Abstract

This study analyzed the use of plants and fungi, some wild and some cultivated, in three municipalities of Lika-Senj County (Perušić, Gospić and Lovinac). The range of the study area was about 60 km. Forty in-depth semi-structured interviews were performed. The use of 111 plant taxa from 50 plant families and five taxa of mushrooms and fungi belonging to five families was recorded (on average 27 taxa per interview). The results showed quite large differences between the three studied areas in terms of ethnobotanical and ecological knowledge. In the Perušić area, (101 taxa mentioned), some people still use wild plants on a daily basis for various purposes. The most commonly noted plants are Prunus spinosa, Taraxacum spp., Rosa canina, Urtica dioica, Juglans regia and Fragaria vesca. In the Lovinac region, people used fewer species of plants (76 species mentioned). The most common species used there are: Rosa canina, Achillea millefolium, Cornus mas, Crataegus monogyna, Sambucus nigra and Prunus domestica. In the town of Gospić, the collection and use of plants was not so widespread, with only 61 species mentioned, the most common being: Achillea millefolium, Cornus mas, Sambucus nigra, Viola sp., Prunus domestica and Rosa canina. The medicinal use of herbal tea Rubus caesius and Cydonia oblonga against diarrhea was well known in the study area and is used medicinally, mainly in the rural parts of the Gospić area. The consumption of the Sorbus species (S. aria, S. domestica and S. torminalis) is an interesting local tradition in Perušić and Lovinac. Species that are difficult to find in nature today and are no longer used include: Veratrum sp., Rhamnus alpinum ssp. fallax, Gentiana lutea and Ribes uva-crispa. The use of Chenopodium album has also died out. We can assume that the differences in ethnobotanical knowledge between the three studied areas are partly due to minor differences in climate and topography, while other causes lie in the higher degree of rurality and stronger ties to nature in the Lovinac and Perušić areas. The most important finding of the study is the use of the parasitic fungus Taphrina pruni (Fuckel) Tul. as a snack. The use of Helleborus dumetorum for ethnoveterinary practices is also worth noting. The traditional use of plants in the study area shows many signs of abandonment, and therefore efforts must be made to maintain the knowledge recorded in our study.

1. Introduction

Traditionalist societies seek to preserve their traditional and cultural values, aiming to transfer them to posterity. Ethnobotanical studies can help in this task [1,2,3]. In the last few decades, we have often heard that traditional food is healthier than today’s new, quick cuisine. Together with the growing importance of natural and organic foods, the use of alternative products is increasing [1]. Some wild food plants (WFPs) are bioactive functional foods that can help people maintain health and fight against a number of diseases [4,5,6]. Besides, WFPs are rooted in conventional food knowledge, which is an important component of local and autonomous food systems [7].

Most botanical studies conducted in Croatia are focused on exploring floristic composition, vegetation and threatened and endemic species [8]. To date, some ethnobotanical research has been carried out in Croatia, mainly in the coastal or peri-coastal areas of the country [9,10,11]. However, further from the sea and at higher altitudes, only the area around Knin [12] in the region of Northern Dalmatia has been documented. No ethnobotanical research has been conducted on this topic in the Lika area, but in 2007, “Natural healing with herbs from the Lika-Senj county habitats”, a concise book on the topic, was published by Kate Milković [13].

According to Łuczaj et al. [14,15,16], the region of Dalmatia is very interesting from the point of view of ethnobotany, given the combination of Slavic and Mediterranean influence affecting the number of wild plants used in everyday life. Generally, peasants from Slavic countries used to resort to just a few of the commonest wild greens, ignoring other species [17]. There are some exceptions such as regions inhabited by southern Slavs, i.e., the inhabitants of Herzegovina [18] and the coast of southern Croatia—Dalmatia [19], who seem to have used an exceptionally high number of wild leafy vegetables in nutrition, as pointed out by Moszyński [20].

The evolving dynamics of ethnobotanical knowledge transmission have been found to be affected by different drivers, including political [21], historical, geographical and cultural differences [22] between rural and urban [23] and historical ethnogenic circumstances. As far as we know, throughout history, different invaders crossed paths in the central Lika region, which was located on the border between the Ottoman Empire and Europe (16th–17th century). Since the Iron Age, nomadism in the transhumance livestock economy of Lika was conditioned by its natural constitution (mountainous area and harsh climatic conditions), which prevented other economic activities, such as agriculture, from emerging. Therefore, livestock was necessary for sustenance [24,25]. Locals had very close connections to the mountain ecosystem they lived in. Throughout the entire Middle Ages, the Dinaric Vlachs were nomadic pastoralists who lived without permanent settlements and were tied to their herds [24,25].

The western regions of the Dinarides were inhabited by the so-called White Vlachs, whose name is derived from the white woolen clothes they wore.

The related Black Vlachs lived in the eastern areas of the Dinarides and wore black woolen clothes. Croats differed from the Vlach population in never having engaged in nomadic cattle breeding but always having lived in permanent settlements. White Vlachs, who lived around Velebit and Dinara in the Middle Ages, were Roman Catholics, while the Black Vlachs were partly Bogumili, and partly members of the Orthodox church. This situation was disrupted by the Ottomans, who reached Lika in the 16th century. Until the beginning of the 18th century, there were no major settlements located where the town of Gospić is today. The settlers who arrived here were mostly craftsmen and farmers of diverse origin: Christianized Muslims, Bunjevci and Catholics from the coast and upper Pokuplje (Bosnia and Herzegovina). During the period of Turkish settlement, Perušić enjoyed the reputation of an advanced and rich district center, a fortress guarded by soldiers and surrounded by populous villages. At the beginning of the 18th century, the Bunjevci and the Vlachs were settled in Lovinac and engaged in animal husbandry [25,26].

The people of Lika have always been poor and humble, surviving on “proja” (a traditional flatbread based on cornmeal or a mixture of different flours and eggs), sheep’s milk, cheese, potatoes, beans, cabbage, onions and bacon. Due to the high birth rate in the 19th century, Lika became the province with the most visible degree of emigration in Croatia, both to richer regions and overseas [24].

