Abstract

Accurate point cloud registration is a fundamental prerequisite for reality-based 3D reconstruction and large-scale spatial modeling. Despite significant international progress, reliable registration in architectural and urban scenes remains challenging due to geometric intricacies arising from repetitive and strongly symmetric structures and photometric variability caused by illumination inconsistencies. Conventional ICP-based and color-augmented methods often suffer from local convergence and color drift, limiting their robustness in large-scale real-world applications. To address these challenges, we propose Hybrid Adaptive Residual Optimization (HARO), a unified framework that organically integrates geometric cues with hue-robust color features. Specifically, RGB data are transformed into a decoupled HSV representation with histogram-matched hue correction applied in overlapping regions, enabling illumination-invariant color modeling. Furthermore, a novel adaptive residual kernel dynamically balances geometric and chromatic constraints, ensuring stable convergence even in structurally complex or partially overlapping scenes. Extensive experiments conducted on diverse real-world datasets, including Subway, Railway, urban, and Office environments, demonstrate that HARO consistently achieves sub-degree rotational accuracy (0.11°) and negligible translation errors relative to the scene scale. These results indicate that HARO provides an effective and generalizable solution for large-scale point cloud registration, successfully bridging geometric complexity and photometric variability in reality-based reconstruction tasks.

1. Introduction

Fine registration is a fundamental technique underpinning a wide range of applications, including reality-based 3D reconstruction [1], robotics [2], remote sensing [3], autonomous driving [4], and manufacturing [5]. It typically involves iterative alternation between nearest-neighbor correspondence estimation and distance metric minimization, aiming to converge toward a locally optimal alignment. Accurate fine registration is therefore essential for achieving high-precision point cloud fusion in practical systems.

Traditional geometry-based registration methods, most notably the Iterative Closest Point (ICP) algorithm and its variants, have been widely adopted and demonstrate reliable performance in small-scale or geometrically simple scenarios [6,7]. To alleviate geometric ambiguities and improve correspondence reliability, recent studies have explored the incorporation of color information into the registration process. By exploiting chromatic cues, color-augmented methods can enhance matching robustness in regions with weak or symmetric geometric structures [8].

Despite these advances, reliable fine registration in large-scale architectural scenes remains an open research challenge. In real-world environments, two fundamental limitations of existing methods become particularly pronounced. First, architectural scenes are often dominated by repetitive structures and strong symmetries, which significantly increase the ambiguity of geometric correspondences and exacerbate the risk of convergence to incorrect local minima [9]. Second, although color information can effectively complement geometric cues, it is highly sensitive to illumination variations and exposure inconsistencies, leading to color drift and unstable optimization behavior [10]. The coexistence of geometric ambiguity and photometric variability poses a critical challenge for large-scale point cloud registration in practice.

From a problem-driven perspective, the core research question addressed in this work is how to achieve robust and accurate large-scale point cloud registration in real-world scenes where geometric complexity and photometric inconsistency coexist. To this end, we propose a Hybrid Adaptive Residual Optimization (HARO) framework, which integrates geometry-driven alignment with hue-robust color modeling. Specifically, HARO introduces an illumination-invariant hue correction strategy and a hybrid adaptive residual formulation to dynamically balance geometric and chromatic constraints during optimization. This design effectively mitigates color drift while enhancing robustness against local minima in structurally complex scenarios. The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

- Hue-Robust Color Correction: We introduce a hue histogram specification strategy for overlapping regions that ensures illumination-invariant color consistency, effectively suppressing cross-view drift and providing reliable chromatic features for large-scale registration.

- Hybrid Adaptive Residual Optimization: We propose a unified optimization framework that adaptively balances geometric and chromatic residuals via robust kernel weighting and scale normalization, achieving stable convergence and reduced sensitivity to local minima in complex architectural environments.

- Comprehensive Experimental Validation: HARO consistently outperforms geometry-only and color-augmented baselines, reducing registration errors by up to 70% and demonstrating superior robustness and scalability across diverse large-scale datasets.

The remainder of this paper is structured as follows: Section 2 provides a comprehensive review of existing fine registration methods. Section 3 provides a detailed elaboration of the proposed HARO framework. Experimental results, obtained using open-source and self-collected datasets, are presented and thoroughly discussed in Section 4. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the key findings and concludes the paper.

2. Related Works

Existing methods for fine registration can be broadly divided into two categories: geometry-based approaches, which rely solely on spatial coordinates, and color-augmented approaches, which incorporate photometric information as complementary cues. While geometry-based methods remain the mainstream due to their simplicity and generality, they face intrinsic challenges in large-scale or structurally complex environments. Color-augmented registration was therefore introduced to alleviate geometric ambiguities; however, its sensitivity to illumination and scale still limits robustness. Below, we review both research directions and highlight their respective advantages and shortcomings.

2.1. Geometry-Based Fine Registration

The ICP-based methods established correspondences between points using covariance matrices of associated points and applied singular value decomposition to estimate the translation vector of centroids [11]. By iteratively accumulating rotation and translation errors, the final pose transformation can be obtained. Under reliable initial alignment, classical ICP achieves satisfactory results. With advances in data structures and computational techniques, methods such as KD-Tree [12] and various sampling strategies [13] have accelerated the NN search process, facilitating practical deployment. The primary source of registration errors in ICP stems from incorrect point correspondences, motivating the development of keypoint selection strategies that exploit local geometric features or normal-space sampling to reduce mismatches.

As correspondence establishment is a core step to ICP, considerable research has focused on improving this process [14,15]. Zhang et al. [16] utilized distance distribution statistics to enhance robustness. Variants such as GFOICP [6] progressively reduce distance thresholds during iterations, while TrICP [17] employs truncated least squares regression to mitigate outlier influence. Another key direction lies in designing error metrics, which critically affect alignment quality. Weighted metrics, as in GICP [18], Sparse-ICP [19], and FRICP [20], assign different importance to points based on correspondence likelihood, enabling more effective handling of outliers and non-overlapping regions. Other extensions, including LM-ICP [21], AA-ICP [22], Symmetric-ICP [23], Fast ICP [24], and NICP [25], further refine error functions or convergence strategies to expand convergence domains and accelerate optimization. These improvements often leverage surface normals, curvature descriptors, or iterative history to stabilize registration.

