Abstract

Photobiomodulation (PBM) might be an effective treatment for Parkinson’s disease (PD) in human patients. PBM of the brain uses red or near infrared light delivered from a laser or an LED at relatively low power densities, onto the head (or other body parts) to stimulate the brain and prevent degeneration of neurons. PD is a progressive neurodegenerative disease involving the loss of dopamine-producing neurons in the substantia nigra deep within the brain. PD is a movement disorder that also shows various other symptoms affecting the brain and other organs. Treatment involves dopamine replacement therapy or electrical deep brain stimulation. The present systematic review covers reports describing the use of PBM to treat laboratory animal models of PD, in an attempt to draw conclusions about the best choice of parameters and irradiation techniques. There have already been clinical trials of PBM reported in patients, and more are expected in the coming years. PBM is particularly attractive as it is a non-pharmacological treatment, without any major adverse effects (and very few minor ones).

1. Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a multifactorial and multisystem disease, characterized by the loss of the dopamine producing neuronal cells of the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNc) in the brain [1,2]. The lack of dopamine primarily affects the motor function, but there are many other signs and symptoms that affect mood, cognition, digestive system, sense of smell, etc. The motor symptoms include bradykinesia, muscular rigidity, tremor at rest, and postural instability. The dopamine producing neurons die off, and one somewhat controversial theory to explain this is the accumulation of Lewy bodies containing aggregated α-synuclein inside the cells. The causes of PD are not completely understood. Only about 15% of PD patients are likely to have a genetic cause, among which mutations in leucine-rich repeat kinase 2 (LRRK2), GBA1 (glucocerebrosidase), and SNCA (α-synuclein) are the most common [3]. The environmental causes are complex, but recent evidence has implicated mitochondrial dysfunction [4] and changes in the gut microbiome [5]. Over 1 million individuals in the US suffer from PD and the annual financial burden is estimated to be $52 billion [6]. The accepted treatment is replacement of the lost dopamine using Levodopa, which helps the motor symptoms but does not modify the course of the disease [7]. Monoamine oxidase-B inhibitors and dopamine agonists might be used later in the course of the disease. Deep brain stimulation (DBS) using an electrode implanted into the subthalamic nucleus and other brain regions has also shown promising results [8].

Photobiomodulation (PBM) involves the use of low-powered red and near-infrared (NIR) light from a laser or light-emitting diode (LED) to stimulate, heal, and regenerate damaged or dying tissues [9]. PBM was previously known as low-level laser (light) therapy (LLLT) [10]. PBM was discovered by Endre Mester soon after the first ruby laser was discovered by Ted Maiman in 1960 [11]. For many years, it was thought that a coherent laser beam was necessary for effective PBM [12], but now it is appreciated that in many situations, LEDs might be a better choice [13]. The mechanism of action primarily involves absorption of the light through the mitochondria, leading to an increased membrane potential, electron transport, oxygen consumption, and ATP synthesis [9]. Since the brain is heavily dependent on mitochondrial activity, it is not surprising that PBM has been extensively tested to treat various brain disorders [14]. Many signaling pathways are activated by PBM, including those mediated by reactive oxygen species (ROS), leading to the up-regulation of anti-oxidant defenses [15]. Anti-apoptotic and pro-survival signaling is also activated [16]. Moreover the ability to switch mitochondrial respiration from glycolysis towards oxidative phosphorylation has two other important effects. First, stem cells are mobilized from their hypoxic niche and can migrate towards sites of injury where they can repair the damage [17]. Second, the mitochondrial alteration can switch the macrophage and microglial phenotype from the pro-inflammatory M1 state, to the anti-inflammatory and phagocytic M2 state [18]. In the brain, neurotrophic factors (such as brain-derived neurotrophic factor [BDNF]) are up-regulated [19], adult hippocampal neurogenesis is stimulated [20], and synaptogenesis and neuroplasticity is encouraged [19].