Since the traditional consumption of useful plants in the central Lika region has never been documented, the general aim of this study is focused on edible food and feed, medicinal plants, and ethnoveterinary uses, but also includes plants used for religious or traditional ceremonies and tools. The aim was also to contribute to the knowledge of plant biodiversity in the area.

2. Results

During the surveys, 1082 valid use records were collected, in which the respondents identified 111 plant species from 50 plant families and five taxa of mushrooms and fungi belonging to five families (Table 1). As many as 80 species of plants were collected only from the wild, 27 species were cultivated, and four species were both wild and cultivated.

Table 1.

List of documented wild and cultivated plant taxa used in central Lika region (continental Croatia).

The number of taxa per interview was between 15 and 49, with a mean of 27 taxa per interview (Median = 24, SD = ±8.3940). The most recorded taxa belong to Rosaceae (21) and Compositae (13) plant families. Some of the families were represented by only one or two species, but those species were frequently mentioned among respondents, such as the families Cornaceae (Cornus mas L., mentioned 33 times), Urticaceae (Urtica dioica L., 31 times) and Juglandaceae (Juglans regia, 30 times).

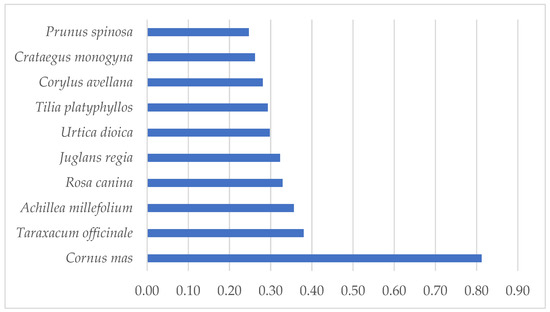

The most frequently mentioned taxon in the survey is Achillea millefolium L. (Figure 1), with relative frequency RFC = 0.925. The next two most frequent species are Rosa canina (RFC = 0.900) and Cornus mas (RFC = 0.825). A total of 10 taxa have absolute frequencies of 30 or more, while 40 were mentioned at least 10 times.

Figure 1.

Plants with the highest absolute frequencies (Frequencies > 30), N = 40.

Of the total of 111 plant taxa recorded, 47 were mentioned in all three survey localities, while 28 occurred in at least two localities. Some taxa were recorded only in one particular locality: Perušić—28 taxa, Lovinac—9 and Gospić—1. The similarity or correspondence (Jaccard Index) between the pairs of areas is JI = 57.14% for the pair Gospić–Lovinac, JI = 55.86% for the pair Lovinac –Perušić and JI = 54.37% for the pair Gospić–Perušić.

The most important plant species in relation to Smith’s S saliency indicator values are Rosa canina L. (Sj = 0.6725), Achillea millefolium (Sj = 0.6670), Cornus mas (Sj = 0.5627), Sambucus nigra L. (Sj = 0.5236) and Urtica dioica (Sj = 0.5050).

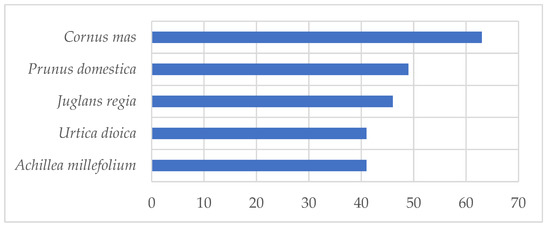

However, looking at the values of the cultural value coefficient (CVe), we find that the three taxa with the highest cultural value are Cornus mas (CVe = 0.812), Taraxacum spp. (CVe = 0.380) and Achillea millefolium (CVe = 0.356) (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Ten species with the highest cultural value coefficients.

Respondents used plants most frequently as food or drink (55 taxa) and for medicinal purposes (46 taxa) (Table 2). They used 22 taxa exclusively as food, 11 taxa exclusively as medicine, and 21 for both food and medicinal purposes. On average, 13 taxa were recorded per interview for food or beverage (Median = 12, SD = ±4.682) and seven for medicinal purposes (Median = 6, SD = ±4.144). In addition, plants were used as livestock feed (33 species), to make alcoholic beverages (15 species), for ceremonial purposes (11 species, Figure 3) and to build or make useful objects (10 species).

Table 2.

Use reports and the number of plants in different use categories.

Figure 3.

Baskets with food to be taken to church for blessing on Holy Saturday, including traditional Easter eggs colored with onion skins (photo: Hodak A.).

The average number of use reports per plant is 11.24 for the whole study area. The taxon Cornus mas has the largest number of recorded uses (UR = 63), followed by Prunus domestica L. (UR = 49), Juglans regia (UR = 46), Urtica dioica (UR = 41) and Achillea millefolium (UR = 41) (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

The first 15 highest ranked taxa according to use reports (UR).

Cornus mas is not only the most commonly used plant; together with Tilia platyphyllos, it also has the most different uses, namely five. However, for the latter plant, the total number of uses is only UR = 30. On average, the number of uses, i.e., use categories, is 1.72 per plant.

Prunus domestica has the highest UR in the food and drink category (UR = 31) and Achillea millefolium in the medicine category (UR = 37). In alcoholic beverages, Juglans regia L. (UR = 19) is used most for the production of sweet walnut liqueur. Taraxacum sect. Ruderalia is mostly used as livestock feed (UR = 21), and Corylus avellana L. is the most commonly used plant in the category of building and making useful items (UR = 11) (Table 3).

Table 3.

Comparative overview of taxa according to UR in six use categories.

Measured with the informant consensus factor (Fic), respondents showed the highest level of agreement in the food and beverage (Ficall = 0.89) and ceremonial purpose (Ficall = 0.87) use categories (Figure 5). Fic values are above 0.5 for all use categories, indicating a relatively high level of consensus.

Figure 5.

Total use reports and factor of informant consensus (Fic) for specified use categories.

