Abstract

The growing interest in the commercial exploitation of the bioactive components of Dictyota species, including Dictyota kunthii due to its antifungal activity and use in the development of innovative bioproducts, depends on the availability of biomass. In this context, the cultivation of this species emerges as a promising alternative. This study examined thallus fragmentation and ligulae development as methods to produce D. kunthii. Accordingly, thalli were divided into apical, middle, and basal sections to generate the respective tissue fragments, which were cultured under controlled conditions. On the other hand, ligulae development was studied under different conditions of photon flux density (10, 35 and 65 µmol m−2s−1); temperature (10, 17 °C); photoperiod (8:16, 12:12, 16:08 h [Light:Dark]), and seawater enrichment:Basfoliar®, Compo Expert, Krefeld, Germany and von Stosch solutions. The results show that fragmented thalli were non-viable, exhibiting neither wound healing nor regeneration at the cut sites. Furthermore, no buds or new branches were formed. In contrast, ligulae developed under all tested conditions, with nutrients, light, temperature, and photon flux enhancing apical cell formation and branching. We conclude that ligulae can effectively be used as propagules to cultivate fast-growing, branched D. kunthii plantlets. Accordingly, we recommend using a suspended culture system at 17 °C with a 12:12 (Light:Dark) photoperiod and 65 µmol m−2 s−1 light intensity, as well as adding nutrients (Basfoliar® at 0.1 mL L−1). Under these conditions, growth rates equal to or exceeding 10% d−1 can be achieved, supporting the feasibility of scaling up to larger volumes for biomass production.

1. Introduction

Dictyota kunthii is a brown seaweed that grows in both shallow subtidal and intertidal pools across temperate to subtropical zones [1]. It is commonly found in Chile, specifically from Arica to Chiloe, where it forms small, scattered patches [2]. Species of this genus are widely studied due to its active components, including groups such as terpenes, diterpenes, polyunsaturated fatty acids, phenolic compounds, and polysaccharides, which exhibit well-characterized bioactivity, e.g., [3,4,5,6,7,8].

Particularly, the antifungal activity of Dictyota has been addressed by different studies. For example, the methanolic extracts of D. linearis and D. dichotoma [9] showed high activity against the fungi Aspergillus niger, Aspergillus flavus, Candida utilis, Fusarium solani, and Penicillium sp. These findings have also been evidenced in both Dictyota species against phytopathogens and human-pathogenic fungi [10]. Furthermore, nanoparticles obtained at the laboratory scale from D. bartayresiana extracts (from natural grasslands) showed antifungal activity against Humiclo insulans and Fusarium dimerum [11]. Additionally, D. menstrualis bioautography assays indicated antifungal and antioxidant potential of the organic extract and fractions against Cladosporium sphaerospermum [12].

Regarding the antifungal properties of D. kunthii algae extracts, three patents have demonstrated its activity, and it has been utilized in innovative bioproducts such as bioplastics, bioactive papers, bioactive sleeves, and formulations for protecting export fruits [13,14,15]. These products have reduced fruit loss due to oxidation and infection in both laboratory and industrial trials. Thus, D. kunthii extracts inhibited the germination of fungi such as Alternaria alternata, Penicillium spp., and Botrytis cinerea, halting their growth for over 90 days. For instance, foam sleeves reduce B. cinerea infection in apples by 53%, and bioactive papers decrease losses due to infection by B. cinerea and Penicillium spp. by 50 to 70% [13,14]. Additionally, studies have shown the effectiveness of D. kunthii extracts against forest pests such as the eucalyptus weevil and the pine bark beetle, with a repellency of 87% and lethality of 67% for H. ligniperda and 100% lethality for G. platensis [15]. The high bioactivity, chemical complexity, and compounds of Dictyota species have triggered growing market interest, resulting in future potential demand for biomass. Therefore, understanding the lifecycle, reproduction, and preservation of natural Dictyota populations is crucial for formulating strategies for domestication and controlled propagation, e.g., [16].

Species of the order Dictyotales have a diplohaplontic lifecycle with isomorphic, sporophytic, and gametophytic thalli [17]. The lifecycle presents different propagation pathways, which consider both sexual and asexual strategies. Gametophytic (haploid) thalli are dioecious and produce sori of oogonia and antheridia, which release gametes into the environment where they fuse to form a zygote, giving rise to sporophytic (diploid) thalli. These, through meiosis, produce spores in tetrads along the thallus, which after germination reestablish the haploid phase. Additional important asexual pathways contributing to the maintenance of natural populations include thallus fragmentation into re-attachable units [18] and the presence of perennial basal or prostrate structures capable of generating new thalli [19]. In the case of D. kunthii, the presence of ligulae (spatulate protrusions on the thallus surface) provides an additional method of asexual reproduction. Detached ligules are thought to regenerate entire thalli [2,20], although this has not yet been demonstrated. For many algae species, the alternation of generations is balanced, with sexual and asexual reproduction occurring at similar intensities [21]. However, Dictyota species are an exception: in several species within the Dictyotales order, the presence of fertile gametophytes has been reported as rare or completely absent [22,23,24]. This is consistent with the description by [25] of D. kunthii along the central Chilean coast, where only sporophytic and infertile thalli were observed throughout an annual cycle. This implies that, in many cases, the persistence of Dictyota populations depends on asexual reproduction, where reproduction via spores would be one of the most important propagation strategies in alternation with thallus fragmentation and subsequent reattachment [26].