These latter effects can be thought of as “helping the brain to repair itself”, and suggest that PBM can be useful for many traumatic brain disorders, such as stroke [21] and traumatic brain injury [22], as well as neurodegenerative brain disorders like Alzheimer’s disease [23] and PD [24]. One question that is often asked about PBM for the brain, is how important is it to apply the light to the head and for the photons to actually penetrate into the brain tissue, or else how important is it for the light to be absorbed by the circulating blood or bone marrow? The latter pathways might explain the systemic or abscopal effects of PBM, which have been reported by many authors [25]. The recent discovery of respiratory-competent cell free mitochondria that are circulating in the blood of normal individuals [26] might offer an explanation for how the beneficial effects of light that is incident on the body can be transmitted to distant organs including the brain. Calculation or measurement of the fraction of photons that are incident on the scalp and which penetrate the cortex, and especially into deeper brain structures (such as the SNc), is not particularly encouraging [27], suggesting that for PD, the abscopal effect, or the application of light to the abdomen, to affect the gut microbiome (“photobiomics” [28]), might be important.

The goal of the present paper was to undertake a systematic review of published studies, which have examined the use of PBM therapy to treat PD in animal models, to see if any conclusions about the parameters and methods can be drawn.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Search Strategy

The primary search was conducted from 1990 to November 2019. Bibliographic databases (i.e., MEDLINE through PubMed, SCOPUS, Web of Science, EMBASE and Cochrane Library) were searched electronically for studies on the neuroprotective effects of PBM on animal models of PD, through the keywords “photobiomodulation”, “low-level light therapy”, “low-level laser therapy”, “near-infrared light”, “red light”, “Parkinson’s disease”, and “Parkinsonism”. Two independent investigators screened the title, abstract and the full text of the articles and judged the searched materials against the inclusion and exclusion criteria. The search was limited to the original studies performed in animals and to publications written in English. Therefore, ex vivo, in vitro or clinical original articles, as well as review articles were not included.

2.2. Inclusion and Exclusion Criteria

We included all in vivo studies reporting the effects of PBM, as opposed to vehicles, on the behavioral and molecular outcomes in PD models. Studies conducting PBM via transcranial, intracranial, systemic irradiation (remotely or laser acupuncture irradiations) as well as whole-body irradiation approaches in PD models were included. Studies performed on ex vivo or in vitro (primary cultures or cell line), as well as clinical trials, were excluded. Additionally, studies conducted on intact (healthy) animals were excluded from our review. Moreover, non-English language publications and studies involving NIR spectroscopy and conference papers were excluded.

2.3. Data Extraction

The author, publication year, animals and species, number of animals in each experimental group, gender and age, type of PD model, light source/wavelength, output power, irradiance (power density), irradiation time, fluence (energy density) or energy (dose), total fluence or dose, irradiation approach/site, number of treatment sessions, and outcome(s) were extracted. However, the time of outcome evaluation was not extracted from the studies.

3. Results

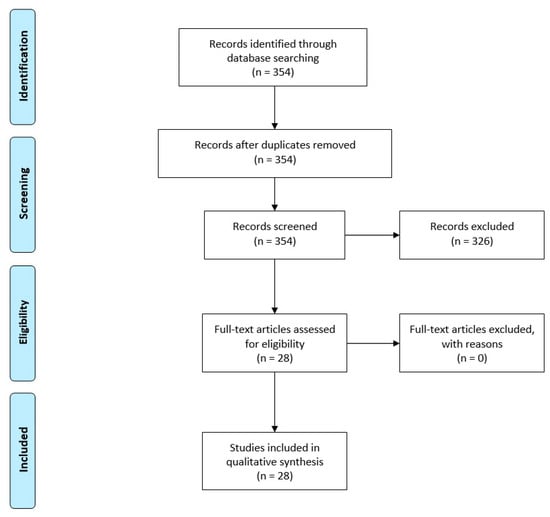

The initial systematic search of the mentioned databases identified 354 articles, of which 28 studies met the inclusion criteria (Figure 1). Twenty-two articles reported experiments in rodents, five articles reported studies in primates (macaque monkey, Macaca fascicularis), and one study was conducted in a Pink1 mutant PD model. Of the twenty-two studies on rodents, sixteen studies assessed the effects of PBM in mice, of which thirteen were on the albino BALB/c strain and three were on the C57BL/6 strain. Additionally, six rodent studies were performed on rats, of which five were on the Sprague–Dawley strain and one was on the albino Wistar strain. It should be noted that in one study, more than one experiment was conducted using three different animal species of BALB/c mice, Wistar rats, and macaque monkeys; and also in one study, two different types of irradiation methods, transcranial or remote-tissue were performed; in these cases, each experiment was regarded as a separate study and was included in the systematic review.

Figure 1.

