1. Introduction

Pedestrian detection plays a vital role in many computer vision applications, including intelligent transportation systems [

1,

2,

3,

4,

5], urban surveillance [

6,

7], and public safety [

8,

9]. In high-density transportation environments, especially urban rail transit systems, accurate and robust pedestrian detection is crucial for ensuring operational safety and enabling rapid emergency response. According to official statistics [

10], by the end of 2024, China’s urban rail network had recorded 40.85 million cumulative train operations and 32.24 billion passenger journeys, representing a 9.5% year-on-year increase. This rapid growth highlights both the expanding role of rail transit and the increasing difficulty of safety monitoring and crowd management in complex scenes such as large transit hubs and surrounding commercial districts. In parallel, deep learning has also shown strong potential in other safety-critical monitoring tasks, for example in interpretable bearing fault diagnosis under zero-fault samples using physical constraint-guided quadratic neural networks [

11], further underscoring the need for reliable and task-adaptive models in real-world deployment.

Traditional pedestrian detectors [

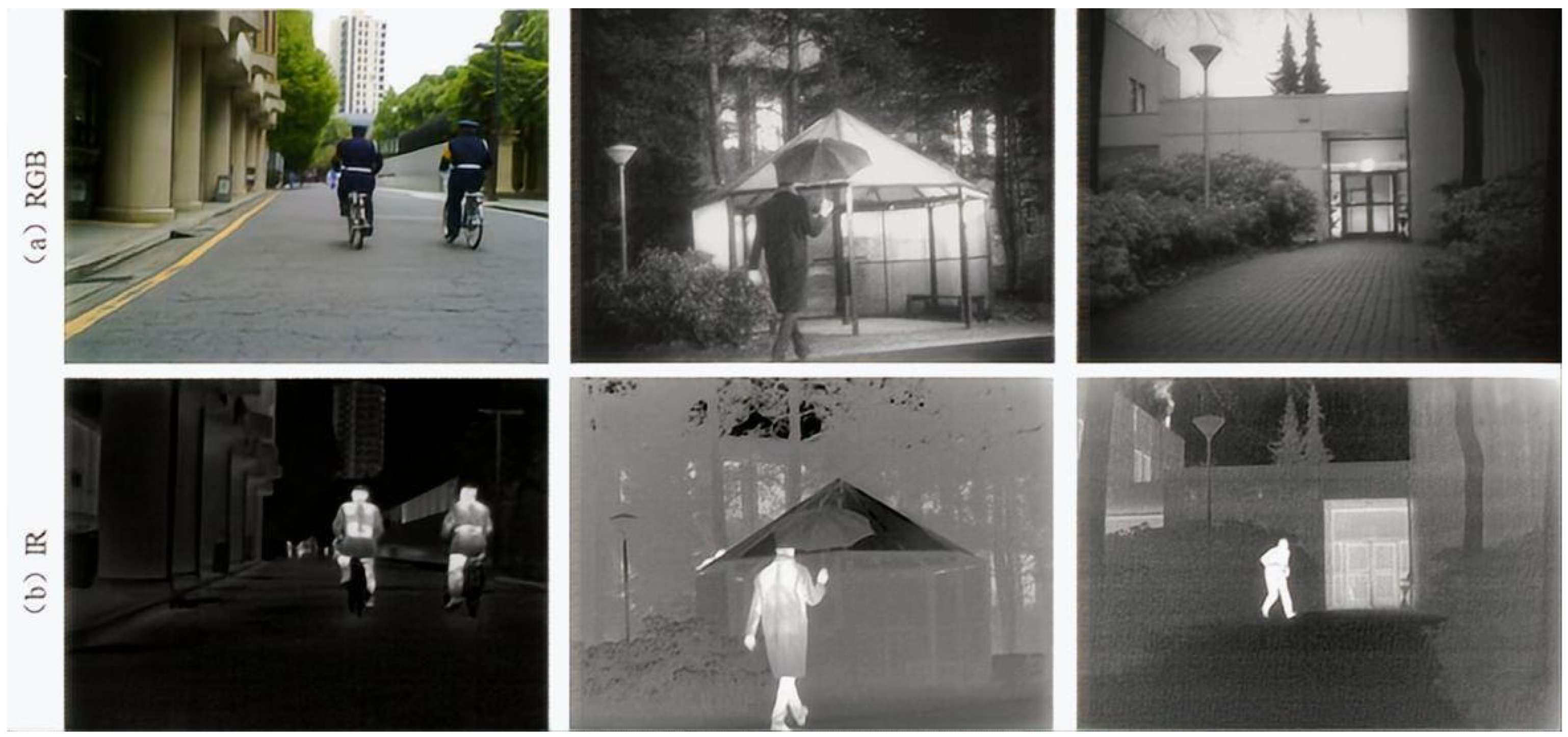

12] predominantly rely on visible-spectrum imagery because of its high spatial resolution and rich texture and color cues, but their performance degrades severely under low illumination, occlusion, and adverse weather. In practice, two factors are particularly critical: (i) the large intra-class appearance variance of pedestrians caused by diverse clothing, scale changes, pose variations, and different levels of occlusion; and (ii) complex background clutter in both visible and infrared images. Infrared (IR) imaging, which captures thermal radiation, can mitigate some of these issues by highlighting heat-emitting targets such as humans regardless of ambient lighting, as illustrated in

Figure 1, where visible images provide finer details under good illumination, while IR images maintain clearer target contrast under poor lighting. However, IR images typically suffer from low spatial resolution, weak texture, and interfering background heat sources (e.g., vehicle engines or sun-heated building facades) that produce human-like thermal signatures. These modality-specific yet complementary strengths and weaknesses motivate the development of robust RGB–IR fusion strategies for pedestrian detection.

To overcome these limitations, multimodal fusion of visible and infrared modalities has become an active research direction [

13,

14,

15]. These modalities are inherently complementary: visible images provide structural details, while infrared images offer thermal contrast. Effective fusion can exploit this complementarity to enhance feature representation and improve detection robustness in complex conditions. However, naive fusion strategies may introduce modality noise or redundant information. Furthermore, conventional CNN-based fusion networks struggle to capture long-range contextual dependencies, which are crucial for discriminating pedestrians from cluttered backgrounds.

In this work, we propose IVIFusion, a lightweight and robust pedestrian detection framework tailored for challenging environments. IVIFusion integrates three key components: a dual-branch Transformer-based backbone for modality-specific feature extraction; a Cross-Modality Attention Fusion Module (CMAFM) for dynamic and selective fusion of infrared and visible features; and a small-object detection layer to improve the detection of distant or occluded pedestrians. The entire architecture is optimized for both accuracy and efficiency.

Extensive experiments on the public LLVIP dataset and the custom HGPD dataset validate the effectiveness of the proposed method, demonstrating superior performance compared to mainstream single- and multi-modal detectors. The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

We propose IVIFusion, a Transformer-based dual-branch architecture that independently extracts features from infrared and visible modalities, preserving modality-specific semantics and enabling effective global context modeling.

We design a Cross-Modality Attention Fusion Module (CMAFM) that adaptively learns cross-modal correlations and selectively integrates complementary information while suppressing redundant or noisy features.

We introduce a small-object detection layer to improve the network’s sensitivity to small-scale or occluded pedestrians, which are often missed in conventional downsampled feature maps.

We construct a real-world dataset (HGPD) for pedestrian detection in low-light station environments and perform comprehensive experiments on HGPD and LLVIP, achieving state-of-the-art performance with competitive computational efficiency.

2. Related Works

2.1. Traditional Image Fusion Methods

Traditional image fusion methods typically process images from different modalities or viewpoints by extracting salient features and combining them through predefined fusion rules such as weighted averaging, maximum selection, or other deterministic strategies. Among these, multi-scale transform methods, such as pyramid, wavelet, and contourlet transforms, have been widely adopted. For example, some approaches leverage Non-Subsampled Shearlet Transform (NSST) to capture multi-scale, multi-directional details, while incorporating Robust Principal Component Analysis (RPCA) to extract low-rank and sparse components, effectively suppressing background interference and enhancing target saliency [

16]. Other studies employ attribute filtering to preserve structural consistency while reducing noise, thereby improving the perceptual quality of the fused image [

17]. Despite their interpretability and effectiveness in specific conditions, these traditional methods typically require manual design of fusion strategies and suffer from limited adaptability and generalization, particularly in dynamic or real-time environments.

2.2. CNN-Based Fusion Methods

In recent years, deep learning [

18,

19,

20,

21] has opened new avenues for image fusion. One of the early studies introduced multimodal feature fusion in object detection by adopting a dual-branch network and comparing early and late fusion strategies, concluding that late fusion produced superior results [

22]. Follow-up works based on the Faster R-CNN framework explored different fusion stages, showing that intermediate-level fusion outperforms both early and late fusion by enabling better cross-modal interaction [

23,

24]. Additionally, some studies constructed dual-branch frameworks for infrared and visible fusion, confirming the feasibility of data-level fusion under low-light conditions [

13].

However, direct stacking of features from different modalities can lead to redundancy and even degrade overall performance. To address this, correlation-driven feature decomposition strategies have been proposed, aiming to retain modality-specific representations while enhancing cross-modal complementarity [

25]. While these approaches have improved pedestrian detection accuracy, they often suffer from increased parameter counts and computational complexity. To tackle multi-scale fusion challenges, other efforts introduced multi-level fusion and dual-modulation modules to dynamically adjust spectral weights, thus improving robustness under occlusion [

26]. Bidirectional interaction mechanisms have also been proposed to enhance target saliency between modalities [

27], while lightweight modules or illumination-aware designs have been incorporated to mitigate missed detections in dark areas [

28]. Recent works, such as FusionMamba [

29], integrate dynamic convolution and channel attention within vision state-space models to balance local and global representations. To further improve detection of small and distant targets, some methods utilize long-range attention across spatial and channel dimensions [

30], or combine global context and local detail to handle scale variations and occlusion [

31].

