Abstract

DnaJ proteins are established regulators of multiple physiological processes in plants, but their systematic identification and functional characterization in cotton remains largely uncharacterized, particularly regarding their roles in floral developmental regulation. In this study, based on genome-wide analysis of Gossypium hirsutum L., 372 DnaJ genes were systematically identified and phylogenetically classified into four distinct clades (I–IV). These genes exhibited non-uniform chromosomal distribution. Structural analysis revealed clade-specific variations in intron numbers and conserved motifs. Cis-acting element profiling indicated the roles of DnaJs in modulating biosynthetic and metabolic regulation during both vegetative and reproductive development in cotton. Transcriptomic analysis highlighted tissue-specific expression patterns, with GhDnaJ316 showing preferential expression in anthers and filaments. Functional validation via VIGS-mediated silencing confirmed GhDnaJ316 as a negative regulator of floral transition, accelerating budding by 7.7 days and flowering by 9.7 days in silenced plants. This study elucidates the genomic architecture of GhDnaJs, demonstrates GhDnaJ316’s critical role in floral development and provides insights for molecular breeding in early-maturing cotton.

1. Introduction

DnaJ proteins, also referred to as J-proteins, constitute the conserved family of co-chaperones characterized by the presence of a highly conserved J-domain. DnaJ protein was ubiquitously distributed across eukaryotes, initially identified as the 41 kDa heat shock protein in the study on Escherichia coli heat shock response mechanism [1]. DnaJ proteins exhibit remarkable diversity in both quantity and structural organization. Based on domain architecture, they were historically classified into three categories, i.e., Type I, II, and III. Type I consisted of four domains including the J-domain, a zinc finger domain, a glycine/phenylalanine-rich region (G/F domain), and a less conserved C-terminal domain. Type II harbored the J-domain and G/F domain without zinc finger domain. Type III was the most minimalistic, consisting solely of the J-domain [2,3,4,5]. Recently, Type IV DnaJs have been identified as a new category characterized by a domain structurally analogous to the J-domain but lacking the complete signature His, Pro and Asp (HPD) tripeptide motifs [6].

Accumulating evidence indicates that DnaJ proteins, functioning as molecular co-chaperones of Hsp70 systems, orchestrate diverse physiological processes including seed germination, chloroplast biogenesis, photosynthetic efficiency, protein trafficking, anther morphogenesis, flowering time control, seed maturation, and abiotic stress response [7,8,9,10]. For instance, Vitha et al. demonstrated in Arabidopsis thaliana that loss-of-function mutations in the plastid-localized J-protein ARC6 disrupt the formation of the chloroplast division machinery, resulting in severely impaired plastid fission due to defective Z-ring assembly at the mid-plastid site [11]. Studies have revealed that mutations in chloroplast-localized J-proteins J8, J11, and J20 in A. thaliana significantly impair photosynthetic enzyme activity and destabilize the assembly of the photosystem II (PSII) complex, demonstrating their critical roles in regulating photosynthetic efficiency [12,13,14,15]. Furthermore, mitochondria-localized DnaJ proteins were found to recruit Hsp70 chaperones to the inner membrane through direct protein–protein interactions, thereby mediating the translocation of cytosolic polypeptides into the mitochondrial matrix [8].

DnaJ genes have been identified as key regulators in floral organ development and flowering time modulation in model plants [16,17]. For example, the J-protein ERdj3B maintains its chaperone function under heat stress to promote anther development in A. thaliana by facilitating the assembly of the SDF2-ERdj3B-BiP complex, which ensures proper protein folding in reproductive tissues [18]. Furthermore, AtJ1 accelerates flowering initiation through negative regulation of ABA signaling pathways [19]. Yang et al. demonstrated that CbuDnaJ49 modulates leaf pigmentation in Catalpa bungei by regulating anthocyanin biosynthesis and chloroplast development [20]. The DnaJ gene family was also found to participate in plant responses to heat, drought and salinity stresses through distinct molecular mechanisms [21,22]. In Arabidopsis thaliana, AtDjB1 acts as a negative regulator of drought stress adaptation by suppressing ABA-mediated stomatal closure and root architecture remodeling, thereby exacerbating water loss under dehydration conditions [23]. Conversely, in Oryza sativa, the nuclear-localized OsDnaJ15 chaperone enhances salt tolerance by forming a complex with OsBAG4; the maintenance of this ion homeostasis maintains the efficiency of both photochemical reactions and carbon fixation during photosynthesis, enabling sustained photosynthetic capacity under saline stress [24]. Nevertheless, the regulatory functions of the DnaJ protein family in floral transition, particularly in economically important crops, have not been extensively investigated.

Cotton serves as a fundamental pillar of agricultural economy worldwide and a critical strategic resource, with upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.) accounting for 95% of global production and representing the dominant cultivar in cotton breeding [25,26]. The development of sequencing technologies and multi-omics research have progressively elucidated genes regulating growth and development in Gossypium species [27,28,29]. For instance, integrated RTM-GWAS and meta-QTL analyses identified two genomic regions significantly associated with the node of the first fruiting branch (FFBN) and its height (HFFBN), pinpointing candidate genes GhE6, GhDRM1, and GhGES. Subsequent VIGS validation confirmed the regulation of GhE6 in modulating HFFBN, while GhDRM1 and GhGES were linked to early flowering [30]. Wang et al. (2023) [31] revealed that GhAP1-D3 positively regulates flowering time and early maturity, overexpression assays revealed that this gene significantly accelerates flowering and shortens the maturation period without compromising yield or fiber quality. Furthermore, studies on the transcription factor GhNST1 indicate its upregulated expression under drought stress, and VIGS-based silencing of the gene reduced relative water content, increased wilting rates, diminished antioxidant enzyme activity, and delayed bud emergence, flowering, and boll opening. Concurrently, stress-responsive genes (e.g., GhDREB2A) were downregulated, underscoring that GhNST1 as a key integrator of drought resistance and developmental regulation [32]. Collectively, these studies highlight the potential of mining and characterizing early-maturity-related genes in upland cotton to enrich the genetic foundation for molecular marker development and the breeding of early-maturing and superior-quality cotton germplasm. In this study, we conducted a comprehensive phylogenetic analysis of the DnaJs gene family to delineate evolutionary conservation and diversification patterns in upland cotton, followed by the investigation of conserved protein motifs, gene structure, and promoter cis-acting elements. Moreover, Tissue-specific expression profiles of GhDnaJs were characterized to understand its expression characteristics. Subsequently, GhDnaJ316 was functionally validated through virus-induced gene silencing (VIGS), revealing its regulatory role in floral development. This study provides potential gene resources for molecular breeding in cotton.

