Abstract

This study offers considerable information on plant wealth of therapeutic importance used traditionally by the residents of 11 villages under three subdivisions of Kurseong, Darjeeling Sadar, and Mirik in the Darjeeling District, West Bengal. For the acquisition of ethnomedicinal information, semi-structured interviews were conducted with 47 informants, of whom 11 persons were herbalists and 36 were knowledgeable persons. Free prior informed consent was obtained from each participant prior to the collection of field data. A total of 115 species were documented, which spread over 65 families and 104 genera. From the informants, a total of 101 monoherbal and 21 polyherbal formulations were recorded for treating 50 types of health conditions. The collected ethnobotanical data have been evaluated to measure the utilitarian significance of remedies using three quantitative tools, informant consensus factor (Fic), use value (UV), and fidelity level (FL%). A statistical analysis revealed that among 11 disease categories, the highest Fic value was estimated for the category of digestive diseases. The plant Hellenia speciosa (J.Koenig) S.R.Dutta scored the highest use value among all the recorded plant species. In the case of the FL% analysis, the highest score (97%) was observed in Betula alnoides Buch-Ham. ex D.Don, which is used for snake bites, among the recorded 115 plant species. In addition, the present study embodies the quantitative estimation of phenolics and flavonoids, along with an HPLC analysis of the B. alnoides bark to endorse this most important and underexplored plant as a potential source of therapeutically important chemical compounds. The bark extract contains significant amounts of phenolics (87.8 mg GAE/g dry tissue) and flavonoids (30.1 mg CE/g dry tissue). An HPLC analysis unveiled a captivating ensemble of six phenolic compounds, namely, chlorogenic acid, sinapic acid, caffeic acid, coumarin, p-coumaric acid, and gallic acid. Among the identified phenolics, chlorogenic acid scored the highest amount of 117.5 mg/g of dry tissue. The present study also explored the moderate cytotoxic nature of the bark extract through an in vitro cytotoxicity assay on the L929 mouse fibroblast cell line. Our study not only documents the statistically analyzed information about ethnomedicinal practices that prevailed in the rural communities of the Darjeeling District but also highlights the profound therapeutic capabilities and non-toxic nature of B. alnoides bark.

1. Introduction

Plant-based products have been recognized as a fundamental component in the field of medicine since time immemorial. Plants with therapeutic attributes possess phytochemicals in their different parts that are responsible for healing ailments. The chemical compounds present in the plant materials elicit or alter the specific physiological responses in the ailed person and thus facilitate the treatment of various diseases both in humans and animals [1,2]. In traditional medicine, the diversity and abundance of medicinal plant resources are determined not only by the richness of the regional flora but also by the availability and convenience of using such plant resources of therapeutic power, along with the accompanying wisdom of their usage as herbal remedies. The knowledge regarding this traditional medicine is accumulated in human society over time, shaped by the local culture and environment, and passed down from generation to generation. Even in this modern age, traditional medicine plays a significant role in primary health care and is found to be a promising source of novel drug candidates.

Herbal medicine indeed has a great impact on the present-day healthcare system worldwide, especially in developing countries. Herbal medicinal products meet the primary healthcare needs of about four billion people, representing 80% of the population of developing countries [3]. In contemporary society, herbal medicine is gaining more popularity, as synthetic drugs are expensive and have multiple side effects. In fact, the more secluded the place, the more its inhabitants are reliant on traditional herbal knowledge for their health care [1]. In spite of this, traditional herbal wisdom is steadily disappearing since it is transmitted verbally from one generation to the next. The lack of interest in herbal culture among younger generations or a lack of a sense of integrity between the two generations is the primary cause of the gradual disappearance of such traditional knowledge from society. On that account, traditional therapies need to be meticulously documented for future reference in order to preserve them permanently. For this reason, scientists regularly document folk herbal knowledge through diligent ethnobotanical studies from almost all the countries of the globe, including India. The Eastern Himalayan region of India has been studied by researchers for documentation of the rich herbal knowledge sustained in its diverse ethnic communities [4,5,6].

The Darjeeling district occupies a very small pocket of the eastern Himalayas, and it is situated in the northwestern part of West Bengal, a state in India. Due to favorable climatic conditions and physiographic diversity, the Darjeeling Himalayan region has a rich repository of plant species, including medicinal plants. Certain studies exploring ethnobotanical knowledge and associated phytoresources have been undertaken in this region [7,8,9]. None of the earlier works conducted in the district, except one, has employed quantitative tools in the statistical analysis of the ethnobotanical data for focused objectivity in this type of research [10]. For a rational bioprospecting program, scientists favor the ethnobotanical knowledge evaluated using appropriate statistical indices since ethno-guided leads or information give a higher hit rate than taxonomy-guided and randomly picked leads [11]. Therefore, our study aims to document and analyze knowledge about medicinal plants used by the tribal communities residing in the rural areas of the Darjeeling District, West Bengal, India, employing statistical indices such as fidelity level (FL%), informant consensus factor (Fic), and use value (UV) index through a semi-structured questionnaire.

Ethnomedicinal information plays a pivotal role in bioprospecting and exploring prospective drug molecules through the phytochemical and pharmacological screening of traditional herbal remedies. Moreover, statistically analyzed ethnomedicinal data in an ethnobotanical study can successfully guide phytochemists in choosing the most promising candidate among the documented medicinal plants for exploring their potential bioactive compounds [12,13]. In this context, the phytochemical study has opted to illustrate the phenolic and flavonoid profiles of the bark of Betula alnoides Buch.-Ham. ex D.Don, as this plant was found to be the most significant therapeutic agent in our current ethnobotanical investigation.

The general assumption is that the products derived from medicinal plants are inherently safer due to their natural origins, minimal processing, and time-tested uses [14]. Inadequate information on plant toxicity may result in the extended use of plants with intrinsic adverse effects on the user [15]. For the safe utilization of therapeutic plants and their extracts in human healthcare, it is vital to study the toxicity profile of medicinal plants. With respect to this, as part of a safety evaluation and CC50 value determination, an in vitro cytotoxicity study of the methanolic bark extract of B. alnoides has been performed on the L929 mouse fibroblast cell line.

In summary, the current study aims to document the wide array of phytotherapeutics traditionally used by the folk communities residing in rural pockets of the Darjeeling District and to elucidate the phytochemical and toxicity profiles of the methanolic bark extract of B. alnoides.

2. Results

2.1. Sociodemographic Profile of the Informants

Information on traditional phytotherapy practices was gathered from remote areas of the Darjeeling District by interviewing the selected local informants using a standard questionnaire. A total of 47 informants were interrogated during the survey, of which 11 were herbalists, locally called “baidya” in Nepali dialect. The herbalists were the key informants in this study, and the other 36 informants were knowledgeable in the therapeutic uses of local plant wealth. Sociodemographic profiles of the respondents demonstrate that the majority of them (25.5%) belong to the Rai community, followed by Limbu (21.3%), Thapa (19.1%), Khawas (10.6%), Lepcha and Chettri (6.4% each), Sharma and Tamang (4.3% each), and Sherpa (2.1%). The people who regularly practice ethnomedicine in their day-to-day lives were mostly males (65.9%), and few were females (34.1%). Among the respondents, 14 people were between 30 and 40 years old (29.8%), 7 people belonged to the age group of 41–50 years (14.9%), 15 people belonged to the age of 51–60 years (31.9%), 8 people ranged between 61 and 70 years old (17%), and 3 people fell into the age group of 71–80 years (6.4%). All the information, including the education, experience, and occupation of the respondents, is provided in Table 1. A list of the informants who were interviewed, along with the GPS coordinates of their residences and plant collection areas, is provided in Supplementary Table S1.

Table 1.

Summary of the sociodemographic profiles of the informants (n = 47).

2.2. Ethnomedicinal Knowledge and Its Related Phytoresources

A large body of folk herbal knowledge, as well as associated phytoresources, were meticulously documented from the rural areas of the Darjeeling District after analyzing the recorded data statistically using certain ethnobotanical indices. Various aspects, like diversity, utility, and therapeutic potential of both the herbal knowledge and plant resources of the district, have been enumerated below.

2.3. Reported Medicinal Plant Species and Their Families

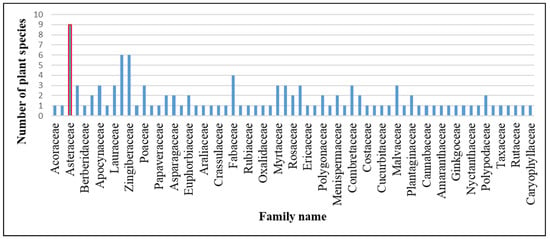

From the three subdivisions of the Darjeeling District, a sum of 115 species of medicinal plants were recorded, which spread over 65 families and 104 genera. Here, a total of 93 plant species belonged to dicots, 17 species were from monocots, 3 species were pteridophytes, and only 2 species were listed from gymnosperms (Table 2). The Asteraceae family had nine species, the highest number of species recorded, which covered 7.9% of the total number of species listed in the present study. The second largest families with respect to recorded species were Lamiaceae and Zingiberaceae, with six species and 5.3% of the total number of recorded species in each of these two families. The Fabaceae ranked the third largest family, with a total of four species, which represent 3.6% of the total species recorded. Each of the seven families with three species, accounting for 2.6% of total species, belonged to the families Amaryllidaceae, Apocynaceae, Lauraceae, Poaceae, Malvaceae, Myrtaceae, Piperaceae, Urticaceae, and Combretaceae. Each of the eleven families of Saxifragaceae, Solanaceae, Asparagaceae, Euphorbiaceae, Polypodiaceae, Phyllanthaceae, Plantaginaceae, Rosaceae, Polygonaceae, Apiaceae, and Menispermaceae represented two species, accounting for 1.7% of the total plant species recorded. The remaining 41 families had single-species representation, constituting 19% of the total noted species for each family (Figure 1).

