Abstract

Cytokinins (CKs) are a chemically diverse class of plant growth regulators, exhibiting wide-ranging actions on plant growth and development, hence their exploitation in agriculture for crop improvement and management. Their coordinated regulatory effects and cross-talk interactions with other phytohormones and signaling networks are highly sophisticated, eliciting and controlling varied biological processes at the cellular to organismal levels. In this review, we briefly introduce the mode of action and general molecular biological effects of naturally occurring CKs before highlighting the great variability in the response of fruit crops to CK-based innovations. We present a comprehensive compilation of research linked to the application of CKs in non-model crop species in different phases of fruit production and management. By doing so, it is clear that the effects of CKs on fruit set, development, maturation, and ripening are not necessarily generic, even for cultivars within the same species, illustrating the magnitude of yet unknown intricate biochemical and genetic mechanisms regulating these processes in different fruit crops. Current approaches using genomic-to-metabolomic analysis are providing new insights into the in planta mechanisms of CKs, pinpointing the underlying CK-derived actions that may serve as potential targets for improving crop-specific traits and the development of new solutions for the preharvest and postharvest management of fruit crops. Where information is available, CK molecular biology is discussed in the context of its present and future implications in the applications of CKs to fruits of horticultural significance.

1. Introduction

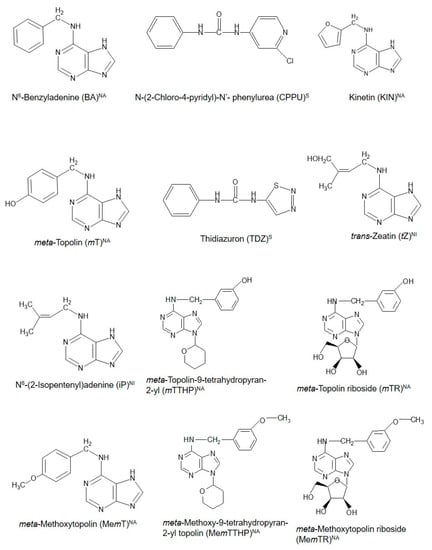

Cytokinins (CKs) are a unique class of plant growth regulators (PGRs) with a long and interesting history. Their existence as compounds capable of inducing cell division in cultured plant tissues was first documented more than 100 years ago [1]. With the discovery of an increasing number of compounds with CK-like actions in plants even to date, CKs are thus broadly grouped as natural (purine-based molecules, which are either isoprenoid or aromatic CKs) or synthetic CKs, which are urea-based [2]. Figure 1 shows the structural configurations of some existing natural and synthetic CKs. These CKs are considered to possess potential influence throughout the entire course of a plant’s life from embryogenesis until death in both lower and higher plants, as evidenced in the diverse physiological and biochemical functions during the life cycle of the different organisms [2,3,4]. They are involved directly or indirectly in different plant physiological processes such as the regulation of seed germination, shoot elongation and proliferation, induction of flowering, fruiting and seed set, and senescence [5,6,7,8,9,10]. Particularly, their roles in fruit set, delay of senescence processes—including fruit ripening and defoliation [11], which are concomitant with the release of buds from apical dominance [12], remain fundamental to the successful production of many horticultural fruit crops. Coupled with the development of genetically improved crop varieties and the application of improved agronomic practices, the use of PGRs including CKs has contributed positively to the green revolution and subsequent increase in agricultural productivity globally [13]. However, fundamental knowledge of the diverse roles of CKs in plants remains fragmented, and there is greater scope to deepen our knowledge of how CKs function and regulate cellular mechanisms that control plant growth and development. This knowledge will enable greater exploitation and application of CKs in horticultural fruit production. Recently, Koprna et al. [14] highlighted the potential of CKs as agrochemicals in pot and field experiments as they improve the growth dynamics and yields of a wide range of plants, including horticultural fruit crops.

Figure 1.

Chemical structures of cytokinins (CKs) used in propagation, preharvest, and postharvest stages during the production of some common horticultural fruit crops. NA = natural aromatic CK; NI = natural isoprenoid CK, and S = synthetic CK.

With more than 80 commonly known species of horticultural fruit crops available, their relevance to offset food and nutrition security concerns among the ever-increasing global population cannot be overemphasized. For centuries, horticultural fruit crops have been cultivated (mainly via conventional methods) as important dietary foods serving as the major sources of vitamins, antioxidants, and fibers for human needs [15,16]. As an indication of their economic and commercial values, the global production of the major fruit crops, including banana, apple, orange and mango, has witnessed a consistent and dramatic increase according to the Food and Agriculture Organization (FAO). Statistics from the FAO show that between 2000 and 2017, the production of mangoes, mangosteens, and guavas rose from 20 to over 40 million tonnes while banana production experienced a compound annual growth rate of 3.2% over the same period (http://www.fao.org/statistics/en/). Figures for banana cultivation were on a record high in 2017, reaching 114 million tonnes from 67 million tonnes in 2000. Other fruit crops such as oranges, apples, and grapes also showed positive trajectories in terms of their production, even though their incremental trends did not surpass that of banana (http://www.fao.org/statistics/en/). While these increases remain laudable, more effort to stimulate higher yield potential and the stability of the major fruit crops are needed to feed a world population that is predicted to reach 8 billion by 2025 [13].

The propagation of many fruit crops has intrinsic challenges such as low germination rate, heterozygosity of seeds, and prolonged juvenile phase, which hamper efficient and rapid growth [17]. Together with the changing climate, biotic and abiotic stresses can significantly influence productivity in major fruit crops [18,19,20,21,22,23]. In recent times, different strategies including genetic modification [19,24,25,26], encapsulation technology [20], photo-biotechnology [27], and the manipulation of phytohormone balances with compounds such as nitric oxide (NO) [28] and 1-methylcyclopropene (1-MCP) [29] have been explored to mitigate biotic and abiotic stresses. Furthermore, the systematic application of biostimulants, particularly plant growth-promoting rhizobacteria (PGPR) and mycorrhizal fungi have been demonstrated to hold the potential to mitigate biotic and abiotic stresses as well as boost fruit crop production [18,30]. In addition to these approaches, the diverse roles of PGRs, especially CKs, offer a potential avenue that requires more detailed attention [31,32,33,34,35,36]. As an example, Zalabák et al. [22] postulated that the genetic engineering of CK metabolism may offer greater potential to improve the agricultural traits of crops. In response to environmental cues, physiological and genome-wide microarray studies indicate an existing relationship with CK levels in planta [32]. In addition to increasing evidence of CKs’ influence in alleviating biotic and abiotic stresses, CKs play an important role in horticultural crop production where their application influences the morphological structure and nutrient content, as well as facilitates harvesting and the overall yield in a number of fruit crops [14,37]. Thus, in this review, we highlight and critically explore the potential of CKs in the propagation, growth, and general physiology with specific reference to some fruit crops. In the past three decades, the advent of molecular biology, genetic engineering, and exploitation of mutant technologies in various model plant species has led to a better understanding of the molecular mechanisms of CKs. Major breakthroughs in the 1990s led to the discovery of the CK signaling circuit networks that partly explain the diverse roles of CKs throughout a plant’s life cycle in molecular, cellular, and developmental contexts. Some of this research, mainly conducted in the non-horticultural Arabidopsis species (Arabidopsis thaliana) as a model, has been comprehensively reviewed in the works of:

- (a)

- Kakimoto [38], describing the perception and signal transduction mechanisms involving CK receptors in plants based on the molecular work conducted in the 1990s;

- (b)

- Hwang et al. [39], where CK–auxin relationships controlling early embryogenesis and organ differentiation and development are explained. The authors highlighted studies conducted in Lotus japonicus and Medicago truncatula that have led to the acknowledgement of the importance of CKs in nodule formation. Furthermore, the impacts of CK circuits in biotic and abiotic stress responses and regulation of senescence by CKs were critically described;

- (c)

- Steklov et al. [40], who compared the structural configuration of CK receptors and their phylogenetic relatedness across species including horticultural crops such as orange, apple, tomato, and grape.

This paper is not a comprehensive review of the mechanisms of CK in plants; nonetheless, we briefly describe the available current information and new insights into the molecular mechanisms and modes of action of CKs with particular reference to horticultural fruit crops. The paper details the impacts of CK application in pre and postharvest management practices of horticultural fruit crops. Based on existing data, we identify gaps in knowledge and recommend potential ways to explore the value of CKs in horticultural fruit crops. Finally, we highlight the possibilities in exploring horticultural fruit crops as new models to provide a better understanding of the broader functioning of CKs and their regulatory control in horticultural fruit crops. Tomato, a prominent model organism for scientific studies, is excluded due to the extensive existing literature focusing on different aspects of the plant [15,27,41,42,43].

