Abstract

As the threat from malicious UAVs continues to intensify, accurate identification of individual UAVs has become a critical challenge in regulatory and security domains. Existing single-signal analysis methods suffer from limited recognition accuracy. To address this issue, this paper proposes a high-precision individual identification method for UAVs based on FFS-SPWVD and DIR-YOLOv11. The proposed method first employs a frame-by-frame search strategy combined with the smoothing pseudo-Wigner–Ville distribution (SPWVD) algorithm to obtain effective time–frequency feature representations of flight control signals. Building on this foundation, the YOLOv11n network is adopted as the baseline architecture. To enhance the extraction of time–frequency texture features from UAV signals in complex environments, a Multi-Branch Auxiliary Multi-Scale Fusion Network is incorporated into the neck network. Meanwhile, partial space–frequency selective convolutions are introduced into selected C3k2 modules to alleviate the increased computational burden caused by architectural modifications and to reduce the overall number of model parameters. Experimental results on the public DroneRFb-DIR dataset demonstrate that the proposed method effectively extracts flight control frames and performs high-resolution time–frequency analysis. In individual UAV identification tasks, the proposed approach achieves 96.17% accuracy, 97.82% mAP50, and 95.29% recall, outperforming YOLOv11, YOLOv12, and YOLOv13. This study demonstrates that the proposed method achieves both high accuracy and computational efficiency in individual UAV recognition, providing a practical technical solution for whitelist identification and group size estimation in application scenarios such as border patrol, traffic control, and large-scale events.

1. Introduction

With the rapid development of the low-altitude economy, small multi-rotor UAVs are profoundly transforming both industrial processes and daily life. Thanks to their wide field of view, compact size, and high maneuverability, they are widely employed in both military and civilian domains [1,2]. In the military context, amid persistently tense international relations, UAVs have demonstrated irreplaceable strategic value in critical combat operations in modern warfare [3]. In civilian applications, they are primarily used for geographic surveying, traffic monitoring, disaster relief, and agricultural operations [3,4,5,6]. Rapid advances in UAV technology have brought significant benefits. Alternatively, unauthorized “black flights” and unsafe operations pose serious threats to public safety and national security. These risks mainly arise from incomplete regulatory frameworks and the widespread use of unregistered UAVs [7,8,9,10]. Malicious activities include privacy violations, smuggling contraband, and attacks on critical infrastructure such as airports and nuclear power plants. As UAV use expands and small UAVs increasingly enter controlled airspace, effective countermeasures are urgently required. Detection is the foundation of such control measures. Due to UAVs’ small size and high-speed agility, modern anti-UAV systems primarily rely on a combination of sensors [11,12,13]. UAV detection mainly employs four approaches: radar, audio, visual, and radio-frequency (RF) [14]. Nevertheless, practical applications reveal limitations: radar is expensive and cannot operate effectively around obstacles, audio detection has a limited range, and visual detection is highly sensitive to lighting conditions. In contrast, RF-based detection technology effectively overcomes these constraints, offering superior environmental adaptability and detection stability.

In recent years, researchers worldwide have proposed many UAV identification methods. These methods fall into two main categories: traditional techniques and AI-based approaches. For example, Nie et al. [15] extracted the axial integral bispectrum (AIB), square integral bispectrum (SIB), and fractal dimension (FD) from UAV time-domain signals as RF fingerprints. They then applied principal component analysis (PCA) and domain component analysis for dimensionality reduction, followed by machine learning algorithms for classification. Nguyen et al. [16] classified UAVs using time-domain features such as packet count, average packet size, and average inter-arrival time. However, this method requires substantial prior information, limiting its practicality in real-world scenarios. C. Xu et al. [17] transformed single-transient control and video signals using the short-time Fourier transform (STFT) to obtain their time–frequency–energy distribution characteristics. PCA was used for dimensionality reduction. The resulting RF signal features were then used to train support vector machine (SVM) and k-nearest neighbor (KNN) classifiers to detect and count intruding UAVs. Nevertheless, due to the inherent limitations of STFT, the resulting images often fail to capture detailed RF signal information, leading to suboptimal recognition performance. REN J et al. [18] achieved a 100% background positive detection rate using fast frequency estimation combined with time-domain correlation analysis. However, their maximum individual recognition rate of only 68.62% remains insufficient for practical applications. In summary, although these studies demonstrate the feasibility of UAV recognition using traditional algorithms, such methods generally fall short of meeting the requirements for high-precision recognition.

Meanwhile, as deep learning (DL) theory has advanced, many researchers have developed efficient DL architectures for UAV radio-frequency (RF) detection. For example, T. Huynh-The et al. [19] introduced an RF-based detection system using the high-performance convolutional neural network RF-UAVNet to detect and classify UAV models, achieving a detection accuracy of 99.85% and a classification accuracy of 98.53%. Medaiyese et al. [20] applied the wavelet scattering transform to convert UAV flight control signals into scatter plots, which were then input into a convolutional neural network (CNN) for training. Kumbasar et al. [21] transformed one-dimensional RF signals into two-dimensional representations—spectrograms, persistence spectrograms, and percentile spectrograms—and utilized their HMFFNet model for UAV classification. Since UAV RF signals are typically non-stationary, many studies employ time–frequency analysis algorithms to extract spectral features for identification. Basak S et al. [22] proposed a novel UAV detection and model classification framework based on the YOLO algorithm. Delleji [23] improved the baseline YOLOv8 model to develop RF-YOLO. By converting UAV signals into time–frequency plots, RF-YOLO achieved a mean average precision (mAP) of 0.9213, a precision of 0.9800, and a recall of 0.9750. The model was also evaluated using a time–frequency map dataset generated from customized UAV remote controller RF signals under various signal-to-noise ratios (SNRs). The latest RT-DETR (Real-Time Detection Transformer) models, based on the Transformer architecture [24,25], have optimized both speed and accuracy for real-time tasks. Nonetheless, their overall performance has not yet surpassed that of some improved YOLO models.

Overall, researchers worldwide have achieved high UAV detection and model recognition performance using general object detection methods, and many studies further optimize these approaches. However, existing UAV detection and classification methods are primarily limited to single-aircraft or heterogeneous multi-aircraft scenarios. They struggle to achieve high-precision identification of individual UAVs in scenarios involving multiple flights of the same model. For applications such as border patrol, traffic control, and major sporting events, authorized and unauthorized UAV signals may coexist, while existing full-band suppression methods indiscriminately disrupt all communications. Therefore, developing efficient feature extraction and classification techniques capable of distinguishing different individuals of the same UAV model is critical.

Based on the above analysis, existing methods show two main limitations in identifying individual UAVs of the same model. In complex electromagnetic environments, traditional approaches struggle to separate target signals and rely heavily on handcrafted features. In contrast, YOLO-based visual methods use low-resolution spatiotemporal maps, which limits their ability to capture discriminative steady-state and transient features. In addition, the deep network downsampling process can obscure fine-grained signal details under high-level semantic representations. To address these issues, this study improves both signal representation and network architecture. High-resolution preprocessing is used to enhance signal purity and feature separability. A lightweight and task-specific network is then designed to achieve robust individual recognition while suppressing interference. By combining signal processing with deep learning, the proposed approach improves discrimination in distinguishing different individuals of the same UAV model.

The main innovations and contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

- High-Efficiency Preprocessing Method: We propose a frame-by-frame search–based smoothing pseudo-Wigner–Ville distribution (FFS-SPWVD) preprocessing method [26]. This approach enables the independent extraction of flight control data frames while preserving high time–frequency resolution, thereby significantly enhancing the representation of signal features in time–frequency maps.

- High-Precision Feature Fusion Network: A Multi-Branch Auxiliary Multi-Scale Fusion Feature Pyramid Network (MA-MFFPN) is designed to replace the original YOLOv11 neck network. This architecture preserves shallow-layer features as auxiliary information within the deep network, thereby enhancing multi-scale feature fusion and improving recognition accuracy.

- Lightweight Convolution Module: To reduce the computational cost introduced by the modified neck structure, several C3k2 modules in YOLOv11 are replaced with IPC-C3k2 modules. These modules use Partial Space–Frequency Selective Convolution (PSFSConv) to limit computation while improving key feature extraction and reducing local information loss.

