Abstract

The interplay between phosphate (Pi) signaling and defense pathways is crucial for plant fitness, yet its molecular basis, particularly in wheat, remains poorly understood. Here, we functionally characterized the plasma membrane-localized high-affinity phosphate transporter TaPT3-2D and demonstrated its essential roles in Pi uptake, arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) symbiosis, and fungal disease resistance. Quantitative analyses showed that TaPT3-2D expression was strongly induced by AM colonization (165-fold increase) and by infection with Bipolaris sorokiniana (54-fold increase) and Gaeumannomyces tritici (15-fold increase). In contrast, virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) of TaPT3-2D reduced Pi uptake and mycorrhizal colonization. Moreover, TaPT3-2D-silenced plants exhibited increased susceptibility to biotrophic, hemibiotrophic, and necrotrophic fungi, accompanied by reduced expression of pathogen-related genes. The simultaneous impairment of Pi uptake, AM symbiosis, and defense responses in silenced plants indicates that TaPT3-2D functionally couples these processes. Functional complementation assays in low-Pi medium further revealed that TaPT3-2D partially rescued defective Pi uptake in mutant MB192 yeast, supporting its role as a high-affinity phosphate transporter. Collectively, these results identify TaPT3-2D as both a key regulator of individual pathways and as a molecular link connecting Pi homeostasis, symbiotic signaling, and disease resistance in wheat.

1. Introduction

As an essential macronutrient, inorganic phosphate (Pi) availability frequently limits the productivity of major cereal crops such as wheat, posing a significant challenge to global food security [1]. This limitation arises from its rapid fixation into insoluble complexes within the soil matrix, inherently low bioavailability, and spatially heterogeneous distribution in natural soil environments [2]. In response, plants have evolved a range of adaptive strategies to optimize Pi acquisition. These include (i) remodeling root system architecture to exploit heterogeneous soil Pi distributions; (ii) secreting acid phosphatases and phytases to hydrolyze organic phosphate esters and mobilize fixed Pi; (iii) establishing arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) symbioses to enhance Pi absorption via fungal hyphae; and (iv) inducing high-affinity phosphate transporters to facilitate Pi uptake under low-Pi conditions [2].

AM symbioses are evolutionarily conserved mutualistic relationships between Glomeromycotina fungi and more than 70% of extant vascular plant species [3,4]. Functional AM symbioses require host plants to allocate substantial amounts of photosynthetically derived carbon in the form of hexoses and C16:0 β-monoacylglycerol to intraradical fungal structures, sustaining fungal growth and development [5]. Reciprocally, AM fungi efficiently forage for and redistribute water and inorganic nutrients (e.g., Pi and nitrate) through extensive extraradical hyphal networks. These resources are delivered to host roots across symbiotic interfaces via specialized membrane-embedded transporter complexes [5].

Following host root penetration, intraradical hyphae traverse outer cortical cell layers and undergo extensive dichotomous branching to form specialized arbuscules within inner cortical cells [3]. These ephemeral branched structures establish dedicated symbiotic interfaces that facilitate bidirectional molecular signaling during symbiosis establishment and high-efficiency nutrient exchange during the mature arbuscular stage [4]. During arbuscule development, a plant-derived peri-arbuscular membrane (PAM) forms concentrically around the branching fungal hyphae, establishing a physical barrier that segregates the fungal symbiont from the host cytosol and concurrently functions as a dedicated symbiotic resource exchange interface [6]. The PAM is enriched in high-affinity proton-coupled phosphate transporters (predominantly PHT1-family proteins), which are strictly required for unidirectional Pi transfer from the fungus to the plant host [6,7].

The concerted transcriptional induction of multiple phosphate transporters constitutes a core adaptive response to Pi starvation in higher plants [8]. These plasma membrane-localized high-affinity transporters are rapidly upregulated under low-Pi conditions and serve as the primary mediators of Pi acquisition and redistribution, thereby maintaining systemic Pi homeostasis [8,9]. PHT1 orthologs have been identified in numerous plant species, including nine in Arabidopsis thaliana and 13 in Oryza sativa [10,11]. In A. thaliana, AtPT1, AtPT4, AtPT5, AtPT8, and AtPT9 perform distinct roles in Pi absorption and long-distance transport [12,13,14,15]. In rice, OsPT2, OsPT6, OsPT9, and OsPT10 predominantly mediate high-affinity Pi uptake from the rhizosphere during Pi deprivation [16,17]. Notably, the expression of OsPT9 and OsPT10 appears to be largely independent of Pi availability, enabling sustained Pi uptake under Pi-replete conditions and contributing to Pi homeostasis [16]. The allohexaploid bread wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) genome consists of three homoeologous subgenomes (A, B, and D) and therefore contains many homoeologous gene copies [18]. Consistent with this genomic complexity, wheat harbors an expanded phosphate transporter gene family comprising 35 identified members [19]. Among these, overexpression of TaPHT1;4 and TaPT2 significantly enhances rhizosphere Pi acquisition efficiency and promotes biomass accumulation [20,21]. In addition, TaPHT1.9-4B coordinates Pi uptake, long-distance Pi translocation, and growth under Pi starvation [22].

The essentiality of phosphorus for plant growth is undisputed. Accordingly, Pi uptake is tightly regulated to maintain optimal cellular Pi status while balancing colonization by beneficial microbes with constitutive defense readiness and inducible immune responses against fungal pathogens [23,24,25,26]. The acquisition of adequate Pi not only supports normal growth and development but also enhances pathogen defense capacity [23]. For example, foliar application of 50 mM K2HPO4 to rice increased grain yield by up to 32% while reducing blast disease (Magnaporthe oryzae) incidence by up to 42% [24]. However, plant defense responses under different Pi regimes are highly variable and depend on genetic background, as well as crosstalk between Pi availability and key defense hormone pathways, including salicylic acid (SA), jasmonic acid (JA), and ethylene signaling [25,26,27,28]. In rice, both excessive Pi fertilization and Pi overaccumulation repress the expression of defense-related genes, thereby compromising resistance to M. oryzae compared with sufficient- or low-Pi conditions [25]. In contrast, in A. thaliana, elevated Pi levels are associated with increased resistance to necrotrophic (Plectosphaerella cucumerina) and hemibiotrophic (Colletotrichum higginsianum) fungal pathogens [26,27]. Finally, phosphorus deficiency can suppress plant immunity, potentially favoring associations with plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) that enhance Pi acquisition efficiency and/or alleviate Pi stress [28]. Together, these findings highlight the importance of tightly regulated Pi uptake in maintaining cellular Pi homeostasis while balancing microbial interactions with effective defense against fungal pathogens.

Although the phosphate transport functions of PHT1 family members are well characterized, their direct involvement in immune signaling, especially within symbioses, remains poorly understood. We previously found that six TaPHT1 genes, including the newly identified TaPT3-2D, are constitutively upregulated in AM-colonized wheat roots regardless of external Pi status [19]. This Pi-independent expression suggests that TaPT3-2D regulation may be linked to symbiotic or defense signaling rather than nutrient sensing alone, raising the possibility that it integrates multiple biotic signals. To test this hypothesis, we conducted a functional analysis of TaPT3-2D, focusing on its subcellular localization, biochemical activity as a phosphate transporter, and physiological roles in plant-microbe interactions and Pi homeostasis. Compared with wild-type (WT) plants, TaPT3-2D-silenced wheat exhibited increased susceptibility to biotrophic, hemibiotrophic, and necrotrophic fungal pathogens; impaired AM symbiosis; and reduced Pi accumulation. Together, these results indicate that the mycorrhiza-inducible phosphate transporter TaPT3-2D regulates wheat immunity, AM symbiosis, and Pi uptake.