Optimal macroalgal cultivation depends on the balance of nutrient availability and physical factors, which together regulate growth, morphogenesis, and reproduction under confined conditions. In seaweed culture systems, parameters such as light intensity, photoperiod, temperature, and seawater nutrient composition strongly influence metabolic activity and cellular differentiation [27,28,29,30,31]. Adequate nutrient supply, particularly nitrogen, phosphorus, and trace elements, supports protein synthesis, pigment formation, and tissue regeneration, while deficiencies can rapidly lead to growth inhibition or thallus decay [32,33]. Moreover, hydrodynamic conditions and aeration play critical roles by enhancing CO2 diffusion and nutrient uptake, thereby sustaining photosynthetic efficiency and structural integrity [28]. The evaluation of these abiotic variables under controlled laboratory conditions provides a basis for identifying optimal combinations that promote sustained growth. Thus, understanding such physiological responses is essential for defining suitable cultivation strategies for Dictyota kunthii.

Both spores and fragmentation could serve as potential methods for the domestication and cultivation of certain species, thereby bypassing the more complex process of sexual reproduction. Indeed, sexual reproduction requires finding male and female individuals and involves several complicated steps such as settlement, germination and growth of the new individuals, often requiring controlled laboratory conditions [21]. Propagation via spores or fragmentation remains untested in this genus, and spore-based approaches are notably delicate and labor-intensive, especially for generating biomass at scales suitable for bioactive compound extraction. Although there are no commercial cultures of Dictyota spp., there are instances where both spores [20,25,34] and thallus fragments [16] have been successfully cultured in the laboratory [35]. These studies demonstrate the ability of Dictyota species to grow and reproduce under confined conditions, albeit limited to the laboratory scale. For D. dichotoma [34], the plants remained healthy and retained their typical morphology, and many clones could be obtained by asexual reproduction through spore culturing. Similarly, fragmentation appears to be a powerful strategy for productive Dictyota cultivation. Research by [36] demonstrated that Dictyota dichotoma thalli can be broken into different pieces, which regenerate and regrow after wounding. In this context, the literature suggests that D. kunthii culture could be initiated using fragments or ligulae through standard algal culture methods. However, further research is needed to determine which strategy can be scaled up for biomass production. Accordingly, this study aimed to evaluate the vegetative propagation of D. kunthii via fragmentation and the growth of ligulae under controlled laboratory conditions. The results are expected to contribute significantly to enabling large-scale biomass production.

2. Results

2.1. Thalli Fragmentation and Ligulae

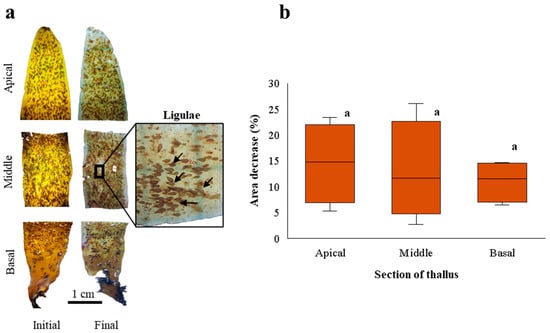

After 21 days of culture, the fragments of the apical, middle, and basal sections of D. kunthii thalli showed losses of coloration, turgor, and, in some cases, tissue loss, demonstrating a deterioration with respect to the initial condition (Figure 1a). No evidence of regeneration or bud formation was observed at the cut sites or elsewhere on the thallus. However, for all fragments, surface ligulae were abundant and exhibited natural coloration without tissue loss or evident deterioration (Figure 1a). GR was negative for the different sections of the thallus: −1.2 ± 0.6; −1.2 ± 1; and −0.8 ± 0.3% d−1 for the apical, middle, and basal fragments, respectively. A decrease in area was also recorded for the apical (15 ± 7.8%), middle (13 ± 9.7%), and basal (11 ± 4.1%) fragments (Figure 1b), although without statistical differences (F = 0.218; p > 0.05).

Figure 1.

(a). Apical, middle, and basal fragments of D. kunthii thalli at the beginning (initial) and end (final) of the experimental period. The inset shows abundant ligulae (indicated by black arrows) on the thallus. (b). Area decrease (%) of apical, middle, and basal fragments of D. kunthii thalli cultivated under controlled laboratory conditions for 21 days. Letters above the bars indicate statistical differences (p < 0.05). Values shown as the median ± d 90% quartiles, n = 4 per treatment.