To mitigate ICP’s vulnerability to local minima, global optimization strategies have also been developed. Go-ICP [26] applies a branch-and-bound search in the Lie algebra space to guarantee global optimality, while KSS-ICP [2] introduces the Kendall shape space to decouple pose parameters, improving robustness against noisy or non-uniform data. Despite such progress, geometry-only ICP variants generally assume high-quality input and remain sensitive to centroid deviations, noise, and initialization. Their computational burden also grows significantly with scale, limiting their applicability in real-world settings.

Geometry-based ICP methods have demonstrated reliable performance on small-scale and structurally simple point clouds. However, their application to large-scale, complex environments exposes several intrinsic limitations. First, these methods are highly sensitive to initialization and prone to convergence at incorrect local minima, which undermines alignment accuracy. Second, the iterative update process can exhibit oscillations or divergence, reducing stability and sharply increasing computational cost as the scale increases. Third, geometric-only approaches struggle to cope with noise, dynamic disturbances, and the repetitive or symmetric structures prevalent in architectural scenes, which often lead to ambiguous correspondences.

2.2. Color-Augmented Fine Registration

The integration of geometric and color information has been shown to improve robustness in challenging scenarios, particularly those characterized by repetitive structures or limited geometric variation. By leveraging complementary cues, researchers have developed methods that enhance registration accuracy, stability, and convergence speed in complex and symmetric environments. Broadly, color-augmented fine registration techniques can be categorized into two groups: hybrid feature-based methods and ICP-based extensions.

In hybrid feature-based approaches, color attributes are combined with geometric descriptors to improve correspondence establishment. For example, Chen et al. [27] proposed a method combining color moment information with geometric features to establish correspondences, dynamically integrating both modalities to improve registration accuracy under occlusion, geometric defects, and inaccurate initial poses. Wan et al. [28] combined color information with complex feature extraction and maximum correlation entropy criteria, effectively addressing registration in point clouds lacking distinctive geometric structures. Similarly, Park et al. [10] incorporated geometric and photometric cues into a joint optimization framework to minimize a unified cost function, improving registration robustness. Gupta et al. [29] introduced the NDT-6D method, combining geometric and color information in normal distribution transforms for robust registration, with applications in large-scale agricultural environments. Wan et al. [30] further developed a composite keypoint detection algorithm leveraging both geometric and color saliency, enhancing the reliability of fine registration in colorized point clouds.

For ICP-based extensions, it augments the iterative closest point framework with color constraints. Men et al. [31] employed hue values in 4D KD-Tree searches, mitigating ambiguities in purely geometric matching. Korn et al. [32] extended the ICP framework by incorporating hue and LAB color channels, improving transformation accuracy while reducing computational cost. Choi et al. [33] proposed a KNN soft-matching ICP algorithm supporting color models, enhancing alignment precision. To address scenarios with significant illumination-induced color variations, Liu et al. [34] introduced a genetic algorithm-based strategy to improve robustness under extreme registration conditions.

Despite notable progress, color-augmented fine registration methods still face several intrinsic limitations when applied to large-scale, real-world scenarios. First, most existing approaches have been developed and validated primarily on indoor or small-scale datasets, leaving their robustness and generalizability underexplored in complex environments. Second, while photometric cues can effectively resolve geometric ambiguities in repetitive or symmetric regions, they are highly sensitive to illumination changes, exposure inconsistencies, and sensor noise, which can destabilize the optimization process. Third, ICP-based extensions that integrate color information often incur significant computational overhead, restricting their scalability and practical deployment in large-scale point cloud registration. Collectively, these challenges underscore the need for a unified framework that can robustly leverage both geometric and photometric cues while maintaining efficiency across diverse, large-scale scenarios.

3. Materials and Methods

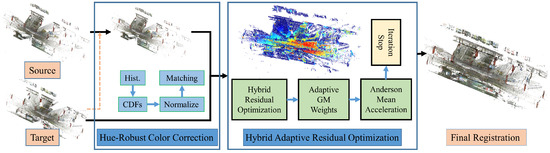

We propose Hybrid Adaptive Residual Optimization (HARO), a unified framework for large-scale point cloud registration that simultaneously enhances geometric alignment and photometric consistency, as illustrated in Figure 1. Specifically, HARO comprises two core modules. First, a Hue-Robust Color Correction strategy is employed to improve inter-frame chromatic consistency and contrast, effectively mitigating illumination-induced color drift across overlapping regions. Subsequently, a Hybrid Residual Optimization module jointly optimizes geometric and hue residuals using an adaptive Geman–McClure (GM) kernel, which dynamically suppresses mismatches and outliers while balancing multi-modal constraints. Collectively, these components enable HARO to overcome the limitations of existing geometry-only and color-augmented approaches, providing robust, accurate, and scalable registration in structurally complex and large-scale environments.

Figure 1.

Pipeline for hybrid adaptive residual optimization (HARO).

3.1. Hue-Robust Color Correction Strategy

In colorized point cloud registration, photometric information provides complementary constraints to geometric features, enhancing texture consistency and improving robustness in weakly structured regions. However, data acquisitions often introduce distortions in color distributions due to uneven illumination, sensor limitations, and calibration errors. Over- or underexposed conditions, especially near object boundaries, further degrade the stability of color-augmented joint optimization.

To address these challenges, we propose a Hue-Robust Color Correction strategy in the HSV model. By decoupling chromaticity from intensity, the hue channel is largely invariant to illumination changes, providing a reliable basis for cross-view color alignment. Specifically, point cloud colors are first transformed from RGB to HSV space, and the hue channel is the primary feature for statistical analysis (Equation (1)).

where R, G, B denote the color channel values of the point cloud. This transformation spatially decouples the color channels, thereby enhancing the stability of color distribution alignment across point clouds and mitigating drift that could compromise registration accuracy.

To capture the statistical distribution of the hue channel, we compute the histogram of hue for the source point cloud and the target point cloud with discrete levels, denoted as and , respectively. The cumulative distribution functions (CDFs) are then calculated using Equation (2).

where i denotes the hue level, typically normalized to . and represent the cumulative probability of the i-th hue level for the source and target point clouds, respectively.

To eliminate the influence of differing point cloud scales on the statistical distribution, the CDFs are normalized by the total number of overlapping points using Equation (3).

where and denote the number of points in the overlapping regions of the source and target point clouds, respectively. The overlapping point is determined using the KNN [35], where correspondences are established between points from the source and target point clouds if the Euclidean distance is less than threshold .