Although these CNN-based approaches have yielded promising results in various scenarios, most still rely heavily on dense convolutional structures, limiting their ability to model global dependencies and increasing inference latency in real-time applications.

2.3. Transformer-Based Image Fusion Methods

With the convergence of interdisciplinary research, the success of Transformer architectures in natural language processing has sparked widespread interest in their application to computer vision. Unlike traditional convolutional networks, Transformers are capable of modeling global contextual dependencies and long-range interactions, which are particularly beneficial for multimodal pedestrian detection in complex scenes.

Khan et al. [

32] provided a comprehensive survey of Vision Transformers (ViTs), highlighting their potential for large-scale image recognition tasks and laying a theoretical foundation for infrared–visible fusion. Tang et al. [

33] proposed DATFuse, which employs dual-attention Transformer modules to achieve high-quality image fusion. Li et al. [

34] developed CGTF, a hybrid architecture combining CNNs for local feature extraction with Transformers for global representation, thereby enhancing both detail preservation and holistic semantics. While Transformer-based methods show strong potential, they are often limited by their high computational complexity, especially when applied to high-resolution images. To address this, Liu et al. [

35] explored lightweight Transformer designs and leveraged neural architecture search (NAS) to improve efficiency. Nonetheless, achieving robust fusion performance under constrained resources remains a challenge. Moreover, Transformer models typically rely on large-scale datasets for training, whereas most publicly available infrared–visible datasets are relatively small, which increases the risk of overfitting and reduces generalization.

Therefore, it is essential to develop efficient, lightweight, and adaptive Transformer-based fusion frameworks that can effectively capture cross-modal features while maintaining competitive accuracy and computational feasibility in real-world applications.

3. Methods

3.1. Proposed Framework

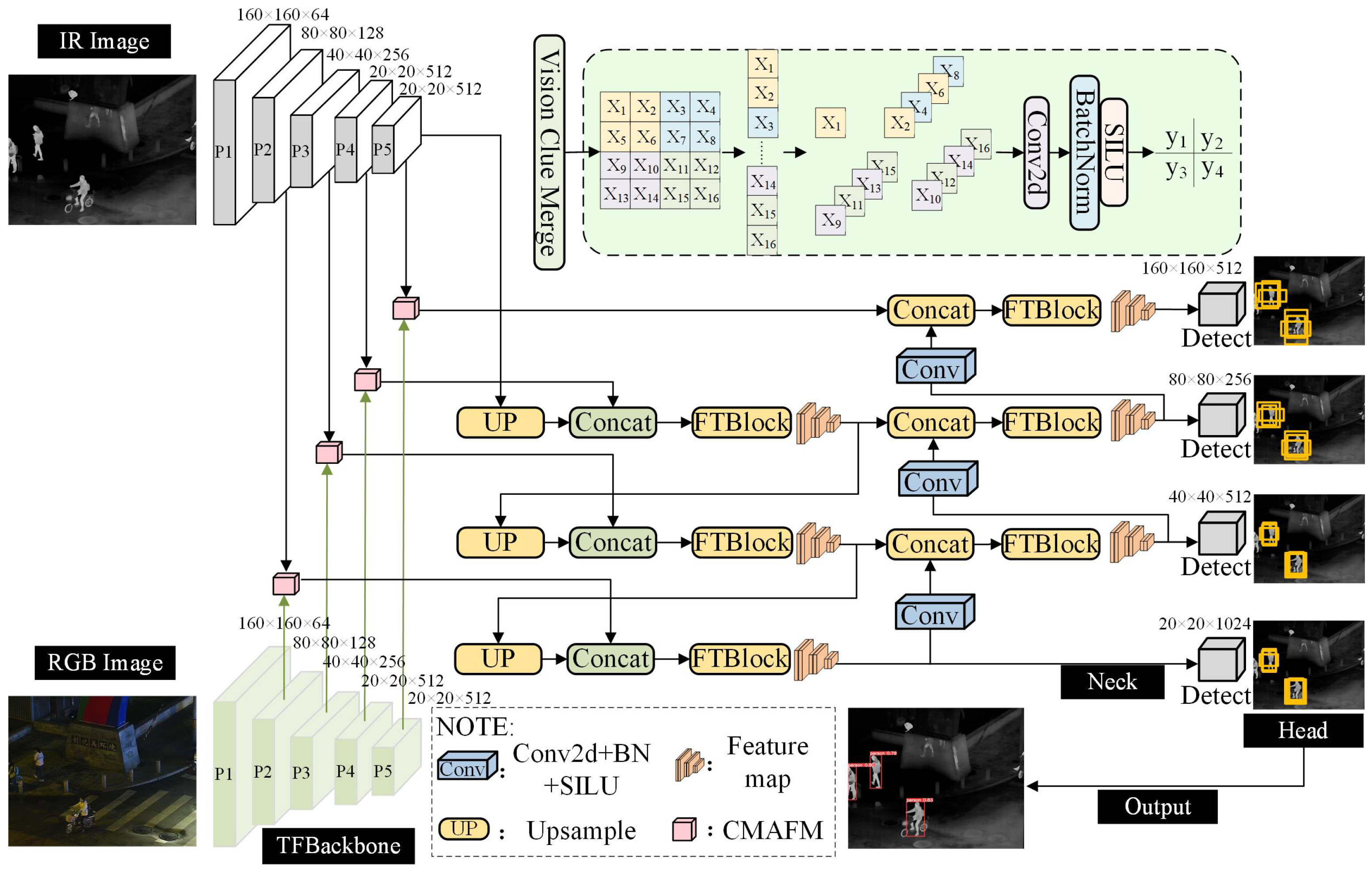

Based on the challenges of pedestrian detection under nighttime and adverse weather conditions discussed in the previous section, we propose a robust detection algorithm named IVIFusion, which integrates infrared and visible light images through a cross-modal fusion strategy. The TFBackbone in

Figure 2 is responsible for extracting multi-scale features. Its detailed internal architecture, including the specific placement of the Vision Clue Merge (VCM) and Spatial Pyramid Pooling-Fast (SPPF) modules, is illustrated in

Figure 3 and summarized in

Table 1. The design leverages the complementary nature of different spectral modalities to enhance detection performance in low-light and complex environments.

The IVIFusion framework adopts a dual-branch Transformer-based backbone to separately extract deep semantic features from visible and infrared images. This design ensures that modality-specific characteristics are preserved while enabling strong global context modeling. Mathematically, given an input pair of visible and infrared images

, the dual backbones can be represented as:

where

and

denote the Transformer feature extraction networks for visible and infrared branches, respectively, and

,

are the resulting high-level feature maps.

To fuse these representations effectively, we introduce a Cross-Modality Attention Fusion Module (CMAFM), which adaptively learns inter-modal relevance and assigns attention weights across channels and spatial locations. The fused representation

is obtained as:

where

denotes the attention-based fusion function implemented in CMAFM. This operation enables the model to emphasize informative features while suppressing irrelevant or noisy signals from each modality.

Following the fusion, the network employs a neck module for multi-scale feature refinement and then dispatches the processed features to four detection heads operating at different scales (160 × 160, 80 × 80, 40 × 40, and 20 × 20) to detect pedestrians of various sizes. This multi-resolution strategy ensures robustness in detecting both small and large-scale targets. To facilitate implementation and reproducibility, the overall IVIFusion-based infrared–visible pedestrian detection procedure is summarized in Algorithm 1.

| Algorithm 1: IVIFusion-based Infrared–Visible Pedestrian Detection |

- Require:

Paired visible/infrared images ; annotations (training only); model parameters ; learning rate - Ensure:

Final pedestrian detections - 1:

Preprocess and (resize, normalize, augmentation). - 2:

for each mini-batch do - 3:

Dual-branch feature extraction (TFBackbone): - 4:

Extract multi-scale features from each modality: - 5:

, . - 6:

Cross-modality attention fusion (CMAFM): - 7:

For each scale , obtain fused features . - 8:

Neck and multi-scale detection: - 9:

Feed into the neck and SPPF to produce multi-scale features . - 10:

Apply four detection heads on , where the head on is the small-object detection layer (SODL), to obtain raw predictions at all scales. - 11:

if training phase then - 12:

Compute detection loss (classification, localization, objectness) using . - 13:

Update parameters . - 14:

else - 15:

Apply non-maximum suppression (NMS) on multi-scale predictions to obtain final detections . - 16:

end if - 17:

end for - 18:

return .