2. An Overview of the Mode of Action of Cytokinins in Plants

The functions of CKs in plants involve complex coordination through a diverse network of cross-talk mechanisms that results in the regulation of numerous physiological processes, namely, axillary shoot branching, the release of apical dominance, root meristematic cell patterning, and the production of lateral roots [14]. More often, the processes that are mutually controlled by CKs and other PGRs are defined scientifically as being antagonistic or agonistic. However, this viewpoint is regarded as being overly simplistic. For example, Schaller et al. [44] emphasized the importance of revisiting these definitions. Our current understanding of the relationship of these PGRs lends itself to their roles in plants being redefined so that they are more reflective of their actual actions. Thus, it may be best to define their roles as being ‘complementary and dynamic’ as PGRs function synergistically, antagonistically, or additively to bring a desired result. For example, CKs together with auxins are important for stem cell differentiation and the activities of CKs and auxins at both the shoot apical meristem (SAM) and root apical meristem (RAM) regions, and their cross-talk interplay are excellently described by Schaller et al. [44].

2.1. Metabolic Regulation of Cytokinin Activity

The metabolic production and control (biosynthesis, inter-conversions, and degradation) of CK homeostasis involve a wide range of enzymes [12,45]. Particularly, isopentenyltransferase (IPT) is an important enzyme involved in the first and rate-limiting step in CK biosynthesis that entails the transfer of an isoprenoid moiety to the N6 position of the adenine nucleotide [22,45]. An additional enzyme involved in the modification of CKs at the adenine part of the molecule was discovered in 2007. Evidence from the study by Kurakawa et al. [46] revealed the existence of a specific phosphoribohydrolase (designated as Lonely Guy; LOG) in rice. The LOG enzyme is responsible for the cleavage of ribose 5’-monophosphate from the CK nucleotides to form biologically active CK-free bases in one enzymatic step [22]. On the other hand, cytokinin oxidase/dehydrogenase (CKX) is central to the catabolism of CKs, where an irreversible cleavage of the CKs occurs, and the presence of auxins positively regulates this enzyme. Cytokinin oxidase/dehydrogenase is under a positive auxin regulation, leading to the regulated synthesis of CKs in plants and associated responses. The CK biosynthetic genes belong to a gene family that is developmentally and spatially regulated in its expression in plant cells [12,22].

Glucosyltransferases and xylosyl transferases catalyze O-glucosylation, N-glucosylation, and O-xylosylation events, leading to the production of various CK conjugates whose full function remains to be completely characterized [47,48]. For instance, a recent evidence revealed the metabolic reactivation of trans-zeatin (tZ) N-glucosides (N7 and N9 positions) in Arabidopsis thaliana, which is contrary to the previously-held hypothesis that N-glucosylation irreversibly inactivates CKs [45]. Many of these enzymes involved in CK metabolism were discovered mainly in the 1990s through to the 2000s. The uridine diphosphate glycosyltransferases (UGTs) are now known to deactivate CKs such that the regulation of CKs in plants is precise during distinct developmental phases and in response to environmental conditions throughout the plant’s life [49]. Environmental factors, both abiotic and biotic, as well as endogenous inputs, tightly regulate the synthesis and degradation of CKs, generally, in plants [50].

2.2. Molecular Aspect of Cytokinin Actions

Molecular genetic approaches have been useful in unravelling the major sensing and signaling roles linked to CKs [12]. The CK receptors are of a histidine kinase (HK) nature with autophosphorylation events being important as part of the signaling transduction pathways that ultimately lead to the negative and positive induction of CK-controlled gene expression [39]. The CK signal pathway in plants uses a basic phosphorelay two-component system (firstly described in bacteria) which revolves around four sequential phosphorylation steps that alternate between histidine and aspartate residues, where a conserved CK-binding domain, Cyclases/Histidine kinases Associated Sensory Extracellular (CHASE), has an extracytosolic location [39]. The HK receptors are localized on endoplasmic reticulum (ER) membrane, and the CHASE domain lies in the direction of the ER, leading to the hypothesis that the in planta binding of CKs is in the lumen of the ER [47]. These CK receptors are part of a large family of transmembrane HK sensors with three main evolutionary branches in plants, which is evident through the application of various bioinformatics tools [40]. The cytokinin response factor (CRF) gene families are known to control cotyledon and leaf development. Although the CRF genes, belonging to the family of AP2/ERF transcription factors, were first characterized in Arabidopsis, they are found in all land plants [51]. The tomato-specific CRFs, termed SICRF genes, responds to CKs by controlling the development of leaf primordial and root tips, and they occur as two distinct clades [52]. The review by Cortleven et al. [53] highlights the importance of CK mutants in uncovering the signaling mechanisms and biosynthesis steps involved in the in planta production of natural CKs. For example, LOG enzymes catalyse the reaction steps that increase the metabolic pool of CKs such as isopentenyladenine (iP) and tZ in plant tissues [10,12]. The nuclear-localized type B response regulators (RRB or type B ARR) are transcription factors of the CK signaling pathway that CK targeted for gene expression [12,53]. Through a negative feedback loop, the other regulators, type A RRs (RRA), indirectly control the induction of the CK-responsive genes that are in fact targets of the type B RRBs [53].

As a result of the benefits associated with transgenic or genome engineering, desired traits can be manipulated in different horticultural fruit crops (Table 1), and this has largely been spurred on by accumulating new information on the molecular biological effects of CKs in plants. For instance, genes related to specific CKs such as CPPU (N-(2-chloro-4-pyridyl)-N´-phenylurea) and BA (N6-benzyladenine) were recently identified in horticultural fruits. Following the treatment of pear fruitlet with 30 mg/L CPPU, the B-PpRR genes potentially influenced fruit development, bud dormancy, and light/hormone-induced anthocyanin accumulation [54]. The study by Ni et al. [54] indicated that CKs have the potential to stimulate the accumulation of anthocyanin in pear. Similarly, the upregulated expression of the LDOX gene contributed to the induction of anthocyanin content in strawberry treated with varying concentrations of CPPU [55]. Apart from the impact of CKs on specialized (secondary) metabolites [54,55], central (primary) metabolites, especially the carbohydrate content in fruits, may be indirectly influenced by CKs, as shown in kiwifruit [56] and strawberry [55]. Dipping application of kiwifruits in 10 mg/L CPPU significantly influenced the soluble carbohydrate component of the fruit osmotic pressure [56]. In apple, evidence of the expression of different genes related to CK activities was shown during axillary bud development [57] and flowering [58,59]. The expression of these CK-related genes was postulated to be essential for the postharvest storage of horticultural fruits, including strawberry [55].

Table 1.

Gene expression-related responses to cytokinin application in different horticultural fruit crops.

Recently, genome editing in fruit crops by CRISPR/Cas9 has emerged as an alternative approach to mitigate time-consuming conventional breeding programmes [26,60,61]. Since the first studies in tomato and citrus-producing stable transgenic lines, the CRISPR/Cas9 technology has been applied to an increasing list of fruit crops including kiwifruit, banana, strawberry, papaya, and ground berry [62]. Genome-wide expression analysis data are largely lacking for many aspects linked to the developmental biology of fruit crops. Available information is mainly for the fruit biology of horticultural crops and genes linked to defense responses but not necessarily linked to CK responsiveness [51]. Despite increasing efforts, the molecular mechanisms underlying the role of CKs in pre- and postharvest quality performance of horticultural fruits are yet to be fully elucidated, and such information may be critical for the utilisation of modern technologies for fruit crop improvement.

3. Effects of Cytokinins in Different Phases of Horticultural Fruit Crops

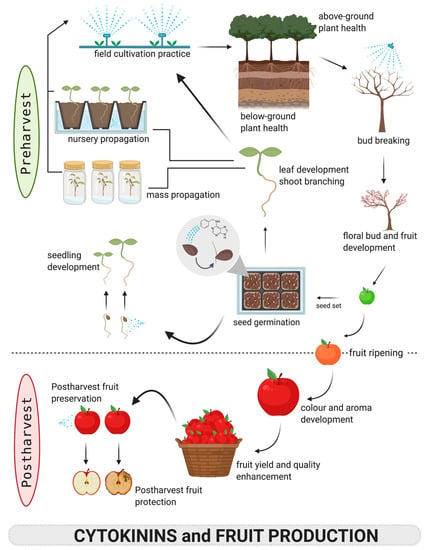

The multifaceted functions of CKs in plants have led to their applications in commercial horticulture, notably micropropagation (Table 2 and Table 3). In addition, the potential of CKs as a viable tool for the manipulation of critical aspects of plant growth and development such as fruit size and quality for maintaining quality aspects of agricultural produce has become more apparent, and this intermediary phase brings the produce in closer connection to markets and consumers. To demonstrate the importance of CKs in horticultural fruit crops, their diverse roles in plant growth and development are discussed in detail in the subsequent sections and summarized in Figure 2.

