Potato Yield and Quality, Soil Chemical Properties and Microbial Community as Affected by Different Potato Rotations in Southern Shanxi Province, China

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Results

2.1. Potato Tuber Yield and Quality

2.2. Soil Chemical Properties

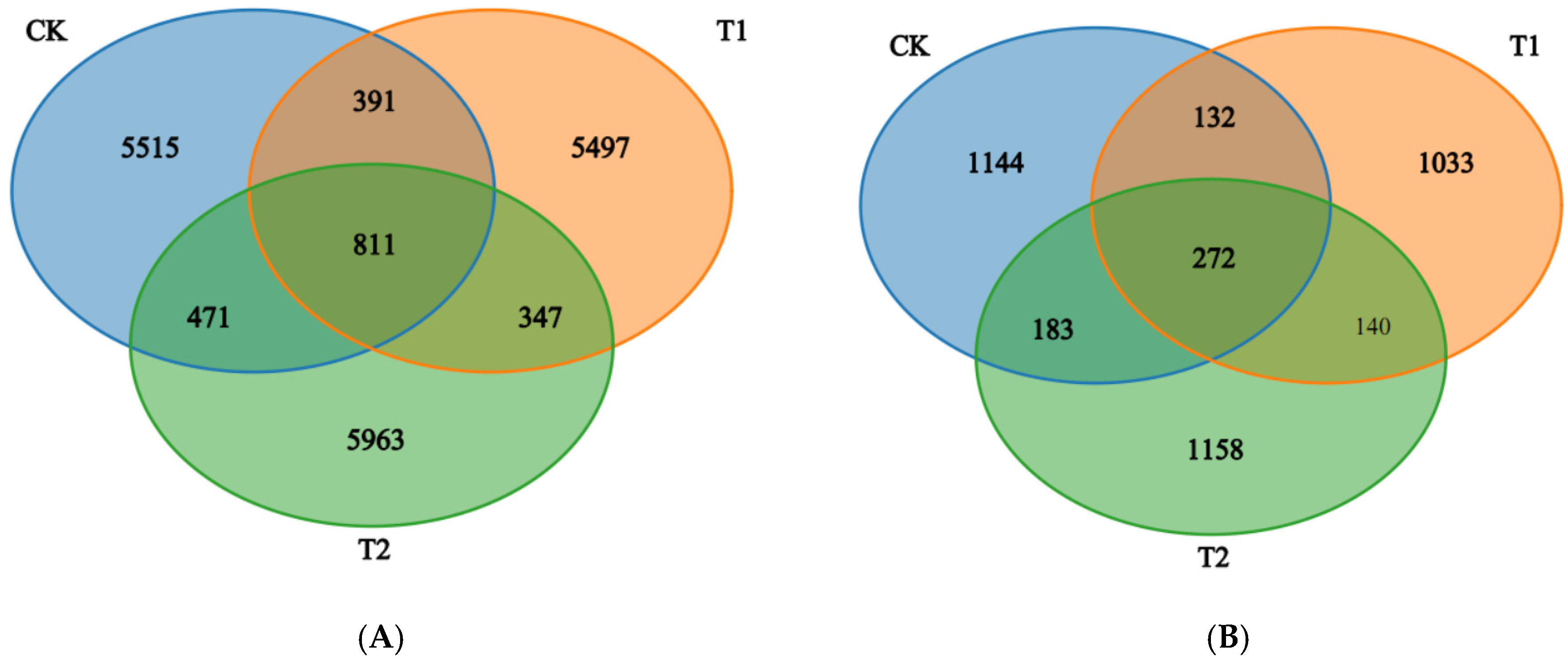

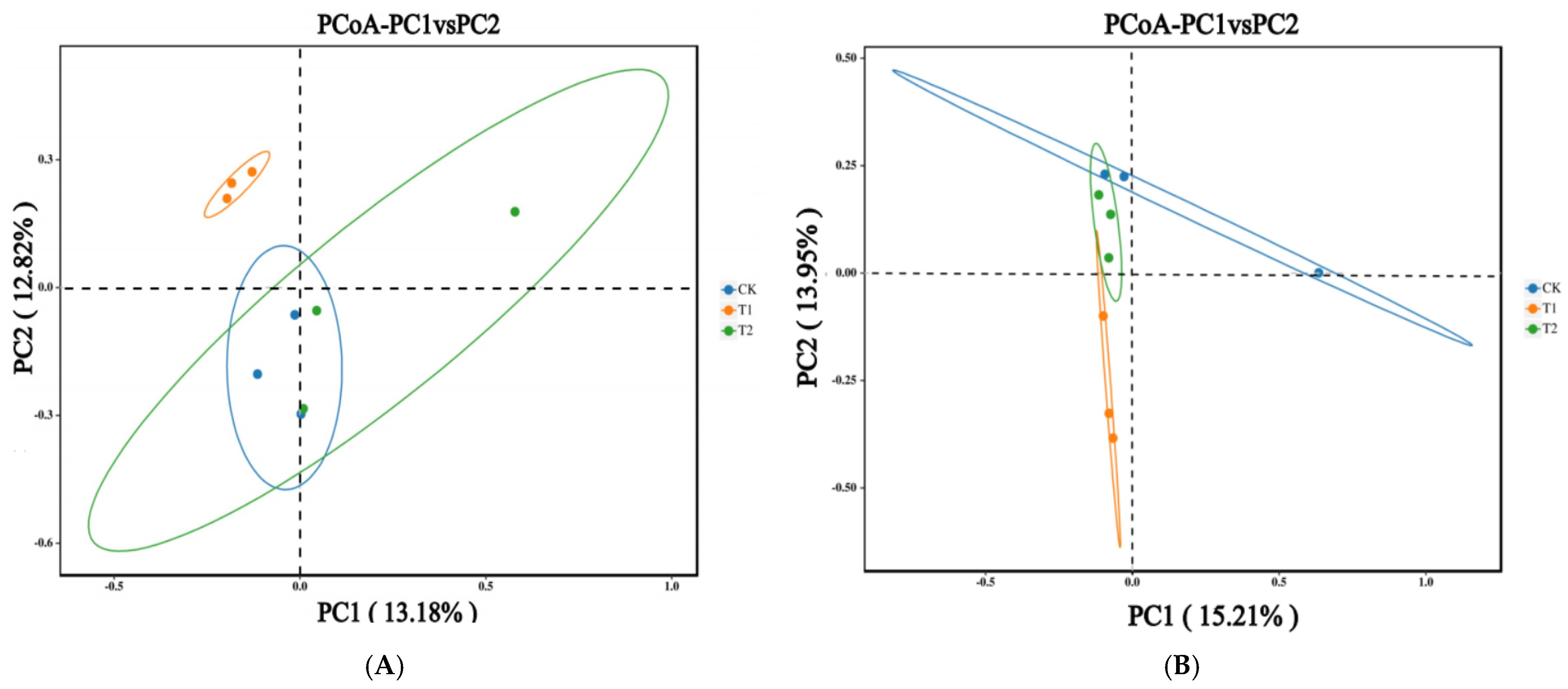

2.3. Bacterial and Fungal Community Diversity with Different Rotation Treatments

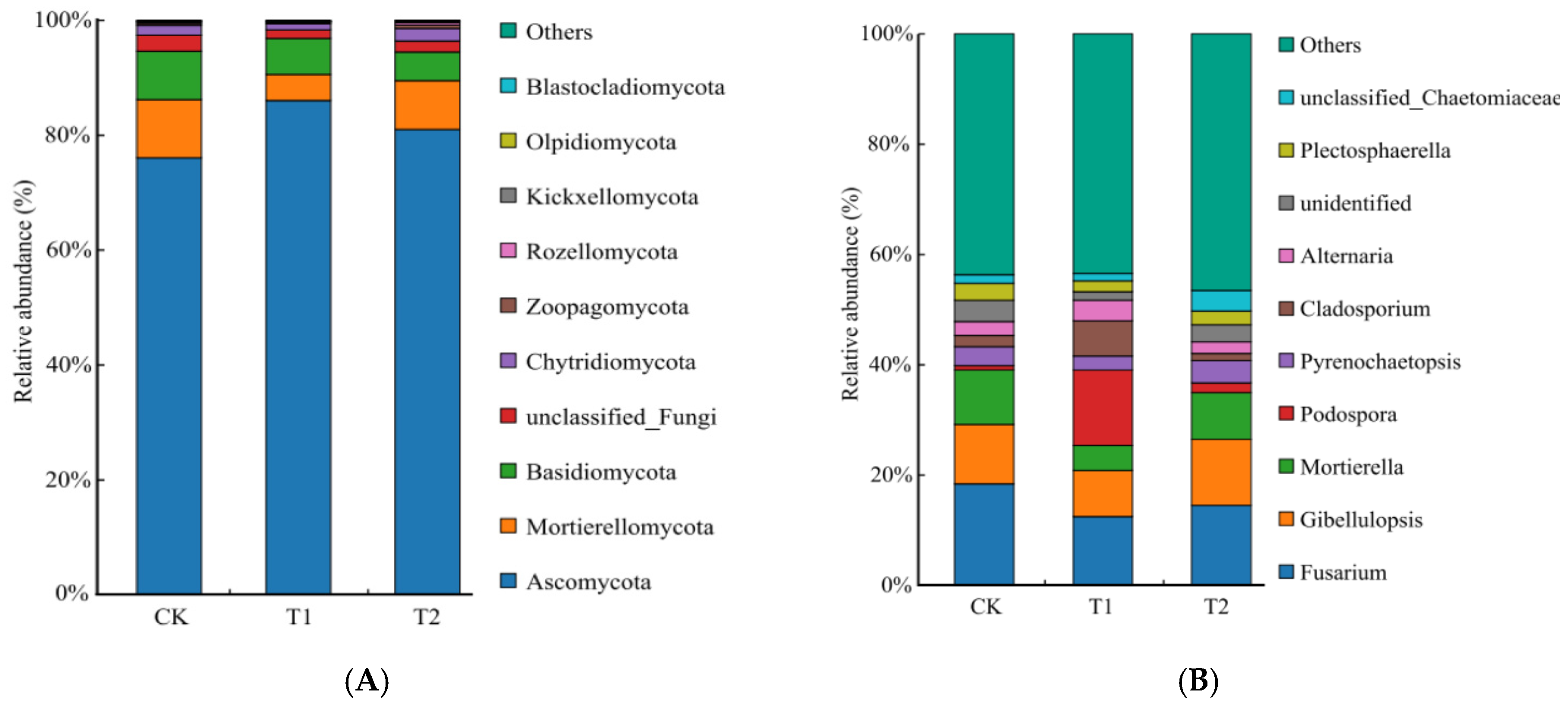

2.4. Bacterial and Fungal Composition and Structure with Different Rotation Treatments

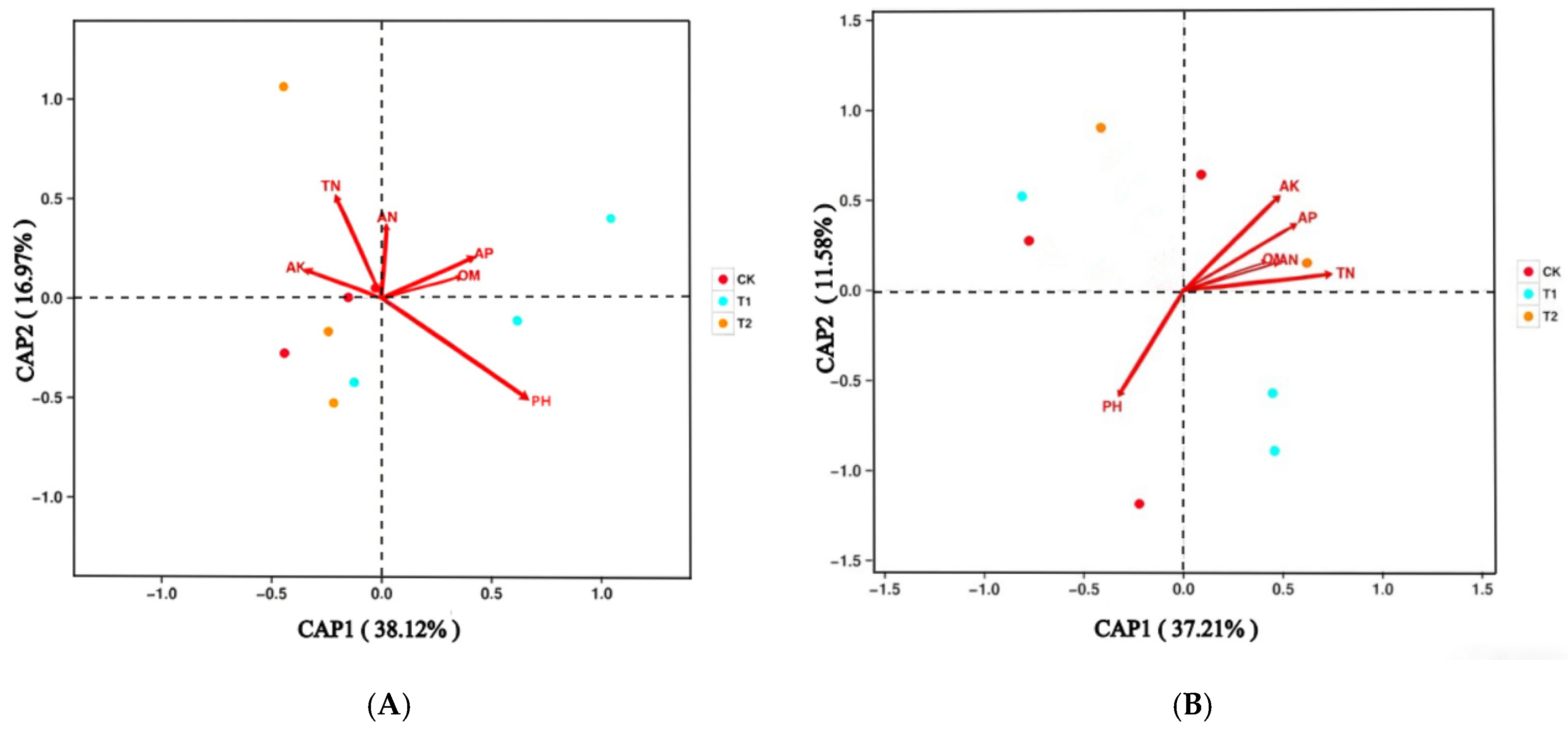

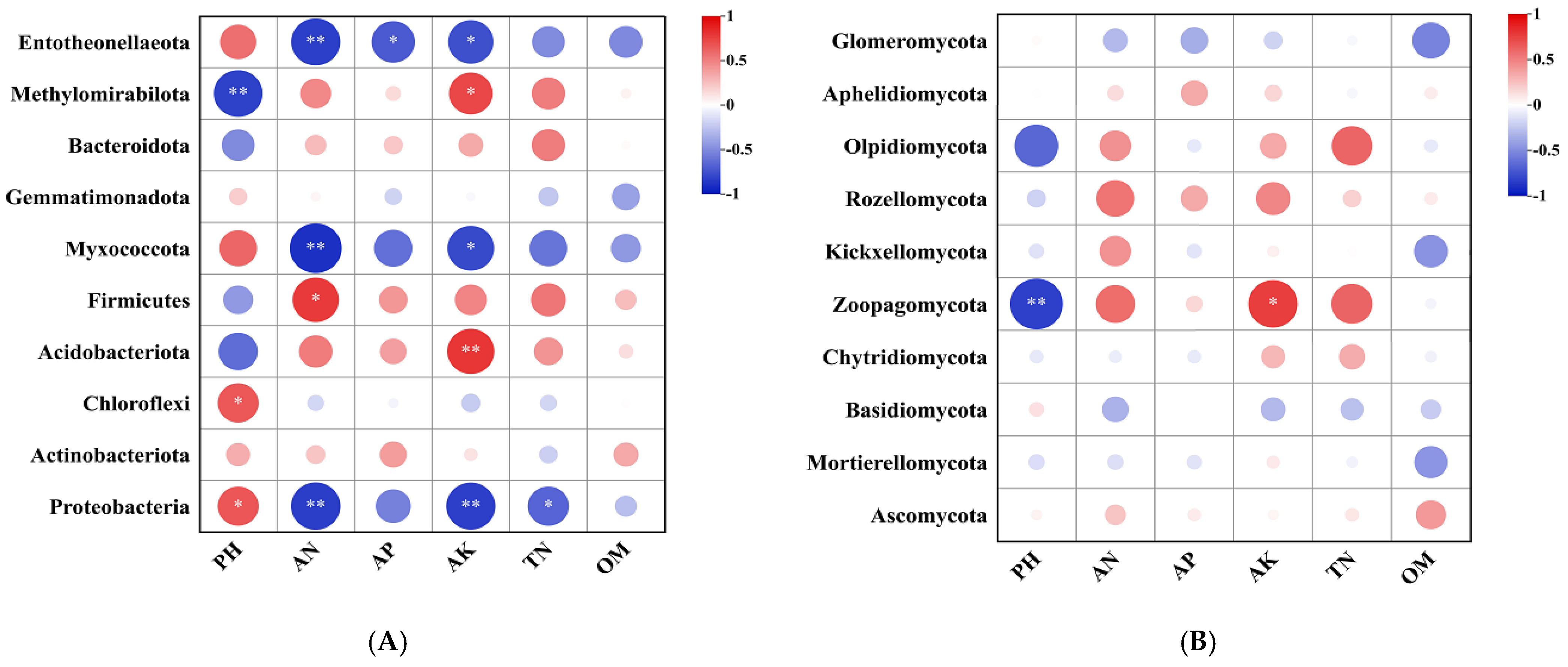

2.5. Soil Microbial Relationships with Soil Properties

3. Discussion

3.1. Effects of Rotation on Potato Tuber Yield and Quality

3.2. Effects of Potato Rotation on Soil Chemical Properties

3.3. Effects of Rotation on Soil Bacterial and Fungal Community

3.4. Relationships Between Microbes and Soil Chemical Parameters

4. Limitations of the Study

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Site Description

5.2. Experimental Design

5.3. Potato Yield and Nutrition Measurements

5.4. Soil Chemical Analysis

5.5. DNA Extraction and Illumina MiSeq Sequencing

5.6. Statistical Analysis

6. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

References

- FAO. 2025. Available online: https://www.fao.org/faostat/en/#data/QCL (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Stark, J.; Thornton, M.; Nolte, P. (Eds.) Potato Production Systems; Springer International Publishing: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2020; p. 635. ISBN 978-3-030-39156-0. [Google Scholar]

