Abstract

Wild edible plants are an essential component of people’s diets in the Mediterranean basin. In Italy, ethnobotanical surveys have received increasing attention in the past two centuries, with some of these studies focusing on wild edible plants. In this regard, the literature in Italy lacks the coverage of some major issues focusing on plants used as herbs and spices. I searched national journals for articles on the use of wild food plants in Italy, published from 1963 to 2020. Aims of the present review were to document plant lore regarding wild herbs and spices in Italy, identify the wild plants most frequently used as spices, analyze the distribution of wild herbs and spices used at a national scale, and finally, to describe the most common phytochemical compounds present in wild plant species. Based on the 34 studies reviewed, I documented 78 wild taxa as being used in Italy as herbs or spices. The studies I included in this systematic review demonstrate that wild species used as herbs and spices enrich Italian folk cuisine and can represent an important resource for profitable, integrated local small-scale activities.

1. Introduction

In recent decades, detailed ethnobotanical studies have revealed the widespread use of wild plants in the Mediterranean basin [1,2,3,4]. Ethnobotany is a multidisciplinary investigation of interrelations between people and plants [5], and plays a key role in ascertaining the various plant species used in traditional cuisine. Indeed, ethnobotany of food plants is a fairly well-developed research field in several geographical areas and social communities [6,7,8]. Moreover, ethnobotanical studies concerning food plants offer novel ways to analyze and preserve traditional knowledge and agrobiodiversity in the Mediterranean area [3].

Herbs and spices produced from aromatic plants are largely used to enhance food taste and palatability. Sometimes used as synonyms, the distinction between the two terms (herbs and spices) could be summarized as follows: herbs are types of plants whose leaves are used in cooking to give flavor to particular dishes, while a spice is defined as any of the various aromatic products obtained from plants in the form of powder or seeds or other plant parts and used to add taste to food (e.g., [9,10,11,12]). According to Van der Veen and Morales [13] neither definition fully conveys the array of plants nor the range of purposes for which such plants are used. A further lexical complication is that, in the ethnobotanical literature, there are many terms to indicate the use of plants in cooking, e.g., aromatic, aromatizer, condiment, flavoring, and spice. In the present review, I refer to the wild species (the whole plant or parts of it) used for flavoring various dishes in the Italian folk tradition. In this context, I use the term “wild” to refer to non-cultivated or naturally occurring plants gathered in the field, although sometimes for convenience of use, some species are grown or deliberately tolerated in home gardens [14,15]. In some cases, food plants are also eaten for their health-giving properties and many species are commonly used as herbal medicines in folk phytotherapy for the treatment of ailments [16,17].

In Italy, ethnobotanical surveys have received increasing attention in recent decades, seeking to investigate the traditional uses of plants and their products (e.g., [18,19,20]). Some of these studies focus on wild edible plants (e.g., [21,22]), while others infer the use of wild plants as food through more general studies of ethnobotany (e.g., [23,24]). In this regard, the literature in Italy lacks the coverage of some major issues focusing on plants used as spices.

In this context, the aim of the present work is to review and highlight the use of wild plants as traditional herbs and spices in folk cuisine in Italy.

The specific aims of this study were: (a) to document plant lore regarding wild herbs and spices in Italy; (b) to identify the wild plants most frequently used as spices; (c) to analyze the distribution of wild herbs and spices used at a national scale; (d) to describe the most common phytochemical compounds present in wild plant species.

2. Results

General Data

Based on the 34 studies providing adequate and relevant data, I documented 78 wild taxa as being used in Italy as herbs or spices (Table 1). The plant species belong to 19 families and 49 genera. Lamiaceae (38.8%) is the most frequently cited family, followed by Amaryllidaceae (12.5%), Apiaceae (11.3%), Asteraceae (7.5%) and Rosaceae (6.3%). The most species-rich genus is Allium (9 species), followed by Mentha (8), Thymus (6) and Salvia (5). Leaves (63.0%) were the most frequently used plant parts, followed by fruits (10.9%), and flowers (8.7%). The remaining parts (including bulbs, seeds and roots) accounted for 17.4% overall.

Table 1.

Wild herbs and spices traditionally used in Italy (Abr—Abruzzo; Bas—Basilicata; Cal—Calabria; Cam—Campania; Emr—Emilia Romagna; Fvg—Friuli Venezia Giulia; Lig—Liguria; Lom—Lombardy; Mol—Molise; Pie—Piedmont; Pug—Puglia; Sar—Sardinia; Sic—Sicily; Tus—Tuscany).

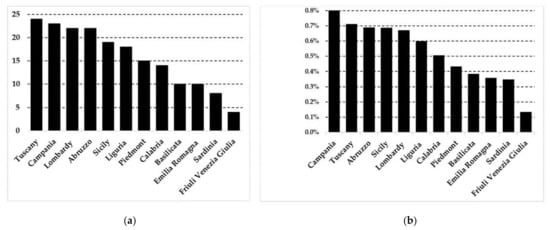

As shown in Figure 1a, from the analyses carried out at a regional scale, I found that Tuscany has the largest number of species used in a single region (24), followed by Campania (23), Abruzzo and Lombardy (22 each). The Ethnobotanicity Index values are significantly lower than those of other Italian regions (range 5.4–11%) or Iberian Peninsula (range 8.8–27.9%) that are calculated on medicinal, cosmetic, veterinary, and food species [17,52,53]. Although it is not possible to make a comparison with the same use category, results suggested that the knowledge of wild plants used as flavoring is still consolidated in the above-mentioned regions that are also among the most species-rich in Italy [54]. (Figure 1b). Papers containing reports of wild plants specifically used for flavoring are reported in the Supplementary Materials.

