Abstract

This study aims to give an insight into the development trends and patterns of social organizations (SOs) in China from the perspective of network science integrating geography and public policy information embedded in the network structure. Firstly, we constructed a first-of-its-kind database which encompasses almost all social organizations established in China throughout the past decade. Secondly, we proposed four basic structures to represent the homogeneous and heterogeneous networks between social organizations and related social entities, such as government administrations and community members. Then, we pioneered the application of graph models to the field of organizations and embedded the Organizational Geosocial Network (OGN) into a low-dimensional representation of the social entities and relations while preserving their semantic meaning. Finally, we applied advanced graph deep learning methods, such as graph attention networks (GAT) and graph convolutional networks (GCN), to perform exploratory classification tasks by training models with county-level OGNs dataset and make predictions of which geographic region the county-level OGN belongs to. The experiment proves that different regions possess a variety of development patterns and economic structures where local social organizations are embedded, thus forming differential OGN structures, which can be sensed by graph machine learning algorithms and make relatively accurate predictions. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first application of graph deep learning to the construction and representation learning of geosocial network models of social organizations, which has certain reference significance for research in related fields.

1. Introduction

With economic and social development, Chinese social organizations have been developing rapidly, participating in planning and governance, providing professional services in various fields such as health care, social security, and public education [1]. Although social organizations often work with or alongside government agencies, and may even receive funding or commissions from the government, they are actually independent third parties outside of the government in most domains.

When the People’s Republic of China was founded, there were only about 100 national social organizations and 6000 local social organizations. Soon after the beginning of the Cultural Revolution in 1966 when the Ministry of the Interior, which was in charge of all Chinese social organizations, was abolished, social organizations almost vanished in mainland China. Thanks to the increasingly liberal social climate in China after the reform and opening up, the announcement of the Regulations on Registration of Social Organizations and the Fund Management Measures laid a solid legal foundation for the development of social organizations, whose number nearly doubled in the following decade.

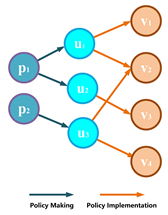

In the first decade of the 21st century, social organizations in China put on a spurt. Nowadays, however, confronted with a saturated market and continuously perfecting policies and legal systems, the growth rate has decreased (Figure 1), which indicates the shift of development philosophy in China, from the pursuit of speed to the pursuit of quality.

Figure 1.

The development trend of social organizations in China before COVID-19 pandemic.

Social organizations in China can be divided into three categories: “top-down”, “bottom-up”, and “external imported”. Government-run organizations and foundations are typical “top-down” social organizations. In contrast, the “bottom-up” social organization includes all kinds of local industry associations and private non-profit organizations. After China’s accession to the World Trade Organization(WTO), the “externally imported” ones, whose funding, project operation and governance are mainly derived from foreign social organizations, is a force to be reckoned with, bringing new ideas and innovations to fields such as environmental protection, poverty alleviation and female rights. The vast territory, the uneven distribution of natural resources, the inter-mingling of various social classes, the unbalanced development and cultural diversity in China have contributed to the great differences in social development as well as the composition of social organizations from all-around China. Generally speaking, geographic location, including local economy, culture and policies, is an important factor in the growth of social organizations, and it’s considerably crucial to explore the impact of abstract structures embedded in geographic information on the development of social organizations in China.

A social network is a structure composed of various social entities; the most familiar one to us is no doubt the Internet-based social network (e.g., Facebook, LinkedIn, or WeChat). However, except from individuals online, social organizations can also be an important composition of a social network [2]. This perspective provides a set of methods and theories for analyzing the structure of social entities as a whole, as well as explaining the patterns observed in these structures [3]. The social networks analysis(SNA) has recently become increasingly popular due to rising technology of graph machine leaning [4,5]. From the mathematical concept of graphs, the simple and straightforward function of graphs enables us to obtain a clearer picture of community structure and their interactions. However, previous literature paid little attention to the quantitative and structural exploration of organizational networks. In this paper, we accomplished the construction and exploratory analysis of specific machine learning algorithms and graph models by synthesizing political and economic information embedded in organizational social network (OGN) based on real-world data.

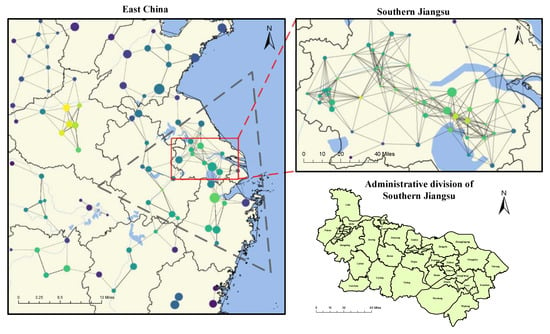

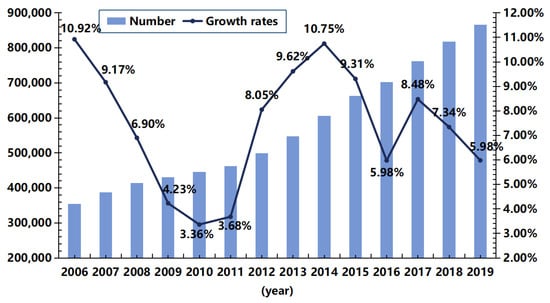

Figure 2 illustrates the distribution of social organizations in China using the database constructed in this paper, revealing a nationwide organizational social network (OGN), where the dots represent social organizations of each administrative unit and the brightness of each dot represents its degree centrality. The concentration of social organizations is consistent with the distribution of prominent economic zones, such as the Yangtze River Delta and the Pearl River Delta. There is an imaginary diagonal line across China, called the Hu Line. The Hu Line has vast demographic significance and can also represent the distribution of social organizations: the number of social organizations on west side of the line is considerately lower than in those on the east.

Figure 2.

Distribution of social organizations in China.

The main contributions of this paper are as follows. Firstly, we used the open source data of the Ministry of Civil Affairs of China to construct a pioneering large-scale database of social organizations fusing public policy and geographic information, which is, to our knowledge, the first large-scale database of social organizations for research use. Secondly, we pioneered the application of graph structure to model the development of social organizations that integrate geographic information and public policy. Last, but not least, based on the graph attention mechanism, we propose a new graph attention network integrating textual information of social organizations, and apply it to the task of classifying graph networks based on geographic information and achieve a good result, laying a foundation for exploring the dynamic development model of regional social organizations.

