1. Introduction

Localization of unmanned aerial vehicles (UAVs) in environments such as indoor spaces, urban canyons, and tunnels poses a major challenge due to the unavailability or unreliability of global navigation satellite systems (GNSS) [

1]. In these settings, precise positioning is essential to ensure safe navigation and autonomous flight, motivating the development of alternative localization methods. Consequently, a wide range of technologies and approaches have been proposed to address GNSS-denied positioning scenarios [

2,

3]. However, directly applying general indoor positioning solutions to UAV platforms remains nontrivial, as UAV operation is characterized by full three-dimensional mobility, highly time-varying signal propagation (dynamic channel conditions), and stringent size, weight, and power (SWaP) constraints. These factors introduce distinct technical challenges that require focused investigation and tailored localization frameworks [

4].

Indoor localization systems rely on technologies such as 5G, Ultra-Wideband (UWB), Wi-Fi, Bluetooth, and ZigBee. UWB has been widely adopted for indoor UAV localization by deploying fixed anchors that provide range or time-of-flight measurements to estimate the UAV’s position with high accuracy. While UWB can offer high-precision positioning, it has significant drawbacks, such as the need for dedicated infrastructure, higher power consumption, and increased cost, which can limit its deployment in large-scale or budget-constrained scenarios. For UAVs, the requirement for a pre-calibrated, fixed UWB anchor network severely limits operational flexibility and scalability in large or temporary deployment zones, despite its demonstrated effectiveness for indoor aerial robot localization [

5,

6].

Wi-Fi-based localization has been explored for indoor UAV positioning primarily through fingerprinting approaches that match the received signal strength or channel characteristics to pre-collected radio maps [

7]. While this approach can leverage existing network infrastructure and is therefore cost-effective, its positioning accuracy is often degraded by multipath propagation and temporal signal fluctuations, especially in dynamic indoor environments [

8]. Similarly, Bluetooth-based localization has been investigated for UAVs using BLE beacon deployments, where proximity or fingerprinting techniques are applied to estimate position. However, the short communication range and susceptibility to signal interference and reflection limit its achievable accuracy, particularly for precise 3D UAV navigation [

9].

ZigBee, known for low power consumption and suitability for mesh networks, has also been used for UAV indoor localization [

10]; however, its limited range and low positioning precision make it less suitable for high-accuracy UAV localization applications. These limitations are amplified for UAVs, which operate not only along a floor plane but throughout a volumetric space where radio propagation varies rapidly with altitude and motion, leading to frequent non-line-of-sight (NLOS) conditions and stronger multipath effects. Therefore, selecting an appropriate technology for indoor UAV localization must jointly consider infrastructure requirements, scalability, and robustness under 3D mobility and time-varying propagation conditions [

2,

11,

12,

13,

14,

15].

Using 5G new radio (NR) signals for indoor positioning takes advantage of the advanced features of 5G networks, such as high-frequency millimeter-wave (mmWave) signals, large bandwidth, and low latency [

12], to achieve accurate and reliable localization in GNSS challenging environments. The dense deployment of small cells supported by 5G technology provides numerous reference points, enhancing positioning accuracy [

16]. Furthermore, the higher frequency bands of 5G allow for finer spatial resolution [

17], which is particularly useful for distinguishing between closely spaced receivers in an indoor environment. For UAVs, the potential to leverage existing or future 5G communication infrastructure for dual-purpose positioning is a significant advantage, potentially reducing the need for dedicated sensors. The three primary methods for indoor positioning using 5G signals are triangulation, which determines location based on angles; multilateration, which uses time differences of signal arrival; and fingerprint-based methods, which match pre-collected signal characteristics to estimate a device’s position.

Techniques like triangulation, including angle of departure (AoD) and angle of arrival (AoA), and multilateration methods, such as time-difference-of-arrival (TDoA) and time-of-arrival (ToA), can face significant challenges in indoor environments [

18,

19]. The suboptimal performance of these methods indoors is primarily due to factors, such as signal obstruction caused by walls, furniture, and other obstacles, which can block or distort the signals. Additionally, these techniques often require precise hardware synchronization across multiple nodes, which can be difficult to achieve in practice [

20]. Complications also arise from multipath effects, where signals reflect off surfaces and reach the receiver multiple times, as well as from non-line-of-sight (NLOS) conditions, where no direct path exists between the transmitter and receiver [

21]. In UAV applications, these challenges are exacerbated. The UAV’s movement through 3D space creates rapidly changing and often severe NLOS and multipath conditions, especially relative to ceiling-mounted or elevated infrastructure. Maintaining synchronization with a fast-moving aerial node adds another layer of complexity. These challenges can result in inaccuracies when calculating distances or angles, diminishing the reliability of these methods for indoor localization [

22], particularly for high-precision UAV navigation [

19].

Fingerprint-based localization techniques offer a viable solution for indoor positioning, addressing the challenges posed by NLOS [

23,

24,

25]. These methods utilize a pre-existing database comprising actual location coordinates and either channel state information (CSI) or received signal strength indicator (RSSI) readings. Location estimation is achieved by matching the measured RSSI or CSI values against this database. Despite its utility, RSSI-based localization tends to underperform compared to CSI-based approaches due to inherent limitations [

26]. RSSI, derived from radio frequency signals at a packet level, presents difficulties in obtaining precise measurements. In standard indoor settings, the variance of RSSIs recorded from a stationary receiver over a one-minute period can reach up to 5 dB, highlighting the challenge of achieving consistent and accurate readings [

26]. Furthermore, RSSI is susceptible to the multipath effect, causing fluctuations in signal strength, which compromises its effectiveness for precise localization. Conversely, CSI offers a detailed perspective on the signal’s condition at the subcarrier level, providing insights into the signal’s behavior, especially concerning its multipath propagation characteristics. This detailed information includes phase and amplitude changes across different subcarriers, enabling a more accurate depiction of the signal environment and thereby improving the accuracy of location estimates [

24,

25,

27]. The robustness of CSI to multipath makes it a particularly attractive candidate for UAV localization in cluttered indoor environments.

Positioning using the CSI feature can be performed either from the transmitter side, such as through the network’s access points (APs), or from the user side, such as with user equipment (UE). When positioning is conducted from the transmitter side, APs are responsible for determining the location of the UE. However, this method comes with several drawbacks. For example, it requires a dense deployment of APs to achieve high accuracy, which is often costly and impractical. Also, precise synchronization between multiple APs is essential for accurate positioning, and even minor synchronization errors can lead to significant inaccuracies.

On the other hand, localizing devices at the UE side benefits from APs transmitting specialized positioning reference signals. These signals allow UEs to calculate CSI, which can improve localization accuracy when data from multiple APs are combined [

28,

29]. A UE-side (UAV-side) approach is often more practical for autonomous UAVs, as it grants the platform direct control over its position estimate. In scenarios where AP networks are synchronized perfectly, the relative phase information derived from the CSI across different APs is crucial for enhancing positioning accuracy. However, when synchronization among APs is suboptimal, the importance of relative phases diminishes, and they may be excluded during the aggregation of multi-AP CSI. Moreover, it is essential to note that the CSI, whether in the time or frequency domain, produced by a UE fundamentally relies on the UE’s ability to synchronize with the signals received from an AP [

30]. This dependency on synchronization highlights a critical challenge in achieving accurate positioning on the UE side. Expanding on the foundational work [

31,

32,

33], recent advancements in indoor positioning have begun to explore the utilization of commercial 5G NR CSI for localization purposes. The paper by [

34] proposes a hybrid indoor positioning model that combines convolutional neural networks (CNNs) with a path-loss model. The model leverages multivariable fingerprints, including signal strength and environmental factors, to improve the accuracy of 2D indoor positioning in complex environments. The authors reported an average positioning error of 1.47 m, achieving a 9.26% accuracy improvement compared to the CNN-only approach [

34]. The method [

30] outperforms those utilizing detailed frequency characteristics from CSI, significantly improving positioning accuracy in indoor environments. By processing frequency-selective CSI, the method achieved an average positioning error of 0.60 m for indoor 2D localization.

