Abstract

Viscum is one of the most famous and appreciated medicinal plants in Europe and beyond. The symbiotic relationship with the host tree and various endogenous and ecological aspects are the main factors on which the viscum metabolites’ profiles depend. In addition, European traditional medicine mentions that only in two periods of the year (summer solstice and winter solstice) the therapeutic potential of the plant is at its maximum. Many studies have investigated the phytotherapeutic properties of viscum grown on different species of trees. However, studies on Romanian viscum are relatively few and refer mainly to the antioxidant and antiproliferative activity of mistletoe grown on Acer campestre, Fraxinus excelsior, Populus nigra, Malus domestica, or Robinia pseudoacacia. This study reports the first complete low-molecular-weight metabolite profile of Romanian wild-grown European viscum. A total of 140 metabolites were identified under mass spectra (MS) positive mode from 15 secondary metabolite categories: flavonoids, amino acids and peptides, terpenoids, phenolic acids, fatty acids, organic acids, nucleosides, alcohols and esters, amines, coumarins, alkaloids, lignans, steroids, aldehydes, and miscellaneous. In addition, the biological activity of each class of metabolite is discussed. The development of a simple and selective phyto-engineered AuNPs carrier assembly is reported and an evaluation of the nanocarrier system’s morpho-structure is performed, to capitalize on the beneficial properties of viscum and AuNPs.

1. Introduction

Since ancient times, viscum was the “crown jewel” of European traditional medicine. Viscum is considered the universal healing plant, to which have been attributed to many symbols and rituals throughout the world. Practically all over the world, there are many superstitions, ceremonials, and legends associated with the mistletoe that grows on a specific host tree [1,2,3,4,5]. For instance, in Europe, a viscum-grown oak tree is said to have mystical properties (banishing witches and evil spirits, battle protection, finding treasures, love, fecundity, and so on) [1,2,3,4,5].

For the Druids, viscum was a divine tree, which grows without roots. It was evergreen, which is why it represents a connection between heaven and earth; the source of life for the tree’s spirit.

In Japan, Ainu attributed properties similar to the viscum-grown willow tree [1,2,3,4,5]. There were rituals related to the manner and period of the viscum harvest all over Europe.

The Druids considered that summer solstice was the moment when the maximum potential of the plant was reached. However, in many northern European countries, viscum was harvested during the winter and was associated with love, peace, protection, and fertility.

Later, in Christian Europe, the tradition of viscum was perpetuated. Nowadays, between Christmas and New Year, the houses are decorated with viscum twigs, as a symbol of eternal life, protection, and fortune [1,2,3].

Viscum’s healing properties have been well known since ancient times. The famous scholars Hippocrates, Pliny the Elder, and then Paracelsus and Hildegard of Bingen used the plant for various diseases of the spine, liver, infertility, epilepsy, and ulcers [6].

Afterwards, viscum was considered a remedy for pain, parotitis, epilepsy, edema, cardiac diseases, and hepatitis [6]. At the beginning of the 20th century, in Europe, the hypertensive and antitumor activity of the plant was studied [6]. However, viscum’s therapeutic properties (antidiabetic, analgesic, anti-inflammatory, and hypotensive) were already known in Asian (Israel, China, India and Japan) and African traditional medicine [6,7].

Currently, viscum is used as a complementary treatment in cancer therapy in several European countries, where there are different types of commercial phytotherapeutic extracts: Iscador, Isorel, Eurixor, Plenesol, Vysorel, Lektinol, Helixor, Cefalektin, and Lektinol [4,5,6,7]. Some studies report also that its extract enhances an organism’s immune response [4]. However, the phytotherapeutic effects of medicinal plants and their use in the therapy of severe conditions, such as cancer or neurodegenerative diseases, is still a contradictory topic in Western medicine [8,9].

The highly complex chemical composition and biological activity of viscum could be the result of a mixture of biotic (mainly host tree) and abiotic characteristics (water quantity, soil, pH, temperature, sun exposure, harvest season, and growth stage of the plant) [10,11].

Various research reported a large number of phytochemicals, such as lectins (glycopeptides), viscotoxins, terpenoids, coumarins, flavonoids, peptides, carbohydrates, sterols, alkaloids, proteins, amines, polyphenols, amino acids, and lignans [6,7,8,9,10,11,12]. These compounds were studied extensively to establish a relationship between antitumor activity and their biological properties. The main molecules in viscum considered to pose antitumor properties are lectins and viscotoxins. However, recent studies have reported that other secondary metabolites, such as triterpenoids and phenolic derivatives, have anticancer properties [6,7]. It has also been found that the antitumor activity of particular metabolites isolated from viscum is much lower than that of the extract itself. It is due to the synergistic action by which metabolites act [6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13].

Latest studies have shown that viscum extract has positive effects on the quality of life of cancer patients by reducing the side effects of chemo and radiation therapy [14,15,16]. However, the results of the studies indicate that the antitumor activity of viscum seems to be influenced by several factors (the amount of plant used in the extract, the type of host tree, and the harvest period).

Studies have shown the existence of variation in the content of lectins and viscotoxins depending on the season. Thus, there is a maximum of these phytoconstituents in the viscum samples collected in June and December, thus confirming the practices of traditional medicine [17]. Although various recent research reported the cytotoxic, apoptotic, anti-inflammatory, and immunological effects of viscum, the antitumor mechanism is not fully elucidated and not fully understood [15,16].

Gold has influenced human civilization from the humanity dawn through its characteristics and availability, both materially (social hierarchy) and spiritually. From an esoteric and religious point of view, it was considered a symbol of perfection, immortality, rejuvenation, health, and wisdom. In human belief, gold played an essential role: from the symbolism of the sun in astrology to the highest degree of development of matter (mind, spirit, and soul) in alchemy, as well as the renewal and regeneration of humanity to perfection, enlightenment, and spiritual elevation. In Christianity, gold was associated with divine worship and love [18,19].

In medicine, gold has been used for medical purposes since ancient times. In traditional Chinese medicine, gold was used as a therapeutic agent for various ailments (joint, lungs, measles, skin ulcers, wounds, seizures, detoxification, palpitation, coughing, typhoid fever, and so forth) [20]. In Indian traditional medicine (Ayurveda and Siddha), gold is also used for infertility, asthma, diabetes, and cancer [21]. The Ayurvedic gold preparations are a mixture of gold nanoparticles and herbs used, in which the metal had a double role as a carrier and therapeutic agent [22,23].

Since antiquity there has been evidence of the use of gold in traditional European medicine, such as for skin infection treatment and as an antidote to mercury poisoning [24]. Archaeological discoveries show that in ancient Egypt it was used for dental work [25,26].

Later, in the Middle Ages, according to the documents of the time, “aurum potabile” or other gold-based preparations were used for many types of heart conditions, digestive ailments, baldness, fever, and so on [26,27].

Since the end of the 19th century, gold therapy has been adopted for the treatment of syphilis, tuberculosis, rheumatoid arthritis, and other types of arthritis. Scientific results have shown the ineffectiveness of gold derivatives in treating tuberculosis. It is noteworthy that chrysotherapy (or therapy with gold compounds) is accepted and implemented in modern medicine for rheumatoid arthritis treatment. Gold compounds have demonstrated anti-inflammatory properties and are used as a common medication for chronic and progressive inflammation of bones and joints [26,27,28,29].

