Abstract

Robots and artificial intelligence have revolutionized the healthcare sector. Patient transportation within hospitals is emerging as a critical application; however, reducing errors and inefficiencies caused by human intervention and ensuring safe, efficient, and reliable movement of patients are necessary. This study provides a comprehensive review of research and technological trends in healthcare robotics, focusing on the design, algorithms, and applications of following robots for patient transportation. We examine foundational robotic algorithms, sensor and navigation technologies, and human–robot interaction techniques that enable robots to safely follow patients and assist medical personnel. Additionally, we survey the evolution of transportation robots across industries and highlight current research on hospital-specific following robots. Finally, we survey the current research and trends in following robots and robots for patient transportation to assist medical personnel in real-world healthcare applications. A comprehensive and in-depth understanding of the design and application of following robots can be pivotal to guiding future research on following robots and laying the foundation for their commercialization in healthcare.

1. Introduction

The Fourth Industrial Revolution has fueled technological advancement in many fields. Healthcare is also advancing rapidly through innovative technologies, such as digital twins, tactile internet (TI), and artificial intelligence (AI), which profoundly impact patient treatment and management and healthcare service delivery. Technological advances include modeling patient biometrics, enabling real-time monitoring, low communication latency, and telemedicine and surgery support, as well as providing a range of functions, from updating medical information to predicting diseases. Therefore, medical robotics is being designed and implemented to contribute to advancements in the field. The types of robots currently being researched include mobile robots, which detect their surroundings and perform tasks while traveling to a given destination; collaborative robots, in which multiple robots work together to perform large-scale tasks; and service, medical, and military robots. Mobile robots are becoming increasingly necessary in modern healthcare systems and need to be researched from various aspects. These aspects include easing the workload of medical staff, preventing infections, caring for older adults in an aging society, and requiring high adaptability to irregular environments. Thus, research is being conducted on robots that follow caregivers or medical staff, transport patients, and provide medical supplies.

This study thoroughly reviewed the current state of research on using robots in healthcare, their potential applications in healthcare, and future research directions. In terms of technology, the elements of robots can be divided into sensors and algorithms, and research is being conducted to develop and improve their ability to interact with the environment. The developed sensors and algorithms are gaining attention in human tracking and efficient pathfinding. Research is also expanding into human–robot interactions.

Researchers are developing robots to assist healthcare workers and caregivers with medical supplies and patient transportation. The developed robots are being evaluated in real-world environments to facilitate their commercialization. In the first section of this paper, we explore technology evolution in the Fourth Industrial Revolution and discuss the advancements and applications of key technologies, such as digital twins, the Internet of Things (IoT), TI, and AI. The next section examines the status and future trends of following robotics across industries, excluding healthcare, and analyzes the research on the sensors and algorithms used for detection and following. In the final section, we present the results obtained after designing, implementing, and evaluating a realistic robot for the medical field. The conclusion includes a comprehensive review of state-of-the-art research on the design and application of following robots.

We used the Google Scholar database for the last 10 years (2014–2025) to find diverse and comprehensive research on following robots. The searches were title-based, and the search terms included the following keywords, which were adjusted for each section: “robot,” “follow,” “tracking,” “navigation,” “people,” “person,” “human,” “leader”, and “line.”

Healthcare keywords included the following: “robot,” “follow,” “nurse,” “patient,” “medical,” and “hospital.”

However, “surgery” was excluded from the search to exclude articles related to surgical robots, and “bed” and “transfer” were added to examine the literature related to patient transfer and acceptability assessment. We used the search terms to identify studies of interest and did not impose restrictions on publication journals or study designs.

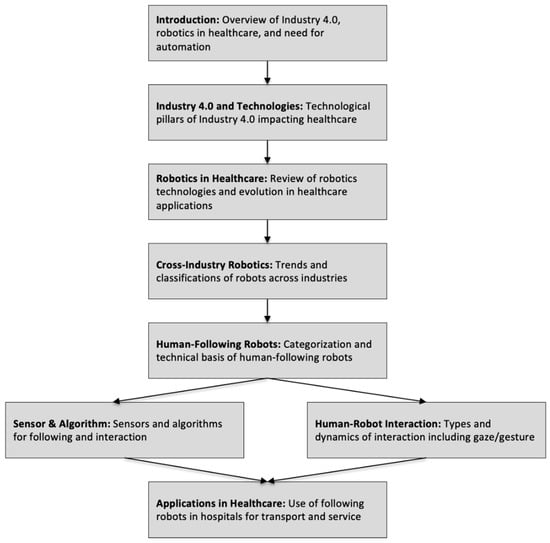

We followed the research process shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

The overall procedure of the literature review on following robots.

2. Fourth Industrial Revolution and Autonomous Mobile Robots

Recently, AI, Internet of Things (IoT), and big data analytics have driven innovation across society. Javaid et al. [] analyzed the trends in healthcare and related sectors resulting from this industrial revolution and concluded that Industry 4.0 technologies are beneficial in healthcare and related sectors, and their impact is expected to grow in the future. These benefits include maximizing productivity, increasing accuracy, saving time and money, improving quality, reducing paperwork, creating customized implants and equipment, and applying controlled processes to complex surgeries.

In hospital environments, these technologies are reshaping patient management and mobility systems. For example, 3D printing and scanning technologies can be used to manufacture patient-specific tools that can reduce tissue damage during surgery, while IoT-enabled devices support real-time monitoring of patient vitals and remote patient care. The emergence of 5G-based TI has further improved latency, reliability, and bandwidth, enabling real-time robotic control critical for telesurgery, telemedicine, and autonomous patient transportation within hospitals. Through ultralow-latency communication, TI enhances robotic performance in dynamic environments, such as crowded hospital corridors, improving both efficiency and patient safety.

In the healthcare sector, IoT is expected to be increasingly used for remote patient care and management. With the rise of smart homes and cities, healthcare is becoming embedded in these platforms. However, IoT can be delayed when data need to be transmitted and processed in real-time. This latency can be even more pronounced in modern smart applications, such as 5G-based smart homes and cities.

AI and robotics are increasingly integrated in healthcare systems to automate patient transportation, logistics, and surgical support. AI-driven robots can assist with intra-hospital delivery of equipment, medication, and specimens, or even escort patients between departments using autonomous navigation and human-following capabilities. Robotic telesurgery is becoming more important in the medical field because it is convenient, cost-effective, and useful during emergencies. In robotic healthcare, TI minimizes communication failures during remote surgeries to ensure patient safety and make them distance-independent. VR and AR are also being adopted for robotic surgery, surgical simulation, rehabilitation, physical fitness, and skills training. Shen et al. implemented a VR system to simulate cardiovascular disease knowledge and coronary angioplasty procedures in their study []. Lozano-Quilis et al. developed and evaluated a low-cost VR-based rehabilitation system for patients with multiple sclerosis. These VR systems solved some communication latency challenges initially encountered with 4G technology. However, these challenges are still not completely solved, and 5G and TI are critical in overcoming them. Digital twins and IoT technologies drive innovation in modern manufacturing and healthcare, and their integration with TI will enable more advanced technologies and applications. Along with digital twins, IoT, and TI technologies, AI is key in the era of Industry 4.0. Research on AI in healthcare is being conducted. Secinaro et al. [] analyzed the academic literature related to AI in healthcare and provided insights into current applications and future research areas. Typical applications of AI in healthcare include healthcare service management and optimization, disease prediction and diagnosis, and clinical decision support.

