Abstract

Plant essential oils (EOs) are attracting interest as ecofriendly alternatives to antibiotics and copper-based control of kiwifruit bacterial canker (KBC), caused by Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae (Psa). This study chemically profiled six EOs (anise, basil, cardamom, cumin, fennel, and laurel) and evaluated their antimicrobial activity both in vitro and in planta. The in vitro assay targeted four strains, two of Psa and two of the low-virulent P. syringae pv. actinidifoliorum (Pfm), whereas the in planta assay focused on the highly virulent Psa7286 strain, assessed under preventive and curative application regimes (i.e., 14 days pre- or post-inoculation, respectively). Cumin, with cuminaldehyde as its major component (48%), was the most effective EO in vitro, significantly inhibiting growth at 5–10% concentration, whereas anise, rich in anethole (89%), was consistently the least effective one. However, the in planta application of the EOs produced antimicrobial effects that differed markedly from in vitro results and showed strong dependence on the timing of application. Preventive treatment significantly reduced Psa endophytic populations in basil (70%), anise (54%), laurel (42%), and cumin (35%) compared to untreated plants. In contrast, when the EOs were applied post-inoculation (curative treatment), a significant decrease in Psa colonization was observed in laurel (81%), cardamon (70%), cumin (31%) and fennel (29%). Although plant EOs are gaining momentum in the control of Psa and other diseases, translation from in vitro to in planta efficacy is not direct and is strongly timing-dependent, which underscores the need to perform validation trials in planta and to fine-tune application schedules for the integrated management of KBC.

1. Introduction

Kiwifruit bacterial canker, caused by Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae (Psa), is a major constraint to plant growth and productivity, driving substantial economic losses and demanding rigorous orchard management [1]. This pathogen is now reported from all major kiwifruit-producing regions and can infect virtually all Actinidia species, including cultivated A. chinensis and A. arguta [2]. By contrast, P. syringae pv. actinidifoliorum (Pfm) is less virulent; although it does not typically cause severe yield losses, it compromises plant fitness through necrotic leaf spots [3,4]. Control of both Gram-negative pathovars is important for crop performance, yet research attention has focused predominantly on Psa due to its global impact on kiwifruit health [5]. These efforts have delivered several candidate control strategies, including plant defense inducers and microbial biological control agents, at varying levels of technological maturity, with few products currently commercialized [6]. In practice, management has relied largely on copper-based compounds and, where permitted, antibiotics such as streptomycin. However, their continued use is increasingly discouraged due to limited and inconsistent efficacy and to environmental and human health concerns [7,8,9,10]. Despite incremental advances, robust and reliable control of Psa remains elusive, and antibacterial options for Pfm have received comparatively little attention [11]. In fact, closely related nonpathogenic or mildly virulent populations, such as Pfm, can act as reservoirs of virulence factors, enabling the emergence of more aggressive variants [5]. There is, therefore, a clear need to broaden the portfolio of safe and effective tools for kiwifruit disease management. In particular, molecules that prevent infection and/or lower endophytic bacterial loads in already infected plants are a priority for integrated programs [6].

Plant essential oils (EO) are promising candidates because they combine direct antimicrobial activity with the capacity to elicit plant defense responses and may also enhance copper efficacy when used in nanoformulations [6,12,13,14]. These complex mixtures can include substances from tens of chemical groups, with one or a few bioactive constituents often accounting for most of the composition [15,16,17]. Reported antibacterial mechanisms include disruption of the cell envelope that increases membrane permeability and leads to leakage of cellular contents, as well as interference with motility, the type III secretion system, and quorum sensing [18,19,20]. Many essential oils and their constituents are active at low concentrations, a practical advantage since phytotoxicity and poor water miscibility often necessitate low-concentration emulsions stabilized with surfactants [21,22]. However, in planta evaluations of EOs have focused mainly on fungal and oomycete diseases, while bacterial targets are less studied. Seed and soil treatments with plant EOs have reduced disease caused by diverse fungi in several horticultural crops, although effective concentrations, carriers, and timings vary [23,24,25,26,27,28]. For example, seed priming with EOs from cumin, basil, and geranium at 4% reduced root rot in cumin caused by Fusarium spp. [23], while seed priming with oregano EO at 12% also lowered the severity of Sclerotinia sclerotiorum in lima bean [28]. In potted tomato seedlings, oregano and clove EOs at concentrations up to 0.01% significantly decreased symptoms caused by Botrytis cinerea and Ralstonia solanacearum, respectively [24,25]. Likewise, clove EO emulsions at up to 10% limited disease caused by Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici in potted tomato seedlings [26]. In greenhouse trials, a soil drench with lemon EO at 50 mL per plant reduced symptom severity caused by Phytophthora sp. on pepper, cucumber, and melon relative to untreated controls [27]. More recently, garlic and cinnamon essential oils have been encapsulated in silver nanoparticles, which enhanced their fungicidal activity against Botrytis cinerea, a major pathogen of horticultural crops [29]. The nanoformulated oils inhibited mycelial growth and conidial germination and caused cell wall disruption and deformed hyphae. In addition, chitosan nanoparticles loaded with lemon or spinach seed essential oils showed strong antifungal activity against Penicillium expansum (blue mold of apple) and Podosphaera fusca (powdery mildew of cucumber), while inducing defense-related and antioxidant enzymes, including polyphenol oxidase, peroxidase and phenylalanine ammonia lyase, without compromising fruit quality [30,31].

Most work on Psa has evaluated the antibacterial activity of PEOs and plant extracts in vitro [15,16,17,19], whereas in planta efficacy against Psa remains limited [13,20,32]. In kiwifruit, foliar applications of EOs from savory, thyme, and pennyroyal have shown inconsistent outcomes across studies [13,32]. Under greenhouse conditions, applying savory and thyme EOs 24 h before Psa inoculation, followed by nine further applications over 15 weeks, reduced both the number of diseased leaves and the affected leaf area. In contrast, in micropropagated plants treated 3 days before inoculation, winter savory at 5 mg.mL−1 produced negligible inhibition relative to pennyroyal [13]. Also, cinnamon EO-based emulsion markedly decreased disease frequency and severity, although protection was weaker when cinnamon was combined with oregano and when treatment was applied 24 h after inoculation rather than 24 h before [20]. Under field conditions, cinnamon EO applied at bloom and then at three monthly intervals was more effective than cinnamon or a cinnamon plus oregano mixture in lowering the disease index for up to four months after treatment. However, when oregano was combined with cinnamon, the mixture performed worse than cinnamon alone, indicating that oregano can diminish the protective effect of cinnamon [20]. Together with the weaker protection observed when cinnamon was applied after inoculation rather than before, these results point to complex, non-additive interactions among EOs and emphasize that mixture composition and application timing critically shape outcomes. In addition, variability across studies likely arises from differences in EO chemistry, the genotypes of both bacteria and host plants, and the formulation, concentration, application method and timing, and growth conditions used. These sources of heterogeneity underscore the need for standardized comparative trials that explicitly contrast preventive and curative schedules.