The structure of this paper is organized as follows: Section 1 presents the introduction, with a brief history of social organizations in mainland China and main research ideas of the article. Section 2 introduces several research topics related to this research, including social networks, geographic information systems, natural language processing and graph neural network models. Section 3 focuses on the construction process of our brand new database and some descriptive statistical analysis of the collected data. In Section 4, we propose four basic types of organizational social networks based on the theory of homogeneous and heterogeneous graphs, and attributed network embedding based on BERT and CNN. In Section 5, we investigate the organizational social network using graph machine learning models to explore the relationship between the network and geographic regions to which they belong. In Section 6, we draw conclusions for the paper.

2. Related Topics

2.1. Social Network

Since the 1990s, social networks have become an increasingly popular research topic, not only in social sciences, but also in computer science and physics. Social networks uncover the relations between social entities, as well as intrinsic social structures [6]. A traditional social network is an abstract structure that contains different relationships between people, such as friendship, common interests, and shared knowledge [7].

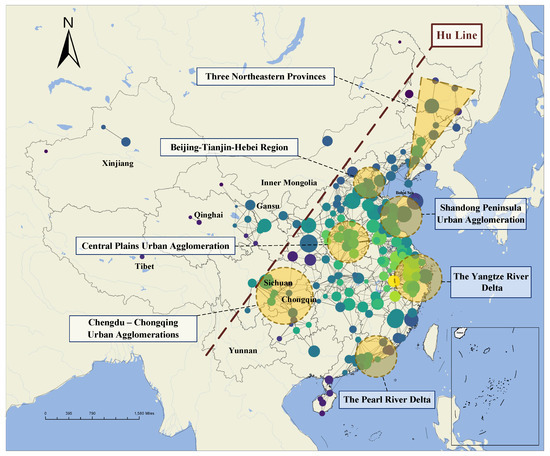

Location-based social network (Figure 3) is a variant of social networks that can create connections between abstract social networks and the real world environment by marking spatial information into the network. As in the Foursquare network, users can comment on events at the exact location where they occurred [8]. In the Twine network, for example, travel routes with GPS tracks are recorded and travel experiences are shared in a community [9].

Figure 3.

A concept map showing the structure of the location-based social network model.

Social network analysis considers individuals in a network, such as a person, a group, or an organization as nodes, with certain dependencies and collaborative relationships among them, which can be represented by connections between points, and the network is composed of nodes and their interrelationships [10]. This method takes the structural relationship between nodes as the guiding principle and considers that any action taken by an individual in the network comes from the individual’s position in the social relationship structure system rather than an individual’s motivation [11,12,13], i.e., the network position of the individual “forces” the actor to take a certain action [2]. Social network analysis can visualize the relationship between network members and the network structure and is often used to explore the key nodes in the network relationship [14].

2.2. Geographic Information System (GIS)

GIS is a computer-supported system which collects, stores, manages, retrieves, analyzes, and describes the location distribution of spatial objects and their related attribute data [15]. The word “geographic” in GIS does not refer to geography in a narrow sense, but refers to the spatial data, attribute data, and related data obtained on the basis of the geographic coordinate reference system in a broad sense.

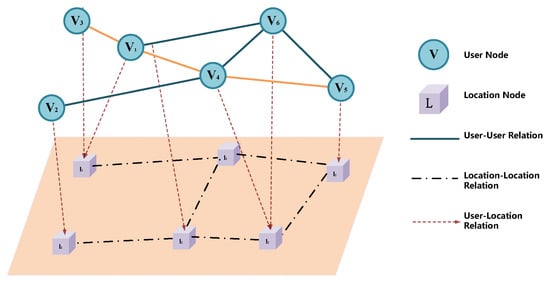

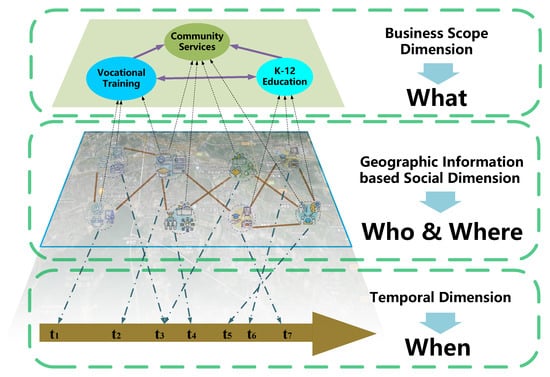

Spatial data usually consists of three types of information: location, spatial relationships, and non-spatial attributes [16]. Location, namely, geometric coordinates, is used to determine the spatial position of spatial objects in the geographic coordinate system. Spatial relations describe the spatial connections between spatial objects, mainly covering metric relations, such as distance between spatial objects, extension relations, or orientation relations, which indicate the orientation between spatial objects. Topological relations indicate the relationship between spatial objects, such as connectivity or adjacency. Non-spatial properties are properties that are not relevant to geometric position. The establishment and data mining of a spatial database is an important research direction in GIS, and Figure 4 shows us the idea of geographic information mining for social organizations in this paper [17].

Figure 4.

A concept map that has analyzed the geographic information system of social organizations.

2.3. Natural Language Processing

The language people use to communicate in daily life is natural language, and so is the text content in the dataset we construct. Text is relatively standardized, with relatively complete grammatical and syntactic and structural information. The goal of Natural language processing (NLP) is to bridge the gap between natural language and machine language [18], using calculation power to analyze the structure and syntax of natural language and extract information from the text content [19]. The main categories involved in natural language processing are word division, lexical annotation, syntactic analysis, sentiment recognition, automatic translation, text summarization [20], knowledge graph [21], and so on.

English text has a natural advantage because each word is separated from each other by a space, while for Chinese text, there is no division among words; furthermore, Chinese text needs to be divided to form a separate word order [22]. The emergence of word-splitting tools has lowered the threshold for high-quality word splitting of text; Jieba is a easy-to-use word splitting tool for Chinese text [23].

