Abstract

Real estate inventory dynamics exhibit distinct temporal patterns and spatial heterogeneity, and precise identification of these trends serves as a prerequisite for effective policy formulation. Research on the spatiotemporal evolution patterns and influencing factors of real estate inventory holds significant academic and practical value. By employing ESDA, the Boston Matrix, and geographically weighted regression models to analyze 2017–2022 data from 287 Chinese cities, this study reveals a cyclical shift in China’s real estate inventory management—from “destocking” to “restocking”. The underlying drivers have transitioned from policy-led interventions to fundamentals-driven factors, including population dynamics, income levels, and market expectations. China’s real estate inventory and its changes exhibit significant spatiotemporal differentiation and spatial agglomeration patterns, demonstrating a spatial structure characterized by “multiple clustered highlands with peripheral lowlands” led by urban agglomerations. The influencing mechanism of China’s real estate inventory constitutes a complex system shaped by three key dimensions: macro-level drivers, regional differentiation, and structural contradictions. Policymakers should reorient destocking policies from “short-term stimulus” to “long-term coordination”, from “industrial policy” to “spatial policy”, and from addressing market “symptoms” to tackling “root causes”. This study argues that effective destocking policies constitute a systematic engineering challenge, demanding policymakers demonstrate profound analytical depth. They must move beyond simplistic sales metrics and perform multi-dimensional evaluations encompassing economic geography, demographic trends, fiscal systems, and land supply mechanisms. This paradigm shift from “symptom management” to “root cause resolution” and “systemic regulation” is essential for achieving sustainable real estate market development.

1. Introduction

1.1. Research Background

Effective inventory management presents substantial opportunities for operational cost reduction and remains a cornerstone research domain in both supply chain and industrial chain management [1,2]. In the dynamic real estate market landscape, optimizing inventory allocation through a comprehensive system approach has emerged as a critical strategy for enterprises to enhance supply chain agility and industrial chain responsiveness—key factors in maintaining competitive resilience and achieving sustainable regional development [3,4]. After more than 20 years of rapid development, the Chinese real estate market has accumulated a considerable amount of inventory. The 2015 Central Economic Work Conference listed “inventory reduction” as one of the five vital tasks of supply-side structural reform, highlighting the significance of this issue. Real estate inventory is not a regional issue in China. The management of real estate inventory in countries worldwide, including Brazil, the United States, Vietnam, and Belgium, has already drawn the attention of scholars [5,6].

Against the backdrop of the COVID-19 pandemic and economic downturn, the inventory issue in the real estate market directly impacts the healthy operation of the national economy and the stability of the financial system [7,8]. Real estate inventory exhibits pronounced regional divergence and externalities, and macro analysis at national or provincial scales is no longer effective in addressing real estate inventory management issues [9,10]. Changes in real estate inventory exhibit distinct temporal dynamics and spatial differentiation patterns. Accurately grasping these trends is a prerequisite for formulating effective policies. Therefore, conducting a systematic analysis of changes in China’s urban real estate inventory at the city level from both temporal and spatial dimensions, combined with the application of spatial econometric models to empirically test the impact mechanisms of influencing factors, holds significant research value in providing scientific basis for real estate market regulation and risk prevention [11].

1.2. Literature Review

Research on real estate inventory management originated from vacancy analysis, with early studies emphasizing conceptual and model development, while recent work focuses on applied policy analysis. International scholars Emmi [12,13], Vandell [14], and Ferrari [15] proposed the Vacancy Chain Model and natural vacancy rates, while Miceli [16], Radzimski [17], Boessen [18], and Mcclure [19] examined the micro and macro impacts of vacancies. Research on real estate inventory has evolved from describing phenomena to analyzing underlying mechanisms. Early studies primarily focused on quantifying inventory levels and examining their correlation with economic cycles [20]. As demonstrated by Lazear through an information economics model, the housing market exhibits the counterintuitive phenomenon of “inventory rising when demand falls”. The analysis reveals that while sellers rationally reduce prices during declining demand, the magnitude of these reductions proves insufficient. Consequently, the probability of sales decreases while inventory accumulates [21]. As research deepens, scholars have increasingly focused on studying the factors influencing real estate inventory and have introduced or developed a number of econometric models. It contributes to both theoretical advancement in real estate economics and practical policymaking by establishing a scientific foundation for precise market regulation while offering robust decision-making support.

As for research content and focus, supply-side analyses have demonstrated that spatiotemporal variations in land supply policies exert critical influence on inventory levels. Shen et al., based on panel data from 35 Chinese cities, found that in cities with a price-to-income ratio below 7, land supply regulation plays a significantly positive role in inventory reduction, whereas high-price cities must rely on price-based regulation [22]. On the demand side, demographic transitions and evolving housing preferences offer new perspectives. Bogataj et al. discovered that 11 million vacant homes in Europe are directly linked to a mismatch with housing demand in an aging society, where actuarially underwritten reverse mortgages can optimize supply-demand equilibrium [23]. In addition, beyond supply and demand factors, Yoo et al. found in their study of Gyeonggi Province, South Korea, that green space characteristics exert differential effects on inventory reduction. They observed that increasing the area of public spaces within a development reduces the unsold unit ratio by 0.028, while the distance to external green spaces has no significant effect [24]. Petersen, through counterfactual analysis of three Californian cities, found a post-pandemic valuation premium of 14.8–22% for inventory properties relative to rental units, suggesting that economic uncertainty drives speculative inventory accumulation [25].

Analysis of research methodologies and models reveals that scholars have consistently prioritized inventory management model development and methodological innovation. In recent years, spatial econometrics and system dynamics have emerged as mainstream tools, with a pronounced trend toward methodological integration [26]. Geman et al. first applied the inventory theory to UK commercial real estate, finding that futures data explained 35% of the variance in inventory fluctuations [27]. Zhao et al. utilized a spatial Durbin model to quantify regional heterogeneity in housing price spillover effects across Chinese cities, revealing that conventional zoning approaches underestimate spatial interdependence by 15% [28]. Zhang et al. integrated geographic information systems with super-efficiency DEA to achieve a synergistic evaluation of risk zoning and management performance, revealing that low-efficiency zones account for 60% of cities in the Yangtze River Delta [29]; Wen et al. demonstrated through a Markov decision model that when price appreciation surpasses a critical threshold, implementing a “reservation-level pricing strategy” boosts corporate profitability by 12% [30]. Kwoun et al. applied a system dynamics model to simulate real estate inventory cycles and housing investment patterns dynamically [31].

Regarding research scale and geographic scope, existing literature predominantly examines macro-level analyses at national and provincial scales, while meso-scale case studies of specific regional markets have increasingly gained scholarly attention. Cao et al. conducted a probabilistic dynamic material flow analysis of urban housing stock in China, projecting the evolution trajectory of future housing stock at the national level, providing crucial insights for understanding overall trends [32]. Zhang et al. conducted a detailed analysis of the dynamics, risks, and management performance of urban real estate inventory in the Yangtze River Delta region, revealing its “core-periphery” spatial pattern and diverse evolution pathways [21]. Similarly, Zhao et al. analyzed the changing characteristics and multi-level influencing factors of real estate inventory using 35 key cities in China as samples [14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33].

1.3. Research Gap and Goals

The current research on the influencing factors of real estate inventory has developed into a multi-dimensional, multi-method framework, and has made remarkable progress in theoretical system, method innovation and empirical accumulation. First, the theoretical framework has become increasingly refined, with research content undergoing a profound shift from descriptive analysis to mechanism-based examination, thereby establishing a relatively comprehensive analytical framework. Second, as methodological systems continue to innovate, research has evolved from single methodologies to mixed methods, with method integration emerging as a prominent trend. This shift has significantly enhanced the scientific rigor and explanatory power of analytical outcomes. However, there is still significant room for improvement in research on real estate inventory management.

Firstly, the research scale is too large and does not match the practical needs of precise policy design and implementation. Most scholars conduct empirical research at the national or provincial level, with focus on revealing overarching patterns and common characteristics at the national or large-regional level. The studies at such levels facilitate understanding macro trends or overall patterns, but treating cities at different levels of development as “averaged” obscures significant internal disparities. Regional divergence in the real estate market is becoming increasingly pronounced. The macro-level “folding effect” obscures regional heterogeneity, leading to analytical results that often prove inaccurate or insufficiently precise when guiding the design of real estate market regulation policies.