Regarding use as food or beverage, interviewees have the highest agreement regarding Prunus domestica (FLs = 96.88) and Cornus mas (FLs = 90.91) (Table 4). In the medicinal use category, Achillea millefolium has FLs = 100, which means that all respondents who named this plant classified it as a plant for medicinal purposes. Other frequently mentioned taxa have a FLs for medicine of less than 50. In the category of taxa for alcoholic beverages, the highest FLs is for Juglans regia (63.33), followed by Prunus domestica (FLs = 56.25) and Cornus mas (FLs = 51.52). In the animal feed use category, agreement is highest for the taxa Taraxacum spp. (FLs = 65.62) and Urtica dioica (FLs = 45.16). A large proportion of respondents indicated that the taxon Corylus avellana is, or has been, used in construction or for making useful items for the home or farm. Of the ten taxa with the highest UR, only Cornus mas is used for ceremonial purposes (FLs = 42.42).

Table 4.

Fidelity Level (FLs) for the ten taxa with the highest UR.

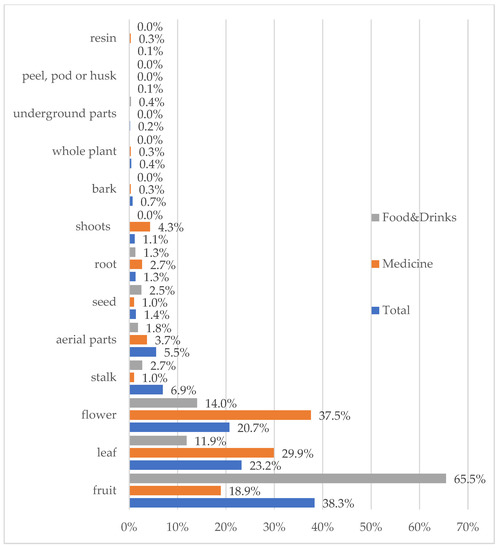

The most commonly used plant parts are fruits (38% of all plant parts mentioned), leaves (23%), and flowers (21%) (Figure 6). Fruits are most commonly used as food, while the flower and leaf parts are most commonly used for medicinal purposes.

Figure 6.

Relative frequency of mentioning plant parts.

A total of 284 uses of plants for medicinal purposes were recorded, most of which were for treating stomach aches (44), colds (25), and coughs (21). The greatest variety of plant species is used to treat diarrhea (6), open wounds (5) and coughs (5). The most frequently reported unique medicinal uses were the treatment of heart problems in humans (six use reports) and the treatment of erysipelas in pigs (four use reports). We found high fidelity levels regarding the use of certain plants for medicinal purposes with respect to treatment of stomach pains, colds, coughs, wounds, abdominal cramps and pain, diarrhea, earache, anemia and warts (Table 5).

Table 5.

Priority taxa for the treatment of certain health problems based on the fidelity level index.

Mushrooms or fungi were mentioned a total of 34 times by 21 of the 40 respondents (mean = 0.85). Therefore, on average, 1.6 taxa were mentioned per interview. Agaricus sp. (20 times) and Boletus sp. (6 times) were mentioned most frequently. Mushrooms are used as food, usually fried with eggs. A more recent method of preparation is in risottos or sauces (Boletus sp., Cantharellus cibarius Fr., and Morchella sp.). Three respondents mentioned eating the fruits of Prunus domestica infected with Taphrina pruni (Fuckel) Tul. fungus as children.

Treatments and Disease Prevention in Animal Health—Lika

The results show the most frequently mentioned plant species used to treat various diseases and ailments in animals. In both people and animals (cows, pigs, chicken...), diarrhea is treated with dried fruits of Rumex spp. or a decoction of Cydonia oblonga L., R. pulcher L., and oak bark (Quercus sp.), which is sometimes even combined with Hypericum perforatum L. A decoction of St. John’s wort (H. perforatum) or juice squeezed from raw green bean leaves (Phaseolus vulgaris L.) is also used to wash wounds and scratches in cattle and to stop bleeding. Hellebore (Helleborus dumetorum Waldst. & Kit. ex Willd.) has long been used for cattle and horses to treat inflammation of the larynx or ears. The affected area is pierced with a cleaned hellebore root, which leads to irritation and the formation of an abscess that draws out the inflammation. Danewort (Sambucus ebulus L.) has been used to treat swine ersypelas in pigs, reduce swelling from snake bites in cows, and when extracting fever from the body.

Silene vulgaris (Moench) Garcke is used in religious ceremonies, brought to church for blessing, later salted and given to cattle to eat.

The largest number of taxa (101) and the highest mean number of taxa listed per respondent (27.05) were recorded in the locality of Perušić. Seventy-three taxa were recorded in the locality of Lovinac (25.31 per respondent) and 59 in Gospić (average 22.09). The average number of taxa per subject is statistically significantly higher in the Perušić locality than in the Gospić locality (ANOVA F(2,47) = 3.5, p = 0.038, Scheffe post hoc test p = 0.008). The average number of records per respondent is significantly higher in the Perušić locality than in the Gospić locality (ANOVA F(2,47) = 3.5, p = 0.038, Scheffe post hoc test p = 0.008). One possible reason for this difference is the larger proportion of the population in the Perušić locality employed in activities related to agricultural and forestry resources. Most of the population of Gospić is not employed in the primary sector and lives in urban conditions.

3. Discussion

Considering the entire study area, 40 of the total 111 taxa recorded have absolute frequencies of 10 or more, and 10 have frequencies of 30 or more. The frequencies of taxa in individual areas range from zero to 15, and are highest in the Perušić locality (16 respondents). In the Gospić locality (11 respondents), there are four taxa with frequencies of 10 or more; in the Lovinac locality (13 respondents) there are eight; and in the Perušić locality there are 15. These data confirm the difference in ethnobotanical knowledge in the three studied areas could be due to the greater degree of urbanization around Gospić. The relative frequencies indicate a higher concentration around a lower number of known taxa around Gospić and Lovinac compared to Perušić. Namely, in the former two areas, three taxa are mentioned by all respondents (RFC = 1.00). In Perušić, there is no such instance for any taxon. The decrease in ethnobotanical knowledge of people moving to urban settings (like Gospić) can be expected and was even recorded in the Balkans from Kosovo [27].