2. Results

2.1. Identification and Physiochemical Properties of GhDnaJs

Bioinformatic analysis of the G. hirsutum genome identified a total of 372 candidate DnaJ genes. These genes were systematically designated as GhDnaJ01 to GhDnaJ372 based on their chromosomal locations for convenience (Table S2). Physicochemical characterization revealed that DnaJ proteins exhibit an average molecular weight of 52.68 kDa. Their isoelectric points (pI) ranged from 4.49 to 11.29, with instability indices spanning 19.03 to 79.03. Among them, approximately 55% of the DnaJ protein family exhibited pI values exceeding 7, indicating a balanced distribution of acidic and basic isoforms within G. hirsutum (Table S3). Subcellular localization predictions indicated that DnaJ proteins were primarily localized to the nucleus (44.62%), chloroplasts (21.77%), cytoplasm (16.67), and plasma membrane (8.87%), with minor distributions observed in the mitochondrion (3.49%), vacuolar membrane (1.61%), peroxisome (1.08%), cytoskeleton (1.08%), extracellular (0.54%), and endoplasmic reticulum (0.27%) (Figure S1).

2.2. Phylogenetic Tree Analysis

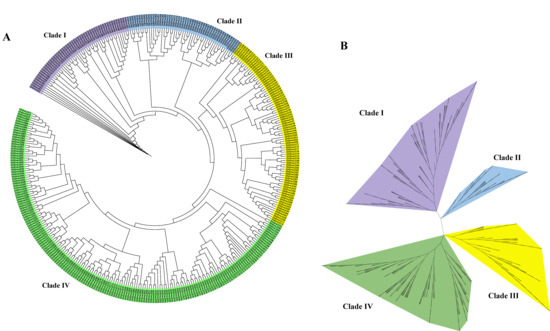

To elucidate phylogenetic relationships and classification patterns within the GhDnaJ gene family, we employed 372 protein sequences from G. hirsutum to reconstruct an unrooted phylogenetic tree based on multiple sequence alignment (Figure 1). To delineate the clustering relationships within the phylogenetic tree with enhanced clarity, we generated circular and radial phylogenetic tree diagrams. The phylogenetic topology from both circular and radial tree suggested that the DnaJ gene family in G. hirsutum diverged into four major clades (Clade I, II, III, and IV), comprising 53, 50, 86, and 183 members, respectively, indicating a primary classification framework comprising four distinct subfamilies. Additionally, the reconstructed phylogenetic tree incorporating DnaJ protein sequences from G. hirsutum and A. thaliana exhibited obvious similarity in topological structure to the tree generated exclusively from G. hirsutum DnaJ sequences, consistently supporting the division of the DnaJ family into four evolutionary clades (Figure S2).

Figure 1.

Phylogenetic relationships of the 372 DnaJ proteins in G. hirsutum. (A) Circular phylogenetic tree. (B) Radial phylogenetic tree diagram.

2.3. Gene Structure and Conserved Domain

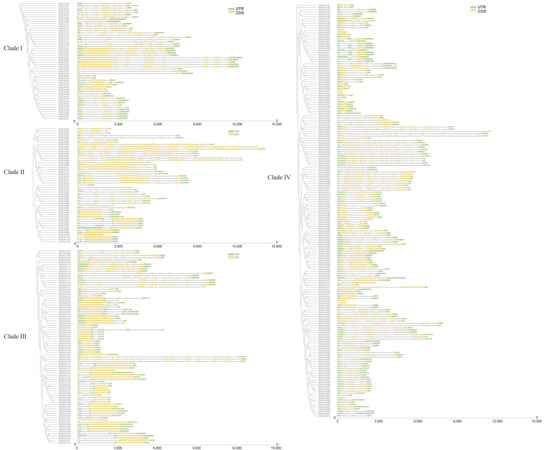

The intron–exon architecture, intron classification, and intron density collectively represent typical phylogenetic signatures within gene families. Comparative analysis of intron–exon architectures across 372 GhDnaJ genes revealed conserved structural patterns within individual phylogenetic clades, whereas significant divergences were observed among distinct evolutionary branches (Figure 2). Intron count across the GhDnaJ gene family exhibited a range of 1 to 22, with a minority of genes (1–2 introns) classified as low-intron variants. Clade-specific analysis revealed distinct distribution patterns: genes in Clade I consistently contained 4–10 introns, whereas Clades II, III, and IV displayed broader variation (1–21, 1–19, and 1–22 introns, respectively). The predicted conserved motifs of DnaJ genes corroborated the evolutionary classification established by DnaJs family phylogenetic analysis. The sequence features and amino acid lengths of conserved motifs are shown in Figure S3, with Motifs 1–4 and Motif 9 identified as structurally conserved DnaJ domains across all analyzed DnaJ proteins. Members of the DnaJ gene family on evolutionary clade I contain one to five motifs, whereas those on clades II, III, and IV all possess Motifs 8, 10,11, and 14. The prediction of these motifs demonstrates that the DnaJ gene family exhibits relative functional and structural conservation among members within the same evolutionary clade.

Figure 2.

Structural analysis of GhDnaJ genes within individual phylogenetic clades. Green bars represent untranslated regions (UTRs), while yellow bars denote coding sequences (CDSs).

2.4. Chromosome Location, Gene Structures, and Cis-Acting Elements

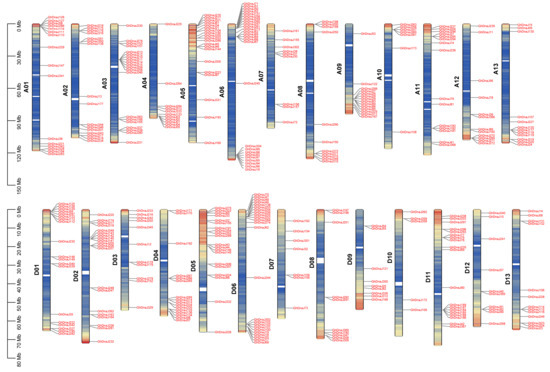

To investigate the distribution and structural characteristics of the DnaJ gene family, chromosomal localization and gene structure analysis were performed. The results revealed that 372 DnaJ genes in G. hirsutum are predominantly distributed at the terminal regions of chromosomes. The A06 chromosome harbored the highest number of DnaJ genes, totaling 26, whereas D10 chromosomes exhibit the lowest DnaJ gene content, with 5 genes, indicating an uneven distribution of the DnaJ family across the A and D subgenomes (Figure 3). Secondary structure prediction demonstrated that DnaJ proteins in G. hirsutum primarily consist of α-helices, β-sheets, and random coils, accounting for 38.30%, 7.51%, and 54.19% of the structural composition, respectively (Figure S4). Tertiary structure analysis of representative genes from major clades in the phylogenetic tree further revealed distinct structural patterns: Clade I and Clade II members exhibited prominent α-helix content and a small amount of random coils; Clade III and Clade IV members were dominated by random coils except for several GhDnaJ proteins (Figure S5). This demonstrated that clade-specific divergence in both secondary and tertiary folds, likely facilitate the subfunctionalization within DnaJs family during polyploid evolution.

