Abstract

Humans typically describe spatial location using names, hierarchies, and relative positions (e.g., east of, inside), yet mainstream GIS represents places primarily through geometric coordinates, rendering qualitative spatial queries computationally challenging. We introduce the Qualitative Place Model (QPM), a GIS-native framework that transforms standard boundary datasets and place layers into structured knowledge bases of Qualitative Place Description (QPD). QPM provides a homogeneous representation whereby administrative units and physical places are treated uniformly as Place entities. The model materializes a compact set of local relations, hierarchical containment, directional neighbourhood, and optional proximity, that support rich inferences through sound logical operations (inverse relationships and per-predicate transitive closure). We implement QPM as an ArcGIS Pro toolbox that computes and persists QPDs within a geodatabase, with optional RDF export for SPARQL querying. This implementation enables natural-language-style spatial queries such as “Where is x?” or “Which places are north of x?” within standard GIS workflows. Evaluation on Wales (UK) administrative, postal, and electoral hierarchies plus a comprehensive place layer demonstrates robust performance: QPM generated 95.8% of expected basic-place statements (52,821 places) and achieved 89.7–96.5% coverage across administrative hierarchies. All QPDs proved unique under our deterministic signature. Despite compact storage requirements, directional relations expand by more than an order of magnitude (10.6× overall expansion) under logical closure, demonstrating substantial inferential power from a minimal stored representation. QPM complements geometric GIS with an explainable qualitative layer that aligns with human spatial cognition while remaining fully operational within standard GIS environments.

1. Introduction

Place is a multifaceted concept spanning sense of place, geographic location, and locale [1,2]. In everyday communication, humans answer where? questions qualitatively by combining names, hierarchies, and relative positions (e.g., “Cardiff University is east of the Wales Police Station, inside Cathays ward”) [3,4]. Such descriptions rely on hierarchical containment (country → authority → ward) [5,6] and neighbourhood semantics (e.g., inside, north of, touching).

However, mainstream Geographic Information System (GIS) model places primarily as geometric objects (points, lines, polygons), emphasising coordinates and boundaries [7,8]. While indispensable for precise mapping and quantitative analysis, these geometric data models inadequately support relational, human-centric place descriptions, the primary mode through which spatial knowledge is communicated [3,9]. This limitation is particularly significant because qualitative place references in natural language often lack precise or authoritative geometries (e.g., venues without published footprints, informal neighbourhoods), yet their spatial facts remain meaningful and actionable (“north of the station”, “within Cathays”).

A GIS that represents and manipulates qualitative relations alongside geometry would enable such descriptions to be captured, queried, and reasoned over natively, rather than requiring externalization to specialized scripts or web-based knowledge graphs [4,10].

Authoritative boundary datasets, e.g., administrative, postal, electoral, inherently encode space as multi-level partitions. Conceptually, these form Discrete Local Irregular Grid Systems (DLIGS), providing robust, maintained frameworks for hierarchical containment and adjacency [11]. If these datasets could be utilized within GIS to derive and store qualitative relations (e.g., inside, touches, north_of) and link them to named places, then two significant capabilities would emerge: (i) natural-language place descriptions could be represented and queried within standard GIS workflows, and (ii) qualitative and quantitative representations could be jointly exploited, each compensating for the limitations of the other.

Qualitative Spatial Reasoning (QSR) provides calculi for topological and directional relations and has long advocated for cognitively faithful spatial representations [12,13]. Parallel research in place studies advocates place-based GIS that treats places as objects with attributes and relationships, rather than as isolated geometries [9]. However, these research directions often remain external to operational GIS: QSR models are frequently demonstrated on abstract datasets or external knowledge graphs, while most GIS platforms lack a homogeneous, in-platform model that treats geographic places uniformly, and implements end-to-end computation, storage, and querying of qualitative place descriptions within the GIS environment.

We present the Qualitative Place Model (QPM), a GIS-native framework that transforms standard boundary layers and place layers into structured knowledge bases of Qualitative Place Descriptions (Qualitative Place Descriptions (QPDs)). QPM adopts a homogeneous representation of geographic place. The model computes and stores (i) containment (place → parent unit per hierarchy) and (ii) directional neighbourhoods (nearest neighbours in cardinal sectors for places; touching neighbours for units), then exposes these relations within the GIS environment (with optional export to RDF for SPARQL queries).

This research makes four principal contributions to spatial information science:

- Homogeneous place formalism. A unified, hierarchy-aware model where geographic places share a single representational scheme supporting qualitative relations for human-centric spatial queries.

- Deterministic in-GIS computation. Practical algorithms for parent assignment and directional neighbourhood computation with explicit contracts and deterministic tie-breaking, implemented within a GIS.

- Compact storage with rich inference. Minimal, deterministic stored relations expand substantially under logical inference (inverse relationships and transitive closure), enabling expressive queries without storage overhead.

- Empirical validation across real hierarchies. Evaluation with UK open geographic datasets demonstrates unique QPDs, robustness across diverse hierarchical structures, and practical GIS querying support.

QPM complements geometric GIS with an explainable qualitative layer providing compact storage and substantial inferential power. The framework enables natural-language spatial queries (“Where is x?”, “Which places are north of y?”) within standard GIS workflows while augmenting rather than replacing geometric representations.

Section 2 reviews related work in qualitative spatial reasoning and place-based GIS. Section 3 provides the formal model definition. Section 4 presents the conceptual design and computational framework and details the GIS implementation. Section 5 reports empirical evaluation results; Section 6 discusses implications and limitations; Section 7 presents conclusions and future research directions.

2. Related Work

This section reviews approaches to qualitative modelling of place in general and in particular within GIS environments.

- Qualitative place models and spatial knowledge graphs

Research in qualitative spatial representation has developed theoretical frameworks and computational implementations that move beyond purely geometric approaches. QSR formalizes topological and directional relations while advocating naïve geography as a cognitively faithful foundation for spatial systems [13,14,15]. These methods align with cognitive research demonstrating that humans naturally describe places through hierarchical containment and relative positioning [3,6].

Computational implementations of these concepts have emerged primarily through place graphs and semantic web technologies. Place graphs model spatial entities as nodes connected by qualitative relations derived from textual sources or volunteered geographic information [16,17]. Chen et al. [4] demonstrate queryable place graphs capable of answering qualitative spatial questions through graph traversal algorithms. Semantic web approaches have proven particularly successful at encoding qualitative spatial relations, exemplified by the RelLoc framework [18], which represents spatial relationships as RDF triples. National mapping agencies, including the Ordnance Survey, have published comprehensive RDF models of administrative geography supporting linked data queries [19], while large-scale knowledge graphs such as KnowWhereGraph integrate diverse geospatial entities and relations [20,21].

These approaches excel at representing qualitative spatial relationships and support rich inferential capabilities. However, they typically operate on specialized platforms (graph databases, RDF triple stores) or semantic web infrastructures that remain external to the GIS environments where most spatial analysis and cartographic production occurs [22]. This separation creates adoption barriers in operational contexts and limits the integration of qualitative and quantitative spatial reasoning.

- Qualitative and place modelling within GIS environments.

Limited research has explored qualitative spatial modelling directly within GIS platforms, recognizing the need to bridge theoretical frameworks with operational spatial analysis tools. Almuzaini [23] developed prototype qualitative neighbourhood functionality within Quantum GIS, demonstrating the feasibility of implementing QSR concepts in open-source GIS environments. Giordano et al. [24] and Martin et al. [25] have combined quantitative and qualitative insights for analysing narrative and user-generated spatial data, showing the complementary value of both approaches.

Place-based GIS research advocates treating places as objects with attributes and relationships rather than as isolated geometries [9], aligning with Agnew’s emphasis on understanding places in relation to other places [1]. Recent work on homogeneous hierarchical models integrates global and local grids to support multi-scale reasoning [11], though this research focuses primarily on topological structure rather than qualitative relationships.

Despite these advances, existing GIS-based approaches remain either domain-specific, limited in scope, or focused on specific aspects of qualitative representation. Notably absent is a comprehensive, scalable framework that systematically defines places across multiple hierarchies while supporting both storage and querying of qualitative spatial relationships within standard GIS workflows.

Comparing these approaches across key analytical dimensions reveals complementary strengths and persistent limitations. Inferential capabilities and query expressiveness vary significantly: semantic web solutions (LinkedGeoData, GeoSPARQL) provide rich ontological reasoning and support complex SPARQL queries with full inferential closure, while standard GIS platforms offer efficient geometric computations but lack systematic support for logical inference over qualitative spatial relationships. Platform integration presents a critical divide: semantic approaches operate external to GIS workflows, requiring data export/import cycles that disrupt integrated analysis, while GIS-native geometric operations remain bound to coordinate-based predicates. Storage efficiency and scalability expose fundamental trade-offs: knowledge graphs typically materialize complete relationship networks, achieving query performance through substantial storage overhead and complex update procedures; standard GIS computes relationships on-demand, avoiding storage costs but incurring repeated computational expense.

