Abstract

Background and Aim: This systematic scoping review examines rabies-related incidents, interventions, and post-exposure immunoprophylaxis in the Arabian Gulf region and Saudi Arabian Peninsula. Methods: A comprehensive literature search was conducted in databases including PubMed, Scopus, WoS, MedLine, and Cochrane Library up to July 2024. Studies were included discussing the reported cases of rabies that received the PEP in all countries of the Arabian Gulf, their epidemiological data, the received schedules of vaccination, and their safety. The search was done by using the following terminologies: rabies vaccine, rabies human diploid cell vaccine, vaccine, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Iraq, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, United Arab Emirates, Southwest Asia, Iran, West Asia, Western Asia, Persian Gulf, Arabian Gulf, Gulf of Ajam, Saudi Arabian Peninsula, and The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia. Results: The systematic scoping review included 36 studies, synthesizing findings from diverse research designs, including large-scale cross-sectional studies and case reports, spanning nearly three decades. Findings indicated that young males in urban areas are most at risk for animal bites, predominantly from domestic dogs and cats. While post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP) was generally administered within recommended timeframes, vaccination completion rates varied. Conclusions: The review highlighted gaps in public awareness about rabies risks and prevention. Vaccine safety profiles were generally favorable, with mostly mild-to-moderate side effects reported. The study underscores the need for enhanced public health education, standardized PEP protocols, and a One Health approach to rabies prevention.

1. Introduction

An estimated 59,000 people die from rabies each year, a deadly illness brought on by the lyssaviruses and the rabies virus (RABV) [1]. Globally, there were 14,075 incident rabies cases and 13,743 deaths in 2019, both of which were lower than in 1990 [2].

Dog bites are the cause of up to 99% of human cases globally [3]. If left untreated, rabies can be lethal and is typically spread to humans and animals by bites, scratches, or contaminated mucus membrane from rabid animals [4,5,6]. Clinical rabies cannot be cured, but it can be easily avoided by giving prompt and sufficient post-exposure prophylaxis (PEP). PEP includes several rabies vaccinations, the delivery of rabies immunoglobulins (RIG), or, more recently, licensed monoclonal antibody products if necessary [7], as well as a thorough wound cleaning with water, detergent, and antiseptics [7]. The PEP approach varies according to the type of exposure, the patient’s immune status, and whether they have received a prior rabies vaccination [8]. A person who has previously had the rabies vaccination, either as part of a comprehensive pre-exposure prophylaxis course or as PEP, is referred to as a previously vaccinated person, per 2010 recommendations. RIG is not advised for individuals who have received rabies vaccinations in the past, even decades ago [7]. Booster shots are the only suggested course of action. They will stimulate the generation of antibodies and elicit an amnestic response.

Depending on the schedule, rabies vaccinations can be given intramuscularly (IM) or intradermally (ID). Since 1992, the World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended intradermal rabies immunization. When used, vaccination costs and doses can be lowered by 60–80%, particularly in high-throughput clinics [9]. The 2010 WHO-recommended vaccination schedules require up to five clinic visits spread over approximately one month to minimize unintended adverse effects [7]. The long duration of immunization can cause people who could be exposed to rabies frequently not to receive the entire course of vaccination, and also cause a change in the route of administration [10].

The largest nation on the Arabian Peninsula is Saudi Arabia, and little information has been released regarding the country’s rabies situation. According to earlier reports, foxes are the primary rabies reservoir and have been implicated in most animal bites that have affected humans, including dogs, cats, rodents, and humans [11,12]. According to recent reports, rabies poses a health concern to humans and animals nationwide and is also thought to be spread by wild canines [13]. In 2007, a study of 4124 camels in the Al Qassim region revealed a clinical rabies incidence of 0.2%, most likely due to wild dogs (70%) and foxes (17%) spreading the disease. In the Al-Qassim region, between 1997 and 2006, the diagnosis of rabies was verified in 26 dogs, 10 foxes, 8 camels, and 7 cats [13]. The Saudi Ministry of Environment, Water, and Agriculture (MEWA) and the Saudi Ministry of Health (MoH) have received reports of 11,069 animal bites on humans between 2007 and 2009. Dogs and cats accounted for 49.5% and 26.6% of all injuries, respectively. Mice and rats (12.6%), camels (3.2%), foxes (1.3%), monkeys (0.7%), and wolves (0.5%) were next in line for injuries, underscoring the significance of animal rabies surveillance and control programs as a critical component of the disease’s prevention [12]. Animal-related injuries continue to be a public health concern in Saudi Arabia, and all countries of the Arabic Gulf, where most human bites are caused by wild dogs, and most rabid animals are located there [12].

Therefore, obtaining more detailed information on the epidemiology of animal rabies in the Arabian Gulf will be essential. In this systematic scoping review, we aim to systematically scope and synthesize the existing literature on rabies PEP protocols, safety outcomes, and public health responses in the Arabian Gulf and Saudi Peninsula, to inform more effective regional strategies aligned with One Health principles.