Secondly, the limited sample size restricts the generalizability of conclusions due to the “amplification effect” inherent in case studies, thereby hindering the discovery of patterns in real estate inventory or the advancement of management theory innovation. Case studies on specific regions, urban agglomerations and cities constitute the main body of the literature available. Such research enables in-depth analysis of real estate inventory issues within particular geographical contexts, yielding policy recommendations that are more locally targeted. However, the conclusions of case studies are often constrained by local characteristics and difficult to generalize to other regions. Large-scale comparative studies covering most cities nationwide under a unified research framework remain scarce, preventing policymakers from developing systematic insights into underlying patterns.

Identifying the scale, spatial distribution, spatiotemporal evolution patterns, and underlying drivers of real estate inventory is the cornerstone for scientifically designing policies to reduce inventory. This study aims to examine the following questions or hypotheses. First, what are the spatiotemporal patterns of real estate inventory in Chinese cities? Second, what are the nature and intensity of different factors influencing real estate inventory in Chinese cities, and how do their spatial mechanisms vary? Therefore, this study, based on 287 prefecture-level cities in China, conducts an in-depth analysis of the spatial pattern and changing pattern of real estate inventory in Chinese cities through ESDA, Boston matrix, and geographically weighted regression models. It reveals the mechanisms of factors influencing real estate inventory, providing a basis for central and local governments to design policies aimed at reducing real estate inventory.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

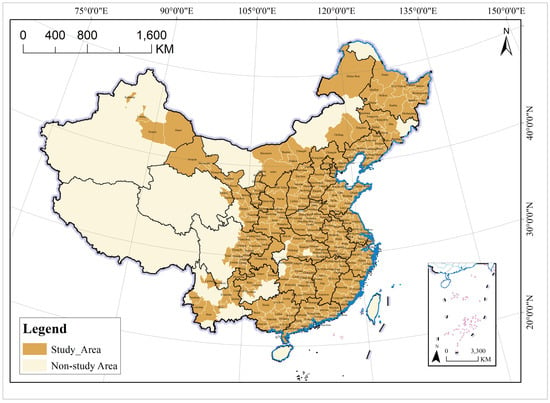

This study systematically analyzes the spatiotemporal dynamics and driving mechanisms of urban real estate inventory across 287 prefecture-level cities and municipalities directly under the central government in China (excluding autonomous prefectures and counties directly under provincial administration). Prefecture-level cities, as fundamental units of regional economic development in China, possess comprehensive administrative authority and stable statistical systems, allowing for effective cross-city comparisons of real estate inventory. The Notice on Effectively Managing the Supply of Residential Land for 2024, issued by the Ministry of Natural Resources in 2024, specifies that cities are the regulatory units and requires the adjustment of residential land supply based on the inventory reduction period of commercial housing (such as suspending land supply for more than 36 months). This policy framework directly applies to inventory management at the prefecture-level cities. Autonomous prefectures and counties directly under provincial jurisdiction were excluded primarily due to differences in their economic structures, policy applicability, and data integrity. Autonomous prefectures usually focus on the development policies of ethnic areas. Their land supply and housing construction planning are different from those of ordinary prefecture-level cities. For instance, the allocation threshold for affordable housing may be higher, resulting in an incomparable inventory formation mechanism. By contrast, provincial-administered counties typically exhibit smaller economic scales, rendering their real estate inventory data incompatible for meaningful comparison with prefecture-level cities due to fundamental disparities in data granularity. China currently has a total of 297 prefecture-level cities, and this study covers 96.63% of them, demonstrating extremely high representativeness. Prefecture-level cities in Hainan Province (including Haikou, Sanya, Sansha, and Danzhou) and the Tibet Autonomous Region (including Lhasa, Shigatse, Chamdo, Nyingchi, Shannan, and Nagqu) were excluded from the study area due to incomplete data (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

Study Area.

2.2. Research Steps and Methods

2.2.1. Technical Roadmap and Research Steps

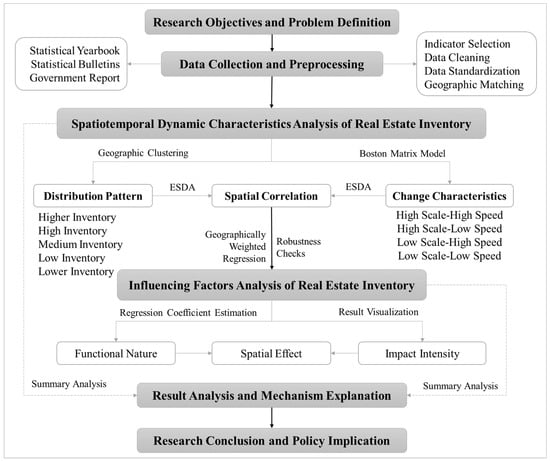

This study follows the logical framework of “data—analysis—conclusions—implications”, structured into some interconnected and progressive research stages, including Research Objectives and Problem Definition, Data Collection and Preprocessing, Spatiotemporal Dynamic Characteristics Analysis, Influencing Factors Analysis and Mechanism Explanation, Research Conclusion and Policy Implication, forming a complete closed-loop technical approach (Figure 2). The framework emphasizes the integration of “spatial thinking” and “dynamic perspective”, highlighting methodological complementarity and policy orientation. The analytical steps of this study primarily include: firstly, collecting urban real estate inventory data and its influencing factor data, and standardizing and preprocessing the data; secondly, analyze the geographical distribution characteristics and spatial effects of real estate inventory in Chinese cities using the ESDA method; thirdly, analyzing the dynamic characteristics and spatial effects of real estate inventory in Chinese cities based on the Boston Matrix model; fourthly, analyzing the impact mechanism and spatial effects of different factors on urban real estate inventory in China relying on the Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR) model; finally, systematically discussing the analysis findings, summarizing patterns in real estate inventory, and proposing policy recommendations for managing real estate inventory in Chinese cities by referring to the international research.

Figure 2.

Technical Roadmap and Research Steps.

2.2.2. Exploratory Spatial Data Analysis

ESDA is an integrated suite of spatial analysis methods and techniques designed to reveal spatial distribution patterns in data, identify spatial clusters and anomalies, and explain the mechanisms of spatial interactions among geographic phenomena through descriptive statistics and visualization techniques [34]. In global spatial autocorrelation analysis, the Global Moran’s I is used to measure the overall degree of clustering of similar attribute values across the entire study area (Moran’s > 0 indicates positive correlation, <0 indicates negative correlation). If the global analysis indicates the presence of spatial autocorrelation, further analysis (the significance level is 0.1) using local spatial autocorrelation methods (including Local Moran’s I and LISA cluster mapping) is required to identify local hotspots (high-high clusters), coldspots (low-low clusters), and spatial anomalies (high-low or low-high outliers). This approach reveals the specific distribution of spatial heterogeneity. It is calculated by the following equation [35]:

where represents the number of cities in the study area (i.e., 287); and are the real estate inventory values of the th and th cities; is the average value of urban real estate inventory; in global spatial autocorrelation represents the spatial weight matrix (inverse distance), while in local spatial autocorrelation it denotes the row-standardized value of spatial weights; is the sum of the spatial weight matrix; and are the standardized values of real estate inventory for the th and th cities, respectively.

2.2.3. Boston Matrix Model

The Boston Matrix serves as a fundamental strategic management framework. It categorizes businesses or products into four categories based on relative market share and market growth rate to guide resource allocation and strategic decision-making [36,37]. In real estate inventory analysis, this method can be adjusted to use relative inventory share (the proportion of a city’s inventory within the overall market) and inventory change rate (growth rate) as core indicators, thereby accurately capturing the dynamic characteristics of inventory. The Boston Matrix provides an integrated framework for dynamic classification, risk identification, and strategy generation of real estate inventory through its coupled analysis of relative market share and rate of change. Particularly applicable to China’s highly segmented regional markets, it serves as an effective tool for precise inventory reduction management. Relative share delineates spatial competition by employing industry leaders as reference points, emphasizing regional competitive patterns over mere scale, thus aligning more closely with strategic decision-making requirements than absolute share does. Growth rate encapsulates trends or dynamic aspects. The incorporation of the time dimension seeks to overcome the constraints of static spatial analysis [38]. Using Equations (1) and (2), we calculated the relative share () and annual growth rate () of real estate inventory for each city. By setting their average values ( and ) as thresholds, we categorized 287 cities into four types: High Scale-High Speed, High Scale-Low Speed, Low Scale-High Speed, and Low Scale-Low Speed [39,40].

where represents the real estate inventory of the th city; represents the maximum real estate inventory among the 287 cities; and represent the real estate inventories of the th city in 2017 and 2022, respectively.