Figure 1.

Number of species used per Italian regions (a) and EI for each region (b).

3. Botany and Phytochemistry

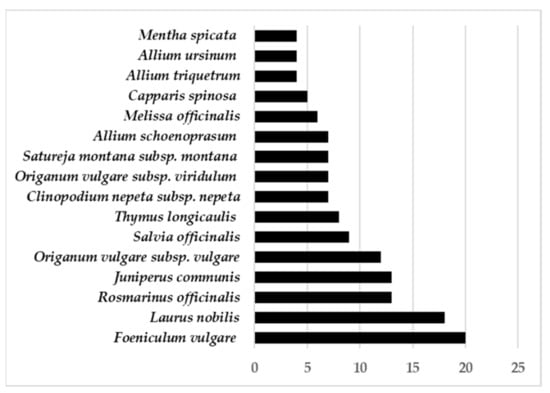

In Figure 2, I present a summary of the sixteen most commonly cited taxa Italy. For each species, I discuss its life form, chorology and phytochemical profiles.

Figure 2.

Most cited species in all Italian regions.

Fennel (Foeniculum vulgare Mill.) is a hardy, perennial herb native to Mediterranean coasts and widely naturalized in many parts of the world. Fennel seed is a rich source of volatile oil, with its main compounds being fenchone and trans-anethole. Other components of the essential oil are limonene, camphene, estragole and α-pinene [55,56]. The main constituents of the essential oils extracted from its leaves are trans-anethole, estragole, fenchone, and α-phellandrene; minor constituents are limonene, neophytadiene and phytol [57,58].

Bay laurel (Laurus nobilis L.) is an evergreen tree or large shrub native to the Mediterranean region. The aromatic leaves are rich in essential oils whose main components are: 1,8-Cineole, sabinene, α and β-pinene, α-terpinylacetate and linalool [59,60].

Rosemary (Rosmarinus officinalis L.) is an evergreen sclerophyllous shrub native to the Mediterranean basin. The main components of the essential oil are 1,8-Cineole, α and β-pinene, camphor, camphene and β-pinene [61]. Rosmarinic acid is an ester of caffeic acid and 3,4-dihydroxyphenyllactic acid, with a number of interesting biological activities (e.g., antiviral, antibacterial, anti-inflammatory and antioxidant) and is widely occurring in the Lamiaceae family.

The common juniper (Juniperus communis L.) is a multistemmed shrub or small tree, whose seed cones are usually called berries. This is the most widespread conifer in the world, native to temperate Eurasia, North America and northern Mexico, occupying an extraordinary range of habitats [62]. Juniper berry oil largely consists of monoterpene hydrocarbons such as 𝛽-pinene, 𝛼-pinene, sabinene, myrcene, and limonene [63].

Oregano (Origanum vulgare L. subsp. vulgare) is a perennial herb native to the temperate regions of Europe and Asia. The main constituents of the essential oil in its leaves are carvacrol, p-cymene, c-terpinene, limonene, terpinene, ocimene, caryophyllene, β-bisabolene, linalool, and 4-terpineol [64]. Oregano is added for its slightly bitter flavor to poultry, fish, and other dishes. O. vulgare L. subsp. viridulum (Martrin-Donos) Nyman is also reported as a wild spice.

Sage (Salvia officinalis L.) is an evergreen subshrub native to the Mediterranean basin. The principal components in sage oil are 1,8-cineole, camphor, α-thujone, β-thujone, borneol, viridiflorol, caryophyllene and cineole [65,66]. Other Salvia species (S. glutinosa L., S. pratensis L., S. sclarea L., S. verbenaca L.) are also used.

Thyme (Thymus longicaulis C. Presl) is an evergreen subshrub native to southern Europe. Thyme essential oil consists of highly variable amounts of phenols, monoterpene hydrocarbons, and alcohols. Thymol is normally the main phenolic component followed by carvacrol [67]. The variability of the chemical components of Thymus species depends on several parameters including climatic, seasonal, and geographic conditions [68]. For Thymbra capitata (L.) Cav., Thymus polytrichus Kern. ex Borbás, T. pulegioides L. and T. spinulosus Ten are also reported to have the same uses of Th. longicaulis.

Lesser calamint (Clinopodium nepeta (L.) Kuntze subsp. nepeta) is an erect herbaceous perennial species, sometimes woody at the base, native to southern Europe. Its essential oil is rich in menthone, pulegone, piperitone, neomenthol, menthol, and limonene [69,70].

Winter savory (Satureja montana L.) is a perennial, semi-evergreen subshrub, native to warm temperate regions of southern Europe and Africa. The volatile fraction of winter savory essential oil is mainly characterized by oxygenated monoterpenes like thymol and carvacrol [71]; other important compounds are the monoterpenic hydrocarbons p-cymene and γ-terpinene [72].

Chives (Allium schoenoprasum L.) is a herb native to cold and temperate areas of Europe, Asia and North America; in Italy, it grows on mountains in central and northern regions. Green leaves of chives have sulfur compounds like 2-methyl-2-butenal, 2-methyl-2-pentenal, methyl-propyl disulfide and dipropyl disulfide. The major thiosulfinate compounds from chives are n-propyl groups, methyl and 1-propenyl groups [73].

Lemon balm (Melissa officinalis L.) is a perennial herbaceous plant native to central Europe, the Mediterranean Basin, and Central Asia, but now naturalized in the Americas and elsewhere [74] (WCSP 2020). The main components of the essential oil are citronellal, citral (citronellol, linalool) and geranial. In addition, this oil contains three terpinene, rosmarinic acid, and flavanol glycoside acids in low ratio [75,76].

Capers (Capparis spinosa L.) is a deciduous shrub native to Europe and Asia. The floral buds are harvested still closed in spring and summer and usually processed in brine. Cinnamaldehyde and benzaldehyde are the major constituents of the flavor profile of capers; of sulfur compounds, methyl-isothiocyanate is the main compound, followed by benzyl-isothiocyanate [77]. Rutin and kaempferol are the most abundant flavonol glucosides [78,79].

Garlic (Allium triquetrum L.; A. ursinum L.) is a bulb-forming herbaceous perennial plant, reported in the present review as a herb to flavor several dishes. Thiosulfinates are responsible for its characteristic pungent aroma and taste [80]. When fresh garlic is chopped or crushed, the enzyme alliinase converts alliin into allicin, which is responsible for the aroma of fresh garlic [81]. The typical aroma of cooked garlic is due to allyl methyl trisulfide [82]. Garlic is also considered a functional food and is widely used for its antibacterial, hypoglycemic, hypotensive and hypocholesterolemic properties [83]. It is used in folk phytotherapy also as a galactofuge and anthelminthic [84,85]. Other wild garlics reported as herbs in the present review are: A. lusitanicum Lam., A. neapolitanum Cirillo, A. roseum L., A. subhirsutum L. and A. vineale L.

4. Discussion

The use of some species is linked to their presence in the various regional territories. Gymnadenia rhellicani (Teppner and E.Klein) Teppner and E.Klein, for example, is an orchid confined to the Alps, at altitudes of 1000–2800 m [86]. This species is reported as a sweet flavoring only in two papers concerning alpine ethnobotany in Lombardy [17,23]. Similar considerations can be made for Pinus mugo Turra, a species growing at high altitudes and reported in the same papers. Pimpinella anisum L. is a casual alien distributed in a few regions, whose use is reported only for Abruzzo and Lombardy [16,23], while the range of P. anisoides V. Brig. is in central-southern Italy and its use is reported only in Calabria [38,49,50]. Allium schoenoprasum L. is not spontaneous in southern and insular regions and, although it is also frequently grown in gardens throughout Italy, its use is reported only for central and northern regions.

Many herbs and spices cited in the present review are also reported for their positive influence on health, especially for gastrointestinal disorders and more frequently as a digestive or appetizer (see Table 1). Many of these plants (e.g., Thymus spp., Mentha spp., Salvia spp., Foeniculum vulgare) are well known for their ability to stimulate the excretion of digestive enzymes and their carminative properties [66,68,87]. Many herbs and spices (e.g., Rosmarinus officinalis, Foeniculum vulgare, Allium spp.) have other nutraceutical properties and in particular are rich in antioxidant compounds. Many studies (e.g., [88,89]) have highlighted that a dietary antioxidant intake has a protective effect against free radical-related pathologies, such as cardiovascular diseases, diabetes, cancer and neurodegenerative diseases. Recent studies have highlighted that the protective effect of nutraceuticals is linked to the association of several phytochemical molecules at low concentrations, as it occurs naturally in the diet [90]. These plants can, therefore, be identified as functional foods (foods that have beneficial effects on one or more functions of the human organism that go beyond their mere nutritional properties [91,92]), and are consumed because they have a positive effect on health. Moreover, many of the food plants mentioned above are also reported for their herbal uses and are consumed as tea or used for topical applications.

Wild herbs and spices also play an important role in traditional gastronomy because they are used in the recipes of many local dishes, and in a certain way, they contribute to the cultural identity of some geographical areas. According to Jordana [93], in order to be traditional, a product must be linked to a territory and it must also be part of a set of traditions, which will necessarily ensure its continuity over time. Such wild species are, indeed, related to the preservation of family or local traditions and, as pointed out by Luczaj et al. [2] and Pardo-de-Santayana et al. [15], they could also be considered a way to diversify the daily diet.

According to Pieroni et al. [14], the potential of wild plants should be further explored for the possible economic opportunities that could be generated for local gatherers and communities. The diversification of production using such resources could be a socio-economically sustainable activity in areas with non-optimal farming conditions by contributing to population stabilization in rural areas [94]. Herbs are, therefore, also an opportunity to develop a healthy diet that combines gastronomy, health and sustainability.

In conclusion, the studies we included in this systematic review demonstrate that wild species used as herbs and spices enrich Italian folk cuisine and can represent an important resource for profitable, integrated local small-scale activities. Wild food species contribute to local food systems and to the local gastronomy, playing an important role in the economy of small communities.

The role of ethnobotanical studies is to avoid the loss of traditional knowledge concerning the use of food plants and, at the same time, provide the basis for developing new drugs from phytochemical and biochemical research.

In this regard, new field investigations aimed at specific knowledge of wild herbs and spices are desirable in Italy.

5. Materials and Methods

5.1. Geographical Context

Italy comprises some of the world’s most varied and scenic landscapes [95] and has an excursion of about 12 degrees of latitude (between 35° and 47° N). According to the Köppen climate classification [96], Italy is divided into ten types of climate [97]. The country, therefore, has an extreme variability of environments, ranging from coastal areas to the high altitudes of the Apennines and Alps. The whole Italian flora comprises 8195 native taxa, which is the highest number in Europe [98].

5.2. Data Collection

I searched both national and international journals for articles on the use of wild food plants in Italy from 1950 to 2020 and the first relevant publications date back to 1963. Publications were collected from online versions of the Science Citation Index, Elsevier Journal Finder, ISI web of knowledge, Scopus, and Google Scholar using the key words: ethnobotany, wild food plants, Italy. Further articles and books were gathered from previously collected papers. The criteria for article selection were defined a priori to avoid personal bias. In all, 106 articles were found in both the databases as well as the previously collected papers, 34 of which contained reports of wild plants specifically used for flavoring (excluding liqueurs and herbal teas). No data concerning plant lore are available for three regions (Veneto, Val D’Aosta and Trentino-Alto Adige), while no data about wild plants used as flavoring are obtainable from five regions (Puglia, Marche, Umbria, Molise and Lazio).

5.3. Data Analysis

Based on the results obtained, I set up a checklist including taxon, family, vernacular names, plant part(s) used, Italian regions for which the use of the species is reported, bibliographic citations, and therapeutic uses. The nomenclature follows the Plant List Database [99]. Families are organized according to APG IV [100] for angiosperms. When helpful, due to the recent changes in nomenclature, synonyms are reported in parentheses.

With a view to assessing the importance of herbs and spices in the study area, I used the Ethnobotanicity Index (EI), sensu Portères [101], which is the ratio, expressed as a percentage, between the number of plants used and total number of plants that constitute the flora of each region.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2223-7747/10/3/563/s1, List S1: Papers which contain reports of wild plants specifically used for flavoring followed by the number of species from each source.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All the relevant data used for the paper can be found in Table 1.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflict of interest.

References

- Zarbà, C.; Allegra, V.; Zarbà, A.S.; Zocco, G. Wild leafy plants market survey in Sicily: From local culture to food sustainability. Aims Agric. Food 2019, 4, 534–546. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luczaj, L.; Pieroni, A.; Tardío, J.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M.; Sõukand, R.; Svanberg, I.; Kalle, R. Wild food plant use in 21st century Europe, the disappearance of old traditions and the search for new cuisines involving wild edibles. Acta Soc. Bot. Pol. 2012, 81, 359–370. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rivera, D.; Obon, C.; Heinrich, M.; Inocencio, C.; Verde, A.; Fajardo, J. Gathered Mediterranean Food Plants–Ethnobotanical Investigations and Historical Development. In Local Mediterranean Food Plants and Nutraceuticals; Karger Publishers: Basel, Switzerland, 2006; Volume 59, pp. 18–74. [Google Scholar]

- Molina, M.; Tardío, J.; Aceituno-Mata, L.; Morales, R.; Reyes-García, V.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M. Weeds and food diversity: Natural yield assessment and future alternatives for traditionally consumed wild vegetables. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2014, 34, 44–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sharma, M.; Kumar, A. Ethnobotanical uses of medicinal plants: A review. Int. J. Life Sci. Pharm. Res. 2013, 3, 52–57. [Google Scholar]

- Rigat, M.; Gras, A.; D’Ambrosio, U.; Garnatje, T.; Parada, M.; Vallès, J. Wild food plants and minor crops in the Ripollès district (Catalonia, Iberian Peninsula): Potentialities for developing a local production, consumption and exchange program. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2016, 12, 49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Menendez-Baceta, G.; Aceituno-Mata, L.; Tardío, J.; Reyes-García, V.; Pardo-de-Santayana, M. Wild edible plants traditionally gathered in Gorbeialdea (Biscay, Basque Country). Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2012, 59, 1329–1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kujawska, M.; Łuczaj, Ł. Wild edible plants used by the Polish community in Misiones, Argentina. Hum. Ecol. 2015, 43, 855–869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cambridge Dictionary Published in Internet. Available online: www.dictionary.cambridge.org (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Oxford Learner’s Dictionary Published in Internet. Available online: www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com/definition/american_english (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Merriam-Webster Dictionary Published in Internet. Available online: www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary (accessed on 9 December 2020).

- Enciclopedia Treccani Published in Internet. Available online: www.treccani.it (accessed on 28 December 2020).

- Van der Veen, M.; Morales, J. The Roman and Islamic spice trade: New archaeological evidence. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 167, 54–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieroni, A.; Nebel, S.; Santoro, R.F.; Heinrich, M. Food for two seasons: Culinary uses of non-cultivated local vegetables and mushrooms in a south Italian village. Int. J. Food Sci. Nutr. 2005, 56, 245–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pardo-De-Santayana, M.; Tardío, J.; Blanco, E.; Carvalho, A.M.; Lastra, J.J.; Miguel, E.S.; Morales, R. Traditional knowledge of wild edible plants used in the northwest of the Iberian Peninsula (Spain and Portugal): A comparative study. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2007, 3, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Idolo, M.; Motti, R.; Mazzoleni, S. Ethnobotanical and phytomedicinal knowledge in a long-history protected area, the Abruzzo, Lazio and Molise National Park (Italian Apennines). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2010, 127, 379–395. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitalini, S.; Iriti, M.; Puricelli, C.; Ciuchi, D.; Segale, A.; Fico, G. Traditional knowledge on medicinal and food plants used in Val San Giacomo (Sondrio, Italy)—An alpine ethnobotanical study. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 145, 517–529. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Tuttolomondo, T.; Licata, M.; Leto, C.; Savo, V.; Bonsangue, G.; Gargano, M.L.; Venturella, G.; La Bella, S. Ethnobotanical investigation on wild medicinal plants in the Monti Sicani Regional Park (Sicily, Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 153, 568–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leto, C.; Tuttolomondo, T.; La Bella, S.; Licata, M. Ethnobotanical study in the Madonie Regional Park (Central Sicily, Italy)—Medicinal use of wild shrub and herbaceous plant species. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 146, 90–112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarrera, P.M.; Savo, V.; Caneva, G. Traditional uses of plants in the Tolfa–Cerite–Manziate area (Central Italy). Ethnobiol. Lett. 2015, 6, 119–161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarrera, P.M.; Salerno, G.; Caneva, G. Food, flavouring and feed plant traditions in the Tyrrhenian sector of Basilicata, Italy. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2006, 2, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lentini, F.; Venza, F. Wild food plants of popular use in Sicily. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2007, 3, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vitalini, S.; Puricelli, C.; Mikerezi, I.; Iriti, M. Plants, people and traditions: Ethnobotanical survey in the Lombard Stelvio national park and neighbouring areas (Central Alps, Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2015, 173, 435–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Leporatti, M.L.; Guarrera, P.M. Ethnobotanical remarks in Capitanata and Salento areas (Puglia, southern Italy). Etnobiología 2007, 5, 51–64. [Google Scholar]

- Mattalia, G.; Quave, C.L.; Pieroni, A. Traditional uses of wild food and medicinal plants among Brigasc, Kyé, and Provençal communities on the Western Italian Alps. Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2013, 60, 587–603. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motti, R.; Bonanomi, G.; Lanzotti, V.; Sacchi, R. The Contribution of Wild Edible Plants to the Mediterranean Diet: An Ethnobotanical Case Study along the Coast of Campania (Southern Italy). Econ. Bot. 2020, 74, 249–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uncini Manganelli, R.E.; Camangi, F.; Tomei, P.E.; Oggiano, N. L’uso delle Erbe Nella Tradizione Rurale della Toscana; ARSIA-Regione Toscana: Firenze, Italy, 2002; Volume 1–2. [Google Scholar]

- Sansanelli, S.; Tassoni, A. Wild food plants traditionally consumed in the area of Bologna (Emilia Romagna region, Italy). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2014, 10, 69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pieroni, A.; Giusti, M.E. Alpine ethnobotany in Italy: Traditional knowledge of gastronomic and medicinal plants among the Occitans of the upper Varaita valley, Piedmont. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2009, 5, 32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bellia, G.; Pieroni, A. Isolated, but transnational: The glocal nature of Waldensian ethnobotany, Western Alps, NW Italy. J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2015, 11, 37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pieroni, A. Gathered wild food plants in the upper valley of the Serchio River (Garfagnana), Central Italy. Econ. Bot. 1999, 53, 327–341. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coassini Lokar, L.; Poldini, L.; Angeloni Rossi, G. Appunti di etnobotanica del Friuli-Venezia Giulia. Gortania-Atti. Del Mus. Friul. Di Stor. Nat. 1983, 4, 101–152. [Google Scholar]

- Signorini, M.A.; Piredda, M.; Bruschi, P. Plants and traditional knowledge: An ethnobotanical investigation on Monte Ortobene (Nuoro, Sardinia). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2009, 5, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Cornara, L.; La Rocca, A.; Marsili, S.; Mariotti, M.G. Traditional uses of plants in the Eastern Riviera (Liguria, Italy). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2009, 125, 16–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savo, V.; Salomone, F.; Bartoli, F.; Caneva, G. When the local cuisine still incorporates wild food plants: The unknown traditions of the Monti Picentini Regional Park (Southern Italy). Econ. Bot. 2019, 73, 28–46. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Montesano, V.; Negro, D.; Sarli, G.; De Lisi, A.; Laghett, I.G.; Hammer, K. Notes about the uses of plants by one of the last healers in the Basilicata region (South Italy). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2012, 8, 15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Menale, B.; Amato, G.; Di Prisco, C.; Muoio, R. Traditional uses of plants in north-western Molise (Central Italy). Delpinoa 2006, 48, 29–36. [Google Scholar]

- Pieroni, A.; Nebel, S.; Quave, C.; Münz, H.; Heinrich, M. Ethnopharmacology of liakra: Traditional weedy vegetables of the Arbëreshë of the Vulture area in southern Italy. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2002, 81, 165–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattalia, G.; Corvo, P.; Pieroni, A. The virtues of being peripheral, recreational, and transnational: Local wild food and medicinal plant knowledge in selected remote municipalities of Calabria, Southern Italy. Ethnobot. Res. Appl. 2020, 19, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mautone, M.; de Martino, L.; de Feo, V. Ethnobotanical research in Cava de’Tirreni area, Southern Italy. about the uses of plants by one of the last healers in the Basilicata region (South Italy). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2019, 15, 50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arcidiacono, S.; Costa, R.; Marletta, G.; Pavone, P.; Napoli, M. Usi popolari delle piante selvatiche nel territorio di Villarosa (EN–Sicilia Centrale). Quad. Bot. Amb. Appl. 2010, 1, 95–118. [Google Scholar]

- Motti, R.; Motti, P. An ethnobotanical survey of useful plants in the agro Nocerino Sarnese (Campania, southern Italy). Hum. Ecol. 2017, 45, 865–878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarrera, P.M. Le piante nelle tradizioni popolari della Sicilia. Erbor. Domani 2009, 1, 46–55. [Google Scholar]

- Cornara, L.; La Rocca, A.; Terrizzano, L.; Dente, F.; Mariotti, M.G. Ethnobotanical and phytomedical knowledge in the North-Western Ligurian Alps. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2014, 155, 463–484. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salerno, G.; Guarrera, P.M. Ricerche etnobotaniche nel Parco Nazionale del Cilento e Vallo di Diano: Il territorio di Castel San Lorenzo (Campania, Salerno). Inf. Bot. Ital. 2008, 40, 165–181. [Google Scholar]

- Arcidiacono, S.; Napoli, M.; Oddo, G.; Pavone, P. Piante selvatiche d’uso popolare nei territori di Alcara Li Fusi e Militello Rosmarino (Messina, NE Sicilia). Quad. Bot. Amb. App. 2007, 18, 105–146. [Google Scholar]

- Nebel, S.; Pieroni, A.; Heinrich, M. Ta chòrta: Wild edible greens used in the Graecanic area in Calabria, Southern Italy. Appetite 2006, 47, 333–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motti, R.; Antignani, V.; Idolo, M. Traditional plant use in the Phlegraean fields Regional Park (Campania, southern Italy). Hum. Ecol. 2009, 37, 775–782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Atzei, A.D.; Orioni, S.; Sotgiu, R. Contributo alla conoscenza degli usi etnobotanici nella Gallura (Sardegna). Boll. Soc. Sarda Sci. Nat. 1991, 28, 137–177. [Google Scholar]

- Maruca, G.; Spampinato, G.; Turiano, D.; Laghetti, G.; Musarella, C.M. Ethnobotanical notes about medicinal and useful plants of the Reventino Massif tradition (Calabria region, Southern Italy). Genet. Resour. Crop Evol. 2019, 66, 1027–1040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mattalia, G.; Sõukand, R.; Corvo, P.; Pieroni, A. Blended divergences: Local food and medicinal plant uses among Arbëreshë, Occitans, and autochthonous Calabrians living in Calabria, Southern Italy. Plant Biosyst. 2020, 154, 615–626. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Di Novella, R.; di Novella, N.; de Martino, L.; Mancini, E.; de Feo, V. Traditional plant use in the National Park of Cilento and Vallo di Diano, Campania, Southern Italy. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2013, 145, 328–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Camejo-Rodrigues, J.; Ascensao, L.; Bonet, M.À.; Valles, J. An ethnobotanical study of medicinal and aromatic plants in the Natural Park of “Serra de São Mamede” (Portugal). J. Ethnopharmacol. 2003, 89, 199–209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guarrera, P.M.; Lucchese, F.; Medori, S. Ethnophytotherapeutical research in the high Molise region (Central-Southern Italy). J. Ethnobiol. Ethnomed. 2008, 4, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Javed, R.; Hanif, M.A.; Ayub, M.A.; Rehman, R. Fennel. In Medicinal Plants of South Asia; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2020; pp. 241–256. [Google Scholar]

- Diao, W.R.; Hu, Q.P.; Zhang, H.; Xu, J.G. Chemical composition, antibacterial activity and mechanism of action of essential oil from seeds of fennel (Foeniculum vulgare Mill.). Food Control. 2014, 35, 109–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rahimmalek, M.; Maghsoudi, H.; Sabzalian, M.R.; Ghasemi Pirbalouti, A. Variability of essential oil content and composition of different Iranian fennel (Foeniculum vulgare Mill.) accessions in relation to some morphological and climatic factors. J. Agric. Sci. Tech. 2014, 16, 1365–1374. [Google Scholar]

- Senatore, F.; Oliviero, F.; Scandolera, E.; Taglialatela-Scafati, O.; Roscigno, G.; Zaccardelli, M.; De Falco, E. Chemical composition, antimicrobial and antioxidant activities of anethole-rich oil from leaves of selected varieties of fennel [Foeniculum vulgare Mill. ssp. vulgare var. azoricum (Mill.) Thell]. Fitoterapia 2013, 90, 214–219. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caputo, L.; Nazzaro, F.; Souza, L.F.; Aliberti, L.; De Martino, L.; Fratianni, F.; De Feo, V. Laurus nobilis: Composition of essential oil and its biological activities. Molecules 2017, 22, 930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Doymaz, İ. Thin-Layer Drying of Bay Laurel Leaves (L aurus nobilis L.). J. Food Process. Preserv. 2014, 38, 449–456. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.; Wu, N.; Zu, Y.G.; Fu, Y.J. Antioxidative activity of Rosmarinus officinalis L. essential oil compared to its main components. Food Chem. 2008, 108, 1019–1022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farjon, A. A Monograph of Cupressaceae and Sciadopitys; Royal Botanic Gardens: Kew, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar]

- Gari, M.T.; Admassu, S.; Asfaw, B.T.; Abebe, T.; Jayakumar, M. Review on: Extraction of essential oil (Gin Flavor) from Juniper Berries (Juniperus communis). Emerg. Trends Chem. Eng. 2020, 7, 19–28. [Google Scholar]

- Caballero, B.; Finglas, P.; Toldrá, F. Encyclopedia of Food and Health; Academic Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Ghorbani, A.; Esmaeilizadeh, M. Pharmacological properties of Salvia officinalis and its components. J. Tradit Complement Med. 2017, 7, 433–440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miraj, S.; Kiani, S. A review study of therapeutic effects of Salvia officinalis L. Der Pharm. Lett. 2016, 8, 299–303. [Google Scholar]

- Senatore, F. Influence of harvesting time on yield and composition of the essential oil of a thyme (Thymus pulegioides L.) growing wild in Campania (Southern Italy). J. Agric. Food Chem. 1996, 44, 1327–1332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tohidi, B.; Rahimmalek, M.; Trindade, H. Review on essential oil, extracts composition, molecular and phytochemical properties of Thymus species in Iran. Ind. Crops Prod. 2019, 134, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacifico, S.; Galasso, S.; Piccolella, S.; Kretschmer, N.; Pan, S.P.; Marciano, S.; Bauer, R.; Monaco, P. Seasonal variation in phenolic composition and antioxidant and anti–inflammatory activities of Calamintha nepeta (L.) Savi. Int. Food Res. J. 2015, 69, 121–132. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alan, S.; Kürkçüoglu, M.; Baser, K.H.C. Composition of essential oils of Calamintha nepeta (L.) Savi subsp. nepeta and Calamintha nepeta (L.) Savi subsp. glandulosa (Req.) PW Ball. Asian J. Chem. 2011, 23, 2357. [Google Scholar]

- Maccelli, A.; Vitanza, L.; Imbriano, A.; Fraschetti, C.; Filippi, A.; Goldoni, P.; Menghini, L. Satureja montana L. Essential oils: Chemical profiles/phytochemical screening, antimicrobial activity and o/w nanoemulsion formulations. Pharmaceutics 2020, 12, 7. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Skočibušić, M.; Bezić, N. Phytochemical analysis and in vitro antimicrobial activity of two Satureja species essential oils. Phytother. Res. 2004, 18, 967–970. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Singh, V.; Chauhan, G.; Krishan, P.; Shri, R. Allium schoenoprasum L.: A review of phytochemistry, pharmacology and future directions. Nat. Prod. Res. 2018, 32, 2202–2216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- WCSP, World Checklist of Selected Plant Families. Facilitated by the Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew. Published on the Internet. Available online: http://wcsp.science.kew.org/ (accessed on 8 December 2020).

- Moradkhani, H.; Sargsyan, E.; Bibak, H.; Naseri, B.; Sadat-Hosseini, M.; Fayazi-Barjin, A.; Meftahizade, H. Melissa officinalis L. a valuable medicine plant: A review. J. Med. Plant Res. 2010, 4, 2753–2759. [Google Scholar]

- De Sousa, A.C.; Gattass, C.R.; Alviano, D.S.; Alviano, C.S.; Blank, A.F.; Alves, P.B. Melissa officinalis L. essential oil: Antitumoral and antioxidant activities. J. Pharm. Pharmacol. 2004, 56, 677–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Romeo, V.; Ziino, M.; Giuffrida, D.; Condurso, C.; Verzera, A. Flavour profile of capers (Capparis spinosa L.) from the Eolian Archipelago by HS-SPME/GC–MS. Food Chem. 2007, 101, 1272–1278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giuffrida, D.; Salvo, F.; Ziino, M.; Toscano, G.; Dugo, G. Initial investigation on some chemical constituents of capers (Capparis spinosa L.) from the island of Salina. Ital. J. Food Sci. 2002, 14, 25. [Google Scholar]

- Brevard, H.; Brambilla, M.; Chaintreau, A.; Marion, J.P.; Diserens, H. Occurrence of elemental sulphur in capers (Capparis spinosa L.) and first investigation of the flavour profile. Flavour Fragr. J. 1992, 7, 313–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzotti, V. Bioactive polar natural compounds from garlic and onions. Phytochem. Rev. 2012, 11, 179–196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iranshahi, M. A review of volatile sulfur-containing compounds from terrestrial plants: Biosynthesis, distribution and analytical methods. J. Essent. Oil Res. 2012, 24, 393–434. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Zhan, P.; Tian, H.; Wang, P.; Ji, Y. Effects of drying time on the aroma of garlic (Allium sativum L.) flavoring powder. Flavour Fragr J. 2020, 36, 99–110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lanzotti, V. The analysis of onion and garlic. J. Chromatogr. A 2006, 1112, 3–22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Motti, R.; Bonanomi, G.; Emrick, S.; Lanzotti, V. Traditional Herbal Remedies Used in women’s Health Care in Italy: A Review. Hum. Ecol. 2019, 47, 941–972. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Motti, R.; Ippolito, F.; Bonanomi, G. Folk phytotherapy in paediatric health care in central and southern Italy: A review. Hum. Ecol. 2018, 46, 573–585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rankou, H. Gymnadenia rhellicani. The IUCN Red List of Threatened Species 2011: E.T175979A7161210. Available online: https://dx.doi.org/10.2305/IUCN.UK.2011-2.RLTS.T175979A7161210.en (accessed on 25 November 2020).

- Platel, K.; Srinivasan, K. Digestive stimulant action of spices: A myth or reality? Indian J. Med. Res. 2004, 119, 167. [Google Scholar]

- Vitaglione, P.; Morisco, F.; Caporaso, N.; Fogliano, V. Dietary antioxidant compounds and liver health. Crit. Rev. Food Sci. Nutr. 2005, 44, 575–586. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Colarusso, L.; Serafini, M.; Lagerros, Y.T.; Nyren, O.; La Vecchia, C.; Rossi, M.; Ye, W.; Tavani, A.; Adami, H.-O.; Grotta, A.; et al. Dietary antioxidant capacity and risk for stroke in a prospective cohort study of Swedish men and women. Nutrition 2017, 33, 234–239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savo, V.; Salomone, F.; Mattoni, E.; Tofani, D.; Caneva, G. Traditional salads and soups with wild plants as a source of antioxidants: A comparative chemical analysis of five species growing in central Italy. Evid. -Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2019, 2019, 1–12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martirosyan, D.M.; Singh, J. A new definition of functional food by FFC: What makes a new definition unique? Funct. Food Health Dis. 2015, 5, 209–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bacchetta, L.; Visioli, F.; Cappelli, G.; Caruso, E.; Martin, G.; Nemeth, E.; van Raamsdonk, L.; Mariani, F.; on behalf of the Eatwild Consortium. A manifesto for the valorization of wild edible plants. J. Ethnopharmacol. 2016, 191, 180–187. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jordana, J. Traditional foods: Challenges facing the European food industry. Int. Food Res. J. 2000, 33, 147–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gracia, A.; Sánchez, A.M.; Jurado, F.; Mallor, C. Making Use of Sustainable Local Plant Genetic Resources: Would Consumers Support the Recovery of a Traditional Purple Carrot? Sustainability 2020, 12, 6549. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Clark, M. Italy. Available online: https://www.britannica.com/place/Italy (accessed on 1 January 2021).

- Köppen, W. Das Geographische System der Klimate. In Handbuch der Klimatologie; Verlag von Gebrüder Borntraeger: Berlin, Germany, 1936; Volume 1. [Google Scholar]

- Pinna, M. Contributo alla classificazione del clima d’Italia. Riv. Geogr. Ital. 1970, 77, 129–152. [Google Scholar]

- Bartolucci, F.; Peruzzi, L.; Galasso, G.; Albano, A.; Alessandrini, A.; Ardenghi, N.M.G.; Astuti, G.; Bacchetta, G.; Ballelli, S.; Banfi, E.; et al. An updated checklist of the vascular flora native to Italy. Plant Biosyst. Int. J. Deal. All Asp. Plant Biol. 2018, 152, 179–303. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- The Plant List Database. Version 1.1 Published on the Internet. 2013. Available online: http://www.theplantlist.org (accessed on 7 October 2020).

- Stevens, P.F. Angiosperm Phylogeny Website, Version 14. 2015. Available online: http://www.mobot.org/MOBOT/research/APweb/ (accessed on 6 October 2020).

- Portères, R. Ethnobotanique Générale Paris: Laboratoire d’Ethnobotanique et Ethnozoologie; Muséum National d’Histoire Naturelle: Paris, France, 1970. [Google Scholar]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).