Abstract

Recognized as the world’s “Third Pole”, the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau poses significant challenges to human health due to its harsh environment. With improved transportation and a tourism boom industry bringing over 90 million low-altitude residents to the plateau annually, hypoxia has become a critical concern. This study analyzes oxygen content data (2017–2022) together with environmental variables including elevation, temperature, precipitation, and vegetation cover, using the GeoDetector method to identify key drivers of near-surface oxygen distribution. Within the framework of disaster system theory, we evaluated the risk of hypoxia among short-term residents. Results show that the near-surface oxygen distribution across the plateau is primarily regulated by climatic and topographic factors. Interactions among environmental variables markedly enhance the explanatory power for spatial variation in oxygen content, with the coupled effects of humidity, atmospheric pressure, elevation, and temperature being especially pronounced. A high hypoxia hazard prevails across the plateau, particularly in the high-altitude western, northern, and central regions. The spatial distribution of hypoxia risk is strongly shaped by human activities, with high-risk zones clustering in densely populated towns, transportation corridors, and regions of intensive tourism. This results in a distinctive coexistence of “high hazard–low exposure” and “low hazard–high exposure” patterns. These findings provide scientific insights for tourism planning, health protection, and risk management in plateau regions.

1. Introduction

The Qinghai–Xizang Plateau, the world’s highest and largest plateau, is widely regarded as Earth’s “Third Pole” [1]. It functions as a critical ecological security barrier for both China and the world, conferring immense strategic importance [2]. Its natural landscapes are uniquely striking and remain relatively undisturbed by human activity. Renowned worldwide for its distinctive scenery—including snow-capped mountains, glaciers, lakes, and alpine grasslands—the plateau has also fostered the development of the unique and enigmatic Xizang civilization [3]. The plateau ranks among the most inhospitable regions on Earth, where thin air, intense ultraviolet radiation, and scarce, unevenly distributed food resources present severe challenges to human survival [4]. In recent decades, advances in transportation and the rapid expansion of tourism have brought large numbers of short-term visitors to the plateau. Since the beginning of the 21st century, tourist arrivals to the plateau have surged, with annual growth rates exceeding 25%. In 2017 alone, more than 51 million tourists visited the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau [5]. Since 2017, China has undertaken the Second Comprehensive Scientific Expedition to the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau, deploying numerous researchers for field investigations. Statistics indicate that, driven by tourism initiatives, “Aid to Xizang and Qinghai” projects, and scientific expeditions, more than 90 million low-altitude residents from inland China now visit the plateau each year [6]. While these activities have effectively stimulated economic development in Qinghai, Xizang, and neighboring provinces, they have also introduced new health and environmental risks. Reported cases of altitude sickness among visitors caused by hypoxia are on the rise, and the risk of hypoxia among short-term residents continues to increase.

Current research on hypoxia risk can be broadly divided into two major paradigms: mechanistic medical studies and spatial risk assessments. Medical research has elucidated the pathophysiological mechanisms of hypoxia through molecular biology and large-scale epidemiological studies. Notably, the “hypoxic exposure–compensatory capacity imbalance” model delineates the pathogenic cascade—from a blunted hypoxic ventilatory response to systemic injury mediated by erythrocytosis and pulmonary hypertension—thereby providing a theoretical framework for risk prevention [7,8,9]. In contrast, spatial risk assessments have predominantly been based on the oversimplified assumption of a linear relationship between altitude and risk [10]. Previous studies have typically quantified risk by examining correlations between altitude and key physiological indicators (e.g., oxygen partial pressure, blood oxygen saturation) or climatic comfort indices [6,11,12]. Although pioneering, these studies largely overlooked the complex and multidimensional nature of oxygen content, which is jointly influenced by interacting environmental factors such as vegetation, humidity, temperature, and altitude [13,14,15,16]. Therefore, accurately assessing hypoxia risk among short-term residents on the Tibetan Plateau requires moving beyond the traditional altitude-centric paradigm. We propose an integrated spatial evaluation framework grounded in disaster system theory that incorporates hazard-prone environments, disaster-inducing factors, and disaster exposure to achieve a comprehensive characterization of hypoxia risk [17].

Based on the above context, this study develops an integrated hypoxia risk assessment framework grounded in comprehensive disaster system theory to address the health challenges arising from the growing influx of short-term residents on the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau. Although previous studies have acknowledged the fundamental influence of altitude on hypoxia risk, critical unresolved issues persist regarding the dominant drivers of spatial variability in oxygen content, their interactions, and systematic approaches for evaluating hypoxia. To address these issues, this study integrates the GeoDetector method with disaster system theory to identify the key environmental determinants of oxygen content and evaluates the spatial distribution of hypoxia risk across three dimensions: hazard-prone environments, disaster-inducing factors, and disaster exposure. The findings not only advance the mechanistic understanding of hypoxia in high-altitude regions but also provide a robust scientific foundation for public health risk management under the dual pressures of climate change and intensified human activities.

2. Study Area and Data

2.1. Study Area

The Qinghai–Xizang Plateau extends from 25°59′30″ N to 40°1′0″ N and from 67°40′37″ E to 104°40′57″ E (Figure 1). It is bounded by the Pamir Plateau in the west and by the Hengduan Mountains and the western Sichuan Plateau in the east. To the north, its limits are marked by the Qilian, Altun, and Kunlun Mountains, and to the south by the Himalayan foothills [18]. With a mean elevation above 4000 m, it is the world’s highest and largest plateau, known as both the “Roof of the World” and Earth’s “Third Pole” [19]. The plateau supports diverse vegetation, including alpine meadows, cold and desert steppes, forests, and shrublands. Vegetation shows clear vertical and horizontal zonation, transitioning from forests in the southeast to deserts in the northwest. It contains numerous lakes and major rivers that supply freshwater to nearly one-third of the population in East and Southeast Asia [20], a role that has earned it the name “Asia’s Water Tower” [21]. The climate is governed by the combined influence of the monsoon and the westerlies. The mean annual temperature decreases from about 15 °C in the southeast to around 5 °C in the northwest. The region receives abundant solar radiation, totaling approximately 180 kcal/m2 annually, with sunshine durations of 2500–3200 h per year [6,22].