Systematic review flow chart for the inclusion of eligible studies.

Animal models of PD were induced using injections of methyl-4-phenyl-1,2,3,6-tetrahydropyridine (MPTP) in mice or primates. Other models used 6-hydroxydopamine (6OHDA) in rats, and rotenone in Drosophila Pink1 mutants. In the context of molecular and biochemical assessments, the possible neuroprotective effects of PBM were evaluated in various brain regions, including the SNc, subthalamic nucleus (STN), striatum, zona incerta (ZI), zona incerta-hypothalamus (ZI-Hyp), caudate putamen (CPu) and periaqueductal grey matter (PaG).

In fifteen studies, laser or LED light was delivered to the head of the animal in a transcranial approach. On the other hand, nine studies used an intracranial irradiation approach via implantation of an optical fiber connected to a light source into the region of interest inside the brain. In addition, four studies performed systemic PBM using remote-tissue irradiation (abscopal effect) or laser acupuncture methods. Whole-body PBM was carried out in one study of Pink1 Drosophila mutant PD model. Eighteen studies applied LED-based devices, while eleven studies used lasers as light sources. Twenty six studies performed PBM with red/far-red wavelengths (627 nm [one study], 630 nm [one study], 670 nm [twenty one studies], and 675 nm [two studies]), whereas, four studies used NIR light (808 nm) and only in one study blue light (405 nm) was delivered via an acupuncture point. The operation mode of light sources in all studies was a continuous wave (CW). Other physical treatment parameters, such as output power, irradiance, irradiation time, fluence, total delivered dose, numbers and duration of treatment sessions are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summary of Studies on the Effects of Photobiomodulation Therapy in Animal Models of Parkinson’s Disease.

4. Discussion

The evidence that has been presented in this systematic review does suggest that PBM (and in particular transcranial PBM) is an effective method to treat animal models of PD. The discovery of the toxic effects of MPTP, which is an impurity found in recreational drugs consumed by individuals in San Francisco in 1982, for the first time allowed the creation of laboratory animal models of PD [52]. Besides MPTP, other compounds have been used to produce PD-like models [53], including 6-hydroxydopamine (6-OHDA) paraquat, rotenone, and Maneb (a polymeric Mn complex of ethylene bis (dithiocarbamate). The mechanism of action of these compounds usually involves metabolism into intermediates that can undergo redox cycling and thereby damage the mitochondria, and in particular Complex 1. There have also been genetic models of PD involving mutations to genes such as α-synuclein, Parkin (an ubiquitin E3 ligase), PINK1 (PTEN-induced putative kinase 1), and LRRK2 (leucine-rich repeat kinase 2). Although the animal models of PD do not completely mimic the human disease, they have been useful for studying the pathophysiology of PD, and for testing the effectiveness of novel treatments, including DBS and PBM. It is expected that further animal studies will use PBM in genetically engineered models of PD rather than toxin-induced models, because these are now considered to be more representative of the human disease.

Although most of animal studies have used red light (670 nm, 675 nm or 630 nm), this does not necessarily mean that red wavelengths are better than NIR wavelengths (810 nm). This preponderance might simply reflect the wider use of red LEDs in ophthalmology and wound healing. The power density levels employed were generally between 20–50 mW/cm2, but occasionally lower or higher values were employed. Moderate illumination times (minutes) generally provided fluences in the range of 10–60 J/cm2 on the scalp. The intracranial fibers that were implanted into the brain delivered fairly low powers (up to 14 mW), but when the illumination was continued for several days, the total energy density delivered could be quite large. It should be noted that the regions of the brain where optical fibers are implanted are different from the regions where electrodes are implanted in the DBS procedure. In DBS, electrodes are usually implanted into the globus pallidus internus to improve the motor function [54] or into the subthalamic nucleus [55] or the caudal zona incerta to improve tremor [56]. The optical fibers in PD animal models have been implanted into the mid-brain, with the goal of delivering the light as close as possible to the SNc, to preserve the dopamine producing neurons.

Pulsing is an interesting parameter for brain PBM therapy, as it has been found that pulsing the light at certain frequencies is more effective than CW light [57]. The two most popular frequencies are 10 Hz (the so-called alpha rhythm) and 40 Hz (the so-called gamma rhythm). The idea is that these frequencies can resonate with intrinsic brain rhythms, and therefore, can improve brain function to a greater extent than CW light [57]. The repetition regimens that have been used for treating the animal models of PD range from a few times per day to every few days, for periods that could be as long as 4 weeks. As PD in humans is a chronic degenerative disease, it is expected that PBM therapy would need to be continued for the foreseeable future.

