Abstract

Assessing the accessibility of urban metro stations is essential for optimizing metro system planning and improving travel efficiency for residents. This study proposes an innovative evaluation framework—the CWM-GRA-TOPSIS model—for comprehensive metro station accessibility assessment. First, a multi-dimensional indicator system is established, encompassing three key dimensions, to-metro accessibility, by-metro accessibility, and land use accessibility, which are further refined into 14 secondary indicators for detailed analysis. A Combination Weighting Method (CWM) is then introduced, integrating the Analytic Hierarchy Process (AHP) for subjective weighting and the Criteria Importance Through Intercriteria Correlation (CRITIC) method for objective weighting, with their integration optimized through Game Theory. Subsequently, the overall accessibility of metro stations is evaluated and ranked using a hybrid Grey Relational Analysis (GRA) and Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) approach. The proposed method is applied to Wuhan, China, to demonstrate its effectiveness and applicability. Results show that the CWM-GRA-TOPSIS model, by balancing objectivity and practical relevance, provides a more reliable and systematic approach for identifying accessibility disparities and formulating targeted improvement strategies for urban metro systems.

1. Introduction

With the rapid pace of urbanization and motorization, metro systems have become one of the most critical modes of urban public transportation, providing high-capacity, efficient, and environmentally friendly mobility [1]. As a fundamental component of sustainable urban development, metro systems play a pivotal role in alleviating traffic congestion, reducing energy consumption, and guiding spatial structure [2,3]. Among the multiple dimensions of metro system performance, accessibility is widely recognized as a key measure that reflects how easily passengers can reach, use, and benefit from the metro service [4]. Therefore, a comprehensive evaluation of metro station accessibility is essential for optimizing network design, improving service equity, and supporting transit-oriented development (TOD) strategies [5,6].

Despite growing scholarly interest, several critical challenges remain in the evaluation of metro accessibility [7]. First, existing studies often lack a standardized and systematic indicator framework, resulting in fragmented and sometimes inconsistent assessments. Many focus narrowly on network connectivity or surrounding land use characteristics, while few studies holistically integrate transport, land use, and travel demand dimensions. Second, most existing weighting methods rely solely on either subjective approaches (e.g., Analytic Hierarchy Process, AHP [8]) or objective methods (e.g., Entropy Weight Method, EWM [9]), thereby limiting robustness and generalizability of results [10]. Third, although the Technique for Order Preference by Similarity to Ideal Solution (TOPSIS) has been widely used in accessibility evaluations due to its simplicity and interpretability [11,12], it remains vulnerable to indicator correlation and weight sensitivity, which may bias the final rankings [13]. The integration of advanced methods such as Grey Relational Analysis (GRA) with TOPSIS, which can enhance result stability and reduce correlation bias, remains relatively underexplored in metro accessibility research [14].

To make up for these problems, this study proposes a comprehensive metro station accessibility evaluation framework that integrates a Combined Weighting Method (CWM) with the GRA-TOPSIS approach. The framework incorporates three key dimensions—to-metro accessibility, by-metro accessibility, and land use accessibility—to capture the entire travel chain from origin to destination. The CWM balances subjective expert judgment and objective data-driven weighting to achieve greater reliability, while the GRA-TOPSIS method enhances the robustness and discriminatory power of the evaluation results. This methodological innovation contributes to both academic research and practical planning by providing a more systematic, reliable, and interpretable tool for evaluating metro station accessibility and informing sustainable urban transport development.

The structure of the remaining part of this article is as follows. Section 2 reviews existing literature on metro accessibility evaluation and methodological approaches. Section 3 details the proposed analytical framework, including indicator system construction, weighting process, and evaluation procedure. Section 4 presents the empirical application of the model to Wuhan, China, and analyzes the evaluation results. Finally, Section 5 discusses the main findings, policy implications, and conclusions.

2. Literature Review

2.1. Metro Accessibility and Its Dimensions

Accessibility is a fundamental concept in transport geography and urban planning, reflecting the ease with which people can reach desired activities or services. Hansen (1959) first conceptualized accessibility as the potential opportunity for spatial interaction, laying the theoretical foundation for linking transportation and land use system [15]. Since then, the concept has evolved into a multi-dimensional construct encompassing transport networks, urban form, and socioeconomic factors.

In recent decades, people have developed various quantitative methods to measure accessibility. Early research, such as that of Torsten H., emphasized the temporal and spatial constraints of travel, proposing time-space approaches to assess accessibility [16]. Subsequent methodological advances introduced models such as cumulative opportunity, gravity-based land use interaction, and topological network analysis [17,18,19], each offering a different lens for understanding spatial accessibility. With the advent of Geographic Information Systems (GIS) and computational modeling, accessibility evaluation has become increasingly data-driven, enabling the integration of multiple transport modes, spatial layers, and behavioral factors within comprehensive analytical frameworks.

In the context of metro systems, accessibility can be analyzed across three interrelated dimensions: (1) to-metro accessibility, describing how easily passengers can access metro stations from their points of origin [20,21]; (2) by-metro accessibility, capturing the connectivity and efficiency of the metro network itself [22,23]; (3) land use accessibility, referring to the opportunities and services accessible around metro stations [24,25]. Together, these dimensions represent the full travel chain—from access to the station, through the metro journey itself, to the activities accessible upon arrival—thus providing a holistic framework for evaluating metro system performance. However, many existing studies assess these dimensions in isolation, emphasizing either transport connectivity or land use characteristics, while neglecting their interdependence and feedback effects among transport supply, travel demand, and spatial opportunities.

