Abstract

Urban heritage, when enhanced by digital technologies, can become a living laboratory. This study explores the Art Nouveau Path, a mobile augmented reality game implemented in Aveiro, Portugal, as part of the EduCITY Digital Teaching and Learning Ecosystem. Designed as a circular path of eight georeferenced points of interest, it integrates narrative cartography, multimodal media, and sustainability competences framed by GreenComp, the European Sustainability Framework. A DBR approach guided the study, combining four interconnected datasets: the game’s structured curriculum review by 3 subject specialists (T1-R), gameplay logs from 118 student groups (4248 responses), post-game reflections from 439 students (S2-POST), and in-field observations from 24 teachers (T2-OBS). Descriptive statistics and thematic coding were triangulated to examine attention to architectural details, the mediational role of AR, spatial trajectories, and reflections about sustainability. The results present overall accuracy (85.33%), with particularly strong performance on video items (93.64%), stable outcomes on AR tasks (85.52%), and lower accuracy in denser urban contexts. Qualitative data highlight AR as a catalyst for perceiving hidden features, collaboration, and connecting heritage with sustainability. The study concludes that location-based AR games can generate semantically enriched geoinformation. They also act as cartographic interfaces that embed narrative and competence-oriented learning into urban heritage contexts.

1. Introduction

Urban heritage today is understood not only as cultural memory but also as a dynamic layer of smart cities, functioning as a living dataset that informs planning, education, and civic engagement [1]. This perspective has gained prominence in international frameworks such as the Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs), where Target 11.4 of Goal 11 states the need to ‘strengthen efforts to protect and safeguard the world’s cultural and natural heritage’ [2], highlighting the safeguarding of cultural and natural heritage as a pillar of sustainable urban development [3]. This positions heritage within broader sustainability and resilience agendas.

At the technological level, advances in Geographic Information Systems (GIS), Building Information Modeling (BIM), and location-based services (LBS) have expanded the capacity to represent, analyze, and communicate urban environments [4]. More recently, Spatial Data Science approaches have refined methods for interpreting movement, combining statistical and computational techniques with geoinformation workflows [5,6]. In parallel, augmented reality (AR) and Extended Reality (XR) have transformed geovisualization, enabling digital overlays that situate interpretation and interaction directly in the urban fabric [7,8,9]. In AR-GIS, quaternion-based pipelines for pose estimation and 2D/3D vector rendering help stabilize registration and enable real-time alignment of vector and raster layers with physical space, particularly in mobile environments. These technical advances support our interpretation of AR as a cartographic interface that merges on-site spatial storytelling with georeferenced data visualization [10,11,12].

However, significant gaps can be identified. Analyses of trajectories still rely predominantly on Global Positioning System (GPS) traces or sensor data that, while precise, are often noisy and lack interpretative depth [13]. Efforts to enrich mobility data semantically have shown promise, particularly in cultural contexts where meaning is inseparable from space [14]. At the same time, research on narrative cartography has underlined how mapping itself can become a medium for storytelling and cultural interpretation [15,16]. Even so, the integration of semantics, narrative, and trajectory analysis within AR-based cartography remains underdeveloped. Recent proposals for semantic logging of user interactions in cultural spaces suggest a possible way forward, but their application in heritage and education contexts remains limited [17].

Mobile augmented reality games (MARGs) offer a promising framework to bridge these domains. Their design is grounded in fixed trajectories, which constitute deliberate cartographic decisions and allow for comparability across groups. Through multimodal overlays, they transform static maps into dynamic interfaces, embedding meaning and narrative into place. When enriched semantically, points of interest (POIs) can be aligned with competence-based frameworks such as GreenComp, the European sustainability competence framework [18]. This alignment connects cultural heritage to global agendas like SDG 11 and SDG 4.7 [2] and has been noted as an underexplored dimension in recent reviews of AR in heritage communication and education [19,20].

This study aims to explore the identified gaps through the Art Nouveau Path, a MARG implemented in Aveiro, Portugal. The MARG establishes a path around eight georeferenced POIs in the city of Aveiro’s Art Nouveau old neighborhood, combining multimodal media, such as old photographs, AR, videos, and audio, together with narrative storytelling, aimed to create a layered geoinformation environment. The Art Nouveau Path is anchored in the EduCITY Digital Teaching and Learning Ecosystem (DTLE) (https://educity.web.ua.pt/) (accessed on 14 September 2025). As an educational product, this MARG is played on the EduCITY app (version 1.3).

Aveiro’s Art Nouveau built heritage offers a productive lens for sustainability education because its aesthetics and techniques in the region were tightly coupled with local ecologies, architects, artisans, and crafts. Motifs derived from local flora and fauna, reliance on local materials such as adobe and ceramic tiles, and the historical tension between conservation and modernization allow this MARG to stage concrete trade-offs that connect place and context with GreenComp dimensions such as ‘valuing sustainability’, ‘embracing complexity’, ‘futures literacy’, and ‘acting for sustainability’ [18]. Grounding sustainability in this heritage theme also aligns with SDG 11.4 by making the safeguarding of cultural heritage itself an object of inquiry and collective action.

Its implementation with students originated several datasets, including gameplay logs from 118 student groups, qualitative answers from 439 student follow-up questionnaires (S2-POST), 24 in-field teacher observations (T2-OBS), and curricular validation feedback from 3 teachers (T1-R). The remaining datasets were already present in previous works [21,22].

By considering the Art Nouveau Path as an urban laboratory, this study examines how location-based AR games can produce interpretable geoinformation while operating as cartographic interfaces that enhance the semantic and narrative depth of heritage landscapes [21,22].

Accordingly, the study is guided by two research questions (RQ): RQ1. ‘How can location-based AR games contribute to the production and analysis of geoinformation in urban heritage contexts?’, and RQ2. ‘In what ways can AR function as a cartographic interface that enriches spatial storytelling and semantic representation of cultural heritage?’.

This work is structured in six sections. Following the Introduction, Section 2 presents a thematic literature review organized into four pillars: (i) LBS and trajectory analysis; (ii) AR and cartographic geovisualization; (iii) semantic frameworks and narrative cartography; and (iv) urban informatics and smart heritage. Section 3 details the methodological design, the study context, and the procedures for participants, data collection, and analysis. Section 4 reports the findings from the implementation of the Art Nouveau Path, followed in Section 5 by a discussion that cross-references these results with the research questions and the thematic review. Finally, Section 6 concludes by summarizing the main findings, outlining their implications for the integration of GIS, BIM, knowledge graphs, and Geospatial Artificial Intelligence (GeoAI) in future smart heritage initiatives and presenting the study’s limitations alongside paths for future research.

2. Related Work

Given the interdisciplinary scope of this study, spanning LBS, AR, trajectory analysis, semantic frameworks, and smart heritage, a narrative thematic literature review was adopted [23,24,25]. This approach is particularly suited to synthesizing heterogeneous evidence across adjacent research domains, provided that selection and synthesis procedures are transparent and rigorous.

Searches were conducted in Scopus and Web of Science from July to August 2025, covering the period 1997 to 2025. The year of 1997 was chosen aiming to capture early web mapping and mobile geotechnology precursors that seeded LBS and trajectory analytics relevant to AR-supported cultural heritage mapping. Keyword families reflected the four target domains and were combined with Boolean operators to capture interdisciplinary intersections: location-based services AND heritage AND education; augmented reality AND cultural heritage AND learning; semantic trajectory AND cultural heritage; narrative cartography AND mapping; smart heritage AND sustainability; and, GreenComp AND education. This review was also informed by previous literature research and prior work. The database search retrieved 64 records. Following the screening of abstracts and the removal of duplicates, 24 items were retained for full-text review. The usage of the inclusion criteria (peer-reviewed, English-language, explicit relevance to at least one of the four domains, and connection to education, cartography, mapping, location-based, sustainability, or heritage) resulted in the final peer-reviewed corpus comprising 43 articles. After revision, four peer-reviewed papers were added to the corpus, aiming to ensure theoretical enhancement. To ensure conceptual breadth, the articles were complemented with six policy and institutional frameworks, nine books and monographs, and three prior research outputs by the authors. Non-peer-reviewed sources were not captured via database searches but were selected from previous research and authoritative references in the context of Aveiro, heritage, geoinformation, and sustainability. Exclusion criteria were systematically applied. Most of the excluded works were of a tourism- or marketing-oriented nature, with a focus on virtual reality (VR) rather than AR or addressed museum learning without geoinformation or trajectory. The final corpus thus comprised 65 sources, which were structured into four categories (see Appendix A).

Analysis followed a hybrid thematic strategy, combining deductive coding guided by the five domains with inductive exploration of emergent patterns [26]. This ensured both conceptual coherence and openness to novel intersections, providing the foundation for the four thematic subsections that follow.