2. Materials and Methods

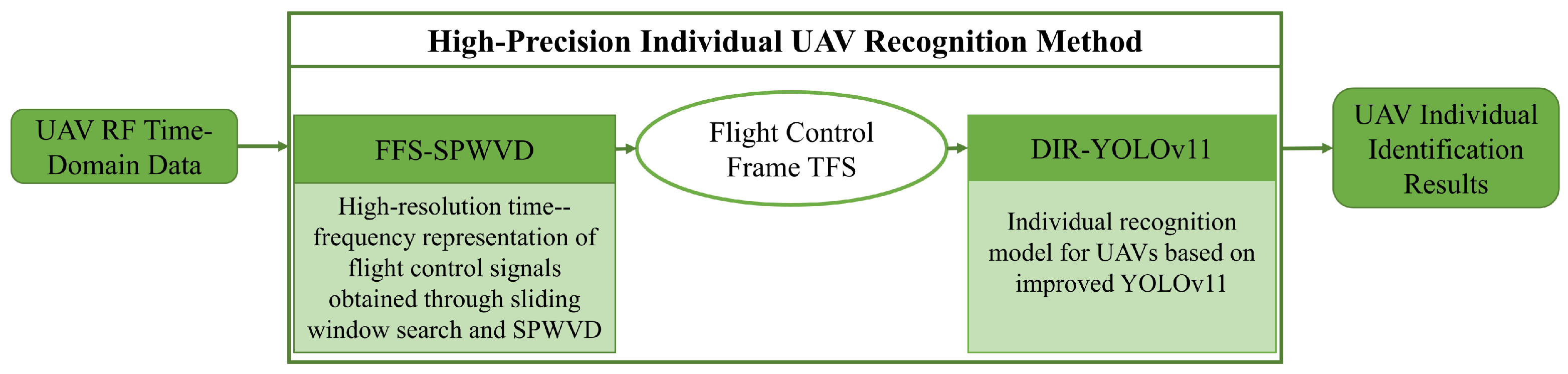

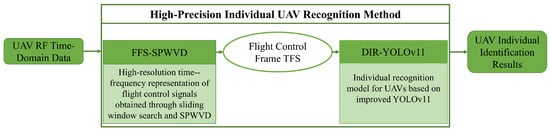

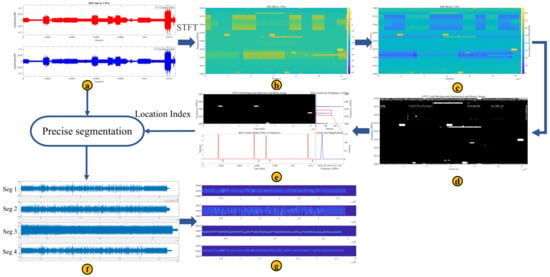

This section describes the core architecture of the proposed high-precision individual UAV identification method, which mainly consists of the signal preprocessing algorithm FFS-SPWVD and the individual UAV recognition model DIR-YOLOv11. The overall architecture is illustrated in Figure 1. The received UAV communication chain data first undergoes preprocessing to generate high-resolution time–frequency spectra (TFS). These spectra are then used to train and validate the individual recognition model, which ultimately outputs results that distinguish between different UAV individuals.

Figure 1.

Architectural diagram of individual identification method.

2.1. Datasets

All data used in this study are sourced from the DroneRFb-DIR [18] public dataset, provided by Zhejiang University. This dataset records communication signals between UAVs and their remote controllers using radio-based acquisition equipment. It includes six UAV types in urban environments, with three distinct individuals per type. The dataset comprises raw I/Q data, with each segment containing at least 4 million samples. The signals cover the 2.4–2.48 GHz frequency range, sampled at 80 MHz, with a duration of 50 ms per segment. In addition to the UAVs’ flight control and video transmission signals, the dataset also captures interference from surrounding devices. This study assumes that three samples from each UAV category are sufficient to represent the main signal feature differences observed in practice. As a result, the experiments mainly evaluate recognition performance under homogeneous dataset conditions.

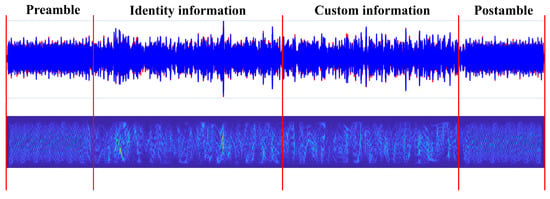

UAV identification typically relies on flight control signals, which are present in all UAV models. Most flight control signals employ frequency-hopping technology. The structure of commercial UAV flight control signals is shown in Figure 2 and consists of a preamble, identity information, custom data, and a postamble. The preamble and postamble enable channel estimation and synchronization. They also help the UAV identify flight control signals and determine the start and end of each frame. Identity information is used to verify whether the signal is transmitted by a matching remote controller. Custom data contains commands and other relevant information. Based on the analysis of UAV flight control signal structures, the following key conclusions can be drawn for individual UAV identification:

- 1.

- For flight control signals originating from the same UAV, the preamble and postamble codes and identity information are identical, while the custom data differs;

- 2.

- For different individuals of the same model, the preamble and postamble codes of their flight control signals may be identical, but the identity information and custom data differ.

Figure 2.

Frame structure of UAV flight control signals.

Figure 2.

Frame structure of UAV flight control signals.

In summary, accurate individual UAV identification requires complete flight control signal frames. By exploiting the unique signal patterns of each UAV’s flight control system, it is possible to determine the transmission patterns and operating frequencies of authorized UAVs stored in the database. This information enables the development of an electromagnetic intelligent suppression scheme based on precise spatiotemporal–frequency planning [27,28].