Recent research has begun to address these shortcomings by integrating multiple dimensions within unified analytical frameworks. For example, Wu (2023) proposed a comprehensive model combining to-metro, by-metro, and land use accessibility, emphasizing the dynamic interactions among transport infrastructure, urban morphology, and human activity patterns [26]. Although such multidimensional approaches mark an important step forward, key methodological challenges remain, particularly in determining appropriate indicator weights and addressing correlations among variables. These limitations may lead to instability and reduced robustness in evaluation results, underscoring the need for more adaptive and integrative assessment frameworks for metro accessibility.

2.2. Weighting Approaches in Multi-Criteria Evaluation

Indicator weighting plays a pivotal role in multi-criteria evaluation, as it directly determines the validity, transparency, and interpretability of accessibility assessments [27,28]. Early studies primarily relied on subjective weighting methods, such as the AHP, which rely on expert judgment and policy preferences. While these approaches reflect planning priorities and contextual expertise, they are often limited by expert bias and a lack of reproducibility [29]. In contrast, objective weighting methods, such as Data Envelopment Analysis (DEA) [30], EWM [9], or CRITIC [31], derive indicator weights from data variability and inter-indicator correlations. These approaches enhance consistency and objectivity but may overlook the normative or strategic importance of certain indicators.

To overcome these limitations, hybrid weighting approaches have gained increasing attention. By combining subjective and objective components, hybrid models leverage the strengths of both human expertise and data-driven reasoning [32]. This balanced approach is particularly appropriate for metro accessibility evaluation, where both quantitative performance measures and planning objectives must be considered to reflect the true complexity of urban transport systems.

2.3. Evaluation Methods: From TOPSIS to GRA–TOPSIS

Multi-Criteria Decision-Making (MCDM) methods are commonly used to synthesize weighted indicators into composite accessibility scores [33]. Among them, the TOPSIS has been widely adopted due to its simplicity and effectiveness. However, traditional TOPSIS methods may face challenges when dealing with highly correlated indicators or unstable weight structures, as the Euclidean distance-based aggregation can distort the contribution of individual indicators and affect ranking accuracy [34]. To address these issues, GRA has been incorporated into TOPSIS frameworks to measure the similarity between alternatives based on their relational coefficients [35,36]. The resulting GRA–TOPSIS hybrid combines the advantages of both methods, thereby improving robustness against indicator correlation and enhancing discrimination power among alternatives. Although GRA-TOPSIS has been effectively applied in environmental management, infrastructure assessment, and sustainable development studies, its application in metro accessibility evaluation remains limited. To fill this gap, this study proposes a novel CWM-GRA-TOPSIS framework that integrates a multi-dimensional indicator system, a combined weighting method (CWM), and the GRA-TOPSIS evaluation technique. This framework contributes methodologically by enhancing robustness and stability and contributes practically by providing actionable insights for improving metro accessibility and supporting sustainable urban transport planning.

3. Materials and Methods

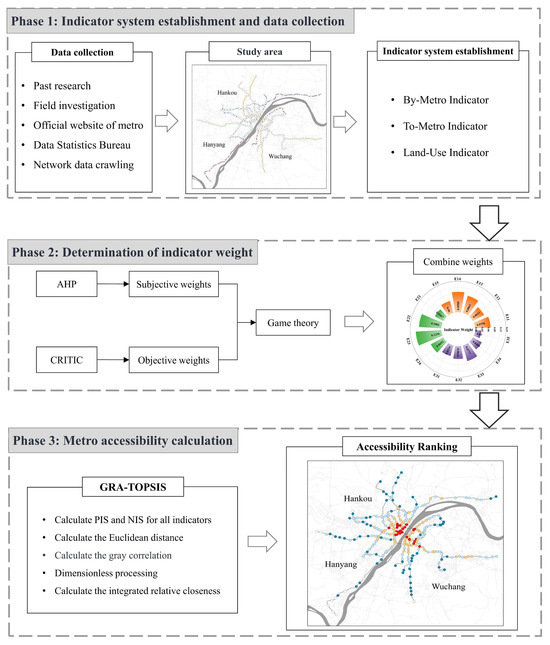

To comprehensively evaluate metro station accessibility, this study constructs an integrated CWM–GRA–TOPSIS model, combining a combined weighting method (CWM) with a hybrid evaluation technique (GRA-TOPSIS). This framework provides a systematic and reliable approach to quantify metro accessibility and offers valuable insights for promoting sustainable urban transit development. As illustrated in Figure 1, the methodological framework is implemented in three consecutive phases: indicator system establishment, weight determination, and accessibility evaluation.

Figure 1.

Flowchart of the proposed CWM-GRA-TOPSIS methodology.