|

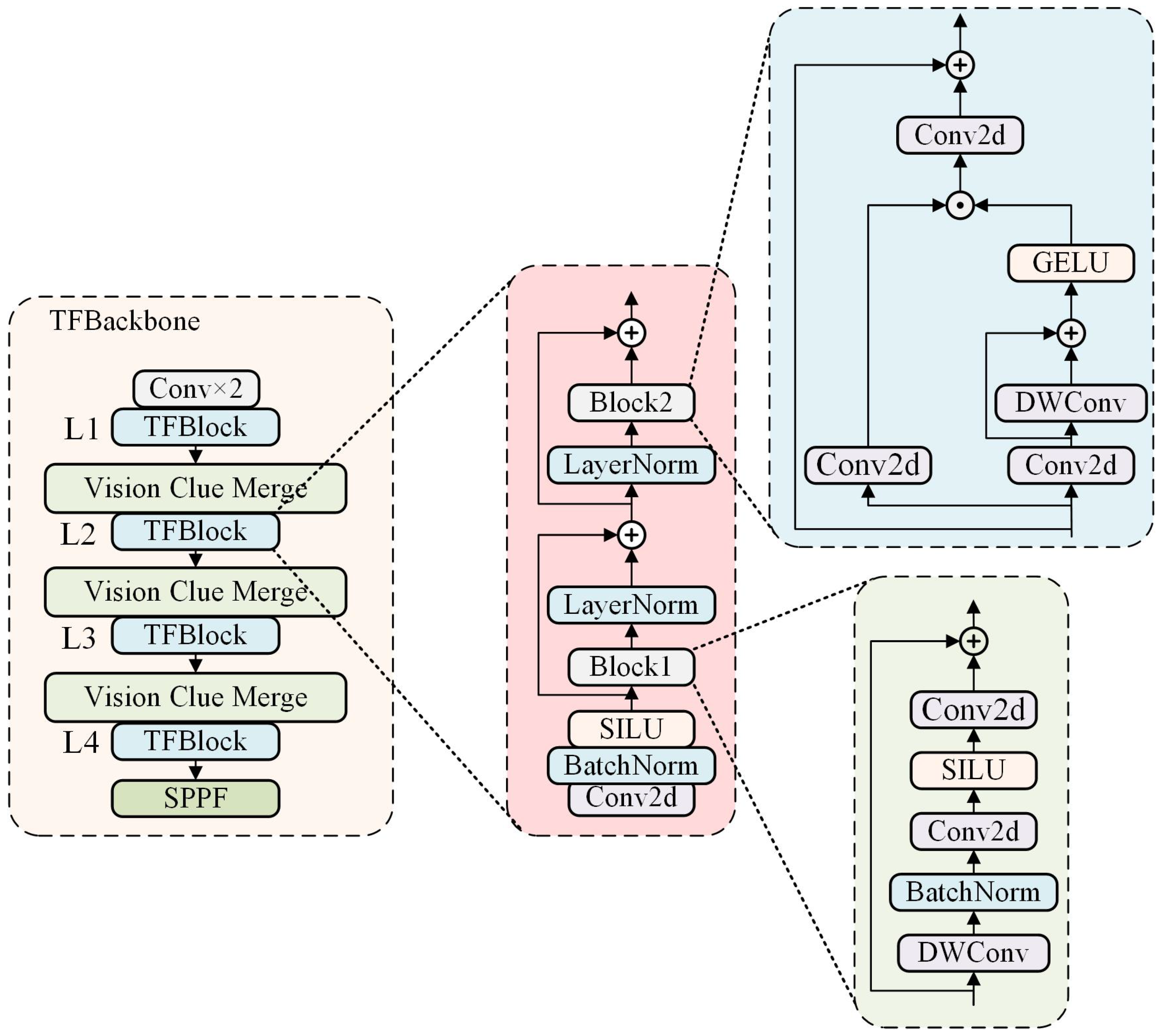

3.2. Transformer-Based Feature Extraction Backbone

To address the challenges of long-range dependency modeling and fine-grained representation under complex scenes, a Transformer-based feature extraction backbone (TFBackbone) is designed, as shown in

Figure 3. The backbone adopts a hierarchical structure and incorporates both local spatial detail extraction and global context modeling, aiming to improve representation quality under varying illumination and occlusion.

3.2.1. TFBlock Structure

To effectively capture both local structures and global dependencies in multimodal pedestrian detection, we design a hybrid module named TFBlock, which integrates a Local Structure Block (LSBlock) and a Residual Global Block (RGBlock) in a parallel residual manner, as illustrated in

Figure 3. This dual-branch design is conceptually related to the recent MambaYOLO [

29], which leverages a hybrid local–global architecture to combine a convolutional branch with a state-space Mamba branch for efficient object detection. Similar to MambaYOLO, the TFBackbone employs a local path that focuses on fine-grained spatial details and a global path that models long-range dependencies: the LSBlock plays a role analogous to the local convolutional branch and we also adopt the Vision Clue Merge (VCM) module to adjust feature-map resolution while preserving structural information. Despite this connection, TFBackbone differs from MambaYOLO in several key aspects. First, the two architectures adopt fundamentally different paths for global dependency modeling: MambaYOLO relies on state-space Mamba blocks for long-sequence modeling, whereas our residual global block (RGBlock) follows a Transformer/MLP-inspired design with hierarchical projections and gating to capture global semantic relations. Second, MambaYOLO is built as a generic single-modal (RGB) detector, while TFBackbone is specifically designed for dual-modal infrared–visible fusion, with the explicit goal of providing complementary feature streams for the subsequent CMAFM module. Third, at the implementation level, RGBlock employs a Hadamard-product-based gating fusion mechanism, which is structurally distinct from the linear time-varying state-space modeling used in MambaYOLO.

Local Structure Block (LSBlock). The LSBlock is designed to preserve spatial locality using a depthwise separable convolution stack. We define the block as a composite mapping function with residual formulation:

where

denotes depthwise convolution with learnable parameters

,

and

represent two

pointwise convolutions with SiLU activation

inserted between them, and BN denotes batch normalization. The final residual addition ensures feature reuse and stable gradient flow.

Residual Global Block (RGBlock). To enhance global semantic modeling, RGBlock incorporates hierarchical projection, depthwise context interaction, and gated fusion. The block is formalized as:

where:

is the primary projection;

applies residual-enhanced depthwise context encoding;

is a gating branch;

denotes GELU activation;

fuses the gated representation;

⊙ indicates Hadamard (element-wise) multiplication.

This hybrid block structure allows TFBlock to capture complementary features in both spatial and semantic domains with minimal computational overhead.

3.2.2. Backbone Layer Composition and Resolution Strategy

The overall TFBackbone follows a multi-stage architecture with four levels of feature abstraction (L1–L4), where each level comprises multiple TFBlocks followed by a resolution adjustment operation. The layer-wise configuration is presented in

Table 1.

To manage spatial resolution across stages, we adopt the Vision Clue Merge (VCM) [

29] module instead of conventional strided convolutions. VCM aims to reduce spatial dimension while preserving structural integrity and semantic consistency. Given feature map

, we partition it into

non-overlapping local windows

of size

. Each local window is independently transformed using a

projection layer:

where

and

are learnable weights and biases for the

k-th region. This approach enables localized attention and avoids feature distortion near object boundaries. The concatenated result

is reshaped into a coarser-resolution feature map.

Finally, a Spatial Pyramid Pooling—Fast (SPPF) [

36] module is applied at the final stage to gather multi-scale contextual information using a fixed pooling kernel sequence. This enhances the receptive field without increasing network depth or computation.

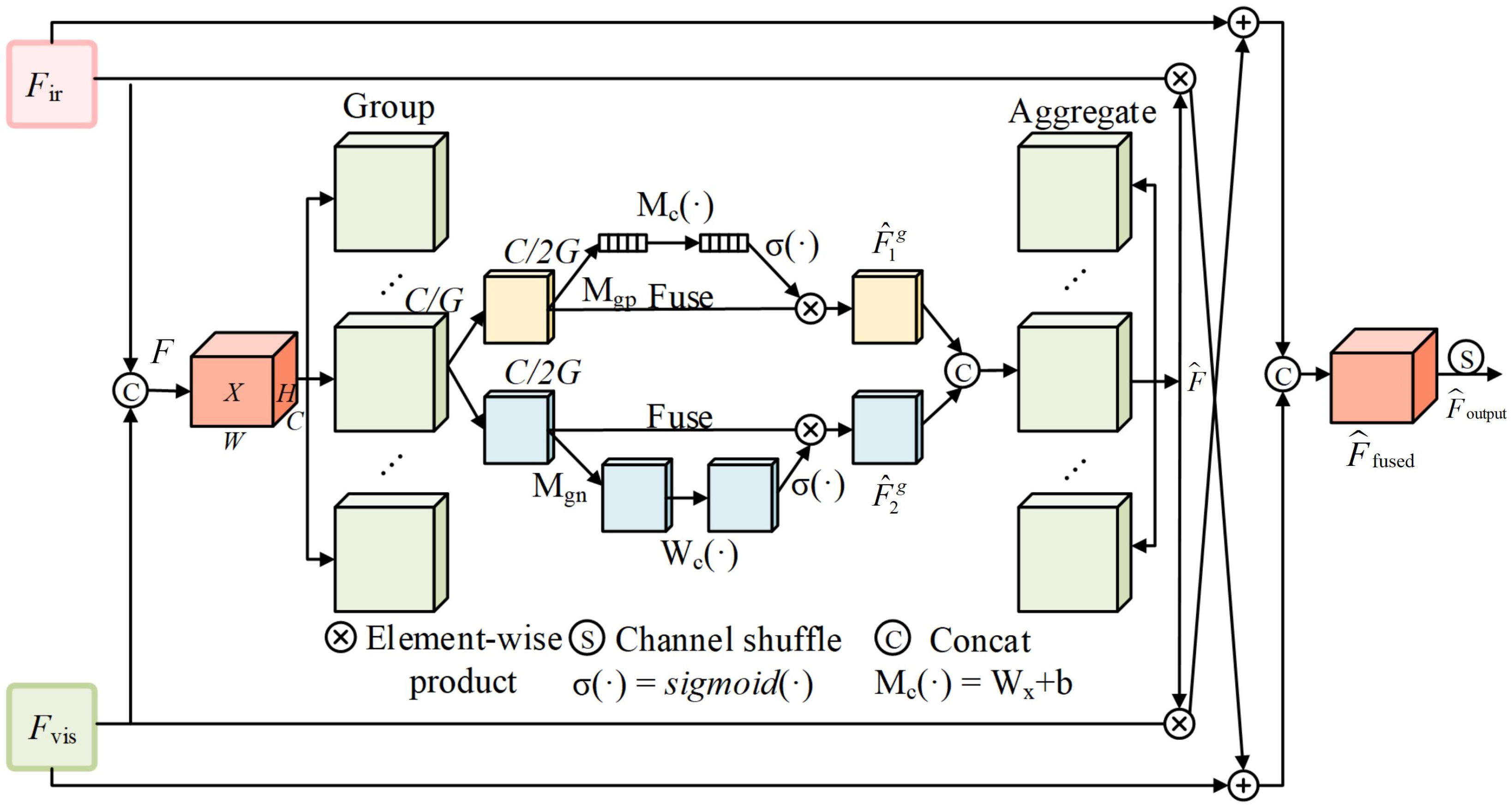

3.3. Cross-Modality Attention Fusion Module

To effectively integrate complementary information from infrared (IR) and visible (RGB) modalities while suppressing modality-specific noise, we propose a Cross-Modality Attention Fusion Module (CMAFM), which dynamically learns to focus on informative features across spatial and channel dimensions. As illustrated in

Figure 4, the fusion process is performed in a group-wise attention manner for computational efficiency and better modality disentanglement.

