Abstract

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is one of the major health threats of the 21st century and demands innovative sources of bioactive compounds. In 2019, infections caused by resistant bacteria directly accounted for 1.27 million deaths and contributed to an additional 4.95 million associated deaths, underscoring the urgency of exploring new strategies. Among emerging alternatives, specialized plant metabolites stand out, as their biosynthesis is enhanced under biotic or abiotic stress. These stimuli increase reactive oxygen species (ROS), activate cascades regulated by mitogen-activated protein kinases (MAPKs), and trigger defense-related hormonal pathways involving salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA), ethylene (ET), and abscisic acid (ABA), which in turn regulate transcription factors and biosynthetic modules, promoting the accumulation of compounds with antimicrobial activity. In this review, we synthesize recent literature (2020–2025) with emphasis on studies that report quantitative activity metrics. We integrate evidence linking stress physiology and metabolite production, summarize mechanisms of action, and propose a conceptual multi-omics pipeline, synthesized from current best practices, that combines RNA sequencing and LC/GC-MS-based metabolomics with bioinformatic tools to prioritize candidates with antimicrobial potential. We discuss elicitation strategies and green extraction, highlight bryophytes (e.g., Pseudocrossidium replicatum) as a differentiated chemical source, and explore citrus Huanglongbing (HLB) as a translational case study. We conclude that integrating stress physiology, multi-omics, and functional validation can accelerate the transition of stress-induced metabolites toward more sustainable and scalable medical and agricultural applications.

1. Introduction

Antimicrobial resistance (AMR) is a growing health threat that compromises advances in human medicine and animal health. Infections caused by bacteria, parasites and fungi have become progressively more difficult to treat because of excessive and, in many cases, inappropriate use of antimicrobials. In 2019 an estimated 1.27 million deaths were directly attributable to infections caused by resistant bacteria and 4.95 million deaths were associated with AMR [1]. If the global response is not strengthened, economic impacts by 2035 are projected to reach approximately US $412 billion per year in health-care costs and US $443 billion per year in lost productivity [2], highlighting the urgency of exploring complementary and safer strategies to conventional antibiotics.

One alternative within green biotechnology is the use of plants, sessile organisms that are continuously exposed to a wide range of biotic and abiotic stresses. In response, they have evolved complex defense mechanisms that include the synthesis of thousands of bioactive molecules derived from specialized metabolism; many of these have been reported to possess antimicrobial potential. This chemical diversity can be exploited through elicitation strategies that stimulate specific biosynthetic pathways and raise the levels of metabolites of interest, which can then be isolated as extracts or essential oils, among other formats [3].

Among the best-studied compounds are the phenolic monoterpenoids carvacrol, thymol and eugenol, as well as the phenylpropanoid cinnamaldehyde. These molecules have shown broad-spectrum antibacterial activity and, in addition, antifungal, antiviral, anti-inflammatory and even anticancer properties, mainly in preclinical models [4]. These phytochemicals act through diverse mechanisms that include membrane destabilization, enzyme inhibition, interference with biofilm formation and modulation of quorum sensing, among others [5]. Synergistic effects with conventional antibiotics have also been documented, lowering minimum inhibitory concentrations and improving therapeutic efficacy [6]. However, their safety profiles depend on dose, composition and formulation; in some cases adverse effects, including phototoxicity, have been reported, which require rigorous evaluation before any clinical or agricultural application [7,8].

This review compiles recent literature (2020–2025) that links plant stress with defense signaling, biosynthetic reprogramming and antimicrobial activity, prioritizing studies with comparable quantitative metrics (e.g., fold-change, minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), fractional inhibitory concentration index (FICI) and inhibition zone diameters). We also highlight frequent inconsistencies in the literature, such as heterogeneous units (% v/v vs. µg/mL) and insufficient controls, which hinder comparison across studies. Building on this foundation, we propose a multi-omics pipeline that connects induction design (biotic/abiotic stress and elicitation), transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses, in silico prioritization of candidates and bioactivity validation. Where relevant, we emphasize evidence from underexplored lineages such as bryophytes (for example, Pseudocrossidium replicatum) and discuss potential agricultural applications, including the case of Huanglongbing and Candidatus Liberibacter. The ultimate goal is to support more rigorous scrutiny in the identification of plant metabolites with antimicrobial potential and to facilitate their transition toward medical and agricultural applications, without losing sight of safety, stability and scalability requirements (see Figure 1).

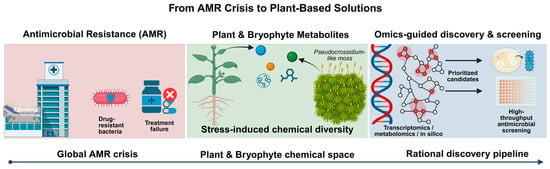

Figure 1.

Conceptual framework linking the antimicrobial resistance (AMR) crisis to plant-based solutions. The scheme illustrates the progression from drug-resistant bacterial infections and treatment failure (left) to stress-induced chemical diversity in plants and bryophytes, exemplified by moss systems such as Pseudocrossidium. Integration of transcriptomics, metabolomics, and in silico analyses enables the prioritization of candidate compounds, which are subsequently evaluated through high-throughput antimicrobial screening (right).

2. Stress-Induced Metabolic Reprogramming

2.1. Abiotic Stress: Quantifiable Elicitation

Abiotic stressors can positively regulate the biosynthesis of specialized metabolites and increase the abundance of molecules with antimicrobial activity. In practice, the most extensively studied abiotic stimuli include controlled water deficit, UV radiation and temperature regimes (cold or heat shock), among others [9].

Preharvest water deficit in phenolic-rich species such as olive (Olea europaea) has been shown to increase total polyphenol content [10]. This finding is consistent with the strong antifungal activity of these extracts against Candida spp., validated in broth microdilution assays [11]. Similarly, moderate postharvest exposure to UV-C in table grape (Vitis vinifera) induces high resveratrol accumulation in the berry skin and is associated with reduced incidence of gray mold caused by Botrytis cinerea; under certain regimes, the UV-C response surpasses that of UV-B, although the final effect depends on the cultivar and postharvest handling [12]. Related postharvest resistance responses have also been documented in citrus under UV-C or heat treatments [13,14].

Another example is the controlled application of temperature in Mentha species and its impact on the profile of foliar monoterpenes. Thermal pulses reconfigure leaf monoterpenes, and the effect on bioactivity varies according to species and conditions: in M. arvensis, warmer and drier conditions have increased inhibition zones against Staphylococcus and Bacillus, whereas in M. × piperita maximum effects have been observed under more temperate temperature regimes [15]. Taken together, these stimuli generate specific response chemotypes in which the basal levels of certain compounds are increased or intrinsic synergies within the extract emerge.

These stressors converge on relatively conserved signaling nodes: ROS, Ca2+ fluxes and MAPK cascades, which activate transcription factors (e.g., WRKY, MYB, bHLH) and thereby phenylpropanoid (PAL, C4H, 4CL), terpenoid (TPS) and polyketide (PKS) pathways [9,16,17]. The outcome is a reprogrammed chemical profile in which compounds that are absent or scarce under basal conditions emerge.

2.2. Biotic Stress and Elicitors: From PAMPs to Quantifiable Phytoalexins

Recognition of pathogen-associated molecular patterns (PAMPs) by pattern-recognition receptors (PRRs) triggers pattern-triggered immunity (PTI) [18]. This perception activates signaling cascades (Ca2+, ROS, MAPKs) that reprogram metabolism and can synergize with effector-triggered immunity (ETI) [19].

A widely studied model in Arabidopsis thaliana illustrates this axis: perception of bacterial PAMPs induces massive accumulation of the antifungal phytoalexin camalexin, with increases of approximately 20–60-fold over basal levels and effective control of necrotrophic pathogens in infection assays [20].

This principle translates directly to crops of agricultural interest. In soybean (Glycine max), elicitation or activation of key transcription factors, such as the MYB-like factor GmMYB29A2, induces the accumulation of glyceollins (I–III) and reduces disease severity caused by the oomycete Phytophthora sojae [21]; the magnitude of this induction has been reported to exceed 10-fold following elicitor treatment [22]. In citrus, postharvest UV-C irradiation and heat treatment induce accumulation of the phytoalexin scoparone, effectively preventing rot caused by Penicillium spp. [13,14]. Likewise, application of the elicitor chitosan in grapevine (V. vinifera) induces stilbenes such as trans-resveratrol and results in quantifiable protection against Botrytis cinerea, with 41–69% reductions in lesion diameter on leaves [23].

Taken together, these examples support the notion that exposure of plants to biotic or abiotic external signals, as well as to exogenous elicitors, provokes chemical changes that are detectable and measurable using comparable quantitative metrics (e.g., metabolite fold-change, minimum inhibitory concentration (MIC), IC50, EC50 and percentage reduction in disease severity), which translate into effective responses against pathogens.

2.3. Hormonal Regulation, Transcription Factors and Crosstalk: The Conductors of the Defensive Orchestra

Early signals are amplified by second messengers such as Ca2+, ROS and MAPKs, which function as an “alarm” and report exposure to stress; downstream, regulation is mediated by phytohormones that orchestrate the specific pathway leading to the metabolic response. The SA/NPR1 pathway is mainly associated with biotrophs and immune memory. SA activates the receptor NON-EXPRESSOR OF PR-1 (NPR1), which undergoes redox-dependent changes and migrates to the nucleus to cooperate with transcription factors (TFs) of the TGA and WRKY families, establishing an effective defense against biotrophic pathogens. This pathway is central to Systemic Acquired Resistance (SAR), a form of “memory” that primes distal tissues for future challenges [24,25].

