Abstract

Accurate volumetric modeling of indoor spaces is essential for emerging 3D cadastral systems, yet existing workflows often rely on manual intervention or produce surface-only models, limiting precision and scalability. This study proposes and validates an integrated, largely automated workflow (named VERTICAL) that converts classified indoor point clouds into topologically consistent 3D solids served as materials for land surveyor’s cadastral analysis. The approach sequentially combines RANSAC-based plane detection, polygonal mesh reconstruction, mesh optimization stage that merges coplanar faces, repairs non-manifold edges, and regularizes boundaries and planar faces prior to CAD-based solid generation, ensuring closed and geometrically valid solids. These modules are linked through a modular prototype (called P2M) with a web-based interface and parameterized batch processing. The workflow was tested on two condominium datasets representing a range of spatial complexities, from simple orthogonal rooms to irregular interiors with multiple ceiling levels, sloped roofs, and internal columns. Qualitative evaluation ensured visual plausibility, while quantitative assessment against survey-grade reference models measured geometric fidelity. Across eight representative rooms, models meeting qualitative criteria achieved accuracies exceeding 97% for key metrics including surface area, volume, and ceiling geometry, with a height RMSE around 0.01 m. Compared with existing automated modeling solutions, the proposed workflow has the ability of dealing with complex geometries and has comparable accuracy results. These results demonstrate the workflow’s capability to produce topologically consistent solids with high geometric accuracy, supporting both boundary delineation and volume calculation. The modular, interoperable design enables integration with CAD environments, offering a practical pathway toward an automated and reliable core of 3D modeling for cadastre applications.

1. Introduction

The rapid growth of urban populations and the increasing complexity of land use in modern cities have placed significant pressure on city management [1]. As cities expand both vertically and horizontally, the need for precise and efficient management of land ownership, property boundaries, and land use rights has become more urgent [2]. In this context, cadastral systems play a fundamental role in supporting urban planning, real estate transactions, property taxation, and legal land administration [3]. Traditional two-dimensional (2D) cadastral systems, which rely on paper records or digital 2D maps to represent property boundaries and ownership, have become insufficient for addressing the spatial complexity of vertical developments [4,5]. In situations involving multi-level buildings, co-ownership, or underground constructions, 2D representations are often inadequate to capture the legal and spatial intricacies of real property units [6,7]. The shift from traditional two-dimensional systems to three-dimensional (3D) cadastre represents an important step forward. However, the transition brings significant challenges, particularly in data acquisition and modeling [8].

Under these circumstances, point cloud data, particularly from Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) or photogrammetry, has become a valuable source for 3D reconstruction of buildings, land parcels, and infrastructure, offering high-resolution spatial measurements of the built environment, including interior spaces [9,10,11]. These data can be transformed into 3D meshes and solids, providing a more accurate representation of land and buildings than traditional mapping methods [12]. Despite the advantages, the process of converting raw point clouds into usable 3D models is still largely manual, and its use in cadastral applications remains limited [13,14]. Existing workflows typically involve multiple steps of data cleaning, segmentation, and model fitting, all of which require substantial human effort [13]. Land surveyors point to the disconnect between the efficiency of modern LiDAR surveys and the labor-intensive process of manually drafting plans within point clouds [15]. Despite the richness of point cloud datasets, current Computer Aided Design (CAD)-based and Geographical Information Science (GIS)-based tools do not yet provide adequate support for the automatic derivation of 3D parcels that comply with cadastral and legal requirements from unstructured 3D scans [16]. The challenge is particularly acute for indoor environments, where clutter, occlusions, and variable geometry complicate the extraction of clear structural boundaries. Without automation, manual procedures are primarily constrained by time and labor intensity rather than by geometric precision. In contrast, the key challenge of automated approaches is to achieve volumetric representations that meet cadastral precision requirements [17]. This hinders the operational adoption of 3D cadastre, especially where cadastral lots must be defined by measurable volumes that correspond to physical or legal divisions of space [18].

To support 3D cadastre, the generation of precise 3D volumetric models is essential. These models must be geometrically accurate (typically at the centimeter level for indoor environments) and topologically sound, capable of representing enclosed volumes that correspond to real-world ownership units. However, existing software and technical solutions either focus merely on 2D or 3D drafting or are limited to point cloud processing without the ability to produce usable 3D solids. Moreover, there is currently no platform that offers automated processing chains that can transform raw indoor point cloud data into cadastral-grade 3D solids while limiting the need of manual intervention [15]. In other cases, some solutions fail to produce models with the geometric accuracy required for cadastral applications [19]. In practice, subtle ceiling height variations below a few centimeters are often beyond the resolution that automated approaches can reliably capture. Therefore, the automated construction of volumetric 3D solids from indoor point clouds requires further investigation.

Beyond cadastral applications, numerous studies have demonstrated the potential of automated 3D reconstruction from point clouds in various domains of the built environment. For example, Nikoohemat et al. [20] reconstructed watertight indoor models for disaster management. Jung and Kim [21] developed an automated pipeline for as-built BIM generation from indoor scans. Poux et al. [22] present an integrated 3D semantic reconstruction framework for modeling indoor space and furniture. Wang et al. [23] automatically extracting building geometries for sustainability applications. In cultural heritage, Grilli et al. [24] report robust classification or reconstruction procedures for complex assets from point clouds. Although these studies are not designed for cadastral registration, they demonstrate mature techniques—semantic segmentation, parametric/volumetric modeling, and topology control—that can be adapted to the enclosure and accuracy requirements of 3D cadastral applications.

Despite these advances in related domains, their direct application to cadastral modeling remains limited. Given the limitations mentioned in previous paragraphs, this research is founded on the hypothesis that an automated workflow can be developed to convert indoor point clouds into 3D volumetric solids with sufficient accuracy and completeness to support cadastral modeling. The primary objective is to design an integrated and automated volumetric modeling workflow able to convert indoor point clouds into 3D solid models suitable for cadastre applications. This workflow combines key techniques in point cloud segmentation and classification, room surface reconstruction, and solid modeling. By emphasizing automation, the proposed approach aims to significantly reduce the time and effort required to generate volumetric models, making the process more efficient. As part of this research, a modular web-based prototype has been developed to simplify interaction with specific parameters involved at different steps of the workflow and to test this using specific indoor LiDAR point cloud datasets, provided by a firm of professional land surveyors “GPLC arpenteurs-géomètres inc.” operating in the province of Quebec in Canada. Quantitative and qualitative assessments have been conducted to validate the accuracy and completeness of the final 3D models according to the requirements of GPLC.

The structure of this paper is as follows: Section 2 presents some related works about the automated 3D building reconstruction from point clouds. In Section 3, a description of our designed workflow is provided. Section 4 provides some explanations about the implementation of our prototype. Section 5 illustrates the experiments and the modeling results. Section 6 focuses on the qualitative and quantitative assessments to evaluate the accuracy of our workflow.

2. Three-Dimensional Building Reconstruction from Point Cloud

To investigate existing strategies and workflows for 3D modeling from point clouds, a systematic literature review was conducted. Based on major academic databases (Google Scholar, IEEE Xplore, ScienceDirect, and SpringerLink), 128 relevant publications and documentation from the last twenty years (2003–2024) are reviewed, encompassing both theoretical developments and practical applications. This review spans the evolution of technology and methods relevant to point cloud processing, segmentation, classification, 3D modeling, cadastre, and the Building Information Model (BIM). Moreover, papers after 2015 are chosen to ensure that the selected studies are reflective of current advancements, including breakthroughs in automation, the integration of artificial intelligence (AI) and machine learning, and the remarkable improvements in data acquisition technologies.

Existing approaches to automated point cloud modeling address both outdoor scenes [25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32] and indoor environments [33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40]. The automated methodologies for creating 3D geometric models from point cloud are generally classified as three categories, as noted by Abreu et al. [41]: planar primitive, where structures are modeled by fitting and arranging planar surfaces [12,35,42,43,44,45]; volumetric model, which uses solids (e.g., cuboids) to regularize and construct the building geometry [16,40,46,47,48,49,50]; and meshes-based, which generates a polygonal surfaces of the scene [33,34,41,45,51,52,53,54,55,56]. Representative works in each category, covering both large-scale outdoor modeling and detailed indoor reconstruction, are selected. Their workflows and methodological characteristics were investigated and analyzed, and their modeling results were illustrated accordingly.

In the following subsections, we briefly review works on 3D modeling from an outdoor perspective. After that, we discuss research works using indoor LiDAR data to automatically or semi-automatically produce 3D models. Finally, a presentation of relevant tools and technology is presented.

2.1. Outdoor 3D Modeling

Several automated pipelines focus on reconstructing building exteriors (urban scenes) from aerial or terrestrial data. These often leverage airborne LiDAR or Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) photogrammetry to capture roof shapes and building outlines at city scale.

Peters et al. [28] present the 3DBAG, an up-to-date dataset containing 3D building models of the Netherlands at multiple levels of detail (LoD): LoD1.2, LoD1.3, and LoD2.2. These 3D models are automatically generated from building data (polygons representing the outline of the building) and height data (elevation dataset acquired by airborne LiDAR).