Table 2.

Families, genera, and species of the recorded medicinal plants.

Figure 1.

Number of plant species in respective families.

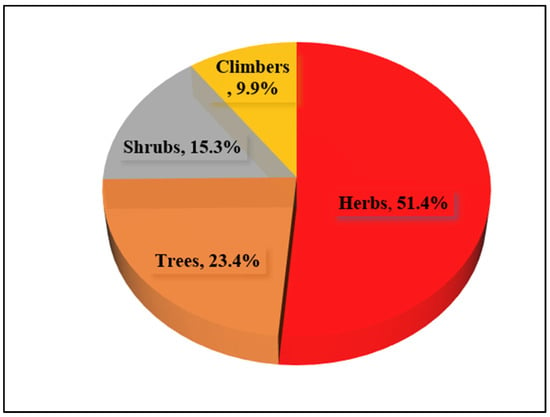

The reported plant taxa are classified into four categories based on their habits, namely, herbs, shrubs, climbers, and trees. From the present study, the herbs contributed the highest number of species, 57, which shared 51.4% of the reported taxa. Trees represent the second largest group, with a total of 26 species and 23.4% of total species recorded, followed by the shrub group, with 17 species (15.3%), and climbers, with 11 species (9.9%) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Habits of medicinal plants in the study area.

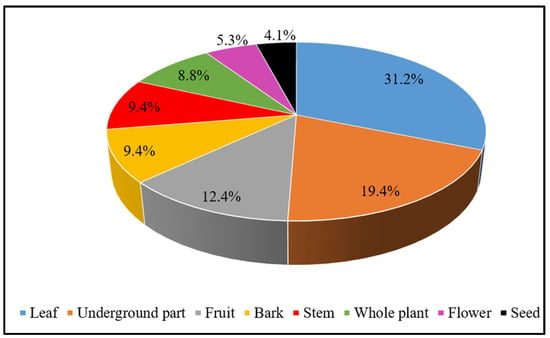

2.4. Plant Part(s) Used as Crude Drugs

Different parts of the recorded medicinal plants are used as crude drugs by the local people of the study area. The leaf was found to be the most used plant part in the current study, accounting for 31.2% of the ethnomedicinal formulations recorded, followed by underground parts like the root, rhizome, and bulb, which were used in 19.4% of the formulations. Fruits were used in 12.4% of the formulations, the bark and stem were used in 9.4% each, the whole plant was used in 8.8%, the flowers were used in 5.3%, and the seeds were used in the preparation of 4.1% of the total reported formulations (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Plants parts used in herbal preparations.

2.5. Disease Categories

Based on the disease classification by the International Classification of Primary Care [16] of the World Health Organization (WHO), the documented 50 types of diseases have been assembled into 11 disease categories, which are (1) pregnancy, childbearing, and family planning, (2) digestive, (3) cardiovascular, (4) skin, (5) urological, (6) general and unspecified, (7) musculoskeletal, (8) respiratory, (9) endocrine/metabolic and nutritional, (10) blood, blood-forming organs, and immune mechanism, and (11) eyes. In the current study, it was noticed that the highest number of medicinal plant species, 23 species, were used in healing digestive diseases. For cardiovascular diseases, 18 species were employed, followed by 14 plant species administered for treating skin diseases, 12 plant species applied against general and unspecified diseases, and 8 species used for treating musculoskeletal problems. The lowest number of medicinal plant species, two species, was recorded for the category of pregnancy, childbearing, and family planning.

2.6. Procurement, Formulations, and Methods of Preparation of the Crude Drugs

Fresh plant materials sourced from wild and home gardens were utilized by the inhabitants of the studied area for preparing various herbal formulations. Among the 115 recorded species, 86 plant species were grown in the wild. This demonstrates the abundance of therapeutic plants in the natural habitat and also highlights the local people’s reliance on wild plant sources. In addition, crude herbal materials were procured by the local people from 29 species grown in their home gardens.

To treat 50 different kinds of diseases, a total of 122 formulations were administered. Among the recorded formulations, 101 formulations were monoherbal, and the remaining 21 formulations were polyherbal, which were prepared using more than one herbal species. Different parts of the 91 plant species are used for the preparation of 101 monoherbal formulations, and a total of 41 species are employed in preparing 21 polyherbal formulations. In the monoherbal group, nearly 10 species are employed in preparing more than one remedy administered for treating two or more ailments. Similarly, 10 species have been identified from the polyherbal group, which are used in the preparation of more than one formulation. There are 17 species commonly found in both mono- and polyherbal preparations (Table 3). When analyzing the various medicinal uses of the recorded 115 species, it was noticed that 28 species have multiple therapeutic uses. Each species has a minimum of two and a maximum of four types of uses for therapeutic purposes (Table 4). The larger part of the therapeutic formulations (81%) was constituted using fresh herbal ingredients. Some remedies were prepared entirely from dried plant materials (16.5%), while 2.5% of formulations were made of either air-dried or freshly harvested plant components, depending on their availability in the study area.

Table 3.

List of plant species used in both monoherbal and polyherbal formulations (n = 17).

Table 4.

Plant species with multiple therapeutic uses (n = 28).

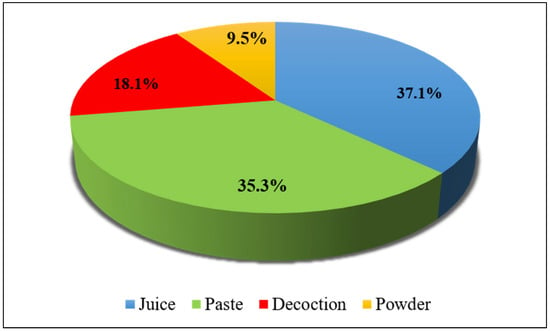

It was noticed that respondents in the study area used numerous methods of recipe preparation. Four different methods were employed for the preparation of remedies. The most common method of medicine preparation was juice (37.1%), followed by paste (35.3%), decoction (18.1%), and powder (9.5%) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Methods of preparation of ethnomedicine.

The recorded medicinal plant species were tabulated and presented alphabetically, followed by their family name, voucher number, vernacular name, diseases treated, plant part(s) used, mode of preparation, and method of administration in two separate tables in terms of monoherbal and polyherbal formulations (Table 5 and Table 6).

Table 5.

List of ethnomedicinal plant species used for preparing the monoherbal formulations (n = 91).

Table 6.

List of polyherbal formulations and ethnomedicinal plant species used (n = 21).

2.7. Routes of Administration of Ethnomedicine and Doses

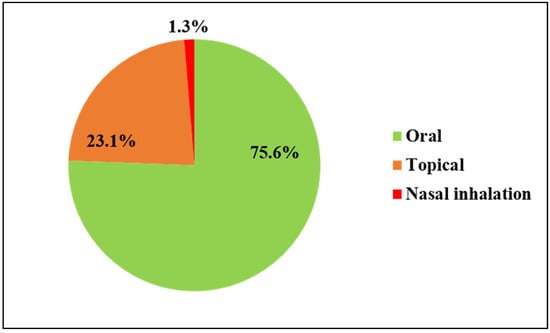

Around 75.6% of medications were administered orally. The root, bark, and leaf of certain plant species were boiled, and the decoction was consumed orally to heal diseases like diarrhea, body aches, fever, cough, throat pain, and others. Topical methods, such as massage, poultice, paste, and so on, were applied to treat various types of ailments, like bone fractures, skin problems, snakebites, cuts, etc. (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Route of administration of ethnomedicine.

The informants utilized their traditional system of measurement for measuring the amounts of drug components and doses of crude drugs with the help of teaspoons, cups, pinches, fingers, etc. This age-old technique of measurement is significantly supportive to traditional herbalists in measuring the amounts of plant resources needed for the preparation of medication and defining the precise dosages to be given to a patient for effective treatment [17]. However, dosages varied from disease to disease, as well as due to other factors, like the gender, age, and health condition of the patient.

2.8. Quantitative Analysis of the Ethnomedicinal Data

Quantitative ethnobotanical indices offer organized and quantifiable information on the traditional uses of medicinal plants, which are crucial to ethnopharmacology research. Based on the frequency and range of the applications of plants in traditional medicine, these indices provide a structured method for measuring their significance in the health care system and utilitarian culture of a society. The quantitative indices offer statistically analyzed data that enhance the credibility of the documented information needed for drug discovery. In this context, the ethnomedicinal data of the present study were collected and analyzed utilizing suitable quantitative indices, such as the informant consensus factor (Fic), fidelity level (FL%), and use value (UV).