In addition, necrotrophic pathogens and herbivores stimulate the JA/ET pathway, in which the bioactive signal jasmonoyl-isoleucine (JA-Ile) promotes COI1–JAZ interaction and JAZ degradation, releasing MYC2 and other bHLH factors to induce protective responses (e.g., terpenoids, alkaloids) [26]. In parallel, JA and ET converge on ERF-like factors; in Arabidopsis, ORA59 integrates this synergy and regulates genes such as PDF1.2, which plays a key role against necrotrophic pathogens [27]. Antagonism between the SA and JA/ET pathways has been reported, although the outcome depends on context (tissue, dose, time-of-day biology and pathogen). The underlying interaction network reveals multiple points of crosstalk (protein stability, transcriptional control, hormonal homeostasis) that can explain scenarios of antagonism, variable activity or synergy [28].

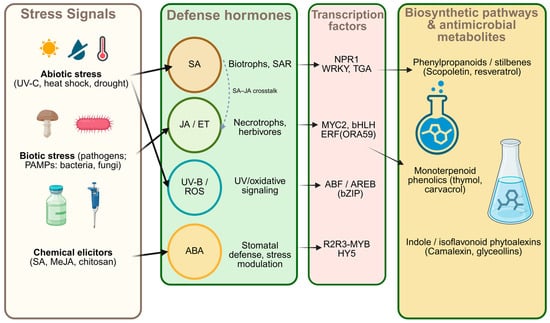

In the case of ABA, its role has traditionally been associated with drought, and it modulates stomatal defense: it can promote rapid closure that limits bacterial entry, while also reconfiguring responses according to water status and other signals, acting either as an attenuator or a potentiator [29]. The hormonal pathways mentioned above act as “conductors of the orchestra” that instruct specific groups of “managers” what to do. These managers are TFs—proteins that function as master switches to “turn on” or “turn off” metabolite factories (biosynthetic pathways). Each hormonal pathway has its own characteristic TFs: the SA pathway activates WRKY and TGA families; the JA pathway activates MYC2; JA/ET synergy activates ERFs; ABA signals through ABF/AREB; and UV stress pathways activate the MYB family (see Figure 2). Table 1 summarizes metabolites with antimicrobial activity and their predominant hormonal regulators.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of stress perception, hormone signaling, transcriptional regulation, and biosynthetic pathways involved in the production of antimicrobial plant metabolites. Hormones and transcription factors shown represent major defense modules activated under abiotic and biotic stress. Arrow notation: solid arrows indicate directional signaling/putative positive regulatory links; the dotted arrow indicates SA–JA/ET pathway crosstalk.

Table 1.

Hormones, transcription factors (TFs), nodes and metabolic pathways associated with plant defense responses.

It is crucial to note that the magnitude and type of metabolic response are not universal; the final chemical profile is highly dependent on key modulatory factors, including genotype, specific tissue, developmental stage (time) and environment [34,35]. This contrast is particularly evident between controlled laboratory conditions, and the multiple, unpredictable stressors present in the field [36]. Taken together, these variables, along with heterogeneity in extraction and assay methods, help explain the wide variability in reported antimicrobial potency (e.g., inconsistent MIC values) across the literature [37].

3. Classes of Metabolites and Mechanisms of Action

Having established how plants activate their chemical arsenal in response to stress, this section focuses on which specific “weapons” make up that arsenal.

The chemical biodiversity of plants offers an immense set of metabolomic responses tailored to different stimuli, yet most reported metabolites with antimicrobial activity cluster into a few major chemical “superfamilies”, such as terpenoids, phenylpropanoids (including flavonoids and stilbenes), alkaloids and saponins.

Each family tends to display characteristic mechanisms of action. For example, the phenolic monoterpenes carvacrol and thymol are known to destabilize bacterial membranes and alter ionic permeability, whereas alkaloids such as berberine can intercalate into DNA or inhibit efflux pumps (EPIs), thereby enhancing the activity of other antibiotics. Table 2 summarizes these main chemical families, their emblematic compounds, their best-known mechanisms of action, examples of microbial targets and the reported activity ranges (MIC/MBIC/ED50).

Table 2.

Chemical families, emblematic compounds, mechanisms of action, examples of microbial targets and reported activity ranges (MIC/MBIC/ED50).

4. Multi-Omics and Bioinformatics for Discovery and Prioritization

4.1. Pipeline: From RNA-Seq + LC/GC-MS to DEG–Metabolite Correlations

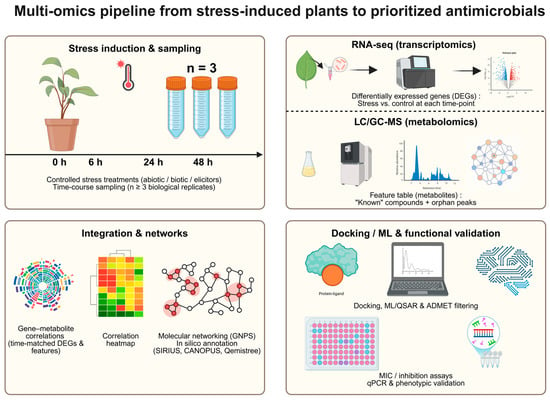

Here we outline a conceptual workflow, synthesized from current best practices, to guide the integration of transcriptomics (RNA-seq) and LC/GC-MS-based metabolomics for prioritizing candidates with antimicrobial potential for downstream validation. A robust current approach integrates multi-omics datasets to predict biosynthetic pathways de novo [57]. This pipeline focuses on genes associated with a given biosynthetic route and complements their analysis with transcriptomics (RNA-seq) and metabolomics (LC-MS or GC-MS) to identify bioactive compounds of interest [58]. To robustly link gene induction to the accumulation of metabolites with antimicrobial potential, an appropriate experimental design is essential. This implies serial sampling at selected time points (e.g., 0, 6, 24, 48 h) after application of the elicitor or stimulus of interest (biotic or abiotic stress), with a minimum of three biological replicates (n ≥ 3) per independent experiment [59]. Samples for transcriptomic and metabolomic analyses must be collected from the same tissue type, under the same conditions (photoperiod, developmental stage, etc.) and at the same time points to ensure that the datasets are directly comparable and suitable for correlation analyses (see Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Workflow illustrating the integration of transcriptomics, metabolomics, and in silico analyses to prioritize antimicrobial metabolites from stress-induced plant systems.

Each arm of the pipeline generates a different type of data. The transcriptomic arm (RNA-seq) yields list of differentially expressed genes (DEGs), identifying which genes are “turned on” or “off” together with their magnitude (log2FC) and statistical significance (FDR) at each time point [59]. In parallel, the metabolomic arm detects and annotates the peaks of metabolites that have accumulated or decreased, many of which may initially be unknown (“orphan peaks”) [60]. After preprocessing, this results in paired quantitative matrices of genes and metabolites across time and conditions.

The strength of the pipeline lies in the bioinformatic correlation of these two matrices [57,58]. The objective is to identify patterns of co-expression and co-accumulation: a gene that encodes a biosynthetic enzyme—such as a cytochrome P450 (CYP450) or a UDP-glycosyltransferase (UGT) that switches “on” (high fold-change) exactly when a specialized metabolite for example, a new terpene “accumulates” (high intensity). This temporal coincidence constitutes one of the strongest lines of evidence to propose that the gene encodes the enzyme responsible for the formation of the corresponding metabolite. Prioritized candidates can then advance to annotation (e.g., MSI Level 2) and experimental validation (qPCR, chemical standards, antimicrobial activity assays) [60].

4.2. Analytics and Networks: Annotation, Metabolomic Networking and Co-Expression

The pipeline described in Section 4.1 generates two matrices, transcript counts and chromatographic features and this is where the main challenge begins. We now have signal detection, but we still need to “assign surnames” through chemical annotation or identification, especially for the “orphan peaks” that lack matches in spectral libraries [61].

However, it is important to recognize that current MS/MS spectral libraries remain incomplete and unevenly populated, with biases toward well-studied organisms and compound classes, as well as method-dependent effects (instrument type, collision energy, ionization/adduct patterns) that can limit the transferability of spectral matches across studies. Consequently, many plant specialized metabolites particularly low-abundance features, conjugates, and closely related isomers remain unmatched, and even apparent library hits may require cautious interpretation. In this context, combining library searching with network context and state-of-the-art in silico annotation helps reduce over-interpretation while prioritizing candidates for targeted confirmation. Importantly, broader community sharing of MS/MS data and associated metadata through open platforms accelerates library growth and curation, improving reusability and progressively converting ‘orphan peaks’ into identifiable metabolites over time [61,62,63].

For this reason, the field has moved from classical feature processing (e.g., MZmine [64], MS-DIAL [50]) toward network-based analytics that organize the apparent chaos and add biological context.

The most transformative approach has been Molecular Networking, implemented in the GNPS environment [62]. This method connects spectra based on similarity, so that “chemical families” emerge, where a known compound “pulls the thread” of related unknowns. In other words, we move from seeing isolated stars to recognizing constellations, grouping known and unknown metabolites based on MS/MS fragmentation similarity. In parallel, tools such as Qemistree [65] project chemical space as a tree of molecular “fingerprints” that can be crossed with metadata (tissue, time) and expression data (co-expression), linking chemistry and biology on the same map.