2.2. FFS-SPWVD

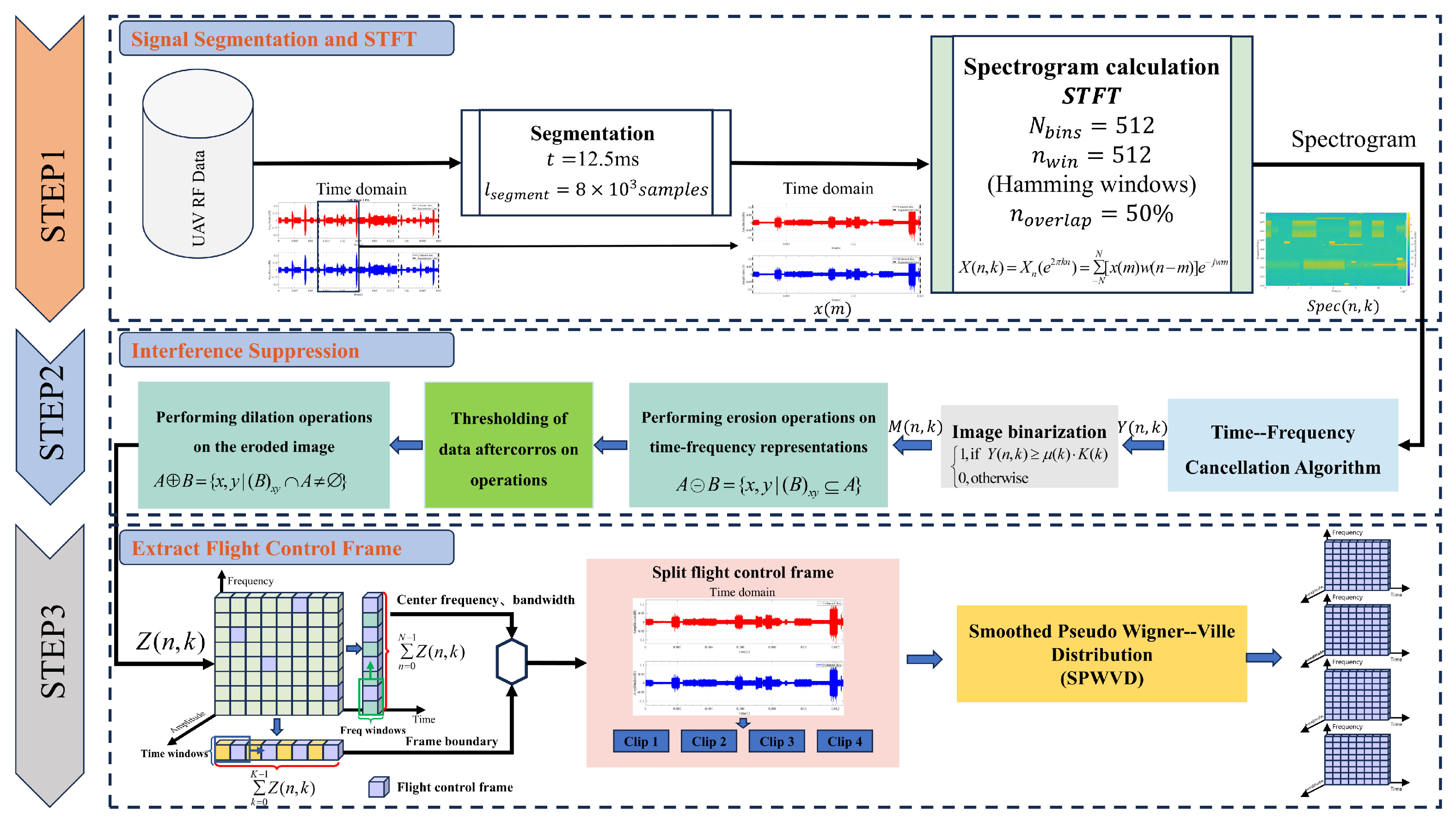

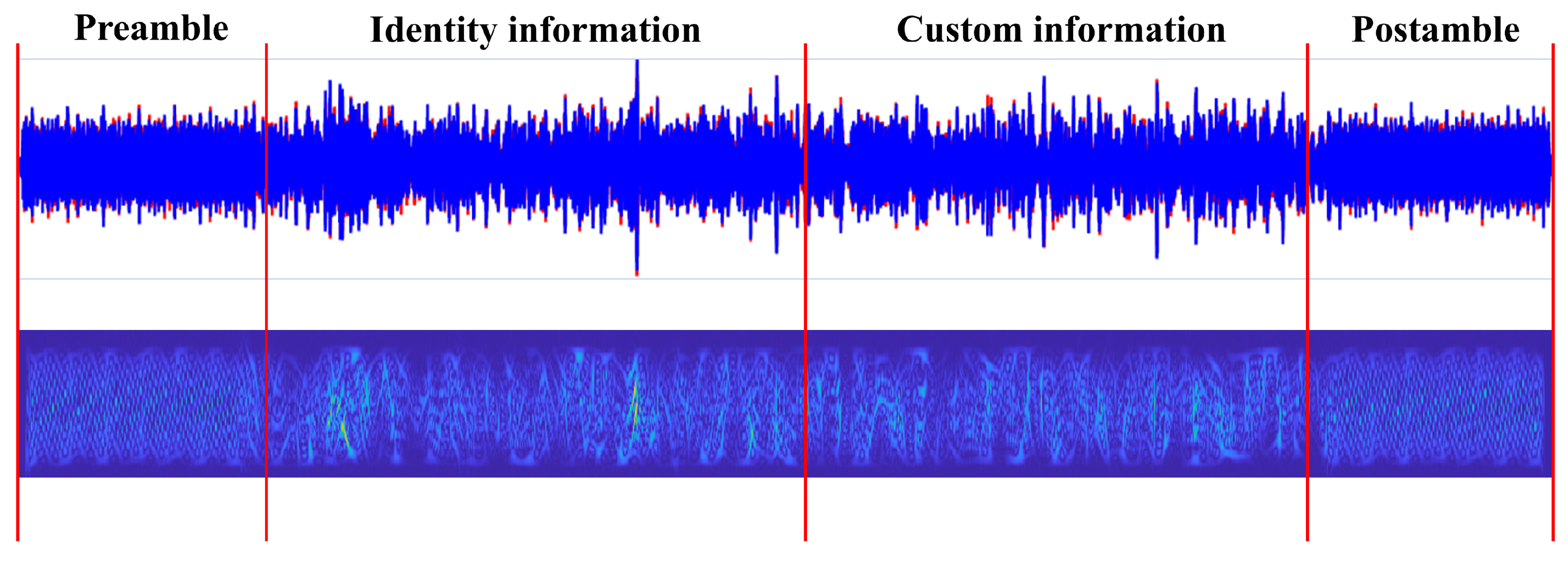

This section introduces the FFS-SPWVD preprocessing method, with its algorithmic flow illustrated in Figure 3. First, a low-resolution time–frequency analysis is performed on the radio signal. Then, using a coarse search, the flight control signal is extracted in the time domain based on the search results and subjected to high-resolution time–frequency analysis. The algorithm enables precise localization of flight control frames while providing high-resolution time–frequency representations.

Figure 3.

FFS-SPWVD Algorithm Flowchart.

2.2.1. Signal Segmentation and STFT

First, the UAV communication signal is loaded, and the time-domain signal is segmented into 1,000,000 samples. A low-resolution time–frequency analysis is then performed using the widely applied short-time Fourier transform (STFT) [29]. For a given signal , the STFT is defined as

In the equation, ∗ denotes complex conjugation; denotes the window function; f denotes the signal frequency; t denotes time; and denotes the coordinate position of the window function in the time domain. Its discrete form is expressed as

Here, denotes the input digital signal. By varying the value of n, the signal is segmented using . The resulting STFT output is then converted into a time–frequency spectrum by taking the squared magnitude. The STFT transforms the signal from the time domain into the time–frequency domain, where the joint time–frequency characteristics are represented as a two–dimensional time–frequency map. Subsequent image processing is performed based on this time–frequency representation.

2.2.2. Interference Suppression

To suppress interference from UAV video transmission and other fixed-frequency signals during flight controller signal frame extraction, a time–frequency cancellation algorithm [30] is applied. First, the mean value cof the time–frequency spectrum is computed across all frequency components, where N denotes the number of signal points.

From Equation (4), the mean energy of each frequency component is calculated, and the maximum mean energy is denoted by . The number of points within this component whose energy exceeds the mean value is then counted and denoted by M, from which the time–frequency cancellation factor d is derived. By subtracting from the original time–frequency spectrum, the canceled spectrum is obtained. Conversely, the energy of the frequency-hopping signal points in the canceled spectrum is relatively low. Therefore, the canceled spectrum is multiplied by the time—frequency cancellation factor d to enhance these components, yielding the final spectrum . The corresponding expression is given as follows:

During the coarse time–frequency search for UAV flight control signals, interference strongly affects detection accuracy. Therefore, image processing techniques are applied to the two-dimensional time–frequency map. First, row-wise mean binarization is performed on the time–frequency map to obtain , which eliminates pits caused by power cancellation algorithms that suppress fixed-frequency signals. Subsequently, morphological filtering based on the opening operation is applied to remove isolated points and interference from small connected components [31]. Mathematical morphology consists of two fundamental operations: erosion and dilation. By combining erosion and dilation, opening and closing operations are formed. Erosion removes specific boundary points of an object using a structuring element, resulting in a reduction in the object’s area by a corresponding number of points. The definition of erosion is given as follows:

Morphological dilation refers to the process of merging background pixels adjacent to the target region within its spatial constraints imposed by structural element B. The mathematical expression for this transformation is

Given the influence of the time–frequency transformation results and the inherent characteristics of the signal itself, its structural elements approximate a square configuration. Therefore, processing is performed using square structural elements [32].

2.2.3. Extract Flight Control Frames

After morphological filtering, the time–frequency map is projected onto one-dimensional curves along both the time and frequency axes, and a double-window sliding search algorithm is subsequently applied. In the double-window sliding search algorithm [33], a window of length slides along either the time-domain or frequency-domain projection of the time–frequency map. The window operates as a queue, storing the collected signal samples in a first-in, first-out (FIFO) manner. During the sliding process, the energies of the left and right halves of window are calculated as follows:

Then, the ratio of to is calculated to obtain a new metric:

By analyzing the variation pattern of , the start and end positions of the signal can be determined. Specifically, when the sliding window contains only noise or only the UAV signal, the energies in the left and right halves of the window are approximately equal, that is, . In this case, remains relatively flat and close to 1. As the window slides across the one-dimensional sequence, gradually increases, and increases accordingly. When the starting point of the signal reaches the center of the window, attains its maximum value. Therefore, the location of this peak corresponds to the start of the UAV signal. Similarly, when the end point of the UAV signal reaches the center of the window, reaches its minimum value. Based on this behavior, a threshold can be set to determine the signal start point. Using this algorithm, the frame start and end times of the UAV flight control signal are obtained, along with the corresponding frame bandwidth and center frequency. The estimated frame start and end times are used to segment the raw time-domain signal. The segmented signal is then processed using the SPWVD to obtain a higher-resolution time–frequency representation. The estimated center frequency and bandwidth are further used to segment the time–frequency map along the frequency axis. The SPWVD of the signal is defined as follows:

In the formula, represents the SPWVD of the signal , while and denote the window functions in the time and frequency domains, respectively, with u representing the frequency delay. The two-dimensional time–frequency map generated by this algorithm serves as the input for dataset construction and subsequent deep learning models.