QPM addresses these limitations by integrating qualitative spatial representation within rather than alongside GIS environments. Building on relational concepts from RelLoc [18] and aligned with place-based GIS perspectives [9], QPM provides a homogeneous GIS-native framework treating geographical objects uniformly while supporting efficient computation, storage, and querying using standard GIS technologies. The approach demonstrates the enablement of qualitative spatial reasoning within the practical constraints of operational GIS workflows.

3. Qualitative Place Model Definition

QPM addresses three fundamental design requirements for qualitative place representation. Homogeneous representation treats both administrative units (e.g., districts, wards) and named places (e.g., landmarks, settlements) uniformly as place instances, enabling consistent spatial reasoning across entity types. Hierarchical anchoring with lateral semantics defines place location through hierarchical containment while capturing neighbourhood relations (touching, proximity, directional orientation). GIS integration supports scalable computation from standard boundary datasets with seamless integration into existing GIS and ontological frameworks.

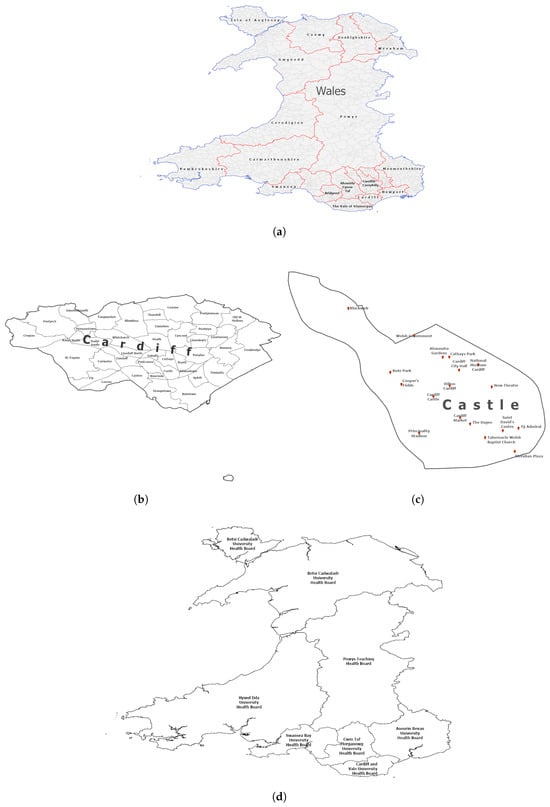

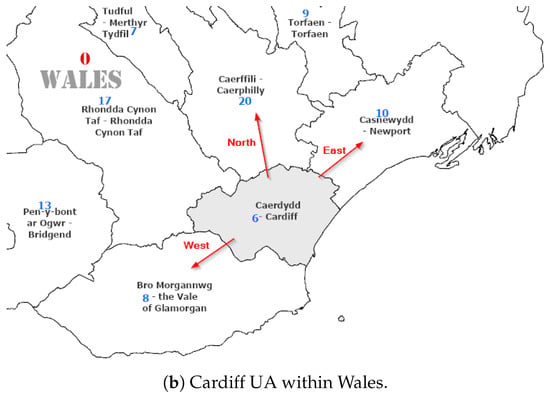

Each place is spatially defined through: (a) a unique parent within a containment hierarchy, and (b) its neighbours at the same hierarchical level, connected through adjacency, proximity, and directional relations. This approach accommodates geometry-appropriate relationship definitions (polygons support adjacency relations; points do not). Figure 1 show two adminstrative hierarchies of the Wales, Uk; Unitary Authorities (a) and Health districts (d). Figure 1b,c shows further divisions of unitary authories to Wards and a sample geographic places inside a ward unit. Figure 2 shows a sample of the types of spatial relationships that are captured by the model. The formal definition of these relationships follows.

Figure 1.

Sample data representing different administrative hierarchies of Wales, UK, subdivisions of hierarchies and geographic places. (a) Map of Wales divided into unitary authorities. (b) The unitary authority of Cardiff divided into wards. (c) A sample of base geographic places inside the Castle ward in Cardiff. (d) Map of Wales divided into health districts with overlapping boundaries to the unitary authorities.

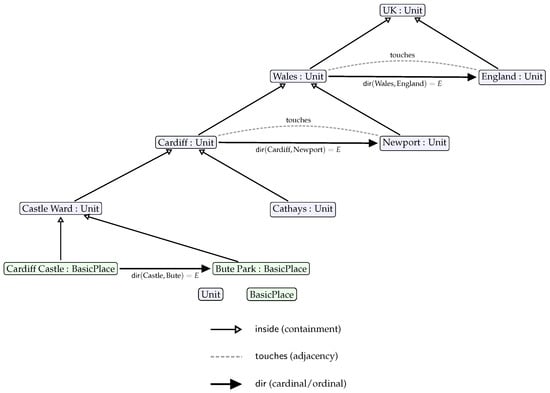

Figure 2.

QPM as a homogeneous model of place. Units and Basic Places are both Place instances. Place location is given by a unique containment path () and neighbourhood relations: (adjacency) and (direction).

3.1. Formal Model Definition

QPM operates under four fundamental assumptions that ensure computational tractability and semantic consistency. Partition completeness (A1) requires that each hierarchical level partitions the extent of level without gaps or overlaps, with all units represented as valid planar polygons. Point representation (A2) constrains Basic Places to point geometries for computational efficiency. Coordinate reference consistency (A3) requires consistent distance and bearing calculations appropriate to the coordinate reference system. Directional partitioning (A4) requires that the set of directional sectors D partitions the angular space into equal half-open wedges, avoiding boundary ambiguity in directional assignment. Unless otherwise specified, QPM employs 4-way directional sectors for computational simplicity while maintaining cognitive alignment with natural language directional references.

Hierarchical Structure and Place Definition

QPM represents spatial organization through a hierarchy of spatial divisions, where each level consists of a set of spatial entities termed places. The model defines a single superclass Place with two principal specializations that enable homogeneous treatment of diverse geographic entities:

Unit ⊑ Place represents fiat polygonal regions that form components of spatial partitions at level (e.g., countries, districts, wards). These administrative or postal divisions provide the hierarchical framework within which other places are located.

BasicPlace ⊑ Place represents named locations with point geometries (e.g., landmarks, settlements, facilities). These correspond to the places that humans typically reference in spatial discourse.

The hierarchical structure ensures complete spatial coverage through systematic partitioning. Each level completely partitions its parent region according to:

This formalization ensures that every spatial unit has exactly one parent within the hierarchical structure:

Consequently, each place’s spatial location is uniquely identified through two complementary mechanisms: A containment path extending from the root unit to its immediate container, and its lateral neighbourhood relationships at the corresponding hierarchical level. This dual characterization enables both hierarchical reasoning (through containment chains) and lateral reasoning (through neighbourhood relations).

Basic places are assigned to base-level units within each hierarchy, the finest spatial resolution level representing elementary geographic divisions (e.g., community wards within administrative hierarchies, postal sectors within postal hierarchies). This assignment ensures that place locations are anchored at the most granular spatial scale while hierarchical containment paths provide broader geographic context through transitive relationships (e.g., a place in Castle ward is also in Cardiff authority through the containment chain).

3.2. Spatial Relations: Definitions and Computation

QPM defines four fundamental binary relations that capture essential spatial relationships between places. These relations are designed to support both local spatial reasoning (immediate neighbours and containment) and extended spatial inference through logical composition and transitivity. Each relation is defined formally and accompanied by its computational procedure to ensure reproducible implementation.

3.2.1. Hierarchical Containment

The foundational relation (hierarchical containment) establishes the unique containment hierarchy that anchors place location. This relation is both functional and transitive, ensuring that each place has exactly one parent while supporting multi-level hierarchical reasoning.

Containment relationships establish the hierarchical foundation of QPM by assigning each spatial entity to its unique parent within the hierarchy. For spatial units and potential parents :

For Basic Places represented as points, containment is determined through point-in-polygon analysis:

where point P is assigned to the unit u whose polygon geometry contains the point location.

For hierarchical partitions where level forms complete tessellation, each unit in receives unique geometric parent assignment. The algorithm computes representative interior points and employs spatial indexing for efficient point-in-polygon queries, achieving performance while flagging boundary conflicts for quality assurance. This computational approach ensures that every place has a well-defined position within each relevant spatial hierarchy. In Figure 1, Castle ward and Cathays ward are inside Cardiff unitary authority and Cardiff Castle and Bute Park are inside Castle ward.

