Abstract

The quality of scanned topographic maps—including parameters such as image compression, scanning resolution, and bit depth—may strongly influence the performance of deep learning models for contour vectorization. In this study, we investigate this dependence by training eight U-Net models on the same map data but under varying input quality conditions. Each model is trained to segment contour lines from the raster input, followed by a postprocessing pipeline that converts segmented output into vector contours. We systematically compare the models with respect to topological error metrics (such as contour intersections and dangling ends) in the resulting vector output and overlay metrics of matched contour segments within given tolerance. Our experiments demonstrate that while the input data quality indeed matters, moderate lowering of quality parameters doesn’t introduce significant practical tradeoff, while storage and computational requirements remain low. We discuss implications for the preparation of archival map scans and propose guidelines for choosing scanning settings when the downstream goal is automated vectorization. Our results highlight that deep learning methods, though resilient against reasonable compression, remain measurably sensitive to degradation in input fidelity.

1. Introduction

Historical maps represent a rich source of spatial information about past terrain morphology, land cover, culture, and infrastructure. Their altimetric content—often encoded by annotated elevation contours—supports three major research domains. First, environmental reconstruction and geomorphological analyses use contour-derived DEMs to investigate past terrain morphology and hydrological regimes. Second, archaeological and historical-landscape studies rely on preserved contour detail to identify buried or degraded landforms, reconstruct defensive features, or analyze settlement evolution [1,2]. Third, land-use and landscape-change research frequently employs elevation data from historical maps to model terrain modifications caused by mining, forestry, urbanization [3], or dam construction [4,5]. To be usable in modern GIS workflows, such information often must be converted from raster scans into vector form via a process known as contour vectorization. Across these domains, numerous studies have demonstrated the value of accurate elevation extraction from historical cartographic sources; however, they rarely examine the upstream factors affecting extraction quality.

Traditional vectorization methods—manual tracing, threshold-based segmentation of RGB/HSV values [6,7,8,9], or semi-automatic tools [10]—are time-consuming, tedious, and often require significant manual correction, especially when maps exhibit noise, variable symbology, annotations interfering with contour lines, and inconsistency across map sheets. Variations in color introduced by scanning also account for disrupting connectivity of homogeneous map elements, resulting in topological breaks requiring manual repair [11,12,13]. This results in fragmented polylines with high rates of broken connectivity. Deep learning approaches [14], such as convolutional neural networks (CNNs) [15,16] in semantic segmentation setups, offer promise for automating much of this workflow, as demonstrated by various case studies [17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25]. In recent work [26] we successfully applied a U-Net [27] model with subsequent postprocessing to vectorize elevation contours from scanned topographic maps (specifically the SMO-5 “State Map 1:5000-Derived” series). That method improved robustness against noise, reduced topological errors, and lowered the manual workload compared to older thresholding-based and semi-automatic techniques.

However, an often-underappreciated factor in any automatic processing of raster data is the quality of the input raster scans—parameters such as scanning resolution (dots per inch—DPI), bit-depth (e.g., 8-bit vs. 16-bit), compression level (lossy vs. lossless), and related image artifacts. In the previous case study [26], variation in map symbology and scanning practices between sheets introduced spectral and figurative diversity which harmed performance in some cases. While training on a diverse dataset with augmentation and loss functions sensitive to topology mitigated some of these issues, the experiments did not explicitly measure how different input quality parameters (compression, DPI, bit depth) affect model performance or error-types in vectorization. It is reasonable to expect that output quality degrades with input quality, but this notion is use-case dependent, and a comprehensive investigation for automatic vectorization of scanned maps is currently missing.

In this paper, we close that gap. We systematically vary input quality along key dimensions (e.g., downscaling, compression, bit depth) and train the U-Net network on each variant. By comparing the resulting vectorizations (via topological error metrics, omission & commission errors, etc.), we aim to quantify how much input quality matters—and where diminishing returns occur. Higher scan quality presents higher requirements for storage capacity and processing power. Finding a reasonable compromise between quality and these demands is also our objective.

2. Related Research

Various digitization guidelines recommend minimum scanning resolutions (commonly 400 DPI) and bit depths (8-bit or higher per channel) for archival historic maps. For example, the USGS Specification for the Historical Topographic Map Collection requires scans of at least 400 DPI and 8-bit per channel in uncompressed formats [28]. Librarian/archival digitization—e.g., University of Virginia [29] and USGS [30] hardware specifications—similarly emphasize bit depth, color fidelity, and minimal compression to preserve fine cartographic detail. Talich [31] strongly recommends scanning in at least 400 DPI quality, recommending 600 DPI for most use cases, specifically in relation to object detection of points of interest.

Regarding the impact of raster data quality on further automated processing, numerous studies have been published. In the field of geomatics, Kostrzewa et al. explored the effects of quality on scanned historical aerial images for photogrammetric processing [32], comparing professional and consumer-grade scanners’ performance, concluding notable, but not critical differences. Liao et al. investigated the effect of bit depth on cloud segmentation of remote-sensing images [33]. Also using U-Net, they came to a similar conclusion, showing moderate improvement with 16-bit data. Hu et al. [34] conducted experiments with UAV footage of weed and simulating degradation techniques such as downscaling, gaussian and motion blurs and noise, to estimate influence on object detection and instance segmentation, also concluding the necessity to train on degraded images to achieve somewhat competitive results.