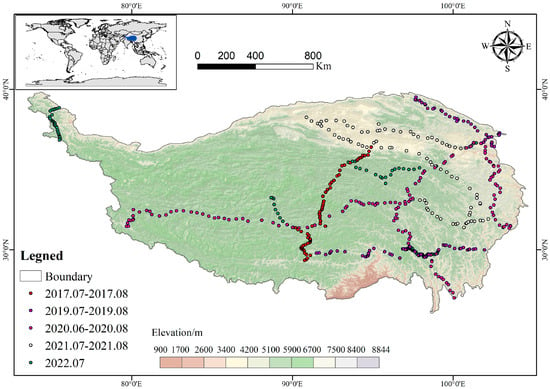

Figure 1.

Elevation of the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau and distribution of sampling points from 2017 to 2022.

The Qinghai–Xizang Plateau is rich in tourism resources, and the launch of the International Tourism Destination initiative has further accelerated their development [23]. These resources include vast natural landscapes—mountain ranges, glaciers, lakes, and grasslands—such as Qinghai Lake, Nam Co, Chaka Salt Lake, the Qilian Mountains, and the Kekexili Grasslands. As the cradle of Xizang culture, it also possesses equally rich cultural heritage. Lhasa, Geermu, and Xining are designated Outstanding Tourism Cities, whereas Shigatse, Gyantse, Tongren, and Kashgar are recognized as National Historical and Cultural Cities [6]. Over seven decades of planning and development have steadily improved infrastructure and transportation across the plateau [24], fostering the emergence of tourism corridors [25]. In the 21st century, tourist arrivals on the plateau have increased exponentially. For example, Qinghai Province received 44.8 million visitors in 2023 and 53.8 million in 2024, an increase of about 20% [26].

2.2. Sources of Data and Preprocessing

This study draws on natural environmental datasets encompassing elevation, precipitation, temperature, vegetation cover, and the relative oxygen content (herein termed oxygen content), while human activity was represented primarily by human footprint indices. Field measurements of oxygen content were conducted during July and August from 2017 to 2022, using a CY-12C digital oxygen analyzer (0−50.0% range, 0.1% resolution, ±1% accuracy) and a D400-SH-O2 portable oxygen meter (0−30.0% range, 0.01% resolution) (Figure 1). To reduce systematic error, measurements were taken simultaneously with three analyzers, and their averages were used for analysis, yielding more than 700 observations. Meanwhile, sampling was carefully designed to account for variations in altitude zones and topographic diversity (Supplementary Material). Spatial datasets of oxygen distribution for risk assessment were obtained from the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center, interpolated from July field measurements at a resolution of 1 km × 1 km in the WGS 1984 geographic coordinate system. Geographic location and elevation were recorded simultaneously during oxygen measurements, with elevation determined using Garmin Oregon 450 and Garmin 63sc GPS devices (±1′ accuracy for latitude and longitude, ±1 m accuracy for altitude). SRTM DEM data (90 × 90 m resolution) for risk assessment were obtained from the Geospatial Data Cloud Platform (https://www.gscloud.cn). Temperature and relative humidity were measured with a DPH-103 electronic thermo-hygrometer, with accuracies of ±0.01 °C and ±0.1%, respectively. Temperature and precipitation data for risk assessment were obtained from the National Earth System Science Data Center (https://www.geodata.cn). These datasets were produced by Peng et al. using the Delta spatial downscaling scheme, drawing on global 0.5° climate data from CRU and high-resolution climate data from WorldClim 2.0, and their reliability was confirmed through validation against observations from 496 independent meteorological stations [27]. Vegetation coverage data were obtained from the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center, specifically the 2017−2022 monthly dataset for the plateau published by Gao Jixi and colleagues. This dataset applies a pixel binary model based on the Normalized Difference Vegetation Index (NDVI), distinguishing pure vegetation and bare-soil pixels according to land-use types, with a spatial resolution of 250 × 250 m [28]. Net Primary Production data was obtained from the National Tibetan Plateau Data Center, and the source data comes from the MODIS product (MOD17A3H). Human footprint data were obtained from Mu and colleagues, who integrated eight factors—including roads, railways, population density, and nighttime lights—to construct a human footprint evaluation system. This dataset effectively captures the spatial distribution of transient population activity at a resolution of 1 × 1 km [29] (Table 1).

Table 1.

The source of each dataset in the study.

To ensure consistency across datasets, we applied unified spatial processing and standardization to multi-source data, including elevation, precipitation, temperature, vegetation cover, and oxygen content. First, to harmonize spatial scales and projections, all data were projected to the WGS-84/Albers equal-area coordinate system in ArcGIS. Bilinear interpolation was applied to resample raster data to a 1 × 1 km grid, reducing biases associated with differences in spatial resolution. Second, the fuzzy membership tool in ArcGIS was applied to standardize the indicator data, with the linear function selected as the transformation type. Notably, the elevation standardization followed previous studies, using a non-linear approach based on the relationship between elevation intervals and hypoxia risk. In the study by Cha et al., the incidence of acute mountain sickness was reported as 1.1–6.2% at altitudes between 2500 and 2800 m, 27–37% between 2800 and 3200 m, 40–63.8% between 3200 and 3600 m, 64–67% between 3600 and 4400 m, 77–100% between 4400 and 4800 m, and reached 100% above 4800 m [11]. Accordingly, we assigned values as follows: 0 for altitudes below 2500 m, 0.1 for 2500–2800 m, 0.3 for 2800–3200 m, 0.5 for 3200–3600 m, 0.7 for 3600–4400 m, 0.9 for 4400–4800 m, and 1 for altitudes above 4800 m [11].