AI can provide healthcare professionals with real-time information updates from various data sources, including academic journals, books, and clinical practice. This can increase the efficiency of healthcare services when information needs to be constantly exchanged and updated, such as during the COVID-19 pandemic. AI can process and manage massive data volumes and provide useful insights. Predicting heterogeneity in patient health data, identifying outliers, performing clinical tests on the data, and improving predictive models can be beneficial. Consequential relationships and risk factors can be identified from the raw data to enable diagnosis, treatment, and prognosis in various medical situations. This can replace human judgment or help healthcare providers make better clinical decisions. AI applications in healthcare now extend from clinical decision support and disease prediction to hospital logistics and workflow optimization. Collectively, these advancements illustrate how Industry 4.0 technologies are transforming healthcare into a more connected, intelligent, and mobility-aware ecosystem, where autonomous robots play a central role in patient transportation and hospital efficiency. AI and robotics are expected to converge in healthcare and further enhance innovation and efficiency with other key technologies of the Fourth Industrial Revolution.

This section comprehensively explains the core technological principles enabling robots to make autonomous decisions (AI), communicate with hospital systems (IoT), and move safely (TI). These concepts are critical for understanding the concept and technical background of autonomous mobile robots in hospitals.

Details on robotics are explored in detail in the next section.

3. Comprehensive Review of Robotics Evolution and Applications

Robotics technology is revolutionizing healthcare through innovations that directly enhance patient transportation, mobility, and surgical procedures. In hospital settings, robots improve patient safety and surgical precision with safe patient transfers, intra-hospital delivery tasks, and collaborative surgical procedures, improving both the efficiency and quality of care. Robots can move patients around a hospital while continuously monitoring their condition, enabling faster emergency responses and reducing the physical workload of medical staff. This section aims to review the evolution and current applications of robotics in healthcare, as well as research studies that provide insights into the new possibilities for the future.

3.1. Review Papers on Cross-Industry Robotics

First, we investigated survey studies on common robotics technologies used across industries. Cross-sector research offers valuable insights into navigation, collision avoidance, and autonomous movement, which are foundational for healthcare mobility robots. The research studies reviewed were categorized based on the role of the robot and the algorithms used. Misaros et al. [] analyzed and discussed the current state of autonomous robot development. They introduced assistive robots, autonomous vehicles, carriers, and manipulators. Transport robots have been developed for both human and object mobility, including applications in patient transfer and hospital logistics. Thus, various aspects of transportation robotics have been researched.

Regarding conveyors, research has focused on optimizing the energy cost of the system for a high degree of automation. In contrast, concerning material or object transport, research has focused on safe transportation, including the interaction between navigation robots, trajectory tracking to the desired destination, and collision avoidance, which are all critical in healthcare. Technologies related to transporting objects in hazardous areas, such as stairs, and collision avoidance have been tested in real-world applications. These advancements in research and technology can improve the safety and efficiency of various applications, including patient and luggage transportation. They are expected to be essential in fostering innovation in the medical field and ensuring the health and safety of patients.

Pandey et al. [] provided a comprehensive overview of the various soft computing techniques used for mobile robot navigation and the current state-of-the-art research where these techniques are applied. Regarding mobile robot navigation and obstacle avoidance, algorithms combining genetic and neural network algorithms and mimicking biological phenomena, such as fuzzy logic, neural networks, and ant colony optimization algorithms, were used. These algorithms can help real-world robots avoid obstacles and navigate targets without collision, even in unstructured environments. These approaches are highly relevant for patient transportation robots, which must dynamically adapt to hospital layouts, crowded hallways, and unpredictable human movement. By transferring such techniques from manufacturing and logistics to healthcare, autonomous hospital robots can achieve higher safety and efficiency levels during patient transfers or deliveries.

3.2. Review Papers on Healthcare Robots

Robotics has become central to improving healthcare quality, safety, and accessibility. Thus, research into robotics in healthcare is ongoing.

Matheson et al. [] provided examples of human–robot collaborations and future trends. Collaborative robots are novel and allow workers and robots to work together with greater safety and flexibility, and they can improve work efficiency. The performance and safety of collaborative robots can be further improved by simplifying the robot’s control system, clarifying the division of labor between the robot and human operator, and maintaining the distance between them. These measures can contribute to the future development of collaborative robots. The overall collaborative robot market is expected to grow from USD 710 million in 2018 to USD 12.3 billion by 2025 at a predicted Compound Annual Growth Rate of 50.31%. These market growth forecasts reflect growing interest in collaborative robotics technology and industry and raise expectations for more innovation and advancements in collaborative robotics in the future. In healthcare, older adults are among the main patient groups. With the growth in the older population, the demand for assistive devices that support health and independence is rising. These assistive devices include navigation and patient transportation technologies. In exploring the advancement and need for robotics in healthcare, focusing on mobility aids for older adults is necessary.

Krishnan et al. [] investigated various mobility aids, such as manual, electric, and autonomous wheelchairs, for older adults. Manual wheelchairs require more effort than electric ones because they require physical force from the user. However, electric wheelchairs are equipped with automatic navigation. Moreover, they are autonomous, using reflective tape and various sensor technologies to detect their surroundings and determine their routes. They can detect the location and direction of the caregiver and automatically follow them. Finally, wheelchairs with intelligent user interactions utilize webcams to detect the gaze and gestures of the user or interpret brainwave signals to control the wheelchair. These wheelchairs can improve the quality of life of caregivers and users.

Patient transfer devices are categorized into dependent and independent lift devices. Dependent lift devices offer various functions to safely turn or lift patients; however, they require direct assistance from a caregiver. In contrast, independent lift devices can lift and transfer a patient to another surface without the caregiver’s assistance. As previously mentioned, mobility aids for older adults use various technologies related to patient transfer, such as navigation and route finding. The technology used in these aids can be leveraged by the following robotics technologies used in hospitals.

The algorithmic advances discussed above are essential; however, technical factors, as well as the physical, mental, and social aspects of the human experience with robots, should be considered when discussing the applicability of robotics. Huang et al. [] provided insights into the precedents of using intelligent physical robots in healthcare. They analyzed papers on different robots, such as mechanoid, animal-like, and humanoid robots, with individuals of different ages and genders in mental health facilities, hospitals, and outpatient clinics. Studies on various healthcare topics, such as client and professional interactions with robots, robots improving work and assisting patients with medication, and robotic interventions to alleviate behavioral and psychological symptoms, have revealed that robots can improve the physical, mental, and social health of healthcare providers, caregivers, and individual users to some extent.

Irshad et al. [] mentioned that robotics technology is revolutionizing healthcare across logistics, surgery, and patient mobility. Future technological advancements will enhance autonomy and human–robot collaboration, enabling more personalized treatment.

The above studies explored technologies for detecting real-time patient movement and assisting patients safely through navigation, object tracking, and optimal pathfinding using various sensors and algorithms, which will be important for following robots in transporting patients. No study is specific to following robots; nonetheless, research has been conducted on collaborative robots, which include the collaboration between medical personnel and robots, and can provide insights into technologies that enable effective human interaction and collaboration.

4. Survey of Human-Following and Path-Tracking Robots: A Cross-Industry Perspective

In this section, we survey the technology and applications of following robots without specifying any industry. Following robots are broadly categorized into human- and path-tracking robots. Research is being conducted on human–robot interactions and human tracking, focusing on technologies that improve cooperation and interaction between robots and humans. In contrast, path tracking focuses on leader–follower robots in specific environments. Leader–follower robotics involves studying the cooperative behavior between robots and developing effective path-tracking algorithms in various environments. Until the early 2000s, red, green, and blue (RGB) cameras were predominantly used in sensor technology, followed by depth cameras. However, monochrome cameras were used previously, and cameras that detect RGB colors were used to enable better object recognition. Cameras at that time had low resolution and low visual intelligence. A depth camera can measure the depth of an object, allowing the perception of its surroundings in three dimensions. Light Detection and Ranging (LiDAR) sensors emit laser beams to measure distances to objects and create three-dimensional maps of the environment.

The Kinect sensor combines a depth sensor with an RGB camera to enhance object and depth recognition. Computer vision technologies use RGB cameras, depth cameras, IR sensors, Kinect sensors, and LiDAR sensors. Sensor fusion integrates data from diverse sources, and deep learning techniques further advance the vision capabilities of robots.