2. Results

2.1. TaPT3-2D Is an AM-Inducible Phosphate Transporter Gene

We previously performed a genome-wide characterization of the wheat PHT1 gene family and identified TaPT3-2D as a novel AM-inducible gene. Sequence analysis in Chinese Spring wheat revealed that TaPT3-2D maps to the chromosomal locus TraesCS2D02G045700. In addition, the two homologous genes TraesCS2B02G059100 and TraesCS2D02G045600 were identified and designated TaPT1-2B and TaPT2-2D, respectively [19]. Notably, the coding sequences (CDS) of these three homologous genes (TaPT1-2B, TaPT2-2D, and TaPT3-2D) share 80.6% nucleotide sequence identity (Figure S1).

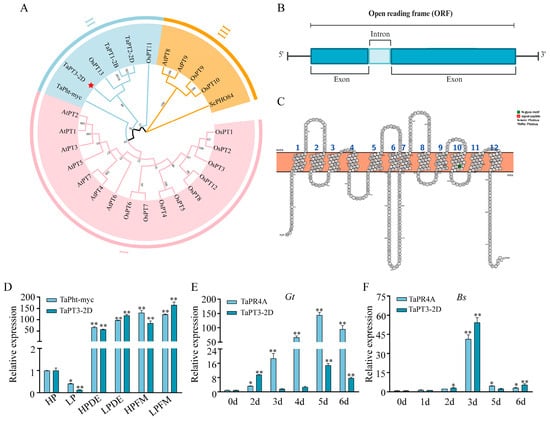

Phylogenetic analysis incorporating previously characterized rice PHTs (Table S1) demonstrated that TaPT1-2B, TaPT2-2D, TaPT3-2D, TaPht-myc (a mycorrhizal-specific PHT1 protein), and two rice PHT1 members (OsPT11 and OsPT13) cluster within the same phylogenetic group (Figure 1A). The AM-specific or AM-inducible transporters OsPT11 and OsPT13 are known to mediate the development of AM symbioses and Pi acquisition [29]. Notably, TaPT3-2D and OsPT13 represent a distinct subcluster.

Figure 1.

Characterization of TaPT3-2D. (A) A neighbor-joining (N-J) phylogenetic tree of phosphate transporters. Clade stability was evaluated by bootstrap resampling (n = 1000 replicates). (B) Gene structure of TaPT3-2D. (C) Transmembrane topology of TaPT31-7A predicted using Protter. (D) TaPT3-2D expression in arbuscular mycorrhiza-colonized wheat roots under different phosphate (Pi) regimes (42 days post inoculation). (E) TaPT3-2D expression in Gaeumannomyces tritici-infected roots. (F) TaPT3-2D expression in Bipolaris sorokiniana-infected roots. Asterisks indicate significant differences from the control according to one-way ANOVA followed by an independent-samples Dunnett’s post hoc test (* p ≤ 0.05; ** p ≤ 0.01).

TaPT1-2B, TaPT2-2D, and TaPT3-2D share high protein sequence similarity (76.89%) (Figure S2) and exhibit significantly greater homology with OsPT13 (72.64–81.94%) than with OsPT11 (60.38–62.83%) (Figure S3, Table S2). The TaPT3-2D gene contains one intron, and its 1566 bp CDS encodes a 521 aa protein (Figure 1B). The intron-exon boundary conforms to the canonical GT-AG splicing rule, as confirmed by reference annotation in WheatOmics using JBrowse. In silico analysis predicted that TaPT3-2D contains 12 transmembrane (TM) domains (Figure 1C).

2.2. Expression Profiling of TaPT3-2D and Its Homologous Genes

Transcript abundance of TaPT3-2D was markedly upregulated upon colonization by two AM fungi, with the strongest induction observed under low-Pi conditions in plants colonized by Diversispora epigaea and Funneliformis mosseae. This expression pattern supports the classification of TaPT3-2D as an AM-inducible phosphate transporter. Under low-Pi conditions, TaPT3-2D expression in D. epigaea- and F. mosseae-colonized plants significantly exceeded that of TaPht-myc, the first identified mycorrhizal-specific PHT1 gene in wheat (Figure 1D). In contrast, expression of TaPT1-2B and TaPT2-2D was significantly repressed by AM colonization, particularly in plants colonized by D. epigaea (Figure S4A).

To examine whether the expression of these three TaPHT genes is also affected by pathogen infection, wheat roots were inoculated with Bipolaris sorokiniana (Bs) and Gaeumannomyces tritici (Gt). As a well-established marker of pathogen challenge, TaPR4A exhibits diagnostic expression patterns during infection. Following Gt inoculation, TaPR4A transcription increased progressively and peaked at 5 days post inoculation (DPI) before declining modestly at 6 DPI. Expression of TaPT2-2D and TaPT3-2D was induced at 2 DPI, peaked at 5 DPI, and decreased by 6 DPI, whereas TaPT1-2B was significantly induced only at 2 DPI (Figure 1E and Figure S4B). Following Bs infection, TaPR4A and TaPT3-2D were significantly upregulated at 3 DPI and declined thereafter (Figure S4C). In contrast, TaPT1-2B and TaPT2-2D exhibited strong induction at 5 and 6 DPI. Given the observed involvement of TaPT3-2D in both AM symbiosis and pathogenic fungal infection, we next sought to elucidate its biological function.

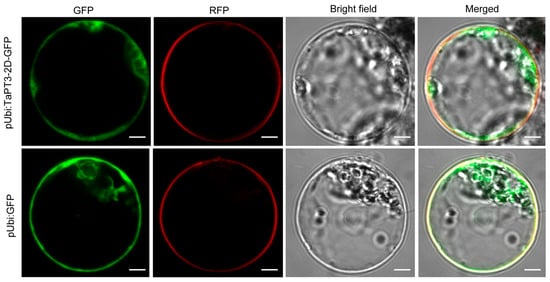

2.3. Subcellular Localization of TaPT3-2D

Given that phosphate transporters are typically localized to the plasma membrane, we assessed the subcellular localization of TaPT3-2D by transiently expressing a C-terminal GFP fusion under the control of the ubiquitin promoter in rice protoplasts. Consistent with the known properties of PHT1 proteins, TaPT3-2D-GFP fluorescence was observed exclusively at the plasma membrane, contrasting with the diffuse cytosolic and nuclear distribution of free GFP controls (Figure 2). These results therefore validate TaPT3-2D as a plasma membrane-localized phosphate transporter.

Figure 2.

Subcellular localization of TaPT3-2D. Confocal microscopy images showing plasma membrane localization of TaPT3-2D-GFP compared with the diffuse cytosolic and nuclear distribution of GFP in rice protoplasts at 16 h post inoculation. Scale bars = 5 µm.