Similarly, Pađen et al. [27] use a combination of building footprints and a point cloud to segment roof planes, create partitions, optimize planes, and finally assemble roof planes into 3D building models. The process is designed to handle large-scale data without manual intervention. The smallest elevation difference between adjacent roof planes could be 5–20 cm. Other outdoor-focused research emphasizes robust surface reconstruction from LiDAR. Zhou and Neumann [29] introduce a 2.5D dual contouring approach for reconstructing 3D building models from aerial LiDAR point clouds, which creates polygonal mesh models of buildings. Their method embeds point-and-normal pairs into a grid and extends the classic dual contouring algorithm to handle the 2.5D nature of ground and roof data. This fully automated workflow ensures reconstruction of building geometries while handling noise and preserving sharp features such as ridges and roof intersections.

Huang et al. [31] develop City3D, a fully automatic pipeline for reconstructing compact 3D building models from large-scale airborne point clouds using footprint polygons to extract buildings. It reconstructs two manifold and watertight 3D polygonal mesh models. It can deal with complex shapes with varying roof heights by detecting and meshing each distinct section. One limitation noted is that any building surfaces missing in the LiDAR data (for example, facade details not captured from above) are inferred as vertical walls, which may oversimplify those hidden parts.

Zeng et al. [57] use a deep neural network to apply shape grammar rules for procedurally reconstructing residential buildings [13,57].

Overall, outdoor modeling techniques achieve a high degree of automation and scalability. It demonstrates that large-scale outdoor point clouds can be converted into multi-LoD city models automatically. However, such methods rely on assumptions suited to external structures (e.g., that building footprints are known, or roofs are piecewise planar); they are operated under relatively constrained conditions (buildings as outward-facing solids) and typically generate surface models, which are not directly applicable to indoor scenes, where data characteristics and modeling requirements differ.

2.2. Indoor 3D Modeling

Indoor 3D modeling from point clouds has evolved through several methodological paradigms, reflecting trade-offs between geometric accuracy, automation, and topological completeness. Based on the 52 articles in our literature review, 15 articles were finally selected for detailed review according to their relevance to the research objectives (mapping/modeling the indoor space of a property; usage of terrestrial laser point cloud; modeling objects of reality: wall, floor, ceiling, beams; and so on). We extract and focus on the key elements: source of LiDAR data, features extracted (floor, wall, ceiling, etc.), geometry (feature) extraction approach, 3D modeling approach, percentage of automation, computational efficiency, quality metric (accuracy, completeness), and tools and software used. Following the categories of Abreu et al. [41], we organize the literature into planar-based, volumetric, and mesh-based (polygonal) reconstruction methods.

2.2.1. Planar-Based Reconstruction

Indoor environments present greater complexity due to clutter, occlusions, and the need for detailed, enclosed models. Some workflows start from extracting 2D floor plans from the 3D point cloud. Kim et al. [36], for example, describe a method for extracting geometric primitives, such as solid lines representing walls and boundaries, from unorganized 3D point cloud data. Their approach focuses on generating structured data that can be readily interpreted by CAD systems, intending to produce digital floor plans. While effective in simplifying raw spatial data, the method stops at the 2D floor plan level, lacking volumetric or three-dimensional reconstruction. Fang et al. [35] similarly focus on floorplan generation: they use a space partitioning approach to subdivide the point cloud into rooms and derive closed polygons for each room’s footprint, but additional steps are required to extrude or otherwise convert the floor plans into 3D wall models.

Moving from floor plans to 3D structures, several studies have tackled the segmentation and modeling of indoor structural elements in an automated or semi-automated way. Shi et al. [37] propose an automated approach that produces both 2D floor plans and a 3D semantic model of the interior from unstructured laser scan data. In their framework, major surfaces (floor, ceiling, walls) are first extracted. Then openings like doors and windows are detected within those surfaces. However, the approach does not address several complex challenges, including the reconstruction of irregular or non-planar wall surfaces, the modeling of in-room objects, or the inclusion of textural details.

Anagnostopoulos et al. [38,39] propose a semi-automated solution for extracting object boundaries of as-is models in the Industry Foundation Classes (IFC) format. They utilize adjacency relationships and geometric continuity to detect closed spaces (rooms) bounded by walls. In their implementation, only simple rectangular rooms (spaces enclosed by four orthogonal walls) could be reliably detected and modeled. Bassier et al. [51] present a method to automatically reconstruct consistent wall geometry from point clouds. They segment the raw point cloud into wall surfaces and then cluster and merge those segments to form complete wall planes, which are converted into “IfcWallStandardCase” entities (standard vertical walls with constant thickness). The authors note that while most wall boundaries are accurately reconstructed, there are “major deviations near wall detailing” due to the enforced abstraction for IFC compatibility. Thomson and Boehm [58] introduce an automated scan-to-BIM workflow. Their method segments the raw indoor point cloud into planar regions corresponding to floors, ceilings, and walls. They further subdivide these large surfaces by Euclidean clustering to isolate individual wall panels or ceiling patches, then reconstruct each as a simple geometry (often an extruded polygon) and assemble them into a BIM in IFC format. The whole process can be fully automated for a simple environment, and semi-automated for a cluttered space. They assume a predefined wall thickness for the extrusions, which must be set in advance and remain constant; this preset thickness may not reflect actual wall variations.

Budroni and Boehm [59] design an automated 3D modeling method for indoor environments from a point cloud. A plane sweeping algorithm is used for segmentation and detecting walls. Wall outlines are then extended vertically (extruded) to connect floor and ceiling, producing a simple 3D CAD model of the interior. Tamke et al. [60] take a more automated approach but with a constrained scope: they convert unstructured indoor scans into LoD1 BIMs. Fundamental geometric primitives such as points, lines, and polygons are extracted and used to build walls, floors, and openings in an IFC model. User interventions are not needed, but the simplicity of the output is notable: only primary features are modeled. Building elements such as columns, beams, and interior walls are not detected, and sloped ceilings, independent wall elements, and multi-story buildings are not supported.

Chauve et al. [61] presented a robust piecewise-planar reconstruction algorithm that performs an adaptive 3D space decomposition from planar primitives.

Overall, planar-based reconstruction is computationally efficient and conceptually simple. It is well suited for Manhattan-style rooms but limited in representing sloped or curved structures, multi-height ceilings, or free-form designs.

2.2.2. Volumetric Reconstruction

Volumetric approaches model enclosed volumes directly, producing watertight solids rather than open surfaces. These methods are especially relevant to applications such as navigation, simulation, or disaster management that require topologically consistent 3D spaces.

Nikoohemat et al. [20] develop a method for reconstructing 3D indoor models from point clouds for disaster management. Their approach focuses on extracting structural elements using surface a growing algorithm and adjacency graphs for room and wall segmentation, then applying parametric volumetric wall reconstruction and using regularized Boolean operations for closing solid indoor spaces. The result is a set of watertight 3D room models suitable for computing navigation paths. Auto classification and manual visual refinement are involved. Complicated features like sloping floors, staircases, and non-Manhattan layouts, to some degree, can be modeled, while windows, beams, and columns are simplified and not considered in this modeling pipeline.

Jung et al. [47] propose an automated as-built modeling of building interiors using point cloud data. This method includes point cloud segmentation into rooms, noise filtering, and extraction of floor–wall boundaries, followed by the reconstruction of volumetric walls using cuboid-based primitives with a fixed thickness. Openings such as doors and windows are also detected. While the workflow is highly automated, it assumes fixed wall thickness and vertical alignment and struggles with non-flat ceiling geometries, limiting its generalizability in complex buildings.

Xiao and Furukawa presents a 3D reconstruction and visualization system using a “inverse constructive solid geometry (CSG)” algorithm for reconstructing a scene with a CSG representation consisting of volumetric primitives [46].

Xiong et al. [12] present a method to automatically convert the raw 3D point data into semantically rich 3D building models. Voxelization and planar patch extraction are used. They also detect openings and label them as windows or doorways. A detailed surface model is produced, where each wall and structural element is delineated, but converting this surface-based representation model into a volumetric representation is not completed.

Macher et al. [62] propose a semi-automatic strategy for generating BIM from indoor point clouds. The approach focuses on extracting structural elements such as walls, floors, and ceilings to create accurate 3D BIM representations. They demonstrate this using FreeCAD (an open-source CAD platform), where the walls and slabs of an existing building were reconstructed with a combination of algorithmic detection and manual refinement.

Beyond walls and rooms, semantic enrichment and object-level modeling have been explored in some works. For instance, Poux et al. [22] integrate prior semantic knowledge to produce a hybrid 3D model that includes both architectural structure and furniture. They assume the point cloud has been pre-segmented or classified into semantic categories. Feature extraction is carried out automatically, identifying geometric features and object relationships. A 3D library (ModelNet10) is utilized for automatic recognition and fitting of furniture models. Model integration is achieved by combining individual elements into a cohesive 3D model with minimal manual intervention. Multi-LoDs geometric representations are built. This approach relies on having reliable semantic labels and an object library.