Grouped Cross-Attention. Given two modality-specific features

and

, we first concatenate them along the channel axis to obtain:

We then evenly divide F into G groups along the channel dimension, producing , with each group .

Intra-Group Attention and Modulation. Each sub-feature group

is further split into two branches:

and

. The first branch applies global average pooling (GAP) followed by a channel-wise scaling function:

The second branch employs GroupNorm followed by affine transformation and gating:

Modality-Gated Fusion. After obtaining the cross-modality attention map

, we use it as a shared gating mask to adaptively modulate the contributions of the infrared and visible features. Specifically, we construct two complementary fusion branches: one is infrared-dominant and the other is visible-dominant. The fused representation is given by

where ⊙ denotes element-wise multiplication and “Shuffle” denotes channel shuffle along the channel dimension. In this way, each modality is enhanced by the attention-guided features of the other modality while retaining its own information, and the subsequent channel shuffle further promotes interaction and diversity across channels, leading to a more discriminative fused representation.

3.4. Small Object Detection Layer

Detecting small-scale pedestrian instances remains a common challenge, particularly under low-light conditions or partial occlusion, due to limited pixel coverage and reduced semantic activation. When projected onto feature maps with large downsampling factors (e.g., or ), such targets may fall below the spatial granularity of the receptive field, making it difficult to retain sufficient information for accurate detection.

To mitigate this, we introduce a Small Object Detection Layer (SODL), as shown in

Figure 5, which operates on a shallow feature map

corresponding to a

downsampling. This design follows prior observations that spatial resolution plays a key role in the detection accuracy of small objects [

37]. With this addition, the network performs detection at four scales:

where

denotes the detection head at scale

s.

Small-object definition and detection head. In our setting, a pedestrian is regarded as a small object if its bounding-box area in the input image is smaller than pixels, which is consistent with common practice in object detection. In a standard detection neck that only uses prediction heads at resolutions, such small targets may shrink to only a few pixels (e.g., a pedestrian becomes pixels on a feature map), causing severe loss of spatial detail. To alleviate this issue, we introduce an additional prediction head at the (-scale) feature map, termed the small-object detection layer (SODL), which is attached to shallower backbone features rich in edges and textures. This design helps preserve fine-grained cues and improves recall for small and partially occluded pedestrians.

3.5. Loss Fuction

To train IVIFusion, we adopt a multi-task loss that jointly supervises bounding-box regression, objectness, and classification. The overall loss is defined as

where the weights are empirically set to

to emphasize localization accuracy.

For bounding-box regression, we combine Distribution Focal Loss (DFL) and Complete IoU loss (CIoU) to better handle small and partially occluded pedestrians:

DFL models the discrete distribution of box coordinates and provides richer gradients for fine localization, while CIoU jointly considers overlap, center distance, and aspect ratio.

To address the severe foreground–background imbalance in pedestrian scenes, both the objectness and classification branches are optimized with focal loss [

38]:

4. Experimental Setup

4.1. Datasets

LLVIP dataset. LLVIP [

39] is an infrared visible image dataset containing a large number of infrared visible images with annotated pedestrians.The image data are derived from images of pedestrians and bicyclists captured from different locations on the street between 6:00 and 10:00 p.m. The fineness and normalization of this dataset are the highest of all visible infrared image datasets currently available. LLVIP contains 15,488 pairs of infrared visible images with a resolution of 1920 × 1080 for the original visible images and 1280 × 720 for the infrared images. The dataset is randomly split into training, validation, and test sets with an 8:1:1 ratio, and the splitting is carried out to maintain a consistent data distribution across the subsets.

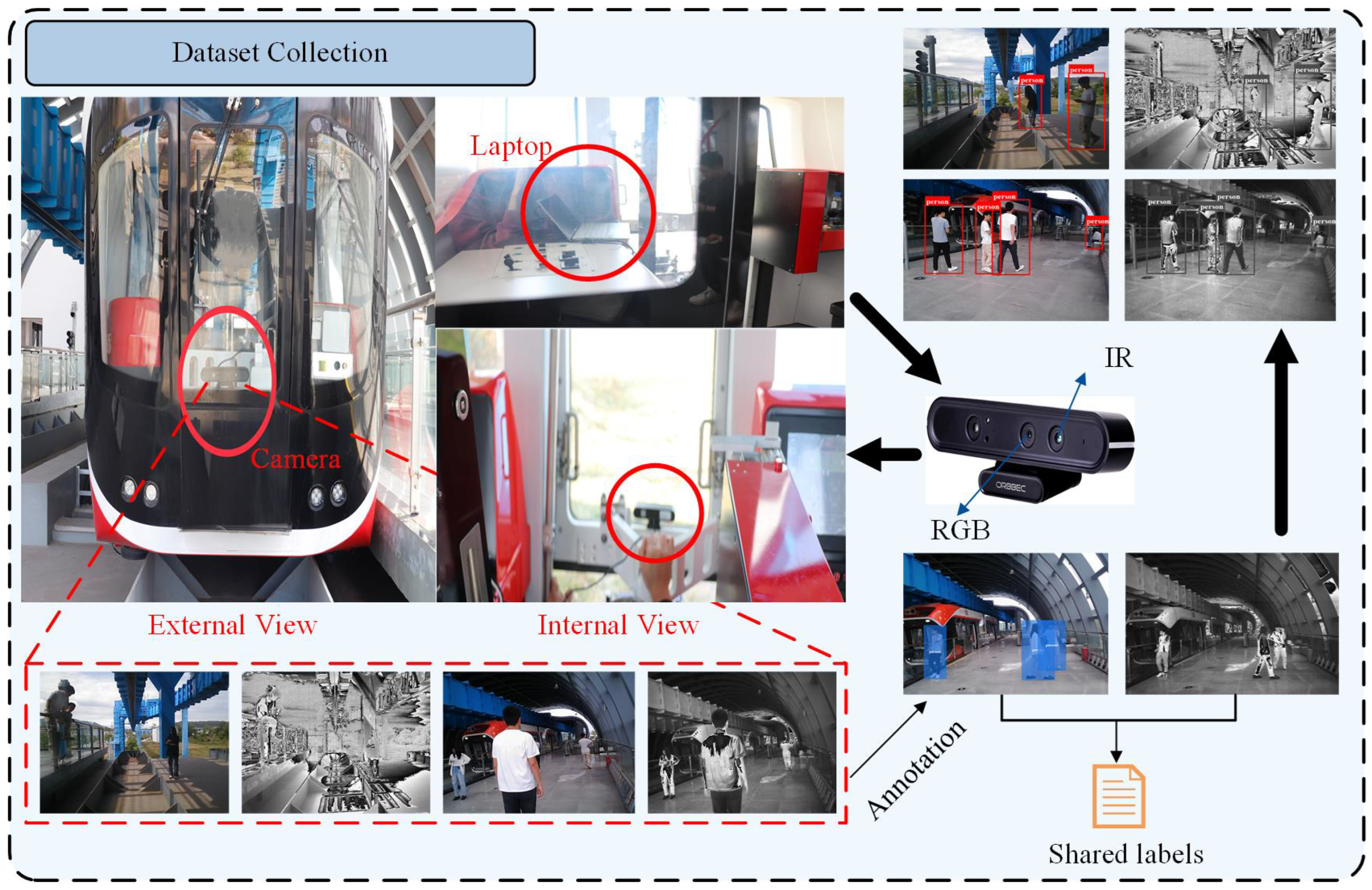

HGPD dataset. To support our experiments on RGB–IR pedestrian detection under low-light conditions, we collect a small RGB–IR dataset, denoted HGPD. An Orbbec Astra Pro sensor, which integrates an RGB camera and an IR camera, is mounted on the front of the monorail cabin and connected to a laptop for synchronized acquisition of paired images, as illustrated in

Figure 6. We record videos on station platforms and in similar public scenes under different illumination conditions (e.g., normal daylight, dim lighting, strong backlight) and sample frames at regular intervals to reduce redundancy. This process yields 7571 aligned RGB–IR image pairs containing pedestrians. Each pair is annotated with axis-aligned bounding boxes for a single person class. The dataset is randomly split into training, validation and test sets with an 8:1:1 ratio, and the partition is performed to keep the scene and illumination distributions roughly similar across the three subsets.