2.2.4. Geographically Weighted Regression

GWR is an advanced spatial analysis technique that explores the spatial non-stationarity of variable relationships by embedding the geographic location of data into regression equations [41]. The use of the GWR model for studying the determinants of real estate inventory is primarily based on its exceptional capability to address the following key issues. First, GWR precisely captures the “location-specific” influence mechanism, providing direct scientific support for targeted city-specific measures. Second, GWR effectively uncovers spatial interactions and spillover effects between regions, thereby enabling better understanding of transmission pathways of real estate inventory risks among different cities in surrounding regions. With representing the th independent variable (influencing factor), being the constant term, denoting the spatial location of the th city; reflecting the correlation between variables of the th city; as the error term of the regression equation, the GWR calculation formula is shown below [42,43]:

We adopt the Gaussian Model type and utilize Euclidean distance for Cartesian coordinates, with the adaptive bi-square serving as the geographic kernel to improve the model’s adaptability to local data distribution. The optimal bandwidth is determined through Golden section search, resulting in a best bandwidth size of 134.000, and the AICc is used as the Criterion for optimal bandwidth to balance model fit and complexity. Featuring 10 Number of varying coefficients and 0 Number of fixed coefficients, this configuration enables the model to flexibly capture spatial heterogeneity while avoiding overfitting, ensuring reliable analytical outcomes.

2.3. Indicator System and Data Sources

The dependent variable in this study is real estate inventory, measured by the area of unsold houses. Inventory is fundamentally the result of the dynamic equilibrium between supply and demand in the real estate market and is influenced by macroeconomic conditions. The independent variables include population density, per capita disposable income, average number of rooms in each household, residential land area, per capita housing construction area, GDP, GDP per capita, deposit loan ratio, and fiscal self-sufficiency rate (Table 1). The data for 287 cities form a balanced panel, exhibiting high completeness and reliability. The data primarily comes from sources such as the China Urban Statistical Yearbook and the China Urban Construction Statistical Yearbook for the period 2018–2023. Missing data were sourced from statistical bulletins, government work reports, third-party internet platforms, or telephone consultations with government departments. Some unavailable data were estimated using trend extrapolation interpolation, such as the 2018 Wenzhou data and the 2022 Fuzhou data. Data standardization was performed using the extremum method, based on calculation formulas (6) and (7).

Table 1.

Classification of Influencing Factors based on the average coefficient of geographically weighted regression.

According to statistical standards, real estate inventory does not include non-saleable properties such as resettlement housing and public facilities. Real estate inventory can be conceptually delineated into two operational definitions of narrow definition and broad definition. The former comprises completed housing units with pre-sale permits (i.e., immediately marketable housing stock awaiting final transactions), while the latter encompasses additional inventory components including ongoing construction projects and undeveloped land held by developers without active construction commencement [44]. In the context of Chinese policy, real estate inventory management primarily focuses on addressing high inventory issues within the narrow definition. Therefore, this study operationalizes the narrow definition of real estate inventory, employing unsold housing area as the primary measurement metric. This study adopts the narrow definition of real estate inventory for primary reasons as follows: First, in terms of data quality, the narrow inventory is the only officially published indicator by national and local statistical authorities, featuring unified statistical standards, standardized accounting methods, and complete time series. As the sole government-recognized standardized data, it ensures authenticity, comparability, and continuity, providing core support for the reliability of research conclusions and avoiding analytical distortions due to data bias. Second, from the perspective of real estate inventory management market conditions and policy orientation, the narrow inventory directly addresses the core challenge of China’s real estate inventory governance. It faces immediate sales pressure, making it an urgent priority that aligns with pressing practical demands. Inventories such as buildings under construction and undeveloped land within the broader definition still have a certain construction cycle and buffer space. They do not directly impact the market sales end at present and are not the priority focus of current policy measures. The inventory is measured in square meters to ensure fairness, comparability, and practicality in data statistics for the following reasons: First, given the diverse range of real estate product types, using square meters eliminates interference from product forms and unit specifications, enabling direct comparability between inventories of different types and sizes of real estate products. This approach avoids statistical biases caused by differences in measurement units. Second, the sales area is commonly used as the core statistical indicator in the real estate market, making the use of square meters more in line with market transactions and ensuring accurate calculation of the inventory reduction period of urban real estate.

The main reasons for selecting these influencing factors are as follows:

On the demand side, policy attention should prioritize the latent housing demand, improvement demand, and purchasing power of the population. Population density serves as a fundamental indicator of regional housing demand potential. First- and second-tier cities with high population density typically confront supply-demand imbalances, whereas third- and fourth-tier cities with population outflow tend to experience inventory accumulation pressures [45,46]. Per capita disposable income serves as a key indicator of residents’ purchasing power. Higher income levels translate to stronger effective demand for housing, whereas lower income levels may hinder inventory reduction [47,48]. The average number of rooms per household reveals housing improvement needs from a family structure perspective. Areas with fewer rooms may exhibit stronger upgrade demand, which helps reduce inventory [49,50].

Focusing on land supply and existing housing conditions from the supply side helps explain the formation mechanism of inventory from its source. Excessive land supply may lead to excessive development, resulting in supply-demand imbalance. Residential land supply is also closely tied to land-based fiscal revenue [51,52]. An excessively per capita housing construction area indicates market saturation, and further development will intensify inventory pressure [53].

The macroeconomic and policy environment are variables that must be controlled. GDP and per capita GDP represent the level of economic development. Economically developed regions usually have stronger population magnetism and housing affordability, while economically underdeveloped regions are prone to inventory accumulation [54]. The loan-to-deposit ratio and fiscal self-sufficiency rate serve as indicators of regional financial stability and fiscal sustainability. Specifically, a high loan-to-deposit ratio may constrain real estate credit support, while a low fiscal self-sufficiency rate may drive local governments to rely on land-related revenues, exacerbating supply excess [55,56].

3. Results

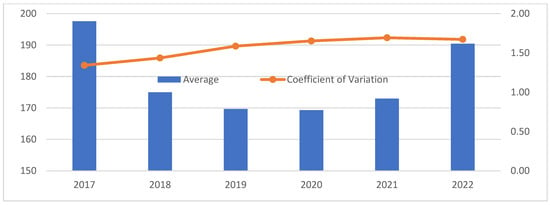

3.1. Distribution Pattern of Real Estate Inventory

The average change in real estate inventory levels from 2017 to 2022 shows a distinct U-shaped curve, profoundly reflecting the transformation of China’s real estate market from “policy-driven destocking” to “restocking under fundamental economic pressures”. The period from 2017 to 2020 witnessed a continuous decline in real estate inventory levels, primarily driven by proactive policy initiatives and a relatively stable market environment. The monetized relocation policy for shantytown renovation initiated by China at the end of 2015 has effectively driven the digestion of the existing real estate stock by directly creating housing purchase demand. After hitting bottom in 2020, amid recurring COVID-19 outbreaks and mounting economic pressures, household income expectations weakened, leading to a significant decline in both willingness and ability to purchase homes. This resulted in a rapid rebound in real estate inventory levels. Although early destocking policies proved highly effective, the pandemic revealed the fragility of underlying market demand. The current rebound in absolute inventory levels, coupled with a weakening ability to reduce stock, indicates that inventory risks in the real estate market remain severe. This necessitates more targeted and sustained policy measures to address. with the cyclical shift of China’s real estate market from “destocking” to “restocking”, its core driving logic has changed from policy stimulus led to fundamental (population, income, expectations) led. The coefficient of variation has continued to rise, increasing from 1.34 in 2017 to 1.67 in 2022—substantially higher than 0.36. It indicates that the dispersion of real estate inventory levels across Chinese cities is growing increasingly pronounced, meaning disparities between cities are rapidly widening and heterogeneity is significantly intensifying [57] (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Descriptive statistical analysis of the of urban real estate inventory in China.