2.2.3. Mesh-Based Reconstruction

Beyond primitive-based or volumetric strategies, some approaches focus on reconstructing surfaces directly in the form of watertight polygonal meshes. These methods emphasize geometric completeness and visual realism. They are particularly suitable for irregular or non-orthogonal geometry. Nan and Wonka [63] present PolyFit, an approach for reconstructing polygonal surfaces directly from 3D point cloud data. This method utilizes Random Sample Consensus (RANSAC) to detect planar segments within the point cloud. It generates a set of face candidates by intersecting the extracted planar primitives. Then it selects an optimal subset of candidate faces through binary linear programming, ensuring the constructed model is manifold and watertight. Final constructed models are watertight polygonal surface models (meshes). The focus of this research is to address challenges in polygonal surface reconstruction, such as irregular boundaries, noisy data, and inconsistent geometries. It is applicable to both indoor and outdoor environments. It can handle irregular boundaries and non-rectangular structures. It is fully automated, requiring no manual intervention. Likewise, Wang et al. [55] introduce a method that couples RANSAC-based plane fitting with edge-aware meshing strategies to preserve sharp features and structural regularity, ultimately generating watertight surface meshes under polyhedral constraints. Such methods explicitly address the need for completeness in the model, ensuring no gaps in walls or roofs.

2.2.4. Discussion and Synthesis

In summary, planar approaches are efficient and structured but limited by geometric assumptions. It is suitable for orthogonal interior walls and it assumes flat and vertical walls. But it is poor for complex geometries. Volumetric methods generate watertight solids. It can guarantee topological closure and support semantic units. But they depend on simplified parametric models or require high computation. Mesh-based methods achieve high geometric fidelity. They can handle irregular shapes which is good for visualization. However, they remain surface-oriented, sometimes lack volume semantics, and may not be topologically closed.

These works span diverse methods ranging from parametric modeling and surface patch reconstruction to knowledge-driven semantic segmentation. The evolution over time has been toward greater automation, higher detail, and more integration of semantic information. Key technical challenges, however, remain apparent across the literature:

- Accurate segmentation of property components (rooms): Robustly partitioning the point cloud into meaningful components (individual walls, floors, ceilings, and rooms) is difficult. Especially in indoor scenes, walls may be partially obscured, or rooms may be connected by open doors. Misidentifying these can lead to merged rooms or missing walls. Ensuring that each property unit or room is correctly delineated is essential for 3D cadastre.

- Construction of non-flat or multi-height ceilings: Many algorithms assume flat floors and ceilings and vertical walls. Real buildings can have non-flat or multi-height ceilings, curved walls, or staircases that violate these assumptions [64].

- Recognition and modeling of openings: Doors and windows represent gaps in surfaces that must be detected and integrated into the model. An algorithm might treat an open doorway as a continuous wall, thereby sealing off spaces incorrectly [48,65,66]. Missing or false openings can greatly affect the usability of the final model.

- Robust volume generation: Creating a watertight volume (solid model) from point data. Point clouds often have holes (e.g., behind furniture or in ceiling corners out of scanner view). Methods that generate volumes must plausibly fill these gaps.

- Automation with least manual processing: Maximizing automation while maintaining model accuracy is an overarching challenge. A key difficulty is making the process adaptive to different input conditions: varying scan densities, noise levels, and building styles.

These limitations emphasize that, despite notable advances, existing methods are still constrained by simplifying assumptions or by surface-only models. This highlights the need for a workflow capable of producing enclosed volumetric solids with the precision and automation required for 3D cadastral applications. In the context of 3D cadastre, the requirement for volumetric solids extends beyond geometric precision. It underpins the legal and semantic definition of property space. Surface or mesh models, although useful for visualization, cannot explicitly define the bounded volume associated with ownership, use rights, or restrictions. In contrast, volumetric (solid) models provide closed and topologically consistent geometries that enable precise computation of intersection, adjacency, and overlap between legal entities [3,67,68,69,70,71,72,73]. This conceptual distinction establishes volumetric solids as an essential prerequisite for the reliable implementation of 3D cadastre.

2.3. Technological Solutions: Software and Tools

While theoretical methods for 3D modeling from point clouds continue to advance, their practical implementation depends on the availability and capabilities of software platforms that can handle real-world data, integrate with workflows, and produce usable geometric models. This section introduces current technological solutions used to support various stages of point cloud-based modeling, focusing on tools that facilitate automation, generate structured 3D geometries, and offer output formats suitable for 3D cadastre and BIM.

For point cloud processing and surface extraction tools: CloudCompare is a widely used open-source tool for point cloud visualization, noise filtering, segmentation, and normal vector estimation. Though it does not generate 3D volumetric models, it is a vital preprocessing step, especially for normal-based segmentation or surface fitting. It supports RANSAC-based primitive detection and region growing, often forming the basis for higher-level modeling in other software. Trimble Business Center (TBC) and BricsCAD also provide capabilities for point cloud classification and preprocessing. The Point Cloud Library (PCL) offers an extensive set of algorithms for filtering, feature extraction, segmentation, and surface reconstruction, serving as a flexible foundation for custom processing workflows.

As for platforms for automated or semi-automated 3D modeling:

- BricsCAD is a commercial CAD platform that incorporates point cloud functionality, BIM modules, and a “Scan to BIM” workflow [74]. The BricsCAD procedure directly builds 3D solids. This workflow leverages tools for segmentation, feature extraction, and solid modeling, ultimately producing BIM-ready geometries. BricsCAD can read the mesh file (.obj), making the solidification step possible. However, as observed in our tests, the BricsCAD’s “FitRoom” function has strengths for orthogonal rooms and has limitations for non-orthogonal/stepped geometries.

- Autodesk Revit with Dynamo offers a flexible and programmable environment for automated modeling [75]. While Revit supports BIM modeling with high fidelity, Dynamo, its visual scripting extension, enables users to create custom node-based workflows. Dynamo can be used to automate wall extraction, surface fitting, or parameterized model generation from point cloud inputs. Its extensibility via Python scripting makes it a robust option for research and prototyping tasks related to indoor modeling.

- FreeCAD is an open-source CAD tool with parametric modeling capabilities [76]. It supports a variety of formats and can be customized for point cloud-based 3D modeling, making it suitable for prototyping and preliminary design phases of model generation.

In most scenarios, no single tool can complete the entire modeling pipeline from raw point clouds to semantically rich solids, especially considering the geometric accuracy of 3D models. The choice of tools should be guided by the modeling objective, desired output (IFC, obj, CityGML), and practical constraints such as licensing, user expertise, and dataset size.

Instead, our approach is to combine methods and algorithms into cohesive workflows, which provides a solution to this challenge. Many methods for segmenting point clouds focus on identifying distinct features such as walls, floors, and ceilings. Techniques like RANSAC for plane detection and graph-based methods for preserving spatial relationships are well-documented. For feature extraction, methods often rely on geometric reasoning to detect elements like floors and walls, even in challenging conditions (e.g., slanted ceilings or irregular shapes). Existing solutions provide a solid foundation but often require adaptation to address specific challenges such as high variability in ceiling heights, irregular room shapes, or occluded features.

3. Methodology and Workflow Design

3.1. Overall Workflow Design

The reviewed literature highlights various approaches to convert raw point cloud data into structured 3D models. Each workflow typically includes stages such as data preprocessing, segmentation, feature extraction, and model generation. The workflows presented in these studies share common steps but vary in the degree of automation and the specific techniques used for feature extraction and model generation. Achieving the stringent geometric precision demanded by cadastral applications (typically sub-10 cm accuracy [77,78,79]) while maintaining high automation and scalability remains challenging.

The primary objective of this study, therefore, is to design an integrated, automated workflow specifically tailored for generating accurate volumetric (solid) models from indoor point clouds for 3D cadastre applications. To achieve this objective our methodology is guided by several key considerations, mainly derived from discussions and needs with our partner (GPLC), beyond what was presented in the literature:

- Nature of the input and output data: The workflow clearly requires defined input and output characteristics. For input data, we only consider indoor LiDAR point clouds, ideally preprocessed to be cleaned, noise-free, and classified. Although raw data may initially be collected, the designed procedure explicitly expects cleaned data for subsequent steps. The expected output data are solid 3D models that accurately represent the geometry of vertical cadastral lots. Crucially, the models must be compatible with common CAD tools. Additionally, the workflow strictly relies on the geometric information available within the point cloud itself, explicitly excluding reliance on external semantic data, to ensure universal applicability and robustness.

- Geometric Precision: Ensuring compliance with cadastral precision standards by explicitly integrating methods that aim for sub-10 cm level accuracy, a target based on the guidelines of cadastral surveying. This accuracy is critical for correctly capturing detailed architectural elements, irregular geometric features (such as sloped roofs or non-horizontal ceilings), and property boundaries relevant for cadastral documentation and management. When interviewing GPLC, 2 cm is a targeted accuracy for many of their cadastral projects.

- Interoperability and Simplicity: The design emphasizes ease of integration. By minimizing the complexity and number of software tools used, the workflow enhances interoperability and reduces barriers to adoption by practitioners.

- Automation: A key design priority is maximizing workflow automation. In this case, simple manual operations are involved in the steps of point cloud preprocessing and solidification, without the need for subjective selection, inspection, or expert knowledge. Minimizing human intervention through scripting and workflow integration to enhance reproducibility and efficiency. The core steps of the workflow that generate mesh and mesh optimization should run automatically once parameters are set, including batch execution.