Currently, colloidal gold is included in the category of food supplements and is used for antibacterial, antioxidant, and anti-age properties [27,30]. Recent research reported that different gold species possess anticancer, antiproliferative, antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, antibacterial, anti-rheumatic, and antimalarial properties [27,29,31].

The latest research on the biomedical applications of gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) has shown potential in medical imaging, drug delivery systems, or therapeutic agents for cancer, HIV, neurodegenerative diseases (Alzheimer’s, Parkinson’s), nutrition diseases (diabetes, obesity), ophthalmology, and tissue engineering [28].

AuNPs display versatility, strong surface plasmon absorption, high stability, biocompatibility, and low toxicity in biological environments. Moreover, their high surface-to-volume ratio and predetermined size allow the functionalization of a wide variety of biologically active compounds. Hence, they are especially useful in the design of innovative materials, robust and selective for vectorization, imaging, diagnostics, and cancer therapy [28,31,32,33]. Hereafter, the design of a phyto-engineered-AuNPs carrier assembly will act as a selective vehicle with multi-targeted effects that exert a significant anti-proliferative effect [31,32,33,34].

There is relatively little research on Romanian viscum aimed mainly at determining certain constituents such as polyphenols, total proteins, amino acids, peptides, lectins, and viscotoxins from various parts of the plant (young leaves and branches). Moreover, most of these studies used viscum collected from Acer campestre, Mallus domestica, Fraxinus excelsior, Populus nigra, and R. pseudoacacia [5,35,36,37,38,39,40].

To our best knowledge, this study investigates for the first time the complete low-molecular-weight metabolite profile of the Romanian Viscum album hosted on Quercus robur L. (collected on summer solstice). Furthermore, our previous studies were focused on identifying the amino acids and thionines in viscum (collected near the winter solstice) from the same oak species [5].

The results of this study confirm, for the first time, the existence of a difference between the profile of amino acids and small peptides in the viscum samples grown on the same Romanian oak species and collected in the two periods considered critical by traditional European medicine.

Another novelty of this study is that, for the first time, an active, selective, and specific target-engineered carrier assembly with AuNPs features, which collectively capitalizes the therapeutic properties of Romanian viscum (whole plant), was developed and analyzed.

2. Results and Discussion

Plants, and medicinal plants in particular, contain a remarkable complex mixture of natural compounds with unique chemical structures and a significant number of stereogenic centers. A herb’s biological activity is due to the synergistic interaction of all its compounds within an organism. Therefore, the pharmacological action of a plant extract is attributed to a whole multi-component mixture of constituent natural compounds [41,42,43].

On the other hand, an important aspect that must be considered for herb chemical screening, is that its metabolites profile varies depending on various endogenous or ecological factors [38,44,45].

Numerous research studies have focused on the highly complex phytochemical content of viscum. However, the correlation between their metabolic profiles and bioactivity has not yet been established. One of the main reasons is the variation in the composition of the phytoconstituents depending on the host tree [39,46,47].

A qualitative untargeted metabolomics profiling strategy based on a mass spectrometry approach is a powerful tool for fast and cost-effective chemical screening of secondary metabolites from natural compounds.

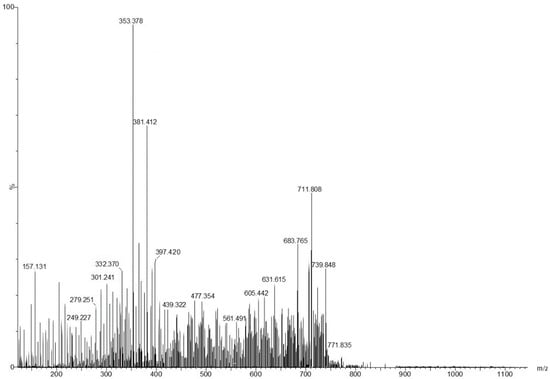

The chemical screening profile of low-molecular-weight metabolites from viscum was tentatively identified through electrospray ionization–quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (ESI-QTOF-MS) analysis. The mass spectra of the components identified were accomplished by connecting with those of NIST/EPA/NIH, Mass Spectral Library 2.0 database and reviewing the literature [46,47,48,49,50,51]. The mass spectrum and the components identified by ESI-QTOF-MS analysis are presented in Figure 1 and Table 1.

Figure 1.

The mass spectrum of Romanian Viscum album hosted on Quercus robur L. (collected on summer solstice).

Table 1.

Components identified through electrospray ionization–quadrupole time-of-flight mass spectrometry (ESI-QTOF-MS) analysis.

2.1. Screening and Classification of the Differential Metabolites

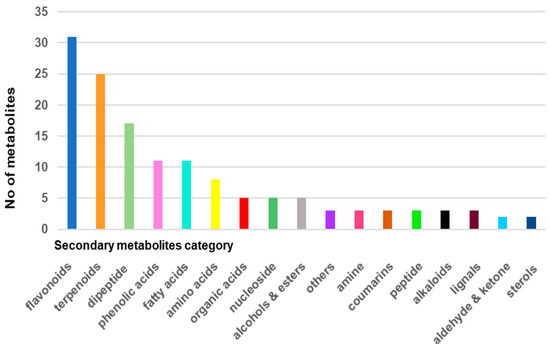

A total of 140 compounds were found and identified by mass spectroscopy analysis, including primary metabolites (amino acids, peptides, organic acids, nucleosides, etc.) and secondary metabolites (terpenoids, flavonoids, sterols, coumarins, alkaloids, phenolic acids, sterols, fatty acids, and miscellaneous), confirming the results reported in other studies on this plant [10,11,40,41,42,43,44,45,46,47,48,49,50,51,52,53,54,55,56,57,58,59]. These phytochemicals were assigned to different chemical categories: flavonoids (22.14%), amino acids and peptides (20%), terpenoids (17.85%), phenolic acids (7.85%), fatty acids (7.85%), organic acids (4.28%), nucleosides (3.57%), alcohols and esters (3.57%), coumarins (2.14%), alkaloids (2.14%), amines (2.14%), lignals (2.14%), sterols (1.42%), aldehydes and ketones (1.42%), and other. Flavonoids, amino acids and peptides, and terpenoids represent about 60% of all metabolites identified in Viscum album. The distribution of the identified metabolites in various chemical classes is listed in Table 2.

Table 2.

Classification of metabolites from the Viscum album sample on different chemical categories.

Figure 2 presents the metabolite classification chart and was obtained on the basis of the data analysis reported in Table 2.

Figure 2.

Metabolite classification bar chart of Romanian Viscum album hosted on Quercus robur L. (collected on summer solstice).

Amino acids and peptides: a total of 28 compounds were identified in the plant extract. A large part of these compounds (over 80%) is essential amino acids (phenylalanine, leucine, tryptophan, valine, methionine, histidine, and arginine). The non-essential amino acids (tyrosine, glutamic acid, cysteine, proline, glycine, alanine, and asparagine) are present only in a smaller proportion, about 20% of them [60,61,62,63,64]. The majority of the amino acids identified in the viscum sample (arginine, phenylalanine, tryptophan, histidine, glutamic acid, methionine, glycine, and proline) exhibit cytotoxicity, antiproliferative, and immunomodulant activity [61,62,63,64,65].