2.8.1. Informant Consensus Factor (Fic)

Fic is a highly favored quantitative tool used in ethnobotanical studies to indicate the plants that are utilized with higher to lower levels of accord among the informants to treat the diseases in a certain disease category [16]. The Fic values of 11 recorded disease categories ranged between 0.56 and 0.87. The digestive diseases had the highest Fic score of 0.87 among the eleven disease categories. It indicates that there is the highest degree of concurrence of digestive system diseases among the inhabitants of the study area. A total of 23 plant species are used for treating this diseases category. The smallest Fic value was calculated in the case of endocrine/metabolic and nutritional diseases (0.56). Here, pregnancy, childbearing, and family planning gained a Fic value of 0.83, followed by a Fic value of 0.82 estimated for urological diseases. In these two categories of diseases, a high level of agreement among the informants is evident regarding the uses of the cited species of medicinal plants. The categories of respiratory and eye diseases had equal Fic values of 0.78, followed by the category of general and unspecified diseases (0.72), etc. (Table 7).

Table 7.

Informant consensus factor (Fic) for each disease category.

2.8.2. Fidelity Level (FL%)

The FL% value of the 91 noted plant species ranged between 29% and 97%. The highest FL% value (97%) was documented for one plant species, Betula alnoides Buch.-Ham. ex D.Don. The bark paste of this plant is topically applied for treating snakebites, inflammation, cuts, and wounds. The lowest value for FL% was 29%, which was calculated for the plant Mallotus philippensis (Lam.) Müll. Arg. The bark decoction of this medicinal plant is taken orally for treating piles (Table 6).

2.8.3. Use Value (UV)

The UV index values for the recorded 91 species of medicinal plants varied from 0.02 to 0.97. Hellenia speciosa (J.Koenig) S.R. Dutta exhibited a use value of 0.97, which is the highest among the studied 91 species. Traditionally, the stem juice of this plant is taken orally to cure urinary troubles and jaundice. On the other hand, Scadoxus multiflorus (Martyn) Raf. scored the lowest use value, which was 0.02. The bulb paste of this plant is applied topically for treating mumps (Table 6).

2.9. Quantitative Estimation of Phenolic, Flavonoid, and Tannin Contents of B. alnoides Bark

Phenolics are widely acclaimed for their broad-spectrum pharmacological properties. The total phenolic content of the methanolic extract of B. alnoides bark was estimated to be 87.8 ± 2.5 mg gallic acid equivalent (GAE)/g dry tissue. This result was obtained from a calibration curve (y = 0.0199x − 0.064, R2 = 0.994) of gallic acid. The total flavonoid and tannin contents of the bark extract were estimated to be 30.1 ± 1.5 mg catechin equivalent (CE)/g dry tissue (y = 0.017x + 0.012, R2 = 0.9973) and 10.37 ± 0.51 mg tannic acid equivalent (TAE)/g dry tissue (y = 0.403x + 0.0419, R2 = 0.992), respectively.

2.10. HPLC Analysis of the Bark Extract

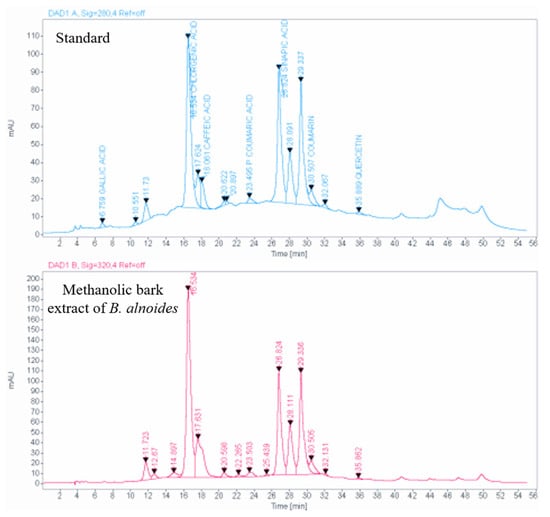

In this experiment, a total of six phenolic compounds have been identified from the B. alnoides bark, and the quantification of each of those six compounds has been made using the HPLC technique. Among the six identified compounds, the most abundant compound was chlorogenic acid, with a concentration of 117.5 mg/g of extract, followed by sinapic acid at 64.7 mg/g of extract. Caffeic acid was also present but in a lower amount of 5.8 mg/g of extract. Additionally, coumarin was present at a concentration of 1.5 mg/g of extract, p-coumaric acid at a concentration of 0.4 mg/g of extract, and gallic acid at a very minimal concentration of 0.1 mg/g of extract (Table 8; Figure 6).

Table 8.

Contents of phenolic compounds identified in methanolic bark extract of B. alnoides and their reported biological activities.

Figure 6.

HPLC chromatogram obtained from methanolic bark extract of B. alnoides.

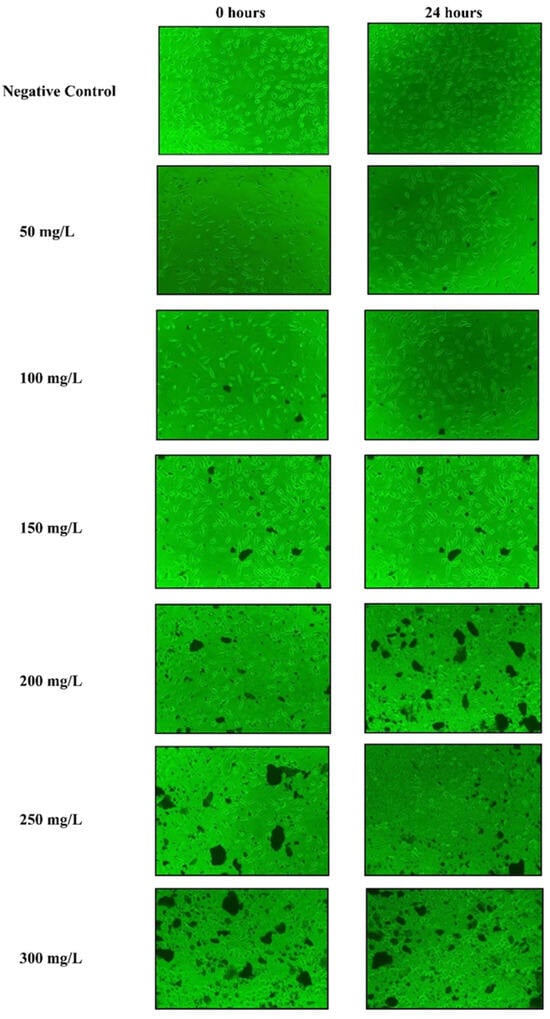

2.11. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assay

The methanolic bark extracts of B. alnoides were tested at concentrations ranging from 50 to 300 mg/L employing the MTT assay, and the impact on the cell line was evaluated after 24 h of cell exposure to the extracts. The results demonstrated a concentration-dependent increase in cell mortality, with percentages of 10.8 ± 0.45% at 50 mg/L, 21.08 ± 0.51% at 100 mg/L, 31.03 ± 0.49% at 150 mg/L, 40.21 ± 0.66% at 200 mg/L, 45.11 ± 0.74% at 250 mg/L, and 54.17 ± 0.57% at 300 mg/L (Supplementary Table S2). Toxic effects were observed at all concentrations higher than 100 mg/L, as indicated by a change in cell morphology from its typical spindle shape to an oval shape (Figure 7). A statistical analysis revealed a significant positive correlation (p < 0.05) between extract concentration and cell mortality, with a clear revelation of increasing cell mortality percentage with respect to enhancing the extract concentration. A non-linear regression analysis estimated the CC50 value of the methanolic bark extract to be 270.07 ± 1.32 mg/L, highlighting the potent effects of the extract on cell viability.

Figure 7.

Micrographs showing the morphological changes in the L929 mouse fibroblast cells before and after 24 h exposure to different concentrations (50–300 mg/L) of B. alnoides bark extract, along with negative control.

3. Discussion

The interaction between humans and plants is an inevitable aspect of the biological world. For centuries, humans have relied on plants as primary sources of food, shelter, and therapeutic medicaments. The age-old practices of utilizing medicinal plants and their diverse applications in treating various health problems have been deeply ingrained within indigenous cultures of mankind worldwide. The current study documented the therapeutic utilities of 115 species of vascular plants, which spread across 65 families of angiosperms, gymnosperms, and pteridophytes from the rural areas of the Darjeeling District of West Bengal. A total of 101 monoherbal formulations and 21 polyherbal formulations were recorded, and both types of formulations were prepared by the local people using plant ingredients from 115 species. This amply illustrates the diversity of folk herbal knowledge and the abundance of ethnomedicinal plants in the current study area. A thorough analysis of various therapeutic uses of all the recorded 115 medicinal species revealed that a total of 28 species have multiple uses, ranging from two to four therapeutic purposes. These 28 species of medicinal plants constitute an indispensable phytoresource in the locality, which needs a sustainable management strategy for its restoration and judicious utilization.