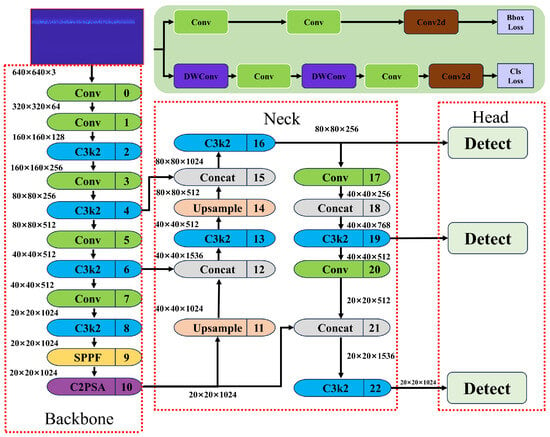

2.3. DIR-YOLOv11 Model

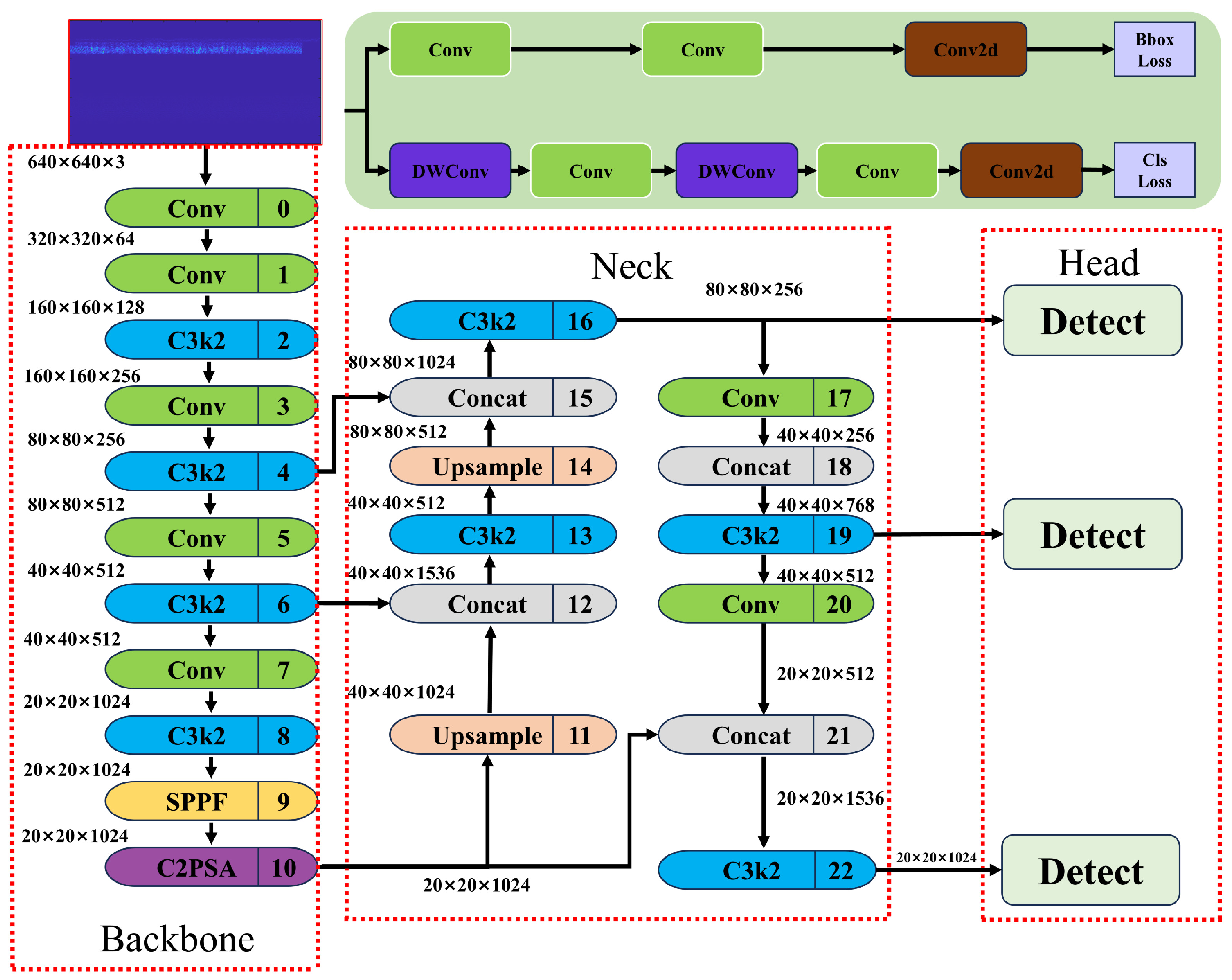

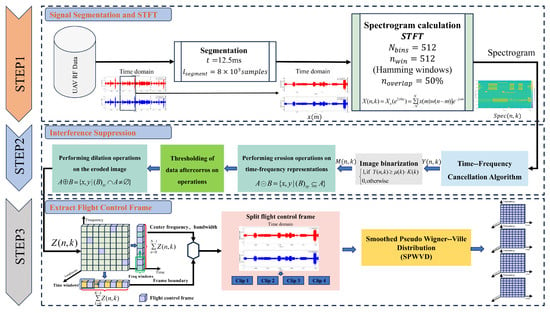

The aforementioned preprocessing algorithm performs the initial characterization of UAV signal features, which represents only the first stage of the complete recognition framework. The subsequent steps—feature extraction and classification—are equally critical for building a robust and accurate recognition system. This study employs the widely used lightweight YOLO model to perform individual classification tasks. YOLOv11 [34], released by the Ultralytics team in 2024 as an iteration of the YOLOv8 series, has the underlying architecture illustrated in Figure 4.

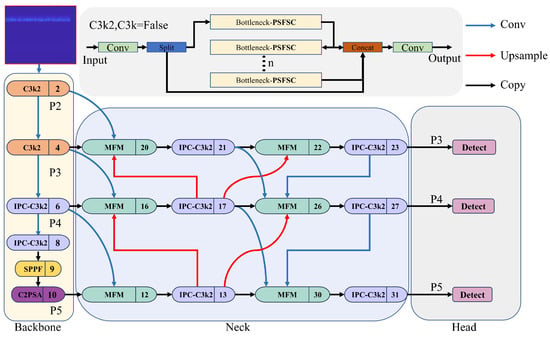

Figure 4.

YOLOv11 basic model architecture diagram.

The core innovations of this version are reflected in three modules: C3k2, C2PSA, and the detection head. The C3k2 module introduces variable convolutional kernels and a dual-branch parallel design based on the CSP-Bottleneck architecture, enhancing the extraction of multi-scale contextual information. The C2PSA module dynamically enhances channel responses by combining parallel multi-scale convolutions with spatial attention mechanisms. Additionally, in the detection head, conventional convolutions in the classification branch are replaced with depthwise separable convolutions, significantly reducing computational complexity while effectively maintaining detection accuracy.

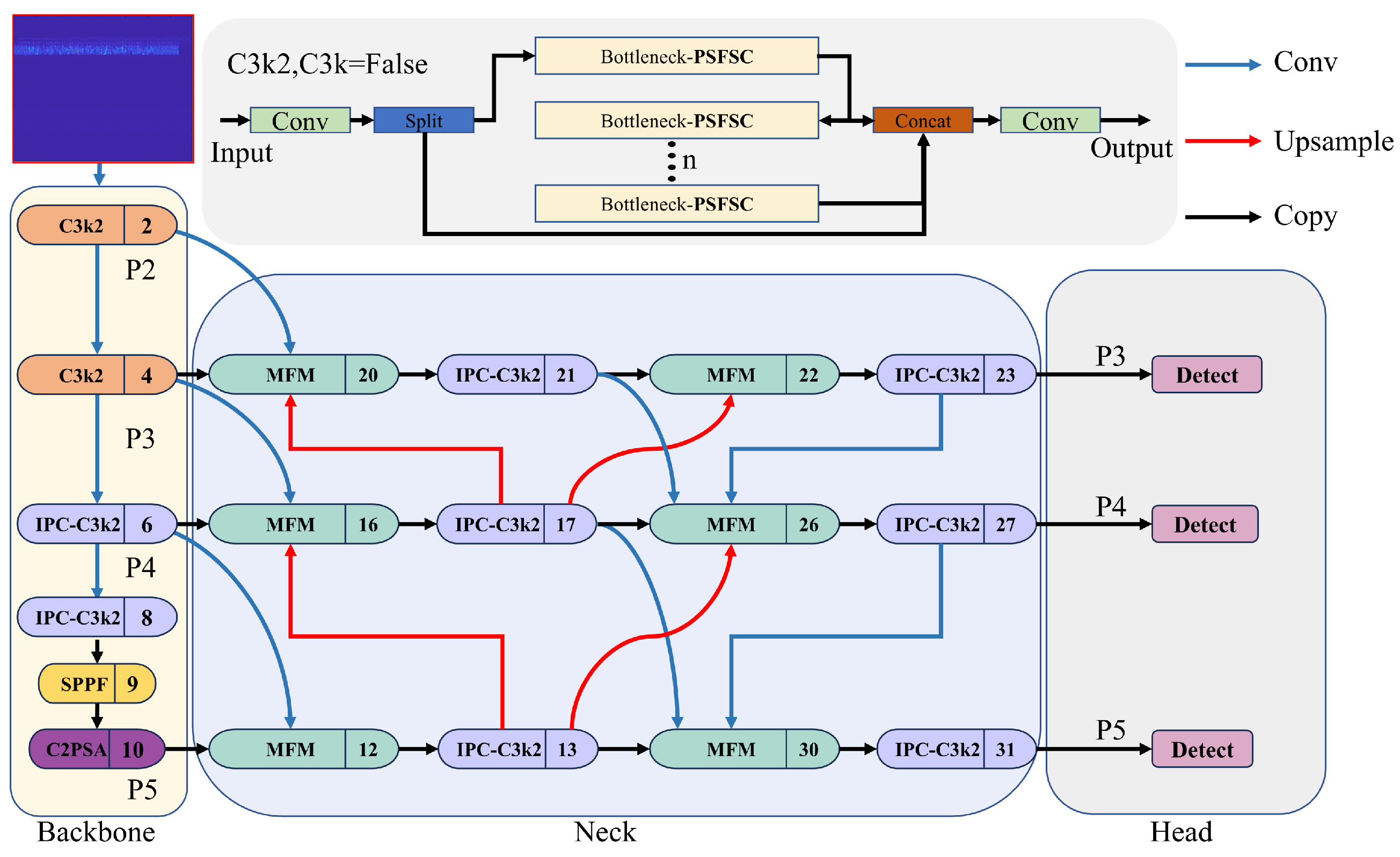

Particularly, the baseline model does not achieve sufficient accuracy for individual identification. To improve YOLOv11’s ability to recognize the time–frequency texture of RF signals from different drones, while maintaining a lightweight design and high recognition efficiency, two key architectural modifications were made to the YOLOv11n model. This led to DIR-YOLOv11, which is better suited to practical real-world applications. The structure of the improved model is illustrated in Figure 5.

Figure 5.

DIR-YOLOV11 model architecture diagram.