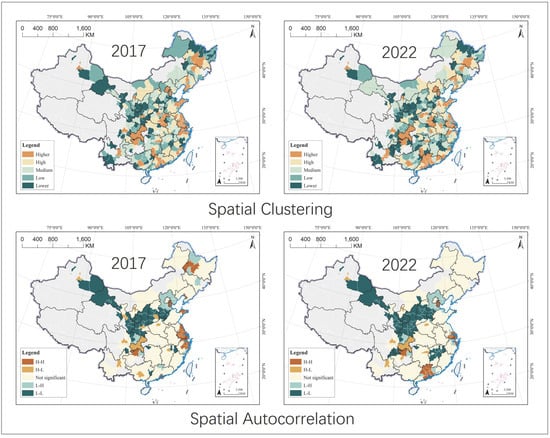

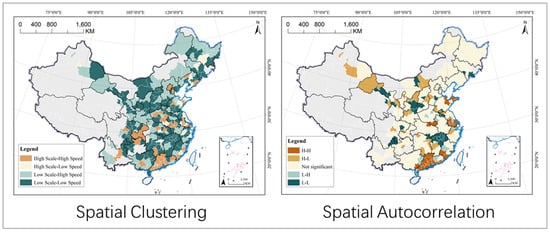

We classified the inventory scale of China’s real estate into five grades using quantile clustering method. In 2017, the inventory scale of the Higher-tier members exceeded 2.5 million square meters, decreasing to 2.4 million square meters by 2022. Notably, Beijing, Chongqing, and Shanghai consistently surpassed 20 million square meters, while Chengdu and Harbin long exceeded 10 million square meters. The inventory thresholds for real estate are defined as 2.5, 1.3, 0.8, and 0.5 million square meters for High, Medium, Low, and Lower categories, respectively. Although the specific values vary slightly across different years, the differences are consistently controlled within approximately 0.1 million square meters. Spatial clustering analysis using the quantile method reveals that high-inventory cities are predominantly concentrated in urban agglomeration regions, including the Yangtze River Delta (e.g., Wuxi, Nantong, JS-Suzhou, Hangzhou), Pearl River Delta (e.g., Guangzhou, Foshan), Chengdu-Chongqing, Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei, Harbin-Changchun (e.g., Harbin, Changchun, Suihua), Shandong Peninsula (e.g., Qingdao, Weifang), and Central Plains (e.g., Zhengzhou) urban agglomerations. Low-inventory cities are primarily clustered in the upper reaches of the Yellow River, the northwest, southwest, and northeast regions, as well as the peripheries of urban agglomerations in North China and the Yangtze River Basin. Representative cities include Lincang, Ziyang, Pingliang, Longnan, Karamay, Zhangjiajie, Hegang, HLJ-Yichun, Ya’an, Luohe, Xianyang, and Ezhou. In 2022, cities with high inventory further concentrated in the Pearl River Delta, while the Chengdu-Chongqing Urban Agglomeration, Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei region, and Shandong Peninsula Urban Agglomeration remained stable. The coverage of the Yangtze River Delta, Central Plains, and Harbin-Changchun urban agglomerations experienced a slight contraction. Meanwhile, the coverage of low-inventory cities expanded rapidly in the southwest and middle reaches of the Yangtze River, contracted significantly in the northeast and northwest regions, and remained relatively stable in the upper and middle reaches of the Yellow River Basin (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Geographical distribution and spatial effects of real estate inventory in China.

The robustness check of spatial autocorrelation is shown in Table 2, which compares the analysis results of different spatial weight parameters. Obviously, K-Nearest Neighbor is the best choice. The Moran’s I value for real estate inventory were 0.12 (Z = 5.00, p = 0.001) in 2017 and 0.08 (Z = 3.44, p = 0.006) in 2022, indicating that the inventory of real estate in Chinese cities is not randomly distributed, but exhibits significant spatial dependence. Cities with high inventory levels tend to cluster together, as do those with low inventory levels, forming “hotspots” and “coldspots”. In 2017, H-H and H-L cities were mainly concentrated in the Yangtze River Delta Urban Agglomeration, while hotspots in the Harbin-Changchun region (Northeast China) and the Chengdu-Chongqing Urban Agglomeration (Southwest China) had not yet taken shape (with their clustering processes only just initiated). By 2022, the coverage of hotspot cities within the Yangtze River Delta Urban Agglomeration contracted significantly. The nascent cluster in the Northeast region disappeared, while the emerging Chengdu-Chongqing Urban Agglomeration maintained its stability. The Pearl River Delta emerged as a new mature hotspot city cluster. In 2017 and 2022, most L-L and L-H cities were concentrated in the middle and upper reaches of the Yellow River Basin, extending into the northwest region (Figure 4).

Table 2.

Robustness check based on multiple spatial weights for autocorrelation.

3.2. Change Characteristics of Real Estate Inventory

The mean reflects the overall average level but is susceptible to interference from extreme values. The median is robust against extreme values but does not fully utilize the data information. For data without extreme values, the mean should be prioritized as the threshold; for skewed or outlier-containing data, the median should be prioritized. In this study, the relative share of real estate inventory was between 0 and 1, with a maximum and minimum growth rate of 41.62% and −46.59%, respectively. There were no extreme values, so the average value was used as the threshold. The average annual change rate of real estate inventory from 2017 to 2022 was −2.17%, and the average relative share of real estate inventory in 2022 was 0.07. Using them as thresholds, we categorized the evolution patterns of real estate inventory across 287 cities into four types based on the Boston Matrix. High-Scale-High-Speed cities account for 16.03% of the total, primarily concentrated in the Pearl River Delta and Chengdu-Chongqing urban agglomerations, with a small number distributed across the Central Plains, Yangtze River Delta, Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei, and Liaoning Central-Southern urban agglomerations. High Scale-Low Speed cities constitute the smallest proportion at 7.32% of the sample, including Shenyang, Dalian, Anshan, Changchun, Harbin, Nanjing, Wuxi, Nantong, Yancheng, Hangzhou, Ningbo, Taizhou (Zhejiang), Quanzhou, and Yantai. These cities demonstrate a highly dispersed spatial distribution pattern. Low Scale-High Speed cities account for approximately 30% of the sample population, predominantly concentrated in North China-Northeast China, the Loess Plateau, and China’s southwestern border areas. Low Scale-Low Speed cities constitute the largest proportion at 46.69% of the sample population, exhibiting extensive continuous clusters across four key regions: North China, Northwest China, the Yangtze River Basin, and the New Western Land-Sea Corridor (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Spatiotemporal evolution pattern of real estate inventory in China.

The Moran’s I value of 0.19 (Z = 7.12, p = 0.001) demonstrates statistically significant positive spatial autocorrelation in urban real estate inventory changes across Chinese cities. H-H cities exhibited a dominant cluster in the Yangtze River Delta Urban Agglomeration, accompanied by three secondary clusters in the Haixi Urban Agglomeration, the Yangtze River Delta Urban Agglomeration, and the Shandong Peninsula Urban Agglomeration. H-L cities show a predominantly riverine distribution pattern along the Yellow River Basin, with particular concentration in its middle and upper reaches, while extending into northwestern China. L-L cities have developed extensive agglomerations in the Yangtze River’s middle reaches, with smaller clusters also emerging in the Yellow River’s middle reaches. Overall, regional variations in real estate inventory changes exhibit distinct spatial clustering patterns, closely linked to economic development, population concentration, and growth expectations. Driven by policies such as the Guangdong-Hong Kong-Macao Greater Bay Area and national strategic hinterlands, urban agglomerations including the Pearl River Delta, Yangtze River Delta, Chengdu-Chongqing, Beijing-Tianjin-Hebei, and Shandong Peninsula have emerged as highly dynamic regions. Fueled by robust population inflows and industrial support, these areas exhibit elevated residential expectations for the real estate market, resulting in substantial real estate inventories characterized by both large scale and rapid growth. In addition, traditional economically strong cities such as Changchun, Harbin, Nanjing, Wuxi, Nantong, Yancheng, Hangzhou, and Ningbo have fallen into the dilemma of high inventory share and low inventory growth rate due to excessive land supply or industrial restructuring in the early stages, indicating that the cultivation and transformation of new models of real estate development face many challenges.

3.3. Influencing Factors of Real Estate Inventory

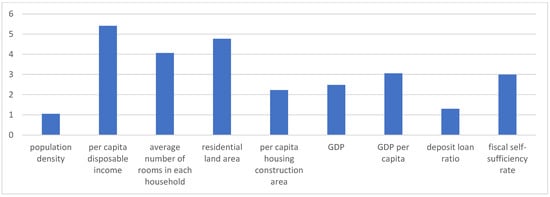

The R-squared value is 0.71, and the p-value is 0.000, indicating high goodness-of-fit and reliability of the OLS regression. The OLS regression results indicate that the Variance Inflation Factor values for all influencing factors are below 10, suggesting minimal impact of multicollinearity on the regression outcomes (Figure 6). The GWR model achieved an R2 of 0.84 (adjusted R2 = 0.80), indicating that approximately 84% of the spatial variation in real estate inventory can be explained by the model—demonstrating excellent explanatory power and model fit. The GWR model utilizes 47.81 effective parameters (trace(S)) for local estimation, achieving a substantial reduction in the residual sum of squares (RSS) to 4,684,837.64—demonstrating significantly improved alignment between model predictions and empirical observations. The GWR and OLS, SLM, SEMs yield AICc values of 3716.59 and 3787.78, 3785.08, 3780.23, respectively, with a difference of 70—well beyond the critical threshold of 3—demonstrating the GWR model’s substantive superiority. In summary, the analysis of influencing factors for urban real estate inventory using the GWR model consistently demonstrates its advantages in goodness-of-fit, flexibility in parameter estimation, and statistical diagnostic metrics, revealing the spatial heterogeneity of variable relationships more profoundly than the OLS model (Table 3).