The encouraging results that have been obtained in the animal studies reviewed above have led to the initiation of clinical studies of PBM therapy for PD patients. Hamilton and colleagues described the construction of “light buckets” lined with LEDs (670, 810 and 850 nm) to treat patients with PD [58] (Figure 2). These devices delivered a power density of 10 mW/cm2 to the entire head, and in addition an intranasal device with a power of 4 mW/cm2 was employed. Patients were treated twice a day (1800 J per session) for 30 days. The initial symptoms of tremor, akinesia, gait, difficulty in swallowing and speech, poor facial animation, and reduced fine motor skills, loss of the sense of smell, and impaired social confidence were all improved in ~75% of the subjects, while ~25% remained the same and none got worse. The improvements were still maintained over an extended period (up to 24 months). Santos et al. conducted a randomized controlled trial in Parkinson’s patients using a CW 670 nm LED array (WARP 10) over 10 cm2, on 6 sites on both temples at 60 mW/cm2, delivering 6 J/cm2 and a total energy of 2160 J [59]. A total of 18 sessions were given over 9 weeks leading to clinical improvements.

Figure 2.

Photograph of the “light bucket” described by Hamilton et al. [24].

Additional clinical trials are in progress that, in addition to applying light to the head also apply light to the abdomen, with the goal of improving the gut microbiome. The results are eagerly awaited.

Author Contributions

F.S. Writing—Original Draft, Data Curation, Formal analysis; M.R.H.: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing—Original Draft, Writing—Review & Editing, Funding acquisition. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

MRH was funded by US NIH Grants R01AI050875 and R21AI121700.

Acknowledgments

The authors express their sincere gratitude to Fariba Pashazadeh M.Sc., for assisting with the literature research.

Conflicts of Interest

F.S. is on the Scientific Advisory Board and is a consultant of Niraxx Light Therapeutics, Inc., Irvine, CA and a consultant of ProNeuroLIGHT LLC. Phoenix, AZ. M.R.H. is on the following Scientific Advisory Boards: Transdermal Cap, Inc.; Cleveland, OH; BeWell Global, Inc.; Wan Chai, Hong Kong; Hologenix, Inc. Santa Monica, CA; LumiThera, Inc., Poulsbo, WA; Vielight, Toronto, Canada; Bright Photomedicine, Sao Paulo, Brazil; Quantum Dynamics LLC, Cambridge, MA; Global Photon, Inc., Bee Cave, TX; Medical Coherence, Boston MA; NeuroThera, Newark DE; JOOVV, Inc., Minneapolis-St. Paul MN; AIRx Medical, Pleasanton CA; FIR Industries, Inc. Ramsey, NJ; UVLRx Therapeutics, Oldsmar, FL;UltraluxUV, Inc., Lansing MI; Illumiheal & Petthera, Shoreline, WA; MB Lasertherapy, Houston, TX; ARRC LED, San Clemente, CA; Varuna Biomedical Corp. Incline Village, NV; Niraxx Light Therapeutics, Inc., Boston, MA; M.R.H. has been a consultant for Lexington Int, Boca Raton, FL; USHIO Corp, Japan; Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany; Philips Electronics Nederland B.V.; Johnson & Johnson, Inc., Philadelphia, PA; Sanofi-Aventis Deutschland GmbH, Frankfurt am Main, Germany; M.R.H. is a stockholder in Global Photon, Inc., Bee Cave, TX; Mitonix, Newark, DE.

