Abstract

Despite the ethnobotanical significance of Chilean Colliguaja species, research on their biological activities and phytochemical composition remains limited. Among these species, Colliguaja odorifera Molina (Euphorbiaceae), traditionally used in folk medicine to alleviate toothaches, stands out for its potential for medicinal applications. This study aims to investigate the anti-inflammatory activity of the C. odorifera leaf extracts and their secondary metabolites isolated from the most active extract. A hydroalcoholic extract of C. odorifera leaves was prepared, and subsequently ethyl acetate (EA-E), n-butanol (B-E), and water (W-E) extracts were obtained by liquid–liquid partition. The extracts were first evaluated for their ability to inhibit lipoxygenase, and the most active extract was subsequently tested for hyaluronidase (HA) and secretory phospholipase A2 (sPLA2). The most active extract was EA-E, with IC50 values of 11.75, 31.09, and 6.60 µg/mL for anti-LOX activity, hyaluronidase, and sPLA2, respectively. This extract was analyzed by chromatography coupled to mass spectrometry and 1H and 13C NMR spectroscopy, allowing the identification, for the first time, of shikimic acid, gallic acid, methyl gallate, ethyl gallate, and a putative galloyl-luteolin. These results suggest that C. odorifera is a promising candidate for the development of natural alternatives to nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drugs.

1. Introduction

The Euphorbiaceae family, one of the largest families of flowering plants, is represented by approximately 7500 species distributed across 300 genera and 50 tribes [1]. In Chile, this family is represented by 45 taxa, including 35 endemic and native species distributed across seven genera: Adenopeltis, Argythamnia, Avellanita, Colliguaja, Croton, Chiropetalum, Dysopsis, and Euphorbia [2,3]. Since ancient times, the Euphorbiaceae family has been known for its diverse medicinal properties. Over 214 species with medicinal properties have been identified in Chile, and there is a rich history of using some Chilean species from the Euphorbiaceae family in traditional medicine, making them a vital part of Chilean cultural heritage [2,3]. Notwithstanding the above, the species of Colliguaja, such as Colliguaja dombeyana A. Juss., Colliguaja integerrima Gillies & Hook, Colliguaja salicifolia Gillies & Hook, and Colliguaja odorifera Molina, which are cataloged as endemic [4], have not been as extensively researched or documented in this regard. The Mapuche ethnic group used to call these Colliguaja species “Collihuayu,”. C. odorifera is a woody monoecious shrub distributed from 23°30′ to 35°32′ S, covering different ecological environments. The staminate (male) flowers are arranged in aments, with pistillate (female) flowers located at their base. This species is notable for the fragrant aroma emitted from its wood. Its fruit consists of a self-dehiscent, dry capsule that explodes in summer when mature, dispersing seeds a few meters away from the parent plant. The species possesses long-lasting renewal buds in a subterranean structure known as a lignotuber. This feature suggests that C. odorifera possesses a rich evolutionary history, with an ancient population that supports a diverse age structure, indicating its resilience and adaptability to changing environments [5]. Murillo [6] and Espinoza [7] noted that C. odorifera has a milky juice used to induce decayed teeth to fall out and relieve toothaches. This white latex comes off when the plant suffers cuts in various parts. Later, Gusinde [8] and de Mössbach [9] documented that latex from cut roots was used to poison arrows and spears. Moreover, Vitorino et al. [10] state that the main parts of the C. integerrima plant used in traditional medicine are the aerial organs and the white latex, both of which have been used as plasters for analgesic purposes [11]. A decoction of the plant was also utilized as a disinfectant for vaginal infections [9]. Bittner et al. [12] documented that C. odorifera was used as an analgesic. Cordero et al. [13] reported that the four Colliguaja species are used for livestock feed. The literature does not specify which part of the plant was used for toothaches or vaginal infections. However, Bittner et al. [12] reported the antimicrobial activity of leaves and stems of C. salicifolia, C. odorifera, and C. integerrima against Escherichia coli, Staphylococcus aureus, and Staphylococcus lutea, and leaves and stems of the last two species showed anti-tumor activity over lymphocytic leukemia in mice, and human nasopharyngeal carcinoma. Alvarez et al. [14] reported that an aqueous infusion of the aerial parts of C. integerrina showed a moderate diuretic activity.

Chemical studies on the Colliguaja genus have been limited to the identification of secondary metabolites, which are indicative of phylogenetic relationships. However, Vitorino et al. [10] dedicate a chapter to reviewing the principal chemical constituents and bioactive compounds of C. integerrima, highlighting the presence of flavonoids such as kaempferol, daidzein, pelargonidin, and delphinidin. On the contrary, C. odorifera has received little attention regarding its phytochemistry. In this respect, cis-1,4-polyisoprene, n-heptacosane (17%), and n-nonacosane (82%) were identified in stems and leaves of C. odorifera when they were extracted with dichloromethane and acetone [15,16]. Later, Bittner et al. [3] identified known triterpenes such as lupeol, ursolic acid, β-sitosterol, and oleanolic acid, and also flavonoid glycosides as quercetin-3-O-glucoside, quercetin-3-O-glucosyl-rhamnoside, and quercetin-3-O-rhamnosyl-arabinoside. The compounds were extracted from the whole plant through mixture of methanol/dichloromethane/hexane (1:1:1). Regarding to the bioactivity of these compounds, lupeol has been extensively studied for its inhibitory effects on inflammation under in vitro and in animal models of inflammation [17], and quercetin-3-O-glucoside has shown an anti-lipoxygenase effect [18]. However, there are not reports focused in the chemical basis related to the medicinal uses of C. odorifera.

Consequently, this study aimed to evaluate the anti-inflammatory activities of C. odorifera leaf extracts using in vitro assays and to characterize the secondary metabolites of the most active extract.

2. Results

2.1. LOX Inhibitory Activity of Colliguaja Odorifera Leaf Extracts

Compounds that inhibit the LOX enzyme are potential candidates for anti-inflammatory activity. Ethyl acetate extract and butanol extract (B-E) derived from the hydroalcoholic extract (HA-E) of C. odorifera exhibited differing levels of LOX inhibitory activity. EA-E demonstrated the highest LOX inhibition among the extracts, with an IC50 value of 11.75 ± 1.86 µg/mL. This was followed by the B-E, which exhibited an IC50 of 42.50 ± 10.61 µg/mL. The crude extract (HA-E) showed an IC50 of 64.56 ± 12.92 µg/mL, and W-E did not elicit an anti-LOX activity (Table 1).

Table 1.

LOX inhibitory activity of C. odorifera extracts and isolated phenolic compounds.