The histogram matching for the hue channel mapping function f is defined as Equation (4).

where denotes the inverse cumulative distribution function of the target distribution. The transformed hue values are obtained using Equation (5).

where is statistically aligned with , thereby compensating for illumination differences and sensor response variations across point clouds. This correct process achieves fine registration of the hue distributions between point clouds and , effectively mitigating color drift caused by illumination differences.

In summary, the proposed hue histogram correction strategies in HSV space mitigate cross-view color drift and enhance statistical consistency across point clouds. By aligning the hue channel, it ensures a more robust color channel under weak geometric structures or varying illumination, thereby strengthening the robustness and accuracy of geometry–color hybrid optimization. This step establishes a stable basis for the subsequent optimization framework.

3.2. Hybrid Adaptive Residual Optimization

Traditional ICP methods, which rely only on geometric or color-fusion residuals, often become trapped in local minima and exhibit unstable convergence, particularly in scenes with repetitive or symmetric structures. To overcome these limitations, we propose a HARO framework that synergistically leverages geometric and hue-based color residuals within an adaptive robust kernel.

Specifically, HARO operates within a fixed-point iterative framework, where each iteration seeks a self-consistent alignment between the source and target point clouds. At the k-th iteration, given the current rigid transformation estimates and , the source point cloud is transformed to , and the nearest neighbor of each transformed point in the target cloud is searched to construct correspondences, as expressed in Equation (6).

where denotes the transformed source point. To accelerate NN search in large-scale point clouds, a KD-Tree structure is employed for efficient querying of .

Once correspondences are established, the transformation parameters and are iteratively updated by minimizing estimated residuals. Classic ICP considers only geometric error, which is insufficient in regions with weak structure or texture degradation. To address this, we incorporate a hue-based color consistency constraint, constructing a hybrid residual function , as expressed in Equation (7).

where is the weight for the hue channel, is the geometric residual, and is the color residual. The geometric residual is defined as Equation (8).

and the hue channel is expressed as Equation (9).

where denotes the hue of the corresponding point. The hue channel is largely invariant to overall illumination variations and closely corresponds to real color perception, thereby mitigating the effects of lighting changes and sensor response inconsistencies.

After constructing correspondences and residuals, the optimization definition is a global minimization of the hybrid function, as expressed in Equation (10):

where n is the point cloud index, and N is the number of correspondence points. This forms a closed-loop of alternating correspondence search and residual convergence. In each iteration, correspondence updates correct geometric and color deviations, while cost minimization refines the transformation to reduce residuals.

To enhance the robustness of point cloud registration in complex environments, we propose a hybrid adaptive residual framework integrated with a GM kernel, enabling an adaptive weighting mechanism for residuals. This framework adjusts the confidence weight of each correspondence during iterations and employs a Majorization–Minimization (MM) [36] strategy for efficient energy minimization.

Euclidean distance used in conventional ICP is sensitive to non-uniform sampling and mismatches, especially in large-scale scenes. To mitigate this, the GM kernel is applied to the hybrid residual r:

where v is the residual scale parameter controlling the suppression strength for outliers. As , , the weight of abnormal correspondences is effectively reduced.

To adapt the kernel to different scenes, the scale parameter v is dynamically estimated using the median absolute deviation (MAD) of current iteration residuals:

where s is a scaling factor, and denotes the residuals of all correspondence pairs. This strategy enhances local consistency while suppressing the influence of global noise.

To optimize the robust residual model efficiently, an MM strategy is employed. Denoting the joint function as , at the k-th iteration, a agent function is constructed satisfying

and the update is performed by minimizing the agent function:

Specifically, incorporating the GM kernel and hybrid residuals, the surrogate function is defined as Equation (15):

with is a non-convex robust penalty function.

Since is concave with respect to the squared residual , a quadratic majorizer can be derived via first-order Taylor expansion. At iteration k, the surrogate function is given by

where the adaptive weight is defined as

and .

By minimizing the surrogate function in Equation (16), the transformation parameters are updated by solving a weighted least-squares problem:

This MM-based optimization guarantees a monotonic decrease of the original non-convex objective and converges to a stationary point under standard conditions.

3.3. Stopping Strategy

The iterative optimization in HARO is performed until a predefined convergence criterion is met, ensuring precise and stable alignment. Formally, let denote the hybrid residual at the k-th iteration. The stopping condition is defined as Equation (19):

where is the residual threshold, and is the maximum number of iterations allowed. Once either condition is satisfied, the algorithm terminates and outputs the final transformation parameters , corresponding to the optimal fine registration result.

To further enhance convergence efficiency, HARO integrates Anderson acceleration [37] into the fixed-point iterative framework. By leveraging a linear combination of historical iterates, Anderson acceleration expedites convergence, mitigates oscillations, and stabilizes the update of the color–geometry hybrid residual. The fixed-point formulation of the MM update is expressed as Equation (20):

where denotes the update function derived from minimizing the fusion residuals, formally defined in Equation (21):

To ensure stability in non-convex or noisy environments, it may induce oscillations or divergence in non-convex or noisy scenarios. To ensure stability, HARO adopts a conservative update strategy: the accelerated iterate is accepted only when the hybrid residual satisfies ; otherwise, the update reverts to the original MM output .

The HARO framework, underpinned by a fixed-point MM solver and enhanced by Anderson acceleration, simultaneously addresses the challenges of local minima, multi-source residual balancing, and slow convergence in large-scale colorized point clouds. By integrating geometric and hue constraints within an adaptive kernel, HARO achieves high-precision, robust, and computationally efficient registration, providing a theoretically grounded and practically effective solution for complex 3D reconstruction tasks.