In a broader computer vision field, Poyser et al. experimented with JPEG compression and various CNNs [35] to find strong robustness even with heavy compression, which can be improved further with retraining on compressed data. Also, encoder-decoder networks (such as U-Net) reportedly demonstrate better resilience to lossy compression. In radiography, experiments have been conducted with compressed mammograms [36], concluding that for this purpose, moderate compression does not impact classification performance.

Meanwhile, in research applying deep learning to map vectorization or segmentation, artifacts introduced by noise, color variation, scan inconsistency etc. are repeatedly noted as impediments: work on deep edge filtering and shape extraction [24,37] shows degraded performance under noisy or low-quality scans. Thus, although previous studies and benchmarks recognize variation in map scan quality, there is a lack of systematic experimental quantification of how different input scan parameters (compression, DPI, bit depth) map onto specific error types (e.g., omission, commission, topological breaks) in contour vectorization.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Dataset and Area

The site of interest is the upper course of the Vltava River historical valley around the current Lipno dam, located in Czech Republic, Europe (Figure 1). The dam was built in the 1950s resulting in a large landscape change. The area was documented before and after this change on numerous maps.

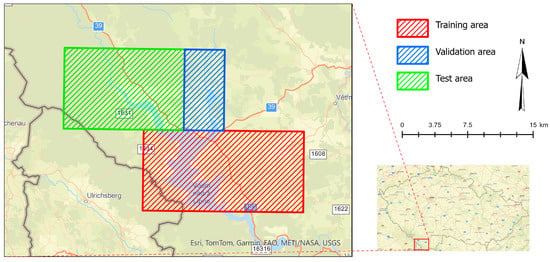

Figure 1.

Map with the locality of interest—upper course of Vltava valley centered around the Lipno dam.

The map series used in this study are TM10 and TM25, i.e., Topographic Maps of scale 1:10,000 and 1:25,000, covering identical area. A TM25 sheet consists of four TM10 sheets. TM10 maps were created in the years 1957–1971 with base elevation interval of two (sometimes five) meters. The symbology consists of seven colors and overall, 6432 map sheets were created for the area of former Czechoslovakia. TM25 maps are older, dating to 1953–1957 period, with five-meter base elevation interval and 1736 map sheets total. Given that the TM25 map sheets covering area of interest were drawn in 1954, the dam is not present yet, whereas TM10 map sheets come from the sixties with the dam already depicted. Both of these map series were created mostly with aerial photogrammetry, and both are in S-52 coordinate system used by the Warsaw pact armies.

We train one neural network per combined dataset with identical splits as depicted in Figure 1. The split is described in detail in Table 1. Train set is used for training with Validation set used for monitoring, loss computation and plateau scheduling. Finally, we evaluate the performance on the independent Test set.

Table 1.

Sites of interest used for training and testing the model.

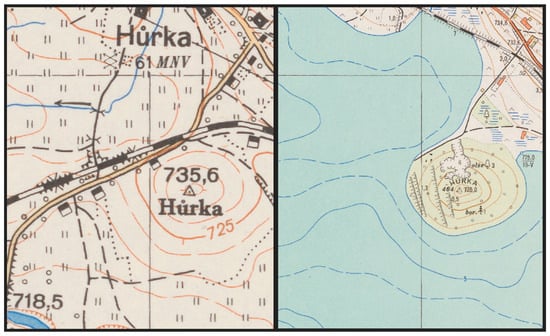

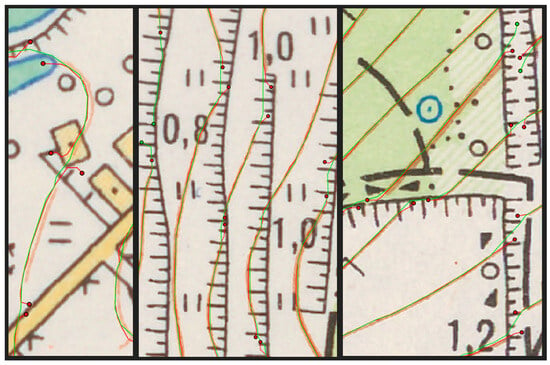

Some map sheets exhibit slight symbological differences, notably differing contour elevation intervals, resulting in discontinuities on map seams. Some map sheets were created in different years by different workers, and this also influences the final symbology diversity, although not to the extent of SMO-5 maps, which were of interest in our previous paper [26]. Other difficulties were experienced during annotation, such as black slope signs interrupting contours in TM10 maps (depicted in Figure 2 right). The contours are frequently interrupted by other layers of symbology or elevation annotations, which makes any automated vectorization difficult.

Figure 2.

Excerpts from TM25 (left) and TM10 (right) maps, depicting an identical area before and after flooding. As evident, the depth contours in the newer map were copied from the original TM25 map. The remainder of the contours is however changed.

