAS, TOM, and ENA gene families in maize suggests their roles in mediating iron homeostasis. BMC Plant Biol. 2022, 22, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, S.; Qu, G.; Li, X.; Zhang, F. Highly efficient endosperm and pericarp protoplast preparation system for transient transformation of endosperm-related genes in wheat. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2023, 155, 165–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, D.; Liu, G.; Liu, R.; Wang, C.; Xu, F.; Xu, Q.; Ling, Y.; Dong, G.; Peng, Y.; Ge, S.; et al. Positional cloning identified HvTUBULIN8 as the candidate gene for round lateral spikelet (RLS) in barley (Hordeum vulgare L.). Theor. Appl. Genet. 2023, 136, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanzawa, Y.; Wu, F. A simple method for isolation of soybean protoplasts and application to transient gene expression analyses. J. Vis. Exp. JoVE 2018, 25, 57258. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, K.; Shin, J.; Lee, J.D.; Kim, W.C. Establishment of efficient hypocotyl-derived protoplast isolation and its application in soybean (Glycine max [L.] Merr.). Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1587927. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, X.; Peng, R.; Tian, X.; Guo, Y.; Li, X.; Liu, X.; Xie, Y.; Li, M.; Xia, H.; Liang, D. Establishment of protoplasts isolation and transient transformation system for kiwifruit. Sci. Hortic. 2024, 329, 113034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, K.; Chen, Z.; Radani, Y.; Zheng, R.; Zheng, X.; Li, Y.; Chen, J.; Yang, L. Establishment of PEG-mediated transient gene expression in protoplasts isolated from the callus of Cunninghamia lanceolata. Forests 2023, 14, 1168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Lee, J.H.; Poindexter, M.R.; Shao, Y.; Liu, W.; Lenaghan, S.C.; Ahkami, A.H.; Blumwald, E.; Stewart, C.N. Rational design and testing of abiotic stress-inducible synthetic promoters from poplar cis-regulatory elements. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 1354–1369. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yang, C.; Yu, R.; Li, J.; Wang, K.; Liu, G. Preparation of leaf protoplasts from Populus (Populus × xiaohei T. S. Hwang et Liang) and establishment of transient expression system. J. Plant Physiol. 2023, 291, 154122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tricoli, D.M.; Debernardi, J.M. An efficient protoplast-based genome editing protocol for Vitis species. Hortic. Res. 2024, 11, uhad266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Li, Y.; Hu, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zang, X.; Ding, Q.; Wang, Y.; Wen, Y. A highly efficient grapevine mesophyll protoplast system for transient gene expression and the study of disease resistance proteins. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2015, 125, 43–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Fu, J.; Guo, W. Mitochondrial genome of callus protoplast has a role in mesophyll protoplast regeneration in Citrus: Evidence from transgenic GFP somatic homo-fusion. Hortic. Plant J. 2017, 3, 177–182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, Z.; Huang, L.; Yu, P.; Chen, J.; Du, S.; Qin, G.; Zhang, L.; Li, N.; Yuan, D. Development of a protoplast isolation system for functional gene expression and characterization using petals of Camellia Oleifera. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2023, 201, 107885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, S.; Zhao, R.; Ye, T.; Guan, R.; Xu, L.; Ma, X.; Zhang, J.; Xiao, S.; Yuan, D. Isolation, purification and PEG-mediated transient expression of mesophyll protoplasts in Camellia oleifera. Plant Methods 2022, 18, 141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, X.; Xu, L.; Xu, X.; Yi, D.; Hou, S.; Yuan, D.; Xiao, S. Embryogenic callus induction, proliferation, protoplast isolation, and PEG induced fusion in Camellia oleifera. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2024, 157, 75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Wei, H.; Yang, J.; Du, K.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Qiu, T.; Liu, Z.; Ren, Y.; Song, L.; et al. High-quality de novo assembly of the Eucommia ulmoides haploid genome provides new insights into evolution and rubber biosynthesis. Hortic. Res. 2020, 7, 183. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Li, B.; Li, X.; Yuan, X.; Qu, B.; Wang, X.; Gao, X.; Fu, Y.; Gu, C. Deciphering the effects of Endophytic Aspergillus sp. Y232 on plant growth and the accumulation of characteristic bioactive compounds of Eucommia ulmoides Oliver. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2025, 73, 15014–15026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Cheng, T.; Wang, L.; Lian, C.; Ma, R.; Feng, W.; Lan, J.; Zhang, B.; Du, Q.; Kou, J.; et al. Genome-wide identification and comprehensive analysis of EuFLS genes in Eucommia ulmoides reveals their roles in growth, development, and abiotic stress response. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1662635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, R.; Namimatsu, S.; Nakadozono, Y.; Bamba, T.; Nakazawa, Y.; Gyokusen, K. Efficient regeneration of Eucommia ulmoides from hypocotyl explant. Biol. Plant. 