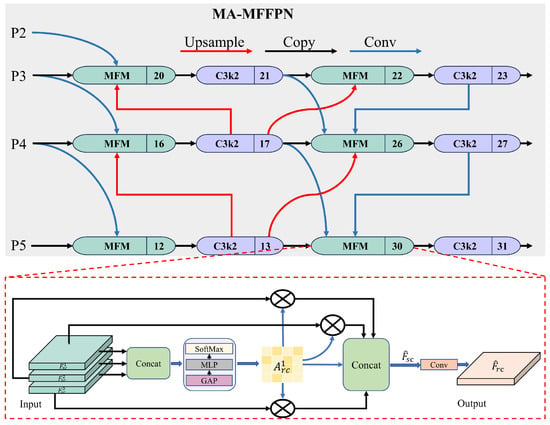

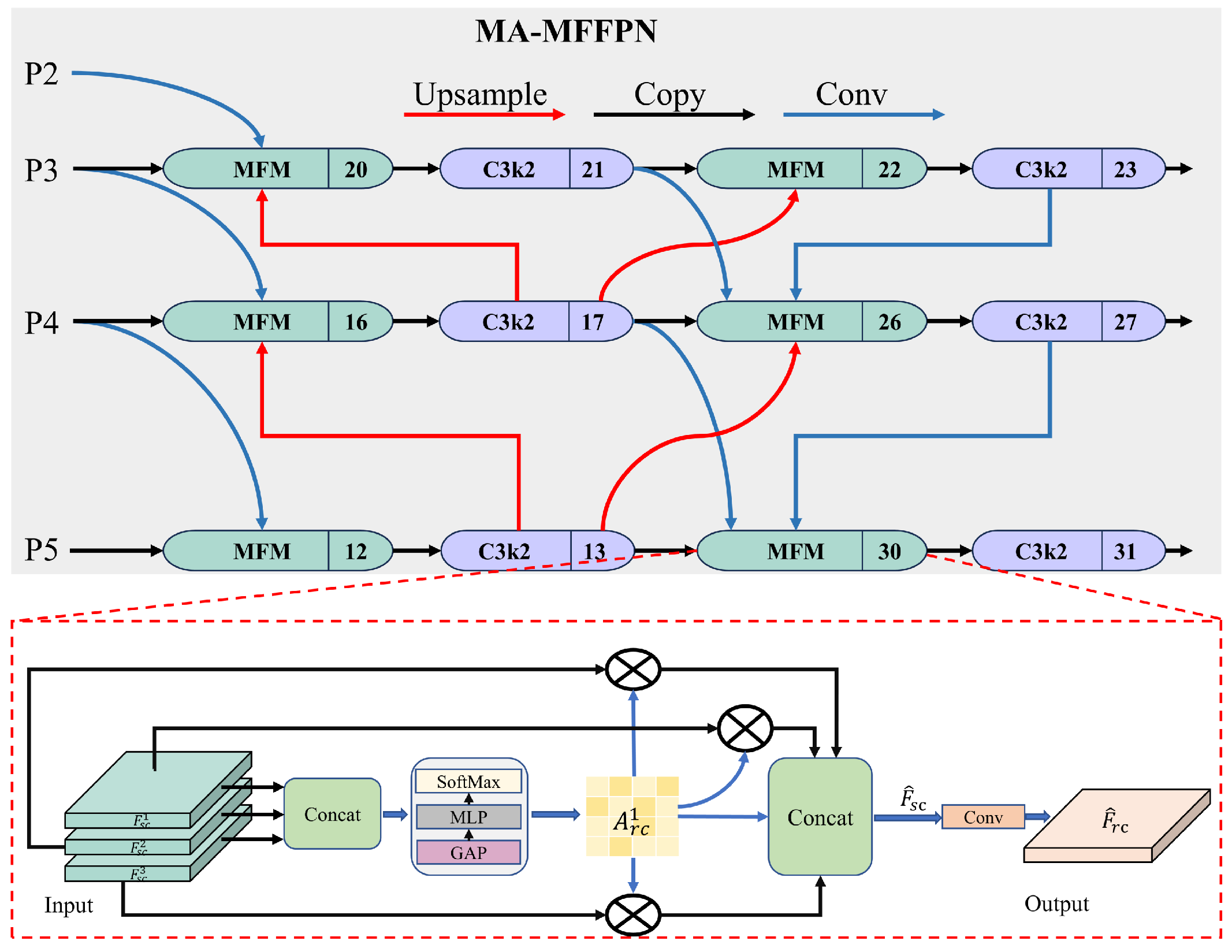

2.3.1. MA-MFFPN

Within the YOLOv11 base framework, the Backbone extracts multi-scale image features, while the neck is responsible for fusing these features. The neck structure is based on the Feature Pyramid Network (FPN), which primarily combines multi-scale features through upsampling and concatenation, leveraging the C3K2 module to facilitate the fusion process. Reciprocally, this structure can lead to partial loss of feature information during multi-level downsampling. Moreover, the FPN assigns equal weights to all inputs during feature fusion, lacking the ability to selectively enhance critical features. In complex scenes, redundant or low-quality features can be introduced into the fusion stage, resulting in background interference and increasing the risk of false positives. Additionally, existing fusion mechanisms have limited efficiency in feature reuse and lack adaptive filtering and enhancement during cross-scale feature propagation. As a result, shallow-level features (e.g., P3) can be overshadowed or overwritten by high-level semantic features (e.g., P5) during propagation to deeper layers. This reduces the model’s sensitivity to fine details and lowers detection performance.

To address the issues mentioned above, we combine the original neck network with the Multi-Branch Assisted FPN (MAFPN) [35] and introduce a modulation fusion module (MFM) [36] to propose a novel neck network: the Multi-Branch Assisted Multi-Scale Fusion FAN (MA-MFFPN). The overall structure of MA-MFFPN is shown in Figure 6. The MFM plays a central role in feature fusion. To unify the scales of feature maps (P2, P3, P4, P5) received at different levels, a 1 × 1 convolution is applied to each, producing . These processed feature maps are then concatenated using a Concat module. Subsequently, the corresponding feature weight matrix is obtained using a global average pooling (GAP) layer, a multi-layer perceptron (MLP), and a SoftMax module. Each scale’s features are then multiplied by the weight matrix and fused via concatenation to produce the multi-scale fusion feature . The convolutional layer uniformly processes the scales of the concatenated results to yield the output feature , which is used for feature fusion in the MAFPN.

Here, ⊙ denotes the dot product operation, and represents the uniform scaling of the convolutional layer.

Figure 6.

MA-MFFPN structural diagram.

Figure 6.

MA-MFFPN structural diagram.

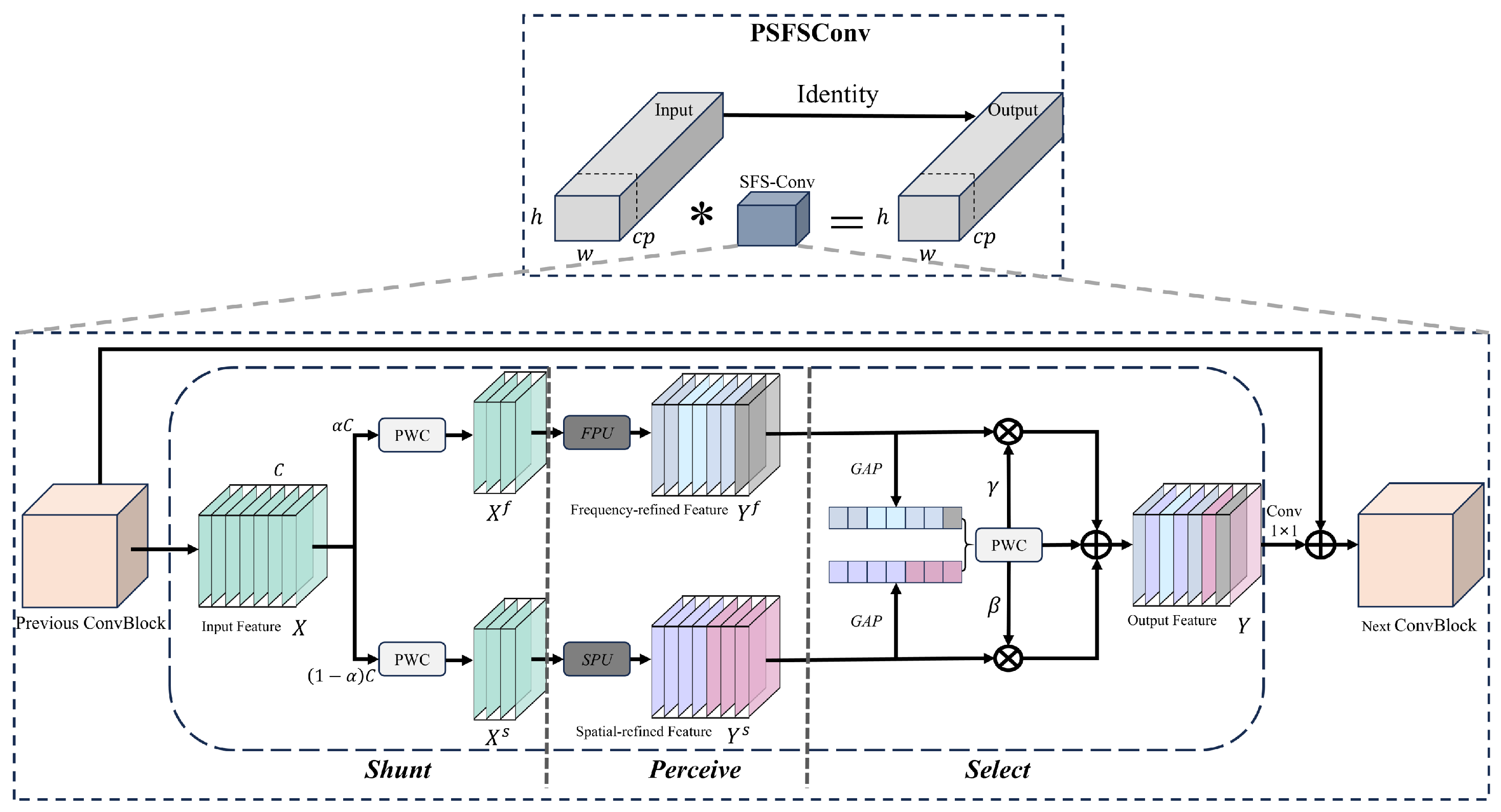

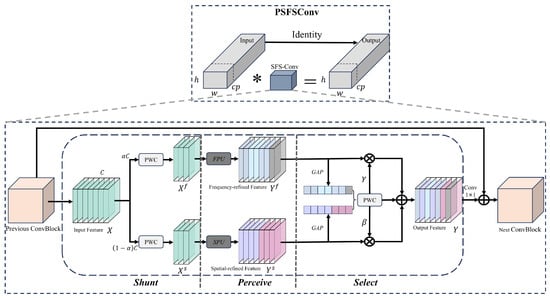

2.3.2. IPC-C3k2

Introducing the MA-MFFPN structure into the original YOLOv11 model significantly enhances the extraction of effective features and improves detection accuracy. Notably, it also substantially increases computational complexity and model size, consuming more computational resources and memory in practical applications. In the foundational YOLOv11 architecture, standard convolutional (Conv) units are extensively used in subsampling, feature extraction, and multi-scale feature fusion. Although traditional convolutions perform well in visual feature extraction and encoding, their globally consistent processing can generate redundant responses when processing irrelevant regions. This limitation is particularly evident in UAV RF signal time–frequency maps. Since UAV RF signals operate across most of the ISM band, significant co-channel interference is common. Traditional convolutions struggle to selectively emphasize critical regions, leading to indiscriminate encoding of both interference and valid signals, which compromises the model’s perceptual performance. To address this, the Partial Convolution (PConv) mechanism [37] is introduced. PConv selectively applies convolutions only to valid pixels within the input feature map. Using a dynamic masking mechanism, it suppresses background interference and focuses on target regions, enhancing the specificity and robustness of feature representation. Simultaneously, PConv eliminates unnecessary computations, reducing memory usage and parameter count without sacrificing performance. Assuming the input and output channels are identical, the number of floating-point operations (FlOPs) for Conv and PConv are and , respectively.

