Abstract

We study the conditions under which momentum-space equal-time correlators of scalar fields are finite in flat space. We identify cases where these correlators can be divergent even after renormalization, and we provide sufficient criteria for their existence. Concrete examples are discussed, including the well-known model, composite operators, and effective field theories.

1. Introduction

It is widely believed that, at its very beginning, the universe underwent a phase of rapid expansion known as inflation. Describing the physics of inflation requires an understanding of quantum field theory on a de Sitter background, a task that has received significant attention since the seminal work [1]. In particular, cosmological correlators have recently attracted considerable interest [2,3,4,5,6,7,8,9,10,11,12,13,14,15,16,17,18,19,20,21,22,23,24,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34]. The goal of this program is to compute n-point correlation functions in a de Sitter background [35,36].

An especially powerful tool for this purpose is the Wavefunction of the Universe [5,6,35,37], see also [7,9,11,12,38,39,40,41,42,43]. A key feature of this approach is that, while it avoids the more cumbersome computations of the in-in Schwinger-Keldysh formalism [28,44,45,46,47], it most naturally provides access to equal-time correlators. Indeed, even the in-in formalism is often specialized to the computation of equal-time correlators.

The purpose of this work is to critically examine the existence of these equal-time correlators in quantum field theory.

Among recent developments in the study of cosmological correlators, we note that the analogs of the Cutkosky cutting rules and the optical theorem have been formulated for de Sitter, and more generally FLRW backgrounds, in [7,9,11,12,41,43,48] within the Wavefunction of the Universe framework, yielding results valid to all loop orders. On the fully non-perturbative side, we highlight the formulation of the Källén-Lehmann representation for deSitter [29,49,50], the Reeh–Schlieder theorem [51], and a discussion of the spectral condition [52].

We examine equal-time correlators, for which UV divergences are often left unrenormalized, with an explicit cutoff retained in the final result (see, however, [28,45,46,53,54,55] for works that do implement renormalization). In Section 2, we show on general grounds that computing correlators at exactly equal times can produce divergences even for renormalized fields at loop level, making the removal of the UV regulator problematic in general. The core issue is that quantum fields, which are operator distributions, do not in general admit a restriction to a space-like hypersurface. We first present a necessary and sufficient condition for the finiteness of the equal-time 2-point function, and then show how from the existence of the equal-time 2-point function we can bootstrap the existence of equal-time n-point functions. Since our focus is solely on UV divergences, we restrict the discussion to flat space, where both the theoretical framework and computations are more developed, under the expectation that the UV behavior of correlators should be similar to that in de Sitter space. In Section 3, we give explicit computations in flat space to illustrate how these divergences arise in perturbative calculations, including examples involving composite operators and non-renormalizable theories.

While the goal of the program is to ultimately take the limit of cosmological correlators as , this limit can be non-trivial [56,57,58,59,60,61,62,63,64,65,66]. To simplify the discussion, we restrict our attention to finite t and . For concreteness, we also focus on massive scalar fields, although the extension to higher-spin fields is conceptually straightforward. The mass acts as an IR regulator but otherwise plays no role in the analysis.

Notation

We denote bare fields with a subscript 0, while renormalized fields are denoted by a subscript R, or no subscript at all. For equal-time correlators, we indicate the identical time t as . By , we mean the correlator without the overall or momentum conserving delta function, depending on context. Except for Section 2, we will leave the time ordering symbol implicit in the correlators.

We will begin by showing a very simple example, rooted in perturbative quantum field theory, of pairs of operators whose 2-point correlation function cannot admit an equal-time restriction.

2. General Arguments

A central problem in quantum field theory is to give a precise meaning to the equations governing the dynamics of the Heisenberg fields . Perturbative quantum field theory attempts to solve this problem by introducing the interaction picture fields , where U is unitary and are fields obeying the canonical commutation relations. However U, can only exist if a cutoff is imposed (Haag’s theorem). The limit where the regulator is removed would be singular for bare fields , but can instead be obtained after an appropriate rescaling inside correlation functions

where is the wavefunction renormalization (singular as ) and are called renormalized fields. From here on we will refer to the bare fields as , to the renormalized fields as or and to as Z.

This short review clarifies that bare fields obey equal-time canonical commutation relations at finite cutoff, because they are unitarily equivalent to the canonical fields

where we focused on theories without derivative interactions for simplicity, so that the canonical momentum is . As a consequence, the rescaled renormalized fields obey

where diverges as we remove the regulator, except for free theories where . Thus either or (in fact both) must be divergent, providing a first example of pairs of renormalized fields whose correlation function is divergent at equal times.

Before proceeding, it is worth stopping and clarify why one should be concerned with the singularities of Z but not with those of . For this purpose, it is worth recalling that smeared correlation functions

are supposed to give finite values [67,68]. The , called test functions, are functions of spacetime of rapid decrease at infinity. Before this smearing, the correlator is a distribution in each of the spacetime variables, and it is not clear a priori that such a distribution admits a restriction where all times are identical. Free fields can be shown to admit this restriction, and the distributional nature of in Equation (2) should not worry us because it gets regulated by the test functions. On the contrary, Equation (3) can be taken as an example of this restriction not existing in general. Investigating when this restriction exists is one of the main points addressed in this paper. As a side remark, because of spacetime translation invariance only the smearing in the relative coordinates is relevant.

