1. Introduction

Car-like Mobile Robots (CLMRs), a technology that has significantly enhanced efficiency in industry sectors such as home services, warehousing logistics, and intelligent transportation, among many others, are increasingly supported by digital models throughout their entire lifecycle—from initial design through to operational deployment [

1,

2,

3].

Owing to their high-fidelity modeling and bidirectional, real-time connectivity, Digital Twins (DTs) offer an accurate and dynamic representation of system behavior, enabling comprehensive insight into the operational state of physical entities and can enhance the adaptability and autonomy of robotic platforms [

4,

5,

6,

7,

8].

In the domain of four-wheeled CLMRs, DT technology refers to an integrated framework that enables real-time, bi-directional synchronization between a physical robotic platform and its high-fidelity virtual counterpart [

3,

4,

5,

9]. According to recent work in this field, the DT architecture typically consists of four key elements: the physical entity, the digital entity, the interactive middleware layer, and the twin data and application services. The physical entity comprises components such as wheels, encoders, IMU, UWB modules, and embedded processors (e.g., STM32, Jetson NX) operating in real-world environments. Its digital twin is constructed using simulation platforms like Webots [

4,

5] or Unity3D [

3], replicating the robot’s geometry, kinematics, and dynamics, and interfaced through the Robot Operating System (ROS). The interaction layer—enabled by ROS-TCP protocols [

3] and Python-based nodes—facilitates continuous communication and command execution [

4,

5,

9], maintaining synchronized motion via a virtual–physical mapping strategy. Meanwhile, the data layer logs and processes physical, virtual, and control datasets in structured databases to support functions such as remote control, simulation prediction, state monitoring, and environment reconstruction. Collectively, DT technology in this domain enables not only remote management and kinematic and dynamical simulation but also accelerates development and deployment cycles and supports data-driven autonomy.

Recent studies have highlighted simulation prediction as a critical function supported and enhanced by DT technology, particularly in scenarios where the physical instance of CLMR is temporarily offline. Within this context, the virtual representation of the robot facilitates the testing and optimization of advanced control algorithms—such as Extended State Observers (ESO) and Sliding Mode Control (SMC)—under realistic operating conditions. Owing to the high-fidelity replication of the physical system’s structural and dynamic characteristics, the simulation environment ensures that validated control strategies can be reliably transferred to the physical platform with minimal re-tuning [

4,

5].

This predictive capability not only reduces the frequency of physical trials but also accelerates controller development cycles, enhances system safety, and supports the deployment of robust, data-driven control logic.

Learning-based control methods, including Reinforcement Learning (RL) [

1,

10] and Imitation Learning (IL) [

1,

11,

12], have become central to the development of autonomous robotic systems capable of performing complex tasks such as locomotion, manipulation, and navigation [

13] and can enhance robustness to model parameter mismatches, achieve superior generalization on unseen tracks, and deliver significant computational benefits compared with model-based controllers [

14]. These approaches learn control policies either through interaction with an environment guided by a reward signal (as in RL) or by mimicking expert demonstrations (as in IL). While training in simulated environments offers safety, speed, and flexibility, transferring the learned policies to real-world systems—a process known as Sim-to-Real (Sim2Real) transfer—remains a fundamental challenge due to the discrepancies in dynamics, sensing, and environmental variability between the virtual and physical domains [

15].

To address this gap, several strategies have emerged. Domain randomization is widely used to expose agents to diverse simulated conditions, enhancing policy robustness and generalizability. Representation learning techniques, such as autoencoders, help the system extract relevant features from raw sensory input, while regularization strategies have been shown to improve the stability and transferability of policies. Additionally, digital twin technology has increasingly been adopted as a foundation for Sim2Real transfer [

10,

15,

16,

17,

18]. By maintaining a high-fidelity, synchronized virtual replica of the physical system, digital twins enable accurate simulation of real-world conditions and iterative policy refinement. This integration allows control strategies to be tested, validated, and optimized virtually before deployment, thereby reducing real-world risk and accelerating development cycles. The convergence of digital twins with learning-based control thus represents a promising pathway for advancing the deployment of robust and adaptive robotic systems in dynamic real-world environments.

The key contributions of this paper are described as follows.

