Abstract

Graves’ ophthalmopathy is the most common extrathyroidal manifestation of Graves–Basedow disease. Radiotherapy is effective especially when used in synergy with the administration of glucocorticoids. The aim of our study was to analyze the effectiveness and safety of radiotherapy, using different protocols, to improve ocular symptoms and quality of life. Methods: We retrospectively analyzed the clinical data of two-hundred and three patients treated with retrobulbar radiotherapy between January 2002 and June 2023. Ninety-nine patients were treated with a schedule of 10 Gy in 10 fractions and one-hundred and four were treated with 10 Gy in 5 fractions. Radiotherapy (RT) was administrated during the 12 weeks of pulse steroid therapy. Patients were evaluated with a clinical exam, orbital CT, thyroid assessment, and Clinical Activity Score (CAS). Results: The median follow-up was 28.6 months (range 12–240). Complete response was found in ninety-four pts (46.31%), partial response or stabilization in one hundred pts (49.26%), and progression in nine pts (4.43%). In most subjects, an improvement in visual acuity and a reduction in CAS of at least 2 points and proptosis by more than 3 mm were observed. Three patients needed decompressive surgery after treatment. Only G1 and G2 acute eye disorders and no cases of xerophthalmia or cataract were assessed. Conclusions: RT is an effective and well-tolerated treatment in this setting, especially when associated with the administration of glucocorticoids. Although the most used fractionation schedule in the literature is 20 Gy in 10 fractions, in our clinical practice, we have achieved comparable results with 10 Gy in 5 or 10 fractions with a lower incidence of toxicity.

1. Introduction

Graves’ ophthalmopathy (GO) is an inflammatory pathology of the orbit associated with an underlying autoimmune pathogenesis [1,2]. GO represents the most frequent extrathyroidal manifestation and its associated with hyperthyroidism in 90% of cases (primarily with Graves’ disease, less frequently with Hashimoto’s thyroiditis, myxedema without previous thyrotoxicosis) [3]. GO primarily involves inflammatory changes in orbital tissues, especially retrobulbar soft tissues with potential thickening and fibrosis of the extraocular muscles (EOMs) and orbital fat, increasing the volume within bony orbit [4]. The principal cause is the production of antibodies directed against thyroid stimulating hormone (TSH) receptors located in the retro-orbital space, increasing the productions of various cytokines [5,6]. These cytokines stimulate fibroblasts to produce glycosaminoglycan that, when hydrophilic, results in edema, causing marked swelling of the orbital tissue in GO [1]. The symptomatic presentations of GO are a direct result of the inflammatory and fibrotic reactions in the retro-orbital space [5]. Incidence is higher between the second and sixth decade of age, with a peak between 40 and 60 years of age, especially in women (female/male ratio of 5:1). It can be predominantly bilateral, but unilateral and asymmetrical forms are also documented [7]. GO is accompanied by complex ocular symptoms that can be debilitating and impair the quality of life (QoL) of the affected individual, with effects on work and social relationships [8]. The clinical evolution of GO is characterized by a progressive deterioration that can be divided into three phases: active phase or florid, characterized by increased activity, where symptoms and signs worsen rapidly, reaching a point of maximal severity, followed by a static plateau period, with a gradual improvement toward the baseline, and finally a phase of progressive shutdown or inactivation [9]. This cycle has a variable duration from individual to individual, but usually it does not exceed 12–24 months [10]. To ensure stable and lasting control of Graves’ ophthalmopathy, it is crucial to implement behavioral strategies and, when necessary, pharmacological therapies from the outset. This includes maintaining a euthyroid state, managing metabolic syndrome, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, and quitting smoking [11,12,13,14].

Treatment options are numerous and can be tailored to patients depending on the severity and time from the onset of the disease. Among them, radiotherapy has been used for decades for ocular pathologies with optimal results [15,16,17,18,19].

The aim of our study was to retrospectively compare the effectiveness in symptoms control and safety between two populations of patients treated with intravenous steroid therapy and subjected to radiotherapy with the same total dose but two different fractionation schedules.

