Abstract

Urban Digital Twins (UDTs) demand both simplified geometry and rich semantic information from Building Information Models (BIM) to be effectively integrated into Geospatial Information Systems (GIS). However, current BIM-to-GIS conversion methods struggle with geometric complexity and semantic loss, particularly at scale. This paper proposes a novel, scalable methodology for comprehensive BIM/GIS integration, addressing both geometric and semantic challenges. The approach introduces a geometry conversion workflow that transforms solid BIMs into valid, simplified CityGML representations through a level-by-level detection of building elements and outer surface extraction. To preserve semantic richness, all entities, attributes, and relationships—including implicit connections—are automatically extracted and stored in a Labeled Property Graph (LPG) database. The method is further extended with a new CityGML Application Domain Extension (ADE) that supports Multi-LoD4 representations, enabling selective interior visualization and efficient rendering. A web-based urban digital twin platform demonstrates the integration, allowing dynamic semantic querying and scalable 3D visualization. Results show a significant reduction in geometric complexity, full semantic retention, and robust performance in visualization and querying, offering a practical pathway for advanced UDT development.

1. Introduction

With advancements in technology and the growing focus on developing urban digital twins for smart cities, the integration of Building Information Models (BIM) and Geospatial Information Systems (GIS) has attracted significant attention from researchers. This integration offers numerous applications and advantages within the Architecture, Engineering, and Construction (AEC) industry as well as geospatial disciplines. It allows for the combination of building information with geographic data, enabling the visualization and analysis of both physical and spatial features of a given area. This integration also supports advanced spatial analysis to support urban planning, manage existing infrastructure, and assess the effects of new developments on a specific location. By bringing together the strengths of both systems, their combined benefits can be more effectively utilized, particularly in urban digital twins [1,2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10].

To facilitate BIM/GIS data integration, a wide range of studies have been conducted. The common approach to integrating BIM and GIS involves using building information within GIS platforms, as each system has different strengths. In this integration process, BIM typically serves as the source of information, while GIS is used for data processing and analysis, which requires the conversion of BIM data. This conversion involves two main aspects: geometry and semantics. Geometric data describe the modeled object’s size, shape, position, and orientation, while semantic data include extra details such as attributes, relationships, and properties—also known as non-geometric information. Because these two data types are fundamentally different, they must be handled independently during the integration process yet to maintain the link between them. Despite significant progress in geometric and semantic areas, several challenges and complexities still hinder the seamless integration of BIM and GIS. These challenges largely stem from fundamental differences between the two domains [11,12,13,14].

Integrating BIM and GIS remains inherently complex due to persistent challenges in managing both geometric and semantic data. On the geometric side, previous studies mainly focused on converting BIM data into GIS formats without addressing geometric complexity reduction. The complex geometry in urban digital twins negatively impacts the performance of 3D city models, particularly in terms of storage, rendering, and visualization. The conversion process from Industry Foundation Classes (IFC) to CityGML mainly involves transforming solid models in IFC into surface models in CityGML. For instance, an exterior wall in IFC is modeled as a solid object, whereas in CityGML, the exterior wall is represented without “thickness” and should be modeled as a surface [15]. Several studies have focused on extracting the building envelope to address this issue. Nevertheless, the following limitations persist: (1) the methods are not suitable for complex buildings [16], (2) they are not scalable for large-scale projects, such as city-wide 3D modeling [17], (3) the processes are time-consuming, (4) the use of complex algorithms makes the transformation error-prone [18,19,20], and (5) there is often a lack of clarity on whether only the outer surface of a building is extracted or if exterior elements are visualized as solid or multi-surface objects [14,18].

In the context of urban digital twins (UDTs), managing model complexity has become increasingly important. In this context, the concept of Level of Detail (LoD) in the CityGML data model has been widely adopted to manage model complexity during BIM-to-GIS conversion. While previous studies have primarily focused on converting IFC models into LoD1, LoD2, and LoD3, limited research has explored the representation of interior building components at LoD4 [15]. Furthermore, attempts to convert complex multi-level buildings into LoD4 representations are often impractical due to the high volume of interior elements and associated performance limitations. Although LoD conversion has addressed surface model simplification [21], simplifying solid BIM remains particularly challenging due to differences in geometric structure and the lack of methods tailored for solids. Existing approaches are also heavily reliant on the availability of semantic information, which is not always guaranteed in IFC data [14].

On the semantic side, the full transfer of information remains an unresolved issue. Many studies and tools fail to preserve the rich semantic content of BIM, such as detailed attributes, object hierarchies, and explicit and implicit relationships. This loss of information is caused by differences in data standards, modeling purposes, and the lack of unified schemas between BIM and GIS. However, for applications such as urban digital twins, access to complete semantic information is essential for enabling meaningful analysis, simulation, and decision-making. To address this, several strategies have emerged. Class mapping requires extensive domain knowledge and often results in partial or lossy translations, since CityGML supports only a subset of IFC [14]. Efforts to improve mapping efficiency include linguistic and text-mining methods [22,23], which help generate candidate correspondences but still struggle with concepts that have dissimilar names (e.g., IFC “Space” vs. CityGML “Room”). To extend CityGML, Application Domain Extensions (ADEs) have been widely adopted for domains such as noise mapping, indoor navigation, and energy analysis [24,25]. While ADEs enrich the schema, they also increase complexity and cannot fully replace the richness of IFC. In summary, although these strategies offer progress, none have achieved complete and lossless semantic transfer. This gap underscores the need for methods capable of preserving the full semantic richness of IFC data while maintaining interoperability in GIS and Urban Digital Twins [15,26].

Addressing these limitations in IFC-to-CityGML conversion is crucial for improving BIM/GIS integration. Accurately defining LoDs can simplify the geometry of converted models, reduce complexity, and improve performance in terms of visualization, storage, and rendering—particularly for large-scale projects like city-wide 3D modeling. This paper proposes a novel approach to efficiently address these geometric challenges. Our method involves detecting and categorizing building elements level-by-level—even in the absence of semantic metadata, extracting the solid geometry of necessary building elements, detecting external surfaces, and converting them into CityGML format. The resulting CityGML model is simplified in terms of geometry and requires less storage space compared to traditionally converted models, thus significantly advancing BIM and GIS integration to support large-scale smart city development. To further improve scalability, we extend CityGML through an ADE that introduces a Multi-LoD4 concept, allowing users to selectively visualize internal building elements per level. This not only supports performance-efficient visualization of multi-story buildings but also enables the storage of simplified external surface and internal solid models even in the absence of rich semantic data. It also establishes a robust linkage between simplified geometry and semantic information, laying the foundation for scalable and query-able BIM/GIS integration within urban digital twin environments. Regarding the semantic information, this paper presents an approach to efficiently transfer all existing semantic information of IFC data into a graph database which can be retrieved easily through the developed integrated platform for urban digital twins.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows: Section 2 reviews related work on BIM and GIS integration. Section 3 describes the proposed methodology, including the data preparation, transformation processes, and integration framework. Section 4 presents the case study and experimental results. Section 5 discusses the findings and limitations of the approach. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper and outlines directions for future research.

2. Related Work

2.1. BIM and GIS Integration

The integration of BIM and GIS has been widely explored in the literature, with significant progress made over the years. Various approaches have been proposed to bridge the gap between these two domains, and one of the most common ways to classify them is by grouping them into three levels: data level, process level, and application level [1]. At the data level, integration typically involves creating new standards, updating existing ones, or converting data formats between BIM and GIS [14]. The process level focuses on connecting BIM and GIS workflows without altering the original data formats or structures—both systems remain active and operate independently. Since BIM and GIS have different data structures and contents—with BIM usually containing more detailed information—a reference ontology can be used to represent and align these differences. Reference ontologies are not entirely new but are built by extending general-purpose ontologies to provide a broader view across multiple domains [27]. The application level refers to methods that do not involve changes to the source or target data, nor do they introduce new services or ontologies. Instead, these integrations are usually designed for specific use cases, where BIM and GIS data are used together to support a particular application without deeply modifying the systems themselves [15,28].