The lexical properties refer to the basic attributes of words, and lexical annotation is the process of marking words with names, gerunds, adjectives, adverbs, or other lexical properties. The lexical annotation with machine learning is mainly performed by using some feature values extracted from the data by neural networks. In recent years, deep learning models such as convolutional neural networks and LSTM (long short-term memory network) have also been used for lexical annotation. We choose the BERT model, which is built on top of the transformer and has powerful language representation and feature extraction capabilities. For a given text corpus, the input representation consists of a word vector, a segmented embedding vector, and a positional embedding vector summation, which is then passed through a bidirectional transformer encoder to obtain the corresponding text word vector output. Its extended models are mostly based on its model architecture to design novel language learning tasks, and then trained on domain-specific large-scale text corpus to obtain new models.

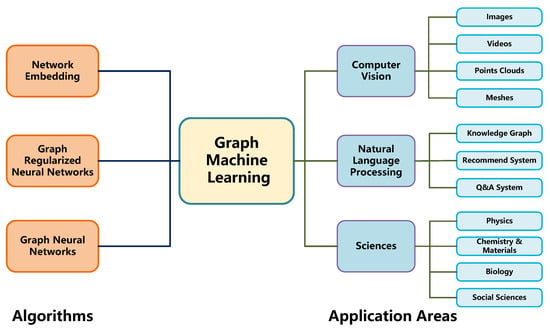

2.4. Graph Machine Learning

Since the recent research focus on graph-structured data, a variety of machine learning algorithms have been proposed for representation learning in graphs, which, based on whether the labeled data are available, can be generally divided into three main categories [24]: network embedding (such as graph autoencoders), graph regularized neural networks, and graph neural networks (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

An illustration of graph machine learning.

Starting directly from the structure of graphs, a graph neural network (GNN) [25] proposes aggregated and combined models aiming to learn differentiable functions over discrete topologies with arbitrary structure [26].

Most of the early graph neural network models [27] use recurrent neural structures to propagate information about neighbors and select generations until they reach a stable immobile point to learn the representation of the target node. The classical formulation of graph neural networks is as follows:

where denotes the state of node u at the tth recursion; denotes the recursive function; denotes the set of neighboring nodes of node u in the graph; x denotes the feature. The initial state of is a random value, and consists of the features of the node u itself and the edge features of the neighboring nodes v. is the feature of the neighboring node v, and , at times of generation selection. This has the advantage that the formula can be generalized to all nodes in the graph, without the constraints of inconsistency in the number and order of neighboring nodes, and it also gives the graph neural network the ability to process recurrent graphs. However, these studies are computationally expensive, and immobility hinders the diversity of node distributions, which is not conducive to fully learning the representation of nodes.

2.4.1. Graph Convolutional Neural Network

Later, based on the spectral analysis of researchers who defined the convolution operation on the graph [28], the graph convolution network (GCN, graph convolution network) came into being.

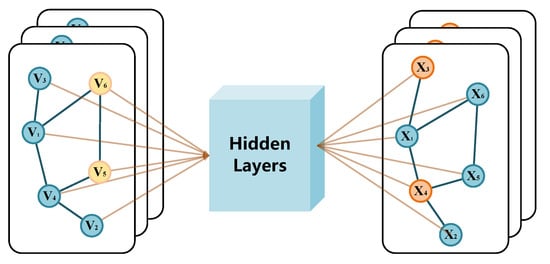

A graph convolutional neural network (GCN) is a fusion algorithm that applies graph structure data to traditional convolutional neural networks (Figure 6), and as a powerful tool for extracting features, it can make good use of neighborhood graphs constructed in a simple KNN so that the learned feature representation contains two different types of information: feature information of the sample nodes and their associated neighborhoods.

Figure 6.

Basis structure of GCN.

A common graph deep neural network consists of a cascade of multiple graph convolution layers, each of which can be represented as

denotes the feature of the th layer, denotes the feature of the kth layer. is the normalized adjacency graph matrix, denotes the parameters of the kth layer of the graph neural network, and denotes the activation function. Assuming that the activation function is not considered and the weight matrix is ignored, we can obtain . This means that H depends only on the degree of the nodes, which indicates that as the number of layers increases, the model loses the discriminative information provided by the node features, and therefore the features appear to be oversmoothed. Therefore, when the number of layers of the network deepens, the final features learned by the graph neural network lose the uniqueness of the sample points themselves, which affects the performance of clustering.

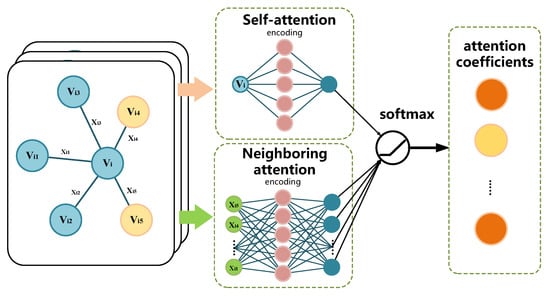

2.4.2. Graph Attention Neural Network

A graph attention network (GAT) is a graph neural network architecture proposed by Petar Veličković et al. [29], which improves the classical graph neural network by combining graph convolution and attention mechanism.The basic structure of GAT is shown in Figure 7. GAT computes the attention score on the input graph, which represents the importance of the input mapping to the output state. Self-attention is introduced to determine the attention score of the input graph preprocessed by GCN. When each node updates the output of the hidden layer, attention is computed on its neighboring nodes. Each node and its neighboring nodes compute attention in parallel and can assign arbitrary weights to neighboring nodes.

Figure 7.

Structure of graph attention neural network.

Graph attention networks have a wide range of applications in social sciences; Weiping Song et al. [30] modeled social interactions among pedestrians by graph attention networks to predict their trajectories. V. Kosaraju et al. [31] constructed dynamic graph attention neural networks to build online community recommendation systems based on dynamic user behavior and environment-related social influences. J. Piao et al. [32] predicted socioeconomic relationships among customers by considering their demographics, past behaviors, and social network structure.

In view of the previous research on graph attention networks in social sciences, this paper uses graph attention networks as a social organization network structure feature extraction layer to learn social organization network graph features.