- Mijena, G.M.; Gedebo, A.; Beshir, H.M.; Haile, A. Ensuring food security of smallholder farmers through improving productivity and nutrition of potato. J. Agric. Food Res. 2022, 10, 100400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, E.Y.; Li, S.; Lantz, V.; Olale, E. Impacts of crop rotation and tillage practices on potato yield and farm revenue. Agron. J. 2019, 111, 1838–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, P.P.; Liu, X.; Qiu, H.Z.; Zhang, W.R.; Zhang, C.H.; Wang, D.; Zhang, J.L.; Shen, Q.R. Fungal population structure and its biological effect in rhizosphere soil of continuously cropped potato. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2022, 3, 3079–3086. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, X.; Abdellah, Y.A.Y.; Wang, G.; Wang, H.; Jiang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Chater, C.C.; Yang, Y.; Duan, Y.; Yu, F.; et al. Combatting environmental impacts and microbiological pollution risks in Potato cropping: Benefits of forage cultivation in a semi-arid region. Resour. Environ. Sustain. 2025, 20, 100216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, H.L.; Peng, Y.L.; Li, T.; Xie, Y.F.; Tang, L.M.; Wang, R.; Xiong, X.Y.; Wang, W.X.; Hu, X.X. Effects of potato continuous cropping on soil physicochemical and biological properties. J. Hunan Agric. Univ. Nat. Sci. 2019, 45, 611–616, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Hemkemeyer, M.; Sanja, A.S.; Clara, B.; Stefan, G.; Stefanie, H.; Rainer, G.J.; Li, R.; Peter, L.; Wu, X.; Florian, W. Potato yield and quality are linked to cover crop and soil microbiome, respectively. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2024, 60, 525–545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, R.P.; Honeycutt, C.W.; Grifn, T.S.; Olanya, O.M.; He, Z. Potato growth and yield characteristics under different cropping system management strategies in Northeastern U.S. Agronomy 2021, 11, 165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Bian, Q.; Jiang, Y.; Zhu, L.; Chen, Y.; Liang, Y.; Sun, B. Organic amendments drive shifts in microbial community structure and keystone taxa which increase C mineralization across aggregate size classes. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2021, 153, 108062. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Shi, M.F.; Zhang, R.Y.; Zhang, W.N.; Liu, Y.H.; Sun, D.X.; Wang, X.X.; Qin, S.H.; Kang, Y.C. Legume-potato rotation affects soil physicochemical properties, enzyme activity, and rhizosphere metabolism in continuous potato cropping. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2023, 10, 132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Blecharczyk, A.; Kowalczewski, P.Ł.; Sawinska, Z.; Rybacki, P.; Radzikowska-Kujawska, D. Impact of crop sequence and fertilization on potato yield in a long-term study. Plants 2023, 12, 495. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scholte, K. Causes of differences in growth pattern, yield and quality of potatoes (Solanum tuberosum L.) in short rotations on sandy soil as affected by crop rotation, cultivar and application of granular nematicides. Potato Res. 1990, 33, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wright, P.J.; Falloon, R.E.; Hedderley, D. A long-term vegetable crop rotation study to determine effects on soil microbial communities and soilborne diseases of potato and onion. NZJ Crop Hortic. Sci. 2017, 45, 29–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, R.P.; Honeycutt, C.W. Effects of different 3–year cropping systems on soil microbial communities and Rhizoctonia diseases of potato. Phytopathology 2006, 96, 68–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, H.Y.; Wang, W.Y.; He, P.; Ding, W.C.; Xu, X.P.; Tan, X.L.; Liu, X.W. Rotation reshapes sustainable potato production in dryland by reducing environmental footprints synergistically enhancing soil health. Resour. Environ. Sustain. 2025, 21, 100247. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.R.; Noronha, C.; Peters, R.D.; Kimpinski, J. Influence of conservation tillage and crop rotation on the resilience of an intensive long-term potato cropping system: Restoration of soil biological properties after the potato phase. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2009, 133, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, Q.; Wang, W.X.; Li, G.C.; Xiong, X.Y. Advances in the research on potato continuous cropping obstacles. Crops 2019, 6, 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Jiao, R.A.; Xu, X.F.; Yang, H.W.; Feng, Q.H.; Zhang, S.H.; Zhang, J.L.; Li, C.Z.; Li, J. Study on the effect and its mechanism of continuous cropping on potato growth and soil health. Agric. Res. Arid. Areas 2018, 36, 94–100, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar]

