Abstract

Amino acid transporters (AATs) are integral membrane proteins and have several functions, including transporting amino acids across cellular membranes. They are critical for plant growth and development. This study comprehensively identified AAT-encoding genes in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum), which is an important vegetable crop and serves as a model for fleshy fruit development. In this study, 88 genes were identified in the S. lycopersicum genome and grouped into 12 subfamilies, based on previously identified AATs in Arabidopsis, rice (Oryza sativa), and potato (Solanum tuberosum) plants. Chromosomal localization revealed that S. lycopersicum AAT (SlAAT) genes are distributed on the 12 S. lycopersicum chromosomes. Segmental duplication events contribute mainly to the expansion of SlAAT genes and about 32% (29 genes) of SlAAT genes were found to originate from this type of event. Expression profiles of SlAAT genes in various tissues of S. lycopersicum using RNA sequencing data from the Tomato Functional Genomics Database showed that SlAAT genes exhibited tissue-specific expression patterns. Comprehensive data generated in this study will provide a platform for further studies on the SlAAT gene family and will facilitate the functional characterization of SlAAT genes.

1. Introduction

Tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) has great global commercial importance owing to its nutritional value and serves as a model for fleshy fruit development and as a reference species for plants in the Solanaceae family. Several genome-wide studies have identified 63, 87, 23, 189, and 72 genes encoding amino acid transporters (AATs) in Arabidopsis thaliana, Oryza sativa, Selaginella, Glycine max, and Solanum tuberosum, respectively [1,2,3,4,5]. Although AATs have been studied in several plant species, there is limited information available about AATs in S. lycopersicum.

AATs are integral membrane proteins, which mediate the nitrogen allocation between source and sink [6] in plants. The phloem sap is rich in amino acids and they are responsible for procuring the organic [2]; nitrogen that is necessary for plant growth and development [7]. Furthermore, AATs play fundamental roles in plant physiological processes such as defense against pathogens and resistance to abiotic stresses.

AATs are divided into two families; the first is amino acid/auxin permease (AAAP), which is in turn sub-grouped into eight subfamilies, including amino acid permease (AAP), lysine/histidine transporter (LHT), γ-aminobutyric acid (GABA) transporter (GAT), proline transporter (ProT), like-auxin influx carriers (LAX), aromatic and neutral amino acid transporter (ANT), vesicular aminergic-associated transporter (VAAT), and amino acid transporter-like proteins (ATL) [8]. The second family comprises of amino acid-polyamine-choline (APC) transporters, which in turn is sub-grouped into four subfamilies, including amino acid/choline transporters (ACT), tyrosine-specific transporter (TTP), cationic amino acid transporter (CAT), and polyamine H+ co-transporters (PHS) [9]. In addition, a new subfamily has been added to the AAT superfamily called Usually Multiple Amino Acids Move In and Out Transporters (UMAMIT) [10].

A few studies have functionally characterized the members of the AAT superfamily in plants. Eight AAPs have been identified in Arabidopsis, which are localized in the plasma membrane and involved in the H+-coupled amino acid uptake system [11]. AAP1 and AAP2 in Arabidopsis, the first two AATs to be characterized, have different substrate specificity with high expression in siliques of Arabidopsis, suggesting their involvement in supplying the seeds with organic nitrogen [12]. AAP3, AAP4, and AAP5 were later isolated from Arabidopsis with broad substrate specificities and AAP5 was found to participate in amino acid transport in the developing embryo [13]. Arabidopsis thaliana AAP7 (AtAAP7) is still not functionally characterized. AtAAP6 and AtAAP8 are involved in high-affinity amino acid transport, since AAP8 imports organic nitrogen into developing seeds and AAP6 is expressed in xylem, which has low concentrations of amino acids [14]. Similar to Arabidopsis, eight members of AAPs have been identified in S. tuberosum [5], and 19 have been identified in O. sativa [1]. AAPs in other plant species have also been functionally characterized. For example, AAP1 is expressed in the leaves and is involved in the long-distance transport of amino acids in S. tuberosum [15]. Three primases, including VfAAP1, VfAAP3, and VfAAP4 were isolated from Vicia faba L. and have been shown to transport a broad range of amino acids [16].

Ten LHTs (AtLHT1–10) have been identified in Arabidopsis. They were found to be localized in the plasma membrane and were found to import organic nitrogen into the roots, mesophyll cells [17], and the cells of reproductive floral tissue [18]. AtLHT1 together with AtAAP5 are involved in the uptake of neutral, acidic, and basic amino acids from the soil when amino acid levels in the nutrient solutions (or soil) are low [19,20].

Unlike AAPs and LHTs, the only proteinogenic amino acid transported by ProTs is proline [21]. However, studies have shown that ProTs are responsible for transporting glycine betaine and GABA [22]. Three ProTs (AtProT1, AtProT2, AtProT3) were identified in Arabidopsis and it was shown that despite the similar localization of the three transporters in the plasma membrane and similar affinity to glycine betaine, each transporter has a different role in Arabidopsis [22]. For example, AtProT1 is highly expressed in the phloem, suggesting its involvement in long-distance transport of compatible solutes. AtProT2 is active in the roots, while AtProT3 is active in the epidermal cells of the leaves [22].

ProT1 in S. lycopersicum is a general transporter for compatible solutes [23] and transports proline to roots even under salt-stress conditions [24]. Regarding GATs in Arabidopsis, it was revealed that AtGAT1 has a high affinity to GABA and is localized in the plasma membrane [25]. In addition, it is highly expressed in flowers under elevated GABA conditions, such as wounding and senescence [25].