The phenolic compounds, shikimic acid and gallic acid, isolated from EA-E, exhibited significant LOX inhibitory activity, with IC50 values of 0.97 ± 0.04 µg/mL and 0.37 ± 0.15 µg/mL, respectively. The positive controls, quercetin and naproxen, elicited 50% inhibition of LOX activity at concentrations of 0.48 ± 0.03 µg/mL (1.59 µM) and 0.56 ± 0.02 µg/mL (2.5 µM), respectively.

The EA-E of C. odorifera was selected for further analysis due to its better performance in the anti-LOX assay.

2.2. sPLA2 and Hyaluronidase Inhibitory Activities of C. odorifera Leaf Extracts

To assess the anti-inflammatory effects of C. odorifera leaf extracts and their compounds, the inhibitory activities against the enzymes sPLA2 and hyaluronidase, which depolymerize hyaluronic acid (HA), can also be evaluated. Gallic acid showed the best performance in inhibiting sPLA2-V activity (IC50 11.16 μg/mL). It was statistically different from quercetin and EA-E, with IC50 values of 23.48 μg/mL and 31.09 μg/mL, respectively. Moreover, gallic acid exhibited the highest hyaluronidase activity (IC50 1.76 µg/mL), which was statistically similar to that of the positive control (quercetin, IC50 1.80 µg/mL). Ethyl acetate extract showed the lowest hyaluronidase inhibition (IC50, 6.6 µg/mL), and shikimic acid did not elicit anti-sPLA2-V and anti-hyaluronidase activities (Table 2).

Table 2.

Anti-inflammatory activity of C. odorifera leaves and isolated phenolic compounds.

2.3. Chemical Characterization of the Ethyl Acetate Extract (EA-E)

From 898 g of dry leaves of C. odorifera, 236 g of ethyl acetate extract (EA-E), 218 g of butanol extract (B-E), and 95 g of water residue (W-E) were obtained, yielding 26.3% 24.3%, and 10.6%, respectively. The EA-E of C. odorifera exhibited the strongest LOX, hyaluronidase, and sPLA2 inhibition, according to the results presented in Table 1 and Table 2. Figure 1 and Table 3 show the chromatogram and the identification of the compound present in EA-E from C. odorifera leaves. The main compounds were tentatively identified by co-chromatography with authentic standards, by comparing their UV spectra, mass spectrometric data, and NMR data, and by consulting the PubChem database and various scientific literature sources. Positive ionization data were used for identification, and sodium was used to improve detection sensitivity and accuracy.

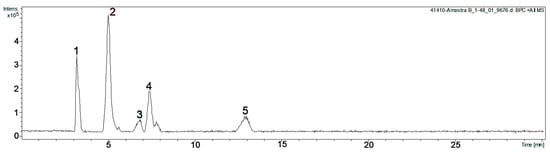

Figure 1.

HPLC-MSMS chromatogram of the ethyl acetate extracts from Colliguaja odorifera leaves. 1: Shikimic acid; 2: gallic acid; 3: methyl gallate; 4: ethyl gallate; 5: galloyl luteolin.

Table 3.

Mass spectrum and NMR data of compounds purified from the EA-E of C. odorifera leaves.

Peak 1 showed a [M + Na]+ ion at m/z 197 corresponding to m/z 174 in addition to Na+ (m/z 23), and a fragment ion at m/z 157, possibly due to the loss of a hydroxyl group (-OH). This compound was isolated by column chromatography from EA-E, and NMR data allowed it to be assigned to this peak as shikimic acid.

Peak 2 showed an [M + Na]+ ion at m/z 193 corresponding to m/z 170 in addition to Na+, and fragment ions at m/z 171 and 153 would correspond to the protonation of the neutral molecule and the loss of the -OH group, respectively. NMR data of this isolated compound were consistent with the presence of gallic acid.

Peak 3 showed an [M + H]+ ion at m/z 185, and the NMR data of this isolated compound were consistent with those of methyl gallate.

Peak 4 showed an [M + Na]+ ion at m/z 221 corresponding to the molecular ion m/z 198 in addition to Na+. The fragment ion at m/z 199 would correspond to the protonation of the neutral molecule. NMR data of this isolated compound were consistent with the presence of ethyl gallate.

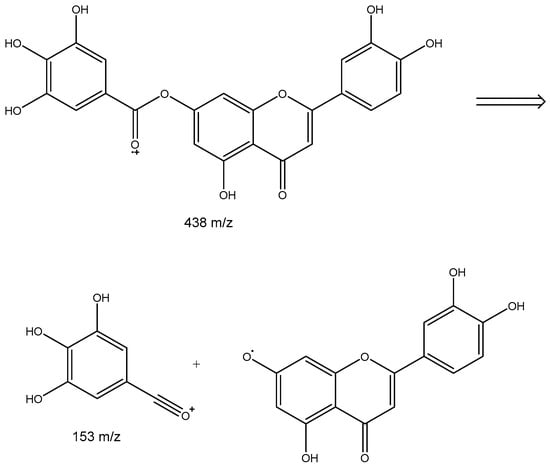

Peak 5 would correspond to a putative galloy luteolin. Figure 2 shows the possible fragmentation of this compound, showing a [luteolin + Na]+ ion at m/z 309 and a [gallic acid-OH]+ ion at 153.

Figure 2.

Proposed fragmentation of galloyl luteolin.

3. Discussion

LOX is a key enzyme that regulates the conversion of arachidonic acid into leukotrienes, which mediate inflammatory responses. Inhibiting LOX activity reduces leukotriene production (pro-inflammatory mediators), exerting an anti-inflammatory effect [19]. LOXs are categorized with respect to their positional specificity of arachidonic acid oxygenation. In our case, the soybean Type I-B LOX A oxygenates linoleic acid at C-15 [20]. Loncaric et al. [21] reviewed the inhibitory LOX activity of plant extracts from various families, highlighting their effectiveness in inhibiting soybean lipoxygenases. They reported IC50 values ranging from 0.01 µg/mL to 899.97 µg/mL for the different extracts and plant parts. This study represents the first report on the anti-inflammatory activity of the Chilean Euphorbiaceae C. odorifera. The ethyl acetate extract of C. odorifera leaves elicited a strong anti-LOX response (IC50 = 11.75 µg/mL).

According to Table 4, the anti-LOX IC50 ethyl acetate extract of C. odorifera leaves is better than those elicited by other Euphorbiaceae species. The comparisons are challenging due to the use of different extraction solvents and natural compounds, such as baicalein and nordihydroguaiaretic acid, used as positive controls. On the contrary, the anti-LOX activity elicited here by EA-E was compared with that of naproxen, a nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory drug (NSAID) used to relieve pain, reduce inflammation, and act as an antipyretic. Like other non-selective NSAIDs, naproxen exerts its clinical effects by inhibiting cyclooxygenase-1 and cyclooxygenase-2, thereby decreasing prostaglandin synthesis. However, reports have shown that naproxen can inhibit the LOX enzyme [22].