In the above two equations, h and w represent the height and width of the input feature map, respectively; k denotes the size of the convolution kernel; c is the number of channels in a standard convolution; and is the number of channels involved in the PConv operation. , and the computational cost (FLOPs) of PConv is only 6.25% of that of a standard convolution.

While the introduction of the PConv mechanism improves the model’s focus on effective regions, its core still relies on standard convolution operations (Conv). This structure has limitations in recognizing the subtle spatiotemporal texture features of UAV flight control signals. Because the spatiotemporal maps of flight control signals are generated through spatiotemporal analysis algorithms, the texture features in these maps are often subtle and easily affected by algorithmic artifacts and noise. Consequently, relying solely on standard convolutions to recognize objects based on coarse outlines presents significant challenges in practical applications. To address this, we propose enhancing PConv by replacing its standard convolutions with space–frequency selective convolutions (SFS-Conv) [38], forming the Partial Space–Frequency Selective Convolution (PSFSConv) module, as illustrated in Figure 7. In this study, the PSFSConv module is integrated into the C3k2 feature extraction module, replacing the convolutional layers within the residual blocks of C3k2. This results in the improved Partial Convolutional C3k2 (IPC-C3k2). The integration of IPC-C3k2 significantly enhances the performance of the feature extraction module while reducing overall computational cost and model complexity. The improved IPC-C3k2 replaces all C3k2 layers in the neck network and partially replaces C3k2 layers in the Backbone. Subsequent experiments demonstrate that this enhancement improves overall recognition accuracy while reducing model size for individual UAV identification.

Figure 7.

PSFSConv structural diagram. ∗ denotes convolution operation.

3. Results

3.1. Experimental Environment and Evaluation Metrics

To evaluate the performance of DIR-YOLOv11 in individual UAV recognition tasks, comparative experiments were conducted with several representative algorithms under identical training configurations. To ensure reproducibility and fairness, all models were trained from scratch on a self-constructed UAV dataset without using any pre-trained weights. The experimental environment settings and training parameters are summarized in Table 1 and Table 2, respectively.

Table 1.

Configuration of experimental environment.

Table 2.

Training parameter settings.

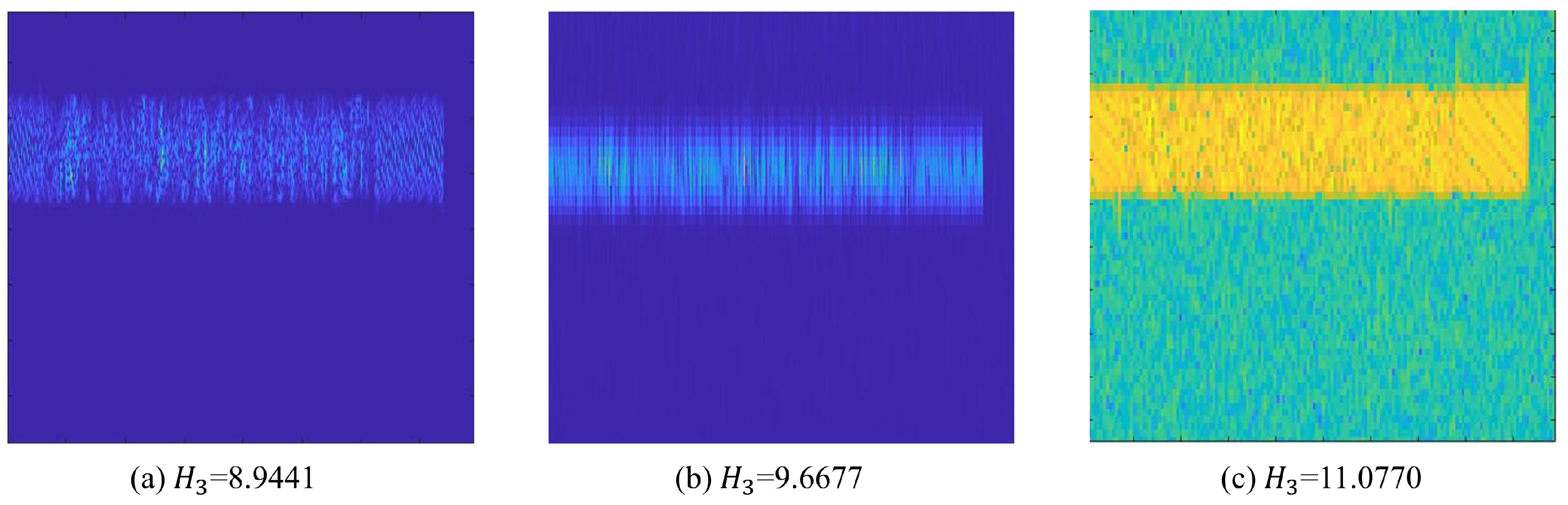

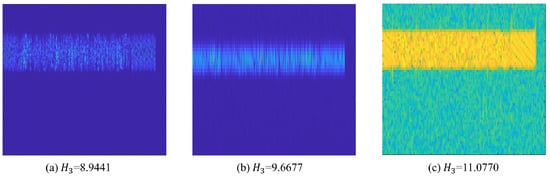

In this study, individual UAV identification relies on high-resolution time–frequency images, which are typically selected based on visual quality. However, using subjective perception to distinguish images can introduce significant errors. To address this, we introduce Rényi entropy [39] as an objective metric for evaluating the quality of spatiotemporal analysis. Rényi entropy generalizes several entropy concepts, including Hartley entropy [40], Shannon entropy [41], collision entropy, and minimum entropy. For quantitative analysis, Rényi entropy is processed using volume normalization, expressed as follows:

In the equation, m and k denote the number of points in the time and frequency domains, respectively; represents the time–frequency distribution of the signal; and is the order of the Rényi entropy. It has been shown that when , the Rényi entropy provides an optimal evaluation for time–frequency analysis [42].

Additionally, this study uses precision, recall, mean average precision (mAP), gigaflops per second (GFLOPs), and the number of model parameters as metrics to evaluate model performance. The individual UAV recognition system integrates both detection and classification. To comprehensively evaluate the recognition performance of the proposed method, this study uses Top-1 accuracy as the primary evaluation metric. The definitions of these evaluation metrics are as follows:

Among these, , , and represent true positives, false positives, and false negatives, respectively, while N denotes the number of categories.