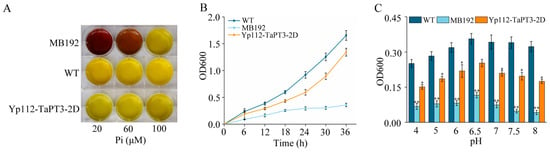

2.4. Complementation of TaPT3-2D in Yeast

The phosphate transporter activity of TaPT3-2D was evaluated using the yeast mutant MB192 transformed with p112A1NE-TaPT3-2D. Acid phosphatase activity staining revealed dose-dependent complementation at 20 and 60 μM Pi, suggesting that TaPT3-2D mediates Pi transport (Figure 3A). Growth kinetics in low-Pi YNB medium (60 µM) positioned TaPT3-2D-complemented MB192 cells between WT and mutant phenotypes, supporting partial functional recovery (Figure 3B). pH profiling identified pH 6.5 as optimal for TaPT3-2D-dependent Pi uptake, with complementation efficiency declining under both acidic and alkaline extremes (Figure 3C).

Figure 3.

Functional validation of TaPT3-2D in phosphate uptake-deficient yeast. (A) Acid phosphatase activity assay of MB192, TaPT3-2D-complemented (Yp112-TaPT3-2D), and wild-type yeast grown under phosphate (Pi) limitation (20–100 μM). (B) Growth phenotypes in medium containing 60 μM Pi. (C) pH-dependent growth at 60 μM Pi (24 h). Asterisks indicate significant differences from the control according to one-way ANOVA followed by an independent-samples Dunnett’s post hoc test (* p ≤ 0.05; ** p ≤ 0.01).

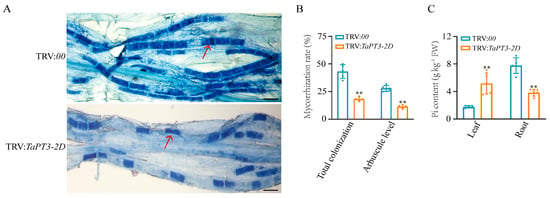

2.5. TaPT3-2D Is Required for AM Symbiosis and Pi Uptake

To characterize the role of TaPT3-2D in AM symbiosis, TaPT3-2D knockdown lines and control plants were inoculated with F. mosseae. Both the total colonization rate and arbuscule abundance were significantly lower in TaPT3-2D knockdown lines than in control plants. Mature arbuscules were observed in both control and virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) plants, with no obvious differences in arbuscule morphology observed (Figure 4A,B). To further examine the role of TaPT3-2D in Pi transport, Pi concentrations were measured in roots and shoots. TaPT3-2D-silenced plants exhibited significantly lower Pi concentrations in roots, accompanied by increased Pi concentrations in shoots, suggesting that TaPT3-2D contributes to root-to-shoot Pi transport (Figure 4C).

Figure 4.

Silencing of TaPT3-2D impairs mycorrhizal colonization and alters phosphate distribution. (A) Representative images of trypan blue-stained wheat roots colonized by Funneliformis mosseae in control (TRV:00, top) and TaPT3-2D-silenced (TRV:TaPT3-2D, bottom) plants. Arrows indicate arbuscules. Scale bars = 20 µm. (B) Total mycorrhizal colonization rate and arbuscule abundance in control and TaPT3-2D-silenced plants at six weeks post-inoculation. Both parameters were significantly reduced in TaPT3-2D-silenced lines. (C) Pi concentrations in leaves and roots of control and TaPT3-2D-silenced plants. Silencing of TaPT3-2D decreased root Pi concentrations while increasing leaf Pi concentrations. Asterisks indicate significant differences from the control according to one-way ANOVA followed by an independent-samples Dunnett’s post hoc test (** p ≤ 0.01).

2.6. Silencing of TaPT3-2D Increases Susceptibility to Fungal Pathogens

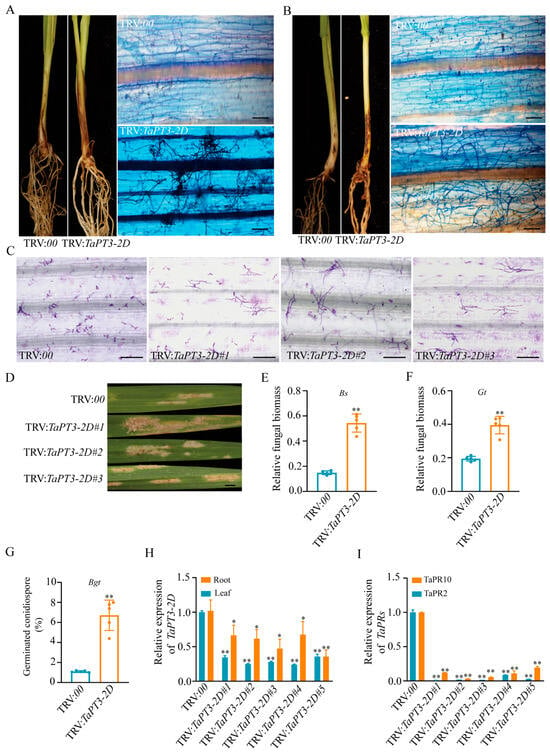

Given the strong induction of TaPT3-2D in response to pathogenic fungal infection, tobacco rattle virus (TRV)-based VIGS-mediated silencing of TaPT3-2D was performed to verify its role in wheat defense against pathogens. Following inoculation with the root pathogens Gt and Bs at 16 days after silencing, TaPT3-2D-VIGS lines exhibited accelerated disease progression. These plants showed significantly increased susceptibility to Gt at 21 DPI and to Bs at 40 DPI compared with control plants (Figure 5A,B). Consistently, both pathogens accumulated significantly more biomass in TaPT3-2D-silenced lines than in WT controls (Figure 5E,F).

Figure 5.

Silencing of TaPT3-2D enhances susceptibility to fungal pathogens and suppresses defense responses. (A) Disease symptoms and microscopic images of plants inoculated with Bipolaris sorokiniana (Bs) at 40 days post inoculation (DPI). (B) Disease symptoms and microscopic images of plants inoculated with Gaeumannomyces tritici (Gt) at 21 DPI. Microscopic (C) and macroscopic (D) images of leaves inoculated with Blumeria graminis f.sp. tritici (Bgt) at 60 h post inoculation (HPI). Relative fungal biomass of Bs (E) and Gt (F) in control and TaPT3-2D-silenced plants. (G) Bgt conidiospore germination rate on wheat leaves at 60 HPI. (H) Validation of TaPT3-2D silencing efficiency by qRT-PCR in roots and shoots. (I) Expression levels of defense-related genes TaPR2 and TaPR10 in control and silenced plants. Asterisks indicate significant differences from the control according to one-way ANOVA followed by an independent-samples Dunnett’s post hoc test (* p ≤ 0.05; ** p ≤ 0.01). Scale bars = 25 µm (A–C). Scale bars = 5 mm (D).

Because the obligate biotroph Blumeria graminis f.sp. tritici (Bgt) employs a life strategy distinct from that of Gt and Bs, we further examined resistance to Bgt in TaPT3-2D-silenced wheat. The fourth leaves of TaPT3-2D-silenced and control (TRV:00) plants were harvested at 16 DPI and inoculated with Bgt conidiospores. Colonization efficiency at 60 h post-infection (HPI) was significantly higher in silenced lines compared to vector controls (Figure 5C–G). Macroscopic examination revealed extensive mycelial colonization of TaPT3-2D-silenced leaves (Figure 5D), consistent with microscopic analyses. Collectively, these results demonstrate that suppression of TaPT3-2D compromises wheat resistance to Bgt infection.