Recently, the research in [

35] tackled the challenges associated with 2D indoor positioning using standalone 5G next-generation NodeBs (gNBs). They proposed a fingerprinting approach that leveraged the multi-beam capability of 5G downlink signals. This methodology uses an “Extreme Learning Machine” to reduce dimensionality, enhancing both the accuracy and speed of indoor positioning. In parallel, ref. [

36] introduced the iPos-5G system, which was evaluated in indoor office scenarios using commercial 5G CSI. Their results demonstrated that 94.45% of test samples achieved positioning errors below 4.01 m—corresponding to the 2σ confidence interval—based on a cumulative distribution function (CDF) analysis of localization errors. These findings underscore the practical potential of CSI-based positioning using a single gNB. Building upon these foundations, ref. [

37] further extended the applicability of commercial 5G technologies for robust and scalable indoor positioning solutions. Complementing these findings, ref. [

38] reported that 67% of 2D positioning errors were within 1 m, affirming the growing reliability of such methods. These studies highlight the potential of 5G NR CSI and multi-beam signals for providing precise and effective indoor 2D positioning solutions. However, these methods are not well-suited for UAV applications that involve flight at varying altitudes within an environment. Additionally, most of them have not been evaluated in large-scale indoor spaces, underscoring the need for continued research and innovation in this rapidly evolving field.

In this work, we propose a 3D indoor localization framework for UAVs using commercial 5G millimeter-wave (mmWave) signals. The proposed approach formulates UAV positioning as a CSI-based fingerprinting problem and employs a deep convolutional neural network (DCNN) that relies on CSI amplitude features, enabling robust localization under imperfect synchronization and device-level variability in practical 5G deployments [

39]. The main contributions of this paper are as follows:

We introduce a 5G CSI-based 3D indoor localization system for UAVs, explicitly addressing altitude variation and full 3D mobility in GNSS-denied environments.

We develop a DCNN-based CSI fingerprinting method that exploits amplitude information, avoiding reliance on phase coherence and improving robustness to synchronization mismatches.

We provide a systematic 3D evaluation using a realistic indoor UAV flight scenario, analyzing the impact of gNB count and training-point distribution on localization accuracy.

The remainder of the paper is organized as follows:

Section 2 presents the proposed method,

Section 3 describes the simulation setup,

Section 4 reports the results,

Section 5 discusses the findings, and

Section 6 concludes the paper.

2. Proposed Approach

This study investigated the positioning of UE devices (UAV trajectory) in a transmission environment consisting of multiple gNBs (base stations) where each gNB is a multi-beam antenna and the UE is equipped with a single antenna. The localization process, which determines the position of the UE, is performed directly on the UE side, leveraging the signals received from the surrounding gNBs. The methodology consists of multiple steps, including channel modeling, CSI feature extraction, generating a channel frequency response (CFR) image, and finally, developing, training, and testing the DCNN model. In channel modeling, the channel data are initially denoted in the time domain and then converted into the frequency domain using the Fourier transform (FT). This conversion enables the extraction of CSI, represented by the complex H-matrix, which captures key characteristics of the wireless channel, including amplitude and phase information across different subcarriers and antennas. Relevant CSI features are subsequently extracted from this matrix to effectively characterize the signal propagation environment. These CSI features are then used to construct CFR images, providing a visual representation of the channel’s frequency response over the spatial domain. These images serve as inputs to DCNN architectures, supporting accurate positioning and localization tasks.

2.1. Channel Model

In a typical 5G network, a gNB is responsible for managing radio communications with UEs within its designated service area, known as a cell. Each gNB is equipped with M antennas to facilitate communication. The position of a UE, denoted as u, is defined by , where D can be either 3 or 2, indicating three-dimensional or two-dimensional space. Similarly, the position of a gNB, represented as t, is given by . It is taken for granted that the UE is in sync with one gNB, without considering the need for synchronization at the network level across the gNBs.

The channel, donated as c, between a gNB and a UE is modeled as comprising P multipath components, where each component is characterized by a complex path gain and a propagation delay . Here, represents the amplitude attenuation and phase shift experienced by the signal along the p-th path, while denotes the time delay of the p-th multipath component, with being the maximum delay spread.

The continuous-time baseband CIR between the UE and a single antenna of the gNB, accounting for these multipath components, is given by [

30]:

where

represents the CIR, which describes the channel’s response to an impulse at the time

, capturing the effects of all multipath components, and

represents the complex gain of the p-th multipath component. The summation is over all P multipath components, where each term

models the contribution of the p-th path. The Dirac delta function

represents an impulse arriving at the receiver with a delay of

. This model effectively captures the impact of multipath propagation in wireless communication, where the transmitted signal reaches the receiver through multiple paths, each with its distinct gain and delay. In contexts involving the Dirac delta function, the CFR is derived from the CIR by transforming it from the time domain to the frequency domain. This transformation is performed using the FT, which allows us to analyze how the different frequency components of a signal are affected by the channel. The CFR is denoted as:

It is assumed that 64 quadrature amplitude modulation (QAM) is used in the creation and decoding of signals within orthogonal frequency division multiplexing (OFDM). In this setup, the gNB transmits pilot signals to the UE across N evenly spaced subcarriers, where N represents the total number of subcarriers, and each subcarrier has a spacing of Δf. These subcarriers are indexed by:

where n represents the subcarrier index. Given

as the carrier frequency, each subcarrier n has a center frequency defined as:

The vector

which represents the subcarrier channels, is obtained by applying the discrete Fourier transform (DFT) to the discrete-time tapped delay line (TDL) channel model. This TDL channel comprises P delay taps, where each tap corresponds to a different multipath component with a specific delay. To perform the DFT, the discrete-time channel c is extended to length N by appending zeros, ensuring it is compatible with the DFT operation. The resulting channel response at the subcarrier frequency given

by:

where

represents the complex gain of the p-th multipath component, and

accounts for the phase shift due to the delay at the subcarrier frequency

. This transformation from the time domain to the frequency domain enables the analysis of each subcarrier’s response to the transmitted signal, which is crucial for estimating the CSI in wireless communication systems to ensure reliable data transmission.

In this model, the CFR captures how the multipath propagation environment affects each subcarrier’s signal, considering the impact of different path gains and delays. The use of 64-QAM modulation allows for efficient transmission by mapping data onto multiple amplitude and phase states, while the OFDM scheme divides the transmitted signal into multiple subcarriers, each carrying a portion of the data. By leveraging the pilot signals across these subcarriers, the UE can accurately estimate the channel conditions, facilitating reliable decoding of the transmitted information.

Given hardware constraints and synchronization errors, CSI measurements experience various distortions related to timing, phase, and magnitude [

30]. The elements of the estimated CSI vector

are modeled as:

where

is the phase distortion caused by synchronization errors and other impairments, and

represents the estimation noise, assumed to be Gaussian and white, which includes interference effects from carrier frequency offset, in-phase/quadrature (I/Q) imbalance, and phase noise. The term

captures the frequency component at subcarrier n,

represents the scaling factor for frequency offset, and

denotes additional phase noise. Due to the phase distortions affecting the estimation of the CFR, the CSI cannot be directly used as a feature for localization [

30,

40,

41,

42].