The inhabitants of the Lika region use very few or almost no wild vegetables in their diet for the purpose of cooking (stews, soups, with meats). Their diet is based on crops that they can grow themselves in the garden, such as cabbage that can be lacto-fermented in the fall for the winter, potatoes, beans, garlic, onions, and corn for flour or polenta. This is in contrast with, e.g., the Zadar region of Dalmatia on the other side of the Velebit range, where a large number of wild vegetable taxa is used [15].

The five wild plant species with the highest frequency of mentions from the area of central Lika (this research) are also commonly used in the area of Knin [12]: Rosa canina 90% (Lika) vs. 65% (Knin), Sambucus nigra 82.5% (Lika) vs. 72.5% (Knin), Cornus mas 82.5% (Lika) vs. 65% (Knin), Taraxacum 80% (Lika) vs. 40% (Knin) and Prunus spinosa 82.5% (Lika) vs. 35% (Knin).

Comparing this research and the neighboring area of Knin [12], we noted 55 plant taxa used in both areas, but not always for the same purpose. Out of the high-frequency species in the area of central Lika, Rubus caesius (UR 24), Carum carvi (UR 21), and Pyrus communis (UR 8) were not recorded in Knin. Comparing the most frequently mentioned species with studies from other countries, we found some different uses, e.g., Juglans regia and Mentha spicata L. leaves with salt were used as traditional insect repellents in Bulgaria [28]. In addition, we found some similar or identical medicinal applications of the most commonly used species. For example, Achillea millefolium is used in tea to treat stomach pain in South Kosovo [29].

A large number of fruit species are still used to distil rakija spirits in the study area, including Prunus domestica, Pyrus spp., Cydonia oblonga, Juniperus communis and—nowadays quite rarely, due to longer collection time—Cornus mas. Plum brandy, so-called lička šljivovica (“Lika plum brandy”), is used most commonly.

The local cultivar of pears (Pyrus communis “Tepka”) is also commonly used in the area —it must be bletted to be tasty for consumption, and in the past, it was cut, strung on twine, dried and eaten on Christmas Eve. A dish called oša consists of a thick compote of dried pears or prunes/fresh plums with homemade bread. However, this tradition has been forgotten in the last 50 years. According to Hećimović-Seselja [30], fall pears are used to make pickles such as “turšija” (Turkish: Turs, Greek: Τουρσί-tours, Bulgarian: Tursia, Albanian: Turshiju). The traditional recipe has been preserved to this day and many families still use it.

The observed number of wild mushrooms used for food is relatively low for the habitat of Lika, which is very rich in fungi species due to the presence of mixed deciduous forests. Here only a few species of mushrooms are used for food, but harvesting and selling mushrooms (for purchase or privately along the highway) has been an important contribution to the household budget of the inhabitants of Lika for many years; they are very widespread, and about 15 kg can be harvested in one afternoon (oral statement of respondents). For comparison, in the Romanian Carpathians, 24 species are used by a similar sample of the local population of Ukrainians (on average 9.7 per respondent) [31]. A large number of mushroom taxa are also eaten in Poland, e.g., 76 in the Mazovia region— 9.5 per respondent [32]. On the other hand, similarly to Lika, few species of fungi are used on the coast of Croatia, e.g., 0.2 species of fungi were listed per interview on Krk and in Poljica [33]. Altogether, six species are used on Krk and four in Poljica. In this sense, Lika is similar to the above coastal populations. However, it differs in the low use of wild vegetables, similar to northern Slavic populations [17]. Although the more “herbophilic” attitude of the Slavic population (highlighted in previous studies) is not visible in this survey, the same statement applies to ethnobotanical research in South Kosovo [29]. An interesting feature of fungi use in the study area is the use of plum fruits deformed by the fungus Taphrina pruni (Fuckel) Tul. The food use of this fungus has never been recorded in ethnobiological literature. The situation is comparable to the use of corn smut Ustilago maydis (DC.) Cordacalled in the Mexican huitlacoche [34]—a gall formed on the stalks of maize, said to have been eaten fresh by local residents and with a slightly sour taste.

A large number of children’s snacks should be noted. Some of the respondents state that as children, apart from Taphrina, they used to nibble on young Fagus sylvatica leaves and young Rosa canina shoots. They also state that they sucked the flower of Primula vulgaris or juice from the stem of Rumex acetosa. In the municipality of Lovinac, there is also mention of sucking juice from the root of Scorzonera villosa.

As shepherding has been the basis for the local economy for centuries, it must be noted that some knowledge on plants used to cure and feed animal persists in the area. In Lika, Sambucus ebulus has been used to treat swine erisypelas in pigs or to reduce swelling from snake bites in cows as well as to extract fever from the body. Similar uses were recorded in an earlier study by Hećimović-Seselja from 1985 [30]. In Poland S. ebulus was used to treat tuberculosis [35], and Akbulut & Özkan have recorded its use in Turkey against external parasites [36].

The majority of food and medicinal plants used in the area are ubiquitous species of widely known and documented use. Helleborus dumetorum Waldst. & Kit. ex Willd is an exception. Although Helleborus species have been known to be used in human and animal medicinal practices, they are highly toxic. Therefore, their use has been decreasing. Their application in veterinary practices in the area is an archaic feature. Helleborus species are still used in other parts of south-eastern Europe, but relatively rarely, e.g., in Transylviania Helleborus purpurascens Waldst. & Kit. is known for its use in immunotherapy, treatment of wounds, and as an antiemetic drug in ethnoveterinary medicine [37]. In the neighboring Bosnia and Herzegovina, Helleborus odorus Waldst. & Kit. ex Willd is used for medicinal purposes for humans, in the form of a decoction and infusion for liver and skin disease [38].