Table 4.

Lipoxygenase inhibition by extracts of plants of the family Euphorbiacea.

Moreover, our result (anti-LOX IC50 = 11.75 µg/mL) is even better than those obtained for different families (Apiaceae and Lamiaceae), but less active than species from the families Clisiaceae and Menispermaceae (Table 5).

Table 5.

Lipoxygenase inhibition by extracts of plants of species belonging to different families.

All these investigations attributed the anti-LOX activity to total flavonoid content, and the solvent most commonly used facilitated the extraction of flavonoids and phenolic compounds [33,34]. Numerous studies have provided robust evidence for the potent anti-inflammatory effects of ethyl acetate fractions and the compounds they contain [21,35,36]. In the present study, two phenolic compounds, shikimic acid and gallic acid, identified in EA-E, exhibited strong anti-LOX activity, with concentrations of 5.6 µM and 2.2 µM, respectively, comparable to those of the positive controls, quercetin (1.6 µM) and Naproxen (2.5 µM).

Another approach to assessing the anti-inflammatory effects of compounds is to evaluate their inhibitory activity against the enzyme sPLA2. The PLA2 superfamily has been classified into 16 groups (groups I to XVI) [37]. PLA2 groups can also be divided into six subfamilies namely into secreted PLA2s (sPLA2s) (groups I, II, III, V, IX, X, XI, XII, XIII and XIV), cytosolic PLA2s (cPLA2s) (group IV), Ca2+-independent PLA2s (iPLA2s) (group VI), platelet-activating factor acetylhydrolase PLA2s (PAF-AH PLA2s) (groups VII and VIII), lysosomal PLA2s (LPLA2s) (group XV) and adipose-tissue-specific PLA2s (AdPLA2s) (group XVI) [38,39]. This enzyme plays a critical role in the inflammatory response by releasing fatty acids, such as arachidonic acid, from cellular membrane phospholipids. Arachidonic acid is a key precursor in the synthesis of pro-inflammatory mediators, including prostaglandins and leukotrienes [40]. Furthermore, compounds that inhibit sPLA2 are considered promising candidates for the development of new anti-inflammatory drugs. Group V of sPLA2 was selected here because: (a) it is a more versatile isoform and plays a central role in amplifying the inflammatory response, (b) This enzyme binds to cell membranes via interfacial binding and to proteoglycans, and (c) prefers to hydrolyze lipids with unsaturated fatty acids in the sn-2 position having a low degree of unsaturation, such as oleic acid (C18:1) and linoleic acid (C18:2) [37]. The role of sPLA2-V as an enzyme initiating eicosanoid generation is well documented [41]. However, to our knowledge, no work has been conducted on Euphorbiaceae species to measure the inhibitory activity of this enzyme. The ability to inhibit sPLA2 activity of EA-E from C. odorifera (IC50 of 31.09 µg/mL) was comparable to the inhibition shown by Ribes nigrum (27.7 μg/mL) [42], Ononis spinose (39.44 μg/mL) [39], and Boerhaavia diffusa (17.8 μg/mL) [43]. These results show that EA-E from C. odorifera leaves falls within the range of hyaluronidase activity reported for different plant species.

Hyaluronidase depolymerizes hyaluronic acid (HA), thereby regulating the size and concentration of HA chains and influencing various pathological processes. They are crucial targets for the development of new agents to inhibit inflammation [44]. As far as we know, there are no reports of anti-HA activity of Euphorbiaceae species. In this study, EA-E from C. odorifera leaves showed HA inhibition with an IC50 of 6.6 µg/mL. Gallic acid and quercetin showed the highest inhibition, with IC50 values of 1.76 and 1.31 µg/mL, very similar to the positive control, quercetin (1.80 and 0.17 µg/mL) (Table 2). However, HA inhibition by plant extracts has been reported in other families. Paun et al. [27] reported an IC50 of 24.6 ± 1.5 µg/mL for HA elicited from a polyphenolic fraction of the aerial parts of E. planum L. (Apiaceae). Additionally, Studzińska-Sroka et al. [45] examined the anti-inflammatory activity of a hydroalcoholic extract from Galinsoga parviflora (Asteraceae), demonstrating anti-hyaluronidase activity with an IC50 of 0.47 mg/mL, which is stronger than that of the positive control, kaempferol, with an IC50 of 0.78 mg/mL.

In the present study, shikimic acid was not active against sPLA2 V and HA. Balsinde et al. [46] reported that an indole derivative and a naphthalenic derivative, both aromatic, inhibited phospholipase A2 activity. This suggests that the absence of an aromatic ring in shikimic acid may explain its lack of activity. A similar explanation can be applied to the lack of effect of shikimic acid on HA. The main anti-inflammatory drugs, such as celecoxib, nimesulide, indomethacin, and fenoprofen, among others, reported as HA inhibitors [47], possess one or more aromatic rings. This suggests that the planarity of a specific part of the molecule may be essential for the activity of certain compounds on HA.

The promising anti-inflammatory activity exhibited by C. odorifera leaves can be attributed to the phenolic compounds identified in the ethyl acetate extract. Among the chemical compounds capable of inhibiting LOX catalytic activity, the actions of different classes of phenolic compounds, such as flavonoids, catechins, carotenoids, and isoflavones, have been studied [48,49].

In this respect, the phenolic acids, shikimic and gallic acid, and phenol esters, methyl gallate and ethyl gallate, were identified in the EA-E from C. odorifera leaves in the present study. Shikimic acid possesses noteworthy biological properties, exhibiting antioxidant, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory, and analgesic activities [50]. Our results showed that shikimic acid exhibited LOX inhibitory activity similar to Naproxen (IC50, 0.56 ± 0.02 µg/mL), consistent with the literature. Gallic acid is widely utilized in the pharmaceutical sector. It is effective in inhibiting cardiovascular diseases, Alzheimer’s disease, and Parkinson’s disease [51] and exhibits anti-inflammatory activity [52]. Methyl gallate is commonly found in the Euphorbiaceae family. Research has demonstrated that methyl gallate exhibits various pharmacological activities, including anti-tumor, anti-inflammatory, and anti-microbial effects [53]. Recently, anti-inflammatory and anti-nociceptive activities have been associated with a high abundance of methyl gallate, 1,2,3,4,6-pentagalloylhexose, and quercitrin [54]. Ethyl gallate (EG) has been shown to exhibit anti-inflammatory activity in cell organelles, which may be beneficial in the treatment of inflammatory diseases. In India, Pistacia integerrima Linn. galls, which naturally contain EG, are used in traditional medicine [55,56].

