2. Study Area, Materials and Methods

2.1. Study Area

Seville is the fourth most populous city in Spain, with 687,488 inhabitants in 2024 according to the National Statistics Institute (INE). Located in the south of the country, in the region of Andalusia, Seville constitutes an urban center of great relevance in historical, cultural, and economic terms. The city has a compact historic center of great heritage value, declared a World Heritage Site by UNESCO. This, coupled with the city’s strong cultural character, makes Seville one of the main tourist destinations in Europe, directly contributing to the city’s economic dynamism. However, this phenomenon also generates problems such as rising housing prices, increased cost and limited availability of basic services, and the development of gentrification and touristification phenomena [

37].

Beyond the historic center, the city has a large number of financial, university, or healthcare neighborhoods that emerged throughout the 20th century, and a series of peripheral areas with lower densities and more limited services. These are structured around a mobility system characterized by the coexistence of bus lines and bike lanes, factors that directly impact its urban structure and the daily life of its residents [

38]. However, the income levels, employment catchment areas, and service and education infrastructures vary enormously within the city. Consolidated residential areas and new peripheral developments coexist with highly marginalized neighborhoods with very limited levels of employment, education, and infrastructure. Seville is home to the three neighborhoods with the lowest average annual income per inhabitant in all of Spain and seven of the fifteen neighborhoods with the highest poverty rates in the country [

39].

Seville is divided into 524 census tracts. This spatial unit of analysis has been chosen based on several methodological and practical considerations. Firstly, this level of disaggregation ensures internal consistency and accuracy, and allows integration of multiple variables under a common spatial framework. Although census tracts are administrative, they are designed to represent internally homogeneous areas in terms of population size (usually 1000–2500 inhabitants) and built-environment characteristics. This makes them suitable for detecting fine-grained spatial patterns that would be obscured if larger units such as neighborhoods were used.

Using neighborhoods as units would also require arbitrary delineation or aggregation of tracts, which could amplify the Modifiable Areal Unit Problem (MAUP) and introduce subjective boundaries. Census tracts, by contrast, provide a standardized, replicable geometry across cities, minimizing interpretation bias. The spatial pattern of census tracts broadly aligns with the morphological and social structure of neighborhoods in Seville. To ensure this, the overlap between census tract boundaries and recognized neighborhood areas was inspected, verifying that the tracts capture meaningful intra-urban variations without distorting functional relationships.

2.2. Data

The categorization of the infrastructures has been structured around the six essential urban functions proposed in the 15-min city model [

11,

12]. The functions of housing and work were discarded due to the lack of detailed spatial data and lack of specification in the definition of accessibility criteria for these points [

29]. Instead, a fifth variable referring to public transport services as essential components for mobility was included. Furthermore, the urban function of commerce was divided into three categories linked to diverse objectives: supermarkets and food shops, other supplies (stationery stores, cleaning supplies stores, hardware stores, bookstores, news-stands, clothing stores, mobile phone shops, etc.), and other basic services (post offices, banks, hairdressers, laundromats, gyms, dentists, opticians, police stations, job centers, social services, etc.). [

19]. In turn, parks and green spaces were separated from other leisure spaces, a category which excluded facilities like bars and restaurants due to the distortion they present for measuring accessibility in tourist neighborhoods [

30].

The main sources used in the study were official data infrastructures from public organizations, as they are verified and comprehensive sources. All data are updated as of 1 August 2025. The 58,320 address points and the street lines of the city of Seville were downloaded from the Unified Andalusian Street Directory Portal, a platform maintained by the Institute of Statistics and Cartography of Andalusia (IECA). Land parcels were obtained from the Spanish Government Cadastre. The spatial data for the 524 census sections, with added demographical and economical information, come from the Seville City Council Open Spatial Data Portal. From this same portal, the 1267 points corresponding to bus stops and bicycle parkings were also downloaded. The locations included in the health, education, and green-spaces categories were downloaded entirely from the Reference Spatial Data of Andalusia portal, also created by the IECA, obtaining a total of 470 points associated with health centers, hospitals, and pharmacies; 498 points linked to kindergartens, schools, institutes, and university faculties; and 487 parks and green spaces. From the IECA, points for 57 large shopping centers and food markets, 50 infrastructures associated with basic services (job centers, post offices, and police stations), and 71 leisure spaces (libraries, museums, and sports centers) were also downloaded.