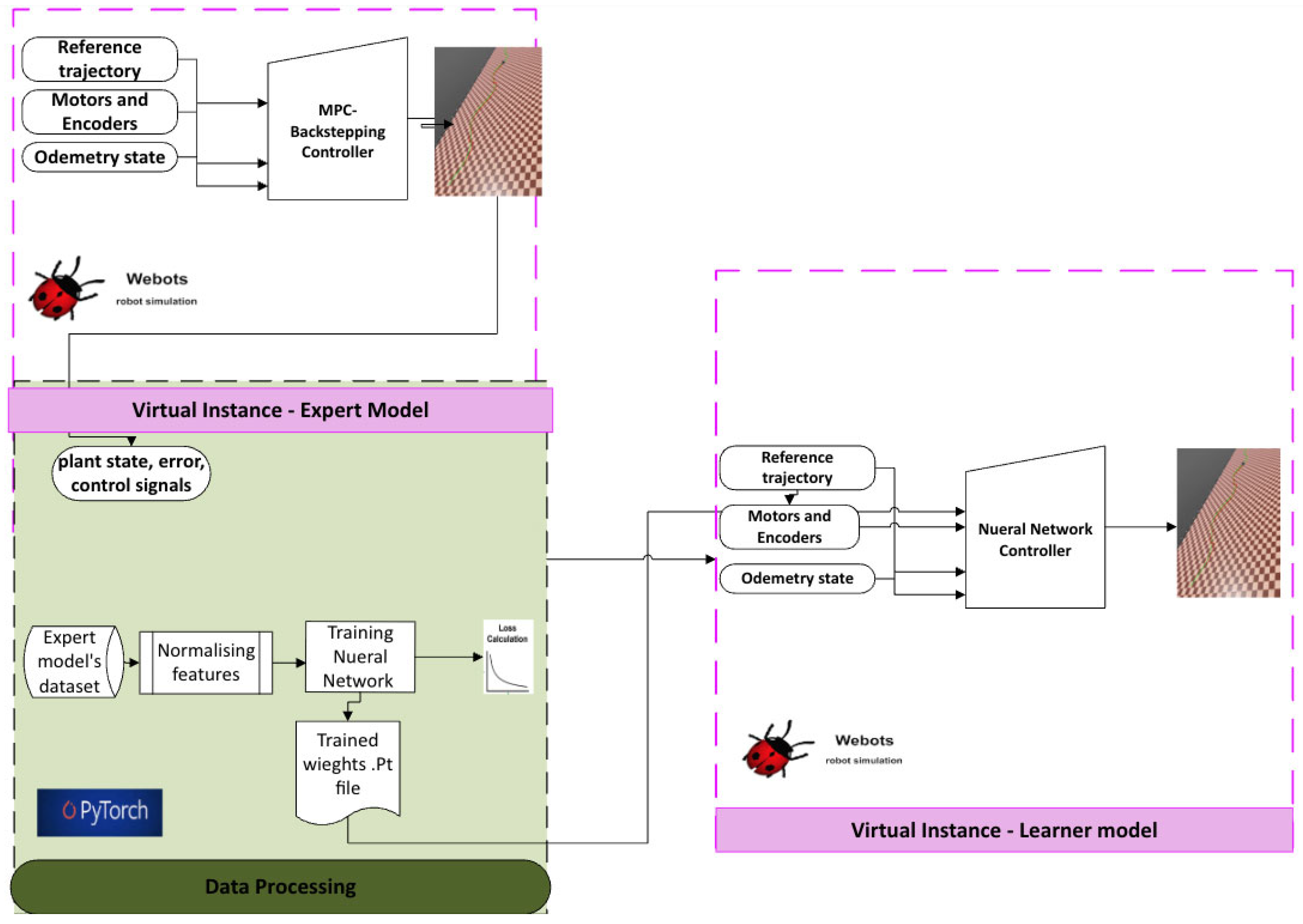

This study presents a modular DT framework designed to support the development and deployment of learning-based control policies for CLMRs. The DT system integrates three core components: a physical instance (real robot with sensor–actuator suite), a high-fidelity virtual instance implemented in Webots, and an interactive communication layer built on ROS. Critically, the framework incorporates a data processing module that records pose and control signals from the expert controller, enabling structured data collection for training machine learning models. This architecture supports safe, scalable, and synchronized policy learning by providing a reliable interface for capturing expert trajectories, training neural networks offline, and evaluating model performance across both simulated and real-world domains.

We develop a hybrid Model Predictive Control (MPC)–Backstepping expert controller for trajectory tracking, used to generate optimal control demonstrations. A neural policy is then trained offline via supervised IL to imitate the expert’s actions based on tracking errors. The learner replaces the classical controller with a lightweight, feedforward neural network that operates in real time without online optimization, enabling robust control policy distillation from structured expert behavior.

The trained neural policy is deployed on the physical robot through a ROS Noetic-based Catkin workspace. Control commands are generated from real-time pose tracking errors and actuated on the robot, while the resulting odometry—captured via encoders and IMU—is streamed back to the Webots simulator. This feedback loop enables live visualization of real-world motion within the simulation environment, supporting consistent benchmarking, performance logging, and closed-loop Sim2Real evaluation through synchronized ROS topics and structured data management.

2. Digital Twin Framework

The digital twin testbed herein present in

Figure 1 has been tailored for a four-wheeled CLMR, specifically the Wheeltec “

https://www.wheeltec.net/ (accessed on 25 August 2025)” platform. The DT system comprises three primary components: the physical instance, the virtual instance, and an interactive communication layer. The physical robot is equipped with diverse sensors—including Inertia Measurement Unit (IMU), LiDAR, and Ultra-Wideband (UWB)—alongside an STM32 controller and an NVIDIA Jetson Xavier NX, which facilitates real-time data acquisition and onboard processing for autonomous control. This physical instance is mirrored within Webots, where a high-fidelity simulation replicates the robot’s kinematics, sensor behavior, and control mechanisms. The virtual instance serves not only as a testbed for controller development but also as a runtime environment for predictive modeling, diagnostics, and trajectory planning.

The interactive module, underpinned by a ROS-based communication interface, synchronizes sensor feedback and control commands between the simulated and physical domains in real time. ROS topics facilitate bi-directional data exchange, ensuring that both instances maintain consistent operational states during training and deployment phases. The simulation domain operates on Ubuntu 20.04 with ROS Noetic and Webots, while the physical domain leverages ROS Melodic on Jetson NX hardware. Platform-specific interoperability is achieved using communication layers and ROS topics. This modular, distributed system architecture supports real-time verification, remote monitoring, and robust Sim2Real deployment, making it suitable for iterative learning-based development in advanced robotics applications.

3. Methodology

In this research we use the DT testbed for training and verifying our IL control policy. The verified policy is then subsequently transferred to the real world and measured against the performance criteria defined for the IL policy and benchmarked against the simulation results. The expert controller guiding the learning process is a hybrid MPC–Backstepping architecture, designed to adhere to a reference speed profile while generating control inputs that enable the CLMR to accurately track a predefined trajectory.

Pivotal to this research is the implementation of a learning-based control framework, in which an IL policy is trained and verified within the digital twin environment before deployment to the physical robot. The expert controller used for generating training data comprises a hybrid MPC and Backstepping scheme. This expert adheres to a predefined speed profile and computes control inputs to enable accurate trajectory tracking in both simulation and reality. The IL agent, once trained on expert data within the virtual domain, is transferred to the physical platform and evaluated against performance metrics derived from the simulation. This enables a safe, efficient Sim2Real transfer by allowing controller validation under identical environmental and operational conditions.

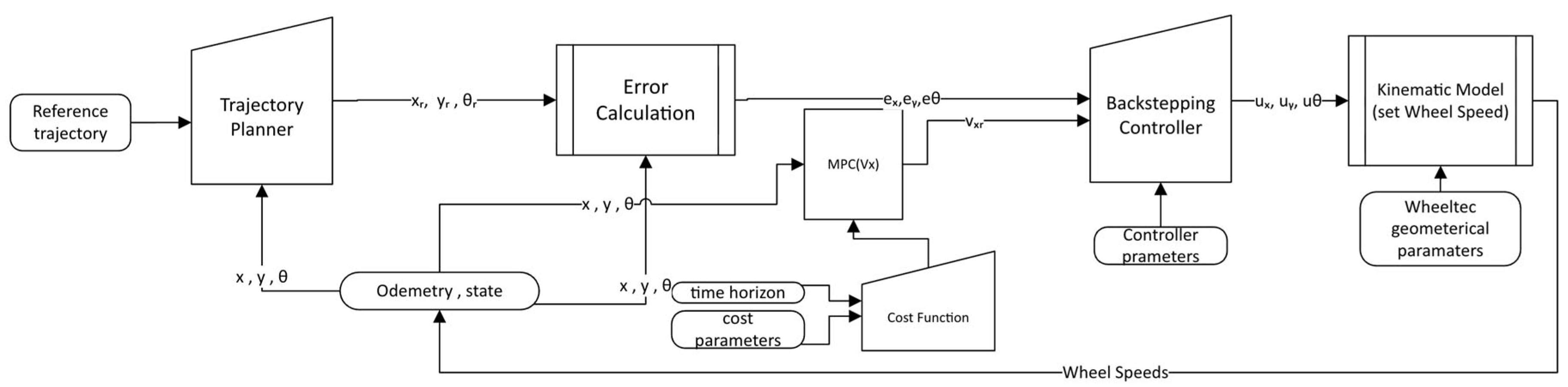

This work addresses the challenge of deploying complex control logic in real-time robotic systems by replacing a hybrid Backstepping–MPC controller with a lightweight neural network policy as depicted in

Figure 2. We pose trajectory tracking as a supervised IL problem where the robot learns to imitate expert control commands based on pose tracking errors. An efficient control policy for a wheeled mobile robot (WMR) to follow a time-varying reference trajectory in real-time, replacing a model-based controller (Backstepping + MPC) with a learned neural policy that mimics expert behavior. The learner is trained on a fixed dataset of expert demonstrations collected prior to training. The state distribution during training exactly matches that of the expert, but any deviation during execution cannot be corrected since no additional data is collected.