3.2. Signal Preprocessing Results and Analysis

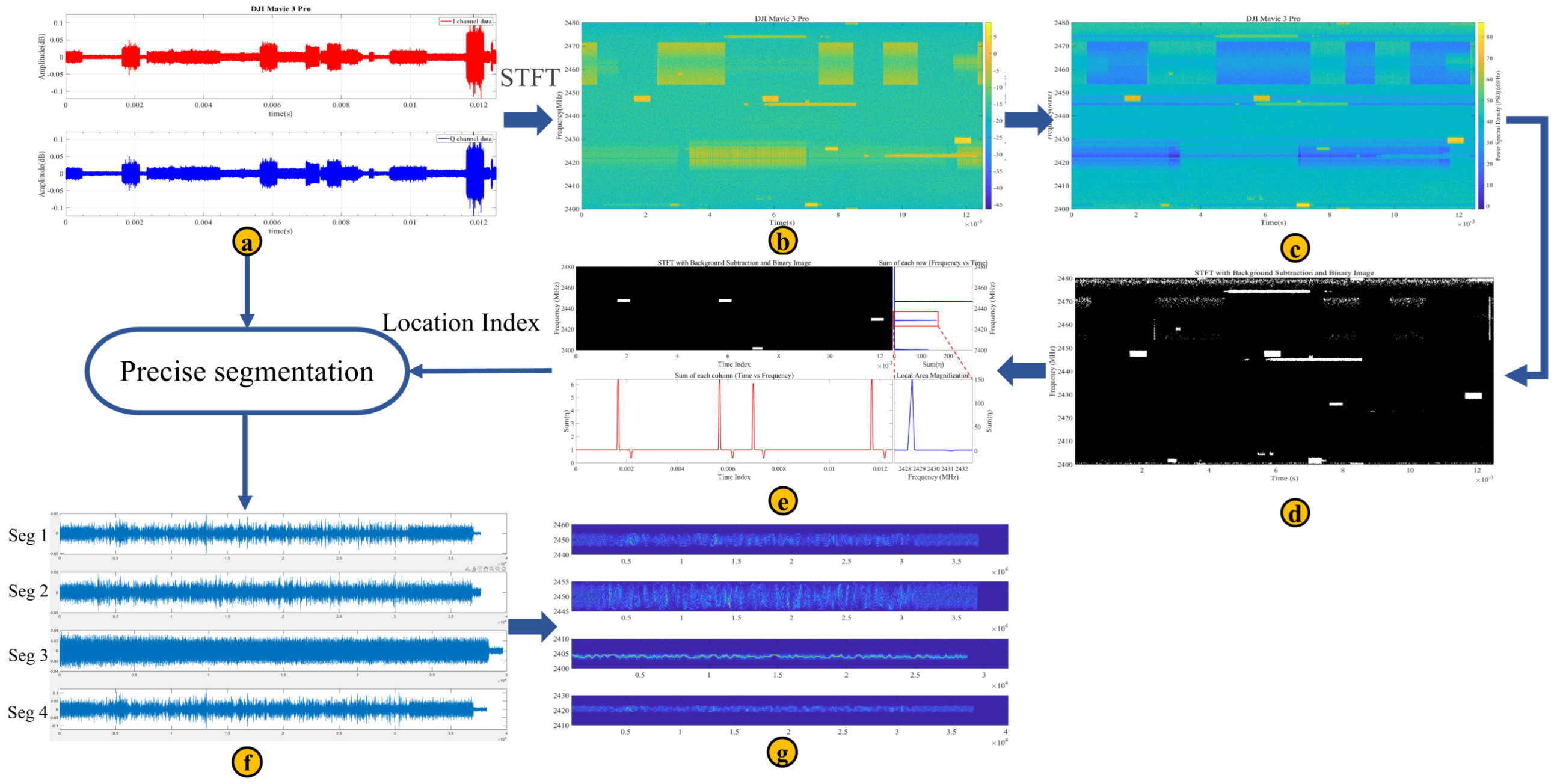

To obtain complete flight control signal frames for individual identification, the FFS-SPWVD algorithm was applied to the DroneRFb-DIR dataset. The workflow is illustrated in Figure 8. Using the DJI Mavic 3 Pro signal as an example, the UAV’s RF time-domain IQ signal is first pre-segmented and then transformed using a short-time Fourier transform (STFT) with a window length of 2048 points, producing a low-resolution time–frequency map (b). Next, a power cancellation algorithm is applied to generate a time–frequency map (c) that suppresses video transmission signals and persistent long-term interference. Adaptive row thresholding is then used to produce a binary image (d). Morphological filtering with a square structuring element removes isolated points and noise pixels. To prevent division by zero in the double-window sliding algorithm, the binary result is incremented by +1. Using the known frame length and bandwidth parameters [43] of the flight control signal for this UAV model as the time and frequency window lengths, a double-window sliding search algorithm is applied to the morphologically filtered result to determine the start time, end time, and bandwidth of each flight control signal frame. The raw time-domain IQ signal is then segmented based on these parameters, as shown in Figure (f). Each segment undergoes SPWVD time–frequency analysis with time and frequency window lengths of 127 and 512, respectively, yielding the final high-resolution time–frequency map collection of the UAV flight control signal frame (g).

Figure 8.

Preprocessing results of UAV signals. (a) UAV RF time-domain IQ signal. (b) STFT time−frequency plot. (c) Power cancellation result. (d) Binarization result. (e) Morphological filtering and double-window sliding search result. (f) Flight control signal frame segment. (g) Flight control frame time–frequency spectrum plot.

To evaluate the performance of different time−frequency analysis algorithms, we compared the time−frequency maps obtained using STFT and CWT with those produced by SPWVD in our algorithm. The quality of these maps was assessed using Rényi entropy as the evaluation metric, and the results are shown in Figure 9. Among the methods tested, the time−frequency map generated by STFT exhibits the highest Rényi entropy, followed by CWT, while SPWVD yields the lowest Rényi entropy. This indicates that the time–frequency distribution obtained by SPWVD is more concentrated and better captures subtle variations in the instantaneous frequency of the time–frequency fingerprints.

Figure 9.

Performance comparison of time–frequency analysis algorithms. (a) SPWVD. (b) CWT. (c) STFT.

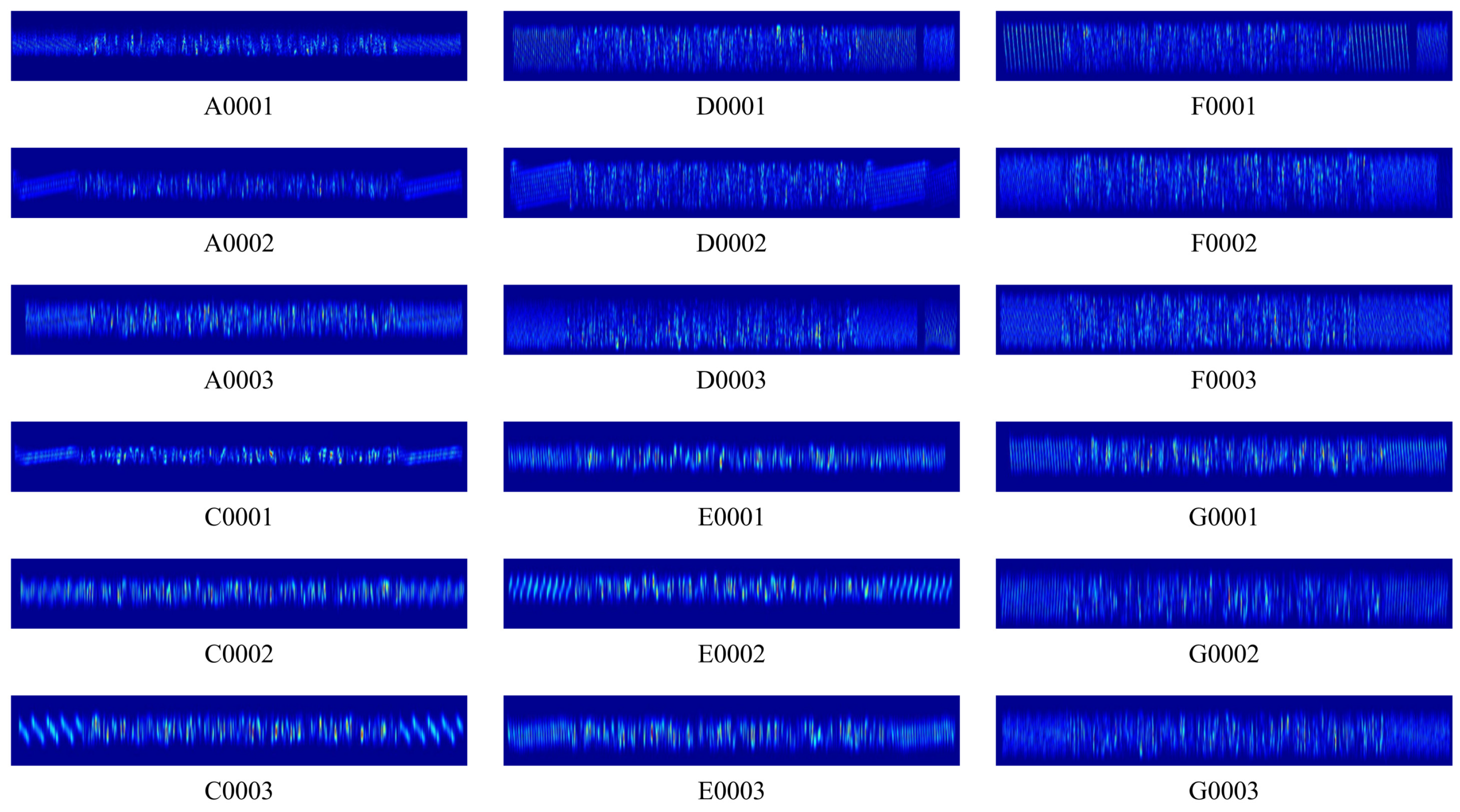

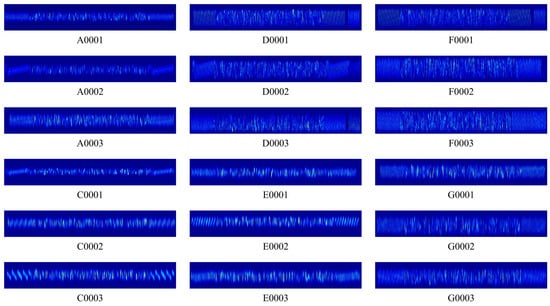

3.3. Self-Built Dataset

The raw signals from the DroneRFb-DIR dataset were processed using the preprocessing algorithm proposed in this study, resulting in 10,300 time–frequency plots of flight control signals across six UAV categories. These plots formed an image dataset for individual UAV recognition. All images were manually annotated using semi-automated tools and randomly divided into training, testing, and validation sets in a 7:2:1 ratio. Each UAV type includes three distinct individuals. The models DJI Mavic 3 Pro, DJI Mini 2 SE, DJI Mini 4 Pro, DJI Mini 3, DJI Air 3, and DJI Air 2S are labeled A, C, D, E, F, and G, respectively. For instance, the three DJI Mavic 3 Pro individuals are numbered A0001, A0002, and A0003. In total, the dataset contains 18 unique labels, as summarized in Figure 10.

Figure 10.

Example of the self-built dataset.