2. Materials and Methods

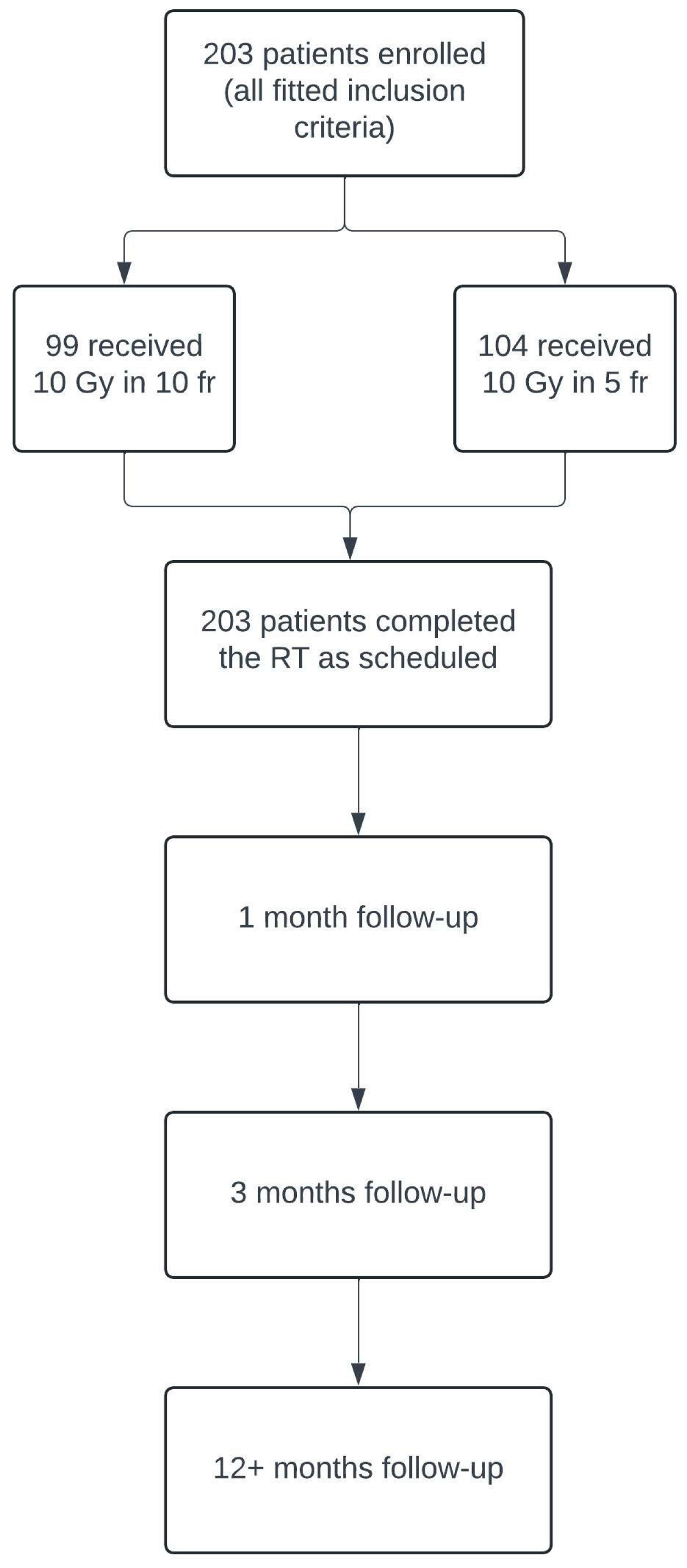

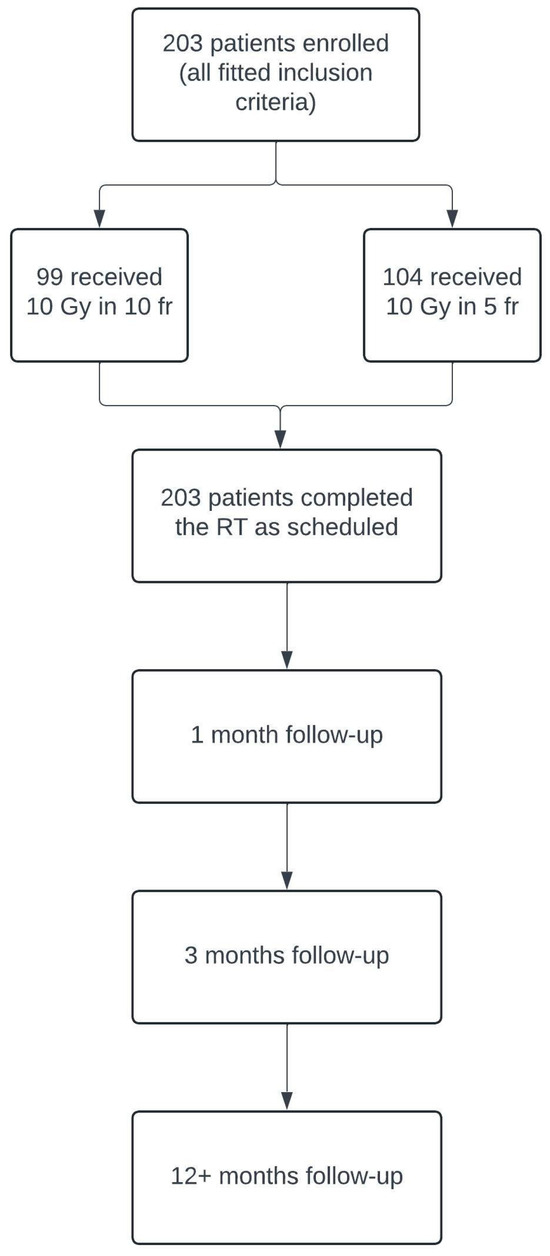

Between January 2002 and June 2023, two-hundred and three patients with GO diagnosis were treated with retrobulbar radiotherapy in the Oncologic Radiotherapy ward of “G. Rodolico” Hospital in Catania. We retrospectively evaluated the clinical reports of these patients, using the inclusion and exclusion criteria, and the study design is represented in Table 1 and Figure 1, respectively.

Table 1.

Inclusion and exclusion criteria.

Figure 1.

Flowchart illustrating the design of our retrospective study, including patient enrollment and follow-up process.

Patients were assessed at the baseline with a clinical examination comprising an ocular exam with visual field, orbital computer tomography (CT), thyroid function assessment (including thyroid stimulating hormone TSH, T3, T4, free thyroxine FT4 levels), CAS (Clinical Activity Score) (Table 2), clinical assessment of GO severity (Table 3), and proptosis measured with the Hertel ophthalmometer [14].

Table 2.

Assessment of Graves’s orbitopathy activity [14].

Table 3.

Classification of GO’s severity [14].