Several new small peptides (17 dipeptides, a cyclic peptide, and one tripeptide) have been identified, indicating that the profile of small peptides varies in the chemical composition of the viscum grown on the same oak species during the summer solstice and winter solstice [5]. This difference in the composition of small peptides in the viscum samples (on oak in the same geographical region) confirms the variation in plant therapeutic properties (especially antitumor and immunomodulatory) depending on the two periods considered essential in traditional European medicine [7,17].

Terpenoids and sesquiterpenes are among the main categories of metabolites found in viscum samples. Extensive studies report their antimicrobial, antioxidant, anticonvulsive, analgesic, neuroprotective, anti-inflammatory, anti-allergic, and antitumoral activities [51,60,65,66,67,68].

Coumarins are another class of phytoconstituents with high biological activity: antiviral, antimicrobial, antioxidant, analgesic, anticancer, anti-inflammatory, and anti-neurodegenerative [60,69]. Studies have shown coumarins’ therapeutic applications in several types of cancer: leukemia, breast, renal, prostate, and malignant melanoma [65,70].

Flavonoids are the largest class of metabolites (over 30 different compounds) in the viscum sample. These biomolecules have numerous therapeutic effects: antioxidant, antitumoral, cardiovascular system protection (atherosclerosis, antiplatelet), antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and neurodegenerative diseases (Alzheimer) [60,65,71,72,73].

Phenolic acids are reported to act as an antioxidant, anti-inflammatory, antitumoral, neuroprotective, antimicrobial, and antidiabetic agents [60,65,74,75].

Sterol and steroids have been demonstrated to have anti-inflammatory, antitumoral, antidiabetic, antioxidant, anti-atherosclerotic, neuroprotective, immunomodulatory, osteoporosis protection, and cardiovascular protective (anti-atherosclerosis, anti-hemolytic) activities [60,65,76].

Fatty acids represent another important class of secondary metabolites, representing approximately 8% of the total metabolites identified in the viscum sample. Various studies highlight their importance for human health, such as anti-inflammatory, antioxidant, neuroprotective (stroke, Alzheimer’s disease), and cardiovascular protective activity (anti-arrhythmic, dyslipidemia, hypertension, and anti-thrombotic) [60,65,77].

Carbohydrates and polysaccharides are biomolecules involved in the different beneficial roles for human health: anti-inflammatory, antiviral (anti-HIV), antioxidant (anti-ageing), digestive protection, cardio-protective, anti-arthritic, antibacterial, immunomodulatory, anti-diabetic, and anti-tumoral [60,65,78,79].

Glycosides are plant metabolites that act as antitumoral agents, especially for gastric cancer and chronic granulocytic leukemia [65,79].

Miscellaneous compounds, for instance, nonalide (lactone), identified in the viscum sample extract have antifungal activity, antimalarial, and cytotoxic activities [51].

2.2. Engineered Viscum–AuNPs Carrier Assembly

Development of targeted assembly rides on a robust and complex carrier assembly design that collectively combines the therapeutic properties of both components (viscum and an inorganic component) and the physicochemical characteristics of AuNPs (surface plasmon resonance, high surface area, conductivity, and low toxicity) [80,81,82].

Active targeting of an engineered carrier assembly relies upon a tailored surface to ensure high selectivity, vectorization, and specificity, and thus exert a significant therapeutic effect [80,81,82,83,84,85].

Development of targeted assembly rides on the construction of a robust, complex carried assembly that combines collectively the structural features of AuNPs (nontoxic, high biocompatibility and solubility, non-immunogenicity, and distinctive optical properties) with remarkable antitumor effects of both components (viscum and inorganic component) [28,34,80].

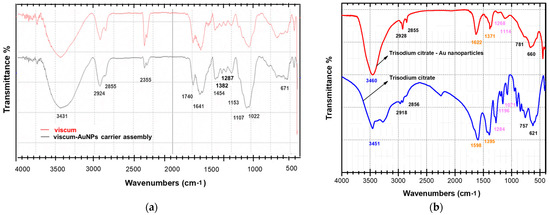

2.3. FT-IR Spectroscopy

The preparation of an engineered viscum–AuNPs carrier assembly was investigated by FT-IR spectroscopy to identify the functional groups specific to functional groups specific its two components, viscum and AuNPs. The individual FT-IR spectrum of the viscum and carrier assembly is shown in Figure 3a,b. The FT-IR absorption bands identified in the viscum sample are presented in Table 3.

Figure 3.

(a) FT-IR spectrum of the viscum sample and viscum–AuNPs carrier assembly; (b) FT-IR spectrum of AuNPs coated with trisodium citrate and the trisodium citrate spectrum.

Table 3.

The characteristic group frequencies attributed to different metabolites identified in Viscum album.

The FTIR peak of AuNPs coated with trisodium citrate (surfactant) (Figure 3b) presents the vibrational bands characteristic of a surfactant: at 3460 cm−1 (associated with a H–OH stretching vibration) and 2918 cm−1; at 2856 cm−1 (attributed with CH- asymmetric and symmetric stretching vibrations); at 1598 cm−1 (associated with a COO- stretching vibration); at 1395 cm−1; and at 757 cm−1 (assigned to C–H bending).

The formation of an engineered viscum–AuNPs carrier assembly was successfully achieved and was confirmed through FT-IR spectroscopy. The spectra of nanoparticle carrier assembly (Figure 3a) show the characteristic absorption bands of the viscum sample as well as the AuNPs coated with a surfactant (trisodium citrate) (Figure 3a,b). In addition, the peaks at 1622, 1371, 1258, 1114, and 660 cm−1 were found in the synthesized AuNP solution (Figure 3a) and are shifted to higher wavenumbers (1641, 1382, 1267, 1153 and 671 cm−1), indicating binding of nanoparticles to the functional groups O–H, C=O, C–N, C–S, and C–O belonging to the various phytoconstituents (Figure 3a,b and Table 3) [79,80,81,82,83,84,85,86,87,88,89,90,91]. In particular, the hydroxyl group is considered to be involved in the binding of AuNPs [85,86,87,88,89,90,91,92,93,94,95,96,97,98].

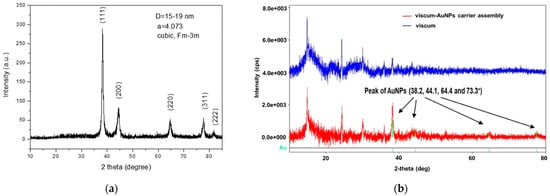

2.4. X-ray Diffraction Spectroscopy

Figure 4a,b present the XRD patterns of the AuNPs, viscum sample, and the engineered viscum–gold nanoparticles carrier assembly.

Figure 4.

(a) Powder XRD patterns of the AuNPs; (b) XRD patterns of the viscum sample and engineered viscum–AuNPs carrier assembly.

Figure 4a shows the specific XRD spectrum of AuNPs. The mean diameter (D) of the gold crystallites, calculated by using the Debye–Scherrer formula, was less than 20 nm. The AuNPs were well crystalized, with well-defined peaks.

The diffraction pattern of the viscum (Figure 4b) is in the range of 12–45°, with large bands and weak peaks characteristic of amorphous phases that can be attributed to plant fibers and minerals in the form of hydroxide.