In this context, chemical profiling is essential to interpret bioassays, identify candidate bioactive constituents, and improve comparability across studies; however, many reports do not include full composition data. In several cases, chemical analyses of PEOs with stronger anti-Psa activity identified piperitenone oxide in apple mint, pulegone and menthone in pennyroyal, borneol in rosemary, caryophyllene in sage, camphene and cinnamyl acetate in laurel, and terpinene-4-ol in tea tree as the most abundant constituents [13,16]. Individual compounds such as carvacrol and juglone also showed strong inhibition of Psa by disrupting cell membrane permeability and integrity [33,34], and cinnamaldehyde, eugenol, estragole, and methyl-eugenol also inhibited in vitro, with efficacy varying across Psa strains [15]. Yet, focusing on single constituents does not fully explain whole-oil performance because constituent interactions can be synergistic or antagonistic. For example, eugenol, estragole, and methyl-eugenol exhibited high inhibitory activity, but extracts of West Indian Bay tree and Jamaica pepper, both rich in these molecules, were only as effective as Chinese cinnamon, where these compounds were not detected [15]. Similarly, although bergamot oil contained more thymol than a closely related wild species (59–64% versus 38–42%), their anti-Psa activities were comparable, likely due to carvacrol present in wild bergamot (at about 3.9%) [17]. These patterns underline that overall antimicrobial potential reflects the full chemical matrix rather than any single dominant component. In addition, the potential of plant EOs against Pfm remains largely unexplored. Although this pathovar is less destructive than Psa, its management is relevant in orchards where multiple Pseudomonas pathovars may co-occur. Moreover, despite the recent withdrawal of the European Commission’s proposal to halve pesticide use by 2030 under the “Farm to Fork Strategy” due to lack of political consensus, the need to develop sustainable alternatives remains urgent. In this regard, incorporating plant EOs as both preventive and curative control strategies against KBC will contribute to achieving this objective. As such, this study tests the hypothesis that EOs effective in vitro against Psa and Pfm strains will also exhibit activity in planta against Psa, with their performance being conditioned by the application timing. Six widely used spice and herb oils—anise, cumin, fennel, basil, laurel, and cardamom—were therefore evaluated to: (i) quantify in vitro antibacterial activity against both pathovars; (ii) compare the sensitivity of strains differing in virulence; (iii) validate preventive and post-infection efficacy in planta against Psa7286; and (iv) characterize chemical composition to relate constituents to antimicrobial performance and to identify candidates for future management tools.

2. Results

2.1. In Vitro and In Planta Antimicrobial Activity Against Psa and Pfm

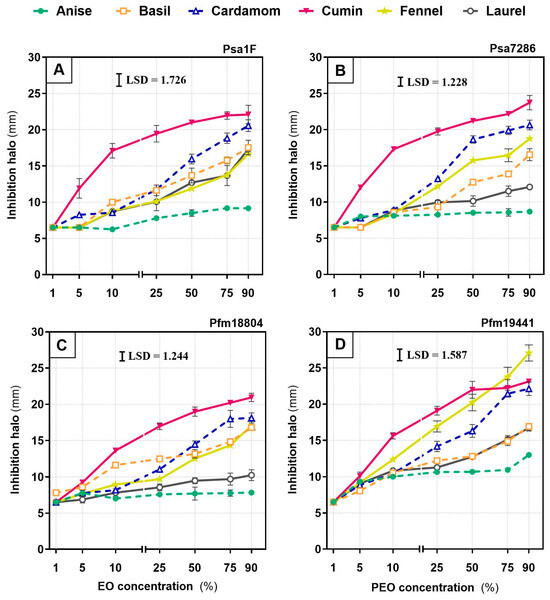

Across the four strains and six essential oils, in vitro inhibition increased with oil concentration, with strong concentration–response relationships (R2 = 0.67–0.99). The exception was anise against Psa7286 and Pfm18804, which showed weaker fits (R2 = 0.50 and 0.42, respectively; Supplementary Materials Table S1). Overall, cumin was the most effective in vitro, producing large inhibition halos at comparatively low concentrations (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Inhibition zone diameter (mm) of Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae (Psa; strains 1F—(A), and 7286—(B)) and P. syringae pv. actinidifoliorum (Pfm; strains 18804—(C), and 19441—(D)) measured after 48 h exposure to six essential oils: anise, basil, cardamom, cumin, fennel, and laurel. Oils were tested at 1, 5, 10, 25, 50, 75 and 90% v/v. Each symbol is the mean of three biological replicates, and error bars indicate the standard error of the mean. The least significant difference (LSD) at p < 0.05 is shown in each panel.

Cumin generally yielded inhibition halos from 9.2 ± 0.6 mm at 5% to 23.7 ± 1.0 mm at 90% across all strains, with fennel significantly outperforming cumin against Pfm19441 at 90% (reaching 27.1 ± 1.1 mm). In contrast, anise was consistently the least active EO, with the smallest halos even at 90%, ranging from 8.7 ± 0.4 mm for Psa7286 to 13.0 ± 0.2 mm for Pfm19441. Basil, cardamom, and laurel showed intermediate activity. At 5%, their halos reached up to 8.6 ± 0.2 mm, 8.8 ± 0.4 mm, and 9.1 ± 0.2 mm, respectively, and at 90% they reached 17.5 ± 1.0 mm, 22.1 ± 0.9 mm, and 17.3 ± 0.3 mm, respectively. However, some strain-specific differences were evident, including within pathovars. For example, at 90%, among Psa strains, Psa1F was more sensitive to laurel than Psa7286 (p < 0.0001) but less sensitive to fennel (p < 0.01), and among Pfm strains, Pfm19441 was more sensitive than Pfm18804 to anise (p < 0.0001), cardamom and cumin (p < 0.05), fennel and laurel (p < 0.01).