2. Methods

2.1. Information Sources and Search Strategy

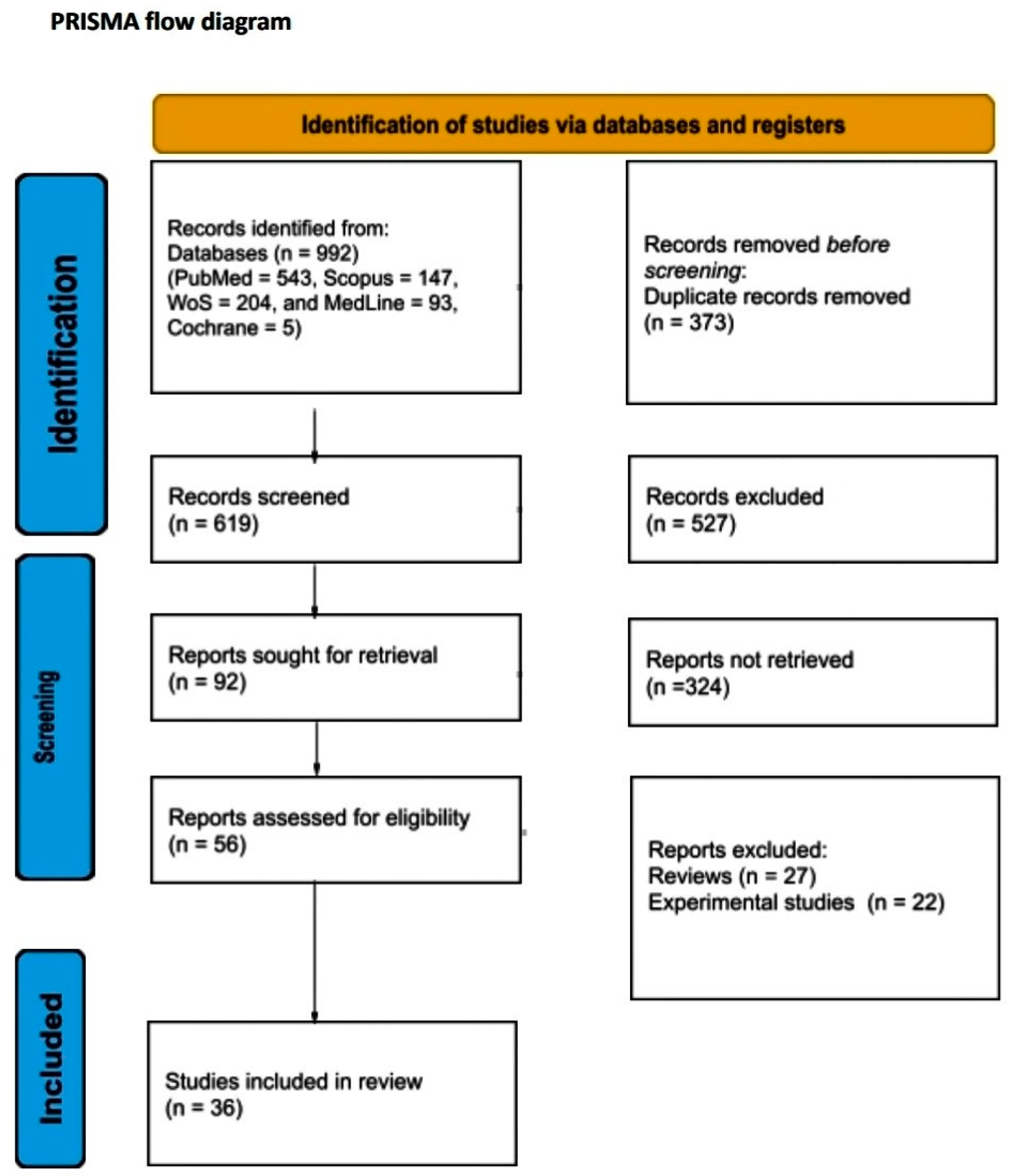

Considering the PRISMA (Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses) extension for scoping reviews, a systematic scoping review of clinical trials was created [14]. More details of the research methodology were provided by the PRISMA checklist (Supplementary File S1). We registered the protocol in PROSPERO, protocol number: CRD420251027233.

Databases from SCOPUS, PubMed, the Web of Science (WoS), Cochrane, and MedLine through WoS were examined up to July 2024. The terminologies rabies vaccine, rabies human diploid cell vaccine, vaccine, Saudi Arabia, Bahrain, Iraq, Kuwait, Oman, Qatar, United Arab Emirates, Southwest Asia, Iran, West Asia, Western Asia, Persian Gulf, Arabian Gulf, Gulf of Ajam, Saudi Arabian Peninsula, The Kingdom of Saudi Arabia, and comparative clinical studies were the terms used to review observational studies in all languages published up to July 2024. Then, we used the Boolean operators AND OR to search all databases. Details of the search strategy are mentioned in Supplementary File S2 (Table S1).

2.2. Eligibility Criteria

Inclusion criteria: Patients who received post-exposure prophylaxis of rabies were included. All types of vaccines were included, such as purified chick embryo cell vaccine (PCECV), purified Vero cell rabies vaccine (PVRV), human diploid cell rabies vaccine (HDCV), and Vero rabies vaccine (PVRV). Prospective or retrospective trials were incorporated, such as randomized controlled trials, observational studies, case reports, case series, cross-sectional studies, or cohort studies. Moreover, we included letters to the editor that published results from clinical trials that met our inclusion criteria. The inclusion of the published studies was limited to the Arabic Gulf countries, Turkey, and Iran only. There was no restriction according to the language of the published trials.

Although Turkey and Iran are not geographically part of the Arabian Gulf or the Saudi Peninsula, their inclusion in this review is justified based on several key factors. Both Turkey and Iran are influential countries in the broader Middle East region, with historical, political, and economic ties to Gulf Cooperation Council (GCC) countries. Their health policies and practices often influence or align with regional trends. High levels of travel, trade, and workforce migration between Turkey, Iran, and Gulf countries facilitate shared public health challenges, including infectious disease control and rabies prevention strategies. Iran and Turkey face similar climatic, ecological, and zoonotic disease patterns, including rabies endemicity, particularly in rural or border areas. Their strategies for PEP, vaccination schedules, and health outcomes offer relevant insights for the Gulf region. Data from many Arabian Gulf countries may be limited due to underreporting or publication gaps. Including data from Iran and Turkey enhances the comprehensiveness of the review by providing comparative regional evidence on vaccine safety, efficacy, and scheduling. Both Iran and Turkey are among the most active countries in the Middle East in terms of biomedical research output. Their inclusion allows the review to incorporate valuable peer-reviewed literature and clinical data that may be applicable or adaptable to the Arabian Gulf context [15,16,17,18].

Exclusion criteria: Experimental studies, animal studies, and case reports of only one case. Additionally, we excluded studies that did not present any data about the status of vaccination for rabies victims.

2.3. Research Questions

This systematic scoping review aims to report the demographic data of the published studies, including rabies cases that received PEP, their vaccination schedule, and the safety of the included vaccines.

2.4. Trial Selection

After reading the abstracts and full texts, certain keywords prompted both researchers to choose the papers. The two researchers used the inclusion criteria to assess the trials. Subsequently, every abstract and full text were downloaded and evaluated independently based on the pre-established inclusion criteria. When there was disagreement among the researchers, the third author assessed the acceptability of the study.

2.5. Data Extraction

Two authors independently reviewed and evaluated each full text that met the inclusion criteria to be included in this systematic scoping review. Each investigator independently created a table that included the most crucial details from the chosen trials, and the outcomes were compared. They extracted the data in three tables: the first was the table of summaries of the included studies, the second was for baseline characteristics of the included patients, and the last was for the safety of the included vaccines.

2.6. Quality Assessment

Two authors independently evaluated the quality of each full text that met the inclusion criteria to be included in this systematic scoping review. The methodological index for non-randomized studies (MINORS) criteria were employed [19]. The maximum score was 24 for the comparative studies. Scores of 0–6 corresponded to very low quality, 7–10 corresponded to low quality, 11–15 corresponded to fair quality, and ≥16 corresponded to high quality.

2.7. Analysis of Outcome Measures

We conducted qualitative analysis by collecting and summarizing the available data from the included studies. Moreover, we summarized the quantitative data using descriptive analysis, providing better representative data. According to quantitative analysis, the contentious variables were represented by median and range, while the binary data were represented by frequency and percentage.

The data extracted from the included studies were analyzed narratively to identify trends and patterns related to rabies PEP and vaccine safety. Given the heterogeneity of study designs and outcomes, we performed a descriptive synthesis to provide an overview of the key findings across different populations, settings, and protocols.

We categorized studies based on key characteristics, such as age group, sex, type of area (urban vs. rural), and animal exposure type (e.g., domestic dogs, cats, and wild animals). These factors were analyzed to explore their relationship with PEP adherence and vaccine safety outcomes.