The pattern of the engineered viscum–AuNPs carrier assembly has a shape similar to that of the viscum. In this spectrum, besides the wide bands and the weak peaks of the plant, one can observe, but much attenuated, the peaks of the AuNPs at 38.2, 44.1, 64.4, and 77.3°.

2.5. Scanning Electron Microscopy (SEM)

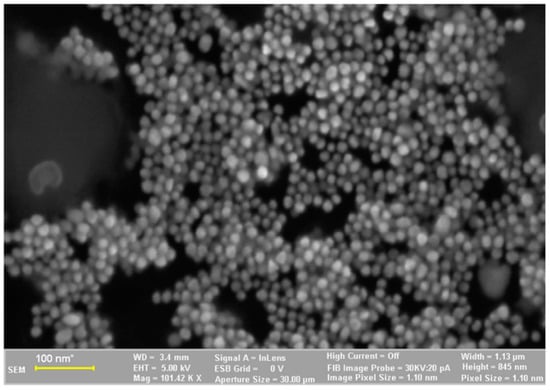

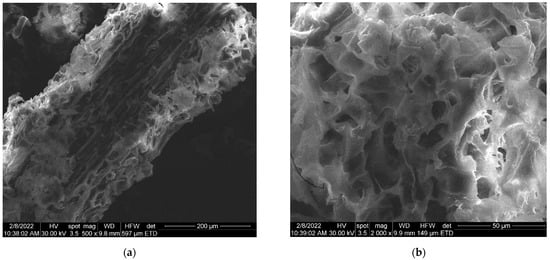

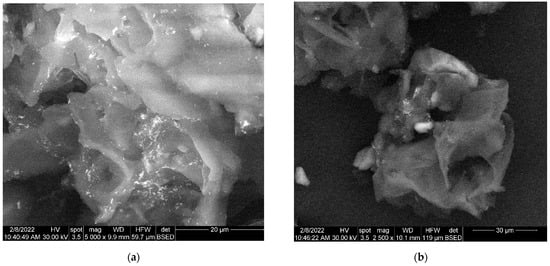

The SEM images of the synthesized AuNP solution, viscum sample, and engineered herb–AuNPs carrier assembly are presented in Figure 5, Figure 6, Figure 7, Figure 8 and Figure 9. SEM micrographs of the AuNPs (Figure 5a) indicate a surface structure with agglomerated regions of regular, spherical particles, with dimensions between 8 and 18 nm [99]. The morphology of the viscum sample (Figure 6a,b) displays a fibrous structure surface, with irregular, porous areas with dimensions less than 1 mm. The presence of pores suggests an easy fixation of AuNPs on the surface of the plant sample.

Figure 5.

Two-dimensional image of the AuNPs obtained by the SEM technique.

Figure 6.

(a) Two-dimensional image of the viscum sample obtained by the SEM technique (magnitude 200 µm). (b) Two-dimensional image of the viscum sample obtained by the SEM technique (magnitude 50 µm).

Figure 7.

(a) Two-dimensional image of the engineered viscum–AuNPs carrier assembly obtained by the SEM technique (magnitude 20 µm). (b) Two-dimensional image of the engineered viscum–AuNPs carrier assembly obtained by the SEM technique (magnitude 30 µm).

Figure 8.

Viscum sample: SEM—live map.

Figure 9.

Engineered viscum–AuNPs carrier assembly: SEM—live map.

The morphology of engineered viscum–AuNPs carrier assembly indicates the presence of AuNPs and agglomerations of AuNPs, fixed on the surface of viscum particles (Figure 7a) as well as loaded into the pores of viscum particles (Figure 7b).

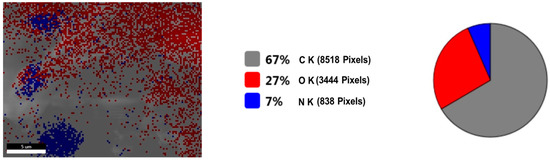

Figure 8 shows the live map of viscum and the distribution of the identified elements. Figure 9 shows the live map for the engineered viscum–AuNPs carrier assembly and the distribution of the identified elements. The comparative analysis of Figure 8 shows the live map for viscum and engineered viscum–AuNPs carrier assembly (Figure 9) and highlights the presence of differences regarding the proportion of identification elements in the two samples, due to the formation of the viscum–metal carrier assembly. SEM analysis and live map confirms the obtaining of the engineered viscum–AuNPs carrier assembly [74].

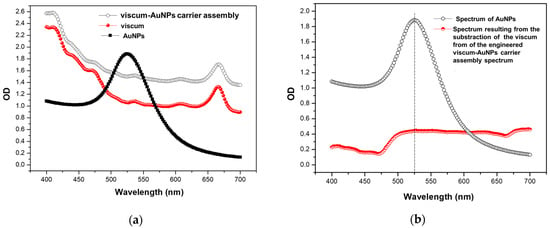

2.6. UV–VIS Spectroscopy

The optical properties (surface plasmon resonance) of AuNPs and the achievement of an engineered viscum–AuNPs carrier assembly were monitored through UV–Vis spectroscopy.

In Figure 10a, it can be seen that AuNPs show a peak absorption at 526 nm, but this absorption band is not visible in the case of the engineered viscum–AuNPs carrier assembly. The viscum absorption spectra and the final material (engineered viscum–AuNPs carrier assembly) do not show significant differences. Moreover, the specific absorption peak of the AuNPs is not visible in the spectrum of viscum–AuNPs. However, there is a clear difference in the absorbance intensity between the first two spectra, starting at about 475 nm. This was better emphasized by subtracting the viscum spectrum from the spectrum of the engineered viscum–AuNPs carrier assembly (Figure 10b). After subtraction, the surface plasmon band (at 526 nm) in the spectrum of AuNPs is now discreetly observed also in the subtraction curve, even if the profiles of the curves match approximately up to 526 nm only. This demonstrates that viscum successfully incorporated the AuNPs and that the engineered viscum–AuNPs carrier assembly was obtained.

Figure 10.

(a) UV–Vis spectra of the AuNPs, viscum, and engineered viscum–AuNPs carrier assembly respectively. (b) UV–Vis spectrum resulting from subtracting the UV–VIS spectra of the AuNPs from the UV–Vis spectrum of the engineered viscum–AuNPs carrier assembly.

3. Materials and Methods

All used reagents were analytical grade. Methanol and chloroform were purchased from VWR (Wien, Austria) and used without further purification.

3.1. Carrier Assembly Components Preparation

AuNPs Synthesis

The citrate synthesis of gold nanoparticles was achieved by the following procedure: in conical flasks (2000 mL), 0.5 g AuCl4H was weighted and a constant volume (1450 mL) of ultrapure water was added under magnetic stirring (800 rpm). Then, 50 mL of sodium citrate solution (1.6%) was added rapidly. The mixture was kept at room temperature (22 °C) for 40 min and 800 rpm.

3.2. Plant Sample Preparation

The five individual viscum (Viscum album L) samples (whole plant) were collected from three trees (Quercus robur L.) in June 2021 from the area of Timis county, Romania (geographic coordinates 45°47′5″ N 21°16′0″ E), and were taxonomically authenticated at West University of Timisoara, Romania. The plant samples were rapidly frozen in liquid nitrogen (190 °C), ground and sieved to obtain a particle size lower than 0.5 mm, and kept at −40 °C to avoid enzymatic conversion or metabolite degradation.