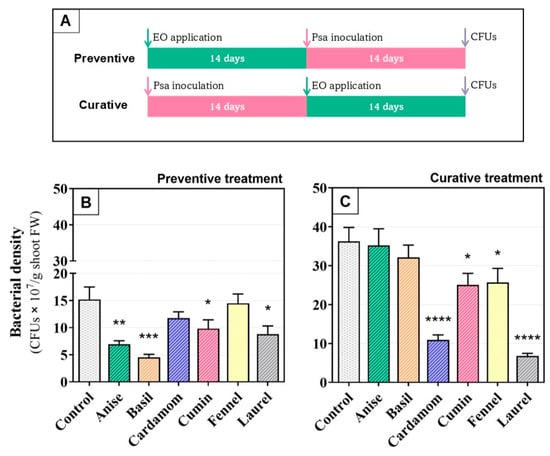

Concerning the in planta trials, in untreated inoculated plants (control), the endophytic population of Psa increased over time, reaching 15 ± 4.0 × 107 colony-forming units per gram (CFU·g−1) of shoot tissue at 14 days post inoculation (dpi) and 36 ± 6.2 × 107 CFU·g−1 at 28 dpi (Figure 2B and Figure 2C, respectively).

Figure 2.

(A) In planta application of six plant essential oils at 0.1% (v/v), 14 days pre-inoculation (preventive treatment) or 14 days post-inoculation (curative treatment) and the respective (B,C) endophytic population of Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae in shoots of Actinidia chinensis var. deliciosa ‘Tomuri’ expressed as CFU·g−1 fresh weight. Control plants were inoculated but received no essential oil treatment. Bars represent the means of three biological replicates, and error bars indicate the standard error of the means. Different letters denote significant differences among treatments within each panel (ANOVA with Fisher’s LSD, p < 0.05). Significance levels are indicated as follows: ****, p < 0.0001; ***, p < 0.001; **, p < 0.01; *, p < 0.05.

Preventive application of EOs significantly reduced Psa colonization for basil (70%), anise (54%), laurel (42%), and cumin (35%), relative to the untreated control, whereas cardamom and fennel produced no significant change (Figure 2B). In contrast, when EOs were applied as curative treatment against Psa basil and anise had no significant effect, whereas laurel, cardamom, cumin, and fennel lowered Psa loads by 81, 70, 29, and 31%, respectively (Figure 2C). Overall, anise and basil only worked out as preventive treatments, whereas cardamom and fennel were only effective as curative treatments. Interestingly, cumin and laurel had broader action, with significant efficacy in both preventive and curative application regimes.

2.2. Chemical Characterization of the EOs

Chemical profiling revealed differing levels of complexity among the studied EOs (Table 1, Supplementary Materials). Anise, basil and cardamom contained the largest number of identified constituents, from 23 to 24 compounds, whereas fennel, cumin and laurel had 18 to 20. A closer look at relative abundances highlights distinct chemical signatures (Table 1).

Table 1.

Most abundant constituents of anise, basil, cardamom, cumin, fennel, laurel essential oils shown as relative composition percent from GC-MS analysis. Remaining identified compounds are listed in Supplementary Material. Abbreviations: ND—not detected.

Anise showed the highest levels of anethole (89%), while basil was characterized by very high estragole (93%). Cardamom was rich in β-himachalene (78%), with lower amounts of D-limonene (7.4%), and linalyl acetate (3.8%). Cumin showed elevated cuminaldehyde (48%), β-cymene (19%), and 3-carene (14%). Fennel was dominated by 1,8-cineole (69%; also known as eucalyptol), with β-himachalene (17%), bornyl acetate (1.7%), terpinen-4-ol and γ-terpinene (both at 1.0%). Laurel contained substantial anethole (78%), fenchone (9.1%), and estragole (6.7%). Despite these differences, all EOs shared four compounds: estragole (0.44% to 93%), linalyl acetate (0.02% to 3.8%), and terpinen-4-ol (0.02% to 1.0%) and ρ-cymene (0.01% to 0.89%). On the other hand, several constituents were exclusive to a single EO. For example, longifolene, thunbergol and γ-himalachene were only detected in anise (at 3.8, 1.5, and 0.55%, respectively), β-isocumene and nerol acetate in cardamom (at 1.2 and 1.1%, respectively), and chrysanthenol and phellandral were detected only in cumin (at 9.2 and 0.69%, respectively).

3. Discussion

Kiwifruit bacterial canker caused by Psa requires a diversified toolkit of sustainable control molecules that can limit endophytic colonization and help manage the emergence of chemical resistance [9,10]. Although Pfm is less virulent and typically poses limited direct economic risk, coinfection could weaken plant fitness and potentially exacerbate the impact of Psa where both occur [35]. Within this context, the present study contributes to identify sustainable options by expanding our knowledge on the list of EOs with activity against Psa and, for the first time, exploring potential inhibitory effects against Pfm.