4.1. Human-Following Robots

Human-following robots represent a significant advancement in recent years, aiming to create machines capable of autonomously following and interacting with humans. These robots heavily rely on sophisticated sensor technologies and algorithms. First, we review the sensor technology and algorithms. The efficacy of human-following robots depends on the sensors used and the sophisticated algorithms that process sensor data and make real-time decisions. Finally, we review interactions between humans and robots. Understanding the different types of human–robot interactions is essential for designing robots that can seamlessly integrate into human environments.

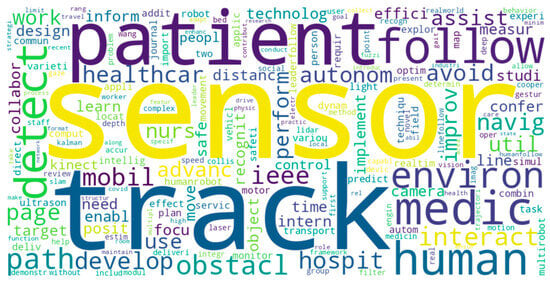

Advanced sensor technologies, such as LiDAR, cameras, ultrasonic sensors, and inertial measurement units, form the basis for human-following robots to perceive and interpret their surrounding environment. Recent advances in deep learning have improved the ability of robots to accurately track and follow humans. We intend to identify the possible human and robotic behaviors and understand the evolving technology. We present a word cloud based on the review of human-following robots. We can briefly state that the research in this area focuses on navigation, obstacle detection, autonomous mobility, medical environments, learning, and optimization, as shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Word cloud from the literature review on human-following robots.

4.1.1. Hardware

Early research on mobile robotics began to achieve safe navigation and movement of humans. In hospital environments, following robots are increasingly designed not only to avoid obstacles but also to collaborate with patients and staff, assisting in tasks such as patient transport, medicine delivery, and escorting individuals within clinical facilities. Advances in sensor technology combined with machine learning algorithms have enabled robots to recognize and predict human movements and intent more accurately. Research has continued to evolve, leading to more sophisticated tracking and recognition techniques, including facial recognition technology and advanced filtering methods. Combining computer vision and robotics has led to new technological advances, including LiDAR and AR, which enable robots to perform more complex tasks in human environments, driving research toward improving robot interaction and deeper integration into human daily lives. Sensor-based LiDAR is effectively used for human tracking because of its precise range, 3D mapping, real-time data delivery, high reliability, obstacle detection, non-contact measurement, versatility in different environments, and ability to recognize human forms. Leigh et al. [] studied indoor and outdoor human detection and tracking and presented a novel method for detecting, tracking, and following using LiDAR at the leg level.

Human detection refers to the ability of a robot to detect and recognize humans in its environment using a laser scanner. A laser scanner is a sensor attached to a robot that uses a laser beam emitted into the environment to measure distances to nearby objects and then collects them as data points. The data points collected are grouped into clusters based on a distance threshold, with each cluster consisting of data points representing different objects, such as human legs. Clustered objects are categorized as human or non-human based on their geometric characteristics. Koide et al. [] proposed a multifunctional human-identification method for mobile robots. Two-dimensional histograms were extracted from random rectangular regions of the human area and used as color features. To measure the height of a person, a hair-color model, a gradient image, and the position of the person obtained through laser range-finder-based tracking were used to detect the location of the sign in the image. They also developed a novel method to estimate gait features from accumulated range data by locating support leg positions using maximum likelihood estimation with mean travel and constant stride-length constraints. These features were combined into joint features and trained using online boosting. The proposed multi-feature identification method was tested in a scenario with frequent occlusions under harsh lighting conditions to demonstrate its validity. Duong and Suh [] proposed a human gait-tracking method using 360° 2D LiDAR. The left and right legs were tracked separately, and to overcome the occlusion between legs when one may be hidden from the sensor, an eighth-order algebraic spline-based smoothing and interpolation method was applied to estimate the center point line and trajectories of the left and right legs. Rudenko et al. [] introduced THÖR, a new dataset containing human motion trajectory and gaze data collected indoors, using accurate ground truth location, head orientation, gaze direction, social grouping, obstacle maps, and target coordinate information. THÖR also contains sensor data collected using 3D LiDAR and includes mobile robots navigating through space. They proposed a set of metrics to analyze the motion trajectory dataset quantitatively, such as the average tracking duration, ground truth noise, trajectory curvature, and velocity variation.

Tracking people in visible-light images has been studied for decades. RGB images and 3D depth sensing have been used for camera-based human-following technology. This was achieved by integrating a Kinect sensor with a visible-light camera. Munaro and Menegatti [] used a depth-based sub-clustering method to detect humans within 3D clusters obtained from Red, Green, Blue, and Depth (RGB-D) sensor data. The sub-clustering algorithm detects the head first, and because it is typically the highest and least likely to be occluded, the algorithm can identify humans within a cluster. The proposed system was compared with other tracking algorithms on two datasets obtained from three static Kinect sensors and a moving stereo pair. The experiments revealed that the system is the most accurate and has the highest speed without using GPUs (Graphics Processing Units).

Jafari et al. [] approached human detection and tracking from the perspective of a moving observer based on RGB-D. They focused on two scenarios: a mobile robot traveling in a crowded urban environment and an AR application using a head-mounted camera system. In these situations, humans near the camera are only partially visible because of the occlusion caused by the image’s boundaries. Their study simplified the object detection task by fully utilizing the depth information from RGB-D sensors. Particularly, the geometric information of the scene was used to limit the search range for distant appearance-based object detection. The proposed system runs on a single CPU core at a video frame rate and achieves a performance of 18 frames per second (fps) even when far-field detection is included. Koide et al. presented a system that used RGB-D cameras to track and re-identify humans based on face recognition []. The system can effectively track humans who have left and re-entered the camera’s field of view by integrating advanced face recognition algorithms and a face classification method based on Bayesian inference. The distributed processing approach using OpenPTrack and OpenFace ensures the real-time performance of the system, and it is built as a robot operating system module to enable easy integration with robots.

More recently, multiple sensors have been combined rather than using a single sensor. Ye et al. [] designed a vision-based adaptive-control system for two-wheeled inverted pendulum robots to track moving human targets by integrating multi-sensor data. A novel algorithm was proposed to combine the OptiTrack camera and Kinect for efficient and robust tracking performance, and leader–follower control, dynamic balance control, and visual tracking were effectively developed to achieve the desired tracking and balance. Extensive studies were conducted to validate the effectiveness of the proposed approach and demonstrate that robust human tracking can be performed by robots indoors. Oswal and Saravanakumar [] proposed the design, assembly, and dynamic simulation of a line-following robot that focused on integrating proximity and vision sensors. The simulation enabled simultaneous collision avoidance and line tracking. Proximity sensors emit ultrasonic waves to adjust the distance from obstacles and prevent robots from colliding if the path is blocked or obstructed. Vision sensors support path detection and allow robots to move forward, guiding them throughout their path while helping them avoid collisions with factory equipment. Combining proximity and vision sensors can help robots to safely escort patients while maintaining dynamic balance and avoiding collisions in complex hospital environments. Latif et al. [] aimed to develop a line-following robot in an environment where learning media devices and instruments are scarce. In their study, a line-following robot based on an ATmega32A microcontroller was tested, and the line was estimated using the properties of light reflected from light-colored objects and absorbed by dark-colored objects. The robot could follow a black line and display the situation on a liquid crystal display (LCD); however, the sensitivity of the line detector varied at a certain speed.

Light images have drawbacks because they are affected by light conditions. In contrast, thermal imaging is unaffected by light conditions; therefore, it can detect and track individuals in darkness, foggy conditions, smoke, and other visually obscured scenarios.