3.2. Data Quality and Pre-Processing

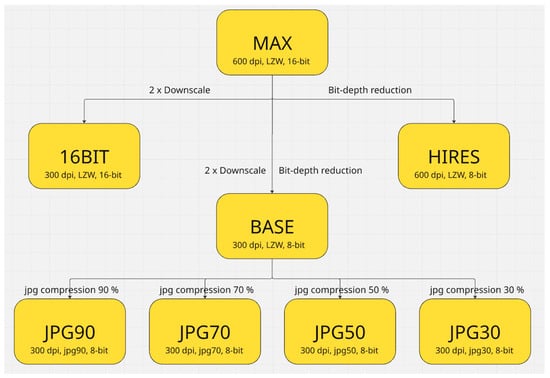

To evaluate the effect of input data quality, we create multiple versions of the dataset, altered in different ways. The original map sheets were scanned in 600 DPI, 16-bit color palette and lossless compression, representing the highest available quality, with one map sheet taking around 500 MB of space. The resolution translates to ground sampling distance (GSD) of about 0.427 m for TM10 maps and 1.068 m for TM25. The original map sheets were projected onto the geographic grid and mosaicked together. Thus, the MAX dataset was created. To emulate data scanned in inferior manner, other datasets were derived by reducing the quality of the MAX in one or more aspects. HIRES dataset was created by reducing the radiometric depth to standard 8-bit color channels, 16BIT dataset was downscaled from 600 to 300 DPI. BASE dataset combines both of these reductions. Finally, JPG90, JPG70, JPG50 and JPG30 datasets are in addition compressed with 90%, 70%, 50% and 30% jpeg compression, respectively. Overall, eight datasets were created: MAX, HIRES, BASE, 16BIT, JPG90, JPG70, JPG50 and JPG30; they are depicted in Figure 3. All datasets were exported according to the data splits proposed in Figure 1 and Table 1. In total, summary of all raster data and their quality variants amounted to 13.6 GB.

Figure 3.

Chart of datasets. Overview of datasets with progressively reduced input quality parameters (bit depth, resolution, and JPEG compression). The original dataset with maximum quality is at the top, while the most compressed datasets are at the bottom.

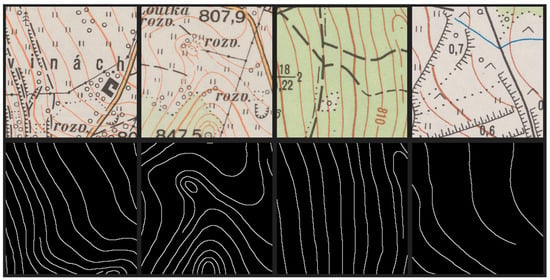

To create the ground truth binary mask, the manually created vector dataset was converted to raster. In case of 300 DPI data, the thickness of a contour is set to just one pixel to avoid merging in densely drawn areas. This implies spatially thicker contours in TM25 map series with larger GSD, but the contours are also drawn thicker. With 600 DPI data, the contour segments are created two pixels wide to even out further comparisons. The input raster data were partitioned into image chips, with a padding half the size, resulting in 17,170 training chips and 4414 validation chips. Because variances in receptive field size can lead to differing results [38], MAX and HIRES chips are of size 512 × 512 pixels, whereas the downscaled datasets consist of chips of 256 × 256 pixel size, to retain consistent across tested datasets. This results in spatially identical training datasets. Visualization of some of the training chips from BASE dataset along with their ground truth masks is shown in Figure 4.

Figure 4.

Examples of image chips from the BASE dataset used for training (before contrast/geometric augmentation). First two pairs come from TM25 data, latter two pairs represent TM10 data.

3.3. Training Experiments

As in our previous paper [26], all the experiments were conducted with a batch size of 4, a base learning rate of 1 × 10−4 with gradual reduction using a plateau learning-rate scheduler to 1 × 10−5, and a weight decay of 2 × 10−4. Because of the background class prevailing over the contour class, classes are significantly imbalanced. This is handled in the weighted computation of the loss function. The loss function is set to binary cross-entropy, as the task is posed as a simple two-class segmentation. For spectral augmentation, contrast stretching is used with random values between 0.8 and 1.25 and for geometric augmentation, randomized affine transformation was used.

We trained each model for 100 epochs. The model is then used for inference on the test split. The training was performed on an Nvidia GeForce 4070 Ti. One epoch took about twelve minutes for downscaled datasets and thirty-five minutes for original sizes with larger chip size to retain the receptive field. Due to limited resources, we could not conduct more extensive testing; therefore, we limited the number of experiments to eight, those depicted in Figure 3.