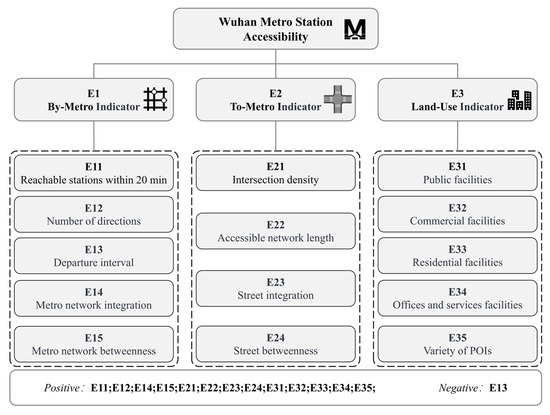

3.1. Phase I: Indicator System Establishment

A well-structured indicator system is essential for accurately assessing metro accessibility, as it determines the comprehensiveness and interpretability of the evaluation results. In line with Wu (2023) [26], this study adopts a multi-dimensional indicator framework consisting of 14 s-level indicators, structured around three core dimensions: by-metro accessibility (E1), to-metro accessibility (E2), and land use accessibility (E3) (Figure 2). Together, these dimensions capture the complete travel chain from origins to destinations and reflect the interaction between transportation systems and the urban environment.

Figure 2.

Framework of metrics for assessing the accessibility of city metro stations.

By-metro index (E1) relates to the connectivity, efficiency, and structure of the metro network, describing how conveniently passengers can travel within the metro system. It includes five sub-indicators: reachable stations within 20 min (E11), number of directions (E12), departure interval (E13), metro network integration (E14) and metro network betweenness (E15). E14 refers to the average shortest path from a station to all other stations within the network, reflecting metro network integration. E15 is the proportion of stations passing through the shortest path between any two stations, capturing node prominence.

To-metro index (E2) focuses on walking accessibility from surrounding areas to metro stations, focusing on the pedestrian network and spatial connectivity within the metro catchment area (MCA). It comprises four sub-indicators: intersection density (E21), accessible network length (E22), street integration (E23) and street betweenness (E24). E23 measures the overall centrality of each street MCA. E24 reflects the travel frequency of each road within the metro catchment area as the shortest path.

Land use index (E3) relates to availability and diversity of functional opportunities around each metro station, highlighting the integration of transportation and urban land use. It encompasses five sub-indicators: public facilities (E31), commercial facilities (E32), residential facilities (E33), offices and services facilities (E34) and variety of Point of Interest, POI (E35).

A detailed definition, data source, and calculation method for all indicators are provided in Table 1, ensuring transparency and comparability across dimensions.

Table 1.

Explanation of the indicator system.

3.2. Phase II: Calculating the Weights for Indicators

The reliability of evaluation outcomes heavily depends on the indicator weights. To balance expert judgment and data-driven evidence, this study adopts the CWM that integrates subjective obtained via AHP and objective weights calculated using the CRITIC method. This hybrid approach mitigates the limitations of relying on a single weighting scheme, providing a more robust and nuanced assessment of metro station accessibility.

3.2.1. Subjective Weights via AHP

As a structured multicriteria decision-making tool, AHP has been widely applied in transportation planning and urban evaluation due to its logical framework and ability to incorporate expert knowledge. It simplifies the multi-criteria evaluation process by decomposing complex decision-making problems into a hierarchical structure comprising criteria, sub-criteria and alternative options.

Following Wu (2023) [26], 25 experts specializing in urban planning and transportation performed pairwise comparisons of indicators. After conducting consistency testing (Consistency Ratio, CR ≤ 0.1), the normalized principal eigenvector was extracted to produces the subjective weights (W1), reflecting expert judgment on the importance of each indicator.

3.2.2. Objective Weights via CRITIC

The CRITIC method determines objective weights by simultaneously considering the variability of each indicator and the degree of conflict or correlation between indicators. It reduces redundancy and mitigates the influence of highly correlated indicators, ensuring that each indicator contributes meaningfully to the evaluation. The CRITIC calculation process can be broken down into several stages as described below:

Step 1. Establish the original assessment matrix.

where i = 1, 2,⋯, n; and j = 1, 2,⋯, m.

Step 2. Normalize the original evaluation matrix. The initial matrix undergoes dimensionless processing using the Min-Max standardization method.

Step 3. Calculate the coefficient of variation using standard deviation of each indicator.

Step 4. Construct the correlation coefficient matrix R = (rjk)mxm.

Step 5. Calculate the information measure of each indicator.

where Cj indicates the role of the jth evaluation indicator in the evaluation indicator system, the larger the value, the greater the weight. The formula for calculating the amount of information Cj is as shown below.

Step 6. Calculate the objective weights.

3.2.3. Combinatorial Weights Based on Game Theory

While AHP captures expert insights, it is inherently subjective, whereas CRITIC relies entirely on data and may neglect context-specific relevance. To reconcile these perspectives, game theory is employed to optimally integrate subjective and objective weights, generating a final combined weight vector (W) through an equilibrium process. The procedure involves:

Step 1. Use the following formula to calculate the combination weight.

where W represents the combined weight vector and α1, α2 are the combined coefficients of subjective and objective weights.

Step 2. Adjust the linear combination coefficients to reduce the difference between the subjective and objective weights and the combination coefficients.

Step 3. Transform the linear equations into optimized first derivative condition by the following formula:

Step 4. Calculate the final combined weights.