To name unknown nodes in these networks, state-of-the-art in silico tools are employed. Platforms such as SIRIUS/CANOPUS [51] and COSMIC [63] use deep learning to predict the formula and structural class of a metabolite from its spectrum. In parallel, spectral similarity algorithms such as Spec2Vec [66] and MS2Query [67] dramatically improve the ability to find structural analogs that are not present in libraries.

These co-dynamics of co-expression and co-accumulation make it possible to identify candidate enzymes and propose pathways, generating solid hypotheses before targeted validation (chemical standards, qPCR, bioassays) [57,58,60]. In other words, it is akin to assigning a “provisional ID” to peaks: a tentative name, a structural class and the chemical and genetic “neighborhood” that supports it. These open-source tools allow researchers to navigate the metabolomic “dark matter” and prioritize which orphan peaks are biosynthetically relevant [68] (see Table 3).

Table 3.

Representative bioinformatics tools across the multi-omics workflow and their primary applications.

4.3. Functional Prediction (Docking/ML) and Prioritization Criteria

Once the annotation stage has provided candidates (the “provisional IDs”), the key question is no longer what is there? but what is most reliable and worth testing first? This is where functional prediction becomes central for prioritization. The aim is to filter, in silico, hundreds of “orphan” metabolites and select the few that truly justify costly validation in the laboratory. The main tool for this is molecular docking, which acts as a prioritization funnel by simulating whether the “key” (metabolite) fits into the “lock” (protein target) and by predicting its relative binding affinity [69].

In parallel, machine learning (ML) and QSAR models employ artificial intelligence to recognize patterns between chemical structure and biological activity [55], thus accelerating candidate identification. Crucially, they are also used to estimate ADMET profiles (Absorption, Distribution, Metabolism, Excretion, Toxicity), which are fundamental for prioritization and do not replace bioassays [70].

However, it is essential to adopt the critical perspective emphasized in this review: in silico results are not proof of activity, but tools for prioritization. For natural products, in silico methods are most powerful when they shrink the search space (combining docking, similarity and ADMET rules), yet they can easily overpromise if uncertainty is not reported (for example, variance among scores). Docking scores do not always correlate directly with MIC values obtained in the laboratory. There are significant challenges (protein flexibility, solvation, target selection) that can lead to false positives [56]. Therefore, to make these methods genuinely useful, they must follow rigorous protocols, which are summarized in Box 1.

Box 1. Best practices for in silico screening of natural products.

1. Receptor (target) preparation

- Use high-resolution crystallographic or cryo-EM structures (≤2.5 Å) whenever available.

- For AlphaFold models, evaluate quality using pLDDT, Ramachandran plots, and visual inspection before use.

- Adjust protonation states of catalytic residues and retain only functional cofactors.

- When possible, consider multiple receptor conformations (ensemble docking) to capture flexibility [71,72].

2. Ligand preparation (natural metabolites)

- Generate relevant tautomers and protonation states at physiological pH (7.0–7.4).

- Minimize energy and sample realistic conformations, especially for highly flexible molecules (e.g., terpenes).

- Define stereochemistry and 3D geometry correctly before docking and check for artifacts in very lipophilic compounds [73,74].

3. Binding site definition

- Prioritize docking directed to a validated active site (crystallographic data, mutagenesis, or other functional evidence).

- Define the grid box with a margin of ~5 Å around key residues.

- Avoid relying exclusively on blind docking due to its low specificity, and consider structural waters when they participate in catalysis [75,76].

4. Docking protocol validation

- Perform redocking of the co-crystallized ligand and require a root-mean-square deviation (RMSD) ≤ 2.0 Å to validate the methodology.

- Use positive controls (known inhibitors) and negative controls (decoys), and evaluate the protocol’s ability to separate actives from inactives (AUC, enrichment factor, EF).

- Report full parameters: software and version, grid size, exhaustiveness, number of runs, etc. [77,78,79].

5. Critical analysis of results

- Do not select candidates solely by score; examine interactions, geometry, and chemical plausibility.

- Visualize hydrogen bonds, hydrophobic contacts, π–π interactions, and salt bridges, and analyze pose clusters.

- When resources allow, refine the top candidates using short molecular dynamics simulations (5–20 ns) or rescoring with MM-GBSA/MM-PBSA [80,81,82].

6. Final prioritization of candidates

- Combine calculated affinity with pose stability and the presence of specific interactions relevant to the target.

- Filter according to ADMET properties and discard clearly reactive or problematic compounds.

- Avoid candidates with extreme lipophilicity (e.g., LogP > 6) or unstable geometry, and advance only those that clearly justify experimental validation (MIC, enzymatic assays, etc.) [83,84,85].Finally, docking should be interpreted as a hypothesis generating prioritization step rather than a standalone proof of bioactivity. Top-ranked compounds should then be advanced to orthogonal experimental validation when feasible, through target-level biochemical/biophysical assays, and in all cases through antimicrobial phenotypic testing (e.g., MIC, IC50 or growth/viability readouts) with appropriate positive controls and concentration ranges compatible with solubility. This closes the loop from in silico ranking to actionable, experimentally supported candidates.

However, several limitations should be acknowledged, along with strategies to balance comprehensiveness and objectivity. Despite their power, multi-omics pipelines are susceptible to biases that can inflate confidence if not explicitly controlled. At the data level, batch effects, uneven sampling depth, missing values, and heterogeneous acquisition settings can distort integrative analyses, while annotation uncertainty may propagate through networks and correlation-based links. At the interpretation level, co-expression and co-accumulation relationships are not inherently causal, and integrative models can overfit when the same datasets are used for both model selection and performance assessment without independent validation [57,58,60]. In silico prioritization also carries a non-trivial false-positive risk: docking scores are sensitive to target selection, protein flexibility, solvation, and scoring-function limitations, and therefore may not correlate directly with experimental potency [56].

To mitigate these issues, we recommend:

- rigorous quality control and batch-aware processing.

- transparent reporting of annotation confidence and model uncertainty.

- conservative, pre-defined filtering criteria, and sensitivity analyses.

- orthogonal validation with appropriate controls (bioassays, chemical standards, or target-level assays when feasible) before making strong functional claims [56,57,58,60].

Together, these practices improve robustness and reproducibility.

5. From Induction to Application: Experimental and Translational Frameworks

5.1. Elicitation and Culture Systems for Metabolite Production

Having established throughout this review that stressors enhance the biosynthesis of specialized metabolites [8], the next step is to address how to quantify them and how to achieve controlled, scalable production of metabolites of interest [86]. A nice peak in the chromatogram is not a result, but a promise; for a metabolite to advance as an antimicrobial candidate it must become tangible, reproducible and available in sufficient quantities to be evaluated rigorously. In plant cell and tissue cultures, elicitors are the signals that “trick” cultures into activating their defense pathways [87,88].

This approach is particularly powerful with key hormones: methyl jasmonate (MeJA) and salicylic acid (SA) are among the most reliable elicitors to switch on metabolite pathways in cell and tissue cultures and boost metabolite production [89]. Likewise, biotic elicitors such as chitosan (derived from fungal chitin) have been established as potent inducers [90]. Recent reviews already provide both useful dose ranges and common pitfalls (e.g., non-linear dose–response curves, narrow temporal windows) [87,89,90]. In general, MeJA/SA tend to trigger phenolic and terpenoid pathways with good outcomes, whereas chitosan offers an economical, biocompatible route that can also improve tolerance and performance of the system being scaled up [89,90].

The true impact of elicitation is realized when it is combined with biotechnological culture platforms. Instead of relying on field harvests (highly variable), production is shifted to in vitro culture systems such as cell suspension cultures, organ cultures (e.g., hairy roots or adventitious roots) and bioreactors [91,92]. These systems offer scalability and tight control. Bioreactors (cultivation tanks), for example, are being optimized for large-scale root cultures, enabling continuous industrial production of specialized metabolites independent of climatic conditions [93,94]. Hairy roots, generated via transformation with Rhizobium rhizogenes, combine biosynthetic stability with compatibility with various bioreactor formats (temporary immersion, mist systems, etc.), and have shown competitive yields for complex phytocompounds [92,94].

Thus, this section functions as the first decisive filter: here we define what to elicit, in which culture system and under which parameters. These decisions determine the amount, reproducibility and comparability of the biomass, and everything that follows formulation, stability and antimicrobial validation will depend on three foundations being consolidated at this initial stage: sufficient production, clear traceability and consistency between batches [88].

5.2. Extraction, Formulation, Stability and Assay Panels Against Phytopathogens

The previous section showed how to obtain cellular biomass, but this raw material now needs to be processed so that it becomes useful, stable and comparable. As we already know, a nice peak in the chromatogram is not a result but a promise; for a metabolite to progress as an antimicrobial candidate, we must first make sure we extract it properly, “dress” it so that it survives, and demonstrate that it works. In plant cell and tissue systems, this means bringing the molecule from the culture flask to formats that can be tested reproducibly in bioassays.