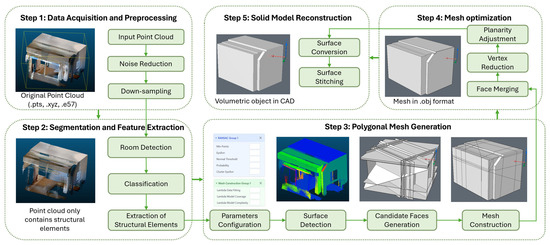

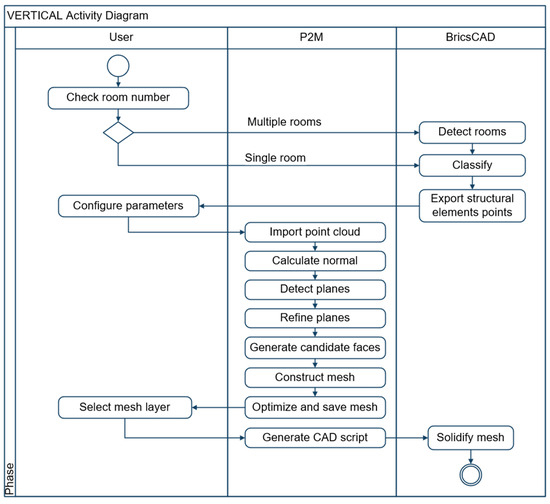

Building upon these design considerations, the proposed workflow is structured as a sequence of five interconnected stages (illustrated in Figure 1). This provides a modular and automatable sequence of operations that transforms indoor LiDAR point clouds into structured 3D solids. The following sections detail each step of our workflow, including the specific tools and algorithms used for operationalization.

Figure 1.

Integrated pipeline from point cloud to 3D solids. A generalized workflow illustrating the sequential stages of volumetric modeling from indoor LiDAR point clouds. The arrows indicate the processing sequence between stages.

3.2. Step 1—Data Acquisition and Preprocessing

Our general workflow begins with the collection of indoor LiDAR scans, typically acquired using static terrestrial laser scanners or mobile mapping systems. Our partner (GPLC) provides their self-acquired indoor LiDAR datasets.

Before applying the modeling process to improve efficiency, the preprocessing of the point cloud is essential. The existence of noise, scanning errors, and inconsistent densities will increase the computational burden of later steps. Therefore, an initial preprocessing stage is required to remove irrelevant data. This stage ensures that the input data are clean, manageable, and focused on relevant architectural content. The following sub-steps are applied:

(1) Manual or rule-based cropping: Usually, when scanning is performed, some points need to be excluded before application, such as the stairwells or corridors outside the property. Depending on the dataset, cropping can be manually defined or performed using bounding box filters, slicing tools, or elevation thresholds.

(2) Noise reduction is commonly performed using Statistical Outlier Removal (SOR) [80,81]. In SOR, each point is evaluated based on the average distance to its k nearest neighbors; outliers are removed based on deviation thresholds.

(3) Down-sampling: When dealing with a point cloud with higher density, the down-sampling step is required to retain overall geometry while significantly lowering the point count. This potential step is to reduce the computational load but also to mitigate the redundancy and noise often present at very fine resolutions. A voxel-based spatial sub-sampling [82] can be applied.

3.3. Step 2—Segmentation and Feature Extraction

Given the situation of cadastre applications and survey strategies, dividing the indoor point cloud into individual room-level units can simplify the mesh generation and solidification process and aligns with the legal and functional representation of cadastral lots. In the literature, there are several general approaches, such as geometric clustering [12,83,84], multi-label energy minimization formulation [64], voxel-based space partitioning [33], and graph-based reasoning [60,85].

After separating and detecting rooms, classification is carried out, aiming at only retaining the point cloud useful for modeling, removing clutter (furniture, pipes, etc.). In the literature, classification of architectural components from indoor point clouds is often addressed using one or more of the following strategies: rule-based classification [49], machine learning approaches [65], and deep learning methods [86,87]. Our goal is to obtain a point classification adapted to the cadastral context. Points can be labeled as walls, ceiling, floor, windows, doors, clutter, etc. Classified results are stored as points. In our workflow, door and window openings are explicitly preserved rather than filled during preprocessing. During mesh generation, these voids remain as boundary gaps on wall surfaces and are later preserved through the mesh-to-solid conversion process.

3.4. Step 3—Polygonal Mesh Generation

After obtaining the classified point cloud of building structural elements, the next task is to reconstruct a watertight polygonal mesh that faithfully represents the building’s structural surfaces. This mesh serves as the geometric foundation for subsequent solid modeling, meaning that its topological correctness, completeness, and geometric accuracy are directly tied to the success of the 3D cadastre application. Cadastral applications impose strict demands: the mesh must be manifold (no topological defects), watertight (no gaps or open edges), and geometrically consistent to within sub-10 cm accuracy.

Polygonal mesh generation from indoor point clouds is challenging due to several factors: incomplete data (occlusions or missing parts), measurement noise, and the complexity of man-made structures (multiple height levels, sloped ceilings, non-orthogonal walls). Several well-established reconstruction methods exist, but they present important trade-offs. For polygonal surface generation, 2.5D Dual Contouring [29] is effective for aerial or terrain datasets where surfaces can be represented as height fields, but it fails in indoor scenarios with vertical or overhanging structures. The voxel-based method can fill gaps, but its planar accuracy is limited by voxel size [52] and kinetic shape [88]. In contrast, the PolyFit approach [63] (see Section 2.2) formulates reconstruction as a global optimization problem that simultaneously minimizes data-fitting errors while penalizing excessive model complexity and poor surface coverage. This multi-objective formulation allows PolyFit to preserve sharp planar features and recover missing regions by exploiting geometric regularities among detected primitives. Unlike the voxel-based or 2.5D methods, it is not constrained to a fixed spatial grid or height-field representation, making it suitable for rooms with sloped or non-orthogonal walls and varying ceiling heights. Therefore, in this study, we adopt the PolyFit approach. This approach is robust for indoor environments because of its balance of geometric precision, model complexity, and completeness.

In our designed workflow, the pipeline of PolyFit is applied in two stages: (1) Detection and refinement of geometric primitives, and (2) PolyFit-based candidate face generation and mesh construction.

In the first stage, we first detect planar supports representing walls, floors, and ceilings. This can be achieved via RANSAC algorithm [89,90] or region growing method [91]. It is used to detect the primitive shapes of planes. The RANSAC parameter definitions and detailed impact can be found in Table 1. These are carefully tuned and tested to balance sensitivity and robustness in the implementation steps.

Table 1.

RANSAC parameters and definitions.

Since the detected segments may contain undesired elements due to noise, outliers, and missing data, they are refined through an iterative plane merging and re-fitting process. Each plane is re-estimating the number of points lying on the supporting planes, and similar planes are merged. Merging is performed when two planes satisfy both an angular threshold and a point-to-plane distance threshold. This reduces redundancy, eliminates near-duplicate planes, and improves the stability of subsequent optimization. The output is points with plane IDs.

In the second stage, starting from the set of supporting planes, each refined plane is mathematically extended to form an infinite supporting plane, retaining its normal vector and positional parameters. Pairwise intersections between supporting planes are computed to obtain intersection lines. Each plane is then clipped by the intersecting planes and the object’s bounding box, while preserving the incidence relationships between faces and edges. The resulting polygons constitute the pool of candidate faces. From these candidate faces, a mixed-integer programming (MIP) solver addresses a constrained combinatorial optimization problem to select the final faces. The solver minimizes a weighted sum of energy terms: data-fitting (fitting quality of the faces), model complexity (determining simpler structures), and point coverage (ratio of the uncovered regions in the model). The hard constraints consider that each edge must be incident to exactly two faces in a closed model, or to a single face if it is a boundary edge. The optimization yields the optimal subset of faces forming a watertight, manifold polygonal surface. The outcome of this stage is a mesh file containing coordinates of each vertex, and the vertex serial consists of each face. The PolyFit parameters and corresponding definitions can be found in Table 2. In particular, the three parameters are weight normalized in [0, 1].

Table 2.

PolyFit parameters and definitions.