In the remainder of this section, we first describe the condition under which the equal-time 2-point function exists, and guiding the reader’s intuition by interpreting this condition in the context of conformal field theories. We then examine what happens when a time smearing is introduced and subsequently taken to the delta-function limit. Finally, we prove a general result: the finiteness of the equal-time 2-point function is sufficient to guarantee the finiteness of all equal-time n-point functions.

2.1. Discussion of the 2-Point Function

We can discuss the finiteness of the 2-point function at equal times by invoking the Källén–Lehmann representation [68,69] (for now can be either bare or renormalized). Our strategy, which is now fully non-perturbative and independent of the canonical commutation relations, is to take the 2-point function given by the Källén–Lehmann representation, restrict it to equal times and check if the result is still a distribution. This check is performed by smearing in the remaining (space) variables and determining if the result is divergent or not.

We discuss the time ordered correlator, but the result easily translates to Wightman functions.

where D is the Feynman propagator, is the spectral density and is the mass of the intermediate states. We emphasize that this equation is to be understood in the distributional sense: one must first integrate over spacetime against a test function, as in Equation (4), then perform the momentum integral, and only afterwards integrate over .

We will now determine under which conditions the 2-point function with fields at equal times is well-defined, while keeping the smearing in space against a test function . We integrate in the energy by closing the contour in the upper/lower half plane, depending on the sign of , obtaining

If we are interested in the correlator at some assigned momentum , factoring out the momentum conserving function, it is sufficient to remove . The Wightman function would instead be

At equal times, we get a finite 2-point function if and only if

Since the integrand is always positive, we need to ensure convergence in . Recalling as , we arrive at our first result: the equal-time 2-point function is finite if

Up to now our discussion applies for any field and is fully non-perturbative. We now specialize the discussion to the “elementary” fields that appear in the Lagrangian in order to revisit and generalize the argument given in the previous section for commutators: we will demonstrate that the correlator between a renormalized field and its conjugate momentum is divergent at equal times. To this end, it will be convenient to keep the cutoff finite.

Going back to Equations (6) and (7) and working at fixed 3-momentum discarding the momentum conserving delta function, we observe that taking a time derivative of one of the fields worsens convergence, since it brings down an additional factor of . Explicitly,

which could be problematic when , because the rapidly oscillating phase vanishes, giving the integral

To see that this integral is divergent, we will relate it to the well known commutator of bare fields Equation (2).

Given that Equation (10) is the time-ordered correlator, we can take the difference between the limits , and then set to compute the commutator . This computation can be specialized to bare or renormalized fields, giving

The canonical commutation relation between the bare fields and for theories with no derivative interactions ensures that

thus we deduce the integral of the bare spectral density

while the integral of the renormalized spectral density obeys

which diverges as we remove the UV cutoff. This concludes the (perturbative) argument for the divergence of the integral of the spectral density, which can also be checked non-perturbatively in simple models [68].

2.2. Interpretation in a CFT

In this subsection we interpret the condition in Equation (9) for the existence of the equal-time 2-point function by studying the example of an interacting scalar field of dimension in a conformal field theory. The reason why this example is simple is that, from scaling arguments,

so the integral in Equation (9) is convergent if and only if

The same scaling arguments also apply to interacting spinning fields1.

Recall that in Euclidean signature the 2-point function of a scalar field of dimension is

Notice how the only singularity is localized at coincident points. Instead in Lorentzian signature, we get the Wightman 2-point function

where singularities, now spread out on the whole light-cone, are regulated by . The appearance of is most easily understood by looking at Equation (7): the substitution improves the convergence of the integral yielding an analytic function of complex time [67].

We now come to what happens when we consider equal times. The 2-point function becomes

which is finite, except at coincident points. However, to be more precise, Equation (21) is not a distribution in general, unless additional subtractions are performed. To see this, it is sufficient to study the existence of the integral of Equation (21) against a test function in space2. The integral we study is

where we assumed to have non-zero value close to , and then to smoothly decay. The integral is indeed finite if and only if , in agreement with Equation (18).

The same arguments can be repeated for spinning fields. As an application of these ideas, we discuss spin interacting fermions of dimension . The bound in Equation (18) can be combined with unitarity bounds for spinning particles [71], which enforce . Thus, the only fermion fields that admit a sharp time restriction are free fermions because they do not have a spectral density obeying Equation (17). This conclusion was also reached by Wightman [72] by different arguments.

Since the problem we are highlighting has to do with the UV modes of the theory, and given that many quantum field theories are expected to flow to a conformal fixed point in the UV, the computation above actually applies quite generally if is understood as the scaling dimension of the field in the UV. Conformal field theories are also simple enough that we can compute the Wightman 2-point function of a conformally coupled field in de Sitter space. Performing a Weyl transformation on Equation (20) and defining H as the Hubble constant, we get

This expression clarifies that the condition Equation (18), derived for flat space, remains identical in de Sitter. This is not surprising, since divergences in equal-time correlators arise from probing large energies, where the theory is often effectively conformal.

2.3. Time Smearing

We know from the general theory of Wightman QFT that renormalized correlators give finite results when all coordinates are smeared using test functions regular in every space–time variable, as in Equation (4). We can then ask what fails in the limit where the time smearing approaches a sharp function. We will see that time smearing suppresses dangerous UV modes, and this suppression is lost once we take the limit to a function.

To be concrete, we focus on Gaussian smearing for simplicity, noting that the conclusions hold more generally for any test functions supported over a finite time or length scale. We choose the normalized

so that Equation (7) becomes

We stress the order of the integrals in Equation (5): first in against test functions, then in momentum, then in . The integral in gives

up to irrelevant scaleless prefactors, where U is the confluent hypergeometric funtion, which asymptotes to as . The well known sub-exponential growth of , together with the exponential suppression from now ensures the convergence of the integral for any .