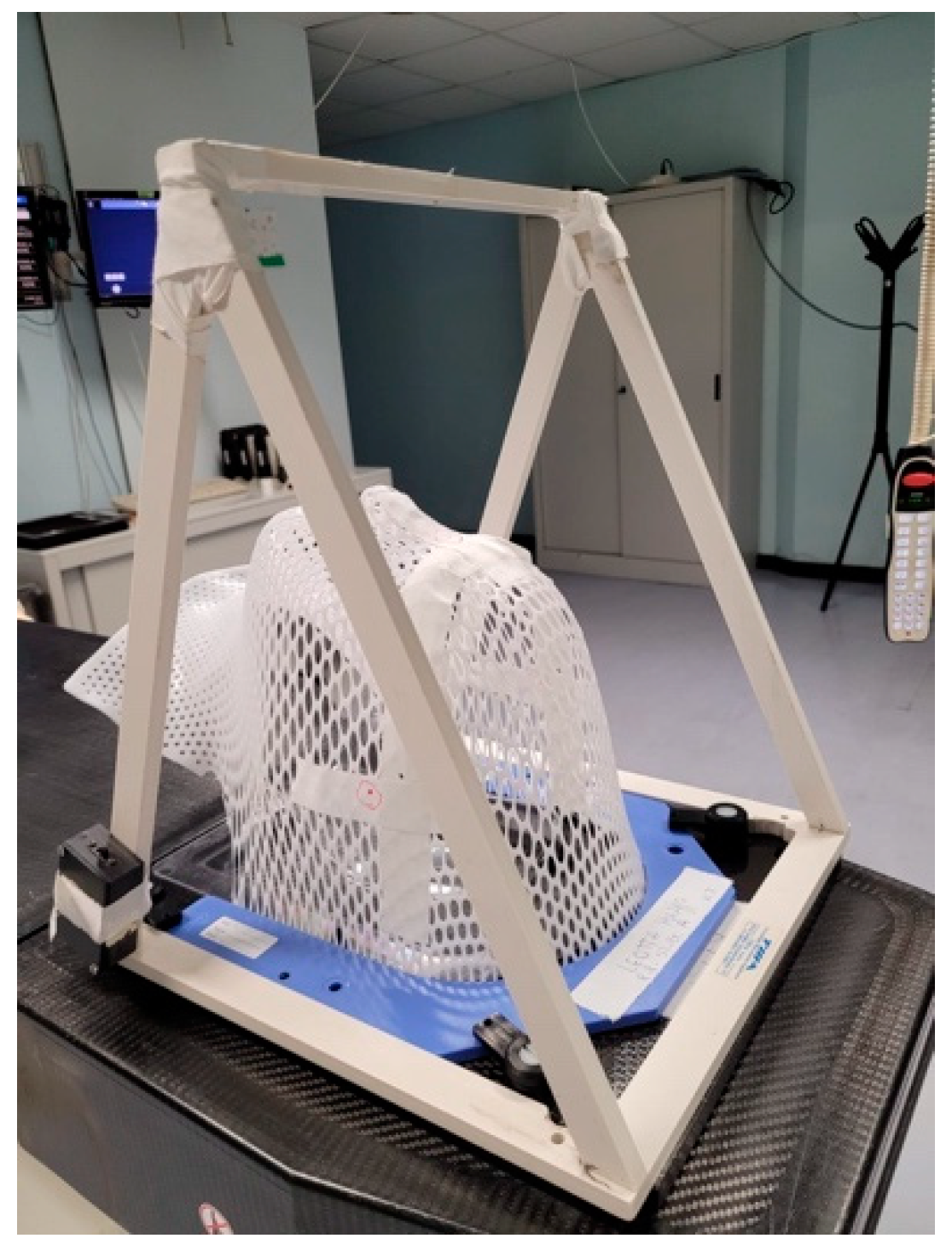

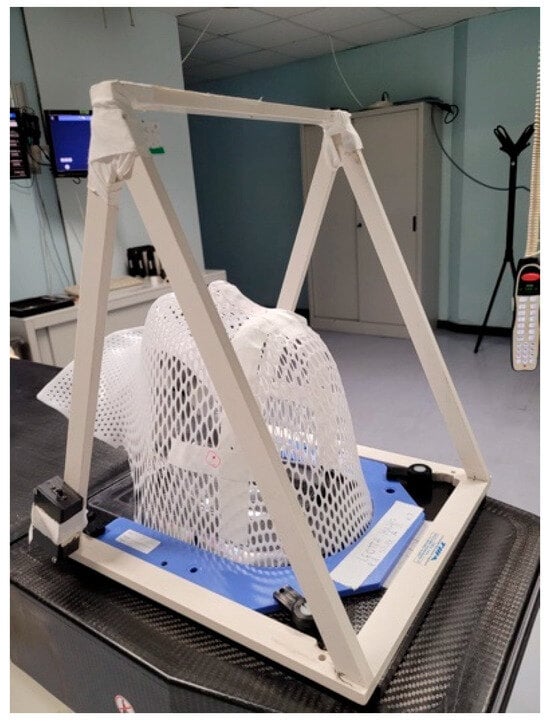

A CT scan without contrast with a slice thickness of 2 mm was performed for image acquisition and target contouring. Patients were immobilized with a custom-made thermoplastic mask in supine position. We also used a device called “Eye Bridge” (Figure 2), endowed with a central red laser for sight fixation during the CT and the subsequent fractions that helped us to reduce the dose to both lenses.

Figure 2.

The immobilization device in this image is called “Eye Bridge” or “Eye Fixation System”. It is a plastic structure fitted to frame the thermoplastic base. A red laser is located in the central horizontal bar positioned like a bridge above the orbits. During the CT simulation and treatment phases, patients are instructed to keep their gaze fixed on the red light to better preserve the crystalline lenses.

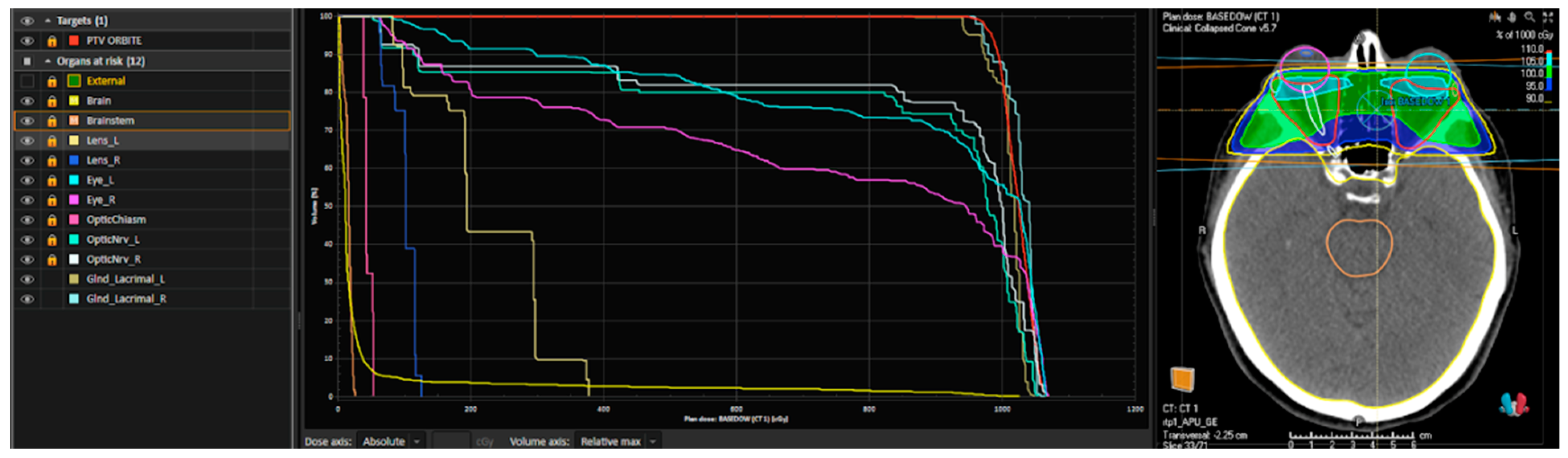

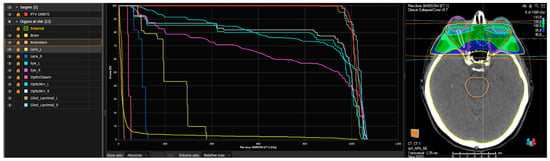

The treatment was planned on MOSAIQ® (IMPAC Medical Systems, Sunnyvale, CA, USA) for patients treated before 2020 and RayStation® (RaySearch Medical Laboratories AB, Stockholm, Sweden) for the rest of the patients; we provide an example of this plan in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

An example of a dose–volume histogram (DVH) and a plan rendering of a patient treated with 10 Gy in 5 fractions performed using Raystation®. From left to right: the planning target volume (PTV) in red includes the retro-orbital space; the other indicated structures correspond to the organs at risk (OARs) (external referring to the patient’s skin, brain and brainstem, optic chiasm, optic nerves, lenses, eyeballs, and lacrimal glands on both sides). In the central section, the DVH (dose–volume histogram) is shown, graphically representing the dose distribution to the PTV (in red) and the organs at risk. On the right side, an example of a treatment plan is displayed, including the PTV, OARs, and the treatment field coverage.