Another use of Helleborus is the children’s game “titra”, which uses the plant’s stems and is still remembered by the local population. Several players can participate in the game. According to the rules, each player can have 5 to 10 “titre”—stems of Helleborus. The stems are arranged in a bundle. The first player holds them in the palm of his right hand, transfers them to the upper side of the same hand, catches them and counts how many pairs of stems he has caught. If the player counts an odd number, then he takes one “titra”, puts it aside, and throws the rest of the stems one more time, palm facing down. If the player has an odd number of stems the second time, he sets two stems aside. If the player catches an even number during their next turn, they lose, and the next person follows the same procedure until all her credits are used up. The player with the most “titre” is the winner [30].

The effect of the ex-Yugoslav war between 1991–1995 may have also had a strong effect on plant knowledge in the area. The region was highly depopulated both by heavy fighting with the Serbian army and by the exodus of local inhabitants to cities and other countries. Additionally, a large percentage of the Orthodox (Serbian, Vlah) population left the region.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Study Site

The field research study was conducted in a continental, mountainous part of Croatia, in three municipalities (Perušić, Gospić and Lovinac) of Lika-Senj County (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

The geographical position of the central Lika study site (source: based on digital maps of Lika-Senj County, Geoportal [https://www.rc.licko-senjska.hr/geoportal/ (accessed on: 3 November 2022)] and Informacijski sustav prostornog uređenja, Geoportal, [https://ispu.mgipu.hr/ (accessed on 3 November 2022)]).

The areas of the municipalities extend from NW to SE and have a range of ca. 60 km, with an elevation of mainly 550–600 m above sea level. The study area covers 1692 km2 with a total of 16,390 inhabitants, most of whom live in Gospić (12,745 or 78%). Perušić and Lovinac are typical rural areas with a very low population density of 6.89 and 2.95 inhabitants per km2, respectively. The municipality of Gospić has the status of a town and is the seat of Lika County. Gospić is the only settlement with more than 10,000 inhabitants in the county, but even this administrative area is sparsely populated, with only 13.18 inhabitants per km2. The percentage of inhabitants aged 65 years or above is over 35% in the locality of Perušić and Lovinac, and 21% in the locality of Gospić.

According to its current population density, Lika is a sub-ecumenical area. From the beginning of the 20th century, Lika lagged far behind in terms of agricultural and economic development, and there was not enough food for the population, so some of the inhabitants moved to other parts of Croatia or abroad [26]. These periods coincided with periods of war, namely World War II and the war for Croatian independence (Homeland War, 1991–1995). According to Bušljeta Tonković [39], the processes of deagrarianization, deruralization, urbanization, aging and population decline, which are defined as socio-geographical factors of landscape development, are present in the area of central Lika. They have led to a series of negative features, such as the extensified use of agricultural areas and the abandonment of their cultivation, which have caused the landscape to show signs of neglect.

The cessation of animal husbandry and the abandonment of pastures and meadows has led to progressive succession, causing pastures to disappear and be replaced by scrubland and eventually forest, which is the climax (final stage) of vegetation in Croatia.

In the area of central Lika, the proportion of fertile land is small due to the domination of karstic rocks, which, along with unfavorable climatic conditions (low average annual temperature, short growing season for certain crops), significantly affects the characteristics of agricultural production (the choice of crops for cultivation is narrowed).

According to the Köppen climate classification, the area of Lika is dominated by a moderately warm humid climate with hot summers (Cfb), and only the highest mountain areas of Velebit, Plješivica and Mala Kapela have a snow-forest climate (Df) [40]. Accordingly, beech and fir forests (Aremonio-Fagion) predominate in Lika, and in the highest areas the beech forest transitions into low forms of coniferous trees, where Pinus mugo Turra is dominant. Downy oak and sessile oak (Quercion pubescenti-petraeae) predominate in fields, forests and thickets, where white hornbeam (Carpinetum orientalis s.l.) is also present [41].

The landscape of Lika includes characteristic slopes bounded by the longest Croatian mountain Velebit—the highest peak of Lika (Vaganski vrh, 1757 m)—in the west-southwest, by Velika Kapela and Mala Kapela in the northwest, and by Plješivica (highest peak Ozeblin, 1657 m) in the east [41].

The Velebit mountain range separates the continental and coastal parts of the Lika-Senj County, and the Northern Velebit National Park, the Paklenica National Park and the Velebit National Park lie on its territory [42]. Plitvička jezera NP, the oldest and most visited Croatian national park, is located in the northeastern part of the county and is included in the UNESCO list of world natural heritage. Between the highlands, at an altitude of 500 m above sea level, lie karst fields under agricultural use, the most important being Gacko polje and Ličko polje. The Gacka and Lika sinkhole rivers, which belong to the Adriatic basin, flow through these fields, and there is an artificial reservoir lake Kruščica, on the Lika river.

4.2. Sampling and Interviews

Data were collected through a survey of the local population conducted during the period February–May 2020. The second author of this paper is originally from the investigated area and helped with the selection of the interviewees. In-depth semi-structured interviews and the free listing method were used. The principles of the American Anthropological Association Code of Ethics [43] and the International Society of Ethnobiology Code of Ethics [44] were followed in conducting the survey. Respondents were selected using the snowball method [45]. Only native inhabitants or those who had lived there most of their lives were interviewed. Recommendations from key respondents were also considered in the respondent selection process. Interviewees were approached mostly outdoors, and interviews were conducted during walks so that informants could see, recognize, and name individual plants. During the survey, information was collected on the vernacular names of the plants, their useful parts, types of use, and preparation/recipies for use. Forty interviews were undertaken–16 in Perušić area, 11 in Gospić and 13 in Lovinac area. The mean age of respondents was 73 years, and the median age was 76 years. The average age of respondents from Lovinac area (67 years) is slightly lower than in the other two areas, but the age difference is not statistically significant (it ranged from 55 to 88). Females constituted the majority of informants (87.5%). The interviewees were of Croatian ethnicity from Roman-Catholic religious background.