The timing of PEP initiation, specifically the duration between animal exposure and the administration of prophylactic treatment, was another key factor in the analysis. We examined the proportion of cases that received PEP within 48 h (the recommended timeframe) and compared this across urban and rural settings.

Variations in vaccination regimens, including the number of doses administered (3, 4, or 5 doses), were also examined. This was particularly important in understanding differences in clinical practice.

Data on adverse events related to the rabies vaccination were collated from studies that provided safety data. The analysis focused on the frequency and severity of reported side effects across various vaccine types (e.g., purified chick embryo cell vaccine and purified Vero cell vaccine).

We also analyzed the influence of geographic and ecological factors on rabies exposure. Data from Turkey and Iran, included due to their geographical proximity and similar epidemiological patterns, were integrated to understand the broader regional dynamics. These studies allowed us to explore rabies exposure risks in areas with significant cross-border movement, including the impact of migration and trade on rabies transmission dynamics.

By organizing the data in these thematic categories, we provided a comprehensive narrative synthesis of the epidemiological trends, vaccination practices, and vaccine safety outcomes across different healthcare settings. This analysis offers valuable insights into the effectiveness of PEP strategies and highlights key areas for improvement, particularly in rural settings and in regions with incomplete vaccination practices.

3. Results

3.1. Literature Search

A total of 992 articles from PubMed, Scopus, Web of Science, MedLine, and Cochrane Library were screened. After the removal of duplicates, a total of 619 articles were selected for title and abstract screening. After reviewing the titles and abstracts, 92 articles were selected for full-text review. From these studies, 56 were excluded from the review. Finally, 36 studies met our study’s inclusion criteria. The literature search is graphically represented in the PRISMA flow chart (Figure 1).

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram.

3.2. Study Characteristics

The results present a comprehensive collection of studies on rabies-related incidents and interventions, encompassing various research designs, including one prospective study [20], one randomized controlled trial [21], three case reports [22,23,24], three case series [25,26,27], eighteen cross-sectional studies [15,17,18,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36,37,38,39,40,41,42], and eight retrospective analyses [16,43,44,45,46,47,48,49]. These studies were conducted across multiple countries, with a significant focus on Iran and Turkey, as well as contributions from Lebanon and Saudi Arabia. The research spans a wide timeframe, with studies dating from 1995 to 2024, covering periods ranging from a few months to several years. Collectively, these studies represent a substantial sample size of over 400,000 participants, with individual study samples varying from as few as 2 cases in some reports to as many as 260,470 in large-scale registry-based studies. More details are presented in Table 1.

Table 1.

Summaries of the included studies. Abbreviations—ERIG: equine rabies immunoglobulin, PCECV: purified chick embryo cell vaccine, PVRV: purified Vero cell rabies vaccine, HDCV: human diploid cell rabies vaccine, RVNA: rabies neutralizing antibodies, PVRV: Vero rabies vaccine, and RVCs: rabies vaccination centers.

3.3. Baseline Characteristics

In a comprehensive analysis of various studies on age demographics conducted between 1995 and 2024, it became evident that a wide range of age groups were studied, illustrating the diversity in the population samples. Most bite victims were young, with several studies reporting a higher incidence among males. In Khazaei et al.’s study (2023), the most affected age group was between 16 and 30 years [29], while Rasooli et al. (2020) found that all victims were between 10 and 67 years old [25]. Additionally, Khoubfekr et al. (2024) focused on ages 7 to 12, with a 100% male population [22]. In their study, Davarani et al. (2023) captured the distribution of age groups, prominently noting 65.3% for ages 7–12 years and a 66.5% male population [29]. On the other hand, Kassiri et al. (2018) examined diverse age ranges, with 76.6% male population, featuring categories from 0 to 4 years to above 61 years [35]. Notably, a 24.1% male population was reported by Oztoprak et al. (2021) in the 15-year-old and above age group [43].

Urban areas had a higher prevalence of bite incidents compared to rural areas, as seen in studies by Janatolmakan et al. (2020) and Amiri et al. (2020) [32,33]. This could be attributed to higher population densities and closer interactions with domestic animals in urban settings. These findings highlight the possibility that the remoteness of rural areas from health centers is a factor influencing the rate of receiving vaccinations. In other words, people in rural communities do not seek rabies treatment because of the distance and the perception that the risk of rabies is lower in rural communities.

The summarized data also provided insight into various studies on animal bite incidents, their implications for rabies vaccination, and demographic factors. Across these studies, domestic dogs were the primary animals involved in bite incidents, with cats being the second most common. Rodents, such as hamsters and mice, are considered low risk for rabies transmission due to their small size, susceptibility to fatal injuries during encounters with larger mammals, and lower likelihood of surviving rabies infection long enough to transmit the virus.

The studies revealed that the hands and upper limbs were frequently bitten, especially in cases involving dogs. For instance, Khoubfekr et al. (2024) found that dogs were responsible for all bites, primarily affecting the upper limbs [22], while other studies, such as those by Davarani et al. (2023) and Oztoprak et al. (2021) [28,43], showed that a significant proportion of bites occurred on the hands and lower limbs.