4.2. Implementation Details

The algorithms in this paper are implemented in Visual Studio Code integrated software, the programming language used is Python 3.6.9, the deep learning framework and version is Pytorch 1.8.2, and CUDA 10.2 hardware acceleration tools are used. The experimental platform computer uses an Intel Core I7-7700 processor, NVIDIA Tesla-P100. For training, the input image is set to 640 × 640, and SGD is used as the optimization function to train the model, and the model training epoch is 200, and 16 images are trained in each batch, with the learning rate set to 0.01.

For training and evaluation, all input images were resized to a fixed resolution of 640 × 640, consistent with the standard practice in modern object detection to enable batched processing. It is important to note that all models in our comparative study were subjected to this identical preprocessing. The predicted bounding boxes were subsequently scaled back to the original image dimensions for evaluation. This ensures a fair and equitable comparison, as any potential impact from resizing is applied uniformly, allowing the reported performance to genuinely reflect architectural differences.

5. Results and Discussion

5.1. Analysis of Fusion Experiments

To assess the effectiveness of different fusion strategies, we evaluate four commonly used methods on the HGPD dataset using YOLOv5n and YOLOv8n as baseline detectors. The methods include unimodal visible-only input (RGB), pixel-level data fusion (DF) [

22], decision-level fusion (DLF) [

40], and our proposed feature-level fusion strategy (FLF).

Results. Table 2 reports the detection performance (mAP

50), model size (Params), and computational complexity (FLOPs) of each fusion approach. Compared with the RGB-only baseline, all fusion-based methods show improved mAP

50 across both YOLO backbones. Among them, our FLF method achieves the highest detection accuracy on both YOLOv5n (95.0%) and YOLOv8n (95.3%).

Analysis. Compared to unimodal RGB, FLF improves mAP50 by 1.6% (YOLOv5n) and 1.1% (YOLOv8n), demonstrating the effectiveness of cross-modality integration. Notably, FLF also reduces parameters and FLOPs compared to other fusion strategies: 0.57 M fewer parameters and 1.4 G fewer FLOPs than DLF, showing better computational efficiency. Based on this trade-off between accuracy and cost, FLF is selected as the baseline method for subsequent experiments.

5.2. Ablation Study of the IVIFusion Model

To evaluate the contribution of each proposed module, we conduct ablation experiments on the HGPD dataset, as summarized in

Table 3. The experiments incrementally introduce three key components: the Cross-Modality Attention Fusion Module (CMAFM), the TFBackbone, and the Small Object Detection Layer (SODL). All variants share the same YOLOv8 dual-branch baseline structure.

Results. As shown in

Table 3, the baseline model achieves an mAP

50 of 95.2%. Replacing feature concatenation with CMAFM brings a slight improvement of 0.1%, and also reduces FLOPs. Introducing the TFBackbone enhances contextual modeling, boosting performance by 0.4%. The addition of the SODL yields a significant 1.7% gain, particularly for small-scale instances. The full IVIFusion model integrates all three modules and achieves 97.2% mAP

50, representing a 2.0% improvement over the baseline, with only minor increases in parameters and FLOPs.

Analysis. Each module contributes to complementary aspects: CMAFM improves cross-modal feature alignment, TFBackbone enhances semantic abstraction, and SODL focuses on fine-scale object localization. The combination of all components balances performance and efficiency, supporting deployment in lightweight scenarios.

5.3. Comparison with Mainstream Models

To thoroughly evaluate the advantages of multimodal pedestrian detection, we conduct comparisons with mainstream single- and multi-modal detection frameworks across two datasets with distinct characteristics: HGPD and LLVIP. Specifically, HGPD is used to verify the module-level effectiveness of IVIFusion in a controlled environment, while LLVIP offers a diverse and challenging benchmark for assessing generalization against state-of-the-art methods. To ensure a fair and consistent comparison on these public benchmarks, all performance numbers of the state-of-the-art methods reported in

Table 4 are directly taken from their original publications.

Evaluation on the HGPD Dataset. As shown in

Table 5, we compare IVIFusion with standard YOLO-based detectors under RGB-only, IR-only, and RGB+T inputs on the HGPD dataset. Among RGB-only models, YOLOv11 achieves 95.6% mAP

50, while infrared-only YOLOv8 and YOLOv5 reach 93.0% and 91.4%, respectively. IVIFusion surpasses all these with 97.2% mAP

50, achieving a 2.0% improvement over the dual-branch baseline (95.2%). These results confirm the value of the proposed fusion and backbone modules under controlled, high-quality data settings.

Evaluation on the LLVIP Dataset. To further demonstrate the generalization ability of IVIFusion in real-world low-light conditions, we compare it with prior state-of-the-art methods on the LLVIP dataset in

Table 4. IVIFusion achieves 98.6% mAP

50 and 70.2% mAP

50:95, outperforming the best RGB-only model (YOLOv11: 95.6%) and IR-only model (Faster R-CNN: 94.3%) by 3.0% and 4.3%, respectively. Compared with existing multimodal fusion models such as CSAA and DIVFusion, IVIFusion provides consistent gains while maintaining low computational cost (3.37M Params, 11.7 GFLOPs). These results verify that IVIFusion is both accurate and efficient under diverse illumination and cross-modal scenarios.

5.4. Result Visualization

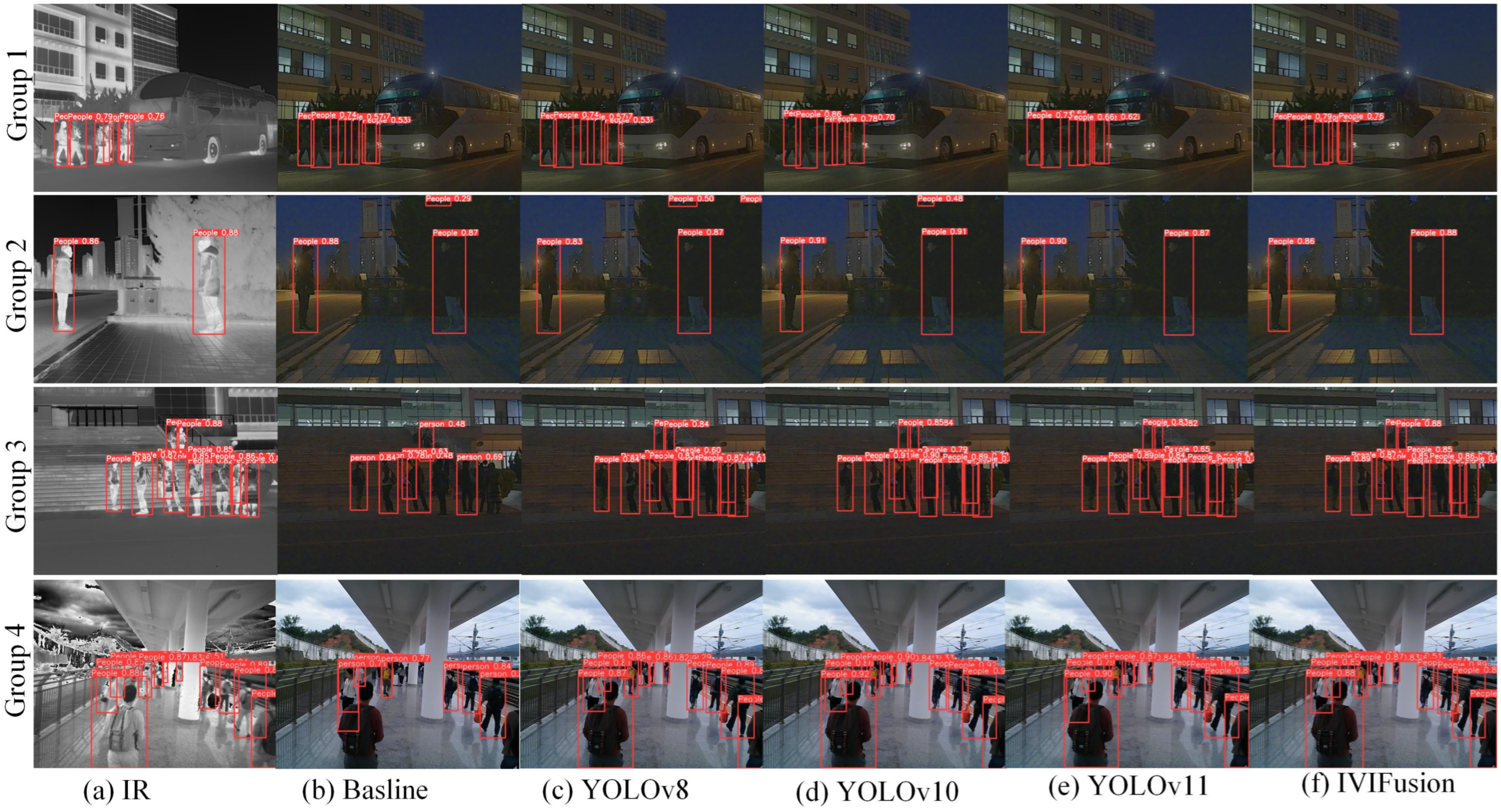

To better demonstrate the practical effectiveness of the proposed IVIFusion model, we present visual comparisons on both the HGPD and LLVIP datasets. Results are organized into two parts:

Detection Performance on the HGPD Dataset. Figure 7 showcases four representative nighttime scenarios from the HGPD dataset. Six different detection results are shown per scene: (a) infrared-only detection, (b) dual-branch baseline fusion, (c) YOLOv8, (d) YOLOv10, (e) YOLOv11 on RGB modality, and (f) the proposed IVIFusion. In group 2, models (b), (c), and (d) exhibit false positives, such as misclassifying tree branches as pedestrians. IVIFusion (f), in contrast, accurately filters out the noise. In group 4, which involves crowded pedestrian flow on a station platform, the baseline fusion model (b) misses several targets, potentially due to cross-modality misalignment. IVIFusion addresses this by accurately localizing the full pedestrian contours, demonstrating its robustness under challenging real-world conditions.