Seven non-exclusive modalities or categories were available for various uses: food or drink, medicine, alcoholic beverages, animal feed, construction and handicrafts, ceremonial uses, and other. For plant identification, standard floras for this area of Europe were used, such as: Nikolić’s guide to the identification of the flora of Croatia [46], Pignatti’s Flora of Italy [47], and the Flora Croatica Database [48]. The names of the plants are aligned with The Plant List [49]. The voucher specimens were collected, digitized and stored at the University of Zagreb Faculty of Agriculture, ZAGR Herbarium (http://herbarium.agr.hr/ (accessed on: 14 October 2022)). Fungi were placed in the Croatian National Fungarium (CNF) in Zagreb (http://mycolsoc.hr/hrvatski-nacionalni-fungarij/ (accessed on: 14 October 2022)).

4.3. Data Analysis

The main variables of the dataset were: the informant’s code number, the place of the survey, the order of mention of the plants, the local plant name, the types of use and the preparation method for each type of use, i.e., the use category. In addition, for each taxon recorded, the following information was provided: scientific plant name and plant parts used.

All taxa mentioned two or more times were included in the analyses performed. Taxa that were mentioned only once were included only if we considered the information to be particularly relevant and provided by the most trusted informants.

To determine the level of awareness of a single taxon among respondents, relative frequencies were calculated using the following formula:

where RFC is the relative frequency of citation, FC is the absolute frequency or number of mentions of a single taxon, and N is the total number of informants [50].

RFC = FC/N,

The importance of a single taxon with respect to the entire study area and each of its three subregions was first evaluated using Smith’s S salience measure (Sj) [51]. This indicator is used to find taxa that are most characteristic of the studied area, taking the frequency and order of mention into account. The following formula was used to calculate Sj:

where L is the length of the plant list per informant, Rj is the rank of taxon j in the list, and N is the total number of lists in the survey.

Sj = ((L − Rj + 1)/L)/N,

We assessed the practical importance of taxa to the community using the cultural value coefficient (CV) [52]. This indicator quantifies the usefulness of a taxon to the community based on the eight categories of use. The value of CV depends on the number of respondents who report using a taxon and the number of use categories. The following formula was used to calculate CV:

where Uce represents the number of uses of taxon e divided by the number of possible uses (in this case, 7). The symbol Ice represents the number of respondents who indicated that taxon e is used, relative to the total number of respondents, and IUce is the quotient of the sum of respondents for each of the 7 uses and the total number of respondents. For example, if taxon e was used for food by 35 respondents and for medicinal purposes by 4 respondents, IUce = (35 + 4)/40 [53].

CVe = Uce·Ice·∑IUce,

The respondents’ consensus regarding the use of plants for a specific purpose was quantified using the informant consensus factor (Fic) function. This indicator is based on the number of use reports (nur) and the number of taxa (ntaxa) per specific use category [54,55]:

Fic = (nur − ntaxa)/(nur −1).

The use report indicator (UR) per species is the number of mentions of use of a specific plant species in all use categories [55]. A higher value of this indicator suggests a higher level of agreement among respondents.

To determine the taxa that are most commonly used for a given purpose, we used the FLs function, which calculates the degree of fidelity per species. The FLs value for a given taxon and use category represents the percentage of informants using a plant for the same purpose compared to all uses of all plants:

FLs = (Ns ∗ 100)/FCs.

In the formula, Ns represents the number of informants using a given plant for a given purpose, and FCs represent the total number of uses for the taxon [56].

Calculations of descriptive statistics indicators for respondent characteristics, absolute and relative frequencies of plant species, the number of species per interview, and Jaccard similarity coefficients (JI) were performed using the program Microsoft Excel, Version 2013, Microsoft Corporation, Redmond, WA, USA. A comparison of results by location was performed using ANOVA in the program IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 21, IBM Corp., Armonk, NY, USA. Other calculations and analyzes were performed using packages “ethnobotanyR” [55] and “AnthroTools” [57] of the R, Version 4.0.3, R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria [58].

5. Conclusions

The list of plant taxa used is largely typical for central Europe. Like in other central European regions, few wild vegetables are used, and mainly fruits and medicinal herbs are collected from the wild. Similarly to coastal parts of Croatia, surprisingly few taxa of edible fungi are collected, in spite of the presence of large areas of woodland.

We can assume that the differences in ethnobotanical knowledge between the three studied areas are partly due to minor differences in climate and topography, while other causes lie in the higher degree of rurality and stronger ties to nature in the Perušić and Lovinac areas.

Based on the observed situation and results, we propose actions to preserve the remaining traditional plant knowledge, primarily in the form of activities and workshops to promote the use and preparation of local wild plant food products and herbal teas among the local population.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, I.V.-K.; methodology, I.V.-K. and J.J.; validation, I.V.-K., J.J., and Ł.Ł.; formal analysis, I.V.-K., A.H. and J.J.; investigation, I.V.-K. and A.H.; data curation, I.V.-K. and J.J.; assistant data curation M.M., writing—original draft preparation, I.V.-K., J.J. and Ł.Ł.; writing—review and editing, A.H. and M.M.; supervision, I.V.-K. and Ł.Ł. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to show our gratitude to the residents of the studied areas of Perušić, Gospić and Lovinac for sharing their time and knowledge with us. We are also immensely grateful to Nasim Łuczaj for help with proofreading in English. We thank the anonymous reviewers for their valuable comments.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Akbulut, S.; Bayramoglu, M.M. Reflections of Socio-economic and Demographic Structure of Urban and Rural on the Use of Medicinal and Aromatic Plants: The Sample of Trabzon Province. Stud. Ethno-Med. 2014, 8, 89–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quave, C.L.; Pieroni, A. A reservoir of ethnobotanical knowledge informs resilient food security and health strategies in the Balkans. Nat. Plants 2015, 1, 14021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kendir, G.; Guvenc, A. Ethnobotany and a General View of Ethnobotanical Studies in Turkey. Hacet. Univ. J. Fac. Pharm. 2010, 30, 49–80. [Google Scholar]

- Pieroni, A.; Price, L.L. Eating and Healing: Traditional Food as Medicine; Haworth Press: New York, NY, USA, 2006; pp. 1–383. [Google Scholar]