3.4. Conversion to Vector and Evaluation

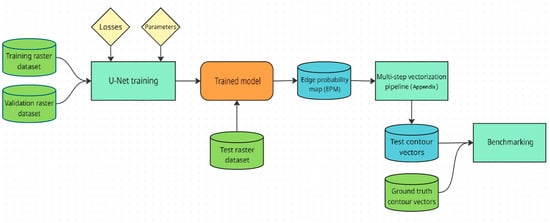

The overall process of vectorization and comparison of the various dataset version is depicted in Figure 5. The final trained checkpoint is inferred on the test split belonging to the particular version of the dataset. For each particular datasets, inference follows the size of receptive field set in the training, 256 pixels for 300 DPI data, 512 pixels for 600 DPI data. The result is an edge probability map (EPM) of the area. To process the EPM raster into vector, we make use of the recently proposed multi-step vectorization pipeline, in detail described along with minor changes in Appendix A. Finally, the resulting vectors are compared to the ground truth vectors in benchmarking, allowing us to compare the results based on the quality of input data.

Figure 5.

A flowchart showing the overall process of training, vectorization, and benchmarking. Input data are marked green. The individual steps are described further.

Evaluation takes place after vectorization, where we compare positional accuracy and topological correctness of the resulting vector contour map. Given differing spatial and spectral resolutions we can expect differences in omission/commission errors. To quantify topology, we use previously defined methodology: counting intersections and dangling ends, while deducting dangling ends occurring also in the ground truth vector. Errors located near outer borders of the raster are also disregarded. Resulting counts give a general idea about topological consistency and amount of work necessary for manual correction.

To quantify positional and omission/commission errors, we create buffer zones around predicted and ground truth network using buffer size for overlay analyses two and four pixels wide for 300 and 600 DPI data respectively, translating to 1.708 m for TM10 data and 4.272 m for TM25 data. We then calculate intersection lengths to determine how much of one predicted contour line layer is “matched” by the ground truth line layer and vice versa. Division of matched/total line parts yields precision:

i.e., what fraction of predicted contours is correct, and recall:

i.e., what fraction of ground truth contours is detected. Precision reflects the fraction of predicted contour length matching the reference, while recall measures the proportion of reference contours successfully captured. These metrics jointly indicate the trade-off between completeness and correctness of the vectorization. They are combined into F1 score for overall assessment, which is known as:

This metric quantifies share of false positives/negatives and can reveal overly coarse segmentations, where predicted contour lines diverge exceedingly from the ground truth.

4. Results

As presented earlier, eight neural networks were trained on training split and monitored on validation split, both consisting of combination of TM10 and TM25 chips (one network for both maps). After vectorization, overlay and topology analyses were conducted for both map series separately and the results are in Table 2. This comparison uses 2px and 4px buffers for low- and high-resolution data, respectively. For further comparison with smaller and larger thresholds, refer to Appendix B.

Table 2.

Table of results along with sizes of each test dataset. Eight neural networks were trained and inferred on their respective test split of both TM10 and TM25 data. The best result for given map series is highlighted in bold.

The best results on TM10 data are clearly achieved with MAX and HIRES dataset settings, as they excel in all overlay metrics, achieving nearly identical score. F1 score and other metrics drop significantly with downscaled resolution. In addition, the MAX dataset exhibits the fewest intersections. Intersections occur less frequently in 600 DPI data, but conversely, dangle ends errors are noticeably more frequent than in low-resolution datasets.

On TM25 data, the results are more even. The best performing datasets are again MAX and HIRES, but the margin is quite thin, and all the results are quite comparable.

Comparison of HIRES/MAX and BASE/16BIT datasets reveals the effect of 16-bit depth to be negligible. While segmentation of more abstract and less separable features can benefit from higher bit depth, such is the case in remote sensing use-cases, the improvement is not measurable in our context. On the other hand, increase in spatial resolution is definitely visible, helping to achieve noticeable gain in overlay metrics. However, the dataset size grows four times for twice the resolution, and requirements for processing power and time grow in a similar manner, which presents a trade-off situation. The effect of JPEG compression is of particular interest, because for this use-case, even for the highest level of compression, U-Net is still able to perform quite well. While the metrics obviously slightly degrade, as [35] pointed out, the large drop only happens below 15% compression.

5. Discussion

We train and evaluate both TM10 and TM25 maps at the same time. While the distribution of contour and background classes were normalized, distribution of TM10 and TM25 was left intact. Given that TM10 dataset is overrepresented in training by the approximate factor of six, the trained network is systematically skewed to perform better with TM10 data. While both map series are quite similar in symbology and scale relative to the pixel, TM25 metrics don’t necessarily follow the quality trend and aren’t statistically as important as TM10 test data. This would explain the somewhat inconclusive results on TM25 data, whereas TM10 overlay metrics follow expectations, decreasing with input data quality.

Dangling end errors increase in high-resolution datasets by a factor of nearly 50%, this is supported by results on both map series. These errors generally happen when contours are interrupted with other symbology elements or elevation annotations, whereas low-resolution datasets are mostly able to overcome these barriers, as shown in Figure 6. Even though the image chip size was enlarged for high-resolution data to match the receptive field across all datasets, the sharper disconnections in difficult situations remain. Given the nature of contours, a smaller receptive field can be sufficient to capture enough spatial context for successful segmentation, while avoiding this over-segmentation. Another option would be to lower the EPM threshold.

Figure 6.

Dangling errors in TM10 maps visualized. Red contours and points come from HIRES dataset and green elements represent BASE dataset. These disconnections are already evident in EPM raster data. In these specific situations, the low-resolution datasets clearly perform better.