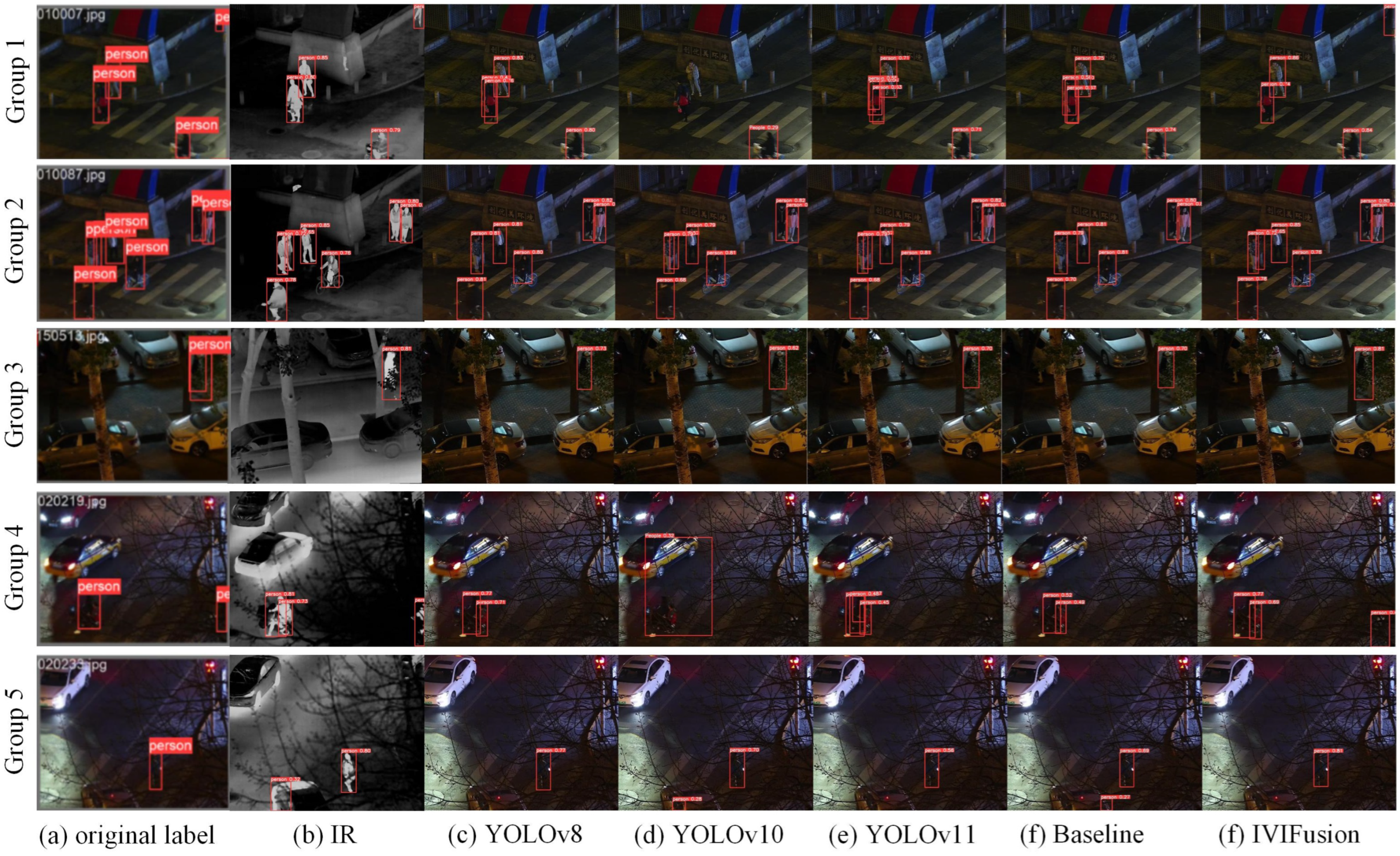

Detection Performance on the LLVIP Dataset. To further validate the generalization ability of IVIFusion, we conduct visual comparisons on the LLVIP dataset.

Figure 8 presents five nighttime scenes. The results include: (a) ground truth annotations, (b) IR-only detection, (c–e) RGB-only detection using YOLOv8–11, (f) dual-branch YOLOv8 fusion, and (g) the proposed IVIFusion.

In group 1, YOLOv8 fails to detect the pedestrian near the left edge, while in group 4, heavily occluded pedestrians are missed by most models. Group 5 reveals a false positive where the IR-only detector misidentifies a car tail as a pedestrian. These observations suggest that the visible modality is sensitive to lighting and background clutter, while the IR modality lacks sufficient texture cues. Fusion-based methods (e.g., f) partially alleviate these issues. However, Groups 3–5 also expose typical failure cases under severe occlusion: when pedestrians are largely blocked by trees, poles, or other foreground objects, even IVIFusion (g) may fail to detect all targets or produce incomplete bounding boxes. Overall, IVIFusion significantly reduces missed detections and false positives compared with the baselines and yields more spatially accurate and complete detections in most scenes, but robust handling of heavily occluded pedestrians remains an important direction for future improvement.

6. Conclusions

Pedestrian detection is essential in surveillance, autonomous driving, and human–computer interaction, especially under low-light and complex environmental conditions. This paper presents IVIFusion, a multimodal pedestrian detection framework that fuses infrared and visible inputs to overcome the limitations of single-modality detection.

We explored multiple fusion strategies and adopted feature-level fusion as the baseline due to its balance between accuracy and computational cost. To further improve fusion quality, an attention-based module is proposed to enhance cross-modal interaction while retaining modality-specific features. Additionally, a lightweight Transformer-based backbone is introduced to better capture global context. To address small-scale pedestrian instances, a fine-grained detection head is also integrated.

Experimental results on HGPD and LLVIP show that IVIFusion achieves state-of-the-art performance, with mAP50 scores of 97.2% and 98.6%, respectively. These results confirm its robustness across varying illumination and crowd densities. IVIFusion provides a compact and accurate solution for multimodal pedestrian detection, laying the groundwork for further applications in safety-critical and all-weather scenarios. Nevertheless, some limitations remain: as revealed by the visual results on LLVIP, IVIFusion may still miss pedestrians that are heavily occluded by trees, poles, or other foreground objects in complex nighttime scenes. In future work, we plan to investigate occlusion-aware fusion modules (e.g., incorporating depth or instance-level cues) and to exploit temporal information from consecutive RGB–IR frames, together with more diverse training data in heavily occluded scenarios, to further improve the robustness of multimodal pedestrian detection.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Jie Yang and Yanxuan Jiang; methodology, Jie Yang, Dengyin Jiang and Zhichao Chen; software, Yanxuan Jiang; validation, Jie Yang, Yanxuan Jiang and Zhichao Chen; formal analysis, Zhichao Chen; investigation, Yanxuan Jiang and Dengyin Jiang; resources, Jie Yang and Dengyin Jiang; data curation, Yanxuan Jiang and Dengyin Jiang; writing—original draft preparation, Jie Yang and Yanxuan Jiang; writing—review and editing, Jie Yang, Yanxuan Jiang, Dengyin Jiang and Zhichao Chen; visualization, Zhichao Chen; supervision, Jie Yang. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the National Key Research and Development Program of China under Grant 2024YFB4303201, and the Ganzhou City Key Research and Development Program under Grant GZ2024ZDZ007.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available on request.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported in part by the National Key R&D Program of China under Grant 2024YFB4303201, in part by the Ganzhou City Key Research and Development Program under Grant GZ2024ZDZ007.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

References

- Chen, Z.; Yang, J.; Li, F.; Feng, Z.; Chen, L.; Jia, L.; Li, P. Foreign Object Detection Method for Railway Catenary Based on a Scarce Image Generation Model and Lightweight Perception Architecture. In IEEE Transactions on Circuits and Systems for Video Technology; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Zeng, S.; Chang, X.; Xie, M.; Liu, X.; Bai, Y.; Pan, Z.; Xu, M.; Wei, X. FutureSightDrive: Thinking Visually with Spatio-Temporal CoT for Autonomous Driving. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2505.17685. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Z.; Yang, J.; Chen, L.; Li, F.; Feng, Z.; Jia, L.; Li, P. RailVoxelDet: A Lightweight 3-D Object Detection Method for Railway Transportation Driven by Onboard LiDAR Data. IEEE Internet Things J. 2025, 12, 37175–37189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Song, Y.; Yang, H.; Liu, Z. Generalized Koopman Neural Operator for Data-Driven Modeling of Electric Railway Pantograph–Catenary Systems. IEEE Trans. Transp. Electrif. 2025, 11, 14100–14112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, H.; Liu, Z.; Cui, H. An Electrified Railway Catenary Component Anomaly Detection Frame Based on Invariant Normal Region Prototype with Segment Anything Model. In IEEE Transactions on Transportation Electrification; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2025; pp. 1–12. [Google Scholar]