Table 2.

Cytokinin applications for in vitro propagation protocols of horticultural fruit crops.

Table 3.

Cytokinin applications in mass propagation of major horticultural fruit species through somatic embryogenesis.

Figure 2.

An overview of cytokinin applications in the production of horticultural fruits using apple as an example.

3.1. Micropropagation Phase

Micropropagation remains a fundamental biotechnology approach that is capable of producing clonal propagules, which are pathogen- and disease-free due to the aseptic nature of the technology, within the shortest possible time. Plant propagation using tissue culture technology has become a routine and sometimes the sole-practical procedure for the production of high-quality clones, including fruit trees, in commercial horticultural systems [17,74,75]. A highly efficient plant regeneration protocol is often a prerequisite regardless of the type of biotechnological approach used for the improvement of the fruit crops. Pioneer studies in in vitro plant manipulation demonstrated the importance of CKs as well as their interactions with auxins on morphogenesis [44], which has led to a multitude of tissue culture-based regeneration regimes in fruit species of economic value.

3.1.1. Mass Propagation of Horticultural Fruit Crops

Efforts to mass propagate different horticultural fruit species have been actively pursued globally (Table 2 and Table 3). For instance, in apple, extensive research has been conducted to standardize tissue culture protocols with significant emphasis on the type of CK [75,76]. Researchers have recognized the importance of CKs in clonal propagation to supply uniform propagules to the growing horticultural fruit industry. Over the past few decades, there has been significant progress and advances in the use of CKs for the clonal mass propagation of elite genotypes of horticultural fruit trees via organogenesis and somatic embryogenesis in both commercial and research laboratories. The importance and impact of CKs in micropropagation have been widely reported and are well-entrenched in the field of horticulture [77]. It is also highly relevant to reduce the relatively long juvenile phase associated with perennial fruit tree species. Somatic embryogenesis has emerged as a better alternative to organogenesis in the mass propagation of some fruit trees, due to the in vitro recalcitrance of explants from mature phase selections [78,79,80,81,82,83]. However, irrespective of the propagation method, CKs are often the main determinants of successful plant regeneration.

3.1.2. Influence of Cytokinins in Micropropagation of Horticultural Fruit Crops

There are numerous reports on the optimization of CK types and concentrations in organogenesis and somatic embryogenesis protocols for many horticultural species, including the commercially cultivated fruits such as Citrus spp., Malus spp., Litchi chinensis, Psidium guajava, Musa spp., Passoflora edulis, Punica granatum, Vitis vinifera, and Carica papaya ( Table 2 and Table 3). Aspects of mass propagation in important horticultural fruit crops using organogenesis and/or somatic embryogenesis have been summarised in excellent plant-specific reviews for Psidium guajava [80,82], Punica grantum [81,155,156], and Malus spp. [75]. Various explants such as petioles, leaves, shoot meristems, seeds, cotyledons, anthers, filaments, pistils, nucellar, endosperms, inner integuments, and protoplasts can be used for the induction of somatic embryos. However, immature zygotic embryos represent the most desired source of embryogenic cells in most established somatic embryogenesis protocols—for example, in Citrus spp., Litchi chinensis, Musa spp., Persea americana, and Psidium gujava (Table 2). The effectiveness of immature zygotic embryos for the in vitro mass propagation of many recalcitrant fruit trees is dependent on the presence of pre-embryogenic determined cells, which have high embryogenic competence and can be easily induced into embryogenic masses by combinations of CKs, auxins (mainly 2,4-D and picloram), and other PGRs, including gibberellin (GA₃) [80]. The influence of CKs in plant propagation via somatic embryogenesis was reported in several fruit species, notably Citrus spp. [78,93,157], Psidium guajava [158,159,160], Prunus spp. [161,162], and Vitis spp. [163]. Furthermore, efficient plant regeneration has become an integral component of molecular genetic techniques of plant improvement, which form the mainstay in the production of transgenic plants [74].

Besides the vital factors such as type of explant, the season of explants’ collection, endogenous CK concentration, as well as the age and genotype of the stock plant, the success of any plant propagation system using plant tissue culture rests almost exclusively on the applied PGRs, especially the type and concentration of CK. The response of different horticultural plants to CK type and concentration is as widely varied as the plant species themselves (Table 2 and Table 3). Benzyladenine is unrivalled as the main CK used in the micropropagation of horticultural fruits crops through both organogenesis and somatic embryogenesis. In mass propagation through organogenesis, other commonly used CKs include KIN, zeatin, zeatin riboside (ZR), N⁶-(2-isopentyl) adenine, N-(2-chloro-4-pyridyl)-N-phenylurea, thidiazuron (TDZ), and most recently, the meta-topolins (Table 2). On the other hand, TDZ and KIN are the predominant alternatives to BA for somatic embryo induction, maturation, and plant recovery in most fruit trees of economic importance (Table 2). By and large, BA together with 2,4-D [164] remain the most commonly used synergistic CK–auxin combination in the plant propagation of important fruit tree species such as banana, apple, grapes, litchi, sweet orange, passion fruit, avocado, and guava through somatic embryogenesis (Table 2). Moreover, plant recovery stages depend primarily on a CK–GA₃ combination [135,139,145,146,147]. However, despite early promising results of N6-(3-hydroxybenzyl) adenine (meta-topolin, mT) as a possible alternative to BA in plant tissue culture [165,166] and its subsequent application in the organogenesis of numerous plant species [167], there is a dearth of information on the use of meta-topolins in the somatic embryogenesis of fruit crops. This paucity of knowledge presents an interesting area of research in the bid to increase the efficiency and effectiveness of CKs in somatic embryo induction, maturation, germination, and plant recovery.

The main drawbacks of exogenously applied BA in the micropropagation of horticultural fruit trees include the induction of somaclonal variation, hyperhydricity, shoot-tip necrosis, rooting inhibition, and low ex-vitro acclimatization [167], which are physiological disorders that can detrimentally compromise the quality of fruit tree propagules. Compared to BA, the topolin family of CKs has been shown to minimize the effects of in vitro-induced hyperhydricity in some fruit crops such as bananas [109] and apple [102]. However, to the best of our knowledge, there are no reports on the alleviation of somaclonal variation based on CK type. Somaclonal variation can lead to changes in both nuclear and cytoplasmic genomes, which can be genetic or epigenetic [78]. Both BA and meta-topolins produced somaclonal variants in Fragaria x ananassa [97] and Musa spp. [109], respectively, for which clonal propagation was the desired outcome. On the other hand, the induction of somaclonal variation may be advantageous and holds great promise in tree cultivar improvement, for example in citrus breeding, due to its recalcitrance to sexual hybridization [78]. Notwithstanding, a thorough understanding of the molecular mechanisms remains critical in the development of fool-proof and efficient mass propagation systems using either organogenesis or somatic embryogenesis models.

Generally, the ‘trial and error’ approach remains the predominant method in the optimization of micropropagation systems of different plant species and sometimes genotypes within a species, which is partly due to the inherent physiological variations in plants. Thus, the main thrust in tissue culture research for the mass propagation of horticultural fruit crops has largely explored and defined the plant-specific threshold limits of different CKs in shoot proliferation and growth (Table 2 and Table 3). In this regard, CKs have been used to achieve several organogenic end points, primarily shoot induction and proliferation, somatic embryo induction, maturation, and subsequent plant recovery. However, as with the first successful establishment of the breakthrough in vitro tomato root culture by White [168], micropropagation requires an equally revolutionary paradigm shift from the predominant ‘trial and error’ approach.

An alternative approach was demonstrated by Werbrouck et al. [165], followed by Bairu et al. [169] and some other related studies [170], where the analysis of endogenous CK metabolites was successfully used to emphasize the differences in BA and mT metabolism and correlate these differences with basic micropropagation parameters. It has been repeatedly shown that such an approach can accelerate the entire optimization process of in vitro micropropagation and subsequently even lead to the development of new active PGRs [171]. However, such an approach is still extremely rare in the case of horticultural fruit crops [86].