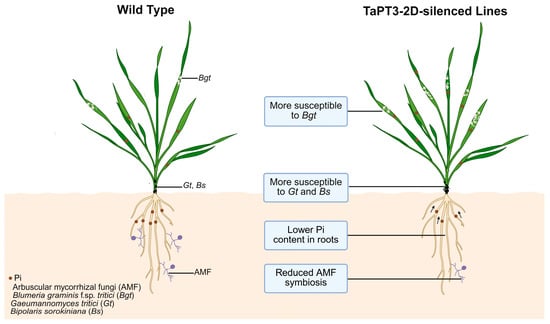

qRT-PCR validation confirmed efficient silencing of TaPT3-2D, with significantly reduced transcript abundance observed in both the roots and shoots of silenced plants compared to WT controls (Figure 5H). Concomitant with enhanced disease susceptibility, TaPT3-2D-silenced plants also exhibited marked downregulation of the defense-related genes TaPR2 and TaPR10 (Figure 5I). Together, these findings suggest that silencing of TaPT3-2D increases susceptibility to pathogens and impairs AM symbiosis and Pi uptake (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Proposed model of TaPT3-2D function in Pi uptake, arbuscular mycorrhizal (AM) symbiosis, and fungal pathogen resistance.

3. Discussion

3.1. TaPT3-2D Is a Novel Mycorrhizal-Induced PHT1 Similarly to OsPT13

Phylogenetic analysis revealed that TaPT3-2D and its two homologs form a monophyletic clade with three previously characterized AM-specific or AM-inducible phosphate transporters: OsPT13, OsPT11, and TaPht-myc (Figure 1A). Among these, TaPT3-2D exhibits the highest protein sequence similarity with OsPT13 (72.6%), followed by TaPht-myc (66.1%) and OsPT11 (62.3%) (Table S2). Notably, TaPT3-2D shares significantly higher sequence similarity with OsPT13 than with TaPht-myc, suggesting that TaPT3-2D is a functional ortholog of OsPT13 with a likely conserved role in mycorrhizal Pi transport.

Topological modeling further indicated that TaPT3-2D and OsPT13 both contain 12 TM domains, including a prominent hydrophilic loop linking TM6 and TM7, while both termini localize to the cytosol (Figure 1C) [29]. Previous studies have shown that OsPT13 is evolutionarily conserved exclusively in monocots, whereas OsPT11 exhibits cross-clade conservation across both monocots and dicots. Consistent with its mycorrhizal specificity, OsPT13 is upregulated 14-fold in Glomus intraradices-inoculated roots [30]. In comparison, TaPT3-2D expression increased 57- to 165-fold in wheat roots colonized by F. mosseae or D. epigaea across different Pi regimes. The exceptionally strong induction of TaPT3-2D (>100-fold) by these AM fungi highlights its central role in AM-mediated Pi uptake in wheat. In contrast, neither TaPT1-2B nor TaPT2-2D was significantly induced by AM colonization, indicating functional divergence among these homologous genes (Figure S4A). Guided by these findings, we next sought to further characterize the role of TaPT3-2D in Pi acquisition and AM symbiosis.

3.2. TaPT3-2D Is a High-Affinity Phosphate Transporter Integral to Pi Assimilation and AM Symbiosis

To verify the role of TaPT3-2D in Pi transport, we employed the high-affinity phosphate transporter-deficient yeast strain MB192 (Δpho84), a well-established system for functional validation of plant and fungal phosphate transporters [22,31,32,33]. Functional complementation with TaPT3-2D partially restored MB192 growth under low-Pi conditions (Figure 3), confirming its activity as a high-affinity phosphate transporter. The incomplete recovery of growth likely reflects limitations inherent to heterologous expression systems, including differences in transcriptional regulation, protein folding, and post-translational modification between plants and yeast [34].

VIGS provides a rapid and efficient approach for transient gene knockdown and functional analysis in plants, and TRV-based systems have been successfully applied in both monocots and dicots [35,36,37]. In TaPT3-2D-silenced wheat, Pi concentrations were significantly reduced in roots but increased in shoots, suggesting that TaPT3-2D contributes to root-to-shoot Pi transport. Several non-mutually exclusive mechanisms may explain this phenotype. First, silencing TaPT3-2D may induce a systemic Pi starvation response, leading to compensatory upregulation of other high-affinity Pi transporters (e.g., other TaPHT1 members) or genes involved in phloem loading. Such responses could prioritize Pi allocation to shoots to sustain growth despite impaired root Pi acquisition or symplastic transport. Second, reduced AM colonization (Figure 4A,B) likely decreases Pi sink strength in roots, resulting in a greater proportion of acquired Pi being translocated to shoots. Finally, TaPT3-2D may play a direct role in Pi loading or unloading within roots, thereby modulating root-to-shoot translocation efficiency. Further studies examining the expression of other phosphate transporters in the TaPT3-2D-silenced background will be required to distinguish among these possibilities.

In addition to altered Pi distribution, TaPT3-2D-silenced plants exhibited significantly reduced total AM colonization rates and arbuscule abundance. Although these results demonstrate that TaPT3-2D is required for normal AM symbiosis, the functional consequences of this morphological impairment on nutrient exchange remain to be determined. Future studies using radioisotope tracers (e.g., 33P) will be essential to directly quantify mycorrhiza-mediated Pi uptake in TaPT3-2D-deficient plants. In parallel, analyses of carbon allocation, including the expression of symbiosis-associated sugar transporters and carbon flux to the fungal partner, will provide a more comprehensive assessment of symbiotic efficiency regulated by TaPT3-2D.

Although TRV-mediated VIGS enabled efficient initial functional characterization of TaPT3-2D in wheat, definitive validation of its biological role will require stable genetic lines. Future studies employing CRISPR/Cas9-mediated knockout and overexpression approaches will be essential to exclude potential confounding effects associated with transient silencing and to facilitate long-term investigations of Pi homeostasis, AM symbiosis, and immune responses.

3.3. TaPT3-2D Is Involved in the Regulation of Wheat Innate Immunity

TaPT3-2D is a member of the PHT1 family, one of the most extensively characterized phosphate transporter families in wheat. As expected, the majority of research on PHT1 genes has focused on the roles of these genes in Pi uptake [20,21,22,38], whereas their functions in mycorrhizal symbiosis and plant immunity remain underexplored. In contrast, members of the PHT3 and PHT4 subfamilies have been more extensively examined for their roles in disease resistance [39,40,41]. For example, silencing of phosphate transporter AtPHT4;1 enhances susceptibility to the virulent pathogen Pseudomonas syringae in A. thaliana [40]. Independent studies have established AtPHT4;1 as a dual-function node coordinating pathogen defense and circadian regulation, and its expression is directly controlled by the core clock component CCA1 [42]. Similarly, silencing of the mitochondrial phosphate transporter TaMPT (a PHT3 family member) increases susceptibility to Fusarium head blight in wheat [39]. Consistent with these findings, we found that silencing TaPT3-2D increases wheat susceptibility to biotrophic, hemibiotrophic, and saprophytic fungi.

