Abstract

Urban neighborhoods in India face an uneven distribution and limited accessibility to parks and playgrounds, particularly in dense mixed-use areas where rapid urbanization constrains green infrastructure planning. To address these challenges, the Sustainable Transportation Assessment Index (SusTAIN) framework was developed to evaluate sustainable transportation in Indian urban neighborhoods, with ‘Accessibility’ identified as a crucial subtheme. Recent advancements in Geographic Information Systems (GISs) and urban data analysis tools have enabled accessibility assessments of parks and playgrounds at a neighborhood scale, yet the OSMnx approach has been only marginally explored and compared in the literature. This study addresses this gap by comparing three tools—the Quantum Geographic Information System (QGIS), OSMnx, and Space Syntax—for accessibility assessments of parks and playgrounds in Ward 60 of Kalyan Dombivli city, based on the 15-Minute City concept. Accessibility was evaluated using 25 m and 100 m grid resolutions under peak and non-peak conditions across public and private transportation modes. The findings show that QGIS offers highly consistent results at micro-scale (25 m), while OSMnx provides better accuracy at coarser scales (100 m+). The results were validated with space syntax through integration and choice values. The comparison highlights spatial disparities in accessibility across different tools and transportation modes, including Intermediate Public Transport (IPT), which remains underexplored despite its crucial role in last-mile connectivity. The presented approach can support municipal authorities in optimizing neighborhood mobility and is transferable for applying the SusTAIN framework in other urban contexts.

1. Introduction

Transportation is one of the important themes in neighborhood sustainability assessments, as mobility directly influences residents’ access to services, social inclusion, and environmental quality [1,2]. Various Neighborhood Sustainability Assessment (NSA) systems indicated that the transportation theme faces limitations with respect to its viability and applicability across different settings [1,2]. The sustainable transportation theme should be tailored to local conditions rather than adopted from NSA Systems [3]. Bahale et al. established the Sustainable Transportation Assessment Index (SusTAIN) framework to address the inadequacies of NSA systems in assessing mixed-use neighborhoods in India [1]. This framework consists of a well-defined array of indicators and sub-indicators that are organized under four distinct subthemes: (a) accessibility, (b) mobility, (c) external factors associated with mobility, and (d) land-use and socioeconomic factors. This study provides evidence that all indicators and sub-indicators within the SusTAIN framework are most strongly correlated with the accessibility subtheme. These results emphasize ‘Accessibility’ as a pivotal factor in neighborhood performance, highlighting its essential function in assessing how well land-use and transportation policies are integrated [1,4]. Easily accessible parks and playgrounds, one of the key components of Green Infrastructure (GI), serve as vital urban assets and strategic planning instruments, delivering multiple environmental, social, and health benefits that contribute to sustainable urban development [5,6,7,8]. Parks and playgrounds not only provide residents with opportunities for leisure, recreation, and exercise but also serve important ecological and landscape functions [5]. GI plays a vital role in the realization of the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) 2030, with Target 11.7 emphasizing the necessity of GI to ensure universal access to safe public spaces [6]. Green spaces, spatial approaches, and Geographic Information Systems (GISs) are widely used to examine the pattern of accessible urban green spaces [9,10,11,12,13]. Some of the main research fields focus on identifying areas that suffer from a lack of accessibility [9]. Indian neighborhoods have concerns about access and the uneven distribution of GI [13,14], yet existing accessibility analyses rarely integrate multiple travel modes or open-source frameworks adapted to local data conditions. This study addresses this methodological and empirical gap. Therefore, the authors propose a comparative analytical framework integrating multiple open-source tools to assess neighborhood-scale accessibility within the 15-Minute City (15 MC) paradigm. The framework incorporates locally dominant travel modes, including Intermediate Public Transport (IPT), to provide a more context-specific and comprehensive evaluation of urban accessibility.

1.1. Literature Review

The present research includes a literature review on the 15 MC concept and the literature studies on accessibility assessments, as well as a comparison of the open-source tools, QGIS, OSMnx and space syntax, used in modelling accessibility assessments. Also, the Indian urban development and urban transportation policies associated with the accessibility and the role of autorickshaw IPT in sustainable transportation practices in India are elaborated in the subsections.

1.1.1. The 15-Minute City (15 MC) Concept and Accessibility Assessment

The 15 MC concept was developed by Carlos Moreno in 2016 in response to the increasing challenge posed by longer commuting times, which adversely affect quality of life, and focuses on maximizing time efficiency in cities by ensuring residents can access essential services within a 15-minute walk or bicycle ride from their homes [15]. This model advocates for polycentric urban structures, promoting greater spatial accessibility and equity through the decentralization of services and infrastructure [16].

The 15 MC adapted its principals to a variety of contexts, geographic settings, and socio-demographic groups, but was primarily applied in the urban centers of developed countries, such as Spain [17,18], the United States [12,19,20], Saudi Arabia [21], Canada [22], France [20], Romania [23], Australia [20], Italy [24,25,26], and Sweden [27], whereas empirical studies on the accessibility aspects of the 15 MC concept remain sparse in developing regions, including Senegal [28], Brazil [28], Mexico [29], and China [30,31]. There is a notable lack of research on spatial accessibility metrics that assess the distance required to access PT and other essential urban services in Global South cities, particularly in India [32]. Both qualitative and quantitative methodologies have been utilized in examining the 15 MC concept. The qualitative survey method was employed in several studies, including analyses of walking accessibility for the aging population [27]. A quantitative assessment utilized a GIS-based walkability evaluation system specifically developed for Seoul city [16]. These studies addressed multiple spatial scales, including city level, neighborhood scale, and census-tract-level assessments [28]. The Urban Mobility Accessibility Computer (UrMoAC) functions as an open-source analytical tool for land-use and traffic demand models [29]. Liu et al. implemented a modified two-step floating catchment area (2SFCA) method to evaluate the 15 MC status of Hong Kong [33]. A GIS and Artificial Intelligence (AI) were integrated to estimate travel times for the assessment. The 15 MC concept has been evaluated at various spatial scales using differing assessment methodologies [34]. Nevertheless, for contemporary Indian cities to transition into resilient and sustainable urban areas, it is crucial to reintroduce walkability and accessibility into urban planning frameworks. The evaluation of accessibility is especially important at smaller spatial scales, such as wards and neighborhoods, where targeted measures can more effectively assess and enhance urban livability [35].

1.1.2. Modelling Accessibility with Open-Source Tools: QGIS, OSMnx, and Space Syntax

The accessibility assessment methodologies utilize a diverse range of open-source tools which offer significant advantages over proprietary alternatives, including public accessibility, transparency, reusability, and adaptability to specific research requirements [36,37]. In particular, Quantum Geographic Information System (QGIS) technology has facilitated the integration of heterogeneous geospatial datasets, thereby enabling accessibility analyses that incorporate human behavioral patterns alongside the physical and socioeconomic characteristics of urban environments [12]. Within this context, network analysis has emerged as one of the most effective approaches for evaluating the accessibility of green spaces [12]. While the network analysis capabilities of QGIS are well established, they are constrained in their capacity through built-in plugins or toolkits and have a limited ability to address multidimensional analytical requirements and efficiently process large-scale datasets [38,39]. To overcome these limitations, the Python 3.12.7 package, integrated into OSMnx, including NetworkX, is open-source, is able to analyze networks with large datasets, and can be customized as per need, place, and scale [38]. OSMnx provides built-in functions to acquire, model, and analyze street networks; compute optimal routes; project and visualize spatial networks; and systematically derive a range of metric and topological indicators. The tool supports accessibility assessments across varying spatial scales and produces outputs in both graphical and tabular formats, enabling comprehensive and reproducible urban network analyses [38,40]. OSMnx automatically simplified road network typologies by removing the redundant nodes and representing them as a singular edge [38]. In QGIS, there is a need to run several sets of commands or toolsets to simplify a network separately for geometrical and topological corrections. In parallel to conventional network analysis approaches, space syntax (SS) theory—which conceptualizes the configuration of urban space as a network of interconnected street segments—has gained substantial recognition within the fields of architecture and urban studies [41,42]. SS was initially proposed in the 1970s as an approach to study the morphology of cities [43]. The SS theory does not simplify the road network similar to QGIS or OSMnx; instead, it rebuilds the road network into axial lines or segment maps, which is the structural simplification process [42]. SS can better identify pedestrian-perceptual accessibility and local movement potential but will diverge from OSMnx and QGIS methods of analyzing network-based travel-time measures by various transportation modes. There is a gap between the transport study and SS study. It requires a different approach to combine the geometric analysis of SS with the geographic and cost-benefit analysis of transport modelling.

The literature on centrality, computed for various approaches, correlates centrality with one of the spatial network parameters [38,44]. It is necessary to know the maximum closeness centrality values of the network in order to determine where to place emergency service facilities that can enhance accessibility in the event of a disaster [45]. In parallel to conventional network analysis approaches, SS theory—which conceptualizes the configuration of urban space as a network of interconnected street segments—has gained substantial recognition within the fields of architecture and urban studies [41,42]. The SS methodology employs a graph-based representation of the street network, within this framework, accessibility, often referred to as ‘integration’, is assumed to have a linear relationship with movement patterns [41]. The centrality parameter in OSMnx correlated with the integration and choice values of SS but QGIS network analysis has limitations in evaluating centrality; but the ‘space syntax toolkit’ plugin from QGIS can fully support the SS method via Depthmap and QGIS tool compatibility for spatial representation and computation output in the generated attribute table. Numerous studies compare open-source and proprietary GIS tools; however, there is limited research in the literature in comparing the combined application of QGIS, OSMnx, and SS for accessibility evaluation at the neighborhood scale [36,46].