Thermal imaging further enhances patient-following robots, particularly in low-light hospital areas such as night-time wards or emergency rooms. Unlike visible-light cameras, thermal sensors detect humans regardless of lighting conditions and preserve privacy, which is essential in healthcare settings. Thus, the thermal image replaces the light camera to overcome the drawbacks of the latter. Many difficulties arise in converting visible light into thermal images. Portmann et al. [] proposed a novel particle-filter-based framework for tracking humans using aerial thermal images. This novel approach processed thermal image sequences that view a scene from the perspective of unmanned aerial vehicles. It also introduced a pipeline with a reliable background removal method and a particle-filter-guided detector. They revealed that the tracking framework outperformed all implemented detectors with high precision, even when experiencing large and unstable motions. RGB-D cameras extract data that combine red, green, and blue information with depth information and can be used to obtain color and depth images from sensors such as Kinect.

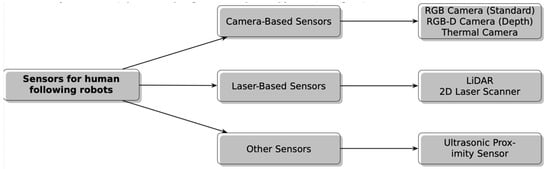

We summarize the sensor technology used in following robots in Figure 3. LiDAR-based sensors precisely measure distances to the surrounding environment using lasers. LiDAR is effectively used to detect and track objects at the human leg level, leveraging its capabilities for precise 3D mapping and real-time data provision. Camera-based sensors include RGB cameras, depth cameras, and thermal imaging cameras. RGB cameras track people using visible light images, while RGB-D cameras add depth information to color data, with Kinect being a representative example. Thermal imaging cameras detect heat, enabling human detection regardless of lighting conditions. They do not identify faces, offering advantages in privacy protection.

Figure 3.

Human-following robot sensor classification.

4.1.2. Software: Robot Mobility, Mapping, and Path Planning

The following studies describe the advancements in human-following robots and related technologies from multiple algorithmic perspectives. The most popular algorithm is the Kalman Filter, which estimates the state of a linear dynamic system from time-series data, including incomplete or noisy data. The Kalman filter generates real-time predictions and adjustments for navigation systems and robotics. Gupta et al. [] described the development and implementation of a novel visual controller for human-following robots. An online K-dimensional tree-based classifier with a Kalman filter and a dynamic object model that evolved over time while maintaining long-term safety was used to distinguish partial from full pose change cases. The spread of the projected points was used to detect pose changes due to out-of-plane rotation, which is a novel contribution of the study.

In the study by Ren et al. [], a user gave a hand gesture command as a start signal, and a human-following robot locked onto the user and started tracking. The system consists of a primary and secondary tracker that uses the skeleton-tracking algorithm provided by the Kinect SDK and Camshift, respectively. If the primary tracker fails, the secondary tracker uses Camshift to correct the results such that the robot attains the proper position. Once the target is located, an extended Kalman filter predicts the position at the next moment. Chi et al. [] proposed a gait recognition method for service robots performing human-following tasks. A gait sequence segmentation method was designed to extract consecutive gait cycles from an arbitrary gait sequence. The proposed method used a new hybrid gait feature to capture static, dynamic, and trajectory features for each segmented key point and secondary gait cycle. Saadatmand et al. [] revealed the limitations of traditional trial-and-error-based controller parameter tuning methods and proposed a Multiple-Input Multiple-Output Simulated Annealing (SA)-based Q-learning controller for the optimal control of a line-following robot. In their study, they presented a mathematical model of a robot and designed a simulator based on this model. Existing methods based on exploiting basic Q-learning are limited by exploring suboptimal behaviors after learning is completed, which can degrade controller performance. The simulated annealing-based Q-learning method addresses this drawback by reducing the exploration rate as learning increases. Nguyen et al. [] proposed a robust adaptive behavior strategy (RABS) to help mobile robots smoothly and safely follow a target human in an unknown environment. RABS is based on a fuzzy inference mechanism that analyzes the passability of a robot’s surroundings to determine the optimal direction and safe tracking distance and smoothly adjusts the speed of the robot. They observed that RABS can aid smooth and safe human following, even with large and heavy autonomous mobile robots.

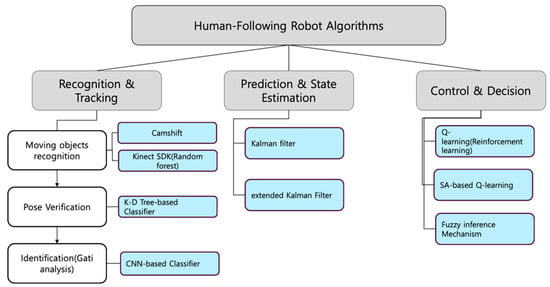

From the above review, we created a diagram of the human-following robot algorithms, focusing on their functions. The recognition and tracking algorithm firstly recognizes moving objects, then checks whether a moving object is human or not through pose verification, and finally identifies who is moving. The second step is prediction and state estimation. In this phase, the algorithm predicts human movement after calibrating noises using the Kalman filter algorithm. The last phase is control and decision. In this phase, the algorithm performs a higher-level process that determines what actions a robot will take based on the predicted information. Figure 4 represents the types of human-following robot algorithms and their related detailed tasks and sensors.

Figure 4.

Human-following robot algorithm families.

Camshift is robust to changes in the target’s scale and rotation, but it is sensitive to light. The Kalman filter is effective in noisy data, but it can handle linear data only. The extended Kalman filter overcomes these drawbacks. However, Kalman filter families require an accurate mathematical model of system dynamics, which is difficult for unpredictable human behaviors. The K-D Tree-based classifier has an advantage for dealing with multi-dimensional data, but its performance degrades significantly as the dimensions increase. The CNN-based classifier, the deep learning algorithm as a whole, exhibits good performance but requires numerous data for training. The Q-learning algorithm is a model-free algorithm, but it is slow because of the trial-and-error approach. The fuzzy algorithm is good in unknown environments, but the fuzzy rules should be manually defined, and performance is highly dependent on those rules.

4.1.3. Software: Human–Robot Interaction

The interaction between robots and humans is a critical issue in terms of safety and efficiency. Robots and humans must predict each other’s movements and avoid collisions to prevent hazards. Furthermore, HRI is essential for efficiently assisting human tasks and enhancing productivity. This section reviews cutting-edge research and developments that enhance how robots perceive and interact with humans using sophisticated gesture and behavior recognition technologies. Early research revealed that mobile robots can safely navigate static and dynamic obstacles, and integrating advanced sensing technologies, such as RGB-D sensors, has improved their ability to move and operate safely around humans. These robots now recognize and interact with humans safely and comfortably, no longer treating them simply as obstacles to be avoided, paving the way for more intuitive and seamless human–robot collaborations. Interactive robots detect, track, and follow people, improving their ability to socially interact and form groups. The following research focuses on improving human–robot interactions, demonstrating that robotics is evolving to play an important role in an increasingly socialized, human-centric environment. Research on human–robot interactions is divided into individual human–robot and group interactions. Technically, human interactions are divided into behavioral recognition, gesture recognition, and gaze tracking.

- Gesture and behavior recognition.

Dondrup et al. [] addressed the spatial interaction between robots and humans—the human–robot spatial interaction (HRSI). Their study focused on interaction and social cues, such as posture and orientation recognition, when a robot and a human move through space together, avoid each other, and when a human overtakes a robot. Their study aimed to enable mobile robots to understand and act in HRSI situations. Specifically, it focused on two body-part detectors that identify the human upper torso and legs. The study utilized Qualitative Trajectory Calculus (QTC) state chains and the Hidden Markov Model to classify and explain HRSI situations. A small-scale experiment using an autonomous human-sized mobile robot in an office environment demonstrated the capabilities of the proposed research framework.