3.2.2. Topological Adjacency

(planar adjacency) defines a symmetric relation between polygonal units sharing non-empty boundary intersections, applicable exclusively to polygonal units. This topological relation identifies immediate spatial neighbours and provides the foundation for directional relationship assignment and proximity analysis. Basic Places, represented as point geometries, do not support topological adjacency; their spatial neighbourhoods are instead defined through distance-based directional relationships (Section 3.2.3) and graph-based proximity (Section 3.2.4).

For units at the same hierarchical level, where :

This topological definition captures the intuitive notion of spatial neighbours while avoiding dependency on coordinate precision issues. The adjacency computation forms the basis for directional relationship assignment and proximity analysis.

3.2.3. Directional Orientation

QPM implements two complementary directional relations that capture spatial orientation between places. (directional orientation) establishes orientation relationships between neighbouring units in directional sector , while (primary directional choice) provides a functional directional relation by selecting a single representative neighbour per directional sector.

The distinction between general orientation () and primary directional choice () enables QPM to balance expressive power with storage efficiency. While can represent multiple neighbours in each direction, provides a sparse, deterministic representation suitable for efficient storage and computation. For units, implies and supports inverse directional pairs (e.g., if A is east of B, then B is west of A), enabling bidirectional spatial reasoning and consistency checking.

Computational Procedure for Units

For polygonal units, directional relationships are constrained to touching neighbours to ensure semantic consistency. The computation identifies touching candidates within each directional sector and selects a primary representative using deterministic criteria. For a unit u at level , the touching candidates in directional sector d are defined as:

When , no primary neighbour is assigned for sector d, reflecting genuine boundary conditions such as coastal boundaries or geometric constraints arising from irregular unit shapes. Otherwise, a single representative is selected using lexicographic criteria that prioritize spatial significance: shared boundary length, angular alignment with sector center, centroid proximity, and stable identifiers (complete specification in the Appendix A).

This selection process yields the primary directional assignment . Additionally, multi-valued orientation relationships are established for all touching pairs: , with corresponding inverse relationships to ensure bidirectional consistency. In Figure 1, Castle ward has Cathays ward to the north, Butetown ward to the south, Adamsdown ward to the east and Pontcanna ward to the west.

Computational Procedure for Basic Places

For point-based Basic Places, directional relationships are computed using nearest-neighbour analysis within directional sectors. This approach accommodates the absence of topological adjacency for point geometries while maintaining consistency with the overall directional framework. For basic place P and directional sector d, the candidate set includes all other Basic Places within the specified sector:

When candidates exist within sector d, the nearest neighbour is selected using distance-based criteria with deterministic tie-breaking (detailed specification in Appendix A). This selection yields the primary directional assignment while ensuring reproducible results across multiple computational runs. In Figure 1, Saint David’s Centre has New Theatre to the north, Meridian to the south, Ty Admiral to the east and Tabernacle Welsh Baptist Church to the west.

3.2.4. Qualitative Proximity

(qualitative proximity) captures qualitative notions of spatial closeness that extend beyond immediate adjacency or directional orientation. QPM implements proximity through bounded reachability in spatial neighbourhood graphs, providing a topologically grounded alternative to metric distance that remains stable across different coordinate systems and scales.

Proximity for Administrative Units

For administrative units, proximity is defined through bounded path analysis in the adjacency graph formed by touching relationships. For each hierarchy level , the adjacency graph represents units as vertices () and touching relationships as edges (). Proximity is then defined as bounded reachability within this graph:

For units and hop bound (typically ):

where represents the shortest path distance in the adjacency graph. This definition ensures that proximity is irreflexive (units are not near themselves) while capturing units reachable within k adjacency steps. With , the relationship captures units that are either touching or share a common neighbour, corresponding to intuitive notions of regional proximity.

Proximity for Basic Places

Basic places, represented as points, lack the topological adjacency relationships available for polygonal units. QPM therefore defines proximity for Basic Places through two complementary approaches that accommodate different analytical requirements.

Graph-based proximity constructs a neighbourhood graph from primary directional relationships between Basic Places. For the place layer , the primary-neighbour graph has vertices and edges derived from directional primaries:

Proximity between Basic Places is then defined as bounded reachability in this graph:

Host-derived proximity provides an alternative approach that grounds basic place proximity in the underlying administrative tessellation:

where represents the base-level administrative unit containing basic place P within hierarchy h.

Computational Properties

Both proximity variants maintain essential mathematical properties supporting consistent spatial reasoning:

- Irreflexivity: Places are not proximate to themselves (enforced by )

- Symmetry: Proximity is bidirectional ()

- Monotonicity: Increasing hop bound k never reduces the proximity set

Proximity computation scales efficiently through graph-based algorithms. For administrative units, computation constructs the adjacency graph in time (where E represents touching relationships), followed by bounded breadth-first search to identify units within k hops. For Basic Places, constructing the primary-neighbour graph requires operations for directional sectors over places. Both approaches support pre-computation and caching strategies, enabling efficient proximity queries across large-scale spatial datasets.

The QPM framework can be expressed through formal ontological axioms, shown in Table 1 that enable automated reasoning and precise semantic interpretation.

Table 1.

Formal ontological axioms for QPM. These axioms ensure semantic consistency and enable automated reasoning over spatial relationships.

3.3. Multi-Hierarchy Support

Real-world spatial organization involves multiple, overlapping administrative and organizational systems that operate over the same geographic extent. QPM accommodates this complexity by supporting multiple spatial hierarchies that coexist while maintaining independent relationship structures.

3.3.1. Independent Hierarchy Management

Each hierarchy maintains its own containment and lateral relationship structures independently, ensuring that organizational differences between systems (e.g., administrative versus postal boundaries) do not create computational conflicts. Within each hierarchy , the fundamental relationships, , , and , operate according to the formal specifications defined previously, creating coherent spatial reasoning frameworks for each organizational system.

This independence is essential because different spatial hierarchies often exhibit inconsistent boundary alignments and organizational principles. Administrative boundaries may follow historical precedents, while postal boundaries optimize delivery efficiency, and electoral boundaries ensure population balance. QPM’s multi-hierarchy approach accommodates these differences without requiring artificial alignment or compromise.

3.3.2. Multi-Hierarchy Place Definition and Location Specification

Basic places can be simultaneously contained within units from multiple hierarchies, enabling rich, multi-dimensional place definitions that reflect the complexity of real-world spatial organization. This capability supports natural language descriptions that reference multiple organizational systems (e.g., “located in Castle ward, CF10 postal sector, and Cathays constituency”).

For a basic place P and hierarchy set , the complete location specification is:

This formalization captures the reality that places exist within multiple organizational contexts simultaneously. Each tuple represents the containment of place P within unit of hierarchy .

For a basic place P and hierarchy set , the complete location specification assigns P to base-level units in each hierarchy:

where denotes the base level (finest spatial resolution) of hierarchy . Higher-level containment relationships (e.g., authority, region) are derived transitively through the unit containment hierarchy rather than being directly assigned to basic places.

Computational Implementation

Multi-hierarchy place assignment is computed through iterative point-in-polygon analysis across all available hierarchies. For each basic place P:

- For each hierarchy :

- (a)

- Identify base-level units in hierarchy

- (b)

- Compute

- (c)

- If , assign containment to P

- (d)

- If , flag boundary conflict and apply tie-breaking

- Derive hierarchical containment paths for each assigned base unit

- Store complete location specification in cross-reference table

The algorithm handles edge cases including places on boundaries between hierarchies and provides deterministic assignment through geometric precedence rules.

Query and Reasoning Capabilities

The multi-hierarchy approach enables QPM to support comprehensive spatial queries that span multiple organizational systems while respecting the independence and integrity of each hierarchy’s internal structure:

- Cross-system queries: “Find all places in administrative ward X that are also in postal district Y”

- Hierarchical correspondence: “Identify electoral constituencies that overlap with postal area Z”

- Multi-dimensional place descriptions: Generate complete place descriptions spanning all relevant hierarchies

Such queries require reasoning across multiple organizational systems through the cross-hierarchy relationships and multi-hierarchy place definitions, enabling sophisticated spatial analysis that reflects real-world administrative complexity.

4. QPM Design and Implementation

This section presents the practical realization of QPM through a proof-of-concept implementation within ArcGIS Pro 3.3.1. The implementation translates the theoretical framework into operational capabilities, demonstrating that qualitative spatial reasoning can be integrated into mainstream GIS workflows while maintaining computational efficiency.