Processing 600 DPI tiles increased GPU memory usage by 2.4× and training time per epoch by roughly threefold compared to 300 DPI tiles, while improving F1 by only ~4%. This quantifies the diminishing returns at higher scan resolutions.

Tolerance setting for overlay analysis, here proposed as two pixels of the downscaled dataset, can be altered based on demanded accuracy of the final vector. The overlay metric reflects both cases, where contours are completely omitted/falsely places, and where they are roughly correct, but exceed the distance from ground truth. If the requirement is just to avoid false positives/negatives and the emphasis is not on spatial accuracy, the tolerance threshold can be relaxed. Either way, our setting allowed us to sufficiently differentiate the trained models apart.

The experiments were limited to one map region and two related series (TM10, TM25). While these share symbology and scanning consistency, results may differ for maps with heavier annotation or discoloration. Future work should test broader styles and potentially employ super-resolution or denoising networks as preprocessing.

The only network tested was U-Net. Other networks (ResNet, DenseNet, HED etc.) may perform differently under varying input quality conditions. Given that previous research suggests U-Net to perform the best [24,39], we limited the experiments to U-Net. A general comparison of various convolutional networks for semantic segmentation can be found in [40,41,42], with U-Net generally outperforming the other networks.

These findings can inform institutional digitization standards (e.g., USGS, national archives) by providing quantitative evidence of where increased scan fidelity ceases to yield practical gains for automated analysis.

6. Conclusions

To our knowledge, no prior study has experimentally evaluated how scan resolution, bit depth, and compression jointly influence deep-learning-based contour vectorization. While related works acknowledge scan variability as a challenge, none have systematically quantified its effects on topological and geometric accuracy. By training and evaluating eight U-Net models under different combinations of resolution, bit depth, and compression, we quantified both the visual and topological impacts of input image degradation on contour extraction accuracy.

Our results show that while high-resolution data (600 DPI) consistently yield the best precision and recall, moderate reductions in scanning parameters—such as halving the resolution to 300 DPI or applying light JPEG compression—introduce only marginal degradation in vector accuracy. The 16-bit radiometric depth offers no measurable benefit for this type of cartographic input, where information is primarily carried in discrete color contrasts. The most significant trade-off occurs with heavy downscaling or compression, which leads to loss of continuity and increased topological defects, especially in dense contour regions.

Interestingly, high-resolution datasets also produced more dangling-end errors, indicating that finer spatial detail can amplify local discontinuities when other map symbology interferes with contour lines. This suggests that overly sharp input may sometimes hinder smooth segmentation unless combined with topology-aware loss functions or contextual post-processing.

From a practical standpoint, our experiments highlight a reasonable balance between accuracy, storage, and processing cost. Scanning at 300–400 DPI with 8-bit depth and lossless or lightly compressed formats is sufficient for reliable deep-learning-based contour vectorization, while higher settings mainly increase data volume and computation time without proportional accuracy gains.

Future research could expand this work toward other map series, different network architectures, and noise-reduction or restoration techniques to further mitigate the influence of sub-optimal scans. The presented results provide quantitative support for digitization guidelines and can help archives and GIS practitioners choose appropriate scanning parameters when preparing historical maps for automated analysis.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Jakub Vynikal and Jan Pacina; methodology, Jakub Vynikal; software, Jakub Vynikal; validation, Jakub Vynikal; formal analysis, Jakub Vynikal; investigation, Jakub Vynikal; resources, Jakub Vynikal; data curation, Jakub Vynikal; writing—original draft preparation, Jakub Vynikal; writing—review and editing, Jan Pacina; visualization, Jakub Vynikal; supervision, Jan Pacina. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Grant Agency of Czech Technical University in Prague, grant SGS25/046/OHK1/1T/11 (JV).

Data Availability Statement

The authors do not have permission to share data as they are subject to copyright by the Czech State Administration of Land Surveying and Cadastre.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A

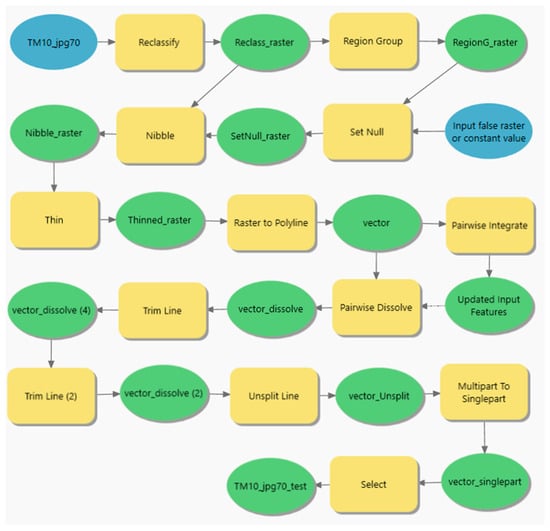

The multi-step vectorization pipeline was developed in our previous paper [26] to efficiently convert EPMs to vectors while minimizing topological errors and is displayed in Figure A1. The reader is directed to the original paper, as we only briefly describe the pipeline and the minor changes we made in this paper.