To obtain geolocated data for supermarkets, small businesses, and other services and leisure spaces not covered by official data infrastructures, OpenStreetMap and Overture Maps portals were used. The former, created in 2004, is a free and open data platform where volunteers capture, upload, store, and edit geographic information with the goal of providing accessible and up-to-date information that can be freely used by anyone [

40,

41]. Overture Maps, on the other hand, is a collaborative open map data project launched in 2022 by major technology companies (Meta, Microsoft, Amazon Web Services, and TomTom), which integrates open data with other public and private providers, although this aggregation is incomplete, making it necessary to use both sources for a more detailed analysis. From the initial database of 8470 points of interest located in OpenStreetMap, 1979 facilities linked to the study were selected, obtaining 571 points associated with supermarkets and food shops, 747 points belonging to other supply stores, 617 points representing basic services, and 44 leisure centers such as theaters, nightclubs, cinemas, or art centers. Regarding Overture Maps, the starting point was a database of 18,313 points of interest, from which 3754 locations not available in OpenStreetMap were filtered. These include 598 food shops, 1661 other supply stores, 1431 service points, and 64 leisure spaces.

Once the data from the three sources used were aggregated into a single spatial-point layer, a total of 8558 facilities were counted (

Table 1). Finally, data on tourist accommodations downloaded from the Inside Airbnb portal were used to validate the synthetic 15-min city index alongside the previously mentioned information from the census sections of the city of Seville. This data is updated as of 26 March 2025.

2.3. Methodology

The first step consisted of selecting the 48,487 address points located on residential parcels. Next, a transportation network was designed using ArcGIS Pro 3.5.4., utilizing only the street map of Seville. Public transportation lines or road information were not incorporated, based on the premise of analyzing facilities available within a maximum 15-min walking distance. In creating the network, a travel time field

t was incorporated for each street

c using the following formula, where

is the distance for each street (previously converted to kilometers), and 4 refers to the average walking speed of a pedestrian in km/h. Once the travel times in hours were obtained, they were converted to minutes.

The next step involved the creation of isochrones using the ArcGIS Pro network analysis tool. The chosen parameters were the 48,487 residential address points as origins, the calculated travel times for the street network as impedance, walking as transport mode, and a maximum travel time of 15 min (

Figure 1).