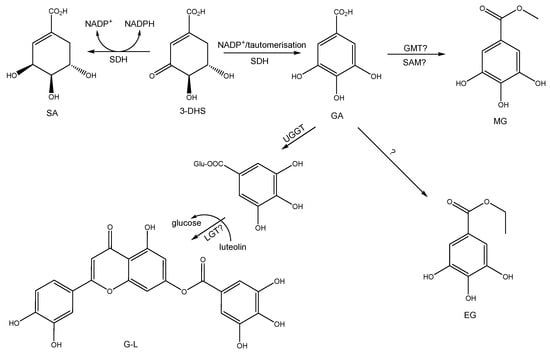

Based on the report by Huang et al. [57], we propose a hypothetical biosynthetic mechanism, as shown in Figure 3. Shikimic acid can be formed from 3-dehydroshikimate and NADPH, catalyzed by SA dehydrogenase (SDH) [58,59]. Gallic acid is mainly derived from the dehydrogenation of 3-DHS by the action of SDH [60]. Ossipov et al. [61] have suggested that NADP+ participates as a cofactor in this reaction, and a tautomerization of the keto-enolic type is proposed to form gallic acid. The formation of galloyl-luteolin could be similar to that proposed by Huang et al. [57] in Camellia sinensis, where, in the first step, gallic acid is glucosylated through UGGT. Then, a putative luteolin-galloyl-transferase would form galloyl-luteolin, similar to how gallic acid glucosylated and catechin are synthesized into gallic acid glucosylated and catechin [57].

Figure 3.

Biosynthetic pathway proposed for gallic acid (GA), shikimic acid (SA), methyl gallate (MG), ethyl gallate (EG), and galloyl-luteolin (GL). SDH, SA dehydrogenase; GMT, galloyl-O-methyltransferase; UGGT, UDP-glucose: gallate 1-O-galloyltransferase; LGT, luteolin-gallloyltransferase in Colliguaja odorifera; SAM: S-adenosyl methionine; 3-DHS: 3-dehydro shikimic acid; ? is a suggestion, because it has not determined or isolated the proper enzyme or coenzyme.

GA appears to be a precursor of most of the compounds identified in the EA-E, and is an essential precursor for the putative galloyl-luteolin biosynthesis. This fact could be related to the vast amount of this compound found in the EA-E. GA was the most abundant compound in EA-E, with an estimated concentration of 85.0 mg/g, as determined by a calibration curve using the respective pure standard. This finding may be related to the formation of the three gallate derivatives, including methyl gallate, ethyl gallate, and galloyl-luteolin. This investigation constitutes the first report of the anti-inflammatory potential of C. odorifera. However, the butanol extract also showed strong anti-LOX activity; further work is ongoing to identify the responsible compounds.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Plant Collection and Extracts Obtention

Plants of C. odorifera were collected between the Valparaíso Region and the La Araucanía Region (Chile) in October 2020. The plant materials were then carefully transferred to the Chemical Ecology Laboratory at the Universidad de La Frontera in Temuco, Chile. The species was identified as Colliguaja odorifera Molina by the Botany Department at Universidad de Concepción, and voucher specimens were deposited in the Universidad de Concepción’s herbarium (Herbarium code No. CONC 13817).

Leaves (898 g) of C. odorifera were thoroughly washed four times with fresh tap water and once with distilled water to remove dirt, soil, and contaminants. They were air-dried at room temperature (25 ± 2 °C) for 14 days, then dried for an additional 24 h at 30 ± 2 °C in a laboratory dryer before being ground into a coarse powder. The leaves were defatted with CHCl3, then the defatted leaves were macerated with ethanol (80%) in distilled water [21,61,62] for seven days with periodic stirring. After maceration, the mixture was filtered, and the solution was concentrated in a rotary evaporator at reduced pressure until the ethanol was eliminated. The remaining water was removed by freeze-drying to obtain the hydro-alcoholic extract (HA-E). This extract was subsequently dissolved in 1 L of distilled water and partitioned between ethyl acetate, n-butanol, and water. Each partitioning step was performed three times in a 1:1 ratio of sample to solvent [63,64,65]. After each organic phase was dried with anhydrous Na2SO4, vacuum-filtered, and evaporated to dryness using a rotary evaporator, three extracts were obtained: Ethyl acetate extract (EA-E), n-butanol extract (B-E), and water extract (W-E). These extracts were subjected to enzymatic bioassays and phytochemical characterization. All solvents used in this study were purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA) and were of chromatographic grade, ensuring their purity.

4.2. Inhibitory LOX Activity

The inhibitory LOX assay was conducted according to the procedure established by Lyckander and Malterud [66]. The lipoxygenase Type I-B LOX A from Glycine max L. (soybean) (CAS: 9029-60-1) (15-LOX) with an optimal pH of 8.0–9.0 and linoleic acid used here, was obtained from Sigma-Aldrich (Steinheim, Germany).

A linoleic acid ethanol solution (268 µM) was prepared, and 50 µL of this solution was used to prepare concentrations ranging from 0.6 to 26 µg/mL for the HA-E sample, and from 0.6 to 12.9 µg/mL for the EA-E and B-E samples. Then the volume for each concentration was adjusted to 1 mL with 200 mM borate buffer (pH 8.75) containing 0.005% Tween 80. The reaction was initiated by adding 1.5 µL of Soybean 1-LOX (948 U), equivalent to 0.054 g/mL. Enzymatic activity was monitored by measuring the increase in absorbance at 234 nm for 4 min at 37 °C. Each enzyme measurement for each dilution was repeated three times. All tests were performed in triplicate. For this purpose, three samples were taken from each extract. For each of them, enzymatic activity was determined as described above. Naproxen was used as the positive control. The percentage inhibition of enzyme activity was calculated by comparing the absorbance of the samples to that of the blank, using Equation (1) [67], where A0 is the absorbance of the blank, and A1 is the absorbance of the sample.

% inhibition = [(A0 − A1)/A0] × 100

The percentage of inhibition was plotted against sample concentration to calculate the IC50 value.

4.3. Screening Assay for Phospholipase A2 Inhibitors (Type V)

The phospholipase A2 inhibitory activity was determined using the phospholipase A2 (sPLA2) inhibitor detection assay kit (Type V). This kit was purchased from Cayman Chemical Co. (Ann Arbor, MI, USA). Briefly, 10 μL of C. odorifera extracts (HA-E, EA-E, B-E, and W-E, separately) were pre-incubated with 25 mM Tris-HCl buffer at pH 7.5, including 10 μL of phospholipase A2. The reaction was initiated by adding 200 μL of a 1.66 mM diheptanoyl thio-PC substrate solution. The plate was then shaken for 30 s and incubated at 25 °C for 15 min. Then, 10 µL of 5,5′-dithiobis(2-nitrobenzoic acid) (DTNB) was added to stop the enzymatic reaction and allow color development. The reaction mixture was stirred on a shaker for one minute, and the absorbance was subsequently measured at 405 nm with a spectrophotometer (METASH, UV-1500B; Shanghai Metash Instrument Co., Shanghai, China). According to the kit instructions, the sPLA2 activity was evaluated with extract concentrations ranging from 27 to 108 μg/mL. Arachidonic thioester phosphatidylcholine was used as the positive control [68]. Moreover, quercetin was also used as a positive control because it is known for its anti-inflammatory activity through modulation of enzymes in the arachidonic acid cascade [69]. All tests were performed in triplicate.