4. Experiment and Analysis

4.1. Experiment Data Introduction

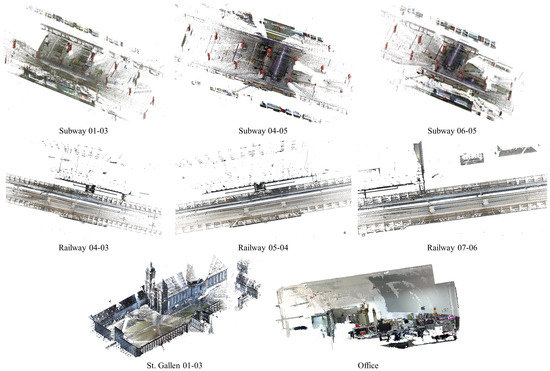

To rigorously evaluate the performance of the HARO method, we conducted experiments on four large-scale colorized architectural point cloud datasets—selected due to their availability of open-source data, provision of coarse registration results, and their representative coverage of typical challenges in real-world registration tasks. These datasets collectively form a demanding benchmark for assessing HARO’s capability in large-scale built-environment scenarios. For instance, WHU-TLS Subway and Railway [38] represents a closed underground environment captured via terrestrial laser scanning, featuring strong illumination variations and color inconsistencies alongside continuous geometric textures and uniform structural patterns, which complicate feature matching based on color and geometry. St. Gallen [39] is a large-scale urban architectural dataset characterized by extremely high point density and rich texture information. The scene combines extensive geometric symmetry with localized structural irregularities, posing significant difficulty in establishing correct correspondences and avoiding local minima in highly repetitive and symmetric regions—a common challenge in large-scale facade registration. Self-collected Office presents a typical indoor office environment with intricate geometric layouts, glass surfaces, fine-grained textures, and symmetrical components. Occlusions, reflective materials, and subtle color variations further increase the difficulty of correspondence search and hybrid residual optimization.

The detailed attributes of these datasets are summarized in Table 1. Together, they provide a rigorous and representative testbed that spans geometric complexity, strong symmetry, illumination changes, and texture ambiguity—enabling a focused evaluation of HARO’s robustness, convergence behavior, and high-precision registration performance under conditions typical of large-scale architectural point cloud processing, using available open datasets with provided coarse alignment as initial inputs.

Table 1.

Detailed scenario information for the test.

To achieve realistic operating conditions for fine registration algorithms, all datasets underwent an initial coarse alignment. WHU-TLS includes the Subway and Railway scenarios, which use a coarse registration method from the literature [40] to achieve preliminary alignment, and St and Office use K4PCS [41] to achieve coarse alignment. Despite being acquired with high-end laser scanning systems and precise alignment, the open-source scenarios still contain various imperfections, such as residual geometric noise, color inconsistencies, and uneven point densities. These factors make them suitable for robust evaluation of fine registration algorithms in realistic, challenging scenarios. The initial position of the datasets related to the experiment are presented in Table 2.

Table 2.

Initial rotation and translation errors for different datasets.

4.2. Experimental Setup

The datasets employed, including both open-source and self-collected samples, encompass structural complexity, repetitive patterns, noise, and pose perturbations, offering a realistic benchmark for evaluating HARO. Parameter settings are summarized in Table 3, balancing scenario characteristics, convergence stability, and efficiency. The alignment residual threshold determines optimization termination, with larger values for structurally extensive cases (e.g., Subway) to handle severe misalignment, and smaller values for more regular scenes (e.g., St. Gallen) to enhance precision. The weighting coefficient regulates the contribution of geometric versus chromatic residuals: lower values emphasize geometry when color is unreliable, while balanced settings exploit both cues for robustness in diverse structures. The maximum iteration is adjusted to the data scale and noise level, ensuring convergence without unnecessary overhead. These adaptive choices enable HARO to consistently deliver stable and accurate registration across large-scale point clouds.

Table 3.

Parameter settings of HARO for different scenarios.

All experiments were performed on a workstation equipped with an Intel Core i7-14700K CPU, 128 GB RAM, and an NVIDIA RTX 4090 GPU for color rendering and visualization. This configuration provides sufficient computational resources for large-scale, high-density point cloud processing.

4.3. Evaluation Metrics

To comprehensively evaluate the accuracy of point cloud registration, three metrics were employed: rotation error (°), translation error (m), and time (s). The angular difference between the estimated rotation and the ground truth rotation is defined as Equation (22).

where denotes the trace of a matrix.

The Euclidean distance between the estimated translation and the ground truth translation is defined as Equation (23).

4.4. Qualitative Evaluations

HARO consistently achieves high-precision registration and stable convergence across all tested scenarios, as reported in Table 4. The quantitative results reveal that rotational errors remain within 0.22° and translational deviations are generally constrained below the decimeter scale, even in highly challenging environments. Such performance indicates that HARO not only preserves global structural alignment but also maintains fine local consistency, effectively meeting the accuracy requirements of large-scale applications.

Table 4.

Fine registration performance of HARO in the four test scenarios.

In large-scale infrastructure datasets such as the Subway scenario, HARO achieves sub-decimeter accuracy despite severe structural symmetry and limited overlap. The visualization results for all test scenarios are illustrated in Figure 2. For example, in the Subway 06–05 pair, rotational and translational errors are reduced to 0.03° and 0.208 m, respectively, demonstrating robustness under substantial perturbations. Qualitatively, major symmetric elements such as columns are aligned without noticeable drift, and long corridors as well as railway tracks exhibit seamless continuity, yielding visually consistent reconstructions. In St. Gallen scenarios, HARO further sustains reliable performance, achieving 0.12° rotation and 0.153m translation error. Visual inspection confirms the preservation of rooftops, façade continuity, and precise window alignment, indicating the framework’s capability to resolve repetitive and symmetric structures without degeneracy. In a relatively small-scale indoor Office, HARO reaches near-perfect registration, with translational error as low as 0.008 m. The resulting reconstructions maintain millimeter-level geometric fidelity even in dense and cluttered spaces.

Figure 2.

Fine registration results of HARO in the four test scenarios.

Collectively, these quantitative results and qualitative visualizations demonstrate HARO’s effectiveness across scales, from global structural recovery in large infrastructure to fine-grained alignment in indoor scenes, establishing a unified solution for robust and precise colorized point cloud registration.

Aggregating results across all scenarios, HARO achieves a mean rotational error of 0.11° and a translational error of 0.152 m. These results confirm both the precision and robustness of the approach, as errors remain negligible relative to the spatial extents of the test scenes. Moreover, the average processing time per pair, ranging from 6.8 s in small-scale Office scenes to approximately 53.7 s in the largest Subway environments, reflects a computational overhead that is acceptable for fine registration tasks, particularly given the achieved accuracy. Collectively, these quantitative results and qualitative visualizations demonstrate HARO’s effectiveness across scales, from global structural recovery in large infrastructure to fine-grained alignment in indoor scenes, establishing a unified solution for robust and precise colorized point cloud registration.