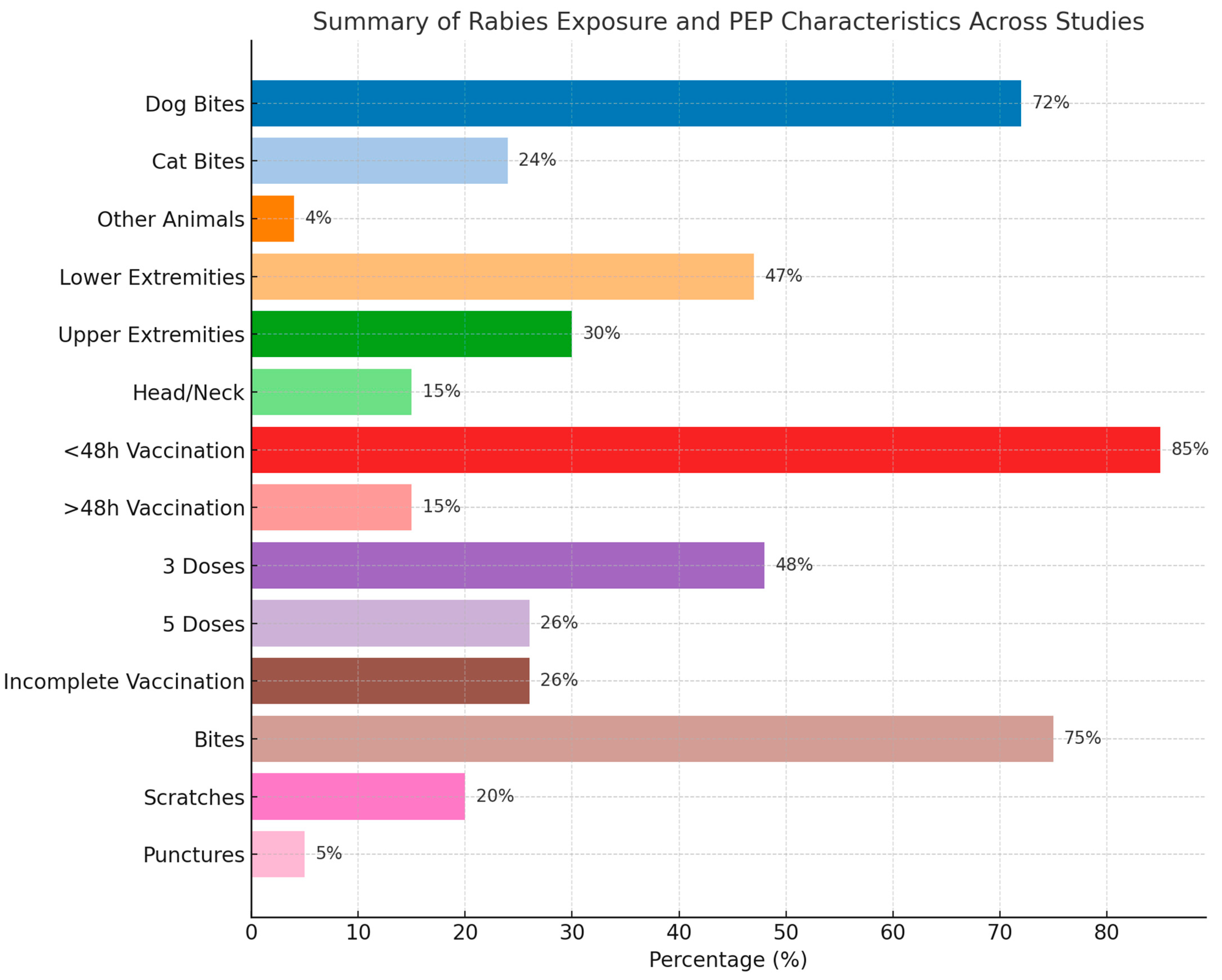

Lastly, in terms of injury type, the majority were punctures and scratches, with a few cases of more severe injuries like bone fractures. For example, Davarani et al. (2023) reported that puncture wounds accounted for 61.4% of injuries, while scratches were 36.9% [28]. The timing of post-exposure prophylaxis varied across studies, with most individuals receiving vaccination within 48 h. For instance, Khazaei et al. (2023) reported that 97.2% of cases received treatment within this timeframe, highlighting the urgency of rabies prevention after a bite [29]. More details are presented in Table 2 and Table S2. A summary of the findings is presented in Table 3 and Figure 2.

Table 2.

Baseline characteristics of the included patients.

Table 3.

Summary of the baseline characteristics of the included patients.

Figure 2.

Summary of the baseline characteristics of the included patients.

3.4. Vaccination Schedules

The results presented a comprehensive overview of rabies PEP practices across various studies conducted primarily in the Persian Gulf countries, with a focus on Iran and Turkey, with participation from Saudi Arabia and Lebanon. The data consistently showed that the majority of patients received rabies vaccination within the first 48 h of exposure, with percentages ranging from 81.14% to 97.20% across different studies. The vaccination protocols typically involved either a 3-dose or 5-dose regimen, with some studies reporting the use of specific vaccines, such as Verorab, purified chick embryo cell vaccine (PCECV, Rabipur), and Vero rabies vaccine (PVRV).

The vaccination regimens varied, with a mix of complete and incomplete vaccination records. For example, Bay et al. (2021) noted that only 12.8% of bite victims received the full four-dose vaccine [15], while a significant portion did not require vaccination. This variability underscores the importance of timely and appropriate post-exposure prophylaxis based on the type and severity of the bite.

In addition to vaccination, many studies report on the administration of rabies immunoglobulin (RIG), with rates varying significantly between studies, ranging from 29.06% to 78.1% of cases. For instance, Rahmanian et al. (2020) reported RIG administration in 29.06% of cases [45], while Can et al. (2020) noted a higher rate of 78.1% [44]. The timing of RIG administration was also highlighted, with Davarani et al. (2023) reporting that 68.9% of patients received RIG within the first 12 h post-exposure [28]. Several studies also mentioned tetanus vaccination and antibiotic prophylaxis as part of the treatment protocol. Notably, some studies, such as Amiri et al. (2015) [37], explored patients’ awareness and reasons for seeking treatment, revealing that only about half of the patients were aware of the need for rabies vaccination after a dog bite, which means gaps in public knowledge about rabies PEP. Overall, the data reflected a general adherence to the WHO guidelines for rabies PEP, with variations in practice across different healthcare settings and regions. More details are presented at Table 2 and Table S2.

3.5. Safety of the Included Vaccines

Seri et al. (2014) [20] compared the safety of two vaccines, Verorab and Abhayrab. Regarding Verorab, the most common side effects were fever (4.99%), weakness (4.99%), headache (3.55%), and local pain (3.02%). On the other hand, the less common side effects were nausea, abdominal pain, and various other mild symptoms. There were no reports of swelling, bruising, insomnia, numbness, irregular menstruation, or decreased libido. Regarding Abhayrab, it generally had a higher incidence of side effects compared to Verorab. The most common side effects were headache (24.78%), fever (15.15%), local swelling (10.28%), and local pain (9.4%). There were higher rates of dizziness, itching, nausea, and other symptoms compared to Verorab.

Ramezankhani et al. (2016) [21] compared PVRV and PCECV.

For PVRV, the most common side effects were local pain (3.9%), fever (1.9%), and headache (1.4%). There were no reports of bruising, itching, or hypotension. On the other hand, the most common side effects of PCECV were local pain (3.8%), bruising (2.5%), and weakness (1.7%), a generally similar side effect profile to PVRV, with some variations (Table 4).

Table 4.

Safety of the included vaccines.

3.6. Quality Assessment

The methodological quality assessment using the MINORS criteria revealed a variable but generally acceptable risk of bias across the 36 included studies. Overall, scores of non-comparative studies ranged from 12 to 15 out of a possible 16 points. The majority of studies scored between 13 and 15 points, suggesting a high quality with low risk of bias.

Overall, scores of the 3 comparative studies ranged from 23 to 24 out of a possible 24 points. The three studies demonstrated high methodological quality, indicating low risk of bias. More details of the assessment of the included studies are presented in Table 5.

Table 5.

Details of the quality assessment of the included studies.

4. Discussion

4.1. Demographics of the Included Patients

This comprehensive review of rabies-related incidents and interventions in the Extended Persian Gulf region, particularly in Iran and Turkey, with contributions from Lebanon and Saudi Arabia, provided valuable insights into the epidemiology of animal bites and the implementation of PEP protocols. The diversity of study designs and settings suggests a comprehensive approach to understanding rabies-related issues in the Extended Persian Gulf countries. The prevalence of cross-sectional and retrospective studies indicates a focus on epidemiological patterns and trends in rabies exposure and treatment. Notable aspects include the presence of several large-scale studies, such as the registry-based cross-sectional study by Khazaei et al. (2023) with 260,470 participants, which likely provides valuable insights into the broader patterns of rabies incidents [29]. Additionally, the inclusion of case reports, particularly those focusing on rare or unique presentations (e.g., Khoubfekr et al., 2024; Ansari et al., 2011), highlights the importance of documenting unusual cases for medical education and awareness [22,23]. The consistent research efforts over nearly three decades demonstrate an ongoing commitment to understanding and addressing rabies-related health concerns in the region.