- Heinrich, M.; Kerrouche, S.; Bharij, K.S. Recent advances in research on wild food plants and their biological—Pharmacological activity. In Mediterranean Wild Edible Plants. Ethnobotany and Food Composition Tables; de Cortes Sánchez-Mata, M., Tardío, J., Eds.; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2016; pp. 253–269. [Google Scholar]

- Aggarwal, G.; Kaur, G.; Bhardwaj, G.; Mutreja, V.; Sohal, H.S.; Nayik, G.A.; Bhardwaj, A.; Sharma, A. Traditional Uses, Phytochemical Composition, Pharmacological Properties, and the Biodiscovery Potential of the Genus Cirsium. Chemistry 2022, 4, 1161–1192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdul Aziz, M.; Abbasi, A.M.; Ullah, Z.; Pieroni, A. Shared but threatened: The heritage of wild food plant gathering among different linguistic and religious groups in the Ishkoman and Yasin valleys, North Pakistan. Foods 2020, 9, 601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nikolić, T.; Antonić, O.; Alegro, A.L.; Dobrović, I.; Bogdanović, S.; Liber, Z.; Rešetnik, I. Plant species diversity of Adriatic islands: An introductory survey. Plant Biosyst. Int. J. Deal. All Asp. Plant Biol. 2008, 142, 435–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczaj, Ł.; Jug-Dujaković, M.; Dolina, K.; Jeričević, M.; Vitasović-Kosić, I. Insular pharmacopoeias: Ethnobotanical characteristics of medicinal plants used on the Adriatic islands. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 12, 623070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczaj, Ł.; Jug-Dujaković, M.; Dolina, K.; Jeričević, M.; Vitasović-Kosić, I. The ethnobotany and biogeography of wild vegetables in the Adriatic islands. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019, 15, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitasović Kosić, I.; Juračak, J.; Łuczaj, Ł. Using Ellenberg-Pignatti values to estimate habitat preferences of wild food and medicinal plants: An example from northeastern Istria (Croatia). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2017, 13, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Varga, F.; Šolić, I.; Dujaković, M.J.; Łuczaj, Ł.; Grdiša, M. The first contribution to the ethnobotany of inland Dalmatia: Medicinal and wild food plants of the Knin area, Croatia. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2019, 8, 3622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Milković, K. Prirodno Liječenje Biljem s Ličko-Senjskih Staništa; Private Edition: Gospić, Croatia, 2007. [Google Scholar]

- Łuczaj, Ł.; Pieroni, A.; Tardío, J.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M.; Sõukand, R.; Svanberg, I.; Kalle, R. Wild food plant use in 21st century Europe: The disappearance of old traditions and the search for new cuisines involving wild edibles. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2012, 81, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczaj, Ł.; Končić, M.Z.; Miličević, T.; Dolina, K.; Pandža, M. Wild vegetable mixes sold in the markets of Dalmatia (southern Croatia). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2013, 9, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łuczaj, Ł.; Fressel, N.; Perković, S. Wild food plants used in the villages of the Lake Vrana Nature Park (northern Dalmatia, Croatia). Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2013, 82, 275–281. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Łuczaj, Ł. Archival data on wild food plants used in Poland in 1948. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2008, 4, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Łuczaj, Ł.; Dolina, K. A hundred years of change in wild vegetable use in southern Herzegovina. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 166, 297–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dolina, K.; Luczaj, L. Wild food plants used on the Dubrovnik coast (south-eastern Croatia). Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2014, 83, 175–181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moszyński, K. O Sposobach Badania Kultury Materialnej Prasłowian; Zakład Narodowy im. Ossolińskich: Wrocław, Poland, 1962. [Google Scholar]

- Mattalia, M.; Stryamets, N.; Pieroni, A.; Sõukand, R. Knowledge transmission patterns at the border: Ethnobotany of Hutsuls living in the Carpathian Mountains of Bukovina (SW Ukraine and NE Romania). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2020, 16, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vitasović-Kosić, I.; Kaligarič, M.; Juračak, J. Divergence of Ethnobotanical Knowledge of Slovenians on the Edge of the Mediterranean as a Result of Historical, Geographical and Cultural Drivers. Plants 2021, 10, 2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akbulut, S. Differences in the traditional use of wild plants between rural and urban areas: The sample of Adana. Stud. Ethno-Med. 2015, 9, 141–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marković, M. O etnogenezi stanovništva Like. In Zbornik za Narodni Život i Običaje; Knjiga, 53; Cifrić, I., Ed.; Jugoslavenska Akademija Znanosti i Umjetnosti: Zagreb, Croatia, 1995; pp. 73–190. [Google Scholar]

- Marković, M. Narodni Život i Običaji Sezonskih Stočara na Velebitu, Zbornik za Narodni Život i Običaje; Knj. 48; JAZU: Zagreb, Croatia, 1980; pp. 12–13. [Google Scholar]

- Lopašić, R. Spomenici Hrvatske Krajine; Jugoslavenska Akademija Znanosti i Umjetnosti: Zagreb, Croatia, 1885; pp. 193, 244, 287, 299. [Google Scholar]

- Mullalija, B.; Mustafa, B.; Hajdari, A.; Quave, C.L.; Pieroni, A. Ethnobotany of rural and urban Albanians and Serbs in the Anadrini region, Kosovo. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2021, 68, 1825–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ivanova, T.; Bosseva, Y.; Chervenkov, M.; Dimitrova, D. Enough to Feed Ourselves—Food plants in Bulgarian rural home gardens. Plants 2021, 10, 2520. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mustafa, B.; Hajdari, A.; Pulaj, B.; Quave, C.L.; Pieroni, A. Medical and food ethnobotany among Albanians and Serbs living in the Shtërpcë/Štrpce area, South Kosovo. J. Herb. Med. 2020, 22, 100344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hećimović-Seselja, M. Tradicijski Život i Kultura Ličkog Sela Ivčević Kosa; Mladen Seselja & Muzej Like: Zagreb-Gospić, Croatia, 1985. [Google Scholar]