In the In vitro assays, all tested essential oils significantly inhibited both pathovars in a predominantly concentration-dependent manner. Nevertheless, cumin was consistently the most active EO, while anise showed the weakest activity. Overall, several oils showed steep increases in activity at low concentrations (≤10%), which is encouraging for practical use since low doses facilitate emulsification and reduce phytotoxic risk [22]. In this context, microencapsulation and other nanotechnology-based delivery systems could improve stability and provide controlled release, enabling equivalent or greater protective effects at even lower application rates and thereby reducing the total oil required [36,37]. among the oils with intermediate in vitro effects, fennel was the most effective against Pfm19441 at 75% and 90% concentrations. Nonetheless, for Pfm18804 and at all other concentrations, cumin remained the most active EO. Such variation, within and between pathovars, aligns with previous reports and argues for tailoring oil selection to pathogen lineage or using rational combinations that target multiple mechanisms simultaneously [15]. Indeed, synergistic activity from subinhibitory combinations has been shown for rosemary, tea tree, and apple mint against Psa [16] and, therefore, systematic testing across strain panels will be needed to map predictable response patterns and anticipate limitations. Our results substantiate prior evidence that basil, cumin, fennel, and laurel can inhibit Psa in vitro [16,19] and newly document activity for anise and cardamom. Earlier reports of no cardamom effect against Psa may reflect differences in chemotype or methodology, as composition was not disclosed [19]. Here, cardamom shared some constituents with published profiles, such as D-limonene and linalyl acetate, while being rich in β-himachalene, a feature also linked to antibacterial and antioxidant activity in Atlas cedar oil [38,39]. Conversely, discrepant findings for rosemary across studies illustrate how strain choice, plant chemotype, extraction method, concentration, and growth conditions can shift outcomes, underscoring the value of meta-analyses to resolve patterns and optimize use conditions [40,41,42]. Crucially, this study extends evidence from plates to plants. We show that cumin, fennel, basil, cardamom, laurel, and anise can reduce endophytic Psa loads in planta, but efficacy depends on timing. Preventive applications favored basil and anise, curative applications favored laurel and cardamom, while cumin performed in both windows, albeit with different magnitudes.

The mismatch between in vitro activity and in planta protection in some cases can be partly explained by additional barriers and host responses that govern outcomes in living tissues. At plant level the EOs can trigger defense mechanisms (e.g., improved antioxidant response and phytohormone modulation) that go beyond a direct pathogen growth inhibition [13,43]. Composition activity relationships help interpret these patterns but are not strictly additive. For instance, oils active against Psa often contain piperitenone oxide, pulegone, menthone, borneol, caryophyllene, camphene, cinnamyl acetate, and terpinene-4-ol, and single compounds such as carvacrol and juglone can disrupt membranes and strongly inhibit growth [13,16,33,34]. Yet interactions among constituents can be synergistic or antagonistic. Extracts rich in eugenol, estragole, and methyl eugenol were as effective as Chinese cinnamon extracts that lacked these compounds, and similar activity has been observed in oils with differing thymol and carvacrol proportions [15,17]. In this study, estragole was one of the few constituents present across all six oils, alongside very low amounts of ρ-cymene and terpinene-4-ol. The three oils with the highest estragole, basil then laurel then anise, were also the most effective in preventive applications, which suggests a role for elicitation. Estragole-rich matrices have primed resistance in several species, mostly against fungal pathogens, and multiple essential oils have enhanced host defenses in planta, although validation for Actinidia-Psa is still needed [12,44,45,46,47,48]. Under our experimental conditions, a purely surface protective effect seems less likely, given the high volatility of most constituents and the 14-day interval between application and inoculation. However, less volatile EO components, such as fatty acids, sterols and waxes, may persist for longer and could be retained by the surfactant used for emulsification [22,49].

Cardamom and laurel were more effective when applied after infection (as a curative approach), with cardamom showing limited preventive effects. Although their dominant constituents differ, β-himachalene in cardamom and 1,8-cineole in fennel, both have recognized antibacterial activities, and the overall activity could also reflect interactions among minor constituents [21,39,50]. In contrast, laurel and cumin reduced in planta bacterial density in both timing windows. For cumin, this dual action may derive from a diversified profile rather than a single driver. Cumin contained five constituents above 5%, with cuminaldehyde as the major component. Cuminaldehyde inhibits biofilm formation and proteolysis, reduces virulence, and increase membranes permeability in bacteria, with cumin oils rich in 3-caren-10-al and cuminaldehyde showing strong antioxidant capacity that could support plant defenses [51,52,53,54]. Similarly, cinnamaldehyde, the dominant component of Cinnamomum cassia oil, also targets bacterial membranes, and it has also been implicated in elicitation in apple leaves [15,55,56,57]; however, whether cumin also elicits defenses in Actinidia remains to be tested. Laurel and anise, both dominated by anethole, behaved similarly in vitro against Psa7286 and as preventive treatments, consistent with the antioxidant properties of anethole that may aid host defenses [58]. Nevertheless, their protective behavior diverged: laurel exhibited strong curative activity while anise did not, reflecting differences in their chemical profiles. For example, laurel contained higher levels of estragole plus fenchone and D-limonene, which were absent in anise. Although these compounds typically exhibit limited activity against Gram-negative bacteria, estragole has documented bactericidal effects on Psa and likely contributed to laurel’s superior curative efficacy [15,59,60,61,62,63].

Taken together, these results highlight that: (1) essential oil efficacy is timing dependent in planta, so preventive and curative windows should be tested explicitly; (2) composition alone does not dictate performance because interactions among constituents are common; selecting a single molecule based only on relative abundance is risky, and (3) cumin and laurel emerge as robust candidates against both Psa e and Pfm, while basil and anise appear most useful preventively and cardamom and fennel curatively. Future work should map strain level response surfaces, quantify elicitation markers in Actinidia following oil application, assess formulation variables that improve persistence without phytotoxicity, and test rational combinations at subinhibitory doses to exploit synergy while meeting practical constraints in kiwifruit orchards.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Essential Oil Emulsions

Plant essential oils from anise (Pimpinella anisum L., Ref.: AT155), basil (Ocimum basilicum L., Ref.: AT324), cardamom (Elettaria cardamomum L. Maton, Ref.: AT056), cumin (Cuminum cyminum L., Ref.: AT057), fennel (Foeniculum vulgare Mill., Ref.: AT111) and laurel (Laurus nobilis L., Ref.: AT116) were purchased from H. Reynaud & Fils, Montbrun Les Bains, France. For each oil, a 90% (v/v) stock emulsion was prepared by mixing the pure, undiluted oil with sterile distilled water containing 2% (v/v) Tween 20 as emulsifier. To control for surfactant effects, matching Tween 20 solutions without essential oil were prepared at the corresponding final concentrations and used as non-treated controls. All emulsions were shaken for 30 s immediately before being used to ensure homogeneity.

4.2. Bacterial Strains and In Vitro Antibacterial Assay

Two Psa strains, 7286 (CFBP, Italy) and 1F (ANSES, France), and two Pfm strains, 18,804 and 19,441 (both ICMP, New Zealand and Australia, respectively), were used [2,64]. Along the text, strains are referred to as Psa7286, Psa1F, Pfm18804 and Pfm19441. Cultures were maintained on nutrient sucrose agar (NSA) at 27 °C in the dark. For inoculum, a single colony of each strain was grown overnight in liquid Luria–Bertani medium at 27 °C and 75 rpm.