The clinical target volume (CTV) was defined as equivalent to the PTV (planning target volume) and included retro-orbital fat and orbital muscles. Bilateral lenses, eyeballs, optic nerves, lacrimal glands, chiasm, brain, and brainstem were contoured as organs at risk (OARs). Before every treatment session, a portal image was taken daily to help minimize set-up uncertainties, making the treatment more reproducible, accurate, and precise.

All patients were treated with Three-Dimensional Conformational Radiation Therapy (3DCRT) using a 6 MV photon beam linear accelerator (with a linear accelerator-based OncorTM, Siemens Medical Solutions, Erlangen, Germany), administrated with 2 lateral fields, tilting the beams posteriorly with a personalized angle between 5 and 7 degrees to spare the lens and contralateral ocular areas.

Radiotherapy (RT) was imbricated during the 12 weeks of pulse steroid therapy (weekly hydrocortisone i.v. bolus).

Patients underwent the first clinical revaluation at the end of the RT course by the radiation oncologists. The follow-up was continued at one month and then three months for the first two years, and then every year. During the follow-up, all patients underwent separate evaluations by the ophthalmologist and endocrinologist. Depending on the specialists’ clinical practice, orbital CT scans were performed as needed. Within the six months of follow-up, all patients had an ophthalmologic assessment, including ophtalmometric proptosis evaluation.

The response to orbital RT was defined as an improvement in CAS of at least two points, a reduction in proptosis by at least 2 mm, an improvement in diplopia and edema, a reduction in lacrimation and pain and pain during eye movements, and an improvement in visual acuity.

Treatment-related toxicities were graded according to the Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (version 5.0) [20]. Acute toxicities were defined as adverse events occurred during or within 90 days from the end of treatment and late toxicity as adverse events occurred from 90 days after the end of radiotherapy.

3. Results

Among two-hundred and three patients, 66.6% and 65.38% were females patients treated with 10 fractions and 5 fractions, respectively. The two cohorts displayed similar characteristics in terms of age, gender, smoking habits, diabetes, serum parameters, symptom onset timing, disease activity, and severity based on the patient profiles rather than statistical evaluation. Ninety-nine patients were treated using a schedule of 10 Gy administrated in 10 fractions and, due to the concomitant COVID-19 pandemic, the other one-hundred and four patients were treated with a shortened and hypofractionated schedule of 10 Gy in 5 fractions. All the population characteristics at baseline, the CAS, and symptoms are summarized in Table 4.

Table 4.

Baseline patient characteristics (n = 203).

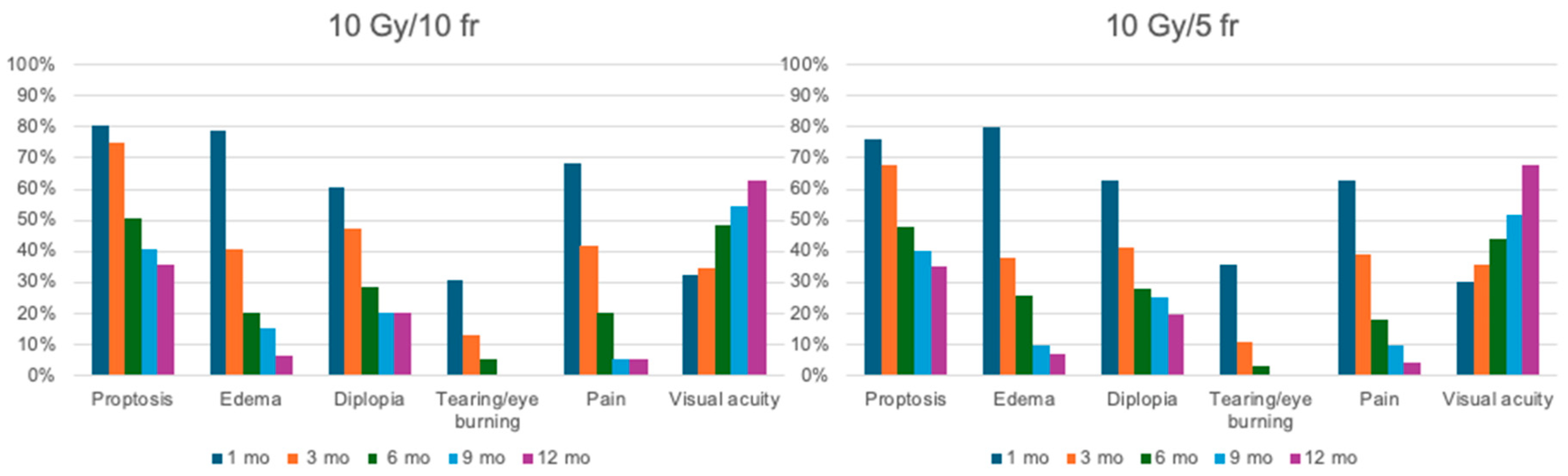

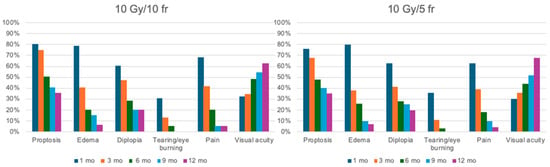

The median follow-up was 28.6 months (range 12–240). Complete response was found in ninety-four patients (46.31%), partial response or stabilization in one hundred patients (49.26%), and progression in nine patients (4.43%). All patients completed their treatment on time without any interruptions. During the first six months of follow-up, an improvement in visual acuity and a reduction in CAS of at least 2 points and proptosis by more than 3 mm were observed in 86.4% and 74.6% of patients, respectively. Only three patients needed decompressive surgery after treatment. There were only 30 cases of G1 acute blurred vision, 80 cases of G1 dry eye treated with lubricants, and 5 cases of G2 eye pain. In all these cases, the symptoms resolved spontaneously, without leaving long-term sequelae. No cases of xerophthalmia or cataracts were assessed. The changes compared to the initial symptoms and their progression are outlined in Table 5 and Table 6 and are represented graphically in Figure 4. At the 9- and 12-month follow-ups, none of the patients in either study cohort reported tearing or eye burning.

Table 5.

Symptoms, proptosis, and CAS showed at every follow-up in patients treated with 10 Gy/10 fractions.

Table 6.