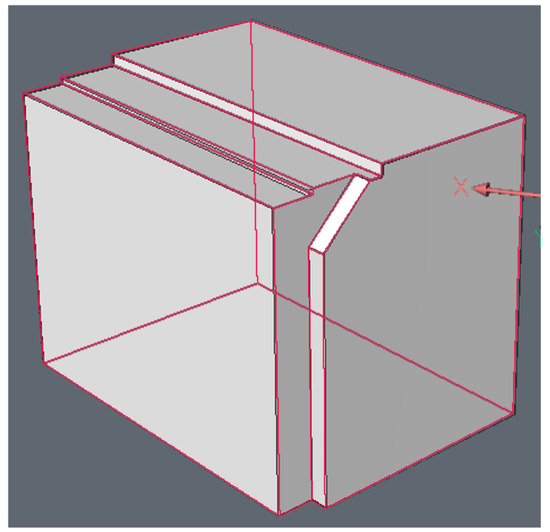

3.5. Step 4—Mesh Optimization

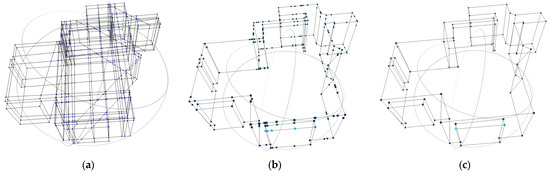

Following polygonal surface reconstruction, the raw mesh often contains redundant vertices, clipped small faces, and sometimes topological inconsistencies. Left untreated, these situations can impair both mesh visual clarity and the solidification step. In this integrated workflow design, we propose a mesh optimization process to make the generated mesh cleaner, more regular, and structurally coherent, according to our cadastral context. To optimize the produced meshes, we defined and applied the following steps and operations. Some examples of optimization operations are illustrated in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Example of mesh optimization: (a) Original mesh, (b) coplanar face merging, and (c) removal of isolated and intermediate vertices. The dots indicate the mesh vertices at each optimization stage.

- Merging coplanar faces: This operation detects and merges adjacent planar faces that are geometrically aligned (see Figure 2b). We compute the normal vector for each face via the cross product of two non-collinear edges. We group faces whose normals differ by less than a small angular threshold and share at least one common edge. For each group, we reconstruct the outer boundary loop by traversing the face adjacency graph and generate a single polygonal face that replaces the group.

- Check non-manifold edges and vertices: This step identifies and corrects non-manifold conditions: that each edge is shared by at most two faces, and each vertex belongs to a single connected surface component.

- Remove unnecessary vertices and edges: This operation identifies vertices not referenced by any faces, removes them, and remaps face indices accordingly (see Figure 2c). This detects vertices lying on a straight segment between two neighbors within a distance threshold and position epsilon. It removes them and reconnects edges to preserve polygon shape.

- Planarity adjustment: This step adjusts nearly horizontal and nearly vertical surfaces to be exactly aligned with principal axes. We apply DBSCAN clustering [92] for unifying all Z-coordinates in each connected component. We detect faces whose normals deviate from vertical by less than a certain threshold, using Singular Value Decomposition (SVD) in Eigen [93] to calculate and adjust original X and Y coordinates.

Thresholds were tuned according to point cloud resolution; the following Table 3 summarizes the key parameters for each mesh optimization operation.

Table 3.

Key parameters for mesh optimization.

For the vertical-alignment threshold, practical explanation is as follows: 0.01 rad (≈89.4°) refers to a very strict, suitable for clean data with high precision requirements; 0.05 rad (≈87.1°) refers to moderately strict, recommended default for typical indoor scans; and 0.1 rad (≈84.3°) refers to tolerant for slightly noisy data but may misclassify tilted walls. Values above 0.15 rad are not recommended due to excessive looseness.

This mesh optimization stage refines the initial reconstruction to remove geometric redundancies, correct topological defects, and enforce structural regularity. These integrated operations, ranging from coplanar face merging to vertical or horizontal alignment, produce a cleaner mesh that considers both the geometric precision and possible subsequent solid modeling.

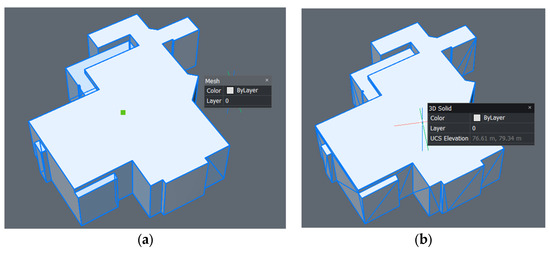

3.6. Step 5—Solid Model Reconstruction

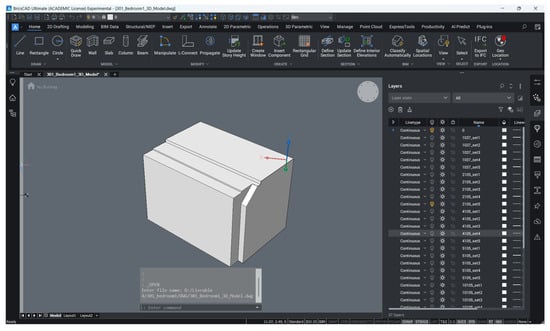

The final stage in the volumetric modeling workflow is the conversion of the optimized polygonal mesh into a solid model. Solid models are critical for 3D cadastral modeling in CAD environments for further editing, visualization, or integration into cadastral databases. Figure 3 shows an example of an imported mesh and a constructed solid.

Figure 3.

Example of imported mesh and constructed solid: (a) Original mesh, (b) solid model. By checking the property, we can see the entity is a 3D solid, and elevation, surface areas, and volume can be directly calculated.

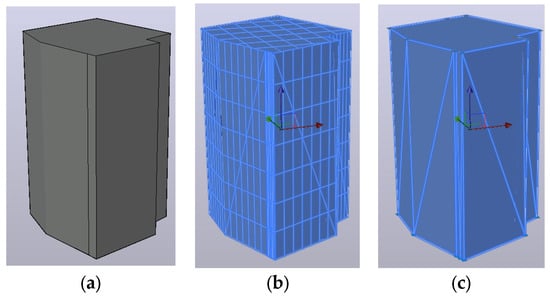

The general CAD approach always involves a multi-step conversion. Starting from mesh-to-surface, each mesh face is converted to a planar surface entity. Then, surface stitching is applied to join adjacent surfaces and create a closed shell of stitched surfaces. In this way, a solid entity is formed, whose surface area and volume can be automatically measured. For example, AutoCAD provides the SURFSCULPT command, which trims and combines a set of surfaces or meshes that completely enclose volume to create a 3D solid (Figure 4, tested in AutoCAD version 2024). In cases with small gaps or inconsistencies, additional preprocessing steps, such as surface explosion, faces flattening, or merge optimization—may be required to achieve closure.

Figure 4.

Example of converting mesh to solid in AutoCAD: (a) Original mesh, (b) converted surface, (c) exploded regions and generated 3D solid.

In this designed workflow, the BricsCAD software is adopted for mesh-to-solid conversion through its SOLIDIFY command, which follows the same general CAD logic. The command automatically converts region or mesh groups into surfaces, stitches the surfaces where possible, and finally converts the stitched surfaces into solid bodies. This choice is motivated by three reasons: (1) SOLIDIFY can be fully automated through command scripts, facilitating batch processing; (2) it aligns well with the preceding mesh optimization stage, which produces coplanar, watertight surfaces that satisfy the stitching tolerance required for successful solid creation; and (3) BricsCAD supports the direct reading and writing of the obj file.

4. Implementation

Building upon the methodology described in Section 3, hereafter referred to as the VERTICAL workflow, this section presents the implementation solution: a web-based application (named P2M) for automated volumetric modeling from indoor point clouds (P) to (2) a solid model (M), integrating a browser-based graphical interface with C++ core tools. This solution maps each step of the designed VERTICAL workflow to specific software components, programming languages, and custom-developed modules.

The prototype operationalizes the workflow described in Section 3 into a practical, integrated software solution. It adopts a modular architecture that links preprocessing, segmentation, mesh reconstruction, optimization, and solid model generation into a single pipeline. Different workflow stages are assigned to specific modules, enabling targeted optimization while ensuring smooth data transfer between tools. The integration automates data transfer, parameter configuration, external software invocation, and results handling, thereby enhancing efficiency and reproducibility across large datasets.

An imposed key element is to integrate a particular CAD software into our workflow implementation. The CAD software should provide functions such as point cloud processing and visualizing functions, the ability to convert surface elements into 3D solids, and the interoperability of existing 2D/3D drafting. After reviewing existing platforms, performing tests, and discussing with our surveyor working partner, BricsCAD was selected.

To formalize this prototype solution, the procedure is modeled as a UML activity diagram (see Figure 5). Three actors (user, P2M procedure, and BricsCAD) are represented by distinct swim lanes. The processes of segmentation and feature extraction and solid model reconstruction (steps 2 and 5 in Section 3) are carried out with BricsCAD. The specific version applied is BricsCAD V25 (x64). While data input, parameter configuration, polygonal mesh generation, mesh optimization, result visualization, and CAD automated script generation are performed in P2M. The result is a structured multi-stage approach for transforming indoor LiDAR point clouds into accurate 3D volumetric models.

Figure 5.

UML activity diagram illustrating the theoretical execution sequence of the prototype. The diagram distinguishes the responsibilities of the three primary actors: User, P2M procedure, and BricsCAD, using separate swim lanes and identifies decision points and process flow for data preparation, mesh generation, and solid model reconstruction.

BricsCAD makes it easier to perform activities (cf. in the right column of Figure 5) such as:

- -

- Detect rooms: We employed the “RoomDetect” function integrated within BricsCAD, which automatically detects enclosed rooms. The advantage of this approach is that it minimizes user intervention and the method works reliably.

- -

- Classify: We used the “POINTCLOUDCLASSIFY” function available in BricsCAD, which employs GPU acceleration (CUDA) to perform semantic classification on large point clouds.