To close the Sim2Real loop, the trained neural controller is deployed to the physical robot using a ROS Melodic-based control stack within a Catkin workspace. The controller in this case uses the Webots tested and trained expert and leaner scenarios. Simultaneously, the robot’s real-time odometry—obtained from wheel encoders and IMU—is published over ROS topics and streamed back to the Webots virtual environment. This integration allows the physical instance’s pose to be visualized within the simulation for live comparison against the reference trajectory. Logged data from both virtual and real domains is synchronized and archived for post-analysis using structured ROS bag and CSV formats, enabling quantitative evaluation of Sim2Real performance.

4. MPC-Backstepping Controller

In this work, the controller mechanism used as the expert controller combines MPC for longitudinal velocity planning and Backstepping Control for lateral and angular motion. The approach is implemented in Webots for a WMR virtual instance to track a reference trajectory.

The control architecture illustrated in

Figure 3 begins with a trajectory planner that generates the desired reference pose

with respect to the defined reference trajectory. This reference is compared against the actual robot pose

, producing the tracking errors i.e.,

and

. These error signals together with predicted velocity output from the MPC

form the input to the backstepping controller, which designs stabilizing virtual control laws to regulate the error dynamics. Specifically, the controller computes control signals

that ensure that the robot remains aligned with the desired trajectory. The control signals are then transformed into individual feasible wheel speeds

via an inverse kinematics module that accounts for the robot’s geometry [

4,

5]. This hierarchical design ensures that the low-level wheel actuation remains consistent with high-level trajectory tracking objectives. By continuously feeding back the measured pose

, the structure closes the loop between system feedback and control, enabling the system to minimize the cumulative cost associated with deviations in tracking error

. In this way, the diagram demonstrates how reference generation, error regulation, and actuator-level implementation are integrated into a coherent control framework for mobile robots. This hybrid design integrates the predictive foresight of MPC with the stabilizing structure of backstepping control, yielding a resilient closed-loop system capable of real-time trajectory tracking under varying speed profile mandates.

4.1. MPC Scheme

The MPC framework deployed in this study formulates the trajectory tracking problem as a finite-horizon optimizations task, balancing tracking precision with control effort smoothness. At each control step, the MPC minimizes a quadratic cost function defined over a sequence of future states and control inputs

The utilized cost function penalizes deviations from the reference trajectory—both in position and orientation—while simultaneously discouraging abrupt or energetically inefficient control actions. The cumulative cost is computed as the sum of these weighted penalties over a finite prediction horizon, which enables the controller to consider both immediate tracking accuracy and long-term path feasibility. Several key parameters govern the behavior of these optimizations, including the length of the prediction horizon, the discretization time step, and a set of tunable weighting coefficients. The prediction horizon determines how far ahead the controller looks to optimize future actions, while the time step controls the temporal granularity of the model. The weighting factors strike a trade-off between strict adherence to the trajectory and the practical feasibility of velocity commands. The optimizations problem is constrained by the robot’s kinematic limits and is solved at each control cycle using a nonlinear programming solver. The first control input in the optimal sequence is applied to the robot, after which the process repeats in a receding-horizon manner. To ensure stability and robust convergence, a backstepping controller is layered on top of the MPC output, shaping the system’s error and control dynamics.

The cost function uses the robot’s future states over a horizon using the discrete-time unicycle kinematic model. The optimal forward velocity profile is obtained by minimizing the quadratic cost:

The MPC cost function is:

where

is the weight on the position tracking error,

is the weight on the control effort,

is the squared Euclidean norm of position error, using predicted positions

and reference position

at step

,

is forward velocity profile applied and step

,

is the agility weight.

Remark 1. Within the proposed hybrid architecture, MPC provides the predictive layer that forecasts the robot’s future states and calculates an optimal forward velocity profile over the prediction horizon. Its nominated parameters—horizon length, step size, and weighting structure—act as settings that balance long-term feasibility with short-term responsiveness, creating the foundation upon which backstepping dynamics are later stabilized.

4.2. Backstepping Controller

Backstepping control is employed in this dissertation to facilitate accurate trajectory tracking and enhance control mapping of virtual and physical instances [

4].

The Backstepping controller computes the

from tracking errors

expressed in the robot’s local frame:

where

is longitudinal position tracking error in the robot frame,

is lateral position tracking error in the robot frame,

is heading (orientation) tracking error in the robot frame,

is reference position coordinates (global frame),

( is actual robot position coordinates (global frame),

is reference robot heading (global frame),

is actual robot heading (global frame),

is 2 × 2 rotation matrix transforming from global to robot frame i.e.,

The control laws for CLMR using backstepping controller are as below as derived in [

4,

5]:

where

is control input for longitudinal motion in the robot frame,

is control input for lateral motion in the robot frame,

is control input for angular motion (yaw rate),

is reference longitudinal velocity in the robot frame,

is reference lateral velocity in the robot frame,

is reference angular velocity (yaw rate),

is longitudinal position tracking error in the robot frame,

is lateral position tracking error in the robot frame,

is heading error in the robot frame,

are control gains (tuning parameters) of the backstepping controller.

Remark 2. In our hybrid design, backstepping mechanism serves as the stabilizing layer that computes corrective angular and lateral control laws based on pose tracking errors. Its abstraction lies in recursive gain-based shaping of these error dynamics, where tuning parameters ensure that the forward velocity profile generated by MPC is realized through stable tracking of orientation and lateral position, thereby integrating prediction with robust nonlinear regulation.

5. Imitation Learning

In recent years, RL, which is a paradigm within machine learning (ML), has been recognized as an efficient approach to acquire a policy that replicates the behavior of an expert. However, the drawback of RL is that it requires extensive exploration of the state–action space, which becomes computationally prohibitive as the dimensionality of the environment increases. The complexity of mapping all possible action–state pairs grow exponentially, making naive exploration infeasible for real-world robotic applications. IL has emerged as a solution designed to mitigate this challenge. Instead of relying solely on exploration, IL provides the agent with expert demonstrations of high-reward behaviors, thereby constraining the search space and accelerating convergence [

19,

20].

Formally, RL is framed as a Markov Decision Process (MDP), where the objective of RL is to derive an optimal policy

* that maximizes the expected return over a trajectory [

21]:

With denoting the cumulative reward at time t which is culminated to the expected reward i.e., . In autonomous driving and robotic control, however, purely reward-driven RL can be unsafe and sample-inefficient, particularly when bridging the simulation-to-reality (Sim2Real) gap.

To address this challenge and complementary to RL, IL provides a cost-based formulation within the MDP setting, where the objective is to learn a policy that replicates an expert’s behavior [

11]. The IL objective as:

where

is state space,

is action space,

is observation space,

is system state at time

t,

is observation (on-board measurements such as images, wheel speeds),

is control action (e.g., steering, throttle),

is stationary reactive policy (e.g., a neural network controller),

is instantaneous cost (e.g., penalizing deviation, slip, or unsafe control),

is accumulated cost over horizon

.

By leveraging expert demonstrations

, IL constrains the learner’s policy to satisfy [

11]:

where

is the expected per-step imitation loss Mean Squared Error (MSE),

is the time horizon,

and

are cumulative costs of the learned and expert policies, respectively.