4.5. Quantitative Evaluations and Comparison

To comprehensively validate the advantages of the proposed HARO, a series of systematic comparative experiments was designed. The comparison is organized into two categories: geometry-only ICP methods and color-augmented ICP methods. For geometry-based registration, several representative classical and advanced ICP variants were selected as baselines, including the classical Iterative Closest Point (ICP) [42]; Generalized ICP (GICP) with local covariance modeling [18]; Robust ICP with outlier suppression [43]; Fast ICP emphasizing computational efficiency [44]; Sparse ICP with sparse matrix optimization [45]; AA-ICP with Anderson acceleration [22]; IKCP integrating keypoint extraction with iterative refinement [33]; and recent SLAM approaches addressing degeneracy and real-time performance, such as X-ICP [46] and Kiss-ICP [7]. For color-augmented methods, three representative approaches were considered: 4D ICP incorporating RGB channels directly into distance metrics [31]; ColorICP with joint color–geometry residual modeling [10]; and CFRICP integrating robust kernels with color fusion [47]. Through these methods, the objective is twofold: (i) to evaluate the improvements of HARO over geometry-only methods in terms of accuracy and robustness, and (ii) to verify whether its hybrid design outperforms existing color-based approaches, thereby confirming its effectiveness and advancement in color-augmented point cloud fine registration.

The experimental results of all comparison algorithms are summarized in Table 5. To ensure fair comparison and avoid introducing dataset-specific bias, all baseline methods were executed using their official default parameter settings without any manual tuning. This strategy guarantees consistent evaluation across all datasets while adhering to the recommended practices of the original implementations.

Table 5.

Comparison results of fine registration.

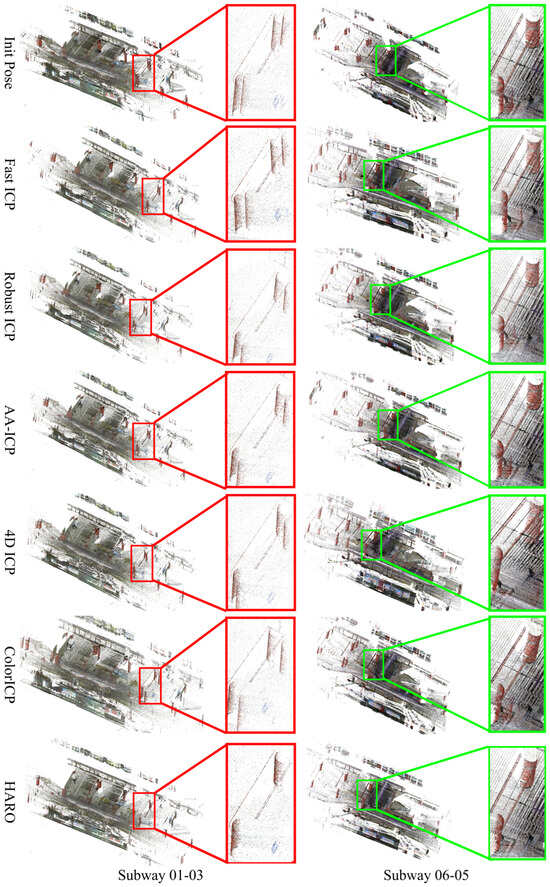

Figure 3 illustrates the registration performance on the Subway scenario. The HARO method generally achieves the best in overlap ratios and varying initial pose discrepancies. The experiments were conducted on two large-scale Subway registration pairs, 01-03, with a relatively high overlap, and 06-05 with a much lower overlap. The results highlight a consistent trend, while conventional geometry-only methods (e.g., ICP, GICP, SparseICP) exhibit degraded performance with increasing structural redundancy and reduced overlap, leading to translational errors exceeding tens of meters. HARO maintains sub-degree rotational accuracy and sub-decimeter translational alignment across both cases. In the higher-overlap pair, HARO achieves a translation error of only 0.133 m, significantly outperforming all baselines in accuracy, even when some geometry-based variants (e.g., Robust ICP, IKCP) achieve lower rotational errors but fail to suppress large translation drifts. In the challenging low-overlap case, HARO further demonstrates its resilience, reducing the rotational error to 0.03° and the translational error to 0.208 m, where all competing methods suffer from either divergence or multi-meter misalignment. Qualitative inspection corroborates these findings: global structures such as tunnels, columns, and platforms remain consistently aligned without visible drift, even under limited overlap. This comparative analysis underscores a key strength of HARO, its ability to adaptively balance geometric and chromatic cues, thereby ensuring stable convergence across scenarios with both high and low overlap ratios.

Figure 3.

Comparison of registration results in Subway scenario with different overlap ratios.

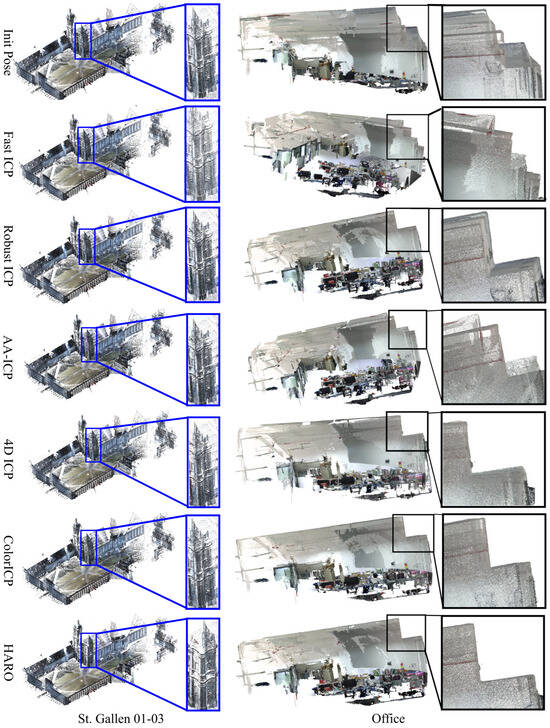

Figure 4 presents the results in the St. Gallen and Office scenarios. In the St. Gallen scenario, the differences and trends in rotation and translation errors across methods are clearly observable. geometric-based approaches exhibit notable fluctuations in registration accuracy when confronted with large-scale repetitive structures or highly symmetric architectural environments, with rotation errors ranging from 0.45° to 8.62° and translation errors from 0.028 to 7.123 m. Lightweight algorithms such as Fast ICP and X-ICP achieve shorter computation times but are limited in overall accuracy, while time-consuming methods like ICP, GICP, and AA-ICP show only marginal improvements even with high iteration counts, indicating the inherent limitations of purely geometric constraints in complex structures. In contrast, color-informed registration approaches significantly enhance point cloud alignment performance. Methods such as ColorICP, 4D ICP, CFRICP, and HARO consistently outperform geometric-only methods in both rotation and translation errors. Notably, CFRICP and HARO achieve rotation errors as low as 0.12°∼0.45° and translation errors in the range of 0.028∼0.153 m. This demonstrates that incorporating color channels provides additional constraints in texture-rich and geometrically repetitive architectural scenes, reducing registration ambiguities and improving point correspondence accuracy.