- -

- Solidify mesh: We applied the Solidify tool that converts meshes to surfaces, then to stitch surfaces where possible, and finally to convert the stitched surfaces to solids [94]. This tool is particularly effective in this workflow because the preceding mesh optimization stage ensures that surfaces are clean, coplanar where expected, and meet stitching tolerance requirements, thereby increasing the solidification success rate.

The core prototype (P2M) follows a modular architecture, composed of three main components:

(1) Web-based User Interface: An interactive Three.js-based interface for data input, parameter setting, visualization, and CAD script generation.

It provides an interactive platform to input single or multiple point clouds (.pts, .xyz), configure parameters for RANSAC and PolyFit, preview intermediate and final meshes, and selectively prepare results for solidification. Unlike conventional manual workflows, P2M supports automated batch processing of multiple parameter sets, significantly reducing processing time for large datasets. For the results of each input file and parameter combination, the Web UI automatically generated .obj mesh models into the viewer as new layers, preserving grouping by room, RANSAC set, and PolyFit set. The Web UI integrates a dedicated script generator that produces “.scr” files to automate BricsCAD operations, including .obj files import, layer naming and assignment, and “SOLIDIFY” execution. The interface is implemented using HTML5, CSS, JavaScript, and Three.js. Parameter configuration is implemented as interactive forms in the Web UI, with values stored in JSON files.

(2) Flask Backend: The middleware between the Web UI and C++ core.

It is responsible for receiving frontend requests, generating configuration JSON files, launching the C++ core programs, monitoring their execution, and returning results. This module is built in Python with Flask (version 3.0.3), handling inter-process communication and file management.

(3) C++ Core Processing tools: A CGAL-based C++ application forming the computational backbone of the prototype.

This module performs point cloud processing, plane detection, mesh generation, and optimization. It is built based on CGAL 6.0.1 library where efficient RANSAC and Polygonal Surface Reconstruction (PolyFit) modules are mainly used. Mixed-integer programming solvers are Gurobi (www.gurobi.com accessed on 20 September 2025), version 12.0.0, and Solving Constraint Integer Programs (SCIP) (scipopt.org accessed on 20 September 2025), version 9.2.0.

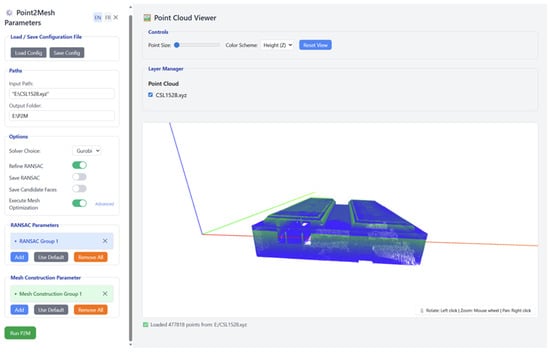

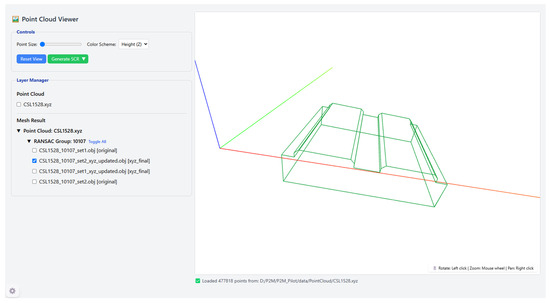

Figure 6 and Figure 7 illustrate the implemented P2M prototype, including the parameter interface, visualization view, and selection of generated meshes.

Figure 6.

Graphical user interface of the P2M Web UI showing the data upload, parameter configuration panel, and point cloud viewer sections. The interface supports single and batch processing modes, with parameter sets stored as JSON configuration files for reproducibility.

Figure 7.

Visualization module of the P2M Web UI displaying mesh reconstruction results as layer-based groups organized by room and RANSAC set. Users can preview intermediate and final meshes, select specific results for export, and generate CAD automation scripts for BricsCAD.

5. Experimentation and Results

This section describes experiments performed with the given LiDAR datasets to produce 3D models. Datasets of real-world building interiors point cloud data are introduced, including acquisition method, characteristics, and room division. The parameter combinations explored in the experiments are illustrated and categorized. Finally, the generated 3D models are summarized and presented.

5.1. Dataset Introduction

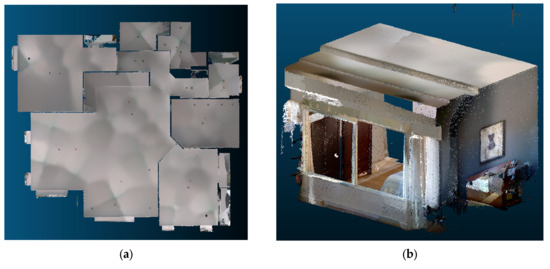

The dataset used in this study consists of a collection of interior LiDAR point cloud datasets of condominium units acquired by GPLC, using NavVis VLX2, a wearable mobile laser scanning system (example shown in Figure 8).

Figure 8.

NavVis VLX2 mobile mapping system to capture point cloud by GPLC.

The precision of the NavVis VLX2 system ranges between 6 mm and 15 mm. Performance varies depending on many real-world factors, such as the geometry of the environment being scanned. With loop closure applied for error correction, which was the case in our survey, absolute accuracy is 8 mm to within one sigma. By using checkpoint optimization, absolute accuracy can increase to 6 mm.

This system was used to capture two different residential units in separate buildings. They have varying interior geometries, including single-level rooms, multi-level ceilings, and sloped roof structures. All point clouds are stored in industry-standard formats (.e57), with coordinates in a local reference system. The raw scans were pre-cleaned and clipped prior to this study to remove outliers and non-relevant data. The spatial extent of each dataset, expressed as the dimensions of bounding box (W × D × H), along with the number of rooms and points, is summarized in Table 4. We finally chose to use one dataset of a whole condominium and a dataset of one single bedroom of another property (manually selected and cropped by GPLC) for our test (Figure 9).

Table 4.

Original point cloud datasets.

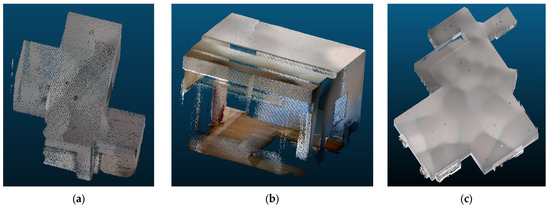

Figure 9.

(a) Original point cloud of dataset “F2C1”, (b) original point cloud of dataset “301_bedroom1”.

Given the workflow requirements, the F2C1 dataset was subdivided into room-level units to support per-room mesh reconstruction and parameter tuning. For the F2C1 dataset, room detection was performed in BricsCAD using its segmentation tools. According to the ground truth, there are 11 pieces of room (Figure 10). Due to the insufficient points of some wardrobes and doors, pieces 7, 8, 10, and 11 could not be detected and segmented in BricsCAD. Finally, seven distinct .pts files are obtained. The names of each file, point numbers, and bounding box size can be found in Table 5.

Figure 10.

Room division of dataset F2C1. Room numbers are presented in the white boxes.

Table 5.

F2C1 .pts file list for each room.

All these point clouds of rooms are classified in BricsCAD, and the exported point cloud files only contain the ceiling, floor, columns, and walls points. Points belonging to classes such as furniture, movable objects, and non-structural features are removed.

In total, the study employed two datasets, covering eight rooms. These room-level point clouds served as the input for all parameter combinations tested in Section 5.2. This room-by-room approach reduces processing time and memory usage and enables room-by-room quantitative evaluation against reference models.

5.2. Parameter Combinations

To ensure that P2M produces accurate and robust 3D models while maintaining computational efficiency, several groups of RANSAC and mesh generation (PolyFit) parameters were selected. Additionally, by configuring and testing different parameter groups, we could systematically evaluate their influence on the generated models and guide subsequent qualitative and quantitative analyses. The definition and description of these parameters can be found in Section 3 (see Table 1 and Table 2). Based on ranges commonly reported in the literature and refined through preliminary experiments on a small subset of rooms, 35 groups of parameters in total were created: 7 groups of RANSAC parameters (see Table 6) × 5 groups of PolyFit parameters (see Table 7). For naming the groups, a systematic approach was used based on key parameters. The naming convention (Group Name in the following tables) follows the format: min_point/100, epsilon × 1000, normal_threshold × 10. This method ensures clarity and consistency when referencing different groups.

Table 6.

RANSAC parameter groups.

Table 7.

PolyFit parameter groups.

For RANSAC parameters, the ranges were determined according to the spatial resolution and noise characteristics of the point cloud datasets, combined with guidelines from previous geometric primitive extraction studies [56,95]. The parameter min_points (200–1000) ensures statistical robustness while preserving smaller architectural elements. The parameter epsilon (0.003–0.02 m) defines the maximum distance from a point to a plane and is set according to the sensor noise. The parameter normal_threshold (0.5–0.7 radians) limits the angular deviation between point normal and the plane normal, balancing strict planarity and tolerance to irregularities. These settings align with the centimeter-level precision targeted for indoor cadastral applications. For all configurations, the RANSAC cluster epsilon was fixed to 0.02 m and probability to 0.8.