1.1.3. Accessibility and Indian Urban Development Policies

Indian urban planning reflects an evolving vision that enables the adoption of the 15 MC framework using a range of policy mechanisms and planning strategies [35]. The Urban and Regional Development Plans Formulation and Implementation Guidelines (URDPFI) 2015 underscore the importance of equitable access to urban services and transit infrastructure [47]. Additional policy instruments, including the Urban Greening Guidelines (2014) [48], emphasize promoting inclusive mobility, improved access to PT, and greater availability of green and public spaces [48]. The public transport accessibility toolkit was created by the Ministry of Urban Development, the Government of India, and the United Nations Development Program to systematically assess PT accessibility at the city scale [49]. The National Transit-Oriented Development (TOD) policy coordinates land-use and mobility planning to cultivate compact, walkable, high-density urban environments organized around transit corridors, facilitating improved access to public and green spaces [50,51]. Although the existing urban development policies, planning norms, master plans, and urban development initiatives in India demonstrate foresight regarding urban accessibility, there remains a critical need to incorporate more localized, micro-level planning approaches. There is a pressing need to contextualize and implement accessibility assessment methodologies within Indian urban planning, as the land development practices in India do not adequately reflect accessibility and mobility goals.

1.1.4. Intermediate Public Transportation (Autorickshaw) as a Sustainable Transportation Mode

Access to necessary amenities, facilities, and services may be achieved via either individualized or private transportation modes. In India, beyond the use of personal transportation modes, the autorickshaw sector represents a significant opportunity for advancing the sustainability of urban transport [52]. Autorickshaw functions as IPT or feeder mode, offering first and last-mile door-to-door connectivity and bridging the gap between private and formal public transportation options. It serves as an alternative to private motor vehicles and is accessible during off-peak hours as well as emergencies, such as health crises or other urgent trips [53]. The majority of autorickshaw stops are situated at key neighborhood intersections, adjacent to bus stops, or in proximity to busy destinations or buildings. Autorickshaws support connectivity in areas not directly served by public transport routes or where service frequency is inadequate [52]. Pulling rickshaws provide employment opportunities for unskilled migrant laborers in urban environments [54]. In Mumbai, for instance, autorickshaws constitute the primary motorized transport for accessing essential destinations, ranking just after buses; they are chosen more often than motorized two-wheeled vehicles for most trip types. Owing to their compact size and narrow frame, these three-wheeled vehicles are ideally suited for navigating the highly congested roads prevalent in India [55]. However, the contribution of autorickshaws to the accessibility of parks and playgrounds at the neighborhood spatial scale in Indian cities remains underexplored in the scholarly literature and is insufficiently addressed in urban policy.

1.2. Research Question

This research contributes to accessibility modeling by addressing two focal objectives: (1) comparing the analytical performance and spatial sensitivity of three open-source tools—QGIS, OSMnx, and space syntax—in evaluating accessibility to parks and playgrounds, and identifying the methodological basis of their differences; and (2) integrating Intermediate Public Transport within the 15-Minute City framework to quantify its contribution to neighborhood-scale accessibility in an Indian urban context. Accordingly, the present research is designed to answer the following research question:

How do QGIS, OSMnx, and space syntax differ in assessing micro spatial accessibility to parks and playgrounds across multiple transportation modes, including Intermediate Public Transport, within the framework of the 15-Minute City?

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Selection of the Study Area: A Mixed-Use Neighborhood in Kalyan Dombivli City

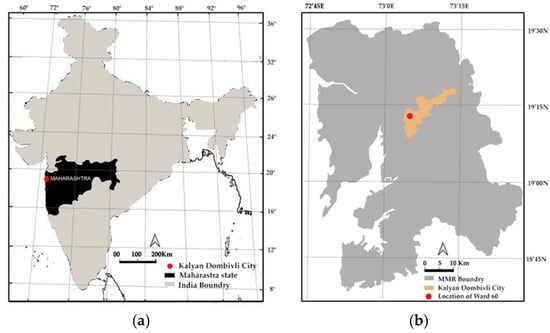

The selected study area for the accessibility assessment is Kalyan Dombivli twin City, situated in the Mumbai Metropolitan Region (MMR), about 48 km from central Mumbai. Kalyan Dombivli was designated as one of Maharashtra’s five Smart Cities under the Government of India’s Smart Cities Mission in 2016 [56]. This designation further justifies the relevance of examining accessibility and 15 MC principles within Ward 60, as it aligns with national policy priorities for sustainable urban development. The city’s northern and northwestern boundaries are defined by blue infrastructure, primarily the Ulhas River. Its linear urban form is bisected by a suburban railway, which separates Dombivli into eastern and western subcenters, termed Dombivli East and Dombivli West, respectively. Dombivli West constitutes the older segment of the city and is notable for its fine-grained residential patterns, whereas Dombivli East has experienced significant expansion as a result of regional infrastructure initiatives. Previous research from urban workshops focused on Kalyan Dombivli City has highlighted considerable difficulties pertaining to parking, accessibility, and PT within Dombivli West [1,57]. Therefore, this region was selected for an in-depth investigation to examine accessibility challenges and their root causes [57]. Figure 1a presents the location of Kalyan Dombivli city within Maharashtra state, India, while Figure 1b represents the location of Ward 60 neighborhood in Kalyan Dombivli city within the MMR boundary. Ward 60 exemplifies both the preservation of historic urban patterns and the introduction of new development forms, making it an essential example for evaluating transportation accessibility and urban change in dynamic suburban settings.

Figure 1.

(a) The location of Kalyan Dombivli city in Maharashtra state, India, and (b) the location of Ward 60 in Kalyan Dombivli city included in the MMR region.

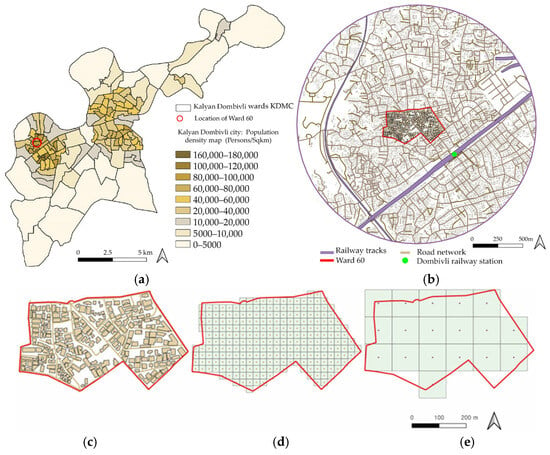

Ward 60, located in Dombivli West at coordinates 19.218433° N, 73.086718° E, is a densely populated mixed-use locality where commercial establishments and residential dwellings coexist, and a variety of building types, including low-rise, mid-rise, and commercial buildings, are present. The topography of Kalyan Dombivli is predominantly flat, with minor elevation differences below 10 m across Ward 60. Such variations exert negligible influence on walkability or network-based accessibility, thereby allowing uniform grid-based analysis. Municipal statistics indicate a population of 12,727 residents in this neighborhood. The advantageous location near the Dombivli railway station enables efficient connectivity to various sectors of the city and the adjacent urban centers. Figure 2a,b illustrates the location of Ward 60 in Kalyan Dombivli city, showing a ward-wise population density map and Ward 60 and the study area within a 1200 m radius from the ward’s center, respectively.

Figure 2.

(a) Population density distribution in Kalyan Dombivli city, highlighting the location of Ward 60 situated in a high-density area with a reported density of 80,463 persons/km2 according to municipal data. (b) Ward 60 and the study area within a 1200 m radius from the ward’s center. (c) Ward 60 displaying building footprints alongside the road network. (d) The division of the neighborhood into 253 grids, each with dimensions of 25 m × 25 m. (e) The division of the neighborhood into 18 grids, each with dimensions of 100 m × 100 m.

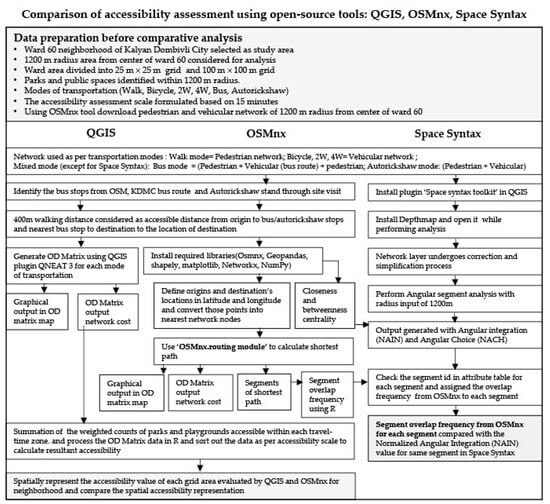

2.2. Methodological Approach of Comparative Analysis

For the comparison of the accessibility assessments by QGIS and OSMnx, the OD matrices for 25 m and 100 m were both generated using the QGIS and OSMnx methods. The extensive data generated from the OD matrix for the six modes of transportation were further processed and analyzed using the ‘R’ data analysis tool. The spatial distributions of accessibility values for six modes of transportation, considering peak and non-peak hours, were plotted by associating the accessibility values with each spatial grid by integrating them into the QGIS in tabular format.