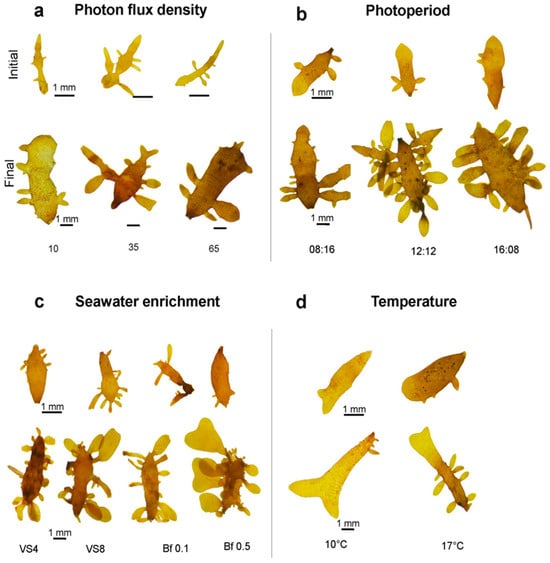

The ligulae developed and grew under all treatments, in some cases forming highly branched thalli by the end of the experimental period. The formation of reproductive structures in the ligulae (tetraspores) was not observed for any treatment.

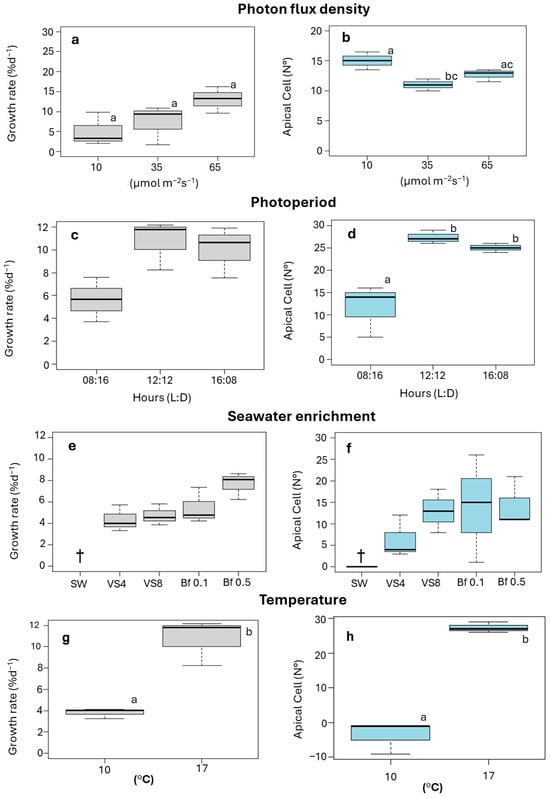

2.2. Effect of Photon Lux Density (PFD)

An increase in ligulae growth was observed with increasing PFD (Figure 2a). Growth was lowest at 10 µmol m−2 s−1, with a GR of 2 ± 0.2% d−1. The highest GR was achieved at 65 µmol m−2 s−1, with a value of 15 ± 0.2% d−1 (Figure 2a). However, these differences were not significant (F = 2.869; p > 0.05). The number of apical cells produced by the ligulae was significantly influenced by PFD (F = 2.659; p < 0.05), the highest apical cell count (15 ± 4) was observed at 10 µmol m−2 s−1, while the lowest (7 ± 2) occurred at 35 µmol m−2 s−1 (Figure 2b). At the end of the culture period under 10 µmol m−2 s−1, the ligulae exhibited a loss of coloration and turgor (Figure 3a).

Figure 2.

Growth rate (GR, % d−1) and number of apical cells of ligulae cultivated under selected abiotic factors. (a,b). photon flux density; 10, 35, and 65 µmol m−2s−1. (c,d). photoperiod; 08:16, 12:12, and 16:08 h (Light:Dark). (e,f). seawater enrichment; SW (seawater), VS4 (von Stosch 4 mL L−1), VS8 (von Stoch 8 mL L−1), Bf 0.1 (Basfoliar® 0.1 mL L−1), and Bf 0.5 (Basfoliar® 0.5 mL L−1). (g,h). temperature, 10 and 17 °C. Letters above the bars indicate statistical differences (p < 0.05). Values shown as the median ± 90% quartiles, n = 3 per treatment. †: total mortality of ligulae biomass.

Figure 3.

Representative images of the external morphological changes in ligulae cultivated for 21 days under different abiotic factors: (a). photon flux density; 10, 35, and 65 µmol m−2s−1. (b). photoperiod; 08:16, 12:12, and 16:08 h (Light:Dark). (c). seawater enrichment; VS4 (von Stosch 4 mL L−1), VS8 (von Stoch 8 mL L−1), Bf 0.1 (Basfoliar® 0.1 mL L−1), and Bf 0.5 (Basfoliar® 0.5 mL L−1). (d). temperature, 10 and 17 °C.

2.3. Effect of Photoperiod

Ligulae cultivated under different photoperiod treatments showed a similar variation for both GR and production of apical cells, with the lowest values of both variables recorded at 08:16 h (Light:Dark) (Figure 2c,d). The highest GR was obtained with increasing light hours, reaching a GR of 12 ± 0.1% d−1 at 12:12 h (Light:Dark) (Figure 2c). However, no statistical differences between treatments were recorded (F = 5.0862; p > 0.05). The different photoperiod treatments did show significant differences in the number of apical cells produced (F = 17.07; p < 0.05). The highest number (27 ± 1.5 cells) was reached in the 12:12 h (Light:Dark) treatment, while the lowest value (12 ± 6.4 cells) was observed in the 8:16 h (Light:Dark) treatment (Figure 2d). At the end of the experimental period, a higher number of apical cells were produced in the treatments at 12:12 h (Light:Dark), resulting in ligulae with abundant branching (Figure 3b).