3. Research Methods

3.1. Construction of the Hypoxia Risk Indicator System Grounded in Disaster System Theory

The hypoxia risk assessment system for short-term residents in plateau regions was developed the following comprehensive disaster system theory [30], encompassing three dimensions: the disaster-prone environment, disaster-inducing factors, and disaster-bearing entities [17]. The disaster-prone environment refers to the natural background and conditions that facilitate disaster occurrence, represented by four indicators: altitude, temperature, precipitation, and vegetation coverage. Disaster-inducing factors act as the direct triggers of disasters, primarily reflected in the spatial distribution of oxygen content. Disaster-bearing entities denote the components vulnerable to disaster impacts and losses, as indicated by human activity footprint data (Figure 2). The calculation formula is given as follows:

R = H × E

Here, R represents disaster risk, and H denotes hazard, which is jointly determined by the hazard-formative environment and hazard intensity and E signifies exposure. Both H and exposure E were normalized to a range of 0–1 using the Fuzzy Membership tool in ArcGIS 10.8 before being incorporated into the formula.

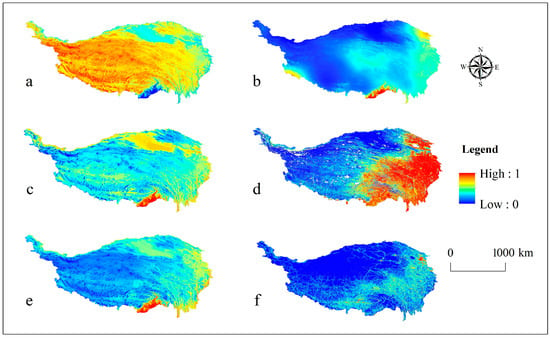

Figure 2.

Spatial Distribution Map of Indicator System ((a) Elevation, (b) Precipitation, (c) Temperature, (d) Fractional Vegetation Cover, (e) Oxygen Content, (f) Human Activity Footprint).

Altitude: Extensive research demonstrates a strong correlation between elevation and the likelihood of altitude sickness among short-term residents of the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau. At higher elevations, the risk of hypoxia increases markedly as the partial pressure of oxygen declines with decreasing atmospheric pressure. In response, the human body elevates respiratory and heart rates to maintain blood oxygen levels, yet prolonged exposure can still induce acute altitude sickness or chronic mountain sickness [18,31].

Temperature: Field data combined with census and meteorological records indicate that relative oxygen content in the Qilian Mountains of the northwestern plateau is, on average, 0.31% higher in summer than in winter, with the incidence of chronic mountain sickness reduced by 2.60–3.01% during the warmer season. Elevated temperatures also promote vegetation recovery, which further enhances oxygen levels [14]. Accordingly, temperature functions as an important environmental factor in disaster prediction models [13].

Precipitation: Comparative analyses between meteorological records from the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau and inland regions of China highlight the influence of atmospheric humidity on near-surface oxygen content [32]. Increased rainfall elevates air humidity, reducing airway dryness and relieving cardiovascular and pulmonary strain, thereby alleviating hypoxia-related discomfort. Moreover, sustained precipitation supports vegetation growth, which indirectly suppresses dust storms and surface thermal gradients, contributing to improved local microclimates.

Fractional Vegetation Cover: While vegetation on the plateau contributes oxygen through photosynthesis, its effect remains limited relative to the thin atmosphere and does not substantially alter the overall partial pressure of oxygen. Nonetheless, it can slightly enrich near-surface oxygen concentrations [15]. At the same time, regions with dense vegetation enhance soil and water conservation, reducing the respiratory burden caused by land degradation and bare surfaces, thereby indirectly mitigating hypoxia-related health risks.

Oxygen content: As a direct hazard factor, oxygen concentration exerts an immediate impact on exposed entities such as humans and livestock [14,17]. Under standard atmospheric pressure (101.325 kPa), oxygen accounts for ~20.95% of air volume. On the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau, however, surface oxygen levels deviate from this constant, showing marked spatiotemporal variability governed by elevation, temperature, and vegetation cover [33]. Declines below the standard 20.95% threshold indicate increased hazard intensity.

Human activity footprint: In the context of hypoxia risk, the disaster-prone population is primarily composed of individuals exposed to high-altitude environments. Unlike long-term residents, short-term groups—such as tourists, military trainees, and construction workers—lack physiological acclimatization, rendering them more vulnerable to acute mountain sickness. To capture this dimension, this study employs human activity footprint data as a proxy for regional population exposure and development intensity [29]. High-value areas, typically concentrated along tourism routes, transportation corridors, and construction zones, correspond to elevated exposure risks for short-term residents.

3.2. GeoDetector

GeoDetectors operate under the assumption that the study area is partitioned into multiple subregions. Spatial differentiation is inferred when the sum of variances within subregions is smaller than the total variance of the study area, whereas statistical correlation is suggested when the spatial distributions of two variables exhibit similar patterns [34]. According to the First Law of Geography, spatial attributes and phenomena display interrelated distributions governed by general principles of clustering, randomness, or regularity [34,35]. In this study, the Factor Detector and Interaction Detector components of the GeoDetector framework were primarily employed. The Factor Detector was applied to quantify variations in plateau oxygen content and to identify the dominant contributing factors, while the Interaction Detector was used to assess the effects of interactions between factors on these variations. In this study, the GeoDetector analysis was performed in the R statistical environment (version 4.5.1) employing the “GD” package (version 10.8). Continuous numerical variables were discretized using the package’s built-in optimal discretization function, which selects the stratification scheme that maximizes the q-statistic for each factor.

3.2.1. Factor Detector

The method aims to detect the spatial heterogeneity of the dependent variable Y and to evaluate the extent to which a specific independent variable X accounts for the spatial variation in Y. This relationship is quantified using the q-statistic, defined as follows:

Here, q represents the explanatory power of each influencing factor on the magnitude of oxygen content. N and σ2 denote the total sample size and variance, respectively, while and correspond to the sample size and variance within stratum. The q-value ranges from 0 to 1, with higher values indicating a stronger influence of the factor on the spatial distribution of oxygen content. A value of 0 implies that the factor has no explanatory power, whereas a value of 1 indicates that the factor fully accounts for the observed spatial variation in oxygen content.