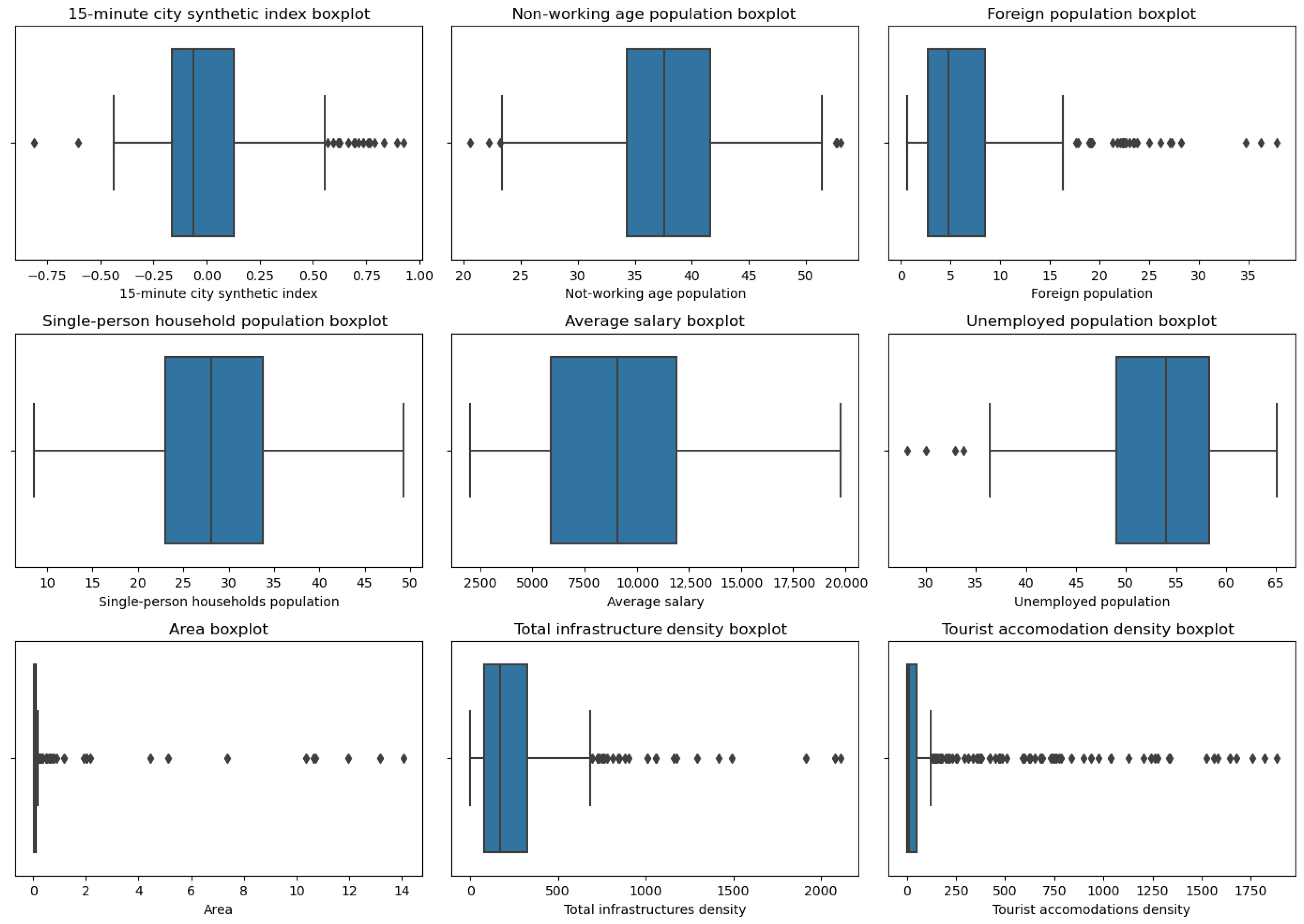

The 8558 identified facilities were spatially joined according to their functionality to each calculated isochrone. This filtered out infrastructures located beyond a 15-min walking distance, resulting in 8102 available points (94.67% of the total). Due to frequent overlaps in the isochrones, it was decided to work at the census section scale of the city.

Next, a dual homogenization process was carried out to obtain more robust results. First, both population densities and the number of facilities per category were calculated by dividing their values by the area of each census section measured in km

2. This is necessary due to the large size of census sections located on the city’s periphery, where both population and services are concentrated in specific zones, while the remaining area is occupied by industrial estates, technology parks, or transport infrastructures. The second step involved normalizing all the variables, placing different value ranges on the same scale and preparing specific indices to serve as the basis for the final synthetic index. In the followed formula,

is each value obtained for a category

,

is the mean value of that category, and

is the standard deviation.

Once the data were standardized into indices (μ = 0, σ = 1), it was confirmed that the direction of all indices was consistent (negative signs for values indicating a lack of facilities and positive signs for values indicating the presence of infrastructures). Then, an Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) regression was performed to estimate weighting coefficients for the calculation of the final synthetic index. For this purpose, the population density index was used as the explanatory variable, and the density indices of the eight defined facility categories (

Table 1) were used as dependent variables. Population density is a key structural determinant of urban accessibility and functional proximity, characteristics inherent to 15-min city models. By using population density as the explanatory variable, the model tests whether areas with higher residential concentration offer greater accessibility to everyday urban functions, which aligns with theoretical and empirical evidence from urban studies.

The Moran’s I test corroborated a strong spatial autocorrelation in the OLS model. Therefore, a Geographically Weighted Regression (GWR) was chosen for accounting the spatial variation in the relationships between variables [

42,

43]. This model yields local coefficients that reflect the influence of the studied variables on the 15-min city concept and identifies areas where each variable individually has a higher or lower explanatory power [

44,

45].

The GWR model was applied to the 524 study sections with an optimal bandwidth of 180. The chosen bandwidth balances local sensitivity and model stability, avoiding both overfitting (too small bandwidths) and excessive smoothing (too large ones). Although the model shows a significant improvement in its parameters, it still suffers from spatial autocorrelation issues. While this indicates that there are still spatial patterns not captured, or complex effects at play, the local coefficients are exploratory and descriptive in nature and still reflect spatial variations, providing a valid basis for constructing a weighted synthetic index (SI), which was developed using the following formula, where each variable

z refers to one of the eight studied dependent variables. The weighting values used are based on the average coefficients obtained (

Table 2).