Figure 4.

Comparison of registration results in St. Gallen and Office Scenarios.

In the Office experiments, purely geometric methods exhibited notable fluctuations in rotation and translation errors. Lightweight algorithms such as Fast ICP, Robust ICP, IKCP and ColorICP achieved millimeter-level accuracy but suffered from rotational deviations, particularly in regions with complex textures or local geometric repetitions. AA-ICP incurred substantial computational costs and frequently converged to local optima in symmetric structures. In contrast, color-informed registration methods substantially improved performance. ColorICP and CFRICP consistently outperformed most geometric-only approaches in both rotation and translation errors, demonstrating that color constraints effectively reduce registration ambiguities and enhance point correspondence accuracy in texture-rich and repetitive structural environments. HARO further achieved superior results, with rotation and translation errors of only 0.12° and 0.008 m, respectively, illustrating its high adaptability to complex indoor scenes. The advantages of HARO stem from its hybrid adaptive residual optimization: by integrating robust color and geometric features, it resolves ambiguities caused by repetitive structures, suppresses outlier effects using a robust kernel function, and accelerates convergence through the Anderson acceleration strategy, thereby ensuring both high-precision and stable iteration.

In summary, the proposed hybrid adaptive residual optimization framework offers a synergistic integration of complementary information and robust optimization strategies. By combining geometry–color residuals, outlier-resistant kernel functions, and accelerated convergence mechanisms, HARO substantially enhances precision, robustness, and stability in large-scale point cloud registration. Consequently, although lightweight methods are computationally efficient, hybrid residual modeling is indispensable for achieving reliable and accurate registration in large-scale environments.

4.6. Ablation Study on Core Modules of HARO

To quantitatively assess the contribution of each core component within the proposed registration framework, we conducted an ablation study on the Office scenario. The analysis focuses on three critical modules: hue normalization, robust kernel selection, and the Anderson acceleration strategy.

The full HARO method integrates hue-channel histogram matching for color normalization, an adaptive GM robust kernel, and Anderson acceleration for iterative optimization. To isolate the effect of each component, we designed three controlled ablation variants: (1) No Hue Histogram Correction: raw hue values are directly used without normalization to evaluate the impact of color consistency across frames. (2) Welsch Kernel: The GM kernel is replaced with the Welsch function to analyze the sensitivity of robust kernel selection. (3) LM Optimization: Anderson acceleration is removed and replaced by the standard Levenberg–Marquardt (LM) method to study the trade-off between convergence accuracy and computational efficiency.

As summarized in Table 6, each component plays a crucial role in achieving the final performance of HARO. First, replacing the GM kernel with the Welsch function causes a clear degradation, increasing the rotation error to and translation error to 0.122 m. This highlights that the GM kernel achieves a more favorable balance between robustness and numerical stability when handling outliers in both geometric and color residuals. Second, removing Anderson acceleration and reverting to LM optimization drastically slows down convergence while also reducing accuracy. This confirms the essential role of Anderson acceleration in maintaining fast and stable convergence in high-dimensional parameter spaces. Finally, omitting hue histogram matching leads to moderate accuracy degradation, showing that while raw hue values preserve local contrast, global histogram normalization ensures consistent color alignment across varying illumination conditions.

Table 6.

Ablation study of HARO modules.

Overall, the full HARO achieves the best balance between accuracy and efficiency. These ablation results validate the necessity of each module and demonstrate the effectiveness of the modular design in ensuring robustness and precision in fine-grained point cloud registration.

4.7. Ablation Study on HARO Under Geometry Noise and Color Variations

To systematically assess the robustness and adaptability of HARO under realistic perturbations, we conducted ablation experiments on the Office scenario, focusing on two common sources of degradation: geometric noise in point cloud coordinates and illumination-induced color variations. These experiments were designed to quantify the sensitivity of the proposed framework under controlled yet progressively challenging conditions.

First, Gaussian noise with increasing standard deviations (10 mm, 20 mm, 30 mm, 50 mm, and 100 mm) is added to the 3D coordinates of the input point clouds to simulate degraded acquisition quality at different precision levels, as processed in Equation (24).

Second, to examine robustness to illumination variations, we introduce random spectral shifts into the color channels using different perturbation coefficients ( = 0.15, 0.3, 0.4, 0.5, 1.0), corresponding to daylight, cloudy, overcast, dusk, and extreme conditions, respectively, as defined in Equation (25).

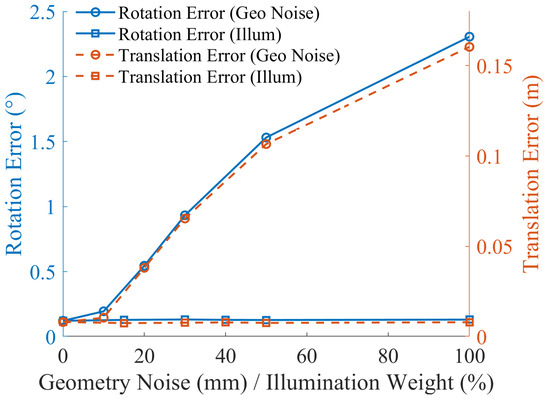

Table 7 and Figure 5 summarize the quantitative results of the ablation experiments, which are designed to evaluate HARO’s robustness against two common sources of perturbation: geometric noise and illumination variations. These experiments systematically assess how each type of disturbance affects registration accuracy and illustrate the effectiveness of the proposed hybrid adaptive residual framework.

Table 7.

Ablation experiment results of point cloud geometric noise and illumination changes.

Figure 5.

Ablation study on geometric noise and illumination changes.

As expected, the registration errors increase progressively with the magnitude of added Gaussian noise to the geometry coordinates. Even under severe perturbations ( mm), HARO maintains a rotational error of 2.306° and a translational error of m. This resilience demonstrates the framework’s capability to suppress the influence of outliers and large residuals, a property primarily attributed to the adaptive GM kernel. By dynamically weighting residuals during iterative optimization, the GM kernel ensures stable convergence even in the presence of substantial spatial perturbations, thereby preserving alignment accuracy under challenging acquisition conditions.