3.3. Plant Preparation for Chemical Screening

For each analysis, 1.5 g of dried viscum sample was subject to sonication extraction in 25 mL of solvent (methanol/chloroform = 1:1) for 30 min at 38 °C with a frequency of 60 kHz. The solution was concentrated using a rotavapor and the residue was dissolved in MeOH. The extract was centrifuged, and the supernatant was filtered through a 0.2 µm syringe filter and stored at –18 °C until analysis until MS analysis. All samples were prepared in triplicate.

3.4. Mass Spectrometry

The experiments were conducted using EIS-QTOF-MS from Bruker Daltonics, Bremen, Germany. All mass spectra were acquired in the positive ion mode within a mass range of 100–3000 m/z, with a scan speed of 2.1 scans/s. The source block temperature was kept at 80 °C. The reference provided a spectrum in positive ion mode with fair ionic coverage of the m/z range scanned in full-scan MS. The resulting spectrum was a sum of scans over the total ion current (TIC) acquired at 25–85 eV collision energy to provide the full set of diagnostic fragment ions.

The metabolites were identified via comparison of their mass spectra with those of the standard library NIST/NBS-3 (National Institute of Standards and Technology/National Bureau of Standards) spectral database and the identified phytoconstituents are presented in Table 1.

3.5. Phyto-Engineered AuNPs Carrier Assembly Preparation

For each analysis, 2.5 g of sample was prepared from dried viscum (whole plant, ground and sieved to obtain a particle size lower than 0.5 mm) and a AuNPs solution was added (viscum/AuNPs nanoparticles = 1:4) at room temperature (22 °C) and under magnetic stirring (400 rpm) for 24 h. The obtained mixture was filtered (Φ185 mm filter paper) and then dried in oven at 40 °C for 4 h.

3.6. Characterisation of the Engineered Viscum–AuNPs Carrier Assembly

3.6.1. UV–Vis Analysis

The measurements were conducted using a spectrophotometer UV–VIS Perkin-Elmer Lambda 35 packing pre-aligned halogen and deuterium lamps. The two sources of radiation cover the range of wavelengths of 190–1100 nm and a variable bandwidth range of 0.5 to 4 nm.

3.6.2. Fourier Transform Infrared (FTIR) Spectroscopy

FTIR spectra were obtained by using the KBr pellet method ranging from 4000 cm−1 to 400 cm−1, with a Perkin-Elmer Spectrum 100 FT-IR (Perkin–Elmer, Waltham, MA, USA).

The X-ray powder diffraction (XRD) pattern was performed using a Rigaku Ultima IV diffractometer equipped with a D/teX ultra-detector and operating at 40 kV and 40 mA, with monochromatic CuKα radiation (λ = 1.5406Å), in the 2θ range 10–80°, with a scan speed of 5°/min and a step size of 0.01°. The XRD patterns were compared with those from the ICDD Powder Diffraction Database, (ICDD file 04-015-9120). The average crystallite size and the phase content was calculated using the whole pattern profile fitting method (WPPF).

Scanning electron microscopy (SEM) micrographs were obtained with an SEM-EDS system (QUANTA INSPECT F50) equipped with a field-emission gun (FEG), 1.2 nm resolution, and energy dispersive X-ray spectrometer (EDS) with an MnK resolution of 133 eV.

4. Conclusions

In this study, the low molecular mass metabolites profiling of Viscum album (growing wild in Romania and hosted on Quercus robur L.) was accomplished. The biological activities were discussed for each metabolite category. Compared to our previous studies, 19 new small peptides were identified, which indicates that the profile of small peptides varies in the chemical composition of the viscum grown on the same oak species during the summer solstice and winter solstice.

Furthermore, a new and specific target-engineered viscum–AuNPs carrier assembly, with unique optical properties and great potential to increase the effectiveness of antitumor action and reduce unwanted side effects, was developed. The complete morpho-structural characterization of the viscum–AuNPs carrier assembly was performed. Further research is necessary to investigate the biological activity and biocompatibility of viscum extracts and the newly engineered viscum–AuNPs carrier assembly.

Author Contributions

Conception and design of study: A.-E.S. and I.G.; methodology: A.-E.S. and C.N.M.; acquisition of data: C.M. and C.N.M.; analysis and interpretation of data: C.N.M., C.M. and D.D.H.; writing—original draft preparation: I.S.; writing—review and editing: A.-E.S. and C.N.M.; investigation: I.S., C.M. and D.D.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Acknowledgments

National Center for Micro and Nanomaterials (the center is part of the Department of Science and Engineering of Oxide and Nanomaterials Materials of the Faculty of Applied Chemistry and Materials Science of the Polytechnic University of Bucharest).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Barlow, B. Mistletoe in Folk Legend and Medicine. 2008. Available online: https://www.anbg.gov.au/mistletoe/folk-legend.html (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Frazer, J.G. The Golden Bough: A Study in Magic and Religion; Palgrave Macmillan: London, UK, 1990. [Google Scholar]

- Gill, L.S.; Hawksworth, F.G. The Mistletoes: A Literature Review; U.S. Dept. Agr. Tech. Bul. 1242. U.S.; Government Printing Office: Washington, DC, USA, 1961. Available online: https://handle.nal.usda.gov/10113/CAT87201185 (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Ogunmefun, O.T.; Olatunji, B.P.; Adarabioyo, M.I. Ethnomedicinal Survey on the Uses of Mistletoe in South-Western Nigeria. Eur. J. Med. Plants 2015, 8, 224–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segneanu, A.; Velciov, S.M.; Olariu, S.; Cziple, F.; Damian, D.; Grozescu, I. Bioactive molecules profile from natural compounds. In Amino Acid-New Insights and Roles in Plant and Animal; Asao, T., Asaduzzaman, M., Eds.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Szurpnicka, A.; Kowalczuk, A.; Szterk, A. Biological activity of mistletoe: In vitro and in vivo studies and mechanisms of action. Arch. Pharm. Res. 2020, 43, 593–629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kleszken, E.; Timar, A.V.; Memete, A.R.; Miere (Groza), F.; Vicas, S.I. On overview of bioactive compounds, biological and pharmacological effects of mistletoe (Viscum album L.). Pharmacophore 2022, 13, 10–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freuding, M.; Keinki, C.; Micke, O.; Buentzel, J.; Huebner, J. Mistletoe in oncological treatment: A systematic review. J. Cancer Res. Clin. Oncol. 2019, 145, 695–707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mazalovska, M.; Calvin Kouokam, J. Plant-derived lectins as potential cancer therapeutics and diagnostic tools. BioMed Res. Int. 2020, 2020, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pietrzak, W.; Nowak, R. Impact of harvest conditions and host tree species on chemical composition and antioxidant activity of extracts from Viscum album L. Molecules 2021, 26, 3741. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jäger, T.; Holandino, C.; Melo, M.N.D.O.; Peñaloza, E.M.C.; Oliveira, A.P.; Garrett, R.; Glauser, G.; Grazi, M.; Ramm, H.; Urech, K.; et al. Metabolomics by UHPLC-Q-TOF Reveals Host Tree-Dependent Phytochemical Variation in Viscum album L. Plants 2021, 10, 1726. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Majeed, M.; Rehman, R.U. Phytochemistry, Pharmacology, and Toxicity of an Epiphytic Medicinal Shrub Viscum album L. (White Berry Mistletoe). In Medicinal and Aromatic Plants; Aftab, T., Hakeem, K.R., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2021; pp. 287–301. [Google Scholar]