We can easily study what happens in the limit in which , i.e., : because the integrand is positive, no non-trivial cancellations can arise. For this reason, we can bring the limit inside the integral and we get

which, recalling the asymptotic behavior of U, is convergent if and only if

in agreement with Equation (9).

2.4. Renormalized Higher Point Functions

The necessary and sufficient condition Equation (9) for the finiteness of the equal-time 2-point function was relatively easy to establish, more so than for higher-point functions, because only in this case do we have access to the Källén–Lehmann representation. Fortunately, the finiteness of the equal-time 2-point function is sufficient to guarantee the finiteness of all equal-time n-point functions. In what follows, we work exclusively with renormalized fields, as they are the only ones that give finite correlation functions when appropriately smeared.

To show this, we will begin by establishing that the field restricted to a sharp time but smeared in space against a test function f

defines a well-behaved operator (not only a distribution) on a dense subspace of the Hilbert space whenever the equal-time 2-point function is finite, a condition which can be checked using Equation (9). To conclude the argument, we will then note that the equal-time n-point function of amounts to the repeated application of the well-defined operator on a state in , so that no divergences can arise.

Argument:

We begin by proving that if the equal-time 2-point function exists, then is a well defined operator. The assumption

can be interpreted as the state having finite norm.

We can always assume that f has support in some finite space region . We now want to determine the matrix elements of itself, and we will do so by considering the braket of with two arbitrary states

By the Reeh–Schlieder theorem,3 any state can be approximated to any precision by acting on the vacuum with field operators localized in an arbitrary compact spacetime region. Let

where is a product of fields smeared in the spacetime region , which we choose to be space-like with respect to every point in at time t. Thanks to the smearing, is not a distribution, but rather a well defined operator on . Then

but from microcausality of the fields, i.e., their commutation at space-like separation, we have

which we can read as the scalar product of two states which are known to be of finite norm: we already proved this for the ket , while the bra is the action of the well defined operator on a well-defined state. Tracing back our steps, the scalar product must be finite by the Cauchy-Schwarz inequality. Having shown that the matrix elements of between two arbitrary states are finite numbers, we deduce that is a well-defined operator, for any compactly supported space test function . These functions are dense in the Schwartz class, so that compact support is not too restrictive.

The final point is the observation that any equal-time vacuum correlation function must exist

because we can read it as repeatedly acting on the vacuum with well-defined operators, to finally project again on the vacuum4. This concludes the proof.

2.5. A Possible Solution

In this section we summarize the situation, draw some conclusions, and propose a possible resolution.

First, in renormalizable theories treated perturbatively, fields without time derivatives admit a sharp time restriction. The reason is that the two-point function must have mass dimension 2, and because there are no couplings with negative mass dimension, the dependence on can only appear linearly and inside logarithms, which more generally amount to , for some number c vanishing with the couplings and the dim-reg regulator. So ultimately the 2-point correlator goes as at large momentum, thus passing the requirement in Equation (9).

More generally, in perturbation theory the mass dimension of every elementary field in the UV is close to that of a free field up to an anomalous dimension , so for scalars the condition Equation (18) is satisfied because if . Non-perturbatively the situation is more delicate, and one should check the anomalous dimension of the field and Equation (9) explicitly. Attempting to impose a sharp-time restriction on time derivatives of fields is generically problematic because they have mass dimension 2 already in the free case, thus violating Equation (18). All these results extend from the 2-point function to any correlator, by the argument given in Section 2.4.

As discussed in Section 2.3, the most straightforward solution is to smear correlators in time (independently for each field), but this approach can be cumbersome. Instead, one can ask how can we make sense of equal-time correlators? From the general Wightman framework [67], these divergences are a distributional issue that arises at coincident points. The assumption of equal times in therefore not strictly enough to obtain infinite results, and indeed Equations (3), (12), (21) and (27) involve either coincident points in space, or test functions with overlapping support, or the related 3-momentum representation (where plane waves are effectively the limit of very delocalized test functions).

As a consequence, one possible strategy is to work in position space rather than 3-momentum space. The resulting correlators are well-defined as long as one never takes a coincident space-point limit.

It is sufficient to put only the external legs of the correlator in position space, so all intermediate computations can still be performed more conveniently in momentum space. Concretely, one can take the momentum-space equal-time correlator computed with a finite UV cutoff, Fourier transform all external legs to position space, and only then remove the UV regulator.

As an example, let us go back to the 2-point function at finite space separation

Notice that the argument given above Equation (9) to show the divergence of this correlator at equal times relied on the positivity of the integrand, which is now missing. Indeed the spatial Fourier transform of is the free propagator at space-like separation, which enjoys a suppression that makes the integral always convergent at separate points. Correlators with enjoy a similar suppression.

3. Examples

This section is devoted to working out some flat space examples in detail. First, we will discuss the prototypical model, checking every statement made on general grounds in the previous section. By checking the behavior of the spectral density of , we will try to elucidate in particular how the equal-time renormalized commutator can be divergent (Equation (3)), while the non-renormalized one remains finite (Equation (2)). We will also check the validity of Equation (9), which was claimed to hold for perturbative scalar fields. We continue in Section 3.2 by considering a composite operator in a free theory, both in flat space and de Sitter. We conclude by briefly discussing effective field theories, where the presence of an EFT cutoff makes an infinitely sharp time localization even more problematic.