Aux1 mutant Arabidopsis plants show defects in the root gravitropic response, and AtAUX1 is expressed in the columella, lateral root cap, epidermis, and stele tissues of the primary root [26]. AtAUX1 together with AtPIN2 (auxin exporter) regulate root gravitropism [27], and AtAUX1 promotes lateral root formation and phyllotactic pattern in Arabidopsis [28]. In Arabidopsis, the AUX1 gene belongs to a small family consisting of four members, including AUX1 and three LAX genes (LAX1, 2, and 3) [29], while there are five AUX/LAX transporters in O. sativa [30]. Regarding ANT transporters, only AtANT1 was characterized in Arabidopsis, which transports arginine, indole-3-acetic acid, and 2,4-dichlorophenoxyacetic acid [31]. Of CAT transporters, nine members have been functionally characterized in Arabidopsis with varying affinities and functions [32]. For example, AtCAT5 is a high-affinity basic amino acid transporter and is involved in reuptake of the leaking amino acids at the leaf margin, while AtCAT2 is involved in long-sought vacuolar amino acid transport [32]. Recently, six CAT members were identified and characterized in Camellia sinensis and their expression was revealed to be sensitive to abiotic stress [33]. In Arabidopsis, a bidirectional amino acid transporter (BAT), which performs both exporting and importing activities, was reported to exhibit transport activity for alanine, arginine, glutamate, and lysine [34].

Since the functions of S. lycopersicum AATs are not fully studied, we aimed to elucidate the entire members of AAT gene superfamily in S. lycopersicum. In this study, a genome-wide identification and phylogenetic analysis of S. lycopersicum AAT (SlAAT) genes were performed for AAT superfamily classification and to explore the evolution of this gene superfamily. In addition, the features of the exon-intron structures, patterns of the conserved motifs, and duplication events, including tandem and segmental duplications within the tomato genome that likely contribute to the expansion of the SlAAT superfamily were explored. The resulting data will be useful in studies on the biological functions of each gene in the SlAAT superfamily.

2. Results

2.1. Identification of SlAATs in the S. lycopersicum Genome

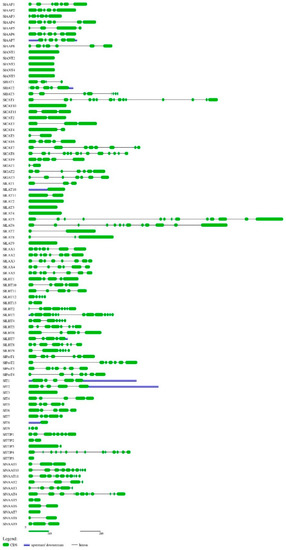

Using ATTs of Arabidopsis thaliana, O. sativa, and S. tuberosum as queries in BLAST search at SGN with ‘amino acid transporter’ and ‘amino acid permease’ as keywords, we identified 88 members of SlAATs. All the retrieved protein sequences of SlAATs were subjected to InterProScan (http://www.ebi.ac.uk/Tools/InterProScan/ (accessed on 31 January 2021)), and all the candidate proteins were found to contain AAT domain(s). Information about locus identity number of SlAATs assigned by SGN (Solanaceae Genomics Network, http://solgenomics.net/SOL (accessed on 31 January 2021)), the given nomenclature of S. lycopersicum AATs, number of intron(s) in the SlAAT genes, length of the ORF for SlAATs, protein characterization of SlAATs (amino acid length, MW, pI), and genomic location are presented in Table 1. The intron number ranged from 1 to 13 and the length of the ORF for SlAATs ranged from 267 to 3376 bp. It was observed that each subfamily member shared a nearly similar gene structure and intron numbers. For example, members of ProT subfamily contained six introns and an ORF length of 1473–1828 bps. The intron-exon regions in each genomic sequence of SlAAT are illustrated in Figure 1.

Table 1.

The general information and sequence characterization of 88 SlAAT genes.

Figure 1.

Exon-intron structures of the identified SlAAT genes. The graphic representation of the optimized gene model displayed using Gene Structure Display Server (GSDS) (for interpretation of the references to colors in this figure, the reader is referred to the web version of this article). Green boxes represent exons. The black solid lines connecting two exons represent introns, and the blue boxes represent upstream/downstream region of SlAAT genes. AAP, amino acid permease; ANT, aromatic and neutral amino acid transporter; ATL, amino acid transporter-like proteins; BAT, bidirectional amino acid transporter; CAT, cationic amino acid transporter; GAT, γ-aminobutyric acid transporter; LAT, L-type amino acid transporter; LAX, like-auxin influx carrier; LHT, lysine/histidine transporter; ProT, proline transporter; TTP, tyrosine-specific transporter; VAAT, vesicular aminergic-associated transporter.

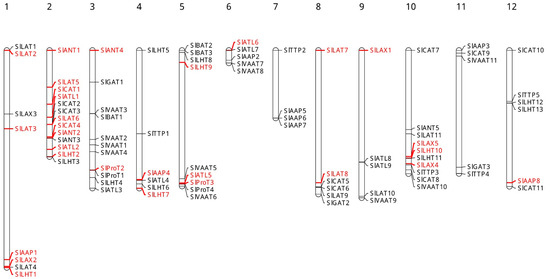

The number of transmembrane regions (Table 1), which were predicted by the TMHMM Server, were found to range from 2 to 18 and some members of each subfamily of SlAATS shared a similar number of transmembrane regions. Using the information available in the SGN about SlAATs, it was determined that SlAAT genes are distributed in all the 12 chromosomes in S. lycopersicum (Figure 2). An uneven distribution of SlAAT genes on the 12 chromosomes was observed; for example, chromosome 2 contained 13 SlAAT genes, while chromosome 7 contains four SlAAT genes. The gene duplication data obtained from PGDD (Plant Genome Duplication Database, http://chibba.agtec.uga.edu/duplication (accessed on 31 January 2021)) (S. lycopersicum vs. S. lycopersicum) revealed that 29 SlAAT genes originate from the duplication events and there are 16 gene pairs of SlAATs (Table 2). Examining the 16 gene pairs according to the criterion of tandem duplication, all the duplication events were characterized to be segmental duplication. Thus, the divergence time ranged from 39.70 to 240.07 May. According to the phylogenetic relationships, the proteins of duplicated genes are close to each other and have higher sequence similarity; for example, the sequence similarity between SlLAX2 and SlLAX5 was found to be 93.15%. Only in two cases, the similarity between the proteins of duplicated genes was found to be below 50%; the similarity between SlLHT1 and SlLHT10 was 38.84%, and that between SlCAT1 and SlCAT4 was 39.19%. To study the selection pressure among the SlAAT duplicated gene pairs, Ka/Ks was calculated (Table 2) and the results revealed that they evolved under purifying selection (Ka/Ks < 1).