4.4. Hyaluronidase Inhibition Assay

The hyaluronidase inhibitory activity of the extracts was assessed using the Hyaluronidase Inhibitor Detection Assay Kit purchased from Sigma-Aldrich (St. Louis, MO, USA), which employs a two-step turbidimetric reaction to measure the amount of hyaluronic acid hydrolyzed by the enzyme, where the decrease in turbidity is proportional to the enzymatic activity of the sample. The assay was conducted according to the manufacturer’s instructions, with slight modifications, using 96-well plates [70]. Briefly, a reaction mixture containing 10 μL of C. odorifera extract (HA-E, EA-E, B-E, and W-E, separately) and 20 μL of the enzyme (at a concentration of 100 U/mL in incubation buffer) was mixed in each well. After a 15 min incubation at 37 °C, a 20 μL substrate solution (0.1% sodium hyaluronate) was added to each well. The plates were incubated at 37 °C for an additional 20 min. Then, non-hydrolyzed hyaluronidase was precipitated by adding 250 μL of 2.5% cetyltrimethylammonium bromide (CTAB). The plates were incubated at 25 °C for 10 min. The intensity of complex formation was measured by absorbance at 630 nm in a spectrophotometer (METASH, UV-1500B). All samples were tested in quadruplicate. The percentage of hyaluronidase inhibition was calculated using Equation (2), where AS is the absorbance of the solution with the sample extract, AC is the absorbance of the solution without inhibitor, and AT is the absorbance of the enzyme.

Inhibition = (AS − AC)/(AT − AC) × 100

4.5. Analysis of EA-E by High-Performance Liquid Chromatography Coupled to High Resolution Electrospray Ionization Mass Spectrometry (HPLC-HR-ESI-MS)

Because the highest anti-inflammatory activity was shown by the ethyl acetate extract (EA-E), it was analyzed by high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC) coupled to a high-resolution electrospray ionization mass spectrometry (HR-ESI-MS), which was conducted using a Shimadzu HPLC system (Kyoto, Japan), equipped with a Shimadzu Diode Array Detector (DAD) (Kyoto, Japan). A sample concentration of 10 mg/μL of EA-E was separated using a Luna Phenomenex C18 column (4.6 × 250 mm, with a particle size of 5 μm and a pore size of 120 Å) (Phenomenex, Torrance, CA, USA). The mobile phase consisted of an 85:15 water: acetonitrile mixture, with a flow rate of 1.5 mL/min. Detection was performed at 237 nm. Mass spectrometry detection was performed in positive-ion mode using a Bruker micrOTOF-QII (Billerica, MA, USA) coupled to an Apollo ion source. The dry temperature was set at 200 °C, with a capillary voltage of 4.5 kV. The mass-to-charge ratios (m/z) were measured in both scan mode (m/z 100–1200 Da) and production scan mode (m/z 50–1200 Da) [71,72].

4.6. Isolation and Identification of the Main Compounds in EA-E

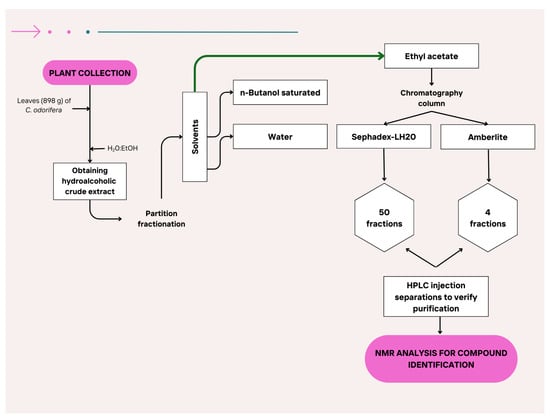

EA-E separation was performed by column chromatography. One gram of ethyl acetate extract was dissolved in methanol and placed at the top of a glass column (30 cm long × 5 cm diameter) packed with 100 mg of Amberlite (Sigma-Aldrich, St. Louis, MO, USA), which had been previously washed with an acidic water solution at pH 2. These fractions were lyophilized and dissolved in MeOH:H2O (1:1, v/v) for preparative HPLC-DAD analysis. Samples were filtered through a 0.22 µm PVDF membrane (Millipore) before injection. A UHPLC Thermo Ultimate 3000 system (Waltham, MA, USA) with a column XBridge® C18 (5 µm, 250 × 10 mm) (Waters Corporation, Milford, MA, USA) was used to isolate pure compounds. The analysis was performed using a linear solvent gradient consisting of 1% formic acid (A) and acetonitrile (B) according the following gradient: 0–5 min, 15% B; 5–15 min, 30% B; 15–20 min, 50% B; 20–25 min, 100% B at a flow rate of 1 mL/min. Then, each fraction was analyzed by one-dimensional 1H and 13C NMR in a Varian (Palo Alto, CA, USA) (500 MHz) (Figure 4). Between 1 and 40 mg of compound fraction was dissolved in approximately 0.6 mL of DMSO-d6. These samples were filtered through a 45 µm porous diameter filter and then introduced into NMR tubes measuring 5 mm in diameter and 16.5/18 cm in length [73].

Figure 4.

Isolation flow of compounds identified in the ethyl acetate fraction.

4.7. Statistical Analysis

Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (s.d.). One-way ANOVA was used to test for overall differences. The significant ANOVA was followed by Duncan multiple comparisons to assess pairwise differences between treatment groups. A p-value of less than 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

5. Conclusions

This study demonstrated the significant anti-inflammatory potential of Colliguaja odorifera, an endemic Chilean plant traditionally used in folk medicine. The ethyl acetate extract inhibited key inflammatory enzymes, including LOX, hyaluronidase, and sPLA2. Phytochemical analysis revealed the presence of bioactive compounds, including shikimic acid, gallic acid, methyl gallate, ethyl gallate, and galloyl-luteolin, which may contribute to the observed pharmacological activity. According to Loncaric et al. [21], an IC50 of 11.75 µg/mL for LOX could be considered a strong-to-moderate response. However, these results need to be validated using cytotoxicity or cell-based bioassays. These findings support the traditional use of C. odorifera and suggest its potential as a natural source for developing safer alternatives to conventional anti-inflammatory drugs. Further studies are required to explore their mechanisms of action in detail. However, our results suggest that C. odorifera could inhibit the oxygenation in C-15 of unsaturated fatty acid and/or inhibit the hydrolysis of unsaturated fatty acids in the sn-2 position, such as oleic acid (C18:1) and linoleic acid (C18:2).