3.1. Single Scalar, Model

We now delve more into the details of the above arguments by studying an example. Our aim will be to show that in , despite the divergence of correlation functions in the limit , the commutator of the bare fields is finite at equal times. Additionally, we will show that correlation functions of renormalized fields are divergent when evaluated at equal times. We consider theory

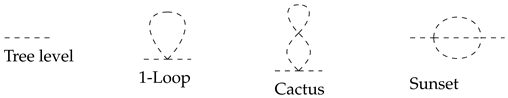

in flat space. It is well known that, in dimensional regularization at two loops, the 2-point function gets contributions from the following diagrams

The resulting 2-point amplitude, defined as the Fourier transform of the 2-point function without the momentum conserving delta function, is

where is the dimensional regularization mass scale, and the Feynman prescription can be implemented by giving a small negative imaginary part to . The renormalization constants at order in MS scheme are

The 2-point correlator is

where the prescription was made explicit.

To compute equal-time correlators, we now go from energy to time domain

For most of the terms in , the integration is straightforwardly performed. The tree level contribution is , and it gives rise to the correct equal-time commutation relation . All higher order contributions to are expected to vanish at equal times. The 1-loop and cactus diagrams contribute with terms proportional to

where the coefficients contain poles. When taking to compute the contribution to the equal-time commutator, we get zero as expected. Finally, the sunset term containing the functions has branch cuts, making its evaluation non-trivial, and the cancellation of its contribution will be shown in Appendix A. This shows that the bare field satisfied canonical commutation relations at equal times, as assumed in Equation (2).

The computation above suffices to show that at equal times, but it is also interesting to check the integrals of and , where here is not to be confused with the dim-reg mass scale (subsequently named whenever confusions may arise). Following the general strategy discussed in Section 2.1, we extract the spectral density from in Equation (40), bypassing the need to go to time domain. This is easily done because

where P indicates the principal part, so

The tree level term gives the expected function centered on the particle mass, while all other terms except for the sunset contribution immediately give zero. For the sunset, in addition to picking up the residue at the pole , we also get a term from the cut when the energy is above threshold (). Using

we get

where is the Heaviside step function. The contribution has a pole, readily evaluated to be as expected to reproduce the singular part of the counterterm. The cut contribution does not have poles: to show this, notice the y domain of integration is restricted to be always a finite distance away from 0 by the function, thus the factor cannot give a singularity as . Despite this, we cannot neglect the cut contribution because, as we will see, it will give a pole when we will consider the integral of . For this purpose, it will be sufficient to evaluate the cut contribution in the limit of large , where we obtain

where we dropped terms in the coefficient of , while the second term is approximated to leading order in large . We can now check that

and the divergence canceled, as announced in Equation (15). Notice the need to keep finite when it sits at the exponent of : expanding into logarithms is valid for all finite momenta as , but here we are checking a delicate ultraviolet property of the bare fields.

We now discuss the renormalized correlator. The mass is renormalized by , leading to inside all formulas. Similarly, since enters our formulas only as , we can set up to higher loop corrections. Finally Z rescales and . As claimed in Section 2.1,

The integral is now UV divergent, and the divergence is precisely the one predicted in Equation (16). This also means that the correlator Equation (12) is divergent. On the other hand, the condition in Equation (9) is satisfied even as , indicating that the equal-time correlator exists. This is in agreement with the previous observation that the mass dimension of fields in perturbation theory is close to 1, hence satisfying Equation (18).

3.2. Composite Operator In a Free Scalar Theory

As pointed out in Equation (18), the condition in Equation (9) is not satisfied for CFT operators of dimension , indicating for example that in a free scalar theory should not admit a sharp time restriction because its mass dimension is . We verify this in this subsection5. We suppress all time dependencies from operators and correlators, always working at fixed equal time.

We begin by observing that

where we separated the internal momentum and the centre of mass momentum. In momentum space, we can then define as

Recall from Equation (6) applied to a free theory that

so

It is readily observed, from as , that the last integral is linearly divergent. We stress that this happens despite normal ordering, which already subtracted all unphysical divergences and made a well-defined operator when suitably smeared against test functions of space-time: the problem lies entirely in forcing the correlator to be at equal times in 3-momentum space. As mentioned at the end of Section 2.2, the divergence is absent in position space for distinct points at equal times, because clearly

This example with is simple enough that it can be easily studied even in de Sitter. For simplicity, we restrict to the frequently studied case of a conformally coupled scalar field, with no interactions. Since we only used translational invariance, the whole discussion above still applies except that the 2-point function for the elementary field now is

so that

It is straightforward to see that the UV behavior of the integrand is the same, as one might have expected. Thus the same problem can also affect de Sitter correlation functions.

3.3. Light Scalar, Heavy Scalar

Renormalizable theories such as the model discussed in Section 3.1 are in principle valid up to arbitrarily large energies (aside for the Landau pole). On the contrary, effective field theories (EFTs), due to the higher dimensional operators in their lagrangians, stop making sense at energies above their cutoff, prompting the question of what happens to the divergences in sharp time correlators in this context.

The first general point is that the argument given in Section 2.5, according to which scales as at large momentum, does not hold. We will now work through an explicit example to show that higher derivative terms, generic in an EFT Lagrangian, spoil the existence of sharp time restrictions of fields even in perturbation theory, making correlation functions divergent in 3-momentum space. Next, we will show that a resummation of diagrams can give finite results in specific cases, which however are hard to interpret physically because of the appearence of spurious contributions. Indeed, while in renormalizable theories only coincident points are problematic at equal times, we will see in Equation (65) that in theories with a cutoff any time localization more precise than , as one might expect, is problematic.