Although tissue culture as a means of propagation has been extensively studied in several fruit crops (Table 2 and Table 3), it is only recently that the molecular mechanisms associated with shoot organogenesis and development have been compared to processes occurring during natural plant morphogenesis [172]. Research in this area usually investigates how in vitro shoot production occurs from callus, and few studies have compared organogenic molecular pathways where a direct route to shoot regeneration is primary [172]. Processes linked to the molecular controls of CKs in somatic embryogenesis are even more poorly understood as different species, cultivars, and genotypes with varying physiological and genetic backgrounds have been used to study this process [173]. For a long time, callus was referred to as a de-differentiated mass of highly totipotent cells. However, nowadays, there is consensus to accept callus, irrespective of its origin (either derived from root, leaf, or hypocotyl), as resembling a root primordium that is under the forces of auxin-CK cross-talk [172].

This is of particular relevance when a two-step organogenesis protocol is established and where an auxin-supplemented medium is used to initiate callus proliferation prior to shoot induction through the transfer of the callus to a medium rich in CK(s). The transcriptomic profiling of Arabidopsis callus tissue revealed the presence of important genes involved in CK signaling, suggesting the intrinsic readiness of the tissue for shoot regeneration even at early stages of callus induction from explants [173]. Although two genes (CKX5 and CKX3) involved in CK degradation were upregulated, no significant changes were observed with other CK signaling-related genes during the incubation. Primordia with the potential for organogenesis are set up at the callus phase, although genes such as WUSCHEL (WUS) that function in shoot apical meristem patterning and development may not occur at early stages of callus proliferation [174]. Cell fate mediated by a high CK-rich medium is not well-understood, but purine permeates (PUP, e.g., PUP1 and PUP2) may be expressed, and these are linked to the transport of CKs [172]. The over-expression of IPTs can overcome the need to add CKs to plantlet growth medium, and those mutants that have a loss of function for IPT invariably show a significantly decreased capacity for shoot proliferation, but this growth impairment may be overcome when CKs are applied exogenously [175].

3.2. General Growth and Health of Fruit Crops/Trees

The architecture and structures of fruit trees influence the resultant crop efficiency and productivity, which is a foremost selection criterion for fruit breeders [176]. Lateral branch development has been reported to be beneficial for increasing the bearing surface and in promoting the early production in horticultural fruits such as apple and the sweet cherry tree [37,177,178,179,180]. Different approaches are often devised to manipulate the structure of a fruit tree for improved performance and productivity [178,179,181]. The application of CKs can improve branching in young trees in nurseries, providing the opportunity to obtain good tree architecture in the future [14,37]. For instance, BA (100 mg/L) effectively stimulated the lateral branching in young apple trees [182].

Similarly, Çağlar and Ilgin [179] observed a significant increase in the total number and total length of laterals per apple tree, following 2–3 applications of BA (200 mg/L). Furthermore, BA treatments also increased the diameter of laterals compared with the control. The effectiveness of combining CKs with other PGRs, especially GA, has been explored by researchers [177,183]. As demonstrated by Zhalnerchyk et al. [180], Neo Arbolin and Neo Arbolin Extra (commercial branching products consisting of BA and GA) stimulated varying degrees of branching in three apple cultivars. Four variants of Arbolin, with differing compositions of BA and GA, effectively promoted laterals in difficult-to-branch apple cultivars [183]. Likewise, various concentrations of Arbolin increased the number of lateral branching in two cultivars of sweet cherry trees [177].

Major abiotic conditions such as drought, extreme temperature, and salinity are factors limiting crop productivity and food security globally [184,185]. Cytokinins, either produced through the alteration of endogenous CK biosynthesis or exogenous application, have been reported as critical phytohormone signals during different abiotic stresses in many plants [22,184,186,187], including apple trees [188]. Some of the adaptive mechanisms induced by IPT-transgenic crop plants include improved rooting characteristics (such as increases in total root biomass, root length and root/shoot ratio), which enhance water uptake from drying soils [22,189]. These observations strongly suggest a key role of CKs in controlling root development, differentiation, and architecture in horticultural fruit trees [189]. Although the mechanisms are not that well resolved, Macková et al. [190] reported the overexpression of CKX1 using the root-specific WRKY6 promoter that stimulated strong root growth coupled to a concomitant reduction of the stunting effect of the shoot system. This strategy also induced a significant increase in drought tolerance in the overexpressing lines. A major contributing factor to the improved drought tolerance of WRKY6: CKX1 transgenic plants could be linked to the more extensive root system and higher root-to-shoot ratio. For example, transcriptomic analysis of tomato [51] led to a discovery of several new genes including xanthine/uracil permease family protein and a cytochrome P450 with abscisic acid 8′-hydroxylase activity, whose expression is highly dependent on CK induction that is involved in leaf development. It is now apparent that the CRF genes are implicated in stress responses controlled by CKs and in tomato, organ-specific responses were linked to the strong expression of the SICRF1 and SICRF2 genes by cold stress in shoots and oxidative stress in the roots [52]. Thus, there are unique opportunities to exploit such technologies to create plant varieties with novel traits; however, we note the scarcity of information on similar molecular studies in horticultural plants of economic importance.

3.3. Preharvest Phase

As applicable with the commonly utilized PGRs in horticulture, frequently CKs are directly applied during the preharvest phase for diverse purposes such as improved morphological structure, facilitation of harvesting, quantitative and qualitative increases in yield, as well as the modification of nutritive chemicals [11,37,191,192]. Particularly, the need to mitigate preharvest fruit drop, promote vegetative growth, enhance flower bud formation, and control the process of fruit ripening is of considerable importance from a commercial perspective [193]. Manipulating fruit yield and quality requires an understanding of the fundamental processes that determine fruit set, maturation, and ripening [15]. Generally, a wide range of desirable characteristics such as nutritional value, flavor, processing qualities, and shelf life determine the overall fruit quality (Figure 2).

3.3.1. Floral and Fruit Development Following Cytokinin Application during Preharvest Phase

There is increasing evidence of the importance of CKs in reproductive biology, which is gained mainly from studies based on model plants, including thale cress (Arabidopsis thaliana) and rice (Oryza sativa). More often, intracellular CK content is correlated to the increased onset of inflorescence and floral meristem production [194,195], and this supports the idea of applying CKs to enhance fruit production. Flowering, fruit development, and ripening are complex biological processes known to depend on highly coordinated phytohormonal activities and homeostasis in plants [196,197,198]. The desirability of fruit is largely dependent on the final stages of fruit development that involve physiological, biochemical, and, physical–structural changes.

It is now well-established that seed and fruit development are intimately synchronized processes, due to the biosynthesis of different PGRs in seed tissues [7]. Fruit set, which involves the transition of the quiescent ovary into developing fruit, is regulated by cross-talk among the phytohormones and is probably the most critical step in fruit production [197]. Fruit set can occur following successful pollination and fertilization or via parthenocarpy, which produces seedless fruits without fertilization [199,200]. On the other hand, parthenocarpy as a desirable characteristic in fruit production occurs naturally in several important fruit species, notably banana, grape, pineapple, citrus fruits, and apple [7,201]. Phytohormones including CKs, GA, and auxins regulate the natural developmental mechanism of parthenocarpy in different fruits.

Observations in fruit crops such as strawberry (Fragaria ananassa), kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa), raspberry (Rubus idaeus), and grape (Vitis vinifera) where CK-associated activities or amounts increase internally in immature seeds and developing fruits suggest the significant ontogenic role that CKs play in floral and fruit development [202]. Although the concentration of CKs significantly increases after fertilization and during early stages of fruit development, little is known about their effects during the later stages of fruit ontogeny. Thus, the role of CKs on biochemical and molecular responses during this phase is unclear. Currently, there is no generic scientific evidence to explain the effects of CKs in the ripening phases, as results from exogenous applications of CKs to different species and cultivars lead to inconsistent physiological responses, suggesting that the effects may likely be species or cultivar-specific [202]. Nevertheless, the spatial and temporal specificity of CK biosynthetic genes (particularly IPTs and CKXs) and those involved in the activation, perception, and signaling associated with intracellular CK-regulated mechanisms are apparent in maturing grapevines [203].