2.1. Geoinformation and Location-Based Services

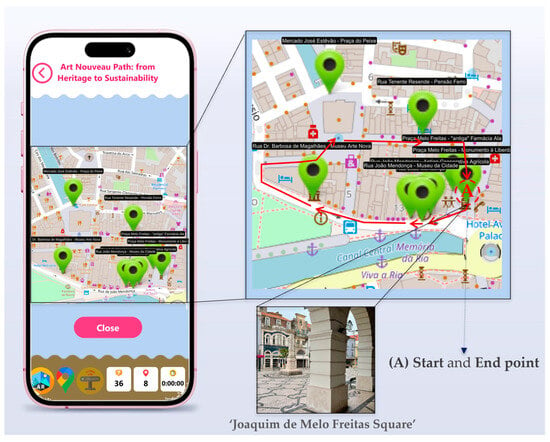

Geographic Information Science (GIScience) and location-based services (LBS) provide the geotechnological foundation for location-aware educational applications. GIScience has evolved beyond static mapping to incorporate dynamic spatial processes and user-centered perspectives [4]. This evolution reflects a shift from viewing maps purely as representations of form toward understanding the processes and interactions they signify in the real world [4]. Modern mobile devices are equipped with GPS and sensors that enable LBS applications that deliver content or functionality tailored to a user’s geographic location in real-time. LBS have proliferated across smart cities, allowing citizens to serve as “sensors” contributing georeferenced information and experiences [27]. In the education context, this means the city itself can become an interactive learning environment. By marrying geospatial data with pedagogical narratives, location-based educational games turn urban landscapes into “smart” learning spaces where contextually relevant content enhances engagement. For example, smartphone-guided heritage tours exemplify how LBS can foster dynamic tourism experiences, linking cultural information to specific sites and moments [28,29]. Such location-driven experiences leverage real-world exploration, aligning with the concept of ‘lifelong and lifewide learning’ [30,31] in a smart city, learning that occurs across one’s lifespan and in diverse informal settings [32]. The rise of urban informatics and smart city initiatives further highlights the potential of geoinformation technologies to personalize and enrich user experiences in situ. Within this project’s scope, geoinformation and LBS enable the adaptive delivery of content based on where learners are, situating educational challenges and narratives in the physical Art Nouveau heritage sites of the city of Aveiro. This geolocation-responsive design is fundamental to engaging users in a pervasive learning experience that connects virtual or augmented information to real-world context [21]. Figure 1 presents the MARG in-app game.

Figure 1.

Art Nouveau Path map in the EduCITY app (version 1.3): in-game screenshot, and the start and ending point.

Beyond basic mapping, LBS in educational games rely on robust geospatial data infrastructures and real-time positioning. Accuracy and interactivity in these systems draw on advances in spatial data handling and user interface design. Research in spatial data science underlines the importance of integrating heterogeneous geographic datasets, like maps, sensor readings, and user-contributed data, to support sustainable mobility and location-aware decision making [5]. These advances ensure that location-based apps can provide timely, precise feedback to users navigating in real-world settings. Moreover, the participatory aspect of LBS aligns with the trend of ‘volunteered geographic information’, wherein users actively contribute location-tagged content (knowingly or unknowingly) that can enhance the collective knowledge of places [27].

In summary, the convergence of GIScience and LBS has laid the groundwork for MARGs like the Art Nouveau Path, which require both the technical capacity to pinpoint users in an urban setting and the conceptual approach of treating the city as an interactive, pedagogical canvas. Geoinformation technologies not only map where learning takes place but also help shape how learning takes place by linking location to relevant information and tasks. By achieving this, this approach can foster the development of concepts like identity and memory [33,34], supporting the notion of space as a common value [35].

2.2. Trajectory Analysis and Spatial Semantics

The Art Nouveau Path project involves users moving through the city, creating spatio-temporal trajectories that carry implicit information about their learning journey. Understanding and analyzing the data from this movement pattern is crucial for evaluating engagement and guiding users through meaningful paths. Although the route on the Art Nouveau Path is the same for each user, trajectory analysis techniques from GIScience and urban computing provide methods to collect, interpret, and visualize data (game logs) from users [13]. Such techniques include recording GPS tracks or check-in sequences (as in this study) and then applying computational methods to identify significant patterns or differences in how individuals or groups navigate the common space. For instance, sequence alignment methods have been adapted from bioinformatics to compare human activity paths, revealing common paths or visitation orders among participants [36]. Visual analytics of movement data offers further means to uncover trends, as large volumes of tracking data can be interactively explored for patterns like frequently visited sites, time spent, or preferred transitions [37]. In this study, the automated logs did not encode paths or dwell times, so the analyses are focused on item-level completion and accuracy across POIs and coarse pacing proxies derived from timestamps.

By leveraging these approaches, this project can assess which Art Nouveau landmarks attract more attention (by answering accuracy) or which parts of the game might cause delay or confusion (observed by teachers at T2-OBS), thereby informing iterative design improvements. Recent data-driven movement analysis frameworks emphasize combining quantitative trajectory metrics with qualitative insights, acknowledging that human mobility data can be mined for actionable knowledge about behavior in space [6]. In an educational urban game, such analysis might reveal learning “hotspots”, locations where users show high engagement, or identify if certain narrative segments encourage users to take exploratory detours versus directed paths.

A distinctive aspect of trajectory analysis in cultural heritage education is the incorporation of spatial semantics, the meanings and contextual information associated with locations and paths. Rather than treating a user’s path as a mere sequence of coordinates, semantic trajectory analytics enrich these paths with information about the places and events encountered [14]. In practice, this could involve linking each POI on a user’s journey to a knowledge base or category, like identifying a site as an Art Nouveau museum, a private house, or an urban garden, and what thematic history it represents.

By interpreting movement data with semantic tags, it becomes possible to understand not just the users’ paths but also why they matter. Angelis et al. [14] demonstrate that in cultural spaces, combining trajectory data with semantic information, as exhibit themes or historical context, enables more powerful analyses and even recommender systems. For example, in the Art Nouveau Path, the suggestion of points of interest and paths was induced by previous MARG validation [22], combining curricular knowledge with development of sustainability competencies [21,22]. This semantic enrichment of spatial data often relies on ontologies and linked data. In our context, aligning with standards such as the International Committee for Documentation of the International Council of Museums Conceptual Reference Model (CIDOC-CRM) [38] helps ensure that heritage locations, events, and story elements can be represented in an interoperable way. While the present study does not formally implement the model, its categories can be mapped conceptually to CIDOC-CRM classes and properties, which would enable connecting user trajectories to broader cultural knowledge graphs.

Overall, analysis combined with spatial semantics and storytelling narrative provides a dual quantitative–qualitative lens: it reflects movement and engagement patterns while also collecting data via gaming logs, interpreting the cultural meaning of paths. This is central for this study, which is on the intersection of geography, education, sustainable development, and heritage, enabling a deeper understanding of how users experience urban space and future data-driven refinement of the MARG.

2.3. Augmented Reality as a Cartographic Interface

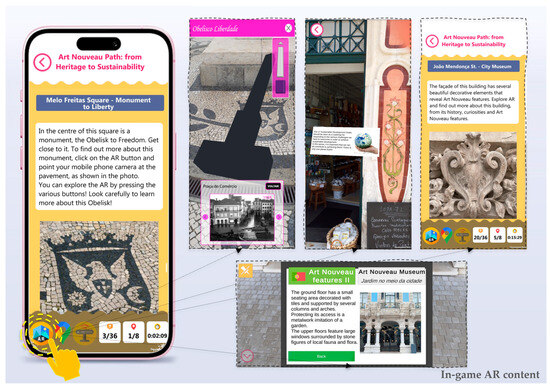

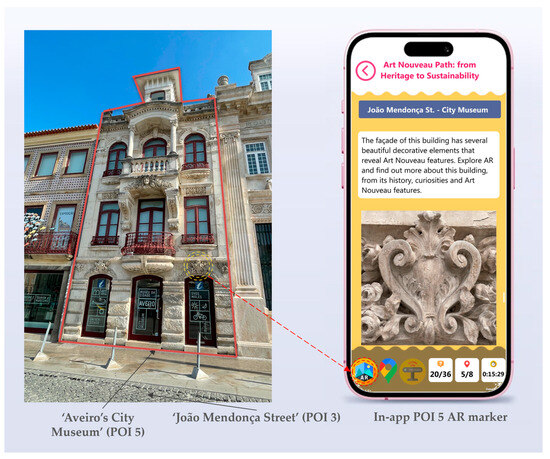

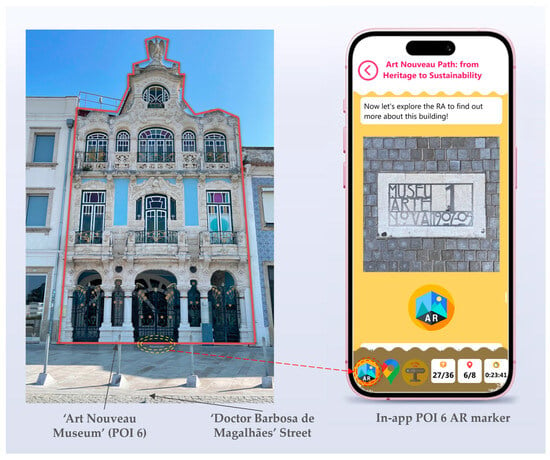

AR offers a powerful medium to overlay digital information onto the physical world, effectively acting as a live cartographic interface for users. In an AR-based heritage game, the city map is no longer confined to paper or screen; it is experienced directly through the camera view, with virtual elements anchored to real locations. Figure 2 presents the interaction between real-world and AR content.