Additionally, the authors evaluated ‘Closeness and Betweenness’ centrality using OSMnx for the 1200 m area from the center of Ward 60. The integration (NAIN) and choice (NACH) values of space syntax correlated with land-use accessibility. The segment overlap frequency output was derived from OSMnx, and compared with closeness, betweenness centrality, and also the NAIN and NACH values generated from the space syntax method. Figure 3 shows a flow chart illustrating the comparative analysis of the accessibility assessment methodologies applied to parks and playgrounds within a 1200 m radius area from the center of Ward 60 using three open-source tools, QGIS, OSMnx, and space syntax.

Figure 3.

Flow chart illustrating the comparative analysis of accessibility assessment methodologies applied to parks and playgrounds within a 1200 m radius area from the center of Ward 60 using three open-source tools, QGIS, OSMnx, and space syntax.

2.3. Parameters of Accessibility Assessment

Establishing standardized parameters is essential to ensure methodological consistency and enable a valid comparative analysis of park and playground accessibility across multiple open-source tools.

2.3.1. Neighborhood Destinations Such as Parks and Playgrounds

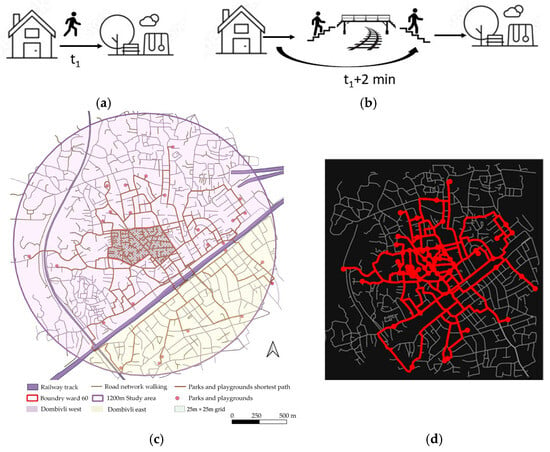

A total of 26 parks and playgrounds located within a 1200 m radius from the center of Ward 60 were identified based on KDMC zoning data and verified through Google Maps and on-site field surveys. Only facilities that are publicly accessible and larger than 100 m2 were included. Out of the total number of parks and playgrounds, 18 parks and playgrounds are located in Dombivli West, while 8 were in Dombivli East, as shown in Figure 4c.

Figure 4.

(a) The time (t1) needed to access destination types from the Dombivli West area; (b) the time (t1 + 2 min) required to reach the destinations from the Dombivli East area by walking; (c) OD matrix shortest path to parks and playgrounds using walking as a transportation mode for both the Dombivli East and Dombivli West areas, by QGIS method; (d) OD matrix shortest path to parks and playgrounds using walking as a transportation mode for both the Dombivli East and Dombivli West areas, by OSMnx method.

2.3.2. Transportation Modes

For analysis, the transportation modes utilized by residents for accessing the various destination types were identified and classified as either personal or public. Personal transportation options comprised walking, bicycles, two-wheelers (2Ws), and four-wheelers (4Ws), whereas public transport (PT) included buses and autorickshaws are the IPT used in Kalyan Dombivli city. Data on these transportation choices were sourced from site surveys through local providers to ensure the study’s validity and contextual accuracy.

2.3.3. Networks or Routes

The transportation network represents an essential aspect in accessibility analysis, as each mode of transport utilizes designated paths within the urban road system to access destinations. Examples include pedestrian networks, vehicular networks, bicycle lanes, and PT corridors, vehicular and pedestrian bridges, each of which differs based on the local urban context, geographic characteristics, and infrastructure policies. If the community can reach a particular facility within 1200 m of the road length, it means that the residential community meets the standard coverage of this public service facility being within a 15 min walking distance [30]. The network around a 1200 m radius from the center of Ward 60 was downloaded by the ‘osmnx.graph.from_address’ module with ‘network_type = walk/drive’ and ‘distance = 1200’. Depending upon the transport mode, the ‘network_type’ was selected and retrieved the street network data, including the vehicular and pedestrian routes input within the buffered extent from OpenStreetMap’s Overpass API. The downloaded network data are topologically corrected, and the networks are projected and saved as SVGs, GraphML files, or shapefiles for later use [38].

2.3.4. Distance to PT and IPT Stops

When a larger proportion of residents or employees are located near transit access points, the likelihood of PT utilization increases significantly [32]. The average walking speed of a human is 4.7 km/h [1,58]. The 15 MC framework, as well as Clarence Perry’s neighborhood concept, emphasizes placing amenities within a 400 m walkable distance [59]. Similarly, the URDPFI Guidelines recommend a maximum distance of 400 m to access PT and IPT stops [47].

2.3.5. Accessibility Scale

The authors have proposed a ten-point scale to standardize accessibility assessment values for comparative analysis. This percentage-based accessibility assessment scale translates findings into values ranging from 10% to 100%. The resultant measure corresponds to the time required to arrive at defined destinations. Thus, the assessment scale incorporates a temporal dimension, categorizing the travel time to destinations within a time zone as follows: ( ≤ 3), (3 < ≤ 5), (5 < ≤ 6.5), (6.5 < ≤ 8), (8 < ≤ 9), (9 < ≤ 10), (10 < ≤ 11.5), (11.5 < ≤ 13), (13 < ≤ 15), and > 15) minutes, as presented in Table 1. According to the 15 MC model, the time to access fundamental amenities and facilities should not exceed 15 min, which aligns with key sustainability objectives [1,60,61].

Table 1.

The accessibility evaluation scale is defined according to accessibility assessment score, which is assigned within the range of (10 to 100) %.

2.3.6. Peak and Non-Peak Hours of the Day

The time interval within a day during the highest demand for transportation and services was recognized by significant increases in commuter traffic as individuals travel to various destinations. Conversely, traffic demand is comparatively lower during non-peak hours. The selection of peak and non-peak periods was informed by visual traffic surveys and informal commuter interviews conducted at primary intersections and transit nodes within Ward 60 and its vicinity. The data generated for peak and non-peak hours duration, as well as average vehicular speed during peak and non-peak hours are included in the Supplementary Material S6. Although no official traffic data are available for this ward, these field observations provided localized insights into commuting patterns. Based on the site survey and available modes of transportation in the city, a summary of the transportation modes, including their average speeds, the network types for each mode, the OD Matrices generated, the names of the origins and destination types, the journey and delay times due to impedance, and the calculated total time, are represented in Table 2 and Supplementary Material S7.

Table 2.

A summary of the transportation modes, including their average speeds, the network types for each mode, the OD matrices generated, the names of origins and destination types, the journey and delay times due to impedance, and the calculated total times.

2.3.7. Distribution of 25 m and 100 m Grid

The ‘research tools’ function from the ‘Vector’ menu of QGIS was used to partition a Ward 60 map into consistent 25 m × 25 m and 100 m × 100 m square grids. The centroids of each grid cell were generated using the ‘geometry’ tool. These centroids served as origin points or representations of residential addresses. Figure 2c displays the building footprints in Ward 60 alongside the road network and Figure 2d,e illustrates a total of 253 origin points, and a total of 18 origin points for a 25 m and 100 m grid division of Ward 60, respectively, ensuring exhaustive coverage of the neighborhood. This organized grid-based sampling strategy prevented the bias associated with arbitrary origin-point selection.

2.3.8. Selection of 1200 m Catchment Area for Analysis

The overall 1200 m distance corresponds to 15 min by walking. A uniform catchment radius of 1200 m was applied for all travel modes to maintain analytical consistency across tools and scales. This threshold aligns with the 15 MC principle of evaluating neighborhood accessibility within a 15 min travel horizon [1]. Similar standardized catchments have been adopted in comparative accessibility studies emphasizing framework validation rather than behavioral travel time prediction [62,63,64]. In space syntax analysis, the literature indicates that integration at a 1200 m radius works well with land-use accessibility [65]. The fixed 1200 m radius boundary from the center of Ward 60 thus functions as a standardized reference zone, allowing a direct comparison of the results from QGIS, OSMnx, and space syntax without introducing scale-related bias. Various place-based measurement approaches have been employed in the literature, including the travel distance to the nearest service location and the number of services within a particular areal unit (e.g., census tract) or within a specified cut-off distance [63,66].

2.4. Accessibility Assessment by QGIS, OSMnx, and Space Syntax

The accessibility assessments using each of the three tools for all six modes of transportation are discussed individually in the subsequent sections. The common parameters mentioned in (Section 2.3) were considered before the accessibility assessment was evaluated by both OSMnx and QGIS methods. Section 2.4.1 and Section 2.4.2 mentioned the steps that needed to be performed to generate the OD matrix shortest path to parks and playgrounds.

2.4.1. Computation of OD Matrix Shortest Path to Parks and Playgrounds by QGIS

This study applied QGIS 3.22.13 Bialowieza for accessibility analysis. The QGIS Network Analysis Toolbox 3 (QNEAT3) plugin of QGIS 3.22.13 provides a suite of algorithms ranging from basic shortest path calculations to advanced analyses, including Iso-Area (service areas, accessibility polygons) and OD matrix computation [67]. This plugin facilitated an accurate determination of the shortest paths between origin and destination points along the input network within QGIS.