3.2.2. Interaction Detector

The Interaction Detector is employed to evaluate the outcomes of interactions between different influencing factors, specifically to determine whether the explanatory power of the dependent variable Y increases, decreases, or remains independent when two factors act simultaneously. The interaction outcomes are interpreted as follows: q(X1∩X2) < Min(q(X1), q(X2)) indicates linear weakening after interaction; Min(q(X1), q(X2)) < q(X1∩X2) < Max(q(X1), q(X2)) indicates nonlinear weakening of individual factors; q(X1∩X2) > Max(q(X1), q(X2)) indicates that the interaction enhances the combined effect of the two factors; q(X1∩X2) = q(X1) + q(X2) implies that the two factors are mutually independent; and q(X1∩X2) > q(X1) + q(X2) indicates that the interaction strengthens a nonlinear effect.

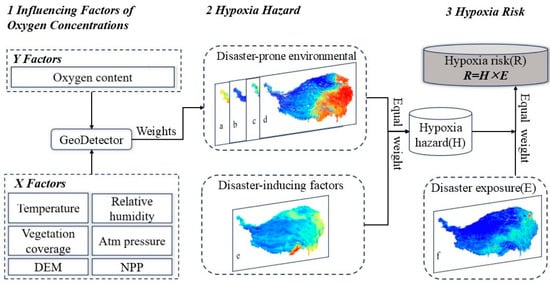

3.3. Technical Roadmap

The overall methodology of this study is structured around three sequential steps (Figure 3). First, using measured near-surface oxygen content data across the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau as the dependent variable, we selected a set of independent variables including in situ measurements of altitude, atmospheric pressure, temperature, and relative humidity, together with raster-derived indices of fractional vegetation cover and net primary productivity. Following data preprocessing to meet the input requirements of the Geodetector model, we applied this tool to quantify the influence of each factor on the spatial heterogeneity of near-surface oxygen content. Second, the contribution of each factor—expressed by the q-statistic obtained from the factor detector—was used as its spatial weight. Guided by the comprehensive disaster system theory, these weighted factors were integrated to evaluate the hazard of the disaster-prone environment. This environmental hazard layer was then combined with a measure of oxygen deficiency intensity as the disaster-inducing factors, using equal weighting, to map the spatial distribution of hypoxia hazard for short-term residents on the plateau. Finally, this hypoxia hazard layer was overlaid with a spatial dataset of population exposure for short-term residents, also under an equal weighting scheme, to generate a final assessment of hypoxia risk distribution for the short-term residents across the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau.

Figure 3.

The technical roadmap of study.

4. Results

4.1. Factors Influencing Variations in Near-Surface Atmospheric Oxygen Concentrations on the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau

4.1.1. The Result of Factor Detector

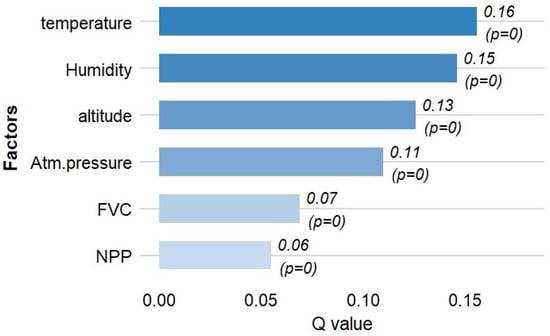

Factor analysis revealed that the spatial distribution of near-surface oxygen content is predominantly controlled by climatic and topographic factors, including temperature, humidity, elevation, and atmospheric pressure, whereas vegetation-related factors exert a comparatively minor influence (Figure 4). Among these factors, temperature displayed the highest explanatory power (Q = 0.156, p = 0), highlighting its primary regulatory role in variations of oxygen concentration. Temperature governs air density and atmospheric stability, thereby modulating oxygen diffusion rates and regional atmospheric circulation. It also indirectly affects local oxygen content by regulating snowmelt and surface energy fluxes. Humidity ranked closely behind (Q = 0.146, p = 0), suggesting that water vapor conditions substantially influence oxygen distribution. Elevated humidity often corresponds to enhanced evapotranspiration and local convective activity, which not only modulate vertical atmospheric exchange but may also indirectly affect oxygen levels through impacts on vegetation photosynthesis. Elevation (Q = 0.126, p = 0) and atmospheric pressure (Q = 0.110, p = 0) also revealed considerable explanatory power, reflecting the physical mechanisms whereby atmospheric and oxygen partial pressures decrease with increasing elevation, as typical in plateau regions. These findings are consistent with previous studies of hypoxic plateau environments, in which topographic factors directly regulate oxygen partial pressure, serving as the primary driver of oxygen concentration variations. Notably, despite the high correlation between elevation and atmospheric pressure, their Q-values diverge somewhat in factor detection, suggesting partial independence in their respective contributions to spatial variations in oxygen.

Figure 4.

Factor detection of near-surface oxygen concentration.

The explanatory power of Fractional vegetation cover (FVC, Q = 0.069, p = 0) and net primary productivity (NPP, Q = 0.055, p = 0) was markedly lower than that of climatic and topographic factors. This suggests that, although vegetation directly generates oxygen via photosynthesis and contributes to local microclimate regulation, its influence on regional or large-scale spatial patterns of atmospheric oxygen variation remains limited. These findings are consistent with previous studies on plateau ecosystems’ effects on atmospheric composition, indicating that vegetation processes predominantly modulate carbon cycling rather than exerting a decisive influence on atmospheric oxygen concentrations.