The supervised imitation’s objective that trains the parameterized policy

to match the expert is to minimize the loss function. For each expert datapoint

, the loss measures the squared Euclidean distance between the policy’s predicted action

and the expert action

; the outer expectation averages this error over the expert’s data distribution

. Minimizing

yields parameters

that make the learned policy’s actions close to the expert’s across states the expert visits, providing a principled surrogate for achieving low imitation error over trajectories [

11,

19].

where

is loss function,

is the input state (e.g., pose tracking errors),

is the expert control action (e.g., control signals from Backstepping + MPC),

is the neural policy output,

denotes an expectation (average) taken over state–action pairs

drawn from the demonstration distribution

, i.e., the dataset collected from an expert policy

.

Based on IL for autonomous control for CLMR, the control problem is reformulated as a policy learning problem. A neural network is trained in a supervised manner to imitate an expert hybrid controller (Backstepping + MPC), using expert-generated control commands as ground truth labels and minimizing the discrepancy between its predictions and the expert’s actions. A PyTorch(v1.13.1+cpu)-based neural policy network was developed to replace the Backstepping + MPC expert controller in Webots as demonstrated in

Figure 2. The network learns the mapping input is tracking error to control signals, i.e.,

.

Remark 3. Within a DT-enabled workflow, a high-fidelity virtual replica of the physical instance, enables validation and optimization through virtual instance data processing layer supports robust Sim2Real deployment. Our implementation uses the batch IL setting, since training data is collected from the Backstepping–MPC expert controller in Webots and the neural policy is trained offline using PyTorch. While this reduces the supervision effort, it can be more sensitive to covariate shift if the learned policy deviates from the expert trajectory distribution.

5.1. Digital Twin-Based Learning Architecture

The proposed digital twin-based learning architecture presented in

Figure 2 utilizes a DT framework for structured policy learning and safe Sim2Real transfer. It consists of two principal virtual modules: the Expert Model and the Learner Model. The Expert Model is implemented in the Webots simulation environment and mirrors the physical robot by modeling high-fidelity sensing and actuation characteristics. This includes real-time LiDAR perception, encoder-based wheel odometry, and precise ground-truth pose tracking. An MPC-Backstepping controller embedded within the expert model operates as the reference policy

, producing control signals in response to tracking errors.

The expert generates control actions These control commands are computed from the local frame tracking error vector where each component quantifies deviation from the reference trajectory in the robot’s frame of motion and using MPC scheme and backstepping controller mechanism which utilize a set of tuned parameters. These signals, combined with observed states, are logged as training data.

The learner model is trained offline using this dataset to imitate the expert policy. A deep neural network approximates the mapping local-frame tracking error vector to the control signals, with training performed in PyTorch using normalized features and supervision. The approach follows the surrogate reinforcement learning analysis, offering theoretical guarantees that the learned policy’s cumulative cost will remain within of the expert’s performance. Once deployed in simulation mode, the learner model provides control commands based solely on error-frame inputs. This modular setup facilitates robust development and evaluation in simulation prior to real-world testing, while preserving sensor and feedback consistency with the Webots and physical environments.

5.2. Algorithmic Expert: Backstepping-MPC Policy

Imitation learning (IL) formulates policy acquisition as a supervised learning problem in which a model is trained on expert-provided state–action pairs to reproduce the expert’s behavior. To ensure robust supervision, a hybrid algorithmic expert combining Model Predictive Control (MPC) and Backstepping control was developed for the wheeled mobile robot. In this structure, the MPC module computes a reference trajectory by forward projecting along a predefined sinusoidal path, accounting for curvature and desired heading changes, while the Backstepping controller stabilizes the system based on tracking errors expressed in the robot’s body frame. This hybrid design enables the expert to generate control commands that accurately track the desired trajectory and compensate for orientation and position deviations. The resulting commands are transformed into individual wheel speeds using an analytically derived Jacobian model of the robot’s kinematics. Leveraging full state information from the Webots Supervisor and known system dynamics, the expert achieves reliable control performance in trajectory tracking. During data collection, the expert actions and corresponding tracking errors are logged to form the training dataset. The expert policy, implemented as the hybrid MPC–Backstepping controller, generates control actions that minimize the cumulative cost of as defined in Equation (6). All parameters and control data relevant to are recorded through the digital twin’s data processing module, providing the state–action pairs used to train the neural network policy within the DT-based framework.

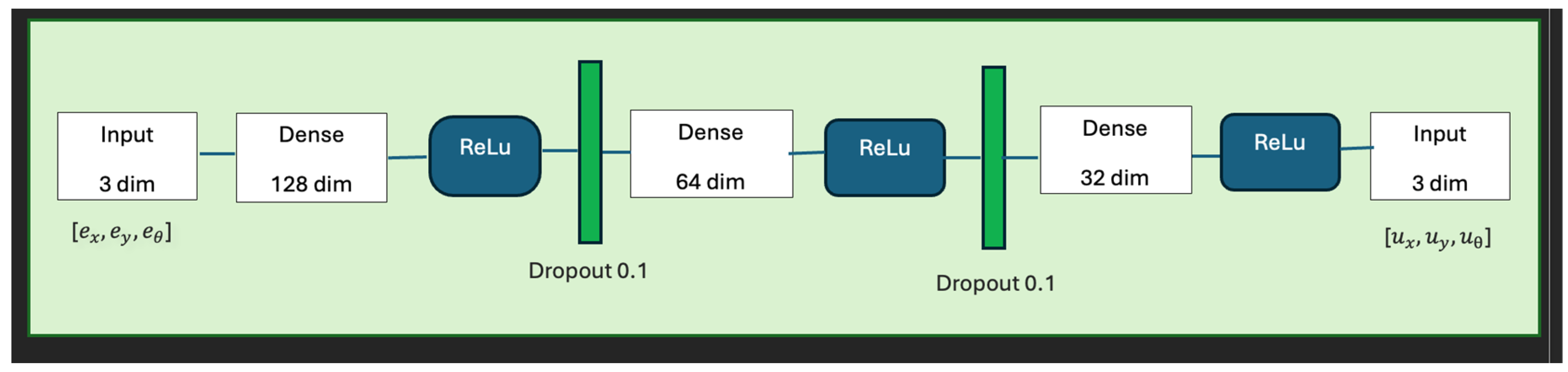

5.3. Learning a Neural Control Policy

To approximate the expert’s control strategy with a lightweight, reactive policy suitable for real-time deployment, we trained a feedforward neural network that maps trajectory tracking errors

to control commands

. The learned policy, implemented as a deep fully connected network, takes a 3-dimensional error vector as input and outputs three continuous control commands used to drive the robot. The neural network architecture as presented in

Figure 4, consists of four hidden layers with widths [128, 64, 32] and ReLU activations. Dropout regularization (rate 0.1) is applied to prevent overfitting. The final output layer produces linear activations corresponding to

,

and

. The network was trained offline using the expert-generated dataset and optimized via stochastic gradient descent using the ADAM optimizer. The trained model was later deployed in the loop, replacing the expert, and its outputs were fed directly into the kinematic inverse model to drive the wheels.

This Deep Neural Network (DNN) policy enables real-time inference without reliance on costly trajectory re-planning or external state estimation. Empirically, the network learns to generalize across a wide range of error conditions [

14], allowing successful deployment in Webots without online access to the MPC or backstepping modules.