2.4.2. Computation of OD Matrix Shortest Path to Parks and Playgrounds by OSMnx

The following steps need to be performed to generate the shortest path and OD matrix. Firstly, the various essential libraries installed in the Python interface include OSMnx, Geopandas, Shapely, Matplotlib, NetworkX, and NumPy. The latitude and longitude of the points of origin and destinations are updated and converted into the nearest node using the ‘osmnx.distance.nearest.nodes’ module. OSMnx identified the nearest node to the origin point and the nearest node to the destination, accessible via the given input network type. The OD matrix was computed using the ‘osmnx.routing.shortest_path’ module and the ‘length’ as a weight [68].

The procedures explained in Section 2.4.1 and Section 2.4.2 were repeated to generate the OD matrices to evaluate accessibility through all transport modes. The pedestrian network was used for walking and the vehicular network for bicycles, 2Ws, and 4Ws. To generate OD matrices for transport by bus, three journeys were considered as explained in Section 2.4.3: Accessibility Assessment Using a Bus as the Mode of Transport. For the autorickshaws, two distinct journeys were considered, as indicated in Section 2.4.3: Accessibility Assessment Using Autorickshaws as the Mode of Transport.

The details of OD matrix generation methods for each transportation mode are as follows.

2.4.3. Accessibility Assessment Using Various Mode of Transport

Ward 60 is located in the Dombivli West region. Amenities in the western part of Dombivli can be accessed without needing to cross the skywalk (as depicted in Figure 4a), whereas accessing amenities in Dombivli East involves traversing the skywalk or over-bridge (as illustrated in Figure 4b). To ensure an accurate evaluation of walking accessibility to amenities in the eastern vicinity, the total travel time included the duration required to ascend and descend the skywalk stairs. Field observations indicated that it takes approximately two minutes to ascend, cross, and descend the skywalks.

The OD matrix of the shortest path, OD matrix map, and travel cost in an attribute table were generated according to the OD matrix methodology mentioned in Section 2.4.1 and Section 2.4.2, which displayed the total distance (in meters) between each origin point and the corresponding destination. Figure 4a,b represents accessibility to the destinations located in the Dombivli West and Dombivli East areas, respectively. Two distinct OD matrices were created: (ODw1) for Dombivli West and (ODw2) for Dombivli East. Figure 4c represents the OD matrix shortest path to parks and playgrounds using walking as the transportation mode for both the Dombivli East and Dombivli West areas, by QGIS method. Similarly, Figure 4d shows the OD matrix shortest path to parks and playgrounds using walking as the transportation mode for both the Dombivli East and Dombivli West areas, by OSMnx method.

The distances of ODw1 and ODw2 were then converted into time values, t1 and t1+21, based on a typical walking speed of 4.7 km/h, enabling a standardized interpretation of the accessibility values [1,58]. The t1 and t1+2 values are then used for calculating the accessibility and of each grid point for the destinations located in Dombivli West and East, respectively. The average of and is the accessibility for each grid point (i).

where is the average accessibility of each grid point (i);

is the accessibility of each grid point for the destinations located in Dombivli West;

is the accessibility of each grid point for the destinations located in Dombivli East.

Accessibility Assessment Using a Bus as the Mode of Transport

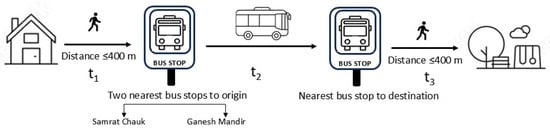

A bus is designated as a mixed-mode of transportation, and, as such, the accessibility assessment was conducted in the following three stage journeys using buses as the transportation mode: walking (pedestrian route) to the bus stop, then the bus route (vehicular route) to the bus stop nearest to the destination, and then again from the bus stop nearest to the actual destination point by walking (pedestrian route), as shown in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

Schematic representation of accessibility to the destination by bus, showing the process from the origin point to the nearest bus stop on foot, followed by the bus journey, and finally walking from the destination stop to the targeted location.

The frequency, route, and stoppages of PT (bus): The frequency of PT and services has a substantial impact during the evaluation process. An ideal PT frequency is less than three minutes, effectively minimizing passenger waiting times at stops. The assessment of accessibility to parks and playgrounds using a bus involved the consideration of multiple attributes, such as bus route information, bus stop locations, bus service frequency, average bus speed, and the grid areas covered by each bus stop.

The initial step was to identify the bus routes serving Ward 60. Based on schedules from the local transit authority, only one bus route, that of Bus No. 54, covers this locality. All the bus routes and bus stops located within a 1200 m radius from Ward 60’s center were mapped using GIS technology. As per the schedule, the No. 54 bus serves 18 stops within this radius, starting from Dombivli West. Ward 60 has access to two bus stops, Samrat Chauk Stop and Ganesh Mandir Stop, both situated on the No. 54 route. The average bus speed during non-peak hours was estimated by analyzing the required travel time to each stop along with the route length. The interval between consecutive No. 54 buses is 58 min.

Journey 1: Accessibility from origin points to the nearest bus stop: The (ODb1) matrix was created to analyze accessibility from origin points to Samrat Chauk and the Ganesh Mandir bus stops in the neighborhood. The centroids of grids that exceed a 400 m walking distance from both bus stops were considered inaccessible by bus and excluded from further analysis. The distance in the OD matrix was then converted to time ‘t1’ based on a walking speed of 4.7 km/h.

Journey 2: Accessibility along the bus route from the origin bus stop (BS1) to the destination bus stop (BS2): This step focuses on evaluating accessibility along the bus route spanning from the origin bus stop to the destination bus stop. The travel time along the bus corridor, denoted as t2, was computed using the (ODb2) Matrix.

Journey 3: Accessibility from the destination bus stop (BS2) to the final destination: The (ODb3) was generated to analyze accessibility from the bus stops along the No. 54 bus route to reachable destinations within a 1200 m radius. The park and playground destinations that exceeded a 400 m walking distance from either of the nearest bus stops were considered inaccessible by bus. The distance was then converted to time ‘t3’ based on walking speed. Figure 5 presents a visual representation of all three journeys covered during the accessibility assessment when traveling from origin to destination by bus.

The total time ‘t’ from the origin points to destinations within a 1200 m radius from each grid point of Ward 60 was obtained by aggregating each journey travel time (t1 + t2 + t3) for Samrat Chauk and Ganesh Mandir individually.

Total accessibility by bus for each grid point was evaluated by averaging the accessibility assessment from origin points to parks and playgrounds via Samrat Chauk ‘’ and Ganesh Mandir ‘’, both bus stops.

Accessibility Assessment Using Autorickshaws as the Mode of Transport

Four autorickshaw stops serving Ward 60 near the street intersection were identified during a site visit. A field survey was conducted to determine the average speed and frequency of autorickshaws during both peak and non-peak hours. For peak and non-peak periods, the expected speed of autorickshaws was set at 15 and 20 km/h, respectively. The observed autorickshaw frequency was below three minutes.

In the case of autorickshaws, the two-stage assessment included walking to the nearest autorickshaw stop using a pedestrian network, then the travel time from the autorickshaw stop to the destination reached by a vehicular route, as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

The evaluation of accessibility to destinations using autorickshaws as the mode of transport accounts for access to the autorickshaw stop nearest to the origin point on foot, followed by the travel time to the desired destination with autorickshaw service.

Journey 1: Accessibility from origin points to the nearest autorickshaw stop: The (ODa1) matrix was generated to assess pedestrian accessibility from each origin point to the nearest four autorickshaw stops (autorickshaw stop 1, autorickshaw stop 2, autorickshaw stop 3, or autorickshaw stop 4). Origin points located more than 400 m from all autorickshaw stops were labeled as inaccessible. Conversely, points within a 400 m range of at least one autorickshaw stop were considered accessible. The distance in ODa1 was then converted to time ‘t1’ based on a walking speed of 4.7 km/h.

Journey 2: Accessibility from the autorickshaw stop to the destinations: This analysis evaluates accessibility to destinations from all four autorickshaw stops. Four OD matrices (ODa2, ODa3, ODa4, ODa5), corresponding to each autorickshaw stop and destination, were generated and the travel time to a destination is denoted as t2.

Each travel time segment (t1 + t2) was combined to estimate the total accessibility time from each grid point of Ward 60 to the destinations. Total accessibility by autorickshaw for each grid point was evaluated by averaging the accessibility values , , , and ) from the origin points to parks and playgrounds using autorickshaw stop 1, autorickshaw stop 2, autorickshaw stop 3, and autorickshaw stop 4, respectively.

Accessibility Assessment Using a Bicycle, 2W, and 4W as the Mode of Transport

The assessment procedure that was employed in Section 2.4.1 and Section 2.4.2 was incorporated for the vehicular network to evaluate accessibility by personalized modes including a bicycle, 2W, and 4W, as represented in Figure 7. The OD matrix (ODx) was generated for a bicycle mode from each grid point to parks and playgrounds, with travel time via bicycle denoted as t. For the 2W and 4W, the separate OD matrices (ODy) and (ODz) were constructed, focusing on connections from origin points to parks and playgrounds.

Figure 7.

The evaluation of accessibility to parks and playgrounds using a bicycle, 2W, and 4W as modes of transport accounts for direct access from the origin point to parks and playgrounds.