Figure 3.

Chromosome location of GhDnaJ genes across the A and D subgenomes. Red color indicates the positions of GhDnaJs gene family members on the chromosomes. The color on the chromosomes transitions from red to blue, with red representing regions of dense GhDnaJs gene distribution. Yellow represents regions of scattered GhDnaJs gene distribution, and blue represents regions with no GhDnaJs gene distribution. The A06 chromosome harbored the most quantity of GhDnaJ genes, reaching 26, while D10 contained the fewest with a number of 5.

Multiple cis-acting elements were identified within the 2000-bp upstream sequences of the transcription start sites of DnaJ genes in G. hirsutum, encompassing defense and stress-responsive elements (such as drought induced, wound response, low temperature response, and anaerobic induction), phytohormone-responsive elements (including abscisic acid response, gibberellin response, auxin response, salicylic acid response, and zein metabolism regulation), binding sites (e.g., AT-rich DNA binding protein, MYBHv1 binding site, and conserved DNA module array), spatial expression elements (e.g., differentiation of the palisade mesophyll cells, meristem expression, and endosperm expression), and biological process-related elements (including circadian control, cell cycle regulation, and light response) (Figure S6). The presence of these elements suggests that DnaJ genes were involved in both developmental processes and environmental stress responses in G. hirsutum.

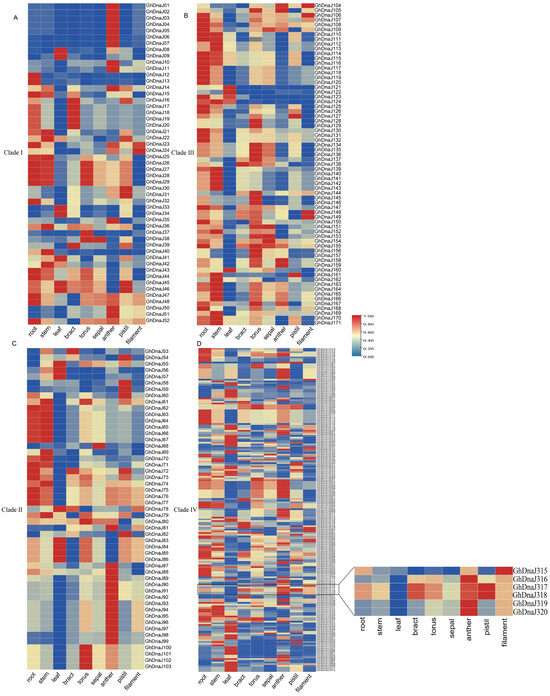

2.5. Analysis of the DnaJs Expression Pattern

Transcriptomic analysis via the CottonMD database (https://yanglab.hzau.edu.cn/CottonMD, accessed on 6 July 2025) revealed widespread expression of DnaJ homologs in upland cotton. Following exclusion of 13 genes with undetectable expression, the spatial expression profiles of 359 retained DnaJ genes were analyzed across multiple tissues, including root, stem, leaf, and reproductive tissues. The results demonstrated that genes such as GhDnaJ124 (highly expressed in root) and GhDnaJ21 (highly expressed in filament) were highly expressed in single tissues, suggesting their potential roles in specific developmental functions. GhDnaJ341 exhibited high expression in stems, leaves, and receptacles, indicating its involvement in developmental regulation across multiple organs (Figure 4). GhDnaJ190 showed notably high expression in bracts, while GhDnaJ304 was highly expressed in receptacles, suggesting both may function as core regulatory genes. It is worth noting that GhDnaJ316 displayed relatively high expression in both anthers and filaments, implying its critical role in floral development. It is critical to clarify that the term “floral development” in this context specifically denotes the maturation phase of floral organs subsequent to their initial formation, rather than the processes of organogenesis or primordial differentiation.

Figure 4.

The expression pattern of the DnaJ gene family in different evolutionary branches in multiple tissues of upland cotton. (A) The expression pattern of DnaJs in Clade I. (B) The expression pattern of DnaJs in Clade II. (C) The expression pattern of DnaJs in Clade III. (D) The expression pattern of DnaJs in Clade IV.