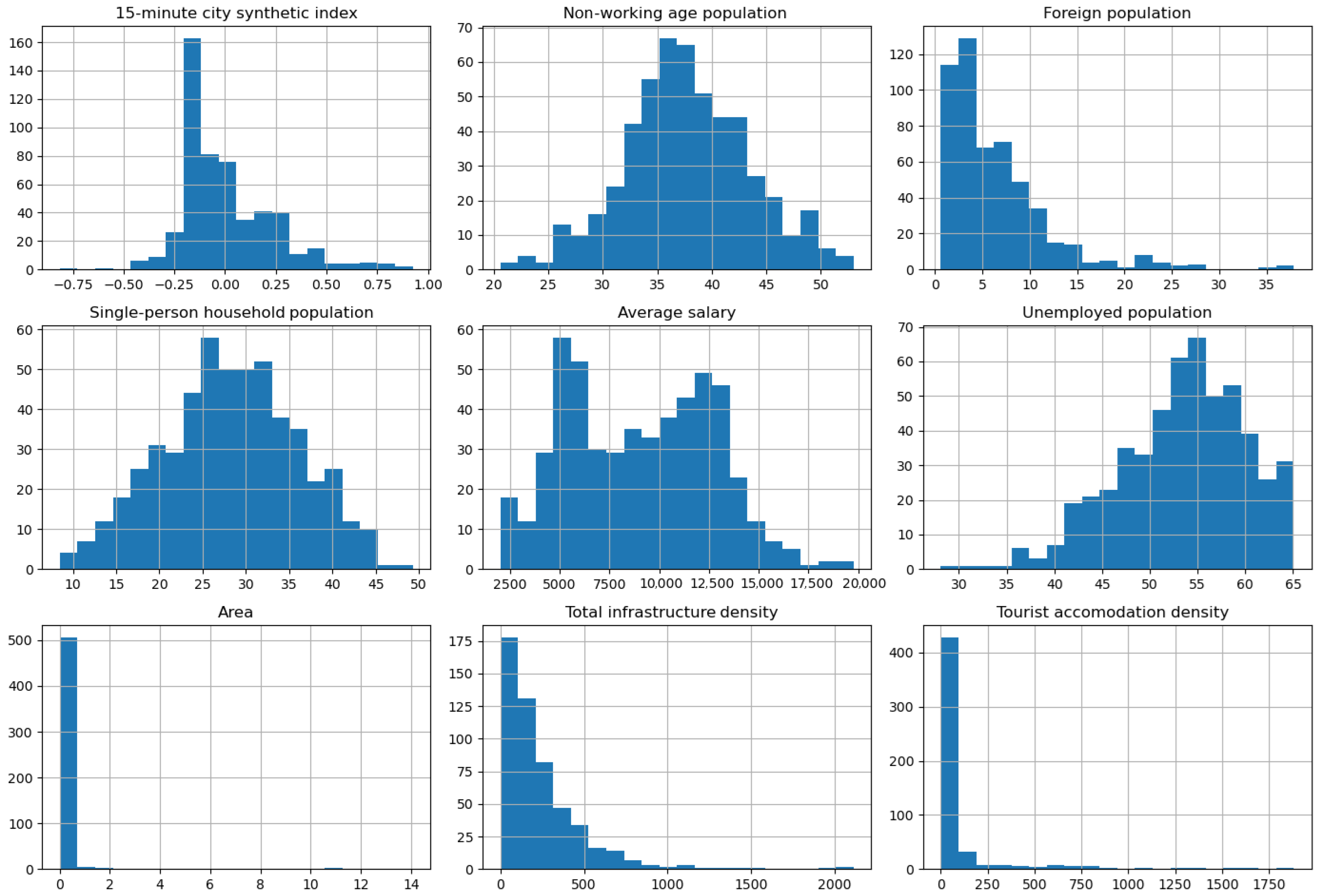

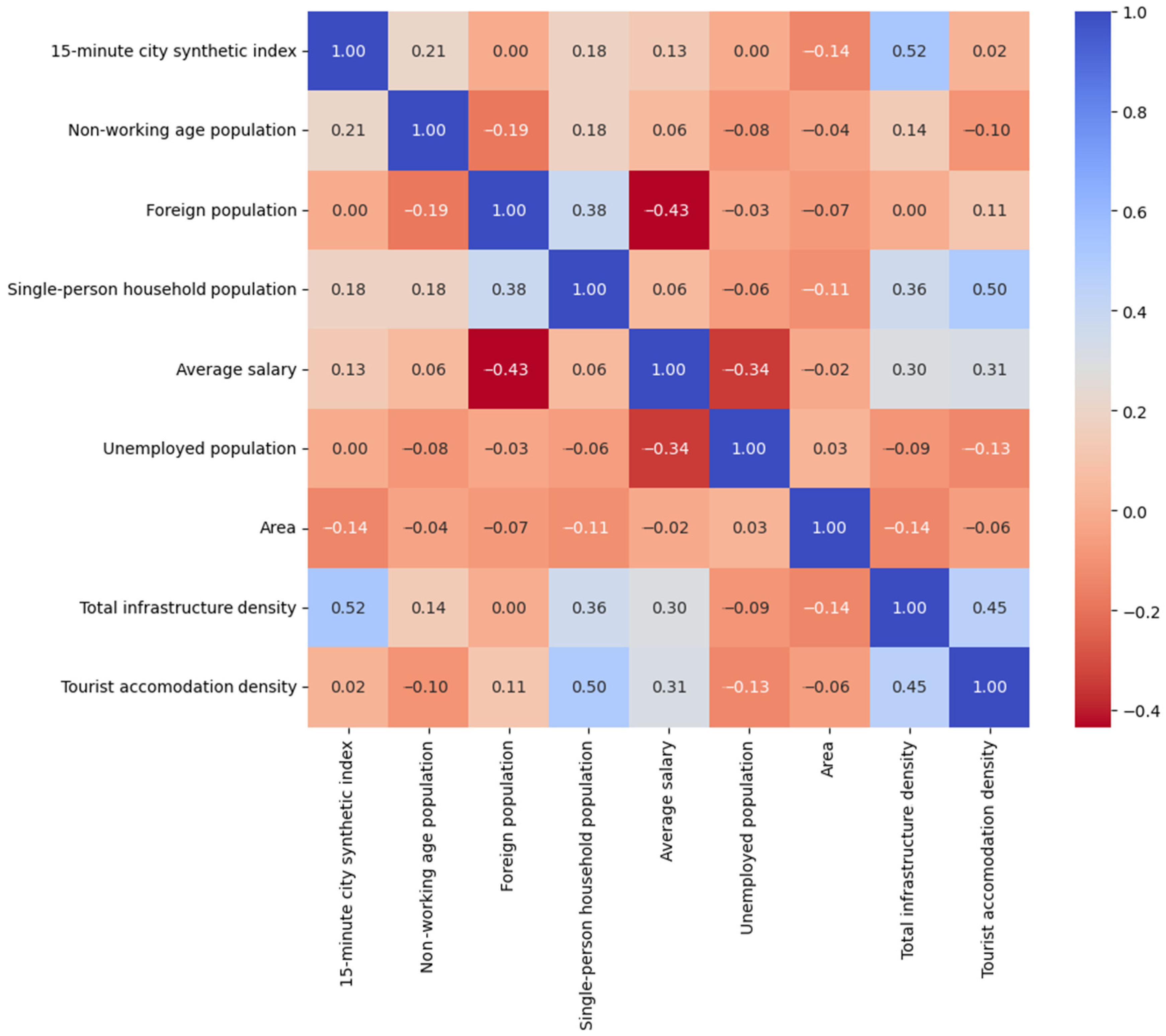

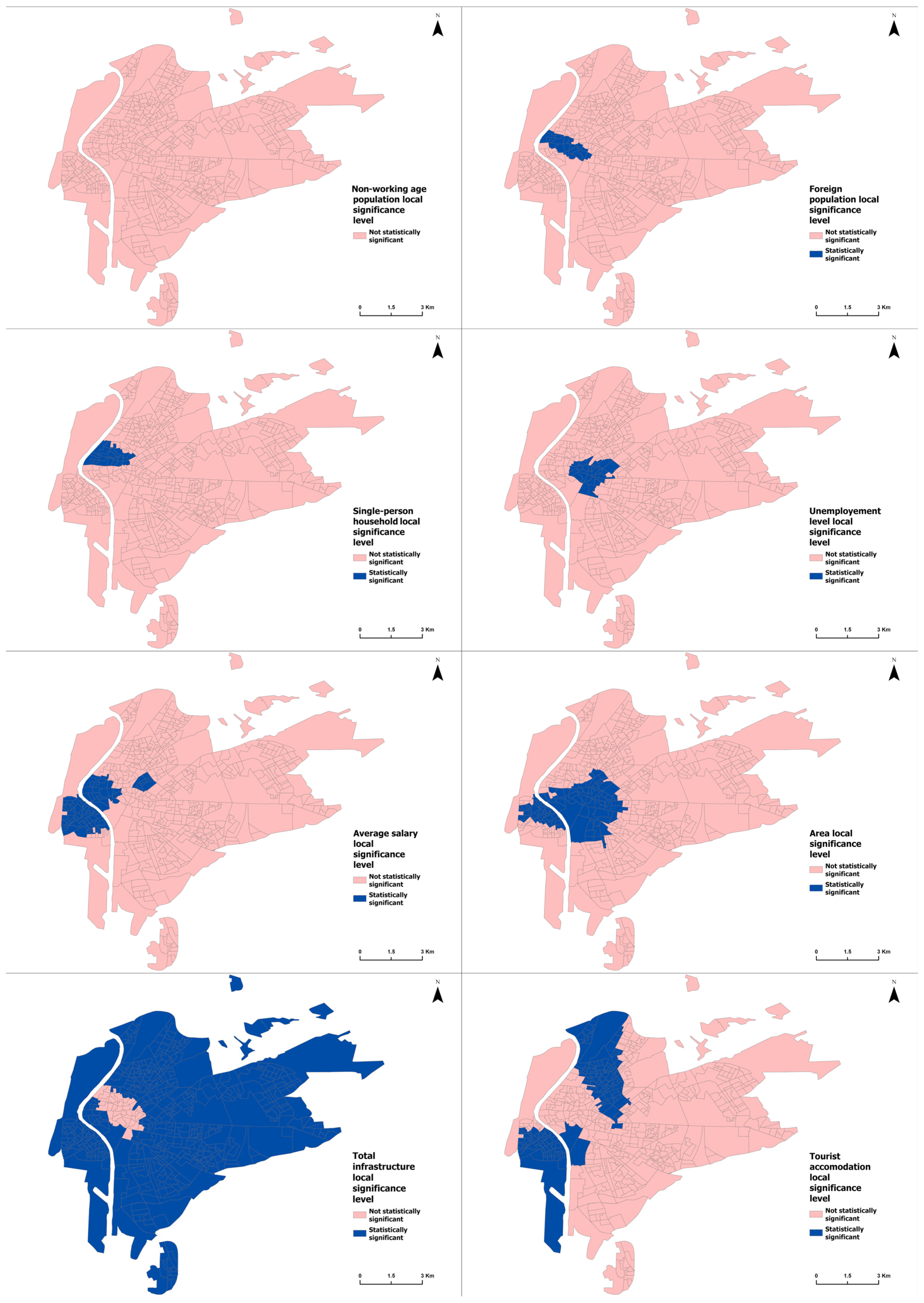

Once the 15-min city synthetic index was calculated, its effectiveness was validated using a second GWR model to analyze the spatial effect of the variables listed in

Table 3. Unlike the first GWR model, the absence of spatial autocorrelation in the residuals allows this second model to serve as a theoretical basis for explaining the local effects that either facilitate or hinder the fulfillment of the 15-min city concept in different areas of Seville. The variable for density of commercial facilities includes the total of 8558 obtained facilities, meaning this variable acts as a control factor that distinguishes between the quantity of available facilities and their distribution within access times of less than 15 min.

4. Discussion

The results highlight the capacity of the methodology based on open geospatial data, isochrone analysis and spatial regression to measure and compare the implementation of the 15-min city model across different urban contexts. This is achieved by using Seville as a validation laboratory through which to corroborate the viability of the proposed methodology. In this way, the results confirm previous research identifying density, mixed land use and service distribution as fundamental components of urban proximity [

11]. These findings suggest that proximity projects are not merely a matter of urban design, but also of distributive policy, the prioritization of mobility modes, and the regulation of the land and housing market [

20].

In this regard, the literature has emphasized that the 15-min city model cannot be understood as a mere planning technique, but as a political tool that challenges historical dynamics of zoning and urban fragmentation [

2,

6]. The evidence from Seville reinforces the idea that proximity is closely tied to structural inequalities, which directly connects with criticisms regarding the limits of urban compactness models [

5]. By reproducing patterns described in the literature, the analysis validates the feasibility of using geospatial data infrastructures to operationalize the 15-min city concept.