2.4.4. Data Analysis Using R

In this research, the authors utilized the open-source software R (version 4.4.0, released 24 April 2024), which is extensively employed for computation, data analysis, and data visualization [69]. R packages comprise functions, documentation, and data that extend the capabilities of R software. During the accessibility assessment, comprehensive datasets were produced in .csv format via the OD matrices for parks and playgrounds across all transportation modes. The statistical analysis was carried out using the ‘tidyverse (3)’ and ‘dplyr (2)’ packages [70,71]. Distances indicated in the OD matrices were translated into travel times for both peak and non-peak hours, and for each transportation mode, by dividing the total distance by the average speed of each mode during the respective time periods. Table 2 outlines the speeds for each mode of transport. To calculate accessibility values for each origin ID and neighborhood, the data in ‘time’ format were processed further using the ‘sort’, ‘filter’, ‘cbind’, ‘unlist’, and ‘Map’ functions. Visualizations were developed using the ‘ggplot2’ package [72].

2.4.5. Accessibility of a Grid and Average Accessibility of Ward 60 (GIS and OSMnx Method)

The accessibility assessment value of each grid was calculated as the summation of the weighted number of parks and playgrounds accessible within the predefined travel time zones: ( ≤ 3), (3 < ≤ 5), (5 < ≤ 6.5), (6.5 < ≤ 8), (8 < ≤ 9), (9 < ≤ 10), (10 < ≤ 11.5), (11.5 < ≤ 13), (13 < ≤ 15), and > 15) minutes. A weighting factor was assigned to each time zone according to the level of accessibility, with values ranging from 0.1 to 1. The highest weight (1.0) was assigned to the shortest time zone (t ≤ 3 min), while the lowest weight (0.1) was assigned to the longest time zone (t > 15 min), as indicated in Table 1.

The accessibility of each grid for each mode of transportation was calculated by Formula (4), and the average accessibility of Ward 60 was then computed for both 25 m and 100 m grid sizes across all transportation modes, as per Equations (5) and (6), respectively. The results were visualized spatially in maps for peak and non-peak hours for both QGIS and OSMnx.

where

Gi is the accessibility of each grid.

i is the grid number. For 25 m and 100 m grids, i is varied from 1 to 253 and 1 to 18, respectively.

j is the time zone of the accessibility time scale.

Wj is the weight given according to the time zone.

Nj is the number of parks and playgrounds accessible in each time zone.

2.5. Betweenness Centrality and Closeness Centrality by OSMnx

Closeness centrality computes the ease with which a street segment or node can reach all other parts of the network. Highly connected areas tend to have faster travel times to many destinations. The present research utilizes NetworkX functions on the OSMnx graph to compute different centrality measures, integrating with QGIS software for data preparation, graphical visualization, and analysis. The ‘Node’ and ‘Segment’ products (point shapefile) and (line shapefile) represent street intersections and segments extracted from OSM and were used to model pedestrian and vehicular movement. OSMnx corrected the topology and calculated metric and topological measures, including centrality and betweenness. Betweenness centrality generated through the input of nx.betweenness_centrality (G,weight = “length”) measures the proportion of shortest paths between all pairs of nodes that pass through the given node. The OSMnx tool is used to generate node and closeness centrality through the input of the nx.closeness_centrality code function in the NetworkX environment. Finally, it saves each street network and street node as shapefiles in the graph, which can be further imported into QGIS for visual analysis.

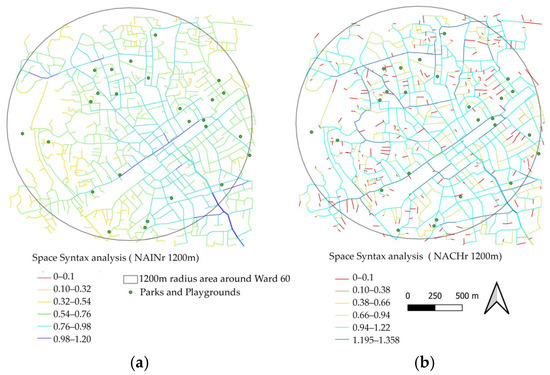

2.6. Normalized Angular Integration (NAIN) and Normalized Angular Choice (NACH) in Space Syntax

A space syntax analysis was conducted to examine the spatial configuration of the street network and spatial accessibility to all destinations from origin points within the study area. That integration represents the to-movement potential of a space, and choice, the through-movement potential, pointing out also that the two measures correspond to the two basic elements in any trip, selecting a destination from an origin point (integration), and choosing a route, and so the spaces to pass through between origin and destination (choice) [73]. The initial correlation results between space syntax measurements and land-use accessibility show that integration has a higher correlation with land-use accessibility variables than choice [65]. Spatial accessibility measures, NAIN and NACH values, are expressions of the potential for human movement within urban spaces, and both would strengthen the node place value to enhance the movement of people and the local economy [65,74]. QGIS has more comprehensive spatial data management and geographic analysis capabilities. The metric distance analysis of QGIS and the topological analysis of space syntax were integrated in this study to construct the spatial geographic and Depthmap information of the street network within a 1200 m radius area of Ward 60.

The ‘space syntax toolkit’ is a QGIS plugin that allows an interface with the Depthmap program [75]. The road network datum of the walkable street network was procured from the OSMNx plugin through the integration of Networkx and the OSM open street map. The network data imported into the QGIS environment was corrected for invalid geometry, duplicates, and overlaps. The axial model with an open street map (OSM), a Road Centre Line (RCL), and Open Roads models was simplified using the Douglas Peucker (DP) simplification algorithm and proposed modelling rules. The simplification was performed with 5 m thresholds; the latter model’s betweenness centrality value, with modelling rules, approximated more measures from the axial Angular Segment Analysis (ASA). These authors emphasized that centrality measures correspond to changes within a 1200 m metric radius. The output of space syntax saved in the attribute table with NACH and NAIN was examined through graphical representation using spatial maps. These analyses provided an understanding of the accessibility level of the street network at the macro level.

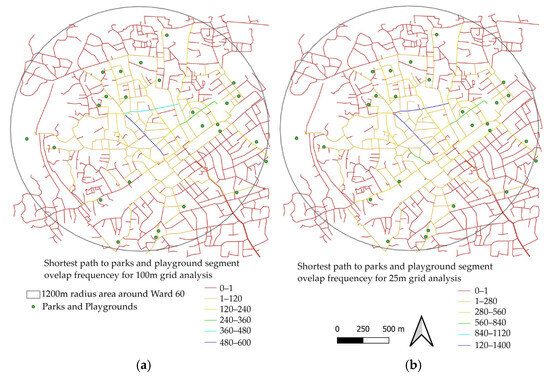

2.7. OD Matrix Shortest Path to Park and Playground Segments Overlap Frequency

The OD matrix, generated using the OSMnx method and the pedestrian network, produces a shortest path matrix for each pair of origin and destination points. When using the accessibility assessment method by OSMnx, the shortest path OD matrix output was generated using walking as the transportation mode, having output columns in for segment length, osmid, and segment id in the attribute table, which correlate with the NAINr = 1200 m and NACHr = 1200 m columns of the space syntax attribute table. Therefore, the details of the segments (length, osmid, seg id) for each pair of OD shortest path journeys were computed, which provided the details of particular segments that were repeatedly used in each pair of ODs, along with their number of repetitions in the overall OD matrix. The remaining segment IDs of the road network were excluded from analysis, as they are not part of the shortest path OD matrix, and were assigned a ‘0’ segment overlap frequency. This data, further sorted using ‘R’ software, shows how many times a particular segment overlapped in the OD matrix pairs for 25 m and 100 m grid sizes. Accordingly, the segment overlapping data for 25 m and 100 m grid size were plotted on QGIS maps for further analysis.

The comparative analysis of accessibility to parks and playgrounds in a mixed-use neighborhood was conducted using three open-source software tools: QGIS, OSMnx, and space syntax. The evaluation considered multiple attributes, including methodological approaches, accessibility across different transportation modes, origin–destination path calculation techniques, spatial grid variations, interface and usability, as well as the ability to compute centrality in OSMnx and integration and choice in space syntax. The detailed results of this comparative assessment are presented in Section 3.

3. Results and Discussion

The findings of the comparative analysis of accessibility assessment values for Ward 60 are presented, with a detailed analysis in the subsequent subsections. These subsections cover the accessibility assessments by the QGIS and OSMnx methods executed for all six transportation modes to parks and playgrounds, used as the destination types for both 25 m and 100 m grid size assessments. The aggregated value of the weighted counts of the parks and playgrounds accessible within each travel-time zone determined the accessibility assessment value at each grid. The measurement of the spatial accessibility of public service facilities needs to select an appropriate set of accessibility evaluation parameters according to the specific spatial area and needs to adopt appropriate measurement methods to expand the measurement [76]. The assessment produced an accessibility value for every grid area and was subsequently spatially visualized on the neighborhood map. Similarly, the NAIN and NACH values of space syntax are compared with the shortest path overlap frequency and centrality analysis generated by OSMnx.

3.1. Method-Wise Comparison of Accessibility Assessments by QGIS and OSMnx

In this manuscript, Section 2.4.1 and Section 2.4.2 describe the OD matrix shortest path extraction methodology for accessibility assessments using both QGIS and OSMnx. In QGIS, the OD matrix shortest paths are extracted as a single shapefile, which can be directly visualized on the map. The distance of each shortest path can be obtained from the attribute table of the shapefile. In contrast, OSMnx generates detailed outputs for each shortest path pair, including segment IDs and corresponding lengths for all traversed segments. The graphical representation of the OD matrix in OSMnx is produced separately through the execution of the respective code script.