4.1. System Architecture and Processing Workflow

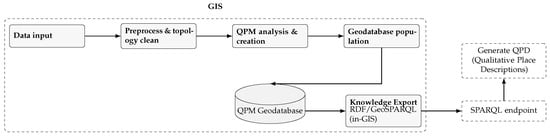

QPM operates as an integrated ArcGIS Pro toolbox, leveraging native spatial analysis and geodatabase storage for seamless GIS compatibility. Figure 3 illustrates the processing architecture transforming raw spatial datasets into queryable qualitative knowledge bases through five coordinated phases:

Figure 3.

System architecture for QPM with consolidated processing phases inside the GIS.

Data Input accommodates standard GIS formats (shapefiles, feature classes, geodatabase tables) for boundary datasets and point-based place layers. Preprocessing ensures data quality through geometry validation, boundary planarization, and stable identifier generation. QPM Analysis systematically derives spatial relationships according to formal specifications: containment () through point-in-polygon analysis, adjacency () through boundary intersection, and directional relationships (, ) through bearing analysis and sector assignment. Geodatabase Population stores relationships within a custom schema supporting both spatial geometries and qualitative relationships. Knowledge Export generates RDF/GeoSPARQL representations enabling semantic querying while maintaining native GIS accessibility.

4.2. Implementation Framework and Methodology

The implementation prioritizes algorithmic transparency and reproducibility through explicit specifications and deterministic tie-breaking. The technical framework employs Python-based libraries: ArcPy 3.3 for native GIS integration, GeoPandas for geometric computations, R-tree indexing for spatial query acceleration, and PyQt6 (python environment 3.11.8) for user interface capabilities.

QPM employs a dual-pipeline architecture processing hierarchical units (polygons) and Basic Places (points) through parallel workflows while maintaining global consistency. The administrative units pipeline computes containment through geometric inclusion, identifies boundary contacts through topological intersection, selects primary directional neighbours using deterministic tie-breaking, and derives inverse-consistent orientation relationships. The Basic Places pipeline assigns host units through point-in-polygon analysis, computes primary directional neighbours via nearest-in-sector analysis, and derives proximity through primary-neighbour graph traversal or host unit inheritance.

4.3. Geodatabase Schema and Data Management

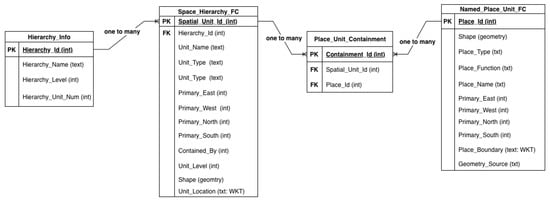

The QPM schema balances efficient spatial analysis with referential integrity across qualitative relationships. Figure 4 presents the Entity-Relationship structure organizing spatial entities and relationships.

Figure 4.

ER Diagram of the QPM geodatabase schema, illustrating primary entities, attributes, and relationships. Feature classes: Space_Hierarchy_FC (Units), Named_Place_Unit_FC (Basic Places). Tables: Place_Unit_Containment (host Unit per place), Hierarchy_Info (metadata). Per-sector primary neighbours are materialised as directional fields.

Core Schema Components

Primary spatial entities are stored in two feature classes: Space_Hierarchy_FC for administrative units (polygons) with attributes including Spatial_Unit_Id, Hierarchy_Id, Contained_By, and materialized directional fields (Primary_East_Unit_Id, etc.); and Named_Place_Unit_FC for Basic Places (points) with Place_Id, Place_Name, and corresponding directional neighbour fields. This direct storage approach enables efficient directional queries without complex join operations.

Relationship management accommodates multi-hierarchy complexity through specialized tables: Place_Containment manages cross-hierarchy place-unit relationships enabling simultaneous location within different hierarchies; Hierarchy_Info stores metadata about organizational systems including hierarchy names and depth.

The schema implements strategic denormalization for frequently accessed relationships combined with appropriate indexing for efficient geometric and relational queries, ensuring common spatial queries execute efficiently while maintaining data integrity.

4.4. Algorithms and Processing

QPM employs deterministic algorithms that transform spatial datasets into structured qualitative relationships according to formal specifications (Section 3). All algorithms follow explicit contracts specifying preconditions, processing methods, and postconditions, ensuring reproducible implementation (detailed specifications in the Appendix A).

- Containment Computation

For hierarchical partition where level forms complete tessellation, each unit in receives unique geometric parent assignment. The algorithm computes representative interior points and employs spatial indexing for efficient point-in-polygon queries, achieving performance while flagging boundary conflicts for quality assurance.

- Directional Computation

For units at the same hierarchical level, primary directional neighbours are computed in each sector while ensuring directional assertions imply topological adjacency. The algorithm groups touching neighbours by directional sector and selects primaries using lexicographic criteria: shared boundary length, angular deviation from sector mid-angle, centroid distance, and stable identifier ordering. For Basic Places, nearest-neighbour analysis within directional sectors employs distance-based selection with deterministic tie-breaking.

- Performance and Edge Cases

Spatial indexing using R-tree structures transforms geometric queries from to performance for containment and adjacency computations, enabling processing of datasets containing tens of thousands of entities. This improvement is achieved when spatial data exhibits reasonable geographic distribution and indexing parameters are optimized for the specific dataset characteristics.

As a proof-of-concept implementation, QPM demonstrates that qualitative spatial reasoning integrates into mainstream GIS workflows without requiring external semantic web infrastructure. The implementation realizes the complete theoretical framework defined in Section 3.

4.5. GIS Demonstration

This section demonstrates how QPM enables spatial analysis through dual computational paradigms. The implementation maintains full compatibility with standard ArcGIS Pro workflows while introducing qualitative spatial capabilities that complement rather than replace geometric analysis.

4.5.1. User Interface and Data Management

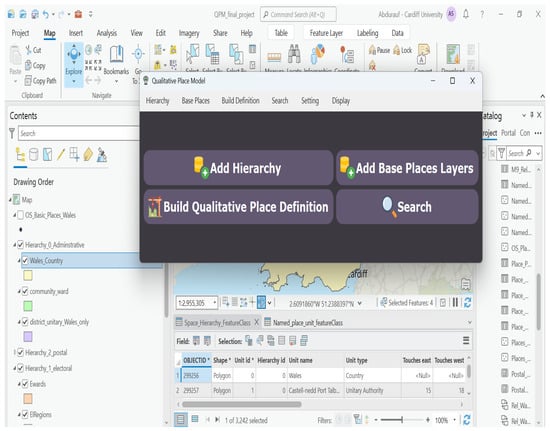

Figure 5 shows the QPM toolbox interface integrated within ArcGIS Pro. The interface provides tabs for hierarchy specification, base place configuration, model execution, and spatial querying, demonstrating seamless incorporation of qualitative spatial capabilities into standard GIS workflows. Following QPM execution, the figure illustrates the enhanced Table of Contents structure. The left panel shows original input layers (hierarchical boundaries and place points), while the right panel displays the generated QPM feature classes and relationship tables. This dual-layer organization enables parallel analysis using both geometric measurements and qualitative relationships. The QPM implementation integrates three key interface components that facilitate data quality control and operational efficiency:

Figure 5.

QPM toolbox in ArcGIS Pro after QPM population: input layers (left) and generated QPM feature classes/tables (right).

Hierarchy Manager enables systematic specification of spatial layers representing hierarchical divisions. It enforces level ordering consistency, validates naming conventions, and verifies that input datasets conform to partition properties (no gaps, overlaps, or topological errors). This validation addresses the data quality requirements discussed in Section 4.2, ensuring that relationship computation operates on topologically correct inputs.

Place Layer Manager accommodates point-based datasets through attribute field mapping, spatial reference system validation, and geodatabase schema compatibility verification. The component ensures that place layers align spatially with hierarchy boundaries and conform to the expected schema structure.

Processing Execution provides real-time operational feedback including progress indicators, automated validation reports flagging topological inconsistencies, and detailed logging of computational decisions for edge cases such as boundary places and tie-breaking scenarios. This transparency supports quality assurance and enables users to understand relationship assignment decisions.