2.4. Effect of Seawater Enrichment

The ligulae exhibited greater growth and development when cultured in enriched seawater (Figure 2e,f). Conversely, ligulae cultured in seawater without nutrient supplementation exhibited progressive decay, ultimately resulting in total mortality by the end of the experimental period (Figure 2e,f). The GR varied from 4 ± 0.03 to 8 ± 0.04% d−1 for the von Stosch (4 mL L−1) and Basfoliar® (0.5 mL L−1) treatments, respectively (Figure 2e). Although the growth was higher with Basfoliar® enrichment, no significant differences were observed between treatments (F = 3.755; p > 0.05).

The formation of apical cells was favored in the treatments with Basfoliar® (Figure 2f), reaching a maximum value of 14 ± 12 cells with Basfoliar® 0.1 mL L−1. The von Stosch treatment (4 mL L−1) recorded the lowest production of apical cells (5 ± 4 apical cells; Figure 2f). However, these differences were not statistically significant (F = 0.733; p > 0.05). At the end of the experimental period, the ligulae exhibited abundant dichotomous branching (Figure 3c).

2.5. Effects of Temperature

A GR of 11 ± 0.1% d−1 was reached at 17 °C, but at 10 °C was significantly lower (4 ± 0.01% d−1) (T-Student, p = 0.0038) (Figure 2g). The production of apical cells varied significantly between treatments at 17 °C and 10 °C (T-Student, p = 0.0265) (Figure 2h). The 17 °C treatment was more favorable, resulting in 27 ± 2 apical cells, while the 10 °C treatment caused a loss of these cells. Despite the temperature differences, the ligulae remained healthy in both treatments, showing typical coloration and numerous small branches (Figure 3d).

3. Discussion

Dictyota spp. exhibit substantial phytochemical diversity, containing many biocomponents with applications in high-value sectors, such as pharmaceuticals, nutraceuticals, and cosmetics [37,38]. Additionally, D. kunthii has recently been reported to exhibit antifungal properties and potential for application in forest pest control [13,14,15]. The extraction of these biocomponents requires high-quality biomass; thus, cultivation is a proposed alternative to the uncertain supply of natural populations. Nevertheless, the methods and conditions that facilitate Dictyota productive cultivation have been scarcely investigated [16], and, due to the characteristics of the Dictyota thallus, few studies suggest that vegetative fragmentation could be a viable alternative for suspended culturing [5,16,35], with no commercial cultures reported in the literature. The present results indicate that cultivation of D. kunthii via thallus fragments is not advisable. However, the presence of ligulae on the thallus surface appears to represent a viable alternative for propagation.

Unlike previous reports on other Dictyota species [18,29], the results presented here indicate that Dictyota kunthii thalli do not produce viable fragments. Tanaka et al. [36] showed that various parts of the D. dichotoma thallus can recover after fragmentation, with the ability to maintain apical growth, regenerate branches, or form rhizoids, actively responding to wound stress. These characteristics promote the formation of thallus fragments, which have been identified as one of the main strategies for propagating and maintaining natural populations in several Dictyota species [16,18,39]. However, for D. kunthii, the cut sections of the thallus did not exhibit wound healing, thallus regeneration, buds, or new branches, instead evidencing turgor loss and discoloration. In this regard, Malbrán and Hoffmann [25] observed that asexual strategies, such as spores and perennial basal disks, are the most reliable mechanisms for maintaining D. kunthii populations in central Chile, over thallus fragmentation.

Additionally, ligulae have been proposed as an additional strategy for propagating D. kunthii [20,25], although this has not yet been documented in situ, as the reattachment and subsequent development of ligulae in adult thalli remain unconfirmed. However, our results add evidence supporting this idea as; (i) ligulae persisted despite the disintegration of fragmented thalli, (ii) grew actively in different culture conditions, and (iii) produced branched thalli like the parents. Taken together, these findings indicate that ligulae, as propagules, can be expected to prevail over thallus fragmentation and develop new thalli, although ligulae reattachment mechanisms must be clarified.

The present study showed that ligulae growth is actively influenced by abiotic factors such as PFD, temperature (17 °C), and photoperiod, which aligns with descriptions by Hoffmann [27] and Hoffmann & Malbrán [20]. However, the current findings further indicate that development can also be stimulated by nutrient-enriched cultures. This is consistent with reports for several Dictyota species that can rapidly and efficiently uptake available nutrients [37]. In the present study, ligulae grew in all experimental treatments, actively forming apical cells. By contrast, the seawater control treatment led to complete mortality of the ligulae. Consistent with these findings, the nutrient addition to accelerating biomass production is common and necessary in confined cultures without permanent seawater flow [32,33], especially in seedling or propagule production [40]. Nonetheless, nutrients can be very costly to apply. Therefore, the use of small amounts of fertilizer solutions or biostimulants, such as Basfoliar®, has become a productive option, especially in closed cultures. Both are increasingly being used in species of commercial interest, such as Macrocystis pyrifera and Gracilaria chilensis, being cost-effective and having excellent production results [30,41,42]. These outcomes are particularly notable when compared to traditional solutions for seawater enrichment in algal cultures, such as use of the von Stosch medium [30]. The present results showed that the addition of enrichment solutions (e.g., Basfoliar®, from 0.1 mL L−1) not only increased growth, but induced secondary development of the ligulae, promoting the formation of plantlets with abundant branching, which facilitates later cultivation stages. In this regard, we have recently observed that unbranched ligulae are unable to float and precipitate. This makes suspended culture in hatchery tanks (>300 L) and contributes to increased mortality (unpublished data).