Author Contributions

A.F.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Investigation, Methodology, Writing—original draft, and Writing—review and editing. A.M.: Data curation and Methodology. E.H. (Emilio Hormazabal): Data curation and Methodology. J.E.: Data curation, Methodology, and Writing—review editing. O.R.: Conceptualization, Data curation, and Methodology. E.H. (Edward Hermosilla): Formal analysis and Writing—review and editing. J.G.L.: Data curation, Formal analysis, and Methodology. A.Q.: Conceptualization, Data curation, Formal analysis, Methodology, Writing—review and editing, and supervision. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by ANID/FONDAP/1523A0001 and Universidad de La Frontera grant number DI20-0016. The APC was partially financed by Dirección de Investigación—Vicerrectoría de Investigación y Postgrado, VRIP-UFRO.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

I would like to thank the internationalization scholarship from Universidad de La Frontera, which was granted to facilitate my stay in Brazil and my PhD in Natural Resources Sciences, for the economic and academic support that enabled me to carry out this work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| LOX | Lipoxygenase |

| sPLA2 | Secretory phospholipase |

| HA | Hyaluronidase |

| EA-E | Ethyl acetate extract |

| B-E | Butanol extract |

| W-E | Water extract |

References

- Xu, Y.; Tang, P.; Zhu, M.; Wang, Y.; Sun, D.; Li, H.; Chen, L. Diterpenoids from the genus Euphorbia: Structure and biological activity (2013–2019). Phytochemistry 2021, 190, 112846. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Marticorena, C. Contribución a la estadística de la flora vascular de Chile. Gayana Bot. 1990, 47, 85–113. [Google Scholar]

- Bittner, M.; Alarcón, J.; Aqueveque, P.; Becerra, J.; Hernández, V.; Hoeneisen, M.; Silva, M. Estudio químico de especies de la familia Euphorbiaceae en Chile. Bol. Soc. Chil. Quím. 2001, 46, 419–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodríguez, R.; Marticorena, C.; Alarcón, D.; Baeza, C.; Cavieres, L.; Finot, V.L.; Fuentes, N.; Kiessling, A.; Mihoc, M.; Pauchard, A.; et al. Catálogo de las plantas vasculares de Chile. Gayana Bot. 2018, 75, 1–430. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bull-Hereñu, K.; MartÍnez, E.; Squeo, F. Structure and genetic diversity in Colliguaja odorifera Mol. (Euphorbiaceae), a shrub subjected to Pleisto-Holocenic natural perturbations in a Mediterranean South American región. J. Biogeogr. 2005, 32, 1129–1138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Murillo, D. Memoria Sobre Plantas Medicinales de Chile y el Uso que de Ellas se Hacen en el País; Imprenta del Ferrocarril: Santiago, Chile, 1861; p. 627. [Google Scholar]

- Espinoza, E. Plantas medicinales de Chile. In Jeografía Descriptiva de La República de Chile, 1st ed.; Espinoza, E., Ed.; Imprenta i Encuadernación Barcelona: Santiago, Chile, 1897; pp. 3–15. [Google Scholar]

- Gusinde, M. Plantas medicinales que los indios Araucanos recomiendan. Anthropos 1936, 31, 555–571. [Google Scholar]

- de Mösbach, E.W. Botánica Indígena de Chile, 2nd ed.; Ediciones Mac-Kay: Puerto Varas, Chile, 2023; pp. 91–92. [Google Scholar]

- Bittner, M.; Becerra, J.; Hoeneisen, M.; Silva, M. Chemical and biological studies of Chilean species of Euphorbiaceae. In Flora de Chile: Biología, Farmacología y Química, 1st ed.; Muñoz, O., Fajardo, V., Eds.; Universidad de Playa Ancha: Valparaíso, Chile, 2005; pp. 69–85. [Google Scholar]

- Cordero, S.; Gálvez, F.; Abello, L. Usos Tradicionales de la Flora de Chile, 1st ed.; Ediciones Botánicas, Editorial Planeta de papel Ltda: Valparaíso, Chile, 2020; Volume I, p. 408. [Google Scholar]

- Alvarez, M.; Gil, R.; Acosta, M.; Saad, R.; Borkowski, E.; María, A. Diuretic activity of aqueous extract and botulin from Colliguaja integerrima in rats. Pharmac. Biol. 2009, 47, 274–278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitorino, G.P.; Quezada, D.P.; Mamuncurá, M.S.; Córdoba, O.S.; Flores, M.J. Colliguaja integerrina Gillis & Hook. In Medicinal and Aromatic Plants of South America Vol. 2 Argentina, Chile and Uruguay; Máthé, Á., Bandoni, A., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; Volume 7, pp. 173–181. [Google Scholar]

- Ciampagna, M.L. Estudio de la Interacción Entre Grupos Cazadores Recolectores de Patagonia y las Plantas Silvestres: El Caso de la Costa Norte de Santa Cruz Durante el Holoceno Medio y Tardío. Ph.D. Thesis, Facultad de Ciencias Naturales y Museo, Universidad Nacional de La Plata, La Plata, Argentina, 2014; p. 537. [Google Scholar]

- Gnecco, S.; Bartulín, J.; Marticorena, C.; Ramírez, A. Chilean Euphorbiaceae as sources of fuels and raw chemicals. Biomass 1988, 15, 165–173. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gnecco, S.; Bartulin, J.; Becerra, J.; Marticorena, C. n-Alkanes from Chilean Euphorbiaceae and Compositae species. Phytochemistry 1989, 8, 1251–1256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, M. Lupeol, a novel anti-inflammatory and anti-cancer dietary triterpene. Cancer Lett. 2009, 285, 109–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nile, A.; Nile, S.H.; Shin, J.; Park, G.; Oh, J.-W. Quercetin-3-glucoside extracted from apple pomace induces cell cycle arrest and apoptosis by increasing intracellular ROS levels. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 10749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Ma, S. Recent development of lipoxygenase inhibitors as anti-inflammatory agents. Med. Chem. Commun. 2018, 9, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Harmut, K.; Thiele, B.J. The diversity of the lipoxygenase family: Many sequence data but little information on biological signi¢cance. FEBS Lett. 1999, 449, 7–11. [Google Scholar]