Figure 2.

Examples of in-app Aveiro’s Art Nouveau heritage used as AR markers and its contents. This allows for an engaging interface between real-world and AR content [22].

AR’s educational benefits are well documented, particularly its ability to provide immersive, context-rich learning experiences [39]. By overlaying historical images, 3D models, or interactive clues onto buildings and streets, AR facilitates learners to visualize spatial relationships and temporal layers of information that would be hard to transmit otherwise.

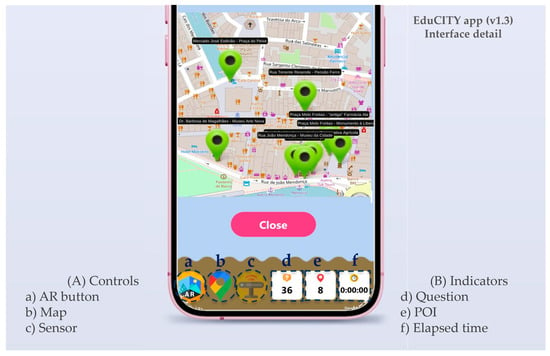

Studies regarding STE(A)M education have stated that AR can increase student motivation and understanding by contextualizing learning in authentic environments [40,41]. This aligns with the goals of the Art Nouveau Path, which uses AR to let participants see architectural details or past scenes, by videos or photographs, in situ, thereby deepening their appreciation of Art Nouveau heritage through direct interaction. Crucially, to deliver such location-based AR content effectively, the EduCITY app requires an intuitive cartographic interface (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

EduCITY app (version 1.3) cartographic interface.

In practice, this means combining on-site visual POIs, mapping information, GPS navigation cues, and AR visuals in a whole user experience. The map (digital or mental) remains the bridge between the user’s physical movement and the digital content: it guides users to points of interest and frames the AR usage narrative in context. Recent design research on mobile AR in cultural heritage underscores the importance of clear interaction patterns for storytelling, such as visual cues to guide users where to look or how to trigger content [42,43]. In essence, the AR platform must balance the richness of on-screen overlays with the need for spatial orientation, functioning as a dynamic map that not only shows where to go but also unlocks layers of narrative at each location.

Over the last decade, AR applications have become prevalent in cultural heritage, serving as both interpretative tools and entertainment media. Comprehensive reviews highlight a wide range of AR use cases in heritage, from virtual museum guides to on-site reconstructions of historical scenes [7,42,43]. These studies show that AR is particularly effective in engaging the public with heritage content by providing interactive experiences that can adapt to different ages and learning styles. Within this spectrum, location-based AR games form a distinct subset that merges AR with geolocation; examples include city exploration games and heritage treasure hunts. Empirical works by Kleftodimos and colleagues [19,20] describe location-based AR applications for historic districts, demonstrating how AR can facilitate both the communication of cultural information and active learning through exploration. Likewise, an AR serious game developed for cultural tourism was found to enhance 21st-century skills such as problem-solving and collaboration, indicating the educational potential of AR gaming in real urban settings [44]. These findings reinforce the idea that AR, when designed with pedagogical intent, can transcend novelty and serve as a cartographic interface that guides and teaches simultaneously. In the Art Nouveau Path implementation, the cartographic interface uses a persistent bottom bar and a dual-content area. The bottom bar presents three circular controls aligned to the left: the leftmost button activates AR mode (camera view for on-site marker scanning); the middle button shows or hides the in-app map; the right button opens the environmental sensors panel used in the project (for example, air particles and noise). To the right, three square indicators display, respectively, the current question over the total, the current POI over the total, and the elapsed session time (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

EduCITY app (v1.3) interface with (A) left controls, AR button (a), map (b), and sensors (c); and right indicators (B), question (d), POI (e), and elapsed time (f).

This cartographic functionality is underpinned by recent developments in AR-GIS technologies, especially in mobile contexts. Quaternion-based pose estimation pipelines support stable geo-registration and precise alignment of digital layers in camera space, while efficient rendering engines allow 2D and 3D vector data to be projected in real time over urban scenes [10,11]. Field-tested platforms like Smart Vidente further demonstrate how AR can enable on-site editing and visualization of GIS features, reinforcing its value as an operational cartographic medium [12]. These technological affordances substantiate our framing of AR as more than a narrative aid: it is a geovisual interface capable of layering semantically enriched content within physical space.

In the EduCITY app, a hybrid AR design is used, in which GPS cues provide path guidance and image-based markers anchor overlays to facades and architectural details in situ. The interface integrates AR with a map-centric workflow to support timely user transitions between navigation and AR engagement, minimizing cognitive load and preserving the primacy of on-site heritage exploration.

A well-designed AR-based cartographic interface augments rather than distracts from the physical exploration by coherently linking locations, narrative, and user actions.

2.4. Semantic Frameworks and Narrative Cartography

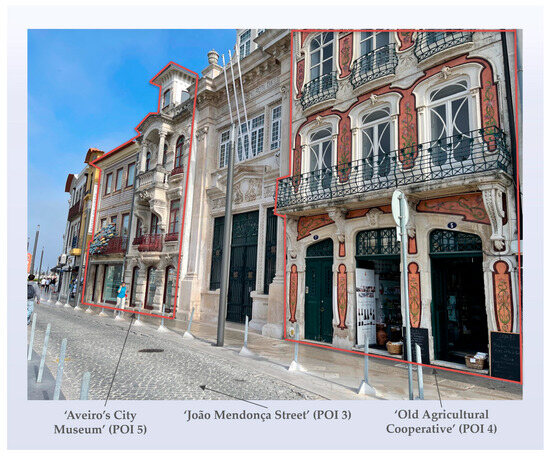

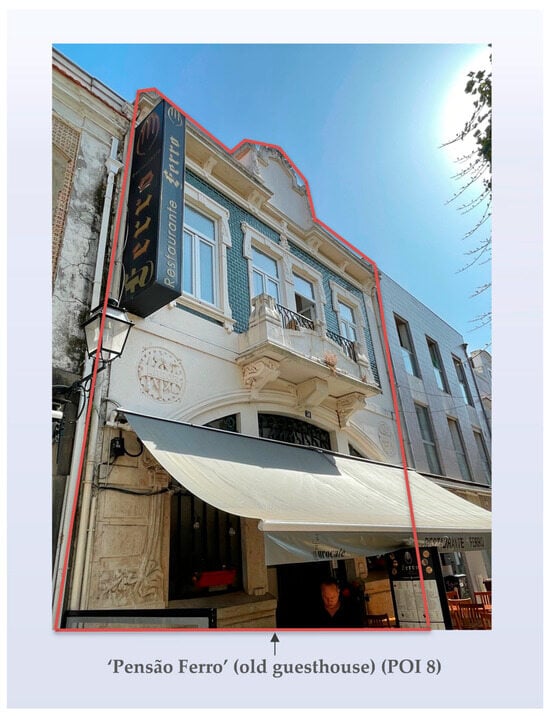

A key insight from heritage education research is that places and facts gain greater significance when they are woven into compelling narratives. Narrative cartography is the paradigm that explores the integration of storytelling with mapping, examining how maps can convey stories and how stories can be anchored in geographic space [15]. Rather than presenting historical information as isolated data points or disjointed site descriptions, narrative cartographic approaches link them along storylines that users can follow through space and time. This is particularly powerful in urban heritage contexts: a city like Aveiro can be seen as a palimpsest of cultural, artistic, and social histories, and narrative maps help uncover these layered stories. For instance, the Art Nouveau Path might be framed as a contribution to the story of a city’s transformation at the turn of the 20th century, based on the Art Nouveau movement chapter itself. In fact, each building and monument represents a “chapter” in the MARG but also Aveiro’s unique Art Nouveau narrative, from the ‘Obelisk of Freedom’, concluded in 1909 (POI 1) (Figure 5), the old ‘Ala Pharmacy’, concluded in 1915 (POI 2) (Figure 5), the ‘João Mendonça Street’ (POI 3) (Figure 6), the ‘Old Agricultural Cooperative’, a former private house that belonged to Mr. Anselmo Ferreira, and concluded in 1913 (POI 4) (Figure 6), the ‘Aveiro’s City Museum’, a former private house, concluded around 1915 (POI 5) (Figure 6 and Figure 7), the ‘Art Nouveau Museum’, a former private house, the ‘Mário Belmonte Pessoa’s House’, concluded in 1909 (POI 6) (Figure 8), the ‘Old Fish Market’, concluded in 1904 (POI 7) (Figure 9), to the ‘Pensão Ferro’ (old guesthouse), concluded in 1904 (POI 8) (Figure 10).

Figure 5.

‘Obelisk of Freedom’ (POI 1) and old ‘Ala Pharmacy’ (POI 2) at ‘Joaquim de Melo Freitas Square’, the MARG’s initial and final area.