The studies consistently showed that young males aged 20–39 years are disproportionately affected by animal bites. This trend could be attributed to higher risk-taking behaviors or increased outdoor activities among this demographic, where encounters with animals are more frequent. Meanwhile, children, particularly those aged 0–12 years, showed significant exposure, especially in regions with prevalent stray dog populations, as seen in studies like that of Davarani et al. (2023) [28], who reported 65.3% exposure in 7–12-year-olds. On the other hand, the elderly (60+ years) exhibited lower but still non-negligible exposure, possibly due to reduced mobility or residence in rural areas where animal interactions are more common. These age-related trends highlight the dynamic interplay between lifestyle, geography, and the risk of rabies, stressing the need for targeted interventions across different population groups. The prevalence of bites to the hands and upper limbs indicates a need for public education on proper behavior around animals to minimize such incidents.

The prevalence of bites in urban areas suggests that urbanization may be a factor in human–animal interactions, possibly due to higher population densities and closer proximity to domestic animals. Domestic dogs emerged as the primary culprits in bite incidents, followed by cats. This finding highlights the importance of responsible pet ownership and vaccination programs for domestic animals.

Cases of aggression by rodents, such as hamsters and mice, warrant special consideration in rabies risk assessment. Rodents, particularly small ones, are rarely associated with rabies transmission to humans. This is partly because they typically succumb to the injury from rabid animal attacks, limiting their potential as carriers of the virus. Their ecological role and behavior also contribute to the low transmission risk—rodents are usually prey animals with limited interaction with typical rabies reservoirs, like canines, bats, and other carnivores known to transmit the virus. In discussing cases from studies like those of Rahmanian et al. (2020), Davarani et al. (2023), and Porsuk et al. (2021), public health guidelines often recommend that rodent bites do not typically require PEP unless there are unusual circumstances, such as the animal displaying abnormal behavior or originating from an environment with known rabies outbreaks [22,28,31].

Highlighting these cases also provided an opportunity to discuss regional variations in PEP guidelines. Some regions may advocate a more cautious approach, while others rely on data indicating that rabies transmission from rodents to humans is exceedingly rare. Additionally, these cases allowed us to examine whether any deviations from standard PEP protocols were applied in response to rodent bites and whether additional clinical or observational criteria—such as the aggressor’s health status or species-specific behavior—were considered.

4.2. Protocols of Vaccination

The majority of bite victims received PEP within 48 h of exposure, which aligns with the WHO recommendations for timely intervention. However, the variability in vaccination completion rates highlights a potential area for improvement in patient follow-up and education about the importance of completing the full course of vaccination.

The studies revealed a mix of 3-dose and 5-dose vaccination regimens, reflecting evolving guidelines and potentially differing resources across healthcare settings. The use of specific vaccines, like Verorab, PCECV, and PVRV, indicated adherence to internationally recognized standards for rabies prevention. The wide range in RIG administration rates (29.06% to 78.1%) suggested significant variability in clinical practice or resource availability across different healthcare settings. This disparity warrants further investigation to ensure equitable access to optimal care.

The review highlighted significant variations in clinical practices, especially regarding incomplete immunization in rabies PEP. Studies show that a substantial proportion of patients received incomplete immunization. For instance, Kassiri et al. (2018) reported that approximately 38.6% of patients in their study received a complete vaccine regimen, with the majority (61.4%) receiving incomplete doses [35]. Similarly, a large proportion of cases in Porsuk et al. (2021) and Can et al.’s (2020) studies involved incomplete vaccination protocols [31,44]. Incomplete immunization is a critical concern, as it compromises the effectiveness of rabies prevention, increasing the risk of rabies transmission, particularly in regions with high animal exposure. Addressing this issue in clinical practice requires standardized PEP protocols, improved patient education, and enhanced access to vaccination to ensure timely and complete immunization.

The discrepancies in vaccination completion and RIG use can be attributed to several key factors, including limited access to healthcare services in rural settings, which leads to delays in initiating PEP. Studies like those of Sarbazi et al. (2020) and Poorolajal et al. (2015) showed that rural regions experience significant delays in receiving timely PEP, which can result in incomplete vaccination [40]. Inconsistent application of vaccination protocols contributes to incomplete vaccination regimens. This discrepancy is likely due to differing practices and resources available across regions. In some instances, patients may not complete the full vaccine regimen due to logistical issues or a misunderstanding of the importance of completing the full series.

The need for RIG is a critical component of PEP when the exposure is considered high risk, such as when the bite is from a wild animal or involves multiple puncture sites. Rahmanian et al. (2020) and Davarani et al. (2023) both highlighted how RIG use varies depending on the severity of the injury and the type of animal involved [22,28]. However, the failure to administer RIG in some cases may be linked to limited knowledge or a lack of resources in certain healthcare settings.

Non-adherence to treatment schedules can also be attributed to patient-related factors, such as fear of side effects, misunderstanding the importance of completing the vaccine regimen, or logistical challenges in returning for multiple doses. This was particularly noted in studies such as that of Yıldırım et al. (2022), who reported that nearly 36.2% of patients did not complete their vaccinations [30].

In some studies, the underreporting of animal bites or delays in seeking medical care may also skew data on the completion of PEP and RIG use. Rural settings often have fewer health infrastructure resources, leading to missed opportunities for PEP administration or RIG use, contributing to incomplete vaccination courses.

The fact that only about half of the patients were aware of the need for rabies vaccination after a dog bite reveals a critical gap in public awareness. This underscores the need for enhanced public health education campaigns to improve awareness of rabies risks and the importance of seeking prompt medical attention after animal bites.

4.3. Different Practices of Post-Exposure Prophylaxis (PEP)

PEP initiation times and vaccination regimens differed significantly between urban and rural settings. Urban centers, with better healthcare infrastructure and access to vaccines, tended to initiate PEP more promptly. In contrast, rural areas may face delays in initiating treatment due to healthcare access issues or delayed reporting of animal bites. For instance, Davarani et al. (2023) found that 93% of patients in urban areas received treatment within 48 h, compared to lower rates in rural regions [28]. This delay increases the risk of incomplete immunization, which is more common in rural settings due to limited healthcare resources.

The type and number of doses administered varied across different healthcare settings. While Oztoprak et al. (2021) reported a higher frequency of full 5-dose vaccination schedules (40.5%) in urban settings [43], Amiri et al. (2020) found that a significant portion of rural patients received incomplete vaccinations [37]. This reflects the variation in adherence to international vaccination guidelines and the challenges in ensuring full immunization, particularly in areas with fewer resources.