3. The Novel Database of Social Organizations in China

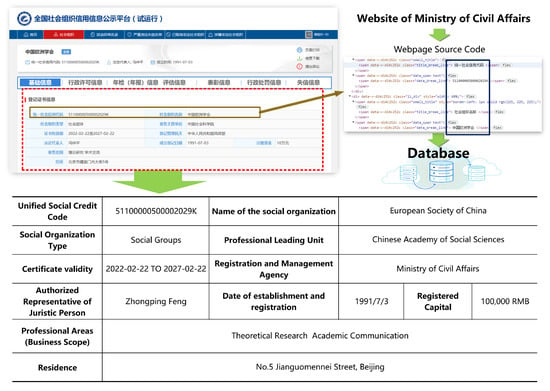

In China, public access to information related to social organizations can be browsed online through the National Social Organization Credit Information Public Platform (hereafter, the Platform; https://xxgs.chinanpo.mca.gov.cn/gsxt/newList, accessed on 17 May 2022), supervised by the Ministry of Civil Affairs. The Platform stores all of the basic information entries of each organization, Figure 8 is an example.

Figure 8.

A flow chart showing the database construction based on open data platform of the Ministry of Civil Affairs of China.

However, users can only search for information about one specific organization by entering keywords or the exact social credit code, and can only search for one organization at a time, which severely limits the amount of data that researchers can access for research purposes. Furthermore, users have to pass a human–machine verification operation before every single search. In China, where tens of thousands of social organizations are established every year and the Platform stores all of their basic information, if we try to manually perform the acquisition of all social organizations, millions of searches and downloads are required, which is a huge drain in terms of manpower, money, and time, thus limiting or even preventing the role of big data analysis of social organizations in China. Therefore, the use of web data scraping methods for bulk collection and collation of web data is a must.

3.1. Design and Implementation of Web Crawlers

In this paper, we have written a web crawler with data processing program using Python. The web crawler accesses web pages through hypertext transfer protocol (HTTP). The web crawler generally sets the starting set of seed URLs at the beginning, and after establishing a successful connection with the seed URL server, it parses the contents of the corresponding web pages to obtain all the URLs that can be linked from them [33]. It then searches the web page and downloads the target data, which, as is shown in Figure 8, may be encoded in Hypertext Markup Language (HTML) or obtained through links to JS codes. The number of pages visited and searched depends on the parameters set in the program prior to startup. New URLs are then added to the queue to be crawled until the termination conditions are met, and then the parsed results are stored. The crawler we designed fully complies with the prescribed robots protocol and sets the request information for legal requests. The final step is to transform the data and integrate it into a structure suitable for analysis, and the obtained data in Datafram format are saved as CSV files to the cloud for subsequent calls.

As seen in Table 1, each web page contains the details of a specific social organization. After using regular expressions to obtain the body information, we can obtain the text information easily. However, difficulties in the design and writing of the web crawler program lie in how to crack the encryption of the web URLs (Figure 9), skipping the human–machine verification and searching process, and directly obtaining the web address of each social organization point-to-point.

Table 1.

The detailed elements published in the platform can be used as the basic variables that constitute the database.

Figure 9.

Composition rules and decryption of target URLs.

Through the collection and collation of the basic components of social organizations, which are shown in Table 1, data cleaning was carried out to establish a database of social organization. As of January 2022, we have accessed a total of 1.09 million social organizations and their related information. We declare that the data obtained in this study are public and for research use only, without any commercial and malicious behavior. In addition, for legal reasons, we do not publish the exact technical details of how to break the encryption on the website.

3.2. Data Cleaning and Geographic Information Integration

The quality of data plays a key role in the results of data mining. Data cleaning usually includes dealing with missing values and redundant values, as well as noise. The text collected by web crawlers is mostly unstructured data containing data noise. By observation, we found that there was a certain percentage of noise in the acquired data, which is of no help for understanding the semantics of the text. We deduce that, since the Platform of the Ministry of Civil Affairs only serves as a tool for integrating and publishing information, and detailed data are filled in and uploaded by local civil affairs departments, problems and errors may arise during the uploading process, such as meaningless symbols or tags, JS codes, traditional or abandoned Chinese characters, line breaks, different time formats, and so on, so we need to clean and standardize the obtained data and integrate the relevant geographical information of each social organization to provide a high-quality build of a complete and usable database for research use.

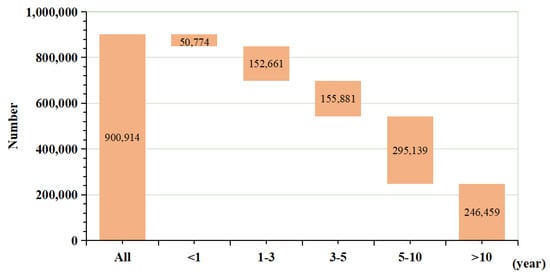

After normalizing the temporal data, the study of the temporal dimension could be carried out. For example, Figure 10 uses the data of the registration time of the organizations. Among the established social organizations, 50,774 have been in existence for less than one year, 152,661 have been operating for one to three years, 155,881 have been operating between three and five years, the largest proportion of social organizations have been functioning for five to ten years, and even more than 240,000 have been running for more than 10 years.

Figure 10.

Social organizations categorized by the time of operation.

Meanwhile, the geographical information of social organizations can be obtained by two different methods. The first one is to use the registered address information contained in the database, by calling the API to search and obtain its precise latitude and longitude coordinates which, however, is relatively time-consuming and cannot be applied on a large scale. There is another method which we reckon is a more efficient way to categorize the locations directly according to the coding rules of the unified social credit code. As is shown in Table 2, the unified social credit code, a unique, 18-digit national registration number, follows a standard pattern, which means that we can directly use the 6-digit area code embedded in the unified social credit code to locate social organizations down to the exact administrative division of the county where they are located.

Table 2.

The composition rules of the Chinese social unified credit code.