- Yuan, H.; Ma, Q.; Ye, L.; Piao, G. The traditional medicine and modern medicine from natural products. Molecules 2016, 21, 559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loef, M.; Walach, H. Quality of life in cancer patients treated with mistletoe: A systematic review and meta-analysis. BMC Complement Med. Ther. 2020, 20, 227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oei, S.L.; Thronicke, A.; Schad, F. Mistletoe and immunomodulation: Insights and implications for anticancer therapies. Evid.-Based Complementary Altern. Med. 2019, 2019, 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marvibaigi, M.; Supriyanto, E.; Amini, N.; Abdul Majid, F.A.; Jaganathan, S.K. Preclinical and clinical effects of mistletoe against breast cancer. Biomed Res. Int. 2014, 2014, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Urech, K.; Schaller, G.; Jäggy, C. Viscotoxins, mistletoe lectins and their isoforms in mistletoe (Viscum album L.) extracts Iscador. Arzneimittelforschung 2011, 56, 428–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vang Petersen, P. Warrior art, religion and symbolism. In The Spoils of Victory. The North in the Shadow of the Roman Empire; Jørgensen, L., Storgaard, B., Thomsen, L.G., Eds.; National Museet: Copenhagen, Denmark, 2003; pp. 286–293. [Google Scholar]

- Available online: https://finds.org.uk/staffshoardsymposium/papers/charlottebehr (accessed on 2 June 2022).

- Huaizhi, Z.; Yuantao, N. China’s ancient gold drugs. Gold Bull. 2001, 34, 24–29. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patil-Bhole, T.; Wele, A.; Gudi, R.; Thakur, K.; Nadkarni, S.; Panmand, R.; Kale, B. Nanostructured gold in ancient Ayurvedic calcined drug ‘swarnabhasma’. J. Ayurveda Integr. Med. 2021, 12, 640–648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, R.; Prajapati, P.K. Nanotechnology in medicine: Leads from Ayurveda. J. Pharma Bioallied Sci. Jan.-Mar. 2016, 8, 80–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Parimalam, S.S.; Badilescu, S.; Bhat, R.; Packirisamy, M. A narrative review of scientific validation of gold- and silver-based Indian medicines and their future scope. Longhua Chin. Med. 2020, 3, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Metwaly, A.M.; Ghoneim, M.M.; Eissa, I.H.; Elsehemy, I.A.; Mostafa, A.E.; Hegazy, M.M.; Afifi, W.M.; Dou, D. Traditional ancient Egyptian medicine: A review. Saudi J. Biol. Sci. 2021, 28, 5823–5832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Forshaw, R.J. The practice of dentistry in ancient Egypt. Br. Dent. J. 2009, 206, 481–486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Console, R. Pharmaceutical use of gold from antiquity to the seventeenth century. Geol. Soc. Lond. Spec. Publ. 2013, 375, 171–191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pricker, S.P. Medical uses of gold compounds: Past, present and future. Gold Bull. 1996, 29, 53–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balfourier, A.; Kolosnjaj-Tabi, J.; Luciani, N.; Carn, F.; Gazeau, F. Gold-based therapy: From past to present. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 2020, 117, 22639–22648. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, H.H.; Su, C.H.; Wu, Y.J.; Lin, C.A.J.; Lee, C.H.; Shen, J.L.; Yeh, H.I. Application of gold in biomedicine: Past, present and future. Int. J. Gerontol. 2012, 6, 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medici, S.; Peana, M.F.; Zoroddu, M.A. Noble metals in pharmaceuticals: Applications and limitations. In Biomedical Applications of Metals; Rai, M., Ingle, A., Medici, S., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018; pp. 3–48. [Google Scholar]

- Ott, I. On the medicinal chemistry of gold complexes as anticancer drugs. Coord. Chem. Rev. 2009, 253, 1670–1681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goddard, Z.R.; Marín, M.J.; Russell, D.A.; Searcey, M. Active targeting of gold nanoparticles as cancer therapeutics. Chem. Soc. Rev. 2020, 49, 8774–8789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yafout, M.; Ousaid, A.; Khayati, Y.; El Otmani, I.S. Gold nanoparticles as a drug delivery system for standard chemotherapeutics: A new lead for targeted pharmacological cancer treatments. Sci. Afr. 2021, 11, e00685. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Wang, D.; Zhang, C.; Liu, H.; Hao, M.; Kan, S.; Liu, D.; Liu, W. The Applications of gold nanoparticles in the diagnosis and treatment of gastrointestinal cancer. Front. Oncol. 2022, 11, 819329. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vlad, D.C.; Popescu, R.; Dumitrascu, V.; Cimporescu, A.; Vlad, C.S.; Vágvölgyi, C.; Krisch, J.; Dehelean, C.; Horhat, F.G. Phytocomponents identification in mistletoe (Viscum album) young leaves and branches, by GC-MS and antiproliferative effect on HEPG2 And MCF7 cell lines. Farmacia 2016, 64, 82–87. [Google Scholar]

- Paun, G.; Rotinberg, P.; Mihai, C.; Neagu, E.; Radu, G.L. Cytostatic activity of Viscum album L. extract processed by microfiltration and ultrafiltration. Rom. Biotechnol. Lett. 2011, 16, 6000–6007. [Google Scholar]

- Vicas, S.I.; Socaciu, C. The biological activity of European mistletoe (Viscum album) extracts and their pharmaceutical impact. Bull. USAMV-CN 2007, 63, 217–222. [Google Scholar]

- Sevastre, B.; Olah, N.K.; Hanganu, D.; Sárpataki, O.; Taulescu, M.; Mănălăchioae, R.; Marcus, I.; Cătoi, C. Viscum album L. alcoholic extract enhance the effect of doxorubicin in ehrlich carcinoma tumor cells. Rom. Biotechnol. Lett. 2012, 17, 6976–6981. [Google Scholar]