2.2. CSI Feature

CSI captures extensive channel characteristics, providing rich scene information, and is highly sensitive to environmental changes. This means that both the movement of people and objects in the scene can cause numerical fluctuations in CSI value [

43]. In modern communication systems that utilize multi-beam antenna arrays, CSI provides detailed measurements of the signal attenuation and phase shifts along each propagation path between the transmitter and receiver. These characteristics are typically represented as the CIR in the time domain and the CFR in the frequency domain.

In 5G mmWave multi-beam systems, CSI is represented through a beam-space H-matrix that captures the complex channel responses from each directional beam, following the framework established in [

44]. Our system employs twelve horn antennas, each transmitting two orthogonally steered beams (X- and

Y-axis) as described in

Section 3.2, received by a single antenna [

45]. The H-matrix is constructed through sequential pilot transmissions using time-division scheduling, where each beam’s contribution is isolated and estimated via least-squares methods similar to [

46]. The resulting matrix provides complete channel characterization while leveraging the directional advantages of horn antennas for enhanced signal quality and spatial resolution. This beam-space representation serves as the foundation for precise localization in our system. Once the per-antenna responses are obtained, they are assembled to reconstruct the full H-matrix, representing the channel state at a given time-frequency resource. Based on these estimated responses, the H-matrix can be formally expressed as:

where

is the received signal,

is the transmitted signal, N is noise, and

is the H-matrix in the frequency domain, containing both amplitude and phase information [

47,

48]. The indices a and u correspond to the transmitting antenna and receiving user, respectively. This can be represented by the following equation:

where

and

represent the amplitude and phase response, respectively [

39]. The amplitude of CSI serves as a unique identifier for indoor positioning in 5G mmWave environments. It fluctuates based on individual movements, affecting signal reception. While the phase offers more detail, it is cyclic and requires calibration. Also, due to fading and frequency deviations, the phase is more susceptible to noise [

24]. This study focuses exclusively on the amplitude aspect of CSI, using a setup with 12 multi-beam antennas.

2.3. CFR Image

CFR images are visual representations created by mapping H-matrix amplitude data into a matrix format, where each pixel represents a specific amplitude measurement at a particular point and transmit antenna. This visual representation captures unique patterns and features associated with different locations while maintaining relative stability for CFR at the same location, making it a valuable tool for enhancing positioning accuracy [

39]. By comparing CFR images obtained during the testing phase with those stored in the database from the training phase, the system can accurately determine the position of a device or object within an environment.

The H-matrix represents the amplitude of CFR (Equation (9)), where measurements from the S subcarrier are collected at R distinct receiver locations (i.e., sampling points in space). These measurements form an R × S matrix, which is then used to generate the CFR images that serve as input to the positioning system. By leveraging these images, the model can effectively learn spatial signal patterns and estimate the receiver’s location with high accuracy.

In this context,

denotes the CFR amplitude value from the S-th subcarrier in the R-th point. Inspired by the successful use of dictionary learning techniques in image classification, we adopted a similar approach to visualize H-matrix data. To improve the clarity of these visual representations, we first standardized the data by calculating the mean amplitude at each point across all images.

Subsequently, the standardized CSI image is created.

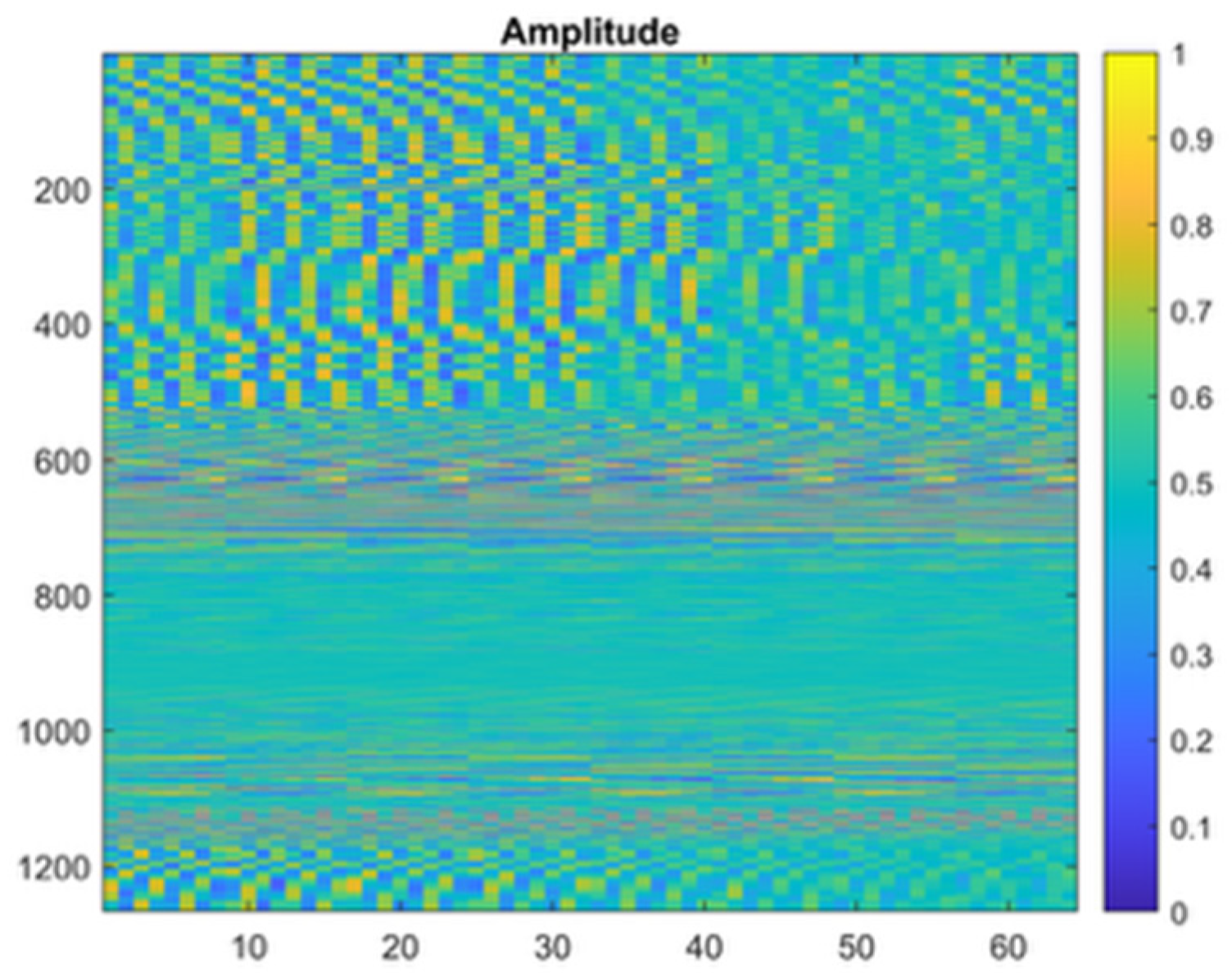

In a multi-beam system, the observations of high-dimensional CFRs are condensed into two-dimensional CFR images for every antenna pair involved in transmission and reception. These images form the basis of our dataset construction. In

Figure 1, a sample of the CFR image is shown, where the color gradient, ranging from blue (indicating low amplitudes) to yellow (representing high amplitudes), visualizes the amplitude values. Such representations highlight the channel’s frequency-dependent characteristics, aiding in understanding its behavior for location determination. The generated CFR images are processed by a DCNN model to ascertain positions.