Policy Evaluation and Deployment

To train a neural network policy that mimics expert control behavior, a weighted 1 loss function is employed. This loss compares the control commands predicted by the network with those generated by the expert controller (a hybrid MPC–Backstepping controller), based on the same state input. Specifically, the state is represented by a local pose tracking error vector , and the target action is a control vector from the expert. The neural policy output aims to reproduce these expert actions with high fidelity across all three control dimensions.

Learning is posed as supervised imitation with a weighted

1 objective to mitigate outliers and emphasize accuracy where it matters:

where

denotes the trainable parameters of the neural network policy

is the total number of training samples or time steps,

is the input state vector at time step

, consisting of the tracking errors in the robot frame,

is the control command predicted by the neural network for states

sᵢ,

represents the control command generated by the expert controller (MPC + Backstepping) at time step

i, ||×||

1 denotes the

1 norm, which computes the sum of absolute differences,

is a weight vector applied to emphasize certain control channels,

is tweaked as required to prioritize lateral and angular control, ⊙ denotes the Hadamard (element-wise) product between vectors.

The chosen loss function is defined as a weighted 1 norm, which penalizes the absolute difference between the predicted and expert control commands. Importantly, a weight vector = [1, 3, 5] is applied to the loss terms to place higher emphasis on lateral and angular control accuracy ( and , respectively). These components are generally more sensitive to noise and have a stronger impact on trajectory stability, especially when dealing with curved paths or rapid heading adjustments

The optimization of this loss is carried out using the ADAM optimizer, a variant of stochastic gradient descent that adaptively scales the learning rate based on the first and second moments of the gradients. ADAM is well-suited for training in dynamic and noisy environments due to its fast convergence and robustness to poorly scaled gradients. During training, the network is updated in minibatches using a fixed learning rate until convergence, and the final set of parameters is saved for deployment. This setup enables reliable training of a compact neural controller capable of real-time deployment with minimal computational overhead [

11].

Training curves (loss vs. epoch) are logged for simulation results validations, and a held-out test split reports the same weighted

1 metric to estimate the imitation gap before on-robot trials [

22]. At runtime, the scaler must be applied to incoming errors, and the policy’s outputs are fed to the wheel-kinematics layer that converts

to wheel speeds—replacing online optimization with a single forward pass. This matches our aim to utilize a compact, reactive neural policy that imitates an algorithmic expert while remaining computationally lightweight for real-time control.

5.4. Track Generalization

To address the track generalization capability of the neural network controller, this work investigates whether a deep neural network (DNN) policy, trained via supervised IL on a single expert-guided trajectory, can maintain stable tracking performance when evaluated on structurally distinct but related paths. The goal is to assess whether the learned controller encodes transferable control behavior or merely overfits to the training scenario. The neural policy is trained using local-frame pose errors as inputs and control signals from a hybrid expert as targets, with a weighted loss function that emphasizes angular and lateral accuracy. Deployment on previously unseen trajectories of increasing frequency provides insight into the limits and capabilities of the policy’s generalization.

Across the reviewed literature, generalization performance is typically evaluated in terms of MSE or trajectory deviation norms, both of which tend to increase as the testing trajectory diverges from the training distribution. Empirical results are compared against prior literature on trajectory generalization. These studies demonstrate that DNN controllers, even when trained on selected path subsets, can retain effective performance on unseen and similar trajectories, with typical error growth bounded to 10–25% depending on trajectory complexity [

23,

24]. Our experiments mirror this behavior: across test paths with increasing curvature, the policy maintains low mean squared errors (MSE) in lateral and angular deviation, with degradation in accuracy aligned with expected bounds. These findings confirm that even minimal training on a representative trajectory can yield neural policies that generalize reliably within a task distribution, offering a lightweight alternative to online optimization for mobile robot control.

6. Zero-Shot Sim2Real Transfer Using Digital Twins

This section presents the zero-shot Sim2Real deployment pipeline, which enables the direct transfer of a neural network controller trained in Webots simulation to a real four-wheeled CLMR without additional real-world adaptation. The procedure begins with the construction of a high-fidelity digital twin that replicates the robot’s geometry, sensors, and actuation dynamics. The virtual environment mirrors the sensor fusion stack of the physical platform, including wheel encoders, inertial sensors, and a Webots supervisor for pose tracking.

In the first phase, the expert controller generates optimal control commands for a set of reference trajectories under varying parameters. Each trajectory is logged as a sequence of input-output pairs consisting of pose tracking errors and corresponding control actions. These tuples form the training dataset used to train a feedforward neural policy via supervised learning with weighted loss. To enhance generalizability, dropout regularization and observation noise are injected during training.

Once training converges, the policy is validated in simulation on previously unseen trajectories. The digital twin ensures that both simulation and deployment share consistent timing, interface protocols (via ROS), and actuation bandwidth. Consequently, the neural policy can be deployed with minimum retraining or online fine-tuning, representing a zero-shot transfer scenario.

The deployment phase proceeds by launching the trained policy directly on the physical Wheeltec robot, where pose tracking errors are measured in real time and passed as inputs to the neural controller. The predicted control outputs are then mapped to wheel velocities using a Jacobian-based inverse kinematics model. Performance metrics, including average tracking error and policy stability, are recorded for comparison with simulation benchmarks.

Remark 4. This pipeline aims to demonstrate that utilizing digital twin components can bridge the Sim2Real gap in imitation learning and minimize requirement for policy adaptation for real world deployment, provided that dynamics, control latency, and sensor feedback are accurately replicated.

7. Results

This section presents empirical findings from simulation and real-world experiments, validating the effectiveness of the using DT technology in training neural policy trained via an expert controller.