3.3. Phase III: Metro Accessibility Calculation via GRA-TOPSIS

Once the weightings for each criterion have been determined, the next step is to rank the alternative options. To achieve this, this study employs the TOPSIS method, a widely recognized multi-criteria decision-making (MCDM) approach, valued for its simplicity and ability to provide a comprehensive assessment of alternatives. The core principle of TOPSIS is to rank alternatives by evaluating their distances to the positive ideal solution (PIS) and the negative ideal solution (NIS). Alternatives closer to the PIS and farther from the NIS are considered superior. However, TOPSIS alone may fail when alternatives are close to both PIS and NIS or when indicator curves exhibit strong correlations.

To address these limitations, we combine TOPSIS with GRA. GRA evaluates the similarity of indicator patterns by comparing the geometric shapes of their curves, capturing interrelationships and trends that conventional Euclidean distance measures may overlook. By combining TOPSIS with GRA, the GRA–TOPSIS method enhances robustness, reduces the influence of multicollinearity, and improves the discrimination among alternatives. The detailed steps for calculating the GRA-TOPSIS method are described below.

Step 1. Construct a matrix of weighted criteria. The normalized evaluation matrix X is multiplied with the combined weight vector w determined in Section 3.2.3 to form a weighted evaluation matrix .

Step 2. Based on a weighted standard assessment matrix, calculate all indices of PIS and NIS.

In the formula, J represents the positive indicator and J’ represents the negative indicator.

Step 3. Determine the Euclidean distance between each assessment target and both PIS and NIS.

In the formula, denotes the Euclidean distance from the assessment target to the PIS, where a smaller value is better. denotes the Euclidean distance from the assessment target to the NIS, where a larger value is more beneficial.

Step 4. Determine the grey correlation coefficient between each assessment target in relation to PIS or NIS.

In the formula, represents the grey correlation coefficient between the assessment target and PIS. represents the grey correlation coefficient between the assessment target and NIS. ξ represents the resolution coefficient, which is located in the interval of (0, 1), and ξ is usually taken as the value of 0.5 based on experience.

Step 5. The Euclidean distance and grey correlation were dimensionalized.

The assessment target is closer to the PIS with larger and , but further away with larger and .

Step 6. Determine the comprehensive relative proximity.

In the formula, denotes the comprehensive relative proximity using Euclidean distance and grey correlation degree, indicating similarity and distinction in the relative location and form between each assessment target and the PIS. The assessment target is considered better when it has a higher value in the comprehensive relative proximity ranking. Decision makers can determine the values of and according to the specific program, and the values of and are taken as 0.5 in this study.

3.4. Study Area and DATA Collection

3.4.1. Study Area

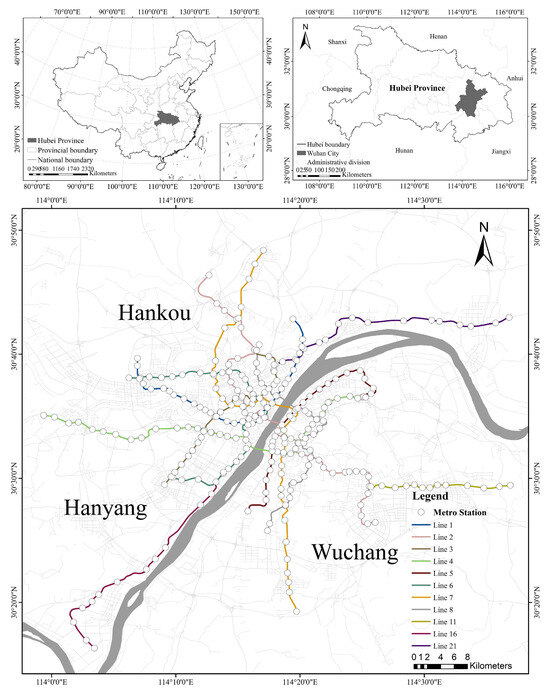

Wuhan, as the provincial capital of Hubei, is a polycentric metropolis composed of three main urban areas: Wuchang, Hankou, and Hanyang. With a population exceeding 12 million and rapid urban expansion, the city faces significant mobility challenges, including traffic congestion, air pollution, and a high private car modal share. While private cars account for a substantial portion of trips, public transit, walking, and cycling collectively serve the majority of urban journeys, reflecting both infrastructural constraints and evolving travel behaviors.

In response to mobility challenges, local and national authorities have set ambitious sustainable mobility objectives, aiming to reduce greenhouse gas emissions, enhance public transport usage, and promote active modes such as walking and cycling. Wuhan’s municipal planning documents emphasize the development of a transit-oriented urban structure, integrating metro lines with bus networks, pedestrian pathways, and cycling facilities to encourage a modal shift from private vehicles.

Wuhan was the seventh major city in China to establish a rapid transit system, initiating its long-term metro construction program in the early 1990s, with the first metro line opening in July 2004 [37]. Since then, the city’s rail transit system has undergone significant expansion, evolving from tree-like lines to a more efficient ring-like system [38]. By 2023, Wuhan’s metro network consists of 11 operational lines (Lines 1–8, 11, 16, 21), covering 460.4 km and 253 stations, serving over 3 million passengers daily, as shown in Figure 3. Rapid network expansion and urban growth have made accessibility evaluation increasingly important for sustainable transportation planning.

Figure 3.

Map of the study area.

Collectively, Wuhan’s mobility patterns, policy objectives, and infrastructure developments provide a representative case for evaluating metro station accessibility, enabling insights applicable across diverse urban contexts.