Cytokinins often induce fruit enlargement through cell division and/or cell expansion [14]. The effect of CPPU and mT (used at 100 mg/L) in improving the fruit weight of sweet cherry ‘Bing’, which was recorded as a 15% increase, was attributed to enhanced cell division rather than stimulating fruit expansion [204]. Conversely, in kiwifruit (Actinidia deliciosa), cell expansion rather than cell division was mainly responsible for the increase in fruit size, as evidenced by a 30% decrease in the number of cells. However, researchers found 89% higher cell diameter in CPPU-treated fruits compared to control fruits [196]. Generally, varying responses in fruit development have been observed when CKs are exogenously applied in a range of fruit crops (Table 4). For example, in pear, 100 mg/L BA substantially improved fruit size without any adverse effect on the yield and fruit shape [205]. In pear, responses to BA application were strictly cultivar-dependent, as the preharvest BA application significantly increased the fruit size of ‘Spadona’ cultivar, while substantial fruit thinning was observed in ‘Coscia’ pear [206]. Apart from the numerous examples with the effects of BA [37], the effectiveness of CPPU, TDZ, and mT application (in a limited number of studies) have also been evaluated in many fruit crops such as blueberry, kiwifruit, sweet cherry, grape, and apple (Table 4). In the majority of the examples, the application of CPPU facilitated fruit enlargement. The fruit size and mass were significantly higher in CPPU-treated blueberry (Vaccinium corymbosum) when compared to the untreated control [207]. Likewise, the application of BA (100 mg/L) substantially improved the fruit size of ‘Akca’ pear [205].

Table 4.

Fruit attribute responses following preharvest cytokinin application in horticultural fruit crops.

The combination of CKs with other PGRs such as GA, auxins, and abscisic acid (ABA) have been explored in different fruit crops (Table 4). The most common combination involves BA and GA(3, 4, 7), which is also the constituent of some commercial products, including promalin and cytolin [37]. Fujisawa et al. [207] observed that combining CPPU and GA led to greater fruit size and mass compared to the control or single applications of CPPU and GA. Likewise, a single application of CPPU increased berry size in seedless table grapes (Vitis vinifera) ‘Sultanina’, but the most significant effect was observed when CPPU was combined with GA3 [208]. These examples above clearly suggest a synergistic influence of the cross-talk among phytohormones.

Nevertheless, the combination of CKs with other PGRs may not confer any additional benefit for floral and fruit development. In apple ‘Fuji’, BA and ABA caused a thinning effect individually, but when combined, ABA provided little or no additional thinning [209]. Seedless table grape cultivars did not show any beneficial or synergistic developmental effects when CPPU was used alone, but when combined with GA, this exposed the undesirable tendency for CPPU to delay fruit maturity [210]. The application of CPPU and GA4+7 conferred no additional benefit in the fruit size of the cultivar, apple ‘Fuji’ [211]. The effects of CKs and other phytohormones on fruit set, development, and ripening are not necessarily generic even for cultivars within the same species, illustrating the magnitude of yet unknown intricate mechanisms regulating these processes. Perhaps, there is an association between the level of endogenous CK and fruit development. Seed-bearing avocado (Persea americana) fruits were 10-fold larger than seedless fruits under natural growing conditions [212]. The observation was strongly linked to a positive correlation between the rate of fruit growth and the level of endogenous CK in seed tissues [213].

3.3.2. Physical Changes and Yield Responses Following Cytokinin Application during Preharvest Phase

Physical appearance traits such as size and shape are strongly associated with consumer preference, which may strongly influence the economic value of horticultural fruits [61,193,246,247]. As shown in Table 4, different CKs including CPPU, BA, and TDZ have demonstrated their ability to enhance the attributes of resultant fruits in terms of their color, number, and size as well as the length to diameter (L/D) ratio. In most stone fruits, fruit firmness also indicates maturity and quality [247,248]. The flesh firmness of CPPU-treated apple (‘McIntosh’/M.7) had a linear positive response to varying concentrations (1–8 mg/L) of CPPU [227]. In apple ‘Fuji’, Matsumoto et al. [211] demonstrated the effectiveness of 10 mg/L CPPU in the enhancement of flesh firmness when applied 4 days after full bloom (DAFB). Even though TDZ successfully increased the flesh firmness when applied at full bloom (FB), a reduction in flesh firmness was observed when TDZ was applied late, after the FB period in apple [226]. The treatment with 20 mg/L CPPU (applied at marble and pea stages) increased fruit length and diameter as well as fruit weight in mango [231]. Other CKs, including TDZ and BA have also been effective in the L/D ratio in many apple cultivars [209,226]. A positive effect on the L/D ratio was evident when CPPU was combined with other PGRs such as GA3 and ABA in table grapes [208,243].

The potential of different CKs such as BA and CPPU on the yield of horticultural fruit crops has been explored by different researchers (Table 4). Stern and Flaishman [206] investigated the effect of BA on the return yield of pear cultivars ‘Spadona’ and ’Coscia’. In ‘Spadona’ fruits, findings indicated that the total increase in yield of large fruit (≥55 mm in diameter) was 88% with 40 mg/L BA (7.5 tonnes/ha versus 4 tonnes/ha in control), while a total increase of 205% in the yield of large fruit (12.2 tonnes/ha) was obtained with 20 mg/L BA. Unlike ‘Spadona’, BA caused significant ‘Coscia’ fruit thinning of about 35% (444 and 765 fruits/tree in BA and control treatments, respectively), which reduced the total yield from 45 to 32 tonnes/ha. As reported by Kulkarni et al. [231], the spray application of mango with CPPU (10 mg/L) at two different stages resulted in the production of 107 kg/tree (10.7 tonnes/ha). This quantity was approximately two-fold higher when compared to the control. In different cultivars of table grapes, the cluster mass increased markedly (64–76%) at varying concentrations of CPPU [240]. Some of the cultivars also demonstrated significantly higher cluster compactness following CPPU treatment. In the study by Williamson and NeSmith [239], differential responses in yield were observed in different cultivars of highbush blueberries when treated with varying concentrations of CPPU. For instance, there was no significant increase in yield for ‘Sharpblue’ and ‘Santa Fe’ (regardless of the concentrations), while 5 mg/L CPPU led to remarkably higher yields of the ‘Star’ cultivar. A similar cultivar-dependent response in yields was observed in two cultivars of blueberries following the application of varying concentrations of CPPU at different time intervals [238]. While CPPU significantly influenced the yield in ‘Climax’ irrespective of the day of application leading to better yields, an early application of CPPU caused a reduced yield production of the ‘Brightwell’ cultivar. When there is no congruence on the influence of CK-related treatments in terms of yield promotion, it is thus important to test their effects on each cultivated variety.

3.3.3. Biochemical and Physiological Changes Following Cytokinin Application during Preharvest Phase

Even though the quality of fruit is often visually defined by the phenotypic characteristics such as fruit size, firmness, and weight, the associated biochemical and physiological changes are fundamentally important during the developmental stages [247]. Several studies have reported a major trade-off between some desirable phenotypic characteristics and fruit quality [196,214,242,243,249]. Fruit ripening is associated with changes in different biochemical and physiological parameters [250], often resulting in the conversion of less appetising green fruits into highly palatable, aromatic, colored, and nutritionally rich fruits [198]. Examples of the biochemical parameters that determine fruit quality include primary metabolites, such as sugars and amino acids as well as secondary metabolites, notably organic acids and anthocyanins, which contribute to fruit flavor. The application of CPPU may lead to a reduction in total soluble solids (TSS) and a concomitant increase in total titratable acidity (TTA), as shown in some fruits such as apple, blueberry, and grapes (Table 5). In mango, the application of varying CPPU concentrations (10 and 20 mg/L) had no significant effects on the TSS, total sugars, reducing sugars, non-reducing sugars, and acidity [231].

Table 5.

Biochemical and physiological responses in horticultural fruits following preharvest cytokinin application.

The observed variations in patterns of accumulation of sugars and organic acids in parthenocarpic fruits treated with exogenous CKs may be due to differences in cross-talk dynamics between metabolite signaling and phytohormones [249,251]. In addition, different types of soluble sugars can be either upregulated or downregulated in CPPU-treated fruit trees. For example, whereas the concentrations of sucrose, glucose, and fructose decreased during fruit ripening in CPPU-treated kiwifruits, the level of xylose was significantly increased [196]. Such observations illustrate the complex interactions of CKs with other PGRs and signaling molecules that control the growth and development dynamics of horticultural fruit crops.