In this regard, the combined use of open data from OpenStreetMap and Overture Maps has provided significant value for the study and measurement of the 15-min city model, by providing detailed, updatable and freely accessible geospatial information on the location of urban services, facilities and mobility networks. These platforms enable the identification and classification of key urban functions—such as food retail, education, health care, and mobility infrastructures—with high spatial resolution and interoperability across datasets. Their integration strengthens the reliability of isochrone-based accessibility models and supports the spatial regression analysis by ensuring consistent spatial coverage of urban amenities. This methodological synergy confirms that open geospatial data infrastructures can effectively capture the complexity of proximity patterns in contemporary cities, providing a scalable and reproducible approach to measure the implementation of the 15-min city model across diverse urban contexts, and helping to cover blind spots serving as a quantitative risk proxy for different functional spaces [

46,

47].

From a planning perspective, the integration of spatial optimization techniques within the methodological framework opens the door to simulating alternative service configurations aimed at improving proximity and reducing accessibility gaps. By combining isochrone analysis with optimization models, it becomes possible to identify areas where the location or reallocation of public facilities would maximize coverage with minimal travel times, particularly for vulnerable populations. This approach contributes to a more evidence-based and equitable implementation of the 15-min city principles, transforming open geospatial data not only into a diagnostic tool, but also into a foundation for strategic spatial design and policy-oriented urban planning [

46,

47].

Analysis of the spatial distribution of different services also emphasizes the role of public facility accessibility as a central dimension of the 15-min city framework. Accessibility to education, health care, and everyday services not only determines the functional efficiency of urban areas, but also reflects the fact that broader patterns of spatial justice are a prominent factor affecting people’s livelihood [

46]. In Seville, food stores, retail, and services form the main functional cluster of the urban system, concentrating in in areas with higher centrality. Regarding the other categories, the accessibility disparities reveal that while these central and intermediate districts benefit from dense and diversified public facilities, peripheral neighborhoods experience structural deficits that limit residents’ ability to meet daily needs locally. These findings are consistent with studies that link uneven facility accessibility to patterns of socio-spatial inequality and urban polarization, underscoring the need to integrate accessibility planning into broader strategies of social cohesion and inclusive urban development [

46].

Regarding zonification, the results identified three urban typologies that the methodology is capable of distinguishing: highly touristified cores with service specialization; mixed-function districts with balanced accessibility; and peripheral self-contained neighborhoods with infrastructural deficits. Thus, the historic center combines low population density with a strong orientation towards commerce and tourist consumption. Consequently, the majority of the city’s leisure facilities are concentrated almost exclusively in this area, but a lack of basic infrastructure such as education, public transport, and, to a lesser extent, healthcare, is also observed. This finding aligns with recent studies which indicate how the concentration of services in central areas of European cities can intensify social segregation and gentrification [

19,

29,

48,

49].

The second area, comprised of districts surrounding the historic center, combines residential and tourist functions. Although its urban typology is similar to that of the historic center (the commerce and tourism-oriented area, with a large number of restaurants), it also has basic facilities such as educational and health centers that serve the local population. However, its low population density produces the presence of a wide range of specialized retail and services, which results in a lower density of shops and basic retail targeting middle-income populations who cannot afford to live in this area of the city.

In the most remote districts, education, health, and public-transport centers show a broader distribution, with positive densities, which responds to the isolated nature of outer neighborhoods, configured as small self-sufficient towns within the municipal boundary, though disconnected from the main urban core. This pattern is also repeated in residential neighborhoods in the north, east, and south of the city, where vulnerable neighborhoods with greater service deficits are concentrated.

The mapping of the 15-min city synthetic index indicates that districts surrounding the historic center (the Triana and Nervión districts in the case of Seville) are those that best adapt to this model, primarily due to their wide availability of retail and services for their population. In contrast, the historic center generally shows negative indices, due to the specialization of retail and leisure spaces targeting the tourist market and a gradual decline in basic establishments, which, combined with low population density, has led to processes of gentrification [

37]. For their part, residential and isolated peripheral neighborhoods show neutral values, with a certain degree of self-sufficiency in services which, however, are not always sufficient to meet the population’s needs. Although southeastern and eastern neighborhoods follow this pattern, they contain large areas with low infrastructure density and limited access to essential services for the most vulnerable populations. This differentiation aligns with previous findings [

27,

47], suggesting that the method accurately captures common spatial hierarchies of service accessibility observed in compact European cities.