Consider a model consisting of a light scalar and a heavy scalar 6, coupled together

At energies much below M, is described by the effective lagrangian

where the dots encapsulate all higher order operators, which can be fixed by imposing matching conditions between and . In particular, higher derivative operators like (schematically) appear in .

We will now show from a top-down computation that such terms proportional to dominate the high-energy limit of the 2-point function , computed to some finite order in g and . These terms will be important in what follows.

In the UV theory, the 2-point function of at 1 loop (in after renormalization) is

The term dominates the 2-point function if we (illegitimately) extrapolate the theory up to large momenta.

We are now presented with a choice. We can either discuss the 2-point correlator to order , or we can resum the geometric series of 1-PI diagrams and study .

3.3.1. Leading Terms

In the first case the 2-point correlator is

Due to the term, which dominates at large energies, the second part of the integrand gives a divergent contribution. This is to be contrasted with the example presented in Section 3.1, where the equal-time correlator existed. More generally, the presence of a term is only possible in a non-renormalizable theory, on dimensional grounds.

If we were to introduce a time smearing that cuts off frequencies higher than , the correlator Equation (60) would get a contribution proportional to , thus linearly divergent when the smearing is removed. This divergence signals a sensitivity of the result on the effective UV cutoff introduced by the smearing, which is hardly acceptable in an EFT.

3.3.2. Resummed Series

The above treatment might seem a bit naive because usually we think of inverting to determine the 2-point correlator, which corresponds to resumming the geometric series of 1PI 2-point diagrams. We should then discuss

directly. To simplify the notation, let us define such that in Equation (59) can be expressed as

The integrand now has 4 poles, and in particular we can write

which makes manifest the presence of an unphysical degree of freedom because of the negative kinetic and mass terms.

Reintroducing , the integral in Equation (61) can now be trivially performed resulting in , which is the sum of simple free propagators. In particular, the mass squared b is negative, leading to

which is a spurious contribution of the same order as the terms we kept in the EFT lagrangian. Going back to the idea of introducing a time smearing that cuts off frequencies above , we see that a reasonable consistency requirement we should impose is that the unphysical mass squared b should be much larger than the smearing cutoff , leading to

which is the simple statement that the energies we consider should be well below the strong coupling scale. The conclusion is that any time localization sharper than the EFT cutoff is illegitimate.

4. Conclusions

In this paper, we examined the existence of sharp time restrictions for quantum fields, required to compute correlators of fields at equal time. This seemingly harmless assumption was shown to be a priori problematic. This is to be contrasted with the usual correlators expressed in terms of energy (instead of time) and 3-momentum, where this problem does not exist. These considerations could cast doubt on the validity of any method that attempts to compute correlators at equal times. We were therefore prompted to determine under which conditions the sharp time restriction is valid.

Fortunately, the condition we found in Equation (9) for elementary scalar fields, which was reduced in Equation (18) to the check that the UV mass dimension of the field should be at most , is verified for free theories as well as scalar theories treated perturbatively. This check, while only guaranteeing the existence of the 2-point function, extends to all n-point correlators thanks to the argument given in Section 2.4. Computations of equal-time correlators are then completely fine to all loop orders for elementary scalar fields. However, it is not hard to construct simple examples where equal-time correlation functions are ill-defined: we showed how divergences can arise both in the presence of time derivatives and composite operators, even for very well known theories like . Such divergences typically only appear at two loops, which is more than what generally considered for cosmological correlators.

While we only focused on scalar fields for simplicity, extensions to spinning fields are straightforward. For spin fields for example, an analogue of the divergences we found for could be the non-canonical terms that Schwinger discovered [74] in current commutators, which make sharp time restrictions of the electric current ill-defined already in a free theory (see [68] for a review). This example is instructive because it shows that even current commutators might not be finite at equal times, despite the role of conserved currents as symmetry generators (see [68] for a solution to this problem, involving a time smearing).

The divergences we discussed only arise in the coincident space-point limit of the equal-time correlators, so a strategy to obtain a finite result could be to work in position rather than 3-momentum space, at the price of obscuring the overall 3-momentum conservation. For effective field theories this strategy, while formally working, is not free of issues because the infinite time localization requires that we know the correlation function at energies well above the EFT cutoff.

Finally, we draw some conclusions regarding cosmology. The first point is that our arguments only apply to IR finite correlators at finite (and equal) conformal time . This is because the more physically interesting late time limit could also be achieved by computing the correlator at different for each operator , and then sending each to zero independently. It is then unclear whether removing the UV cutoff after taking in an equal-time correlator could give the correct result. However, we notice that this late time limit sometimes cannot be taken directly, either because the correlator would vanish Equation (23) or because of infrared divergences.

Secondly, although much of our discussion was carried out in flat space, we expect many of our results to carry over to de Sitter since we were always concerned with UV properties of the correlators, which should be robust under IR deformations of the spacetime and operators like the Riemann tensor getting a vacuum expectation value. We also highlight that many of our arguments employed tools, like the Källén–Lehmann representation or the Reeh–Schlieder theorem, which have been successfully carried over to de Sitter [29,49,50,51], further closing the gap between this work and the more interesting cosmological scenario.