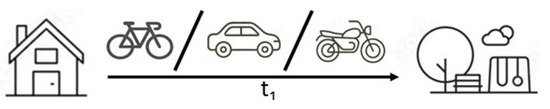

3.1.1. The Role of the Nearest Node in Shortest Path Calculation

OSMnx identifies the nearest node on the road network to which an origin or destination point is snapped in order to generate the shortest path, as shown in Figure 8a,b. If the nearest node is located at a considerable distance on the surrounding network, the resulting shortest path is adjusted accordingly, which may introduce deviations in the shortest path. In contrast, QGIS snaps the origin or destination perpendicular to the nearest segment of the road network, thereby minimizing deviations and reducing the extent of modification in the generated shortest path, as shown in Figure 8c,d.

Figure 8.

(a) Red dots indicate the nearest nodes for the 25 m grid origin points. (b) The nearest nodes for the 100 m grid origin points in OSMnx; (c) 253 grid points snapped to their nearest network; and (d) 18 grid points snapped to their nearest network in QGIS.

The difference observed across OSMnx and QGIS tools stems primarily from their underlying analytical mechanisms. QGIS computes distance-based network routes, emphasizing geometric precision, while OSMnx applies topological graph-based calculations that capture connectivity strength and node centrality.

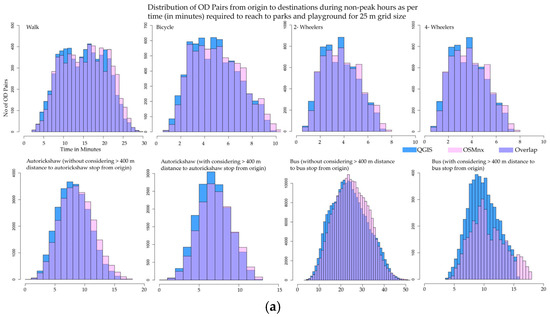

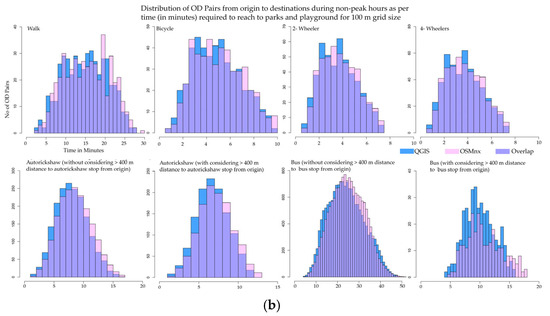

3.1.2. Distribution of Number of OD Pairs from Origin to Destination Accessible Within Time

Section 2.4.1 and Section 2.4.2 of the manuscript detail the computation of OD matrix shortest paths to parks and playgrounds using two methodologies: QGIS and OSMnx. Both methods account for access across all modes of transportation. A subsequent analysis of OD pairs disaggregated by peak and non-peak hours and by spatial resolutions of 25 m and 100 m grids was performed using the ‘R’ programming language, with visualizations generated via the ‘ggplot2’ package. This graphical analysis is critical for evaluating variations in accessibility levels as influenced by transport mode, peak and non-peak hours, grid resolution, and computational method (QGIS vs. OSMnx), as shown in Figure 9a,b. It facilitates the interpretation of spatial accessibility patterns and helps identify the underlying causes of higher or lower accessibility across different scenarios. The x-axis denotes the travel time in minutes required to reach parks and playgrounds for OD pairs, while the y-axis indicates the number of OD pairs corresponding to each time interval. In these graphs, the distribution of OD pairs across time intervals highlights temporal variability in accessibility, blue bars represent the number of OD pairs in particular travel times estimated using the QGIS method, while pink bars correspond to OSMnx-derived estimates. The number of OD pairs in particular time overlaps for both methods (QGIS and OSMnx) is shown in purple color. The maximum overlap shows the degree of consistency between the two computational approaches by QGIS and OSMnx.

Figure 9.

OD pairs distribution within the time scale by all transportation modes from origin points to destinations (parks and playgrounds) by QGIS and OSMnx methods for non-peak hours: (a) for the 25 m grid, and (b) for the 100 m grid.

The OD matrix analysis for the walking mode, conducted using both QGIS and OSMnx, yielded comparable results, with a high degree of spatial overlap of the number of OD pairs, and the analysis indicates that the maximum time required to access parks and playgrounds within a 1200 m radius around Ward 60 is approximately 30 min. A majority of walking OD pairs fall within the travel time range of more than 10 min to 25 min, highlighting relatively low spatial accessibility by walking.

In contrast, the bicycle mode enables access to parks and playgrounds within 10 min, while motorized modes such as 2Ws and 4Ws require less than 8 min for the same trips, indicating higher levels of accessibility. For public transport modes, specifically autorickshaws and buses, as detailed in Section 2.3.5, a threshold condition was applied, wherein origin points located more than 400 m from the nearest stop were classified as inaccessible. This constraint resulted in the exclusion of a substantial number of OD pairs from the accessibility assessment, thereby significantly influencing the final outcome of accessibility via these modes. To evaluate the impact of this 400 m accessibility condition, separate OD matrix graphs were generated for the autorickshaw and bus modes—both with and without the 400 m threshold applied. A comparison of these graphs reveals a marked reduction in the number of OD pairs considered under the constrained condition, underscoring the sensitivity of public transport accessibility assessments to bus and autorickshaw stop proximity criteria in both the QGIS and OSMnx methods of assessment. The graph, with consideration of the 400 m distance to a bus stop, shows a lower number of OD pairs for OSMnx in the time range of 5 to 15 min compared to OSMnx. Additionally, the OSMnx has OD pairs within a more than 15minute zone, which further reduces overall accessibility by OSMnx.

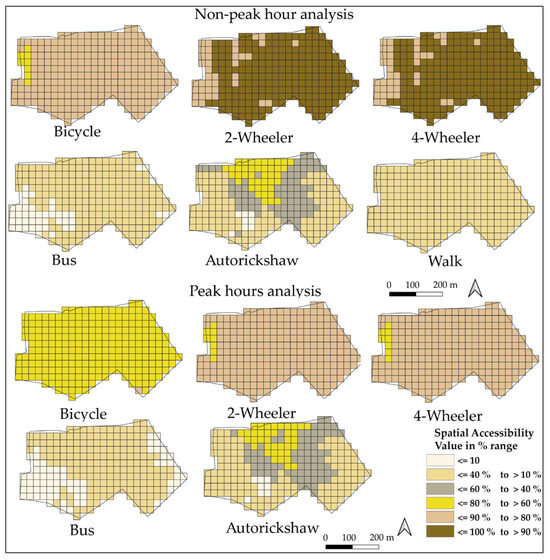

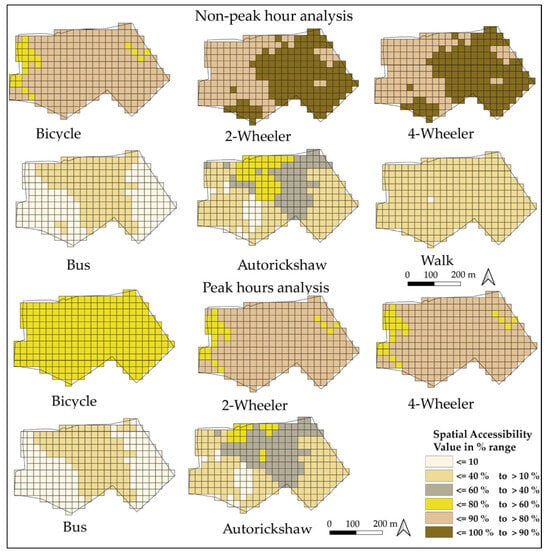

3.2. Systematic Comparison of Accessibility Assessment of Parks and Playgrounds for 25 m and 100 m Grid Sizes Using Each Mode of Transportation (Mode-Wise Spatially Represented) Through QGIS

The spatial analysis was conducted using 25 m and 100 m grid divisions of the neighborhood area. Each grid cell was assigned an accessibility score ranging from 10% to 100%, derived from the adopted accessibility assessment methodology. For analytical clarity and representation in the map, accessibility scores were classified into the following ranges: ≤10%, >10–40%, >40–60%, >60–80%, >80–90%, and >90–100%. The spatial distribution of accessibility across the grids was then mapped, and the proportion of spatial area falling within each accessibility range was calculated.

Figure 10 and Figure 11 present a comparative evaluation of the accessibility outcomes obtained using QGIS for six modes of transportation, under both peak- and non-peak-hour conditions for 25 m and 100 m grids, respectively. From Figure 10 and Figure 11, it is observed that the spatial patterns of accessibility values for walking, bicycling, two-wheelers, and four-wheelers (during peak hours) fall within similar accessibility ranges across the neighborhood in the case of both 25 m and 100 m grid sizes. In the case of a personalized mode, the accessibility assessment results were dependent on the spatial layout of the neighborhood and the proximity of buildings to the main vehicular road. Higher accessibility by a personalized mode indicates a more permeable road network of Ward 60 and the surrounding 1200 m radius area. In contrast, mixed-mode transport options, such as buses and autorickshaws, display greater spatial variation in accessibility values. This variation arises because accessibility to bus and autorickshaw services is dependent on the proximity of origin points to their respective stops, resulting in heterogeneous accessibility outcomes across the study area for both 25 m and 100 m grid size accessibility assessments.

Figure 10.

Spatial representation of accessibility assessments of parks and playgrounds in percentage using all modes of transportation, considering peak and non-peak hours, for a 25 m grid, evaluated by QGIS.

Figure 11.