2.6. Functional Validation of GhDnaJ316 in the Floral Development of Upland Cotton

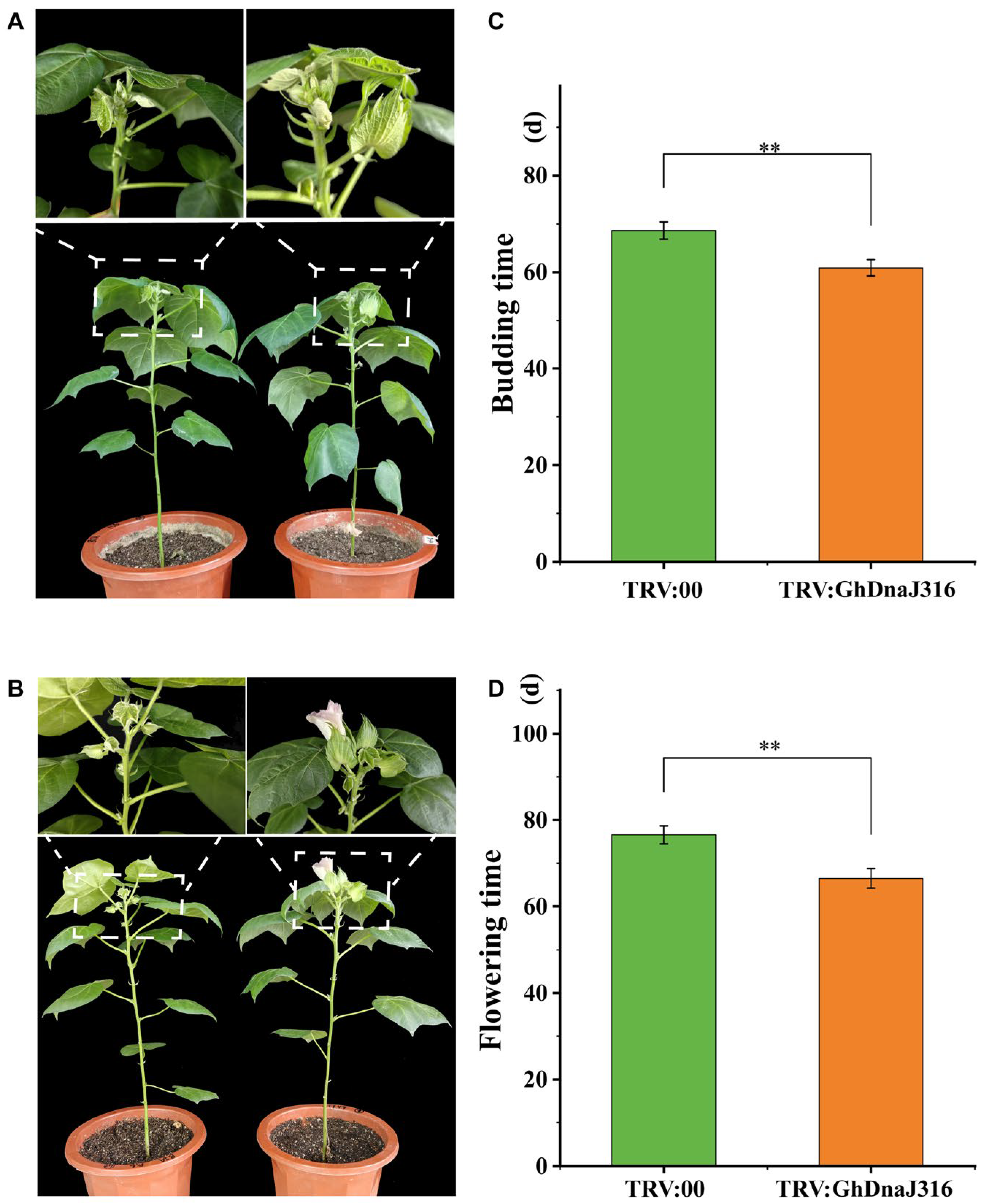

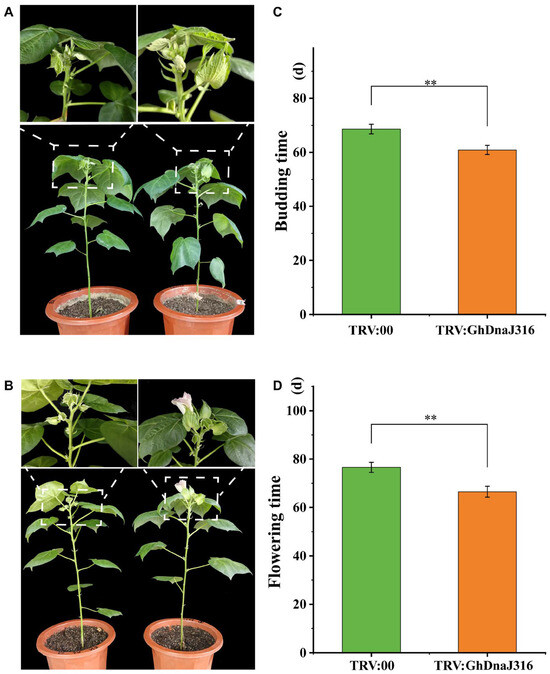

During floral organ development in G. hirsutum, stamens form first, followed by the differentiation of stamen primordia into anthers and filaments. Thus, to identify DnaJ family members associated with floral development, we prioritized GhDnaJ genes exhibiting high expression in anthers and filaments. Intriguingly, GhDnaJ316 showed pronounced expression in these tissues, suggesting its likely association with floral development. Consequently, we chose GhDnaJ316 to elucidate its function in regulating flowering time via virus-induced gene silencing assays (VIGS). The VIGS here was performed using a TRV-based vector to achieve rapid and efficient target gene suppression, enabling systematic statistics of phenotypic changes in GhDnaJ316-silenced plants (Figure 5A,B). qRT–PCR analysis confirmed significant knockdown of target gene expression in TRV:GhDnaJ316 plants compared to empty vector controls, validating effective silencing (p < 0.05, Figure S7, Table S4). Compared to controls, TRV:GhDnaJ316 plants exhibited precocious budding (7.7 days earlier, p < 0.01) and flowering (9.7 days earlier, p < 0.01) (Figure 5C,D, Tables S5 and S6), indicating that GhDnaJ316 functions as a negative regulator of floral transition and development.

Figure 5.

Silencing of GhDnaJ316 promotes cotton budding and flowering time. (A) The phenotypes during budding time in control and GhDnaJ316-silenced plants. (B) The phenotypes for flowering time in control and GhDnaJ316-silenced plants. (C) The budding time statistics in control and GhDnaJ316-silenced plants. (D) The flowering time statistics in control and GhDnaJ316-silenced plants. The asterisks “**” here indicate that the significance level reached p < 0.01.

3. Discussion

As a crucial natural textile fiber and oilseed crop, cotton ranks among the highest-valued economic crops globally, serving as a primary source of edible oil and livestock feed derivatives [33]. However, cotton plants are frequently confronted with abiotic stresses such as drought, low accumulated temperature, and short frost-free periods [34,35]. These climatic constraints adversely affect plant growth and development, ultimately compromising cotton yield and fiber quality. The development and breeding of early-maturing cotton germplasm can effectively mitigate the impacts of such abiotic stresses. Therefore, identifying key genes associated with early-maturity traits such as early flowering, is crucial for enhancing yield and agronomic performance in cotton [36,37,38]. DnaJ cochaperones form dynamic complexes with Hsp70 chaperones to regulate ATP hydrolysis-driven conformational changes, thereby facilitating protein folding, substrate translocation, and degradation of misfolded polypeptides through allosteric modulation of the Hsp70 functional cycle [39,40]. Despite the established significance of the DnaJ-Hsp70 chaperone complex in proteostasis, the expression dynamics and functional diversification of the DnaJ protein family in cotton remain to be fully elucidated.

Systematic identification of gene families in genomes serves as a cornerstone for elucidating evolutionary relationship and inferring functional attributes of genes, thereby enabling the formulation and empirical validation of hypotheses regarding their biological roles [41,42,43]. Recent studies have identified DnaJ proteins as ubiquitously involved in diverse plant growth and developmental processes across several species, including pepper, soybean, and wheat [44,45,46]. In this study, a genome-wide investigation elucidated the phylogenetic relationships and genetic characteristics of entire 372 DnaJ genes in G. hirsutum, integrating phylogenetic reconstruction, conserved domain profiling, and structural diversification analyses to delineate evolutionary trajectories and functional divergence. We observed that the DnaJ gene family exhibits a distribution bias toward telomeric regions rather than centromeric regions across chromosomes. This distributional preference might be associated with the cotton-specific genomic architecture, where centromeric regions are predominantly characterized by high-density repetitive sequences and a paucity of functional genes [47]. The phylogenetic tree revealed that the DnaJ gene family diverged into four major evolutionary clades, with significant variations in genomic structure composition and conserved motifs among members of these clades. This observation aligns with the canonical classification of the DnaJ protein family into Type I to Type IV, which is defined by conserved structural domains [6,48]. A similar phylogenetic topology is exhibited in Vitis vinifera in terms of this gene family [49]. This pattern suggests that the DnaJ genes in upland cotton likely underwent horizontal gene duplication events, leading to the formation of distinct paralogous subfamilies. Genomic diversification concomitantly drives functional divergence within the gene family, as evidenced by differential expression patterns and stress-responsive specialization among subfamily members [50]. In essence, the retention and subsequent functional diversification of duplicated genes serve as an evolutionary substrate upon which natural selection acts, thereby facilitating the emergence of adaptive traits that confer competitive advantages in dynamic ecological contexts [51].