Similarly, while in cosmology we are interested in in–in rather than in–out correlators, we do not expect significant deviations because in flat space the two correlators coincide.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The author would like to thank Manuel Loparco, Ugo Moschella, Enrico Pajer, Guilherme Pimentel and the participants of the Cosmological Correlators Workshop in Cortona for useful discussions. The author also expresses his gratitude to Franco Strocchi for useful discussions, especially regarding Section 2.4, and for his courses on quantum field theory.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares no conflicts of interest.

Appendix A. Sunset Diagram

The contribution of the sunset diagram to in theory is

and the goal of this appendix will be to Fourier transform this quantity to time domain

What is the analytic structure of in the complex E plane? There are two poles at , and from the definitions of , in Equation (38) we see two branch cuts emanating from values of E given by (see the definition of in Equation (38))

These branch points are symmetric with respect to the origin of the complex E plane, and the one with negative real part has a small positive imaginary part.

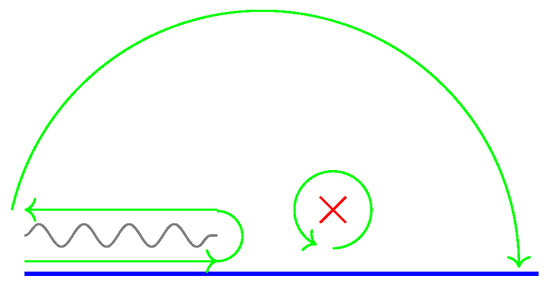

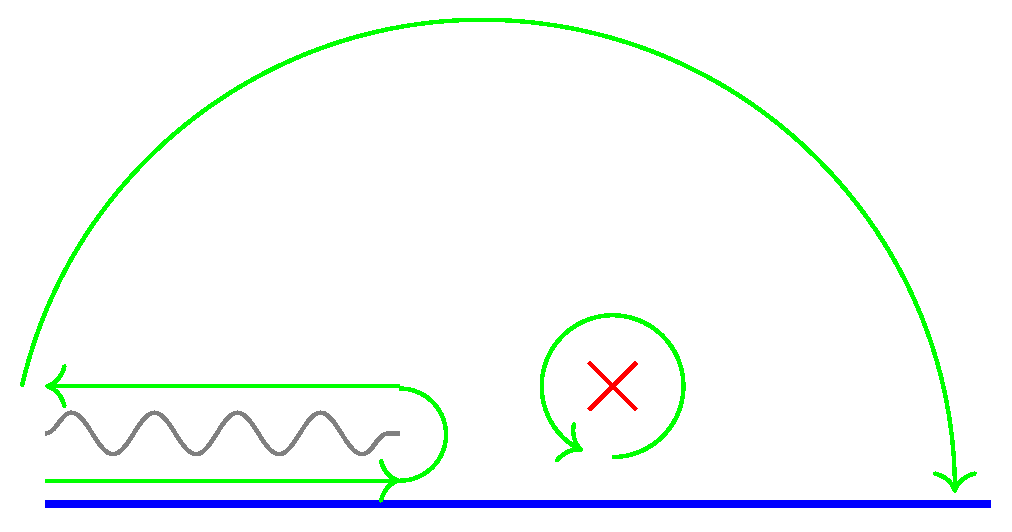

When , we can close the contour of Equation (A2) in the upper half plane, picking up the energy pole. To fully close the contour, however, we have to go around the cut and account for its contribution. The end result is described in Figure A1, so we have to evaluate the cut and the pole contributions separately.

Figure A1.

Evaluation of the sunset diagram in theory. We display the upper complex E plane. The real line, in blue, is the integration domain, while the red cross is the pole. When in Equation (A2), the integration domain can be deformed to the green lines.

Figure A1.

Evaluation of the sunset diagram in theory. We display the upper complex E plane. The real line, in blue, is the integration domain, while the red cross is the pole. When in Equation (A2), the integration domain can be deformed to the green lines.

The pole contributes, up to terms, as

The contribution to at equal times then comes only from , to leading order in , and it is

The cut can be handled recalling

so that the discontinuity along the cut is . Then the cut contributes as

where the integration domain is first restricted to to discard the other cut, and then the function selects the correct half-line, whose origin is dependent.

The reader should notice that the pole from cancels against the coming from the discontinuity; moreover the integral cannot give a divergence as , because the dangerous point is never part of the integration domain for any finite .

Thus, we can extract the leading behavior of the integral by taking inside the integrand, except for the factor which depends on . Focusing on the leading behavior, we get

while the contribution to at equal times is

To evaluate the correlator for we would close the contour in the lower half E plane, obtaining completely analogous results. Indeed the equal-time cut and pole contributions are opposite to the ones obtained here for , so we simply double them when considering the commutator. This implies that for bare fields at equal-times , so the pole cancels, while for the renormalized fields at equal times

as expected.