From our ethnomedicinal survey, it became evident that Asteraceae has the highest representation, with nine species utilized by ethnic groups in the studied area. This aligns harmoniously with many prior ethnomedicinal studies, which consistently highlight the prevalence of Asteraceae species in traditional medicinal practices [32,33,34]. Bidens pilosa, from the family Asteraceae has historically served as a remedy for liver ailments and hypertension in Taiwanese folk medicine [35]. However, within our surveyed region, the plant finds application in the treatment of skin infections through the topical application of its leaf paste. In the Nigerian traditional medicine of Africa, Ageratina adenophora is renowned for its efficacy in managing fever, diabetes, and inflammation [36]. Conversely, in our study, herbal medicine practitioners advocate for the oral administration of its leaf juice to cure piles. These poly-pharmacological properties of the species belonging to the Asteraceae family have been attributed to their medicinally potent phytochemical components, including essential oils, lignans, saponins, polyphenolics, sterols, and some polysaccharides [37]. The multifaceted bioactive compounds, pharmacological properties, and abundance may account for the extensive utilization of the Asteraceae family in medicinal practices in the area. The second highest number of species documented in the present study is from the families Zingiberaceae and Lamiaceae, each representing six species. The abundance in the locality and therapeutic efficacy made the recorded species of these two families a suitable choice of use by the local people as crude drugs in their traditional medicine. The therapeutic performances of such plant species of Zingiberaceae and Lamiaceae may be explained by the scientific evidence reported earlier on their bioactivity-related phytochemical profiles, which include medicinally important chemical groups such as phenolics, flavonoids, tannins, saponins, triterpenoids, essential oils, and alkaloids [38,39,40].

This study also clarifies that local people of the current investigated region mostly use herbs (51.4%), among other life forms of the recorded plants, to treat a range of illnesses. The possible explanation for employing herbs in maximum numbers is that herbs are grown exuberantly in the area and are easily accessible [41]. Herbs are also easier to harvest than trees and other woody species since they are smaller and have a shorter height. It is a fact that individuals are more likely to explore plants for food and pharmaceutical items that are procured effortlessly and are available abundantly and in nearly all seasons of the year [42]. These factors have led to a significant proportion of herbaceous plants being utilized as therapeutic agents in nearly all traditional medical systems, including ethnomedicine worldwide.

The ethnomedicinal practices mostly rely on plants that grow in the wild. All ethnic tribes continue to use native wild plants extensively, and traditional medicinal practices are mostly based on these plants [43,44]. In the present study, a major portion of the medicinal ingredients (74.7%) were acquired by local people from the plant communities grown in the wild.

The present study concludes that respondents mostly favor the usage of leaves (31.2%), followed by underground parts (19.4%), to prepare their herbal medications. Leaves are mostly preferred, as they are available almost year-round and more easily harvestable than other parts of the plant, such as flowers, fruit, seeds, bark, and sometimes, roots. It has also been demonstrated in a number of previous studies all around the globe that leaves are the ingredient most frequently used to prepare traditional remedies for the treatment of different illnesses [45,46,47]. Ethnic herbalists mostly rely on leaves because the foliage of medicinal plants synthesizes and often stores a variety of therapeutically beneficial phytochemicals, which include vitamins, minerals, alkaloids, phenolics, tannins, terpenoids, and others [48].

The present study shows that among 50 types of diseases recorded, the most common type is digestive disease. Many digestive diseases, such as diarrhea, jaundice, liver problems, flatulence, and stomach discomfort, have been seen as prevalent in this area, likely due to variations in lifestyle, lack of proper hygiene, unsafe drinking water, types of food, including leafy green items, consumed, and the compatibility of these foods with individual digestive systems. In various previous studies, digestive diseases like flatulence, indigestion, dyspepsia, and constipation have been documented as predominant health problems in India and all around the globe [49,50,51].

The informants in this district use various methods of preparation of remedies to treat diseases. Based on the aforementioned results, it has been concluded that the most common technique of preparing remedies is juice (37.1%), in comparison to other methods, such as pastes (35.3%), decoctions (18.1%), and powders (9.5%). Due to its effectiveness and ease of preparation, juice may be favored in most of the folk medicine system [52]. Additionally, juice may have a greater concentration of active ingredients compared to other preparations of remedies like decoctions, powders, and sometimes, pastes [53]. This is because preparations other than juice are prepared through heat-aided processes, such as boiling, drying, etc., that can degrade, to some extent, many of the chemical compounds present in the crude drugs. Thus, juice retains the exact amounts of the beneficial chemical compounds that make it more efficacious. The application of juice as a remedy in a significant or higher percentage in comparison to other preparations has been reported in many previously published research publications on ethnobotany [54,55].

The efficacy potential of remedies is higher when they are prepared by employing freshly collected plant ingredients than when they are prepared from dried crude drugs. Bioactive compounds in crude drugs can undergo thermal degradation when exposed to high temperatures during boiling, or the photosensitive compounds may undergo photolytic degradation once the crude plant materials are exposed to sunlight during the drying process. Furthermore, a lack of care during drying may lead to microbial growth, resulting in spoilage of the crude drug and denaturation of its certain chemical ingredients. Therefore, fresh materials are preferred for preparing remedies to ensure maximum potency and safety. The fact that materials in both fresh and dried forms are utilized in the preparation of ethnomedicine increases the likelihood that informants will have year-round access to the ingredients used in herbal formulations.

In the present study, it was noted that the oral route of remedy administration is more prevalent (75.6%) than other routes, like topical (23.1%) and nasal inhalation (1.3%). Similar to this study, numerous previous investigations have highlighted that in the majority of cases, folk medicaments are administered through the oral route [43,56,57]. Oral administration is usually practiced, as it makes it convenient to use and consume the medicine, and it is more effective. Along with oral administration, topical application remains an important method of herbal drug administration to cure ailments such as wounds, skin diseases, and body pain. Topical use, specifically poultice, enhances blood circulation in the affected areas and provides a protective layer, shielding infected wounds or sores from further microbial infection. Additionally, the herbal ingredients in the poultice contain antiseptic essential oils, phenolics, tannins, and other bioactive chemicals that penetrate the dermal tissues, aiding in the fight against microbial infection and reducing inflammation. This ultimately promotes wound healing [41].

The informant consensus factor (Fic) is assigned to measure the consensus of informants regarding the uses of the plants in a particular disease category. In the present study, digestive diseases had the highest Fic value (0.87), which adheres to the similar trend of the highest Fic value being estimated to be 0.95 for the digestive disease category in another previous study [58]. Other categories of diseases with higher Fic values in this region are pregnancy, childbearing, and family planning (0.83), followed by urological diseases (0.82). Similar results with high Fic have been encountered for these disease categories in some earlier reports [5,59]. The lowest Fic value (0.56) was calculated in the case of the endocrine/metabolic and nutritional disease category. The low Fic suggests lesser consensus among the informants regarding the use of medicinal plant taxa in this disease category.

The analysis of Fic data reveals that digestive system disorders are the most prevalent disease category in the region, with 23 plant species used to treat 11 types of complications associated with the digestive system, including stomach pain, gastrointestinal infection, diarrhea, flatulence, and gas problems. The use of these plants for treating digestive disorders in this region can be attributed to their rich phytochemical compositions and biological activities, which are validated by the existing literature.

Acorus calamus, one of the 23 plant species used to treat digestive disorders, has shown promising potential in treating gastrointestinal disorders due to its high contents of phenolic compounds like chrysin and galanginin, plant extracts that have been evaluated by earlier works. The pharmacological studies indicate that both methanol and water extracts (15 mg/kg) significantly reduce diarrhea in mice by inhibiting Na+ K+ ATPase activity. Additionally, the ethanol extract (500 mg/kg) has demonstrated anti-ulcer activity in mice by inhibiting acid secretion in the stomach [60,61]. Similarly, drug parts of the plants Cymbopogon citratus and Kaempferia galanga are found to be very common ingredients in the remedies used by the local people of the surveyed areas for healing diarrhea, stomach pain, and flatulence. Research has confirmed that citral, a monoterpenoid from Cymbopogon citratus, and kaempferol, a flavonoid from Kaempferia galanga, possess potent anti-inflammatory, antidiarrheal, and antioxidant properties, which justifies the inclusion of these medicinal plants in the disease category of digestive system disorders [62,63]. Moreover, Houttuynia cordata, a notable therapeutic remedy included in the plant list of digestive disease groups used for jaundice, has been established as an effective hepatoprotective agent by checking its ability to prevent CCl4-induced liver damage in mice by restoring the damaged hepatocytes. The hepatoprotective activity of this plant may be related to the presence of various antioxidant molecules of the polyphenolic group, namely, quercitrin, quercetin, rutin, hyperin, isoquercitrin, β-myrcene, β-pinene, α-pinene, α-terpineol, and n-decanoic acid, identified through phytochemical analysis [64]. A critical review of their phytochemical composition and biological activities suggests that most of these ethnomedicinal species contain therapeutically effective phytochemicals, justifying their traditional uses in addressing various disorders associated with the digestive system

On the basis of the score of the use value index (UV), Hellenia speciosa (J.Koenig) S.R.Dutta has been identified as having the highest use value, 0.97, among 91 species, which highlights the frequent use of this species in multiple disease conditions, i.e., for urinary troubles and jaundice. The lowest score was calculated for Scadoxus multiflorus (Martyn) Raf., which was 0.02. Such a low UV score for this plant illustrates that it is used infrequently for the least number of diseases; in this study, it is used for curing only one health condition, mumps. Many ethnobotanical studies employing quantitative indices, including the use value index, documented the higher to lower range of UV scores elucidating the degrees of importance of medicinal plant species with regard to their therapeutic uses [43,65].