3.4.2. Data Collection

To quantitatively evaluate metro station accessibility, this study collected multi-source urban data encompassing network, spatial, and land use attributes. The metro operational data, such as station locations, line connections, service frequency, travel times, and transfer information, were obtained from official Wuhan Metro Group datasets and Gaode Map. The geographic and road network data, such as street networks, pedestrian pathways, and intersection densities, were collected from OpenStreetMap and local urban planning bureaus to assess walking distances and pedestrian connectivity. The land use data, such as employment density, commercial distributions, and land use mix, were derived from Gaode Map, providing insights into the surrounding urban environment of each station.

All datasets were projected onto a unified coordinate system and clipped to the coverage area of the metro network. Considering that some indicators are calculated within a specific spatial range, in line with Wu (2023) [26], the metro catchment area (MCA) is defined as an area with a radius of 600 m centered on the metro station using a simple Euclidean distance, reflecting pedestrian travel behavior and domestic planning practices. For the data within the overlapping area, the statistics are directly copied for each MCA involved without division. Indicators were then standardized using min-max scaling to eliminate unit differences and facilitate comparison. Additionally, correlation matrices were computed to identify multicollinearity among indicators, ensuring that interdependent factors do not distort subsequent GRA-TOPSIS accessibility rankings.

4. Results

4.1. Assigning Weights to Indicators

4.1.1. Determine the Subjective Weight of the Indicators

The subjective weights were calculated by the AHP method, and the judgment matrix was obtained by using SPSSPRO software (https://www.spsspro.com/). For the first-level indicators, the same weight is assigned when evaluating the accessibility of metro stations. For the second-level indicators, the relative importance of each indicator is evaluated through pairwise comparisons. The final subjective weights are then calculated, with the results presented in Table 2. Analysis of the subjective weight data reveals that the highest subjective weight is assigned to street integration (E23), while the lowest is given to variety of POIs (E35).

Table 2.

The subjective weight calculated by AHP.

4.1.2. Determine the Objective WEIGHT of the Indicators

Using the calculation formula outlined in Section 3.2.2, the objective weights are obtained as shown in Table 3. Among these, departure interval (E13) has the highest objective weight, while residential facilities (E33) have the lowest.

Table 3.

The objective weight calculated by CRITIC.

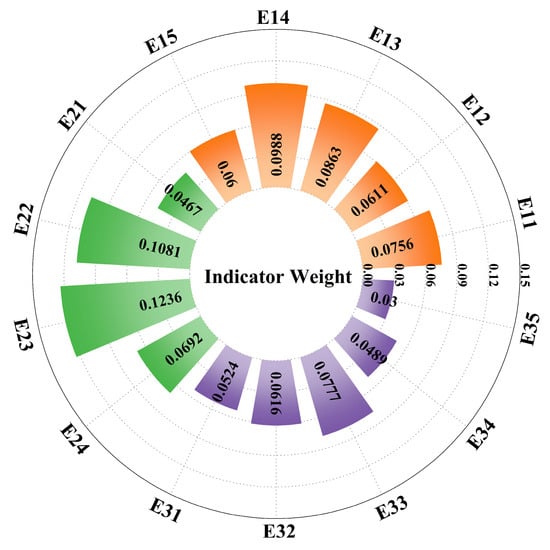

4.1.3. Determine the Combined Indicator Weights

According to the formula, the optimal weight coefficients is obtained as α1 = 0.5336, α2 = 0.5690. After standardization, these values become β1 = 0.4839, β2 = 0.5161. The combined weights for the 14 indicators are presented in Figure 4, the weight value of the street integration (E23) indicator is the largest, while the variety of POIs (E35) indicator has the lowest combined weight. Furthermore, the subjective and objective weights for the departure interval (E13) and residential facilities (E33) indicators show significant differences, indicating that relying solely on subjective or objective weights may lead to biased assessment results. In contrast, using the combined weights method helps mitigate this issue.

Figure 4.

Combination weight of evaluation indicator.

4.2. Calculating the Metro Accessibility by GRA-TOPSIS

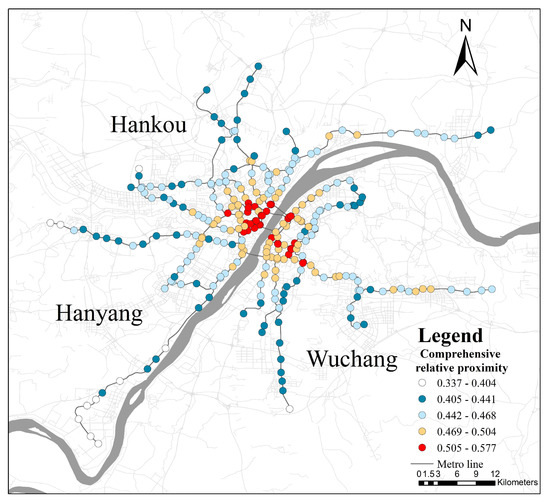

The GRA-TOPSIS was applied to evaluate the accessibility of various metro stations in Wuhan. After analyzing the survey results and data, the weighted criterion evaluation matrix Z was calculated using Equation (14). Next, calculate the Euclidean distance and grey correlation degree between each assessment target and PIS and NIS. These values were then normalized to determine the integrated relative proximity. Figure 5 presents the detailed results of the evaluation.