Notes

| 1 | Free fields have a delta function spectral density, in contrast with Equation (17), so they evade the bound. Indeed free fermions have while allowing equal-time correlators. |

| 2 | See for example [70], pp. 25, 28, for a brief discussion of test functions. |

| 3 | See [67,68] for discussions of the theorem and its applications. |

| 4 | This discussion neglects possible domain subtleties associated with non-compact operators, effectively identifying a state and an arbitrarily close approximation of it. |

| 5 | See [73] for the same computation together with the 2-point function of the stress energy tensor. |

| 6 | This model was chosen to avoid the appearence of logarithms in Equation (62), which makes the subsequent discussion simpler while illustrating the main point. |

References

- Mukhanov, V.F.; Chibisov, G.V. Quantum Fluctuations and a Nonsingular Universe. JETP Lett. 1981, 33, 532–535. [Google Scholar]

- Flauger, R.; Gorbenko, V.; Joyce, A.; McAllister, L.; Shiu, G.; Silverstein, E. Snowmass White Paper: Cosmology at the Theory Frontier. arXiv 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkani-Hamed, N.; Benincasa, P.; Postnikov, A. Cosmological Polytopes and the Wavefunction of the Universe. arXiv 2017. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bzowski, A.; McFadden, P.; Skenderis, K. Conformal correlators as simplex integrals in momentum space. J. High Energy Phys. 2021, 2021, 192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkani-Hamed, N.; Maldacena, J. Cosmological Collider Physics. arXiv 2015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Arkani-Hamed, N.; Baumann, D.; Lee, H.; Pimentel, G.L. The Cosmological Bootstrap: Inflationary Correlators from Symmetries and Singularities. J. High Energy Phys. 2020, 2020, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meltzer, D. The inflationary wavefunction from analyticity and factorization. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2021, 2021, 18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleight, C. A Mellin Space Approach to Cosmological Correlators. J. High Energy Phys. 2020, 2020, 90. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodhew, H.; Jazayeri, S.; Pajer, E. The Cosmological Optical Theorem. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2021, 2021, 21. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Benincasa, P.; McLeod, A.J.; Vergu, C. Steinmann Relations and the Wavefunction of the Universe. Phys. Rev. D 2020, 102, 125004. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jazayeri, S.; Pajer, E.; Stefanyszyn, D. From locality and unitarity to cosmological correlators. J. High Energy Phys. 2021, 2021, 65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lee, M.H.G. From amplitudes to analytic wavefunctions. J. High Energy Phys. 2024, 2024, 58. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farrow, J.A.; Lipstein, A.E.; McFadden, P. Double copy structure of CFT correlators. J. High Energy Phys. 2019, 2019, 130. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, C.; Lipstein, A.E.; Mei, J. Color/kinematics duality in AdS4. J. High Energy Phys. 2021, 2021, 194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Albayrak, S.; Kharel, S.; Meltzer, D. On duality of color and kinematics in (A)dS momentum space. J. High Energy Phys. 2021, 2021, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jain, S.; John, R.R.; Mehta, A.; Nizami, A.A.; Suresh, A. Double copy structure of parity-violating CFT correlators. J. High Energy Phys. 2021, 2021, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herderschee, A.; Roiban, R.; Teng, F. On the differential representation and color-kinematics duality of AdS boundary correlators. J. High Energy Phys. 2022, 2022, 26. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cheung, C.; Parra-Martinez, J.; Sivaramakrishnan, A. On-shell correlators and color-kinematics duality in curved symmetric spacetimes. J. High Energy Phys. 2022, 2022, 27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Armstrong, C.; Goodhew, H.; Lipstein, A.; Mei, J. Graviton trispectrum from gluons. J. High Energy Phys. 2023, 2023, 206. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mei, J. Amplitude Bootstrap in (Anti) de Sitter Space And The Four-Point Graviton from Double Copy. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gomez, H.; Jusinskas, R.L.; Lipstein, A. Cosmological Scattering Equations. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2021, 127, 251604. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sleight, C.; Taronna, M. Bootstrapping Inflationary Correlators in Mellin Space. J. High Energy Phys. 2020, 2020, 98. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bzowski, A.; McFadden, P.; Skenderis, K. Holography for inflation using conformal perturbation theory. J. High Energy Phys. 2013, 2013, 47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bzowski, A.; McFadden, P.; Skenderis, K. Implications of conformal invariance in momentum space. J. High Energy Phys. 2014, 2014, 111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bzowski, A.; McFadden, P.; Skenderis, K. Renormalised 3-point functions of stress tensors and conserved currents in CFT. J. High Energy Phys. 2018, 2018, 153. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bzowski, A.; McFadden, P.; Skenderis, K. Renormalised CFT 3-point functions of scalars, currents and stress tensors. J. High Energy Phys. 2018, 2018, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckelbacher, T.; Sachs, I. Loops in dS/CFT. J. High Energy Phys. 2021, 2021, 151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Heckelbacher, T.; Sachs, I.; Skvortsov, E.; Vanhove, P. Analytical evaluation of cosmological correlation functions. J. High Energy Phys. 2022, 2022, 139. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cacciatori, S.L.; Epstein, H.; Moschella, U. Loops in de Sitter space. J. High Energy Phys. 2024, 2024, 182. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhowmick, S.; Ghosh, D.; Ullah, F. Bispectrum at 1-loop in the Effective Field Theory of Inflation. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodhew, H.; Thavanesan, A.; Wall, A.C. The Cosmological CPT Theorem. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werth, D.; Pinol, L.; Renaux-Petel, S. Cosmological Flow of Primordial Correlators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 2024, 133, 141002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pinol, L.; Renaux-Petel, S.; Werth, D. The Cosmological Flow: A Systematic Approach to Primordial Correlators. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Werth, D. Spectral Representation of Cosmological Correlators. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maldacena, J.M. Non-Gaussian features of primordial fluctuations in single field inflationary models. J. High Energy Phys. 2003, 2003, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weinberg, S. Quantum contributions to cosmological correlations. Phys. Rev. D 2005, 72, 43514. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hartle, J.B.; Hawking, S.W. Wave Function of the Universe. Phys. Rev. D 1983, 28, 2960–2975. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Céspedes, S.; Davis, A.C.; Melville, S. On the time evolution of cosmological correlators. J. High Energy Phys. 2021, 2021, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifacio, J.; Pajer, E.; Wang, D.G. From amplitudes to contact cosmological correlators. J. High Energy Phys. 2021, 2021, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bonifacio, J.; Goodhew, H.; Joyce, A.; Pajer, E.; Stefanyszyn, D. The graviton four-point function in de Sitter space. J. High Energy Phys. 2023, 2023, 212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Goodhew, H.; Jazayeri, S.; Lee, M.H.G.; Pajer, E. Cutting cosmological correlators. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2021, 2021, 3. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hillman, A.; Pajer, E. A differential representation of cosmological wavefunctions. J. High Energy Phys. 2022, 2022, 12. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Melville, S.; Pajer, E. Cosmological Cutting Rules. J. High Energy Phys. 2021, 2021, 249. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, X.; Wang, Y.; Xianyu, Z.Z. Schwinger-Keldysh Diagrammatics for Primordial Perturbations. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2017, 2017, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chowdhury, C.; Lipstein, A.; Mei, J.; Sachs, I.; Vanhove, P. The Subtle Simplicity of Cosmological Correlators. arXiv 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Beneke, M.; Hager, P.; Sanfilippo, A.F. Cosmological correlators in massless ϕ4-theory and the method of regions. J. High Energy Phys. 2024, 2024, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donath, Y.; Pajer, E. The in-out formalism for in-in correlators. J. High Energy Phys. 2024, 2024, 64. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baumann, D.; Chen, W.M.; Duaso Pueyo, C.; Joyce, A.; Lee, H.; Pimentel, G.L. Linking the singularities of cosmological correlators. J. High Energy Phys. 2022, 2022, 10. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bros, J.; Moschella, U.; Gazeau, J.P. Quantum field theory in the de Sitter universe. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1994, 73, 1746–1749. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Loparco, M.; Penedones, J.; Salehi Vaziri, K.; Sun, Z. The Källén-Lehmann representation in de Sitter spacetime. J. High Energy Phys. 2023, 2023, 159. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bros, J.; Moschella, U. Two point functions and quantum fields in de Sitter universe. Rev. Math. Phys. 1996, 8, 327–392. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moschella, U. The Spectral Condition, Plane Waves, and Harmonic Analysis in de Sitter and Anti-de Sitter Quantum Field Theories. Universe 2024, 10, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senatore, L.; Zaldarriaga, M. On Loops in Inflation. J. High Energy Phys. 2010, 2010, 8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negro, A.; Patil, S.P. An Étude on the regularization and renormalization of divergences in primordial observables. Riv. Nuovo Cim. 2024, 47, 179–228. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Negro, A.; Patil, S.P. Hadamard Regularization of the Graviton Stress Tensor. arXiv 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Seery, D. Infrared effects in inflationary correlation functions. Class. Quant. Grav. 2010, 27, 124005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bros, J.; Epstein, H.; Moschella, U. Particle decays and stability on the de Sitter universe. Ann. Henri Poincare 2010, 11, 611–658. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Burgess, C.P.; Holman, R.; Leblond, L.; Shandera, S. Breakdown of Semiclassical Methods in de Sitter Space. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2010, 2010, 17. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Giddings, S.B.; Sloth, M.S. Semiclassical relations and IR effects in de Sitter and slow-roll space-times. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2011, 2011, 23. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Senatore, L.; Zaldarriaga, M. On Loops in Inflation II: IR Effects in Single Clock Inflation. J. High Energy Phys. 2013, 2013, 109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Akhmedov, E.T.; Moschella, U.; Pavlenko, K.E.; Popov, F.K. Infrared dynamics of massive scalars from the complementary series in de Sitter space. Phys. Rev. D 2017, 96, 25002. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Céspedes, S.; Davis, A.C.; Wang, D.G. On the IR divergences in de Sitter space: Loops, resummation and the semi-classical wavefunction. J. High Energy Phys. 2024, 2024, 4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gorbenko, V.; Senatore, L. λϕ4 in dS. arXiv 2019. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mirbabayi, M. Infrared dynamics of a light scalar field in de Sitter. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2020, 2020, 6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, T.; Green, D. Soft de Sitter Effective Theory. J. High Energy Phys. 2020, 2020, 41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, D.G.; Pimentel, G.L.; Achúcarro, A. Bootstrapping multi-field inflation: Non-Gaussianities from light scalars revisited. J. Cosmol. Astropart. Phys. 2023, 43. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Streater, R.F.; Wightman, A.S. PCT, Spin and Statistics, and All That; Princeton University Press: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Strocchi, F. An Introduction to Non-Perturbative Foundations of Quantum Field Theory; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2013; Volume 158. [Google Scholar]

- Weinberg, S. The Quantum Theory of Fields. Vol. 1: Foundations; Cambridge University Press: Cambridge, UK, 2005. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gillioz, M. Conformal Field Theory for Particle Physicists; SpringerBriefs in Physics; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mack, G. All unitary ray representations of the conformal group SU(2,2) with positive energy. Commun. Math. Phys. 1977, 55, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wightman, A.S. Progress in the foundations of quantum field theory. In Proceedings of the 1967 International Conference on Particles and Fields; Princeton University: Princeton, NJ, USA, 1967. [Google Scholar]

- Yazdi, Y.K. Entanglement Entropy and Causal Set Theory. In Handbook of Quantum Gravity; Springer: Singapore, 2024. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schwinger, J.S. Field theory commutators. Phys. Rev. Lett. 1959, 3, 296–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.