The fidelity level (FL%) is a useful quantitative tool to determine the most beneficial plant species used for treating a certain disease. A higher percentage of fidelity level (FL%) can show that the utilization of a plant for specific therapeutic purposes is preferred if respondents cited it regularly. Plants with high FL% values become the torchbearers, leading us on a journey of scientific discovery through phytochemical studies to identify the bioactive compounds that are accountable for their exceptional therapeutic properties, as well as to validate the traditional claims on the medicinal uses of those species [66]. Over the course of our fidelity level analysis, Betula alnoides Buch.-Ham. ex D.Don emerged as the ethnomedicinal plant with the highest FL% of 97% among the 91 studied species, which indicates its excellent therapeutic potentialities. Recognizing that it is an exceptional attribute, we have embarked on studies of the phytochemical properties and cytotoxicity profile of Betula alnoides bark.

Almost all the previous studies from the Darjeeling District of West Bengal have documented the ethnobotanical knowledge on the traditional therapeutic uses of plant resources, without quantitative analyses of the collected data using dedicated ethnobotanical indices [6,7,8]. Notably, only one ethnomedicinal work from the Teesta Valley of the Darjeeling District employed quantitative indices like the informant consensus factor, fidelity level, and importance value in the analysis of data on ethnomedicinal plants [10]. In contrast, the novelty of the present study is that it focuses on the documentation of medicinal plant resources from three subdivisions of the Darjeeling District after analyzing the recorded information utilizing the quantitative indices of use value index, alongside the fidelity level and informant consensus factor, to measure the utilitarian significance and elucidate the usage patterns of the phytotherapeutics.

The present comprehensive documentation of folk herbal knowledge from the Darjeeling District underscores the vital importance of preserving the traditional wisdom of the district and harnessing its therapeutic potential to develop modern medicine. This research reveals the district’s remarkable ethnobotanical plant richness, cataloging 115 plant species that are integral to the traditional healing practices. Among the documented 115 plant species, a significant number of 103 species have been studied to some extent for their bioactivities, as well as their phytochemical profiles. This indicates a great promise of the documented phytoresources for further scientific investigation toward the development of a varied range of natural products. Notable examples of these species include Achyranthes aspera, Bergenia ciliata, Bidens pilosa, Berberis napulensis, Datura stramonium, Kaempferia galanga, Oroxylum indicum, Euphorbia hirta, Phyllanthus emblica, and many more. For instance, Achyranthes aspera exhibits significant anti-inflammatory and antioxidant effects [67], while Berberis napulensis has been found to be effective in cardiovascular, metabolic, hepatic, and renal disorders due to the presence of the alkaloid berberine [68]. Kaempferia galanga shows both wound healing and anti-inflammatory activities [69], and Oroxylum indicum is noted for its broad range of bioactivities, such as antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, anticancer, and anti-ulcer bioactivities, and many more [70]. In addition to these, a number of pharmacologically well-studied medicinal plants have also been documented from the Darjeeling District, including Moringa oleifera, Catharanthus roseus, Calotropis gigantea, and others. Moringa oleifera is known for its antioxidant [71], anti-inflammatory [72], and antimicrobial properties [73], with its bioactive compounds widely utilized in various health products, such as energy drinks (e.g., Zija’s Moringa-based XM3) and supplements (e.g., Kuli Kuli’s Moringa-infused energy bars). Catharanthus roseus is a vital source of potent anticancer alkaloids, vinblastine, and vincristine used in a broad range of cancer diseases [74], while Calotropis gigantea is revered for its hepatoprotective and wound healing properties [75], with its extracts used in topical ointments for wound care [76]. However, twelve species were found unexplored for their phytochemical and pharmacological evaluation among the documented species in this study. These twelve plant species, like Allium rhabdotum, Entada gigas, Hydrangea febrifuga, Hydrocotylehimalaica, Hedychium spicatum, and Pseudognalium affine, provide exciting avenues for scientific exploration toward natural product development. Targeted phytochemical analyses, bioactive compound isolations, and pharmacological evaluations of these underexplored species could unlock their full array of therapeutic potential for the development of health-promoting products.

There are several studies detailing the phytochemical and pharmacological aspects of many folk medicinal plants from the Darjeeling District in which Betula alnoides has not been considered [77,78,79]. Some studies have explored various phytochemical groups, including the terpenoids, phenolics, and flavonoids of Betula utilis and B. pendula [80,81]. Only one study focuses on the quantification and chemical structure elucidation of a triterpenoid compound named lupeol isolated from B. alnoides bark [82]. The present research, however, quantified a total of six phenolic compounds from B. alnoides bark through the HPLC technique. A quantitative phytochemical analysis highlights the bark of B. alnoides as a rich source of phenolics and flavonoids. The phenolic content of B. alnoides bark was estimated to be 87.8 ± 2.5 mg GAE/g of dry tissue, which is greater than the phenolic contents of the bark of many well-recognized medicinal plants, like Acacia nilotica (80.6 mg GAE/g dry tissue), Acacia catechu (78.1 mg GAE/g dry tissue), Senna tora (65.5 mg GAE/g dry tissue), and Cassia fistula (22.8 mg GAE/g dry tissue) [83]. Our study also estimated the total flavonoid content in the bark of B. alnoides, and it was 30.1 ± 1.5 mg CE/g of dry tissue. The total content of flavonoids in B. alnoides bark is found to be almost two times higher than the total flavonoid content, i.e., 15.1 mg CE/g of dry tissue of bark of Terminalia arjuna, which is an important medicinal plant [84]. The bark extract showed a substantial tannin content of 10.37 ± 0.51 mg TAE/g of dry weight. As we documented earlier, during our ethnomedicinal survey, the ethnic communities of the Darjeeling District traditionally use the bark of the B. alnoides plant as an antivenom, anti-inflammatory, and wound-healing agent. Through phytochemical estimation, we have found that the bark of this plant possesses significant amounts of phenolics, flavonoids, and tannins, which are known to manifest a wide range of pharmacological activities, including antivenom, wound healing, and anti-inflammatory properties. Many research groups [85,86,87] have scientifically established that plant-sourced phenolic, flavonoid, and tannin compounds possess strong antivenom activity [88,89]. Numerous scientific reports have highlighted the effectiveness of flavonoids as wound-healing agents due to their high antioxidant and antimicrobial capacities [90]. There has been substantial evidence supporting the wound-healing potential of flavonoid-rich fractions of plants such as Tephrosia purpurea, Martyni aannua, Ononidis radix, and Eugenia pruniformis [91,92,93,94]. Tannins are also reported to facilitate wound healing due to their astringent properties, promoting wound tissue contraction, reducing microbial growth, neutralizing free radicals, and enhancing the growth of new blood vessels and fibroblast cells [95]. Scientific evidence that showcases the significant anti-inflammatory potential of phenolics, flavonoids, and tannins is abundant [96,97,98,99]. Therefore, the bark drug of our investigated plant possesses a very good amount of phenolics, flavonoids, and tannins, which qualifies it as a promising candidate for the development of effective anti-inflammatory and wound-healing agents.

Further, the HPLC study revealed the presence of six phenolic compounds. Among these, chlorogenic acid (117.5 mg/g dry tissue) and sinapic acid (64.7 mg/g dry tissue) have been identified in the highest quantities in the bark extract. The broad-spectrum therapeutic values of all six detected phenolic compounds are well-documented in the scientific literature (Table 8). Particularly, the presence of a substantial amount of chlorogenic acid in the bark extract of the studied plant justifies its antivenom and wound healing properties. Research findings provide evidence for the antivenom activity of chlorogenic acid through the inhibition of the neuro-myotoxic activity of the phospholipase A2 enzyme [19]. Research on the topical use of chlorogenic acid on wounds in Wistar rats has shown that it can enhance wound healing. Additionally, the antioxidant properties of this compound contribute to the healing effect too [20]. The bark of B. alnoides is rich in sinapic acid, which may contribute to the wound-healing activity of the plant. Gels containing sinapic acid promote the healing of wounds in Wistar rats through re-epithelialization and reducing oxidative stress [22]. The presence of six well-established anti-inflammatory phenolic compounds [23,25,28,30] in the bark of B. alnoides validates its use by the local tribes of the surveyed area for treating various inflammatory conditions in humans. Therefore, it can be concluded that the high contents of phenolic and flavonoid compounds and the presence of those six phenolic compounds in the bark of B. alnoides contribute to its therapeutic potential.

Like phytochemical studies, experimental works on the bioactivity of B. alnoides are very scanty. Only a few studies were conducted on certain bioactivities of the bark and stem of this plant. In one study, the bark demonstrated significant antioxidant, antimicrobial, and anti-inflammatory effects, which are attributed to its high polyphenolic content, including flavonoids and phenolics. In the same study, the bark shows α-glucosidase inhibition, suggesting its antidiabetic potential [100]. The stem of B. alnoides exhibited the anti-HIV-1 integrase and anti-inflammatory activities in another work, highlighting its promise for antiviral and inflammatory treatments [101]. However, to fully harness the plant’s therapeutic potential, future studies are to be carried out to investigate its varied types of bioactivities more comprehensively.