Figure 2.

Chromosomal localization of SlAAT genes. Respective chromosome numbers are indicated at the top of each bar. Gene duplication events of SlAAT genes marked in red. (For interpretation of the references to color in this figure, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.) AAP, amino acid permease; ANT, aromatic and neutral amino acid transporter; ATL, amino acid transporter-like proteins; BAT, bidirectional amino acid transporter; CAT, cationic amino acid transporter; GAT, γ-aminobutyric acid transporter; LAT, L-type amino acid transporter; LAX, like-auxin influx carriers; LHT, lysine/histidine transporter; ProT, proline transporter; TTP, tyrosine-specific transporter; VAAT, vesicular aminergic-associated transporter.

Table 2.

The gene duplication data obtained from the Plant Genome Duplication Database (PGDD).

2.2. Phylogenetic Analysis and Classification of the SlAATs

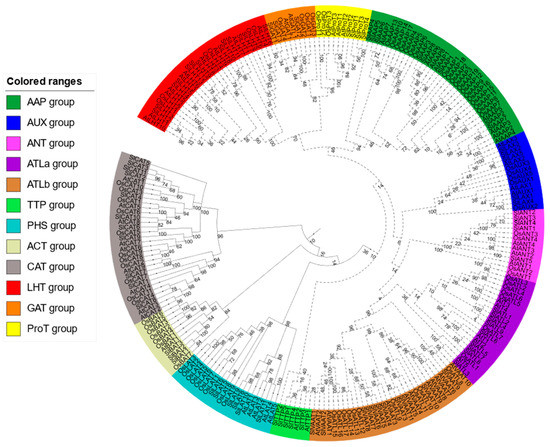

The phylogenetic tree, which that was constructed after the alignment of AAT amino acid sequences of S. lycopersicum, O. sativa and Arabidopsis thaliana, revealed that the 88 SlAATs could be clustered into 12 clades (Figure 3). These SlAATs can be classified into two main superfamilies: AAAP and APC. The AAAP family can be classified into eight subfamilies: AAP, LHT, GAT, ProT, LAX, ANT, VAAT, and ATL. On the other hand, the APC family can be classified into four subfamilies according to phylogenetic tree: ACT, TTP, CAT, and PHS.

Figure 3.

Phylogenetic tree of protein sequences of the AATs of Solanum lycopersicum, Oryza sativa, and Arabidopsis thaliana generated using MEGA 6.0 software with the Maximum Likelihood method and Whelan and Goldman model [35]. The bootstrap consensus tree inferred from 500 replicates is taken to represent the evolutionary history of the SlAATs analyzed. The tree was divided into 12 subgroups, marked by different color backgrounds. AAP, amino acid permease; ANT, aromatic and neutral amino acid transporter; ATL, amino acid transporter-like proteins; BAT, bidirectional amino acid transporter; CAT, cationic amino acid transporter; GAT, γ-aminobutyric acid transporter; LAT, L-type amino acid transporter; LAX, like-auxin influx carriers; LHT, lysine/histidine transporter; ProT, proline transporter; TTP, tyrosine-specific transporter; VAAT, vesicular aminergic-associated transporter; JTT, Jones–Taylor–Thornton. Dashed lines: AAAP family, Solid lines: APC family.

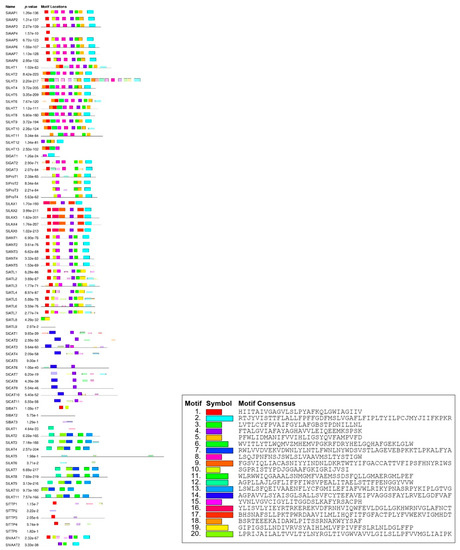

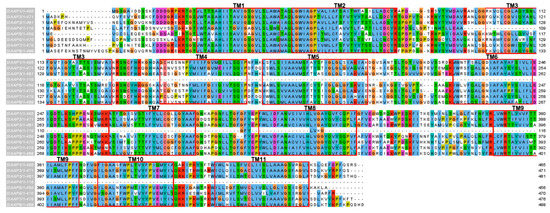

Motif analysis using MEME showed that each subfamily has a similar motif and nearly the same their number (Figure 4). For example, all members of the AAP subfamily were found to have the same motifs. In addition, some motifs are more common in one family than the other. For example, motif 1, 2, and 5 are likely to be more common in the AAAP family than the APC family. On the other hand, some motifs were specific to one subfamily; for example, motif 17 was specific to the LAX subfamily and motif 19 was specific to the ATL subfamily. Analysis of the transmembrane region conservation, revealed that most of the transmembrane regions were highly conserved. The alignment of AAP amino acid sequences and the transmembrane conserved region are illustrated as an example in Figure 5.

Figure 4.