- Loncaric, M.; Strelec, I.; Moslavac, T.; Šubaric, D.; Pavic, V.; Molnar, M. Lipoxygenase inhibition by plant extracts. Biomolecules 2021, 11, 152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Iqbal, A.; Abbas, W.; Ejaz, S.; Riaz, N.; Ashok, A.K.; Hayat, M.M.; Ashraf, M. Mulimodal evaluation of lipoxygenase-targeting NSAIDs using integrated in vitro, SAR, in silico, cytotoxicity towards MCF-7 cell line, DNA docking and MSD simulation approaches. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 214, 143665. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saleem, H.; Ahmad, I.; Gill, M.S.A. Evaluation of lipoxygenase inhibition of Jatropha gossypifolia, a medicinal plant from Pakistan. Bangladesh J. Pharmacol. 2016, 11, 319. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palit, P.; Mandal, S.C.; Bhunia, B. Total steroid and terpenoid enriched fraction from Euphorbia neriifolia Linn offers protection against nociceptive-pain, inflammation, and in vitro arthritis Model: An insight of mechanistic study. Int. Immunopharmacol. 2016, 41, 106–115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mbhele, N.; Ncube, B.; Ndhlala, A.R.; Moteetee, A. Pro-inflammatory enzyme inhibition and antioxidant activity of six scientifically unexplored indigenous plants traditionally used in South Africa to treat wounds. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2022, 147, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ngouana, V.; Tsouh, V.; Donfack, V.; Kemzeu, R.; Dongmo, Y.; Kamdem, B.; Bakarnga-Via, I.; Jazet, P.; Fekam, F. Antifungal, antiradical and anti-inflammatory properties of four Euphorbiaceae species. Curr. Top. Phytochem. 2022, 18, 65–78. [Google Scholar]

- Paun, G.; Neagu, E.; Moroeanu, V.; Albu, C.; Savin, S.; Radu, G. Chemical and bioactivity evaluation of Eryngium planum and Cnicus benedictus polyphenolic-rich extracts. BioMed Res. Int. 2019, 2019, 3692605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phosrithong, N.; Nuchtavorn, N. Antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of Clerodendrum leaf extracts collected in Thailand. Eur. J. Integr. Med. 2016, 8, 281–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marlin, S.; Elya, B. Antioxidant activity and lipoxygenase enzyme inhibition assay with total flavonoid content from Garcinia hombroniana Pierre leaves. Phcog. J. 2017, 9, 267–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Avelia, S.; Mauldina, M.G.; Elya, B. Antioxidant activity and lipoxygenase inhibitory assay with total flavonoid content of Garcinia lateriflora Blume leaves extract. Asian J. Phar. Clin. Res. 2017, 10, 163–165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Putri, N.L.; Elya, B.; Puspitasari, N. Antioxidant activity and lipoxygenase inhibition test with total flavonoid content from Garcinia kydia Roxburgh leaves extract. Phcog. J. 2017, 9, 280–284. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Handayani, E.; Nuraini, P. Cyclea barbata leaf extract: Lipoxygenase inhibitory activity and phytochemical screening. Int. J. Appl. Pharm. 2018, 10, 106–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sobeh, M.; Hamza, M.S.; Ashour, M.L.; Elkhatieb, M.; El Raey, M.A.; Abdel-Naim, A.B.; Wink, M. A polyphenol-rich fraction from Eugenia uniflora exhibits antioxidant and hepatoprotective activities in vivo. Pharmaceuticals 2020, 13, 84. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arniati, M.P.; Baits, M.; Tahir, M. Determination of total phenolic levels of ethyl acetate fraction of llove leaves (Syzygium aromaticum (L.) Merr). Pharm. Rep. 2022, 1, 29–32. [Google Scholar]

- Subardini, D.; Elya, B.; Noviani, A. Lipoxygenase inhibitory assay of ethyl acetate fraction from star fruit leaves (Averrhoa carambola l.) from three regions in west java. Int. J. Appl. Pharmac. 2020, 12, 119–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nishida, Y.; Sugahara, S.; Wada, K.; Toyohisa, D.; Tanaka, T.; Ono, M.; Yasuda, S. Inhibitory effects of the ethyl acetate extract from bulbs of Scilla scilloides on lipoxygenase and hyaluronidase activities. Pharm. Biol. 2014, 52, 1351–1357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.A.; Ilies, M.A. The phospholipase A2 Superfamily: Structure, isozymes, catalysis, physiologic and pathologic roles. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2023, 24, 1353. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dennis, E.A.; Cao, J.; Hsu, Y.-H.; Magrioti, V.; Kokotos, G. Phospholipase A enzymes: Physical structure, biological function, disease implication, chemical inhibition, and therapeutic intervention. Chem. Rev. 2011, 111, 6130–6185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Six, D.A.; Dennis, E.A. The expanding superfamily of phospholipase A2 enzymes: Classification and characterization. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 2000, 1488, 1–19. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Boilard, E.; Lai, Y.; Larabee, K.; Balestrieri, B.; Ghomashchi, F.; Fujioka, D.; Gobezie, R.; Coblyn, J.S.; Weinblatt, M.E.; Massarotti, E.M.; et al. A novel anti-inflammatory role for secretory phospholipase A2 in immune complex-mediated arthritis: Opposing functions of sPLA2in arthritis. EMBO Mol. Med. 2010, 2, 172–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Balestrieri, B.; Arm, J.P. Group V sPLA2: Classical and novel functions. BBA 2006, 1761, 1280–1288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arnold, E.; Benz, T.; Zapp, C.; Wink, M. Inhibition of cytosolic phospholipase A2α (cPLA2α) by medicinal plants in relation to their phenolic content. Molecules 2015, 20, 15033–15048. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giresha, A.S.; Pramod, S.N.; Sathisha, A.D.; Dharmappa, K.K. Neutralization of inflammation by inhibiting in vitro and in vivo secretory A2 by ethanol extract of Boerhaavia diffusa L. Pharmacogn. Res. 2017, 9, 174–181. [Google Scholar]