4.5.2. Qualitative Place Description Generation

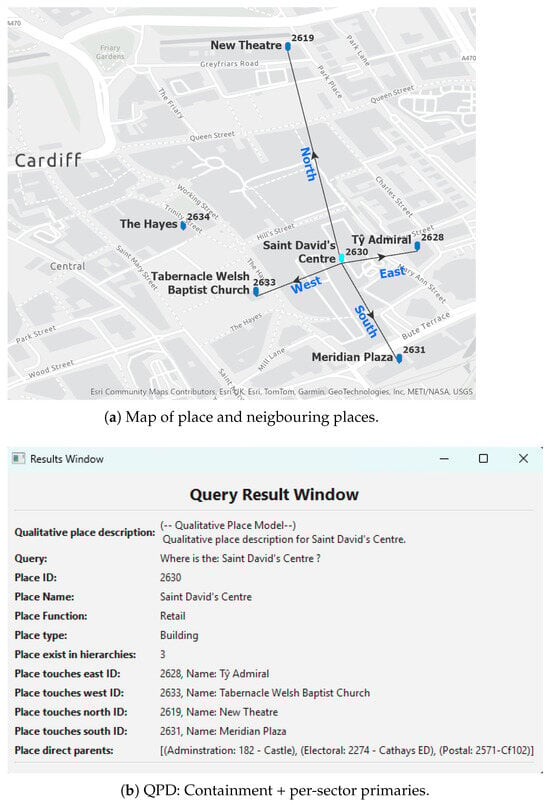

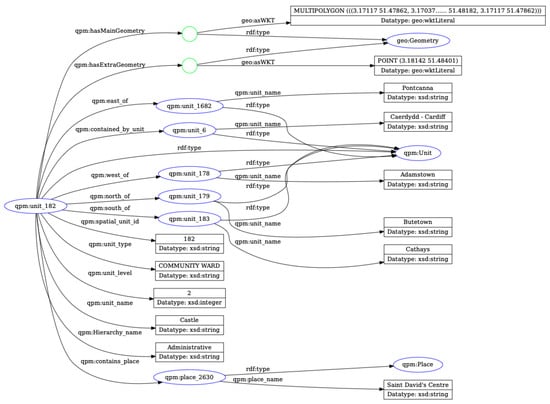

QPM generates detailed qualitative place descriptions that integrate hierarchical containment with directional neighbourhood relationships. Figure 6 presents the QPD for the place St. David’s Centre, showing multi-dimensional spatial relationships spanning multiple hierarchies and identifying primary directional neighbours within the basic place layer.

Figure 6.

QPD for St. David’s Centre; place Id: 2630.

Place-Focused Queries address the fundamental question “Where is this place?” Such queries return spatial context that unifies geometric coordinates with qualitative relationships.

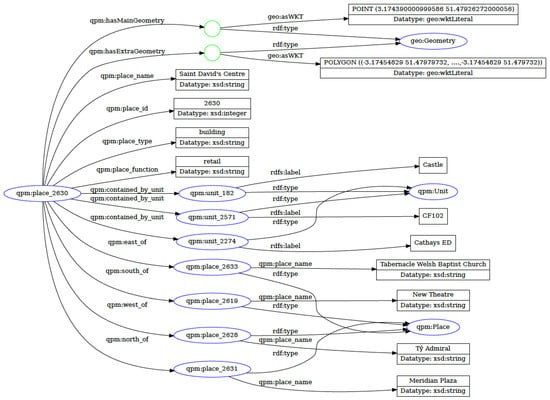

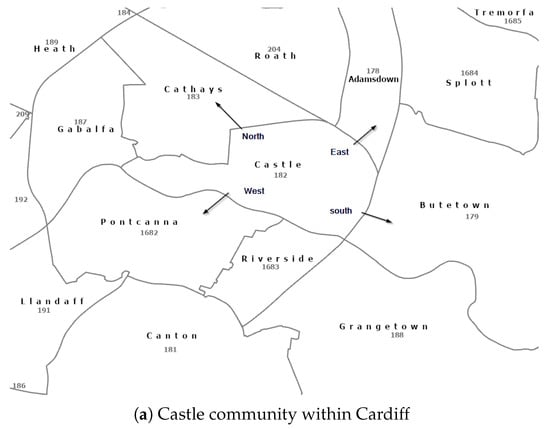

Figure 7 presents the RDF graph structure showing the complete qualitative place description for St. David’s Centre. The graph illustrates the rich relationship network emerging from systematic spatial analysis, with qualitative relationships providing substantial inferential expansion through simple logical operations (inverse relationships and transitive closure). Figure 8 and Figure 9 present analogous visualizations for an example spatial unit (Castle community ward), demonstrating that QPM’s homogeneous representation applies uniformly to both administrative units and named places.

Figure 7.

RDF graph for qpm:place_2630 (“St. David’s Centre”): geometry and QPD.

Figure 8.

Spatial units in two levels in a hierarchy.

Figure 9.

RDF graph for qpm:unit_182 (“Castle”): geometry and QPD.

Section 4.6 extends these capabilities with additional query patterns including multi-hierarchy reasoning, transitive directional composition, and proximity-based neighbourhood analysis. Section 5 provides comprehensive empirical validation across the complete experiment dataset.

4.6. Query and Reasoning Demonstration

QPM enables natural-language-style spatial queries through qualitative relationships, demonstrating capabilities that leverage the homogeneous model and logical closure to answer questions difficult to express in standard GIS environments. This section presents query patterns that showcase QPM’s reasoning capabilities: hierarchical containment traversal, directional composition through transitive closure, and proximity-based neighbourhood analysis. Each pattern illustrates computational advantages arising from pre-materialized qualitative relationships and graph-based reasoning.

4.6.1. Hierarchical Containment Queries

The fundamental “Where is X?” question retrieves complete hierarchical context across multiple organizational systems.

The example in Listing 1 finds all places within a specific administrative ward that also fall within a particular postal sector.

| Listing 1. Cross-Hierarchy Place Query. |

| PREFIX qpm: <http://qpm.ontology/2025#> |

| PREFIX rdf: <http://www.w3.org/1999/02/22-rdf-syntax-ns#> |

| SELECT ?place ?placeName ?adminUnit ?postalUnit |

| WHERE { |

| ?place rdf:type qpm:Place ; |

| qpm:place_name ?placeName ; |

| qpm:contained_by_unit ?adminUnit ; |

| qpm:contained_by_unit ?postalUnit . |

| ?adminUnit qpm:hierarchy_id "Administrative" ; |

| qpm:unit_name "Castle Ward" . |

| ?postalUnit qpm:hierarchy_id "Postal" ; |

| qpm:unit_name "CF10 1" . |

| } |

| # Returns: Castle ward, Cardiff authority, Wales (Admin) |

| # CF10 1BH, CF10 1, CF10 (Postal) |

| # Cardiff Central (Electoral) |

This query demonstrates QPM’s ability to provide comprehensive spatial context by traversing containment hierarchies. Rather than returning only “Castle ward,” the system provides the complete hierarchical path: Castle ward (community) → Cardiff (unitary authority) → Wales (country), repeated across administrative, postal, and electoral hierarchies. This multi-dimensional, multi-level response aligns with how humans naturally describe place locations.

Standard GIS Comparison

Answering “Where is St. David’s Centre?” in standard GIS requires:

- Point-in-polygon spatial queries against each hierarchy layer separately

- Manual assembly of results from multiple feature classes

- Separate geometric queries for directional relationships

- Custom scripting to format human-readable output

QPM returns this comprehensive spatial context through a single qualitative query against the unified place model, eliminating the need for multiple geometric operations and manual result correlation.

4.6.2. Directional Composition Queries

QPM’s transitive closure over directional relationships enables compositional reasoning unavailable in standard GIS. Listing 2 demonstrates two-hop directional chains:

| Listing 2. Transitive Directional Query. |

| PREFIX qpm: <http://qpm.ontology/2025#> |

| SELECT ?place ?placeName |

| WHERE { |

| ?cardiff qpm:place_name "Cardiff Castle" . |

| ?intermediate qpm:east_of ?cardiff . |

| ?place qpm:east_of ?intermediate ; |

| qpm:place_name ?placeName . |

| } |

| # Returns: Places that are east of places that are east of Cardiff Castle |

| # Demonstrates compositional reasoning over stored primary relationships |

This query finds places through compositional directional reasoning, answering ‘What places are east of places that are east of Cardiff Castle?’ QPM stores only primary directional relationships, but transitivity rules enable the computation of extended directional chains through graph traversal, eliminating runtime geometric computation. The graph-based representation enables such compositional queries by traversing pre-computed primary directional relationships, eliminating runtime geometric computation. The graph-based representation supports both bounded queries (as shown) and full transitive expansion when required.

Standard GIS Approach

Standard GIS lacks persistent directional relationships and systematic transitive reasoning. Answering this query requires:

- Compute bearing from Cardiff Castle to all places (n geometric calculations)

- Filter to eastern sector ()

- For each eastern place, repeat bearing calculations to all other places

- Filter again to eastern sector

- Manually compose results

The computational cost scales quadratically with place count (), whereas QPM answers through graph traversal of pre-computed relationships in time proportional to the number of reachable nodes.