Abbreviations

| 6OHDA | 6-hydroxydopamine |

| α-syn | alpha synuclein |

| CPu | caudate putamen |

| CXCR4 | chemokine receptor 4 |

| CW | continuous wave |

| DMS | delayed match-to-sample |

| GDNF | glial cell line-derived neurotrophic factor |

| GFAP | glial fibrillary acidic protein |

| GFAP+ | glial fibrillary acidic protein positive |

| GSH-Px | glutathione peroxidase |

| IBA1 | ionized calcium-binding adapter molecule 1 |

| IFN-γ | interferon-gamma |

| IL2 | Interleukin 2 |

| LED | light-emitting diode |

| MDA | malondialdehyde |

| MPTP | 1-methyl-4-phenyl-1, 2, 3, 6-tetrahydropyridine |

| NA | not available |

| NR | not reported |

| PaG | periaqueductal grey matter |

| PBM | photobiomodulation |

| PD | Parkinson’s disease |

| PVT | psychomotor vigilance task |

| SNc | substantia nigra pars compacta |

| STN | subthalamic nucleus |

| TH | tyrosine hydroxylase |

| TNF-α | tumor necrosis factor-alpha |

| WT | wild type |

| ZI | zona incerta |

| ZI-Hyp | zona incerta-hypothalamus |

References

- Elsworth, J.D. Parkinson’s Disease Treatment: Past, Present, and Future. J. Neural Transm. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kalia, L.V.; Lang, A.E. Parkinson’s disease. Lancet 2015, 386, 896–912. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Toffoli, M.; Vieira, S.R.L.; Schapira, A.H.V. Genetic causes of PD: A pathway to disease modification. Neuropharmacology 2020, 170, 108022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zaia, A.; Maponi, P.; Zannotti, M.; Casoli, T. Biocomplexity and Fractality in the Search of Biomarkers of Aging and Pathology: Mitochondrial DNA Profiling of Parkinson’s Disease. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 2020, 21, 1758. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bullich, C.; Keshavarzian, A.; Garssen, J.; Kraneveld, A.; Perez-Pardo, P. Gut Vibes in Parkinson’s Disease: The Microbiota-Gut-Brain Axis. Mov. Disord. Clin. Pr. 2019, 6, 639–651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parkinson’s Disease Economic Burden On Patients, Families And The Federal Government Is $52 Billion, Doubling Previous Estimates. Available online: https://www.prnewswire.com/news-releases/parkinsons-disease-economic-burden-on-patients-families-and-the-federal-government-is-52-billion-doubling-previous-estimates-300867192.html (accessed on 16 March 2020).