Notably, members of the same phosphate transporter family can exert contrasting effects on disease resistance. Although AtPHT4;6 and AtPHT4;1 both belong to the PHT4 family, silencing AtPHT4;6 significantly enhances resistance to virulent P. syringae [41], underscoring functional divergence within this gene family. Similarly, atpht1;4 mutants exhibit decreased susceptibility to the soil-borne bacterial pathogen Ralstonia solanacearum [43], while overexpression of the PHT1 family gene OsPT8 suppresses pattern-triggered immunity and attenuates resistance to rice blast (M. oryzae) and bacterial blight (Xanthomonas oryzae pv. oryzae) [44]. Collectively, although the effects of Pi transporters on disease susceptibility vary across pathosystems, these findings converge to support a functional link between PHT-mediated Pi uptake and plant immunity.

MicroRNAs (miRNAs) are also key regulators of Pi homeostasis, particularly miR399 and miR827. Overexpression of miR399 in A. thaliana and rice leads to Pi accumulation in leaves and increased susceptibility to M. oryzae [25,27]. Consistent with these reports, TaPT3-2D-silenced wheat exhibited elevated leaf Pi levels, enhanced pathogen susceptibility, and reduced AM symbiosis (Figure 4 and Figure 5). However, the mechanism by which plants integrate Pi status and microbial signals to coordinate defense and symbiosis remains elusive. Elucidating the molecular function of TaPT3-2D in Pi homeostasis and plant-microbe interactions will require protein–protein interaction analyses using yeast two-hybrid (Y2H), glutathione-S-transferase (GST) pull-down, bimolecular fluorescence complementation (BiFC), and firefly luciferase complementation imaging assays both in vivo and in vitro.

Although our data establish a link between TaPT3-2D, Pi homeostasis, AM symbiosis, and disease susceptibility, the underlying causal pathway remains to be resolved. The enhanced pathogen susceptibility observed in TaPT3-2D-silenced wheat may result from (i) direct disruption of Pi-dependent immune signaling, (ii) indirect effects caused by impaired AM symbiosis and the loss of symbiosis-associated defense benefits, or (iii) an independent, as-yet-unidentified role of TaPT3-2D in immune regulation. Future studies employing Pi supplementation assays in TaPT3-2D mutant backgrounds will be critical for distinguishing among these possibilities and determining whether altered immune responses primarily reflect changes in local Pi status or compromised symbiotic interactions.

Finally, although our results indicate that TaPT3-2D is required for full induction of defense-related genes such as TaPR2 and TaPR10, the upstream signaling pathways affected by TaPT3-2D silencing remain unknown. Future work should systematically characterize the dynamics of key defense hormones, including SA, JA, and ethylene, and evaluate the expression of core pattern-triggered immunity (PTI) components in this genetic background. Such analyses will be essential to determine whether TaPT3-2D modulates immunity through specific hormonal pathways or by broadly influencing early immune perception and signaling, thereby defining a more precise molecular connection between phosphate transport and immune regulation.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Materials and Fungal Inoculation

The Chinese winter wheat cultivar ‘Zhoumai 26’ was used for all experiments. Seedlings were transplanted into pots containing a sterilized mixture of soil and river sand at a 1:2 (v/v) ratio. To establish AM symbioses, autoclaved sand-based inocula containing 60 g of F. mosseae (Nicol. & Gerd, BGC XZ02A, isolated from the rhizosphere of Dangxiong, Tibet, China) or D. epigaea (BGC NM04B, formerly Glomus versiforme) were applied to 10 seedlings per treatment. Control plants received an equivalent amount of autoclaved inoculum. Both experimental and control plants were irrigated biweekly with half-strength Hoagland’s nutrient solution amended with either 5 μM (low-Pi) or 500 μM (high-Pi) KH2PO4. The experiment consisted of six treatment groups: high-Pi control (HP, 500 µM KH2PO4), low-Pi control (LP, 5 µM KH2PO4), high-Pi inoculated with D. epigaea (HPDE), low-Pi inoculated with D. epigaea (LPDE), high-Pi inoculated with F. mosseae (HPFM), and low-Pi inoculated with F. mosseae (LPFM). Tissue samples were collected at 42 DPI, immediately snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen, and stored at −80 °C for subsequent RNA extraction. The hemibiotrophic root rot pathogen Bs, provided by Henan Agricultural University, was cultured on potato dextrose agar (PDA) at 20 °C for 15 days. Ten-day-old seedlings were inoculated by applying Bs spore suspensions (4 × 104 spores mL−1) to stem bases according to a previously described protocol [45]. Root samples were collected at 0, 1, 2, 3, 5, and 6 DPI for RNA extraction. A separate set of seedlings was inoculated with the necrotrophic pathogen Gt (formerly Gaeumannomyces graminis var. tritici), provided by Henan Academy of Agricultural Science, according to a previously described protocol [46]. Root tissues were collected at 0, 2, 3, 4, 5, and 6 DPI for RNA extraction. Pathogen-inoculated plants were maintained in a growth chamber at 70% relative humidity and 22 °C during the light period (16 h) and 15 °C during the dark period (8 h). The biotrophic fungal pathogen Bgt was maintained on ‘Aikang 58’ wheat at 22 °C during the light period (16 h) and 15 °C during the dark period (8 h). The pathogenesis-related 4 family gene TaPR4A, which is strongly induced by multiple fungal pathogens, was utilized as a molecular marker for pathogenicity [47].

Experiments involving AM colonization and pathogen challenge were conducted independently, and samples from each treatment were processed and analyzed separately to avoid confounding effects. Each treatment consisted of 10 individual plants, and all experiments were performed with three biological replicates.

4.2. Subcellular Localization of TaPT3-2D in Rice Protoplasts

The full-length TaPT3-2D CDS was cloned using KAPA HiFi HotStart ReadyMix (Roche, Basel, Switzerland) and inserted downstream of the GFP gene in the pUbi-GFP-GW vector via Gateway recombination, generating the TaPT3-2D-GFP fusion vector under the transcriptional control of the ubiquitin promoter. The recombinant construct was verified by Sanger sequencing and subsequently introduced into Agrobacterium tumefaciens strain GV3101. The empty GFP vector was transformed in parallel as a control. Rice protoplasts were isolated from 10-day-old rice seedlings, and protoplast transformation was performed using a previously published protocol [48]. The TaPT3-2D-GFP fusion construct or GFP control was introduced into protoplasts, which were then incubated in the dark at 28 °C for 16 h. Subcellular localization of the expressed proteins was examined using a confocal laser scanning microscope (Stellaris 8, Leica, Wetzlar, Germany), with FM4-64 staining employed as a plasma membrane marker. The green channel was excited at 488 nm with emission collected between 500–547 nm; the red channel was excited at 587 nm via a white-light laser line with emission collected between 600–632 nm. Images were assembled for presentation in Adobe Illustrator 2022.