4.6.3. Proximity-Based Neighbourhood Queries

QPM’s graph-based representation enables queries about spatial neighbourhoods beyond immediate adjacency. Listing 3 demonstrates extended neighbourhood analysis:

| Listing 3. 2-Hop Proximity Query. |

| PREFIX qpm: <http://qpm.ontology/2025#> |

| SELECT ?unit ?unitName |

| WHERE { |

| ?centralUnit qpm:unit_name "Castle Ward" . |

| ?adjacentUnit qpm:touches ?centralUnit . |

| ?unit qpm: touches ?adjacentUnit ; |

| qpm: unit_name ?unitName . |

| FILTER (?unit != ?centralUnit) |

| } |

| # Returns: Units at 1 or 2 adjacency steps of Castle Ward (extended neighbourhood) |

This query finds units in the extended neighbourhood, units that touch units that touch Castle Ward, corresponding to qualitative proximity . The query leverages stored adjacency relationships and graph traversal rather than repeated geometric intersection operations. This pattern generalizes to arbitrary proximity distances through iterative graph traversal (e.g., 3-hop neighbourhoods for ), with computational cost linear in the number of traversed edges rather than requiring geometric distance calculations for all entity pairs.

Extended neighbourhood queries support applications such as impact zone analysis (“Which administrative units fall within two degrees of separation from a focal unit?”), service area delineation, and propagation modelling. The graph-based approach scales efficiently as proximity distance increases, whereas geometric approaches require nested spatial query operations that compound computational costs.

The demonstration validates QPM’s capability to generate meaningful qualitative place descriptions that align with human spatial intuitions while maintaining computational precision and reproducibility. The system successfully bridges theoretical qualitative spatial reasoning capabilities with practical GIS implementation, providing query expressiveness comparable to semantic web knowledge graphs while maintaining compatibility with standard GIS workflows. Section 5 presents empirical validation of these capabilities across comprehensive real-world datasets.

5. Evaluation

This section presents empirical validation of the Qualitative Place Model across three fundamental objectives: uniqueness, correctness, and completeness. The evaluation demonstrates that QPM generates valid qualitative place descriptions that serve as reliable spatial identifiers while satisfying formal semantic constraints.

Table 2 provides an overview of each evaluation objective to its verification method.

Table 2.

Evaluation objectives and verification methods.

5.1. Evaluation Dataset

Evaluation employs open geospatial data from Ordnance Survey (Great Britain) covering Wales (UK). The dataset comprises three administrative hierarchies and a point-based place layer, providing heterogeneous spatial structures for comprehensive testing:

- Administrative Hierarchy: 3 levels (Wales; 22 unitary authorities; 1697 communities) ⇒ 1720 units

- Electoral Hierarchy: 3 levels (Wales; 5 Senedd regions; 769 electoral wards) ⇒ 775 units

- Postal Hierarchy: 3 levels (8 postcode areas; 205 districts; 534 sectors) ⇒ 747 units

- Basic Places (PL): 52,821 named places (e.g., St. David’s Centre, New Theatre)

Hierarchy metadata reside in Hierarchy_Info; spatial units and places in Space_Hierarchy_FC and Named_Place_Unit_FC, respectively. The evaluation dataset totals 56,063 spatial entities across varied geographic scales and organizational systems, enabling assessment of QPM’s capacity to generate qualitative descriptions for heterogeneous spatial hierarchies.

5.2. Uniqueness Verification

The objective of here is to demonstrate that QPM generates unique qualitative place descriptions, ensuring no two distinct places share identical spatial relationship patterns. Uniqueness is essential for QPDs to function as reliable spatial identifiers.

Uniqueness verification employs canonical signature comparison (Algorithm 1). For each entity X, the signature captures the complete qualitative spatial context:

where is the ordered list of container IDs per hierarchy (using stable hierarchy ordering), and is the primary neighbour ID in directional sector (or null if no neighbour exists). Two entities have identical QPDs if and only if their signatures coincide.

Algorithm Implementation

Algorithm 1 constructs a hash index mapping signatures to entity sets, enabling efficient collision detection across large datasets.

| Algorithm 1 QPD Uniqueness Verification |

| Require: Entity set S (Units at a level or Basic Places); relations contained_by, primary_*_of |

| Ensure: Collision report C (sets of entities with identical signatures) |

| 1: empty map from signature → list of entity IDs |

| 2: for each do |

| 3: ordered list of parent IDs per hierarchy (null if none) |

| 4: IDs of primary neighbours in each direction (or null) |

| 5: canonical serialization of ▹ e.g., JSON string |

| 6: |

| 7: end for |

| 8: ▹ Identify collisions |

| 9: return C |

Metrics: Collision count. Number of signature pairs where but .

Results: Zero collisions detected across all entity types. For Basic Places (n = 52,821), Administrative Units (n = 1720), Electoral Units (n = 775), and Postal Units (n = 747), Algorithm 1 confirmed complete uniqueness: every entity received a distinct qualitative signature. This validates QPM’s deterministic tie-breaking and relationship selection strategies, ensuring reproducible and unambiguous place descriptions.

5.3. Correctness Verification

The objective is to validate that generated spatial relationships satisfy formal semantic constraints defined in Section 3. Correctness ensures computational outputs conform to theoretical specifications. Correctness verification applies four constraint checks to the generated relationship graph:

- Level/Hierarchy Coherence: For unit-to-unit directional relationships, verify both entities belong to the same hierarchical level and hierarchy

- Directional–Topological Consistency: For administrative units, verify , ensuring all directional assertions imply topological adjacency

- Inverse Pair Completeness: Verify bidirectional consistency; if unit u has v as primary eastern neighbour, then v has u as western neighbour (or touching in west sector)

- Irreflexivity: Verify absence of self-loops; no entity has directional or proximity relationships to itself

Metrics: Pass/fail validation on each constraint, with violation counts if constraints are not satisfied.

Results: All correctness constraints satisfied with 100% compliance:

- Level/Hierarchy Coherence: All 12,081 stored directional relationships connect entities at the same hierarchical level within the same hierarchy (100% compliance)

- Directional–Topological Consistency: All unit-to-unit directional assertions () imply topological adjacency (touches), confirming semantic constraint (100% compliance)

- Inverse Pair Completeness: All primary directional relationships have corresponding inverse relationships in opposite sectors (100% compliance)

- Irreflexivity: Zero self-loops detected across all relationship types (100% compliance)

These results validate that QPM’s computational implementation correctly enforces the formal semantic constraints defined in the theoretical model.

5.4. Completeness Assessment

The objective is to quantify the proportion of theoretically expected relationships that QPM successfully generates and identify coverage gaps and their causes.

Completeness is assessed against the expected primaries baseline , representing the theoretical maximum:

where directional sectors (E, W, N, S), allowing at most one primary neighbour per sector per entity, plus exactly one parent containment relationship per entity (except hierarchy roots). Coverage is computed as:

Metrics: The metrics used are as follows: (1) absolute counts: generated vs. expected relationships, (2) coverage percentage per entity type and hierarchy, gap analysis: identification of missing relationship causes.

Results: Table 3 presents completeness results across all evaluated datasets:

Table 3.

Completeness assessment: generated relationships vs. expected baseline.

- Coverage Analysis

- Basic Places: 95.8% coverage (253,102 of 264,105 expected relationships)

- Administrative Units: 96.5% coverage (8295 of 8600 expected)

- Electoral Units: 94.6% coverage (3666 of 3875 expected)

- Postal Units: 89.7% coverage (3351 of 3735 expected)

- Gap Analysis

Missing relationships (4.2% to 10.3% depending on hierarchy) arise from legitimate spatial boundary effects rather than computational errors:

- Coastal boundaries: Places and units at Wales’ coastline lack neighbours in seaward directions

- National boundaries: Northernmost and southernmost entities lack neighbours beyond Wales’ extent

- Geometric constraints: Some directional sectors genuinely contain no candidate neighbours due to irregular boundary geometries

- Hierarchy boundaries: Root-level entities (e.g., Wales as top-level unit) lack parent containment relationships by definition

This pattern is consistent with the spatial structure of the test region and validates that QPM correctly identifies the absence of relationships rather than incorrectly generating spurious ones.

5.5. Inferential Expansion Analysis

Beyond validating correctness and completeness of stored relationships, we assess QPM’s inferential power, the capacity to derive extensive spatial knowledge from minimal stored facts through logical inference. This analysis demonstrates computational efficiency while maintaining expressive reasoning capabilities.