Figure 6.

‘João Mendonça Street’ (POI 3), the ‘Old Agricultural Cooperative’ (POI 4), and the ‘Aveiro’s City Museum’ (POI 5).

Figure 7.

‘Aveiro’s City Museum’ (POI 5) and in-app POI 5 AR marker.

Figure 8.

‘Art Nouveau Museum’ (POI 6) and in-app POI 6 AR marker.

Figure 9.

‘Old Fish Market’ (POI 7).

Figure 10.

‘Pensão Ferro’ (old guesthouse) (POI 8) at ‘Lieutenant Rezende’ Street.

The MARG has a circular path, and the first POI is also the last one, which in this moment becomes a technical POI. The act of mapping these chapters is itself a narrative exercise since the selection and sequencing of sites create a plot that users experience spatially. Previous researchers have noted that maps are not neutral since they reflect the perspectives and purposes of their creators but also their users, essentially carrying a narrative or argument within their design [45].

By embracing narrative cartography, the Art Nouveau Path MARG aims to offer participants a coherent storyline of Art Nouveau in Aveiro, valuing it and developing sustainability competences through it rather than a random collection of facts. This approach can enhance user engagement and memory, as humans are cognitively wired to remember stories better than lists of information. Also, the sense of belonging is essential to activate learning [43]. Caquard [16] emphasizes the growing interest in the relationship between maps and narratives, suggesting that spatial narratives allow for multi-dimensional understanding, one that combines geography with chronology, emotion, and meaning. In practice, implementing narrative cartography in a mobile app means carefully designing the sequence of tasks and information to follow a narrative arc, perhaps with characters or thematic quests guiding the user.

Implementing narrative-driven experiences in a digital heritage project also calls for robust semantic frameworks to manage content and context. As the user moves through the narrative, the system must keep track of which story elements have been seen, how they relate to each other, and how they connect to real-world heritage objects. Semantic frameworks, often in the form of ontologies or knowledge graphs, provide a structured way to represent this information. In the cultural heritage sector, CIDOC-CRM has emerged as a prominent ontology for capturing the relationships between cultural artifacts, historical events, people, and places [38]. In the context of this MARG, the design principles are conceptually compatible with such a semantic standard, ensuring that each Art Nouveau landmark can be treated not merely as a GPS point but as an entity with attributes and relations that could be mapped to CRM classes and properties. This resonates in the MARG as information regarding the architectural style, dates of construction, curiosities, and links to other entities, like Réseau Art Nouveau Network (RANN) (https://www.artnouveau-net.eu/, accessed on 14 September 2025). The MARG’s narrative also presents the main local artists, like architects Francisco da Silva Rocha (1864–1957), Ernesto Korrodi (1877–1944), and Jaime Inácio dos Santos (1874–1942), or tile craftsmen and painters, like José de Pinho (1874–1964) and Lícinio Pinto (1882–1951), among many others.

This semantic enrichment of the MARG’s content enables a deeper interconnected narrative. For example, considering that two POIs in the Art Nouveau Path share one or two historical figures, the MARG’s design highlights that connection as part of the local and common past, thereby reinforcing belonging [46,47] and learning. Additionally, a well-defined semantic framework allows the project to be extensible and interoperable since new content can be added in a consistent way, and data can potentially be shared with digital libraries or museum databases.

Beyond CIDOC-CRM, broader semantic web technologies may be added in future work. By adding these, links may occur from the MARG’s own narrative to external knowledge, for instance, fetching related images or biographies from Portuguese or international artistic repositories or websites like the RANN one.

In summary, narrative cartography provides the conceptual model to fuse place and history, while semantic frameworks provide the data model to ensure that fusion is rich, consistent, and computable. Together, they enable the Art Nouveau Path to deliver an experience that is not only engaging on the surface but also built on a rigorous representation of cultural knowledge, paving the way for meaningful storytelling supported by data.

2.5. Smart Heritage and Sustainability Competences

Beyond the specific realms of geotechnology, AR, and storytelling, the Art Nouveau Path is situated at the intersection of smart cities, cultural heritage, and education for sustainable development. The term smart heritage encapsulates the idea of leveraging smart city technologies, such as ubiquitous connectivity, data analytics, and interactive media, to enhance the management and dissemination of cultural heritage [28,48].

In a smart city, infrastructure and citizens are increasingly connected, creating opportunities to engage the public with heritage in dynamic ways. Urban heritage thus becomes not just a static legacy to be preserved but an active resource in urban innovation and community identity. Recent research emphasizes integrating cultural heritage into smart city development through placemaking, arguing that technology-enhanced heritage experiences can strengthen local identity and social sustainability in cities [49]. By embedding the Art Nouveau heritage of Aveiro into a gamified app, the Art Nouveau Path illustrates this integration: the city’s unique art and architecture are used as anchors for a digital experience that is primarily educational while also offering potential value for cultural tourism, thereby contributing to smart heritage as a field distinct from but connected to smart education and smart tourism.

Importantly, global policy frameworks have started to recognize cultural heritage as a driver for sustainable development. The United Nations’ 2030 Agenda [50] and the New Urban Agenda [51] or the European Cultural Heritage Skills Alliance project [52] encourage cities to leverage heritage to achieve Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) [2] related to inclusive and sustainable communities, ground on education, and aiming for economic vitality [1,53]. Heritage-led development can foster a sense of place and continuity, contribute to social cohesion, and even drive sustainable urban regeneration. In line with these ideas, built heritage conservation and education are seen as part of the broader sustainability discourse [3]. The Art Nouveau Path design and narrative aligns with these global perspectives by using digital tools to make heritage accessible and engaging, thereby indirectly contributing to targets like quality education (SDG4), sustainable cities (SDG11), and partnerships for preserving cultural heritage (SDG17) [2].

A distinguishing goal of this MARG is to promote sustainability competences among its participants. Education for sustainable development (ESD) has increasingly focused on not just transferring knowledge about sustainability but cultivating competencies—combinations of skills, values, and attitudes—that empower individuals to act for sustainable futures. The European Commission’s GreenComp framework organizes these sustainability competences, identifying key areas such as critical thinking about sustainability, promoting fairness, valuing nature, and envisioning sustainable futures [18]. By engaging with the Art Nouveau heritage through this MARG, learners are prompted to reflect on themes like cultural preservation (why saving heritage is important for future generations), social inclusion (the artist’s names and old known photographs behind the buildings or monuments architecture), and environmental context (since Aveiro’s Art Nouveau inspiration relates to local flora and fauna as well as the use of local materials, like adobe or locally made tiles (Figure 11)).

Figure 11.

In-app (version 1.3) adobe example.

These reflections link to GreenComp competences. For example, recognizing the value of cultural and natural heritage aligns with valuing sustainability, and collaborating in gameplay can relate to participatory and fairness-oriented competences. Recent studies have started to explore the role of mobile AR games in fostering such competencies in urban settings. Marques et al. [54] found that MARGs designed for a smart learning city environment can indeed raise students’ awareness of sustainability issues and improve their understanding of sustainability concepts through active participation. Accordingly, in the Art Nouveau Path, this means that as players answer quizzes and uncover narratives, they are not only learning about Art Nouveau. Players are also practicing systems thinking (seeing how art, history, and urban life interconnect), strategic thinking (planning decisions through the MARG’s narrative), and collaborative and values reasoning (by working with others, appreciating heritage, and by learning about the need of preserving and valuing it). The MARG’s design was informed and validated by these educational goals [21,22], ensuring that the enjoyment of a walking tour around ‘known space’ [46,55] relates to moments of personal and peered reflection or discussion that are grounded on sustainability themes.

2.6. Synthesis and Implications for the Present Study

The reviewed literature indicates four design commitments that informed this study: (i) treating movement data as semantically enriched trajectories rather than inert traces, (ii) using AR as a cartographic interface that can enhance noticing and can support situated interpretation, (iii) structuring narratives as spatial storylines that bind architectural detail to place identity, and (iv) aligning the MARG tasks, multimedia and AR contents, and narrative with competence frameworks such as GreenComp [15] to move beyond school content recall. These commitments provided the foundation for the formulation of the RQs. RQ1 centered on the analysis of movement trajectories and navigation patterns along the path, while RQ2 focused on the investigation of the engagement of sustainability competences in competence-oriented tasks and AR resources. The present study also motivated the instrumentation and analyses reported in Section 3, namely, the collection and analysis of gameplay logs and teachers’ observations (T2-OBS) and the mixed-methods triangulation, where behavioral indicators are interpreted through narrative- and competence-oriented lenses. Collectively, these decisions establish the location-based AR game as a geoinformation source and an educational interface.

3. Materials and Methods

3.1. Research Design and Methodological Orientation

This study adopts an exploratory case study within a design-based research (DBR) approach [56,57], integrating design, enactment, analysis, and iterative refinement to align pedagogical goals, technological affordances, and curricular value [56,57]. The Art Nouveau Path was designed and implemented as part of the EduCITY Digital Teaching and Learning Ecosystem (DTLE) (https://educity.web.ua.pt/) (accessed on 14 September 2025), a research and development project based on the University of Aveiro (Portugal) that researches how MARGs can be embedded into urban educational contexts to foster ESD. Within this framework, the Art Nouveau Path functions as a place-based, competence-oriented intervention, transforming Aveiro’s Art Nouveau city heritage into both a ‘living classroom’ and an ‘experiential laboratory’ for sustainability competence development.