Hoffmann [27] and Hoffmann and Malbrán [20] demonstrated a close association between temperature, photoperiod, and PFD with fertile ligulae (i.e., tetraspore formation). In contrast, the present study did not observe tetraspores on the ligulae in any of the experimental treatments, even under short-day conditions, which [27] mentioned as a trigger for tetrasporogenesis. Furthermore, in vitro tetraspore production has been documented to coincide with low ligulae development [20], suggesting that both processes are differentially stimulated by abiotic factors. This is advantageous for scaling ligulae-based cultivation since investing energy in growth and avoiding senescence after reproduction is desirable [43]. The absence of reproductive structures could be due to the permanent aeration used in this study, which would favor thallus growth. In fact, moderate water motion or aeration enhances boundary-layer thinning, improving the delivery of dissolved inorganic carbon and nutrients to the algal surface, which in turn favors rapid thallus growth [44]. In this sense, prior research proposes that hydrodynamic conditions may favor growth by improving CO2 availability and nutrient uptake [28,29,32]. Therefore, the permanent aeration in the present study may have created conditions that favored sustained growth and branching at the expense of tetrasporogenesis. Nevertheless, this hypothesis warrants further investigation, particularly through experiments that compare static versus aerated conditions to determine the specific hydrodynamic thresholds influencing reproductive induction in D. kunthii.

4. Materials and Methods

Thalli of D. kunthii were collected manually, ensuring complete removal of each individual. from Algarrobo Bay (33°21′53.79″ S 71°40′46.30″ W) Valparaíso Region, central Chile, during autumn 2023. The site was chosen based on the natural abundance of thalli in the mid- to low-intertidal zones along the central Chilean coast [25]. The thalli were transported wet to the laboratory in hermetic bags kept at 10 °C. Once in the laboratory, we selected healthy thalli that displayed adequate coloration and free of epibionts visible to the naked eye. Additionally, the basal attachment disk was excised from each alga, as these parts typically contain sand and epibiotic organisms. Subsequently, the biomass was thoroughly rinsed with freshwater to remove sediment, associated macroalgae, and invertebrates, followed by rinsing with filtered seawater (1 µm) and a 9% iodine solution. Subsequently, 30 thalli were selected and maintained in an aquarium with 10 L of filtered (1 µm) seawater (32 PSU) enriched with the von Stosch [45] seawater medium solution (8 mL L−1), for 20 days to acclimatize the thalli to laboratory conditions and ensure that they remain healthy for the start of experiments. The aquariums were kept at 17 ± 1 °C, with bubbling aeration, a 12:12 h photoperiod (Light:Dark), a photon flux density (PFD) of 40 µmol m−2 s−1, and weekly seawater renewal. All experiments detailed below were conducted using this biological material.

4.1. Thallus Fragmentation: Growth and Regeneration

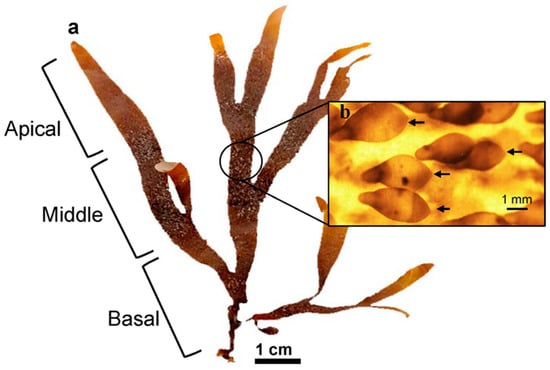

Thalli were cut into three sections along the algal body, producing apical fragments (up to 3 cm below the apex), basal fragments (3 cm from the base), and middle fragments (Figure 4a). Four 500 mL Erlenmeyer flasks were used for each type of fragment, with three pieces arranged in each flask independently (0.1 g L−1). Fragments were maintained for 21 days under the specified conditions, with weekly medium renewal. All fragments were observed using a Motic SMZ-140 stereo microscope, and the photographs were processed using the ImageJ software v1.53. The area of each fragment was measured at the beginning and end of the culture period. The growth rate (GR) was calculated using the formula proposed by [46]: GR (%d−1) = [[(Ai/Af)1/t − 1] × 100], where Ai = initial area and Af = final area after t days. Changes in area during the experimental period were expressed as a percentage relative to the initial area. Thallus regeneration was also assessed by observing the fragments under a Motic SMZ-140 stereoscopic microscope (Motic Instruments, Speed Fair Co., Ltd., Universal City, TX, USA). The number of fragments that developed shoots and the total number of shoots per treatment (i.e., apical, middle, and basal fragments) were recorded. Regeneration was expressed as a percentage (%) of the total number of fragments that produced shoots.

Figure 4.