Cis-acting elements function as critical genomic determinants that orchestrate plant developmental programs and environmental adaptations through sequence-specific interactions with transcription factors. These interactions precisely modulate transcriptional initiation rates and efficiency by recruiting RNA polymerase complexes to core promoters, thereby establishing spatiotemporal control of gene expression networks [52]. Comprehensive cis-acting element profiling in the GhDnaJ gene family promoters identified diverse motifs, including circadian-associated elements, cell cycle-regulated elements, and photoresponsive motifs that coordinate developmental processes. This configuration suggests the hypothesis that GhDnaJ genes modulate biosynthetic and metabolic regulation during both vegetative and reproductive development in cotton [53]. Transcriptional profiling of GhDnaJ genes revealed elevated expression across multiple tissues, with GhDnaJ316 exhibiting notably high transcript abundance in both anthers and filaments, suggesting its potential involvement in floral development (Figure 4). For functional validation, we performed silencing experiment on GhDnaJ316 gene. The results revealed that the silencing of GhDnaJ316 via VIGS accelerated floral transition in cotton, evidenced by precocious budding and flowering times compared to controls. These findings revealed that GhDnaJ316 act a role as a negative regulator of floral development.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Genome-Wide Identification of DnaJ Gene Family

The whole-genome sequencing data of Gossypium hirsutum (upland cotton) were retrieved from the Phytozome database (https://phytozome-next.jgi.doe.gov/, accessed on 2 April 2025). The hidden Markov model (HMM) profile for DnaJ genes, downloaded from the Pfam database, was employed as an informational probe for domain retrieval using HMMER software(http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/hmmer, accessed on 11 April 2025) [54]. Concurrently, DnaJ protein sequences of Arabidopsis thaliana were obtained from the TAIR database (https://www.arabidopsis.org/, accessed on 14 April 2025) and subjected to BLASTP analysis (E-value set to 1 × 10−5) to identify homologous sequences. The results from both HMMER (hmmsearch) and BLASTP analyses were consolidated, and redundant or incomplete sequences were removed. Conserved domains were subsequently validated using the NCBI Conserved Domain Database (CDD; https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/, accessed on 20 April 2025). Sequences lacking essential structural domains characteristic of the DnaJ gene family were excluded, yielding the final set of DnaJ gene family sequences.

4.2. Physicochemical Properties and Subcellular Localization

Physicochemical properties of DnaJ family members including amino acid counts, molecular weight, isoelectric point (pI), instability index, grand average of hydropathicity (GRAVY), and aliphatic index, were predicted using the online ProtParam tool (https://web.expasy.org/protparam/, accessed on 29 April 2025). The predictions for subcellular localization were performed using WoLF PSORT (https://wolfpsort.hgc.jp/, accessed on 8 May 2025) [55].

4.3. Chromosomal Localization and Structural Prediction

Chromosomal positions of DnaJ gene family were extracted from the annotated gff3 file. The TBtools v2.331 software [56] was used to map the distribution of DnaJ genes across chromosomes. Secondary and tertiary structures of DnaJ proteins were predicted using SOPMA (https://npsa-prabi.ibcp.fr/cgi-bin/npsa_automat.pl?page=/NPSA/npsa_sopma.html, accessed on 23 May 2025) [57] and SWISS-MODEL (https://swissmodel.expasy.org, accessed on 26 May 2025) [58].

4.4. Analysis of Conserved Motifs, Gene Structure, and Cis-Acting Elements

Conserved motifs within DnaJ protein sequences were identified using MEME (https://gensoft.pasteur.fr/docs/meme/4.11.2/meme-chip.html, accessed on 30 May 2025) with the multiple expectation maximization for motif elicitation algorithm, setting the maximum number of motifs to 15 [59]. Then, gene structures were predicted using GSDS v2.0 (http://GSDS.cbi.pku.edu.cn, accessed on 1 June 2025) [60]. To identify cis-elements, the promoter sequences including 2000 bp upstream of the start codon were analyzed using PlantCARE (http://bioinformatics.psb.ugent.be/webtools/plantcare/html/, accessed on 4 June 2025). And elements responsive to environmental stimuli, hormones, and developmental processes were statistically analyzed.

4.5. Phylogenetic Analysis of the DnaJ Gene Family

To investigate evolutionary relationships among DnaJ family members, the protein sequences from G. hirsutum were aligned using MAFFT [61], and a maximum-likelihood phylogenetic tree was constructed using IQ-TREE with 1000 bootstrap replicates. The tree was visualized via the iTOL web server (https://itol.embl.de/, accessed on 13 June 2025).

4.6. Tissue-Specific Expression Analysis

Transcriptome data from G. hirsutum tissues (root, stem, leaf, bract, torus, sepal, anther, pistil and filament) were analyzed to determine DnaJ gene expression patterns. TPM (transcripts per million) values for DnaJ genes were calculated using the RPKM/FPKM and TPM Calculator subroutine in TBtools. Log-transformed TPM values were used to generate expression heatmaps. Differential expression analysis across tissues was performed using Rstudio v4.3.2 [62].

4.7. Silencing of GhDnaJ316 by VIGS in Upland Cotton

Through transcriptome expression pattern analysis and literature review, we identified that GhDnaJ316 in the DnaJ gene family may regulate flowering in G. hirsutum. To functionally validate this gene, we silenced GhDnaJ316 using VIGS. Target-specific silenced fragments (300–500 bp) were cloned into the TRV-based vector pYL156, and the resulting constructs were transformed into Agrobacterium strain GV3101 using a freeze–thaw method [30]. Primers for constructing the TRV-based vector pYL156 to silence the target gene are listed in Table S1. Helper vector pYL192 was combined with TRV constructs (TRV:GhDnaJ316 and TRV:00) at a 1:1 ratio, incubated at 28 °C for 3 h, and co-infiltrated into cotyledons of 8-day-old cotton plants. Virus-infected seedlings were incubated in darkness at 25 °C for 24 h, then transferred to a 16-h-light/8-h-dark photoperiod. Following albinism emergence in the positive control (TRV:GhDnaJ316), plants with gene expression levels below 50% of TRV:00 controls were selected by qRT-PCR and designated as TRV:GhDnaJ316 plants. Here we implemented biological replicated pooling for both the experimental group (TRV:GhDnaJ316) and control group (TRV:00) to ensure data representativeness and minimize individual variation bias [63,64]. Finally, we quantified two phenological traits: budding time (defined as the first occurrence of floral buds ≥ 2 mm in diameter at the shoot apical meristem) and flowering time (the duration from budding to the full anthesis of the first flower). in the TRV:00 and TRV:GhDnaJ316 plants. It is to be clarified that the observed sample size discrepancy arises from differential phenotyping feasibility across developmental stages, wherein rapid bud enclosure during squaring impedes precise trait capture, while stabilized floral phenotypes at flowering enable complete recording—a well-documented limitation in plant developmental biology due to trait observability constraints. Despite this variation, the effective sample size for phenological traits analysis meets field-accepted statistical standards [33].