The first challenge we face is extraction. We must first decide what we want (a fraction/a target compound) and then how to obtain it: if the candidate is volatile, we avoid heat; if it is phenolic, we protect pH and compatibility with LC/GC. Moving away from toxic organic solvents, the modern approach is “green extraction” [95], which uses technologies such as microwave-assisted extraction (MAE) [96], ultrasound-assisted extraction (UAE) [97] or supercritical CO2 extraction [98]. These methods stand out for their yields and reduced environmental footprint; they already have well-standardized protocols and, importantly, open the door to developing new biocompatible solvents, such as natural deep eutectic solvents (NADES), which are highly effective for selectively extracting phytochemicals [99,100,101].

The next challenge is formulation: how to deliver these compounds to where they can actually act. Most antimicrobial metabolites (such as those in Table 2) are hydrophobic and unstable—that is, they do not mix well with water and degrade rapidly—making direct use difficult. For this reason, a major current focus is on finding delivery systems and encapsulation strategies—vehicles capable of encapsulating and protecting them [102,103]. The most promising strategies include nanoemulsions (often produced by ultrasound) [104,105,106], liposomes [107] and cyclodextrin inclusion complexes [108]; these systems improve solubility, stabilize the compound and enhance its antimicrobial activity. Nevertheless, in laboratories with tight budgets or in early exploratory assays, surfactants such as Tween 80 offer a practical alternative: they solubilize the hydrophobic compound, provide minimal stabilization and allow preliminary testing without advanced systems [109].

Once the metabolite has been produced, extracted and formulated, the remaining step is validation. This is the point at which methods become less uniform and differences between studies become more evident. Therefore, to ensure that results are comparable, it is essential to adhere to a standardized assay panel:

- How to measure it (comparability)

- Core metric: MIC by broth microdilution.

- Standards: CLSI (M07, M27, M38) and EUCAST [110,111,112].

- Combinations: FICI via checkerboard assays [113].

- Frequent pitfalls (main sources of noise)

- Inconsistent units: µg/mL vs. % v/v.

- Irregular reporting of MIC90.

- Variation in vehicles: DMSO, ethanol and Tween 80 must be fixed and reported.

- Require n ≥ 3 biological replicates.

- Advanced metrics

- Biofilms: MBIC/MBEC [114].

- Quorum sensing: reporter strains (e.g., Chromobacterium violaceum) [115].

- Phytopathogens: progress from plate assays to detached-leaf tests or whole-plant systems [116].

5.3. From Lab to Field: Translational Challenges and the Bryophyte Frontier

We now move to the real challenge: going from the flask to the field. As discussed in previous sections, a nice peak is not a product. We know we can produce and formulate metabolites in the laboratory, but the translational gap is the “final boss” where most candidates fail. To move forward, regulatory agencies demand three clear elements: chemical identity and batch-to-batch consistency, safety (for humans and the environment), and efficacy under realistic conditions.

For agricultural use as a “biopesticide”, one must navigate the rigorous frameworks of agencies such as the EPA in the United States (which regulates biochemical pesticides) and the European procedure for “basic substances” under Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009, alongside OECD guidance for botanical active substances used in plant protection products [117,118,119]. Beyond regulatory compliance, translational deployment must also address formulation stability, batch-to-batch variability, and efficacy under realistic conditions constraints widely discussed for plant-derived biopesticides such as essential oils [120].

For pharmaceutical use, botanical products must comply with drug-development regulations. The FDA guidance on botanical drug development emphasizes rigorous chemistry, manufacturing and controls (CMC), batch-to-batch consistency, GMP, and staged nonclinical/clinical evaluation via IND/NDA pathways requirements that are distinct from agricultural registration and should therefore be considered independently [121].

The next challenge is to find genuinely novel chemical sources. Much of the research has traditionally focused on angiosperms (flowering plants). This is where bryophytes (mosses and liverworts) emerge as an underexplored frontier [122]. Their value is not only historical or taxonomic; it is chemical and functional. Mosses and liverworts bring together two qualities that are hard to find in combination: unusual chemistry and highly inducible defense responses. Despite their small size, bryophytes possess a unique and powerful chemical repertoire, rich in terpenoids, bisbibenzyls and phenolic compounds, with antimicrobial activity against Candida, Staphylococcus and even oomycetes [123,124]. Recent syntheses focusing on bryophyte essential oils and volatile compounds further underscore this underexplored chemical space [125]. Clearly, much remains to be discovered in these lineages, which makes them particularly attractive; many of their biosynthetic pathways remain mysterious at the gene level, opening the door to multi-omics discovery strategies [119,126].

Crucially, bryophytes also respond to stress (abiotic and biotic) by reprogramming their metabolism [127]. In fact, evolutionarily ancient lineages such as mosses and liverworts have developed unique pigment/flavonoid classes such as auronidins, which do not occur in flowering plants and are implicated in defense, cell wall modification and stress tolerance [128,129]. The appearance of auronidins is often a sign that the defense system has been activated; this is important because it provides a useful signal to schedule sampling (0–6–24–48 h) and capture precisely the time windows in which genes and metabolites begin to respond.

This metabolic plasticity, combined with their suitability for in vitro culture (as in our model P. replicatum), which exhibits full desiccation tolerance and strong responses to inducers [130], allows us to control when to trigger metabolic peaks. Moreover, recent studies in bryophyte models (Marchantia, Physcomitrium) reveal lipid and phenolic profiles rich enough to fully justify the growing interest in these systems: there is substantial chemical diversity to explore, and current tools (GNPS, SIRIUS, Spec2Vec and modern analytical workflows) will allow this space to be mapped with precision [51,66,131,132].

5.4. HLB as a Proof of Concept: When the Pathogen Does Not Grow on Plates

Finally, to illustrate the power of the multi-omics pipeline described in this review, we apply it to one of the most urgent and difficult phytosanitary challenges (a true wicked problem): Huanglongbing (HLB), or citrus greening disease. This disease, primarily associated with the fastidious bacterium Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus (CLas) [71], has become practically pandemic, causing losses in yield, fruit quality and orchard viability that threaten the sustainability of the citrus industry in key regions of the Americas, Asia and the Mediterranean [71]. In this scenario, the debate is no longer whether the economic impact is important, but rather how long citrus cultivation will remain profitable without innovative management strategies.

The challenge of controlling HLB is twofold. First, CLas is a Gram-negative α-proteobacterium that is unculturable in standard laboratory media and strictly confined to the phloem, where it is protected from topical treatments and transmitted by the Asian citrus psyllid Diaphorina citri [72]. Second, the inability to culture CLas prevents the application of a classical antibiotic discovery scheme: there are no Petri dishes with CLas, no growth curves on which to test compound libraries. This makes the “assay panel” described in Section 5.2 insufficient on its own for the discovery of new drugs.

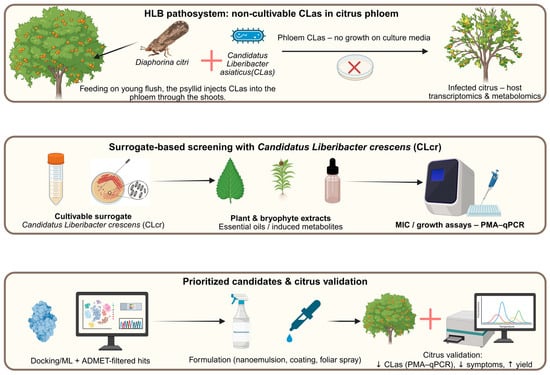

This is precisely where the multi-omics pipeline becomes essential (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Conceptual multi-omics pipeline for Huanglongbing (HLB): top panel, non-cultivable Candidatus Liberibacter asiaticus (CLas) in citrus phloem, transmitted by Diaphorina citri; middle panel, surrogate screening with cultivable Candidatus Liberibacter crescens (CLcr) and plant/bryophyte extracts to identify inhibitory candidates; bottom panel, prioritized hits formulated (nanoemulsions, coatings, sprays) and validated in infected citrus (PMA-qPCR, symptoms, yield).

To overcome the obstacle of an unculturable pathogen, there are two complementary strategies: (i) reconstruct its biology from host omics (transcriptomics and metabolomics of infected citrus) and (ii) develop cultivable surrogate models that allow screening assays and mechanistic studies. In this context, research has focused on Candidatus L. crescens BT-1 (CLcr), the first cultivable member of the Liberibacter genus [73].

This microorganism shares a substantial core of essential functions and genome organization with pathogenic Liberibacter species and has been proposed as a surrogate model for basic biology, functional genomics and antimicrobial screening [73]. Inhibition assays, mutagenesis and metabolic network analyses in L. crescens make it possible to explore targets and pathways whose direct manipulation in CLas would be unfeasible, but which can be extrapolated by orthology and pathway conservation. Recent work with natural products exemplifies how this strategy is implemented.

On one hand, plant extracts and metabolites produced by citrus endophytes have been evaluated using systems that combine in vitro assays with viability analysis by PMA-qPCR on leaf discs from infected trees. These studies show that extracts from aromatic plants (e.g., oregano, cinnamon, turmeric, thyme) and metabolites produced by endophytes such as Bacillus amyloliquefaciens significantly reduce CLas viability in plant, following a workflow that closely mirrors our pipeline: initial screening in cultivable models, followed by validation in infected citrus tissues [72].

On the other hand, recent studies have gone a step further: they have used spatial metabolomics to map chemicals in citrus tissues, employed L. crescens as a proxy for in vitro screening, and validated the hits in infected roots. Based on these spatial maps, metabolic modeling and in vitro assays, it was demonstrated that ferulic acid and several citrus flavonoids are highly bactericidal against CLas, with potency comparable to oxytetracycline, and that they also inhibit L. crescens growth in diffusion assays [74]. In essence, the process begins with the diseased tree, identifies candidate metabolites via omics and then validates their activity using a cultivable model organism together with assays in infected systems, following the same pipeline proposed in this review.