- Stan, R.L.; Hangan, A.C.; Dican, L.; Sevastre, B.; Hanganu, D.; Catoi, C.; Sarpataki, O.; Ionescu, C.M. Comparative study concerning mistletoe viscotoxins antitumor activity. Acta Biol. Hung. 2013, 64, 279–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vicaş, S.I.; Rugina, D.; Leopold, L.; Pintea, A.; Socaciu, C. HPLC Fingerprint of bioactive compounds and antioxidant activities of Viscum album from different host trees. Not. Bot Hort Agrobot Cluj 2011, 39, 48–57. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yarnell, E. Synergy in Herbal Medicines: Part. J. Restor. Med. 2015, 1, 460–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Q.; Luan, X.; Zheng, M.; Tian, X.H.; Zhao, J.; Zhang, W.D.; Ma, B.L. Synergistic mechanisms of constituents in herbal extracts during intestinal absorption: Focus on natural occurring nanoparticles. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, R.A.; El-Anssary, A.A. Plants secondary metabolites: The key drivers of the pharmacological actions of medicinal plants. In Herbal Medicine; Philip, F., Builders, Eds.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, G.; Wang, S.; Huang, X.; Hong, J.; Du, L.; Zhang, L.; Ye, L. Environmental factors affecting growth and development of Banlangen (Radix Isatidis) in China. Afr. J. Plant. Sci. 2015, 9, 421–426. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, Z.; Chen, J.; Wang, T.; Gao, C.; Li, Z.; Guo, L.; Xu, J.; Cheng, Y. Linking plant secondary metabolites and plant microbiomes: A Review. Front. Plant. Sci. 2021, 12, 621276. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Y.; Zhao, Y.L.; Yang, Y.P.; Li, X.L. Chemical constituents of Viscum album var. meridianum. Biochem. Syst. Ecol. 2011, 39, 849–852. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.N.; Saha, C.; Galun, D.; Dalip, K.U.; Bayry, J.; Kaveri, S.V. European Viscum album: A potent phytotherapeutic agent with multifarious phytochemicals, pharmacological properties and clinical evidence. RSC Adv. R. Soc. Chem. 2016, 6, 23837–23857. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Urech, K.; Baumgartner, S. Chemical Constituents of Viscum Album L. Implications for the Pharmaceutical Preparation of Mistletoe in Mistletoe: From Mythology to Evidence-Based Medicine; Zanker, K.S., Kaveri, S.V., Eds.; Transl Res Biomed; Karger: Basel, Switzerland, 2015; Volume 4, pp. 11–23. [Google Scholar]

- Song, C.; Wei, X.-Y.; Qiu, Z.-D.; Gong, L.; Chen, Z.-Y.; Ma, Y.; Shen, Y.; Zhao, Y.-J.; Wang, W.-H.; Lai, C.-J.-S.; et al. Exploring the resources of the genus Viscum for potential therapeutic applications. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2021, 277, 114233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patel, B.P.; Singh, P.K. Viscum articulatum Burm. F.: A review on its phytochemistry, pharmacology and traditional uses. J. Pharm Pharm. 2018, 70, 159–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Q.; Chen, D.; Zhang, Q.; Qin, D.; Jiang, X.; Li, H.; Fang, l.; Cao, J.; Wu, H. Volatile components and nutritional qualities of Viscum articulatum Burm.f. parasitic on ancient tea trees. Food Sci. Nutr. 2019, 7, 3017–3029. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peñaloza, E.; Holandino, C.; Scherr, C.; de Araujo, P.I.P.; Borges, R.M.; Urech, K.; Baumgartner, S.; Garrett, R. Comprehensive metabolome analysis of fermented aqueous extracts of Viscum album L. by Liquid chromatography-high resolution tandem mass spectrometry. Molecules 2020, 25, 4006. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Stefanucci, A.; Zengin, G.; Llorent-Martinez, E.J.; Dimmito, M.P.; Della Valle, A.; Pieretti, S.; Gunes, A.K.; Sinan, K.I.; Mollica, A. Viscum album L. homogenizer-assisted and ultrasound-assisted extracts as potential sources of bioactive compounds. J. Food Biochem. 2020, 44, e13377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Holandino, C.; Melo, M.N.; Oliveira, A.P.; da Costa Batista, J.V.; Capella, M.A.M.; Garrett, R.; Grazi, M.; Ramm, H.; Torre, C.D.; Schaller, G.; et al. Phytochemical analysis and in vitro anti-proliferative activity of Viscum album ethanolic extracts. BMC Complement. Med. 2020, 20, 215. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chandra, K. Bio Active Compounds Isolated from Mistletoe (Scurulla Oortiana (Korth) Danser Parasiting Tea Plant Camellia sinenis L.). Master’s Thesis, University of Adelaide, Adelaide, Australia, 1996. [Google Scholar]

- Fukunaga, T.; Kajikawa, I.; Nashiya, K.; Watanabe, Y.; Suzuki, N.; Takeya, K.; Itokawa, H. Studies on the constituents of the European mistletoe, Viscum album L.II. Chem. Pharm. Bull. 1988, 36, 1185–1189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef][Green Version]

- Maher, S.; Fayyaz, S.; Naheed, N.; Dar, Z. The Isolation and screening of the bioactive compound of Viscum album against Meloidogyne incognita. Pak. J. Nematol. 2021, 39, 46–51. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oluwaseun, A.A.; Ganiyu, O. Antioxidant properties of methanolic extracts of mistletoes (Viscum album) from cocoa and cashew trees in Nigeria. Afr. J. Biotechnol. 2008, 7, 3138–3142. [Google Scholar]

- Park, B.J.; Matsuta, T.; Samejima, H.; Park, C.H. In Chemical constituents of mistletoe (Viscum album L. var. coloratum Ohwi) Sung, J.; Lee, B.D.; Onjo, M. IOSR J. Pharm. Biol. Sci. 2017, 12, 19–23. [Google Scholar]

- Das, K.; Gezici, S. Secondary plant metabolites, their separation and identification, and role in human disease prevention. Ann. Phytomedicine Int. J. 2018, 7, 13–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, S.-H.; Roszik, J.; Grimm, E.A.; Ekmekcioglu, S. Impact of L-arginine metabolism on immune response and anticancer immunotherapy. Front. Oncol. 2018, 8, 67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiangjong, W.; Chutipongtanate, S.; Hongeng, S. Anticancer peptide: Physicochemical property, functional aspect and trend in clinical application (Review). Int. J. Oncol. 2020, 57, 678–696. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lieu, E.L.; Nguyen, T.; Rhyne, S.; Kim, J. Amino acids in cancer. Exp. Mol. Med. 2020, 52, 15–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Albaugh, V.L.; Pinzon-Guzman, C.; Barbul, A. Arginine metabolism and cancer. Surg. Oncol. March 2017, 115, 273–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dhama, K.; Karthik, K.; Khandia, R.; Munjal, A.; Tiwari, R.; Rana, R.; Khurana, S.K.; Ullah, S.; Khan, R.U.; Alagawany, M.; et al. Medicinal and therapeutic potential of herbs and plant metabolites/Extracts countering viral pathogens-Current knowledge and future prospects. Curr. Drug Metab. 2018, 19, 236–263. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cox-Georgian, D.; Ramadoss, N.; Dona, C.; Basu, C. Therapeutic and medicinal uses of terpenes. In Medicinal Plants; Joshee, N., Dhekney, S., Parajuli, P., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2019; pp. 333–359. [Google Scholar]

- Fongang Fotsing, Y.S.; Bankeu Kezetas, J.J. Terpenoids as important bioactive constituents of essential oils, In Essential oils—Bioactive Compounds, New Perspectives and Application; Santana de Oliveira, M., Almeida da Costa, W., Gomes Silva, S., Eds.; Intechopen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2020; ISBN 978–1-83962–698–2. [Google Scholar]

- Jahangeer, M.; Fatima, R.; Ashiq, M.; Basharat, A.; Qamar, S.A.; Bilal, M.; Iqbal, H.M. Therapeutic and biomedical potentialities of terpenoids–A Review. J. Pure Appl. Microbiol. 2021, 15, 471–483. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- João Matos, M.; Santana, L.; Uriarte, E.; Abreu, O.A.; Molina, E.; Guardado Yordi, E. Coumarins—An important class of phytochemicals in phytochemicals-Isolation. In Characterisation and Role in Human Health; Venket Rao, A., Rao, L.G., Eds.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Küpeli Akkol, E.; Genç, Y.; Karpuz, B.; Sobarzo-Sánchez, E.; Capasso, R. Coumarins and coumarin-related compounds in pharmacotherapy of cancer. Cancers 2020, 12, 1959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kozłowska, A.; Szostak-Węgierek, D. Flavonoids–food sources, health benefits, and mechanisms involved. In Bioactive Molecules in Food; Reference Series in Phytochemistry; Mérillon, J.M., Ramawat, K., Eds.; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2018. [Google Scholar]