Symptoms showed at every follow-up for the first year after RT in patients treated with 10 Gy/5 fractions.

Figure 4.

Graphic representation of outcome. On the left is the treatment response in patients treated with 10 Gy in 10 fractions; on the right is the response in patients treated with 10 Gy in 5 fractions. Patients from both treatment arms were evaluated at 1, 3, 6, 9, and 12 months after the completion of radiotherapy.

4. Discussion

Radiotherapy (RT) has been used in thyroid-associated orbitopathy (TAO) since 1913 [21]. It is known that ionizing radiation at low doses of 0.1–1 Gy functionally modulates inflammatory cells, especially lymphocytes, and activates heat shock proteins; the induction of nitric oxide synthase in activated macrophages may also be involved in the anti-inflammatory response to radiation. While the anti-inflammatory effect of retrobulbar irradiation is evident at low doses such as 2.4 Gy, higher doses are necessary to avoid the synthesis of glycosaminoglycans by orbital fibroblasts [15,22,23]. On the other hand, higher doses may have a negative impact by inducing the fibrosis of the extraocular muscles [24]. Although retrobulbar RT for GO has been routinely used for decades, data on the optimal dose and fractionation schedules to be administered to obtain the maximum response in the absence of complications are still controversial. From the 1970s to present day, several studies have been carried out that aimed to evaluate the effectiveness of retrobulbar radiotherapy in GO, documenting also a few side effects [5,15,16,17,25,26,27,28,29,30,31,32,33,34,35,36]. The best responses were observed on soft tissues, corneal involvement, and a reduction in vision loss, though there were less positive responses in terms of ocular motility and proptosis [37,38,39]. The response to radiotherapy can be negatively influenced by several factors: duration of symptoms (>12 months), male gender, coexistent hyperthyroidism, advanced age, diabetes, and cigarette smoking, while the female sex constitutes to be a favoring factor [11,40,41]. Radiotherapy should be recommended in the early stages of the disease, preferably less than twelve months after the onset of symptoms. The efficacy of orbital radiotherapy can be increased by the synergistic interaction with glucocorticoids, as demonstrated by several studies and metanalyses [16,30,31,42]. It is particularly useful also in treating those patients who are insensitive or tolerant to GC therapy, or who have relapsing symptoms after glucocorticoid therapy [5]. The effects of RT are slower to show compared to GC, but it can be effective for a longer period. Lateral opposing fields (LOFs), three-dimensional conformational radiotherapy (3D-CRT), and intensity-modulated radiation therapy (IMRT) are all alternative techniques [33,43,44]. We assessed complete response in 46.31% and stabilization in 49.26% without having to resort to further radiation or corticosteroid retreatments, regardless of the presence of risk factors that could have had a negative impact. The most used treatment scheme is 20 Gy administrated in 10 fractions, but different doses and schedules were investigated, as summarized in Table 7 [5,8,17,38,41,45].

Table 7.

Studies confronting a different schedule of RT treatment.

Nakahara et al. [46] evaluated two groups of patients treated with 10 Gy (15 patients) and 24 Gy (16 patients) in association with glucocorticoids (GCs). After a follow-up of 1–3 months, the authors concluded that a dose of 24 Gy is more effective than 10 Gy. Choi et al. [15] used 24 Gy in 12 fractions; Gerling et al. [49] compared total doses of 2.4 Gy and 16 Gy, with no significant differences shown in either group. They concluded that retrobulbar irradiation for ophthalmopathy should not exceed 2.4 Gy. Weissmann et al. [48] confronted two schedules: a low dose of 4.8 Gy in fractions of 0.8 Gy and a high dose of 20 Gy in 10 fractions with no significant difference in the overall improvement in symptoms, but they found that patients treated with lower doses of radiation needed a second series of radiotherapy significantly more frequently than patients treated with high-dose RT. Johnson et al. [47] performed a retrospective study on 129 patients who underwent doses of 12, 16, or 20 Gy. They reported that 12 Gy may be more effective in patients who suffer from dysmotility. Kahaly et al. [37] demonstrated that the same efficacy is obtained with 10 Gy in 10 fractions. In the recent EUGOGO guidelines, both 10 Gy and 20 Gy are considered acceptable alternatives [14]. In Ohtsuka et al.’s study [4], orbital RT after corticosteroid pulse therapy was not associated with beneficial therapeutic effects on rectus muscle hypertrophy or the proptosis of active GO during the 6-month follow-up period. However, in Gorman et al.’s study [34], a prospective randomized trial, forty-two patients were treated with 20 Gy of EBRT and sham therapy on the other side with the reversion of therapy six months later; no clinical or statistical difference was observed.

In our experience of comparing a dose of 10 Gy in ten or five fractions, we did not find a statistically significant difference in the outcome measures after 1, 3, 6, or 12 months, but we did find a slower but steady improvement after longer follow-ups. We also found a better patient-related perception of shorter treatments. Depending on the severity of the symptoms and the time elapsed since their onset, radiotherapy or glucocorticoids associated with it may not be sufficient. New molecules are becoming more relevant in the treatment of patients with moderate or severe GO. Rituximab (a chimeric human and mouse MAB against CD20) can be used at 100 mg or 500 mg dosages [50,51]. An American study [52] confronted rituximab versus placebo, where it showed no difference in reducing CAS or the severity of GO in both groups. In contrast, an Italian study [53] demonstrated better ophthalmic and QoL outcomes with rituximab as compared to i.v. GC administration. Tocilizumab is a humanized MAB against the interleukin (IL)-6 receptor approved for use in rheumatoid arthritis. Data suggest that tocilizumab may cause a rapid resolution of inflammatory signs with benefits predominantly on soft tissue; it is generally well tolerated but with a higher rate of infections and headache [54]. Teprotumumab, a fully human monoclonal insulin-like growth factor-I receptor (IGF-IR) inhibitory antibody (administrated in eight infusions: 10 mg/kg for the first infusion, 20 mg/kg for subsequent infusions over a total of 21 weeks), showed improvements in GO signs and symptoms, with the long-term maintenance of responses [1,37,55]. The safety and efficacy of teprotumumab were evaluated in two trials: OPTIC [23] and OPTIC-X [56], and its incorporation into routine clinical practice is currently limited by the lack of comprehensive long-term efficacy and safety data, the absence of a head-to-head comparison with i.v. glucocorticoids, restricted geographical availability, and costs. The American Thyroid Association/European Thyroid Association Consensus Statement recommended the first-line use of teprotumumab for patients with moderate–severe disease presenting with proptosis and/or diplopia [14]. In clinical practice, however, due to the advent of systemic therapies such as monoclonal antibodies, the role of radiotherapy is increasingly reduced and usually reserved for patients with multiple comorbidities, with relative or absolute contraindications, or those who refuse these treatments.