Protein motifs of SlAATs. Each colored box represents a specific motif in the protein identified using the MEME motif search tool (For interpretation of the references to colors in this figure, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.) AAP, amino acid permease; ANT, aromatic and neutral amino acid transporter; ATL, amino acid transporter-like proteins; BAT, bidirectional amino acid transporter; CAT, cationic amino acid transporter; GAT, γ-aminobutyric acid transporter; LAT, L-type amino acid transporter; LAX, like-auxin influx carriers; LHT, lysine/histidine transporter; ProT, proline transporter; TTP, tyrosine-specific transporter; VAAT, vesicular aminergic-associated transporter.

Figure 5.

Multiple sequence alignment and TM region of SlAAPs with the default color scheme used for alignments in Clustal X [36]. The TM regions are marked by red. (For interpretation of the references to colors in this figure, the reader is referred to the web version of this article.) TM, transmembrane; AAP, amino acid permease.

2.3. Expression Analysis of SlAAT Genes Based on RNA-Seq Data

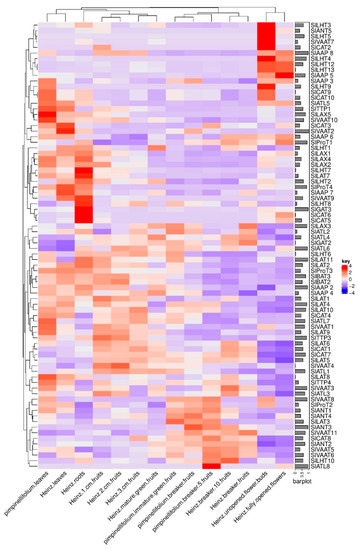

The RNA-Seq data from various tissues during vegetative and reproductive developmental stages of the tomato cultivar S. lycopersicon ‘Heinz’ and the wild relative S. pimpinellifolium was used to study the expression of SlATT genes (Figure 6). According to the column dendrogram, it was observed that there is a similar expression pattern between the leaves of both pimpinellifolium and S. lycopersicon ‘Heinz, S. lycopersicon ‘Heinz 1 cm fruit, S. lycopersicon ‘Heinz 2 cm fruit, S. lycopersicon ‘Heinz 3 cm fruit, and S lycopersicon ‘Heinz mature green fruit, S. pimpinellifolium immature green fruit, S. pimpinellifolium breaker fruit, S. lycopersicon ‘Heinz breaker fruit, and S. lycopersicon ‘Heinz breaker+ 10 fruit, S. lycopersicon ‘Heinz unopened flower buds, and S. lycopersicon ‘Heinz fully opened flowers. The expression of SlLHT3, SlANT5, SlLHT5, SlVAAT7, and SlCAT2 was detected to be high only in S. lycopersicon ‘Heinz unopened flower buds and extremely low in other examined parts of S. pimpinellifolium and S. lycopersicon ‘Heinz tomato plants. In addition, six genes, including SlAAP8, SlLHT4, SlLHT12, SlLHT13, SlAAP5, and SlAAP3 showed high expression levels in S. lycopersicon ‘Heinz unopened flower buds and fully opened flowers compared to other organs of both S. pimpinellifolium and S. lycopersicon ‘Heinz tomato plants.

Figure 6.

Expression patterns of genes in various tissues of Solanum lycopersicon ‘Heinz and their orthologues/paralogs in the wild relative S. pimpinellifolium, which were retrieved by the Locus identity number of SlAATs included in Table 1. The data for RNA sequencing were obtained from a public database (the Tomato Functional Genomics Database), and were analyzed and generated using ComplexHeatmap version 2.2.0 package in R.

The expression of SlLHT9, SlCAT9, SlCAT10, and SlATL5 was considerably high in both S. lycopersicon ‘Heinz unopened flower buds and S. pimpinellifolium leaves but was low in other examined organs. The expression of SlTTP1, SlLAX5, SlVAAT10, SlCAT3, and SlVAAT2 appeared to be upregulated only in the leaves. Interestingly, SlVAAT9, SlLHT8, SlGAT3, SlCAT6, and SlCAT5 were observed to be highly expressed only in the roots, while the expression in other organs was downregulated. The expression of genes of the AAP family: SlAAP2, SlAAP3, SlAAP4, SlAAP5, SlAAP6, SlAAP7, and SlAAP8 was observed to be high in some organs such as S. lycopersicon ‘Heinz unopened flower buds and S. lycopersicon ‘Heinz fully opened flowers, but low in the other examined organs. Six out of 13 genes of the LHT subfamily (SlLHT1, SlLHT2, SlLHT6, SlLHT7, SlLHT8, and SlLHT10) showed high expression in the roots. The high expression of ProT genes was observed in different organs; for example, SlProT1 and SlProT2 were highly expressed in the flowers and in buds respectively, while SlProT3 and SlProT4 were highly expressed in both S. lycopersicon ‘Heinz leaves and roots. The genes of LAX subfamily were highly expressed in the roots except SlLAX3, which showed a high expression in the fruits (S. lycopersicon ‘Heinz breaker fruits, S. pimpinellifolium breaker fruits, S. pimpinellifolium immature green fruits, S. lycopersicon ‘Heinz mature green fruits, and S. lycopersicon ‘Heinz 3 cm fruits). The expression of SlBAT2 and SlBAT3 was the same in all the examined organs. Two genes of the TTP subfamily (SlTTP1 and SlTTP4) exhibited a similar expression pattern: high in the leaves and low in other organs.

2.4. Syntenic Analysis

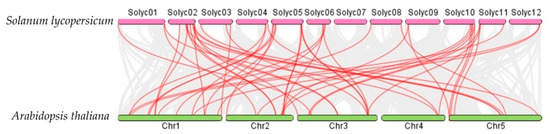

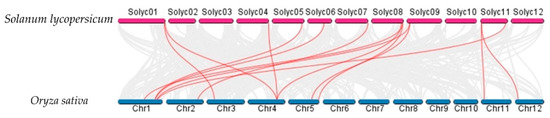

Syntenic analysis performed among the AATs in S. lycopersicum, Arabidopsis thaliana, and O. sativa demonstrated that the S. lycopersicum AATs are orthologs of a number of O. sativa and Arabidopsis thaliana AAT genes (Figure 7 and Figure 8). For example, SlLAT5 and SlLAT6 genes are orthologs of OsLAT7 (LOC_Os01g61044.1), and StLAX2 is an ortholog of OsAUX3 (LOC_Os03g14080), whereas StLAX4 is an ortholog of OsAUX1 (LOC_Os01g63770). Syntenic AAT gene pairs between S. lycopersicum and Arabidopsis thaliana, and between S. lycopersicum and O. sativa are presented in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2.