Antibacterial activity was assessed on NSA plates by paper disk diffusion [65]. Bacterial suspensions were adjusted to OD600 = 1.0, approximately 1 × 109 cells.mL−1, and spread onto separate plates. Sterile blank antimicrobial susceptibility disks (Thermo Fisher Scientific, MA, USA) were loaded with 10 µL of each essential oil emulsion or the corresponding Tween 20 control and placed at the center of inoculated plates. Plates were incubated at 27 °C for 48 h in the dark. Zones of growth inhibition were measured as the diameter of the inhibition halo, in millimeters, and compared with the negative controls. Each treatment was tested with three biological replicates, each comprising three technical replicates.

4.3. In Planta Validation of Antibacterial Activity Against Psa

Micropropagated Actinidia chinensis var. deliciosa ‘Tomuri’ plants, each with a single shoot 5 to 6 cm tall and 8 to 12 leaves, were obtained from QualityPlant (Castelo Branco, Portugal). Plants were maintained in vitro on modified full-strength Murashige and Skoog agar medium in a climate chamber as previously described [4].

Plants received essential oil treatments either 14 days before inoculation (preventive) or 14 days after inoculation (curative), as schematically depicted in Figure 2A. For each timing, nine plants per essential oil were treated. An additional set of nine plants per timing received 2% Tween 20 without essential oil as non-treated controls, resulting in a total of 126 plants. Treatments consisted of dipping shoots for 15 s in 0.1% v/v essential oil emulsions prepared from the stocks in Section 2.1. This concentration was selected based on preliminary tests that revealed phytotoxicity at higher levels.

For inoculation, a fresh suspension of Psa7286 at 1–2 × 107 CFU·mL−1 in sterile Ringer’s solution was prepared on the day of challenge, which involved immersing plant shots in the inoculum for 15 s. After treatment in the preventive schedule or after inoculation in the curative schedule, plants were maintained for 28 days in a climate chamber (Fitoclima 5000 EH, Aralab, Rio de Mouro, Portugal) with a 16 h light photoperiod and a light intensity of 200 μmol.s−1.m−2, 22 °C during the light period and 20 °C during the dark period. Sampling occurred at 14 days post inoculation in the preventive experiment and at 28 days post inoculation in the curative experiment. For this, plants were removed from the growing media, and shoots were homogenized in Ringer’s solution for endophytic Psa quantification by serial dilution and plating [4]. For each condition, three biological replicates were analyzed, each obtained by random pooling of three shoots.

4.4. Chemical Characterization by GC–MS

Essential oils were diluted in 10% ethanol (GC grade, Merck Group, Darmstadt, Germany). Samples were analyzed in triplicate on a Varian CP 3800 gas chromatograph with autosampler coupled to a Varian Saturn 4000 ion trap mass spectrometer, controlled by Varian software version 6.9.1. Separation used a VF 5 ms capillary column, 30 m × 0.25 mm × 0.25 µm, with high-purity helium as carrier at 1.0 mL.min−1 in splitless mode. The oven program was 40 °C for 1 min, ramp 5 °C min−1 to 250 °C with a 5 min hold, then 5 °C min−1 to 300 °C with no hold. Additional specifications followed Barros et al. [66]. Compounds were identified in a non-targeted approach by comparison with pure and mixed standards and by spectral matching against the NIST EPA NIH Mass Spectral Library version 2.2.

4.5. Statistical Analysis

Differences among means were evaluated by analysis of variance (ANOVA) followed by Fisher’s least significant difference test at p < 0.05. Analyses were performed in GraphPad Prism version 10.4.1, GraphPad Software, Boston, MA, USA.

5. Conclusions

This study extends prior in vitro observations for basil, cumin, fennel and laurel by demonstrating their activity against Psa and, for the first time, showing inhibitory effects against Pfm. It also documents previously unreported activity for anise and cardamom. Crucially, in planta experiments show that EOs can reduce endophytic Psa populations, but that in vitro efficacy does not translate directly to in planta effectiveness and is strongly dependent on application timing. The results identify distinct functional roles among the oils tested: basil and anise were effective only as preventive treatments, cardamom showed curative efficacy, and cumin and laurel performed well in both preventive and curative contexts. Chemical profiling linked bioactivity to candidate constituents such as anethole, estragole, himachalene, cuminaldehyde and 1,8-cineole, while emphasizing that overall composition alone does not reliably predict biological outcome because interactions among constituents are common. Future work should focus on standardizing EO formulations and doses for field use to reduce reliance on copper and antibiotics while minimizing phytotoxicity. Key priorities include benchmarking preventive and curative windows across diverse Psa and Pfm strains and Actinidia genotypes, testing rational EO combinations at subinhibitory concentrations to identify synergistic blends, and quantifying host elicitation markers and physiological responses (transient and cumulative) to clarify mechanisms of action. Together, these steps will help translate the present findings into robust, scalable tools for kiwifruit disease management.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/plants14243825/s1.

Author Contributions

S.M.P.C. and M.W.V. were responsible for the conception and design of the experimental work. S.M.P.C. was responsible for funding acquisition that financed the bulk of this research. M.N.d.S. conducted the chemical profiling of plant essential oils and the in vitro assays, and M.N.d.S. and M.G.S. performed in planta treatment, inoculation and sampling. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by National Funds from FCT—Fundação para a Ciência e a Tecnologia—through the projects PTDC/AGR-PRO/6156/2014, UID/5748/2025, UIDB/50016/2025, MGS’s PhD scholarships (https://doi.org/10.54499/2020.08874.BD) and MNS’s PhD scholarship (SFRH/BD/99853/2014) and CEEC (https://doi.org/10.54499/2023.06124.CEECIND/CP2855/CT0008).