3.4. Postharvest Phase

The postharvest phase is very critical in the production of fruit. Significant postharvest losses are generally incurred at this particular phase due to the perishable nature of fruit crops after harvest. The relevance of CKs during fruit ripening and senescence in planta and as a postharvest application, to perverse quality and extend the shelf life of various fruit crops, are summarized in Table 6 and Table 7.

Table 6.

Effects of preharvest application of cytokinins on postharvest quality of horticultural fruits.

Table 7.

Effects of postharvest application of cytokinins on postharvest quality of horticultural fruits.

3.4.1. Effect of Cytokinin Application in Fruit Ripening and Senescence

Effect of Cytokinin Application on Fruit Ripening

The biology of fruit ripening is highly complex and tightly regulated with different changes occurring to the ripening fruit, but one of the main changes associated with ripening is linked to colour (Figure 2). In most cases, this involves a loss of green colour and higher accumulation of non-photosynthetic pigments in climacteric and non-climacteric fruits, as influenced by their respiratory activity, which is often associated with ethylene biosynthesis profiles [253,254].

Other changes include firmness (softening by cell wall degrading activities and alterations in cuticle properties), taste (sweetening of the fruit as sugar levels rise and a decline tartness as organic acids lower), and flavor (associated with the production of volatile compounds providing a characteristic aroma) [242,253]. These activities accelerate ripening and senescence processes, which limit the shelf life of fruits [255]. A significant number of studies has demonstrated that exogenous CKs are effective ripening or senescence-inhibition plant regulators [256,257]. Their application can effectively delay senescence and improve the quality of chlorophyll-containing fruits by inhibiting chlorophyll degradation [257,258]. For example, in litchi, the application of 0.1 g/L BA reduced the expression of chlorophyll degradation-related genes and inhibited the activities of chlorophyll degradation enzymes in chlorophyll-containing tissues, therefore extending the shelf life of litchi by 8 days [259]. A study by Itai et al. [260] showed that the preharvest application of CPPU (100 mg/L) retarded ripening due to delayed chlorophyll degradation and low sugar accumulation in persimmons. Although the preharvest application of CPPU (20 mg/L) resulted in higher glucose, fructose, and sucrose contents in kiwi fruit during 6 months of storage, treated fruits also had a higher starch content compared to the control (Table 6). This indicates an inhibition of starch degradation due to the conversion of starch to sugars, thus delaying ripening as supported by higher chlorophyll content [216]. The effect of 10 mg/L CPPU in delaying ripening was also evident in banana [261]. According to the authors, the postharvest application of CPPU suppressed fruit softening by affecting respiration and ethylene production rates. Together with this, the accumulation of soluble reducing sugars and the hue value, and the maximal chlorophyll fluorescence of banana during storage were all retarded. Postharvest application of BA at a varied concentration of 0, 1, 10, and 100 mg/L delayed the de-greening of calamondins in both light and dark conditions and extended shelf life by 9 days compared to the control [254]. The underlying physiological response was the inhibition of ethylene-induced change in fruit color, and the same effect was observed in cucumber [262].

The Effect of Cytokinin Application on Fruit Senescence

Senescence is a crucial aspect of the fruit life cycle and directly affects fruit quality and resistance to pathogens [256]. Reactive oxygen species (ROS) such as superoxide anion (O2•−), hydrogen peroxide (H2O2), hydroxyl radicals, and singlet oxygen are primary mediators of oxidative damage in plants and are involved in senescence [263]. Moreover, senescent fruits are more susceptible to postharvest decay, fungal pathogens, and diseases, leading to the rapid necrotization of the tissue during storage [252,256,263]. Zhang et al. [264] reported that a postharvest application of BA, at 500 mg/L, inhibited cell membrane deterioration and induced higher defense-related enzyme activities such as superoxide dismutase (SOD) and peroxidase (POD) in peaches. In addition, it also reduced malondialdehyde (MDA) content, which is responsible for lipid peroxidation and oxidative stress and prolonged shelf life by 16 days compared to the control. Similar observations were also reported by Zhang et al. [259], who demonstrated that a postharvest application of BA (0.1 g/L) reduced H2O2 accumulation, lipid peroxidation, and polyphenol oxidase (PPO) activity in litchi, resulting in an extended shelf life by 8 days compared to the control. The treatment evidently controlled pericarp browning, quality deterioration, decay, and senescence in litchi (Table 7).

3.4.2. Effect of Cytokinin Application in Enhancing Postharvest Fruit Quality Attributes

The decision for subsequent purchases of fruit is strongly dependent upon consumer satisfaction based on texture, flavor, and aroma, which are related to soluble solids content (SSC) (mainly sugars), titratable acidity (TA), volatile and non-volatile phytochemicals [265]. Cytokinins are known to preserve or enhance these quality attributes in some fruits (Figure 2).

Effect of Cytokinin Application on Fruit Texture

While a certain degree of softening is desirable in fruit, depending on species and cultivar, excessive softening results in postharvest decay or consumer rejection [270]. The postharvest application of CPPU (10 mg/L) significantly inhibited banana softening by delaying the climacteric peak, thereby delaying ripening and extending the postharvest storage life of the bananas by 6 days compared to controls [261,271]. Similarly, postharvest application of CPPU (10 mg/L) enhanced texture in kiwifruit stored at 0 °C and 95% relative humidity [196]. According to Ainalidou et al. [196], treated fruits had a 2-fold firmness compared to the control, and this extended storage life by 2 months. The authors attributed this to a delayed climacteric response involving respiration and ethylene production rates that were lowered by 2- and 5-fold, respectively, in the treated samples.

Apart from CPPU, BA is also popular for use as a postharvest application, and some of its effects are linked to its capacity to maintain fruit firmness and delayed cell wall degradation and softening in round summer squash and peaches, for example (Table 7). This effect could be attributed to the inhibition of polygalacturonase and pectin methylesterase activities involved in cell wall degradation and softening. There is a possibility of it indirectly promoting the production of cross-link pectic substances in the cell wall that maintain rigidification, thereby increasing the fruit firmness and shelf life by more than 16 days [241,254]. Although the direct mechanisms are still not well understood, further support for this idea is demonstrated in the study of Massolo et al. [257], where an indication of a substantial delay in cell wall dismantling was apparent, when BA (1 mM) was applied in summer squash. In that study, there was prolonged fruit firmness and shelf life for 25 days, and this was due to higher levels of tightly bound polyuronides, recorded at 45%, that led to significantly delayed water loss from the fruits. On the other hand, the controls showed an extreme decrease of firmness and an increase of water-soluble pectin during storage which accelerated cell wall degradation and softening, limiting the shelf life of fruits to 12 days (Table 7).

Although many studies test the effect of exogenous applications on fruits after harvesting, another strategy that has been on trial is the testing of the effectiveness of preharvest applications in quality keeping and postharvest management. It is interesting to note that a preharvest application of 5 mg/L CPPU (relative to untreated controls) significantly increased the shelf life and quality of Thompson seedless grapes by enhancing berry firmness and decreasing the percentage of unmarketable berries when the fruit was stored at ambient temperature for 7 days after harvest [241]. The retention of berry firmness resulting from the CPPU application was suggested to be due to an inhibition of ethylene biosynthesis that prevented a loss in fruit firmness and extending storability by 7 days compared to the control [241,264]. In support of this, preharvest CPPU application significantly reduced weight loss in Thompson seedless grapes [241] and cucumber [266] and the increased storability of fruits by 7 and 10 days, respectively (Table 6; Table 7).

Effect of Cytokinin Application on Fruit Soluble Solids Content (SSC) and Titratable Acidity (TA)

The commonly used index values for harvesting and sale of mature fruits are the levels of SSC and TA. Li et al. [55] reported that a preharvest application of CPPU (15 mg/L) effectively inhibited the accumulation of TSS and significantly delayed the degradation of TA in strawberry by about 2-fold compared to the control during storage, which was mainly due to delayed fruit maturity or ripening. Incidentally, there was a 6-day shelf-life extension due to the slow accumulation of SSC and TA in treated fruits. In comparison to treated fruits, the control had significantly higher TSS and lowered TA during storage due to an early attainment of maturity and ripening. Similarly, CPPU (10 mg/L) significantly inhibited the accumulation of sugars (fructose, sucrose, lactulose, tagatofuranose, tallose, and psicofuranose) in kiwifruit by up to 17-fold compared to the control, and it also extended fruit shelf life by 2 months at 0 °C and 95% relative humidity [196]. Sugars, including sucrose, glucose, and fructose, accumulate after starch degradation in fruits [271,272]. As high SSC and ethylene production rates become more pronounced in untreated kiwifruit compared to the treated ones, accelerated ripening and cell wall degradation become important indicators of a shortening of postharvest storage capacity in kiwifruit [196]. Other work that lends support to the application of CPPU as postharvest treatment is linked to the study of Huang et al. [261], who used 10 mg/L CPPU to effectively delay the accumulation of soluble reducing sugars in banana by more than 2-fold, and it also concomitantly extended the shelf life by 16 days due to delayed ripening and softening. By accumulating metabolites such as sugars and organic acids, plant cells produce a lower osmotic potential that generates a turgor pressure resulting in cell expansion, and this process also requires the cell wall to be irreversibly stretched through cell wall loosening [273]. Therefore, the application of CKs is an effective alternative for inhibiting the accumulation of sugars, ripening and prolonging the shelf life of fruits [196,226,261].