2.4. Positioning Framework

In the context of processing CFR images for estimating UE locations using DCNNs, the process involves several key steps and considerations. These images are then analyzed by a DCNN model to infer the UE’s position. The DCNN model is designed to handle the increased dimensionality and complexity introduced by combining features from various gNBs. This integration not only enhances the accuracy of location predictions but also necessitates careful management of input features to balance performance improvements against increased computational demands. The model’s architecture begins with data preprocessing, including transforming CFR images into a suitable format and normalizing them to optimize training efficiency. Data augmentation techniques, such as noise injection and random rotations are employed to enrich the dataset, thereby making the model’s capability to adapt to new data.

2.4.1. Deep Learning Model

The proposed DCNN model, as shown in

Figure 2, is designed to estimate 3D positions from the amplitude of CSI feature data with high precision. Unlike conventional fingerprint-based localization methods that rely on shallow CNNs or fully connected regressors applied to static RSS or CSI fingerprints, the proposed model explicitly exploits hierarchical spatial–frequency structures embedded in multi-beam CFR feature maps. The architecture is constructed using six residual blocks, each consisting of two convolutional layers followed by batch normalization and Leaky rectified linear unit (ReLU) activation functions. Each block incorporates a shortcut connection that adds the input to the output, forming a residual learning path. This design facilitates improved gradient flow during training, enabling the network to be deeper and more effective at capturing complex spatial patterns without suffering from vanishing gradients. Furthermore, attention mechanisms are integrated after each residual block to adaptively emphasize informative frequency components and antenna-beam correlations, which are typically ignored in baseline fingerprinting approaches. By combining deep residual learning with attention-based feature refinement, the proposed network captures both local and global dependencies within CFR feature maps, enabling more discriminative representations for 3D localization.

The proposed DCNN model is designed to estimate 3D positions from CFR feature maps with high precision. The model receives input in the form of CFR feature images that represent spatial–frequency patterns aggregated from multiple antenna beams. These inputs are processed through a sequence of convolutional (C) and downsampling (D) layers that progressively extract high-level spatial representations while reducing spatial resolution. Each convolutional layer is followed by batch normalization and a Leaky ReLU activation function to enhance feature discrimination and maintain stable gradient propagation during training. In contrast to most of the existing fingerprint-based deep learning models that directly regress location from flattened CSI features, the proposed framework preserves the spatial structure of CFR maps throughout the convolutional pipeline, enabling more robust learning under channel variability. The progressive abstraction of features across network stages allows the model to effectively encode both fine-grained frequency responses and broader spatial patterns. The downsampling layers capture multi-scale features, contributing to improved robustness against positional and channel variations.

To improve the model’s generalization capability, the training data are augmented using several techniques. These include adding zero-mean Gaussian noise (σ = 0.01), flipping the feature patterns, applying random circular shifts (rotations), and scaling the features by a random factor between 0.9 and 1.1. This augmentation emulates moderate receiver-side measurement uncertainty, thereby increasing robustness to signal variability. The testing dataset, in contrast, is generated along continuous UAV trajectories and no additional artificial noise is explicitly injected. Instead, realistic variability is inherently introduced through UAV motion, changing propagation geometry, and time-varying multipath effects captured by the ray-based simulation environment. This design allows the localization performance to be evaluated under physically meaningful channel dynamics while isolating the impact of UAV motion and gNB deployment configurations. This distinction between training-time stochastic augmentation and test-time physics-driven variability differentiates the proposed evaluation framework from prior fingerprinting studies that rely on static or randomly sampled test points. The hierarchical convolution–downsampling architecture inherently enhances resilience to noise and distortion by allowing the model to learn spatially invariant representations.

Following the final convolutional block, the extracted features are flattened and passed to fully connected layers that map the learned high-level representations to the final 3D coordinate output. Unlike single-head regression architectures commonly used in fingerprint-based localization, the proposed network employs three parallel fully connected branches to independently estimate the x-, y-, and z-coordinates, enabling axis-specific feature refinement and improved vertical positioning accuracy. This decoupled regression strategy allows the network to better model anisotropic localization characteristics, particularly along the vertical dimension. Dropout (p = 0.5) and Leaky ReLU activations are applied within the fully connected layers to prevent overfitting and ensure stable convergence.

The careful selection and tuning of hyperparameters—including batch size, dropout rate, weight decay, and learning rate—are critical for optimizing model performance. The training process uses the RAdam optimizer [

49] with an initial (base) learning rate of 3 × 10

−4, which provides a stable starting point for convergence. A batch size of 64 was selected to balance computational efficiency and memory usage, while a weight decay of 1 × 10

−5 was applied as a regularization mechanism to mitigate overfitting by penalizing large weights. To further improve convergence and generalization, the training employs the OneCycleLR learning rate scheduler [

50]. Under this scheme, the learning rate is warm-started from the base value of 3 × 10

−4, increased to a maximum value of 1 × 10

−2 during the initial phase of training, and then gradually decreased following a cyclic schedule for the remainder of the training process. This strategy enables the model to efficiently explore the loss landscape, avoid suboptimal local minima, and achieve stable convergence. Together, these training and optimization strategies ensure high localization accuracy and strong generalization performance across varying signal environments.

2.4.2. Evaluation Metrics

To rigorously assess the efficiency of the proposed indoor positioning technique, both quantitative and qualitative evaluations were conducted to comprehensively demonstrate its accuracy and performance characteristics. The mean positioning error (MPE) was used as a primary metric to quantify the average magnitude of localization errors across all test scenarios. The MPE is defined as [

51]:

where

,

, and

are the predicted values, and

,

, and

are the ground truth for the x, y, and z coordinates of sample i, respectively, and n is the number of samples.

In addition to MPE, the root mean square error (RMSE) is reported to capture the dispersion of localization errors and penalize larger deviations more strongly. RMSE provides complementary insight into the robustness and stability of the positioning performance and is defined as [

52]:

Furthermore, CDFs of the positioning error are presented to illustrate the statistical distribution of localization accuracy and to provide percentile-based performance insights (e.g., median and 90th-percentile errors).