The regression analysis demonstrates that the model effectively captures correlations between accessibility and socio-economic indicators, consistent with the literature linking variables such as income, land-use diversity, and walkability [

19,

29,

30]. When analyzing the case of Seville, it is observed that neighborhoods with a greater variety of facilities show low R

2 coefficients and positive significance in most variables, which indicates that factors such as income level or demographic characteristics influence the index, though the total variation is reduced due to the consolidation and homogeneity of some of these areas. In contrast, areas further away from the center show low R

2 coefficients and positive significance only in the variable of total infrastructure density, showcasing greater inequality in these neighborhoods. This indicates low sensitivity of the model to uniform areas and higher responsiveness in heterogeneous contexts.

In Seville, the central districts show positive associations between the 15-min city index, foreign population, and service density, reflecting compact areas with strong accessibility but also emerging processes of gentrification and rising housing costs [

37]. Conversely, higher unemployment and the concentration of tourist accommodation in the historic center point to ongoing touristification and residential displacement. In peripheral neighborhoods, the index remains low, despite adequate infrastructure levels, underscoring persistent deficits in everyday services and the need to strengthen proximity facilities in socio-economically disadvantaged areas.

Residual analysis identifies over- and underestimation patterns related to morphological and functional factors not explicitly modeled, such as street layout or non-residential land uses (particularly in the city center and surroundings, due to tourist saturation or loss of residential services; and zones in the south of the city corresponding to university campuses). These patterns confirm the model’s ability to detect spatial anomalies and its dependence on data granularity. Such sensitivity represents both a limitation and a potential diagnostic advantage when applied to cities with diverse urban fabrics.

The ability to replicate well-documented urban patterns using open and standardized data confirms that the approach is suitable for conducting comparative analyses to assess the spatial coherence and equity dimensions of the 15-min city model in other European and Latin American cities.

5. Conclusions

This study advances understanding of the 15-min city model by highlighting how contextual factors shape its implementation, and provides an empirical basis for designing urban policies aimed at reducing territorial disparities and improving equity in access to services. The results emphasize the shortage of citizen-oriented facilities and the impact of touristification in Seville’s historic center, together with limited accessibility in peripheral and vulnerable neighborhoods. Proximity depends not only on infrastructure provision, but also on demographic, socio-economic, and urban dynamics such as touristification and gentrification. The information obtained can guide governance strategies integrating demographic, economic, and infrastructural dimensions to reduce internal inequalities. In conclusion, the study reinforces the need to address the 15-min city from a comprehensive perspective, combining accessibility and proximity criteria with redistributive policies in housing, mobility, and urban services [

8].

The findings underscore three points. First, the 15-min city must be assessed considering urban processes, such as tourism pressure or land valorization, which reshape accessibility. Second, the presence of facilities does not ensure equitable access, as market dynamics, commercial specialization, and mobility constraints condition their use. Finally, synthetic models are useful for mapping territorial inequalities and guiding public policies, provided they are complemented by qualitative studies that capture citizen practices and perceptions.

This work has also demonstrated the potential of combining open geospatial and official data to map the degree of the 15-min city model compliance in a heterogeneous city like Seville. Open, geolocated datasets enable the analysis of socio-demographic and infrastructural variables explaining spatial variability. This approach leverages the advantages of these new data sources, such as their high volume, periodicity, and spatial detail, providing a complementary perspective to traditional data-based approaches. The methodology is reproducible and easily applicable to other cities and scales.

However, several limitations must be acknowledged. Although open datasets such as OpenStreetMap and Overture Maps integrate diverse facilities, they still show inconsistencies and uneven data quality, requiring careful validation. This reveals biases towards leisure-related establishments and limits coverage of basic infrastructures. Regarding official data, the main limitation is the dependency on the availability of specific data, which required integration with new geospatial data sources to mitigate this constraint.

Other limitations are theoretical. Applying proximity as the main organizing principle of urban space involves the task of redistributing functions based on various geographic, economic, and social principles, such as threshold population and market coverage. It also requires prioritization and relocation of public functions [

1]. Implementing the 15-min city model requires legislative provisions, a governance structure focused on the city’s unique characteristics, and the promotion of housing policies.

Future work should integrate open data with human mobility sources, like GTFS public transport files or origin–destination travel matrices, build temporal datasets to track morphological and structural change, and explore touristification through specific variables; it might integrate the concept of the 45-min territory into the 15-min city theoretical framework, which posits that workplaces should be within a maximum of 45 min by public transport from one’s residence.