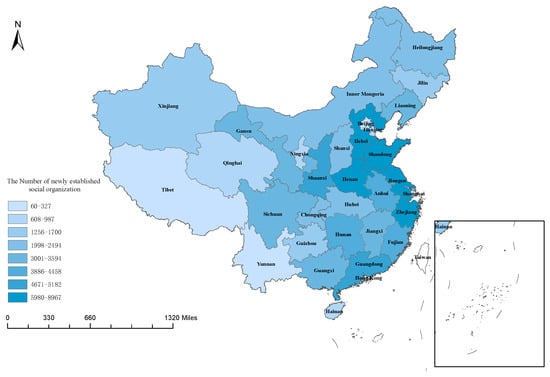

After obtaining the basic geographical information of social organizations, we can explore and study social organizations in the spatial dimension. The map in Figure 11 displayed here shows how the number of newly established social organization varies by province. The shade of the province corresponds to the magnitude of the indicator.The darker the shade, the higher the value.

Figure 11.

The number of newly established social organizations between August 2020 and August 2021.

3.3. Text Data Analysis

Since most of the information in the database is Chinese text, how to obtain and analyze the features and semantic information of the Chinese text is of great significance to our study, which would determine the research direction. We firstly performed a basic word separation process on the names of social organizations and their business introduction in the database.

Table 3 shows us clearly the frequency of the occurrence of high-frequency words of different lexicons, enabling us to have a more intuitive sense of the development of social organizations in China. The first line of each cell is the Chinese translation of the word, the second line in parentheses is the original Chinese text, and the third line in italics is the number of times the word appears. The shade of the cell corresponds to the magnitude of the indicator. The darker the shade, the higher the value. In the listed categories, refers to the gerunds, n refers to the noun, s refers to the preposition, refers to the noun idiom, and refers to the adjective.

Table 3.

Top 10 popular keywords ranked by the occurrence frequency.

Table 3 reveals that the nouns in the results are all suffixes of certain words. The words “kindergarten” and “school” appearing after “association” is a reflection of the current boom in China’s education market. It corresponds to the fact that private education in China as the essential form of social forces has developed rapidly and accumulated effective experience in the dissemination of knowledge. Note that the gerunds “poverty alleviate” is in first place, which infer that the Chinese government focuses on improving the living conditions of poor households and helping poor areas to develop production and change the face of poverty, while social organizations, as a third-party force, complement the synergistic effect of multi-subject governance. Similarly, we notice that the word “pension” is in second place and “nursing homes” is in sixth place, reflecting the serious aging situation in China and the active participation of social organizations in the pension business.

4. Graph Model in Organizational Social Networks

4.1. Overview of the Graph Structure

Data exist in a plethora of different forms and sizes, but most of them can be presented as two types: structured data and unstructured data (Figure 12).

Figure 12.

Euclidean structure data and Non-Euclidean structure data.

Structured data, for example, temperature, names, dates, stock information, location, and pictures, comprise clearly defined data types with patterns in a standardized format that enable them to organize searchable information efficiently. Modern machine learning algorithms have achieved amazing performance in processing structured data (such as AlphaGo [34], ResNet [35], etc.).

Graph, a typical unstructured data, is more flexible and variable compared with structured data, which, at the same time, makes it relatively more difficult to perform machine learning tasks on graph structured data. However, due to the wide application of graph models in human society, it is of great importance to study graph and related machine learning algorithms. One of the most vivid applications of graph structured data is the virus transmission models being used to characterize the transmission pattern of viruses across countries constructed during the COVID-19 pandemic [36], which played a huge role in controlling the spread of epidemics.

A graph , consisting of two sets, nodes V (also called vertices) and edges E (also called arcs), is able to represent entities and their relations in the graph structured data. An edge represents an edge pointing from to , and the neighboring nodes of node v are defined as . The adjacency matrix A is a matrix of size ; n represents the number of nodes in the graph. If there exists an edge connecting nodes and , then , otherwise . A node in a graph has attributes or features which is the attribute matrix of the node, or called the feature matrix of the node, where represents the attribute vector of the node v. A graph may also have attributes of edges , is the attribute matrix of edges, where represents the attribute vector of edge , and c represents the dimension of the attribute. The attributes and features represent the same meaning.

4.2. Homogeneous Networks of Organizations

Homogeneous networks, which use a single network architecture, have the same node and link types. Homogeneous networks are network structures composed of the same kind of nodes and link types.

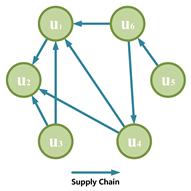

As shown in Table 4, we introduce two types of homogeneous networks: competition and cooperation networks, and supply-chain networks. Each of these types is potentially useful in modeling social organizations and their relationships.

Table 4.

Homogeneous networks.

4.3. Heterogeneous Networks of Organizations

Heterogeneous networks have a different set of node and link types. The advantages of heterogeneous networks are the abilities to represent and encode information and relationships from different perspectives. During the development process of social organizations, different types of social entities are involved, for example, government, policymakers, policies, services, community members, and, of course, social organizations. Table 5 below provides two types of heterogeneous networks for modeling the relationships between social organizations and other social entities: policy networks and service networks.

Table 5.

Heterogeneous networks.

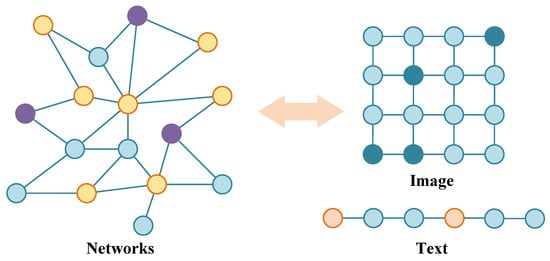

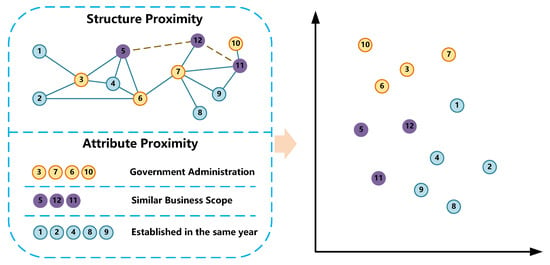

4.4. Attributed Network Embedding with Text Information

In addition to the structural features of the social organization network, the text content in the database, such as name, business scope, registered capital, and so on, needs to be processed in order to obtain the basic information of the social organization before being input into the machine learning model (Figure 13).

Figure 13.

Attributed social network embedding.