Figure 7.

Syntenic analysis between AAt regions of Solanum lycopersicum and Arabidopsis thaliana. Gray lines in the background indicate collinear blocks between Solanum lycopersicum and Arabidopsis thaliana, while red lines highlight syntenic AAT gene pairs.

Figure 8.

Syntenic analysis between AAt regions of Solanum lycopersicum and Oryza sativa. Gray lines in the background indicate collinear blocks between Solanum lycopersicum and Oryza sativa, while red lines highlight syntenic AAT gene pairs.

3. Discussion

AATS have been identified in several plant species such as Arabidopsis thaliana, O. sativa, and S. tuberosum. However, ATTs in S. lycopersicum have not been identified so far. In this study, 88 AATs were identified in S. lycopersicum and divided into two superfamilies based on their similarity with previously identified AATs in Arabidopsis thaliana, O. sativa, and S. tuberosum plants [1,5]. Interestingly, the number of members in the AAP subfamily are the same (8 members) as that in Arabidopsis, S. tuberosum, and S. lycopersicum but in O. sativa, this number is more than double (19 members). This expansion in the members of AAP subfamily in O. sativa may be due to segmental and tandem duplication events [1]. However, the number of members in the same subfamily varies between species. For example, there are six members in the LHT subfamily in O. sativa, ten in Arabidopsis, 11 in S. tuberosum, and 13 in S. lycopersicum. In fact, the largest subfamily in S. lycopersicum is LHT and the smallest subfamilies are ACT and GAT with only three members each (Table 1). Our results of the phylogenetic analysis were in agreement with those of O. sativa, Arabidopsis, and S. tuberosum. The SlAATs were divided into two main clades: AAAP and APC superfamilies (Figure 3). Similar to Arabidopsis thaliana, O. sativa, and S. tuberosum, the chromosomal mapping of S. lycopersicum AAT genes showed that they are distributed throughout the 12 chromosomes, and most SlAAT genes were localized on chromosome 2 and the least were found on chromosome 7 (Figure 2). In the current study, we found that segmental gene duplication within the tomato genome mainly contributed to the expansion of SlAAT superfamily in S. lycopersicum, and no tandem duplication was found on the gene pairs. This is not the case for O. sativa, since segmental and tandem duplication contributes equally to the expansion of the AAT superfamily [1] and in S. tuberosum, only tandem duplication contributes greatly to the expansion of the AAT superfamily [5]. Examination of the expression patterns of the segmental duplicated genes of SlAAT superfamily within tomato genome, showed that each gene exhibits a distinct expression pattern. This may suggest that segmental duplication events in the SlAAT superfamily in S. lycopersicum do not have overlapping functions and therefore may contribute to the functional divergence of the duplicated genes.

The analysis of the expression patterns of SlAAT genes may provide useful information for determining their function. In the current study, expression analysis of SlAAT genes based on RNA-Seq data showed that a number of genes were expressed in specific tissues and developmental stages. As seen in Figure 6, the expression profiles of SlAAT genes that were highly expressed may be associated with specific organs, including leaves, root, and flowers, but not fruits.

The genes encoding SlLAX1, SlLAX2, SlLAX4, and SlLAX5 are specifically expressed in roots. Syntenic analysis revealed that StLAX1 is an ortholog of OsAUX1 and OsAUX2, which both showed high expression in the roots. In addition, StLAX1 is an ortholog of AtAUX1 (AT2G38120), which is known to be primarily expressed in the roots [37]. Further, the expression of SlLHT2, SlCAT5, and SlProT4 were observed to be high in the roots. Syntenic analysis showed that SlLHT2, SlAAP2, and SlProT2 are orthologs of AtLHT1, AtAAP5, and AtProT2, respectively, which are reported to play a role in amino acid uptake by the roots [20,38,39].

In addition, SlCAT6 expression was high in both S. lycopersicon ‘Heinz roots and S. lycopersicon ‘Heinz fully opened flowers. AtCAT6, was revealed to be involved in amino acid uptake into the sink cells of flowers and root primordia [40]. The expression of SlAAP8, the ortholog of AtAAP6, was high in S. lycopersicon ‘Heinz unopened flower buds and S. lycopersicon ‘Heinz fully opened flowers. However, AtAAP6 expression is mainly present in the xylem parenchyma cells [41].

The expression patterns of SlAAT genes elucidated in the current study provide foundation for further investigation of the AATs to completely understand their importance and roles in plant physiology and their contribution to plant productivity. Moreover, as AATs are usually induced by abiotic stresses such as salinity and drought [21], it is important to perform further studies on their interaction with the environment to evaluate the plant performance under stress conditions.