- Ma, K.; Zhang, L.; Du, Q.; Song, N.P. Effect of potato continuous cropping on soil microorganism community structure and function. J. Soil Water Conserv. 2010, 4, 229–233. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, J.; Gu, T.; Zhang, W.; Shen, Q.; Yin, S. Microbial community diversities and taxa abundances in soils along a seven-year gradient of potato monoculture using high throughput pyrosequencing approach. PLoS ONE 2014, 9, e86610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, X.M.; Zheng, Y.; Tang, L.; Long, G.Q. Crop rhizospheric microbial community structure and functional diversity as affected by maize and potato intercropping. J. Plant Nutr. 2017, 40, 2402–2412. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, R.P. Characterization of soil microbial communities under different potato cropping systems by microbial population dynamics, substrate utilization, and fatty acid profiles. Soil Biol. Biochem. 2003, 35, 1451–1466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, J.; Bian, C.; Duan, S.; Wang, W.; Li, G.; Jin, L. Effects of different rotation cropping systems on potato yield, rhizosphere microbial community and soil biochemical properties. Front. Plant Sci. 2022, 13, 999730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, X.L.; Guo, T.W.; Hu, X.Y.; Zhang, P.L.; Zeng, J.; Liu, X.W. Characteristics of microbial community in the rhizosphere soil of continuous potato cropping in arid regions of the loess plateau. Acta Agron. Sin. 2022, 48, 682–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ma, H.Y.; Xie, C.; Zheng, S.L.; Li, P.H.; Hafsa, N.C.; Gong, J.; Xiang, Z.Q.; Liu, J.J.; Qin, J.H. Potato tillage method is associated with soil microbial communities, soil chemical properties, and potato yield. J. Microbiol. 2022, 60, 156–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Nanak, K.; Zammurad, I.A.; Mukhtar, A.; Muhammad, F.A.; Ghulam, J. Response of Potato Yield, Soil Organic Matter, Microbial Properties, and Pesticide Residues to Different Cropping Systems and Nutrient Management in North Pakistan. Potato Res. 2025, 68, 2145–2165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Larkin, R.P.; Griffin, T.S.; Honeycutt, C.W. Rotation and cover crop effects on soilborne potato diseases, tuber yield, and soil microbial communities. Plant Dis. 2010, 94, 1491–1502. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peters, R.D.; Sturz, A.V.; Carter, M.R.; Sanderson, J.B. Influence of crop rotation and conservation tillage practices on the severity of soil-borne potato diseases in temperate humid agriculture. Can. J. Soil Sci. 2004, 84, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, S.; Yeboah, S.; Cao, L.; Zhang, J.; Shi, S.; Liu, Y. Breaking continuous potato cropping with legumes improves soil microbial communities, enzyme activities and tuber yield. PLoS ONE 2017, 12, e0175934. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, M.F.; Guo, A.X.; Kang, Y.C.; Yang, X.Y.; Zhang, W.N.; Liu, Y.H.; Zhang, R.Y.; Wang, Y.; Qin, S.H. Effects of plastic film mulching and legume rotation on soil nutrients and microbial communities in the Loess Plateau of China. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2023, 10, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Zhang, D.; Yang, Y.; Pan, Y.; Zhao, D.; Zhu, J.; Zhang, L.; Yang, Z. Dissecting the effect of continuous cropping of potato on soil bacterial communities as revealed by high-throughput sequencing. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0233356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Duan, Y.; Zhang, J.; Ciampitti, I.A.; Cui, J.; Qiu, S.; Xu, X.; Zhao, S.; He, P. Response of potato yield, soil chemical and microbial properties to different rotation sequences of green manure-potato cropping in North China. Soil Tillage Res. 2022, 217, 105273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.W.; Wang, X.X.; Lv, L.X.; Xiao, Y.; Dai, C.C. Effects of applying endophytic fungi on the soil biological characteristics and enzyme activities under continuously cropped peanut. Chin. J. Appl. Ecol. 2012, 23, 2693–2700. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J.Z.; Xiao, D.P.; Bai, H.Z. Yield and water use efficiency of potato under different irrigation levels in future climate change. Trans. Chin. Soc. Agric. Eng. 2020, 36, 103–112. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Tang, J.Z.; Xiao, D.P.; Wang, J.; Li, Y.; Bai, H.Z.; Pan, X.B. Optimizing planting dates and cultivars can enhance China’s potato yield under 1.5 °C and 2.0 °C global warming. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2022, 324, 109106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Korres, N.E.; Norsworthy, J.K.; Tehranchian, P.; Gitsopoulos, T.K.; Loka, D.A.; Oosterhuis, D.M.; Gealy, D.R.; Moss, S.R.; Burgos, N.R.; Miller, M.R.; et al. Cultivars to face climate change effects on crops and weeds: A review. Agron. Sustain. Dev. 2016, 36, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulatov, B.; Linderson, M.-L.; Hall, K.; Jönsson, A.M. Modeling climate change impact on potato crop phenology, and risk of frost damage and heat stress in northern Europe. Agric. For. Meteorol. 2015, 214–215, 281–292. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Shi, J.d.; Shakeyi, B.; Xi, K.P.; Tao, M.G.; Qiu, Y.R. High-yield cultivation technique of preicocious potato in southern Shanxi. Tillage Cultiv. 2023, 43, 137–139. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohr, R.M.; Volkmar, K.; Derksen, D.A.; Irvine, R.B.; Khakbazan, M.; McLaren, D.L.; Monreal, M.A.; Moulin, A.P.; Tomasiewicz, D.J. Effect of rotation on crop yield and quality in an irrigated potato system. Am. J. Potato Res. 2011, 88, 346–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, B.; Barik, A.K.; Saha, B.; Patel, N.; Fatima, A. Influence of crop diversification in potato-based cropping sequence on growth, productivity and economics of potato in red and lateritic soil of West Bengal. Ind. J. Ecol. 2024, 51, 197–200. [Google Scholar]