The type of animal involved in the exposure also influenced PEP protocols. In countries like Turkey and Iran, where rabies is endemic in stray dog populations, the majority of exposures are related to dogs (67.7% in Davarani et al.’s study and 61.2% in Oztoprak et al.) [28,43], which are treated according to standard PEP protocols. However, exposures from wild animals, like bats or foxes, may lead to more aggressive treatments due to their higher risk of rabies transmission. This differentiation is crucial in determining the type and urgency of the prophylactic regimen.

The timeliness of PEP is another significant factor that varies by setting. For instance, Sarbazi et al. (2020) and Poorolajal et al. (2015) report that the majority of patients in urban settings received PEP within 48 h, a key window for effective rabies prevention [34,40]. However, delays of over 48 h, particularly in rural regions, are common due to difficulties in timely reporting and accessing medical treatment.

These distinctions highlight the need for improved healthcare access, particularly in underserved areas, and the importance of standardized PEP protocols across different settings to ensure timely and effective rabies prevention.

4.4. WHO’s Global Rabies Elimination Strategy (2018)

The findings of the review are aligned with and further inform the WHO’s Global Rabies Elimination Strategy and its guidelines on rabies PEP [3]. The WHO recommends that PEP be initiated as soon as possible, ideally within 24 h of exposure, and no later than 48 h [3]. Our review found that urban areas generally adhered to these timelines, with over 90% of patients in studies, such as those of Davarani et al. (2023) and Khazaei et al. (2023), receiving PEP within 48 h [28,29]. However, in rural settings, delays in initiation were noted, reflecting challenges in healthcare access and infrastructure. These findings emphasize the need for strengthening rabies surveillance and improving access to timely medical interventions, as emphasized by the WHO’s call for better global rabies surveillance systems.

According to the WHO guidelines, completing a full five-dose vaccine regimen is essential for rabies prevention [3]. In our review, incomplete vaccination was a recurring issue, particularly in rural regions, with studies such as those of Amiri et al. (2020) and Porsuk et al. (2021) showing that a significant proportion of patients received fewer than five doses [31,37]. This is consistent with the WHO’s recommendation to monitor vaccine adherence and address barriers to completing vaccination schedules. Improving community education and ensuring supply chain reliability for vaccines are key areas to improve completion rates.

The WHO advocates for equitable access to vaccines and PEP across all regions, especially in rural and underserved areas [3]. Our findings underscore the need for increased efforts in these areas, where delays in treatment and incomplete immunization were more common. Programs to improve access to rabies vaccines in low-resource settings are essential to reduce the rabies burden, which aligns with the WHO’s emphasis on targeted strategies for rural and high-risk populations.

Lastly, the WHO’s One Health approach to rabies prevention integrates human, animal, and environmental health. Our review’s inclusion of Turkey and Iran, along with Gulf countries, highlights the transnational nature of rabies risks and the importance of regional cooperation. Data from these countries can help inform cross-border rabies control strategies and improve vaccine distribution and education. This is consistent with the WHO’s strategy to enhance collaborative efforts in rabies prevention across countries with shared risks and health challenges.

4.5. Safety of Vaccines

The overall safety of reported vaccines appears to be generally safe, with mostly mild-to-moderate side effects reported. Verorab appeared to have a better safety profile than Abhayrab, with lower incidence rates for most side effects. PVRV and PCECV showed similar safety profiles, with some variations in specific side effects [20,21]. Local pain at the injection site was consistently reported across all vaccines. Systemic effects, like headache, fever, and weakness, were also commonly reported. Serious side effects appeared to be rare, with no life-threatening reactions reported in these studies. Some effects, like irregular menstruation and decreased libido, were only reported in the Abhayrab group, but at very low rates. The two studies showed some differences in reported side effects, which could be due to differences in study design, population, or reporting methods. The studies had different sample sizes and may have used different methods for collecting and reporting side effects. While all vaccines showed some side effects, they appeared to be generally safe and well tolerated. In the second study, Verorab, PVRV and PCECV demonstrated favorable safety profiles. However, individual responses to vaccines can vary, and patients should be informed about potential side effects. The choice of vaccine may depend on various factors, including availability, cost, and individual patient characteristics.

The WHO’s guidelines highlight the safety of rabies vaccines, reporting that adverse events are generally rare and mild. In our review, most studies, including those of Yıldırım et al. (2022) and Davarani et al. (2023), reported that the adverse events were mostly local reactions, such as pain at the injection site or mild fever [28,30], which is consistent with the WHO’s safety profiles for both purified chick embryo cell and purified Vero cell vaccines [3]. This reinforces the ongoing commitment to using safe vaccines as part of rabies control programs globally.

5. Limitations

The heterogeneity in study designs, sample sizes, and timeframes presents challenges in drawing definitive conclusions. Future research should focus on standardizing data collection methods and conducting longitudinal studies to better understand trends over time. Additionally, investigating the reasons behind incomplete vaccination courses and variations in RIG administration could inform targeted interventions to improve PEP adherence. While the findings demonstrated general adherence to the WHO guidelines for rabies PEP, they also revealed areas for improvement in public education, healthcare practices, and resource allocation. Addressing these gaps could significantly enhance rabies prevention efforts in the Persian Gulf region and beyond.

6. Implications and Future Directions

There is a critical need for enhanced public health education campaigns to improve awareness of rabies risks and the importance of seeking prompt medical attention after animal bites. Targeted education efforts should focus on young males, who are disproportionately affected by animal bites. The higher prevalence of bites in urban areas suggests a need for improved urban planning and animal control measures to manage human–animal interactions in densely populated areas. There is also a need for strengthened domestic animal vaccination programs, particularly for dogs and cats, to reduce the risk of rabies transmission. Efforts should be made to standardize PEP protocols across healthcare settings, particularly regarding the administration of rabies RIG. Improved patient follow-up systems are needed to ensure completion of full vaccination courses. The variability in RIG administration rates suggests a need for a more equitable distribution of resources across healthcare settings to ensure all patients receive optimal care.

Future research should focus on standardizing data collection methods and conducting longitudinal studies to better understand trends over time. Investigation into the reasons behind incomplete vaccination courses could inform targeted interventions to improve PEP adherence. Findings could inform the development of more targeted and effective rabies prevention policies at local and national levels.

The findings underscore the importance of a One Health approach, integrating human health, animal health, and environmental factors in rabies prevention strategies. Given the regional focus of the studies, there is an opportunity for increased international collaboration in rabies prevention efforts across the Persian Gulf countries. These implications highlight the multifaceted approach needed to improve rabies prevention and control, encompassing public education, healthcare practices, policy development, and research priorities.