The broader research design included a quasi-longitudinal structure with several data collection toolsapplied in different phases. Three different questionnaires were applied to students (S1-PRE, S2-POST, S3-FU). These instruments were applied in three different phases: prior to the MARG activity (S1-PRE, to gather baseline data); immediately after the MARG activity (S2-POST, to collect immediate data); and S3-FU, aimed at understanding the MARG’s medium-term effect.

To collect data from teachers, the same approach was developed but in just two phases. The first phase aimed to validate the MARG. This validation occurred with thirty-three in-service teachers: thirty by participating in a themed workshop about the MARG, and three performing a MARG curricular review. All the suggestions of these teachers were considered for the last MARG version. This process is described in-depth in previous authors’ works [21,22].

Besides these, the gaming logs are also essential for the forthcoming analysis. For this study’s purpose, though, analysis is restricted to three qualitative sources of evidence: (i) a structured curriculum review conducted by teachers (T1-R), (ii) students’ open-ended post-game reflections (S2-POST), and (iii) in-field observations reported by accompanying teachers (T2-OBS). These are triangulated with the gaming logs.

Together, these data streams provide complementary perspectives on curricular alignment, student engagement, and the situated affordances of AR-mediated learning in an urban heritage environment. This methodological orientation follows established standards in serious games and ESD research, emphasizing ecological validity, competence orientation, and active stakeholder involvement [2,18,55,58,59].

3.2. Study Context and Intervention

This study was conducted in Aveiro, Portugal, where the city’s Art Nouveau district was mobilized as a ‘living laboratory’ for narrative, georeferenced learning. Aveiro’s Art Nouveau fabric, documented in urban–historical analyses of the city’s spatial evolution [60], offers a compact and walkable environment, in which facades, ornaments, and streetscapes serve as anchors for in situ analysis [21,22].

At the turn of the twentieth century, Art Nouveau blended international aesthetics with local identities and materials, making it particularly suitable for exploring sustainability-related themes such as nature motifs inspired by flora and fauna, craft traditions, water, and urban transformation [61,62].

The Art Nouveau Path operationalizes this built heritage as a geoinformation experience: a micro-itinerary of eight georeferenced POIs that combine map-based navigation with on-site AR exploration. Each POI integrates archival photographs, narrative prompts, and semantic tags, linking built heritage to sustainability competences through contextualized storytelling. In practice, sustainability themes were operationalized at task level as follows: (i) material literacy items that ask learners to recognize local materials and relate them to durability and maintenance in humid, saline environments; (ii) biodiversity and nature symbolism items that connect facade motifs to local ecosystems and water landscapes; (iii) stewardship and fairness prompts that elicit short reflections about reuse, care, and access to heritage; (iv) systems-thinking items that link tourism flows, noise, and pedestrian safety to path design choices; and, (v) futures-oriented prompts that invite small, realistic actions learners can take into their daily routines. These tasks are mapped to GreenComp areas of values, complexity, futures, and action, with exemplars distributed across POIs. AR and video assets make these links visible, while feedback frames correct and incorrect options in terms of sustainability reasoning rather than factual recall. The complete MARG mapping to the GreenComp framework [18] is available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.16981236 (accessed on 9 November 2025).

Considering that the MARG is an organized 8 POIs path, conceptually, the in-app city map provides an overview cartography, while the AR camera view functions as a situated layer that “remaps” architectural details directly onto the streetscape [8,21,22]. This conceptual design enhances wayfinding and spatial awareness while enabling stories to unfold across sites rather than being confined to a single landmark [19,20].

The Art Nouveau Path was developed between 2023 and 2024 as the research outcome of a doctoral project. Its design combined fieldwork on Aveiro’s built heritage with the creation of digital assets, including 3D models, AR features triggered by architectural details, and integrated multimedia resources. Across the eight POIs, participants engaged with 36 quiz-type questions, each structured around an introductory cue, a four-option multiple-choice task, and immediate feedback that clarified correctness and provided rationale. Historical photographs, contextualized video clips, and one audio recording were embedded as triggers to stimulate curiosity, spatial awareness, and critical reflection, implemented via the EduCITY mobile app (version 1.3). The validation with teachers (T1-VAL) and implementation with students happened with EduCITY’s Android smartphones, ensuring standardization across all the participant groups while maintaining ecological fidelity in authentic urban conditions.

EduCITY Mobile App: Architecture, AR Modalities, and User Interface

The EduCITY mobile app (version 1.3) was designed as an offline-first Android app. It leverages the device’s GPS and compass for location-aware functionality and integrates the Vuforia Augmented Reality Software Development Kit (SDK) to enable image-based recognition for marker-driven AR. The interface couples a 2D map view with an AR camera view and includes a persistent bottom toolbar that provides quick access to core controls for navigation and AR interaction. In our implementation, AR is hybrid: GPS-based navigation cues guide players to each site, while image-based markers anchor overlays to facades and architectural details in situ. Instrumentation and logging were defined prior. At the session level, the app records the date, start and end timestamps, app version, and the ordered sequence of visited POIs. At the item level, it records the unique item identifier, media tag, selected option, correctness, and the chosen distractor when incorrect. Logs are captured offline on the device and retrieved by the research team after each session for upload to a secure university server. Records are group-level only and contain no personal identifiers A parallel iOS build is available with equivalent functionality; the present study, however, used the EduCITY project’s Android devices.

3.3. Participants

Four groups contributed to this study. The first group comprised thirty in-service teachers (seventeen female, thirteen male) who participated in the validation workshop (T1-VAL). Simultaneously, the second group comprised three teachers with disciplinary expertise in history, natural sciences, and arts/citizenship conducted the MARG’s structured curricular review (T1-R). Their involvement ensured feedback on curricular and pedagogical alignment, usability, and the integration of sustainability competences.

The third group involved 439 students who participated in the implementation of the Art Nouveau Path MARG during regular school hours. Recruitment was carried out through the ‘Municipal Educational Action Program of Aveiro’ (PAEMA, 2024–2025 edition), resulting in a convenience sample. Students, aged 13–18, were distributed across 19 classes from 6 different grades (7th: N = 19; 8th: N = 135; 9th: N = 156; 10th: N = 37; 11th: N = 20; 12th: N = 72) from urban and peri-urban schools. No data on socio-economic background and gender were collected, as the study prioritized data minimization and ecological validity. While this decision aligns with the literature questioning the robustness of certain demographic effects [63], it also limits the possibility of analyzing differential patterns across groups.

While the broader project collected student data across three study phases (S1-PRE, S2-POST, and S3-FU), this paper focuses exclusively on the open-ended post-game reflections from the S2-POST instrument. Students played in groups of two to four, each group using a single EduCITY Android smartphone running the EduCITY app (version 1.3), which fostered collaboration and mirrored realistic device availability.

The fourth group comprised the accompanying teachers (N = 24) who supervised logistics and safety during the eighteen field sessions and documented their observations using the T2-OBS questionnaire, focusing on student engagement, navigation, and interaction with AR content in the real-world context.

Participation across all groups was voluntary. Informed consent was obtained from all teachers, and from students with supplementary parental or legal guardians’ authorization. No personally identifiable data were collected; all datasets are anonymized and compliant with the General Data Protection Regulation, in accordance with the ethical guidelines of the University of Aveiro.

3.4. Data Collection Instruments

The study employed four complementary instruments, each targeting a distinct group of participants and designed to capture a specific layer of evidence. When considered as a whole, these instruments provided a basis for methodological triangulation consistent with the principles of DBR [53,54]. This methodological triangulation combined perspectives from curricular review, student reflection, ecological observation, and automated traces of gameplay. Table 1 provides an overview of the instruments employed in this study, which are described in detail.

Table 1.

Overview of data collection instruments used in this study.

The MARG’s curricular review (T1-R) was conducted by three in-service teachers from the subject areas of history, natural sciences, and arts/citizenship. Each teacher was granted access to the comprehensive set of game materials, encompassing the narrative sequence, quiz items, AR markers, and associated multimedia resources. These teachers were invited to complete a curricular structured rubric individually. The rubric guided their analysis across six key dimensions: (i) the alignment of content with curricular objectives; (ii) the potential for interdisciplinary articulation; (iii) the promotion of critical thinking; (iv) the fostering of observational and analytical skills; (v) the application of discipline-specific concepts, and (vi) the cognitive- and age-appropriateness of the MARG materials and narrative. Teachers were encouraged to provide a rationale for their ratings, producing evaluative judgments supported by qualitative commentary. Their contributions not only substantiated the curricular and pedagogical coherence of the Art Nouveau Path but also highlighted refinements in language, scaffolding, and sequencing. In-depth analysis of this MARG’s curricular review was the focus of authors’ previous works [21,22].