To evaluate robustness against color inconsistencies, random spectral perturbations are applied to the RGB channels using varying coefficients ( = 0.15∼1.0), simulating a range of lighting conditions from normal daylight to extreme scenarios. Across all perturbation levels, HARO exhibits remarkably stable performance, with rotational errors confined to 0.1285°∼0.1315° and translational errors below 0.008 m. This stability is attributed to two complementary design choices: (1) the use of the hue channel, which inherently reduces sensitivity to variations in illumination intensity, and (2) histogram equalization, which enforces global consistency of color distributions and strengthens the robustness of photometric correspondences during optimization.

In summary, these results confirm that HARO achieves both stable and accurate registration under high-magnitude geometric perturbations and severe illumination changes. The consistent performance across spatial and photometric disturbances highlights the effectiveness of the hybrid adaptive residual design in suppressing multi-source errors. This robustness is particularly critical for large-scale real-world scenarios, where point cloud noise and inconsistent color cues are inevitable, and ensures reliable, precise, and repeatable fine registration, which is necessary.

5. Conclusions

The HARO framework proposed in this paper effectively addresses the key challenges of illumination variation, geometric symmetry, and structural complexity in large-scale color point cloud registration through HSV-based hue correction and kernel-driven adaptive residual optimization. Experimental results demonstrate that HARO achieves sub-degree rotational accuracy and decimeter-level translational precision across diverse complex scenarios, while maintaining strong robustness against noise, low overlap, and lighting interference. The practical significance of this work lies in its provision of a reliable large-scale point cloud registration solution for applications such as urban modeling, autonomous driving, and cultural heritage preservation. In contrast to learning-based methods that require extensive labeled data, HARO adapts to varied scenarios without training. Compared with conventional feature-based approaches, its explicit decoupling of luminance and hue enables more stable handling of repetitive structures and illumination changes, advancing the practical deployment of learning-free registration in large-scale built environments. In summary, HARO offers an effective and robust framework for high-precision registration of large-scale color point clouds. Future work will focus on integrating learned features to improve performance in highly repetitive scenes and optimizing the algorithm toward real-time deployment.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Yangmin Xie; methodology, Yangmin Xie; software, Yangmin Xie, Jinghan Zhang and Rijian Xu; validation, Yangmin Xie, and Hang Shi; formal analysis, Yangmin Xie and Jinghan Zhang; investigation, Yangmin Xie and Jinghan Zhang; data curation, Yangmin Xie, Jinghan Zhang and Rijian Xu; writing—original draft preparation, Yangmin Xie and Jinghan Zhang; writing—review and editing, Jinghan Zhang; visualization, Jinghan Zhang and Rijian Xu; supervision, Yangmin Xie; project administration, Hang Shi. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

All the data has been open-sourced in site: https://github.com/RSAMRG-SHU/HARO_dataset.git (accessed on 29 December 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Ge, X.; Wu, C.; Chen, M.; Xu, B.; Zhu, Q.; Hu, H. Texture-Semantic Point: Registration for Point Clouds of Porcelain Relics. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2025, 91, 347–360. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lv, C.; Lin, W.; Zhao, B. KSS-ICP: Point cloud registration based on Kendall shape space. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2023, 32, 1681–1693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Pang, C.; Zhou, L.; Huang, X. A low-cost 3D SLAM system integration of autonomous exploration based on fast-ICP enhanced LiDAR-inertial odometry. Remote Sens. 2024, 16, 1979. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, C.; Wang, Y.; Deng, Y.; Li, H.; Zhou, R.; Guo, J. Efficient vehicle-infrastructure collaborative perception based on vehicle re-identification and mini-ICP algorithm. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2024, 25, 6580–6593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, C.; Yu, L.; Jia, H.; Huang, Y.; Wang, X.; Lu, Y.; Gao, R.; Jin, H. Research on Path Smoothing Method for Robot Scanning Measurement Based on Multiple Curves. Actuators 2025, 14, 135. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, L.; Wang, S.; Hu, Q.; Cai, Q.; Li, M.; Bai, Y.; Wu, K.; Xiang, B. Gfoicp: Geometric feature optimized iterative closest point for 3-d point cloud registration. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2023, 61, 1–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vizzo, I.; Guadagnino, T.; Mersch, B.; Wiesmann, L.; Behley, J.; Stachniss, C. Kiss-icp: In defense of point-to-point icp–simple, accurate, and robust registration if done the right way. IEEE Robot. Autom. Lett. 2023, 8, 1029–1036. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; Chen, X.; Cai, H.; Wang, Y.; Liang, H.; Li, H. Color point cloud registration algorithm based on hue. Appl. Sci. 2021, 11, 5431. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhong, S.; Guo, M.; Lv, R.; Chen, J.; Xie, Z.; Liu, Z. A robust rigid registration framework of 3D indoor scene point clouds based on RGB-D information. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4755. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, J.; Zhou, Q.Y.; Koltun, V. Colored point cloud registration revisited. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 143–152. [Google Scholar]

- Gu, X.; Wang, X.; Guo, Y. A review of research on point cloud registration methods. IOP Conf. Ser. Mater. Sci. Eng. 2020, 782, 022070. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Wang, J.; Liang, Z.; Su, L. Tree point clouds registration using an improved ICP algorithm based on kd-tree. In Proceedings of the 2016 IEEE International Geoscience and Remote Sensing Symposium (IGARSS), Beijing, China, 10–15 July 2016; pp. 4545–4548. [Google Scholar]

- Quan, S.; Yang, J. Compatibility-guided sampling consensus for 3-d point cloud registration. IEEE Trans. Geosci. Remote Sens. 2020, 58, 7380–7392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tao, W.; Xu, D.; Chen, X.; Tan, G. A Powerful Correspondence Selection Method for Point Cloud Registration Based on Machine Learning. Photogramm. Eng. Remote Sens. 2023, 89, 703–712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, Z.; Meng, F.; Wang, Z.; Gao, Y.; Dai, Y.; Xing, X.; Lin, J.; Guo, Z. Globally Spatial Consistency-Based Maximum Consensus for Efficient Point Cloud Registration. Photogramm. Rec. 2025, 40, e70023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Z. Iterative point matching for registration of free-form curves and surfaces. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 1994, 13, 119–152. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chetverikov, D.; Stepanov, D.; Krsek, P. Robust Euclidean alignment of 3D point sets: The trimmed iterative closest point algorithm. Image Vis. Comput. 2005, 23, 299–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Segal, A.; Haehnel, D.; Thrun, S. Generalized-icp. In Proceedings of the Robotics: Science and Systems, Seattle, WA, USA, 28 June–1 July 2009; Volume 2, p. 435. [Google Scholar]