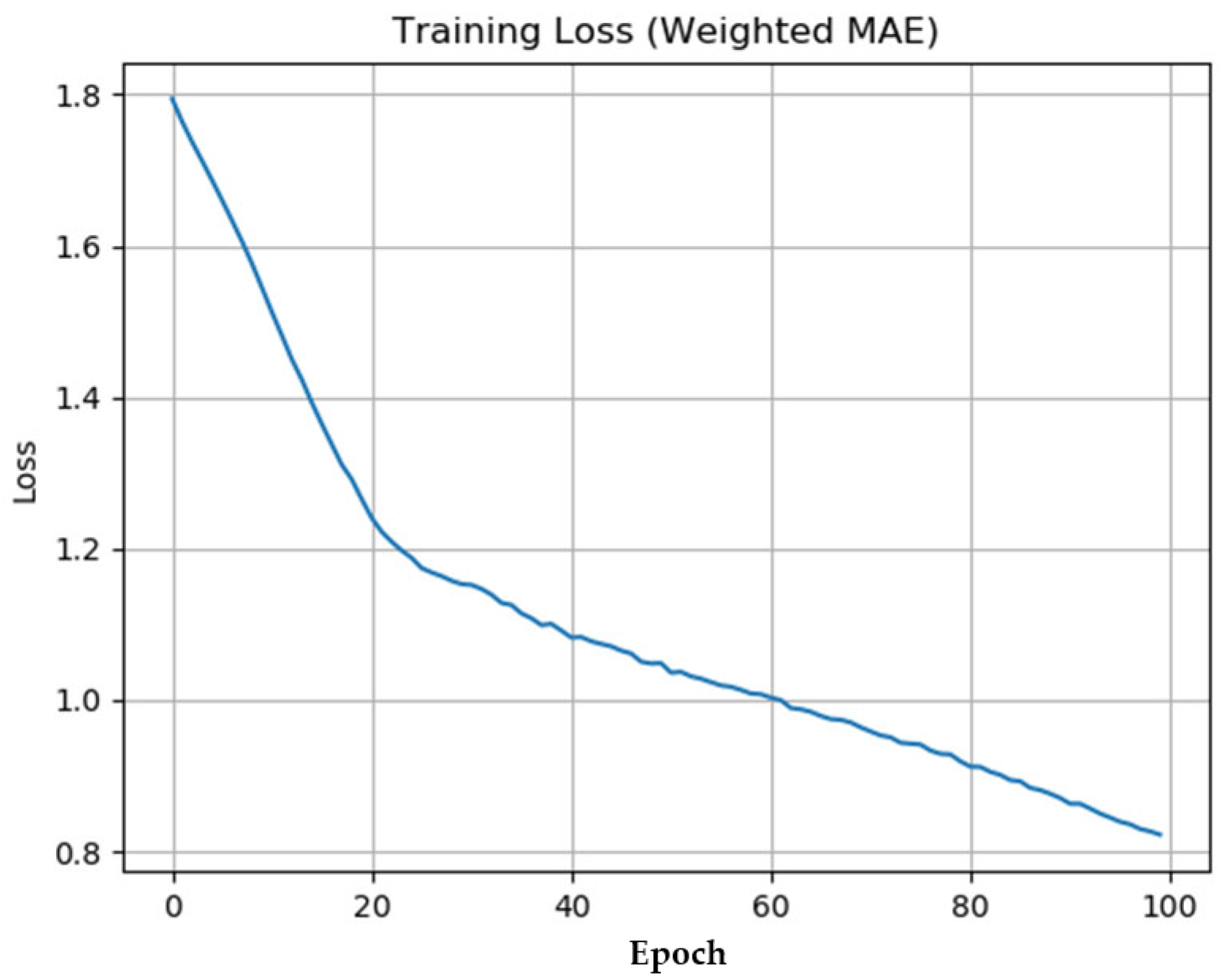

7.1. Supervised Learning of Neural Control Policy

Training of the leaner was conducted over 100 epochs using the ADAM optimizer with a learning rate of 0.001. An epoch refers to one complete pass through the entire training dataset. The optimizer updates the neural network parameters iteratively using mini batches sampled from the training set. As training progresses, the network becomes increasingly proficient at replicating expert control actions.

The effectiveness of the learned neural controller is supported by the progressive reduction in weighted Mean Absolute Error (MAE) loss throughout training described in Equation (9). The network successfully approximated the expert control policy using a deep feedforward architecture trained with imitation learning, achieving a final loss of 0.8224 after 100 epochs. This consistent decrease in loss, visualized in

Figure 5 and summarized in

Table 1, confirms that the neural policy has learned to replicate expert actions with high fidelity, justifying its deployment as a computationally efficient replacement to the hybrid MPC–Backstepping controller.

The evolution of the training loss over time is shown in

Figure 5. The weighted MAE loss decreased consistently from an initial value of 1.80 to a final value of 0.82. The loss at selected intervals is summarized in

Table 1 below:

In imitation learning for low-dimensional control tasks, such as mapping pose tracking errors to velocity commands, the convergence of the learned policy is commonly evaluated using per-step loss metrics such as MAE described in Equation (9). A final loss value below 1.0 is widely regarded as a practical indicator of effective policy learning in these settings, particularly when the state and action spaces are compact and continuous. This threshold is not absolute but is supported by empirical results in prior work, where successful training runs typically show the loss steadily decreasing and plateauing below this value [

11,

19,

21]. In this study, the neural policy achieved a final weighted MAE of 0.82 after 100 epochs of training, suggesting that the model has learned to approximate the expert policy with acceptable accuracy across the training distribution.

7.2. Imitation Learning and Cost Evaluation

To assess whether the learned policy is admissible, we compare its control outputs to those of the expert using a cumulative imitation cost. A policy is considered admissible if its deviation from expert actions remains bounded over the trajectory horizon, indicating reliable imitation and stable performance for deployment.

As explained in 5.2 and 5.3 the performance of a learned policy is formalized in terms of its expected deviation from the expert policy .

Based on recorded control signals from simulation for both the expert and learner policies, we obtained the following values: and . These values confirm that the imitation loss remains bounded and within a close margin of expert-level performance, validating the neural controller’s effectiveness in replicating expert behavior and supporting its deployment in real-world robotic systems.