Figure 6.

Variance Inflation Factor analysis of collinearity detection of influencing factors.

Table 3.

Robustness check based on comparison of different spatial econometric models.

Based on the absolute value of the Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR) parameter as the core criterion and the distribution differences of the absolute values across factors (whether they form distinct intensity breaks), we categorized influencing factors into three types: key factors, important factors, and auxiliary factors. GDP serves as the key factor, with its regression coefficient absolute value significantly higher than other factors (6.9 times that of the second-highest value). Its influence on inventory exhibits a “discontinuous leading effect”, making it the core variable affecting inventory levels. Important factors include GDP per capital, per capital disposable income, and residential land area, with the absolute regression coefficient ranking 2–4. Their influence is significantly stronger than that of auxiliary factors, exerting a pronounced driving or suppressing effect on inventory changes. Other influencing factors serve as auxiliary factors with weak effects. Their impact on inventory must be considered in combination with other factors, making it difficult to dominate inventory changes alone. An analysis of the range between minimum, median, and maximum regression coefficients reveals that GDP stands as the sole consistently positive driver across all cities. Other factors exhibit significant spatial heterogeneity, simultaneously demonstrating both positive driving and negative inhibiting effects (Table 4).

Table 4.

Classification of Influencing Factors based on the average coefficient of geographically weighted regression.

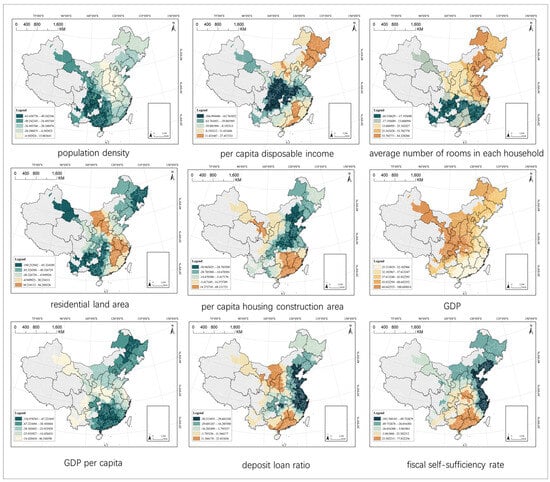

Overall, the impact of different factors on real estate inventory exhibits significant spatial heterogeneity and clustering, forming a distinct core-periphery spatial structure. The eastern core region shows concentrated and intense effects, while the central and western peripheral regions exhibit dispersed and weak effects. The core urban agglomerations along the eastern coast constitute a high-impact zone for most factors (including population density, per capita disposable income, and GDP per capita), demonstrating the high agglomeration of “economy population resources” in the region. This high concentration creates more direct and intensified effects on real estate inventory. In contrast, regions in central and western China experience a general weakening of the influence of various factors due to issues such as “economic underdevelopment, population outflow, and resource misallocation”. Furthermore, the direction of influence for some factors diverges (e.g., the north–south disparity in average number of rooms in each household).

The population density has a significant inhibitory effect on core regions, primarily concentrating along the Southwest Land-Sea New Channel and the Northwest Hexi Corridor, while its influence on peripheral regions diminishes. Per capita disposable income plays a prominent driving role in South China and Northeast China, while exerting a significant restraining effect in Central and Western China. The inhibitory effect is centered on the Loess Plateau and radiates to the periphery along the Yellow River Basin, Yangtze River Basin, Hexi Corridor, and Western Land Sea New Corridor. The positive high-impact areas of the average number of rooms in each household are primarily distributed in North China, Northeast China, and other regions, whereas the negative high-impact areas are mainly concentrated in southern regions such as the Strait Urban Agglomeration, the Yangtze River Mid-Reaches Urban Agglomeration, and the Chengdu-Chongqing Urban Agglomeration. This north–south disparity stems from spatial differentiation in regional living habits and household structures. Northern households exhibit higher room counts per dwelling on average, creating a positive push effect on real estate inventory that promotes accumulation. In contrast, southern regions—particularly the southeastern coastal areas—generally feature lower room counts per household with unsaturated housing demand. Certain cities in these regions even show a marginally negative effect (accelerating inventory reduction) due to “pronounced demand for compact housing units”. The high positive impact zone of residential land area exhibits concentrated distribution in eastern China and some central regions. The Yangtze River Delta cities’ rational land supply cadence effectively prevents inventory accumulation, thereby exerting significant negative suppression on real estate inventory levels. However, in both northeastern and western regions, the imbalanced quantity and suboptimal quality of residential land supply led to differentiated impacts on real estate inventory, exhibiting either “positive accumulation” or “marginal negative regulation” characteristics (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

Spatial effect of the influencing factor based on geographically weighted regression.

Per capita housing construction area demonstrates saturated suppression effects in eastern regions, while exhibiting regionally differentiated improvement patterns in western and southern areas. In urban areas where per capita housing construction area has achieved elevated levels, housing market saturation becomes pronounced, exerting significant downward pressure on new inventory accumulation. In western and southern regions, the “demand for improved housing” moderates this factor’s inhibitory effect on inventory levels. In certain urban areas, additional supply from shantytown redevelopment, urban renewal initiatives, and new town construction projects has actually contributed to inventory expansion. GDP demonstrates a significant positive driving effect in the eastern region, while showing weak correlation characteristics in the central and western regions. A high per capita GDP indicates greater wealth accumulation among residents, stronger housing consumption capacity and willingness, and exerts a stronger negative restraint on housing inventory. Consequently, its negative impact is more pronounced in South China and Northeast China, while its effect weakens in the central and western regions. The high-impact zones for the deposit-loan ratio are located in the eastern regions and some credit-active areas in central China (such as Wuhan and Chengdu-Chongqing region). In regions with high deposit-loan ratios, active credit markets accelerate inventory reduction by supporting first-time homebuyers and those upgrading their homes, exerting a negative suppressing effect on inventory. In conservative credit markets of central and western China, the impact of loan-to-deposit ratios on inventory is significantly weakened. In regions with high fiscal self-sufficiency, governments possess stronger resource allocation capabilities. They can optimize inventory through precise land supply adjustments and the introduction of affordable housing, exerting a negative suppressing effect on real estate inventory. Conversely, in central and western regions with high fiscal dependency, regulatory tools and resources are limited. This factor exerts a weaker influence on inventory, and may even yield a weak positive effect (promoting inventory accumulation) due to the “land finance dependency—blind residential land supply” dynamic. Notably, the positive correlation between fiscal self-sufficiency rates and inventory levels in the Pearl River Delta and surrounding areas may stem from non-core cities where the “excessive supply driven by reliance on land finance” has dominated the regional average. This phenomenon obscures the positive cases of core cities exhibiting “high fiscal self-sufficiency coupled with low inventory levels”. The anomalies observed in localized areas due to various factors precisely reveal the complexity of real estate inventory management.

4. Discussion

The continuously rising coefficient of variation and consistently positive Moran’s I value that passed significance tests confirm intensifying regional divergence in China’s urban real estate inventory. Inventory accumulation and fluctuations across different cities exhibit spatial dependency and contagion effects [22,58]. Previous studies on spatial heterogeneity and autocorrelation have mainly focused on areas such as real estate prices [59,60], value [61], efficiency [62,63], investment [64], and development [65], while empirical analyses examining the spatial effects of real estate inventory remain relatively scarce. It is worthwhile to note that the “evolutionary dynamics—risk analysis—performance evaluation” framework developed by Zhang et al. reveals that the urban inventory management performance index in the Yangtze River Delta region has remained persistently below 40% over the long term. High-risk zones exhibit a “center-periphery” spatial pattern [22]. Vanneste et al. analyzed and identified four typical spatial patterns emerging in Belgium’s housing stock: north–south disparities, east–west disparities, core-periphery dynamics, and urban-rural duality [66].