The earlier reports on traditional uses of other species of Betula have documented that leaves of Betula utilis are used for curing urinary tract infections [102], and B. pumila fruits are administered to treat respiratory tract diseases [103]. However, there is no such report regarding the medicinal uses of the leaf and fruit parts of B. alnoides in folk medicine. Given the medicinal importance of the leaf and fruit parts of other Betula species, there is potential for the leaf and fruit parts of B. alnoides to be explored as crude drugs by ethnic communities of the present study area, as well as other regions of the globe. Previous phytochemical studies on leaf parts of different Betula species highlight their rich phenolic content. For instance, the leaves of Betula pendula contain significant amounts of total phenolics (10.8 mg GAE/g dry tissue) and six phenolic compounds, namely, catechin, p-coumaric acid, myricetin, quercetin, and naringenin [104]. Similarly, Betula aetnensis leaf extracts are also abundant in phenolics and flavonoids [105]. Despite the established phytochemical richness in the leaves of various Betula species, studies have to be conducted on the leaf and fruit parts of Betula alnoides. Phytochemical exploration of these two parts of B. alnoides could disclose the hidden treasure of phenolics, flavonoids, and other polyphenolics, thereby expanding our understanding of the phytochemistry and therapeutic applications of this medicinal plant.

Despite the extensive ethnomedicinal claims and the presence of therapeutically significant phytochemicals, it is crucial to conduct systematic toxicity studies of this medicinal plant to predict potential toxicity risks and offer scientific evidence for ensuring the consumption of this drug in humans, as well as other animals. Our study is the first report on the cytotoxicity effects of B. alnoides bark against the L929 mouse fibroblast cell line, as no previous research has been performed to understand the cytotoxic effects of this plant. It was observed that the percentage of cell viability decreased with the increase in concentrations of the plant extract. When comparing the CC50 value of the methanolic bark extract of B. alnoides (270.07 ± 1.32 mg/L) to other medicinal plant extracts, it becomes clear that B. alnoides has moderate cytotoxicity. For instance, the CC50 value of the methanolic leaf extract of Azadirachta indica (neem) is reported to be approximately 200 mg/L, indicating a higher toxicity compared to B. alnoides [106]. Conversely, the methanolic extract of Moringa oleifera has a CC50 value of around 400 mg/L, suggesting it is less toxic than the cytotoxicity of B. alnoides bark [107]. These comparisons emphasize the relatively moderate cytotoxic nature of the B. alnoides bark extract. Therefore, the application of B. alnoides bark extract in a therapeutic context should be considered carefully, particularly at higher concentrations, to avoid potential cytotoxic effects. Further acute and long-term chronic toxicological studies are necessary to explore the underlying mechanisms of the toxicity and to ascertain the safe dosage range for its potential medical applications.

4. Materials and Methods

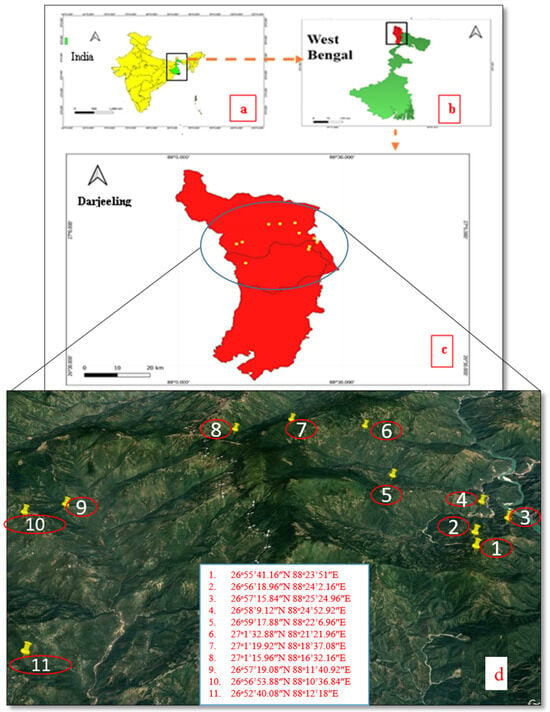

4.1. Study Area

The current study was conducted in three subdivisions of the Darjeeling District, namely, Kurseong, Darjeeling Sadar, and Mirik. In general, Darjeeling Himalaya falls under subtropical per humid climates, with daily mean temperature varying from 17 °C to 8 °C. The region receives 3372.75 mm of rainfall on an annual average [108]. This region spans between 26°57′16″ N and 88°25′2″ E and covers an area of 2090 km2. Numerous ethnic communities, including Tamang, Chettri, Lepcha, Rai, Limboo, and others, reside in this region. The Darjeeling District has 21.52% Scheduled Tribes and 17.18% Scheduled Castes [109].

4.2. Data Collection

The ethnomedicinal data were collected by surveying 11 villages under three subdivisions of the Darjeeling District using standard procedures by frequent field trips made in different seasons of the year during June 2022 and October 2023 [110,111]. The surveyed villages are Rolak, Lanku, Mungpoo, Rangaroon Tea Garden, Shelpu, Sittong, Phuguri, 6th Mile, Samripan, Tarzam, and Rungli (Figure 8). A total of 47 individuals (31 males and 16 females) were interviewed using a free listing, focus group discussion, and semi-structured questionnaire after communicating the goal of this study and its conclusion clearly to the interviewees in the local Nepali language using the purposive sampling method [112]. Free prior informed consent (FPIC) was taken from each of the informants before the interview in written form. The plants’ native names, plant parts used, preparation of the crude remedy, administration of the crude medication, ailments healed, and so forth were noted. The permanent addresses and locations of the residences of each participant were recorded using a global positioning system (GPS). The images of the plants and sociodemographic data were also recorded.

Figure 8.

Map (a–d). (a) Map showing the geographical location of West Bengal in India. (b) Geographical location of Darjeeling District in West Bengal. (c) The map of surveyed area. (d) Map depicting the various villages visited during the present study in Darjeeling District, West Bengal. (The map is created using Qgis software 3.10. and Google Earth Pro 7.3).

4.3. Collection of Plant Specimen and Herbarium Preparation

Herbarium specimens were prepared from the collected plant samples of the recorded species using the standard protocol [113]. The herbarium specimens have been stored at the departmental herbarium (Department of Botany, Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan, India) for future reference.

4.4. Identification and Nomenclature of the Plant Species

The plant species were identified with the help of different flora of the Darjeeling District and its adjoining regions [114,115,116]. Finally, species identification was confirmed by the expert taxonomists, Prof. Monoranjan Chowdhury from the Taxonomy of Angiosperms and Biosystematics Laboratory, Department of Botany, University of North Bengal, Darjeeling, West Bengal, and Prof. Chowdhury Habibur Rahaman from Ethnopharmacology Laboratory, Department of Botany, Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan, West Bengal, India. The nomenclature of the collected species has been updated using websites like Plants of the World Online (https://powo.science.kew.org/) and the World Flora Online (https://www.worldfloraonline.org/).

4.5. Data Analysis

4.5.1. Qualitative Data Analysis

The sociodemographic data of the informants were analyzed and documented in a table. All the recorded medicinal plant species were analyzed and grouped into various taxonomical categories. The recorded information on ethnomedicinal knowledge was tabulated and enumerated in tabular form along with the native name of the plant, updated scientific name, family, voucher specimen number, plant components utilized, diseases treated, technique of preparation of medicines, and the medicines’ administration with doses.

4.5.2. Quantitative Data Analysis

The following quantitative tools were employed.

Informant Consensus Factor (Fic)

Fic is a quantitative tool commonly applied in ethnobotany data analysis. It was first proposed by [117] and derived from the respondent agreement ratio equation, which was introduced by Heinrich et al. (1998) [118]. The Fic value ranges between 0 and 1. The Fic value assesses the maximum likely therapeutic plant species utilized by the informants for a particular disease category. A high Fic value indicates greater consent among the respondents about the plant species used for a group of diseases. The following formula was used to obtain the Fic value:

Fic = Nur − Nt/Nur – 1

Here, Nur denotes the number of use reports in each group, and Nt denotes the number of taxa (species) recorded.

Fidelity Level (%)

The fidelity level (FL) is the percentage of respondents who cite the use(s) of a specific plant species to cure a specific disease(s). It is used to assess the percentage of informants who assert the usage of a particular plant species for healing a specific disease, and it was calculated using the following equation:

where Np represents the number of interviewees who assert to use of a specific species to cure a particular ailment, and N represents the number of interviewees who use the plant as a medicine to cure any given disease. The highest FL% indicates that the plant species is applied recurrently and widely by the respondents to treat a specific health condition [119].

FL(%) = Np/N × 100

Use Value Index (UVs)

The use value index (UV) has been employed to determine the most recurrently utilized plant species [120]. The formula for determining the use value index for each species is .

Here, UV stands for the use value of species. U is the sum of the total number of use citations by all informants for a given species, and n is the total number of interviewees. A higher UV value designates the most utilized plant species and a lower UV value indicates the least utilized plant species.

4.6. Collection of Bark and Identification of the Plant

The fresh stem bark of Betula alnoides was collected on 22 October 2022 from an open forest near Lanku Valley of the Darjeeling District, West Bengal (23°31′56.4″ N and 87°30′36.8″ E), consulting the guidelines recommended by the National Medicinal Plants Board, New Delhi, India [121]. The identification of this collected species has been confirmed by consulting with different flora of Darjeeling and adjoining areas of West Bengal [114,116] and the expert taxonomist. The nomenclature of this plant has been made up-to-date following the standard website, such as Plants of the World Online (https://powo.science.kew.org/). The herbarium specimen has been prepared [110] and kept in the Herbarium of the Department of Botany, Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan, India, for future considerations [Voucher specimen number: INDIA, West Bengal, Darjeeling district, Lanku Valley forest, 15.11.2022, Y Subba 71 (VBYS 71)].