3. Environmental Simulation

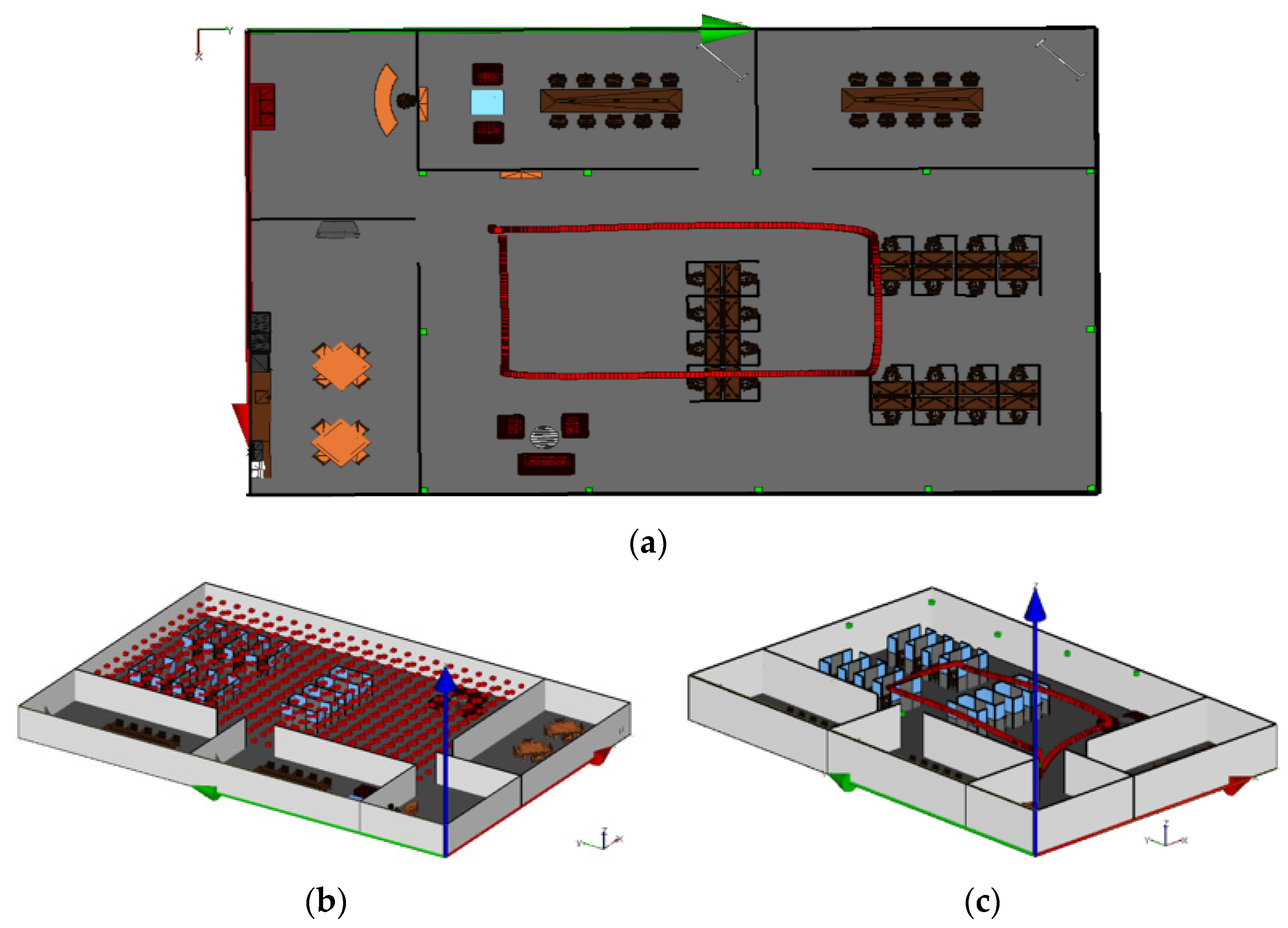

Our environmental simulation involves developing a simulated office environment with dimensions 20 m × 30 m × 3 m for experimentation. Initially, the building was modeled using Wireless InSite software [

53] and customized to imitate a real-world environment. The resulting layout is shown in

Figure 3a. Within this structure, twelve transmitters (TXs), represented by green cubes, were strategically positioned at heights ranging from 1.7 m to 2.8 m above the floor. To train the DCNN model, three horizontal plates of receivers (RXs), represented by red cubes, were positioned at heights of 0.15 m, 1.5 m, and 2.5 m above the floor, as depicted in

Figure 3b. These receivers were arranged with different spacing intervals between them across three separate scenarios: 0.25 m in the first, 0.5 m in the second, and 1 m in the third. If a nominal receiver (fingerprint) location overlaps with or is occluded by furniture or other indoor objects, it is shifted to the nearest collision-free position to ensure physically feasible UAV placement. Each scenario was tested independently, including the UAV flight trajectory shown in

Figure 3c. Detailed descriptions of both TX and RX antennas are provided in

Section 3.2. Furthermore, the study evaluated the influence of various building materials on wave propagation using a 28 GHz frequency band. This multifaceted approach ensures a comprehensive analysis of how these materials affect signal behavior within the simulated environment.

To collect testing data, an indoor office environment—consistent with the simulated building modeled in Wireless InSite—was recreated using the Gazebo software package (version 11) [

54]. A UAV equipped with multiple onboard sensors was simulated to fly along a predefined trajectory within this environment. The simulated UAV was modeled as an X500-class quadrotor [

55], whose physical dimensions and geometry closely match those of commonly used real-world platforms, ensuring realistic size, mass distribution, and flight characteristics. The UAV motion was designed to emulate practical indoor flight behavior, including full three-dimensional movement and variable velocities, thereby capturing realistic UAV dynamics. The ground-truth UAV trajectory was extracted directly from the Gazebo simulation and subsequently used to place the testing receivers within the Wireless InSite environment, ensuring that the receiver configuration accurately reflected a real UAV flight path. The simulated trajectory was sampled at a rate of 30 Hz over a duration of 38.7 s, resulting in 1161 receiver locations, as illustrated in

Figure 3a,c. For improved visualization clarity, the ceiling of the simulated environment is hidden in

Figure 3.

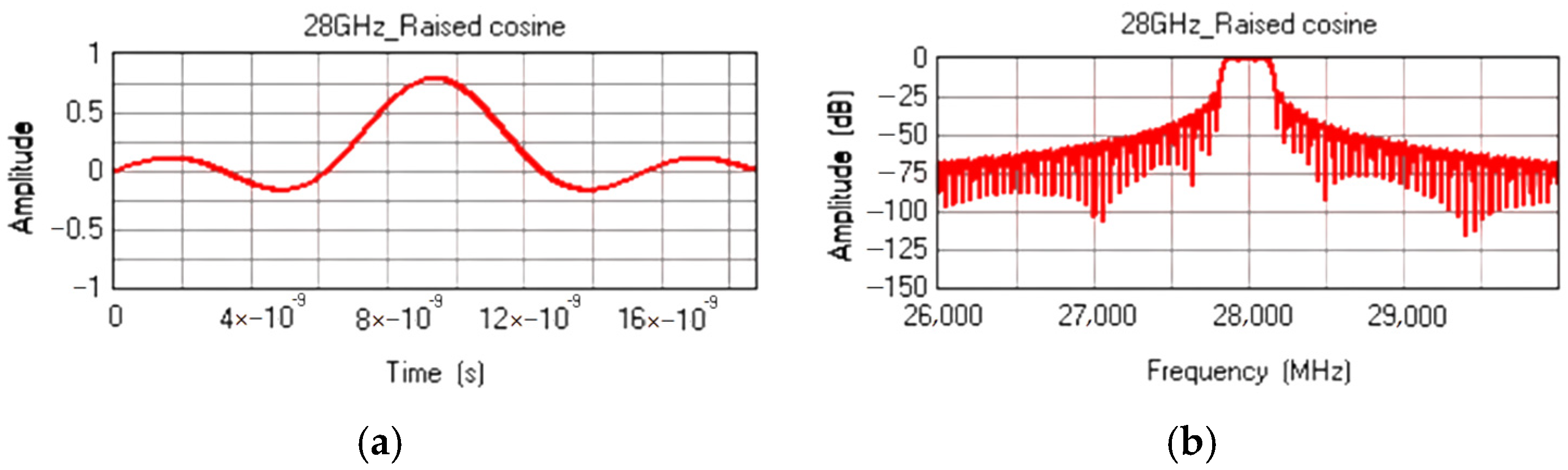

3.1. Waveform Simulation

In Wireless InSite, waveforms define the time and frequency characteristics of the signal transmitted by the antenna, as illustrated in

Figure 4, enabling users to configure parameters that influence the signal’s behavior during propagation. The 28 GHz band is widely used for 5G mmWave simulations due to its practical benefits, including the availability of large bandwidths that support high data rates and its suitability for indoor environments. This band allows for enhanced spectrum reuse through smaller cell sizes, supports advanced antenna technologies, such as multi-beam, and facilitates low-latency communication essential for real-time applications. Additionally, the 28 GHz band is allocated for 5G use in many countries, supported by industry adoption and regulatory frameworks [

56].