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article/Supplementary Materials. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors gratefully acknowledge Bárbara Nascimento and Catarina Correia for the first in vitro screenings.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Froud, K.; Beresford, R.; Cogger, N. Risk factors for kiwifruit bacterial canker disease development in ‘Hayward’ kiwifruit blocks. Austral. Plant Pathol. 2017, 46, 421–431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Scortichini, M.; Marcelletti, S.; Ferrante, P.; Petriccione, M.; Firrao, G. Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae: A re-emerging, multi-faceted, pandemic pathogen. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2012, 13, 631–640. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cunty, A.; Poliakoff, F.; Rivoal, C.; Cesbron, S.; Fischer-Le Saux, M.; Lemaire, C.; Jacques, M.A.; Manceau, C.; Vanneste, J.L. Characterization of Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae (Psa) isolated from France and assignment of Psa biovar 4 to a de novo pathovar: Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidifoliorum pv. nov. Plant Pathol. 2015, 64, 582–596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes da Silva, M.; Vasconcelos, M.W.; Gaspar, M.; Balestra, G.M.; Mazzaglia, A.; Carvalho, S.M.P. Early pathogen recognition and antioxidant system activation contributes to Actinidia arguta tolerance against Pseudomonas syringae pathovars actinidiae and actinidifoliorum. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- González, A.J.; Díaz, D.; Ciordia, M.; Landeras, E. Occurrence of Pseudomonas syringae pvs. actinidiae, actinidifoliorum and other P. syringae strains on kiwifruit in Northern Spain. Life 2024, 14, 208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, M.G.; Nunes da Silva, M.; Vasconcelos, M.W.; Carvalho, S.M. Scientific and technological advances in the development of sustainable disease management tools: A case study on kiwifruit bacterial canker. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 14, 1306420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, H.S.; Koh, Y.J.; Hur, J.S.; Jung, J.S. Occurrence of the strA-strB streptomycin resistance genes in Pseudomonas species isolated from kiwifruit plants. J. Microbiol. 2004, 42, 365–368. [Google Scholar]

- Pietrzak, U.; McPhail, D.C. Copper accumulation, distribution and fractionation in vineyard soils of Victoria, Australia. Geoderma 2004, 122, 151–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colombi, E.; Straub, C.; Künzel, S.; Templeton, M.D.; McCann, H.C.; Rainey, P.B. Evolution of copper resistance in the kiwifruit pathogen Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae through acquisition of integrative conjugative elements and plasmids. Environ. Microbiol. 2017, 19, 819–832. [Google Scholar]

- Lee, Y.S.; Kim, G.H.; Koh, Y.J.; Jung, J.S. Mutation of rpsL gene in streptomycin-resistant Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae biovar 3 strains isolated from Korea. Res. Plant Dis. 2022, 28, 26–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nunes da Silva, M.; Carvalho, S.M.P.; Rodrigues, A.M.; Gómez-Cadenas, A.; António, C.; Vasconcelos, M.W. Defence-related pathways, phytohormones and primary metabolism are key players in kiwifruit plant tolerance to Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae. Plant Cell Environ. 2022, 45, 528–541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Banani, H.; Olivieri, L.; Santoro, K.; Garibaldi, A.; Gullino, M.L.; Spadaro, D. Thyme and savory essential oil efficacy and induction of resistance against Botrytis cinerea through priming of defense responses in apple. Foods 2018, 7, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oliveira-Fernandes, J.; Oliveira-Pinto, P.R.; Mariz-Ponte, N.; Sousa, R.M.; Santos, C. Satureja montana and Mentha pulegium essential oils’ antimicrobial properties against Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae and elicitor potential through the modulation of kiwifruit hormonal defenses. Microbiol. Res. 2023, 277, 127490. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Azarakhsh, M.; Gerivani, M. Antibacterial activity of chitosan/thyme essential oil/Copper nano-complexes against Pseudomonas syringae pv. syringae. Med. Plant 2025, 48, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, Y.-R.; Choi, M.-S.; Choi, G.-W.; Park, I.-K.; Oh, C.-S. Antibacterial activity of cinnamaldehyde and estragole extracted from plant essential oils against Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae causing bacterial canker disease in kiwifruit. Plant Pathol. J. 2016, 32, 363. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vavala, E.; Passariello, C.; Pepi, F.; Colone, M.; Garzoli, S.; Ragno, R.; Pirolli, A.; Stringaro, A.; Angiolella, L. Antibacterial activity of essential oils mixture against PSA. Nat. Prod. Res. 2016, 30, 412–418. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattarelli, P.; Epifano, F.; Minardi, P.; Di Vito, M.; Modesto, M.; Barbanti, L.; Bellardi, M.G. Chemical composition and antimicrobial activity of essential oils from aerial parts of Monarda didyma and Monarda fistulosa cultivated in Italy. J. Essent. Oil-Bear. Plants 2017, 20, 76–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Diao, W.-R.; Hu, Q.-P.; Zhang, H.; Xu, J.-G. Chemical composition, antibacterial activity and mechanism of action of essential oil from seeds of fennel (Foeniculum vulgare Mill.). Food Control 2014, 35, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pucci, N.; Orzali, L.; Modesti, V.; Lumia, V.; Brunetti, A.; Pilotti, M.; Loreti, S. Essential oils with inhibitory capacities on Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae, the causal agent of kiwifruit bacterial canker. Asian J. Plant Pathol. 2018, 12, 16–26. [Google Scholar]

- Danzi, D.; Thomas, M.; Cremonesi, S.; Sadeghian, F.; Staniscia, G.; Andreolli, M.; Bovi, M.; Polverari, A.; Tosi, L.; Bonaconsa, M.; et al. Essential oil-based emulsions reduce bacterial canker on kiwifruit plants acting as antimicrobial and antivirulence agents against Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae. Chem. Biol. Technol. Agric. 2025, 12, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verdeguer, M.; Sánchez-Moreiras, A.M.; Araniti, F. Phytotoxic effects and mechanism of action of essential oils and terpenoids. Plants 2020, 9, 1571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chang, Y.; Harmon, P.F.; Treadwell, D.D.; Carrillo, D.; Sarkhosh, A.; Brecht, J.K. Biocontrol potential of essential oils in organic horticulture systems: From farm to fork. Front. Nutr. 2022, 8, 805138. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hashem, M.; Moharam, A.; Zaied, A.; Saleh, F. Efficacy of essential oils in the control of cumin root rot disease caused by Fusarium spp. Crop Protect. 2010, 29, 1111–1117. [Google Scholar]