5. Conclusions

In the present study, a total of 372 DnaJ genes were identified in Gossypium hirsutum, which were phylogenetically classified into four clades with clade-specific structural variations in intron architecture and conserved motifs. Chromosomal distribution analysis revealed non-uniform localization. Cis-element profiling implicated GhDnaJs in regulating biosynthetic and metabolic pathways during vegetative and reproductive development. Tissue-specific expression revealed the high expression of GhDnaJ316 in anthers and filaments. VIGS-mediated silencing confirmed GhDnaJ316 as a negative regulator of floral transition, accelerating budding and flowering times by 7.7 days and 9.7 days, respectively, in silenced plants. These findings elucidated the genomic features of GhDnaJs and its negative regulator role in floral development, laying a foundational framework for further elucidating their roles in cotton early-maturing trait development, providing valuable implications for cotton breeding programs.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/plants14213380/s1: Figure S1: Subcellular localization of DnaJ protein members in G. hirsutum; Figure S2: Phylogenetic relationships of the DnaJ proteins in G. hirsutum and A. thaliana. (A) Circular phylogenetic tree. (B) Radial phylogenetic tree diagram; Figure S3: The conserved motifs of GhDnaJ genes; Figure S4: Secondary structure predictions of DnaJ protein members. Light green represents α-helices, yellow denotes β-sheets, and dark green indicates random coils; Figure S5: Tertiary structure of representative DnaJ family members from major clades in the phylogenetic tree; Figure S6: The prediction of cis-acting elements of GhDnaJ genes within individual phylogenetic clades; Figure S7: qRT–PCR analysis of GhDnaJ316 expression in empty vector and silenced (TRV:GhDnaJ316) plants; Table S1: Fluorescent quantitative primers; Table S2: The location statistics of DnaJ gene family within individual phylogenetic clades; Table S3: Physicochemical properties of DnaJ protein members in G. hirsutum; Table S4: Statistics of relative expression in empty vector and silenced plants; Table S5: Statistics of budding time in empty vector and silenced plants; Table S6: Statistics of flowering time in empty vector and silenced plants; Data S1: The sequences of 372 DnaJ proteins within upland cotton.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, T.-T.Z. and J.-J.S.; methodology, X.-F.G.; software, D.-D.L.; validation, Y.J., C.-H.W. and Y.-N.F.; formal analysis, T.-T.Z.; investigation, C.-X.W.; resources, X.-F.G.; data curation, D.-D.L.; writing—original draft preparation, T.-T.Z.; writing—review and editing, C.-H.W. and Y.-N.F.; visualization, C.-X.W.; supervision, J.-J.S.; project administration, J.-J.S. and T.-T.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by Gansu Province Youth Science and Technology Fund Project (25JRRA367).

Data Availability Statement

Data are contained within the article and Supplementary Materials. Transcriptome data for different tissues were obtained from public databases.