Natural and intuitive interactions between humans and robotics systems are key to robot development. Canal et al. [] presented a human–robot interaction (HRI) system that recognizes gestures commonly used in nonverbal communication. They proposed a gesture recognition method based on the KinectTM v2 sensor that considers dynamic and static gestures, such as hand waving or nodding, recognized using a dynamic time-warping approach based on gesture-specific features. These studies focused on developing and applying various tools to improve HRI quality. Processing techniques, such as Kalman filters, and sensor technologies, such as Kinect, have been pivotal to recognizing and predicting human movements, ensuring smoother, safer, and more socially acceptable patient transport in hospital environments.

- Gaze recognition.

Gaze recognition is more challenging than gesture and behavior recognition. Gaze tracking requires high precision to determine the exact focus point because the eyes perform small and rapid movements that must be tracked accurately. In the context of hospital-based patient transportation, gaze recognition enables robots to anticipate patient intentions, respond appropriately, and maintain safe, efficient interactions in dynamic clinical environments. In following robots, gesture and behavior recognition has evolved into gaze recognition. May et al. [] proposed two approaches for communicating the navigational intent of mobile robots to humans in shared environments. The first approach used gaze to express the direction of navigational intent, and the second used a technical approach inspired by automobile turn signals. These approaches were applied as head orientation and visual light indicators. Huang et al. [] presented a predictive control method that enabled robots to actively perform tasks based on the expected behavior of a human partner. They developed a human interaction robot that predicted the user’s intentions based on the observed gaze patterns by monitoring the user’s gaze through SMI eye-tracking glasses V.11 and mapping gaze fixations in the camera to locations in the workspace. They also performed tasks based on these predictions.

The eye-tracking system developed by Palinko et al. [] enabled more efficient human–robot collaboration than the head-tracking approach, according to quantitative measurements and subjective evaluations of human participants. The eye-tracking technology was used in human–robot interactions to enable robots to detect the human gaze. The robot was more efficient and intelligent when using eye-tracking technology, demonstrating its importance in robot–human interactions. For patient transportation, this means robots can detect where patients are looking, interpret subtle cues about intentions, and respond proactively. They also implemented an eye-tracking system using Pupil Labs’ Pupil Core, demonstrating that it is relatively easy to implement eye-tracking technology.

4.2. Crowd Robots

The crowd robot is a type of robot designed to operate within and interact with crowds of robots. These robots are equipped with advanced sensors and algorithms to navigate densely populated environments safely and effectively. We reviewed the robot–group interaction technology. This section begins by outlining the historical context of mobile robots, which initially focused on safe navigation around humans. This focus has evolved into more complex interactions, such as collaboration and advanced tracking capabilities.

4.2.1. Hardware

Navigation hardware plays a vital role in ensuring safe and efficient movement for patient-following robots in hospital environments. Robots designed for patient transport must move reliably through dynamic, crowded spaces, such as hallways, wards, and elevators, requiring robust multi-robot coordination and stable control systems. Benzerrouk et al. [] studied the navigation of multi-robot systems and focused on strategies allowing robots to navigate using virtual structures to stabilize and maintain their shape. They assigned each robot a virtual goal and cooperatively controlled them to track that goal. When applied to hospital logistics, such cooperative navigation enables multiple robots to coordinate patient transport tasks simultaneously—such as guiding beds, wheelchairs, or supply carts—without collisions or disruptions. The control structure was validated using a Lyapunov-based stability analysis, and its effectiveness was demonstrated through simulations and experiments. Their work presents an innovative approach to ensure the dynamic interaction and stability of multi-robot systems and contributes to robot control.

Chevallereau et al. [] investigated the use of electrical senses to maneuver underwater vehicles cooperatively. They developed a leader–follower system that uses the electric fields generated by robots to coordinate their positions and move as a group. Based on interactions through an electric field, the robots can coordinate their movements without explicit positional information. Their approach was validated through simulations and experiments, contributing to improving the autonomy and cooperation capabilities of underwater robotic systems. Min et al. [] overcame the limitations of existing studies that focused on robot communication in specific real-world environments, where applying these systems was challenging because of various constraints. They proposed a method to improve communication in a leader–follower system using directional antennas and estimated the position of the leader robot using a weighted average centroid algorithm. This method enables efficient communication between robots, allowing them to operate independently. Consequently, robots cooperate better and work more efficiently. Patil et al. [] conducted a study to improve communication and navigation in multi-robotics. The study had two main objectives. The first was to build a communication network for crowd navigation through a leader–follower method. Here, the leader robot coordinated with the follower robots to lead the path. The second goal was to implement a goal-tracking system that allowed follower robots to track the location specified by the leader robot. The follower robots received signals from the leader for synchronized movements. In a goal-tracking system, robots were instructed to move to a predetermined location. Their study carefully addresses the communication and navigation of multi-robot systems and lays the groundwork for complex applications of multi-robotics.

Collectively, these studies highlight the potential of advanced navigation and communication hardware for patient-following robots. The integration of leader–follower control, stable formation algorithms, and reliable inter-robot communication is essential to achieving safe, efficient, and human-aware navigation in hospital environments.

4.2.2. Software: Robot Group Interactions

Chen et al. [] broadened the scope of human–robot interactions to explore crowd–robot interactions. They combined a self-attention mechanism with a reinforcement learning framework to simultaneously model HRI and human–human interactions. They extracted pairwise interaction features between robots and humans and captured human–human interactions through local maps. Self-attention was used to determine the relative importance of neighboring humans to the future state, which can significantly influence a robot’s decision. Interactions were modeled with a human–robot and human–human interactions module, a pooling module that aggregates interaction features into embedding vectors, and a planning module that estimates the value of the crowd for social navigation. In hospital corridors, such capabilities allow patient-following robots to navigate safely around clusters of patients or staff, anticipate crowd movements, and minimize disruptions to medical workflows. Simulation experiments demonstrated that the proposed methodology outperformed existing methods in predicting crowd dynamics, and the effectiveness of the robot in real-world environments was also demonstrated.

Pathi et al. [] proposed an autonomous group interaction for robots (AGIR) framework that empowers robots to sense groups while following F-formation principles. The F-formation describes how humans position themselves in groups, look at each other, and interact socially. The proposed AGIR framework used human detection to process the subjective RGB data captured by the built-in camera of the robot. This approach extracted the 2D poses of humans in the scene, which were used to determine their number and orientation. Finally, the laser sensor of the robot was used to measure the spatial information of the humans. Therefore, localizing humans in a scene and detecting social groups are crucial.

There are several examples of interactive robots used in manufacturing systems. These studies address the technology and efficiency of human–robot interaction in robot manufacturing systems. Modern manufacturing systems require increased levels of automation for fast and low-cost production and a high degree of flexibility and adaptability to dynamic production requirements. However, the biggest challenge is ensuring human safety near robots. Nikolakis et al. [] discussed a cyber–physical system that enables and controls safe human–robot collaboration. The workspace is monitored via optical sensors, focusing on the cyber–physical system based on the real-time assessment of safe distances and closed-loop control to execute collision-prevention measures. In addition, wearable AR technologies must be technologically mature in terms of design, safety, and software. Hietanen et al. [] defined industry-standard safety requirements requiring real-time monitoring and a minimum protective distance between the robot and operator. They proposed a depth-sensor-based workspace-monitoring model and an interactive AR user interface (UI). The AR UI was implemented on two pieces of hardware—a projector mirror setup and a wearable AR device, HoloLens. Wang et al. [] used deep learning as a data-driven technique for continuous human behavior analysis and to predict future human–robot interaction requirements to improve robot planning and control. They used the deep convolutional neural network adopted by AlexNet and demonstrated a recognition accuracy of over 96% in a case study of automobile engine assembly.