This case study with “difficult” pathogens shows that the overall strategy must change. We need to integrate elicitation, explore new chemical sources (such as bryophytes) and use multi-omics pipelines to identify and validate compounds in silico and in vitro, adopting “green” and sustainable development strategies [75]. In this context, bryophytes fit naturally. The same scheme applied to the citrus microbiome and the metabolome of infected trees can be extended to mosses such as P. replicatum: inducing them with defense phytohormones (SA, ABA, JA), capturing the transcriptomic–metabolomic window, prioritizing biosynthetic pathways associated with antimicrobial metabolites and, finally, testing those extracts or enriched fractions against L. crescens.

Integrating these results with docking and ML/QSAR models against essential CLas targets would yield a “shortlist” of candidate molecules filtered by theoretical affinity, ADMET properties and sustainability criteria (Box 1). These molecules could in turn be validated in infected citrus systems, replicating the logic already demonstrated for ferulic acid and flavonoids [73,74]. In this way, HLB serves not only as a citrus case where new alternatives are urgently needed, but also as proof that multi-omics combinations, stress priming and formulation of natural products can offer realistic routes to more sustainable therapies.

For underexplored chemical sources such as bryophytes, these systems provide fertile ground where the goal is not to compete with already described citrus compounds, but to add information to the repertoire of antimicrobial and defense-modulating metabolites that, together, may enable the design of integrated strategies against unculturable pathogens such as CLas.

6. Conclusions and Perspectives

This review has traced a path from the global crisis of antimicrobial resistance (AMR) to plants and, in particular, bryophytes as reservoirs of defensive metabolites. Recent evidence shows that many of these compounds are not static, but the result of stress-triggered metabolic reprogramming finely regulated by hormonal networks (SA, JA/ET, ABA) and transcription factors that respond to biotic and abiotic cues. Understanding this logic allows us to move beyond “trial-and-error” elicitation and toward more rational treatments aimed at activating specific pathways and chemotypes of interest.

Chemically, much of the actual diversity is concentrated in a few major superfamilies—terpenoids, phenylpropanoids, alkaloids and saponins—but their mechanisms of action are varied and often complementary: membrane permeabilization, cell wall disorganization, interference with biofilms and quorum sensing, inhibition of enzymatic targets or efflux pumps, among others. The literature suggests a complex reality in which the apparent antimicrobial potency depends not only on the metabolite type, but also on context: genotype, tissue, developmental stage, stress regime, extraction method and formulation. On top of this, the lack of standardization in units, controls and metrics (MIC, MBIC, FICI, % reduction in disease severity) remains a major obstacle for comparing studies and objectively prioritizing candidates.

The multi-omics component offers a way forward. Integrating RNA-seq with LC/GC-MS, molecular networking and in silico tools (metabolite annotation, docking, ML/QSAR models) can help connect biosynthetic genes with specialized metabolites and measurable antimicrobial phenotypes, instead of merely accumulating long lists of genes and chromatographic peaks. The key challenge is to filter noise to uncover causal relationships. The pipeline proposed here focuses on identifying functional gene–metabolite pairs, supported by co-expression and co-accumulation. This approach helps to discard experimental noise, narrow down the number of candidates and facilitate the transition into formulation stages (nanoemulsions, liposomes, green extraction) and testing in complex systems.

Bryophytes emerge in this context as a relatively unexplored but particularly promising chemical space. Their extreme desiccation tolerance and the ease with which their responses can be induced by phytohormones or controlled stresses make them ideal models to study how stress priming reshapes the metabolome. Species such as P. replicatum illustrate how combinations of treatments (SA, JA, ABA), multi-omics and bioassays can reveal metabolites with activity comparable or complementary to reference essential oils, with the added advantage of providing novel structures that are less exploited by industry.

The case of Huanglongbing (HLB) encapsulates the relevance of this approach for difficult phytosanitary problems, where the main pathogen is unculturable and current control schemes are unsustainable. In this scenario, the combination of metabolomics in citrus, the use of L. crescens as a surrogate model, and the validation of natural compounds has shown that it is possible to identify molecules with potency comparable to currently used antibiotics. Extending this logic to metabolites derived from bryophytes or other plant sources integrating stress design, omics, in vitro screening and testing in infected systems opens a realistic path toward greener and more resilient management strategies.

Looking ahead, the challenge is no longer to prove that plants and bryophytes can produce potent antimicrobial metabolites, but to build reproducible pipelines that integrate rational elicitation design, multi-omics and network analysis, quantitative and standardized bioassays, formulations that optimize stability, and evaluation in agricultural and clinical scenarios within a One Health framework. Progress along these lines will help ensure that the molecules reviewed here cease to be merely laboratory examples and become components of integrated strategies to confront resistant and unculturable pathogens, contributing to a transition toward more sustainable antimicrobials with a lower ecological footprint.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.E.P.-S. Writing—original draft, L.M.A.-G., A.M.-M., M.A.V.-L. and S.R.-M. review and editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

A.M.-M. extend thanks to SIP-IPN grant 20250351, M.A.V.-L. extend thanks to SIP-IPN grants 20242335 and 20250259, S.R.-M. extend thanks to SIP-IPN grants (20241319 and 20250213). L.E.P.-S. (CVU 1122288) and L.M.A.-G. (CVU 280116) extends thanks to SECIHTI and BEIFI-IPN fellowships.