4.3. RNA Isolation and Quantitative Real-Time PCR (qRT-PCR)

Total RNA was isolated using TRIzol reagent (Invitrogen, Carlsbad, CA, USA) following the manufacturer’s protocol. Genomic DNA contamination was removed by treatment with RNase-free DNase I (Takara Bio Inc., Kusatsu, Japan). Total RNA was reverse transcribed to synthesize cDNA using the PrimeScript RT Perfect Real Time Kit (Takara Bio Inc., Kusatsu, Japan). qRT-PCR was performed on a CFX96 Touch Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA) using SYBR® Premix Ex Taq™ (Takara Bio Inc., Kusatsu, Japan). Relative gene expression levels were quantified using the 2−ΔΔCt method [49]. Each sample was analyzed with three independent biological replicates and three technical repeats.

4.4. Functional Analysis of TaPT3-2D in Yeast

To ascertain the biological function of TaPT3-2D, the Pi uptake-deficient yeast mutant MB192 was transfected with the p112A1NE expression vector harboring TaPT3-2D, following a previously described method [50]. Briefly, the TaPT3-2D CDS was subcloned into the p112A1NE vector to generate the recombinant TaPT3-2D-p112A1NE construct, which was subsequently introduced into MB192 yeast. Next, TaPT3-2D-p112A1NE-harboring MB192 cells, WT cells, and untransformed MB192 cells were cultured in yeast nitrogen base (YNB) liquid medium. Upon reaching the logarithmic growth phase, cells were harvested by centrifugation and washed twice with Pi-free YNB. Next, the three yeast strains were separately inoculated into YNB liquid medium supplemented with 20, 60, or 100 µM KH2PO4 and incubated at 30 °C for 10 h. Bromcresol purple was employed as a pH indicator, with a medium color transition from brown-red to yellow signaling acidification as a correlate of yeast growth. For quantitative growth analysis, MB192, WT, and Yp112-TaPT3-2D yeast cells were cultured in YNB liquid medium supplemented with 60 μM KH2PO4. Cell cultures were harvested at six time points (6, 12, 18, 24, 30, and 36 h) to quantify the optical density at 600 nm (OD600). To examine the impact of pH on Pi uptake, each yeast strain was cultured in YNB liquid medium supplemented with 60 μM KH2PO4 and adjusted to different pH values (4, 5, 6, 6.5, 7, 7.5, and 8). Following a 24 h incubation period, OD600 was measured to assess cell growth. Each assay was performed with three independent biological replicates per strain.

4.5. VIGS Analysis of TaPT3-2D in Wheat

To validate the role of TaPT3-2D in AM symbiosis and Pi transport, gene silencing was performed using a TRV-based VIGS system. A highly conserved 300 bp segment of TaPT3-2D was chosen as the target region and amplified from ‘Zhoumai 26’ wheat. Subsequently, the In-Fusion HD Cloning Plus system was employed to perform recombination cloning, enabling the insertion of the TaPT3-2D-carrying pYL156 plasmid into the TRV vector to generate the TRV:TaPT3-2D construct. The empty pYL156 vector was similarly introduced into the TRV genome to generate the negative control TRV:00. To generate gene-silenced seedlings, ‘Zhoumai 26’ seeds were subjected to a modified whole-plant VIGS protocol [51], with unsilenced controls harboring the TRV:00 construct. At 16 DPI, total RNA was isolated from the roots and leaves of both VIGS-silenced and unsilenced plants to analyze TaPT3-2D expression.

4.6. Functional Verification of TaPT3-2D-Silenced Plants in Response to Fungal Infection

To verify the role of TaPT3-2D in the wheat response to fungal infection, 30 VIGS-silenced wheat seedlings were individually inoculated with either biotrophic symbiotic AM fungi, the hemi-biotrophic pathogen Bs, the necrotrophic pathogen Gt, or the biotrophic pathogen Bgt. VIGS-silenced and TRV:00 control plants were inoculated with F. mosseae. At 42 DPI, freshly harvested AM-colonized roots were collected and stained with trypan blue following a previously described protocol [52]. The frequencies of total and AM colonization were quantified for 30 root samples by magnifying intersections under a BX61 fluorescence microscope equipped with a 20× objective lens. Microscopic images of pathogens were similarly visualized using the same microscope configuration.

Pathogen inoculation procedures were performed as described in Section 4.1. For pathogen biomass quantification, qPCR was conducted using primers specific to the 18S rRNA genes of Gt (accession number: FJ771002) and Bs (accession number: KM066949). TaActin gene (accession number: KC775780) was utilized as the internal reference gene. Primers used for qRT-PCR are provided in Table S3. Finally, the total Pi concentration was quantified in fresh leaf and root samples from TaPT3-2D-silenced and control plants [53].

4.7. Statistical Analysis

Statistical analyses were performed using one-way analysis of variance (ANOVA) to evaluate differences in relative gene expression among treatments and time points, as well as phenotypic variation among genotypes. When ANOVA indicated significant effects (p < 0.05), Duncan’s multiple range test was used for post hoc comparisons. Least significant difference (LSD) values were calculated at the 95% and 99% confidence levels to support the analysis. Significant differences are indicated in the figures, and corresponding LSD values are provided in the figure legends. All statistical analyses were conducted using SPSS version 23.

5. Conclusions

In this study, we functionally characterized TaPT3-2D, an AM-inducible phosphate transporter in wheat. Heterologous expression in Δpho84 mutant MB192 yeast rescued Pi uptake deficiency, suggesting that TaPT3-2D functions as a phosphate transporter. VIGS-mediated suppression of TaPT3-2D attenuated pathogen resistance, reduced AM symbiosis, and decreased the Pi content in roots. Collectively, these findings demonstrate that TaPT3-2D serves as a key integrator of phosphate nutrition, symbiotic signaling, and disease resistance in wheat.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/plants15010118/s1. Figure S1. Nucleotide sequences of TaPT1-2B, TaPT2-2D, and TaPT3-2D. The red box shows the silenced region in TaPT3-2D. Figure S2. Amino acid sequences of TaPT1-2B, TaPT2-2D, and TaPT3-2D. Figure S3. PHT1 protein sequence similarity matrix. Figure S4. Expression patterns of TaPT1-2B and TaPT2-2D. (A) TaPT1-2B and TaPT2-2D expression levels in wheat roots under low/high Pi conditions at 42 days post inoculation with two arbuscular mycorrhizal species. (B) TaPT1-2B and TaPT2-2D expression levels in Gaeumannomyces tritici (Gt)-infected roots. (C) TaPT1-2B and TaPT2-2D expression levels in Bipolaris sorokiniana (Bs)-infected roots. Table S1. Accession numbers of PHT proteins for constructing phylogenetic tree of TaPT3-2D. Table S2 Identities of PHT proteins used for constructing the phylogenetic tree of TaPT3-2D. Table S3 Primers used in this study.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.Z. and C.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.Z.; writing—review and editing, Y.Z., G.K., and C.L.; data curation, D.W., Y.M., and X.W.; resources, K.X., X.L., X.S., and H.C.; funding acquisition, Y.Z., D.W., and C.L. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32102487, 32372621, 32441052) and the Department of Science and Technology Planning Project of Henan Province (252102111164, 252102111149, 242102110299, 252102110299, 252102110322).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Material. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Gao, Z.Y.; Cao, H.B.; Huang, M.; Bao, M.; Qiu, W.H.; Liu, J.S. Winter wheat yield and soil critical phosphorus value response to yearly rainfall and P fertilization on the Loess Plateau of China. Field Crops Res. 2023, 296, 108921. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, R.; Ngangkham, U.; Abdullah, S.N.A. Editorial: Phosphorus starvation in plants. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1211439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Genre, A.; Lanfranco, L.; Perotto, S.; Bonfante, P. Unique and common traits in mycorrhizal symbioses. Nat. Rev. Microbiol. 2020, 18, 649–660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rich, M.K.; Vigneron, N.; Libourel, C.; Keller, J.; Xue, L.; Hajheidari, M.; Radhakrishnan, G.V.; Le Ru, A.; Diop, S.I.; Potente, G.; et al. Lipid exchanges drove the evolution of mutualism during plant terrestrialization. Science 2021, 372, 864–868. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Y.; Wang, W.; Xie, Q.; Liu, N.; Liu, L.; Wang, D.; Zhang, X.; Yang, C.; Chen, X.; Tang, D.; et al. Plants transfer lipids to sustain colonization by mutualistic mycorrhizal and parasitic fungi. Science 2017, 356, 1172–1175. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Oldroyd, G.E.D.; Leyser, O. A plant’s diet, surviving in a variable nutrient environment. Science 2020, 368, eaba0196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, J.; Wang, X.; Wang, E. Mycorrhizal symbiosis in plant growth and stress adaptation: From genes to ecosystems. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2023, 74, 569–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gu, M.; Chen, A.; Sun, S.; Xu, G. Complex regulation of plant phosphate transporters and the gap between molecular mechanisms and practical application: What is missing? Mol. Plant 2016, 9, 396–416. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kopriva, S.; Chu, C. Are we ready to improve phosphorus homeostasis in rice? J. Exp. Bot. 2018, 69, 3515–3522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mudge, S.R.; Rae, A.L.; Diatloff, E.; Smith, F.W. Expression analysis suggests novel roles for members of the Pht1 family of phosphate transporters in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2002, 31, 341–353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Młodzińska, E.; Zboińska, M. Phosphate uptake and allocation—A closer look at Arabidopsis thaliana L. and Oryza sativa L. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 1198. [Google Scholar]