The validation of the factor detection Q-values in this study was conducted from both statistical and comparative perspectives. Statistically, all Q-values reported were found to be significant. Furthermore, our results align closely with existing literature [13,14,15]; for instance, the dominant factors identified—terrain and climate—are consistent with those reported in the study by Shi et al. on influencing factors of oxygen content. This consistency reinforces the reliability and credibility of the Q-values obtained in our analysis.

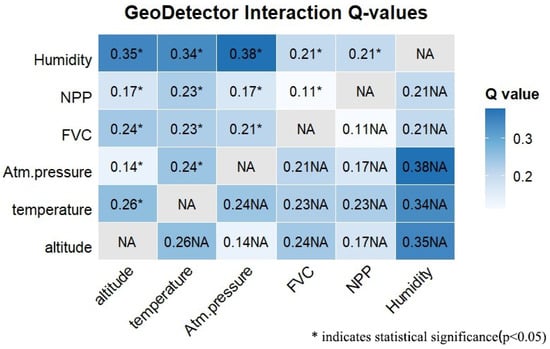

4.1.2. The Result of Interaction Detector

Interaction analysis revealed that the interplay between any two factors substantially increases the explanatory power for spatial variation in near-surface oxygen concentration (Figure 5). Overall, interaction effects generally surpass those of individual factors, indicating that the spatial distribution of near-surface oxygen concentration is not governed by a single environmental variable but emerges from the coupling of climatic, topographic, and ecological processes. Among these interactions, the coupling between humidity and other factors is particularly pronounced. The interaction between humidity and atmospheric pressure demonstrated the highest explanatory power (Q = 0.38), markedly exceeding the effect of either factor alone. This finding indicates that the interplay between water vapor conditions and pressure gradients plays a pivotal role in governing spatial variation in near-surface oxygen concentration. Similarly, the interaction between humidity and elevation or temperature (Q = 0.34) also displayed substantial explanatory power, indicating that in plateau environments, the combined effects of water vapor transport, orographic uplift, and thermal conditions markedly amplify spatial variations in near-surface oxygen concentration.

Figure 5.

Heatmap of factor interactions affecting near-surface oxygen concentration.

Among other factor combinations, the interactions between temperature and elevation (Q = 0.26), temperature and atmospheric pressure (Q = 0.24), and temperature and vegetation cover (Q = 0.23) were also markedly stronger than their respective individual effects. This indicates that temperature not only directly governs atmospheric physical properties but also indirectly shapes the spatial distribution of near-surface oxygen concentration by modulating atmospheric pressure and vegetation physiological processes. Relatively, although interactions between vegetation factors (FVC and NPP) and climatic or topographic factors demonstrated enhancing effects, their overall Q values (0.11–0.24) remained low, indicating that ecosystem processes exert limited regulatory influence on atmospheric oxygen concentrations at regional to large scales.

Overall, the interaction analysis further confirms the dominant influence of climatic and topographic factors, while emphasizing the amplifying role of humidity when interacting with other variables. These results suggest that the spatial variation of near-surface oxygen concentration arises from the combined influence of multiple factors, with the nonlinear coupling among climatic variables warranting further investigation.

4.2. Spatial Distribution of Hypoxia Hazard and Risk Among Short-Term Residents on the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau

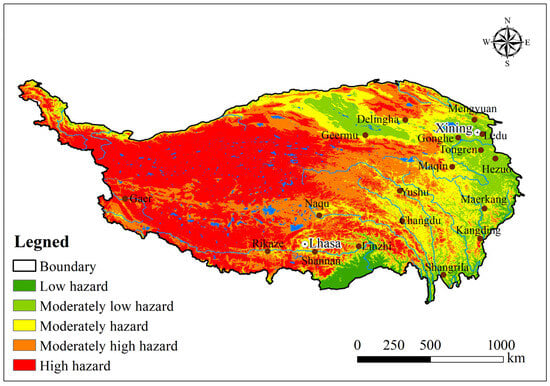

4.2.1. Spatial Distribution of Hypoxia Hazard Among Short-Term Visitors on the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau

Disaster-prone environmental factors were spatially overlaid with disaster-inducing factors. The spatial weights of these environmental factors were determined based on their contribution derived from Geodetector analysis. The overlay results were subsequently classified using the natural breaks (Jenks) method, producing the spatial distribution of hypoxia hazard among short-term visitors on the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau (Figure 6). Overall, the majority of the plateau exhibits high to moderately high hypoxia hazard levels. Extensive contiguous high-risk zones, covering approximately 65.0% of the area, are predominantly concentrated in the western, northern, and central interior regions, including Naqu, Geermu, and the Gaer area. This pattern closely correlates with widespread elevations above 4500 m and markedly reduced atmospheric pressure, leading to insufficient atmospheric oxygen and elevated hypoxia hazard. Moderate and moderately low-risk zones are mainly located along the eastern edge of the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau and in specific river valleys, including the Yellow river–Huangshui river Valley, Qaidam Basin, the central plateau, and western Sichuan Plateau, covering approximately 32.1% of the area. These regions experience milder hypoxia due to comparatively lower elevations and the mitigating influence of local topography and vegetation. In contrast, low-risk zones occupy a relatively small area, accounting for approximately 2.9%. These zones are mainly confined to low-altitude river valleys and mountainous areas along the southeastern edge, including Nyingchi, Medog, and Shangri-La, displaying a scattered, patchy distribution. This highlights the role of topographical variation in shaping the spatial differentiation of hypoxia hazard.

Figure 6.

Spatial distribution of hypoxia hazard among short-term residents on the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau.