Figure A1.

Pipeline from EPM raster to vectorized contours as conceived in ArcGIS 3.3 ModelBuilder. “Reclassify” step represents thresholding, the binary raster is then grouped by connected regions, and regions smaller than 400 are dissolved into the surrounding value. The raster is then thinned and converted to a polyline (with simplification). Vertices in mutual proximity are integrated; the dangling lines are trimmed (twice) and connected line elements are merged into one (unsplit). Finally, small segments are discarded.

The EPM is first thresholded at 0.5 probability, then region grouped into individual clusters and clusters smaller than 400 (1600 in high-resolution datasets) pixels are removed. The remaining clusters are thinned and batch converted to polylines with vertex simplification. The closely placed vertices (closer than GSD) are integrated together to prevent circular topological errors. The dangling lines are trimmed two times, and the rest are converted to single-part contours.

The only major change is that in the end, lines smaller than a threshold (50 m in TM10, 125 m in TM25) are deleted. This mainly clears out messily vectorized areas with stacked contours that would have to be manually vectorized from scratch anyway. The only other change is adaptation of parameters to variances in resolution/map scale.

Appendix B

In Table A1 and Table A2 we provide overlay statistics with variable buffer threshold. The original threshold is 2px for low-resolution raster and 4px for high-resolution raster. In following table there are results for 1px/2px and 3px/6px respectively. Number of intersections remains the same as in original analysis, while dangle ends differ because of different tolerance settings. As evident, 3px/6px threshold is too large, blurring the differences between datasets. However, 1px/2px threshold confirms previous findings and actually makes them even more distinct: higher spatial resolution increases all metrics across all datasets, with MAX and HIRES datasets being clearly superior. Increase in spectral resolution does not translate to the results.

Table A1.

Table of results for 1px/2px threshold. The increased performance of high-resolution datasets is even more pronounced here than in the original comparison.

Table A1.

Table of results for 1px/2px threshold. The increased performance of high-resolution datasets is even more pronounced here than in the original comparison.

| Dataset | Size [MB] | Intersections | Dangle Ends | Precision | Recall | F1 Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TM10 | MAX | 1690.0 | 78 | 5378 | 0.6426 | 0.6410 | 0.6418 |

| HIRES | 1207.4 | 93 | 5589 | 0.6451 | 0.6413 | 0.6432 | |

| 16BIT | 442.5 | 122 | 3500 | 0.5523 | 0.5556 | 0.5539 | |

| BASE | 325.0 | 123 | 3683 | 0.5355 | 0.5409 | 0.5382 | |

| JPG90 | 123.3 | 121 | 3628 | 0.5562 | 0.5581 | 0.5571 | |

| JPG70 | 64.6 | 101 | 3581 | 0.5030 | 0.5046 | 0.5038 | |

| JPG50 | 46.1 | 132 | 3698 | 0.5346 | 0.5388 | 0.5367 | |

| JPG30 | 33.1 | 122 | 3456 | 0.5097 | 0.5112 | 0.5104 | |

| TM25 | MAX | 317.8 | 85 | 2237 | 0.7823 | 0.7562 | 0.7690 |

| HIRES | 231.9 | 109 | 2252 | 0.7799 | 0.7546 | 0.7670 | |

| 16BIT | 82.8 | 110 | 1499 | 0.7202 | 0.7086 | 0.7143 | |

| BASE | 61.8 | 100 | 1530 | 0.7140 | 0.6996 | 0.7067 | |

| JPG90 | 27.5 | 99 | 1724 | 0.7146 | 0.6980 | 0.7062 | |

| JPG70 | 15.6 | 112 | 1719 | 0.7043 | 0.6897 | 0.6969 | |

| JPG50 | 11.6 | 107 | 1623 | 0.7151 | 0.6988 | 0.7068 | |

| JPG30 | 8.5 | 94 | 1710 | 0.7156 | 0.6985 | 0.7069 |

Table A2.

Table of results for 3px/6px threshold. The results are now quite similar and thus inconclusive due to the threshold being too high.

Table A2.

Table of results for 3px/6px threshold. The results are now quite similar and thus inconclusive due to the threshold being too high.

| Dataset | Size [MB] | Intersections | Dangle Ends | Precision | Recall | F1 Score | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| TM10 | MAX | 1690.0 | 78 | 4960 | 0.9798 | 0.9755 | 0.9776 |