These studies have led to advances in robotics and computer vision that exceed the traditional tracking and recognition techniques of the Kalman filter and Kinect sensors. Face representation techniques and advanced filtering methodologies, such as the extended Kalman filter, were introduced in this period. Previous studies indicated this was pivotal in developing computer vision, robotics, and cyber–physical systems. Technological advances, such as LiDAR, AR, and reinforcement learning, have made novel contributions to research and applications.

4.2.3. Software: Multi-Robot Interaction

Early pathfinding algorithm research focused on cooperative control methodologies as a key principle for enabling the operation of multi-robot systems in complex environments. Eventually, the research focus shifted to practical applications and automation. The application of deep learning and advanced algorithms is becoming a critical research direction, and path-tracking research is being extended to various domains, especially by introducing reinforcement learning. Recent studies have actively addressed these trends. Related studies can be classified into hardware and control algorithm studies. In the evolution of robotics, improving leader–follower dynamics was initially focused on developing responses to dynamic environments and complex obstacles, emphasizing formation and tracking control mechanisms. However, this focus has shifted to practical applications, particularly in automation, collaboration, and improvement in obstacle avoidance navigation techniques, which have begun to manifest themselves in practical advances in specific application areas, such as agriculture.

4.2.4. Software: Leader Robot Trajectory Tracking

The studies in this section focused on establishing basic communication and navigation structures that provide the basis for implementing coordinated movement and target tracking among robots. Further research will extend these basic structures to develop advanced control mechanisms to enhance the navigational capabilities of robotic systems. Low [] introduced an innovative leader–follower formation tracking control design for nonholonomic tracking mobile robots that enables the effective traversal of unpredictable terrain and stable formation maintenance. It uses curve-based longitudinal and lateral relative separations, generates a real-time curve-based formation reference based on the leader’s motion information, and integrates a nested-loop nonlinear trajectory tracking control structure to enable the robot to achieve stable curve-based formation maneuvers without requiring detailed models. The study was conducted in various environments, and a sports utility vehicle was used as the leader to verify the effectiveness of the control design.

The optimization-based methodology presented by Luo et al. [] focused on relative position tracking and trajectory tracking control within a multi-robot system. By extending the sensor-based leader–follower coordination mechanism, their paper proposed an effective method for robots in a multi-robot system to track dynamically changing trajectories in complex environments. Their study presented a novel approach to complement obstacle avoidance strategies and improve real-time performance in more complex disturbance environments. Thus, state estimation algorithms based on nonlinear moving horizon estimation and nonlinear model predictive control are applied to improve the accuracy and develop efficient algorithms to meet real-time requirements.

4.2.5. Software: Collision Avoidance

Edelkamp and Yu [] proposed a framework for mobile robots to inspect an entire workspace while following collision-free paths. This framework used a supervised path based on automatically generated waypoints to inspect the workspace efficiently. Skeletonization and centroid transformation were used to compute the waypoints, and the collision-free pathfinding mechanism was applied to the specific scenario in the previous section and validated by monitoring the simulation in unity. Consequently, the proposed framework provides a robust and efficient method for mobile robots to inspect an entire workspace along a collision-free closed path. Le and Plaku [] explored a cooperative mechanism for multiple robots to efficiently reach their destination in a dynamic environment. The follower function developed in their study was designed to guide the robots along a path, optimizing their ability to reach the goal point by considering the current state of the robot, planned path, and movements of other robots in real time. This function managed obstacle and collision avoidance between paths, ensuring that robots arrive safely and efficiently at their destination. The experiment revealed that this method enables faster and more economical path selection than traditional multi-robot motion planning techniques. Gharajeh and Hossein [] proposed a novel technique for the speed control of nonholonomic mobile robots that combined fuzzy logic and supervised learning. Two ultrasonic sensors were used to measure the distance to the leader robot; a fuzzy controller determined the final distance, and a supervised learning algorithm adjusted the speed of the robot based on this distance. The simulation revealed that the robot maintained a constant distance from the leader robot and tracked it accordingly. Caro and Yousaf [] worked with a team of autonomous robots surveying a large area. The study aimed to create a spatial map of the desired physical values modeled using a Gaussian process. It also considered time constraints and collision avoidance while modeling with a leader–follower architecture. The leader identified areas for the team to investigate and assigned sampling locations to followers using Bayesian optimization and Monte Carlo simulation. In contrast, the followers independently found a path that maximizes information gain. The authors used an adaptive replanning criterion that continually redirects sampling to areas where information is most needed, and the algorithm performed well in map estimation.

Building on these basic control mechanisms and advances in navigation techniques, obstacle avoidance, and optimal paths in real-world environments, we explored the latest research on the design and implementation of advanced algorithms that can be applied for exploration. Alshammrei et al. [] focused on designing and implementing algorithms for optimal path planning and obstacle avoidance in mobile robots (MRs). They modeled an MR’s obstacle-free environment as a directed graph and used Dijkstra’s algorithm to generate the shortest path from the start to the goal point to achieve their study aims. The MR moves along the previously obtained path and tests for obstacles between the current and next node using an ultrasonic sensor. When an obstacle is detected, the MR excludes that node and runs Dijkstra’s algorithm again on the modified directed graph. This process is repeated until the target point is reached. Their study revealed that MRs can avoid obstacles and determine the optimal path, demonstrating that STEAM-based MRs are effective and cost-efficient for implementing the designed algorithm. Mondal et al. [] proposed a geometrically constrained path-following controller with built-in intelligent collision avoidance, which was designed based on a dual hybrid control law. This hybrid control law combines feedback linearization and fuzzy logic controllers, with the former helping a mobile robot maintain the desired path and the latter helping it avoid critical obstacles around the path. The analysis revealed that the control law converges to the desired path when the robot is at a safe distance from the obstacle. In addition, when the robot detects an obstacle within its range, the obstacle avoidance control laws act locally to steer the robot off the desired path and avoid collisions while maintaining stability on the path.

These advances in collision avoidance algorithms provide a foundation for hospital-focused patient-following robots. By integrating real-time path planning, adaptive obstacle detection, and cooperative multi-robot strategies, robots can safely transport patients, avoiding static obstacles (like walls, beds, and carts), navigate crowded environments, and support hospital staff efficiently.

4.2.6. Software: Robot Swarm Collaboration

Merheb et al. [] developed and applied an algorithm that allowed a swarm of robots to safely navigate an environment with complex obstacles. A panel method was used to accurately compute the flow between the shapes of the robots and obstacles, and the resulting flow lines provided a path for the robots to travel to the target location without collisions. Their algorithm used artificial latent functions to maintain robot cohesion and focused on shape preservation while moving. The experiments demonstrated that the robot swarm could efficiently reach the target, providing a foundation for the practical applicability of the proposed algorithms.

Mehrez et al. [] presented an optimization-based framework for solving relative positioning and tracking control problems in multi-robot systems. This framework is intended for accurate state estimation and tracking control in multi-robot systems with diverse applications, such as patrol missions, navigation tasks, and neighborhood surveillance. A nonlinear MHE (Moving Horizon Estimation) algorithm uses various sensor data to accurately estimate the relative positions of robots in multi-robot systems. The NMPC algorithm tracks the relative positions of robots and minimizes estimation error, enabling precise positioning to address the tracking control problem. A real-time iteration algorithm was used, which runs the NMPC (Nonlinear Model Predictive Control) algorithm in real-time while satisfying the real-time control requirements. The above studies paved the way for emphasizing the importance of collaboration and interaction in robotics. Subsequent studies have developed the idea of effective information sharing and collaboration between robots to further enhance group cohesion and task efficiency.