The students’ post-game questionnaire (S2-POST) was administered to all 439 participants immediately after gameplay. While the instrument combined scaled and dichotomous items with open-ended prompts, this study draws exclusively on the latter. The students were tasked with providing examples of their learning, completing the sentence ‘For me, sustainability is...’ and articulating novel insights concerning the Art Nouveau heritage. The participants were invited to consider the following questions: first, whether cultural heritage could serve as a pathway into sustainability; second, whether they wished to learn more about Aveiro’s Art Nouveau; and third, whether they recognized competences for sustainability within the MARG. Despite the incorporation of an adapted Portuguese version of the GreenComp-based GCQuest instrument (available at https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.15919738 accessed on 9 November 2025), the scope of this paper does not encompass the aforementioned scaled items. The open-ended responses are of significant value, as they elucidate the way students articulated their learning, integrated values with knowledge, and expressed affective engagement with the interplay of heritage and sustainability. This instrument was applied immediately after playing the MARG.

The Teachers’ observation instrument (T2-OBS) was completed by 24 accompanying teachers during the field sessions. This instrument combined Likert-scale statements, structured checklists, and space for narrative reflection. Teachers were invited to comment on the extent to which the game supported competence development, heightened student interest through AR, and encouraged appreciation of local heritage. Additionally, concrete observations of student behaviors were recorded, including curiosity towards architectural elements, the capacity to engage in discourse concerning sustainability matters, expressions of pride in local heritage, collaborative problem-solving, and group interactions. The instrument’s inclusion of items concerning professional impact was a notable feature. These items sought to ascertain whether the experience motivated teachers to incorporate heritage, sustainability, or AR-based strategies in their future practice. Consequently, the observations furnished an ecological perspective on the intervention’s progression in authentic educational settings.

The fourth instrument comprised the automated gameplay Logs, which were generated by the EduCITY app (version 1.3) during each session. A total of 118 student groups, each consisting of two to four learners sharing one smartphone, participated in the study. As each group played, the app recorded critical events, for example, POI arrival detected by a location-based trigger, AR marker detected, quiz answer submitted, and video played, as timestamped entries in a JSON log file stored in the app’s private data folder on the device. After each session, these per-group JSON files were retrieved via USB and uploaded to a secure University of Aveiro server for aggregation and analysis. The schema includes, at the session level, date, start and end timestamps, app version, and ordered POI sequence; and at the item level, a unique item identifier, media tag, selected option, correctness, and the specific distractor when incorrect. Logs are stored exclusively at the group level and contain no personal identifiers, ensuring ethical and GDPR-compliant data minimization. Despite the temporal resolution limitations of the logs, which preclude estimating dwell time at specific POIs, the logs provide robust evidence on system feasibility, pacing variability across groups, and item-level performance patterns. A summary of the logging schema is available on Zenodo (https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17507328, accessed on 9 November 2025); distractor-level and other sensitive fields are omitted until publication; full item-level logs are available on reasonable request.

In this study, these instruments were employed for three primary purposes: first, to summarize completion and accuracy distributions; second, to identify outliers in session duration; and third, to cross-check the ecological evidence recorded by the accompanying teachers (T2-OBS).

When considered as a whole, these four instruments provided a consistent and multifaceted methodological framework. Each perspective informed the Art Nouveau Path project from a distinct vantage point, and their integration enabled a more comprehensive understanding of the MARG’s functionality and goals. This functionality encompasses its role as a pedagogical resource grounded in curricular demands and as a situated, AR-mediated learning experience embedded within the spatial and cultural fabric of the city of Aveiro. All these instruments are available at the Data Availability Statement.

3.5. Field Procedures and Data Capture

The field sessions were conducted between February and May 2025, following the teachers’ validation (T1-VAL) and curricular review (T1-R) undertaken in December 2024.

Each activity began with a short safety and interface briefing, an adjustment suggested during the T1-VAL workshop, after which student groups initiated the linear and circular path crossing the eight POIs in Aveiro’s Art Nouveau historic neighborhood. The path was supported by the in-app map, combined with in situ and in-app informative markers (like photographs and narrative guide) and GPS cues. At each site, multimodal content, including AR overlays, videos, and photographs (early 20th century), introduced the location, followed by quiz-type challenges linked to architectural and surrounding details. This multimodal progression through the city fostered embodied engagement and contextual learning, which have been highlighted as key affordances of mobile AR in heritage education [19,20,40,44].

Each session concluded with a short debrief. Students then completed the S2-POST questionnaire, while accompanying teachers finalized their T2-OBS questionnaires. Project smartphones were collected after each field session. As the devices had no SIM cards or mobile data, logs were stored locally during gameplay and synchronized at the University of Aveiro via a secure network to a dedicated server immediately after collection. This procedure ensured data integrity while preventing in-field connectivity issues.

3.6. Data Analysis Strategy

The analysis followed a mixed-methods approach [64,65], combining descriptive statistics, thematic coding, and triangulation into an explanatory synthesis [26]. The gameplay logs were treated quantitatively at the group level (N = 118), with descriptive measures calculated in Excel, for session duration, completion, and accuracy, as well as the distribution of distractor choices in cases of incorrect responses. These indicators were used to characterize overall performance patterns and to highlight items or POIs where difficulties tended to concentrate.

The qualitative materials, teacher reflections (T1-R) and observational questionnaire (T2-OBS), and students’ open-ended responses (S2-POST) were examined through thematic analysis by the authors and an EduCITY team member. Deductive categories were derived from previous works [21,22,54] and from the GreenComp framework [18], while inductive coding enabled the identification of emergent dynamics. This process converged into four cross-cutting categories that guided the interpretation of results: (i) attention to the built heritage and architectural details, (ii) the role of AR as a catalyst for interest, (iii) spatial trajectories and urban mobility, and (iv) critical reflection on sustainability and the city. The teachers’ curriculum review (T1-R) is treated as an external validation axis that triangulates with these four categories, since it has been previously analyzed and published.

Coding reliability was strengthened through iterative double-coding and peer debriefing, ensuring that interpretations remained grounded in the data.

Finally, quantitative and qualitative findings were integrated into analytic matrices linking GreenComp dimensions to the different datasets. Outliers and apparent inconsistencies were approached as instructive for design refinement rather than as anomalies, reflecting the DBR principle of aligning design, enactment, analysis, and iterative redesign [56,57]. This integrative strategy provided the foundation for the explanatory synthesis reported in the findings.

4. Findings from the Art Nouveau Path Implementation

4.1. Overview of Data Sources

The findings draw on complementary datasets: automated gameplay logs (N = 118 groups), students’ post-game open-ended reflections (S2-POST, N = 439), observation protocols from accompanying teachers (T2-OBS, N = 24), and the structured curriculum review by three in-service teachers (T1-R). Categories of analysis were developed collaboratively by the two authors and one EduCITY researcher, through thematic analysis, combining GreenComp-informed deductive coding with inductive coding. Four cross-cutting categories were identified: (i) attention to the built heritage and architectural details, (ii) the role of AR as a catalyst for interest, (iii) spatial trajectories and urban mobility, and (iv) critical reflection on sustainability and the city. The teachers’ curricular review (T1-R) can be regarded in the following as a fifth category (v).

4.2. Attention to the Built Heritage and Architectural Details

Across all sources, students consistently oriented their attention to material features of Aveiro’s Art Nouveau, such as tiles, ironwork, stained glass, and the ‘whip line’, and discussed both aesthetic and functional aspects. In S2-POST (N = 439), 71 students (17.20%) explicitly mentioned tiles, often highlighting their decorative qualities, while 13 students (3.10%) referred to functional roles, including protection against humidity and water. Mentions of the whip line appeared in 30 responses (7.30%) and stained glass in 1 response (0.20%), whereas ironwork did not emerge in this dataset. These coded values and scripts are openly available in the project’s dataset repository. T2-OBS records from accompanying teachers (N = 24) provide convergent evidence. Specifically, 16 teachers (66.70%) reported enthusiasm when discovering architectural details, and 14 (58.30%) noted curiosity about built heritage, both consistent with student attention to facades and decorative features. Moreover, 18 teachers (75.00%) observed collaboration and peer explanations, aligning with peer discussions triggered by AR prompts. At the same time, ironwork and stained glass did not emerge in teacher reports, corroborating the absence of these features in the student dataset.