At the data level, BIM/GIS integration focuses on bridging the data gap caused by differences in their data schemas. This usually involves converting data so that information from one system can be used effectively in the other. There are three common patterns for this kind of data conversion: from GIS to BIM, from BIM to GIS, and from both systems to a third platform. Among these, the BIM-to-GIS approach is the most widely used. It involves converting both the geometric and semantic information from BIM into formats that can be used in a GIS environment, such as in IFC-to-CityGML transformations. This method aligns with the strengths of each system: BIM excels at creating detailed building data, while GIS is better suited for managing and analyzing spatial information [12,27,29,30,31,32]. The GIS-to-BIM approach, on the other hand, is less common and more challenging. For example, converting CityGML to IFC often requires approximating solid models from surface geometries using basic extrusion techniques. These conversions usually lack accurate information about thickness and other detailed attributes [15]. Furthermore, matching the geometric representations used in IFC (such as swept solid, constructive solid, or boundary representations) with those in CityGML is technically complex [33]. The third approach, BIM/GIS-to-others, involves integrating both BIM and GIS data into a new, unified system. An example of this is the Unified Building Model (UBM), which uses an ontology-based framework to capture concepts and relationships from both domains. This model acts as a neutral format that enables bidirectional data exchange between BIM and GIS [34,35,36].

Overall, the BIM-to-GIS method remains the dominant integration pathway, largely because it reflects the typical use of BIM for data creation and GIS for data analysis and management. The main tasks involved in BIM-to-GIS integration are geometric conversion and semantic mapping. IFC and CityGML are the leading international standards in the AEC industry and the geospatial domain, respectively. IFC, developed by buildingSMART, is an open data model designed to support information sharing within the AEC industry. CityGML, on the other hand, is an international standard created by the Open Geospatial Consortium (OGC) for modeling, representing, and sharing 3D virtual city models. The conversion from IFC to CityGML is currently the most common method for data-level integration between BIM and GIS [14,15]. In this paper, we primarily contribute at the data level by proposing a solid-to-surface IFC-to-CityGML conversion and an ADE for Multi-LoD4, and we bridge toward the application level through a graph-backed linkage that enables semantic querying within an urban digital twin.

2.2. Geometry Data Conversion

Geometric conversion is a core task in the integration of BIM and GIS, required due to the fundamentally different modeling paradigms used by the two systems [14]. BIM typically employs detailed, object-based solid models, while GIS generally relies on surface-based representations suitable for spatial analysis. As a result, converting geometry between these systems involves several important tasks, including representation conversion, coordinate system transformation, geo-referencing, representation transformation (solid-to-surface), and LoD mapping [15]. Regarding the geometry conversion, this paper will focus on representation transformation and LoD mapping.

Representation transformation, particularly solid-to-surface conversion, remains a major unresolved challenge. Many conversions still produce CityGML outputs with solid characteristics or retain non-exterior faces [14,18,37]. Ref. [16] generalized CityGML LoD3 buildings to reduce size by extracting the shell, simplifying facades, aggregating polygons and typifying windows. The approach effectively reduced storage requirements by over 90% while retaining semantic fidelity. However, the method is interactive, operates on CityGML rather than IFC, and struggles with non-convex shapes or high-rise buildings, which cannot be useful in IFC-to-CityGML surface problem [16]. Moving from CityGML generalization to IFC-to-CityGML conversion, Ref. [18] proposed an IFC-to-CityGML LoD3 workflow with three steps: (1) semantic filtering and mapping, (2) geometric transformation to extract the building envelope, and (3) refinement using morphological closing to obtain 2-manifold surfaces. The approach generated valid LoD3 models on multiple datasets. Limitations include dependence on rich IFC semantics (e.g., difficulty with balconies and dormers due to missing dedicated classes), potential artifacts from closing, lack of interior handling, support restricted to B-Rep/CSG, and a focus on envelope extraction rather than a strict outermost-surface conversion.

Ref. [17] developed a bidirectional IFC and CityGML framework for using schema mediation and instance-based comparison by introducing a Semantic City Model reference ontology. It handles B-Rep, Swept Solid, and CSG geometries, coordinate systems, and LoD1-LoD4 transformations, and supports CityGML ADEs for semantic enrichment. Limitations are a time-consuming, instance-based workflow that depends on well-structured IFC files, non-exterior solid-to-surface conversion (retaining interior faces and larger outputs), incomplete coverage of all IFC geometry types, gaps in semantic mapping that may cause data loss. Focusing on speed rather than ontology mediation, Ref. [19] introduced a multiprocessing-based Screen-Buffer Scanning (SB-MP) method to accelerate IFC-to-CityGML LoD generation. Exterior surfaces are detected using SB scanning combined with semantic mapping rules, followed by automatic LoD generation, yielding faster runtime than traditional Even–Odd Rule (EOR)-based methods. However, the approach is unidirectional, omit property/relationship mapping, lacks an accuracy benchmark, is sensitive to virtual-camera settings, is not a strict solid to surface conversion (risk of oversimplification), and reports support primarily for B-Rep geometry.

Complementary to the above IFC-to-CityGML approaches, visibility-based techniques optimize rendering by culling interior faces from multiple viewpoints. Ref. [20] proposed OutDet, a visibility-based filter that keeps only externally visible triangles from multiple viewpoints (triangle mesh + view-frustum projection + visibility testing). Empirical evaluations showed significant reductions in the number of features rendered (up to 96% for decoration models), and increased visualization performance (up to 1.7× speed improvement). However, the method is view-dependent filtering mechanism rather than geometric conversion: the underlying solids are not transformed to surface, no IFC-to-CityGML output is produced, results can miss exterior features depending on viewpoint selection, and IFC relationships/semantics are not preserved. As such, OutDet is effective for rendering but limited for BIM→GIS integration.

Despite the progress made in previous studies, several key issues in geometry conversion between BIM and GIS remain unresolved. Most notably, the challenge of robust solid-to-surface transformation has not been fully achieved, with many methods either oversimplifying the geometry or failing to extract only the outermost surfaces. In addition, the reliance on specific geometry types (e.g., B-Rep), limited support for complex or high-rise structures, and the lack of consideration for internal elements or semantic coherence significantly constrain the effectiveness of current approaches. Furthermore, some methods operate more as visualization filters than true geometric transformers, and few offer fully automated solutions with minimal data loss. To address these gaps, this paper focuses on developing a solid-to-surface conversion method that extracts only the outer surfaces of IFC-based BIM, while preserving essential geometric integrity and supporting LoD mapping. By targeting the geometric transformation process directly, this work aims to produce surface-based representations that are semantically meaningful and structurally valid for integration into GIS environments.

2.3. Semantic Data Conversion

Semantic mapping is the process of aligning object types, attributes, and relationships between the BIM and GIS domains, specifically between IFC and CityGML. Both IFC and CityGML define data models with classes, attributes, and relationships, but they are built on different technologies—IFC uses the EXPRESS modeling language, while CityGML is based on XML. As a result, semantic mapping requires parsing and interpreting both schemas with tools that can recognize their syntax and structure [15]. Semantic mapping can be broken down into three main components: class mapping, attribute mapping, and relationship mapping [14,15].

- Class mapping involves identifying how IFC entities correspond to CityGML classes. While IFC4 includes around 800 classes, only a small subset—roughly 60–70—are relevant for geospatial applications, and as few as 17 have been found to have direct equivalents in CityGML [24]. Class mapping can occur in three ways:

- ○

- One-to-one mapping, such as IfcWindow to Window;

- ○

- One-to-many or many-to-one mapping, like IfcSlab, which can map to OuterFloorSurface, WallSurface, or OuterCeilingSurface depending on orientation;

- ○

- Indirect mapping requires geometric interpretation before a mapping decision can be made [15,38].

- Attribute mapping ensures that important properties (e.g., material, thickness) in IFC are transferred to corresponding fields in CityGML entities. For example, when converting IfcWindow, attributes such as its size or material must be mapped to the Window entity in CityGML so that semantic richness is retained in the resulting model [15].

- Relationship mapping involves transferring connections between objects. In IFC, a window may be linked to a wall or an opening element. These connections should be preserved when translated to CityGML so that spatial and structural relationships are not lost [39]. If CityGML lacks equivalent relationship constructs, the Generics module or ADEs can be used to store this extra information [15].

Despite various attempts, complete semantic mapping between IFC and CityGML has not been achieved. A major challenge lies in the semantic mismatch: IFC offers far more detailed and numerous building-related concepts than CityGML, which limits the completeness of translation between the two formats [14,40]. This mismatch reduces the accuracy and effectiveness of data exchange.