- Kouyaté, Z.; Franzluebbers, K.; Juo, A.S.; Hossner, L.R. Tillage, crop residue, legume rotation, and green manure effects on sorghum and millet yields in the semiarid tropics of Mali. Plant Soil 2000, 225, 141–151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.R.; Sanderson, J.B.; Peters, R.D. Long-term conservation tillage in potato rotations in Atlantic Canada: Potato productivity, tuber quality and nutrient content. Can. J. Plant Sci. 2009, 89, 273280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekeberg, E.; Riley, H.C.F. Effects of mouldboard ploughing and direct planting on yield and nutrient uptake of potatoes in Norway. Soil Tillage Res. 1996, 39, 131142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jahanzada, E.; Barker, A.V.; Hashemi, M.; Sadeghpour, A.; Eatona, T.; Park, Y. Improving yield and mineral nutrient concentration of potato tubers through cover cropping. Field Crops Res. 2017, 212, 45–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srećkov, Z.; Vujasinović, V.; Mišković, A.; Mrkonjić, Z.; Bojović, M.; Olivera, N.; Vasić, V. Effect of different covering treatments on chemical composition of early potato tubers. Potato Res. 2025, 68, 969–990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azimi, M.A.; Jiang, Y.F.; Meng, F.R.; Liang, K. Yield responses of four common potato cultivars to an industry standard and alternative rotation in Atlantic Canada. Am. J. Potato Res. 2022, 99, 206–216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Sun, H.N.; Zhang, M.; Mu, T.H.; Khan, N.M.; Ahmad, S.; Validov, S.Z. Fungal communities, nutritional, physiological and sensory characteristics of sweet potato under three Chinese representative storages. Postharvest Biol. Technol. 2023, 201, 112366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ierna, A.; Mauromicale, G. How irrigation water saving strategy can afect tuber growth and nutritional composition of potato. Sci. Hortic. 2022, 299, 111034. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Galdón, B.R.; Rodríguez, L.H.; Mesa, D.R.; León, H.L.; Pérez, N.L.; Rodríguez, E.M.R.; Romero, C.D. Differentiation of potato cultivars experimentally cultivated based on their chemical composition and by applying linear discriminant analysis. Food Chem. 2012, 133, 1241–1248. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, G.H.; Liu, X.J.; Zhang, Y.; Shen, J.L.; Han, W.X.; Zhang, W.F.; Christie, P.; Goulding, K.W.T.; Vitousek, P.M.; Zhang, F.S. Significant acidification in major Chinese croplands. Science 2010, 327, 1008–1010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, R.; Babu, S.; Avasthe, R.; Das, A.; Pandey, A.; Gudade, B.; Devadas, R.; Saha, S.; Rathore, S. Integrated organic nutrient management: A sustainable approach for cleaner maize (Zea mays L.) production in the Indian Himalayas. Org. Agric. 2024, 14, 373–393. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grandy, A.S.; Porter, G.A.; Erich, M.S. Organic amendment and rotation crop effects on the recovery of soil organic matter and aggregation in potato cropping systems. Soil Sci. Soc. Am. J. 2002, 66, 1311–1319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carter, M.R.; Kunelius, H.T.; Sanderson, J.B.; Kimpinski, J.; Platt, H.W.; Bolinder, M.A. Productivity parameters and soil health dynamics under long-term 2-year potato rotations in Atlantic Canada. Soil Tillage Res. 2003, 72, 153–168. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Griffin, T.S.; Porter, G.A. Altering soil carbon and nitrogen stocks in intensively tilled two-year rotations. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2004, 39, 366–374. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ananda, M.; Vaiahnav, S.; Naide, P.R.; Aruna, N.V. Long term benefits of legume based cropping systems on soil health and productivity. An overview. Int. J. Environ. Clim. Change 2022, 12, 299–315. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- İnceoğlu, Ö.; Salles, J.F.; van Elsas, J.D. Soil and cultivar type shape the bacterial community in the potato rhizosphere. Microb. Ecol. 2012, 63, 460–470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jing, J.; Cong, W.F.; Bezemer, T.M. Legacies at work: Plant-soil-microbiome interactions underpinnig agricultural sustainability. Trends Plant Sci. 2022, 27, 781–792. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghosh, A.; Bhattacharyya, R.; Dwivedi, B.S.; Meena, M.C.; Agarwal, B.K.; Mahapatra, P.; Shahi, D.K.; Salwani, R.; Agnihorti, R. Temperature sensitivity of soil organic carbon decomposition as affected by long-term fertilization under a soybean based cropping system in a sub-tropical Alfsol. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2016, 233, 202–213. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clocchiatti, A.; Hannula, S.E.; van den Berg, M.; Korthals, G.; de Boer, W. The hidden potential of saprotrophic fungi in arable soil: Patterns of short-term stimulation by organic amendments. Appl. Soil Ecol. 2020, 147, 103434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zeng, Y.H.; Nupur, N.C.; Wu, N.; Madsen, A.M.; Chen, X.H.; Gardiner, A.T.; Koblizek, M. Gemmatimonas groenlandica sp. nov. is an aerobic anoxygenic phototroph in the phylum Gemmatimonadetes. Front. Microbiol. 2021, 11, 606612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Delgado-Baquerizo, M.; Trivedi, P.; Trivedi, C.; Eldridge, D.J.; Reich, P.B.; Jeffries, T.C.; Singh, B.K. Microbial richness and composition independently drive soil multifunctionality. Funct. Ecol. 2017, 31, 2330–2343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Khafipour, E.; Krause, D.O.; Entz, M.H.; de Kievit, T.R.; Fernando, W.G.D. Pyrosequencing reveals the influence of organic and conventional farming systems on bacterial communities. PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e51897. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mendes, R.; Kruijt, M.; de Bruijn, I.; Dekkers, E.; Van Der Voort, M.; Schneider, J.H.; Piceno, Y.M.; DeSantis, T.Z.; Andersen, G.L.; Bakker, P.A.; et al. Deciphering the rhizosphere microbiome for disease-suppressive bacteria. Science 2011, 332, 1097–1100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Xiong, W.; Li, Z.; Liu, H.; Xue, C.; Zhang, R.; Wu, H.; Li, R.; Shen, Q. The effect of long-term continuous cropping of black pepper on soil bacterial communities as determined by 454 pyrosequencing. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0136946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, R.; Wang, H.H.; Zhao, Y.Y.; Cheng, Y.Y.; Wu, J.; Shi, H.Z. Effects of organic materials with different carbon sources on soil carbon and nitrogen and bacterial communities in tobacco planting soil. J. Henan Agric. Sci. 2022, 51, 84–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- de Boer, W.; Folman, L.B.; Summerbell, R.C.; Boddy, L. Living in a fungal world: Impact of fungi on soil bacterial niche development. FEMSMicrobiol. Rev. 2005, 29, 795–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Liu, L.; Luo, Y.; Awasthi, M.K.; Yang, J.; Duan, Y.; Li, H.; Zhao, Z. Mulching practices alter the bacterial-fungal community and network in favor of soil quality in a semiarid orchard system. Sci. Total Environ. 2020, 725, 138527. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Larkin, R.P.; Griffn, T.S. Control of soilborne potato diseases using Brassica green manures. Crop Prot. 2007, 26, 1067 1077. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cannon, P.F.; Buddie, A.G.; Bridge, P.D.; de Neergaard, E.; Lubeck, M.; Askar, M.M. Lectera, a new genus of the Plectosphaerellaceae for the legume pathogen Volutella colletotrichoides. Mycokeys 2012, 3, 23–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.N.; Sayed, R.A.S.; Sun, S.H.; Bai, Y.J.; Lv, D.Q.; Jiang, L.L.; Min, F.X.; Gao, Y.F.; Ma, J.; Wang, X.D.; et al. Composition and distribution of Alternaria species causing foliar diseases on potato in Heilongjiang Province of China. Mol. Plant Breed. 2017, 15, 1077–1083, (In Chinese with English abstract). [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.M.; Zhang, D.; Zhang, J.Z.; Zhou, Z.J.; Pan, Y.; Yang, Z.H.; Zhu, J.H.; Liu, Y.H.; Zhang, L.F. Crop rotations increased soil ecosystem multifunctionality by improving keystone taxa and soil properties in potatoes. Front. Microbiol. 2023, 14, 1034761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.S.; Wu, X.H.; Li, G.; Qin, P. Interactions between arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi and phosphate-solubilizing fungus (Mortierella sp.) and their effects on Kostelelzkya virginica growth and enzyme activities of rhizosphere and bulk soils at different salinities. Biol. Fertil. Soils 2011, 47, 543–554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicosia, M.G.L.; Mosca, S.; Mercurio, R.; Schena, L. Dieback of Pinus nigra seedlings caused by a strain of Trichoderma viride. Plant Dis. 2015, 99, 44–49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, S.C.; Qiu, S.J.; Cao, C.Y.; Zheng, C.L.; Zhou, W.; He, P. Responses of soil properties, microbial community and crop yields to various rates of nitrogen fertilization in a wheat–maize cropping system in north-central China. Agric. Ecosyst. Environ. 2014, 194, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lu, R.K. Soil Agricultural Chemical Analysis Method; China Agricultural Science and Technology Press: Beijing, China, 2000. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