Wang et al. [] presented an innovative approach to address the Simultaneous Localization and Mapping (SLAM) problem in multi-robot systems, focusing on master–follower dynamics. When a robot or device first enters an unfamiliar indoor space without GPS, this technology enables it to explore its surroundings, build a map, and simultaneously determine its own current position on that map. Position estimation and map building are inherently intertwined and challenging problems, but SLAM solves both simultaneously using sensor data and algorithms. They proposed a system in which a master robot led the SLAM process, while multiple follower robots collaborated to build a comprehensive map by gathering detailed environmental data. Each robot tracked its position and surroundings simultaneously, thereby contributing to a jointly constructed map. Researchers have also developed an efficient information exchange protocol to minimize data redundancy during exploration. This enhances the coverage of the explored area and mapping accuracy. Following their study, researchers embraced deep learning models to advance robot navigation, surveillance path planning, and multi-robot cooperation. Niroui et al. [] proposed the first application of deep learning techniques in urban search and rescue applications, in which robots navigated unknown and complex environments. They combined traditional frontier-based navigation methods with reinforcement learning to enable robots to search and track autonomously in unknown and complex environments. Experiments using mobile robots in complex environments revealed that the proposed navigation method effectively determined the appropriate frontier location and demonstrated high performance in various environments. In addition, a comparative study with other frontier exploration approaches revealed that the learning-based frontier exploration technique could explore a larger portion of the environment faster and identify more victims at the beginning of the time-critical exploration task.

Moshayedi et al. [] indicated that increasing the path-tracking efficiency of a robot by tracking the optimal sensor is challenging. Several solutions, such as SLAM and dual cameras, have been proposed to solve this problem; however, they are limited by the increasing cost and complexity of the algorithm. Therefore, the researchers combined vision sensors and proposed a simple fusion algorithm that combines infrared sensors to analyze the paths of various bends. It can guide a robot accordingly and uses minimal sensors. Gul et al. [] proposed a novel intelligent multi-objective framework for robot path planning, which aims to generate optimal paths by blending two metaheuristic techniques: the Grey Wolf Algorithm (GWO) and Particle Swarm Optimization. They improved the exploration operator of the GWO to accelerate the exploration and introduced a new exploration strategy for collision detection and avoidance. The algorithm was effective in terms of path smoothness and safety in diverse environments and was validated via comparison with existing algorithms.

These studies are revolutionizing the pathfinding technology in robotics and expanding the possibilities of autonomous robots for industrial and real-world applications. Researchers have made important contributions in the modern world, where robot autonomy, efficiency, and human interaction are crucial. We summarized the research on crowd robots in terms of research purpose, domain, and algorithm in Table 1.

Table 1.

Recent works on following robots.

4.3. Applications

Masuzawa et al. [] discussed the application of mobile robotics technology for harvesting assistance in greenhouse horticulture to resolve labor shortages, which is a major agricultural challenge. The study aimed to develop a harvesting assistance mobile robot that can operate in a greenhouse growing flowers. The required technologies are human following and mapping. In the experiments, a prototype mobile robot with human-following and 3D mapping capabilities was developed, and preliminary experiments were conducted in a greenhouse to verify the practicality of the system. Zhang et al. [] developed a leader–follower system in which two robot tractors worked cooperatively in an agricultural field. Each robot tractor could perform tasks independently and collaborate via a specific spatial arrangement as required. The main communication structure was divided into a navigator, which controls the robot, and a server/client, which is responsible for the cooperation and coordination of the robot. When turning on the headland, both robots do not maintain a spatial arrangement but can cooperate to switch to the next path. Each robot tractor was simplified into a rectangular safety zone to avoid collisions. Real-world experiments demonstrated that two robot tractors can safely cooperate to complete tasks compared to a traditional single robot, with a 95.1% improvement in system efficiency. Precision agriculture requires the collection of various data from farms to apply appropriate management methods for crop variations. Bengochea-Guevara et al. [] used autonomous robots to collect precise agricultural data. Autonomous mobile robots aim to increase farm management efficiency by automatically collecting data from farms and identifying and analyzing crop health, location, and growth patterns. These robots integrate cameras and GPS to detect crop changes in real-time and effectively plan routes to explore an entire unmanned farm. However, the robot suffers from vibration and difficulty in controlling its motion owing to irregular terrain and rough surfaces in fields, requiring future improvements in robot design or adaptation to other vehicle types.

In automated highway systems, the automatic cruise control of multiple connected vehicle formations has attracted the attention of control experts because of its ability to reduce traffic congestion and improve traffic flow and safety on highways. Hu et al. [] proposed a dual-layer distributed control scheme to maintain the stability of connected vehicles, assuming a constant lead vehicle speed. First, a feedback linearization tool was used to transform nonlinear vehicle dynamics into a linear heterogeneous state-space model, and a distributed adaptive control protocol was designed to maintain the longitudinal velocity of the entire population while maintaining the same clearance distance between successive vehicles. The proposed method uses only the state information of neighboring vehicles, and the leader does not need to communicate directly with all followers. Simulation results and hardware experiments with real robots verify the effectiveness of the proposed swarm control scheme.

5. Healthcare

In the previous section, we examined various research areas related to human following and path tracking. These studies can also be applied to developing autonomous mobile beds for patient transportation in healthcare and robots to assist medical personnel. Therefore, this section builds on previous research and introduces research on robots in healthcare. Robot 6.1 (autonomous mobile robot) prioritizes destination-based navigation. Using hospital maps (generated by SLAM) or floor lines (line tracing), this robot independently plans and navigates from point A to point B, such as from a pharmacy to a room (e.g., room 501). The core technology involves mapping the environment, calculating the most efficient route, and navigating around obstacles. Robot 6.2 (human-following robot) prioritizes human-centered exploration. The purpose of this robot is not a fixed location, but rather a specific individual, such as a nurse. The robot accompanies and assists this person. The core technology is not about creating an environmental map but rather about accurately tracking a specific individual, such as a skeleton, and keeping them in sight even in complex environments. The two robots have fundamentally different questions: where to go (6.1: a fixed location) and what to follow (6.2: a moving person). The sensors and algorithms required to implement this feature differ between SLAM-based LiDAR and tracking-based Kinect/LRF, which is why they are categorized into separate sections.

5.1. Hardware

We reviewed the hardware used in robots following the “Sense–Think–Act” loop, a classic and powerful model of embedded systems. The sense stage covers the input of robots. The SENSE stage is responsible for detecting the environment or objects using hardware that corresponds to the robot’s input. Meanwhile, the THINK stage handles data processing and decision-making, which is akin to the robot’s neural system. Lastly, in the ACT stage, the system’s decisions have a physical impact on the world.

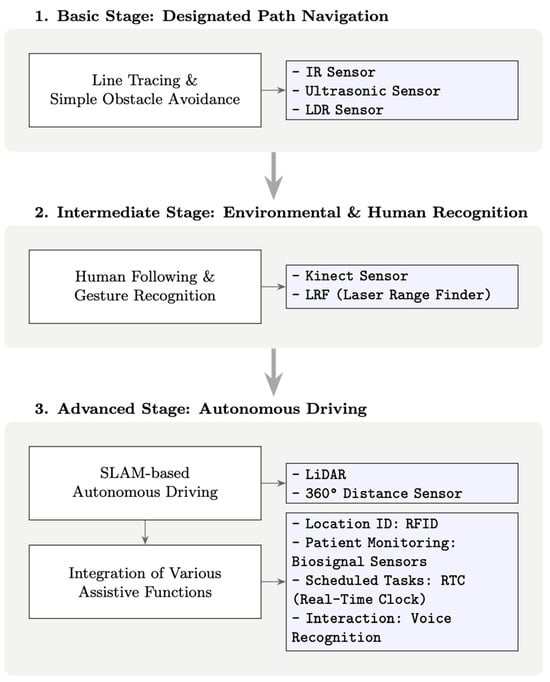

5.1.1. SENSE: Perception Sensors

Prior to applying the following robots in real-world hospital environments, research on various sensors and algorithmic techniques for line detection and obstacle recognition was actively conducted, considering the complex and challenging environments within hospitals. Such research is essential to ensure that following robots can operate safely and efficiently in hospitals. Therefore, we investigated various proposed sensorization methods to identify robots that can be used in healthcare environments.