Figure 5.

The ranking results of Wuhan metro station accessibility.

The spatial distribution map of the comprehensive ranking results for Wuhan’s metro system highlights clear geographical disparities in metro station accessibility. As shown in Figure 5, there is a clear “high-middle-low” spatial distribution as the accessibility of metro stations diminishes gradually from the city center towards the periphery. Metro stations in the city’s core, particularly those in areas like the Jianghan Road business district, exhibit higher accessibility indices. This is attributed to factors such as a well-structured street network, high-intensity land use, and strategic locations at the intersections of multiple metro lines, offering more transfer options and enhancing overall accessibility.

In contrast, suburban metro stations tend to have lower accessibility ranking. This is primarily due to less frequent metro services in these areas and the relatively lower levels of development and population density. Suburban stations are often terminal stations with limited surrounding commercial and public facilities. Consequently, passengers in these areas typically face longer walking distances or greater spatial barriers to access metro stations or their destinations. The least accessible station is Qinglongshan Ditiexiaozhen Station, located on the edge of the city and serving as a terminal station.

Wuhan’s unique urban spatial structure, bounded by the Yangtze River and Han River, leads to significant differences in metro accessibility across districts. The accessibility of Wuhan metro system follows a clear multi-center structure, closely aligned with this spatial division. Hankou, as the commercial and transportation hub of Wuhan, has the highest number of metro stations with high accessibility values. Jianghan Road Station ranks at the top, followed by Dazhi Road Station, Xunlimen Station, Xianggang Road Station and Zhongshan Park Station. These top-ranked stations are all located in the core business district of Hankou, a cluster characterized by highly accessible stations, thanks to the district’s well-developed metro network, efficient street network, and dense concentration of surrounding facilities. In contrast, Hanyang has the fewest and lowest-density metro stations with low accessibility, resulting in the district’s lowest overall accessibility ranking. This can be attributed to Hanyang’s slower pace of urban development, including infrastructure, commercial growth, and population expansion. The stations with high accessibility in Wuchang are more dispersed compared to Hankou, where stations are concentrated in central areas. In Wuchang, areas around Jiedaokou Station, Xujiapeng Station, and Hongshan Square Station serve as key accessibility hubs, forming the central points of the region.

Examining accessibility along metro lines, a general trend is observed where central sections exhibit higher accessibility than peripheral sections, particularly in lines passing through the city center, such as Lines 2 and 5. However, this trend is not universal. The Guanggu area, where Lines 2 and 11 intersect, represents an emerging secondary urban center focused on industry and higher education. This area combines major urban functions and a dense population, generating high-frequency travel demand. The targeted densification of metro lines in this secondary center has mitigated the traditional decline in accessibility with distance from the city core, establishing a transportation hub that supports Wuhan’s multi-center urban development.

In the southern region, the newly constructed Line 16 currently exhibits relatively low accessibility compared with other lines in the same area. This is primarily due to a mismatch between the line’s service area and its stage of urban development. Line 16 connects distant suburban areas with the main urban center; however, much of the surrounding area remains undeveloped or under construction, lacking the stable passenger flows typically generated by mature residential or university districts, and commercial clusters have yet to form. Moreover, supporting pedestrian connections along the line are still being improved, further limiting access. Nevertheless, this low accessibility is expected to be temporary. With future population growth, industrial development, and enhancement of supporting facilities along the line, accessibility levels are anticipated to rise, positioning Line 16 as a key transportation link for the development of southern suburban areas.

5. Discussion and Conclusions

5.1. The Accessibility of Wuhan’s Rail Transit

Evaluating the accessibility of metro stations is essential for optimizing urban planning and enhancing travel convenience for residents. Such evaluations provide decision-makers with critical insights to make constructive recommendations and significantly influence residents’ choice of transportation modes. By analyzing metro accessibility, urban planners can access vital data on the operational efficiency of urban transportation networks, forming the basis for informed and effective planning strategies.

This study proposes a novel CWM-GRA-TOPSIS method for assessing metro accessibility. By leveraging a multi-criteria decision-making approach, this method effectively synthesizes the complex attributes of metro stations, providing a more accurate and comprehensive evaluation of metro accessibility. Firstly, the evaluation indicator system is established using three first-level indicators: By-metro accessibility, To-metro accessibility, and land use accessibility, which are further divided into 14 s-level indicators for a more detailed analysis. Secondly, Subjective weights are determined using the AHP method and objective weights via the CRITIC method. A combination of these weights is derived using Game Theory, ensuring both the interrelation among indicators and the inherent properties of the data were considered. Thirdly, the GRA-TOPSIS approach is applied to assess and rank metro station accessibility

Empirical application in the Wuhan Metro system demonstrates clear spatial differentiation in accessibility. The comprehensive accessibility index ranges from 0.337 to 0.577, exhibiting a gradient of high-medium-low levels that generally decrease from the city center toward peripheral areas. Among Wuhan’s three core districts, Hankou exhibits the highest proportion of highly accessible stations. Jianghan Road Station, at the intersection of Lines 2 and 6, ranks first with an accessibility index of 0.577, benefiting from dense infrastructure, a well-integrated metro network, and a high concentration of commercial, cultural, and public facilities. In contrast, stations in suburban districts, such as Lines 4 and 16 in Hanyang, display lower accessibility due to slower urban development, sparse infrastructure, and limited metro coverage. These disparities highlight the need for targeted interventions to improve the accessibility of suburban and peripheral areas, supporting balanced urban growth and transit-oriented development.