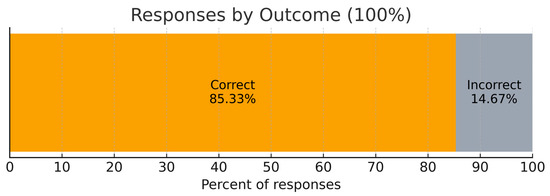

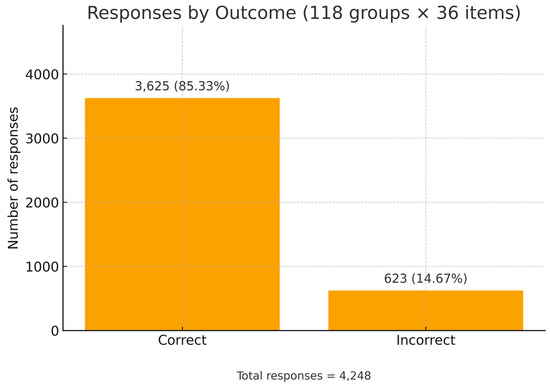

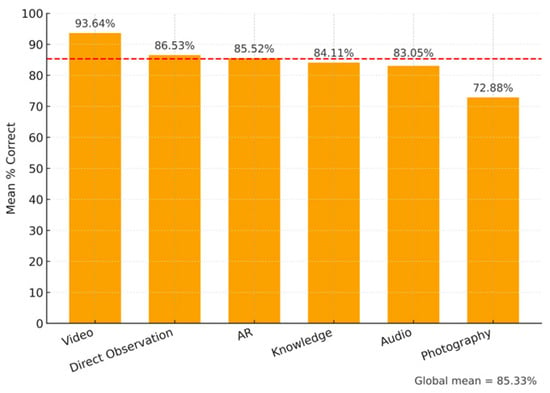

The logs provide the strongest quantitative evidence. Considering the 118 groups and the 36 questions–items, the global results are 4248 group–item responses. The overall accuracy was 85.33% (3625 correct; 623 incorrect), as presented in Figure 12 and Figure 13.

Figure 12.

Aggregate distribution of correct versus incorrect responses across all group–item interactions (% of responses) (N groups = 118; N items = 36; N responses = 4248).

Figure 13.

Absolute counts of correct and incorrect responses across all group–item interactions. Absolute counts of correct and incorrect responses across all group–item interactions (N responses = 4248).

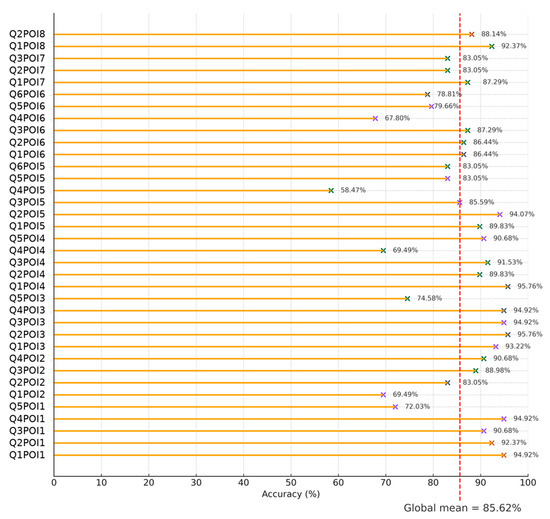

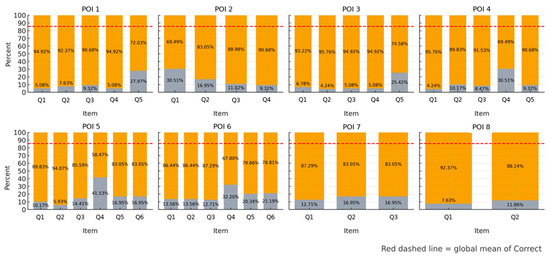

Items anchored in directly observable features were solved more reliably. At the POI level, mean accuracy was highest at POI 3 (90.68%) and POI 8 (90.25%) and lowest at POI 6 (79.38%) and POI 5 (82.34%). At the item level (coded Q[number]POI[POI’s number]), the easiest were Q2POI3 and Q1POI4 (95.76% each), followed by Q1POI1, Q4POI1, and Q4POI3 (94.92% each). The most challenging were Q4POI5 (58.47%), Q4POI6 (67.80%), Q4POI4 (69.49%), Q1POI2 (69.49%), and Q5POI1 (72.03%). This is presented in Figure 14 and Figure 15.

Figure 14.

Item-level accuracy (%) per POI of the Art Nouveau Path (POI 1 to POI 8). (N groups = 118; N items (QxPOIx) = 36; N responses = 4248.

Figure 15.

Correct (orange) versus incorrect (grey) responses for each quiz item (Qx), grouped by POI (POI 1 to POI 8). Bars show counts of group–item responses (N = 4248).

Because the logs store the specific distractor chosen when groups answered incorrectly, problematic options can be isolated and the POI information enhanced in subsequent refinements.

Taken together, triangulation suggests that the pathway successfully fostered observational engagement with built heritage: what students reported noticing and interpreting (S2-POST; T2-OBS) aligns with higher performance on detail-based items in the logs. This pattern resonates with GreenComp dimensions of critical thinking and valuing sustainability [18].

4.3. The Role of AR as a Catalyst for Interest

S2-POST questionnaire answers frequently describe AR as making obscure or “invisible” features salient, sparking curiosity and discussion. T2-OBS notes similarly highlight visible excitement when AR overlays direct attention to hidden details, with teachers reporting spontaneous peer explanations.

From a performance perspective, the logs show that AR-labeled items (N = 11) achieved a mean accuracy of 85.52%, comparable to direct observation items (86.53%) and only slightly lower than video items (93.64%). These results are presented in Figure 16.

Figure 16.

Mean accuracy (%) across items grouped by media type (N = 36 items; 118 groups; 4248 group–item responses). Media categories comprise AR (11 items), video (2 items), direct observation (9 items), and photographs/images (14 items).

This indicates that AR-mediated prompts did not hinder task performance and often supported it to a similar level.

Not all AR items were equally effective. The most challenging were Q4POI6 (67.80%) and Q5POI1 (72.03%), where teachers noted quick distraction in busy streetscapes or subtle distinctions between similar elements. This suggests that when conceptual load and visual discrimination co-occur, AR prompts should be paired with additional scaffolding (e.g., contrastive zooms, simplified overlays, or staged hints). Conversely, items such as Q4POI1 (94.92%) performed at the highest level, showing that in contexts where the target feature is visually distinctive and the narrative concise, AR can be highly effective.

Overall, qualitative accounts regarding increased motivation and noticing align with stable quantitative performance on AR items. Concerning GreenComp [18], these findings sit at the intersection of exploring complexity and strategic problem-solving, with AR functioning as a mediational tool rather than an outcome in itself.

4.4. Spatial Trajectories and Urban Mobility

Although the logs do not encode within-route path or dwell times per POI, two indicators provide insight into feasibility and progression: accuracy per POI and session duration. First, mean accuracy remained high at the end of the path (POI 8: 90.25%), indicating limited fatigue effects and sustained effectiveness of tasks. The two most demanding sections were POI 6 (79.38%) and POI 5 (82.34%), which teachers associated in notes with denser traffic/noise, presence of groups of tourists, and more intricate discrimination. The data is presented in Figure 17.

Figure 17.

Mean accuracy (%) at each POI along the Art Nouveau Path (118 groups; 4248 group-item responses; POIs 1–8).

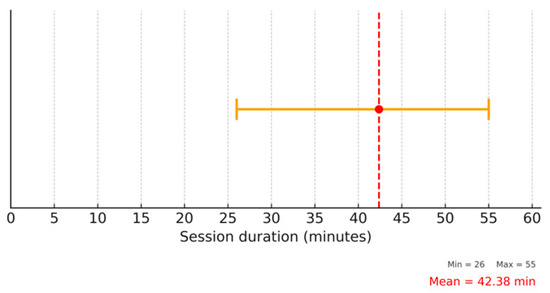

Second, group-level durations averaged 42.38 min (min = 26, max = 55), placing the activity comfortably within a lesson period window while leaving time for briefing and debriefing, as presented in Figure 18.

Figure 18.

Distribution of session durations across all groups (N = 118; in minutes).

S2-POST answers (n = 49/439: 11.16%) frequently describe walking as an essential part of the experience (like ‘we learned by walking and seeing’), and T2-OBS records display recurrent wayfinding talk (n = 15/24: 62.50%) and comparisons between facades during transitions between POIs (n = 13/24: 54.17%). These findings support the argument that embodied movement and narrative cartography scaffold in situ learning [19,20]. From the MARG’s design standpoint, the POI-level pattern suggests the need for additional scaffolding at POIs 5 and 6 (like noise-aware prompts or clearer framing for visually similar elements) while preserving the strong closure at POI 8.

4.5. Critical Reflection on Sustainability and the City

Evidence of conceptual integration, linking heritage, materials, and urban choices to sustainability, appears prominently in S2-POST, with definitions that extend beyond the environment to include preservation, stewardship, and civic responsibility. T2-OBS records similarly capture discussions around ‘why to preserve’ or ‘how choices affect the city’.

Quantitatively, items classified as knowledge (N = 12) had a mean accuracy of 84.11%, compared with 86.53% for direct observation and 93.64% for video. These categories capture different dimensions (cognitive type vs. media modality) and are not mutually exclusive, but their comparison helps identify where conceptual load or representational mode may have influenced performance. Three of the five most difficult items were concept-heavy: Q4POI5 (58.47%), Q4POI4 (69.49%), and Q3POI7 (83.05%), with the remaining two being AR-mediated (Q4POI6 67.80%, Q5POI1 72.03%). Conversely, the five easiest items were Q2POI3 (95.76%) and Q1POI4 (95.76%), followed by Q1POI1 (94.92%), Q4POI1 (94.92%), and Q4POI3 (94.92%), showing that when features were visually distinctive and prompts concise, students achieved near-perfect performance.