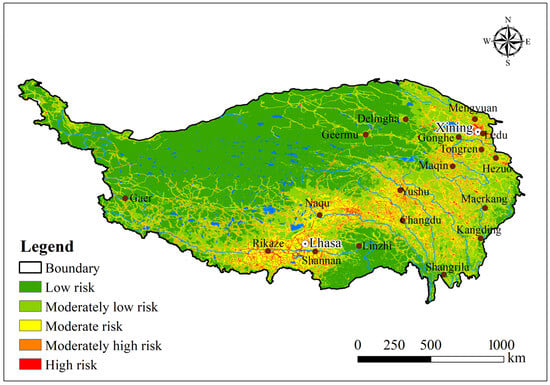

4.2.2. Spatial Distribution of Hypoxia Risk Among Short-Term Residents on the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau

By spatially overlaying hazard and exposure indicators according to Formula (1) and classifying risk using the natural breaks (Jenks) method, the spatial distribution of hypoxia risk among short-term visitors on the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau is presented in Figure 7. Overall, most areas of the plateau are classified as low-risk or low-to-moderate-risk zones, encompassing approximately 74.9% of the region. These zones are primarily distributed across extensive uninhabited areas and nature reserves in the plateau interior, particularly in the western and northern regions. Low human activity intensity in these areas results in limited exposure to hypoxia risk. High-risk zones largely coincide with areas of higher population density, dense transportation networks, or concentrated economic activity, including major plateau cities such as Lhasa, Xining, and Golmud. These high-risk zones occupy a small proportion of the plateau, accounting for merely 0.95% of the total area. In contrast, moderate and moderately high-risk zones are primarily concentrated along the eastern and southern peripheries, displaying distinct band-like patterns. These zones are notably prevalent along major transportation corridors, river valleys, and urban peripheries, encompassing approximately 24.2% of the total area. Importantly, from the perspective of disaster-prone environments and risk factors, these urban areas—though situated at relatively lower altitudes with generally milder hypoxia than the plateau interior—exhibit markedly elevated potential hypoxia risks due to high population density and frequent transportation and tourism activities. Moderate to high-risk zones strongly overlap with human activity hotspots, particularly along the Sichuan–Xizang Highway and the Yunnan–Xizang border region, displaying a characteristic “low natural risk–high exposure” pattern. This suggests that within the plateau’s overall hypoxic environment, population centers and regions of concentrated economic activity emerge as prominent zones of potential risk. Short-term visitors, including tourists, construction workers, and military personnel undergoing training, may face elevated health risks.

Figure 7.

Spatial Distribution of Hypoxia Risk Among Short-Term Residents on the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau.

5. Discussion

- (1)

- The spatial variation of hypoxia risk on the Tibetan Plateau is driven by the combined effects of natural environmental conditions and human activities. Within the disaster system theory framework, from the perspective of hypoxia hazard, high-altitude areas generally experience reduced atmospheric pressure and insufficient oxygen partial pressure, where natural conditions establish the fundamental pattern of hypoxia hazard. High-hazard zones are mostly distributed in regions with relatively harsh natural environments. From the exposure dimension, the high concentration of population density, transportation networks, and land use patterns reflects the exposure level of short-term residents. However, these areas are typically located in regions with relatively favorable or moderate environmental conditions, resulting in comparatively lower hazard levels. This leads to a distinct spatial mismatch between hypoxia hazard and the exposure of elements at risk: high-hazard areas exhibit low exposure, while low-hazard areas show high exposure. Further, from the mechanism of risk formation, risk is determined by the combined effect of hazard and exposure. Due to this superimposition effect, the spatial distribution of hypoxia risk aligns more closely with the spatial pattern of exposure. For instance, in valley areas and transportation corridors along the eastern and southern margins of the plateau, although the hypoxia hazard is relatively low, the high degree of urbanization, frequent tourism, and transportation activities result in a higher hypoxia risk for short-term residents. This “low hazard–high exposure” spatial pattern indicates that in areas with intensive human activities, the increase in hypoxia risk is primarily driven by exposure levels.

- (2)

- Compared with previous studies, the findings of this research more effectively capture the essence of “risk” assessment in evaluating hypoxia among short-term residents in high-altitude regions. For example, Liu et al. and Cha et al. focused on the functional relationship between blood oxygen saturation and altitude, dividing the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau into low-, medium-, and high-risk zones according to saturation thresholds at different elevations. Their spatial patterns broadly correspond to the hazard assessment results of this study [6,11]. However, their approach is essentially based solely on physiological oxygen saturation metrics, which corresponds more closely to hazard assessment and fails to incorporate key risk components such as human exposure and vulnerability. Consequently, their work primarily reflects the spatial distribution of hypoxia hazard among short-term residents rather than constituting a rigorous risk assessment. In contrast, this study extends hazard analysis by integrating human activity footprints—such as population density, transportation networks, nighttime light patterns, and cultivated land distribution—thereby offering a more robust and systematic assessment of hypoxia risk levels and spatial variation among short-term residents.

- (3)

- This study elucidates the spatial distribution of hypoxia risk among short-term residents on the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau; however, methodological constraints and data limitations necessitate further refinement in future research. The hypoxia risk map integrates a multi-year (2017–2022) composite of oxygen content with environmental drivers from a baseline year (2020). This approach is robust for identifying the dominant spatial pattern of risk, which was the primary objective. However, future studies could further refine our understanding by employing fully synchronous, year-specific datasets to potentially capture interannual dynamics in risk. In addition, due to the lack of precise spatial data on short-term residents, this study utilized a human footprint index—constructed based on land use, road networks, and built-up areas—as a proxy to represent the temporary spatial distribution of this population. Compared to traditional static population distribution data, the human footprint index more accurately reflects geographic agglomeration patterns formed by temporary human activities, thus better approximating the actual spatial behavior of short-term residents. Subsequent studies should incorporate more targeted mobility data, such as mobile positioning or transient population datasets, to enhance the accuracy of exposure assessment.