- Łuczaj, Ł.; Stawarczyk, K.; Kosiek, T.; Pietras, M.; Kujawska, A. Wild food plants and fungi used by Ukrainians in the western part of the Maramures region in Romania. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2015, 84, 339–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kotowski, M.A.; Pietras, M.; Łuczaj, Ł. Extreme levels of mycophilia documented in Mazovia, a region of Poland. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019, 15, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dolina, K.; Jug-Dujakovic, M.; Łuczaj, Ł.; Vitasović-Kosić, I. A century of changes in wild food plant use in coastal Croatia: The example of Krk and Poljica. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2016, 85, 3508. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Juárez-Montiel, M.; de León, S.R.; Chávez-Camarillo, G.; Hernández-Rodríguez, C.; Villa-Tanaca, L. Huitlacoche (corn smut), caused by the phytopathogenic fungus Ustilago maydis, as a functional food. Rev. Iberoam. De Micol. 2011, 28, 69–73. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujawska, M.; Łuczaj, Ł.; Sosnowska, J.; Klepacki, P. Rośliny w Wierzeniach i Zwyczajach Ludowych: Słownik Adama Fischera; Polskie Towarzystwo Ludoznawcze: Wrocław, Poland, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Akbulut, S.; Özkan, Z.C. An ethnoveterinary study on medicinal plants used for animal diseases in Rize (Turkey). Appl. Ecol. Environ. Res. 2022, 20, 4109–4119. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balázs, V.L.; Filep, R.; Ambrus, T.; Kocsis, M.; Farkas, Á.; Stranczinger, S.; Papp, N. Ethnobotanical, historical and histological evaluation of Helleborus, L. genetic resources used in veterinary and human ethnomedicine. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2020, 67, 781–797. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Redžić, S.S. The ecological aspect of ethnobotany and ethnopharmacology of population in Bosnia and Herzegovina. Coll. Antropol. 2007, 31, 869–890. [Google Scholar]

- Bušljeta Tonković, A. Održivi Razvoj Središnje Like; Institut Društvenih Znanosti Ivo Pilar-Područni Centar: Gospić, Croatia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Šegota, T.; Filipčić, A. Köppenova podjela klima i hrvatsko nazivlje. Geoadria 2003, 8, 17–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magaš, D. Geografija Hrvatske; Sveučilište u Zadru: Zadar, Croatia, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Novalja, G. Strategija Ukupnog Razvoja 2016—2020; Grad Novalja: Novalja, Croatia, 2015; pp. 7–8. [Google Scholar]

- American Anthropological Association. AAA Statement on Ethics. Available online: https://www.americananthro.org/LearnAndTeach/Content.aspx?ItemNumber=22869 (accessed on 17 June 2022).

- International Society of Ethnobiology. ISE Code of Ethics (with 2008 Additions). Available online: http://ethnobiology.net/codeof-ethics (accessed on 17 June 2022).

- Bernard, H.R. Research Methods in Anthropology: Qualitative and Quantitative Approaches; Rowman & Littlefield: Walnut Creek, CA, USA, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolić, T. Flora Croatica Vaskularna flora Republike Hrvatske 4; Alfa d.d.: Zagreb, Croatia, 2019. [Google Scholar]

- Pignatti, S.; Guarino, R.; La Rosa, M. Flora d’Italia; Edagricole: Bologna, Italy, 2017; Volume 2. [Google Scholar]

- Nikolić, T. Flora Croatica Database; Prirodoslovno-Matematički Fakultet, Sveučilište u Zagrebu: Zagreb, Croatia, 2022; Available online: http://hirc.botanic.hr/fcd (accessed on 5 April 2022).

- The Plant List. Version 1. Published on the Internet. 2010. Available online: http://www.theplantlist.org/ (accessed on 1 October 2022).

- Tardío, J.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M. Cultural Importance Indices: A Comparative Analysis Based on the Useful Wild Plants of Southern Cantabria (Northern Spain). Econ. Bot. 2008, 62, 24–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgatti, S. Cultural concensus theory. In The Ethnographic Toolkit; Schensul, J., Ed.; Sage Publications: Thousan Oaks, CA, USA, 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Reyes-Garcia, V.; Huanca, T.; Vadez, V.; Leonard, W.; Wilkie, D. Cultural, Practical, and Economic Value of Wild Plants: A Quantitative Study in the Bolivian Amazon. Econ. Bot. 2006, 60, 62–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrier, J.; Saciragic, L.; Trakić, S.; Chen, E.C.; Gendron, R.L.; Cuerrier, A.; Balick, M.J.; Redžić, S.; Alikadić, E.; Arnason, J.T. An ethnobotany of the Lukomir Highlanders of Bosnia & Herzegovina. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2015, 11, 81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Žuna Pfeiffer, T.; Krstin, L.J.; Špoljarić Maronić, D.; Hmura, M.; Eržić, I.; Bek, N.; Stević, F. An ethnobotanical survey of useful wild plants in the north-eastern part of Croatia (Pannonian region). Plant Biosyst. 2020, 154, 463–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Whitney, C. Ethnobotany R: Calculate Quantitative Ethnobotany Indices; R Package Version 0.1.8.; 2021. Available online: https://CRAN.R-project.org/package=ethnobotanyR (accessed on 30 October 2022).

- Friedman, J.; Yaniv, Z.; Dafni, A.; Palewitch, D. A preliminary classification of the healing potential of medicinal plants, based on a rational analysis of an ethnopharmacological field survey among Bedouins in the Negev Desert, Israel. J. Ethnopharmacol. 1986, 16, 275–287. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Purzycki, B.G.; Jamieson-Lane, A. AnthroTools: An R Package for Cross-Cultural Ethnographic Data Analysis. Cross-Cult. Res. 2017, 51, 51–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- R Core Team. R: A Language and Environment for Statistical Computing; R Foundation for Statistical Computing: Vienna, Austria, 2021; Available online: https://www.R-project.org/ (accessed on 30 October 2022).

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).