(a). Thallus of D. kunthii indicating the apical, middle, and basal sections used to obtain fragments. (b). Detail of unbranched ligulae (black arrows) with a single apical cell.

4.2. Ligulae: Growth and Development

Thalli with abundant ligulae were selected, ensuring that only small ligulae (i.e., 1–4 mm in length) without visible branching, containing only one or a few apical cells were chosen (Figure 4b). The ligulae were separated from the thalli using a scalpel by gently scraping the surface. Then, the mass obtained was washed with abundant filtered seawater (1 µm). Prior to the experiments, ligulae were incubated in a 4 L seawater container under the previously described conditions for 10 days to allow the identification and removal of mechanically damaged individuals. A single-factor experiment (Table 1) was performed to evaluate the influence of PFD, photoperiod, seawater enrichment (von Stoch solution and Basfoliar®, according to [30]) (Table 2), and temperature on the growth and the number of the apical cells for D. kunthii ligulae. Each experiment was carried out for 21 days (We defined a cultivation period of less than one month, as we want to find efficient cultivation conditions to accelerate the seedling or plantlet production stages, since extended periods of cultivation under controlled conditions tend to be costly). For this purpose, 500 mL Erlenmeyer flasks were filled with filtered seawater (1 µm) and maintained under the conditions detailed in Table 1, in a suspended-culture system. For each treatment, three Erlenmeyer were used, into which 0.1 g of ligulae (fresh weight ~ 70–100 ligulae) were added. Seawater and the culture medium were renewed weekly.

Table 1.

Summary of factors and levels used to evaluate the growth of D. kunthii ligulae and apical cell formation under controlled conditions. Aeration was added in all treatments.

Table 2.

Composition of the culture media used. Modified from [30].

At the beginning and end of each experiment, the wet weight of the ligulae was measured using an analytical balance (Boeco Bas 31 plus), and the GR (% d−1) was calculated using the previously described formula. The number of initial and final apical cells after 21 days of culture was determined by observing and counting 15 randomly selected ligulae in each experiment, using a stereoscopic microscope (Motic SMZ-140). Additionally, the surface of the ligules was examined during each measurement to detect spore formation (tetrasporangia).

4.3. Data Analysis

Normality was assessed with a Shapiro-Wilk test and homoscedasticity with Bartlett’s test. To determine differences in growth and survival among thalli sections (i.e., apical, middle, and basal) an ANOVA test (one-way) was conducted, followed by the Tukey test when necessary. On the other hand, a one-way ANOVA was performed to evaluate the effects of PFD, photoperiod, and the seawater-enrichment solution on the variables of GR and number of apical cells. Post hoc Tukey tests were performed to assess treatments showing significant differences. For temperature comparisons between treatments were performed using Student’s t-test.

5. Conclusions

Algae cultivation is usually carried out in multi-step systems considering production from seed to harvest [40]. The present study demonstrated that ligulae can be used as propagules for the cultivation of D. kunthii since they grow actively under different conditions, rapidly modifying in shape and forming plantlets with abundant branching (21 days). This is an advantage, as extensive plantlet production stages can be very costly, making the entire process inefficient. To accelerate the ligulae-to-propagule transition and to ultimately obtain a plantlet-like adult thallus able to develop and produce biomass, we recommend a suspended culture system (permanent aeration) with a temperature of 17 °C, a 12:12 Light:Dark, a PFD of 65 µmol m−2s−1, and nutrient addition (Basfoliar® (0.1 mL L−1)). According to this study, growth rates ≥ 10% d−1 could be achieved under these conditions, meaning that ligulae could double in size in a few days, facilitating potential scaling up to larger volumes for producing biomass.

Author Contributions

C.B., conceptualization, supervision, and writing—review & editing. L.C.-P., supervision and writing—review & editing. J.P.R., supervision and conceptualization. C.M., methodology, investigation, and writing—original draft. K.G., methodology and investigation. N.G., investigation, software, and writing—original draft. C.A. and C.R., writing—review & editing. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by ANID—Subdirección de Investigación Aplicada—Grantt: FONDEF ID21I10057.

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the support from CIMARQ (Center for Marine Research), where the cultivation of D. kunthii was carried out. L.C.-P. acknowledges support from ANID—Millennium Science Initiative Program—ICN2019_015 ICM-ANID and ANID PIA/BASAL AFB240003.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Guiry, M.D.; Guiry, G.M. AlgaeBase. World-Wide Electronic Publication, University of Galway. 2025. Available online: https://www.algaebase.org (accessed on 31 March 2025).