- Kozłowska, A.; Szostak-Wegierek, D. Flavonoids-food sources and health benefits. Rocz. Panstw. Zakl. Hig. 2014, 65, 79–85. [Google Scholar]

- Panche, A.N.; Diwan, A.D.; Chandra, S.R. Flavonoids: An overview. J. Nutr. Sci. 2016, 5, e47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumar, N.; Goel, N. Phenolic acids: Natural versatile molecules with promising therapeutic applications. Biotechnol Rep. 2019, 24, e00370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minatel, I.O.; Vanz Borges, C.; Ferreira, M.I.; Gomez, H.A.G.; Chen, C.Y.O.; Pace Pereira Lima, G. Phenolic compounds: Functional properties, impact of processing and bioavailability. In Phenolic Compounds-Biological Activity; Soto-Hernandez, M., Palma-Tenango, M., del Rosario Garcia-Mateos, M., Eds.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Salehi, B.; Quispe, C.; Sharifi-Rad, J.; Cruz-Martins, N.; Nigam, M.; Mishra, A.P.; Konovalov, D.A.; Orobinskaya, V.; Abu-Reidah, I.M.; Zam, W.; et al. Phytosterols: From preclinical evidence to potential clinical applications. Front. Pharmacol. 2021, 11, 599959. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nagy, K.; Tiuca, I.D. Importance of fatty acids in physiopathology of human body. In Fatty Acids; Catala, A., Ed.; IntechOpen: Rijeka, Croatia, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Kilcoyne, M.; Joshi, L. Carbohydrates in therapeutics. Cardiovasc. Hematol. Agents Med. Chem. 2007, 5, 186–197. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, D.; Rajput, A.; Bhatia, A.; Kumar, A.; Kaur, H.; Sharma, P.; Kaur, P.; Singh, S.; Attri, S.; Buttar, H.; et al. Plant-based polysaccharides and their health Functions. Funct. Foods Health Dis. 2021, 11, 179–200. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, X.; Zhang, Y.; Ding, T.; Liu, J.; Zhao, H. Multifunctional gold nanoparticles: A novel nanomaterial for various medical applications and biological activities. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Yeh, Y.C.; Creran, B.; Rotello, V.M. Gold nanoparticles: Preparation, properties, and applications in bionanotechnology. Nanoscale 2012, 4, 1871–1880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Siddique, S.; Chow, J.C.L. Gold nanoparticles for drug delivery and cancer therapy. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 3824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vega-Vásquez, P.; Mosier, N.S.; Irudayaraj, J. Nanoscale drug delivery systems: From Medicine to Agriculture. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2020, 8, 79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pala, R.; Anju, V.T.; Dyavaiah, M.; Busi, S.; Nauli, S.M. Nanoparticle-mediated drug delivery for the treatment of cardiovascular diseases. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 3741–3769. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boomi, P.; Ganesan, R.; Prabu Poorani, G.; Jegatheeswaran, S.; Balakumar, C.; Gurumallesh Prabu, H.; Anand, K.; Marimuthu Prabhu, N.; Jeyakanthan, J.; Saravanan, M. Phyto-engineered gold nanoparticles (AuNPs) with potential antibacterial, antioxidant, and wound healing activities under in vitro and in vivo conditions. Int. J. Nanomed. 2020, 15, 7553–7568. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heneczkowski, M.; Kopacz, M.; Nowak, D.; Kuźniar, A. Infrared spectrum analysis of some flavonoids. Acta Pol. Pharm. Nov.-Dec. 2001, 58, 415–420. [Google Scholar]

- Segneanu, A.E.; Marin, C.N.; Ghirlea, I.O.; Feier, C.V.I.; Muntean, C.; Grozescu, I. Artemisia annua Growing Wild in Romania-A metabolite profile approach to target a drug delivery system based on magnetite nanoparticles. Plants 2021, 10, 2245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.C.; Deng, J.; Lin, X.L.; Li, Y.M.; Sheng, H.X.; Xia, B.H.; Lin, L.M. Use of ATR-FTIR spectroscopy and chemometrics for the variation of active components in different harvesting periods of Lonicera japonica. Int. J. Anal. Chem. 2022, 2022, 8850914. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Mabasa, X.E.; Mathomu, L.M.; Madala, N.E.; Musie, E.M.; Sigidi, M.T. Molecular spectroscopic (FTIR and UV-Vis) and hyphenated chromatographic (UHPLC-qTOF-MS) analysis and in vitro bioactivities of the Momordica balsamina leaf extract. Biochem. Res. Int. 2021, 2021, 2854217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Scarsini, M.; Thurotte, A.; Veidl, B.; Amiard, F.; Niepceron, F.; Badawi, M.; Lagarde, F.; Schoefs, B.; Marchand, J. Metabolite quantification by Fourier Transform Infrared Spectroscopy in diatoms: Proof of concept on Phaeodactylum tricornutum. Front. Plant. Sci. 2021, 12, 756421. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Topală, C.M.; Tătarua, L.D.; Ducu, C. ATR-FTIR spectra fingerprinting of medicinal herbs extracts prepared using microwave extraction. Arab. J. Med. Aromat. Plants AJMAP 2017, 3, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Seuvre, A.M.; Mathlouthi, M. FT-IR. spectra of oligo- and poly-nucleotides. Carbohydr. Res. 1987, 169, 83–103. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Umashankar, T.; Govindappa, M.; Ramachandra, Y.L.; Rai, P.; Channabasava, S. Isolation and characterization of coumarin isolated from endophyte, Alternaria species-1 of Crotalaria pallida and its apoptotic action on HeLa cancer cell line. Metabolomics 2015, 5, 158. [Google Scholar]

- Salem, M.; Marzouk, M.; El-Kazak, A. Synthesis and characterization of some new coumarins with in vitro antitumor and antioxidant activity and high protective effects against DNA damage. Molecules 2016, 21, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baranska, M.; Schulz, H. Chapter 4 Determination of alkaloids through Infrared and Raman Spectroscopy. Alkaloids Chem. Biol. 2009, 67, 217–255. [Google Scholar]

- Pang, M.; Jiang, S.; Cao, L.; Pan, L. Novel synthesis of steryl esters from phytosterols and amino acid. J. Agric. Food Chem. 2011, 59, 10732–10736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thottoli, A.K.; Unni, A.K.A. Effect of trisodium citrate concentration on the particle growth of ZnS nanoparticles. J. Nanostructure Chem. 2013, 3, 56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, C. Antimicrobial activity and toxicity of gold nanoparticles: Research progress, challenges and prospects. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2018, 67, 537–543. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hitaishi, V.P.; Mazurenko, I.; Vengasseril Murali, A.; de Poulpiquet, A.; Coustillier, G.; Delaporte, P.; Lojou, E. Nanosecond laser–fabricated monolayer of gold nanoparticles on ITO for bioelectrocatalysis. Front. Chem. 2020, 8, 431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).