5.2. Recommendations

According to the study’s results, the following proposals are suggested to enhance metro station accessibility in Wuhan:

- (1)

- Optimize station layout. New station locations should align with current travel demand and urban development goals, while also accommodating future population growth and spatial planning trends. This approach ensures sustainable city expansion and transportation efficiency.

- (2)

- Improve station connection. Efficiently plan and establish complementary public transportation services, such as buses and cabs, around metro stations. Seamless connectivity and optimized transfer routes can minimize passenger walking distances, improving overall accessibility.

- (3)

- Improve station surroundings. Improve the walking environment near metro stations and invest in infrastructure development around these areas. Planning for commercial districts, offices, and cultural facilities near stations can expand their service scope. Establishing a well-integrated pedestrian system further improves accessibility for passengers.

- (4)

- Flexible adjustment of operation frequency and time. Dynamic adjustments to train frequency and schedules, informed by real-time passenger flow monitoring and demand analysis, can better accommodate variations in weekday, weekend, and time-specific usage.

- (5)

- Regular assessment and updates. The data should be updated periodically to reflect changing urban dynamics and residents’ needs. This ensures the metro system remains optimized and continues to meet the evolving demands of the city.

5.3. Limitations

While this study provides valuable insights and practical support for the comprehensive evaluation of metro station accessibility, it has certain limitations. First, the metro station accessibility evaluation index system proposed in this paper is not fully optimized and may need adjustment based on specific contexts. For instance, the departure interval time (E13) can vary significantly between peak and off-peak hours, and using a single average value may not accurately reflect the service level throughout the entire operation period. Second, the research fails to adequately consider the integration of metro systems with other transportation modes within a multi-modal transportation framework. Seamless connections between metro systems and other public transportation options—such as buses, bicycles, and cabs—are crucial for enhancing overall accessibility but are not thoroughly addressed in the evaluation metrics. Future research should focus on improving the theoretical framework and refining the evaluation index system to incorporate evolving urban development patterns and multi-modal integration. This would provide more robust guidance for optimizing metro system operations and urban transportation planning.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Tao Wu and Ye Zhou; methodology, Tao Wu; software, Yichong Shi; validation, Yichong Shi and Zhihan Chen; formal analysis, Yichong Shi; investigation, Zhihan Chen; resources, Tao Wu and Ye Zhou; data curation, Zhihan Chen; writing—original draft preparation, Yichong Shi; writing—review & editing, Tao Wu; visualization, Yichong Shi; supervision, Tao Wu; project administration, Ye Zhou; funding acquisition, Tao Wu and Ye Zhou. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Department of Education of Hubei Province, grant number 22Q025. Zhejiang Provincial Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number LQN25D010001. And National Natural Science Foundation of China, grant number 42501512.

Data Availability Statement

Wuhan metro operation data from the official government website (https://www.wuhanrt.com/, accessed on 17 December 2023). The POI data for Wuhan city comes from Gaode Map (https://lbs.amap.com/, accessed on 17 December 2023). Street network data from Open Street Map (OSM) (https://download.geofabrik.de/, accessed on 17 December 2023).