4.7. Preparation of Plant Extract

The collected bark of B. alnoides was washed thoroughly and then sliced into small thin pieces, shade-dried, and ground into fine powder. The plant powder was stored in an airtight vessel at 4 °C for future use. The bark powder of 10 g was extracted with 100 mL of methanol in a 250 mL conical flask keeping in a mechanical shaker at 28 ± 2 °C for 36 h. For a single extraction, the whole process was repeated three times. The resulting pull-out was mixed and filtered with Whatman’s No.1 filter paper. The filtrate was subjected to evaporation at room temperature (28 ± 2 °C). The ultimate yield was stored at 4 °C and dissolved in dimethyl sulfoxide (DMSO) to make the stock before use.

4.8. Quantitative Estimation of Phenolic, Flavonoid and Tannin Contents

The total phenolic content of the methanolic bark extract of B. alnoides was determined using the Folin-Ciocaletu method [122], while the total flavonoid content was estimated through the aluminum chloride colorimetric method [122]. The method of Afify et al. (2012) was employed to estimate the total tannin content [123].

4.9. HPLC Analysis of the Bark Extract

An HPLC device (Agilent 1260 Infinity II, Santa Clara, California, USA) equipped with OpenLab 2.7 data processing software (V2.7.) was used for the phytochemical analysis of the methanolic bark extract of B. alnoides. A reversed-phase column, Luna C18 (25 cm in length, 4.6 mm in inner diameter, and 5 μm in thickness) (Phenomenex, USA), was utilized for compound separation. The stock solutions (1 mg/mL) were prepared separately both for the standard and bark extract. The 1 mg of bark extract was combined with 0.5 mL of HPLC grade methanol and continuously sonicated for 10 min to prepare the stock solution. The overall volume of the mixture was made to 1 mL by adding the HPLC mobile phase solvent (which is a mixture of 1% aqueous acetic acid and acetonitrile in a 9:1 ratio). About 20 μL of the bark extract was introduced at a rate of 0.7 mL/min, and the temperature of the column was maintained at 28 °C during the analysis. For gradient elution, a variable percentage of solvent B (acetonitrile) to solvent A (1% aqueous acetic acid) was implemented. Within the initial 28 min, the ratio of gradient elution was altered linearly from 10% to 40% of solvent B, then from 40% to 60% of solvent B up to 39 min, and finally from 60% to 90% in 50 min. It required 55 min for the mobile phase’s composition to revert to its original state of solvent B/solvent A (10%:90%). It was then kept running for an additional 10 min before another sample was injected. The total time required to analyze each sample was approximately 65 min. Chromatograms of HPLC were recorded at three distinct wavelengths (272, 280, and 310 nm) using a photodiode UV detector. Based on the retention times and by matching with the applied standards, all of the phenolics and flavonoids were identified. A calibration curve was generated against various concentrations of the relevant standard samples in order to quantify the detected chemicals. Ten standards, including one flavonoid (kaempferol) and nine phenolic compounds (quercetin, chlorogenic acid, syringic acid, sinapic acid, catechin hydrate, caffeic acid, p-coumaric acid, coumarin, and gallic acid), were utilized for HPLC study.

4.10. In Vitro Cytotoxicity Assay

Using the 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay, the cytotoxicity test was conducted on the L929 mouse fibroblast cell line (sourced from the APT Research Foundation, Pune, India). Cells (104 per well) were seeded into a 96-well tissue culture plate. The plate was kept in an incubator for 24 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2. The test sample solution was prepared by dissolving the methanolic bark extract of B. alnoides in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM), with 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS). Wells containing cells with no extracts (DMSO only) were designated as a negative control. The prepared test sample solution was then added to each incubated well at different concentrations ranging from 50 to 300 mg/L and further incubated for 24 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2. After the incubation period, the plates were examined under an inverted microscope, to observe changes in cellular structure and photographs were taken. Then 10 µL of MTT reagent was added to each well of the plate and it was incubated for 4 h at 37 °C with 5% CO2. After the incubation period, the residual medium was removed, and 100 µL of solubilization buffer was added to each well. OD was taken at 630 nm using a 96-well plate reader. Each experiment was repeated three times. Cytotoxicity was analyzed using the following formula:

where A0 is the negative control’s absorbance, and At is the absorbance of the test sample solution.

CC50 (50% cytotoxicity concentration) value and the standard deviation (SD) were calculated using a non-linear regression curve obtained using Microsoft Excel, 2007.

5. Conclusions

The present study extensively documents a significant volume of indigenous herbal knowledge on medicinal plant resources which play a vital role in the health care of the local population in the Darjeeling District of West Bengal. The knowledge domain of ethnomedicine in the study region embodies about 115 plant species used in the forms of 101 monoherbal and 21 polyherbal formulations for therapies of 50 types of diseases. Our study amply elucidates the knowledge diversity of folk medicine in the district of Darjeeling and the richness of associated ethnomedicinal plant species with multiple therapeutic options.

One of the significant findings of this work is that among the 115 species, a total of 28 plant species with multiple medicinal uses have been found to be very promising for further chemical and bioactivity studies. Considering their multipurpose uses, such versatile species of medicinal plants should receive proper conservation and management attention to ensure their sustainable utilization. The present documentation will also be helpful to protect this valuable ethnomedicinal knowledge domain from its loss in the near future, as such herbal tradition remains in oral form, mostly among the senior members of the communities. The data presented in our work will enhance the ethnomedicinal database of this district, as well as the West Bengal state.

The quantitative indices offer statistically analyzed data on the medicinal uses of plants that amplify the credibility of the documented information crucial for bioprospecting and drug discovery. Analysis of the ethnobotanical data employing three quantitative indices measured the importance of recorded species in the herbal culture of the Darjeeling District, highlighting a good number of ethnomedicinal species with greater quantitative index values as the most significant and indispensable plant resources, for example, Betula alnoides (FL = 97%), Hellenia speciosa (UV = 0.92), and many others. Thus, the present study provides a big list of statistically analyzed important medicinal plants that show immense promise of being exploited for natural product discovery in the future.

A quantitative phytochemical analysis revealed a significant presence of phenolics and flavonoids in the bark of B. alnoides, highlighting its potential pharmacological benefits. The HPLC study further identified the bark of this plant as a noble source of chlorogenic acid and sinapic acid, as these two compounds were found in the greatest quantities among all six phenolic compounds identified. These phenolic acids, known for their broad pharmacological activities, including antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, wound healing, and antivenom properties, make the rationale to some extent regarding the traditional medicinal use of bark part of the investigated plant in snakebites, inflammation, cuts, and wounds. Furthermore, the MTT cytotoxicity study on the L929 mouse fibroblast cell line suggests that the bark extract of B. alnoides is likely to be moderately toxic, with a CC50 value of 270.07 ± 1.32 mg/L, and at higher concentrations, it may show cytotoxic effects. Future research efforts should focus on fractionating this bark extract to identify and isolate more bioactive compounds and conducting detailed toxicity studies to determine the safe dosage for potential applications. Utilizing advanced techniques such as molecular docking and in vivo studies will be crucial for fully elucidating the therapeutic potential of this highly potent plant.

There is no report on the uses of the leaf and fruit of B. alnoides for the healing of diseases. The tall height of mature trees (up to 30 m) of B. alnoides makes leaf and fruit collection very challenging, whereas bark is easier to harvest. While smaller trees and saplings of the plant offer access to leaves and fruits, the stem bark remains easily accessible; thus, it is the preferred plant part used for the preparation of traditional medicine. The herbalists and other users in the area ensure the sustainable use of the phytoresources, and while collecting the bark, they avoid ring-barking, which is a method that is detrimental to the plants, and instead collect small portions of the bark using a stripping method. So, sustainable collection practices are usually followed by the local inhabitants to protect the plant communities particularly the tree community in the area from the life-threatening harm caused by indiscriminate harvesting practices. During field surveys, a very scanty population of B. alnoides was noticed in some discrete patches, with few tree individuals in the area. The population decline of this plant in the area is mainly because of the cutting of the trees for timber. Therefore, conservation efforts should prioritize protecting the tree, given its multipurpose use. Proper conservation strategies should be undertaken to ensure the protection of this plant species from the rapid declination of its population.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/plants13243505/s1, Table S1: A list of the informants interviewed, along with the GPS coordinates of their residences and plant collection areas. Table S2: Mortality percentage and CC50 value of methanolic bark extract of B. alnoides against the L929 mouse fibroblast cell line.

Author Contributions

C.H.R., Y.S. and S.H. conceptualized and designed the present research work. Y.S. visited the study areas and collected all the information. Y.S. and S.H. interpreted and analyzed the data, prepared the figures and maps, and drafted the manuscript after consulting with C.H.R. C.H.R. critically reviewed and edited the manuscript, in addition to project administration, resource acquisition, and overall supervision. All the authors consented to submit their work to the present journal and approved the present version for publication. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All data are contained within the article.