5.5.1. Method

For each hierarchy, we compute:

- Stored edges: Explicitly asserted directional and containment relationships

- Inverse edges: Symmetric relationships generated by predicate inversion (e.g., )

- Transitive edges: Extended relationships computed via per-predicate transitive closure

- Full closure: De-duplicated union of stored, inverse, and transitive edges

- Expansion ratio: Full/Stored, quantifying inferential amplification

5.5.2. Results

Table 4, Table 5 and Table 6 present detailed inference expansion for each administrative hierarchy. Table 7 summarizes storage efficiency across hierarchies.

Table 4.

Administrative hierarchy: stored vs. inferred sizes per predicate. “Full” is the de-duplicated union of stored, inverse, and per-predicate transitive edges.

Table 5.

Postal hierarchy: stored vs. inferred sizes per predicate. “Full” is the de-duplicated union of stored, inverse, and per-predicate transitive edges.

Table 6.

Electoral hierarchy: stored vs. inferred sizes per predicate. “Full” is the de-duplicated union of stored, inverse, and per-predicate transitive edges.

Table 7.

Inferential expansion summary: share of stored edges within full directional closure.

Key Findings

Aggregating across administrative, postal, and electoral hierarchies, directional relations expand from 12,081 stored edges to 152,995 inferred edges, a 12.66× expansion with only 7.9% storage overhead. Containment relationships expand from 3232 to 9464 edges (2.93× expansion), yielding an overall system expansion of 10.6× from stored to fully inferred representations.

This expansion occurs through two complementary inference mechanisms: (i) predicate inverses generating symmetric relationships, and (ii) per-predicate monotone transitivity extending chains of directional relationships. The substantial expansion demonstrates that QPM’s sparse storage strategy does not compromise inferential capability, rather, it enables rich qualitative reasoning from a compact, easily validated foundational representation.

6. Discussion

The empirical evaluation validates QPM’s core capabilities while revealing insights about GIS-native qualitative spatial reasoning. This section interprets the evaluation findings, examines their implications for spatial data science, and considers QPM’s positioning within the broader landscape of qualitative spatial representation.

6.1. Interpretation of Evaluation Findings

The evaluation results illuminate fundamental aspects of qualitative place representation. The achievement of 100% uniqueness demonstrates that sparse, deterministic relationships suffice to distinguish places within complex spatial systems, challenging assumptions that unique descriptions require exhaustive geometric detail or comprehensive relationship networks. QPM’s selective primary relationships provide sufficient discriminative power while maintaining computational tractability.

Perfect correctness compliance confirms that geometric computation can reliably materialize qualitative relationships satisfying formal spatial calculi, demonstrating that “naïve geography” advocated by qualitative spatial reasoning theory can be operationalized within standard GIS without compromising formal rigour.

The completeness results (89.7–96.5%) reveal an important distinction between computational limitations and legitimate spatial structure: missing relationships occur at geographic boundaries (coastal edges, national borders, hierarchy roots) where absence reflects spatial reality rather than algorithmic failure.

Finally, the 12.66× inferential expansion quantifies a fundamental trade-off: sparse local storage enables substantial inferential reach through sound logical closure, achieving knowledge graph-style reasoning power while maintaining GIS-native capabilities.

6.2. Implications for GIS-Native Qualitative Reasoning

QPM’s implementation demonstrates that qualitative spatial reasoning need not remain external to operational GIS environments. Three design principles emerge as critical for GIS-native qualitative models: (i) homogeneous place representation, treating administrative units and named places uniformly to enable cross-boundary queries without schema impedance; (ii) strategic relationship sparsification, storing only primary relationships while recovering extensive knowledge through logical inference; and (iii) direct geometric derivation from authoritative boundary datasets, ensuring alignment between qualitative and quantitative representations essential for regulatory compliance and workflow integration.

6.3. Positioning Within the Qualitative Spatial Reasoning Landscape

QPM occupies a distinctive position bridging theoretical qualitative spatial reasoning and operational GIS practice. Compared to semantic web approaches (LinkedGeoData, GeoSPARQL, KnowWhereGraph), QPM trades comprehensive ontological reasoning for direct GIS integration and geometric grounding. While semantic web platforms offer richer inferential capabilities through RDFS/OWL reasoning, they operate external to GIS workflows, requiring data export/import cycles that disrupt integrated analysis.

Relative to place graph approaches, QPM emphasizes formal semantic constraints over exploratory relationship discovery. Where place graphs excel at capturing emergent spatial relationships from natural language or volunteered geographic information, QPM provides deterministic, reproducible qualitative descriptions derived systematically from authoritative spatial partitions.

QPM’s unique contribution lies in demonstrating that qualitative spatial reasoning can be fully integrated within standard GIS platforms while maintaining theoretical rigour. The framework shows that cognitive alignment and computational efficiency need not be competing objectives, but rather, strategic design choices enable both simultaneously.

6.4. Limitations and Generalization Potential

Several limitations constrain QPM’s current scope. The deterministic tie-breaking approach, while ensuring reproducibility, may not always align with human spatial intuitions when multiple equally plausible neighbours exist. The fixed cardinal/ordinal directional sectors provide consistent but potentially coarse directional resolution for applications requiring finer-grained orientation distinctions.

Platform dependency on ArcGIS Pro limits accessibility, though QPM’s conceptual framework and algorithms translate directly to open-source alternatives (PostGIS/GEOS, QGIS). The primary porting challenge involves reproducing ArcGIS Pro’s toolbox interface within QGIS’s plugin architecture, while computational kernels map directly to equivalent geometric operations. Future work will develop QGIS/PostGIS implementations to validate platform-independence and expand accessibility.

Dependence on authoritative boundary datasets constrains application to regions with maintained administrative geographies. Where such partitions are unavailable, Discrete Global Grid Systems (DGGS) offer potential universal hierarchical substrates, though integration with irregular political boundaries requires investigation.

The current implementation lacks incremental update mechanisms, requiring full recomputation when spatial boundaries or place locations change. For operational systems with dynamic spatial data, developing differential update algorithms represents an important optimization priority.

7. Conclusions

7.1. Summary and Contributions

This research addressed whether qualitative place models can be implemented natively within GIS platforms while maintaining both theoretical rigour and computational efficiency. We presented the Qualitative Place Model (QPM), a GIS-native framework that transforms standard boundary datasets into structured Qualitative Place Descriptions (QPDs) through four fundamental spatial relationships: hierarchical containment, topological adjacency, directional orientation, and proximity.

Empirical validation across Wales (UK) datasets demonstrated that QPM generates unique (100%), correct (100%), and substantially complete (89.7–96.5%) qualitative descriptions for 56,063 spatial entities. Stored relationships expand 12.66-fold through logical inference, demonstrating substantial reasoning capabilities from compact representations.

This work advances qualitative spatial reasoning and GIS practice through four principal contributions:

GIS-native qualitative spatial reasoning. QPM demonstrates that theoretically rigorous qualitative models can be fully integrated within mainstream GIS platforms, implementing end-to-end processing entirely within the GIS environment and eliminating adoption barriers.

Homogeneous place representation. The uniform treatment of polygonal units and point-based places resolves fundamental impedance mismatches in spatial data models, enabling queries spanning organizational boundaries without schema translation.

Compact storage with rich inference. The 12.66× expansion from stored to inferred relationships demonstrates that knowledge graph-style reasoning is achievable within GIS-native representations without comprehensive relationship materialization.

Validated uniqueness and correctness. Complete validation confirms that deterministic qualitative relationships provide sufficient discriminative power to distinguish every place within complex spatial hierarchies, reliably bridging coordinate-based processing and symbolic reasoning.

7.2. Implications and Impact

QPM enables spatial analysts to express queries aligned with natural human reasoning: “Where is X?” returns complete hierarchical contexts; “Which places are north of Y?” leverages pre-computed relationships; and cross-hierarchy queries execute efficiently through unified representations. These capabilities extend GIS applicability to scenarios where qualitative spatial facts are meaningful despite unavailable precise coordinates, emergency response, urban planning, and multi-jurisdictional policy analysis all benefit from descriptions matching natural spatial discourse.

For qualitative spatial reasoning research, QPM demonstrates that theoretical calculi can be operationalized at scale, showing cognitive alignment and computational efficiency as compatible objectives. For GIS research, the framework illustrates how qualitative semantics expand analytical capabilities without sacrificing quantitative precision, providing a template for bridging human-centric and machine-centric spatial representations.

7.3. Future Directions

Several extensions would enhance QPM’s capabilities: (i) cross-predicate composition rules (e.g., ) enabling richer inferences; (ii) incremental update mechanisms for dynamic spatial data; (iii) open-source implementations (PostGIS/QGIS) validating platform independence; and (iv) cognitive validation studies assessing alignment with human spatial intuitions.