Acknowledgments

The authors thank Gansu Computing Center for providing computational resources for this study.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Georgopoulos, C.P.; Lundquist-Heil, A.; Yochem, J.; Feiss, M. Identification of the E. coli DnaJ gene product. Mol. Genet. Genom. 1980, 178, 583–588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liberek, K.; Marszalek, J.; Ang, D.; Georgopoulos, C.; Zylicz, M. Escherichia coli DnaJ and GrpE heat shock proteins jointly stimulate ATPase activity of DnaK. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 1991, 88, 2874–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hennessy, F.; Nicoll, W.S.; Zimmermann, R.; Cheetham, M.E.; Blatch, G.L. Not all J domains are created equal: Implications for the specificity of Hsp40-Hsp70 interactions. Protein Sci. 2005, 14, 1697–1709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qiu, X.B.; Shao, Y.M.; Miao, S.; Wang, L. The diversity of the DnaJ/Hsp40 family, the crucial partners for Hsp70 chaperones. Cell Mol. Life Sci. 2006, 63, 2560–2570. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rajan, V.B.V.; D’Silva, P. Arabidopsis thaliana J-class heat shock proteins: Cellular stress sensors. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2009, 9, 433–446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verma, A.K.; Tamadaddi, C.; Tak, Y.; Lal, S.S.; Cole, S.J.; Hines, J.K.; Sahi, C. The expanding world of plant J-domain proteins. Crit. Rev. Plant Sci. 2019, 38, 382–400. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mukherjee, A. Role of DnaK-DnaJ proteins in PSII repair. Plant Physiol. 2020, 182, 1804–1805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.M.; Holmström, M.; Raksajit, W.; Suorsa, M.; Piippo, M.; Aro, E.-M. Small chloroplast-targeted DnaJ proteins are involved in optimization of photosynthetic reactions in Arabidopsis thaliana. BMC Plant Biol. 2010, 10, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Bai, Z.; Ouyang, M.; Xu, X.; Xiong, H.; Wang, Q.; Grimm, B.; Rochaix, J.D.; Zhang, L. The DnaJ proteins DJA6 and DJA5 are essential for chloroplast iron-sulfur cluster biogenesis. EMBO J. 2021, 40, e106742. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhao, L.; Jia, T.; Jiao, Q.; Hu, X. Research Progress in J-Proteins in the chloroplast. Genes 2022, 13, 1469. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitha, S.; Froehlich, J.E.; Koksharova, O.; Pyke, K.A.; Erp, H.; Osteryoung, K.W. ARC6 is a J-domain plastid division protein and an evolutionary descendant of the cyanobacterial cell division protein Ftn2. Plant Cell 2003, 15, 1918–1933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Takano, A.; Suetsugu, N.; Wada, M.; Kohda, D. Crystallographic and functional analyses of J-domain of JAC1 essential for chloroplast photorelocation movement in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant Cell Physiol. 2010, 51, 1372–1376. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pulido, P.; Toledo-Ortiz, G.; Phillips, M.A.; Wright, L.P.; Rodríguez-Concepción, M. Arabidopsis J-Protein J20 Delivers the First Enzyme of the Plastidial Isoprenoid Pathway to Protein Quality Control. Plant Cell 2013, 25, 4183–4194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kong, F.; Deng, Y.; Zhou, B.; Wang, G.; Wang, Y.; Meng, Q. A chloroplast-targeted DnaJ protein contributes to maintenance of photosystem II under chilling stress. J. Exp. Bot. 2014, 65, 143–158. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pulido, P.; Llamas, E.; Llorente, B.; Ventura, S.; Wright, L.P.; Rodríguez-Concepción, M. Specific Hsp100 chaperones determine the fate of the first enzyme of the plastidial isoprenoid pathway for either refolding or degradation by the stromal Clp protease in Arabidopsis. PLoS Genet. 2016, 27, e1005824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jiang, L.; Ren, Y.; Luo, H.; Liu, H.; Wu, J.; Hu, S.; Jiang, Y.; Wang, G. Identification and functional analysis of J-domain proteins involved in determining flowering time in Phalaenopsis orchids. Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2025, 226, 110081. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhi, L.; Zhang, H.; Mao, Y.; Liang, L.; Ni, H.; Li, P.; Huang, J.; Zhu, Y.; Hu, X. A J-domain protein J3 antagonizes ABI5-binding protein2 to Regulate constans stability and flowering time. Plant Cell Environ. 2025, 48, 4743–4755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yamamoto, M.; Uji, S.; Sugiyama, T.; Sakamoto, T.; Kimura, S.; Endo, T.; Nishikawa, S. ERdj3B-mediated quality control maintains anther development at high temperatures. Plant Physiol. 2020, 182, 1979–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, M.Y.; Kim, S.Y. The Arabidopsis J protein AtJ1 is essential for seedling growth, flowering time control and ABA response. Plant Cell Physiol. 2014, 55, 2152–2163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Zhao, L.; Wang, J.; Lu, N.; Ma, W.; Ma, J.; Zhang, Y.; Fu, P.; Yao, C.; Hu, J.; et al. Genome-wide identification of DnaJ gene family in Catalpa bungei and functional analysis of CbuDnaJ49 in leaf color formation. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1116063. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, K.-W.; Rahman, M.A.; Kimi, K.-Y.; Choi, G.J.; Cha, J.-Y.; Cheong, M.S.; Shohael, A.M.; Jones, C.; Lee, S.-H. Overexpression of the alfalfa DnaJ-like protein (MsDJLP) gene enhances tolerance to chilling and heat stresses in transgenic tobacco plants. Turk. J. Biol. 2018, 42, 12–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, G.; Cai, G.; Xu, N.; Zhang, L.; Sun, X.; Guan, J.; Meng, Q. Novel DnaJ protein facilitates thermotolerance of transgenic tomatoes. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2019, 20, 367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hsu, P.K.; Dubeaux, G.; Takahashi, Y.; Schroeder, J.I. Signaling mechanisms in abscisic acid-mediated stomatal closure. Plant J. 2021, 105, 307–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, Y.; Li, M.; Yu, J.; Ma, A.; Wang, J.; Yun, D.-J.; Xu, Z.-Y. Plasma membrane-localized Hsp40/DNAJ chaperone protein facilitates OsSUVH7-OsBAG4-OsMYB106 transcriptional complex formation for OsHKT1;5 activation. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2023, 65, 265–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, T.; Hu, Y.; Jiang, W.; Fang, L.; Guan, X.; Chen, J.; Zhang, J.; Saski, C.A.; Scheffler, B.E.; Stelly, D.M.; et al. Sequencing of allotetraploid cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L. acc. TM-1) provides a resource for fiber improvement. Nat. Biotechnol. 2015, 33, 531–537. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jans, Y.; Bloh, W.V.; Schaphoff, S.; Müller, C. Global cotton production under climate change-Implications for yield and water consumption. Hydrol. Earth Syst. Sci. 2021, 25, 2027–2044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, S.; Xu, M.; Liu, F.; Cui, C.; Zhou, B. Reconstruction of the full-length transcriptome atlas using PacBio Iso-Seq provides insight into the alternative splicing in Gossypium australe. BMC Plant Biol. 2019, 19, 365. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pan, Y.; Meng, F.; Wang, X. Sequencing multiple cotton genomes reveals complex structures and lays foundation for breeding. Front. Plant Sci. 2020, 11, 560096. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farooq, M.; Naqvi, R.Z.; Amin, I.; Rehman, A.U.; Asif, M.; Mansoor, S. Transcriptome diversity assessment of Gossypium arboreum (FDH228) leaves under control, drought and whitefly infestation using PacBio long reads. Gene 2023, 852, 147065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Su, J.; Li, D.; Yuan, W.; Li, Y.; Ju, J.; Wang, N.; Ling, P.; Feng, K.; Wang, C. Integrating RTM-GWAS and meta-QTL data revealed genomic regions and candidate genes associated with the first fruit branch node and its height in upland cotton. Theor. Appl. Genet. 2024, 137, 207. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, C.; Liu, J.; Xie, X.; Wang, J.; Ma, Q.; Chen, P.; Yang, D.; Ma, X.; Hao, F.; Su, J. GhAP1-D3 positively regulates flowering time and early maturity with no yield and fiber quality penalties in upland cotton. J. Integr. Plant Biol. 2023, 65, 985–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Li, D.; Guo, X.; Yang, Q.; Xu, W.; Yu, X.; Yang, J.; Wang, F.; Su, J.; Wang, C. Comprehensive evolutionary, differential expression and VIGS analyses reveal the function of GhNST1 in regulating drought tolerance and early maturity in upland cotton. Funct. Integr. Genom. 