Regarding the use of graph technologies for BIM/GIS integration, current methods for converting IFC data into labeled property graphs are largely project-specific and lack generality. Previous approaches have focused on applying graph algorithms to solve domain-specific problems, rather than building comprehensive graph-based representations of IFC data. To support semantic-rich integration, there is a clear need for a generic and fully automatic graph generation method that can represent all semantic information embedded in the IFC model. This paper addresses this gap by proposing a fully automatic approach for generating labeled property graphs (LPGs) from IFC files, capturing the complete semantic content of the original data. The proposed method is explained in detail in the following sections.

3. Methodology

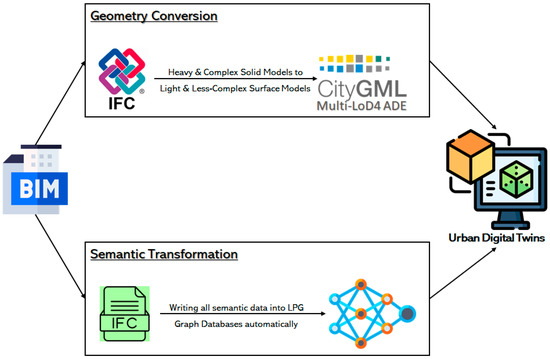

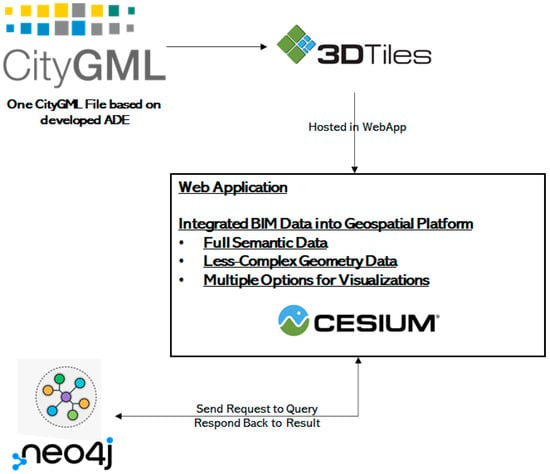

This section outlines the methodological framework adopted in this study to integrate the less-complex geometry of BIM into GIS while keeping full access to all semantic information of the BIM model at the data level. This study introduces (1) a geometry-driven algorithm that extracts only the true exterior surfaces from IFC solids to produce valid LoD3 CityGML (not envelope approximation or view-dependent filtering), (2) a Multi-LoD4 ADE that enables level-selective interior visualization while keeping the core schema intact, and (3) a fully automatic IFC to LPG converter that stores all IFC entities (root and non-root) and all explicit relationships, links every CityGML object to its IFC GlobalId, and supports on-demand inference of implicit relationships for semantic queries. The rest of this section mainly focuses on investigating the proposed methodology for each part. The overview of the methodology is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The overview of methodology which includes geometry conversion, semantic transformation, and visualization in urban digital twin.

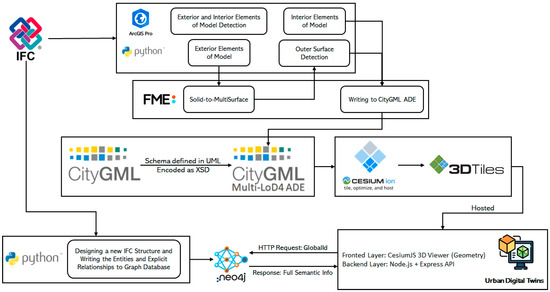

3.1. Geometry Conversion Workflow

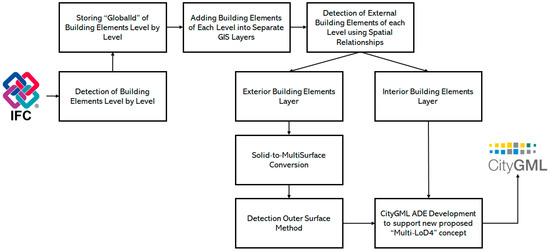

This section presents a geometry conversion workflow that transforms IFC solid models into valid CityGML LoD3 surface models. The workflow explicitly extracts the true exterior faces of building elements to produce less complex geometry suitable for GIS. In addition, we automatically identify interior elements for each building level without relying on IFC semantic labels by evaluating spatial relationships using GIS analyses. We define a Multi-LoD4 concept that organizes interior content by levels and enables selective activation of level-specific interiors during visualization and analysis. A CityGML ADE is used to support Multi-LoD4 concept and facilitates the full semantic access by providing required attributes. Figure 2 shows the details of the methodology for conversion of geometry from BIM.

Figure 2.

The overview of methodology to convert geometry of BIM into new CityGML ADE with support of Multi-LoD4 concept.

3.1.1. Level-by-Level Element Detection

To enable efficient processing of high-rise and complex building models in urban digital twins, our workflow decomposes BIM data into level-specific subsets prior to geometry conversion. This segmentation leverages the hierarchical structure inherent in IFC models, enabling systematic detection of elements for each building levels. Using the IfcOpenShell library, it supports a function to find the container element of a given IFC model. This is particularly useful when we are traversing the IFC spatial structure of to identify the container element of each component and map it to its corresponding building level. For every detected element, the associated GlobalID is extracted and stored in level-specific tables, ensuring a structured link between geometry and semantic references. This level-by-level organization not only supports targeted geometry conversion and analysis but also optimizes subsequent processing tasks by reducing complexity and improving spatial querying efficiency.

3.1.2. External Building Element Detection

Building elements from the model are first imported into a spatial database, specifically a geodatabase in ArcGIS Pro 3.5.3, with each element type stored as a distinct Multipatch layer. These elements are grouped according to corresponding building level while keeping their original 3D geometry, and are concurrently converted into 2D footprints to facilitate spatial analysis. Floor slabs are preprocessed by closing openings (e.g., staircases, elevator shafts) using geometric merging and surface repair operations. External building elements are identified exclusively through spatial relationship analysis, without relying on IFC semantic labels. Specifically, walls are detected based on contact with the slab’s outer boundaries, while windows and doors are extracted from those located within these external walls. This semantic-independent detection ensures applicability to IFC models with incomplete or inconsistent attribute data. The unique identifiers (GlobalIDs) of all detected exterior elements are compiled into selection queries for downstream processing, including the generation of LoD3 external geometry and integration into the Multi-LoD4 framework.

3.1.3. Solid-to-MultiSurface Transformation

The simplified Multipatch dataset from the previous stage undergoes further processing to reduce geometric complexity and enhance analytical efficiency. The workflow involves dissolving adjacent surfaces, identifying planar regions, and calculating their areas. For each building element, the selection of representative faces is based on three conditions: identical GlobalID, consistent orientation (determined by surface normal), and the largest surface area within its group. This approach ensures that only the most representative planar faces are retained, resulting in a streamlined Multipatch dataset. These simplified geometries are then stored in a spatial database for analysis and visualization. In this study, the chosen approach follows a two-step process: (1) transforming IFC elements into Multipath geometries, and (2) converting these Multipaths into valid CityGML LoD3 surface model, enabling efficient integration with GIS workflows.

3.1.4. Outer Surface Detection in External Elements

This section outlines a geometry-based method for automatically identifying the outer surface from multi-surface representations of external building elements derived from IFC models. The method operates on polygonal surface data stored in shapefile format, with each polygon attributed with its GlobalId (unique element identifier), surface area, normal vector components (surfaceX, surfaceY, surfaceZ), and X and Y coordinates of the centroid. This method ensures that only the relevant exterior-facing side of each external element is retained. The input dataset consists of all polygonal surfaces belonging to external elements. Each exterior element typically has six faces: top, bottom, and four vertical sides. The objective is to isolate the most likely outer-facing vertical surface from each exterior entity. For each unique GlobalId, all associated surfaces are retrieved, and horizontal surfaces (those with surfaceZ = ±1) are excluded, leaving only vertical side faces of the wall. Two scenarios are considered:

Case A: Exactly Four Vertical Surfaces.

If an exterior element has exactly four vertical side surfaces, the algorithm performs the following steps:

- 1.

- Area-Based Selection: The four surfaces are sorted in descending order by area. The two largest surfaces are selected as candidate outer faces.

- 2.

- Directional Evaluation Using Surface Normals: For each candidate surface, the sign of the X and Y components of its normal vector is computed. A directional product is calculated as:

- 3.

- Axis Selection for Distance Comparison: If both candidate surfaces have Sign Product > 0, it indicates that their normals point toward the same general quadrant (e.g., northeast or southwest). In this case, the X-axis is selected for comparison. If both have Sign Product < 0, it implies opposing X–Y directions, and the Y-axis is used.