The analytical findings of this study represent a further refinement of their research outcomes. Regarding the former, this study extends the spatial pattern from the specific micro-region of the Yangtze River Delta to the national level. For the latter, it demonstrates that the spatial heterogeneity of real estate inventory and its clustering effect exhibit international and universal characteristics. Future empirical analyses in other countries should prioritize the use of spatial econometric models. Furthermore, the regional divergence and spatial dependence of real estate inventory provide a crucial policy implication that a “one-size-fits-all” national inventory management policy has proven ineffective. Future policies must adhere to targeted regulation through “agglomeration-specific measures” and “city-specific measures”, while emphasizing collective prevention and control centered on urban agglomerations [67,68].

Previous research mainly focused on the absolute value of real estate inventory and established a series of static inventory management models, which led to many limitations in the research results and their application in translation [69]. First, it conceals dynamic risks, causing delays in decision-making. As a static indicator, the absolute value cannot reflect whether real estate inventory is accelerating in accumulation or beginning to be absorbed [70]. A city with an extremely high absolute inventory level may be rapidly depleting its stock if sales far outpace new supply. Conversely, a city with a seemingly low absolute inventory may be accumulating inventory risks at an alarming rate if sales stagnate while new projects continuously enter the market [71,72]. Relying solely on absolute inventory metrics is like tracking a vehicle’s position without considering its speed and direction. This approach fails to predict when it will encounter danger, leading to missed opportunities for timely intervention. Second, it becomes impossible to accurately identify the true “problem areas”. The absolute value of the national or regional average inventory may mask significant disparities among cities.” Some third- and fourth-tier small and medium-sized cities may not have high absolute inventory levels, but due to population outflow and dwindling demand, their inventory reduction period (inventory divided by sales pace) is extremely prolonged, effectively rendering the market “stagnant”. While some major cities may have higher absolute values, their faster reduction rates make risks relatively manageable.

To support precise “city-specific measures” and “cluster-based management” policy design, this study employs the Boston Matrix to integrate the relative share and growth rate of real estate inventory, thereby categorizing urban inventory management into four types. This approach establishes robust theoretical and technical foundations for implementing a dynamic monitoring system with tiered early warning capabilities—fundamentally advancing real estate inventory governance from reactive “crisis management” to proactive “risk prevention” paradigms. The relative share metric captures the absolute inventory level, functioning as a real-time pressure indicator for market conditions. The growth rate metric quantifies inventory dynamics, serving as a leading indicator of emerging risk exposure. By employing average values as thresholds for city categorization into specific alert zones, this methodology achieves dual objectives: it enhances policy implementation precision while enabling differentiated approaches, and simultaneously it facilitates governance transition from reactive measures to proactive prevention in real estate inventory governance. Traditional research primarily classifies inventory based on single metrics such as value, cost, or time limit, adhering to a one-dimensional linear logic. This study advances the classification methodology by extending it to two dimensions, achieving methodological refinement [73,74].

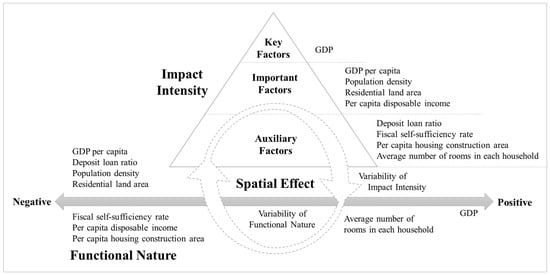

Empirical research using the GWR model demonstrates that the impact mechanism of China’s real estate inventory constitutes a complex system driven by GDP as the overarching core, involving multiple synergistic factors and severely constrained by spatial effects. Economic scale is the only factor that consistently acts as a driver across all cities, while factors such as population and income, land and housing supply, and financial and fiscal instruments simultaneously exert both driving and inhibiting effects. The inertia of China’s economy “being dominated by real estate” remains formidable, and the journey to truly restore housing to its fundamental purpose of providing shelter is still long and arduous [75]. The GWR model reveals strong spatial non stationarity in the influence of all factors, with distinct regional differentiation patterns, forming a typical core edge spatial pattern. Overall, the impact of different factors on real estate inventory involves complex mechanisms, exhibiting distinct characteristics of differentiated nature, stratified intensity, and spatial variation. Future policy design for real estate inventory management must consider the nature and intensity of these factors while focusing on the spatial effects that drive their variability (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Conceptual Analysis of The Driving Mechanism of Real Estate Inventory. Note: Arrows represent the direction of change in influence values and properties.

5. Conclusions

Analyzing real estate inventory trends from temporal and spatial perspectives while delving into the mechanisms of influencing factors holds significant theoretical innovation value and carries great importance for scientifically formulating real estate market regulation policies and guiding enterprises’ inventory management strategies in practice. This study examines the spatiotemporal evolution patterns and influencing factors of real estate inventory in 287 Chinese cities from 2017 to 2022. Using multidisciplinary methodologies including Geographic ESDA, the Boston Matrix from management science, and the geographically weighted regression model from economics, it quantitatively analyzes these phenomena and proposes policy implications.

The findings reveal that, first, China’s real estate inventory management has undergone a cyclical shift from “de-stocking” to “restocking”, with the underlying logic transitioning from policy-driven mechanisms to fundamental economic factors, including demographic trends, income levels, and market expectations. Second, China’s real estate inventory and its fluctuations exhibit distinct temporal and spatial differentiation patterns alongside spatial clustering tendencies, revealing a spatial structure characterized by “multiple clustered highlands with peripheral lowlands” driven by urban clusters. The geographical distribution of cities with high inventory has always had the characteristic of multi-center cluster agglomeration, forming a loose core-periphery structure with the central cities of about 10 representative urban agglomerations as the core. In contrast, the geographical distribution of low-inventory cities has formed a spatial pattern characterized by one major and two minor clusters, with the center of agglomeration gradually shifting from the north to the south. Third, the results of the GWR model-based analysis clearly demonstrate that the impact mechanism of China’s real estate inventory constitutes a complex system driven by macroeconomic factors, regional divergence, and structural contradictions. In short, real estate inventory is not merely a simple accumulation of numbers, but rather the combined result of multiple mismatches in supply and demand across time, space, and structure. It is both the “result” of market imbalance and a warning “signal” for future risks. Effective inventory management must fundamentally regulate supply-demand relationships, optimize supply structures, stimulate real demand, and prevent policy-driven short-term fluctuations from masking long-term structural contradictions.

It is suggested that first of all, the design of destocking policies should shift from “short-term stimulus” to “long-term coordination”. It calls for breaking away from reliance on short-term policy tools (such as credit easing and shantytown renovation), promoting deep alignment between policy and urban fundamentals, and incorporating fundamental indicators like population, income, and expectations into the inventory risk monitoring system. Second, destocking policies should evolve from “industrial policy” to “spatial policy”. It requires incorporating dynamic indicators such as inventory growth rate or destocking period into inventory management frameworks, establishing a real estate inventory dynamic monitoring and risk assessment index. Based on the spatial differentiation and linkage patterns revealed by this new index, efforts should accelerate to develop emerging real estate inventory management tools featuring “dynamic monitoring, targeted governance, and tiered early warning”. Third, the design of destocking policies should shift from addressing superficial market “symptoms” to tackling the “root causes”. To design truly effective and sustainable destocking policies, it is essential to look beyond superficial appearances and gain a deep understanding of the underlying mechanisms at play across different spatial scales. This includes comprehending the scale and purchasing power of population demand, economic geography, and the role of financial and fiscal incentive tools. Policies must precisely align with the nature, intensity, and spatial effects of these influencing factors.

The study’s innovations include: (1) enhancing the accuracy of the analysis results by refining the study scale from the macro level of national and provincial regions to the meso-micro level of cities; (2) enhancing the universality of the findings by expanding the study scope from a small sample of a single city or urban agglomeration to a large sample covering the whole country; (3) developing a dynamic analysis method for real estate inventory by incorporating inventory growth rates, and employing spatial econometric models to examine the causal mechanisms and spatial effects of influencing factors, providing a valuable reference case for real estate inventory management research in other countries around the world.