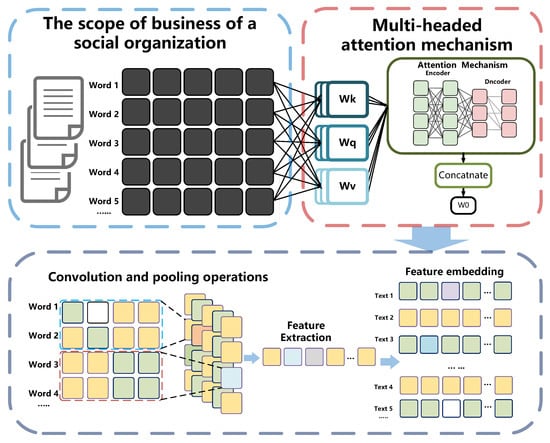

In this paper, the length of the text content is limited to L. If the length of the text content exceeds L, then the excess part would be truncated, while if the length of the text content is less than L, placeholders would be used to fill the text until the length is L. denotes the word vector of the jth word in the text , so the vector of the text can be expressed as where , denotes the word vector of the second word in the text , denotes the word vector of the second word in the text , and denotes the word vector of the Lth word in the text (Figure 14).

Figure 14.

Attention mechanism: natural language processing.

4.4.1. Multi-Headed Self-Attention Mechanism

In the next step, we adopt a multi-headed self-attentive mechanism to update the word vectors in the text content of each social organization in the database. The multi-headed self-attentive mechanism can explore the connections among word vectors from different perspectives, thus improving the expressiveness of word vectors. h denotes the number of heads of the self-attentive mechanism. Consider a self-attentive mechanism with h heads; j denotes the ordinal number of the head, and the three input matrices of the self-attentive mechanism for the jth head are denoted as query matrix , matrix , and the value matrix . Taking the embedded vector of text ,

as an example: For simplicity, we use X to denote , then we have , and , where , denotes the parameter matrix corresponding to the key matrix of the jth head in the self-attentive mechanism, denotes the parameter matrix corresponding to the query matrix of the jth head in the self-attentive mechanism, and denotes the parameter matrix corresponding to the value matrix of the jth head in the attention mechanism. The output of the jth head of the self-attentive mechanism is represented as

where . In this paper, the output of the h—headed self-attentive mechanism is expressed as , is the output of the self-attentive mechanism for the 1st head, is the output of the self-attentive mechanism of the 2nd head, and is the output of the self-attentive mechanism of the hth head, then we have

where , , and denotes the parameter matrix of the h—head self-attentive mechanism.

4.4.2. Convolutional Neural Networks and Pooling Operations

Then, we use CNN and pooling operations to obtain semantic information from the text contents in the database. We use convolution kernels to perform the convolution operation on the text vector , where denotes the e th word vector to the th word vector in the text content ; and k denotes the perceptual field size of the kernel. For all word vectors in , the convolution operation can be expressed as

where is the feature obtained, and * denotes the convolution operation, is the bias term, is the activation function, such as , and e denotes the ordinal number, namely the eth word vector in the message . Finally, by convolving all possible windows in the text vector X using the convolution kernel W, the feature map of the text is obtained as and , where denotes the output features of the first sliding window in the CNN, denotes the output features of the second sliding window, and denotes the output features of the th sliding window, after which the feature map t is processed using a maximum pooling with step size , . In this paper, we apply sense field sizes of . After the maximum pooling operation, three feature vectors of length will be obtained, and then be spliced together to obtain the text and the final text content feature , which will at last be spliced with the graph-structured feature of social organization networks.

6. Conclusions

Society is a complex system whose development comes from the collision and convergence of different social entities. In this paper, we construct a novel database of social organizations in China with related information, using the open data platform provided by the Ministry of Civil Affairs of the People’s Republic of China, which, to our knowledge, is one of the few social organizational databases that have been applied to computational social science research. We believe that the construction of this database can provide more and more powerful help for researchers to explore the development of Chinese social organizations and the macro changes of Chinese society in the future.

With the database, we explored the network structure composed of social organizations and related social entities. We proposed four types of social organization networks based on graph theory, trying to structuralize the development patterns of social organizations in different regions, which are characterized by local policy, economic, and cultural factors. We construct a graph-model-based organizational geosocial network(OGN), with the help of natural language processing(NLP) technology to embed the textual information into the network, which enables it to fuse more dimensions of information, thus representing richer structural and semantic features of the complex network.

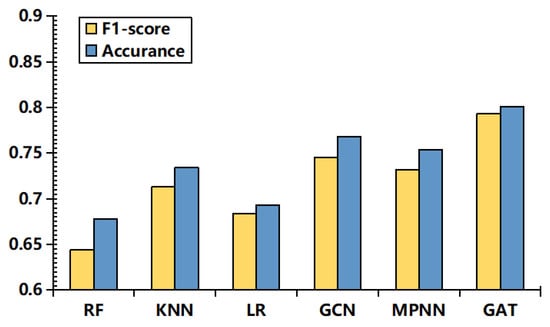

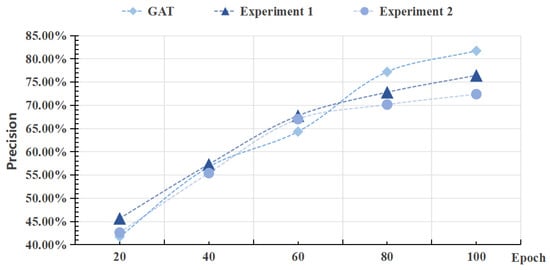

Using machine learning models, we conducted exploratory research on the relationship between the development patterns of organizational social networks and the geographic zones to which they belong. Our machine learning models achieved relatively good results on the training data, with an average accuracy rate of . However, it is important to emphasize that our aim is not simply to pursue the accuracy or to create a new state of the art (SOTA), but to explore the correlation between the graph-structured network data and the socioeconomic differences embedded in geographic space through the geographic-area-affiliation prediction task.