Supplementary Materials

The following supporting information can be downloaded at: https://www.mdpi.com/article/10.3390/diseases13040124/s1, File S1: PRISMA flow chart; Table S1: Details of searching of each database; Table S2: More details of the baseline characteristics of the included patients.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.F.H., K.S.A., A.M.A., N.D.A., A.S.A. (Abdullah S. Albalawi), S.M.A.-A., S.E.A., M.J.A., M.F.A., A.A.A., H.E., A.S.A. (Abdulmajeed S. Albalawi) and R.S.; methodology, H.F.H. and R.S.; software, H.F.H. and R.S.; validation, H.F.H., K.S.A., A.M.A., N.D.A., A.S.A. (Abdulmajeed S. Albalawi), S.M.A.-A., S.E.A., M.J.A., M.F.A., A.A.A. and A.S.A. (Abdullah S. Albalawi); formal analysis, H.F.H. and R.S.; investigation, H.F.H. and R.S.; resources, H.F.H. and R.S.; data curation, H.F.H. and R.S.; writing—original draft preparation, H.F.H., K.S.A., A.M.A., N.D.A., A.S.A. (Abdulmajeed S. Albalawi), S.M.A.-A., S.E.A., M.J.A., M.F.A., A.A.A., H.E., A.S.A. (Abdullah S. Albalawi) and R.S.; writing—review and editing, H.F.H., K.S.A., A.M.A., N.D.A., A.S.A. (Abdullah S. Albalawi), S.M.A.-A., S.E.A., M.J.A., M.F.A., A.A.A., H.E., A.S.A. (Abdulmajeed S. Albalawi) and R.S.; visualization, H.F.H. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

No new data were created or analyzed in this study. Data sharing does not apply to this article.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Hampson, K.; Coudeville, L.; Lembo, T.; Sambo, M.; Kieffer, A.; Attlan, M.; Barrat, J.; Blanton, J.D.; Briggs, D.J.; Cleaveland, S.; et al. Estimating the global burden of endemic canine rabies. PLoS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2015, 9, e0003709. [Google Scholar]

- Gan, H.; Hou, X.; Wang, Y.; Xu, G.; Huang, Z.; Zhang, T.; Lin, R.; Xue, M.; Hu, H.; Liu, M.; et al. Global burden of rabies in 204 countries and territories, from 1990 to 2019: Results from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2023, 126, 136–144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- World Health Organization. WHO Expert Consultation on Rabies: Third Report; World Health Organization: Geneva, Switzerland, 2018; Volume 1012. [Google Scholar]

- Hankins, D.G.; Rosekrans, J.A. Overview, prevention, and treatment of rabies. In Mayo Clinic Proceedings; Elsevier: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2004; pp. 671–676. [Google Scholar]

- Wertheim, H.F.L.; Nguyen, T.Q.; Nguyen, K.A.T.; de Jong, M.D.; Taylor, W.R.J.; Le, T.V.; Nguyen, H.H.; Nguyen, H.T.H.; Farrar, J.; Horby, P.; et al. Furious rabies after an atypical exposure. PLoS Med. 2009, 6, e1000044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wilde, H.; Hemachudha, T.; Wacharapluesadee, S.; Lumlertdacha, B.; Tepsumethanon, V. Rabies in Asia: The classical zoonosis. In One Health: The Human-Animal-Environment Interfaces in Emerging Infectious Diseases: The Concept and Examples of a One Health Approach; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2013; pp. 185–203. [Google Scholar]

- World Health Organization. Rabies vaccines: WHO position paper, April 2018–Recommendations. Vaccine 2018, 36, 5500–5503. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hampson, K.; Cleaveland, S.; Briggs, D. Evaluation of cost-effective strategies for rabies post-exposure vaccination in low-income countries. PLOS Neglected Trop. Dis. 2011, 5, e982. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kasem, S.; Hussein, R.; Al-Doweriej, A.; Qasim, I.; Abu-Obeida, A.; Almulhim, I.; Alfarhan, H.; Hodhod, A.A.; Abel-Latif, M.; Hashim, O.; et al. Rabies among animals in Saudi Arabia. J. Infect. Public Health 2019, 12, 445–447. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Warrell, M.J. Current rabies vaccines and prophylaxis schedules: Preventing rabies before and after exposure. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2012, 10, 1–15. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wernery, U. Zoonoses in the Arabian peninsula. Saudi Med. J. 2014, 35, 1455. [Google Scholar]

- Memish, Z.A.; Assiri, A.M.; Gautret, P. Rabies in Saudi Arabia: A need for epidemiological data. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2015, 34, 99–101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Dubaib, M. Rabies in camels at Qassim region of central Saudi Arabia. J. Camel Pract. Res. 2007, 14, 101–103. [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A.C.; Lillie, E.; Zarin, W.; O’Brien, K.K.; Colquhoun, H.; Levac, D.; Moher, D.; Peters, M.D.; Horsley, T.; Weeks, L.; et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann. Intern. Med. 2018, 169, 467–473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bay, V.; Rezapour, A.; Jafari, M.; Maleki, M.R.; Asl, I.M. Healthcare utilization patterns and economic burden of animal bites: A cross-sectional study. J. Acute Dis. 2021, 10, 142–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilic, B.; Unal, B.; Semin, S.; Konakci, S.K. An important public health problem: Rabies suspected bites and post-exposure prophylaxis in a health district in Turkey. Int. J. Infect. Dis. 2006, 10, 248–254. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Taghvaii, M.R.E.; Seyednozadi, S.M. An epidemiologic survey on animal bite cases referred to health centers in mashhad during 2006 to 2009. Biomed. Pharmacol. J. 2015, 6, 301–306. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Khazaei, S.; Shiraz Medical University; Karami, M.; Veisani, Y.; Solgi, M.; Goodarzi, S. Epidemiology of animal bites and associated factors with delay in post-exposure prophylaxis; a cross-sectional study. Bull. Emerg. Trauma 2018, 6, 239. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Roncero, M.I.G.; Cerdá-Olmedo, E. Genetics of carotene biosynthesis in phycomyces. Curr. Genet. 1982, 5, 5–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sari, T.; Tulek, N.; Bulut, C.; Oral, B.; Ertem, G.T. Adverse events following rabies post-exposure prophylaxis: A comparative study of two different schedules and two vaccines. Travel Med. Infect. Dis. 2014, 12, 659–666. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramezankhani, R.; Shirzadi, M.R.; Ramezankhani, A.; Poor, M.J. A comparative study on the adverse reactions of purified chick embryo cell vaccine (PCECV) and purified vero cell rabies vaccine (PVRV). Arch. Iran Med. 2016, 19, 502–507. [Google Scholar]