- LiDAR.

LIDAR is a key sensor that generates high-resolution 2D or 3D maps of the environment and detects obstacles in real time. The device operates on the principle of emitting a laser beam and measuring the time-of-flight of reflected pulses to calculate distance with high precision, a crucial component of simultaneous localization and mapping (SLAM) algorithms. Commercial robots like the Aethon TUG T3 are equipped with a LiDAR system mounted on the side to enhance AI-driven navigation in complex hospital corridors. The key benefits include accuracy, reliability across various lighting conditions, and the ability to create detailed geometric maps of large areas, such as hospital corridors. While excelling at detecting geometric structures, standard LiDAR struggles with semantic understanding, which involves identifying the nature of objects. Additionally, the performance may be compromised by the transparent glass or high-reflectivity surfaces commonly found inside modern hospitals. While less of a concern indoors than outdoors, performance may still be compromised by environmental factors.

Jain et al. [] designed a line-following robot to deliver medicines to patients using light-dependent resistor (LDR), IR, and proximity sensors. The LDR sensor helps the robot remain on the designated path because its resistance changes with light intensity, whereas the IR proximity sensor detects obstacles in the path and raises an alarm to avoid collisions. It is also equipped with a switch near the patient that connects to the robot when the patient presses the switch, allowing the robot to follow the line to reach the patient and deliver medicine. However, the proposed robot was not simulated; thus, its feasibility was not confirmed.

- Vision (Camera/3D Camera).

The vision system offers rich semantic information that LiDAR cannot provide. Standard RGB cameras are often paired with deep learning models to perform tasks such as reading license plates and ward numbers, identifying patients or medical staff, and recognizing gestures. With the addition of depth information, 3D cameras, like stereo or depth-sensing cameras (such as Kinect), enable more robust object detection and tracking in 3D space. Machine vision systems play a crucial role in identifying patients by scanning barcodes on wristbands or charts. The camera offers cost-effective, high-density, high-resolution data with rich colors and textures that are essential for classification and identification. The camera’s performance is highly sensitive to changes in lighting conditions, particularly when dealing with glare and low light. While thermal cameras can overcome this issue, they introduce additional complexity. Additionally, processing high-resolution video streams for real-time object detection can be computationally expensive.

The Kinect sensor integrates an optical camera and depth sensor, making it useful for environmental awareness and object detection, enabling early following. It was heavily used during the implementation of robots. Mao and Zhu [] proposed a Kinect sensor-based healthcare service robot. The proposed robot recognizes human gestures and performs tasks by moving forward, turning left or right, and switching to chair and bed modes based on these gestures. This can be efficient because the robot does not continuously follow the target while traveling along its path; however, this research was not conducted outdoors. Yan et al. [] proposed a human-following rehabilitation robot (HFRR) to support the rehabilitation of older adults and individuals with disabilities. Therefore, Jetson TX2, Kinect, and LRF sensors were used in the robot implementation. The Jetson TX2 controls the position of the robot through image processing, the Kinect sensor helps the robot recognize and track its surroundings and targets, and the LRF sensor is used for obstacle detection. In the simulation, the robot could be stably controlled in real-time with a short execution time by specifying a path. Compared to previous studies, using various sensors allowed the robot to autonomously follow the target without attaching sensors to the target. However, the simulation was conducted only on a preset path, and further research on non-preset paths is required.

- Ultrasonic and infrared sensors.

These sensors are primarily used for short-range proximity detection and collision avoidance. Ultrasonic sensors emit sound waves and measure the resulting echoes, while IR sensors detect the infrared radiation that bounces back. These are often mounted around the lower chassis of a robot and are typically equipped with a LiDAR system. They detect low obstacles that the camera might miss and are affordable and highly reliable, offering a safety net for close-range interactions and effectively serving as a last line of defense against potential collisions. Compared to cameras, they have limited range and resolution. Ultrasonic sensors can be affected by soft sound-absorbing materials, while IR sensors are sensitive to ambient lighting conditions.

In addition to Kinect and laser sensors, IR sensors have been used to extend line tracking and other technologies. IR sensors can be used for line tracking and obstacle avoidance because they are insensitive to environmental lighting changes and can detect distances to an object or surface more accurately. Abideen et al. [] proposed a high-performance design of a line-following robot for use in hospitals and medical institutions using an IR sensor, a proportional–integral–derivative (PID) control algorithm, and a mathematical model of inverse kinematics and motor dynamics. First, the PID controller receives the color-based analog output of the IR sensor that detects the line and passes the signal to the motor. In the process, mathematical techniques are applied to optimize the robot’s path and plan and control its movements so that it can efficiently and reliably follow the line and avoid obstacles, even on paths and surfaces such as inclined surfaces. Chaudhari et al. [] proposed a line-following robot that used IR sensors to transport materials in medical institutions. The IR sensor detects the line, outputs color-based information, and sends it to an Arduino controller. The transmitted information is interpreted and used by the motor-drive module to control the motors and determine the movement of the robot. The implemented robot can assist hospital staff in emergencies and serve as a delivery robot when doctors require medical devices in the operating room. However, when used in hospitals in real time, handling heavy items is challenging because they require a high-power supply, leading to decreased efficiency due to battery consumption. In addition, errors may occur; therefore, further research is required to apply it to a real environment. IR sensors are widely used with other sensors to form multi-sensor systems. Multi-sensor systems improve environmental awareness and control systems, enabling a safer and more efficient automation system. Chien et al. [] proposed an autonomous service robot that navigates a path while avoiding obstacles in complex indoor environments, such as hospital wards or nursing homes. Thus, an Adaptive Neuro-Fuzzy Inference System based on inputs from a 3D depth camera with an IR and a sonar sensor was used. The robot could recognize faces and sex using the camera, with an accuracy of approximately 92.8%, to identify each target. In addition, the ability of the robot to avoid obstacles in static and dynamic environments was verified. The robot could deliver medication to patients and help visitors locate patients. However, further experiments in more complex environments with different hardware configurations are required. Ahamed et al. [] proposed a line-following robot framework that worked with an IR sensor and an Arduino microphone microcontroller to assist patients and older adults in taking their medication. The IR sensor detected the path of the robot, and the radio frequency receiver received digital signals from the microcontroller to control the forward and backward movements based on the patient’s medication time. In addition to detecting the path, the IR sensor and the ultrasonic sensor detected a glass and its volume of drinking water and activated the microcontroller pump to fill the water when it was low. The proposed system was considerably more cost-effective than medical care provided by human nurses. Kavirayani et al. [] proposed a robot that combined an IR sensor with other sensors to support drug delivery to patients with COVID-19. To enable the robot to travel the shortest path without colliding with obstacles, a microcontroller-based IR sensor was used to measure the distance, a white-line sensor was used to track lines on the floor, and an analog proximity sensor was used to detect nearby water. The IR sensor displays whether the medication has been delivered when the robot approaches a patient with COVID-19 by combining these technologies. Once the robot delivers the medication, it is commanded to exit through the nearest gate. Such research has reduced patient and healthcare worker contact, minimized infection, and supported efficient work. However, further research is needed to determine the result of ward layout changes or another robot entering the path of the delivering robot. IR sensors are used with other sensors, most commonly with ultrasonic sensors. Pazil et al. [] developed an autonomous assistive robot using IR and ultrasonic sensors to deliver medicine to patients. The robotic drive was implemented using a microcontroller. The IR sensors were used to design the robot to autonomously detect and follow lines drawn on the floor and stop when encountering an obstacle, whereas the ultrasonic sensors were used to detect obstacles. After the robot delivers the medication, a confirmation message is sent to the medical staff to inform them of the task completion. However, no performance evaluation of the robot other than its design and implementation exists; therefore, conducting simulation experiments in various situations, such as real-life situations, is necessary.