- Shin, H.; Shin, H.S.; Dewbre, G.R.; Harrison, M.J. Phosphate transport in Arabidopsis: Pht1;1 and Pht1;4 play a major role in phosphate acquisition from both low- and high-phosphate environments. Plant J. 2004, 39, 629–642. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayadi, A.; David, P.; Arrighi, J.F.; Chiarenza, S.; Thibaud, M.C.; Nussaume, L.; Marin, E. Reducing the genetic redundancy of Arabidopsis PHOSPHATE TRANSPORTER1 transporters to study phosphate uptake and signaling. Plant Physiol. 2015, 167, 1511–1526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nagarajan, V.K.; Jain, A.; Poling, M.D.; Lewis, A.J.; Raghothama, K.G.; Smith, A.P. Arabidopsis Pht1;5 mobilizes phosphate between source and sink organs and influences the interaction between phosphate homeostasis and ethylene signaling. Plant Physiol. 2011, 156, 1149–1163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Remy, E.; Cabrito, T.R.; Batista, R.A.; Teixeira, M.C.; Sá-Correia, I.; Duque, P. The Pht1;9 and Pht1;8 transporters mediate inorganic phosphate acquisition by the Arabidopsis thaliana root during phosphorus starvation. New Phytol. 2012, 195, 356–371. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, X.; Wang, Y.; Piñeros, M.A.; Wang, Z.; Wang, W.; Li, C.; Wu, Z.; Kochian, L.V.; Wu, P. Phosphate transporters OsPHT1;9 and OsPHT1;10 are involved in phosphate uptake in rice. Plant Cell Environ. 2014, 37, 1159–1170. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ai, P.; Su, S.; Zhao, J.; Fan, X.; Xin, W.; Guo, Q.; Yu, L.; Shen, Q.; Wu, P.; Miller, A.J.; et al. Two rice phosphate transporters, OsPht1;2 and OsPht1;6, have different functions and kinetic properties in uptake and translocation. Plant J. 2009, 57, 798–809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Li, K.; Dai, X.; Qin, G.; Lu, D.; Gao, Z.; Li, X.; Song, B.; Bian, J.; Ren, D.; et al. A telomere-to-telomere genome assembly coupled with multi-omic data provides insights into the evolution of hexaploid bread wheat. Nat. Genet. 2025, 57, 1008–1020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Hu, L.; Yu, D.; Xu, K.; Zhang, J.; Li, X.; Wang, P.; Chen, G.; Liu, Z.; Peng, C.; et al. Integrative analysis of the wheat PHT1 gene family reveals a novel member involved in arbuscular mycorrhizal phosphate transport and immunity. Cells 2019, 8, 490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, C.; Guo, L.; Li, X.; Gu, J.; Zhao, M.; Duan, W.; Ma, C.; Lu, W.; Xiao, K. TaPT2, a high-affinity phosphate transporter gene in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.), is crucial in plant Pi uptake under phosphorus deprivation. Acta Physiol. Plant. 2014, 36, 1373–1384. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhao, X.; Zhang, L.; Lu, W.; Li, X.; Xiao, K. TaPht1;4, a high-affinity phosphate transporter gene in wheat (Triticum aestivum), plays an important role in plant phosphate acquisition under phosphorus deprivation. Funct. Plant Biol. 2013, 40, 329–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, P.; Li, G.; Li, G.; Yuan, S.; Wang, C.; Xie, Y.; Guo, T.; Kang, G.; Wang, D. TaPHT1;9-4B and its transcriptional regulator TaMYB4-7D contribute to phosphate uptake and plant growth in bread wheat. New Phytol. 2021, 231, 1968–1983. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Walters, D.R.; Bingham, I.J. Influence of nutrition on disease development caused by fungal pathogens: Implications for plant disease control. Ann. Appl. Biol. 2007, 151, 307–324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Manandhar, H.K.; Jørgensen, H.J.L.; Mathur, S.B.; Smedegaard-Petersen, V. Resistance to rice blast induced by ferric chloride, di-potassium hydrogen phosphate and salicylic acid. Crop Prot. 1998, 17, 323–329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Campos-Soriano, L.; Bundó, M.; Bach-Pages, M.; Chiang, S.F.; Chiou, T.J.; San Segundo, B. Phosphate excess increases susceptibility to pathogen infection in rice. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2020, 21, 555–570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Val-Torregrosa, B.; Bundó, M.; Mallavarapu, M.D.; Chiou, T.J.; Flors, V.; San Segundo, B. Loss-of-function of NITROGEN LIMITATION ADAPTATION confers disease resistance in Arabidopsis by modulating hormone signaling and camalexin content. Plant Sci. 2022, 323, 111374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Val-Torregrosa, B.; Bundó, M.; Martín-Cardoso, H.; Bach-Pages, M.; Chiou, T.J.; Flors, V.; Segundo, B.S. Phosphate-induced resistance to pathogen infection in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2022, 110, 452–469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, J.; Wu, D.; Li, X.; Wang, L.; Xu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, F.; Liu, H.; Xie, Q.; Dai, S.; et al. Plant immunity suppression via PHR1-RALF-FERONIA shapes the root microbiome to alleviate phosphate starvation. EMBO J. 2022, 41, e109102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Grønlund, M.; Jakobsen, I.; Grotemeyer, M.S.; Rentsch, D.; Miyao, A.; Hirochika, H.; Kumar, C.S.; Sundaresan, V.; Salamin, N.; et al. Nonredundant regulation of rice arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis by two members of the phosphate transporter1 gene family. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 4236–4251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paszkowski, U.; Kroken, S.; Roux, C.; Briggs, S.P. Rice phosphate transporters include an evolutionarily divergent gene specifically activated in arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2002, 99, 13324–13329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, X.; Huang, W.; Liu, F.; Tang, N.; Liu, Y.; Lin, H.; Zhao, B. Functional analysis of the novel mycorrhiza-specific phosphate transporter AsPT1 and PHT1 family from Astragalus sinicus during the arbuscular mycorrhizal symbiosis. New Phytol. 2013, 198, 836–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fan, X.; Che, X.; Lai, W.; Wang, S.; Hu, W.; Chen, H.; Zhao, B.; Tang, M.; Xie, X. The auxin-inducible phosphate transporter AsPT5 mediates phosphate transport and is indispensable for arbuscule formation in Chinese milk vetch at moderately high phosphate supply. Environ. Microbiol. 