In future research, we hope to build larger and more complex graph network structures from a multidimensional perspective [51,52], and we also hope to highlight the role of interpretable machine learning [53] to decrease the black box nature of deep learning and help us gain an in-depth understanding of the causal relationship between the development of social organization and relevant policy, economic, and cultural factors.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Xinjie Zhao, Hao Wang, and Shiyun Wang; methodology, Xinjie Zhao and Hao Wang; validation, Xinjie Zhao, Shiyun Wang, and Hao Wang; formal analysis, Shiyun Wang and Hao Wang; data curation, Xinjie Zhao; writing—original draft preparation, Xinjie Zhao and Shiyun Wang; writing—review and editing, Xinjie Zhao, Hao Wang, and Shiyun Wang; visualization, Xinjie Zhao and Shiyun Wang. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is supported by the Youth Project of the National Social Science Foundation of China “Research on Unbalanced and Insufficient Development of Social Organizations Based on Big Data Method” (20CSH089).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

Since our database has just been developed and the amount of data is huge, there are still some instability factors in it. Therefore, after some more in-depth testing, we will look for a suitable opportunity to publish it, and if you are interested in the database, you can also contact us directly to collaborate on the research.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflict of interest.

References

- Yang, A.; Cheong, P.H. Building a Cross-Sectoral Interorganizational Network to Advance Nonprofits: NGO Incubators as Relationship Brokers in China. Nonprofit Volunt. Sect. Q. 2019, 48, 784–813. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ianni, M.; Masciari, E.; Sperli, G. A survey of Big Data dimensions vs Social Networks analysis. J. Intell. Inf. Syst. 2021, 57, 73–100. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wasserman, S.; Faust, K. Social Network Analysis: Methods and Applications; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, MA, USA, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- Xiang, Y.; Fujimoto, K.; Schneider, J.; Jia, Y.; Zhi, D.; Tao, C. Network context matters: Graph convolutional network model over social networks improves the detection of unknown HIV infections among young men who have sex with men. J. Am. Med. Inform. Assoc. 2019, 26, 1263–1271. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Peng, H.; Li, J.; Song, Y.; Yang, R.; Ranjan, R.; Yu, P.S.; He, L. Streaming Social Event Detection and Evolution Discovery in Heterogeneous Information Networks. ACM Trans. Knowl. Discov. Data 2021, 15, 1–33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Boyd, D.M.; Ellison, N.B. Social Network Sites: Definition, History, and Scholarship. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2007, 13, 210–230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Dhand, A.; White, C.C.; Johnson, C.; Xia, Z.; De Jager, P.L. A scalable online tool for quantitative social network assessment reveals potentially modifiable social environmental risks. Nat. Commun. 2018, 9, 3930. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonacich, P. Some unique properties of eigenvector centrality. Soc. Netw. 2007, 29, 555–564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gong, H.; Chen, C.; Bialostozky, E.; Lawson, C.T. A GPS/GIS method for travel mode detection in New York City. Comput. Environ. Urban Syst. 2012, 36, 131–139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borgatti, S.; Mehra, A.; Brass, D.; Labianca, G. Network Analysis in the Social Sciences. Science 2009, 323, 892–895. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Stephure, R.J.; Boon, S.D.; MacKinnon, S.L.; Deveau, V.L. Internet Initiated Relationships: Associations between Age and Involvement in Online Dating. J. Comput.-Mediat. Commun. 2009, 14, 658–681. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Kane, G.C.; Alavi, M.; Labianca, G.; Borgatti, S.P. What’s Different About Social Media Networks? A Framework and Research Agenda. MIS Q. 2014, 38, 275–304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Espín-Noboa, L.; Wagner, C.; Strohmaier, M.; Karimi, F. Inequality and inequity in network-based ranking and recommendation algorithms. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 2012. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Shiau, W.L.; Dwivedi, Y.K.; Yang, H.S. Co-citation and cluster analyses of extant literature on social networks. Int. J. Inf. Manag. 2017, 37, 390–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Sanchez-Lozano, J.M.; Teruel-Solano, J.; Soto-Elvira, P.L.; Socorro Garcia-Cascales, M. Geographical Information Systems (GIS) and Multi-Criteria Decision Making (MCDM) methods for the evaluation of solar farms locations: Case study in south-eastern Spain. Renew. Sustain. Energy Rev. 2013, 24, 544–556. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Quartulli, M.; Olaizola, I. A review of EO image information mining. Int. J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2013, 75, 11–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Liao, S.H.; Chu, P.H.; Hsiao, P.Y. Data mining techniques and applications—A decade review from 2000 to 2011. Expert Syst. Appl. 2012, 39, 11303–11311. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tenney, I.; Das, D.; Pavlick, E. BERT rediscovers the classical NLP pipeline. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1905.05950. [Google Scholar]

- Manning, C.; Surdeanu, M.; Bauer, J.; Finkel, J.; Bethard, S.; McClosky, D. The Stanford CoreNLP Natural Language Processing Toolkit. In Proceedings of the 52nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: System Demonstrations, Baltimore, MD, USA, 23–24 June 2014; pp. 55–60. [Google Scholar]

- Piktus, A.; Petroni, F.; Karpukhin, V.; Okhonko, D.; Broscheit, S.; Izacard, G.; Lewis, P.; Oğuz, B.; Grave, E.; Yih, W.t.; et al. The Web Is Your Oyster—Knowledge-Intensive NLP against a Very Large Web Corpus. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2112.09924. [Google Scholar]

- Ribeiro, M.T.; Singh, S.; Guestrin, C. Model-agnostic interpretability of machine learning. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1606.05386. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.; Che, W.; Liu, T.; Qin, B.; Wang, S.; Hu, G. Revisiting Pre-Trained Models for Chinese Natural Language Processing. In Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP 2020; Association for Computational Linguistics: Stroudsburg, PA, USA, 2020; pp. 657–668. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Zheng, J.; Chen, Q.; Liu, G.; Chen, S.; Chu, B.; Zhu, H.; Akinwunmi, B.; Huang, J.; et al. Health Communication Through News Media During the Early Stage of the COVID-19 Outbreak in China: Digital Topic Modeling Approach. J. Med. Internet Res. 2020, 22, e19118. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chami, I.; Abu-El-Haija, S.; Perozzi, B.; Ré, C.; Murphy, K. Machine Learning on Graphs: A Model and Comprehensive Taxonomy. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2005.03675. [Google Scholar]

- Wu, Z.; Pan, S.; Chen, F.; Long, G.; Zhang, C.; Yu, P.S. A Comprehensive Survey on Graph Neural Networks. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2021, 32, 4–24. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed] [Green Version]