4. Materials and Methods

4.1. Identification of AAT Genes in S. lycopersicum

To identify the AATs in S. lycopersicum, those in Arabidopsis, O. sativa, and S. tuberosum [1,5] were used as queries in Basic Local Alignment Search Tool (BLAST) in the SOL Genomics Network (SGN; http://solgenomics.net/ (accessed on 31 January 2021)) against the S. lycopersicum genome and protein sequence database (version SL4.0) with default settings. The databases were also queried for homologs using ‘amino acid transporter’ and ‘amino acid permease’ as keywords. The redundant sequences were removed, and the remaining protein sequences were submitted to InterProScan (https://www.ebi.ac.uk/interpro/search/sequence/ (accessed on 31 January 2021)) to scan for AAT domains. Information about gene structure (length, number of introns, length of the open reading frame (ORF), locus accession, amino acid length, and genomic location were all acquired from SGN. Molecular weight (MW) and the theoretical isoelectric point (pI) were predicted using the Compute/Mw tool (http://web.expasy.org/ (accessed on 31 January 2021)). The gene structure of SlAATs were also analyzed using Gene Structure Display Server (GSDS) (http://gsds.gao-lab.org/index.php (accessed on 31 January 2021)) [42]. The TMHMM Server version 2.0 (http://www.cbs.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM/ (accessed on 31 January 2021)) was used to predict the putative transmembrane regions in each SlAAT protein [43]. In order to display the gene structure of the exons and introns of SlAATs, the genomic and cDNA sequences of each SlAAT identified in this study were retrieved from the SGN and used as queries in the GSDS (http://gsds.cbi.pku.edu.cn/ (accessed on 31 January 2021)).The nomenclature of S. lycopersicum AATs was assigned according to chromosome order and considering their phylogenetic relationship. However, SlLax1, SlLax2, SlLax3, SlLax4, and SlLax5 have been previously named [44].

4.2. Chromosomal Mapping of SlAAT Genes and Gene Duplication

The approximate locations of SlAAT genes were identified using the available information at SGN, and mapped onto the 12 corresponding S. lycopersicum chromosomes using MapChart software [45].

The Plant Genome Duplication Database (PGDD) (http://chibba.agtec.uga.edu/duplication (accessed on 31 January 2021)) was used to download the gene pairs of the S. lycopersicum genome and the related information about synonymous substitution rate (Ks) and nonsynonymous substitution rate (Ka) was also obtained. Genes distributed nearby and separated by five or fewer genes was selected as the criterion for considering tandem duplicates. Divergence time (Mya, million years ag) of the gene pairs was estimated using the following equation: T = Ks/2x (x = 6.56 × 10−9), in which x is the mean synonymous substitution rate for tomato [46].

The sequence similarity between the proteins of duplicated genes was calculated using the sequence manipulation suite programs (https://www.bioinformatics.org/sms2/ident_sim.html (accessed on 31 January 2021)).

4.3. Syntenic Analysis

A multiple collinear scanning toolkit (MCScanX) [47] was used to perform an examination of syntenic regions between the AATs of S. lycopersicum, Arabidopsis thaliana, and O. sativa and the result was plotted using Dual Synteny Plotter software [48].

4.4. Phylogenetic Analysis and Sequence Alignment

In order to construct the phylogenetic tree, the multiple sequence alignment AAT proteins of S. lycopersicum, O. sativa, and Arabidopsis thaliana was performed using MEGA 6.0 software, with the default settings of MUltiple Sequence Comparison by Log-Expectation (MUSCLE) alignment [49]. The phylogenetic tree was constructed using the maximum likelihood method with the following settings: test of phylogeny: bootstrap method; substitution type: amino acid, rates among sites, uniform rates; missing data treatments: use all sites; ML heuristic method: nearest-neighbor-interchange (NNI); initial tree for ML: make initial automatically tree; branch swap filter: none; number of threads: 3. For maximum likelihood analysis, the best model of protein evolution was determined in MEGA6 using the ‘find best DNA/protein models’ tool. The best model was the ‘Whelan and Goldman’ (WAG) model [35]. The robustness of the analyses was examined using 500 bootstrap replicates [50]. To analyze the transmembrane region conservation, the amino acid sequences of SlAATs were aligned using MUSCLE with default settings in Jalview version 2 [51].

The motifs of SlAAT proteins were identified using the MEME tool (http://meme-suite.org/tools/meme (accessed on 31 January 2021)) with default settings, except that the maximum number of motifs was defined as 20.

4.5. Expression Analysis of SlAAT Genes Based on RNA-Seq Data

Expression profiles of the SlAAT genes were obtained from RNA sequencing (RNA-Seq) data from the Tomato Functional Genomics Database (http://ted.bti.cornell.edu/ (accessed on 31 January 2021)) using the transcriptomic analysis of various tissues in the S. lycopersicon ‘Heinz and the wild relative S. pimpinellifolium. The search was performed using the locus name as a query. The heatmap was generated using ComplexHeatmap version 2.2.0 package in R [52].

5. Conclusions

In this study, the AAT gene superfamily in S. lycopersicum was identified and analyzed using a broad range of bioinformatic tools. The SGN was first used to retrieve the nucleotide and amino acid sequences of the SlAATs to obtain general information and sequence characterization of SlAATs. Chromosomal localization and gene duplication events in SlAATs were demonstrated. In addition, the phylogenetic relationships and protein motifs of SlAAts were determined. The expression profiles of SlAAT genes in various tissues of S. lycopersicum were elucidated using RNA-Seq data in the Tomato Functional Genomics Database. This study will facilitate further investigation of the SlAAT gene superfamily and the functional characterization of the members of SlAATs. Further analysis of expression profiles under abiotic stress conditions will reveal their potential roles in response to environmental stress.