| HIRES | 1207.4 | 93 | 5189 | 0.9821 | 0.9746 | 0.9783 | |

| 16BIT | 442.5 | 122 | 3230 | 0.9702 | 0.9750 | 0.9726 | |

| BASE | 325.0 | 123 | 3383 | 0.9657 | 0.9744 | 0.9700 | |

| JPG90 | 123.3 | 121 | 3289 | 0.9707 | 0.9729 | 0.9718 | |

| JPG70 | 64.6 | 101 | 3276 | 0.9622 | 0.9638 | 0.9630 | |

| JPG50 | 46.1 | 132 | 3406 | 0.9637 | 0.9701 | 0.9669 | |

| JPG30 | 33.1 | 122 | 3196 | 0.9600 | 0.9617 | 0.9608 | |

| TM25 | MAX | 317.8 | 85 | 2126 | 0.9905 | 0.9574 | 0.9737 |

| HIRES | 231.9 | 109 | 2145 | 0.9897 | 0.9572 | 0.9732 | |

| 16BIT | 82.8 | 110 | 1424 | 0.9888 | 0.9725 | 0.9806 | |

| BASE | 61.8 | 100 | 1440 | 0.9889 | 0.9682 | 0.9784 | |

| JPG90 | 27.5 | 99 | 1639 | 0.9903 | 0.9667 | 0.9784 | |

| JPG70 | 15.6 | 112 | 1626 | 0.9886 | 0.9673 | 0.9778 | |

| JPG50 | 11.6 | 107 | 1523 | 0.9886 | 0.9656 | 0.9770 | |

| JPG30 | 8.5 | 94 | 1617 | 0.9884 | 0.9641 | 0.9761 |

References

- Kratochvilova, D.; Cajthaml, J. Using old maps to analyse land use/cover change in Water Reservoir Area. Abstr. ICA 2021, 3, 161. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vuorela, N.; Alho, P.; Kalliola, R. Systematic assessment of maps as source information in Landscape-Change Research. Landsc. Res. 2002, 27, 141–166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacina, J.; Novák, K.; Popelka, J. Georelief transfiguration in areas affected by open-cast mining. Trans. GIS 2012, 16, 663–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pacina, J.; Cajthaml, J.; Kratochvílová, D.; Popelka, J.; Dvořák, V.; Janata, T. Pre-Dam Valley Reconstruction based on archival spatial data sources: Methods, accuracy, and 3D printing possibilities. Trans. GIS 2021, 26, 385–420. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janovský, M. Pre-dam vltava river valley—A case study of 3D visualization of large-scale GIS datasets in Unreal Engine. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2024, 13, 344. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kratochvílová, D.; Cajthaml, J. Using the automatic vectorisation method in generating the vector altimetry of the historical Vltava River Valley. Acta Polytech. 2020, 60, 303–312. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talich, M.; Antoš, F.; Böhm, O. Automatic processing of the first release of derived state maps series for web publication. In Proceedings of the 25th International Cartographic Conference (ICC2011) and the 15th General Assembly of the International Cartographic Association, Paris, France, 3–8 July 2011. [Google Scholar]

- Iosifescu, I.; Tsorlini, A.; Hurni, L. Towards a comprehensive methodology for automatic vectorization of raster historical maps. E-Perimetron 2016, 11, 57–76. [Google Scholar]

- Oka, S.; Garg, A.; Varghese, K. Vectorization of contour lines from scanned topographic maps. Autom. Constr. 2012, 22, 192–202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schlegel, I. A holistic workflow for semi-automated object extraction from large-scale historical maps. KN—J. Cartogr. Geogr. Inf. 2023, 73, 3–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chiang, Y.-Y.; Leyk, S.; Knoblock, C.A. A survey of Digital Map Processing Techniques. ACM Comput. Surv. 2014, 47, 1–44. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leyk, S.; Boesch, R. Colors of the past: Color image segmentation in historical topographic maps based on homogeneity. GeoInformatica 2009, 14, 1–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ran, W.; Wang, J.; Yang, K.; Bai, L.; Rao, X.; Zhao, Z.; Xu, C. Raster map line element extraction method based on improved U-Net Network. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2022, 11, 439. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y.; Hinton, G. Deep learning. Nature 2015, 521, 436–444. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- LeCun, Y.; Bengio, Y. Convolutional networks for images, speech, and time series. In The Handbook of Brain Theory and Neural Networks; MIT Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1995; pp. 255–258. [Google Scholar]