In our 5G mmWave simulation for indoor positioning, we used 28 GHz signals with a 100 MHz bandwidth and employed a raised cosine waveform, as suggested in [

57,

58], due to its performance enhancements. This approach reduced the peak-to-average power ratio, minimized out-of-band emissions, and improved bit error rate performance, ensuring precise localization and reliable real-time indoor positioning with reduced latency.

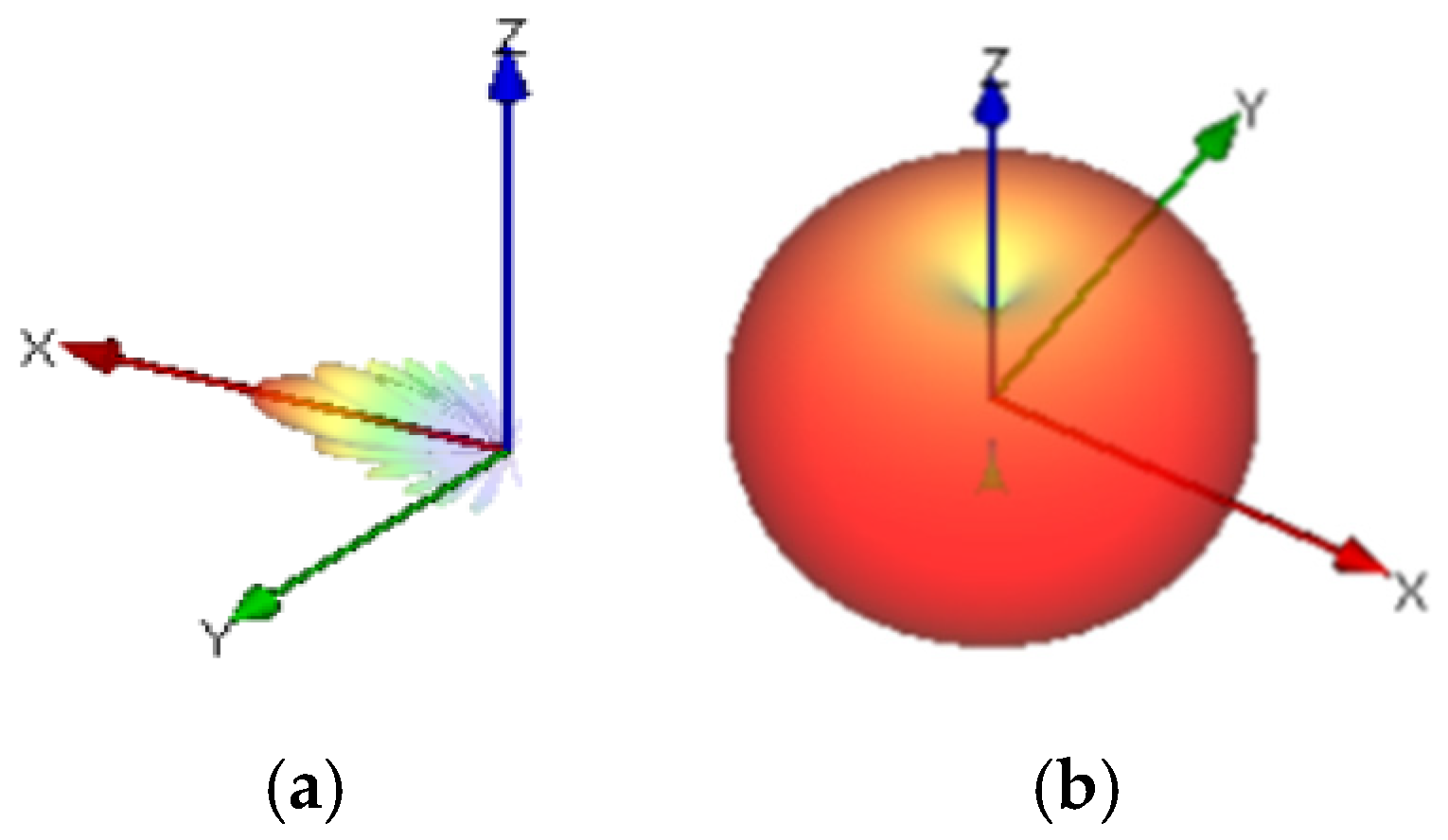

3.2. Antenna Design

The multi-beam transmitter, developed for high-precision 3D localization, consists of 12 horn antennas mounted at varying heights between 1.7 and 2.8 m above the ground. As illustrated in

Figure 5a, the system generates two distinct narrow beams: one oriented in the X–Z plane and another in the Y–Z plane, enabling directional coverage along both horizontal axes and enhancing the spatial resolution of CSI-based positioning. Horn antennas were selected for their ability to provide focused, directional beams, which help enhance signal strength and spatial resolution and are crucial for extracting detailed CSI features. The receiver antenna was omnidirectional, as shown in

Figure 5b, allowing it to capture signals from all directions and ensure comprehensive coverage of the indoor environment [

59]. This combination of horn and omnidirectional antennas enhances the collection and analysis of CSI features for 5G mmWave indoor positioning by leveraging the directional properties of the horn antenna to focus on specific areas and the broader coverage of the omnidirectional antenna for wider signal reception. This complimentary setup improves the quality and diversity of the captured data, as detailed in

Table 1, allowing for more comprehensive and accurate signal analysis.

3.3. Material Properties

The electrical properties of the selected materials were analyzed and are summarized in

Table 2. The real part of the relative permittivity Re (

), representing the material’s capacity to store electrical energy in an electric field, and the conductivity σ, which reflects the material’s ability to conduct electric current, were determined using a curve-fitting method. This process was complemented by simple expressions detailed in [

59,

60]. Understanding these properties is crucial for predicting how materials will behave at specific frequencies, which is essential for applications in telecommunications and materials science.

4. Results

This section presents the research results, along with an analysis and evaluation of the effectiveness of the proposed indoor positioning method. As detailed in

Section 3, the data for the tests were generated from a simulation that accurately recreated a UAV’s flight trajectory within an office environment. The simulation conducted using Gazebo [

54] software, depicted typical indoor drone flights with altitudes ranging from 0.15 m to 2.3 m and lasted for 38.7 s, producing a total of 1161 data points. It should be noted that for each experimental configuration, a separate DCNN model was trained to ensure alignment with the corresponding input data and unbiased performance evaluation.

4.1. Effect of Spacing

To optimize the model’s predictive accuracy and robustness, experiments were conducted under three horizontal reference-point spacing configurations of 0.25 m, 0.5 m, and 1 m. For each spacing configuration, reference points were arranged on three horizontal layers located at heights of 0.15 m, 1.5 m, and 2.5 m above the floor, enabling the evaluation of 3D localization performance across representative indoor operating heights. The lowest horizontal layer at 0.15 m was selected to reflect realistic near-floor device and sensor heights commonly encountered in indoor environments, while avoiding direct floor contact and extreme near-field propagation effects that may distort mmWave fingerprints. The higher layers corresponded to typical operating heights of indoor mobile platforms and user equipment. These configurations were evaluated independently to assess the influence of reference-point spacing and height on the training process and localization performance. The results of this investigation are summarized in