- Khoubfekr, H.; Jokar, M.; Rahmanian, V.; Blouch, H.; Shirzadi, M.R.; Bashar, R. Fatal cases in pediatric patients after post-exposure prophylaxis for rabies: A report of two cases. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Med. 2024, 17, 39–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ansari, M.; Shafiei, M.; Kordi, R. Dog bites among off-road cyclists: A report of two cases. Asian J. Sports Med. 2012, 3, 60. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tabbara, K.F.; Al-Omar, O. Eyelid laceration sustained in an attack by a rabid desert fox. Arch. Ophthalmol. 1995, 119, 651–652. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rasooli, A.; Pourhossein, B.; Bashar, R.; Shirzadi, M.R.; Amiri, B.; Kheiri, E.V.; Mostafazadeh, B.; Fazeli, M. Case Report: Investigating Possible Etiologies of Post-Exposure Prophylaxis Failure and Deaths From Rabies Infection. Int. J. Med. Toxicol. Forensic Med. 2020, 10, 27378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Farahtaj, F.; Fayaz, A.; Howaizi, N.; Biglari, P.; Gholami, A. Human rabies in Iran. Trop. Dr. 2014, 44, 226–229. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bizri, A.R.; Azar, A.; Salam, N.; Mokhbat, J. Human rabies in Lebanon: Lessons for control. Epidemiol. Infect. 2000, 125, 175–179. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davarani, E.R.; Domari, A.A.; Mahani, A.H.; Samakkhah, S.A.; Raesi, R.; Daneshi, S. Epidemiological characteristics, injuries, and rabies post-exposure prophylaxis among children in Kerman county, Iran during 2019–2021. Open Public Health J. 2023, 16, e187494452303272. [Google Scholar]

- Khazaei, S.; Shirzadi, M.R.; Amiri, B.; Pourmozafari, J.; Ayubi, E. Epidemiologic aspects of animal bite, rabies, and predictors of delay in post-exposure prophylaxis: A national registry-based study in Iran. J. Res. Health Sci. 2023, 23, e187494452303272. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldırım, A.A.; Doğan, A.; Kurt, C.; Çetinkol, Y. Evaluation of Our Rabies Prevention Practices: Is Our Approach Correct? Iran. J. Public Health 2022, 51, 2128–2134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Porsuk, A.O.; Cerit, C. An increasing public health problem: Suspected rabies exposures. J. Infect. Dev. Ctries. 2021, 15, 1694–1700. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amiri, S.; Maleki, Z.; Nikbakht, H.-A.; Hassanipour, S.; Salehiniya, H.; Ghayour, A.-R.; Kazemi, H.; Ghaem, H. Epidemiological Patterns of Animal Bites in the Najafabad, Center of Iran (2012–2017). Ann. Glob. Health 2020, 86, 38. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Janatolmakan, M.; Delpak, M.; Abdi, A.; Mohamadi, S.; Andayeshgar, B.; Khatony, A. Epidemiological study on animal bite cases referred to Haji Daii health Center in Kermanshah province, Iran during 2013–2017. BMC Public Health 2020, 20, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sarbazi, E.; Sarbazi, M.; Ghaffari-Fam, S.; Babazadeh, T.; Heidari, S.; Aghakarimi, K.; Jamali, I.; Sherini, A.; Babaie, J.; Darghahi, G. Factors related to delay in initiating post-exposure prophylaxis for rabies prevention among animal bite victims: A cross-sectional study in Northwest of Iran. Bull. Emerg. Trauma 2020, 8, 236. [Google Scholar] [PubMed]

- Kassiri, H.; Ebrahimi, A.; Lotfi, M. Animal Bites: Epidemiological Considerations in the East of Ahvaz County, Southwestern Iran (2011–2013). Arch. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2018, 13, 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Babazadeh, T.; Nikbakhat, H.A.; Daemi, A.; Yegane-Kasgari, M.; Ghaffari-Fam, S.; Banaye-Jeddi, M. Epidemiology of acute animal bite and the direct cost of rabies vaccination. J. Acute Dis. 2016, 5, 488–492. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohtasham-Amiri, Z.; Pourmarzi, D.; Razi, M. Epidemiology of dog bite, a potential source of rabies in Guilan, north of Iran. Asian Pac. J. Trop. Dis. 2015, 5, S104–S108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Celiloglu, C.; OzdemIr, U.; Tolunay, O.; Sucu, A.; Celik, U. Post-exposure Rabies Prophylaxis for Children in Southern Turkey. J. Coll. Physicians Surg. Pak. 2021, 31, 1219–1223. [Google Scholar]

- Riabi, H.R.A.; Ghorbannia, R.; Mazlum, S.B.; Atarodi, A. A Three-year (2011–2013) Surveillance on Animal Bites and Victims Vaccination in the South of Khorasan-e-Razavi Province, Iran. J. Clin. Diagn. Res. 2015, 9, LC01–LC05. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Poorolajal, J.; Babaee, I.; Yoosefi, R.; Farnoosh, F. Animal bite and deficiencies in rabies post-exposure prophylaxis in Tehran, Iran. Arch. Iran. Med. 2015, 18, 822–826. [Google Scholar]

- Charkazi, A.; Behnampour, N.; Fathi, M.; Esmaeili, A.; Shahnazi, H.; Heshmati, H. Epidemiology of animal bite in Aq Qala city, northen of Iran. J. Educ. Health Promot. 2013, 2, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ghannad, M.S.; Roshanaei, G.; Rostampour, F.; Fallahi, A. An epidemiologic study of animal bites in Ilam Province, Iran. Arch. Iran. Med. 2012, 15, 356–360. [Google Scholar]

- Oztoprak, N.; Berk, H.; Kizilates, F. Preventable public health challenge: Rabies suspected exposure and prophylaxis practices in southwestern of Turkey. J. Infect. Public Health 2021, 14, 221–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Can, F.K.; Tekin, E.; Sezen, S.; Clutter, P. Assessment of rabies prophylaxis cases in an emergency service. J. Emerg. Nurs. 2020, 46, 907–913. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rahmanian, V.; Shakeri, H.; Jahromi, A.S.; Shakeri, M.; Khoubfekr, H.; Hatami, I. Epidemiological Characteristic of Animal Bite and Direct Economic Burden of Rabies Vaccination in the Southern of Iran. Am. J. Anim. Veter-Sci. 2020, 15, 245–251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bijari, B.; Sharifzade, G.R.; Abbasi, A.; Salehi, S. Epidemiological survey of animal bites in east of Iran. Arch. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2011, 6, 90–92. [Google Scholar]

- Sengoz, G.; Yasar, K.K.; Karabela, S.N.; Yildirim, F.; Vardarman, F.T.; Nazlican, O. Evaluation of cases admitted to a center in Istanbul, Turkey in 2003 for rabies vaccination and three rabies cases followed up in the last 15 years. Jpn. J. Infect. Dis. 2006, 59, 254–257. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hamta, A.; Saghafipour, A.; Hosseinalipour, S.A.; Rezaei, F. Forecasting delay times in post-exposure prophylaxis to human animal bite injuries in Central Iran: A decision tree analysis. Veter-World 2019, 12, 965–971. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Najafi, N.; Ghasemian, R. Animal bites and rabies in northern Iran, 2001–2005. Iran. J. Clin. Infect. Dis. 2009, 4, 224–227. [Google Scholar]

- Karbeyaz, K.; Ayranci, U. A Forensic and Medical Evaluation of Dog Bites in a Province of W estern T urkey. J. Forensic Sci. 2014, 59, 505–509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheikholeslami, N.Z.; Rezaeian, M.; Salem, Z. Epidemiology of animal bites in Rafsanjan, southeast of Islamic Republic of Iran, 2003–05. East. Mediterr. Health J. 2009, 15, 455–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).