- De Bie, R.M.A.; Clarke, C.E.; Espay, A.J.; Fox, S.H.; Lang, A.E. Initiation of pharmacological therapy in Parkinson’s disease: When, why, and how. Lancet Neurol. 2020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Merola, A.; Romagnolo, A.; Krishna, V.; Pallavaram, S.; Carcieri, S.; Goetz, S.; Mandybur, G.; Duker, A.P.; Dalm, B.; Rolston, J.D.; et al. Current Directions in Deep Brain Stimulation for Parkinson’s Disease-Directing Current to Maximize Clinical Benefit. Neurol. Ther. 2020. Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chung, H.; Dai, T.; Sharma, S.K.; Huang, Y.Y.; Carroll, J.D.; Hamblin, M.R. The nuts and bolts of low-level laser (light) therapy. Ann. Biomed. Eng. 2011, 40, 516–533. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anders, J.J.; Lanzafame, R.J.; Arany, P.R. Low-level light/laser therapy versus photobiomodulation therapy. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2015, 33, 183–184. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mester, A.; Mester, A. The History of Photobiomodulation: Endre Mester (1903–1984). Photomed. Laser Surg. 2017, 35, 393–394. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moskvin, S.V. Only lasers can be used for low level laser therapy. Biomedicine 2017, 7, 22. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Heiskanen, V.; Hamblin, M.R. Photobiomodulation: Lasers vs. light emitting diodes? Photochem. Photobiol. Sci. 2018, 17, 1003–1017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamblin, M.R. Shining light on the head: Photobiomodulation for brain disorders. BBA Clin. 2016, 6, 113–124. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- de Freitas, L.F.; Hamblin, M.R. Proposed Mechanisms of Photobiomodulation or Low-Level Light Therapy. IEEE J. Sel. Top. Quantum Electron. 2016, 22, 7000417. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liang, H.L.; Whelan, H.T.; Eells, J.T.; Meng, H.; Buchmann, E.; Lerch-Gaggl, A.; Wong-Riley, M. Photobiomodulation partially rescues visual cortical neurons from cyanide-induced apoptosis. Neuroscience 2006, 139, 639–649. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abrahamse, H.; Hamblin, M.R. Photomedicine and Stem Cells; Morgan & Claypool Publishers: San Rafael, CA, USA, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- De Sousa, K.; Rodrigues, M.; de Santos, D.; Mesquita-Ferrari, R.A.; Nunes, F.D.; da Silva, D.d.T.; Bussadori, S.K.; Fernandes, K.P.S. Differential expression of inflammatory and anti-inflammatory mediators by M1 and M2 macrophages after photobiomodulation with red or infrared lasers. Lasers Med Sci. 2019, 35, 337–343. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, W.; Agrawal, T.; Huang, L.; Gupta, G.K.; Hamblin, M.R. Low-level laser therapy for traumatic brain injury in mice increases brain derived neurotrophic factor (BDNF) and synaptogenesis. J. Biophotonics 2015, 8, 502–511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xuan, W.; Vatansever, F.; Huang, L.; Hamblin, M.R. Transcranial low-level laser therapy enhances learning, memory, and neuroprogenitor cells after traumatic brain injury in mice. J. Biomed. Opt. 2014, 19, 108003. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamblin, M.R. Photobiomodulation for traumatic brain injury and stroke. J. Neurosci. Res. 2017, 96, 731–743. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thunshelle, C.; Hamblin, M.R. Transcranial Low-Level Laser (Light) Therapy for Brain Injury. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2016, 34, 587–598. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamblin, M.R. Photobiomodulation for Alzheimer’s Disease: Has the Light Dawned? Photonics 2019, 6, 77. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, C.L.; el Khoury, H.; Hamilton, D.; Nicklason, F.; Mitrofanis, J. “Buckets”: Early Observations on the Use of Red and Infrared Light Helmets in Parkinson’s Disease Patients. Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2019, 37, 615–622. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnstone, D.; el Massri, N.; Moro, C.; Spana, S.; Wang, X.; Torres, N.; Chabrol, C.; de Jaeger, X.; Reinhart, F.; Purushothuman, S. Indirect application of near infrared light induces neuroprotection in a mouse model of parkinsonism–an abscopal neuroprotective effect. Neuroscience 2014, 274, 93–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Dache, Z.A.A.; Otandault, A.; Tanos, R.; Pastor, B.; Meddeb, R.; Sanchez, C.; Arena, G.; Lasorsa, L.; Bennett, A.; Grange, T.; et al. Blood contains circulating cell-free respiratory competent mitochondria. FASEB J. 2020, 34, 3616–3630. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salehpour, F.; Cassano, P.; Rouhi, N.; Hamblin, M.R.; de Taboada, L.; Farajdokht, F.; Mahmoudi, J. Penetration Profiles of Visible and Near-Infrared Lasers and Light-Emitting Diode Light Through the Head Tissues in Animal and Human Species: A Review of Literature. Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2019, 37, 581–595. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liebert, A.; Bicknell, B.; Johnstone, D.M.; Gordon, L.C.; Kiat, H.; Hamblin, M.R. “Photobiomics”: Can Light, Including Photobiomodulation, Alter the Microbiome? Photobiomodul. Photomed. Laser Surg. 2019, 37, 681–693. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, V.E.; Spana, S.; Ashkan, K.; Benabid, A.L.; Stone, J.; Baker, G.E.; Mitrofanis, J. Neuroprotection of midbrain dopaminergic cells in MPTP-treated mice after near-infrared light treatment. J. Comp. Neurol. 2010, 518, 25–40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peoples, C.; Shaw, V.E.; Stone, J.; Jeffery, G.; Baker, G.E.; Mitrofanis, J. Survival of dopaminergic amacrine cells after near-infrared light treatment in MPTP-treated mice. ISRN Neurol. 2012, 2012, 850150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shaw, V.E.; Peoples, C.; Spana, S.; Ashkan, K.; Benabid, A.-L.; Stone, J.; Baker, G.E.; Mitrofanis, J. Patterns of cell activity in the subthalamic region associated with the neuroprotective action of near-infrared light treatment in MPTP-treated mice. Park. Dis. 2012, 2012, 296875. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peoples, C.; Spana, S.; Ashkan, K.; Benabid, A.