- Ramírez, M.; Bulboa, C.; Contreras, L.; Mora, A. Flora Marina Bentónica de Quintay; Ril Editores: Santiago, Chile, 2025; p. 244. ISBN 978-956-01-0536-3. [Google Scholar]

- Gupta, S.; Abu-Ghannam, N. Bioactive potential and possible health effects of edible brown seaweeds. Trends Food Sci. Technol. 2011, 22, 315–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pereira, H.; Barreira, L.; Figueiredo, F.; Custódio, L.; Vizetto-Duarte, C.; Polo, C.; Rešek, E.; Engelen, A.; Varela, J. Polyunsaturated fatty acids of marine macroalgae: Potential for nutritional and pharmaceutical applications. Mar. Drugs 2012, 10, 1920–1935. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martins, A.P.; Yokoya, N.S.; Colepicolo, P. Biochemical modulation by carbon and nitrogen addition in cultures of Dictyota menstrualis (Dictyotales, Phaeophyceae) to generate oil-based bioproducts. Mar. Biotechnol. 2016, 18, 314–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, J.; Li, H.; Zhao, Z.; Xia, X.; Li, B.; Zhang, J.; Yan, X. Diterpenes from the marine algae of the genus Dictyota. Mar. Drugs 2016, 16, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cirne-Santos, C.; Barros, C.; Gomez, M.; Gomes, R.; Cavalcanti, D.; Obando, J.; Ramos, C.; Villaca, R.; Teixeira, V.; Paixao, I. In vitro antiviral activity against Zika virus from a natural product of the Brazilian brown seaweed Dictyota menstrualis. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2019, 14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dixit, D.; Reddy, C.; Trivedi, M.; Gadhavi, D. Non-targeted metabolomics approach to assess the brown marine macroalga Dictyota dichotoma as a functional food using liquid chromatography with mass spectrometry. Sep. Sci. Plus 2020, 3, 140–149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Soliman, E.; Ali, E.; Masoud, G.; Mohamed, B.; El-Moneim, S. Antifungal activities of methanolic extracts of some marine algae (Ulvaceae and Dictyotaceae) of Benghazi coasts, Libya. Egypt. J. Exp. Biol. 2013, 9, 75–79. [Google Scholar]

- Moreau, J.; Pesando, D.; Bernard, P.; Caram, B.; Pionnat, J. Seasonal variations in the production of antifungal substances by some dictyotales (brown algae) from the french mediterranean coast. Hydrobiologia 1988, 162, 157–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, P.; Sudha, S. Biosynthesis of silver nanoparticles from Dictyota bartayresiana extract and their antifungal activity. Nano Biomed. Eng. 2013, 5, 72–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- dos Santos, T.; Obando, J.; Martins, R.; Alves, M.; Villaça, R.; Machado, L.; Gasparoto, M.; Cavalcanti, D. Perfil químico por CLUE-EMAR e atividade antifúngica e antioxidante da macroalga marinha Dictyota menstrualis. Rev. Virtual Quim. 2024, 16, 30–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Agurto, C.; Troncoso, N.; Teixeira, R.; Pereira, M.; Valdebenito, A.; San Martin, S.; Farias, J. Papel Bioactivo Que Comprende Como Base un Papel Algal. Chile Patent 2020/60897, 5 November 2020. [Google Scholar]

- Agurto, C.; Troncoso, N.; Teixeira, R.; Pereira, M.; Valdebenito, A.; San Martin, S.; Farias, J. Papel Bioativo, Processo de Elaboração e uso Para Proteção de Frutas e Legumes. Brazil Patent 2023/112019001673-2, 13 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Le Feuvre, R.; Latorre, M.; Valdebenito, A.; Landahur, C.; Arriagada, D.; Agurto, C.; Moraga, P.; Sanfuentes, E. Uso de un Bioproducto a Base a Extracto de Dictyota kunthii Para Repeler el Escarabajo de Corteza Hylurgus ligniperda Presente en Madera aserrada de Pinus radiata. Chile Patent 2022/65425, 15 September 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Bogaert, K.; Beeckman, T.; De Clerck, O. Abiotic regulation of growth and fertility in the sporophyte of Dictyota dichotoma (Hudson) J.V. Lamouroux (Dictyotales, Phaeophyceae). J. Appl. Phycol. 2016, 28, 2915–2924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Van den Hoek, C.; Mann, D.; Jahns, H. Algae: An Introduction to Phycology; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 1995; p. 627. ISBN 0521304199. [Google Scholar]

- Herren, L.; Walters, L.; Beach, K. Fragment generation, survival, and attachment of Dictyota spp. at Conch Reef in the Florida Keys, USA. Coral Reefs 2006, 25, 287–295. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richardson, J. Overwintering of Dictyota dichotoma (Phaeophyceae) near its northern distribution limit on the east coast of North America. J. Phycol. 1979, 15, 22–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, A.; Malbrán, M. Temperature, photoperiod and light interaction on growth and fertility of Glossophora kunthii (Phaeophyta, Dictyotales) from central Chile. J. Phycol. 1989, 25, 129–133. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bellorín, A.; Bulboa, C.; Contreras-Porcia, L. Algas, Una Introducción a la Ficología; Ril Editores: Santiago, Chile, 2022; p. 696. ISBN 978-956-01-0899-9. [Google Scholar]