QPM bridges the gap between theoretical spatial reasoning and practical GIS implementation, demonstrating that qualitative reasoning can integrate into mainstream GIS without sacrificing efficiency. By augmenting geometric representations with explainable qualitative semantics, QPM enhances how analysts interact with geographic information, which is essential as spatial analysis becomes central to decision-making across diverse domains.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/ijgi14120474/s1.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Alia I. Abdelmoty; methodology, Alia I. Abdelmoty and Abdurauf Satoti; software, Abdurauf Satoti; validation, Alia I. Abdelmoty and Abdurauf Satoti; formal analysis, Alia I. Abdelmoty and Abdurauf Satoti; investigation, Alia I. Abdelmoty and Abdurauf Satoti; resources, Abdurauf Satoti; data curation, Abdurauf Satoti; writing—original draft preparation, Abdurauf Satoti and Alia I. Abdelmoty; writing—review and editing, Alia I. Abdelmoty; visualization, Abdurauf Satoti; supervision, Alia I. Abdelmoty. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The data analysed in this study are publicly available through the Ordnance Survey web site: https://osdatahub.os.uk/downloads/open/OpenMapLocal (accessed on 26 November 2025). Sample datasets, SPARQL queries, resulting RDF graphs, and complete algorithmic pseudocode produced by the GIS are available at GITHUB (Version 2.52.0) repo.

Acknowledgments

The authors utilized Anthropic’s Claude Sonnet 4 and OpenAI’s ChatGPT (GPT-5) for language editing and proofreading assistance. These tools were employed solely to enhance the readability of the manuscript; all intellectual content, analyses, and conclusions are the authors’ original work.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Algorithm Specifications

This appendix provides algorithmic specifications for computing Qualitative Place Descriptions. Each algorithm is defined by explicit contracts specifying preconditions, methods, and postconditions. Complete pseudocode implementations are available in the Supplementary Material and the accompanying GitHub repository.

Appendix A.1. Core Algorithms

Algorithm S1: Containment for Spatial Units. Precondition: Level forms a gap-free, overlap-free partition; point-in-polygon queries available. Method: For each unit , compute interior point and find unique containing parent in . Postcondition: Each unit assigned to exactly one parent; boundary conflicts flagged. Complexity: per level with spatial indexing.

Algorithm S2: Directional Relationships for Spatial Units. Precondition: Clean polygons at level ; adjacency predicate and directional sector function available. Method: For each unit, identify touching neighbours, group by directional sector, select primary neighbour per sector using lexicographic tie-breaking. Postcondition: At most one neighbour per sector; directional relationships imply adjacency. Complexity: worst case, with spatial indexing.

Algorithm S3: Host Assignment for Basic Places. Precondition: Basic Places as points; base-level units as polygons. Method: Assign each Basic Place to containing unit using point-in-polygon analysis. Postcondition: Each Basic Place assigned to exactly one host unit. Complexity: with spatial indexing.

Algorithm S4: Directional Relationships for Basic Places. Precondition: Basic Places with assigned host units; distance function and directional sectors defined. Method: For each Basic Place and sector, identify nearest place in that sector. Postcondition: At most one primary neighbour per sector. Complexity: worst case, optimizable with spatial partitioning.

Appendix A.2. Deterministic Tie-Breaking

QPM employs lexicographic tie-breaking to ensure reproducible relationship selection:

For Units: (1) maximum shared boundary length, (2) minimum angular deviation from sector center, (3) minimum centroid distance, (4) lexicographic identifier.

For Places: (1) minimum distance, (2) lexicographic identifier.

For Boundary Conflicts: (1) largest containment area, (2) centroid proximity, (3) identifier precedence. Multi-hierarchy assignments are computed independently per hierarchy.

All algorithms benefit from R-tree spatial indexing and support parallelization at the entity level.

References

- Agnew, J. Space and place. Handb. Geogr. Knowl. 2011, 2011, 316–331. [Google Scholar]

- Hamzei, E.; Winter, S.; Tomko, M. Place facets: A systematic literature review. Spat. Cogn. Comput. 2020, 20, 33–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winter, S.; Baldwin, T.; Cavedon, L.; Stirling, L.; Kealy, A.; Duckham, M.; Rajabifard, A.; Richter, K.; Richter, D. Starting to talk about place. In Proceedings of the Surveying and Spatial Sciences Biennial Conference 2011, Wellington, New Zealand, 21–25 November 2011; pp. 63–73. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, H.; Vasardani, M.; Winter, S.; Tomko, M. A graph database model for knowledge extracted from place descriptions. Isprs Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2018, 7, 221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Richter, D.; Winter, S.; Richter, K.F.; Stirling, L. Granularity of locations referred to by place descriptions. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2013, 41, 88–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freundschuh, S.; Kitchen, R. Cognitive Mapping: Current Theory and Practice; Professional Geographer; Routledge: Abingdon, UK, 2001. [Google Scholar]

- Aronoff, S. Geographic information systems: A management perspective. Geocarto Int. 1989, 4, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jones, L. Geographic information systems. In Essentials of Environmental Epidemiology for Health Protection: A Handbook for Field Professionals; OUP Oxford: Oxford, UK, 2012; p. 121. [Google Scholar]

- Purves, R.S.; Winter, S.; Kuhn, W. Places in Information Science. J. Assoc. Inf. Sci. Technol. 2019, 70, 1173–1182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hart, G.; Dolbear, C. Linked Data: A Geographic Perspective; Taylor & Francis: Abingdon, UK, 2013. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelmoty, A.I.; Satoti, A. A Homogeneous Approach to Reasoning Over Global Geographic Data. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Innovative Techniques and Applications of Artificial Intelligence, Cambridge, UK, 17–19 December 2024; pp. 285–298. [Google Scholar]

- Cohn, A.G.; Bennett, B.; Gooday, J.; Gotts, N.M. Qualitative spatial representation and reasoning with the region connection calculus. Geoinformatica 1997, 1, 275–316. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Egenhofer, M.J.; Mark, D.M. Naive geography. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Spatial Information Theory, Semmering, Austria, 21–23 September 1995; pp. 1–15. [Google Scholar]

- Egenhofer, M.J.; Franzosa, R.D. Point-set topological spatial relations. Int. J. Geogr. Inf. Syst. 1991, 5, 161–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Freksa, C. Using orientation information for qualitative spatial reasoning. In Theories and Methods of Spatio-Temporal Reasoning in Geographic Space; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 1992; pp. 162–178. [Google Scholar]

- Vasardani, M.; Timpf, S.; Winter, S.; Tomko, M. From descriptions to depictions: A conceptual framework. In Proceedings of the Spatial Information Theory: 11th International Conference, COSIT 2013, Scarborough, UK, 2–6 September 2013; Proceedings 11. Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 299–319. [Google Scholar]

- Hamzei, E.; Chen, H.; Vasardani, M.; Tomko, M.; Winter, S. Deriving place graphs from spatial databases. Res. Locate 2018, 2087, 25–32. [Google Scholar]

- Abdelmoty, A.I.; Al-Muzaini, K.O. A computational model of place on the linked data web. Int. J. Adv. Softw. 2016, 9, 238–247. [Google Scholar]

- Goodwin, J. Experiences of Using OWL at the Ordnance Survey. In Proceedings of the OWLED, Galway, Ireland, 11–12 November 2005; Volume 188. [Google Scholar]

- Janowicz, K.; Hitzler, P.; Li, W.; Rehberger, D.; Schildhauer, M.; Zhu, R.; Shimizu, C.; Fisher, C.K.; Cai, L.; Mai, G.; et al. Know, Know Where, Know Where Graph: A densely connected, cross-domain knowledge graph and geo-enrichment service stack for applications in environmental intelligence. AI Mag. 2022, 43, 30–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- KnowWhereGraph. About KnowWhereGraph Geo_enrichment. 2025. Available online: https://knowwheregraph.org/about/ (accessed on 23 January 2025).

- Longley, P.A.; Goodchild, M.F.; Maguire, D.J.; Rhind, D.W. Geographic Information Science and Systems; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2015. [Google Scholar]

- Al-Muzaini, K.O. Qualitative Modelling of Place Location on the Linked Data Web and GIS. Ph.D. Thesis, Cardiff University, Cardiff, UK, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- Giordano, A.; Cole, T. The limits of GIS: Towards a GIS of place. Trans. GIS 2018, 22, 664–676. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, M.E.; Swanlund, D.; Schuurman, N. Problems with quantitative categorization: An argument for qualitative approaches. Environ. Plan. F 2023, 2, 331–349. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).