Acknowledgments

Thank you to the school, the funding agencies and the colleagues who participated in the research. During the completion of this research, everyone gave us selfless help and valuable suggestions. We extend our heartfelt gratitude to all those who contributed to this research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Karjalainen, L.E.; Juhola, S. Urban transportation sustainability assessments: A systematic review of literature. Transp. Rev. 2021, 41, 659–684. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, L.; Cui, M. How subway network affects transit accessibility and equity: A case study of Xi’an metropolitan area. J. Transp. Geogr. 2023, 108, 103556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansson, J. Replacing regional bus services with rail: Changes in rural public transport patronage in and around villages. Transp. Policy 2021, 101, 89–99. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malekzadeh, A. A review of transit accessibility models: Challenges in developing transit accessibility models. Int. J. Sustain. Transp. 2019, 14, 733–748. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheng, J.; Bertolini, L.; Clercq, F.L.; Kapoen, L. Understanding urban networks: Comparing a node-, a density- and an accessibility-based view. Cities 2013, 31, 165–176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Feng, J.; Dijst, M.; Prillwitz, J.; Wissink, B. Travel Time and Distance in International Perspective: A Comparison between Nanjing (China) and the Randstad (The Netherlands). Urban Stud. 2013, 50, 2993–3010. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Krygsman, S. Multimodal public transport: An analysis of travel time elements and the interconnectivity ratio. Transp. Policy 2004, 11, 265–275. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, A.J. Assessing walking accessibility to public transport stops in Budapest. Sustain. Futures 2025, 10, 101221. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, M.; Mao, J.; Xi, Y. Research on entropy weight multiple criteria decision-making evaluation of metro network vulnerability. Int. Trans. Oper. Res. 2024, 31, 979–1003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, W.; Yan, W.; Chen, L.; Wei, H.; Gan, S. Developing a TOD assessment model based on node–place–ecology for suburban areas of metropolitan cities: A case in Odawara. Environ. Plan. B Urban Anal. City Sci. 2024, 51, 839–853. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tüysüz, N.; Kahraman, C. An integrated picture fuzzy Z-AHP & TOPSIS methodology: Application to solar panel selection. Appl. Soft Comput. 2023, 149, 110951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoon, K.P.; Kim, W.K. The behavioral TOPSIS. Expert Syst. Appl. 2017, 89, 266–272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Huang, D.; You, Q.; Kang, J.; Shi, M.; Lang, X. Evaluation of emergency evacuation capacity of urban metro stations based on combined weights and TOPSIS-GRA method in intuitive fuzzy environment. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2023, 95, 103864. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, S.; Yang, Y.; Cao, Y.; Xie, N. A summary on the research of GRA models. Grey Syst. Theory Appl. 2013, 3, 7–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hansen, W.G. How Accessibility Shapes Land Use. J. Am. Inst. Plan. 1959, 25, 73–76. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hägerstraand, T. WHAT ABOUT PEOPLE IN REGIONAL SCIENCE? Pap. Reg. Sci. 1970, 24, 7–21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yoshida, N.; Deichmann, U. Measurement of Accessibility and Its Applications. J. Infrastruct. Dev. 2009, 1, 1–16. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Morris, J.M.; Dumble, P.L.; Wigan, M.R. Accessibility indicators for transport planning. Transp. Res. Part A Gen. 1979, 13, 91–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huynh, N.; Barthelemy, J. A comparative study of topological analysis and temporal network analysis of a public transport system. Int. J. Transp. Sci. Technol. 2022, 11, 392–405. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moniruzzaman, M. Accessibility to transit, by transit, and mode share: Application of a logistic model with spatial filters. J. Transp. Geogr. 2012, 24, 198–205. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bivina, G.R. Walk Accessibility to Metro Stations: An analysis based on Meso- or Micro-scale Built Environment Factors. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2020, 55, 102047. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, W.; Zhou, J.; Yang, L.; Li, L. The implications of high-speed rail for Chinese cities: Connectivity and accessibility. Transp. Res. Part A Policy Pract. 2018, 116, 308–326. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, J.; Zhu, L.; Duan, Y.; Zhou, J.; Ma, H. Developing metro-based accessibility: Three aspects of China’s Rail+Property practice. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2020, 81, 102288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kelobonye, K. Relative accessibility analysis for key land uses: A spatial equity perspective. J. Transp. Geogr. 2019, 75, 82–93. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, K. Multi-method analysis of urban green space accessibility: Influences of land use, greenery types, and individual characteristics factors. Urban For. Urban Green. 2024, 96, 128366. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, T.; Li, M.; Zhou, Y. Measuring Metro Accessibility: An Exploratory Study of Wuhan Based on Multi-Source Urban Data. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2023, 12, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Keshavarz-Ghorabaee, M.; Amiri, M.; Zavadskas, E.K.; Turskis, Z.; Antuchevičienė, J. MCDM approaches for evaluating urban and public transportation systems: A short review of recent studies. Transport 2022, 37, 411–425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jato-Espino, D.; Castillo-Lopez, E.; Rodriguez-Hernandez, J.; Canteras-Jordana, J.C. A review of application of multi-criteria decision making methods in construction. Autom. Constr. 2014, 45, 151–162. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chai, N.; Zhou, W.; Hu, X. Safety evaluation of urban rail transit operation considering uncertainty and risk preference: A case study in China. Transp. Policy 2022, 125, 267–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Liu, L. Improving eco-efficiency in coal mining area for sustainability development: An emergy and super-efficiency SBM-DEA with undesirable output. J. Clean. Prod. 2022, 339, 130701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Du, X.; Wang, Y.; Chen, F. Evaluation of coal-resource-based cities transformation based on CRITIC-TOPSIS model. Sustain. Cities Soc. 2024, 103, 105271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J. Urban flooding risk assessment based on GIS- game theory combination weight: A case study of Zhengzhou City. Int. J. Disaster Risk Reduct. 2022, 77, 103080. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, F. Systematic framework for sustainable urban road alignment planning. Transp. Res. Part D Transp. Environ. 2023, 120, 103796. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.-W. Research on the operation safety evaluation of urban rail stations based on the improved TOPSIS method and entropy weight method. J. Rail Transp. Plan. Manag. 2021, 20, 100262. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, D. A resilience evaluation method for a combined regional agricultural water and soil resource system based on Weighted Mahalanobis distance and a Gray-TOPSIS model. J. Clean. Prod. 2019, 229, 667–679. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X. Evaluating water resource carrying capacity in Pearl River-West River economic Belt based on portfolio weights and GRA-TOPSIS-CCDM. Ecol. Indic. 2024, 161, 111942. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, L.; Li, Z.; Zhang, Z. City profile: Wuhan 2004–2020. Cities 2022, 123, 103585. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, J.; Cui, C.; Qi, J.; Ruan, Z.; Dai, Q.; Yang, H. The Evolvement of Rail Transit Network Structure and Impact on Travel Characteristics: A Case Study of Wuhan. ISPRS Int. J. Geo-Inf. 2021, 10, 789. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Published by MDPI on behalf of the International Society for Photogrammetry and Remote Sensing. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).