- Xue, C.; Zhong, B.; Liang, Q.; Xia, H.; Song, S. Unifying Motion and Appearance Cues for Visual Tracking via Shared Queries. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 35, 1987–1998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, C.; Zhong, B.; Liang, Q.; Zheng, Y.; Li, N.; Xue, Y.; Song, S. Similarity-guided layer-adaptive vision transformer for UAV tracking. In Proceedings of the Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition Conference, Gold Coast, Australia, 10–13 November 2025; pp. 6730–6740. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, G.; Yang, S.; Zheng, W.-S.; Li, Z.; Huang, Z. A Semantically Guided and Focused Network for Occluded Person Re-identification. IEEE Trans. Inf. Forensics Secur. 2025, 20, 9716–9731. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yang, J.; Feng, Z.; Zhu, H. RailFOD23: A dataset for foreign object detection on railroad transmission lines. Sci. Data 2024, 11, 72. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lu, K.; Zhang, L.; Li, S.; Huang, Y.; Ding, X.; Hao, J.; Huang, S.; Li, X.; Lu, F.; Zhang, H. Urban Rail Transit in China: Progress Report and Analysis (2015–2023). Urban Rail Transit 2025, 11, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- You, K.; Gu, Y.; Lin, Y.; Wang, Y. A novel physical constraint-guided quadratic neural networks for interpretable bearing fault diagnosis under zero-fault sample. Nondestruct. Test. Eval. 2025, 1–31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Lin, S.; Lu, X.; Cao, D.; Wu, H.; Guo, C.; Liu, C.; Wang, F.Y. Deep neural network based vehicle and pedestrian detection for autonomous driving: A survey. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2021, 22, 3234–3246. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, L.; Xiang, X.; Zhang, H.; Gong, M.; Ma, J. DIVFusion: Darkness-free infrared and visible image fusion. Inf. Fusion 2023, 91, 477–493. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Jin, G.; Shen, T.; Tan, L.; Wang, N.; Gao, J.; Yu, Y.; Tian, S. Target-Distractor Aware UAV Tracking via Global Agent. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 16116–16127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, Y.; Jin, G.; Zhong, B.; Shen, T.; Tan, L.; Xue, C.; Zheng, Y. FMTrack: Frequency-aware Interaction and Multi-Expert Fusion for RGB-T Tracking. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2025, 1–13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wei, R.; Zhu, D.; Zhan, W.; Hao, Z. Infrared and visible image fusion based on RPCA and NSST. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE International Conference on Power, Intelligent Computing and Systems (ICPICS), Shenyang, China, 12–14 July 2019; IEEE: Piscataway, NJ, USA, 2019; pp. 236–240. [Google Scholar]

- Mo, Y.; Kang, X.; Duan, P.; Sun, B.; Li, S. Attribute filter based infrared and visible image fusion. Inf. Fusion 2021, 75, 41–54. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Yang, J.; Chen, L.; Feng, Z.; Jia, L. Efficient railway track region segmentation algorithm based on lightweight neural network and cross-fusion decoder. Autom. Constr. 2023, 155, 105069. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Huang, H.; Zhang, L.; Chen, J.; Tong, Y.; Zhou, M. Towards automated 3D evaluation of water leakage on a tunnel face via improved GAN and self-attention DL model. Tunn. Undergr. Space Technol. 2023, 142, 105432. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, L.; Chen, Z.; Yan, L.; Cheng, Y.; Guan, F.; Li, P. Optimal distributed training with co-adaptive data parallelism in heterogeneous environments. In Proceedings of the Thirty-Fourth International Joint Conference on Artificial Intelligence, Montreal, QC, Canada, 16–22 August 2025; pp. 29–37. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, B.; Xia, J.; Wang, W. Ipfa-net: Important points feature aggregating net for point cloud classification and segmentation. Chin. J. Electron. 2025, 34, 322–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wagner, J.; Fischer, V.; Herman, M.; Behnke, S. Multispectral Pedestrian Detection using Deep Fusion Convolutional Neural Networks. ESANN 2016, 587, 509–514. [Google Scholar]

- Li, C.; Song, D.; Tong, R.; Tang, M. Illumination-aware faster R-CNN for robust multispectral pedestrian detection. Pattern Recognit. 2019, 85, 161–171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhai, S.; Dong, S.; Shang, D.; Wang, S. An improved faster R-CNN pedestrian detection algorithm based on feature fusion and context analysis. IEEE Access 2020, 8, 138117–138128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Bai, H.; Zhang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Xu, S.; Lin, Z.; Timofte, R.; Van Gool, L. Cddfuse: Correlation-driven dual-branch feature decomposition for multi-modality image fusion. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 5906–5916. [Google Scholar]

- Sun, J.; Yin, M.; Wang, Z.; Xie, T.; Bei, S. Multispectral object detection based on multilevel feature fusion and dual feature modulation. Electronics 2024, 13, 443. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Lou, W.; Feng, H.; Ding, N.; Li, C. MFMG-Net: Multispectral Feature Mutual Guidance Network for Visible–Infrared Object Detection. Drones 2024, 8, 112. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; He, H.; Zhang, Z.; Zhou, Y. LI-YOLO: An Object Detection Algorithm for UAV Aerial Images in Low-Illumination Scenes. Drones 2024, 8, 653. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, F.; Xu, D.; Ren, Z.; Shao, X.; Wu, Q.; Liu, Y.; Wang, J.; Song, J.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, G.; et al. Mamba-based super-resolution and semi-supervised YOLOv10 for freshwater mussel detection using acoustic video camera: A case study at Lake Izunuma, Japan. Ecol. Inform. 2025, 90, 103324. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, H.; Wang, S.; Duan, P.; Xiao, C.; Dian, R.; Li, S.; Li, Z. LRAF-Net: Long-Range Attention Fusion Network for Visible–Infrared Object Detection. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 35, 13232–13245. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kang, X.; Yin, H.; Duan, P. Global–Local Feature Fusion Network for Visible–Infrared Vehicle Detection. IEEE Geosci. Remote Sens. Lett. 2024, 21, 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khan, S.; Naseer, M.; Hayat, M.; Zamir, S.W.; Khan, F.S.; Shah, M. Transformers in vision: A survey. ACM Comput. Surv. (CSUR) 2022, 54, 1–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tang, W.; He, F.; Liu, Y.; Duan, Y.; Si, T. DATFuse: Infrared and visible image fusion via dual attention transformer. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2023, 33, 3159–3172. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Zhu, J.; Li, C.; Chen, X.; Yang, B. CGTF: Convolution-guided transformer for infrared and visible image fusion. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2022, 71, 1–14. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, J.; Wu, Y.; Wu, G.; Liu, R.; Fan, X. Learn to search a lightweight architecture for target-aware infrared and visible image fusion. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2022, 29, 1614–1618. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jocher, G.; Chaurasia, A.; Qiu, T.; Stoken, A. YOLOv5: You Only Look Once Version 5. 2020. Available online: https://github.com/ultralytics/yolov5 (accessed on 22 June 2024).

- Chen, Z.; Guo, H.; Yang, J.; Jiao, H.; Feng, Z.; Chen, L.; Gao, T. Fast vehicle detection algorithm in traffic scene based on improved SSD. Measurement 2022, 201, 111655. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lin, T.Y.; Goyal, P.; Girshick, R.; He, K.; Dollár, P. Focal loss for dense object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2980–2988. [Google Scholar]

- Jia, X.; Zhu, C.; Li, M.; Tang, W.; Zhou, W. LLVIP: A visible-infrared paired dataset for low-light vision. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Virtual, 11–17 October 2021; pp. 3496–3504. [Google Scholar]

- Hu, Z.; Jing, Y.; Wu, G. Decision-level fusion detection method of visible and infrared images under low light conditions. EURASIP J. Adv. Signal Process. 2023, 2023, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards real-time object detection with region proposal networks. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2016, 39, 1137–1149. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, H.; Jin, F.; Zeng, H.; Pu, H.; Fan, B. Image Enhancement Guided Object Detection in Visually Degraded Scenes. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2024, 35, 14164–14177. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhang, H.; Li, F.; Liu, S.; Zhang, L.; Su, H.; Zhu, J.; Ni, L.; Shum, H.Y. DINO: DETR with Improved DeNoising Anchor Boxes for End-to-End Object Detection. In Proceedings of the The Eleventh International Conference on Learning Representations, Kigali, Rwanda, 1–5 May 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Diwan, T.; Anirudh, G.; Tembhurne, J.V. Object detection using YOLO: Challenges, architectural successors, datasets and applications. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2023, 82, 9243–9275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medeiros, H.R.; Pena, F.A.G.; Aminbeidokhti, M.; Dubail, T.; Granger, E.; Pedersoli, M. HalluciDet: Hallucinating RGB Modality for Person Detection Through Privileged Information. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision, Waikoloa, HI, USA, 4–8 January 2024; pp. 1444–1453. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, Y.T.; Shi, J.; Ye, Z.; Mertz, C.; Ramanan, D.; Kong, S. Multimodal object detection via probabilistic ensembling. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision, Tel Aviv, Israel, 23–27 October 2022; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2022; pp. 139–158. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, W.; Xie, S.; Zhao, F.; He, Y.; Lu, H. Metafusion: Infrared and visible image fusion via meta-feature embedding from object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 13955–13965. [Google Scholar]

- Cao, Y.; Bin, J.; Hamari, J.; Blasch, E.; Liu, Z. Multimodal object detection by channel switching and spatial attention. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 403–411. [Google Scholar]

- Zhao, Z.; Bai, H.; Zhu, Y.; Zhang, J.; Xu, S.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, K.; Meng, D.; Timofte, R.; Van Gool, L. DDFM: Denoising diffusion model for multi-modality image fusion. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 2–6 October 2023; pp. 8082–8093. [Google Scholar]

- Tang, L.; Chen, Z.; Huang, J.; Ma, J. Camf: An interpretable infrared and visible image fusion network based on class activation mapping. IEEE Trans. Multimed. 2023, 26, 4776–4791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Figure 1.

Comparison between Infrared and Visible Images. Infrared images highlight thermal radiation and maintain target contrast in low-light scenes, while visible images provide richer texture details under adequate lighting.