- 4.

- Centroid Comparison: The surface whose centroid coordinate (X or Y, depending on the selected axis) has the greatest absolute distance from the centroid of the room or floor is selected as the outer face.

Case B: More Than Four Vertical Surfaces.

This case accounts for exterior elements whose IFC export results in more than four side surfaces—often due to surface fragmentation or non-orthogonal geometry. The following procedure is applied:

- 1.

- Directional Grouping: All surfaces are grouped based on the signs of their normal vector components, resulting in four groups corresponding to the cardinal surface orientations:

- (1, 1): Northeast-facing.

- (1, −1): Southeast-facing.

- (−1, 1): Northwest-facing.

- (−1, −1): Southwest-facing.

- 2.

- Geometry Merging (Union): The surfaces in each group are merged using geometry operations. This produces a single multipart geometry for each direction, allowing for a consolidated centroid and total area to be calculated.

- 3.

- Area-Based Filtering: The four merged groups are sorted by area. The top two are selected as candidate outer faces.

- 4.

- Centroid and Sign Product Evaluation: As with Case A, each merged surface is evaluated based on the product of its directional signs. If both have Sign Product > 0, the X-axis is used for centroid comparison. If both are <0, the Y-axis is used.

- 5.

- Outer Face Determination: The surface group whose centroid coordinate (X or Y) has the greater absolute difference from the reference room centroid is selected. The original constituent surfaces belonging to that group are then extracted as the outer face.

The resulting output is a shapefile containing only the selected outer-facing surface for each external element, providing a refined geometric dataset for subsequent LoD3 generation.

3.1.5. Development of Multi-LoD4 ADE for CityGML

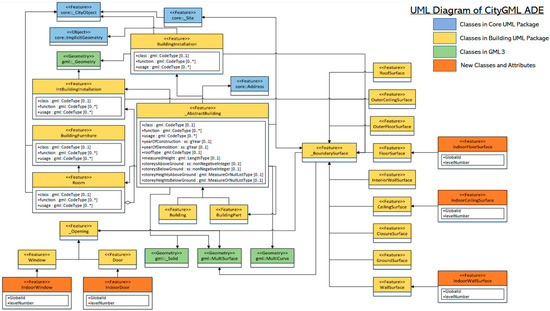

To enrich the semantic and geometric richness of CityGML model derived from IFC data, we developed an ADE that incorporates additional classes as subclasses of existing CityGML concepts. This design enables the integration of more detailed semantic and geometric representations, with a particular focus on interior building elements. The extension introduces the Multi-LoD4 concept, allowing multiple levels of detail to coexist within the LoD4 category, thereby providing a flexible representation of interior spaces at varying resolutions. The ADE was designed using a subclassing approach, ensuring consistency with the original CityGML structure while expanding its capabilities. Importantly, our ADE retains the original GlobalId for all elements, enabling direct linkage to external semantic databases such as graph-based systems, for enriched, queryable metadata. This connection not only supports complex data retrieval but also fosters interoperability with other BIM/GIS applications. Furthermore, the ADE’s structure supports selective visualization of 3D content—allowing components to be rendered separately based on user needs or system performance considerations. While ADEs are not required to be formally approved by standardization bodies, they provide a flexible mechanism to extend CityGML models in a standardized and interoperable way. Figure 3 illustrates the UML diagram of the developed CityGML ADE.

Figure 3.

UML diagram of developed CityGML ADE.

3.2. Semantic Information Transformation

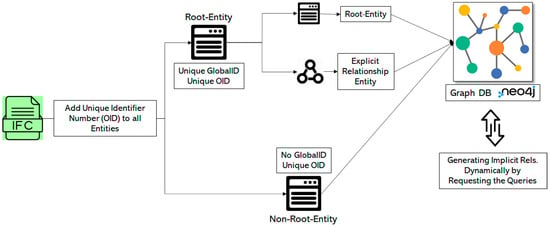

This study proposed a methodology for transferring the full semantic information of BIM into a GIS environment using a Labeled Property Graph (LPG) framework. The approach enables a comprehensive, query-ready integration of IFC semantics with spatial data by preserving entities information and their explicit relationships between building entities and the possibility of generating implicit relationships dynamically. The methodology involves four main stages: mapping IFC structure to graph database, capturing explicit and implicit relationships, linking entities via GlobalIds to maintain interoperability with external datasets, and designing flexible queries for dynamic information retrieval. The overview of the methodology is illustrated in Figure 4, while the following subsections describe each stage in detail.

Figure 4.

The overview of methodology to transfer semantic info of BIM in the graph database.

3.2.1. IFC-to-Graph Database Mapping

In the IFC data format, the entities are categorized into root-entity or non-root-entity. A key distinction between these categories is that the root-entity has a unique ID (GlobalId) while the non-root-entity does not. In our method, every entity, regardless of type, is assigned a unique ID to ensure complete traceability in the transformation process. To achieve this, we developed a preprocessing step that iterates through the IFC file and assigns a generated unique identifier number that is not in the IFC standard. The IFC schema defines two types of relationships: explicit and implicit. The explicit relationships are also a root-entity and based on the documentation of IFC data format, it has 37 explicit relationships. Our method leverages these explicit relationships as first-class nodes in the graph, rather than storing them as edges alone, enabling richer semantic querying and relationship analysis. This is accomplished using a Label Property Graph (LPG) model, which inherently supports the representation of relationships as nodes with attributes. We implemented a Python code that parses the IFC file, identifies both root and non-root entities, detects all explicit relationships, and maps them into the LPG structure.

3.2.2. Handling Explicit and Implicit Relationships

In IFC data models, relationships between entities are defined in two principal ways: (1) explicitly, through dedicated relationship classes (e.g., IfcRelAggregates, IfcRelContainedInSpatialStructure), and (2) implicitly, through attribute references embedded within entities. While explicit relationships are well-documented and straightforward to extract, implicit relationships require additional parsing logic to identify and interpret. This study contributes by developing an approach to detect and encode both explicit and implicit relationships for graph-based BIM-to-GIS integration. In our approach, implicit relationships typically fall into two categories:

- Referenced by attributes of a Root-Entity: In this case, a root-level IFC entity (i.e., a subtype of IfcRoot, such as IfcWall, IfcWindow, etc.) holds a direct attribute that references another entity. For example, an IfcWindow may have a reference to an IfcMaterial through its HasAssociations attribute. Although this reference is not via an explicit relationship entity like IfcRelAssociatesMaterial, it still forms a connection between the window and its material, creating an implicit link.

- Reference to attributes of a Root-Entity or Non-Root-Entity: This situation occurs when an entity (which may or may not be a subtype of IfcRoot) refers to attributes of another entity, forming an indirect connection. For example, an IfcOpeningElement may be linked to an IfcWall through its VoidsElements attribute. While this is commonly implemented through IfcRelVoidsElement, the referencing is stored as an attribute in both participating elements, creating a bi-directional reference even if not explicitly modeled in relational form.

By recognizing and parsing these implicit relationships, our approach ensures that all relevant semantic information from IFC models is preserved, especially for applications such as graph-based data modeling. This enables more complete and queryable semantic representations of the building structure, which is critical for advanced GIS analyses and urban digital twin applications.

3.2.3. GlobalId and Entity Linking in Graph Schema/Query Design and Dynamic Info Retrieval

In the constructed graph database, every IFC entity, including both root entities (such as IfcWall, IfcDoor, etc.) and non-root entities (such as IfcMaterialLayer, IfcCartesianPoint, etc.), is stored as a distinct node, and all explicit relationships (e.g., IfcRelAggregates, IfcRelDefinesByProperties) are also modelled as separate nodes with edges linking them to their participating entities. Implicit relationships are not pre-stored; instead, they are generated dynamically at query execution time by traversing attribute references in related entities. This hybrid strategy minimizes storage overhead while maintaining complete retrieval flexibility. All entities are indexed using a standardized unique identifier (either the original GlobalID or a custom-generated ID), enabling precise and efficient entity lookups. The graph schema supports reconstructing the entire set of semantic links—explicit and implicit—for any given entity on demand. This design allows for dynamic, user-driven retrieval of building information, ensuring that the semantic richness of IFC data is fully accessible for GIS-based visualization, analysis, and decision-making.

3.3. Integration and Visualization

The final stage of the workflow focuses on integrating the results of both geometry conversion and semantic enrichment into an interactive web-based platform, resulting in a functional urban digital twin. In this study, the CityGML geometries were converted into 3D Tiles format and hosted in a web environment capable of efficient rendering and scalable visualization. Simultaneously, the full semantic structure, extracted and stored within a graph database, was linked to the corresponding visualized geometry using unique identifiers. The developed web application enables users to explore integrated BIM and geospatial datasets by providing lightweight, simplified 3D geometry alongside rich, queryable semantic information. Real-time interaction is achieved by sending queries to the graph database, which dynamically returns semantic attributes for the elements selected in the 3D view. A notable contribution of this work is the seamless two-way connection between geometric visualization and semantic data retrieval, which supports advanced functionalities such as component-specific queries, attribute-based filtering, and visualization of multiple levels of detail. This design not only optimizes performance but also facilitates applications in urban planning, facility management, and smart city operations. Figure 5 illustrates the structure of the developed urban digital twin and its components.

Figure 5.

The structure of the urban digital twin which integrates both geometry and semantic data and provides the user with different functionality.

3.4. Implementation Strategy

The implementation workflow illustrated in Figure 6 demonstrates the complete integration pipeline from the original BIM model to the Urban Digital Twin (UDT) platform. The process begins with an IFC model, from which both exterior and interior building elements are detected using ArcGIS Pro and Python scripts. These elements are then processed through FME to perform Solid-to-MultiSurface conversion and subsequently written into the CityGML Multi-LoD4 ADE. The ADE schema was designed using a subclassing approach in UML, encoded as XSD, and validated to ensure schema compliance and consistency. The Multi-LoD4 ADE supports level-based interior visualization while preserving the GlobalId linkage to semantic data. The geometric models are then hosted and optimized in Cesium ion and converted into 3D Tiles for web visualization. In parallel, the semantic information from the IFC model is transformed into a graph database (Neo4j) through a Python-based pipeline that writes entities and relationships as labeled property graphs. Finally, the ADE-based geometry and the Neo4j semantic database are connected within the UDT platform, developed using CesiumJS for the frontend and Node.js with Express for the backend. This integrated environment allows users to interact with building elements, visualize multiple Levels of Detail, and query semantic information in real time.

Figure 6.

Implementation workflow of the proposed BIM–GIS integration framework.

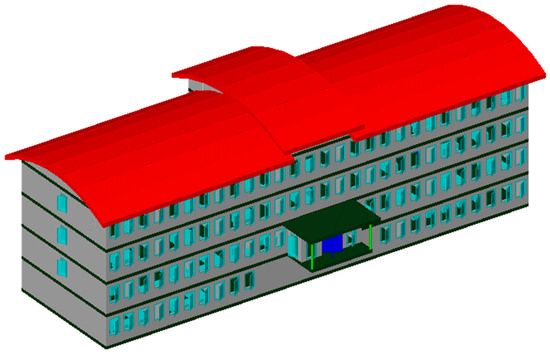

4. Results

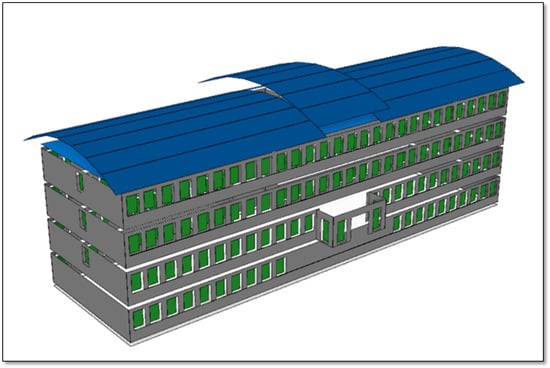

An office building model (Figure 7) in IFC4 data format, provided by the Institute for Automation and Applied Informatics (Campus North) at the Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT), was used to test and refine the proposed method. This office model is open to access and can be used unrestrictedly (IfcWiki, KIT IFC Examples, Available online http://www.ifcwiki.org/index.php?title=KIT_IFC_Examples, Accessed on: 27 March 2025). Among the three available open BIM, this building was intentionally selected because it represents the most complex structure, containing a rich variety of architectural, structural, and interior elements. This dataset provided the completeness and semantic depth necessary to effectively evaluate and demonstrate the full capabilities of the proposed approach. This model has all fundamental elements, including windows, doors, beams, members, walls, floors, roofs, stairs, and railings.

Figure 7.

Office building model (IFC) visualized using FZK Viewer.

4.1. Geometry Conversion

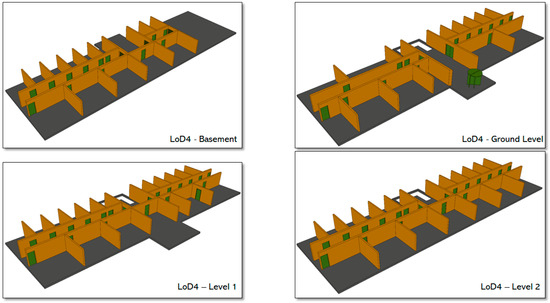

Elements from each level were extracted from the IFC dataset by leveraging spatial relationships to distinguish external building components from internal elements. The extracted exterior elements served as the basis for a workflow designed to isolate the building’s outer surface. Figure 8 illustrates the interior elements of each level and Figure 9 visualizes the resulting outer shell of the building generated through our methodology.

Figure 8.

Extracted interior elements of 3D building models using spatial relationships in GIS.

Figure 9.

Exterior Multipath models with all elements in ArcGIS Pro Env.

The level-by-level interior detection enables the proposed CityGML ADE to store each floor’s interior elements separately in LoD4, which significantly improves rendering efficiency and performance in urban digital twin platforms. Conversely, only the outermost surfaces of the exterior elements of a building were retained, reducing storage requirements, lowering geometric complexity, and aligning the model structure more closely with the CityGML standard definitions. This approach achieved a 24-fold reduction in total storage size for the office building model—an essential improvement given the volume of 3D models required for urban-scale implementations. Table 1 represents the details of the result and comparison between the size of elements before and after applying the methodology.

Table 1.

The comparison between the size of original 3D models and converted 3D models using the presented methodology of this paper.

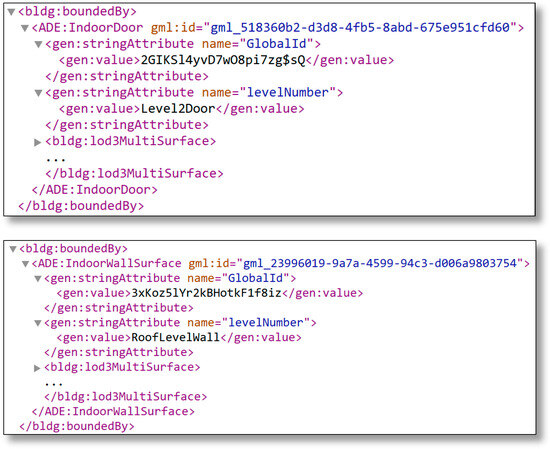

4.2. ADE Structure Validation

The feasibility of the proposed ADE was validated by generating and visualizing a complete schema instance. The converted geometry from the same IFC dataset was encoded into CityGML according to the developed ADE specifications. As illustrated in Figure 10, the resulting dataset incorporates new feature classes, such as “IndoorDoor” and “IndoorWallSurface” along with their associated attributes including “GlobalId” and “levelNumber”. This confirms that the ADE can extend the standard CityGML model to store detailed semantic information while maintaining compatibility with the converted geometry.

Figure 10.

Converted CityGML ADE model indicating the new classes and their attributes which can be used to link geometry and semantic information.

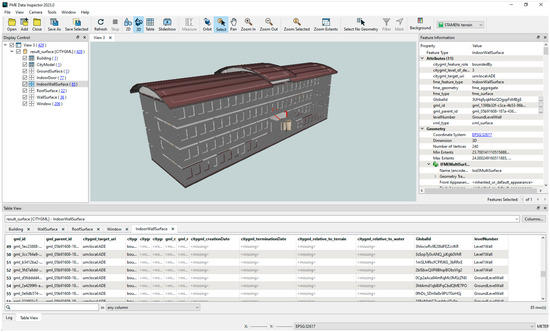

Since an ADE extends the standard CityGML data model, many existing CityGML software tools either fail to recognize or cannot fully process features beyond the core model. To address this, the generated ADE-based dataset was visualized in FME Data Inspector by loading the corresponding XSD schema of the ADE (Figure 11). This visualization not only confirms that the ADE was correctly developed but also serves as a form of schema validation step, clearly illustrating the additional features and attributes introduced by the ADE.

Figure 11.

Viewing the generated file in the FME Data Inspector, revealing multiple new classes and attributes enabled by the ADE.

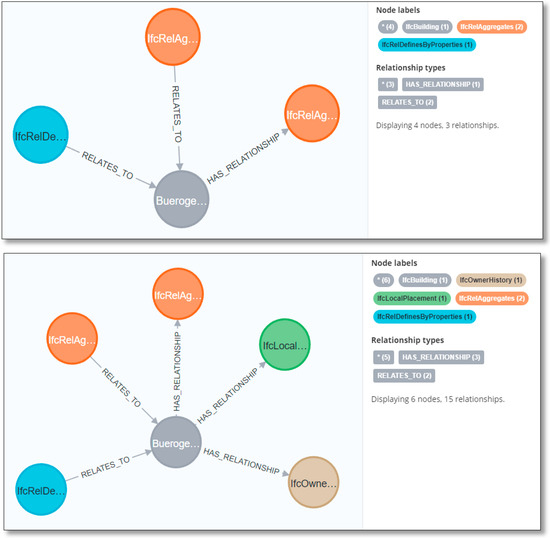

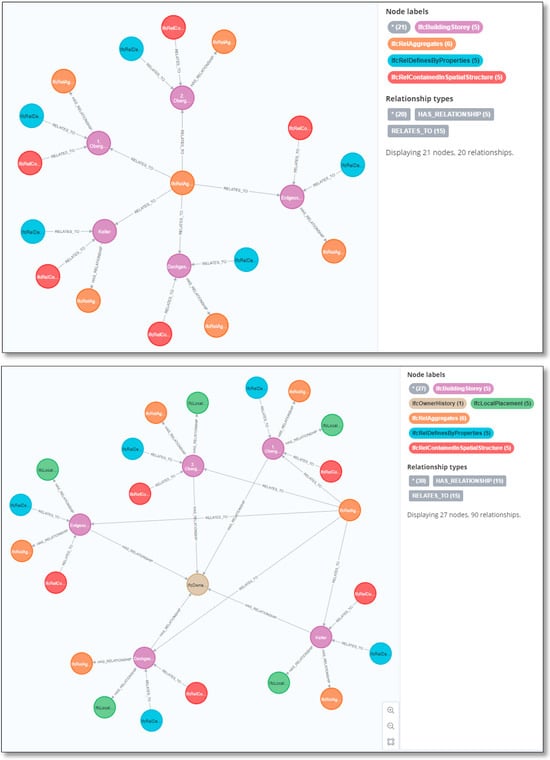

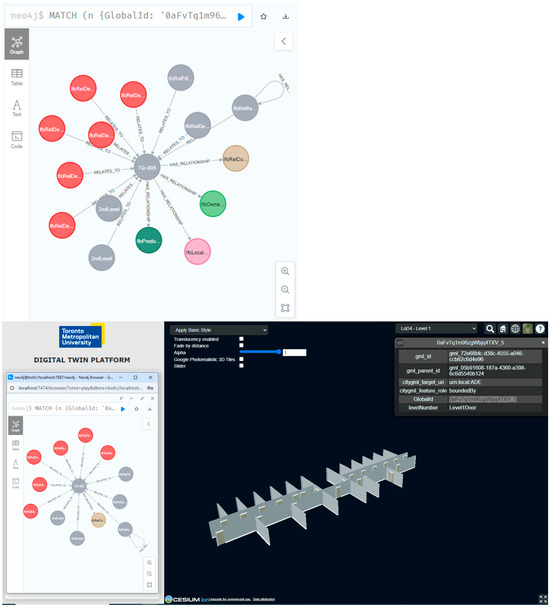

4.3. Graph Data Retrieval Performance

A property graph representation of IFC dataset was implemented in Neo4j, capturing the full semantic structure of the model. Each IFC entity (e.g., IfcWall, IfcSpace, IfcProject) was mapped to a node, while relationships such as containment, aggregation, assignment, and property definitions were represented as directed edges. The graph generation process was fully automated and completed successfully without data loss, preserving all attributes, property sets, and references from the original model. For a dataset containing 147,712 entities, the resulting graph database contained 149,905 nodes, a 1.48% increase due to minor redundancy, along with 15,033 relationships, and 116 distinct labels. The process took less than 33 min, demonstrating scalability for medium-sized IFC files. The only remaining aspect not captured directly during graph generation is the set of implicit relationships, which will be dynamically derived using entity types and attribute references, as described in the methodology section.

In terms of performance, information retrieval through Cypher queries was efficient and intuitive. Complex queries that would require multiple tables joins in a relational model—such as finding all components related to a specific space or retrieving all property definitions for a building element—were executed in a single step with minimal delay. In addition to the explicit relationships, implicit relationships were generated using predefined Cypher rules that inferred connections from entity attributes and cross-type dependencies. These enriched the semantic depth of the dataset, improving navigability and supporting advanced analytical workflows.

To illustrate this, we first queried a set of root and non-root entities along with their explicit relationships, as shown in Figure 12 and Figure 13. Then, we applied a series of predefined Cypher queries designed to detect implicit connections—such as referencing attributes, cross-type dependencies, or semantic hierarchies embedded in the data. These queries dynamically linked entities based on their internal structure and attribute values, enriching the graph with meaningful connections beyond the scope of the original IFC relationships. As shown in the examples, the resulting implicit relationships improve the navigability and semantic depth of the graph. The method proves to be effective in complementing the explicit model with deeper connections, supporting more advanced analysis and querying scenarios.

Figure 12.

Dynamically Generating Implicit Relationships of “IfcBuilding” Entity and Other Non-Root Entities by Cypher Query.

Figure 13.

Dynamically Generating Implicit Relationships of “IfcBuildingStorey” Entity and Other Non-Root Entities by Cypher Query.

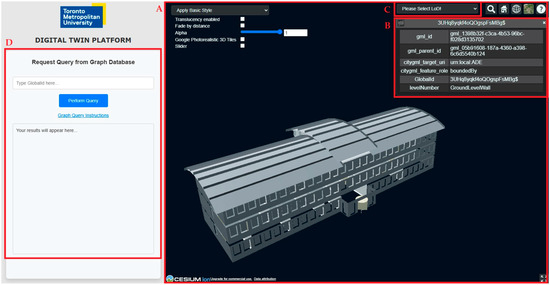

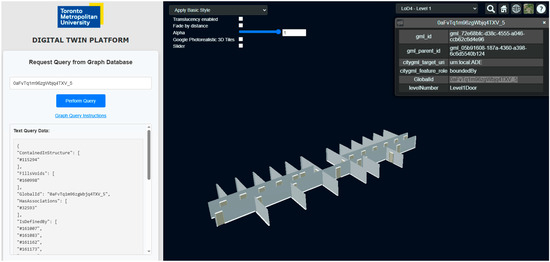

4.4. Integration Outcome in Urban Digital Twin Context

The converted IFC model, exported to extended CityGML ADE, was integrated and visualized within the developed urban digital twin using Cesium Ion. This framework provided interactive 3D visualization alongside full semantic access to each building element, including its attributes and both explicit and implicit relationships. A linkage between model geometry and semantic data was established via the LPG database. The interface (Figure 14) comprises four core components: (A) the main interface for visualizing the converted 3D models of the building, (B) the attributes of each element of the building which has been written in MultiLoD4 CityGML data format including necessary attributes (GlobalId and levelNumber) to link the geometry and semantic information, (C) the dropdown option for the user to choose the LoD of building to visualize, including LoD3 and Multi-LoD4, and (D) the interface to send the query of the user using GlobalId of elements and return the result as text and graph to visualize the attributes and all relationships. The result of a specific case, door of level 1, has been illustrated in Figure 15 and Figure 16. Figure 15 shows the LoD4 geometry part of level 1 and on the left side the semantic information of specific door which has been selected by user has been printed. Also, the graph visualization of all explicit and implicit relationships can be provided to user based on the request which has been illustrated in Figure 16.

Figure 14.

The interface of developed UDT to visualize the 3D model of the building in LoD3 and Multi-LoD4 with full access to the semantic information of elements through the generated graph database. (A) The main interface to show the geometry of 3D buildings. (B) The attributes of building elements in developed CityGML ADE. (C) The dropdown menu for choosing the LoD visualization. (D) Request the query and send back the result to the user from the graph database.

Figure 15.

LoD4 geometry visualization of Level 1 with the semantic information of the selected door displayed on the left. The user-selected element enables focused exploration of associated attributes.

Figure 16.

Graph-based representation of all explicit and implicit relationships related to the selected door, generated on user request for semantic context analysis.

5. Discussion

To address the problem of the complexity of converted geometry of BIMs to a GIS environment and the lack of a feasible approach to transfer all semantic information from IFC data models into CityGML, this paper developed an effective approach to integrate geometric and semantic information of BIMs into GIS by focusing on Urban Digital Twin concepts. The distinctions between previous studies [14,17,18,19,20,37] and the proposed approach to BIM/GIS integration are summarized in Table 2, while the original contributions of this study are discussed in detail throughout the remainder of this section.

Table 2.

The comparison between the previous BIM/GIS integration studies and the proposed approach.

- 1.

- Solid to Surface Model Transformation by IFC-to-CityGML Conversion

Prior work has either generalized already-surface CityGML models [16], converted IFC with heavy morphological operations and semantic assumptions [18], or focused on visibility filtering rather than geometric conversion [20]. Others extract envelopes with scanning/camera methods that are sensitive to setup and do not truly convert solids to surfaces [19], or pursue comprehensive mappings without isolating only the outermost faces [17]. The method proposed in this study overcomes these limitations by combining level-wise classification of external and internal IFC components with explicit identification of true external surfaces. By converting the solid geometry of external elements into multi-surface representations, the resulting LoD3 CityGML models are both lightweight and valid. For example, on the same dataset tested by Ref. [18], our approach reduced the file size from 2.3 MB to only 1.4 MB, representing a significant improvement in efficiency without loss of semantic integrity. This reduction is particularly important for urban digital twin applications where storage, rendering speed, and model validity are critical. Compared with surface detection techniques that either oversimplify geometry or retain unnecessary detail, our approach provides a robust and semantically interpretable pipeline that aligns with the needs of CityGML-based urban models.

- 2.

- Solid Model Simplification by Developing CityGML ADE (Multi-LoD4)

Although CityGML supports Level of Detail (LoD) representations, the simplification of solid building models remains underdeveloped. Existing LoD conversion methods are primarily designed for surface-based models and cannot be directly applied to solid geometries commonly found in BIM data. Some studies, such as Ref. [33], attempted solid-to-surface simplification for GIS, but their workflows relied heavily on detailed semantic information embedded in IFC files. This reliance is problematic, as IFC semantics are often incomplete, inconsistent, or project-specific, leading to reduced applicability in practice. We address this by introducing a Multi-LoD4 ADE that organizes interiors by level and can be toggled on demand. Crucially, our pipeline identifies internal/external elements without relying on IFC labels, using only geometric/spatial relations; this makes the approach robust when property sets are incomplete. These elements are then encoded in new ADE classes with attributes that support linking geometry to semantic information through queryable identifiers. This structure allows users to selectively visualize components at different LoDs, thereby reducing rendering load and improving performance in urban digital twin platforms, especially when dealing with large-scale BIM datasets. By contrast, earlier methods either oversimplified geometry (limiting semantic richness) or failed to guarantee schema validity in CityGML outputs. The Multi-LoD4 ADE therefore represents a novel and scalable solution, bridging the gap between detailed BIM solids and efficient GIS visualization in urban-scale applications.

- 3.

- Automatic Full Semantic Information Transferring by LPG Database

The semantic information transfer between BIM and GIS remains a significant challenge due to limited interoperability and the inadequacy of traditional relational databases in capturing complex relationships. Relational models struggle to represent the highly interconnected nature of building information, often resulting in data loss during transformation. Graph technologies, particularly Labelled Property Graph (LPG) databases, offer a promising solution by enabling a more expressive and flexible representation of entities and their relationships. However, despite their potential, LPG-based approaches for fully capturing IFC semantics are still underexplored. To address this gap, this study proposes an automatic method to generate an LPG database directly from IFC files. The method extracts and stores all entities and their attributes, along with all explicit relationships among them. Rather than pre-generating all possible implicit relationships, which could result in an overwhelming number of edges, these are instead generated dynamically upon user request through predefined query templates. This strategy ensures the completeness of semantic representation while optimizing storage and improving the performance of querying and visualization in urban digital twin applications. Additionally, the graph structure supports intuitive and efficient navigation of building information, enabling users to explore the IFC model semantically through graph visualization and query-driven access.

- 4.

- A Dynamic Query-Based Framework for Connecting Simplified Geometry with Full Semantics in Urban Digital Twins

Building upon the previous contributions, this study develops a comprehensive framework that integrates simplified BIM geometry and full semantic information within an Urban Digital Twin (UDT) environment. By combining the Multi-LoD4 CityGML ADE with the LPG-based semantic graph, the framework enables users to interactively visualize and analyze building models at different levels of detail. Users can view each building level separately, select from various LoDs, and retrieve relevant semantic information through dynamic queries. This is made possible by linking simplified geometry (in CityGML) to the original IFC semantics via GlobalId attributes embedded in the ADE schema. When a query is issued for a specific element, the system can retrieve its explicit relationships from the graph database and, if needed, dynamically generate implicit relationships. This dual access—to simplified geometry and full IFC semantics—empowers users to conduct analysis and decision-making with reduced visual and computational complexity, while maintaining semantic richness. The proposed framework significantly enhances the performance, usability, and analytical power of urban digital twin platforms, especially in scenarios involving large and complex BIM datasets.

6. Conclusions

This study presented a unified methodology for integrating geometric and semantic data from BIM into GIS, with a focus on supporting UDT applications. The workflow combined a solid-to-surface transformation of IFC models, a Multi-LoD4 ADE for level-based interior management, and a fully automatic IFC-to-LPG pipeline to preserve semantic richness. Together, these components provide a scalable solution for reducing geometric complexity, maintaining semantic integrity, and enabling dynamic queries in UDT environments.

On the geometric side, the approach introduced a structured method for detecting external and internal building elements level-by-level, producing simplified and valid surface-based CityGML LoD3 outputs. The Multi-LoD4 ADE represent a key innovation, enabling level-based selective interior visualization while ensuring direct linkage to semantic data. On the semantic side, the graph-based strategy captured all IFC entities and explicit relationships, with implicit relationships generated dynamically at query time. Experimental results on a representative model confirmed substantial reductions in geometric complexity, schema-compliant ADE validation, and efficient semantic retrieval.

Beyond its technical contributions, the proposed Multi-LoD4 ADE and UDT platform also offer significant practical potential for professional applications. City planners can employ the system for resilience assessment and infrastructure management, architects can use the multi-level interior representation for design evaluation and energy modeling, and facility managers can benefit from the semantic linkage to support asset monitoring and maintenance planning. These examples demonstrate how the framework can bridge the gap between BIM/GIS research and real-world decision-making in the context of data-driven Urban Digital Twins.

However, several limitations remain. The workflow has been validated on mid-sized buildings; its robustness on highly irregular models is yet to be demonstrated. The ADE currently depends on specialized tool support, which restricts interoperability across platforms. While the LPG structure proved effective for medium datasets, scalability to very large semantic graphs require further benchmarking. Additionally, the reliance on dynamic generation of implicit relationships may lead to variable query performance.

Ongoing work extends the framework to multi-building cases, aiming to evaluate performance, scalability, and interoperability across diverse building typologies. Future work will also focus on extending the developed ADE to a CityGML 3.0, compliant version, leveraging its enhanced modular structure and updated Level-of-Detail concept to improve flexibility, semantic consistency, and integration capabilities. Beyond this, we plan to expand the ADE schema to support infrastructure elements (e.g., bridges, roads), improve support for dynamic or time-varying datasets, and enhance interoperability across different software platforms, and strengthen compatibility with mainstream GIS software. Optimization of query performance for large-scale semantic graphs and the integration of AI-based techniques for automatic classification of interior/exterior elements will also be pursued. These advancements aim to strengthen the role of BIM/GIS integration in enabling responsive, semantically rich, and scalable urban digital twins.

Author Contributions

Peyman Azari led the conceptualization, methodology, formal analysis, and writing of the original draft. Songnian Li provided input in methodology and formal analysis. Songnian Li and Ahmed Shaker provided critical reviews, enhancing the study’s methodology and refining the manuscript’s narrative and arguments. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Natural Science and Engineering Research Council (NSERC) [grant number ALLRP 544569-19].

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available at http://www.ifcwiki.org/index.php?title=KIT_IFC_Examples (accessed on 26 November 2025), provided by the Institute for Automation and Applied Informatics (IAI)/Karlsruhe Institute of Technology (KIT).

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the FuseForward Solutions Group Ltd. for their support.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Amirebrahimi, S.; Rajabifard, A.; Mendis, P.; Ngo, T. A data model for integrating GIS and BIM for assessment and 3D visualisation of flood damage to building, in: CEUR Workshop. Locate 2015, 15, 10–12. [Google Scholar]

- Azari, P.; Li, S.; Shaker, A.; Sattar, S. Georeferencing Building Information Models for BIM/GIS Integration: A Review of Methods and Tools. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barrile, V.; La Foresta, F.; Calcagno, S.; Genovese, E. Innovative System for BIM/GIS Integration in the Context of Urban Sustainability. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 8704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bilotta, G.; Calcagno, S.; Bonfa, S. Wildfires: An application of remote sensing and OBIA. WSEAS Trans. Environ. Dev. 2021, 17, 282–296. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cao, Y.; Xu, C.; Aziz, N.M.; Kamaruzzaman, S.N. BIM–GIS Integrated Utilization in Urban Disaster Management: The Contributions, Challenges, and Future Directions. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 1331. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hor, A.E.H.; Sohn, G.; Claudio, P.; Jadidi, M.; Afnan, A. A semantic graph database for BIM-GIS integrated information model for an intelligent urban mobility web application. ISPRS Ann. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. 2018, 4, 89–96. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thiis, T.K.; Hjelseth, E. Use of BIM and GIS to enable climatic adaptions of buildings. Ework Ebus. Archit. Eng. Constr. 2008, 409–417. [Google Scholar]

- Torabi, M.S.; Lombardi, P.; Ugliotti, F.M.; Osello, A.; Mutani, G. BIM-GIS modelling for sustainable urban development. NEWDIST 2016, 339–350. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, B.; Zhang, S. Integration of GIS And BIM for indoor geovisual analytics. Int. Arch. Photogramm. Remote Sens. Spat. Inf. Sci. –ISPRS Arch. 2016, 41, 455–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yamamura, S.; Fan, L.; Suzuki, Y. Assessment of Urban Energy Performance through Integration of BIM and GIS for Smart City Planning. Procedia Eng. 2017, 180, 1462–1472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Congiu, E.; Quaquero, E.; Rubiu, G.; Vacca, G. Building Information Modeling and Geographic Information System: Integrated Framework in Support of Facility Management (FM). Buildings 2024, 14, 610. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Irizarry, J.; Karan, E.P. Optimizing location of tower cranes on construction sites through GIS and BIM integration. Electron. J. Inf. Technol. Constr. 2012, 17, 361–366. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Z.; Shi, J.; Jiang, L. A Novel HDF-Based Data Compression and Integration Approach to Support BIM-GIS Practical Applications. Adv. Civ. Eng. 2020, 2020, 8865107. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Wu, P. BIM/GIS data integration from the perspective of information flow. Autom. Constr. 2022, 136, 104166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tan, Y.; Liang, Y.; Zhu, J. CityGML in the Integration of BIM and the GIS: Challenges and Opportunities. Buildings 2023, 13, 1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, H.; Meng, L.; Jahnke, M. Generalization of 3D Buildings Modelled by CityGML. In Lecture Notes in Geoinformation and Cartography; Kluwer Academic Publishers: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2009; pp. 387–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Deng, Y.; Cheng, J.C.P.; Anumba, C. Mapping between BIM and 3D GIS in different levels of detail using schema mediation and instance comparison. Autom. Constr. 2016, 67, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donkers, S.; Ledoux, H.; Zhao, J.; Stoter, J. Automatic conversion of IFC datasets to geometrically and semantically correct CityGML LOD3 buildings. Trans. GIS 2016, 20, 547–569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, T.W.; Hong, C.H. IFC-CityGML LOD mapping automation using multiprocessing-based screen-buffer scanning including mapping rule. KSCE J. Civ. Eng. 2018, 22, 373–383. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, X.; Zhao, J.; Wang, J.; Su, D.; Zhang, H.; Guo, M.; Guo, M.; Li, Z. OutDet: An algorithm for extracting the outer surfaces of building information models for integration with geographic information systems. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Sci. 2019, 33, 1444–1470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Wu, P.; Anumba, C. A semantics-based approach for simplifying IFC building models to facilitate the use of bim models in GIS. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 4727. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ding, X.; Yang, J.; Liu, L.; Huang, W.; Wu, P. Integrating IFC and CityGML model at schema level by using linguistic and text mining techniques. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 56429–56440. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stouffs, R.; Tauscher, H.; Biljecki, F. Achieving complete and near-lossless conversion from IFC to CityGML †. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2018, 7, 355. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Laat, R.; van Berlo, L. Integration of BIM and GIS: The Development of the CityGML GeoBIM Extension; Lecture Notes in Geoinformation and Cartography; Kolbe, T., König, G., Nagel, C., Eds.; Springer: Berlin, Germany, 2010; pp. 211–225. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, T.W.; Hong, C.H. IFC-CityGML LOD mapping automation based on multi-processing. In Proceedings of the 32nd International Symposium on Automation and Robotics in Construction and Mining: Connected to the Future, Oulu, Finland, 15–18 June 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Wu, P. Towards effective BIM/GIS data integration for smart city by integrating computer graphics technique. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Wang, X.; Wright, G.; Cheng, J.C.P.; Li, X.; Liu, R. A state-of-the-art review on the integration of Building Information Modeling (BIM) and Geographic Information System (GIS). ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2017, 6, 53. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Chong, H.-Y.; Zhao, H.; Wu, J.; Tan, Y.; Xu, H. The Application of Graph in BIM/GIS Integration. Buildings 2022, 12, 2162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gröger, G.; Kolbe, T.H.; Czerwinski, A.; Nagel, C. OpenGIS City Geography Markup Language (CityGML) Encoding Standard. In Proceedings of the Open Geospatial Consortium, Wayland, MA, USA, 20 August 2008; p. 234. [Google Scholar]

- Peters, E. BIM and geospatial information systems. In Handbook of Research on Building Information Modeling and Construction Informatics: Concepts and Technologies; IGI Global Scientific Publishing: Hershey, PA, USA, 2010; pp. 483–500. [Google Scholar]

- Rafiee, A.; Dias, E.; Fruijtier, S.; Scholten, H. From BIM to geo-analysis: View coverage and shadow analysis by BIM/GIS integration. Procedia Environ. Sci. 2014, 22, 397–402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanton-Chapman, T.L.; Chapman, D.A. Using GIS to Investigate the Role of Recreation and Leisure Activities in the Prevention of Emotional and Behavioral Disorders. Int. Rev. Res. Ment. Retard. 2006, 33, 191–211. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, J.; Wright, G.; Wang, J.; Wang, X. A critical review of the integration of geographic information system and building information modelling at the data level. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2018, 7, 66. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mekawy, M.; Östman, A.; Hijazi, I. A unified building model for 3D urban GIS. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2012, 1, 120–145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Mekawy, M.; Östman, A. Semantic Mapping: An Ontology Engineering Method for Integrating Building Models in IFC and CITYGML. In Proceedings of the 3rd ISDE Digital Earth Summit, Nessebar, Bulgaria, 12–14 June 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Ma, Z.; Ren, Y. Integrated Application of BIM and GIS: An Overview. Procedia Eng. 2017, 196, 1072–1079. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Adouane, K.; Stouffs, R.; Janssen, P.; Domer, B. A model-based approach to convert a building BIM-IFC data set model into CityGML. J. Spat. Sci. 2020, 65, 257–280. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El-Mekawy, M.; Östman, A.; Hijazi, I. An evaluation of IFC-CityGML unidirectional conversion. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2012, 3, 159–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, C.; Aouad, G.; Lee, A.; Mashall-Ponting, A.; Wu, S. IFC model viewer to support nD model application. Autom. Constr. 2006, 15, 178–185. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jetlund, K.; Onstein, E.; Huang, L. IFC schemas in ISO/TC 211 compliant UML for improved interoperability between BIM and GIS. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2020, 9, 278. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).