Spatial representation of accessibility assessments of parks and playgrounds in percentage using all modes of transportation, considering peak and non-peak hours, for a 100 m grid size, evaluated by QGIS.

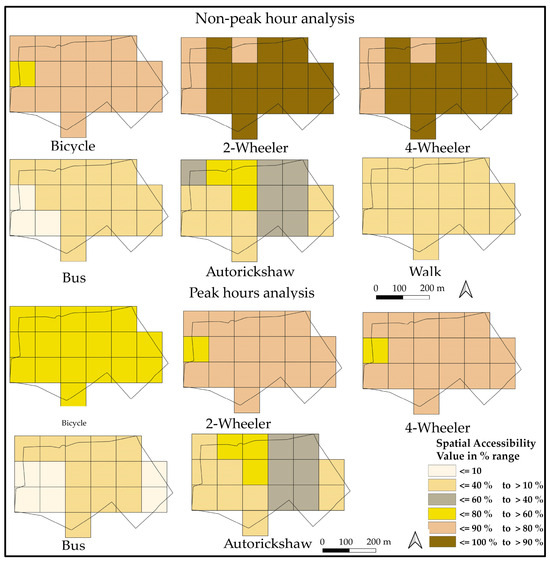

3.3. Systematic Comparison of Accessibility Assessment of Parks and Playgrounds for 25 m and 100 m Grid Sizes Using Each Mode of Transportation (Mode-Wise Spatially Represented) Through OSMnx

Figure 12 and Figure 13 present a comparative evaluation of the accessibility outcomes obtained using OSMnx for six modes of transportation, under both peak- and non-peak-hour conditions for 25 m and 100 m grids, respectively. From Figure 12 and Figure 13, it is observed that the spatial patterns of accessibility values for walking, bicycling, two-wheelers, and four-wheelers (during peak hours) fall within similar accessibility ranges across the neighborhood in the case of both a 25 m and a 100 m grid size.

Figure 12.

Spatial representation of accessibility of parks and playgrounds in percentage using all modes of transportation, considering peak and non-peak hours, for 25 m and 100 m grids, respectively, evaluated by OSMnx.

Figure 13.

Spatial representation of accessibility of parks and playgrounds in percentage using all modes of transportation, considering peak and non-peak hours, for 100 m grids, evaluated by OSMnx.

In the case of OSMnx, grid size variation affects the accessibility assessment values. As shown in Figure 8a, the maximum number of nearest nodes is taken into consideration in the 25 m grid assessment but it is not in the 100 m grid assessment, as shown in Figure 8a. The 25 m grid provided for the exploration of the maximum road network in the shortest path calculation. While for a 100 m grid analysis, the shortest path passes through a few nodes, as shown in Figure 8b.

The spatial variation analysis in Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13 indicates that variation in grid size has minimal influence in larger-area assessments. However, at the neighborhood scale, grid size plays a more significant role, where a micro-level analysis demonstrates greater accuracy when using finer grids of 25 m. The micro-level accessibility assessment for a 25 m grid size assisted in the analysis of PT and IPT accessibility. Conversely, coarser grids of 100 m or more reduce the precision of the results and may lead to less reliable spatial interpretations. A larger grid size analysis is suitable for city and regional level assessments. OSMnx tends to smooth local variations at a coarser grid resolution (100 m), whereas QGIS preserves finer variations (25 m grid size). These methodological contrasts explain the observed consistency between variable grid size outputs.

3.4. Transportation Mode-Wise Comparison of Accessibility Assessment Values for All Six Modes

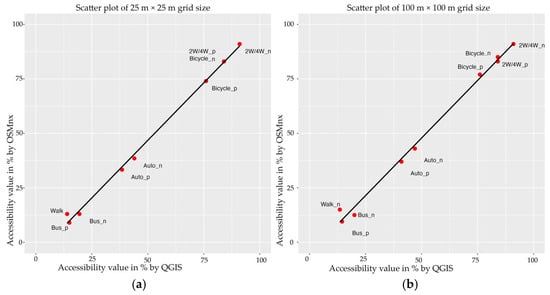

Accessibility varies as per the transportation mode. The comparison of accessibility assessment values by QGI and OSMnx methods for all six transportation modes (walking, bicycling, 2Ws, 4Ws, buses, and autorickshaws) was computed for peak and non-peak hours and compared, as shown in the scatter plots of Figure 14a,b for both 25 m and 100 m grid sizes. The average accessibility values considered all six modes; the comparison of accessibility by both QGIS and OSMnx methods is shown in Figure 14 and in Supplementary Material S5 and Table S6.

Figure 14.

(a,b). Scatter plots of accessibility by QGIS and OSMnx with variable grid sizes. ‘_p’ represents values during peak hours while ‘_n’ represents values during non-peak hours by all transportation modes. (a) Accessibility assessment values in percentage during peak and non-peak hours by QGIS and OSMnx (25 m × 25 m). (b) Accessibility assessment values in percentage during peak and non-peak hours by QGIS and OSMnx (100 m × 100 m).

Walking: The accessibility analysis by walking reveals the lowest values for both OSMnx and QGIS methods. The main reason is that walking speed is the slowest amongst the other modes; also, this outcome can be attributed to the limited number of parks located within a walkable distance. Furthermore, the 1200 m buffer demonstrates a distinct spatial division between the western and eastern parts of the study area, created by the Dombivli railway station and railway track. Since Ward 60 is situated on the western side of the railway station, additional travel time is required to access parks and playgrounds located in the eastern sector, thereby reducing overall walk-based accessibility.

Bus: The lower accessibility by PT (bus) is primarily due to the mixed-mode approach applied in the analysis, which considered walking–bus–walking as the travel sequence. Firstly, walking speed is the slowest among all transportation modes, which increases the travel time required to reach the nearest bus stop compared to the other modes, and secondly, a 400 m threshold was adopted to define walkable access to the nearest bus stop from both origins and destinations. However, not all origin points (grid cells) and destination points (parks and playgrounds) fall within this threshold, resulting in specific origin–destination (OD) pairs having no feasible access to bus stops. Consequently, the accessibility values for these OD pairs are null, which reduces the overall bus-based accessibility for Ward 60. Additionally, only one route caters to Ward 60, which reduces the overall accessibility of bus transportation. The accessibility value obtained by QGIS is higher than OSMnx for both non-peak and peak hours.

Autorickshaw: The accessibility assessment value by autorickshaw is moderate compared to the other transportation modes. Accessibility by autorickshaw involves a mixed-mode assessment, including walking to the autorickshaw stop and then riding the autorickshaw. Thus, the resultant accessibility value was reduced due to a lower walking speed. The variations in accessibility assessment by autorickshaw mode are marginal for both the QGIS and OSMnx methods of assessment.

Two-Wheeler, Four-Wheeler, and Bicycle: The comparative analysis of the OSMnx and QGIS methods for Ward 60 during peak and non-peak hours reveals minimal variation in accessibility values for both 2Ws and 4Ws. There were consistently high levels of bicycle accessibility to parks and playgrounds across both OSMnx and QGIS methods. The observed high value of accessibility can be primarily attributed to the size of the catchment area and the average travel speed of vehicles, and secondarily to the direct door-to-door accessibility provided by personalized motorized transport. Higher values of bicycle accessibility strengthen the potential for developing bicycle-oriented infrastructure, highlighting bicycles as a sustainable transport option. Detailed mode-wise accessibility assessment values from accessibility assessments using QGIS and OSMnx for 25 m and 100 m grid sizes are represented in Supplementary Material S1–S6, as well as Figure 10, Figure 11, Figure 12 and Figure 13.

3.5. The Average Accessibility of Ward 60 Using Both QGIS and OSMnx Methods

The average accessibility values of Ward 60 for a 25 m grid size comprehensively evaluated for 253 grids for each transportation mode considering peak and non-peak hours using GIS and OSMnx are 54.89%, and 52%, respectively. The average accessibility values of Ward 60 for a 100 m grid size comprehensively evaluated for 18 grids evaluated for each transportation mode, considering peak and non-peak hours, using GIS and OSMnx, are 58.67%, and 53.65%, respectively. The average accessibility values considered all six modes; the comparison of accessibility by both the QGIS and OSMnx methods is represented in Supplementary Material S5.

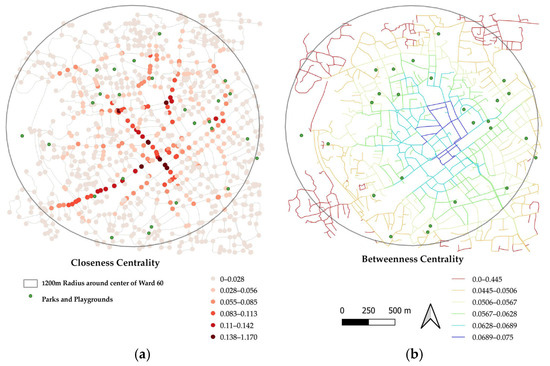

3.6. Closeness Centrality and Between Centrality Results by OSMnx

High centrality justifies major networks as conduits for both pedestrian and vehicular traffic. Closeness centrality for each node is the reciprocal of the sum of the distances from a node (origin) to all reachable nodes (destinations) in the street networks graph, weighted by length [38,77]. The value of closeness centrality for a 1200 m radius around the center of Ward 60 ranges from 0.0 to 0.170.

Betweenness centrality identifies strategically important streets or intersections. High betweenness centrality often points to streets that act as major connectors or “bridges” in the network—which are critical for the flow of traffic, pedestrians, or goods. Losing such links (due to construction or disaster) can cause disproportionate disruption. For a 1200 m radius around Ward 60, the value of betweenness centrality is in the range of 0 to 0.075 as represented in Figure 15a,b. The roads connecting to the railway station, namely Mahatma Phule Road, Ghanashyam Gupte Road, and Dr. Subhash Chandra Bose Road, show the highest betweenness centrality. High-closeness areas tend to have faster average travel times to many destinations. In the present study area, in Ward 60, Pandit Dindayal Upadhyay Road exhibits the highest closeness centrality. This is attributed to its strong nodal connectivity, providing the shortest aggregate distance to all other nodes within the surrounding street network.

Figure 15.

(a) Closeness centrality, and (b) betweenness centrality of Ward 60 and a 1200 m radius around the area by the OSMnx method of centrality assessment.

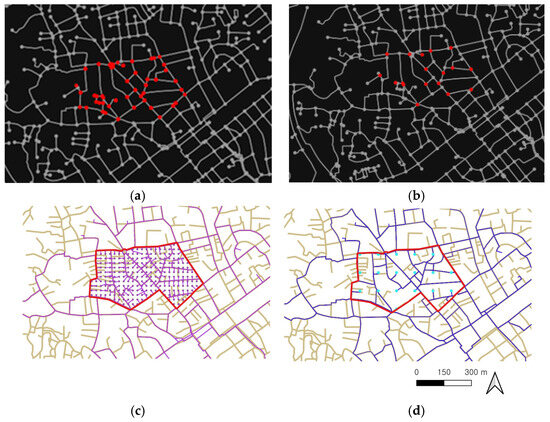

3.7. Angular Segment Analysis Method of Space Syntax (Integration and Choice)

The authors classified the results from the highest level to the lowest level in six variable ranges, as indicated in Figure 16a,b. The correlation of integration and choice values gives accessibility [42,73,75]. To evaluate the accessibility of street networks, the correlation between integration and choice for the 1200 m analysis was generated from the computational value of the attributed table and graphically represented in maps. Figure 16a,b, shows that the integration values are high for the networks along the Dombivli railway station, as the railway station has the highest footfall because it plays a crucial role in city-level and regional-level connectivity. It was observed that the axes with high integration values are on the primary routes accessing the Dombivli suburban railway station. Both the integration and choice values are high, and the pedestrian bridges connecting the Dombivli East and Dombivli West areas within the station have the highest values of integration, indicated in dark blue color. The Manpada road, within a 1200 m area stretch, is further connected to the highway, and other suburban areas beyond the 1200 m radius have the highest integration and choice values. Streets with a high integration value indicate main streets with a higher density of use and activity areas in the city.

Figure 16.

Angular segment analysis method of space syntax: (a) NAINr = 1200 m, and (b) NACHr = 1200 m values around a 1200 m radius from the center of Ward 60.

3.8. Results of Segment Ovelap Frequency: Comparison of OSMnx and Space Syntax

The segment overlap frequency value, calculated by overlapping the OD matrix shortest path output from OSMnx, had the segment IDs of the road segments compared with the similar segment IDs generated in the space syntax output attribute table. The overlap of both is shown in Figure 17a,b.

Figure 17.

(a) Shortest path to parks and playgrounds overlap frequency for 100 m grid area by OSMnx method. (b) Shortest path to parks and playgrounds overlap frequency for 25 m grid area by OSMnx method.

In Figure 15a,b, Figure 16a,b and Figure 17a,b, the values of centralities (closeness and betweenness), NAIN, NACH, and shortest path segment overlap frequency for the 25 m and 100 m grids respectively demonstrate variation according to the respective methods of assessment. To enable comparison across these measures, the authors normalized the values into percentile-based ranges of 1–20, 20–40, 40–60, 60–80, and 80–100%, considering the minimum and maximum observed values. The results were then classified into six ranges from the highest to the lowest level.

The analysis reveals that the highest values of centrality, integration, choice, and segment overlap tend to cluster within the 60–100% range, indicating strong similarities across the methods. Space syntax output is not specifically for certain destination types; while segment overlap frequency was calculated exclusively for parks and playgrounds, it still shows a considerable degree of correspondence with the space syntax outputs. If all land-use destinations had been included in the analysis, it is likely that the differences in similarity ranges would have been further reduced.

The outcome of the accessibility assessment indicates a clear need to implement a Framework for Multi-Modal Accessibility Assessment within the 15-Minute City concept, particularly for neighborhoods in Kalyan Dombivli and other urban areas across Indian cities. For conducting micro-level analyses at a 25 m grid resolution, QGIS emerges as a promising open-source tool that can be effectively integrated with space syntax methods, while OSMnx can be used to process larger datasets. This integrated approach enables detailed spatial accessibility evaluations; however, it remains underexplored within the fields of urban design and planning practice in the Indian urban context.

4. Implication of Urban Planning Policies for Accessibility Assessments

Urban policy must integrate inclusivity and provide physical access for all populations, explicitly accounting for age, gender, disability status, and marginalized groups to foster safety and security universally [78]. The availability of accessibility-enhancing infrastructure, including ramps, staircases, and pedestrian bridges within the transportation network, is crucial for guaranteeing universal access, particularly for vulnerable segments of the population. The micro-level methodology adopted in this research surpasses static spatial analysis by incorporating temporal travel factors, thus enabling a more dynamic and practical perspective on accessibility. Evaluating trip duration (in minutes) is an essential measure of a transportation system’s overall effectiveness [79].

The findings of the accessibility assessment of Ward 60 underscore the need for targeted strategic planning to enhance connectivity for all transportation modes, ensuring equitable and efficient access to green urban infrastructure. Micro-level accessibility assessment policies at the ward level can be framed within the broader paradigm of city- and regional-level accessibility assessment policies. Such interventions should focus on integrating new parks and playgrounds within the existing urban context, optimizing the mixed-land fabric, implementing specific infrastructural improvements for green mobility, integrating IPT, strengthening PT, optimizing routes, and adopting tailored urban mobility strategies to improve accessibility outcomes for all neighborhood residents.

Green mobility and IPT as the convenient mode: A primary driver in encouraging bicycle usage is the provision of necessary safety measures; hence, the establishment of dedicated cycling lanes and open streets is essential [29]. There is an urgent need to enhance bicycle infrastructure to promote low-carbon mobility and healthier urban environments. The results also show that IPT has substantial potential for last-mile connectivity for households. Addressing the challenges faced by IPT services is thus a critical priority. The analysis reveals that parks and playgrounds are most accessible using bicycles and two-wheelers, with rates reaching up to 90%. As motorized two-wheelers are highly accessible, shifting towards low-carbon alternatives such as electric bicycles (e-bikes), e-bike rental systems, and electric rickshaws can play a significant role in advancing sustainable urban mobility goals and reducing emissions.

Overlook the role of PT: The accessibility of PT via buses to all destination types in Ward 60 is relatively low compared to other transportation options. The buses serving Ward 60 operate at intervals of 58 min; as a result, the passengers at each bus stop experience a waiting time exceeding 15 min. This limited frequency has contributed to a reduction in the accessibility values, as enhanced PT results in reduced travel times in high-density urban environments. This analysis demonstrates that transportation accessibility can be significantly improved through targeted policy actions. In particular, it advocates for the enhancement of intercity bus networks by increasing operational frequencies and introducing additional routes designed to match the accessibility requirements of multiple neighborhoods, which need to be determined by a detailed accessibility analysis of multiple neighborhoods.

Parks and playgrounds and Mixed land-use planning Assessing the accessibility of Ward 60 to parks and playgrounds is crucial for directing the placement and distribution of new parks and playgrounds. The accessibility analysis aids in pinpointing suitable sites for parks and playgrounds within or adjacent to existing neighborhoods. Where the development of new parks and playgrounds involves private land, policy tools like development incentives or increased Floor Space Index (FSI) allocations can be employed to facilitate the development of accessible public green spaces. The movement from traditional mixed-use planning practices to zoning-based regulations in India has facilitated urban sprawl and reduced overall accessibility. Conversely, western urban planning approaches prioritize fine-grain mixed land use, which supports greater neighborhood vitality and accessibility. Despite these policy goals remaining largely unrealized, New Delhi’s master plan has adopted mixed-use development principles, while most Indian cities have not formally established similar policies. Advancing the effective application of mixed-use development throughout Indian cities will depend on the integrated use of related urban policies, which is key to enhancing urban accessibility and supporting wider sustainability objectives [80]. Ward 60 is characterized by a high population density. The current proportion of mixed-use areas should be reassessed to adequately accommodate the population’s needs within the ward and its surrounding areas.

Central governance policies implementation at the local level: While Indian policies and guidelines establish a comprehensive macro-level basis for enhancing accessibility, their on-ground implementation at the local level remains insufficient. Evaluating accessibility at the neighborhood or ward scale using the 15 MC framework provides an effective micro-scale assessment tool, directly addressing the constraints at the policy operationalization level [35]. This approach facilitates the localization of national policies and uncovers context-specific barriers and opportunities in advancing sustainable urban mobility.

To ensure these research findings inform practical urban planning, it is crucial to integrate accessibility assessment techniques grounded in the 15 MC within the SusTAIN framework or as part of ward-level transportation strategies. Such incorporation could become a fundamental aspect of municipal corporation administrative policies, contributing to a more structured and sustainability-driven approach to urban mobility.