2008, 52, 713–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiao, S.; Tian, X.; Zhang, Y.; Wu, J.; Qin, C.; Wei, H.; Xie, S.; Yang, J.; Li, D.; Liu, Y. Development of Eucommia ulmoides Oliver tissue culture for in vitro production of the main medicinal active components. Vitr. Cell. Dev. Biol.-Plant 2024, 60, 548–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Long, S.; Yang, J.; Wang, H.; Chen, X.; Zhao, D.; Zhao, Y. Genome-wide identification of EuUSPs in Eucommia ulmoides and the role of EuUSP16 in rubber biosynthesis. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1655155. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, L.; Zhao, D. Cloning and functional characterization of the legumin a gene (EuLEGA) from Eucommia ulmoides Oliver. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 14111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Wang, L.; Chen, C.; He, C.; Hu, J.; Zhu, Y.; Huang, W. Protoplast: A more efficient system to study nucleo-cytoplasmic interactions. Biochem. Biophys. Res. Commun. 2014, 450, 1575–1580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Dong, X.; Tan, A.; Zhao, D.; Zhao, Y. Optimization of regeneration system of transgenic Eucommia ulmoides Olive. Seed 2019, 38, 18–22, 27. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, S.; Wang, M.; Zhang, S. Rapid propagation technology of Eucommia ulmoides aseptic seedling tissue culture. Mol. Plant Breed. 2019, 22, 3045–3052. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, H.; Hu, Y.; Zhang, G.; Chen, S.; Wu, D.; Zhang, D.; Huang, G.; Zhang, B. Study on callus induction and proliferation culture technology of Eucommia ulmoides Oliv. J. Agric. Sci. Technol. 2019, 21, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Ren, Y.; Wang, S.; Song, L.; Jing, Y.; Xu, T.; Kang, X.; Li, Y. EuHDZ25 positively affects rubber biosynthesis by targeting EuFPS1 in Eucommia leaves. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 272, 132707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Chen, H.; Wang, S.; Du, K.; Song, L.; Xu, T.; Xia, Y.; Guo, R.; Kang, X.; Li, Y. Positive regulation of the Eucommia rubber biosynthesis-related gene EuFPS1 by EuWRKY30 in Eucommia ulmoides. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2024, 268, 131751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cosgrove, D.J. Structure and growth of plant cell walls. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2024, 25, 340–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- David, H.; Laigneau, C.; David, A. Growth and soluble proteins of cell cultures derived from explants and protoplasts of Pinus pinaster cotyledons. Tree Physiol. 1989, 5, 497–506. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, B.; Dong, M.; Liu, R.; Shan, W.; Wang, Y.; Ding, Y.; Peng, J.; Meng, L.; Wang, C.; Zhou, Q. Establishment of an efficient protoplast isolation and transfection method for Eucommia ulmoides Oliver. Front. Biosci. Landmark 2024, 29, 187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Russell, J.A. Advances in the protoplast culture of woody plants. In Micropropagation of Woody Plant; Springer: Dordrecht, The Netherlands, 1993; pp. 67–91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, X.; Cao, X.; Zhao, Q.; Hou, S.; Hu, X.; Yang, Z.; Hao, T.; Zhao, S.; Yao, Z. Isolation of haustorium protoplasts optimized by orthogonal design for transient gene expression in Phelipanche aegyptiaca. Plants 2024, 13, 2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yao, L.; Liao, X.; Gan, Z.; Peng, X.; Wang, P.; Li, S.; Li, T. Protoplast isolation and development of a transient expression system for sweet cherry (Prunus avium L.). Sci. Hortic. 2016, 209, 14–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, T.T.T.; Choi, N.Y.; Pyo, S.W.; Choi, Y.I.; Ko, J.H. Optimized and reliable protoplast isolation for transient gene expression studies in the gymnosperm tree species Pinus densiflora. Forests 2025, 16, 1373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Z.; Tong, H.; Liang, L.; Shi, Y.; Yuan, L. Protoplast isolation and fusion induced by PEG with leaves and roots of tea plant (Camellia sinensis L.O. Kuntze). Acta Agron. Sin. 2018, 44, 463–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Yu, G.; Chen, Z.; Han, J.; Hu, Y.; Wang, K. Optimization of protoplast isolation, transformation and its application in sugarcane (Saccharum spontaneum L). Crop J. 2021, 9, 133–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, S.; Li, Z.; Yi, D.; Wu, J.; Hu, Y.; Fan, X.; Yuan, D. Establishment of a system for tissue culture regeneration and isolation of Camellia yubsienensis, and PEG-mediated transient expression of mesophyll protoplasts. Ind. Crops Prod. 2024, 222, 119897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murashige, T.; Skoog, F. A revised medium for rapid growth and bio assays with tobacco tissue cultures. Physiol. Plant. 1962, 15, 473–497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, T.; Lin, J.; Lian, X.; Zou, X.; Ma, X.; Wu, P. Longitudinal section cell morphology of Chinese fir roots and the relationship between root structure and function. Front. Ecol. Evol. 2023, 11, 1122860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, Y.; Zhang, B.; Wang, S.; Guo, W.; Zhang, Z.; Qin, Y.; Zhao, J.; Hu, G. Establishment of somatic embryogenesis regeneration system and transcriptome analysis of early somatic embryogenesis in litchi. Hortic. Plant J. 2025, 11, 535–547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.