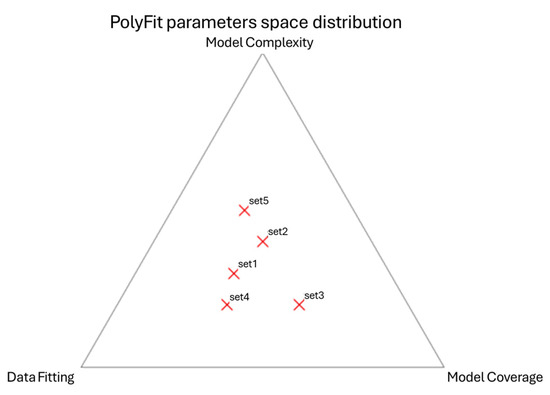

For PolyFit parameter groups, they were selected firstly based on the recommendations provided in the original PolyFit study by Nan and Wonka [63], and secondly to reflect different balances among the three weights. The balances among the three parameters govern the trade-off between geometric precision, surface completeness, and model simplicity. Each PolyFit parameter group was designed so that one λ-term dominates while the others remain moderate, allowing possible evaluation of how each weight affects the final model, as shown in Figure 11. The chosen ranges (typically 0.2–0.5), therefore, reflect both the literature’s guidance and our intent to explore how different regularization weights influence the resulting mesh quality and solid generation.

Figure 11.

PolyFit parameters space distribution. Each set is presented with a red x mark.

Based on the definition and some pre-tests the impact of the parameters on models is presented in Table 8.

Table 8.

Parameter impact on models.

For mesh optimization parameters, the parameters applied are shown in Table 9.

Table 9.

Mesh optimization parameters.

Unlike conventional single-run workflows, P2M implements automated batch execution for all parameter combinations. The Web UI queues all selected parameter sets, serializes them into JSON, and sends them to the Flask backend. The backend launches the C++ core processing for each (room, RANSAC set, PolyFit set) combination. This design enables repeatable large-scale experiments and comparative analysis without manual intervention, substantially reducing human error and processing time. The multi-parameter outputs produced in this stage feed directly into the quantitative and qualitative evaluation procedures described in Section 6. The optimal parameter configuration can be determined based on accuracy metrics, and the comparison across rooms provides insight into the generalizability of the workflow.

5.3. Generated Model Results

The proposed P2M prototype was executed on the prepared dataset (Section 5.1) using multiple RANSAC–PolyFit parameter combinations (Section 5.2). All programs were performed with an Intel Core i7-10750H CPU (2.60 GHz) and 16 GB of RAM. The chosen MIP solver was SCIP (version 9.2.0): an open-source optimization software framework for solving integer programming and constraint programming problems. Based on previous parameter combinations, 3D models were generated in obj format following a systematic naming convention. Each obj file name encodes the dataset ID, room number, RANSAC group, and PolyFit group. For instance, “F2C1_R1_4105_set1.obj”. The final model numbers have been documented for thorough record-keeping and easy reference. In total, 280 models (245 for F2C1, 35 for 301_bedroom1) for seven rooms were generated. The maximum, minimum, and average time used for each room was calculated and reported in Table 10. It is worth mentioning that we also applied Gurobi with an academic license as an MIP solver. The performance was more efficient, especially with rooms with more points.

Table 10.

Computation time used for model generation of each room. All experiments were conducted on Windows 11 (x64) with an Intel Core i7-10750H CPU (2.60 GHz) and 16 GB RAM, using CGAL 6.0.1 and the SCIP 9.2.0 solver (with default parameters and a 600 s time limit).

Given the large number of tested configurations (35 unique parameter combinations across all rooms, and some models might have no significant differences), only a curated subset of results is shown here.

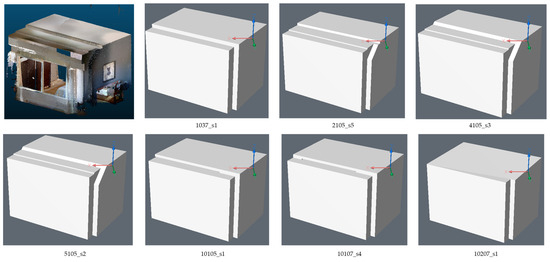

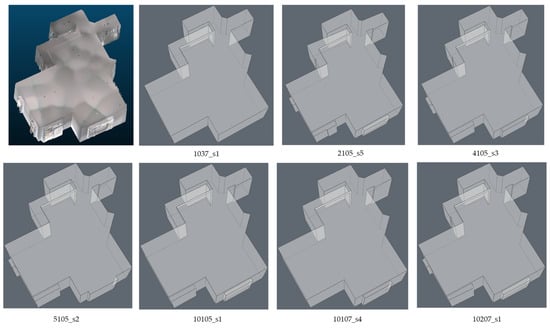

To display the impact of parameter variation on model geometry, two representative rooms with complex geometry were selected to show the differences in Figure 12 and Figure 13.

Figure 12.

Comparison of reconstruction results for 301_bedroom1.

Figure 13.

Comparison of reconstruction results for F2C1_R1.

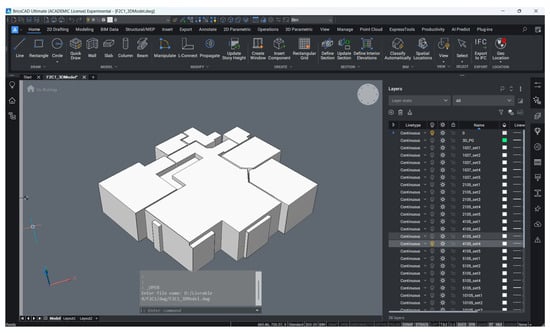

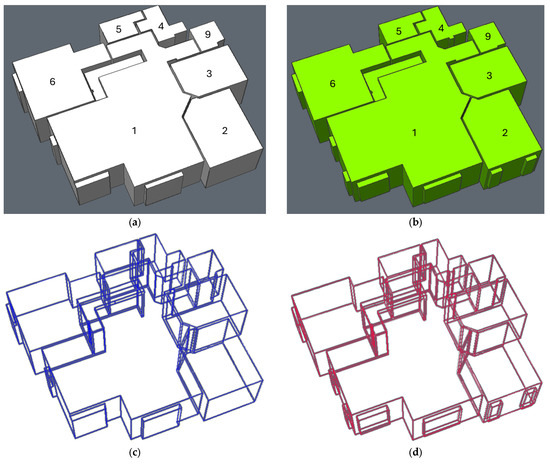

To facilitate visualization and solidification, all meshes were automatically imported into dwg files with dedicated layers, each corresponding to a specific parameter combination across all rooms. This layered structure enables clear inspection of the results. The “SOLIDIFY” command is automatically triggered to generate 3D solids for all rooms, and the entire process is executed simply by running the SCR file generated by P2M. Figure 14 and Figure 15 illustrate the resulting dwg files opened in BricsCAD for the two datasets.

Figure 14.

Content of dwg file with meshes in different layers in BricsCAD (Dataset: F2C1).

Figure 15.

Content of dwg file with meshes in different layers in BricsCAD (Dataset: 301_bedroom1).

In summary, the implementation of the prototype and modeling results demonstrate how the methodological workflow outlined in Section 3 can be translated into a fully operational application. Through a modular architecture integrating Web UI, Flask backend, and CGAL-based C++ core processing, the prototype enables automated, repeatable processing of indoor point clouds: from point cloud data to a watertight solid model. The dataset, comprising scans of multiple and single rooms, was processed using 35 parameter combinations, with results filtered to highlight representative configurations. The generated outputs confirmed that this prototype can produce manifold CAD-ready solids with minimal manual intervention, supporting large-scale and parameter-sensitive experimentation. This prototype supports the automated batch processing of multiple parameter sets, reducing processing time for large datasets while preserving model accuracy. The production of manually drafted models, in contrast, typically requires several hours for complex scenes. For example, the case of a single room (301_bedroom1) took about 15 min for a skilled expert, while the entire condominium (F2C1) would require at least half a day to complete. With the VERTICAL workflow and P2M prototype, by comparison, the same process for dataset F2C1, including preprocessing and classification, could be completed in roughly 10 min. This comparison illustrates the substantial effort demanded by traditional workflows and highlights how the proposed automated core procedure effectively reduces manual labor while improving overall efficiency, thereby establishing a robust foundation for subsequent model evaluation.

6. Validation: Qualitative Evaluation and Quantitative Assessment

The primary objective of this section is to validate the feasibility of the proposed P2M workflow in producing geometrically accurate and topologically correct 3D volumetric models from indoor point clouds. Evaluating geometric precision in automated 3D modeling workflows is essential to ensure the accuracy and reliability of generated models, particularly for applications in cadastral and BIM contexts. Despite the critical nature of geometric precision, the existing literature exhibits considerable variation in how precision is defined, measured, and validated.