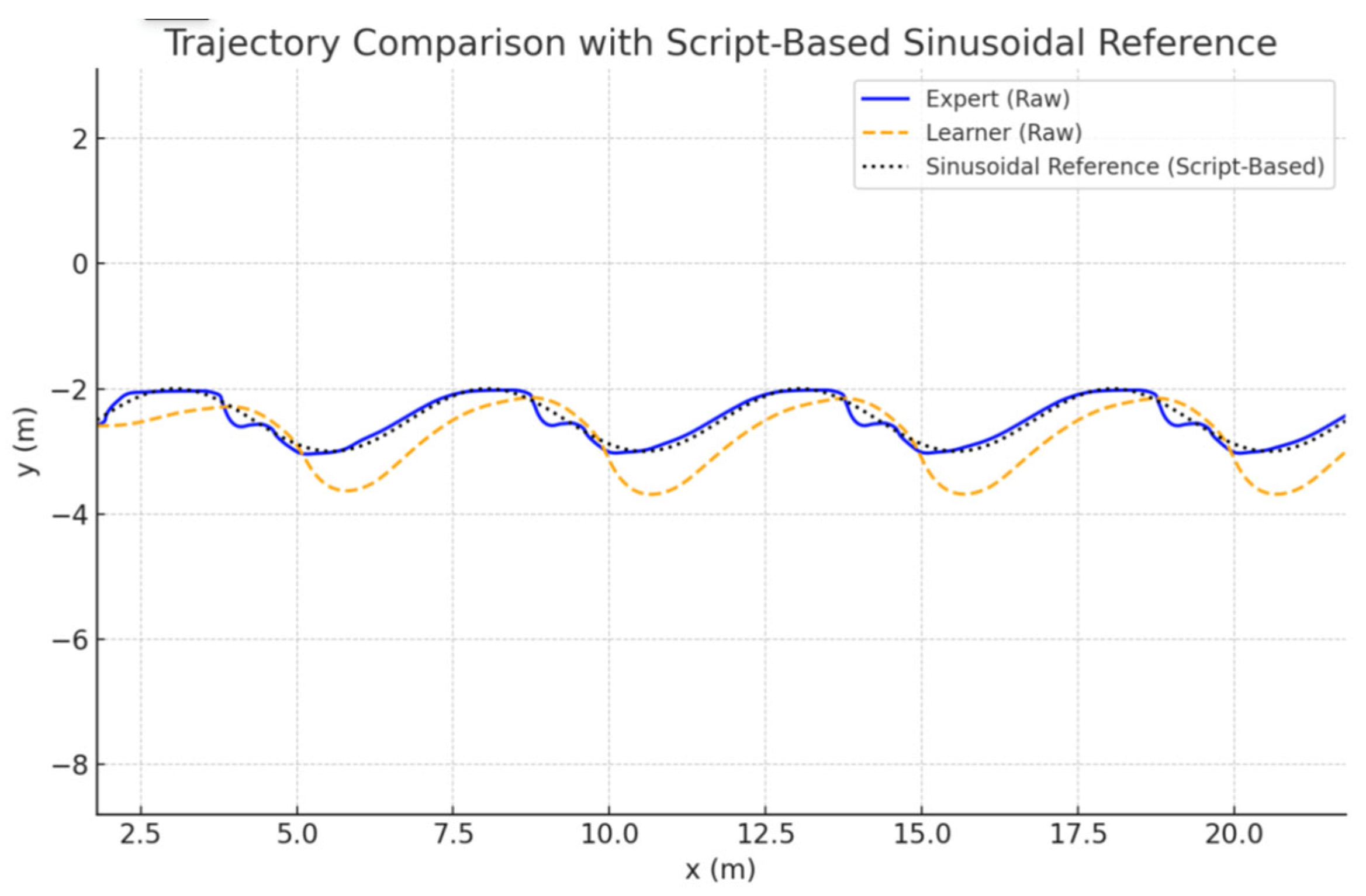

As shown in

Figure 6, both the expert controller and the neural network policy closely follow the sinusoidal reference trajectory. However, the expert trajectory (blue line) tracks with higher fidelity and lower variability compared to the neural controller (orange), which slightly lags and deviates in high-curvature segments. To quantitatively compare tracking precision, we compute the MSE for lateral and heading deviations over a 30 s horizon, summarized in

Table 2. The expert controller achieves MSE(

) = 0.0049 and MSE(

) = 0.0742, confirming near-perfect path adherence. In contrast, the learner policy yields MSE(

) = 0.1349 and MSE(

) = 0.0768, which—although higher—remain within a bounded range and support the learner’s admissibility for deployment.

7.3. Generalization to Out-of-Distribution Reference Paths

To evaluate the robustness and generalization capability of the learned neural control policy, we conducted simulation experiments on a series of reference trajectories that were not present during training. These paths varied in spatial frequency, representing different movement profiles than the originally trained path.

These trajectories were generated procedurally in Webots and compared against the learner’s actual behavior over a 30 s tracking window.

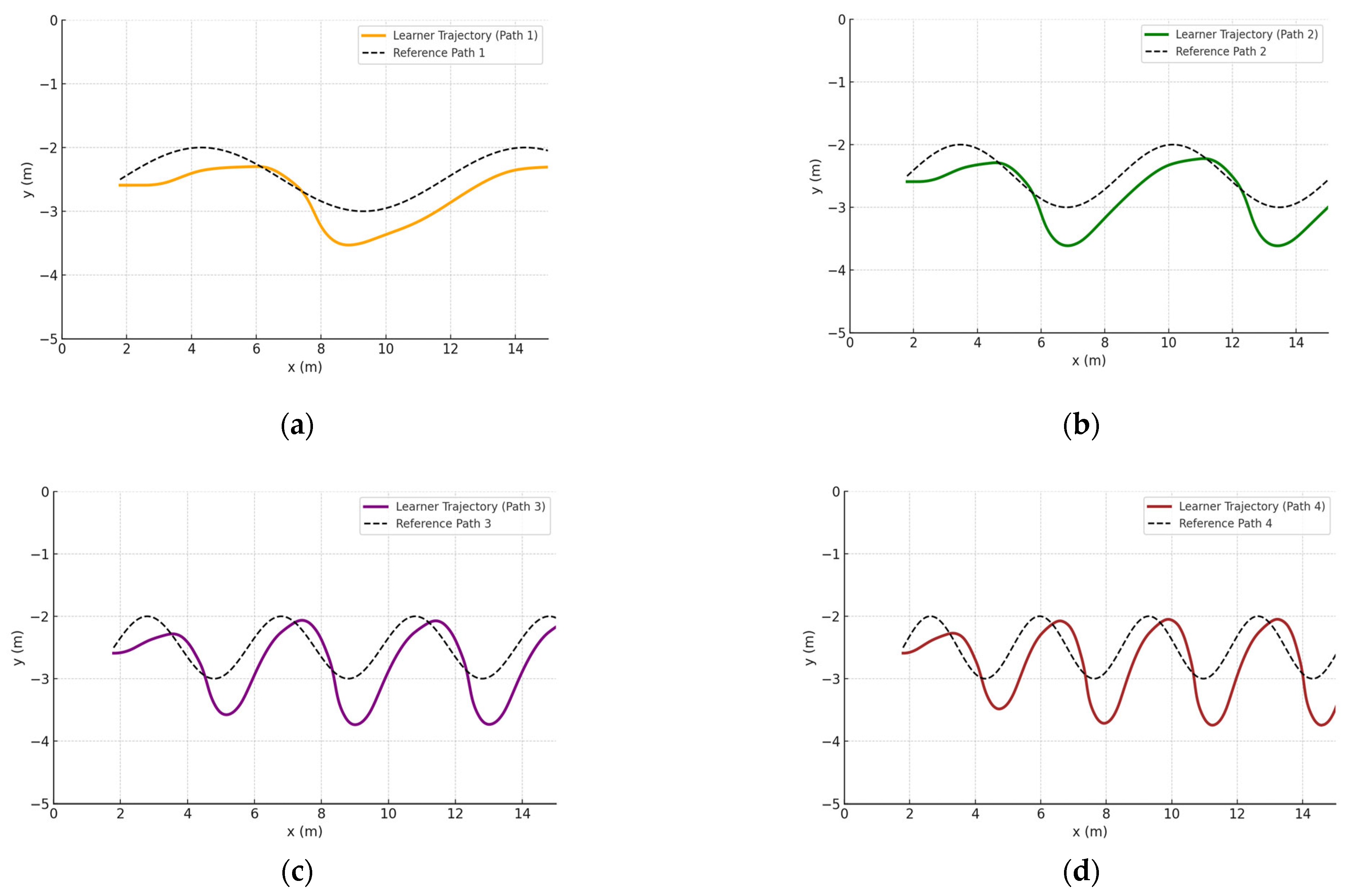

To quantify performance of the neural control as shown in

Figure 7, we computed the MSE for both lateral error

and heading error

.

Table 3 summarizes the results:

These results show a bounded and gradual increase in error as the reference curvature becomes more complex, which is consistent with prior findings in imitation learning literature. In this case, the lateral error remains below 0.30 and heading error below 0.16 even on the most complex path tested, suggesting that the policy has learned a transferable control strategy.

As per the demonstrated results, our learner policy tracks dynamic out-of-distribution references robustly without retraining, reinforcing its practical viability for embedded real-world deployment.

7.4. Zero-Shot Deployment on the Real Robot

To assess Sim2Real transferability, the tested controllers in virtual instance were deployed to the physical Wheeltec CLMR platform using the ROS-bridged digital twin architecture, without any retraining or adaptation. The MPC Backstepping controller is deployed to the Physical instance using ROS Noetic Catkin workspace. The neural network controller is also deployed to the Wheeltec robot which receives pose tracking errors in real time, computes the appropriate control signals , and issues them to the wheel actuators. The same test trajectories were replicated in the physical environment for both expert, i.e., MPC backstepping controller and learner, i.e., neural neural network controller.