| Treatments | Number of Tubers/Plant | Tuber Weight (kg/Plant) | Commodity Rate (%) | Large Tuber Rate (%) | Medium Potato Rate (%) | Small Potato Rate (%) | Tuber Yield (Tons/Hectare) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2 | 10 ± 0.15 a | 1.10 ± 0.03 a | 82.00 ± 1.42 b | 28.00 ± 0.75 a | 54.00 ± 0.67 b | 18.00 ± 1.42 b | 53.52 ± 0.10 a |

| T1 | 9 ± 0.40 a | 1.00 ± 0.08 a | 88.89 ± 1.24 a | 26.67 ± 0.56 b | 62.22 ± 0.75 a | 11.11 ± 1.24 c | 52.50 ± 0.27 a |

| CK | 7 ± 0.20 b | 0.87 ± 0.02 b | 74.28 ± 3.40 c | 22.85 ± 2.10 c | 51.43 ± 1.30 c | 25.72 ± 3.40 a | 44.35 ± 0.07 b |

| Treatments | TN (g/kg) | TP (g/kg) | TK (g/kg) | Crude Protein (%) | Vitamin C (mg/g) | Starch (mg/g) | Reducing Sugar (mg/g) | Dry Matter (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2 | 17.14 ± 0.57 a | 1.47 ± 0.17 a | 26.40 ± 1.45 a | 10.71 ± 0.57 a | 0.18 ± 0.01 a | 150.1 ± 2.92 a | 1.61 ± 0.01 b | 18.84 ± 1.18 a |

| T1 | 14.07 ± 1.19 b | 1.25 ± 0.12 ab | 21.41 ± 2.32 b | 8.79 ± 1.19 b | 0.16 ± 0.01 ab | 146.0 ± 6.65 a | 1.64 ± 0.01 ab | 17.45 ± 0.14 ab |

| CK | 13.37 ± 1.01 b | 1.09 ± 0.08 b | 17.32 ± 0.63 c | 8.36 ± 1.01 b | 0.15 ± 0.01 b | 113.3 ± 3.35 b | 1.66 ± 0.02 a | 16.69 ± 0.40 b |

| Treatments | pH | AN | AP | AK | TN | OM |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| mg/kg | mg/kg | mg/kg | g/kg | g/kg | ||

| T2 | 7.74 ± 0.02 b | 22.87 ± 0.73 a | 28.41 ± 0.52 a | 335.9 ± 5.53 a | 1.08 ± 0.01 a | 37.94 ± 0.26 a |

| T1 | 7.86 ± 0.01 a | 21.12 ± 1.23 a | 27.93 ± 1.54 ab | 302.2 ± 2.52 b | 0.97± 0.01 b | 35.34 ± 0.38 a |

| CK | 7.92 ± 0.02 a | 20.50 ± 0.56 a | 25.28 ± 1.16 b | 285.5 ± 3.92 b | 0.93± 0.01 b | 31.85 ± 0.15 b |

| Treatments | Chao1 | ACE | Shannon | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| T2 | 2874.22 ± 139.69 a | 2880.81 ± 138.70 a | 10.27 ± 0.04 a | |

| Bacteria | T1 | 2706.17 ± 108.47 a | 2712.43 ± 108.42 a | 10.18 ± 0.04 a |

| CK | 2781.01 ± 140.72 a | 2788.60 ± 140.26 a | 10.22 ± 0.04 a | |

| T2 | 734.56 ± 46.61 a | 741.80 ± 45.09 a | 6.65 ± 0.06 a | |

| Fungi | T1 | 665.59 ± 71.40 b | 673.53 ± 70.41 b | 6.19 ± 0.38 a |

| CK | 709.31 ± 21.86 a | 715.47 ± 20.30 a | 6.35 ± 0.20 a |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Liu, J.; Shi, J.; Li, Y. Potato Yield and Quality, Soil Chemical Properties and Microbial Community as Affected by Different Potato Rotations in Southern Shanxi Province, China. Plants 2026, 15, 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010117

Liu J, Shi J, Li Y. Potato Yield and Quality, Soil Chemical Properties and Microbial Community as Affected by Different Potato Rotations in Southern Shanxi Province, China. Plants. 2026; 15(1):117. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010117

Chicago/Turabian StyleLiu, Jing, Jundong Shi, and Yongshan Li. 2026. "Potato Yield and Quality, Soil Chemical Properties and Microbial Community as Affected by Different Potato Rotations in Southern Shanxi Province, China" Plants 15, no. 1: 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010117

APA StyleLiu, J., Shi, J., & Li, Y. (2026). Potato Yield and Quality, Soil Chemical Properties and Microbial Community as Affected by Different Potato Rotations in Southern Shanxi Province, China. Plants, 15(1), 117. https://doi.org/10.3390/plants15010117