Effect of Cytokinin Application on Fruit Phytochemicals

The synthesis and accumulation of secondary metabolites in the developing, maturing, and ripening fruits are of critical considerations in terms of quality and acceptance by consumers [24,274]. Li et al. [55] reported that a preharvest or postharvest application of CPPU (10 or 15 mg/L) significantly decreased the total volatile content (esters, alcohols, acids, terpenes, furanones, and others) of strawberry by 65.3% and 87.7% compared to the control before and after storage, respectively, and it extended the fruit shelf life by 6 days. Similar observations were reported by Ainalidou et al. [196], who demonstrated that a preharvest application of CPPU (10 mg/L) resulted in the downregulation of fatty acid hydroperoxide lyase in kiwifruit, cleaving fatty acid hydroperoxides and forming short-chain (C6) aldehydes, which are the volatile primary constituents of the characteristic odor of fruits. According to the authors, this could be responsible for the inhibition of respiration and ethylene production rates, resulting in delayed ripening and an extension of shelf life by 2 months in treated fruits.

The application of CKs has also been reported to enhance phytochemical quality such as phenols, flavonoids, and antioxidant activity [258,275,276], thus maintaining the nutritional quality of fruits. For instance, the postharvest application of BA led to a significant 2-fold rise in phenylalanine ammonia lyase (PAL) activity compared to the control [259]. This enzyme has a key regulatory role in specialized metabolism, as it drives the first committed step of phenylpropanoid synthesis and thus controls the biosynthesis of secondary metabolites, including anthocyanins in plants [276,277]. The influence of BA in treated fruits is correlated to higher contents of anthocyanin, total phenolics, ascorbic acid, and total antioxidant capacity during storage compared to non-treated controls, and even higher levels of chlorophyll are apparent when this PGR is used after harvest (Table 7). Tsantili et al. [269] reported that the postharvest application of CKs induced anthocyanin formation but fortuitously did not raise ethylene concentrations or encourage the softening of olive fruits. Therefore, this demonstrates that the ability of BA treatment to induce PAL activity is favorable for the synthesis and maintenance of anthocyanin content during postharvest storage [259].

Effect of Cytokinin Application on Fruit Antioxidant Enzymes

The application of 10 mg/L CPPU significantly enhanced the upregulation of ꞵ-1,3-glucanase and lactoylglutathione lyase defense enzymes in kiwifruit by almost 3-fold compared to the control. This could be possibly responsible for the inhibition of cell wall degradation and softening in treated fruits, as well as an extension of shelf life by 2 months at 0 °C and 95% relative humidity [196]. The ꞵ-1,3-glucanase enzyme catalyzes the endo-type hydrolytic cleavage of ꞵ-1,3-D-glucosidic linkages in ꞵ-1,3-glucans involved in cell wall thickness [278]. In contrast, the lactoylglutathione lyase enzyme is implicated in CK-defense responses, as it primarily functions in the glyoxal pathways generating S-lactoylglutathione from toxic methylglyoxal, which increases intracellular levels of ROS [196]. Thus, higher levels of the expression of lactoylglutathione lyase induced by CKs are speculated to be crucial for fruit protection against oxidative stress [279,280], which could be responsible for the inhibition of ripening and senescence in treated fruits [196]. Thus, there is great merit in using CPPU (applied at 10 mg/L), because it controls antioxidant ROS mechanisms and effectively upregulates short-chain type dehydrogenase/reductase-like (SDR) and abscisic acid stress ripening-like proteins (ASR) in kiwifruit. These proteins, which were implicated in ethylene-controlled fruit ripening, were detected at higher levels by Ainalidou et al. (2016) using a gel-based proteome study, where kiwifruit shelf longevity was increased to 2 months in CPPU-treated kiwifruit samples versus controls. A comparative analysis of seven RNA sequence transcriptomes treated with CPPU showed major effects linked to primary metabolism, specifically carbon and amino acid biosynthesis pathways and photosynthesis genes, especially those associated with chlorophyll production and anthocyanin biosynthesis [67]. The application of CPPU most affected and downregulated genes such as PAL, CHS, and F3’H in the pericarp. According to the authors, further investigation is required to reveal the impact of CPPU in litchi fruit maturation at the color break stage.

3.4.3. Effect of Cytokinin Application against Postharvest Physiological Disorders

Physiological disorders such as pericarp browning, chilling injury, bitter pit, shatter, and cracking reduce the quality, commercial acceptability, and shelf life of fruits [244,281]. Pericarp browning is a major postharvest problem for many fruits, which is mainly due to the desiccation of pericarp and degradation of anthocyanin pigments along with the oxidation of phenolic compounds [281,282]. This leads to an excessive accumulation of ROS, which could cause lipid peroxidation, membrane damage, and consequently premature fruit senescence [281,283,284]. Previous studies have demonstrated the great potential of CKs to enhance both antioxidant compounds, such as ascorbate/ascorbic acid (AsA) and glutathione, and enzymes such as SOD, catalase (CAT), ascorbate peroxidase (APX), and peroxidase (POD), which may inhibit fruit quality deterioration during storage [262,282,283]. A study by Zhang et al. [259] showed that the postharvest application of BA (0.1 g/L) effectively reduced ROS and H2O2 accumulation, PPO activity, and lipid peroxidation in litchi compared to control samples, thereby inhibiting pericarp browning and extending storage by 8 days. This could be attributed to the observed 2-fold rise in SOD, CAT, and APX activities in treated fruits compared to the controls during storage. Reactive oxygen species, for example (O2•−), are efficiently converted to H2O2 by the action of SOD, while H2O2 is destroyed predominantly by APX and CAT [259,262]. Based on Chen and Yang [262] report, a 50 mM BA treatment significantly reduced membrane permeability and lipid peroxidation, as well as delayed the rate of O2•− production and H2O2 accumulation. In that study, the activities of SOD, CAT, APX, and glutathione reductase (GR) in cucumber were positively correlated to the amounts of measured superoxides and extended shelf life under chilling stress conditions throughout a 16-day period, which was reflected by better postharvest longevity within the treated group.

Moreover, adenosine triphosphate (ATP) content was almost 2-fold higher compared to the control, resulting in a higher level of energy charge, thereby inhibiting chilling injury (Table 7). In addition, the fruits exposed to BA had better antioxidant activity and less pericarp browning [259,262]. Evidence of the scavenging of ROS produced within the pericarp [285] and the protection of the fruits from oxidation reactions during storage [282] currently exist. Moreover, preharvest application of CKs is not only beneficial while the fruit is undergoing development: it may have latent effects that are associated with postharvest performance, significantly reducing physiological disorders such as berry shatter and rachis necrosis in grapes during storage [240,241].

In addition to enhanced firmness, reduction in water loss by 4.6% and natural browning by more than 2-fold in CK-treated banana compared to the control during the storage were evident [261,271]. Furthermore, Ainalidou et al. [196] reported that the preharvest application of CPPU effectively reduced weight loss by 33% in kiwifruit compared to the control, and it extended storage by 2 months; thus, CKs are effective in controlling structural damages in fruits. According to Biton et al. [222], postharvest application of BA (40 µg/mL) significantly reduced cuticle cracking by 45% in persimmons. The treatment also reduced naturally occurring black spots by 40% to 50% in treated fruits compared to the control and extended shelf life by 12 weeks (Table 6).