This study has several limitations due to its retrospective design. Selection bias may have occurred, as treatment decisions were influenced by physician preferences and patient characteristics. Despite including all eligible patients over the 20-year period, unmeasured confounders may still affect the results. Additionally, information bias is a concern, as data were extracted from medical records, and missing or incomplete information could not be fully excluded. Changes in clinical practices over time may have also introduced variability in treatment regimens and supportive care. Another limitation was that the evaluation of proptosis through diagnostic tests was performed at the discretion of the ophthalmologist.

5. Conclusions

Despite the increasing role of immunotherapy and different systemic therapeutic strategies in the treatment of patients with moderate–severe GO, the role of radiotherapy as an effective and well-tolerated therapy is still important. Radiotherapy may help in the long-lasting relief of symptoms and improvements in CAS, proptosis, visual acuity, and ocular movement limitations. As reported in the literature, the synergy between radiotherapy and intravenous steroid therapy leads to excellent results. Although the most commonly used fractionation schedule is 20 Gy in 10 fractions, our study has shown comparable outcomes with lower-dose regimens, such as 10 Gy in 5 or 10 fractions, which also demonstrate equivalent control while resulting in fewer toxic effects.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, C.S., P.V.F., S.P. (Stefano Palmucci) and A.B.; methodology, M.L.R., B.F.L., R.M., R.L.E.L., S.P. (Stefano Pergolizzi), A.P. and C.S.; investigation, M.L.R., B.F.L., M.C.L.G., G.M., G.A., A.B., S.P. (Silvana Parisi), V.A.L.M. and V.S.; resources, E.D., A.B., P.V.F., S.P. (Stefano Palmucci), S.P. (Stefano Pergolizzi) and A.P.; writing—original draft preparation, M.L.R., B.F.L. and C.S.; writing—review and editing, C.S., S.P. (Stefano Pergolizzi) and A.P. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of this manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Ethical committee approval was not required, as this was a retrospective analysis of previously treated patients. No additional therapeutic interventions beyond standard clinical management were performed. Patient confidentiality was ensured by anonymizing data and removing any identifying information.

Informed Consent Statement

Informed consent was obtained from all subjects involved in this study.

Data Availability Statement

The data are not publicly available due to privacy restrictions.

Acknowledgments

The authors wish to express their gratitude to the Department of Medical Surgical Sciences and Advanced Technologies “G.F. Ingrassia” for its invaluable support in the development of this research project and the preparation of the manuscript. Their encouragement and resources were instrumental in bringing this work to fruition.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Correction Statement

This article has been republished with a minor correction to the correspondence contact information. This change does not affect the scientific content of the article.

References

- Bello, O.M.; Druce, M.; Ansari, E. Graves’ Ophthalmopathy: The Clinical and Psychosocial Outcomes of Different Medical Interventions—A Systematic Review. BMJ Open Ophthalmol. 2024, 9, e001515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liardo, R.L.E.; Borzì, A.M.; Spatola, C.; Martino, B.; Privitera, G.; Basile, F.; Biondi, A.; Vacante, M. Effects of Infections on the Pathogenesis of Cancer. Indian J. Med. Res. 2021, 153, 431–445. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wémeau, J.-L.; Klein, M.; Sadoul, J.-L.; Briet, C.; Vélayoudom-Céphise, F.-L. Graves’ Disease: Introduction, Epidemiology, Endogenous and Environmental Pathogenic Factors. Ann. Endocrinol. 2018, 79, 599–607. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Ohtsuka, K.; Sato, A.; Kawaguchi, S.; Hashimoto, M.; Suzuki, Y. Effect of Steroid Pulse Therapy with and without Orbital Radiotherapy on Graves’ Ophthalmopathy. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2003, 135, 285–290. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthiesen, C.; Thompson, J.S.; Thompson, D.; Farris, B.; Wilkes, B.; Ahmad, S.; Herman, T.; Bogardus, C. The Efficacy of Radiation Therapy in the Treatment of Graves’ Orbitopathy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2012, 82, 117–123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bahn, R.S. Thyrotropin Receptor Expression in Orbital Adipose/Connective Tissues from Patients with Thyroid-Associated Ophthalmopathy. Thyroid. 2002, 12, 193–195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perros, P.; Žarković, M.P.; Panagiotou, G.C.; Azzolini, C.; Ayvaz, G.; Baldeschi, L.; Bartalena, L.; Boschi, A.M.; Nardi, M.; Brix, T.H.; et al. Asymmetry Indicates More Severe and Active Disease in Graves’ Orbitopathy: Results from a Prospective Cross-Sectional Multicentre Study. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 2020, 43, 1717–1722. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Viani, G.A.; Boin, A.C.; De Fendi, L.I.; Fonseca, E.C.; Stefano, E.J.; de Paula, J.S. Radiation Therapy for Graves’ Ophthalmopathy: A Systematic Review and Meta-Analysis of Randomized Controlled Trials. Arq. Bras. Oftalmol. 2012, 75, 324–332. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rundle, F.F.; Wilson, C.W. Development and Course of Exophthalmos and Ophthalmoplegia in Graves’ Disease with Special Reference to the Effect of Thyroidectomy. Clin. Sci. 1945, 5, 177–194. [Google Scholar]