There are also some limitations in the study. First, the short time series may lead to short-term or phased characteristics in some regular understandings. Future empirical analyses using longer time series data are needed to supplement and validate these findings. The Chinese government’s focus on real estate inventory dates back to around 2011, with national and local policy design and implementation commencing in 2015. During this period, China has accumulated substantial experience and data in managing real estate inventory. However, constrained by the absence of nationally standardized statistical data, the timeframe of this study is limited to 2017–2022. The data currently utilized represents the most comprehensive official information available. Future research may consider employing methods such as web scraping of big data (e.g., from real estate developers’ official websites or third-party platforms like E-House Research Institute and Fang.com) and corporate survey data (e.g., conducting interviews or questionnaires with representative real estate enterprises) to facilitate cross-validation with this study. It is worth noting that conducting empirical analysis using narrowly defined data allows for capturing a significant portion of real estate inventory risks, such as corporate funding chain disruptions, market supply-demand imbalances and liquidity shortages, as well as the effectiveness of policy interventions. However, it may also overlook certain risks, including long-term supply-demand mismatch risks stemming from speculative land reserves and irrational risks arising from distorted market expectations. Second, the dynamic analysis tool developed by integrating the relative share and growth rate of real estate inventory still has considerable room for improvement, with its analytical results being significantly influenced by threshold settings. Subsequent research should consider alternative thresholding approaches including the median value or expert-derived thresholds, with comparative analysis employed to determine the most robust methodology. Additionally, given the abundance of indicators characterizing the dynamics or trends of real estate inventory, growth rates may not necessarily be the optimal choice. Future research may explore utilizing indicators such as inventory reduction period, area of real estate under construction, and area of undeveloped land, and the most suitable approach for the study area can be selected through comparative studies.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Sidong Zhao and Ping Zhang; methodology, Sidong Zhao and Ping Zhang; software, Sidong Zhao and Hua Chen; validation, Hua Chen and Sidong Zhao; formal analysis, Ping Zhang, Jiaoguo Ma; investigation, Hua Chen, Ping Zhang and Jiaoguo Ma; resources, Hua Chen and Ping Zhang; data curation, Hua Chen, Jiaoguo Ma and Ping Zhang; writing—original draft preparation, Ping Zhang and Sidong Zhao; writing—review and editing, Hua Chen and Sidong Zhao; visualization, Ping Zhang; supervision, Sidong Zhao; project administration, Ping Zhang and Sidong Zhao; funding acquisition, Sidong Zhao and Ping Zhang. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding “Zhejiang Provincial Philosophy and Social Sciences Planning Project (22JCXK13YB)” and “Research Project for Philosophy and Social Science Planning of Guangxi Zhuang Autonomous Region in 2024 (24GLF013)”.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The main data comes from the yearbook database of CNKI (https://navi.cnki.net/knavi/detail?p=KWk0lDXI_FqXH2wD6as7hSpLVn_w6ItrKmraVqISF6srmhTLJDk1pTBNIwODiSDvBviBfDzGHV7vPGmgnJcEG3tmnZlZxiHNENYhPXfrOto=&uniplatform=NZKPT, obtained on 12 March 2025), and some data comes from the statistical bulletin and government work report published on the official website of the government, which can be searched or accessed through the Internet.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- de Souza, E.A.G.; Mlinar, T.; van den Broeke, M.; Creemers, S. Dynamic programming in inventory management: A review. Comput. Oper. Res. 2025, 183, 107164. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shekhar, C.; Saurav, A.; Yadav, V. A sustainable two-warehouse inventory management of perishable items: Exploring hybrid cash-advance payment policies and green technology with cap and tax regulations. OPSEARCH 2025, 1–68. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Namazian, Z.; Betts, J.M.; Stuckey, P.J. Predict and Optimize: A Smart Inventory Management Model for Beauty Retail. Optim. Lett. 2025, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Santos, J.A.M.; Martins, M.S.E.; Pinto, R.M.; Vieira, S.M. Towards Sustainable Inventory Management: A Many-Objective Approach to Stock Optimization in Multi-Storage Supply Chains. Algorithms 2024, 17, 271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, K.; Song, Y.Y.; Pan, J.F.; Yang, G.L. Measuring destocking performance of the Chinese real estate industry: A DEA-Malmquist approach. Socio-Econ. Plan. Sci. 2020, 69, 100691. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morales, M.; Moraga, G.; Kirchheim, A.P.; Passuello, A. Regionalized inventory data in LCA of public housing: A comparison between two conventional typologies in southern Brazil. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 238, 117869. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez-Gonzalez, J.E.; Hirs-Garzon, J.; Sanin-Restrepo, S.; Uribe, J.M. Financial and macroeconomic uncertainties and real estate markets. East. Econ. J. 2024, 50, 29–53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oey, E.; Lim, J. Challenges and action plans in construction sector owing to COVID-19 pandemic—A case in Indonesia real estates. Int. J. Lean Six Sigma 2021, 12, 835–858. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gale, H.; Sen Roy, S. Optimization of United States residential real estate investment through geospatial analysis and market timing. Appl. Spat. Anal. Policy 2022, 16, 315–328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bian, X.; Waller, B.D.; Turnbull, G.K.; Wentland, S.A. How many listings are too many? Agent inventory externalities and the residential housing market. J. Hous. Econ. 2015, 28, 130–143. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- K’Akumu, O.A. What is real estate? Five ontological questions for the discipline. J. Eur. Real Estate Res. 2023, 16, 155–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmi, P.C.; Magnusson, L. The Predictive Accuracy of Residential Vacancy Chain Models. Urban Stud. 1994, 31, 1117–1131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Emmi, P.C.; Magnusson, L. Further Evidence on the Accuracy of Residential Vacancy Chain Models. Urban Stud. 1995, 32, 1361–1367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vandell, K.D. Tax structure and natural vacancy rates in the commercial real estate market. Real Estate Econ. 2003, 31, 245–267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferrari, E. Conceptualising Social Housing within the Wider Housing Market: A Vacancy Chain Model. Hous. Stud. 2011, 26, 95–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miceli, T.J.; Sirmans, C.F. Efficiency rents: A new theory of the natural vacancy rate for rental housing. J. Hous. Econ. 2013, 22, 20–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Radzimski, A. Changing policy responses to shrinkage: The case of dealing with housing vacancies in Eastern Germany. Cities 2016, 50, 197–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boessen, A.; Chamberlain, A.W. Neighborhood crime, the housing crisis, and geographic space: Disentangling the consequences of foreclosure and vacancy. J. Urban Aff. 2017, 39, 1122–1137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- McClure, K. The allocation of rental assistance resources: The paradox of high housing costs and high vacancy rates. Int. J. Hous. Policy 2019, 19, 69–94. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Newell, G. Real estate insights: The future of property research. J. Prop. Invest. Financ. 2023, 41, 624–628. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazear, E.P. Why Do Inventories Rise When Demand Falls in Housing and Other Markets? Singap. Econ. Rev. 2012, 57, 1250007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, X.Y.; Huang, X.J.; Li, H.; Li, Y.; Zhao, X.F. Exploring the relationship between urban land supply and housing stock: Evidence from 35 cities in China. Habitat Int. 2018, 77, 80–89. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bogataj, D.; McDonnell, D.R.; Bogataj, M. Management, financing and taxation of housing stock in the shrinking cities of aging societies. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 181, 2–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoo, H.; Yoon, H. The Effect of Green Characteristics in Reducing the Inventory of Unsold Housing in New Residential Developments—A Case of Gyeonggi Province, in South Korea. Land 2021, 10, 377. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petersen, A.M. How much did pandemic uncertainty affect real-estate speculation? Evidence from on-market valuation of for-sale versus rental properties. Appl. Econ. Lett. 2025, 32, 1295–1299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, S.; Guha, S.; Kumar, S. Advancements in Inventory Management: Insights from INFORMS Franz Edelman Award Finalists. Prod. Oper. Manag. 2025, 34, 2063–2082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Geman, H.; Tunaru, R. Commercial Real-Estate Inventory and Theory of Storage. J. Futures Mark. 2013, 33, 675–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Wei, R.; Zhong, C.W. Research on Spatial Spillover Effects and Regional Differences of Urban Housing Price in China. Econ. Comput. Econ. Cybern. Stud. Res. 2021, 55, 211–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Chen, H.; Zhao, K.X.; Zhao, S.D.; Li, W.W. Dynamics, Risk and Management Performance of Urban Real Estate Inventory in Yangtze River Delta. Buildings 2023, 12, 2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, X.Q.; Xu, C.; Hu, Q.Y. Dynamic capacity management with uncertain demand and dynamic price. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2016, 175, 121–131. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kwoun, M.J.; Lee, S.H.; Kim, J.H. Dynamic cycles of unsold new housing stocks, investment in housing, and housing supply-demand. Math. Comput. Model. 2013, 57, 2094–2105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Z.; Shen, L.; Liu, L.T.; Kong, H.X.; Sun, Y.Z. A Probabilistic Dynamic Material Flow Analysis Model for Chinese Urban Housing Stock. J. Ind. Ecol. 2018, 22, 377–391. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.D.; Li, W.W.; Zhao, K.X.; Zhang, P. Change Characteristics and Multilevel Influencing Factors of Real Estate Inventory-Case Studies from 35 Key Cities in China. Land 2021, 10, 928. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, P.; Yang, X.; Chen, H.; Zhao, S. Matching Relationship between Urban Service Industry Land Expansion and Economy Growth in China. Land 2023, 12, 1139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, L.; Zhao, K.; Wang, X.; Zhao, S.; Liu, X.; Li, W. Spatio-Temporal Evolution and Driving Mechanism of Urbanization in Small Cities: Case Study from Guangxi. Land 2022, 11, 415. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Zhang, P.; Zhao, K.; Chen, H.; Zhao, S. The Evolution Model of and Factors Influencing Digital Villages: Evidence from Guangxi, China. Agriculture 2023, 13, 659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.; Wang, M.; Zhao, S. The Spatio-Temporal Dynamics, Driving Mechanism, and Management Strategies for International Students in China under the Background of the Belt and Road Initiatives. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Li, W.; Zhang, P.; Chen, H.; Lai, M.; Zhao, S. The Dynamics and Driving Mechanisms of Rural Revitalization in Western China. Agriculture 2023, 13, 1448. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, S.; Zhang, P.; Li, W. A Study on Evaluation of Influencing Factors for Sustainable Development of Smart Construction Enterprises: Case Study from China. Buildings 2021, 11, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Xu, J.; Zhao, S. Spatiotemporal Dynamics and Influencing Factors of Wood Consumption in China’s Construction Industry. Buildings 2025, 15, 917. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortheringham, S.; Brunsdon, C.H.; Charlton, M. Quantitative Geography; SAGE Publications: London, UK, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Shrestha, A.; Luo, W. Analysis of Groundwater Nitrate Contamination in the Central Valley: Comparison of the Geodetector Method, Principal Component Analysis and Geographically Weighted Regression. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2017, 6, 297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, X.; Liu, K.; Li, W. Symbiotic relationship and attribution analysis of digitalization in agriculture, rural, and finance: Evidence from China. Front. Sustain. Food Syst. 2025, 9, 1545548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, W.W.; Weng, L.S.; Zhao, K.X.; Zhao, S.D.; Zhang, P. Research on the Evaluation of Real Estate Inventory Management in China. Land 2021, 10, 1283. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Olaya, Y.; Vasquez, F.; Muller, D.B. Dwelling stock dynamics for addressing housing deficit. Resour. Conserv. Recycl. 2017, 123, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Serrano-Martinez, J.M.; Garcia-Marin, R.; Lagar-Timon, D. Housing, population and region in Spain: A currently saturated property market with marked regional differences. Geogr. J. 2017, 183, 126–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Coskun, E.A.; Apergis, N.; Coskun, Y. Threshold effects of housing affordability and financial development on the house price-consumptionnexus. Int. J. Financ. Econ. 2020, 27, 1785–1806. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, C.C.; Jia, S.; Yang, R.D. Housing affordability and housing vacancy in China: The role of income inequality. J. Hous. Econ. 2016, 33, 4–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, R.; Zhang, G.Q.; Zhang, Y.; Lan, Y.Z. Exploring the spatially heterogeneous effects of street-level perceived qualities on listed real estate prices using geographically weighted regression (GWR) modeling. Buildings 2024, 14, 1982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Berawi, M.A.; Miraj, P.; Saroji, G.; Sari, M. Impact of rail transit station proximity to commercial property prices: Utilizing big data in urban real estate. J. Big Data 2020, 7, 71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.S.; Wu, W.H.; Li, Y.Q.; Yang, Q.Y. The impacts of land and real estate price fluctuations on financial stability: Evidence from China. Aust. Econ. Rev. 2023, 56, 42–60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sisman, S.; Akar, A.U.; Yalpir, S. The novelty hybrid model development proposal for mass appraisal of real estates in sustainable land management. Surv. Rev. 2023, 55, 1–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xiong, X.; Guo, H.; Hu, X. The housing demand analysis and prediction of the real estate based on the AWGM (1, N) model. Grey Syst.-Theory Appl. 2020, 11, 222–240. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.Y.; Fan, H.; Wang, Y.K. An estimation of housing vacancy rate using NPP-VIIRS night-time light data and OpenStreetMap data. Int. J. Remote Sens. 2019, 40, 8566–8588. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.F. Measuring systemic risk and dependence structure between real estates and banking sectors in China using a CoVaR-copula method. Int. J. Finance Econ. 2021, 26, 5930–5947. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Matsuno, S.J.; Malekian, R.; Yu, J.; Li, Z.X. A vector auto regression model applied to real estate development investment: A statistical analysis. Sustainability 2016, 8, 1082. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miyamoto, S.; Chacon, A.; Hossain, M.; Martinez, L. Soil salinity of urban turf areas irrigated with saline water I. Spatial variability. Landsc. Urban Plan. 2005, 71, 233–241. [Google Scholar]