3.4.4. Effect of Cytokinin Application against Fruit Pathogen Infection

Microbial attacks can be severely detrimental to crop yields, causing insurmountable losses if no proper control measures for infections are undertaken. Although the utilization of CK-based approach for controlling plant pathogenic attacks is not popular, the limited studies suggest that CK applications have antibacterial and antifungal activities against different fruit pathogens. Studies highlighting the effectiveness of applied CKs in inhibiting postharvest fungal pathogens in various fruits are presented in Table 6 and Table 7. For example, the preharvest application of ‘Superlon’ (a mixture of GA4+7 and BA) at 40 µg/mL resulted in a 45% reduction in the incidence of naturally occurring alternaria black spot (ABS) disease caused by Alternaria alternata in persimmon after three months of storage [222]. As demonstrated by Yu et al. [256], BA (20 µg/mL) enhanced the efficacy of Cryptococcus laurentii, which is a well-known postharvest yeast antagonist, in reducing postharvest blue mold disease in vivo in apples compared to the controls. Similar observations were reported by Zhang et al. [259], who demonstrated that the antifungal activity of BA (0.1 g/L) effectively inhibited the decay incidence of harvested litchi by more than 2-fold via the inhibition of Peronophythora litchii during 8 days of storage.

Mechanisms for protection against microbial diseases need not only be effective once the plant pathogen has established itself, but those strategies that are preventative in the manifestation of disease are also highly desirable therapies in an agricultural setup (Figure 2). Table 7 summarizes some of the studies demonstrating CK-enhanced disease resistance in fruit crops through the elicitation of defense-related enzymes. As an example, the postharvest application of BA alone or in combination with Cryptococcus laurentii at the optimal concentration (1000 μg/mL) effectively inhibited mold infection caused by Penicillium expansum in pears, which was mainly attributed to the increase in CAT activity, and it extended storage by 6 days compared to the control [252]. Zhang et al. [264] recorded higher SOD, POD, and PPO activities in peach wounds inoculated with 500 mg/L BA, successfully controlling the brown rot caused by Monilinia fructicola with a 63% reduction in treated fruits compared to those that were untreated. As shown by Zhang et al. [259], BA (0.1 g/L) significantly inhibited the decay incidence of harvested litchi via the inhibition of Peronophythora litchii during 8 days of storage, which was attributed to the increase of PAL activity, the key enzyme involved in the biosynthesis of phenolic compounds and the upregulation of defense signals in the fruits. As BA appears to control microbial plant infections, it may be prudent to explore other CKs or compounds with CK-like activity in the future. Thus, the priming of fruit crops to impart defense against plant pathogens is gaining popularity as a new technological application.

4. Concluding Remarks and Future Prospects

In general, the intrinsic complexity of the function of CKs in plants requires a highly integrated and interdisciplinary approach that spans across different fields of plant sciences, for the artistic exploitation of these important regulators of plant growth and development in horticultural fruit crops. Although the use of CKs is a routine practice in plant propagation, mass propagation, and agronomic field setups, their application in postharvest fruit management is limited. New opportunities for their exploitation in postharvest fruit processing are evident.

The high variability in response to CK applications is highly dependent on multiple factors that require considerations in practice. Synthetic compounds such as CPPU, a phenylurea synthetic CK that has become one of the widely used chemicals with CK-like effects in fruit production globally, still show inconsistencies in its effects, which may depend on factors such as genotype (cultivar), phenological stage, concentration, and synergistic interactions arising from combinations with other PGRs [14]. The CK type, whether it be natural or synthetic, also leads to variable effects at different phases of fruit crop production. For fruit development, CPPU, TDZ, and mT appear to be the most effective CKs, as demonstrated in some fruit crops, but these effects are never necessarily all inclusive. Although not necessarily covered in this particular review, microbial communities that form associations with plants may contribute to endogenous CK pool. At present, the relationship between microbiome-synthesized CKs and growth-promoting effects is still not well understood or resolved. However, despite their routine applications in many different species, knowledge gaps about influences of CKs in fruit development still exist. Mechanisms of action linked to exogenous CKs in various fruit crops (except for model plants) are barely understood. This is largely reflective of a past mindset in applied agricultural research that did not necessarily examine questions related to the mechanistic aspects; thus, the fundamental information of these processes remains unknown. Next-generation technologies have provided insights into global transcriptome changes in relation to CK-responsive genes, and many of these are involved in signaling, metabolism, and transport mechanisms that control plant growth and development [51]. Genome-wide studies at the transcriptome and proteome levels may reveal interactive protein–protein networks that ultimately contribute to regulating biological growth processes in developing fruits. Studies that provide global insights into molecular mechanisms and genes involved in both preharvest and postharvest biological processes that may be appropriate targets in the development of novel strategies for crop improvements are starting to emerge. However, not all details are available in terms of the basic growth and developmental effects of CKs in fruit crops, as there are unresolved issues related to shoot branching, root branching, and fruit production. The development of new innovative technologies that will exploit the different biological actions of CKs in plants requires an understanding of the modes of action, target sites, genetic-to-metabolomic networks, CK-responsive target genes, and their functional network activity, responses to environmental stresses, and climate changes, to name a few. Such fundamental knowledge is critical for the exploitation of CKs on a broader range of crops, especially for the postharvest quality preservation of fruits. Many investigations that test the effect of CKs on stress are under controlled environments, indicating that CKs are modulators of stress acting through a growth-defense trade-off [53]. In natural and/in-field agricultural settings, influences of CKs on genotype–environment interactions are still poorly understood, and future studies should focus more rigorously on testing CK stress modulation in natural environments for agricultural ecosystem management, especially in the context of climate change. The application of CK as priming agents to engage plant immunity for biotic stress responses and biotrophic is evident in the literature. However, the adoption of priming technology to circumvent or prepare plants for coping with abiotic stresses is rare, and this is especially true for horticultural fruit crops.

While fruit expansion is a key event, there is limited literature covering the role of CKs in the transition from the cell division to the expansion phases and the sustained growth of the fruit. Besides, remarkably few authors have examined if other phytohormones contribute to regulating the production of volatile chemicals during ripening. With other ripening characteristics completely overlooked, it is becoming clear that without a complete understanding of the role of CKs in fruit improvement and management, novel biotechnologies, notably CRISPR/Cas9 mutagenesis, may be more challenging to implement. Despite the proven importance of CKs for micropropagation, Karkute et al. [26] emphasized that the lack of reproducible in vitro regeneration protocols for many fruit crops is hindering the wide application of CRISPR/Cas9 technologies. For many fruit crops, artificial mutant technology is not easy to exploit, as reference genome sequence information is not always available. This information could assist with our understanding of genetic mechanisms that underpin the functioning of CKs. Therefore, such advances will require the use of a broader range of horticultural fruit crops as new models to provide a better understanding of the broader functioning of CKs and their regulatory controls in developmental pathways. This understanding is important in order to increase output and meet the goals of food security and sustainable fruit production.

Author Contributions

A.O.A., O.A.F., and N.P.M. conceptualized the review paper and wrote different sections aligned to their expertise; N.A.M., M.M., and N.M.D.B. prepared the draft for the other sections; S.O.A., L.S., and K.D. provided critical input on the draft version. All authors read and approved the final version for submission. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

We acknowledge the financial support from North-West University, University of Johannesburg, Stellenbosch University, Durban University of Technology and Agricultural Research Council, South Africa. Research funding from the South African National Research Foundation (NRF) to AOA and NPM (Incentive Funding for Rated Researchers, Grant UID: 109508 and 76555, respectively) and MM (Incentive Funding for Rated Researchers), and from the University Research Committee (University of Johannesburg; OAF and BNMD), is appreciated. L.S. and K.D. acknowledge the ERDF project entitled “Development of Pre-Applied Research in Nanotechnology and Biotechnology” (No. CZ.02.1.01/0.0/0.0/17_048/0007323). The APC was funded by the University of Johannesburg, South Africa.

Acknowledgments

We appreciate the support from our respective institutions.

Conflicts of Interest

We declare no conflict of interest. All the funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Kaminek, M. Tracking the story of cytokinin research. J. Plant Growth Regul. 2015, 34, 723–739. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merchant, S.S.; Gruissem, W.; Ort, D. Annual review of plant biology 2017. Curr. Sci. 2018, 115, 431–449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Srivastava, L.M. Introduction to Some Special Aspects of Plant Growth and Development; Elsevier BV: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2002; p. 1. [Google Scholar]

- Stirk, W.A.; Van Staden, J. Flow of cytokinins through the environment. Plant Growth Regul. 2010, 62, 101–116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jameson, P.E.; Song, J. Cytokinin: A key driver of seed yield. J. Exp. Bot. 2015, 67, 593–606. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]