- Soylu, E.M.; Kurt, Ş.; Soylu, S. In vitro and in vivo antifungal activities of the essential oils of various plants against tomato grey mould disease agent Botrytis cinerea. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2010, 143, 183–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, Y.-H.; Choi, C.-W.; Kim, S.-H.; Yun, J.-G.; Chang, S.-W.; Kim, Y.-S.; Hong, J.-K. Chemical pesticides and plant essential oils for disease control of tomato bacterial wilt. Plant Pathol. J. 2012, 28, 32–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, A.; Rajendran, S.; Srivastava, A.; Sharma, S.; Kundu, B. Antifungal activities of selected essential oils against Fusarium oxysporum f. sp. lycopersici 1322, with emphasis on Syzygium aromaticum essential oil. J. Biosci. Bioeng. 2017, 123, 308–313. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amini, J.; Farhang, V.; Javadi, T.; Nazemi, J. Antifungal effect of plant essential oils on controlling Phytophthora species. Plant Pathol. J. 2016, 32, 16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cibanal, I.L.; Fernández, L.A.; Rodriguez, S.A.; Pellegrini, C.N.; Gallez, L.M. Propolis extract combined with oregano essential oil applied to lima bean seeds against Sclerotinia sclerotiorum. Eur. J. Plant Pathol. 2022, 164, 33–43. [Google Scholar]

- Bouqellah, N.A.; Abdulmajeed, A.M.; Rashed Alharbi, F.K.; Mattar, E.; Al-Sarraj, F.; Abdulfattah, A.M.; Hassan, M.M.; Baazeem, A.; Al-Harthi, H.F.; Musa, A.; et al. Optimizing encapsulation of garlic and cinnamon essential oils in silver nanoparticles for enhanced antifungal activity against Botrytis cinerea pathogenic disease. Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2025, 136, 102522. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dhanasekaran, S.; Liang, L.; Gurusamy, S.; Godana, E.A.; Yang, Q.; Zhang, H. Efficacy and mechanism of chitosan nanoparticles containing lemon essential oil against blue mold decay of apples. Int. J. Biol. Macromol. 2025, 308, 142633. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Soleimani, H.; Mostowfizadeh-Ghalamfarsa, R.; Ghanadian, M. Characterization, biochemical defense mechanisms, and antifungal activities of chitosan nanoparticle-encapsulated spinach seed essential oil. J. Agric. Food Res. 2025, 22, 102016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Monchiero, M.; Gullino, M.L.; Pugliese, M.; Spadaro, D.; Garibaldi, A. Efficacy of different chemical and biological products in the control of Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae on kiwifruit. Austral. Plant Pathol. 2015, 44, 13–23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ni, P.; Wang, L.; Deng, B.; Jiu, S.; Ma, C.; Zhang, C.; Almeida, A.; Wang, D.; Xu, W.; Wang, S. Combined application of bacteriophages and carvacrol in the control of Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae planktonic and biofilm forms. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Han, Q.; Feng, L.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, R.; Wang, G.; Zhang, Y. Effect of juglone against Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae planktonic growth and biofilm formation. Molecules 2021, 26, 7580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Figueira, D.; Garcia, E.; Ares, A.; Tiago, I.; Veríssimo, A.; Costa, J. Genetic diversity of Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae: Seasonal and spatial population dynamics. Microorganisms 2020, 8, 931. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baazeem, A.; Hassan, M.M.; Alqurashi, A.S.; Al Seberi, H.; Al-Harthi, H.F.; Al-Said, H.M.; Alhazmi, K.A.; Alnusaire, T.S.; AlShammari, W.; Alshammari, A.A.; et al. Peppermint and tarragon essential oils encapsulated in copper nanoparticles: A novel approach to sustainable fungal pathogen management in industrial crops. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 232, 121310. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weisany, W.; Samadi, S.; Tahir, N.A.-r.; Amini, J.; Hossaini, S. Nano-encapsulated with mesoporous silica enhanced the antifungal activity of essential oil against Botrytis cinerea (Helotiales; Sclerotiniaceae) and Colletotrichum nymphaeae (Glomerellales; Glomerellaceae). Physiol. Mol. Plant Pathol. 2022, 122, 101902. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Derwich, E.h.; Benziane, Z.; Boukir, A. Chemical composition and in vitro antibacterial activity of the essential oil of Cedrus atlantica. Int. J. Agric. Biol. 2010, 12, 381–385. [Google Scholar]

- El Hachlafi, N.; Mrabti, H.N.; Al-Mijalli, S.H.; Jeddi, M.; Abdallah, E.M.; Benkhaira, N.; Hadni, H.; Assaggaf, H.; Qasem, A.; Goh, K.W. Antioxidant, volatile compounds; antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and dermatoprotective properties of Cedrus atlantica (endl.) manetti ex carriere essential oil: In vitro and in silico investigations. Molecules 2023, 28, 5913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mori, Y.; Kuwano, Y.; Tomokiyo, S.; Kuroyanagi, N.; Odahara, K. Inhibitory effects of Moso bamboo (Phyllostachys heterocycla f. pubescens) extracts on phytopathogenic bacterial and fungal growth. Wood Sci. Technol. 2019, 53, 135–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bincy, K.; Remesh, A.V.; Reshma Prabhakar, P.; Vivek Babu, C.S. Differential fumigant and contact biotoxicities of biorational essential oil of Indian sweet basil and its active constituent against pulse beetle, Callosobruchus chinensis. Food Biosci. 2023, 51, 102283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simonetti, G.; Pucci, N.; Brasili, E.; Valletta, A.; Sammarco, I.; Carnevale, E.; Pasqua, G.; Loreti, S. In vitro antimicrobial activity of plant extracts against Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae causal agent of bacterial canker in kiwifruit. Plant Biosyst. 2020, 154, 100–106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashad, Y.M.; Abdel Razik, E.S.; Darwish, D.B. Essential oil from Lavandula angustifolia elicits expression of three SbWRKY transcription factors and defense-related genes against sorghum damping-off. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sefu, G.; Satheesh, N.; Berecha, G. Effect of essential oils treatment on anthracnose (Colletotrichum gloeosporioides) disease development, quality and shelf life of mango fruits (Mangifera indica L.). Am.-Eurasian J. Agric. Environ. Sci. 2015, 15, 2160–2169. [Google Scholar]