- Dube, J.; Legros, D. A spatio-temporal measure of spatial dependence: An example using real estate data. Pap. Reg. Sci. 2013, 92, 19–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W.-C.; Chang, Y.-J.; Wang, H.-C. An application of the spatial autocorrelation method on the change of real estate prices in Taitung City. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2019, 8, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pellizzari, C.B.; Eusse-Villa, L.; Franceschinis, C.; Tempesta, T.; Thiene, M.; Vecchiato, D. From peaks to prices: The economic impact of natural amenities on alpine real estate values. J. Eur. Real Estate Res. 2025, 18, 230–249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Januario, J.F.; Costa, A.; Cruz, C.O.; Sarmento, J.M.; Sousa, V.F.E. Transport infrastructure, accessibility, and spillover effects: An empirical analysis of the Portuguese real estate market from 2000 to 2018. Res. Transp. Econ. 2021, 90, 101130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Z.G.; Deng, Z.K.; Qi, Y.W.; Pan, J.S. Spatial-Temporal pattern and evolutionary trend of eco-efficiency of real estate development in the Yangtze River economic belt. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 996152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- An, B.-W.; Xu, P.-Y.; Li, C.-Y.; Zhang, L.-Y.; Guo, Q.-P. Assessing green production efficiency and spatial characteristics of China’s real estate industry based on the undesirable super-SBM model. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 16367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, C.; Wang, J.; Cheng, S. What attracts foreign direct investment in China’s real estate development? Ann. Reg. Sci. 2011, 46, 267–293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, H.; Zhao, S.D.; Zhang, P.; Zhou, Y.; Li, K.R. Dynamics and driving mechanism of real estate in China’s small cities: A case study of Gansu Province. Buildings 2022, 12, 1512. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vanneste, D.; Thomas, I.; Vanderstraeten, L. The spatial structure(s) of the Belgian housing stock. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2008, 23, 173–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Y.; Zhang, H.T.; Zhao, Y. Structural evolution of real estate industry in China: 2002–2017. Struct. Change Econ. Dyn. 2021, 57, 45–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, M. Upzoning and value capture: How US local governments use land use regulation power to create and capture value from real estate developments. Land Use Policy 2020, 95, 104624. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgonovo, E. Differential importance and comparative statics: An application to inventory management. Int. J. Prod. Econ. 2008, 111, 170–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, T.F.; Li, R.Y.M.; Deeprasert, J. Model Optimization and Dynamic Analysis of Inventory Management in Manufacturing Enterprises. Information 2024, 15, 785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- da Cruz, J.A.; de Salles-Neto, L.L.; Schenekemberg, C.M. A Rolling Horizon Approach for a Production Planning and Inventory Management Problem Under Stochastic Demand. Process Integr. Optim. Sustain. 2025, 9, 2021–2046. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, H.; Li, X.Q.; Fu, X. Periodic review inventory management considering dynamic demand distribution. Int. J. Syst. Sci.-Oper. Logist. 2025, 12, 2512861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grützner, L.; Breitner, M.H. Bridging the implementation gap in MCABC inventory management: From a taxonomy to practical archetypes. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2025, 70083. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Auqui-Aguirre, O.; Cabezas-Yupanqui, L.D.; Medina-Jimenez, C. Inventory management using the ABC classification method in the warehouse of Tectum, Peru. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Technology and Engineering Management Society (TEMSCON LATAM 2024), Panama City, Panama, 18–19 July 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Levine, D.; Aharon-Gutman, M. There’s no place like real estate: The “Self-gentrification” of homeowners in disadvantaged neighborhoods facing urban regeneration. J. Hous. Built Environ. 2022, 38, 775–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |