Impact of Synthetic Data on Deep Learning Models for Earth Observation: Photovoltaic Panel Detection Case Study

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Materials and Methods

3. Methodology

3.1. Generation Process of the Physically Based Simulated Data

3.2. Generation Process of the AI-Generated Data

- An urban area was selected where solar panels could potentially be installed on rooftops, spanning as large a region as an entire city.

- The rasterized map of this area was obtained and divided into patches matching the size and scale used during the hypernetwork training. These patches were fed into the conditioned diffusion model, which generated satellite-like images similar to those used during training but never identical. For each possible initial noise seed, the resulting image will feature elements aligned with the map but with significant variations in finer details.

- Since solar panels are not cataloged in OpenStreetMap, the synthetic images were analyzed using simple computer vision algorithms. In the final step, solar panels were added using traditional computer graphics techniques (explained below).

- Detection and segmentation of candidate areas within illuminated roofs to place solar panels. A high proportion of roofs, especially on industrial buildings, reflect a significant amount of light, saturating the satellite sensors. This is likely due to the roof inclination and the fact that many of these surfaces are actually flat. These saturated areas are typically found on the most illuminated parts of the roofs, which are ideal locations for placing solar panels. Detecting saturated areas in the synthetic images was straightforward using basic thresholding algorithms. The system therefore identified very “white” regions (with a configurable deviation of 8% by default) and a minimum size of 100 pixels. These areas were marked with oriented bounding boxes, and the vertex coordinates of the boxes were provided to train solar panel detectors.

- AI-generated solar panels with non-idealities. A combination of two existing diffusion models was used to synthesize solar panel textures, which were then mapped onto areas of interest detected in the previous phase. Specifically, DALL·E 3 and Stable Diffusion XL were exploited to generate high-resolution solar panel images, from which dynamic texture portions were taken to edit aerial images on the fly.

- Over 90 base textures at 1024 × 1024 pixels were created, featuring: Various cell patterns, cell shapes, and connectors. Different levels of dirt due to dust, ash, and grime. Surface defects, including incomplete and damaged panels.

- Mapping to combine diffusion model samples into final images. The bounding boxes oriented towards the candidate areas identified earlier were used to map planar portions of the textures generated, following a simple procedure of rescaling and mipmapping with pyramid filtering. Since 3D object estimates were not available and the projection was nearly orthographic, this basic mapping method worked effectively. Additionally, a border was added around the roof area where the panels were placed to simulate the frames and reinforcement structures typically used in urban settings. Figure 5 shows an example of AI-based synthetic images with their associated photovoltaic binary masks.

3.3. AI-Analytics Methodology

3.3.1. YOLOv8

3.3.2. Synthetic Data Preprocessing

3.3.3. Benchmarks and Experiments

3.3.4. Evaluation Metrics

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Benchmarks and Experiments Results

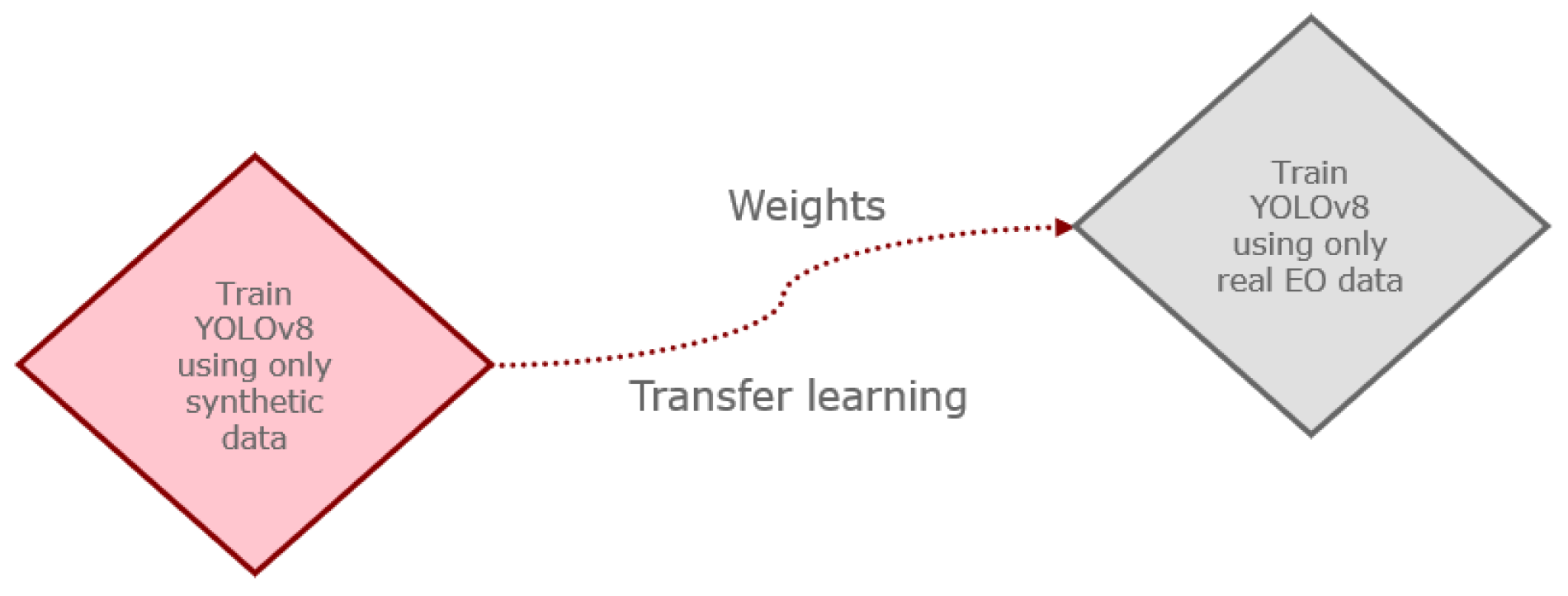

4.2. Test Using Synthetic Data for Transfer Learning

4.3. Tests with Consistent Training Steps

- Batch size is an important hyperparameter in YOLOv8, and changing it could influence model performance, making it unclear whether performance changes are due to the batch size or synthetic data.

- Larger batch sizes demand more memory, and in several cases, the required batch size (e.g., 150 or 250) exceeded GPU capacity, limiting the practicality of this method.

4.4. Comparative Analysis of Synthetic Data Generation Approaches

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| AI | Artificial intelligence |

| CNN | Convolutional neural network |

| CRS | Coordinate reference system |

| DL | Deep learning |

| EO | Earth observation |

| ESA | European Space Agency |

| FN | False negative |

| FP | False positive |

| GAN | Generative adversarial network |

| GT | Ground truth |

| ML | Machine learning |

| PBR | Physically based rendering |

| PV | Photovoltaic |

| RGB | Red-green-blue (color model) |

| SD4EO | Synthetic data for earth observation |

| TP | True positive |

| UAV | Unmanned aerial vehicle |

| VHR | Very high resolution |

Appendix A

References

- Jäger-Waldau, A. Snapshot of Photovoltaics−May 2023. EPJ Photovolt. 2023, 14, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wen, D.; Gao, W. Impact of Renewable Energy Policies on Solar Photovoltaic Energy: Comparison of China, Germany, Japan, and the United States of America. In Distributed Energy Resources: Solutions for a Low Carbon Society; Gao, W., Ed.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 43–68. ISBN 978-3-031-21097-6. [Google Scholar]

- Pourasl, H.H.; Barenji, R.V.; Khojastehnezhad, V.M. Solar Energy Status in the World: A Comprehensive Review. Energy Rep. 2023, 10, 3474–3493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, L. Automatic Detection and Mapping of Solar Photovoltaic Arrays with Deep Convolutional Neural Networks in High Resolution Satellite Images. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE 4th Conference on Energy Internet and Energy System Integration (EI2), Wuhan, China, 30 October–1 November 2020; pp. 3068–3073. [Google Scholar]

- Clark, C.N.; Pacifici, F. A Solar Panel Dataset of Very High Resolution Satellite Imagery to Support the Sustainable Development Goals. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kasmi, G.; Saint-Drenan, Y.-M.; Trebosc, D.; Jolivet, R.; Leloux, J.; Sarr, B.; Dubus, L. A Crowdsourced Dataset of Aerial Images with Annotated Solar Photovoltaic Arrays and Installation Metadata. Sci. Data 2023, 10, 59. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Villalobos, P.; Ho, A.; Sevilla, J.; Besiroglu, T.; Heim, L.; Hobbhahn, M. Will We Run out of Data? Limits of LLM Scaling Based on Human-Generated Data. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2211.04325. [Google Scholar]

- Azizi, S.; Kornblith, S.; Saharia, C.; Norouzi, M.; Fleet, D.J. Synthetic Data from Diffusion Models Improves ImageNet Classification. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.08466. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burg, M.F.; Wenzel, F.; Zietlow, D.; Horn, M.; Makansi, O.; Locatello, F.; Russell, C. Image Retrieval Outperforms Diffusion Models on Data Augmentation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.10253. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luzi, L.; Mayer, P.M.; Casco-Rodriguez, J.; Siahkoohi, A.; Baraniuk, R.G. Boomerang: Local Sampling on Image Manifolds Using Diffusion Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2210.12100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veselovsky, V.; Ribeiro, M.H.; West, R. Artificial Artificial Artificial Intelligence: Crowd Workers Widely Use Large Language Models for Text Production Tasks. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2306.07899. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, H.; Grover, A. Leaving Reality to Imagination: Robust Classification via Generated Datasets. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.02503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, H.; Liu, Z.; Liao, W.; Huang, X.; Cao, Y.; Wu, Z.; Zhao, L.; Xu, S.; Liu, W.; Liu, N.; et al. AugGPT: Leveraging ChatGPT for Text Data Augmentation. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.13007. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, R.; Sun, S.; Yu, X.; Xue, C.; Zhang, W.; Torr, P.; Bai, S.; Qi, X. Is Synthetic Data from Generative Models Ready for Image Recognition? arXiv 2023, arXiv:2210.07574. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, S.; Wang, K.; Zeng, X.; Zhao, R. Explore the Power of Synthetic Data on Few-Shot Object Detection. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.13221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shipard, J.; Wiliem, A.; Thanh, K.N.; Xiang, W.; Fookes, C. Diversity is Definitely Needed: Improving Model-Agnostic Zero-Shot Classification via Stable Diffusion. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.03298. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Guo, D.; Duan, N.; McAuley, J. Baize: An Open-Source Chat Model with Parameter-Efficient Tuning on Self-Chat Data. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2304.01196. [Google Scholar]

- Klemp, M.; Rösch, K.; Wagner, R.; Quehl, J.; Lauer, M. LDFA: Latent Diffusion Face Anonymization for Self-Driving Applications. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.08931v1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Packhäuser, K.; Folle, L.; Thamm, F.; Maier, A. Generation of Anonymous Chest Radiographs Using Latent Diffusion Models for Training Thoracic Abnormality Classification Systems. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE 20th International Symposium on Biomedical Imaging (ISBI), Cartagena de Indias, Colombia, 17–21 April 2023; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Veeravasarapu, V.S.R.; Rothkopf, C.; Ramesh, V. Model-Driven Simulations for Deep Convolutional Neural Networks. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1605.09582. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Veeravasarapu, V.; Rothkopf, C.; Visvanathan, R. Model-Driven Simulations for Computer Vision. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Santa Rosa, CA, USA, 27–29 March 2017; pp. 1063–1071. [Google Scholar]

- Savva, M.; Kadian, A.; Maksymets, O.; Zhao, Y.; Wijmans, E.; Jain, B.; Straub, J.; Liu, J.; Koltun, V.; Malik, J.; et al. Habitat: A Platform for Embodied AI Research. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Seoul, Republic of Korea, 27 October–2 November 2019; pp. 9339–9347. [Google Scholar]

- Schwarz, M.; Behnke, S. Stillleben: Realistic Scene Synthesis for Deep Learning in Robotics. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Paris, France, 31 May–31 August 2020; pp. 10502–10508. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Song, S.; Yumer, E.; Savva, M.; Lee, J.-Y.; Jin, H.; Funkhouser, T. Physically-Based Rendering for Indoor Scene Understanding Using Convolutional Neural Networks. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1612.07429. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schneegans, S.; Meyran, T.; Ginkel, I.; Zachmann, G.; Gerndt, A. Physically Based Real-Time Rendering of Atmospheres Using Mie Theory. Comput. Graph. Forum 2024, 43, e15010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, W.; Luo, B.; Liu, J. Synthetic Data Augmentation Using Multiscale Attention CycleGAN for Aircraft Detection in Remote Sensing Images. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2022, 19, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Howe, J.; Pula, K.; Reite, A.A. Conditional Generative Adversarial Networks for Data Augmentation and Adaptation in Remotely Sensed Imagery. In Proceedings of the Applications of Machine Learning, San Diego, CA, USA, 6 September 2019; p. 13. [Google Scholar]

- Clement, N.; Schoen, A.; Boedihardjo, A.; Jenkins, A. Synthetic Data and Hierarchical Object Detection in Overhead Imagery. ACM Trans Multimed. Comput. Commun. Appl. 2024, 20, 117. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guo, J.; Lei, B.; Ding, C.; Zhang, Y. Synthetic Aperture Radar Image Synthesis by Using Generative Adversarial Nets. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2017, 14, 1111–1115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abady, L.; Barni, M.; Garzelli, A.; Tondi, B. GAN Generation of Synthetic Multispectral Satellite Images. In Proceedings of the Image and Signal Processing for Remote Sensing XXVI, SPIE, Online, 20 September 2020; Volume 11533, pp. 122–133. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, H.; Yao, L.; Lu, N.; Qin, J.; Liu, T.; Liu, Y.; Zhou, C. Multi-Resolution Dataset for Photovoltaic Panel Segmentation from Satellite and Aerial Imagery. Earth Syst. Sci. Data 2021, 13, 5389–5401. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.-L.; Wang, J.; Vouga, E.; Wonka, P. Urban Pattern: Layout Design by Hierarchical Domain Splitting. ACM Trans. Graph. 2013, 32, 181. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gimeno Sancho, J.; Fernandez Marín, M.; García Blaya, A.; Pérez Folgado, I.; Casanova-Salas, P.; Gini, R.; Fernández Guirao, A.; Pérez Aixendri, M. SD4EO—Physically Based Rendering Images of Human Settlements for Solar Panel Detection. Zenodo 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ho, J.; Jain, A.; Abbeel, P. Denoising Diffusion Probabilistic Models. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2006.11239v2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rombach, R.; Blattmann, A.; Lorenz, D.; Esser, P.; Ommer, B. High-Resolution Image Synthesis with Latent Diffusion Models. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.10752. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L.; Rao, A.; Agrawala, M. Adding Conditional Control to Text-to-Image Diffusion Models. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2302.05543. [Google Scholar]

- Data Augmentation in Earth Observation: A Diffusion Model Approach. Available online: https://www.mdpi.com/2078-2489/16/2/81 (accessed on 12 November 2025).

- Dhariwal, P.; Nichol, A. Diffusion Models Beat GANs on Image Synthesis. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2105.05233. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fang, H.; Han, B.; Zhang, S.; Zhou, S.; Hu, C.; Ye, W.-M. Data Augmentation for Object Detection via Controllable Diffusion Models. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa, HI, USA, 4–8 January 2024; pp. 1257–1266. [Google Scholar]

- Zhu, J.-Y.; Park, T.; Isola, P.; Efros, A.A. Unpaired Image-To-Image Translation Using Cycle-Consistent Adversarial Networks. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1703.10593. [Google Scholar]

- Terven, J.; Cordova-Esparza, D. A Comprehensive Review of YOLO Architectures in Computer Vision: From YOLOv1 to YOLOv8 and YOLO-NAS. Mach. Learn. Knowl. Extr. 2023, 5, 1680–1716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan Mohammadi, M.; Schneidereit, T.; Mansouri Yarahmadi, A.; Breuß, M. Investigating Training Datasets of Real and Synthetic Images for Outdoor Swimmer Localisation with YOLO. AI 2024, 5, 576–593. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alqudah, R.; Al-Mousa, A.A.; Abu Hashyeh, Y.; Alzaibaq, O.Z. A Systemic Comparison between Using Augmented Data and Synthetic Data as Means of Enhancing Wafermap Defect Classification. Comput. Ind. 2023, 145, 103809. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, R.; Wei, J.; Liu, F.; Si, C.; Zhang, Y.; Rao, J.; Zheng, S.; Peng, D.; Yang, D.; Zhou, D.; et al. Best Practices and Lessons Learned on Synthetic Data. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2404.07503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Przystupa, M.; Abdul-Mageed, M. Volume 3: Shared Task Papers, Day 2. Neural Machine Translation of Low-Resource and Similar Languages with Backtranslation. In Proceedings of the Fourth Conference on Machine Translation, Florence, Italy, 1–2 August 2019; Bojar, O., Chatterjee, R., Federmann, C., Fishel, M., Graham, Y., Haddow, B., Huck, M., Yepes, A.J., Eds.; Association for Computational Linguistics: Florence, Italy, 2019; pp. 224–235. [Google Scholar]

- Sagmeister, D.; Schörkhuber, D.; Nezveda, M.; Stiedl, F.; Schimkowitsch, M.; Gelautz, M. Transfer Learning for Driver Pose Estimation from Synthetic Data. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE Intelligent Vehicles Symposium (IV), Anchorage, AK, USA, 4–7 June 2023; pp. 1–7. [Google Scholar]

- Rotem, Y.; Shimoni, N.; Rokach, L.; Shapira, B. Transfer Learning for Time Series Classification Using Synthetic Data Generation. In Proceedings of the Cyber Security, Cryptology, and Machine Learning, Be’er Sheva, Israel, 19–20 December 2024; Dolev, S., Katz, J., Meisels, A., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2022; pp. 232–246. [Google Scholar]

| Ground Sampling Distance | Ground | Rooftop | Total |

|---|---|---|---|

| PV01 (0.1 m) | 0 | 645 | 645 |

| PV03 (0.3 m) | 2122 | 186 | 2308 |

| PV08 (0.8 m) | 673 | 90 | 763 |

| Total | 3716 | ||

| Iteration | Type of Synthetic Data | Included in Training Data | Included in Validation Data | Included in Testing Data |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | AI-generated | Yes | Yes | No |

| 2 | AI-generated | Yes | No | No |

| 3 | AI-generated | No | Yes | No |

| 4 | Phy-based | Yes | Yes | No |

| 5 | Phy-based | Yes | No | No |

| 6 | Phy-based | No | Yes | No |

| 7 | Phy-based + AI-generated | Yes | Yes | No |

| Real EO Data | Evaluation Metrics [%] | ID | Combination of Synthetic Data | Evaluation Metrics [%] | Performance Comparison | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train. | Valid. | Test | Pr. | Re. | mAP50 | mAP95 | Train. | Valid. | Pr. | Re. | mAP50 | mAP95 | Pr. | Re. | mAP50 | mAP95 | |

| Jiang | Jiang | Jiang | 88.5 | 80.6 | 85.9 | 74.4 | EX.1 | Phy | Phy | 90.8 | 80.2 | 86.6 | 74.8 | +2.3 | −0.4 | +0.7 | +0.4 |

| EX.2 | AI (100%) | AI (100%) | 90.9 | 79.3 | 85.5 | 74.3 | +2.4 | −1.3 | −0.4 | −0.1 | |||||||

| EX.3 | AI (3 x real) | AI (3 x real) | 88.0 | 82.5 | 86.1 | 74.9 | −0.5 | +1.9 | +0.2 | +0.5 | |||||||

| Jiang PV08 | Jiang PV08 | Jiang PV08 | 84.1 | 67.1 | 74.0 | 60.3 | EX.4 | Phy | Phy | 84.6 | 66.3 | 74.7 | 60.9 | +0.5 | −0.8 | +0.7 | +0.6 |

| EX.5 | AI (3 x real) | AI (3 x real) | 81.9 | 69.2 | 74.0 | 60.0 | −2.2 | +2.1 | 0.0 | −0.3 | |||||||

| EX.6 | Phy | Only real | 79.3 | 70.6 | 75.4 | 61.5 | −4.8 | +3.5 | +1.4 | +1.2 | |||||||

| EX.7 | AI (2 x real) | Only real | 87.0 | 66.2 | 74.9 | 60.6 | +2.9 | −0.9 | +0.9 | +0.3 | |||||||

| EX.8 | Phy + AI (3 x real) | Phy + AI (3 x real) | 80.9 | 69.2 | 75.6 | 61.5 | −3.2 | +2.1 | +1.6 | +1.2 | |||||||

| Jiang PV08 | Jiang PV08 | Jiang PV08 | 75.1 | 59.0 | 65.0 | 49.2 | EX.9 | AI (Yrec) | AI (Yrec) | 76.4 | 62.3 | 67.1 | 52.3 | +1.3 | +3.3 | +2.1 | +3.1 |

| EX.10 | AI (Yrec) | Only real | 75.2 | 59.2 | 65.2 | 50.3 | +0.1 | +0.2 | +0.2 | +1.1 | |||||||

| More test samples– less training and validation | EX.11 | Phy | Only real | 73.2 | 60.8 | 65.1 | 50.4 | −1.9 | +1.8 | +0.1 | +1.2 | ||||||

| EX.12 | Phy + AI (Yrec) | Phy + AI (Yrec) | 76.8 | 62.9 | 67.3 | 52.5 | +1.7 | +3.9 | +2.3 | +3.3 | |||||||

| No. of Epochs | Weights Initialization | Pr. [%] | Re. [%] | mAP50 [%] | mAP95 [%] |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 5 | With synthetic data included | 57.7 | 44.0 | 44.4 | 31.0 |

| Without synthetic data included | 14.7 | 54.5 | 10.8 | 7.1 | |

| 100 | With synthetic data included | 76.1 | 61.1 | 66.6 | 50.7 |

| Without synthetic data included | 75.1 | 59.0 | 65.0 | 49.2 |

| Hyperparameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Weights initialization | YOLOv8-m |

| Image size | 512 |

| Batch size | 16 |

| Number of epochs | 100 |

| Early Stopping | Yes |

| Hyperparameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Weights initialization | YOLOv8-n |

| Image size | 512 |

| Number of epochs | 100 |

| Number of learning steps per epoch | 35–36 |

| Batch size | Benchmark: 16 EX.4.2 and EX.6.2: 44 EX.5.2 and EX.8.2: 60 EX.7.2: 30 |

| Hyperparameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Weights initialization | YOLOv8-m |

| Image size | 512 |

| Number of epochs | Benchmark: 100 EX.4.3 and EX.6.3: 37 EX.5.3 and EX.8.3: 27 EX.7.3: 52 |

| Number of learning steps per epoch | 35–36 |

| Batch size | 16 |

| Real EO Data | Evaluation Metrics [%] | ID | Combination of Synthetic Data | Evaluation Metrics [%] | Performance Comparison | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train. | Valid. | Test | Pr. | Re. | mAP50 | mAP95 | Train. | Valid. | Pr. | Re. | mAP50 | mAP95 | Pr. | Re. | mAP50 | mAP95 | |

| Jiang PV08 | Jiang PV08 | Jiang PV08 | 84.0 | 63.0 | 72.0 | 57.2 | EX.4.2 | Phy | Phy | 79.8 | 67.8 | 72.5 | 57.3 | −4.2 | +4.8 | +0.5 | +0.1 |

| EX.5.2 | AI (3 x real) | AI (3 x real) | 81.7 | 66.9 | 72.5 | 58.4 | −2.3 | +3.9 | +0.5 | +1.2 | |||||||

| EX.6.2 | Phy | Only real | 78.8 | 66.7 | 71.8 | 56.2 | −5.2 | +3.7 | −0.2 | −1.0 | |||||||

| EX.7.2 | AI (2 x real) | Only real | 77.9 | 67.1 | 71.6 | 57.0 | −6.1 | +4.1 | −0.4 | −0.2 | |||||||

| EX.8.2 | Phy + AI (3 x real) | Phy + AI (3 x real) | 80.8 | 65.7 | 71.5 | 56.6 | −3.2 | +2.7 | −0.5 | −0.6 | |||||||

| Real EO Data | Evaluation Metrics [%] | ID | Combination of Synthetic Data | Evaluation Metrics [%] | Performance Comparison | ||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Train. | Valid. | Test | Pr. | Re. | mAP50 | mAP95 | Train. | Valid. | Pr. | Re. | mAP50 | mAP95 | Pr. | Re. | mAP50 | mAP95 | |

| Jiang PV08 | Jiang PV08 | Jiang PV08 | 84.1 | 67.1 | 74.0 | 60.3 | EX.4.3 | Phy | Phy | 83.1 | 68.8 | 73.2 | 58.5 | −1.0 | +1.7 | −0.8 | −1.8 |

| EX.5.3 | AI (3 x real) | AI (3 x real) | 78.8 | 66.3 | 71.8 | 57.4 | −5.3 | −0.8 | −2.2 | −2.9 | |||||||

| EX.6.3 | Phy | Only real | 83.1 | 68.8 | 73.2 | 58.5 | −1.0 | +1.7 | −0.8 | −1.8 | |||||||

| EX.7.3 | AI (2 x real) | Only real | 86.8 | 64.9 | 73.3 | 59.2 | +2.7 | −2.2 | −0.7 | −1.1 | |||||||

| EX.8.3 | Phy + AI (3 x real) | Phy + AI (3 x real) | 79.8 | 66.7 | 71.0 | 56.4 | −4.3 | −0.4 | −3.0 | −3.9 | |||||||

| Aspect | Physically Based (Unity, PBR) | AI-Generated (Stable Diffusion XL/DALL·E 3) |

|---|---|---|

| Control over geometry and annotations | Full and deterministic | Limited; requires manual verification |

| Visual realism | High, consistent illumination and materials | Very high, natural textures and diversity |

| Diversity of scenes | Limited by 3D assets and procedural rules | Very high; depends on prompt variety and seeds |

| Computational cost | Moderate; efficient rendering in practice | Moderate; inference on GPU once fine-tuned |

| Scalability | Scalable via procedural scene generation | Highly scalable once model is trained |

| Reproducibility | Fully reproducible | Partially stochastic |

| Best observed effect on model performance | Higher precision | Higher recall |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).

Share and Cite

Hisam, E.; Gimeno, J.; Miraut, D.; Pérez-Aixendri, M.; Fernández, M.; Gini, R.; Rodríguez, R.; Meoni, G.; Seker, D.Z. Impact of Synthetic Data on Deep Learning Models for Earth Observation: Photovoltaic Panel Detection Case Study. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 481. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120481

Hisam E, Gimeno J, Miraut D, Pérez-Aixendri M, Fernández M, Gini R, Rodríguez R, Meoni G, Seker DZ. Impact of Synthetic Data on Deep Learning Models for Earth Observation: Photovoltaic Panel Detection Case Study. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information. 2025; 14(12):481. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120481

Chicago/Turabian StyleHisam, Enes, Jesus Gimeno, David Miraut, Manolo Pérez-Aixendri, Marcos Fernández, Rossana Gini, Raúl Rodríguez, Gabriele Meoni, and Dursun Zafer Seker. 2025. "Impact of Synthetic Data on Deep Learning Models for Earth Observation: Photovoltaic Panel Detection Case Study" ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information 14, no. 12: 481. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120481

APA StyleHisam, E., Gimeno, J., Miraut, D., Pérez-Aixendri, M., Fernández, M., Gini, R., Rodríguez, R., Meoni, G., & Seker, D. Z. (2025). Impact of Synthetic Data on Deep Learning Models for Earth Observation: Photovoltaic Panel Detection Case Study. ISPRS International Journal of Geo-Information, 14(12), 481. https://doi.org/10.3390/ijgi14120481