- Bartley, G.B. Rundle and His Curve. Arch. Ophthalmol. 2011, 129, 356–358. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Le Moli, R.; Muscia, V.; Tumminia, A.; Frittitta, L.; Buscema, M.; Palermo, F.; Sciacca, L.; Squatrito, S.; Vigneri, R. Type 2 Diabetic Patients with Graves’ Disease Have More Frequent and Severe Graves’ Orbitopathy. Nutr. Metab. Cardiovasc. Dis. 2015, 25, 452–457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Viebahn, M.; Barricks, M.E.; Osterloh, M.D. Synergism between Diabetic and Radiation Retinopathy: Case Report and Review. Br. J. Ophthalmol. 1991, 75, 629–632. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lanzolla, G.; Vannucchi, G.; Ionni, I.; Campi, I.; Sileo, F.; Lazzaroni, E.; Marinò, M. Cholesterol Serum Levels and Use of Statins in Graves’ Orbitopathy: A New Starting Point for the Therapy. Front. Endocrinol. 2019, 10, 933. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Bartalena, L.; Kahaly, G.J.; Baldeschi, L.; Dayan, C.M.; Eckstein, A.; Marcocci, C.; Marinò, M.; Vaidya, B.; Wiersinga, W.M.; Ayvaz, G.; et al. The 2021 European Group on Graves’ Orbitopathy (EUGOGO) Clinical Practice Guidelines for the Medical Management of Graves’ Orbitopathy. Eur. J. Endocrinol. 2021, 185, G43–G67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Choi, J.H.; Lee, J.K. Efficacy of Orbital Radiotherapy in Moderate-to-Severe Active Graves’ Orbitopathy Including Long-Lasting Disease: A Retrospective Analysis. Radiat. Oncol. 2020, 15, 220. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartalena, L.; Marcocci, C.; Tanda, M.L.; Rocchi, R.; Mazzi, B.; Barbesino, G.; Pinchera, A. Orbital Radiotherapy for Graves’ Ophthalmopathy. Thyroid 2002, 12, 245–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Donaldson, S.S.; Bagshaw, M.A.; Kriss, J.P. Supervoltage Orbital Radiotherapy for Graves’ Ophthalmopathy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1973, 37, 276–285. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- La Rocca, M.; Leonardi, B.F.; Lo Greco, M.C.; Marano, G.; Finocchiaro, I.; Iudica, A.; Milazzotto, R.; Liardo, R.L.E.; La Monaca, V.A.; Salamone, V.; et al. Radiotherapy of Orbital and Ocular Adnexa Lymphoma: Literature Review and University of Catania Experience. Cancers 2023, 15, 5782. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spatola, C.; Liardo, R.L.E.; Milazzotto, R.; Raffaele, L.; Salamone, V.; Basile, A.; Foti, P.V.; Palmucci, S.; Cirrone, G.A.P.; Cuttone, G.; et al. Radiotherapy of Conjunctival Melanoma: Role and Challenges of Brachytherapy, Photon-Beam and Protontherapy. Appl. Sci. 2020, 10, 9071. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Common Terminology Criteria for Adverse Events (CTCAE).

- Baldeschi, L.; Macandie, K.; Koetsier, E.; Blank, L.E.C.M.; Wiersinga, W.M. The Influence of Previous Orbital Irradiation on the Outcome of Rehabilitative Decompression Surgery in Graves Orbitopathy. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2008, 145, 534–540.e1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Schaue, D.; Jahns, J.; Hildebrandt, G.; Trott, K.-R. Radiation Treatment of Acute Inflammation in Mice. Int. J. Radiat. Biol. 2005, 81, 657–667. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Douglas, R.S.; Kahaly, G.J.; Patel, A.; Sile, S.; Thompson, E.H.Z.; Perdok, R.; Fleming, J.C.; Fowler, B.T.; Marcocci, C.; Marinò, M.; et al. Teprotumumab for the Treatment of Active Thyroid Eye Disease. N. Engl. J. Med. 2020, 382, 341–352. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Rödel, F.; Kamprad, F.; Sauer, R.; Hildebrandt, G. Functional and molecular aspects of anti-inflammatory effects of low-dose radiotherapy. Strahlenther. Onkol. 2002, 178, 1–9. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Beige, A.; Boustani, J.; Bouillet, B.; Truc, G. Management of Graves’ Ophthalmopathy by Radiotherapy: A Literature Review. Cancer Radiother. 2024, 28, 282–289. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Verrienti, M.; Gagliardi, I.; Valente, L.; Stefanelli, A.; Borgatti, L.; Franco, E.; Galiè, M.; Bondanelli, M.; Zatelli, M.C.; Ambrosio, M.R. Late Orbital Radiotherapy Combined with Intravenous Methylprednisolone in the Management of Long-Lasting Active Graves’ Orbitopathy: A Case Report and Literature Review. Endocrine 2024, 85, 576–583. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- North, V.S.; Dolman, P.J.; Garrity, J.A.; Kazim, M. Disease Modulation Versus Modification: A Call for Revised Outcome Metrics in the Treatment of Thyroid Eye Disease. Ophthalmic Plast. Reconstr. Surg. 2024, 40, 156–160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Han, Q.; Mao, X.; Tian, S. A Retrospective Study on the Effectiveness of Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy for Thyroid Associated Ophthalmopathy at a Single Institute. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 17834. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakelkamp, I.M.M.J.; Tan, H.; Saeed, P.; Schlingemann, R.O.; Verbraak, F.D.; Blank, L.E.C.M.; Prummel, M.F.; Wiersinga, W.M. Orbital Irradiation for Graves’ Ophthalmopathy: Is It Safe? A Long-Term Follow-up Study. Ophthalmology 2004, 111, 1557–1562. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, J.W.; Han, S.H.; Son, B.J.; Rim, T.H.; Keum, K.C.; Yoon, J.S. Efficacy of Combined Orbital Radiation and Systemic Steroids in the Management of Graves’ Orbitopathy. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2016, 254, 991–998. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bartalena, L.; Marcocci, C.; Chiovato, L.; Laddaga, M.; Lepri, G.; Andreani, D.; Cavallacci, G.; Baschieri, L.; Pinchera, A. Orbital Cobalt Irradiation Combined with Systemic Corticosteroids for Graves’ Ophthalmopathy: Comparison with Systemic Corticosteroids Alone. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 1983, 56, 1139–1144. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcocci, C.; Bartalena, L.; Panicucci, M.; Marconcini, C.; Cartei, F.; Cavallacci, G.; Laddaga, M.; Campobasso, G.; Baschieri, L.; Pinchera, A. Orbital Cobalt Irradiation Combined with Retrobulbar or Systemic Corticosteroids for Graves’ Ophthalmopathy: A Comparative Study. Clin. Endocrinol. 1987, 27, 33–42. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Wang, S.-C.; Wu, J.; Xie, X.-Q.; Liu, X.-L.; Luo, Y.; Wang, F.; Li, Z.-P.; Qu, B.-L.; Kang, J.-B.; Wu, D.-B.; et al. Comparison of IMRT and VMAT Radiotherapy Planning for Graves’ Ophthalmopathy Based on Dosimetric Parameters Analysis. Eur. Rev. Med. Pharmacol. Sci. 2020, 24, 3898–3906. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Gorman, C.A.; Garrity, J.A.; Fatourechi, V.; Bahn, R.S.; Petersen, I.A.; Stafford, S.L.; Earle, J.D.; Forbes, G.S.; Kline, R.W.; Bergstralh, E.J.; et al. A Prospective, Randomized, Double-Blind, Placebo-Controlled Study of Orbital Radiotherapy for Graves’ Ophthalmopathy. Ophthalmology 2001, 108, 1523–1534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kahaly, G.J.; Rösler, H.P.; Pitz, S.; Hommel, G. Low- versus High-Dose Radiotherapy for Graves’ Ophthalmopathy: A Randomized, Single Blind Trial. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2000, 85, 102–108. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mourits, M.P.; van Kempen-Harteveld, M.L.; García, M.B.; Koppeschaar, H.P.; Tick, L.; Terwee, C.B. Radiotherapy for Graves’ Orbitopathy: Randomised Placebo-Controlled Study. Lancet 2000, 355, 1505–1509. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kahaly, G.J.; Subramanian, P.S.; Conrad, E.; Holt, R.J.; Smith, T.J. Long-Term Efficacy of Teprotumumab in Thyroid Eye Disease: Follow-Up Outcomes in Three Clinical Trials. Thyroid 2024, 34, 880–889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stiebel-Kalish, H.; Robenshtok, E.; Hasanreisoglu, M.; Ezrachi, D.; Shimon, I.; Leibovici, L. Treatment Modalities for Graves’ Ophthalmopathy: Systematic Review and Metaanalysis. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2009, 94, 2708–2716. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- X-Ray Treatment of Malignant Exophthalmos: A Report on 28 Patients—PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/13084727/ (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- The Efficacy of Intensity Modulated Radiation Therapy in Treating Thyroid-Associated Ophthalmopathy and Predictive Factors for Treatment Response|Scientific Reports. Available online: https://www.nature.com/articles/s41598-017-17893-y (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Petersen, I.A.; Kriss, J.P.; McDougall, I.R.; Donaldson, S.S. Prognostic Factors in the Radiotherapy of Graves’ Ophthalmopathy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 1990, 19, 259–264. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- A Randomized Controlled Trial of Orbital Radiotherapy Versus Sham Irradiation in Patients with Mild Graves’ Ophthalmopathy—PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/14715820/ (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Lee, V.H.F.; Ng, S.C.Y.; Choi, C.W.; Luk, M.Y.; Leung, T.W.; Au, G.K.H.; Kwong, D.L.W. Comparative Analysis of Dosimetric Parameters of Three Different Radiation Techniques for Patients with Graves’ Ophthalmopathy Treated with Retro-Orbital Irradiation. Radiat. Oncol. 2012, 7, 199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Spatola, C.; Militello, C.; Tocco, A.; Salamone, V.; Raffaele, L.; Migliore, M.; Pagana, A.; Milazzotto, R.; Chillura, I.; Pergolizzi, S.; et al. Intensity-Modulated Radiotherapy for Relapsed Malignant Pleural Mesothelioma. Future Oncol. 2016, 12, 67–71. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zygulska, A. Radiotherapy in the Treatment of Graves Ophthalmopathy-to Do It or Not? J. Ocul. Biol. Dis. Inform. 2009, 3, 1–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed][Green Version]