Some studies adapt quantitative metrics. Peters et al. [28] and Jung et al. [47] explicitly measure geometric precision using RMSE (Root Mean Square Error), EADE (Expected Absolute Distance Error), or related metrics, ensuring reliable comparisons with ground truth. Other studies focus on practical thresholds for merging planes and handling deviations, ensuring geometric fidelity in reconstruction [12,20]. Nevertheless, many studies do not incorporate ground truth comparisons and instead rely on visual validation. Often, reconstructed models are assessed through subjective inspection or through comparisons with the original point cloud without quantitative metrics. In several cases, authors focus more on automation, semantic labeling, or modeling efficiency than on the formal validation of geometry.

In this study, we decide to proceed with the validation of the generated 3D models by following a two-step strategy: (1) a qualitative evaluation based on visual inspection; and (2) a quantitative assessment based on nine complementary metrics or indicators. In each validation, as comparison models, we exploit 3D models manually produced by professional land surveyors from our partner surveyor firm.

6.1. Qualitative Evaluation

Automated construction of 3D room models from point clouds or segmented data often produces incomplete or inconsistent geometry due to noise, occlusion, or algorithmic limitations. Before undertaking quantitative assessments, it is essential to ensure that the model captures critical structural and architectural elements well. Numerical indicators alone may fail to reveal subtle omissions or misrepresentations in roof geometry, wall boundaries, or internal partitions. In contrast, a rapid visual inspection will be able to reveal whether the model succeeds in representing the intended spaces and features. This qualitative evaluation is based on the identification of room features as specific evaluation criteria.

6.1.1. Room Features as Evaluation Criteria

This section describes a method for qualitatively evaluating generated 3D models of indoor point clouds. It is designed to compare a generated 3D model with observed physical room structure or an existing ground truth model (e.g., 3D models produced by professional land surveyor from inspecting the original point cloud). It focuses on geometry, structural correctness, and model completeness, allowing comparison across models of varying complexity without predefined room categories.

Drawing from observations of current datasets and interviews with surveyors of GPLC, we defined a list of typical features that may be found in a room and are relevant for model evaluation (see Table 11). These observations include point density, geometric complexity (spanning simple rectangular rooms to multifaceted or L-shaped layouts), feature variety (such as the presence or absence of obstacles like columns or inner walls), and shape diversity (e.g., flat ceilings, stepped ceilings, or slanted walls), highlighting the characteristics of the tested dataset. Based on these considerations, for the models of each room, the top-performing parameter combination was selected for further quantitative analysis.

Table 11.

Room features considered for qualitative evaluation.

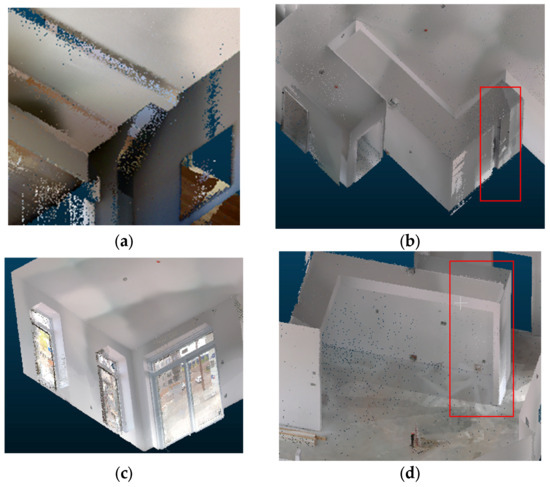

Here are some examples of these room features: F2C1_R4 has the simplest geometric shape and no complex structure, 301_bedroom1 is a relatively small space with complex ceilings, and F2C1_R1 is a large room with complex ceilings, containing windows and interior structure (Figure 16). Detailed specific room features are illustrated in Figure 17.

Figure 16.

Examples of different room geometric shapes: (a) F2C1_R4: regular boundary shape and flat roof; (b) 301_bedroom1: small space with complex ceilings; (c) F2C1_R1: large space with complex ceilings, windows, and interior structure.

Figure 17.

Specific room features: (a) multi-layer and sloped ceiling; (b) column (in the red rectangle); (c) windows; (d) interior walls (in the red rectangle).

Given the room features of interest, the evaluation criteria for 3D models can be established. These criteria are classified into four groups: mandatory constraint, core structure, roof, and detail features (see Table 12). All criteria are examined by visual inspection except for the water-tightness criteria.

Table 12.

Three-Dimensional model evaluation features, description, and weight.

To obtain a score for each generated 3D model, we first rated each criterion with a value of 0 (poor), 1 (acceptable), or 2 (good), depending on the model’s ability to reconstruct the expected structural features. Secondly, we associated weight at each criterion with the help of land surveyors. The weight distribution (see Table 9) is designed to balance: basic geometric structure (walls, corners, footprint); architectural features (roof, windows, columns, internal walls); and surface-level quality (cleanliness, regularity). Finally, each 3D model obtained a score between 0 and 100, based on a final score calculation formula:

For each enabled criterion i:

- = score for criterion : [0–2]

- = global weight of criterion

- Normalized weights over enabled criteria

Not all criteria apply to every room. A criterion was only evaluated if the corresponding feature was present in the room’s ground truth. The actual weight used in a specific room was normalized over the enabled criteria only. When a modeling error could affect multiple criteria, the issue should be assigned to the most representative criterion. Normally, models manually constructed by experts are used as the reference baseline, and they are assumed to correspond to 100. To interpret the score, we converted it into a qualitative rating (good: 90 < score ≤ 100; acceptable: 80 < score ≤ 90; moderate: 70 ≤ score ≤ 80; poor: 0 < score < 70; and invalid: 0).

6.1.2. Evaluation Result

For 301_bedroom1, among the 35 generated models, 13 models have a rating higher than “Acceptable” (Good: 1, Acceptable: 12, Moderate: 2, Poor: 20). Parameters group 2105_s5 has a better visual result (e.g., score = 100) (Figure 18); other sets of 4105 and 5105 have acceptable visual results (e.g., score = 88.2). The room footprint is correct, and the boundary is clear. The roof height levels are correctly modeled; the sloped ceiling is represented.

Figure 18.

301_bedroom1 model 2105_s5. The red wireframe is the cadastre model that serves as ground truth.

For the F2C1 dataset, among 245 models, 230 models have a rating higher than “Acceptable” (Good: 215, Acceptable: 20, Moderate: 5, Poor: 5). Rooms with relatively simple geometries, such as R2, R3, R4, and R5, were successfully reconstructed with visually satisfactory quality under most parameter combinations, demonstrating the robustness of the workflow. The only exception was group 1037 in R4 (e.g., score = 50). In F2C1_R1, the presence of a complex ceiling, multiple windows, a column, and other interior structures posed greater challenges. Several parameter groups produced clear and consistent representations, among which group 4105 contains more details. For F2C1_R6, where limited point density and door-induced occlusions could have hindered modeling, results remained visually coherent, with 4105 showing representative better quality. For F2C1_R9, though all models preserve the correct shape, boundary regularity, and corner accuracy, the parameter group 2105_s4 could capture finer details like window geometry.

These examples illustrate that across a range of room shapes and complexities, multiple parameter settings can deliver visually reliable results, supporting the feasibility and adaptability of the proposed workflow. A representative subset of models, selected for diversity rather than “best” performance, is shown in Figure 19: group 4105_s1 for R1, R2, R3, R4, R5, R6, and 2105_s4 for R9. These models will be used in the following section for quantitative assessment. Considering both datasets, the overall success rate is 86.8%.

Figure 19.

F2C1 model results compared with manually constructed model as ground truth: (a) generated model; (b) ground truth; (c) wireframe of generated model; (d) wireframe of ground truth. The room numbers are presented on the model in (a,b).

6.2. Quantitative Assessment

While the qualitative evaluation ensures that the reconstructed models are visually consistent with their real-world counterparts, the quantitative assessment provides objective measures of geometric fidelity against ground-truth reference data. This step focuses on verifying how accurately the models reproduce the surveyed geometry in terms of size, shape, and structural details.

To ensure meaningful, reliable metrics, the quantitative analysis is applied only to the representative subset of models selected in the previous section. This restriction ensures that the reported statistics are meaningful, as they are computed on geometrically valid and topologically sound reconstructions.

6.2.1. Indicators

Nine complementary indicators are used, covering global scale, vertical alignment, planimetric completeness, and boundary complexity. Key purposes of each indicator are also discussed in Table 13. Together, these indicators provide a comprehensive measure of reconstruction accuracy, addressing both absolute dimensions and finer structural details.

Table 13.

Indicators for model quantitative assessment and their key purposes.

6.2.2. Assessment Result

Table 14 presents the results of the quantitative assessment for each room, with the selection of the qualitative analysis. In addition to relative accuracy percentages, the RMSE of each indicator is calculated to provide an absolute measure of deviation from the reference ground truth. The relative accuracy percentages are defined as one minus the relative error between the generated and reference models. The RMSE is computed as the square root of the average squared differences, providing an absolute measure of error across all rooms.

Table 14.

Model accuracy and RMSE of each indicator.

Across all models was achieved, with average accuracies exceeding 97% in every case and surpassing 99% in most. Vertical geometry was especially stable: ceiling level number detection reached 100% accuracy for all rooms, while maximum and minimum ceiling heights consistently exceeded 99.6%.