Supplementary Materials

The following are available online at https://www.mdpi.com/2223-7747/10/2/289/s1, Table S1: Syntenic AAT gene pairs between Solanum lycopersicum and Arabidopsis thaliana. Table S2: Syntenic AAT gene pairs between Solanum lycopersicum and Oryza sativa.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Not applicable.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Zhao, H.; Ma, H.; Yu, L.; Wang, X.; Zhao, J. Genome-wide survey and expression analysis of amino acid transporter gene family in rice (Oryza sativa L.). PLoS ONE 2012, 7, e49210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wipf, D.; Loque, D.; Lalonde, S.; Frommer, W.B. Amino Acid transporter inventory of the selaginella genome. Front. Plant Sci. 2012, 3, 36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M.; Wu, S.; Chen, Z.; Dong, Q.; Yan, H.; Xiang, Y. Genome-wide survey and expression analysis of the amino acid transporter gene family in poplar. Tree Genet. Genomes 2015, 11, 83. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, L.; Yuan, H.; Ren, R.; Zhao, S.; Han, Y.; Zhou, Q.; Ke, D.; Wang, Y.; Wang, L. Genome-wide identification, classification, and expression analysis of amino acid transporter gene family in Glycine Max. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ma, H.; Cao, X.; Shi, S.; Li, S.; Gao, J.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, Q.; Chen, Q. Genome-wide survey and expression analysis of the amino acid transporter superfamily in potato (Solanum tuberosum L.). Plant Physiol. Biochem. 2016, 107, 164–177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ortiz-Lopez, A.; Chang, H.; Bush, D.R. Amino acid transporters in plants. Biochim. Biophys. Acta Biomembr. 2000, 1465, 275–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rentsch, D.; Boorer, K.J.; Frommer, W.B. Structure and function of plasma membrane amino acid, oligopeptide and sucrose transporters from higher plants. J. Membr. Biol. 1998, 162, 177–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Okumoto, S.; Pilot, G. Amino acid export in plants: A missing link in nitrogen cycling. Mol. Plant 2011, 4, 453–463. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegeder, M. Transporters for amino acids in plant cells: Some functions and many unknowns. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 2012, 15, 315–321. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Denancé, N.; Ranocha, P.; Martinez, Y.; Sundberg, B.; Goffner, D. Light-regulated compensation of wat1 (walls are thin1) growth and secondary cell wall phenotypes is auxin-independent. Plant Signal. Behave. 2010, 5, 1302–1304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tegeder, M.; Rentsch, D. Uptake and partitioning of amino acids and peptides. Mol. Plant 2010, 3, 997–1011. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kwart, M.; Hirner, B.; Hummel, S.; Frommer, W.B. Differential expression of two related amino acid transporters with differing substrate specificity in Arabidopsis thaliana. Plant J. 1993, 4, 993–1002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fischer, W.; Kwart, M.; Hummel, S.; Frommer, W.B. Substrate specificity and expression profile of amino acid transporters (AAPs) in Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 1995, 270, 16315–16320. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Okumoto, S.; Schmidt, R.; Tegeder, M.; Fischer, W.N.; Rentsch, D.; Frommer, W.B.; Koch, W. High affinity amino acid transporters specifically expressed in xylem parenchyma and developing seeds of Arabidopsis. J. Biol. Chem. 2002, 277, 45338–45346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Koch, W.; Kwart, M.; Laubner, M.; Heineke, D.; Stransky, H.; Frommer, W.B.; Tegeder, M. Reduced amino acid content in transgenic potato tubers due to antisense inhibition of the leaf H/amino acid symporter StAAP1. Plant J. 2003, 33, 211–220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miranda, M.; Borisjuk, L.; Tewes, A.; Heim, U.; Sauer, N.; Wobus, U.; Weber, H. Amino acid permeases in developing seeds of Vicia faba L.: Expression precedes storage protein synthesis and is regulated by amino acid supply. Plant J. 2001, 28, 61–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hirner, A.; Ladwig, F.; Stransky, H.; Okumoto, S.; Keinath, M.; Harms, A.; Frommer, W.B.; Koch, W. Arabidopsis LHT1 is a high-affinity transporter for cellular amino acid uptake in both root epidermis and leaf mesophyll. Plant Cell 2006, 18, 1931–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Foster, J.; Lee, Y.; Tegeder, M. Distinct expression of members of the LHT amino acid transporter family in flowers indicates specific roles in plant reproduction. Sex. Plant Reprod. 2008, 21, 143–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svennerstam, H.; Ganeteg, U.; Näsholm, T. Root uptake of cationic amino acids by Arabidopsis depends on functional expression of amino acid permease 5. New Phytol. 2008, 180, 620–630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Svennerstam, H.; Jämtgård, S.; Ahmad, I.; Huss-Danell, K.; Näsholm, T.; Ganeteg, U. Transporters in Arabidopsis roots mediating uptake of amino acids at naturally occurring concentrations. New Phytol. 2011, 191, 459–467. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rentsch, D.; Hirner, B.; Schmelzer, E.; Frommer, W.B. Salt stress-induced proline transporters and salt stress-repressed broad specificity amino acid permeases identified by suppression of a yeast amino acid permease-targeting mutant. Plant Cell 1996, 8, 1437–1446. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grallath, S.; Weimar, T.; Meyer, A.; Gumy, C.; Suter-Grotemeyer, M.; Neuhaus, J.; Rentsch, D. The AtProT family. Compatible solute transporters with similar substrate specificity but differential expression patterns. Plant Physiol. 2005, 137, 117–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Schwacke, R.; Grallath, S.; Breitkreuz, K.E.; Stransky, E.; Stransky, H.; Frommer, W.B.; Rentsch, D. LeProT1, a transporter for proline, glycine betaine, and γ-amino butyric acid in tomato pollen. Plant Cell 1999, 11, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ueda, A.; Shi, W.; Sanmiya, K.; Shono, M.; Takabe, T. Functional analysis of salt-inducible proline transporter of barley roots. Plant Cell Physiol. 2001, 42, 1282–1289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Meyer, A.; Eskandari, S.; Grallath, S.; Rentsch, D. AtGAT1, a high affinity transporter for γ-aminobutyric acid in Arabidopsis thaliana. J. Biol. Chem. 2006, 281, 7197–7204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Carrier, D.J.; Bakar, N.T.A.; Swarup, R.; Callaghan, R.; Napier, R.M.; Bennett, M.J.; Kerr, I.D. The binding of auxin to the Arabidopsis auxin influx transporter AUX1. Plant Physiol. 2008, 148, 529–535. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swarup, R.; Kramer, E.M.; Perry, P.; Knox, K.; Leyser, H.O.; Haseloff, J.; Beemster, G.T.; Bhalerao, R.; Bennett, M.J. Root gravitropism requires lateral root cap and epidermal cells for transport and response to a mobile auxin signal. Nat. Cell Biol. 2005, 7, 1057–1065. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kierzkowski, D.; Lenhard, M.; Smith, R.; Kuhlemeier, C. Interaction between meristem tissue layers controls phyllotaxis. Dev. Cell 2013, 26, 616–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Péret, B.; Swarup, K.; Ferguson, A.; Seth, M.; Yang, Y.; Dhondt, S.; James, N.; Casimiro, I.; Perry, P.; Syed, A. AUX/LAX genes encode a family of auxin influx transporters that perform distinct functions during Arabidopsis development. Plant Cell 2012, 24, 2874–2885. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, C.; Subudhi, P.K. Comprehensive analysis and expression profiling of the OsLAX and OsABCB auxin transporter gene families in rice (Oryza sativa) under phytohormone stimuli and abiotic stresses. Front. Plant Sci. 2016, 7, 593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Ortiz-Lopez, A.; Jung, A.; Bush, D.R. ANT1, an aromatic and neutral amino acid transporter in Arabidopsis. Plant Physiol. 2001, 125, 1813–1820. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Frommer, W.B.; Hummel, S.; Unseld, M.; Ninnemann, O. Seed and vascular expression of a high-affinity transporter for cationic amino acids in Arabidopsis. Proc. Nat. Acad. Sci. USA 1995, 92, 12036–12040. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Feng, L.; Yang, T.; Zhang, Z.; Li, F.; Chen, Q.; Sun, J.; Shi, C.; Deng, W.; Tao, M.; Tai, Y. Identification and characterization of cationic amino acid transporters (CATs) in tea plant (Camellia sinensis). Plant Growth Regul. 2018, 84, 57–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dündar, E.; Bush, D.R. BAT1, a bidirectional amino acid transporter in Arabidopsis. Planta 2009, 229, 1047–1056. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Whelan, S.; Goldman, N. A general empirical model of protein evolution derived from multiple protein families using a maximum-likelihood approach. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2001, 18, 691–699. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thompson, J.D.; Gibson, T.J.; Plewniak, F.; Jeanmougin, F.; Higgins, D.G. The CLUSTAL_X windows interface: Flexible strategies for multiple sequence alignment aided by quality analysis tools. Nucleic. Acids Res. 1997, 25, 4876–4882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Hammes, U.Z.; Taylor, C.G.; Schachtman, D.P.; Nielsen, E. High-affinity auxin transport by the AUX1 influx carrier protein. Curr. Biol. 2006, 16, 1123–1127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lehmann, S.; Gumy, C.; Blatter, E.; Boeffel, S.; Fricke, W.; Rentsch, D. In planta function of compatible solute transporters of the AtProT family. J. Exp. Bot. 2011, 62, 787–796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Ji, Y.; Bhuiyan, N.H.; Pilot, G.; Selvaraj, G.; Zou, J.; Wei, Y. Amino acid homeostasis modulates salicylic acid–associated redox status and defense responses in Arabidopsis. Plant Cell 2010, 22, 3845–3863. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hammes, U.Z.; Nielsen, E.; Honaas, L.A.; Taylor, C.G.; Schachtman, D.P. AtCAT6, a sink-tissue-localized transporter for essential amino acids in Arabidopsis. Plant J. 2006, 48, 414–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hunt, E.; Gattolin, S.; Newbury, H.J.; Bale, J.S.; Tseng, H.; Barrett, D.A.; Pritchard, J. A mutation in amino acid permease AAP6 reduces the amino acid content of the Arabidopsis sieve elements but leaves aphid herbivores unaffected. J. Exp. Bot. 2010, 61, 55–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, B.; Jin, J.; Guo, A.; Zhang, H.; Luo, J.; Gao, G. GSDS 2.0: An upgraded gene feature visualization server. Bioinformatics 2015, 31, 1296–1297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Krogh, A.; Larsson, B.; Von Heijne, G.; Sonnhammer, E.L. Predicting transmembrane protein topology with a hidden Markov model: Application to complete genomes. J. Mol. Biol. 2001, 305, 567–580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pattison, R.J.; Catalá, C. Evaluating auxin distribution in tomato (Solanum lycopersicum) through an analysis of the PIN and AUX/LAX gene families. Plant J. 2012, 70, 585–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Voorrips, R.E. MapChart: Software for the graphical presentation of linkage maps and QTLs. J. Hered. 2002, 93, 77–78. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Särkinen, T.; Bohs, L.; Olmstead, R.G.; Knapp, S. A phylogenetic framework for evolutionary study of the nightshades (Solanaceae): A dated 1000-tip tree. BMC Evol. Biol. 2013, 13, 214. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Tang, H.; Debarry, J.D.; Tan, X.; Li, J.; Wang, X.; Lee, T.-H.; Jin, H.; Marler, B.; Guo, H.; et al. MCScanX: A toolkit for detection and evolutionary analysis of gene synteny and collinearity. Nucleic Acids Res. 2012, 40, e49. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Xia, R.; Chen, H.; He, Y. TBtools, a Toolkit for Biologists integrating various biological data handling tools with a user-friendly interface. bioRxiv 2018, 289660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tamura, K.; Stecher, G.; Peterson, D.; Filipski, A.; Kumar, S. MEGA6: Molecular evolutionary genetics analysis version 6.0. Mol. Biol. Evol. 2013, 30, 2725–2729. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Felsenstein, J. Confidence limits on phylogenies: An approach using the bootstrap. Evolution 1985, 39, 783–791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Waterhouse, A.M.; Procter, J.B.; Martin, D.M.; Clamp, M.; Barton, G.J. Jalview Version 2—A multiple sequence alignment editor and analysis workbench. Bioinformatics 2009, 25, 1189–1191. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gu, Z.; Eils, R.; Schlesner, M. Complex heatmaps reveal patterns and correlations in multidimensional genomic data. Bioinformatics 2016, 32, 2847–2849. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2021 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).