Figure 1.

Comparison between Infrared and Visible Images. Infrared images highlight thermal radiation and maintain target contrast in low-light scenes, while visible images provide richer texture details under adequate lighting.

Figure 2.

Architecture of the IVIFusion Framework for Cross-Modality Pedestrian Detection. The framework consists of a dual-branch Transformer backbone for modality-specific feature extraction, a cross-modality attention fusion module (CMAFM) for adaptive feature integration, and multi-scale detection heads for handling pedestrians of different sizes.

Figure 2.

Architecture of the IVIFusion Framework for Cross-Modality Pedestrian Detection. The framework consists of a dual-branch Transformer backbone for modality-specific feature extraction, a cross-modality attention fusion module (CMAFM) for adaptive feature integration, and multi-scale detection heads for handling pedestrians of different sizes.

Figure 3.

TFBackbone Architecture. The backbone consists of multi-stage TFBlocks, Vision Clue Merge modules for resolution adjustment, and a final SPPF layer for context aggregation.

Figure 3.

TFBackbone Architecture. The backbone consists of multi-stage TFBlocks, Vision Clue Merge modules for resolution adjustment, and a final SPPF layer for context aggregation.

Figure 4.

Architecture of the Cross-Modality Attention Fusion Module. Given the concatenated visible and infrared features, the module splits them into multiple groups, each processed by two parallel attention branches. Channel-wise and spatial relationships are modulated via GAP and GroupNorm, followed by modality-guided fusion. This design enhances discriminative feature selection while suppressing modality-specific noise.

Figure 4.

Architecture of the Cross-Modality Attention Fusion Module. Given the concatenated visible and infrared features, the module splits them into multiple groups, each processed by two parallel attention branches. Channel-wise and spatial relationships are modulated via GAP and GroupNorm, followed by modality-guided fusion. This design enhances discriminative feature selection while suppressing modality-specific noise.

Figure 5.

Structure of the Small Object Detection Layer (SODL). A detection head is added at a resolution () to improve sensitivity to fine-grained features. This branch complements deeper outputs by incorporating early-layer cues, which helps in detecting small-scale pedestrian instances under challenging conditions.

Figure 5.

Structure of the Small Object Detection Layer (SODL). A detection head is added at a resolution () to improve sensitivity to fine-grained features. This branch complements deeper outputs by incorporating early-layer cues, which helps in detecting small-scale pedestrian instances under challenging conditions.

Figure 6.

Acquisition process of the HGPD dataset. An Orbbec Astra Pro sensor with RGB and IR cameras is mounted on the front of the monorail cabin and connected to a laptop for synchronized recording. Paired RGB–IR frames are sampled from the recorded videos and later annotated with pedestrian bounding boxes using shared labels for both modalities.

Figure 6.

Acquisition process of the HGPD dataset. An Orbbec Astra Pro sensor with RGB and IR cameras is mounted on the front of the monorail cabin and connected to a laptop for synchronized recording. Paired RGB–IR frames are sampled from the recorded videos and later annotated with pedestrian bounding boxes using shared labels for both modalities.

Figure 7.

Comparison of detection results from different models on the HGPD dataset. (a) IR-only, (b) Dual-branch fusion baseline, (c) YOLOv8-RGB, (d) YOLOv10-RGB, (e) YOLOv11-RGB, (f) Proposed IVIFusion.

Figure 7.

Comparison of detection results from different models on the HGPD dataset. (a) IR-only, (b) Dual-branch fusion baseline, (c) YOLOv8-RGB, (d) YOLOv10-RGB, (e) YOLOv11-RGB, (f) Proposed IVIFusion.

Figure 8.

Visual comparisons on the LLVIP dataset. (a) Ground Truth, (b) IR-only, (c) YOLOv8-RGB, (d) YOLOv10-RGB, (e) YOLOv11-RGB, (f) Proposed IVIFusion.

Figure 8.

Visual comparisons on the LLVIP dataset. (a) Ground Truth, (b) IR-only, (c) YOLOv8-RGB, (d) YOLOv10-RGB, (e) YOLOv11-RGB, (f) Proposed IVIFusion.

Table 1.

TFBackbone layer-wise configuration.

Table 1.

TFBackbone layer-wise configuration.

| Stage | Module | Output Size | Repeat | Channels |

|---|

| Input | - | | 1 | 3 |

| - | Conv | | 1 | 64 |

| - | Conv | | 1 | 64 |

| L1 | TFBlock | | 3 | 64 |

| - | Vision Clue Merge | | 1 | 128 |

| L2 | TFBlock | | 3 | 128 |

| - | Vision Clue Merge | | 1 | 256 |

| L3 | TFBlock | | 3 | 256 |

| - | Vision Clue Merge | | 1 | 512 |

| L4 | TFBlock | | 3 | 512 |

| - | SPPF | | 1 | 512 |

Table 2.

Comparison of fusion strategies on HGPD using YOLOv5n and YOLOv8n. P: Parameters (M), F: FLOPs (G). FLF is our feature-level fusion.

Table 2.

Comparison of fusion strategies on HGPD using YOLOv5n and YOLOv8n. P: Parameters (M), F: FLOPs (G). FLF is our feature-level fusion.

| Method | YOLOv5n | YOLOv8n |

|---|

| mAP50 | P/M | F/G | mAP50 | P/M | F/G |

|---|

| RGB | 93.4 | 2.51 | 7.2 | 94.2 | 3.01 | 8.2 |

| DF [22] | 94.8 | 3.58 | 12.2 | 95.2 | 3.01 | 9.0 |

| DLF [40] | 94.9 | 3.40 | 10.0 | 95.3 | 4.00 | 8.0 |

| FLF (Ours) | 95.0

| 2.03 | 5.8 | 95.3 | 2.44 | 6.8 |

Table 3.

Ablation results on the HGPD dataset. All models are based on the YOLOv8 dual-branch baseline. P: Parameters (M), F: FLOPs (G).

Table 3.

Ablation results on the HGPD dataset. All models are based on the YOLOv8 dual-branch baseline. P: Parameters (M), F: FLOPs (G).

| CMAFM | TF | SODL | mAP50 | P/M | F/G |

|---|

| – | – | – | 95.2 | 2.44 | 6.8 |

| ✓ | – | – | 95.3 | 2.44

| 3.4 |

| – | ✓ | – | 95.6 | 2.93 | 4.0 |

| – | – | ✓ | 96.9 | 3.37 | 11.0 |

| ✓ | ✓ | ✓ | 97.2 | 3.37 | 11.7 |

Table 4.

Performance comparison on the LLVIP dataset. P: Parameters (M), F: FLOPs (G). “–” indicates not reported. Baseline: two-branch YOLOv8n with feature-level fusion of RGB and IR features at the neck.

Table 4.

Performance comparison on the LLVIP dataset. P: Parameters (M), F: FLOPs (G). “–” indicates not reported. Baseline: two-branch YOLOv8n with feature-level fusion of RGB and IR features at the neck.

| Model | Modal | mAP50 (%) | mAP50:95 (%) | P/M | F/G |

|---|

| Faster R-CNN [41] | RGB | 90.1 | 49.2 | – | – |

| IEGOD [42] | RGB | 87.6 | – | – | – |

| DINO [43] | RGB | 90.5 | 52.3 | – | – |

| YOLOv8 [44] | RGB | 94.3 | 58.9 | 11.2 | 28.8 |

| YOLOv10 [44] | RGB | 95.3 | 58.1 | 8.07 | 24.8 |

| YOLOv11 [44] | RGB | 95.6 | 59.8 | 9.43 | 21.5 |

| Faster R-CNN [41] | IR | 94.3 | 58.3 | – | – |

| HalluciDet [45] | IR | 90.1 | 57.8 | – | – |

| DINO [43] | IR | 90.2 | 51.3 | – | – |

| Baseline | RGB + T | 98.1 | 70.1 | 2.44 | 6.8 |

| ProEn [46] | RGB + T | 93.4 | 51.5 | – | – |

| DIVFusion [13] | RGB + T | 89.8 | 52.0 | 4.40 | 14,454.9 |

| Metafusion [47] | RGB + T | 91.0 | 56.9 | – | – |

| CSAA [48] | RGB + T | 94.3 | 59.2 | – | – |

| DDFM [49] | RGB + T | 91.5 | 58.0 | – | – |

| CAMF [50] | RGB + T | 89.0 | 55.6 | – | – |

| IVIFusion | RGB+T | 98.6 | 70.2 | 3.37 | 11.7 |

Table 5.

Performance comparison on the HGPD dataset. P: Parameters (M), F: FLOPs (G). Baseline: two-branch YOLOv8n with feature-level fusion of RGB and IR features at the neck.

Table 5.

Performance comparison on the HGPD dataset. P: Parameters (M), F: FLOPs (G). Baseline: two-branch YOLOv8n with feature-level fusion of RGB and IR features at the neck.

| Model | Modal | Backbone | mAP50 | P/M | F/G |

|---|

| YOLOv8 | RGB | CSDark53 | 94.2 | 11.2 | 28.8 |

| YOLOv10 | RGB | CSDark53 | 95.3 | 8.07 | 24.8 |

| YOLOv11 | RGB | CSDark53 | 95.6 | 9.43 | 21.5 |

| YOLOv5 | IR | CSDark53 | 91.4 | 2.50 | 7.8 |

| YOLOv8 | IR | CSDark53 | 93.0 | 3.01 | 8.2 |

| Baseline | RGB + T | Dual CSDark | 95.2 | 2.44 | 6.8 |

| IVIFusion | RGB + T | TFBackbone | 97.2 | 3.37 | 11.7 |

| Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).