-L.; Stone, J.; Baker, G.E.; Mitrofanis, J. Photobiomodulation enhances nigral dopaminergic cell survival in a chronic MPTP mouse model of Parkinson’s disease. Park. Relat. Disord. 2012, 18, 469–476. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, C.; Torres, N.; el Massri, N.; Ratel, D.; Johnstone, D.M.; Stone, J.; Mitrofanis, J.; Benabid, A.-L. Photobiomodulation preserves behaviour and midbrain dopaminergic cells from MPTP toxicity: Evidence from two mouse strains. BMC Neurosci. 2013, 14, 40. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Purushothuman, S.; Nandasena, C.; Johnstone, D.M.; Stone, J.; Mitrofanis, J. The impact of near-infrared light on dopaminergic cell survival in a transgenic mouse model of parkinsonism. Brain Res. 2013, 1535, 61–70. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Vos, M.; Lovisa, B.; Geens, A.; Morais, V.A.; Wagnières, G.; van den Bergh, H.; Ginggen, A.; de Strooper, B.; Tardy, Y.; Verstreken, P. Near-infrared 808 nm light boosts complex IV-dependent respiration and rescues a Parkinson-related pink1 model. PLoS ONE 2013, 8, e78562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wattanathorn, J.; Sutalangka, C. Laser acupuncture at HT7 acupoint improves cognitive deficit, neuronal loss, oxidative stress, and functions of cholinergic and dopaminergic systems in animal model of parkinson’s disease. Evidence-Based Complement. Altern. Med. 2014, 2014, 937601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinhart, F.; El Massri, N.; Darlot, F.; Torres, N.; Johnstone, D.M.; Chabrol, C.; Costecalde, T.; Stone, J.; Mitrofanis, J.; Benabid, A.-L. 810 nm near-infrared light offers neuroprotection and improves locomotor activity in MPTP-treated mice. Neurosci. Res. 2015, 92, 86–90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Darlot, F.; Moro, C.; El Massri, N.; Chabrol, C.; Johnstone, D.M.; Reinhart, F.; Agay, D.; Torres, N.; Bekha, D.; Auboiroux, V. Near-infrared light is neuroprotective in a monkey model of P arkinson disease. Ann. Neurol. 2016, 79, 59–75. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Oueslati, A.; Lovisa, B.; Perrin, J.; Wagnières, G.; van den Bergh, H.; Tardy, Y.; Lashuel, H.A. Photobiomodulation suppresses alpha-synuclein-induced toxicity in an AAV-based rat genetic model of Parkinson’s disease. PLoS ONE 2015, 10, e0140880. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moro, C.; el Massri, N.; Darlot, F.; Torres, N.; Chabrol, C.; Agay, D.; Auboiroux, V.; Johnstone, D.M.; Stone, J.; Mitrofanis, J. Effects of a higher dose of near-infrared light on clinical signs and neuroprotection in a monkey model of Parkinson’s disease. Brain Res. 2016, 1648, 19–26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salgado, A.S.; Ribeiro, L.G.; Oliveira, T.B.; Rolão, M.P.; Gomes, J.C.; Carraro, E.; Perreira, M.C.; Suckow, P.T.; Kerppers, I.I. Effects of Light Emitting Diode and Low-intensity Light on the immunological process in a model of Parkinson’s disease. Med Res. Arch. 2017, 4. Issue 8, December, 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhart, F.; el Massri, N.; Chabrol, C.; Cretallaz, C.; Johnstone, D.M.; Torres, N.; Darlot, F.; Costecalde, T.; Stone, J.; Mitrofanis, J. Intracranial application of near-infrared light in a hemi-parkinsonian rat model: The impact on behavior and cell survival. J. Neurosurg. 2016, 124, 1829–1841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Reinhart, F.; El Massri, N.; Johnstone, D.M.; Stone, J.; Mitrofanis, J.; Benabid, A.-L.; Moro, C. Near-infrared light (670 nm) reduces MPTP-induced parkinsonism within a broad therapeutic time window. Exp. Brain Res. 2016, 234, 1787–1794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Massri, N.; Johnstone, D.M.; Peoples, C.L.; Moro, C.; Reinhart, F.; Torres, N.; Stone, J.; Benabid, A.-L.; Mitrofanis, J. The effect of different doses of near infrared light on dopaminergic cell survival and gliosis in MPTP-treated mice. Int. J. Neurosci. 2015, 126, 76–87. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- El Massri, N.; Lemgruber, A.P.; Rowe, I.J.; Moro, C.; Torres, N.; Reinhart, F.; Chabrol, C.; Benabid, A.-L.; Mitrofanis, J. Photobiomodulation-induced changes in a monkey model of Parkinson’s disease: Changes in tyrosine hydroxylase cells and GDNF expression in the striatum. Exp. Brain Res. 2017, 235, 1861–1874. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Reinhart, F.; El Massri, N.; Torres, N.; Chabrol, C.; Molet, J.; Johnstone, D.M.; Stone, J.; Benabid, A.-L.; Mitrofanis, J.; Moro, C. The behavioural and neuroprotective outcomes when 670 nm and 810 nm near infrared light are applied together in MPTP-treated mice. Neurosci. Res. 2017, 117, 42–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- El Massri, N.; Cullen, K.M.; Stefani, S.; Moro, C.; Torres, N.; Benabid, A.-L.; Mitrofanis, J. Evidence for encephalopsin immunoreactivity in interneurones and striosomes of the monkey striatum. Exp. Brain Res. 2018, 236, 955–961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, B.; Mitrofanis, J.; Stone, J.; Johnstone, D.M. Remote tissue conditioning is neuroprotective against MPTP insult in mice. IBRO Rep. 2018, 4, 14–17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- O’Brien, J.A.; Austin, P.J. Effect of Photobiomodulation in Rescuing Lipopolysaccharide-Induced Dopaminergic Cell Loss in the Male Sprague–Dawley Rat. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 381. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miguel, M.S.; Martin, K.L.; Stone, J.; Johnstone, D.M. Photobiomodulation Mitigates Cerebrovascular Leakage Induced by the Parkinsonian Neurotoxin MPTP. Biomolecules 2019, 9, 564. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ganeshan, V.; Skladnev, N.V.; Kim, J.Y.; Mitrofanis, J.; Stone, J.; Johnstone, D.M. Pre-conditioning with remote photobiomodulation modulates the brain transcriptome and protects against MPTP insult in mice. Neuroscience 2019, 400, 85–97. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Langston, J.W.; Palfreman, J. The Case of the Frozen Addicts: How the Solution of a Medical Mystery Revolutionized the Understanding of Parkinson’s Disease; IOS Press: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2014. [Google Scholar]