This profile points to two complementary refinements: (i) for conceptual items, augment feedback and pre-hints that explicitly connect heritage facts to sustainability values and systems thinking; (ii) for visually similar contrasts under AR, add contrastive scaffolds (like visual close-ups, outline overlays, before and after images) to support more reliable discrimination. Regarding the GreenComp framework [18], this category illustrates enactments of systems thinking and valuing sustainability while also indicating where instructional supports are most needed for deeper conceptual perception.

4.6. Curriculum Validation by Teachers (T1-R)

The structured curriculum review (T1-R) engaged three in-service expert teachers of history, natural sciences, and visual arts/citizenship curricular areas. Their contributions confirmed that the Art Nouveau Path aligns with the Portuguese national curriculum while also fostering interdisciplinary connections and sustainability competences.

In line with previous analyses already reported in previous works [21,22], the teachers highlighted curricular opportunities for cross-disciplinary work (integrating biodiversity, civic identity, and urban history) and the development of critical and reflective practices (from analyzing historical change to debating heritage preservation). They also emphasized age-appropriateness, noting that the game is well calibrated for the third cycle while adaptable to secondary level through extended, research-oriented tasks. Table 2 presents an overview of the curricular validation analysis of the three teachers (T1-R).

Table 2.

Curriculum validation perspectives based on T1-R.

In this study, the T1-R dataset is mobilized not as a stand-alone validation but as part of a triangulation strategy and as a broader contributor. When compared with gameplay logs, post-game student answers (S2-POST), and in-field teacher observations (T2-OBS), the curriculum validation (T1-R) underscores how disciplinary alignment strengthens both the feasibility and the legitimacy of heritage-based tasks within formal schooling.

This external confirmation by subject specialists reinforces the GreenComp-informed analysis [18], demonstrating that the Art Nouveau Path can operate simultaneously as a curricular, interdisciplinary, and civic resource for ESD.

Together, these findings show that the Art Nouveau Path integrates curricular alignment, situated observation, and motivational affordances of AR into a coherent educational experience. Across datasets, students demonstrated strong engagement with architectural details, sustained performance across the path, and growing capacity to connect heritage with sustainability. Teachers’ observations and curricular validations further confirm the feasibility of embedding the pathway in formal schooling while stimulating interdisciplinary learning and critical reflection. These results provide a consolidated empirical basis for the design implications discussed in the following section.

5. Discussion of the Art Nouveau Path Findings

The implementation of the Art Nouveau Path illustrates how location-based AR games can simultaneously generate analyzable geoinformation and function as cartographic interfaces that enrich the semantic and narrative depth of cultural heritage. By triangulating the gameplay logs, student reflections, teacher observations, and curriculum review, the study provides a multifaceted account of how such interventions operate within the complexity of urban space and formal education. This section returns to the two guiding research questions. First, it examines how location-based AR games contribute to the production and analysis of geoinformation in urban heritage contexts (RQ1). Second, it discusses the ways in which AR functions as a cartographic interface that enhances spatial storytelling and semantic representation of cultural heritage (RQ2).

5.1. Location-Based MARGs as Sources of Geoinformation

The findings demonstrate that the Art Nouveau Path produced geoinformation at two complementary levels. At the behavioral level, automated gameplay logs captured 4248 group–item responses across 118 groups (N = 4, 248; correct n = 3625; incorrect n = 623), providing quantitative indicators such as accuracy, completion, and session duration. Patterns were spatially and semantically structured: accuracy was highest at POI 3 (n = 535/590: 90.68%) and POI 8 (n = 213/236: 90.25%) and lowest at POI 6 (n = 562/708: 79.38%) and POI 5 (n = 583/708: 82.34%). Such structures echo established methods of trajectory analysis in GIScience [13,37], but here they are anchored to pedagogical content rather than inert traces.

At the semantic level, the logs extended beyond correctness to record distractor choices, enabling the identification of recurring misconceptions. This provided interpretive depth absent in traditional GPS-based studies and resonates with proposals in spatial data science to integrate movement data with semantic annotations [5,6]. The triangulation with teachers’ observations (T2-OBS) and student reflections (S2-POST) confirmed that patterns in the data were pedagogically meaningful: details noticed and discussed by learners corresponded to higher accuracy in the log records. In this way, the game generated analyzable geoinformation that was not merely positional but educationally situated.

5.2. AR as a Cartographic Interface

The second research question focused on AR as a cartographic interface. The results indicate that AR overlays consistently mediated attention rather than distracted it. Items supported by AR (N = 11 items, 1110/1298 correct: 85.52%) achieved accuracy rates comparable to those relying on direct observation (N = 9 items, 919/1062 correct: 86.53%) and only slightly lower than video-supported tasks (N = 2 items, 221/236 correct: 93.64%).

Qualitative accounts from both students and teachers highlight AR’s role in making subtle or invisible features salient, prompting gestures, peer explanation, and dialogue. These outcomes support prior claims that AR can act as an interpretive cartographic layer, embedding narrative meaning into place [8,15].

Nevertheless, the mediational value of AR was contingent on task design and environmental context. Conceptually demanding or visually ambiguous tasks, such as Q4POI6 (n = 80/118 correct: 67.80%), showed lower performance, particularly in noisy streetscapes. Conversely, tasks with clear visual anchors, such as Q4POI1 (n = 112/118 correct: 94.92%), reached the highest performance and were described as highly engaging. These contrasts underscore that AR strengthens spatial storytelling when overlays are distinctive, narratively concise, and contextually framed. In such conditions, AR extended the map into a live, situated interface that orchestrated attention and sustained narrative progression across the urban fabric.

5.3. Conceptual Integration and Competence Orientation

Beyond perceptual noticing, the study revealed challenges in consolidating conceptual links between heritage and sustainability. Concept-heavy items such as Q4POI5 (n = 69/118 correct: 58.47%) and Q4POI4 (n = 82/118 correct: 69.49%) yielded lower accuracy, despite student reflections that broadened sustainability definitions to include stewardship, civic responsibility, and heritage preservation. This divergence suggests that while AR supports perceptual engagement, competence-oriented reasoning requires additional scaffolding. This finding is consistent with educational research that identifies the limits of AR for fostering conceptual depth without deliberate instructional mediation. Dunleavy and Dede’s work [39], for example, emphasizes that ‘scaffolding each experience explicitly at every step’ is critical to prevent superficial engagement and to enable conceptual consolidation in AR learning environments [39]. Such a pattern also aligns with wider research in ESD, where competences like systems thinking and future orientation are shown to emerge only when facilitated through structured prompts and reflection [2,18].

Regarding the DBR approach, these findings identify sites for iterative refinement rather than anomalies [56,57]. Enhancing feedback, embedding pre-hints, and linking architectural facts explicitly to sustainability principles are necessary to transform immediate noticing into conceptual understanding. This balance between perceptual and conceptual scaffolding is essential if AR games are to act not only as vehicles of engagement but also as catalysts for competence development.

5.4. Teachers’ Validation and Curricular Relevance

Finally, the structured curriculum review confirmed the relevance of the Art Nouveau Path within formal education. Teachers in history, natural sciences, and arts/citizenship highlighted curricular relevance, interdisciplinary opportunities, and age-appropriateness, confirming that the intervention aligns with national standards while remaining adaptable across cycles. Their reflections strengthen the claim that heritage-based AR games can function as curricular resources rather than peripheral activities. This echoes broader calls for stakeholder participation in DBR cycles and for embedding ESD innovations within formal curricular frameworks [56,57].

Taken together, the discussion demonstrates that the Art Nouveau Path generated geoinformation that was both analyzable and semantically rich, while AR acted as a cartographic interface that mediated attention and narrative. At the same time, conceptual items revealed the need for additional scaffolds to support competence development, and teacher validation provided assurance of curricular coherence.

6. Conclusions

This study researched how a location-based MARG can serve as both a source of geoinformation and a cartographic interface in the context of urban heritage education. Regarding these, the study addressed two guiding questions: (i) how location-based AR games contribute to geoinformation analysis and (ii) how they function as cartographic interfaces for enriched storytelling.

6.1. Main Findings

The MARG generated meaningful geoinformation at both behavioral and semantic levels, revealing structured patterns of interaction and misconceptions. These data, triangulated with teacher and student feedback, showed that AR overlays effectively mediated attention and enriched spatial storytelling, although performance was context-sensitive.

6.2. Limitations

This study deliberately narrows its scope to evidence generated during the first large-scale implementation of the Art Nouveau Path. The analysis focused on four complementary sources: automated gameplay logs, the cartographic and AR interfaces experienced in situ, the narrative design in action, and teachers’ observations of engagement captured through the T2-OBS protocol, complemented by students’ post-game reflections (S2-POST). These datasets make it possible to examine how the design functioned in practice and whether it achieved its intended effects during initial field deployment, which is a central aim of early-cycle DBR [56,57].