2020, 22, 2053–2079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zheng, R.; Wang, J.; Liu, M.; Duan, G.; Gao, X.; Bai, S.; Han, Y. Molecular cloning and functional analysis of two phosphate transporter genes from Rhizopogon luteolus and Leucocortinarius bulbiger, two ectomycorrhizal fungi of Pinus tabulaeformis. Mycorrhiza 2016, 26, 633–644. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nussaume, L.; Kanno, S.; Javot, H.; Marin, E.; Pochon, N.; Ayadi, A.; Nakanishi, T.M.; Thibaud, M.C. Phosphate import in plants: Focus on the PHT1 transporters. Front. Plant Sci. 2011, 2, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z.; Yang, X.; Ning, D.; Li, R. Characterization of 4-coumarate-CoA ligase (4CL) genes in wheat uncovers Ta4CL91’s role in drought and salt stress adaptation. Plants 2025, 14, 1301. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, K.; Lu, Z.; Yang, H.; Chen, S.; Li, C.; Cao, D.; Wang, H.; Hao, Q.; Chen, H.; Shan, Z. Efficient virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) method for discovery of resistance genes in soybean. Plants 2025, 14, 1547. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, M.; Wang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Peng, J.; Wu, G.; Rao, S.; Wu, J.; Zheng, H.; Chen, J.; Yan, F.; et al. Potato type I protease inhibitor mediates host defence against potato virus X infection by interacting with a viral RNA silencing suppressor. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2025, 26, e70073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Wang, J.; Dong, D.; Lou, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Y.; Yu, B.; Wang, P.; Kang, G. Comparative analysis of TaPHT1;9 function using CRISPR-edited mutants, ectopic transgenic plants and their wild types under soil conditions. Plant Soil 2025, 509, 249–260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malla, K.B.; Thapa, G.; Doohan, F.M. Mitochondrial phosphate transporter and methyltransferase genes contribute to Fusarium head blight Type II disease resistance and grain development in wheat. PLoS ONE 2021, 16, e0258726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.Y.; Shi, J.L.; Ng, G.; Battle, S.L.; Zhang, C.; Lu, H. Circadian clock-regulated phosphate transporter PHT4;1 plays an important role in Arabidopsis defense. Mol. Plant 2011, 4, 516–526. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hassler, S.; Lemke, L.; Jung, B.; Möhlmann, T.; Krüger, F.; Schumacher, K.; Espen, L.; Martinoia, E.; Neuhaus, H.E. Lack of the Golgi phosphate transporter PHT4;6 causes strong developmental defects, constitutively activated disease resistance mechanisms and altered intracellular phosphate compartmentation in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2012, 72, 732–744. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, G.; Zhang, C.; Battle, S.; Lu, H. The phosphate transporter PHT4;1 is a salicylic acid regulator likely controlled by the circadian clock protein CCA1. Front. Plant Sci. 2014, 5, 701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dindas, J.; DeFalco, T.A.; Yu, G.; Zhang, L.; David, P.; Bjornson, M.; Thibaud, M.C.; Custódio, V.; Castrillo, G.; Nussaume, L.; et al. Direct inhibition of phosphate transport by immune signaling in Arabidopsis. Curr. Biol. 2022, 32, 488–495.e5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dong, Z.; Li, W.; Liu, J.; Li, L.; Pan, S.; Liu, S.; Gao, J.; Liu, L.; Liu, X.; Wang, G.; et al. The rice phosphate transporter protein OsPT8 regulates disease resistance and plant growth. Sci. Rep. 2019, 9, 5408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burkhanova, G.F.; Yarullina, L.G.; Maksimov, I.V. The control of wheat defense responses during infection with Bipolaris sorokiniana by chitooligosaccharides. Russ. J. Plant Physl. 2007, 54, 104–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Yang, L.; Zhou, X.; Zhou, M.; Lu, Y.; Ma, L.; Ma, H.; Zhang, Z. Transgenic wheat expressing Thinopyrum intermedium MYB transcription factor TiMYB2R-1 shows enhanced resistance to the take-all disease. J. Exp. Bot. 2013, 64, 2243–2253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bertini, L.; Cascone, A.; Tucci, M.; D’Amore, R.; Di Berardino, I.; Buonocore, V.; Caporale, C.; Caruso, C. Molecular and functional analysis of new members of the wheat PR4 gene family. Biol. Chem. 2006, 387, 1101–1111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, B.; Liu, L.; Li, S.; Kuang, Y.; Wang, J.; Zhang, D.; Zhou, X.; Lin, H.; Zhou, H. Cas9-NG greatly expands the targeting scope of the genome-editing toolkit by recognizing NG and other atypical PAMs in rice. Mol. Plant 2019, 12, 1015–1026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Livak, K.J.; Schmittgen, T.D. Analysis of relative gene expression data using real-time quantitative PCR and the 2(-Delta Delta C(T)) Method. Methods 2001, 25, 402–408. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bun-Ya, M.; Nishimura, M.; Harashima, S.; Oshima, Y. The PHO84 gene of Saccharomyces cerevisiae encodes an inorganic phosphate transporter. Mol. Cell Biol. 1991, 11, 3229–3238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yu, D.; Zhang, Y.; Liu, K.; Xu, K.; Zhang, F.; Wang, J.; Tan, G.; Nie, X.; Ji, Q.; et al. Vacuum and Co-cultivation agroinfiltration of (germinated) seeds results in tobacco rattle virus (TRV) mediated whole-plant virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS) in wheat and maize. Front. Plant Sci. 2017, 8, 393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mc, G.T.; Miller, M.H.; Evans, D.G.; Fairchild, G.L.; Swan, J.A. A new method which gives an objective measure of colonization of roots by vesicular-arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi. New Phytol. 1990, 115, 495–501. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, A.; Hu, J.; Sun, S.; Xu, G. Conservation and divergence of both phosphate- and mycorrhiza-regulated physiological responses and expression patterns of phosphate transporters in solanaceous species. New Phytol. 2007, 173, 817–831. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.