- Eke, P.; Adamou, S.; Fokom, R.; Nya, V.D.; Fokou, P.V.T.; Wakam, L.N.; Nwaga, D.; Boyom, F.F. Arbuscular mycorrhizal fungi alter antifungal potential of lemongrass essential oil against Fusarium solani, causing root rot in common bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.). Heliyon 2020, 6, e05737. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Danh, L.T.; Giao, B.T.; Duong, C.T.; Nga, N.T.T.; Tien, D.T.K.; Tuan, N.T.; Huong, B.T.C.; Nhan, T.C.; Trang, D.T.X. Use of essential oils for the control of anthracnose disease caused by Colletotrichum acutatum on post-harvest mangoes of Cat Hoa Loc variety. Membranes 2021, 11, 719. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sukegawa, S.; Shiojiri, K.; Higami, T.; Suzuki, S.; Arimura, G.i. Pest management using mint volatiles to elicit resistance in soy: Mechanism and application potential. Plant J. 2018, 96, 910–920. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rienth, M.; Crovadore, J.; Ghaffari, S.; Lefort, F. Oregano essential oil vapour prevents Plasmopara viticola infection in grapevine (Vitis Vinifera) and primes plant immunity mechanisms. PLoS ONE 2019, 14, e0222854. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kumar, A.; Singh, P.P.; Gupta, V.; Prakash, B. Assessing the antifungal and aflatoxin B(1) inhibitory efficacy of nanoencapsulated antifungal formulation based on combination of Ocimum spp. essential oils. Int. J. Food Microbiol. 2020, 330, 108766. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mączka, W.; Duda-Madej, A.; Górny, A.; Grabarczyk, M.; Wińska, K. Can eucalyptol replace antibiotics? Molecules 2021, 26, 4933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chatterjee, B.; Vittal, R.R. Quorum sensing modulatory and biofilm inhibitory activity of Plectranthus barbatus essential oil: A novel intervention strategy. Arch. Microbiol. 2021, 203, 1767–1778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Monteiro-Neto, V.; de Souza, C.D.; Gonzaga, L.F.; da Silveira, B.C.; Sousa, N.C.; Pontes, J.P.; Santos, D.M.; Martins, W.C.; Pessoa, J.F.; Carvalho Junior, A.R. Cuminaldehyde potentiates the antimicrobial actions of ciprofloxacin against Staphylococcus aureus and Escherichia coli. PLoS ONE 2020, 15, e0232987. [Google Scholar]

- Li, H.; Addo, K.A.; Yu, Y.-g.; Xiao, X.-l. Cuminaldehyde inhibits biofilm formation by affecting the primary adhesion of Staphylococcus aureus. S. Afr. J. Bot. 2023, 156, 13–20. [Google Scholar]

- Ghasemi, G.; Fattahi, M.; Alirezalu, A.; Ghosta, Y. Antioxidant and antifungal activities of a new chemovar of cumin (Cuminum cyminum L.). Food Sci. Biotechnol. 2019, 28, 669–677. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, A.O.; Holley, R.A. Mechanisms of bactericidal action of cinnamaldehyde against Listeria monocytogenes and of eugenol against L. monocytogenes and Lactobacillus sakei. Appl. Environ. Microbiol. 2004, 70, 5750–5755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Pasqua, R.; Hoskins, N.; Betts, G.; Mauriello, G. Changes in membrane fatty acids composition of microbial cells induced by addiction of thymol, carvacrol, limonene, cinnamaldehyde, and eugenol in the growing media. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2006, 54, 2745–2749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Werrie, P.-Y.; Durenne, B.; Delaplace, P.; Fauconnier, M.-L. Phytotoxicity of essential oils: Opportunities and constraints for the development of biopesticides. A review. Foods 2020, 9, 1291. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senatore, F.; Oliviero, F.; Scandolera, E.; Taglialatela-Scafati, O.; Roscigno, G.; Zaccardelli, M.; De Falco, E. Chemical composition, antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of anethole-rich oil from leaves of selected varieties of fennel [Foeniculum vulgare Mill. ssp. vulgare var. azoricum (Mill.) Thell]. Fitoterapia 2013, 90, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, A.; Jeyakumar, E.; Lawrence, R. Strategic approach of multifaceted antibacterial mechanism of limonene traced in Escherichia coli. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 13816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Friedman, M.; Henika, P.R.; Mandrell, R.E. Bactericidal activities of plant essential oils and some of their isolated constituents against Campylobacter jejuni, Escherichia coli, Listeria monocytogenes, and Salmonella enterica. J. Food Prot. 2002, 65, 1545–1560. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coêlho, M.L.; Ferreira, J.H.L.; Júnior, J.P.d.S.; Kaatz, G.W.; Barreto, H.M.; Cavalcante, A.A.d.C.M. Inhibition of the NorA multi-drug transporter by oxygenated monoterpenes. Microb. Pathog. 2016, 99, 173–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Elkiran, O.; Telhuner, O. Chemical Profiles and Antimicrobial Activities of Essential Oil From Different Plant Parts of Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare Mill.). Food Sci. Nutr. 2025, 13, e70307. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Omari, N.; Balahbib, A.; Bakrim, S.; Benali, T.; Ullah, R.; Alotaibi, A.; El Mrabti, H.N.; Goh, B.H.; Ong, S.K.; Ming, L.C.; et al. Fenchone and camphor: Main natural compounds from Lavandula stoechas L., expediting multiple in vitro biological activities. Heliyon 2023, 9, e21222. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Liu, P.; Jia, B.; Xue, S.; Wang, X.; Hu, J.; Al Shoffe, Y.; Gallipoli, L.; Mazzaglia, A.; Balestra, G.M.; et al. Genetic diversity of Pseudomonas syringae pv. actinidiae strains from different geographic regions in China. Phytopathology 2019, 109, 347–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vincent, J.G.; Vincent, H.W.; Morton, J. Filter paper disc modification of the oxford cup penicillin determination. Proc. Soc. Exp. Biol. Med. 1944, 55, 162–164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barros, E.P.; Moreira, N.; Pereira, G.E.; Leite, S.G.F.; Rezende, C.M.; de Pinho, P.G. Development and validation of automatic HS-SPME with a gas chromatography-ion trap/mass spectrometry method for analysis of volatiles in wines. Talanta 2012, 101, 177–186. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).