- Gubellini, P.; Kachidian, P. Animal models of Parkinson’s disease: An updated overview. Rev. Neurol. 2015, 171, 750–761. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bezchlibnyk, Y.B.; Sharma, V.D.; Naik, K.B.; Isbaine, F.; Gale, J.T.; Cheng, J.; Triche, S.D.; Miocinovic, S.; Buetefisch, C.M.; Willie, J.T.; et al. Clinical outcomes of globus pallidus deep brain stimulation for Parkinson disease: A comparison of intraoperative MRI- and MER-guided lead placement. J. Neurosurg. 2020. Online ahead of print. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Jorge, A.; Dastolfo-Hromack, C.; Lipski, W.J.; Kratter, I.H.; Smith, L.J.; Gartner-Schmidt, J.L.; Richardson, R.M. Anterior Sensorimotor Subthalamic Nucleus Stimulation Is Associated With Improved Voice Function. Neurosurgery 2020, 2020, nyaa024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sandstrom, L.; Blomstedt, P.; Karlsson, F.; Hartelius, L. The Effects of Deep Brain Stimulation on Speech Intelligibility in Persons With Essential Tremor. J. Speech, Lang. Hear. Res. 2020, 63, 456–471. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ando, T.; Xuan, W.; Xu, T.; Dai, T.; Sharma, S.K.; Kharkwal, G.B.; Huang, Y.Y.; Wu, Q.; Whalen, M.J.; Sato, S.; et al. Comparison of therapeutic effects between pulsed and continuous wave 810-nm wavelength laser irradiation for traumatic brain injury in mice. PLoS ONE 2011, 6, e26212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hamilton, C.; Hamilton, D.; Nicklason, F.; el Massri, N.; Mitrofanis, J. Exploring the use of transcranial photobiomodulation in Parkinson’s disease patients. Neural Regen. Res. 2018, 13, 1738–1740. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Santos, L.; Olmo-Aguado, S.D.; Valenzuela, P.L.; Winge, K.; Iglesias-Soler, E.; Arguelles-Luis, J.; Alvarez-Valle, S.; Parcero-Iglesias, G.J.; Fernandez-Martinez, A.; Lucia, A. Photobiomodulation in Parkinson’s disease: A randomized controlled trial. Brain Stimul. 2019, 12, 810–812. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

© 2020 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (http://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).