Table 3 and

Figure 6,

Figure 7 and

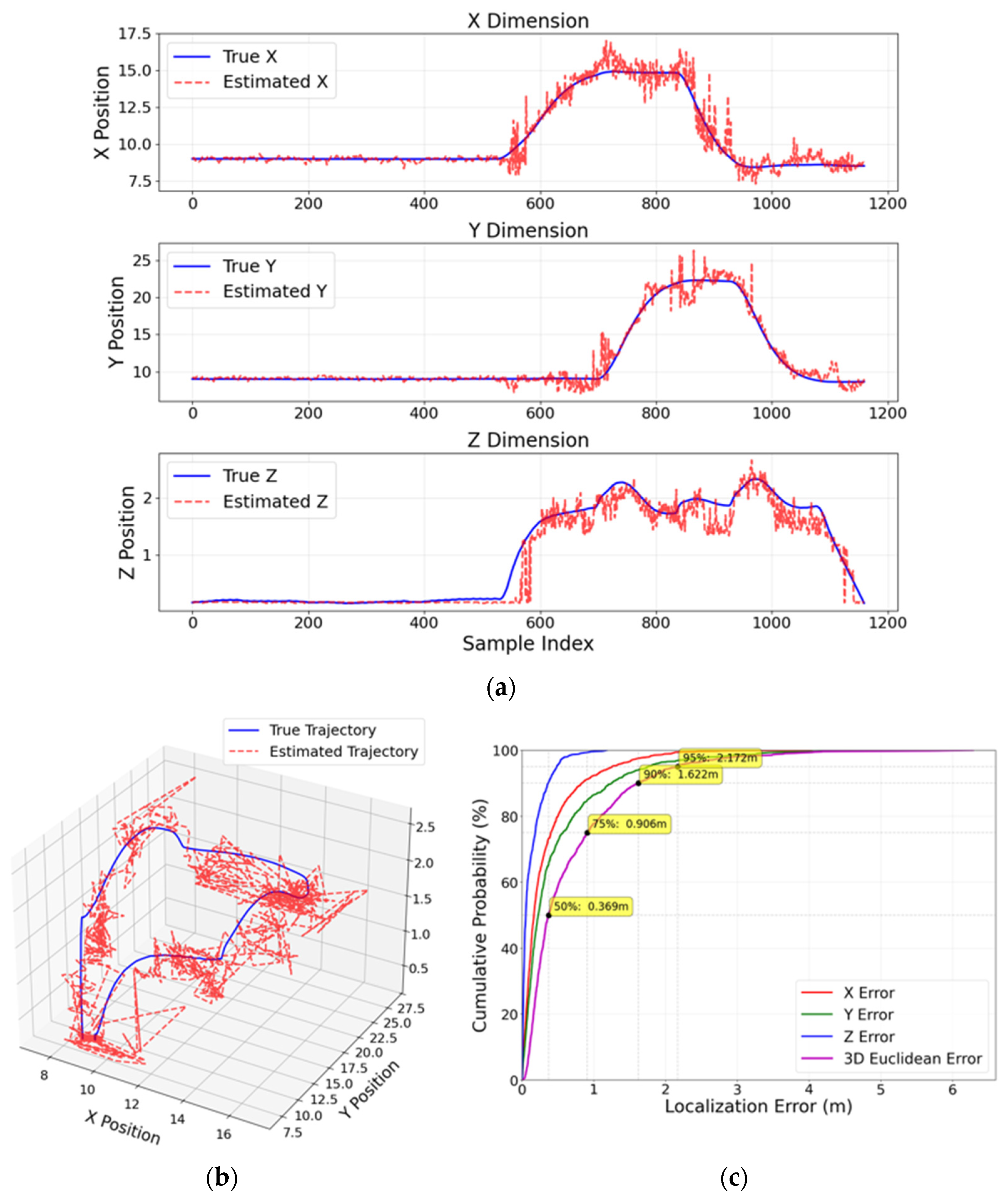

Figure 8. These figures collectively present the localization performance and include the CDFs of the localization errors across all test points, providing a comprehensive view of the error distribution and overall positioning accuracy.

The positioning accuracy of the proposed model was noticeably influenced by the spacing between receivers. As demonstrated in the results, the optimal spacing of 0.25 m yielded the highest accuracy, with MPE values of 0.43 m in 3D and 0.36 m in 2D. This fine spacing allows the model to capture more precise measurements due to the closer proximity of the receivers, resulting in better model training and reduced uncertainty in the estimated positions. As shown in

Figure 6 (1D and 3D plots), the estimated positions closely aligned with the ground truth, with minimal deviation observed across all axes. This alignment underscores the model’s effectiveness in maintaining high accuracy with closer receiver spacing. As the spacing increased to 0.5 m, a noticeable decline in positioning accuracy occurred. The MPE values increased to 0.61 m in 3D and 0.55 m in 2D. Visual analysis of

Figure 7 reveals more significant discrepancies between the estimated and ground truth positions, particularly along the

Z-axis. This decrease in accuracy suggests that the greater spacing between receivers reduces the precision of position estimation. Further deterioration in positioning accuracy was observed at a spacing of 1.0 m, with the highest MPE values recorded, 1.06 m in 3D and 1.01 m in 2D. The visual results presented in

Figure 8 demonstrate a more substantial divergence between the estimated and ground truth positions, not only along the

Z-axis but also across the X- and Y-axes. This significant increase in error indicates that the model struggles to maintain precise localization with larger receiver spacing.

The CDF results underscore the critical impact of receiver spacing on localization accuracy. With a tight spacing of 0.25 m, the 3D Euclidean error exhibited superior performance, with 75% of errors below 0.331 m and a median (50%) error of only 0.188 m. The tail of the distribution was also tightly bounded, with 95% of errors falling under 0.706 m. Expanding the spacing to 0.5 m significantly degraded the precision; the median error nearly doubled to 0.295 m, and the 75th percentile error increased to 0.467 m, while the 95th percentile error escalated to 1.158 m, indicating a broader spread of larger errors. This trend culminated with the poorest performance at a 1.0 m spacing, where the median error jumped to 0.750 m and a substantial 25% of errors exceeded 1.125 m, culminating in a 95th percentile error of 2.498 m. This direct comparison demonstrates that denser receiver configurations yield not only lower average errors but, more importantly, a drastically reduced probability of large localization outliers, which is essential for reliable and safe operation in applications like UAV navigation.

4.2. Effect of Number Training Plate

As outlined in

Section 3, the training dataset was generated by placing horizontal arrays of receiver antennas—referred to here as “training plates”—at three distinct elevation levels, as shown in

Figure 9. These plates were positioned parallel to the ground at fixed heights to capture spatial signal variations at different vertical layers. To evaluate the effect of the number of training plates and their heights, three combinations of these training plates (with 0.5 m RXs spacing) were tested. In each configuration, one of the horizontal plates was omitted in the training process (as shown in

Table 4). The objective was to understand how variations in the number and heights of training data points impact the model’s accuracy and reliability. This analysis aimed to identify the optimal settings for maximizing the effectiveness of the model. The results derived from our simulation of each scenario are summarized in

Table 4 and illustrated in

Figure 10,

Figure 11 and

Figure 12.

When one of the training plates was omitted, the deterioration in positioning accuracy was more pronounced in the Z-axis (vertical positioning) compared to the x–y plane (horizontal positioning). This is because each plate, especially those at different heights, provides crucial information for estimating the vertical position of the receiver. In 3D positioning, removing data from one of these heights led to a significant loss of elevation information, making it more difficult for the model to accurately estimate the Z-axis location. For instance, removing the plate at 0.15 m resulted in the largest increase in 3D positioning error, from 0.61 m to 1.39 m. Moreover, in 2D positioning, the impact of omitting any single plate was less severe, with MPE values ranging from 0.55 to 0.98 m. This indicates that each height contributes to overall positioning performance. Our investigation underlines the importance of incorporating all three training plates to achieve the lowest possible errors in both 3D and 2D positioning, emphasizing that the presence of data from multiple heights, particularly ones close to the UE, is key to optimizing the model’s overall performance.