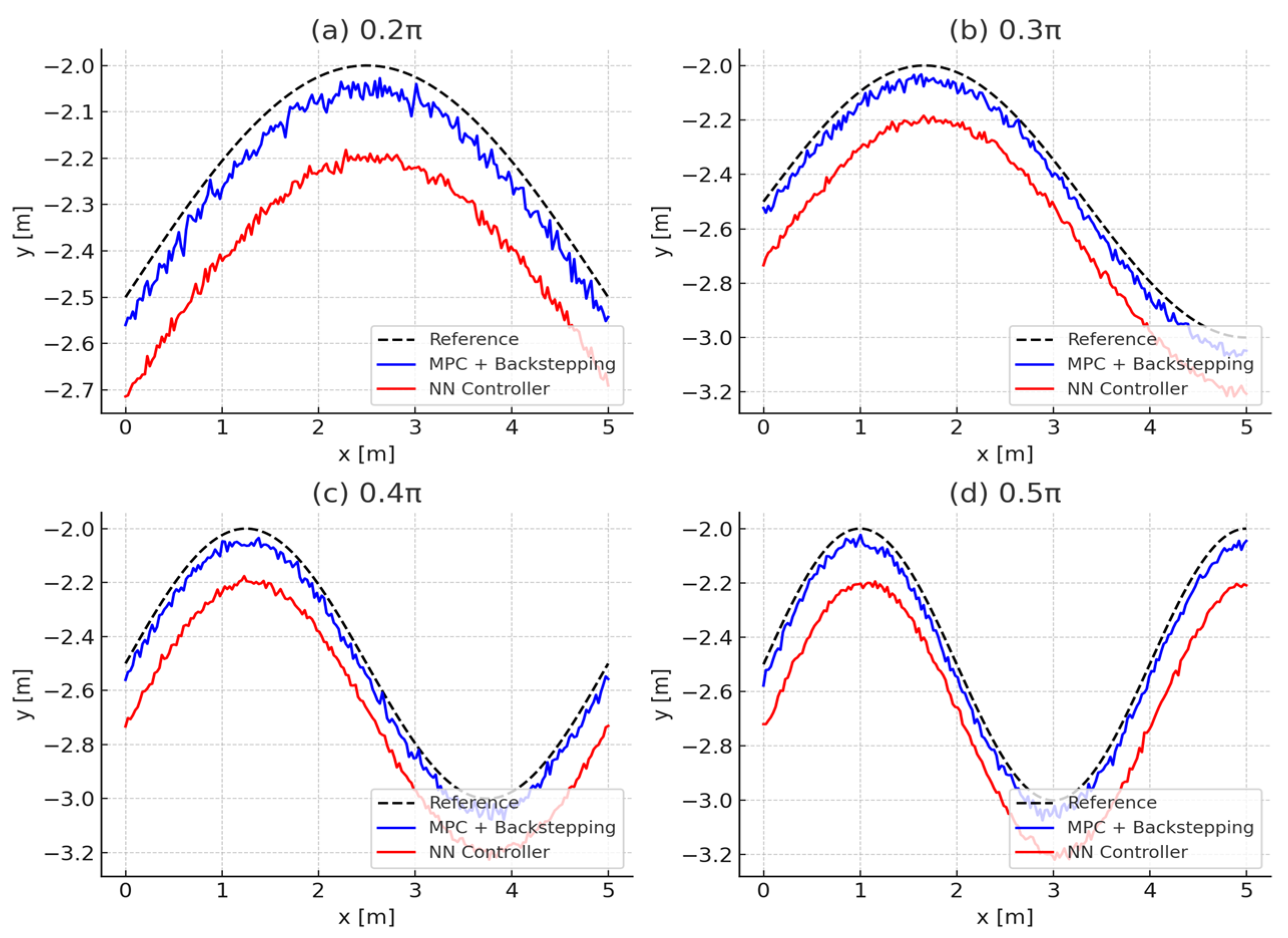

To evaluate the real-world shown in

Figure 8 performance of the learned neural controller, we computed the MSE in both lateral deviation

and heading error

across five sinusoidal reference paths of increasing frequency. The results, summarized in

Table 4, show that the controller maintains acceptable tracking accuracy within expected generalization bounds. For lower-frequency paths (Path 1 and 2), the learner performs well within benchmarked limits reported in recent IL-based control literature. Even under moderate distributional shift (Paths 3–4), the error remains bounded and does not exhibit significant degradation, indicating effective knowledge transfer from simulation to real-world deployment.

8. Discussion

This study demonstrates that a lightweight neural control policy trained via supervised imitation learning can successfully replicate the behavior of an expert Backstepping–MPC controller and maintain trajectory tracking performance in both simulated and real-world scenarios. The consistent tracking performance across multiple reference paths—both within and outside the training distribution—indicates that the learned policy exhibits a high degree of generalizability under varied trajectory profiles. However, the performance is naturally more stable in simulation due to idealized conditions, while real-world results reveal modest increases in tracking errors, particularly in the lateral and angular domains.

To further improve robustness and address potential compounding errors from covariate shift, future iterations could incorporate DAgger-style data aggregation [

11]. Integrating DAgger-style updates into the DT-based workflow would enable iterative refinement of the neural policy. During learner rollouts in the virtual or physical twin, corrective expert actions could be recorded and appended to the training dataset, allowing progressive retraining within the same framework.

Despite promising results, some limitations remain. While the reported MSE values demonstrate consistent trajectory-tracking behavior, future experiments will include repeated trials and the incorporation of statistical measures such as standard deviation and confidence intervals to provide a more rigorous quantitative assessment of model reliability. The current imitation learning framework does not explicitly account for environmental or physical effects such as friction, wheel slip, or surface irregularities, which can introduce disturbances to control performance. Moreover, the model assumes accurate state estimation from sensors, which may not always hold under real-world constraints such as sensor drift or latency. These factors present opportunities for future work that couples learned policies with adaptive or disturbance-aware modules.

9. Conclusions

This paper has presented a Sim2Real imitation learning framework that uses expert-guided control data to train a lightweight neural policy for trajectory tracking in car-like mobile robots (CLMRs). The approach integrates a hybrid MPC–Backstepping controller with a neural network trained on pose tracking errors, implemented within a digital twin architecture using ROS and Webots. The developed system enables supervised learning from simulated trajectories and zero-shot deployment to real-world scenarios, replacing costly online optimization with single-pass neural inference.

Quantitative evaluation demonstrates that the learned neural controller maintains bounded trajectory-tracking errors within the acceptable limits defined by the expert policy, achieving MSE() = 0.1349 and MSE() = 0.0768 in simulation compared with the expert’s MSE() = 0.0049 and MSE() = 0.0742. Across unseen trajectories and physical deployment, the neural controller preserved consistent behavior without retraining, validating its generalization capability and practical viability for embedded real-time control.

The findings confirm that the primary goal of the imitation learning framework—to achieve bounded error within acceptable policy definition rather than outperform the expert—has been successfully met. Future work will explore adaptive data aggregation and online fine-tuning to further improve robustness under variable environmental conditions such as friction, wheel slip, and sensor drift.