- Stern, R.; Asari, A.A.; Sugahara, K.N. Hyaluronan fragments: An information rich system. Eur. J. Cell Biol. 2006, 85, 699–715. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Studzińska-Sroka, E.; Dudek-Makuch, M.; Chanaj-Kaczmarek, J.; Czepulis, N.; Korybalska, K.; Rutkowski, R.; Łuczak, J.; Grabowska, K.; Bylka, W.; Witowski, J. Anti-inflammatory activity and phytochemical profile of Galinsoga parviflora cav. Molecules 2018, 23, 2133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balsinde, J.; Balboa, M.A.; Insel, P.A.; Dennis, E.A. Regulation and inhibition of phospholipase A2. Annu. Rev. Pharmacol. Toxicol. 1999, 39, 175–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Girish, K.S.; Kemparaju, K.; Nagaraju, S.; Vishwanath, B.S. Hyaluronidase Inhibitors: A biological and therapeutic perspective. Curr. Med. Chem. 2009, 16, 2261–2288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medina, A.V.; Nazareno, M.A.; Chaillou, L.L. Inhibitory effect of phenolic compounds on lipoxygenase activity in reverse micellar systems. Food Biosci. 2024, 62, 105039. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.-Y.; Thakur, K.; Wei, C.-K.; Wang, H.; Zhang, J.-G.; Wei, Z.-J. Evaluation of inhibitory activity of natural plant polyphenols on Soybean lipoxygenase by UFLC-mass spectrometry. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2019, 120, 179–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Batory, M.; Rotsztejn, H. Shikimic acid in the light of current knowledge. J. Cosmet. Dermatol. 2021, 21, 501–505. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Middleton, E.; Kandaswami, C.; Theoharides, T.C. The effects of plant flavonoids on mammalian cells: Implications for inflammation, heart disease, and cancer. Pharmacol. Rev. 2000, 52, 673–751. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kroes, K.H.; van der Berg, A.J.J.; Quarles van Ufford, H.C.; van Dijk, H.; Labadie, R.P. Anti-inflammatory activity of gallic acid. Planta Med. 1992, 58, 499–504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liang, H.; Huang, Q.; Zou, L.; Wei, P.; Lu, J.; Zhang, Y. Methyl gallate: Review of pharmacological activity. Pharmacol. Res. 2023, 194, 106849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Galvão, F.; dos Santos, E.; Dantas, F.; Santos, J.; Sauda, T.; dos Santos, A.; Carvalho Souza, R.; Pinto, L.; Moraes, C.; Sangalli, A.; et al. Chemical composition and effects of ethanolic extract and gel of Cochlospermum regium (Schrank) Pilg. Leaves on inflammation, pain, and wounds. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2023, 302, 115881. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hongxia, C.; Yuan, J.; Du, X.; Wang, M.; Yue, M.; Liu, J. Ethyl gallate suppresses proliferation and invasion in human breast cancer cells via Akt-NF-κB signaling. Oncol. Rep. 2015, 33, 1284–1290. [Google Scholar]

- Muddu, C.; Jayaprakash, N.K.; Asha, S.; Sravan, T. Biological potential of ethyl gallate. Res. J. Biotech. 2024, 19, 122–125. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, K.; Li, M.; Liu, Y.; Zhu, M.; Zhao, G.; Zhou, Y.; Zhang, L.; Wu, Y.; Dai, X.; Xia, T.; et al. Functional analysis of 3-dehydroquinate dehydratase/shikimate dehydrogenases involved in shikimate pathway in Camellia sinensis. Front. Plant Sci. 2019, 10, 1268. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasama, J.S.T.; Ohishi, M.; Ding, L.; Hofus, D.; Hajirezaei, M.-R.; Ferni, A.R. Functional analysis of the essential bifunctional tobacco enzyme 3-dehydroquinate dehydratase/shikimate dehydrogenase in transgenic tobacco plants. J. Exp. Bot. 2007, 58, 2053–2067. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maeda, H.; Dudareva, N. The shikimate pathway and aromatic amino acid biosynthesis in plants. Annu. Rev. Plant Biol. 2012, 63, 73–105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dewick, P.M.; Haslam, E. Phenol biosynthesis in higher plants. Gallic acid. Biochem. J. 1969, 113, 537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ossipov, V.; Salminen, J.P.; Ossipova, S.E.; Pihlaja, K. Gallic acid and hydrolysable tannins are formed in birch leaves from an intermediate compound of the shikimate pathway. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2003, 31, 3–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lekouagheta, A.; Boutefnouchetc, A.; Bensuicie, C.; Galie, L.; Ghenaietb, K.; Tichati, L. In vitro evaluation of antioxidant and anti-inflammatory activities of the hydroalcoholic extract and its fractions from Leuzea conifera L. roots. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2020, 132, 103–107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Silva, G.; Tanic, M.; Rocha, J.; Serrano, R.; Gomes, E.T.; Sepodes, B.; Silva, O. In vivo anti-inflammatory effect and toxicological screening of Maytenus heterophylla and Maytenus senegalensis extracts. Hum. Exp. Toxicol. 2010, 30, 693–700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Çoruh, N.; Özdoğan, N. Identification and quantification of phenolic components of Rosa heckeliana Tratt roots. J. Liq. Chromatogr. Relat. Technol. 2015, 38, 569–578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abubakar, A.R.; Haque, M. Preparation of medicinal plants: Basic extraction and fractionation procedures for experimental purposes. J. Phar. Bioallied Sci. 2020, 20, 1–10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lyckander, I.M.; Malterud, K.E. Lipophilic flavonoids from Orthosiphon spicatus as inhibitors of 15-lipoxygenase. Acta Phar. Nord. 1992, 4, 159–166. [Google Scholar]

- Ben-Nasr, S.; Aazza, S.; Mnif, W.; Miguel, M.G.C. Antioxidant and anti-lipoxygenase activities of extracts from different parts of Lavatera cretica L. grown in Algarve (Portugal). Pharmacog. Mag. 2015, 11, 48. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- George, A.; Chinnappan, S.; Chintamaneni, M.; Kotak, V.; Choudhary, Y.; Kueper, T.; Radhakrishnan, A.K. Anti-inflammatory effects of Polygonum minus (Huds) extract (Lineminus™) in in-vitro enzyme assays and carrageenan-induced paw edema. BMC Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 14, 355. Available online: http://www.biomedcentral.com/1472-6882/14/355 (accessed on 12 December 2025). [CrossRef]

- Lättig, J.; Böhl, M.; Fischer, P.; Tischer, T.; Tietböhl, C.; Menschikowski, M.; Gutzeit, H.O.; Metz, P.; Pisabarro, M.T. Mechanism of inhibition of human secretory phospholipase A2 by flavonoids: Rationale for lead design. J. Comput. Aided Mol. Des. 2007, 21, 473–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perera, H.D.S.M.; Samarasekera, J.K.R.R.; Handunnetti, S.M.; Weerasena, O.V.D.S.J. In vitro anti-inflammatory and anti-oxidant activities of Sri Lankan medicinal plants. Ind. Crop. Prod. 2016, 94, 610–620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wolfender, J.L. HPLC in natural product analysis: The detection issue. Planta Med. 2009, 75, 719–734. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Solano-Cueva, N.; Figueroa, J.G.; Loja, C.; Armijos, C.; Vidari, G.; Ramírez, J.A. Validated HPLC-UV-ESI-IT-MS Method for the quantification of carnosol in Lepechinia mutica, a medicinal plant endemic to Ecuador. Molecules 2023, 28, 6701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rosler, K.H.; Goodwin, R.S. A general use of Amberlite XAD-2 resin for the purification of flavonoids from aqueous fractions. J. Nat. Prod. 1984, 47, 188. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).