The CDF analysis of omitting training plates demonstrates a clear sensitivity of the model, particularly at lower elevations. Omitting the highest training plate resulted in a modest performance degradation, increasing the median (50%) 3D error to 0.689 m and the 95th percentile error to 2.943 m. However, omitting a mid-height plate showed a more pronounced effect on the error tail, raising the 95th percentile to 2.236 m. The most severe impact occurred when the lowest plate was omitted, which caused a fundamental failure in the model’s vertical estimation, as evidenced by a drastically higher median error of 1.382 m. This result highlights that training data from the lower height plane, which most closely correspond to a significant portion of the UAV’s operating trajectory, are essential for establishing a robust baseline for 3D localization.

4.3. Effect of Number of Transmitters

In

Section 2, we illustrated the installation of 12 gNBs at varying heights, ranging from 1.5 to 2.5 m above ground level. The strategic variation in antenna height aims to enhance the

Z-axis (vertical) position estimation accuracy. Additionally, we adjusted the network density by gradually reducing the number of active gNBs from 12 to 4, as shown in

Table 5, to assess how network density changes affect the positioning system’s accuracy. The results of these different configurations are presented in

Table 5 and

Figure 13,

Figure 14 and

Figure 15.

This trend suggests that higher network density (with more gNBs) is critical for improving the precision of vertical positioning, while 2D horizontal positioning is less affected by the reduction in gNBs. The visualization of ground truth versus estimated positions also supports this, where discrepancies in the Z-axis were more noticeable when fewer gNBs were used, further emphasizing the importance of maintaining sufficient antenna coverage for accurate 3D localization.

To place the proposed approach in context, a comparative summary of representative 5G-based indoor positioning methods is provided in

Table 6. The table reviews state-of-the-art techniques reported in the literature, highlighting their underlying methodologies, employed 5G signal features, positioning dimensionality (2D or 3D), evaluation type (simulation or real-world), and reported localization accuracy. This comparison emphasizes that most existing studies focus on real-world 2D positioning or simulation-based 3D evaluations, whereas the proposed method was evaluated in both 2D and 3D using real-world measurements.

The effect of reducing the number of active transmitters is evident in the progressive degradation of localization precision. With 12 transmitters, the model achieved robust performance, with a median (50%) 3D error of 0.295 m and 95% of errors below 1.158 m. Reducing the count to 8 transmitters increased the median error to 0.405 m and the 95th percentile to 1.245 m. A further reduction to 6 transmitters showed a continued but less severe decline in median error (0.44 m), but the tail (95th percentile of 1.596 m) remained worse than the 12-transmitter baseline. The most significant performance drop occurred with only 4 transmitters, where the median error rose to 0.369 m and, critically, the 95th percentile error jumped to 2.172 m. This demonstrates that while reducing the transmitter count moderately affects the median accuracy, it disproportionately inflates the occurrence of large, outlier errors, highlighting that a dense network is essential for consistent and reliable positioning, especially for safety-critical operations.

5. Discussion

It is shown that the positioning accuracy of the model is closely tied to the configuration of receiver spacing, the number of active gNBs, and the inclusion of training plates at different heights, demonstrating the complex interplay of factors influencing the model’s performance. The research highlights the importance of receiver spacing in fingerprinting-based positioning methods, where both the distance between the RX antennas and the number of antennas significantly impact accuracy. A spacing of 0.25 m captures distinct signal fingerprints, improving the model’s ability to differentiate between locations. However, reducing the spacing further would increase system complexity and data processing requirements, making it impractical. On the other hand, a spacing of 0.5 m is considered optimal as it balances accuracy with practicality, requiring fewer receivers and generating less data while still achieving reliable positioning. Increasing the spacing beyond 0.5 m led to weaker signals, reduced coverage overlaps, and increased positioning errors. Thus, balancing the number of antennas and their spacing is essential for minimizing errors and maintaining high positioning accuracy in dynamic environments.

The CDF curves provide deeper insight into these error characteristics beyond average metrics such as MPE and RMSE. As shown in the CDF plots, tighter receiver spacing and a higher number of active gNBs consistently shifted the 3D Euclidean error curves to the left, indicating not only lower median errors but also a reduced tail of large localization errors. For instance, configurations with 0.25 m and 0.5 m receiver spacing exhibited steep CDF slopes, where more than 75% of the positioning errors fell below sub-meter levels. This steepness reflects a stable and well-conditioned fingerprint space, where CFR images capture sufficiently distinct spatial–frequency patterns. In contrast, larger receiver spacing or reduced gNB density led to flatter CDF curves with heavier tails, revealing a higher probability of outliers, which is particularly critical for UAV navigation and safety-critical applications.

Additionally, the presence of training plates at multiple heights significantly impacts the model’s ability to estimate vertical positioning (Z-axis) accurately. The exclusion of any plate, especially the one at the lowest height, introduces larger errors in 3D positioning, indicating that data from various elevations are essential for maintaining accuracy in vertical estimates. This is primarily due to the fact that most of the UAV trajectory data are collected while the UAV is on the ground, near the lowest plate. As a result, the height of the horizontal training plates relative to the UAV significantly affects the positioning accuracy, particularly along the vertical axis (Z-axis).

Furthermore, the CDF analysis highlights the sensitivity of vertical (Z-axis) accuracy to both antenna density and the availability of multi-height training plates. When training plates at specific elevations were omitted, the corresponding CDF curves for the 3D Euclidean error shifted noticeably to the right, especially at higher percentiles (90–95%), indicating degraded robustness rather than merely increased mean error. This behavior confirms that CFR images implicitly encode elevation-dependent propagation characteristics, and removing height diversity reduces the model’s ability to generalize vertical positioning.

Moreover, the number of active gNBs strongly influences the model’s performance, particularly on the Z-axis. A gradual reduction in the number of gNBs from 12 to 4 resulted in a sharper increase in 3D positioning error compared to the 2D error. This demonstrates the importance of network density for accurate vertical positioning, as fewer gNBs limit the diversity of signals available for triangulating vertical distances. Similarly, reducing the number of active gNBs disproportionately affects the upper tail of the CDF, demonstrating that network sparsity primarily increases worst-case errors. Our evaluation highlights the importance of maintaining a sufficient number of active gNBs, optimizing receiver spacing, and incorporating comprehensive training data from multiple heights to achieve the desired positioning accuracy in both horizontal and vertical dimensions.

Overall, the CDF-based evaluation confirms that the proposed CFR image representation, combined with sufficient antenna density and elevation-aware training data, yields not only high average accuracy but also reliable and bounded localization performance suitable for onboard UAV deployment.

Our proposed method leverages 5G CSI amplitude data to construct CFR images, a novel representation that exploits rich spatial-frequency information from multiple gNBs together with data from three vertical training plates. This configuration enables high-precision, multi-dimensional localization, achieving a 2D MPE of 0.36 m and a 3D MPE of 0.43 m. A comparison with related methods, summarized in

Table 6, underscores the effectiveness of this approach. While previous works predominantly focused on 2D positioning—often within simulation environments or with reported accuracies exceeding one meter in realistic settings—our method achieves superior precision while solving the more complex 3D problem. This performance is directly attributed to the CFR image representation and the explicit incorporation of multi-height training data, which is especially critical for vertical accuracy and overcomes key limitations of traditional fingerprinting approaches. These results position the proposed method as a state-of-the-art solution for precise 3D positioning in 5G-enabled indoor environments.