- Mavridis, P.; Andreadis, A.; Papaioannou, G. Efficient sparse icp. Comput. Aided Geom. Des. 2015, 35, 16–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Yao, Y.; Deng, B. Fast and robust iterative closest point. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 44, 3450–3466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fitzgibbon, A.W. Robust registration of 2D and 3D point sets. Image Vis. Comput. 2003, 21, 1145–1153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pavlov, A.L.; Ovchinnikov, G.W.; Derbyshev, D.Y.; Tsetserukou, D.; Oseledets, I.V. AA-ICP: Iterative closest point with Anderson acceleration. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Brisbane, Australia, 21–25 May 2018; pp. 3407–3412. [Google Scholar]

- Rusinkiewicz, S. A symmetric objective function for ICP. ACM Trans. Graph. (TOG) 2019, 38, 85. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Low, K.L. Linear Least-Squares Optimization for Point-to-Plane Icp Surface Registration; University of North Carolina: Chapel Hill, NC, USA, 2004; Volume 4, pp. 1–3. [Google Scholar]

- Serafin, J.; Grisetti, G. NICP: Dense normal based point cloud registration. In Proceedings of the 2015 IEEE/RSJ International Conference on Intelligent Robots and Systems (IROS), Hamburg, Germany, 28 September–2 October 2015; pp. 742–749. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, J.; Li, H.; Campbell, D.; Jia, Y. Go-ICP: A Globally Optimal Solution to 3D ICP Point-Set Registration. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2016, 38, 2241–2254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, W.; Yang, Y.; Fan, D.; Chen, Z.; Kou, Q. Registration of color point cloud by combining with color moments information. In Proceedings of the 2018 IEEE International Conference on Systems, Man, and Cybernetics (SMC), Miyazaki, Japan, 7–10 October 2018; pp. 2102–2108. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, T.; Du, S.; Xu, Y.; Xu, G.; Li, Z.; Chen, B.; Gao, Y. RGB-D point cloud registration via infrared and color camera. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2019, 78, 33223–33246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, H.; Lilienthal, A.J.; Andreasson, H.; Kurtser, P. NDT-6D for color registration in agri-robotic applications. J. Field Robot. 2023, 40, 1603–1619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wan, T.; Du, S.; Cui, W.; Yao, R.; Ge, Y.; Li, C.; Gao, Y.; Zheng, N. RGB-D point cloud registration based on salient object detection. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 33, 3547–3559. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Men, H.; Gebre, B.; Pochiraju, K. Color point cloud registration with 4D ICP algorithm. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation, Shanghai, China, 9–13 May 2011; pp. 1511–1516. [Google Scholar]

- Korn, M.; Holzkothen, M.; Pauli, J. Color supported generalized-ICP. In Proceedings of the 2014 International Conference on Computer Vision Theory and Applications (VISAPP), Lisbon, Portugal, 5–8 January 2014; Volume 3, pp. 592–599. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, O.; Park, M.G.; Hwang, Y. Iterative K-closest point algorithms for colored point cloud registration. Sensors 2020, 20, 5331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D.; Hong, D.; Wang, S.; Chen, Y. Genetic algorithm-based optimization for color point cloud registration. Front. Bioeng. Biotechnol. 2022, 10, 923736. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Malkov, Y.A.; Yashunin, D.A. Efficient and Robust Approximate Nearest Neighbor Search Using Hierarchical Navigable Small World Graphs. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2020, 42, 824–836. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, Y.; Babu, P.; Palomar, D.P. Majorization-minimization algorithms in signal processing, communications, and machine learning. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2016, 65, 794–816. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toth, A.; Kelley, C.T. Convergence analysis for Anderson acceleration. SIAM J. Numer. Anal. 2015, 53, 805–819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, Z.; Liang, F.; Yang, B.; Xu, Y.; Zang, Y.; Li, J.; Wang, Y.; Dai, W.; Fan, H.; Hyyppä, J.; et al. Registration of large-scale terrestrial laser scanner point clouds: A review and benchmark. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2020, 163, 327–342. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hackel, T.; Savinov, N.; Ladicky, L.; Wegner, J.D.; Schindler, K.; Pollefeys, M. SEMANTIC3D.NET: A new large-scale point cloud classification benchmark. In Proceedings of the ISPRS Annals of the Photogrammetry, Remote Sensing and Spatial Information Sciences, Hannover, Germany, 6–9 June 2017; Volume IV-1/W1, pp. 91–98. [Google Scholar]

- Dong, Z.; Yang, B.; Liang, F.; Huang, R.; Scherer, S. Hierarchical registration of unordered TLS point clouds based on binary shape context descriptor. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2018, 144, 61–79. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Theiler, P.W.; Wegner, J.D.; Schindler, K. Keypoint-based 4-points congruent sets–automated marker-less registration of laser scans. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2014, 96, 149–163. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Besl, P.J.; McKay, N.D. Method for registration of 3-D shapes. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1992, 14, 239–256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.; Zhang, Y.; Qu, C.; Tan, Z. Fast and robust motion averaging via angle constraints of multi-view range scans. J. Eng. 2021, 2021, 104–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jost, T.; Hügli, H. Fast ICP algorithms for shape registration. In Pattern Recognition: 24th DAGM Symposium, Zurich, Switzerland, September 16–18, 2002, Proceedings; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2002; pp. 91–99. [Google Scholar]

- Bouaziz, S.; Tagliasacchi, A.; Pauly, M. Sparse iterative closest point. Comput. Graph. Forum 2013, 32, 113–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tuna, T.; Nubert, J.; Nava, Y.; Khattak, S.; Hutter, M. X-icp: Localizability-aware lidar registration for robust localization in extreme environments. IEEE Trans. Robot. 2023, 40, 452–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lijun, Z.; Yunhan, G.; Xiaofan, Z.; Hang, S.; Yangmin, X. Colorized 3D reconstruction technology integrating multi-source and multi-view data. Bull. Surv. Mapp. 2025, 11, 62–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.