- Minaee, S.; Boykov, Y.Y.; Porikli, F.; Plaza, A.J.; Kehtarnavaz, N.; Terzopoulos, D. Image segmentation using Deep Learning: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 2021, 44, 3523–3542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maxwell, A.E.; Bester, M.S.; Guillen, L.A.; Ramezan, C.A.; Carpinello, D.J.; Fan, Y.; Hartley, F.M.; Maynard, S.M.; Pyron, J.L. Semantic segmentation deep learning for extracting surface mine extents from historic topographic maps. Remote Sens. 2020, 12, 4145. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, C.; Heitzler, M.; Hurni, L. Extracting wetlands from Swiss historical maps with Convolutional neural Networks. In Proceedings of the Automatic Vectorisation of Historical Maps: International Workshop Organized by the ICA Commission on Cartographic Heritage into the Digital, Budapest, Hungary, 13 March 2020. Preprint. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uhl, J.; Leyk, S.; Chiang, Y.-Y.; Duan, W.; Knoblock, C. Extracting human settlement footprint from Historical Topographic map series using context-based machine learning. In Proceedings of the 8th International Conference of Pattern Recognition Systems (ICPRS 2017), Madrid, Spain, 13–17 July 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ekim, B.; Sertel, E.; Kabadayı, M.E. Automatic road extraction from historical maps using Deep Learning Techniques: A regional case study of Turkey in a German World War II map. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, Y.S.; Gerrits, P.J.; Kabadayi, M.E. Automatic detection of road types from the third military mapping survey of Austria-Hungary historical map series with deep convolutional Neural Networks. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 62847–62856. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Garcia-Molsosa, A.; Orengo, H.A.; Lawrence, D.; Philip, G.; Hopper, K.; Petrie, C.A. Potential of deep learning segmentation for the extraction of archaeological features from his-torical map series. Archaeol. Prospect. 2021, 28, 187–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Uhl, J.H.; Leyk, S.; Chiang, Y.-Y.; Knoblock, C.A. Towards the automated large-scale reconstruction of past road networks from historical maps. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2022, 94, 101794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Carlinet, E.; Chazalon, J.; Mallet, C.; Duménieu, B.; Perret, J. Vectorization of Historical Maps Using Deep Edge Filtering and Closed Shape Extraction; Lecture Notes in Computer Science; Springer: Cham, Switherland, 2021; pp. 510–525. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y. Modern Vectorization and Alignment of Historical Maps: An Application to Paris Atlas (1789–1950). Dissertation Thesis, IGN (Institut National de l’Information Géographique et Forestière), Saint-Mandé, France, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Vynikal, J.; Pacina, J. Automatic elevation contour vectorization: A case study in a deep learning approach. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2025, 14, 201. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ronneberger, O.; Fischer, P.; Brox, T. U-Net: Convolutional Networks for Biomedical Image Segmentation. In International Conference on Medical Image Computing and Computer-Assisted Intervention; Springer international publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2015; pp. 234–241. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allord, G.J.; Walter, J.L.; Fishburn, K.A.; Shea, G.A. Specification for the U.S. Geological Survey Historical Topographic Map Collection, Techniques and Methods. 2014. Available online: https://pubs.usgs.gov/publication/tm11B6 (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Digitization Standards, UVA Library. Available online: https://library.virginia.edu/digital-production-group/digitization-services/digitization-standards (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- USGS. Digital Scanning Hardware. Available online: https://www.usgs.gov/programs/national-geological-and-geophysical-data-preservation-program/digital-scanning-hardware (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Talich, M. Riches of Old Maps and Their Utilisation by Libraries and Other Memory Keepers, Library Revue. 2020. Available online: https://knihovnarevue-en.nkp.cz/archives/2020-2/reviewed-articles/riches-of-old-maps-and-their-utilisation-by-libraries-and-other-memory-keepers (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Kostrzewa, A.; Farella, E.M.; Morelli, L.; Ostrowski, W.; Remondino, F.; Bakuła, K. Digitizing historical aerial images: Evaluation of the effects of scanning quality on aerial triangulation and dense image matching. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3635. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liao, L.; Liu, W.; Liu, S. Effect of bit depth on cloud segmentation of remote-sensing images. Remote Sens. 2023, 15, 2548. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hu, C.; Sapkota, B.B.; Thomasson, J.A.; Bagavathiannan, M.V. Influence of image quality and light consistency on the performance of Convolutional Neural Networks for Weed Mapping. Remote Sens. 2021, 13, 2140. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poyser, M.; Atapour-Abarghouei, A.; Breckon, T.P. On the impact of lossy image and video compression on the performance of deep convolutional neural network architectures. In Proceedings of the 2020 25th International Conference on Pattern Recognition (ICPR), Milan, Italy, 10–15 January 2021; pp. 2830–2837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jo, Y.-Y.; Choi, Y.S.; Park, H.W.; Lee, J.H.; Jung, H.; Kim, H.-E.; Ko, K.; Lee, C.W.; Cha, H.S.; Hwangbo, Y. Impact of image compression on Deep Learning-based Mammogram classification. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 7924. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Chazalon, J.; Carlinet, E.; Ngoc, M.Ô.V.; Mallet, C.; Perret, J. Automatic vectorization of historical maps: A benchmark. PLoS ONE 2024, 19, e0298217. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vynikal, J.; Müllerová, J.; Pacina, J. Deep learning approaches for delineating wetlands on historical topographic maps. Trans. GIS 2024, 28, 1400–1411. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vynikal, J.; Pacina, J. Deep learning in historical geography. In Proceedings of the Juniorstav 2024: Proceedings 26th International Scientific Conference Of Civil Engineering, Brno, Czech Republic, 25 January 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pešek, O.; Brodský, L.; Halounová, L.; Landa, M.; Bouček, T. Convolutional Neural Networks for urban green areas semantic segmentation on sentinel-2 data. Remote Sens. Appl. Soc. Environ. 2024, 36, 101238. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pesek, O.; Krisztian, L.; Landa, M.; Metz, M.; Neteler, M. Convolutional neural networks for road surface classification on aerial imagery. PeerJ Comput. Sci. 2024, 10, e2571. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pešek, O.; Segal-Rozenhaimer, M.; Karnieli, A. Using convolutional neural networks for cloud detection on VENΜS images over multiple land-cover types. Remote Sens. 2022, 14, 5210. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).