Individual differences constitute a critical determinant of hypoxia risk among short-term residents, yet they remain largely overlooked in existing assessments. Current evaluations predominantly rely on macro-level simulations of environmental conditions, often neglecting the substantial variability in physiological responses among individuals exposed to high-altitude environments. In practice, characteristics such as age, sex, health status, and lifestyle habits exert significant influences on blood oxygen saturation and an individual’s tolerance to hypoxia. Consequently, risk zoning based exclusively on environmental indicators cannot fully capture the actual health threats experienced by short-term residents. Future research should therefore integrate field observations with individual blood oxygen monitoring, combining physiological variability with environmental indicators to establish a more comprehensive risk assessment framework that accounts for both macro-environmental conditions and individual differences. Such an approach would not only enhance the scientific rigor and applicability of risk assessments but also provide more targeted guidance for health protection and medical interventions tailored to diverse populations. Furthermore, existing studies suggest that intensified global climate change may significantly influence oxygen content through rising temperatures. Future research could integrate climate projection scenarios with pathological models of acute high-altitude hypoxia to further investigate the evolution of hypoxia risk for short-term residents on the plateau under changing climatic conditions.

This study initially delineated the spatial distribution of hypoxia risk for short-term residents on the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau by integrating hypoxia hazard with human activity exposure. The resulting pattern represents a “preliminary proxy outcome” of risk. However, it is important to emphasize that, owing to the absence of comprehensive vulnerability indicators, the present assessment more closely reflects “potential risk” rather than “actual risk,” which would directly capture the tangible health impacts experienced by individuals or groups. Future studies could strengthen both the scientific rigor and interpretability of hypoxia risk assessments by incorporating additional indicators—such as infrastructure density, healthcare accessibility, and economic conditions—as proxies for vulnerability, contingent on data availability. Even the inclusion of limited vulnerability indicators would substantially enhance the explanatory power of such evaluations.

- (4)

- Based on the spatial heterogeneity of hypoxia risk identified in this study, we propose the following policy recommendations: In terms of healthcare resource allocation, it is advised to enhance specialized capacity for high-altitude disease management in medical institutions located in high-risk hypoxia areas, promote the establishment of plateau medicine research centers to deepen research on the health impacts of hypoxia, and equip grassroots facilities with portable blood oxygen monitors and oxygen therapy equipment. For public infrastructure planning, emergency oxygen stations and health monitoring points could be set up in tourist hotspots and transportation hubs. Furthermore, integrating oxygen environment assessment into regional planning systems and optimizing urban ventilation corridors and green space layout are recommended. These measures collectively form a preliminary framework ranging from emergency response to long-term health management, providing support for evidence-based governmental decision-making.

6. Conclusions

- (1)

- The spatial distribution of near-surface oxygen content across the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau is predominantly governed by climatic and topographic factors. Among these, temperature and humidity exhibit the highest explanatory power, followed by elevation and atmospheric pressure, while vegetation factors contribute only weakly.

- (2)

- Interactions among environmental factors substantially enhance the explanatory power for spatial oxygen variation. The coupling effects between humidity and atmospheric pressure, elevation, and temperature are particularly pronounced, underscoring that near-surface oxygen variation on the plateau is shaped not by a single driver but by nonlinear interactions among multiple factors.

- (3)

- The overall hypoxia hazard profile among short-term residents on the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau exhibits a widespread high-hazard pattern, concentrated in the western, northern, and central high-altitude interior regions. Compared to the hypoxia hazard among short-term residents, the spatial distribution of hypoxia risk is strongly shaped by human activities. High-risk zones are concentrated in densely populated towns, transportation corridors, and tourist destinations, giving rise to a characteristic coexistence of “high hazard–low exposure” and “low hazard–high exposure” patterns. This spatial heterogeneity reflects the interplay between hazard-prone environments and varying levels of human exposure.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijgi14120489/s1, Table S1: Surface oxygen concentration on the Qinghai–Xizang Plateau (2017–2022).

Author Contributions

Writing—original draft, Zemin Zhi; Conceptualization, Zemin Zhi, Weidong Ma and Fenggui Liu; Data curation, Qiong Chen, Yonggui Ma and Weidong Ma; Formal analysis, Zemin Zhi; Funding acquisition, Weidong Ma; Methodology, Zemin Zhi and Ziqian Zhang; Software, Zemin Zhi; Supervision, Qiang Zhou and Ziqian Zhang; Writing—review and editing, Zemin Zhi and Weidong Ma Investigation, Weidong Ma and Yonggui Ma. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Qinghai Provincial Central Government-Guided Local Science and Technology Development Fund Project, grant number 2025ZY017.

Data Availability Statement

The public data used in this study can be downloaded directly from the relevant websites. The results data presented in this study are available upon request from the corresponding author. The data are not publicly available due to privacy.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Yao, T.; Thompson, L.; Yang, W.; Yu, W.; Gao, Y.; Guo, X.; Yang, X.; Duan, K.; Zhao, H.; Xu, B.; et al. Different glacier status with atmospheric circulations in Tibetan Plateau and surroundings. Nat. Clim. Change 2012, 2, 663–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, T.; Piao, S.; Shen, M.; Gao, J.; Yang, W.; Zhang, G.; Lei, Y.; Gao, Y.; Zhu, L.; Xu, B.; et al. Chained Impacts on Modern Environment of Interaction between Westerlies and Indian Monsoon on Tibetan Plateau. Bull. Chin. Acad. Sci. 2017, 32, 976–984. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Zhong, L.; Fan, J. Regional function and spatial structure of National Park Cluster in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Acta Ecol. Sin. 2021, 41, 823–832. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, D.; Zhao, D. Characteristics of natural environment of the Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Technol. Rev. 2017, 35, 13–22. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, J.; Xu, Y.; Hu, L.; Wang, Z. Discovering spatial-temporal patterns of human activity on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau based on crowdsourcing positioning data. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2020, 75, 1406–1417. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, J.; Xin, Z.; Huang, Y.; Lin, F. Risk of hypoxia of short-term residents in Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Sci. Technol. Rev. 2022, 40, 92–100. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, Z.; Tian, M.; Yang, G.; Tan, Q.; Chen, Y.; Li, G.; Zhang, Q.; Li, Y.; Wan, P.; Wu, J. Hypoxia signaling in human health and diseases: Implications and prospects for therapeutics. Signal Transduct. Target. Ther. 2022, 7, 218. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T. Chronic mountain sickness on the Qinghai-Tibetan plateau. Chin. Med. J. 2005, 118, 161–168. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, T. Chronic mountain sickness on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Chin. J. Pract. Intern. Med. 2012, 32, 321–323. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, H.; Fang, C. Theory of human adaptation to plateau and its application to traveling to the Tibet. J. Arid. Land Resour. Environ. 2011, 25, 183–189. [Google Scholar]