- Zhou, J.; Cui, G.; Hu, S.; Zhang, Z.; Yang, C.; Liu, Z.; Wang, L.; Li, C.; Sun, M. Graph neural networks: A review of methods and applications. AI Open 2020, 1, 57–81. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bandinelli, N.; Bianchini, M.; Scarselli, F. Learning long-term dependencies using layered graph neural networks. In Proceedings of the 2010 International Joint Conference on Neural Networks (IJCNN), Barcelona, Spain, 18–23 July 2010; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Tong, H.; Xu, J.; Maciejewski, R. Graph convolutional networks: A comprehensive review. Comput. Soc. Netw. 2019, 6, 11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Veličković, P.; Cucurull, G.; Casanova, A.; Romero, A.; Liò, P.; Bengio, Y. Graph Attention Networks. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1710.10903. [Google Scholar]

- Song, W.; Xiao, Z.; Wang, Y.; Charlin, L.; Zhang, M.; Tang, J. Session-based Social Recommendation via Dynamic Graph Attention Networks. In Proceedings of the Twelfth ACM International Conference on Web Search and Data Mining, Melbourne, Australia, 11–15 February 2019; pp. 555–563. [Google Scholar]

- Kosaraju, V.; Sadeghian, A.; Martín-Martín, R.; Reid, I.; Rezatofighi, S.H.; Savarese, S. Social-BiGAT: Multimodal Trajectory Forecasting using Bicycle-GAN and Graph Attention Networks. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1907.03395. [Google Scholar]

- Piao, J.; Zhang, G.; Xu, F.; Chen, Z.; Li, Y. Predicting Customer Value with Social Relationships via Motif-based Graph Attention Networks. In Proceedings of the Web Conference, Ljubljana, Slovenia, 19–23 April 2021; pp. 3146–3157. [Google Scholar]

- Baek, H.; Ahn, J.; Choi, Y. Helpfulness of Online Consumer Reviews: Readers’ Objectives and Review Cues. Int. J. Electron. Commer. 2012, 17, 99–126. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silver, D.; Schrittwieser, J.; Simonyan, K.; Antonoglou, I.; Huang, A.; Guez, A.; Hubert, T.; Baker, L.; Lai, M.; Bolton, A.; et al. Mastering the game of Go without human knowledge. Nature 2017, 550, 354–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep Residual Learning for Image Recognition. arXiv 2015, arXiv:1512.03385. [Google Scholar]

- Luo, C.; Ma, Y.; Jiang, P.; Zhang, T.; Yin, F. The construction and visualization of the transmission networks for COVID-19: A potential solution for contact tracing and assessments of epidemics. Sci. Rep. 2021, 11, 8605. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bengtsson, M.; Kock, S. “Coopetition” in Business Networks—To Cooperate and Compete Simultaneously. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2000, 29, 411–426. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Klimas, P. Organizational culture and coopetition: An exploratory study of the features, models and role in the Polish Aviation Industry. Ind. Mark. Manag. 2016, 53, 91–102. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Roininen, S.; Westerberg, M. Network Structure and Networking capability among new ventures: Tools for competitive advantage or a waste of resources? (summary). Front. Entrep. Res. 2008, 28, 3. [Google Scholar]

- Krajewski, L.J.; Malhotra, M.K.; Ritzman, L.P. Operations Management. Processes and Supply Chains, 11th ed.; Pearson: Boston, MA, USA, 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, J. Networks, Network Governance, and Networked Networks. Int. Rev. Public Adm. 2006, 11, 19–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leicht, A.; Heiss, J.; Byun, W.J. Issues and Trends in Education for Sustainable Development; Education on the Move; UNESCO Publishing: Paris, France, 2018; p. 271. [Google Scholar]

- South, J.; Button, D.; Quick, A.; Bagnall, A.M.; Trigwell, J.; Woodward, J.; Coan, S.; Southby, K. Complexity and Community Context: Learning from the Evaluation Design of a National Community Empowerment Programme. Int. J. Environ. Res. Public Health 2020, 17, 91. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Wang, M.; Yang, S.; Sun, Y.; Gao, J. Discovering urban mobility patterns with PageRank based traffic modeling and prediction. Phys.-Stat. Mech. Its Appl. 2017, 485, 23–34. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, S.; Li, X.; Zong, M.; Zhu, X.; Wang, R. Efficient kNN classification with different numbers of nearest neighbors. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2017, 29, 1774–1785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosmer, D.W., Jr.; Lemeshow, S.; Sturdivant, R.X. Applied Logistic Regression; John Wiley & Sons: Hoboken, NJ, USA, 2013; Volume 398. [Google Scholar]

- Grover, A.; Leskovec, J. node2vec: Scalable feature learning for networks. In Proceedings of the 22nd ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, San Francisco, CA, USA, 13–17 August 2016; pp. 855–864. [Google Scholar]

- Gilmer, J.; Schoenholz, S.S.; Riley, P.F.; Vinyals, O.; Dahl, G.E. Neural Message Passing for Quantum Chemistry. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Sydney, Australia, 11 August 2017; pp. 1263–1272. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, S.; He, K.; Girshick, R.; Sun, J. Faster R-CNN: Towards Real-Time Object Detection with Region Proposal Networks. arXiv 2016, arXiv:1506.01497. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Pennington, J.; Socher, R.; Manning, C. Glove: Global Vectors for Word Representation. In Proceedings of the 2014 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Doha, Qatar, 25–29 October 2014; pp. 1532–1543. [Google Scholar]

- Aliakbary, S.; Motallebi, S.; Rashidian, S.; Habibi, J.; Movaghar, A. Distance metric learning for complex networks: Towards size-independent comparison of network structures. Chaos Interdiscip. J. Nonlinear Sci. 2015, 25, 023111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, D.; Yin, J.; Zhu, X.; Zhang, C. Network Representation Learning: A Survey. IEEE Trans. Big Data 2020, 6, 3–28. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [Green Version]

- Belle, V.; Papantonis, I. Principles and Practice of Explainable Machine Learning. Front. Big Data 2021, 4, 688969. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Publisher’s Note: MDPI stays neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations. |

© 2022 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).