Data Availability Statement

Dataset is available on request from the authors.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank the institutional support provided during this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Murray, C.J.L.; Ikuta, K.S.; Sharara, F.; Swetschinski, L.; Aguilar, G.R.; Gray, A.; Bisignano, C.; Rao, P.; Wool, E.; Johnson, S.C.; et al. Global Burden of Bacterial Antimicrobial Resistance in 2019: A Systematic Analysis. Lancet 2022, 399, 629–655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Global Leaders Group on Antimicrobial Resistance. Report to the United Nations General Assembly (2024); Global Leaders Group on Antimicrobial Resistance: Geneva, Switzerland, 2024; Available online: https://amrleaders.org/resources (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Woo, J.; Ku, J.M.; Lee, J.W.; Im, J.E.; Oh, S. Recent Advances in the Discovery of Plant-Derived Antimicrobials. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2023, 40, 1271–1290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khwaza, V.; Khan, F.R.; Mtshali, T.; Aderibigbe, B.A.; Oyedeji, O.O. Antibacterial Activity of Selected Essential Oil Components and Their Derivatives: A Review. Antibiotics 2025, 14, 68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maggio, F.; Rossi, C.; Serio, A.; Chaves-Lopez, C.; Casaccia, M.; Paparella, A. Anti-biofilm Mechanisms of Action of Essential Oils by Targeting Genes Involved in Quorum Sensing, Motility, Adhesion, and Virulence: A Review. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2025, 426, 110874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Usai, F.; Di Sotto, A. trans-Cinnamaldehyde as a Novel Candidate to Overcome Bacterial Resistance: An Overview of In Vitro Studies. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irizar, A.; Zarraonaindia, I.; Goñi-de-Cerio, F. Phototoxicity and Skin Damage: A Review of Adverse Effects of Some Furocoumarins Found in Natural Extracts. Toxicology 2025, 520, 154086. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grosu, C.; Matei, C.; Ion, R.M.; Georgescu, A.; Constantinescu, R.; Draghici, C. New Insights Concerning Phytophotodermatitis Induced by Plants. Life 2024, 14, 1019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeshi, K.; Crayn, D.; Ritmejerytė, E.; Wangchuk, P. Plant Secondary Metabolites Produced in Response to Abiotic Stress. Molecules 2022, 27, 313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cerri, L.; Parri, S.; Dias, M.C.; Fabiano, A.; Romi, M.; Cai, G.; Cantini, C.; Zambito, Y. Olive Leaf Extracts from Three Italian Olive Cultivars Exposed to Drought Stress Differentially Protect Cells against Oxidative Stress. Antioxidants 2024, 13, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinkela Devčić, M.; Pašković, I.; Kovač, Z.; Tariba Knežević, P.; Morelato, L.; Glažar, I.; Simonić-Kocijan, S. Antimicrobial Activity of Olive Leaf Extract to Oral Candida Isolates. Microorganisms 2024, 12, 1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Căpruciu, R. Resveratrol in Grapevine Components, Products and By-Products—A Review. Horticulturae 2025, 11, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- D’Hallewin, G.; Schirra, M.; Manueddu, E.; Piga, A.; Ben-Yehoshua, S. Scoparone and Scopoletin Accumulation and Ultraviolet-C Induced Resistance to Postharvest Decay in Oranges as Influenced by Harvest Date. J. Am. Soc. Hortic. Sci. 1999, 124, 702–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.J.; Ben-Yehoshua, S.; Shapiro, B.; Henis, Y.; Carmeli, S. Accumulation of Scoparone in Heat-Treated Lemon Fruit Inoculated with Penicillium digitatum Sacc. Plant Physiol. 1991, 97, 880–885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heydari, M.; Zanfardino, A.; Taleei, A.; Shahnejat Bushehri, A.A.; Hadian, J.; Maresca, V.; Sorbo, S.; Di Napoli, M.; Varcamonti, M.; Basile, A.; et al. Effect of Heat Stress on Yield, Monoterpene Content and Antibacterial Activity of Essential Oils of Mentha x piperita var. Mitcham and Mentha arvensis var. piperascens. Molecules 2018, 23, 1903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ravi, B.; Foyer, C.H. The Integration of Reactive Oxygen Species (ROS) and Calcium Signalling in Abiotic Stress Responses. Plant Cell Environ. 2023, 46, 1985–2006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sana, S.; Aftab, T.; Naeem, M.; Jha, P.K.; Prasad, P.V.V. Production of secondary metabolites under challenging environments: Understanding functions and mechanisms of signalling molecules. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1569014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramírez-Zavaleta, C.Y.; Santamaría, J.M.; Pimentel-Vera, S.M.; López-Pérez, M.; Castro-Concha, L.A. An Overview of Plant PRR- and NLR-Mediated Immunities and the Role of Their Emerging Integrations. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12974. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, X.Q.; Wu, D.; Ma, J.F. PTI–ETI synergistic signal mechanisms in plant immunity. Plant Biotechnol. J. 2024, 22, 2113–2128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Orf, I.; Tenenboim, H.; Omranian, N.; Nikoloski, Z.; Fernie, A.R.; Lisec, J.; Brotman, Y.; Bromke, M.A. Transcriptomic and Metabolomic Analysis of a Pseudomonas-Resistant versus a Susceptible Arabidopsis Accession. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2022, 23, 12087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahan, M.A.; Harris, B.; Lowery, M.; Coburn, K.; Infante, A.M.; Percifield, R.J.; Ammer, A.G.; Kovinich, N. Glyceollin Transcription Factor GmMYB29A2 Regulates Soybean Resistance to Phytophthora sojae. Plant Physiol. 2020, 183, 530–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jahan, M.A.; Harris, B.; Lowery, M.; Coburn, K.; Infante, A.M.; Percifield, R.J.; Ammer, A.G.; Kovinich, N. The NAC Family Transcription Factor GmNAC42-1 Regulates Biosynthesis of the Anticancer and Neuroprotective Glyceollins in Soybean. BMC Genom. 2019, 20, 149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Bona, G.S.; Vincenzi, S.; De Marchi, F.; Angelini, E.; Bertazzon, N. Chitosan Induces Delayed Grapevine Defense Mechanisms and Protects Grapevine against Botrytis cinerea. J. Plant Dis. Prot. 2021, 128, 715–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zavaliev, R.; Dong, X. NPR1, a Key Immune Regulator for Plant Survival under Biotic and Abiotic Stresses. Mol. Cell 2024, 84, 131–141. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spoel, S.H.; Dong, X. Salicylic Acid in Plant Immunity and Beyond. Plant Cell 2024, 36, 1451–1464. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Johnson, L.Y.D.; Major, I.T.; Chen, Y.; Yang, C.; Vanegas-Cano, L.J.; Howe, G.A. Diversification of JAZ-MYC Signaling Function in Immune Metabolism. New Phytol. 2023, 239, 2277–2291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Aerts, N.; Mendes, M.P.; Van Wees, S.C.M. Multiple Levels of Crosstalk in Hormone Networks Regulating Plant Defense. Plant J. 2021, 105, 489–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, P.; Jackson, E.; Li, X.; Zhang, Y. Salicylic Acid and Jasmonic Acid in Plant Immunity. Hortic. Res. 2025, 12, uhaf082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melotto, M.; Fochs, B.; Jaramillo, Z.; Rodrigues, O. Fighting for Survival at the Stomatal Gate. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2024, 75, 551–577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, J.; Wang, X.; He, Y.; Sang, T.; Wang, P.; Dai, S.; Zhang, S.; Meng, X. Differential Phosphorylation of the Transcription Factor WRKY33 by the Protein Kinases CPK5/CPK6 and MPK3/MPK6 Cooperatively Regulates Camalexin Biosynthesis in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2020, 32, 2621–2638. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Gao, Z.; Zhang, H.; Yang, Y.; Yang, X.; Zhao, X.; Guo, H.; Nagalakshmi, U.; Li, D.; Dinesh-Kumar, S.P.; et al. The MAPK–AL7 Module Negatively Regulates ROS Homeostasis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2023, 120, e2214750120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.N.; Kim, S.G.; Kim, H.; Kim, S.J.; Cho, K.-M.; Kim, Y.; Lee, D.S.; Lee, M.-H.; Kim, S.Y.; Hong, J.C.; et al. ORA59 Exhibits Dual DNA-Binding Specificity that Differentially Regulates JA- and ET-Induced Genes in Plant Immunity. Plant Physiol. 2021, 187, 2763–2784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yan, H.; Pei, X.; Zhang, H.; Li, X.; Zhang, X.; Zhao, M.; Chiang, V.L.; Sederoff, R.R.; Zhao, X. MYB-Mediated Regulation of Anthocyanin Biosynthesis. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, Y.; Liu, M.; Chen, X. Research Progress in Understanding the Biosynthesis and Regulation of Anthocyanins in Horticultural Plants. Sci. Hortic. 2023, 321, 112374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Kong, D.; Fu, Y.; Sussman, M.R.; Wu, H. The Role of Genotype, Developmental Stage, and Environmental Factors in Regulating Secondary Metabolism in Medicinal Plants. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2020, 148, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fernández-Conradi, P.; Defossez, E.; Delavallade, A.; Descombes, P.; Pitteloud, C.; Glauser, G.; Pellissier, L.; Rasmann, S. The Effect of Community-Wide Phytochemical Diversity on Herbivory Reverses from Low to High Elevation. J. Ecol. 2022, 110, 46–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaou, N.; Stavropoulou, E.; Karantonis, H.C.; Tsigalou, C.; Bezirtzoglou, E. Towards Advances in Medicinal Plant Antimicrobial Activity: A Review Study on Challenges and Future Perspectives. Microorganisms 2021, 9, 2041. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nguyen, T.L.A.; Bhattacharya, D.; Park, K.M. Antimicrobial Activity of Quercetin: An Approach to Its Mechanistic Principle. Molecules 2022, 27, 2494. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, Y.; Ge, X. Berberine Inhibits the MFS Efflux Pump MdfA in E. coli. Microbiol. Spectr. 2023, 11, e03324-22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, K.; Kang, S.; Guo, M.; Shen, C.; Wang, L.; Xia, X.; Lü, X.; Shi, C. Evaluation of the Antibacterial Mechanism and Biofilm Removal Effect of Eugenol on Vibrio vulnificus and Its Application in Fresh Oysters. Food Biosci. 2022, 50, 102103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sitarek, P.; Merecz-Sadowska, A.; Sikora, J.; Dudzic, M.; Wiertek-Płoszaj, N.; Picot, L.; Śliwiński, T.; Kowalczyk, T. Flavonoids and Their Derivatives as DNA Topoisomerase Inhibitors: A Comprehensive Review. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 209, 107457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Rossi, L.; Rocchetti, G.; Lucini, L.; Rebecchi, A. Antimicrobial Potential of Polyphenols: Mechanisms and Applications. Antioxidants 2025, 14, 200. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majumdar, G.; Mandal, S. Evaluation of Broad-Spectrum Antibacterial Efficacy of Quercetin by Molecular Docking, Molecular Dynamics Simulation and In Vitro Studies. Chem. Phys. Impact 2024, 8, 100501. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Duda-Madej, A.; Viscardi, S.; Bazan, H.; Sobieraj, J. Exploring the Role of Berberine as a Molecular Disruptor in Antimicrobial Strategies. Pharmaceuticals 2025, 18, 947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, S.; Yang, K.; Hong, Y.; Gong, Y.; Ni, J.; Yang, N.; Ding, W. A New Perspective on the Antimicrobial Mechanism of Berberine Hydrochloride Against Staphylococcus aureus Revealed by Untargeted Metabolomic Studies. Front. Microbiol. 2022, 13, 917414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shakeel, A.; Noor, J.J.; Jan, U.; Gul, A.; Handoo, Z.; Ashraf, N. Saponins, the Unexplored Secondary Metabolites in Plant Defense: Opportunities in Integrated Pest Management. Plants 2025, 14, 861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Maione, A.; Imparato, M.; Galdiero, M.; Alteriis, E.D.; Feola, A.; Galdiero, E.; Guida, M. β-Escin Alone or Combined with Antifungals against Candida glabrata Biofilms: Mechanisms of Action. Antibiotics 2023, 12, 1210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paluch, E.; Bortkiewicz, O.; Widelski, J.; Duda-Madej, A.; Gleńsk, M.; Nawrot, U.; Lamch, Ł.; Długowska, D.; Sobieszczańska, B.; Wilk, K.A. A Combination of β-Aescin and Newly Synthesized Alkylamidobetaines as Modern Components Eradicating the Biofilms of Multidrug-Resistant Clinical Strains of Candida glabrata. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 2541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yu, J.S.; Kwak, Y.B.; Kee, K.H.; Wang, M.; Kim, D.H.; Dorrestein, P.C.; Kang, K.B.; Yoo, H.H. A Versatile Toolkit for Drug Metabolism Studies with GNPS2: From Drug Development to Clinical Monitoring. Nat. Protoc. 2025, 1–35. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takeda, H.; Matsuzawa, Y.; Takeuchi, M.; Takahashi, M.; Nishida, K.; Harayama, T.; Todoroki, Y.; Shimizu, K.; Sakamoto, N.; Oka, T.; et al. MS-DIAL 5 Multimodal Mass Spectrometry Data Mining Unveils Lipidome Complexities. Nat. Commun. 2024, 15, 9903. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dührkop, K.; Nothias, L.-F.; Fleischauer, M.; Reher, R.; Ludwig, M.; Hoffmann, M.A.; Petras, D.; Gerwick, W.H.; Rousu, J.; Dorrestein, P.C.; et al. Systematic Classification of Unknown Metabolites Using High-Resolution Fragmentation Mass Spectra. Nat. Biotechnol. 2021, 39, 462–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Plaszkó, T.; Szűcs, Z.; Vasas, G.; Gonda, S. Effects of Glucosinolate-Derived Isothiocyanates on Fungi: Mechanisms & QSAR. J. Fungi 2021, 7, 539. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoch, C.C.; Shoykhet, M.; Weiser, T.; Griesbaum, L.; Petry, J.; Hachani, K.; Multhoff, G.; Dezfouli, A.B.; Wollenberg, B. Isothiocyanates in Medicine: A Comprehensive Review on Phenylethyl-, Allyl-, and Benzyl-Isothiocyanates. Pharmacol. Res. 2024, 201, 107107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nowicki, D.; Krause, K.; Szamborska, P.; Żukowska, A.; Cech, G.M.; Szalewska-Pałasz, A. Induction of the Stringent Response Underlies the Antimicrobial Action of Aliphatic Isothiocyanates. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 591802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jukič, M.; Bren, U. Machine Learning in Antibacterial Drug Design. Front. Pharmacol. 2022, 13, 864412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simoben, C.V.; Babiaka, S.B.; Moumbock, A.F.A.; Namba-Nzanguim, C.T.; Eni, D.B.; Medina-Franco, J.L.; Günther, S.; Ntie-Kang, F.; Sippl, W. Challenges in Natural Product-Based Drug Discovery Assisted with In Silico-Based Methods. RSC Adv. 2023, 13, 31578–31594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wolters, F.C.; Del Pup, E.; Singh, K.S.; Bouwmeester, K.; Schranz, M.E.; van der Hooft, J.J.J.; Medema, M.H. Pairing Omics to Decode the Diversity of Plant Specialized Metabolism. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2024, 82, 102657. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, K.S.; van der Hooft, J.J.J.; van Wees, S.C.M.; Medema, M.H. Integrative Omics Approaches for Biosynthetic Pathway Discovery in Plants. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2022, 39, 1876–1896. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Upton, R.N.; Correr, F.H.; Lile, J.; Reynolds, G.L.; Falaschi, K.; Cook, J.P.; Lachowiec, J. Design, Execution, and Interpretation of Plant RNA-seq Analyses. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1135455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsugawa, H.; Rai, A.; Saito, K.; Nakabayashi, R. Metabolomics and Complementary Techniques to Investigate the Plant Phytochemical Cosmos. Nat. Prod. Rep. 2021, 38, 1729–1759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bittremieux, W.; Wang, M.; Dorrestein, P.C. The Critical Role that Spectral Libraries Play in Capturing the Metabolomics Community Knowledge. Metabolomics 2022, 18, 94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schmid, R.; Petras, D.; Nothias, L.-F.; Wang, M.; Aron, A.T.; Jagels, A.; Tsugawa, H.; Rainer, J.; Garcia-Aloy, M.; Dührkop, K.; et al. Ion Identity Molecular Networking for Mass Spectrometry-Based Metabolomics in the GNPS Environment. Nat. Commun. 2021, 12, 3832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hoffmann, M.A.; Nothias, L.-F.; Ludwig, M.; Fleischauer, M.; Gentry, E.C.; Witting, M.; Dorrestein, P.C.; Dührkop, K.; Böcker, S. High-Confidence Structural Annotation of Metabolites Absent from Spectral Libraries. Nat. Biotechnol. 2022, 40, 411–421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmid, R.; Heuckeroth, S.; Korf, A.; Smirnov, A.; Myers, O.; Dyrlund, T.S.; Bushuiev, R.; Murray, K.J.; Hoffmann, N.; Lu, M.; et al. Integrative Analysis of Multimodal Mass Spectrometry Data in MZmine 3. Nat. Biotechnol. 2023, 41, 447–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tripathi, A.; Vázquez-Baeza, Y.; Gauglitz, J.M.; Wang, M.; Dührkop, K.; Nothias-Esposito, M.; Acharya, D.D.; Ernst, M.; van der Hooft, J.J.J.; Zhu, Q.; et al. Chemically Informed Analyses of Metabolomics Mass Spectrometry Data with Qemistree. Nat. Chem. Biol. 2021, 17, 146–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huber, F.; Ridder, L.; Rogers, S.; Verhoeven, S.; Spaaks, J.H.; Diblen, F.; van der Hooft, J.J.J. Spec2Vec: Improved Mass Spectral Similarity Scoring through Learned Structural Relationships. PLoS Comput. Biol. 2021, 17, e1008724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Jonge, N.F.; Louwen, J.J.R.; Chekmeneva, E.; Camuzeaux, S.; Vermeir, F.J.; Jansen, R.S.; Huber, F.; van der Hooft, J.J.J. MS2Query: Reliable and Scalable MS2 Mass Spectra-Based Analogue Search. Nat. Commun. 2023, 14, 1752. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yuan, X.; Smith, N.S.S.; Moghe, G.D. Analysis of Plant Metabolomics Data Using Identification-Free Approaches. Appl. Plant Sci. 2025, 13, e70001. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Agu, P.C.; Afiukwa, C.A.; Orji, O.U.; Ezeh, E.M.; Ofoke, I.H.; Ogbu, C.O.; Ugwuja, E.I.; Aja, P.M. Molecular Docking as a Tool for the Discovery of Molecular Targets of Nutraceuticals in Diseases Management. Sci. Rep. 2023, 13, 13398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bender, B.J.; Gahbauer, S.; Luttens, A.; Lyu, J.; Webb, C.M.; Stein, R.M.; Fink, E.A.; Balius, T.E.; Carlsson, J.; Irwin, J.J.; et al. A Practical Guide to Large-Scale Docking. Nat. Protoc. 2021, 16, 4799–4832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Trott, O.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock Vina: Improving the Speed and Accuracy of Docking with a New Scoring Function, Efficient Optimization, and Multithreading. J. Comput. Chem. 2010, 31, 455–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jumper, J.; Evans, R.; Pritzel, A.; Green, T.; Figurnov, M.; Ronneberger, O.; Tunyasuvunakool, K.; Bates, R.; Žídek, A.; Potapenko, A.; et al. Highly Accurate Protein Structure Prediction with AlphaFold. Nature 2021, 596, 583–589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Boyle, N.M.; Banck, M.; James, C.A.; Morley, C.; Vandermeersch, T.; Hutchison, G.R. Open Babel: An Open Chemical Toolbox. J. Cheminform. 2011, 3, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.; Chen, J.; Cheng, T.; Gindulyte, A.; He, J.; He, S.; Li, Q.; Shoemaker, B.A.; Thiessen, P.A.; Yu, B.; et al. PubChem 2019 Update: Improved Access to Chemical Data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2019, 47, D1102–D1109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Morris, G.M.; Huey, R.; Lindstrom, W.; Sanner, M.F.; Belew, R.K.; Goodsell, D.S.; Olson, A.J. AutoDock4 and AutoDockTools4: Automated Docking with Selective Receptor Flexibility. J. Comput. Chem. 2009, 30, 2785–2791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.Y.; Zhang, H.X.; Mezei, M.; Cui, M. Molecular Docking: A Powerful Approach for Structure-Based Drug Discovery. Curr. Comput.-Aided Drug Des. 2011, 7, 146–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, G.L.; Andrews, C.W.; Capelli, A.M.; Clarke, B.; LaLonde, J.; Lambert, M.H.; Lindvall, M.; Nevins, N.; Semus, S.F.; Senger, S.; et al. A Critical Assessment of Docking Programs and Scoring Functions. J. Med. Chem. 2006, 49, 5912–5931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gaillard, T. Evaluation of AutoDock and AutoDock Vina on the CASF-2013 Benchmark. J. Chem. Inf. Model. 2018, 58, 1697–1706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pagadala, N.S.; Syed, K.; Tuszynski, J. Software for Molecular Docking: A Review. Biophys. Rev. 2017, 9, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Genheden, S.; Ryde, U. The MM/PBSA and MM/GBSA Methods to Estimate Ligand-Binding Affinities. Expert Opin. Drug Discov. 2015, 10, 449–461. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Homeyer, N.; Gohlke, H. Free Energy Calculations by the Molecular Mechanics Poisson–Boltzmann Surface Area Method. Mol. Inform. 2012, 31, 114–122. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hollingsworth, S.A.; Dror, R.O. Molecular Dynamics Simulation for All. Neuron 2018, 99, 1129–1143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Daina, A.; Michielin, O.; Zoete, V. SwissADME: A Free Web Tool to Evaluate Pharmacokinetics, Drug-Likeness and Medicinal Chemistry Friendliness of Small Molecules. Sci. Rep. 2017, 7, 42717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baell, J.B.; Walters, M.A. Chemistry: Chemical Con Artists Foil Drug Discovery. Nature 2014, 513, 481–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lagorce, D.; Bouslama, L.; Becot, J.; Miteva, M.A.; Villoutreix, B.O. FAF-Drugs4: Free ADME-Tox Filtering Computations for Chemical Biology and Early Stages Drug Discovery. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 3658–3660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Razzaq, A.; Zafar, M.M.; Ali, A.; Ihsan, L.; Qadir, F.; Khan, M.; Zhang, Y.; Gao, L.; Cong, H.; Iqbal, R.; et al. Elicitor-Mediated Enhancement of Secondary Metabolites in Plant Species: A Review. Front. Plant Sci. 2025, 16, 1706600. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jeyasri, R.; Muthuramalingam, P.; Karthick, K.; Shin, H.; Choi, S.H.; Ramesh, M. Methyl jasmonate and salicylic acid as powerful elicitors for enhancing the production of secondary metabolites in medicinal plants: An updated review. Plant Cell Tissue Organ Cult. 2023, 153, 447–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemat, F.; Vian, M.A.; Cravotto, G. Green Extraction of Natural Products: Concept and Principles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2012, 13, 8615–8627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alcalde, M.A.; Perez-Matas, E.; Escrich, A.; Cusido, R.M.; Palazon, J.; Bonfill, M. Biotic Elicitors in Adventitious and Hairy Root Cultures: A Review from 2010 to 2022. Molecules 2022, 27, 5253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Özyiğit, I.I.; Doğan, İ.; Hocaoglu-Özyiğit, A.; Yalcin, B.; Erdogan, A.; Yalcin, I.E.; Cabi, E.; Kaya, Y. Production of Secondary Metabolites Using Tissue Culture-Based Biotechnological Applications. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1132555. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murthy, H.N.; Joseph, K.S.; Paek, K.Y.; Park, S.Y. Bioreactor Configurations for Adventitious Root Culture: Recent Advances toward the Commercial Production of Specialized Metabolites. Crit. Rev. Biotechnol. 2024, 44, 837–859. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdú-Navarro, F.; Moreno-Cid, J.A.; Weiss, J.; Egea-Cortines, M. The Advent of Plant Cells in Bioreactors. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1310405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirmazloum, I.; Slavov, A.K.; Marchev, A.S. The Untapped Potential of Hairy Root Cultures and Their Multiple Applications. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2024, 25, 12682. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sangwan, N.S.; Jha, G.K.; Mitra, A. Unlocking Nature’s Treasure Trove: Biosynthesis and Elicitation of Secondary Metabolites from Plants. Plant Growth Regul. 2024, 104, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eshawu, Y.; Ghalsasi, N. Metabolomics of Natural Samples: A Tutorial Review on the Extraction and Sample Preparation. J. Sep. Sci. 2024, 47, e2300588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chemat, F.; Rombaut, N.; Sicaire, A.-G.; Meullemiestre, A.; Fabiano-Tixier, A.-S.; Abert-Vian, M. Ultrasound Assisted Extraction of Food and Natural Products. Mechanisms, Techniques, Combinations, Protocols and Applications. A Review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2017, 34, 540–560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Ahmadi, K.; El Allaoui, H.; El Abdouni, A.; Bouhrim, M.; Eto, B.; Dira, I.; Shahat, A.A.; Herqash, R.N.; Haboubi, K.; El Bastrioui, M.; et al. A Bibliometric Analysis of the Supercritical CO2 Extraction of Essential Oils from Aromatic and Medicinal Plants: Trends and Perspectives. Horticulturae 2024, 10, 1185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hikmawanti, N.P.E.; Ramadon, D.; Jantan, I.; Mun’im, A. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents (NADES): Phytochemical Extraction Performance Enhancer for Pharmaceutical and Nutraceutical Product Development. Plants 2021, 10, 2091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bagade, S.B.; Patil, S.R. Recent Advances in Microwave Assisted Extraction of Bioactive Compounds from Complex Herbal Samples: A Review. Crit. Rev. Anal. Chem. 2021, 51, 138–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- García-Roldán, A.; Piriou, L.; Jauregi, P. Natural Deep Eutectic Solvents for Extraction of Polyphenols from Spent Coffee Grounds and Antioxidant Evaluation. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1072592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chamkhi, I.; Cheto, S.; Geistlinger, J.; Zeroual, Y.; Kouisni, L.; Bargaz, A.; Ghoulam, C. Essential-Oil Nanoemulsions in Crop Protection: From Lab to Field. Ind. Crops Prod. 2022, 183, 114958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, Q.; Huang, H.; Chen, H.; Lin, J.; Wang, Q. Food-Grade Nanoemulsions: Preparation, Stability and Applications. Molecules 2019, 24, 4242. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Yan, D.; Yang, R.; Man, Y.; Tang, H.; Yu, Q.; Shao, L. Liposome-Delivered Natural Antimicrobials: Recent Advances and Their Application in Food. Food Biosci. 2025, 64, 107525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alonso-Gato, M.; Astray, G.; Mejuto, J.C.; Simal-Gandara, J. Essential Oils as Antimicrobials in Crop Protection. Antibiotics 2021, 10, 34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Modarres-Gheisari, S.M.M.; Gavagsaz-Ghoachani, R.; Malaki, M.; Safarpour, P.; Zandi, M. Ultrasonic Nano-Emulsification—A Review. Ultrason. Sonochem. 2019, 52, 88–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reis, D.R.; Ambrosi, A.; Di Luccio, M. Encapsulated essential oils: A perspective in food preservation. Future Foods 2022, 5, 100126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wadhwa, G.; Kumar, S.; Chhabra, L.; Mahant, S.; Rao, R. Essential Oil–Cyclodextrin Complexes: An Updated Review. J. Incl. Phenom. Macrocycl. Chem. 2017, 89, 363–381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- CLSI. Methods for Dilution Antimicrobial Susceptibility Tests for Bacteria That Grow Aerobically (M07), 12th ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2024; Available online: https://clsi.org/standards/products/microbiology/documents/m07/ (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Botanical Drug Development: Guidance for Industry; Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER): Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2016. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/files/drugs/published/Botanical-Drug-Development--Guidance-for-Industry.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- CLSI. Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Filamentous Fungi (M38); Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2017; Available online: https://clsi.org/standards/products/microbiology/documents/m38/ (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- CLSI. Reference Method for Broth Dilution Antifungal Susceptibility Testing of Yeasts (M27), 4th ed.; Clinical and Laboratory Standards Institute: Wayne, PA, USA, 2017; Available online: https://clsi.org/standards/products/microbiology/documents/m27/ (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Thieme, L.; Hartung, A.; Tramm, K.; Klinger-Strobel, M.; Jandt, K.D.; Makarewicz, O.; Pletz, M.W. MBEC Versus MBIC: The Lack of Differentiation between Biofilm Reducing and Inhibitory Effects as a Current Problem in Biofilm Methodology. Biol. Proced. Online 2019, 21, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dimitrova, P.D.; Damyanova, T.; Paunova-Krasteva, T. Chromobacterium violaceum: A Model for Evaluating the Anti-Quorum Sensing Activities of Plant Substances. Sci. Pharm. 2023, 91, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doern, C.D. When Does 2 Plus 2 Equal 5? A Review of Antimicrobial Synergy Testing. J. Clin. Microbiol. 2014, 52, 4124–4128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quiroga-Cardona, J.; López-Monsalve, L.F.; Várzea, V.M.P.; Flórez-Ramos, C.P. Use of Detached Leaf Inoculation Method for the Early Screening of Coffee Genotypes with Resistance to Coffee Leaf Rust. Agronomy 2024, 14, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soni, M.; Yadav, A.; Maurya, A.; Das, S.; Dubey, N.K.; Dwivedy, A.K. Advances in Designing Essential Oil Nanoformulations: An Integrative Approach to Mathematical Modeling with Potential Application in Food Preservation. Foods 2023, 12, 4017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA). Pesticide Registration Manual: Chapter 3—Additional Considerations for Biopesticide Products; U.S. EPA: Washington, DC, USA, 2025. Available online: https://www.epa.gov/pesticide-registration/pesticide-registration-manual-chapter-3-additional-considerations (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- European Commission, Directorate-General for Health and Food Safety (DG SANTE). Working Document on the Procedure for Application of Basic Substances to Be Approved in Compliance with Article 23 of Regulation (EC) No 1107/2009; SANCO/10363/2012 rev.11; European Commission: Brussels, Belgium, 2023; Available online: https://www.efsa.europa.eu/sites/default/files/2023-08/pesticides-application-basic-substances-art-23.pdf (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD). Guidance Document on Botanical Active Substances Used in Plant Protection Products; OECD Series on Pesticides and Biocides, No. 90; OECD Publishing: Paris, France, 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, I.; Singh, R.; Muthusamy, S.; Sharma, M.; Grewal, K.; Singh, H.P.; Batish, D.R. Plant Essential Oils as Biopesticides: Applications, Mechanisms, Innovations, and Constraints. Plants 2023, 12, 2916. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- U.S. Food and Drug Administration (FDA). Botanical Drug Development: Guidance for Industry; FDA, Center for Drug Evaluation and Research (CDER): Silver Spring, MD, USA, 2020. Available online: https://www.fda.gov/regulatory-information/search-fda-guidance-documents/botanical-drug-development-guidance-industry (accessed on 13 December 2025).

- Nandy, S.; Dey, A. Bibenzyls and bisbibenzyls of bryophytic origin as promising source of novel therapeutics: Pharmacology, synthesis and structure-activity. Daru 2020, 28, 701–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]