Acknowledgments

The authors are grateful to all the tribal informants who shared their knowledge regarding the ethnomedicinal uses of various plants with us. This study would not have been possible without their active help and support. We also like to thank the Head of the Department of Botany (UGC-DRS-SAP and DST-FIST sponsored), Visva-Bharati, Santiniketan, for the necessary laboratory facilities. Two authors (Y.S. and S.H.) acknowledge the University Grant Commission, India, for financial assistance sanctioned in the forms of the UGC-NET JRF and non-NET Research Fellowship, respectively.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Khan, K.; Jan, G.; Irfan, M.; Jan, F.G.; Hamayun, M.; Ullah, F.; Bussmann, R.W. Ethnoveterinary use of medicinal plants among the tribal populations of District Malakand, Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, Pakistan. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2023, 25, 1–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adeniyi, A.; Asase, A.; Ekpe, P.K.; Asitoakor, B.K.; Adu-Gyamfi, A.; Avekor, P.Y. Ethnobotanical study of medicinal plants from Ghana; confirmation of ethnobotanical uses, and review of biological and toxicological studies on medicinal plants used in Apra Hills Sacred Grove. J. Herb. Med. 2018, 14, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekor, M. The growing use of herbal medicines: Issues relating to adverse reactions and challenges in monitoring safety. Front. Pharmacol. 2014, 4, 66193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pradhan, B.K.; Badola, H.K. Ethnomedicinal plant use by Lepcha tribe of Dzongu valley, bordering Khangchendzonga Biosphere Reserve, in north Sikkim, India. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2008, 4, 1–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamang, S.; Singh, A.; Bussmann, R.W.; Shukla, V.; Nautiyal, M.C. Ethno-medicinal plants of tribal people: A case study in Pakyong subdivision of East Sikkim, India. Acta. Bot. Sin. 2023, 43, 34–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rai, P.C.; Das, A.P. Ethnobotanical significance of the flora of Neora Valley National Park in the district of Darjeeling, West Bengal (India). Bull. Bot. Surv. India 2004, 46, 337–355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bantawa, P.; Rai, R. Studies on ethnomedicinal plants used by traditional practitioners, Jhankri, Bijuwa and Phedangma in Darjeeling Himalaya. Nat. Prod. Radiance 2009, 8, 537–541. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, S.K.; Bhujel, R.B. Survey of ethnoveterinary plants of Darjeeling Himalaya, India. Pleione 2013, 7, 508–513. [Google Scholar]

- Yonzone, R.; Lama, D.; Bhujel, R.B. Medicinal orchids of the Himalayan region. Pleione 2011, 5, 265–273. [Google Scholar]

- Subba, Y.; Hazra, S.; Rahaman, C.H. Medicinal plants of Teesta valley, Darjeeling district, West Bengal, India: A quantitative ethnomedicinal study. J. Appl. Pharm. Sci. 2023, 13, 092–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahaman, C.H. Quantitative Ethnobotany: Its Importance in Bioprospecting and Conservation of Phytoresources. In ETHNOBOTANY of INDIA-North-East India and Andaman and Nicobar Islands, 1st ed.; Pullaiah, T., Krishnamurthy, K.V., Bahadur, B., Eds.; Apple Academic Press Inc.: Ontario, CA, USA, 2017; pp. 269–292. [Google Scholar]

- Mandal, V.; Gopal, V.; Mandal, S.C. An inside to the better understanding of the ethnobotanical route to drug discovery-the need of the hour. Nat. Prod. Commun. 2012, 7, 1551–1554. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Su, X.Z.; Miller, L.H. The discovery of artemisinin and the Nobel Prize in Physiology or Medicine. Sci. China Life Sci. 2015, 58, 1175–1179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Fennell, C.W.; Lindsey, K.L.; McGaw, L.J.; Sparg, S.G.; Stafford, G.I.; Elgorashi, E.E.; Grace, O.M.; Van Staden, J. Assessing African medicinal plants for efficacy and safety: Pharmacological screening and toxicology. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2004, 94, 205–217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ndhlala, A.R.; Thibane, V.S.; Masehla, C.M.; Mokwala, P.W. Ethnobotany and Toxicity Status of Medicinal Plants with Cosmeceutical Relevance from Eastern Cape, South Africa. Plants 2022, 11, 1451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- International Classifcation Committee of Wonca. International Classification of Primary Care, revised 2nd ed.; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Cunningham, A.B. Applied ethnobotany: People, wild plant use and conservation; Earthscan Publication Ltd.: London, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Huang, J.; Xie, M.; He, L.; Song, X.; Cao, T. Chlorogenic acid: A review on its mechanisms of anti-inflammation, disease treatment, and related delivery systems. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1218015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Toyama, D.O.; Ferreira, M.J.; Romoff, P.; Fávero, A.O.; Gaeta, H.H.; Toyama, M.H. Effect of chlorogenic acid (5-caffeoylquinic acid) isolated from Baccharisoxyodonta on the structure and pharmacological activities of secretory phospholipase A2 from Crotalusdurissusterrificus. BioMed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 726585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, W.C.; Liou, S.S.; Tzeng, T.F.; Lee, S.L.; Liu, I.M. Effect of topical application of chlorogenic acid on excision wound healing in rats. Planta Med. 2013, 79, 616–621. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nićiforović, N.; Abramovič, H. Sinapic acid and its derivatives: Natural sources and bioactivity. Compr. Rev. Food Sci. Food Saf. 2014, 13, 34–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kaltalioglu, K. Sinapic acid-loaded gel accelerates diabetic wound healing process by promoting re-epithelialization and attenuating oxidative stress in rats. Biomed. Pharmacother. 2023, 163, 114788. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Espíndola, K.M.M.; Ferreira, R.G.; Narvaez, L.E.M.; Silva Rosario, A.C.R.; Da Silva, A.H.M.; Silva, A.G.B.; Vieira, A.P.O.; Monteiro, M.C. Chemical and pharmacological aspects of caffeic acid and its activity in hepatocarcinoma. Front. Oncol. 2019, 9, 541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Song, H.S.; Park, T.W.; Sohn, U.D.; Shin, Y.K.; Choi, B.C.; Kim, C.J.; Sim, S.S. The effect of caffeic acid on wound healing in skin-incised mice. Korean J. Physiol. Pharmacol. 2008, 12, 343–347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.J.; Jiang, J.G. Pharmacological and nutritional effects of natural coumarins and their structure–activity relationships. Mol. Nutr. Food Res. 2018, 62, 1701073. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adrião, A.A.; Dos Santos, A.O.; de Lima, E.J.; Maciel, J.B.; Paz, W.H.; da Silva, F.; Pucca, M.B.; Moura-da-Silva, A.M.; Monteiro, W.M.; Sartim, M.A.; et al. Plant-derived toxin inhibitors as potential candidates to complement antivenom treatment in snakebite envenomations. Front. Immunol. 2022, 13, 842576. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Afshar, M.; Hassanzadeh-Taheri, M.; Zardast, M.; Honarmand, M. Efficacy of topical application of coumarin on incisional wound healing in BALB/c mice. Iran. J. Dermatol. 2020, 23, 56–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aldaba-Muruato, L.R.; Ventura-Juárez, J.; Perez-Hernandez, A.M.; Hernández-Morales, A.; Muñoz-Ortega, M.H.; Martínez-Hernández, S.L.; Alvarado-Sánchez, B.; Macías-Pérez, J.R. Therapeutic perspectives of p-coumaric acid: Anti-necrotic, anti-cholestatic and anti-amoebic activities. World Acad. Sci. J. 2021, 3, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Selvakumar, G.; Lonchin, S. A bio-polymeric scaffold incorporated with p-Coumaric acid enhances diabetic wound healing by modulating MMP-9 and TGF-β3 expression. Colloids Surf. B Biointerfaces 2023, 225, 113280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Badhani, B.; Sharma, N.; Kakkar, R. Gallic acid: A versatile antioxidant with promising therapeutic and industrial applications. RSC Adv. 2015, 5, 27540–27557. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, D.J.; Moh, S.H.; Son, D.H.; You, S.; Kinyua, A.W.; Ko, C.M.; Song, M.; Yeo, J.; Choi, Y.H.; Kim, K.W. Gallic acid promotes wound healing in normal and hyperglucidic conditions. Molecules 2016, 21, 899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bouafia, M.; Amamou, F.; Gherib, M.; Benaissa, M.; Azzi, R.; Nemmiche, S. Ethnobotanical and ethnomedicinal analysis of wild medicinal plants traditionally used in Naâma, southwest Algeria. Vegetos 2021, 34, 654–662. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tugume, P.; Kakudidi, E.K.; Buyinza, M.; Namaalwa, J.; Kamatenesi, M.; Mucunguzi, P.; Kalema, J. Ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plant species used by communities around Mabira Central Forest Reserve, Uganda. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2016, 12, 5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Simbo, D.J. An ethnobotanical survey of medicinal plants in Babungo, Northwest Region, Cameroon. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2010, 6, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rolnik, A.; Olas, B. The plants of the Asteraceae family as agents in the protection of human health. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2021, 22, 3009. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chanu, K.D.; Sharma, N.; Kshetrimayum, V.; Chaudhary, S.K.; Ghosh, S.; Haldar, P.K.; Mukherjee, P.K. Ageratinaadenophora (Spreng.) King & H. Rob. Standardized leaf extract as an antidiabetic agent for type 2 diabetes: An in vitro and in vivo evaluation. Front. Pharmacol. 2023, 14, 1178904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Michel, J.; Abd Rani, N.Z.; Husain, K. A review on the potential use of medicinal plants from Asteraceae and Lamiaceae plant family in cardiovascular diseases. Front. Pharmacol. 2020, 11, 852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]