- Cha, R.; Sun, G.; Dong, Z.; Yu, Z. Assessment of Atmospheric Oxygen Practical Pressure and Plateau Reaction of Tourists in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Ecol. Environ. Sci. 2016, 25, 92–98. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, Z.; Sun, G.; Feng, Q.; Luo, Z. Tourism Climate Comfort and Risk for the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Resour. Sci. 2014, 36, 2327–2336. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, P.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, G.; Tang, H.; Chen, Z.; Yu, D.; Yang, J.; Ye, T.; Wang, J.; Liang, S.; et al. Factors contributing to spatial-temporal variations of observed oxygen concentration over the Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 17338. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chen, Y.; Zhang, G.; Chen, Z.; Yang, X.; Chen, B.; Ma, Y.; Xie, H.; Luo, Q.; Yang, J.; Ye, T.; et al. A warming climate may reduce health risks of hypoxia on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Sci. Bull. 2022, 67, 341–344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shi, P.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, A.; He, Y.; Gao, M.; Yang, J.; Mao, R.; Wu, J.; Ye, T.; Xiao, C.; et al. Factors contribution to oxygen concentration in Qinghai-Tibetan Plateau. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2019, 64, 715–724. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.; Chen, Y.; Ma, H.; Ye, T.; Tang, H.; Wang, J. Further research on the factors contributing to oxygen concentration over the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Chin. Sci. Bull. 2021, 66, 4028–4035. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Wang, J. Investigation and Assessment of Disaster Risks in the Hypoxic Environment of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Region. Disaster Reduct. China 2023, 23, 42–45. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, D.; Tang, H. Environmental Factors Affecting Near-Surface Oxygen Content Vary in Typical Regions of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Front. Environ. Sci. 2022, 10, 145267. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, T.; Thompson, L.G.; Mosbrugger, V.; Zhang, F.; Ma, Y.; Luo, T.; Xu, B.; Yang, X.; Joswiak, D.R.; Wang, W. Third pole environment (TPE). Environ. Dev. 2012, 3, 52–64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Immerzeel, W.W.; Van Beek, L.P.H.; Bierkens, M.F.P. Climate change will affect the Asian water towers. Science 2010, 328, 1382–1385. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hou, Y.; Long, H.; Shen, J.; Gao, L. Holocene lake-level fluctuations of Selin Co on the central Tibetan plateau: Regulated by monsoonal precipitation or meltwater? Quat. Sci. Rev. 2021, 261, 106919. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; An, S.; Inouye, D.W.; Schwartz, M.D. Temperature and snowfall trigger alpine vegetation green-up on the world’s roof. Glob. Change Biol. 2015, 21, 3635–3646. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hu, L.; Xu, J.; Bao, C.; Pei, T. Influential factor detection for tourism on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau based on social media data. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, X.; Li, T.; Cao, X. Spatial Fairness and Changes in Transport Infrastructure in the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Area from 1976 to 2016. Sustainability 2019, 11, 589. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ye, S.; Li, Z.; Xi, J. A Model for Estimating the Tourism Carrying Capacity of a Tourism Corridor: A Case Study of the Qinghai–Tibet Plateau. Sustainability 2024, 16, 5466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, M. The Total Tourism Revenue of Qinghai Province in 2024 Was 51.659 Billion Yuan. Available online: http://www.qinghai.gov.cn/zwgk/system/2025/02/16/030065323.shtml (accessed on 20 August 2025).

- Peng, S.; Ding, Y.; Liu, W.; Li, Z. 1 km monthly temperature and precipitation dataset for China from 1901 to 2017. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2019, 11, 1931–1946. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, J.; Shi, Y.; Zhang, H.; Chen, X.; Zhang, W.; Shen, W.; Xiao, T.; Zhang, Y. China Regional 250m Fractional Vegetation Cover Data Set (2000–2024); National Tibetan Plateau Data Center: Beijing, China, 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mu, H.; Li, X.; Wen, Y.; Huang, J.; Du, P.; Su, W.; Miao, S.; Geng, M. A global record of annual terrestrial Human Footprint dataset from 2000 to 2018. Sci. Data 2022, 9, 176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P. Disaster Risk Science; Beijing Normal University Publishing Group: Beijing, China, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.; Zhang, L.; Liu, Z.; Chen, Z.; Li, Y.; Fu, Y.; Xiang, A.; Qi, J.; Zhao, R.; Wu, L.; et al. Effects of long-term very high-altitude exposure on cardiopulmonary function of healthy adults in plain areas. Sci. Rep. 2025, 15, 24826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shi, P.; Zhang, Y.; Chen, Y.; Zhu, W.; Hu, X.; Yang, H.; Jiang, L.; Ma, Y.; Tang, H. Investigation and Assessment of Disaster Risks in the Hypoxic Environment of the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau Region. Sci. Sin. Terrae 2024, 54, 517–528. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Shi, P.; Tang, H.; Wang, J.; Zhao, C.; Zhu, W. Vegetation oxygen production and its contribution rate to near-surface atmospheric oxygen concentration on the Qinghai-Tibet Plateau. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2023, 78, 1136–1152. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Xu, C. Geodetector: Principle and prospective. Acta Geogr. Sin. 2017, 72, 116–134. [Google Scholar]

- Zhi, Z.; Chen, Q.; Zhang, Q.; Zhou, Q.; Liu, F.; Zhao, F.; Chen, Y. Application of geographic detector in identifying influencing factors of landslide stability: A case study of the Jiangda County, Tibet. Chin. J. Geol. Hazard Control 2021, 32, 19–26. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).