2025, 25, 195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, Z.; He, S.; Wang, X.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, G.; Wu, L.; Li, Z.; Liu, Z.; Sun, G.; et al. Resequencing a core collection of upland cotton identifies genomic variation and loci influencing fiber quality and yield. Nat. Genet. 2018, 50, 803–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reddy, K.R.; Brand, D.; Wijewardana, C.; Gao, W. Temperature effects on cotton seedling emergence, growth, and development. Agron. J. 2017, 109, 1379–1387. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zafar, M.M.; Chattha, W.S.; Khan, A.I.; Zafar, S.; Subhan, M.; Saleem, H.; Ali, A.; Ijaz, A.; Zunaira, A.; Qiao, F.; et al. Drought and heat stress on cotton genotypes suggested agro-physiological and biochemical features for climate resilience. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 14, 1265700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gapare, W.; Conaty, W.; Zhu, Q.; Liu, S.; Stiller, W.; Llewellyn, D.; Wilson, I. Genome-wide association study of yield components and fibre quality traits in a cotton germplasm diversity panel. Euphytica 2017, 213, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, X.; Kong, F.; Gao, L.; Shen, G.; Duan, B.; Wang, Z.; Xu, D.; Fan, D.; Deng, Y.; Han, Z. Identification of QTLs for early maturity-related traits based on RIL population of two elite cotton cultivars. BMC Plant Biol. 2024, 24, 1243. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, P.; Wan, J.; Guo, L.; Xiong, X.; Zhao, C.; Liu, Q.; Yu, J.; Xiang, L.; Liu, J.; Li, W.; et al. A MADS-box protein GhAGL8 promotes early flowering and increases yield without compromising fiber quality in cotton. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 225, 120545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kampinga, H.H.; Craig, E.A. The HSP70 chaperone machinery: J proteins as drivers of functional specificity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 2010, 11, 579–592. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mayer, M.P.; Gierasch, L.M. Recent advances in the structural and mechanistic aspects of Hsp70 molecular chaperones. J. Biol. Chem. 2018, 294, 2085–2097. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shahrajabian, M.H.; Sun, W.; Cheng, Q. Molecular breeding and the impacts of some important genes families on agronomic traits, a review. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2021, 68, 1709–1730. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nestor, B.J.; Bayer, P.E.; Fernandez, C.G.T.; Edwards, D.; Finnegan, P.M. Approaches to increase the validity of gene family identification using manual homology search tools. Genetica 2023, 151, 325–338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Li, G.; Chen, Z.; Guo, X.; Tian, D.; Li, C.; Lin, M.; Hu, C.; Yan, J. Genome-wide identification and analysis of maize DnaJ family genes in response to salt, heat, and cold at the seedling stage. Plants 2024, 13, 2488. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, F.F.; Liu, F.; Yang, X.; Wan, H.; Kang, Y. Global analysis of expression profile of members of DnaJ gene families involved in capsaicinoids synthesis in pepper (Capsicum annuum L). BMC Plant Biol. 2020, 20, 326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, T.T.; Xu, M.; Gao, S.; Zhang, Y.; Hu, Y.; Jin, P.; Cai, L.; Cheng, Y.; Chen, J.; Yang, J.; et al. Genome-wide identification and analysis of the regulation wheat DnaJ family genes following wheat yellow mosaic virus infection. J. Integr. Agric. 2022, 21, 153–169. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, B.; Liu, Z.; Zhou, R.; Cheng, P.; Li, H.; Wang, Z.; Liu, Y.; Li, M.; Zhao, Z.; Hu, Z.; et al. Genome-wide analysis of soybean DnaJA-family genes and functional characterization of GmDnaJA6 responses to saline and alkaline stress. Crop J. 2023, 11, 1230–1241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chang, X.; He, X.; Li, J.; Liu, Z.; Pi, R.; Luo, X.; Wang, R.; Hu, X.; Lu, S.; Zhang, X.; et al. High-quality Gossypium hirsutum and Gossypium barbadense genome assemblies reveal the landscape and evolution of centromeres. Plant Commun. 2024, 5, 100722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamadaddi, C.; Verma, A.K.; Zambare, V.; Vairagkar, A.; Diwan, D.; Sahi, C. J-like protein family of Arabidopsis thaliana: The enigmatic cousins of J-domain proteins. Plant Cell Rep. 2022, 41, 1343–1355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Xu, T.; Zhang, T.; Liu, T.; Shen, L.; Chen, Z.; Wu, Y.; Yang, J. Genome-Wide Identification and Characterization of DnaJ Gene Family in Grape (Vitis vinifera L.). Horticulturae 2021, 7, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Xiao, X.; Li, Y.; Gu, L.; Zhang, Y.; Peng, Y.; Wei, F. Genome-wide identification and expression analysis of the DnaJ genes in Gossypium hirsutum. Ind. Crops Prod. 2025, 228, 120904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.X.; Li, X.X.; Zhao, R.; Zhou, Y.; Jiao, Y.N. Evolutionary strategies drive a balance of the interacting gene products for the CBL and CIPK gene families. New Phytol. 2020, 226, 1506–1516. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schmitz, R.J.; Grotewold, E.; Stam, M. Cis-regulatory sequences in plants: Their importance, discovery, and future challenges. Plant Cell 2022, 34, 718–741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hernandez-Garcia, C.M.; Finer, J.J. Identification and validation of promoters and cis-acting regulatory elements. Plant Sci. 2014, 217, 109–119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Finn, R.D.; Clements, J.; Eddy, S.R. HMMER web server: Interactive sequence similarity searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2011, 39, 29–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Horton, P.; Park, K.J.; Obayashi, T.; Fujita, N.; Harada, H.; Adams-Collier, C.J.; Nakai, K. WoLF PSORT: Protein localization predictor. Nucleic Acids Res. 2007, 35, W585–W587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.J.; Chen, H.; Zhang, Y.; Thomas, H.R.; Frank, M.H.; He, Y.; Xia, R. TBtools: An integrative toolkit developed for interactive analyses of big biological data. Mol. Plant 2020, 13, 1194–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geourjon, C.; Deléage, G. SOPMA: Significant improvements in protein secondary structure prediction by consensus prediction from multiple alignments. Comput. Appl. Biosci. 1995, 11, 681–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.; Bertoni, M.; Bienert, S.; Studer, G.; Tauriello, G.; Gumienny, R.; Heer, F.T.; Beer, T.A.P.; Rempfer, C.; Bordoli, L.; et al. SWISS-MODEL: Homology modelling of protein structures and complexes. Nucleic Acids Res. 2018, 46, 296–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bailey, T.L.; Boden, M.; Buske, F.A.; Frith, M.; Grant, C.E.; Clementi, L.; Ren, J.; Li, W.W.; Noble, W.S. MEME SUITE: Tools for motif discovery and searching. Nucleic Acids Res. 2009, 37, W202–W208. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, B.; Jin, J.P.; Guo, A.Y.; Zhang, H.; Luo, J.; Gao, G. GSDS 2.0: An upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 1296–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Katoh, K.; Standley, D.M. MAFFT multiple sequence alignment software version 7: Improvements in performance and usability. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 772–780. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Conway, J.R.; Lex, A.; Gehlenborg, N. UpSetR: An R package for the visualization of intersecting sets and their properties. Bioinformatics 2017, 33, 2938–2940. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, S.; Chen, P.; Su, Z.; Ma, L.; Hao, P.; Zhang, J.; Ma, Q.; Liu, G.; Liu, J.; Wang, H.; et al. High-resolution temporal dynamic transcriptome landscape reveals a GhCAL-mediated flowering regulatory pathway in cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 153–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhang, C.; Huang, J.; Liu, Q.; Wei, H.; Wang, H.; Liu, G.; Gu, L.; Yu, S. Genomic analyses reveal the genetic basis of early maturity and identification of loci and candidate genes in upland cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.). Plant Biotechnol. J. 2021, 19, 109–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).