- Nakahara, H.; Noguchi, S.; Murakami, N.; Morita, M.; Tamaru, M.; Ohnishi, T.; Hoshi, H.; Jinnouchi, S.; Nagamachi, S.; Futami, S. Graves Ophthalmopathy: MR Evaluation of 10-Gy versus 24-Gy Irradiation Combined with Systemic Corticosteroids. Radiology 1995, 196, 857–862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Johnson, K.T.M.; Wittig, A.; Loesch, C.; Esser, J.; Sauerwein, W.; Eckstein, A.K. A Retrospective Study on the Efficacy of Total Absorbed Orbital Doses of 12, 16 and 20 Gy Combined with Systemic Steroid Treatment in Patients with Graves’ Orbitopathy. Graefes Arch. Clin. Exp. Ophthalmol. 2010, 248, 103–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Weissmann, T.; Lettmaier, S.; Donaubauer, A.-J.; Bert, C.; Schmidt, M.; Kruse, F.; Ott, O.; Hecht, M.; Fietkau, R.; Frey, B.; et al. Low- vs. High-Dose Radiotherapy in Graves’ Ophthalmopathy: A Retrospective Comparison of Long-Term Results. Strahlenther. Onkol. 2021, 197, 885–894. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gerling, J.; Kommerell, G.; Henne, K.; Laubenberger, J.; Schulte-Mönting, J.; Fells, P. Retrobulbar Irradiation for Thyroid-Associated Orbitopathy: Double-Blind Comparison between 2.4 and 16 Gy. Int. J. Radiat. Oncol. Biol. Phys. 2003, 55, 182–189. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Efficacy of B-Cell Targeted Therapy with Rituximab in Patients with Active Moderate to Severe Graves’ Orbitopathy: A Randomized Controlled Study—PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/25494967/ (accessed on 10 November 2024).

- Wiersinga, W.M. Advances in Treatment of Active, Moderate-to-Severe Graves’ Ophthalmopathy. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2017, 5, 134–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stan, M.N.; Garrity, J.A.; Carranza Leon, B.G.; Prabin, T.; Bradley, E.A.; Bahn, R.S. Randomized Controlled Trial of Rituximab in Patients with Graves’ Orbitopathy. J. Clin. Endocrinol. Metab. 2015, 100, 432–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Perez-Moreiras, J.V.; Gomez-Reino, J.J.; Maneiro, J.R.; Perez-Pampin, E.; Romo Lopez, A.; Rodríguez Alvarez, F.M.; Castillo Laguarta, J.M.; Del Estad Cabello, A.; Gessa Sorroche, M.; España Gregori, E.; et al. Efficacy of Tocilizumab in Patients With Moderate-to-Severe Corticosteroid-Resistant Graves Orbitopathy: A Randomized Clinical Trial. Am. J. Ophthalmol. 2018, 195, 181–190. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Marcocci, C.; Bartalena, L.; Bogazzi, F.; Bruno-Bossio, G.; Lepri, A.; Pinchera, A. Orbital Radiotherapy Combined with High Dose Systemic Glucocorticoids for Graves’ Ophthalmopathy Is More Effective than Radiotherapy Alone: Results of a Prospective Randomized Study. J. Endocrinol. Investig. 1991, 14, 853–860. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Douglas, R.S.; Dailey, R.; Subramanian, P.S.; Barbesino, G.; Ugradar, S.; Batten, R.; Qadeer, R.A.; Cameron, C. Proptosis and Diplopia Response With Teprotumumab and Placebo vs the Recommended Treatment Regimen With Intravenous Methylprednisolone in Moderate to Severe Thyroid Eye Disease: A Meta-Analysis and Matching-Adjusted Indirect Comparison. JAMA Ophthalmol. 2022, 140, 328–335. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Teprotumumab Efficacy, Safety, and Durability in Longer-Duration Thyroid Eye Disease and Re-Treatment: OPTIC-X Study—PubMed. Available online: https://pubmed.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/34688699/ (accessed on 10 November 2024).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by/4.0/).