- Phillips, J.; Clayton, M.; Harvey, A. Comparative studies on sporangial distribution and structure in species of Zonaria lobophora and Homoeostrichus (Dictyotales, Phaeophyceae) from Australia. Eur. J. Phycol. 1994, 29, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.; Nelson, W. Typification of the Australasian brown alga Zonaria turneriana J. Agardh (Dictyotales) and description of the endemic New Zealand species, Zonaria aureomarginata sp. nov. Bot. Mar. 1998, 41, 77–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Phillips, J.; Clayton, M. Comparative studies on gametangial distribution and structure in species of Zonaria and Homoeostrichus (Dictyotales, Phaeophyceae) from Australia. Eur. J. Phycol. 2010, 32, 25–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Malbrán, M.; Hoffmann, A. Seasonal cycles of growth and tetraspore formation in Glossophora kunthii (Phaeophyta, Dictyotales) from Pacific South America: Field and laboratory studies. Bot. Mar. 1990, 33, 219–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ateweberhan, M.; Bruggemann, H.; Breeman, A. Seasonal patterns of biomass, growth and reproduction in Dictyota cervicornis and Stoechospermum polypodioides (Dictyotales, Phaeophyta) on a shallow reef flat in the southern Red Sea (Eritrea). Bot. Mar. 2005, 48, 8–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hoffmann, A. Daylength and light responses in growth and fertility of Glossophora kunthii (Phaeophyta, Dictyotales) from Pacific South America. J. Phycol. 1988, 24, 203–208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hurd, C. Water motion, marine macroalgal physiology, and production. J. Phycol. 2000, 36, 453–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Harrison, P.; Hurd, C. Nutrient physiology of seaweeds: Application of concepts to aquaculture. Cah. Biol. Mar. 2001, 42, 71–82. [Google Scholar]

- Rivas, J.; Núñez, A.; Piña, F.; Erazo, F.; Castañeda, F.; Araya, M.; Meynard, A.; Contreras, L. Indoor culture scaling of Gracilaria chilensis (Florideophyceae, Rhodophyta): The effects of nutrients by means of different culture media. Rev. Biol. Mar. Oceanogr. 2021, 56, 186–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Piña, F.; Núñez, A.; Araya, M.; Rivas, J.; Hernández, C.; Bulboa, C.; Contreras-Porcia, L. Controlled cultivation of different stages of Pyropia orbicularis (Rhodophyta; Bangiales) from the South Pacific coast. Aquac. Rep. 2023, 30, 101594. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roleda, M.; Hurd, C. Seaweed nutrient physiology: Application of concepts to aquaculture and bioremediation. Phycologia 2019, 58, 552–562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suthar, P.; Gajaria, T.; Reddy, C. Production of quality seaweed biomass through nutrient optimization for sustainable land-based cultivation. Algal. Res. 2019, 42, 101583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hwang, I.; Kim, H.; Lee, W. Polymorphism in the brown alga Dictyota dichotoma (Dictyotales, Phaeophyceae) from Korea. Mar. Biol. 2005, 147, 999–1015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paternostro, A. Evaluation on Biotechnological Potential of Marine Macroalgae. Ph.D. Thesis, Universidade de Sao Paulo, Sao Paulo, Brasil, 2013; p. 188. [Google Scholar]

- Tanaka, A.; Hoshino, Y.; Nagasato, C.; Motomura, T. Branch regeneration induced by severe damage in the brown alga Dictyota dichotoma (Dictyotales, Phaeophyceae). Protoplasma 2017, 254, 1341–1351. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bogaert, K.; Delva, S.; De Clerck, O. Concise review of the genus Dictyota JV Lamouroux. J. Appl. Phycol. 2020, 32, 1521–1543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rushdi, M.; Abdel-Rahman, I.; Attia, E.; Saber, H.; Saber, A.; Bringmann, G.; Abdelmohsen, U. The biodiversity of the genus Dictyota: Phytochemical and pharmacological natural products prospectives. Molecules 2022, 27, 672. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gauna, M.; Cáceres, E.; Parodi, E. Temporal variations of vegetative features, sex ratios and reproductive phenology in a Dictyota dichotoma (Dictyotales, Phaeophyceae) population of Argentina. Helgol. Mar. Res. 2013, 67, 721–732. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiksing, C.; Ongkudon, M.; Thien, V.; Rodrigues, K.; Yong, W.; McMarshall, M. Recent advances in seaweed seedling production: A review of eucheumatoids and other valuable seaweeds. Algae 2022, 37, 105–121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Camus, C.; Infante, J.; Buschmann, A. Overview of 3-year precommercial seafarming of Macrocystis pyrifera along the Chilean coast. Rev. Aquac. 2018, 10, 543–559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caroca-Valencia, S.; Rivas, J.; Araya, M.; Núñez, A.; Piña, F.; Toro-Mellado, F.; Contreras-Porcia, L. Indoor and outdoor cultures of Gracilaria chilensis: Determination of biomass growth and molecular markers for biomass quality evaluation. Plants 2023, 12, 1340. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santelices, B. Patterns of reproduction, dispersal and recruitment in seaweeds. Oceanogr. Mar. Biol. Ann. Rev. 1990, 28, 177–276. [Google Scholar]

- Stewart, H.; Carpenter, R. The effects of morphology and water flow on photosynthesis of marine macroalgae. Ecology 2003, 84, 2999–3012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- von Stosch, H. Wirkung von Jod und Arsenit auf Meeresalgen in Kultur. Proc. Int. Seaweed Symp. 1964, 4, 142–150. [Google Scholar]

- Yong, Y.; Yong, W.; Anton, A. Analysis of formulae for determination of seaweed growth rate. J. Appl. Phycol. 2013, 25, 1831–1834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).