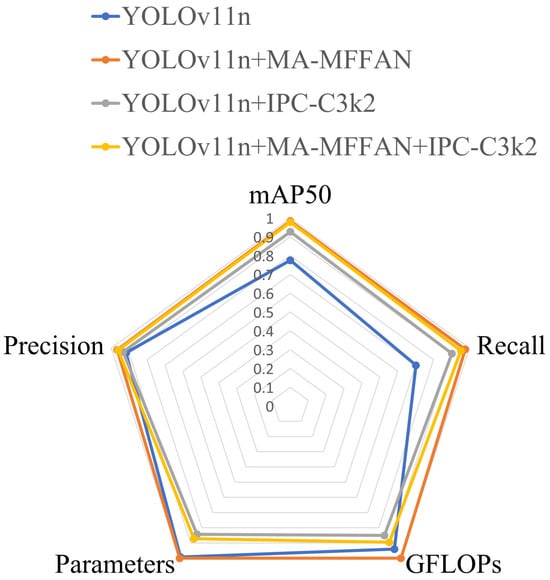

3.4. Improved Model Comparison Experimental Analysis

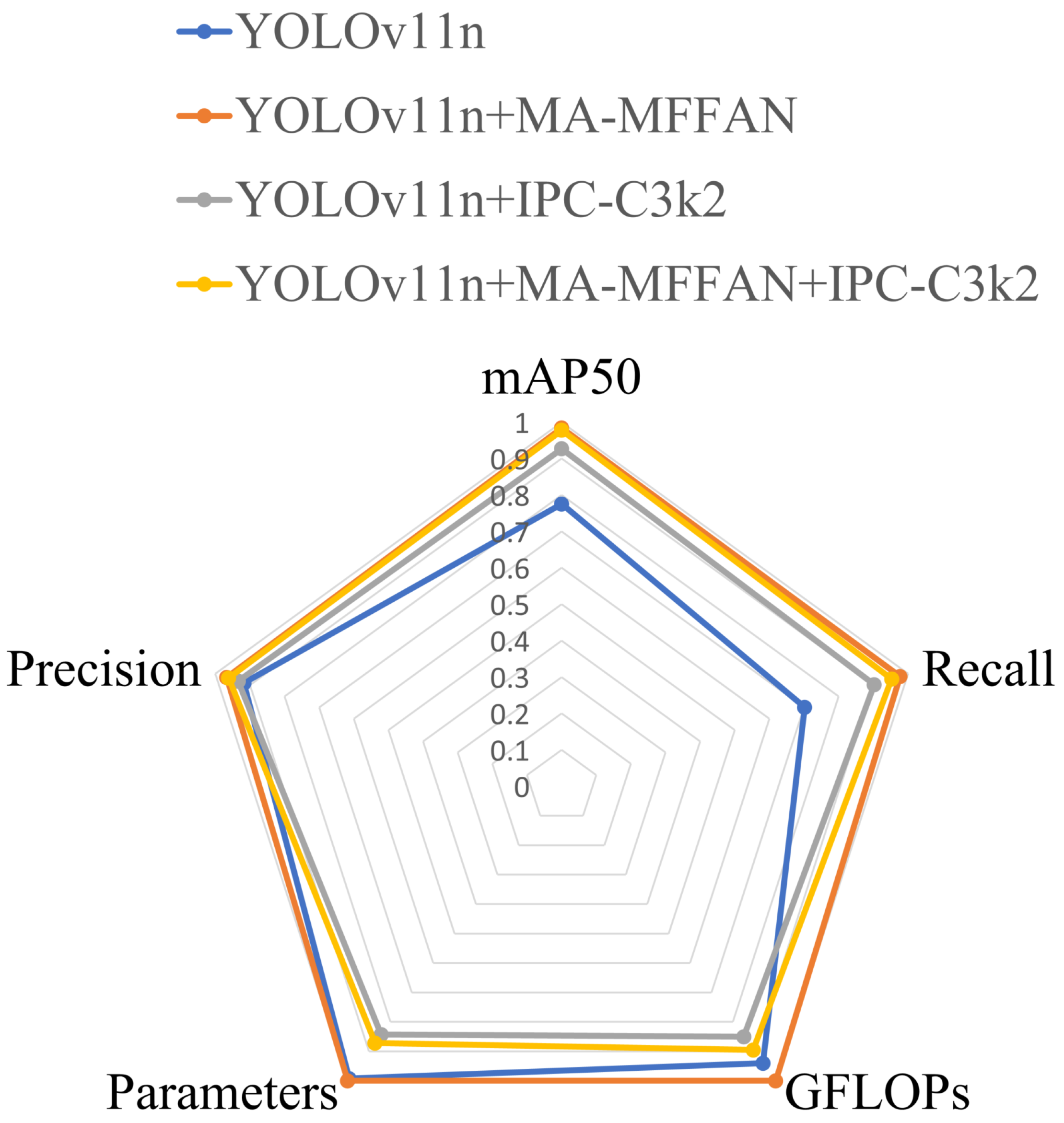

Table 3 presents the results of ablation experiments in which different enhancement modules were integrated into the YOLOv11n architecture. The results indicate that the baseline model performs poorly on key metrics, such as mAP50, precision, and parameter efficiency, and therefore fails to meet practical application requirements. After incorporating the proposed modules, both the standalone integration of MA-MFFAN and IPC-C3k2 lead to significant performance improvements. Specifically, replacing the baseline neck network with the MA-MFFAN module substantially improves mAP50 and precision; notably, this improvement is accompanied by increased parameter count and computational complexity. In contrast, partially replacing the C3k2 modules with IPC-C3k2 yields smaller gains in mAP50 and precision than full replacement, but results in a notable reduction in computational cost. To achieve a better balance between performance and efficiency, both modules were integrated into the baseline model to construct the DIR-YOLOv11 architecture. This model not only achieves higher detection accuracy but also demonstrates excellent computational efficiency: the GFLOPs are reduced to 95.23% of those of the baseline model, and the number of parameters is reduced to 87.84%, thereby significantly lowering computational resource requirements. To visually compare the overall performance of each model across multiple evaluation metrics, all indicators were normalized and are presented in a radar chart shown in Figure 11.

Table 3.

Ablation experiments.

Figure 11.

Radar chart for ablation experiments.

In our study, the effectiveness of data preprocessing directly impacts the performance of subsequent individual UAV recognition. To evaluate different time–frequency analysis methods, we conducted comparative experiments on the DIR-YOLOv11 model using STFT, CWT, and the proposed FFS-SPWVD algorithm. All experiments were performed from scratch without using pre-trained weights, and the results are presented in Table 4. The results show that, compared to STFT and CWT, FFS-SPWVD achieved mAP50 improvements of 21.48% and 15.33%, respectively. Time–frequency analysis algorithms with higher resolution more effectively capture the fingerprint information of RF signals, resulting in superior individual recognition performance.

Table 4.

JTFA algorithm performance comparison.

To further assess the superiority of the DIR-YOLOv11 algorithm, we compared it with the classic two-stage detection algorithm Faster R-CNN, various YOLO versions, and the Transformer-based RT-DETR algorithm. The YOLO variants included YOLOv11s, YOLOv8n, YOLOv9t [44], YOLOv10n, YOLOv12 [45], YOLOv13 [46], and the baseline YOLOv11n model. Experimental results for all eight algorithms, including the proposed DIR-YOLOv11, are summarized in Table 5. To prevent overfitting, no pre-trained weights were used for any model in the experiments. The five evaluation metrics presented in Table 5 comprehensively reflect differences among the models in terms of recognition accuracy and computational complexity.

Table 5.

Performance comparison of different models.

The traditional two-stage detection algorithm Faster R-CNN shows significant performance gaps in mAP50, recall, and precision compared to other algorithms, indicating suboptimal performance. Its computational resource requirements are also far higher than those of YOLO-series models, limiting its applicability in individual UAV recognition tasks that demand high-precision identification. Compared to typical YOLO models such as YOLOv11s, YOLOv8n, YOLOv9t, YOLOv10n, and YOLOv11n, the proposed DIR-YOLOv11 model reduces computational load by 4.7% relative to the baseline model, with approximately 2.2 million parameters. Despite this efficiency, it achieves an overall mAP50 of 0.9782, outperforming YOLOv11s (+0.1889), YOLOv8n (+0.2105), YOLOv9t (+0.2305), YOLOv10n (+0.2773), YOLOv11n (+0.2127), and YOLOv12 (+0.2042). When compared with the state-of-the-art YOLOv13, DIR-YOLOv11 surpasses it across all evaluation metrics. Additionally, experiments using our proprietary dataset with the Transformer-based RT-DETR model show that, due to its different architecture, RT-DETR requires substantially more parameters than DIR-YOLOv11. Compared with RT-DETR, our model achieves an mAP50 only 0.0079 lower, recall 0.0228 lower, and precision 0.0026 lower, while requiring just 6% of RT-DETR’s computational effort. Furthermore, DIR-YOLOv11 attains significant precision improvements over traditional correlation detection methods [18]. Finally, to evaluate the model’s classification performance, although object detection networks do not typically report Top-1 accuracy directly, this study selects the prediction category with the highest confidence score in each test image as the classification output and computes the corresponding Top-1 accuracy. Experimental results show that, compared with the baseline model, the improved DIR-YOLOv11 model achieves a 13.7% increase in Top-1 accuracy. This result further confirms the effectiveness of the proposed method in enhancing feature discriminability and classification reliability, indicating that the improvements not only optimize detection performance but also significantly strengthen the model’s capability for semantic recognition. These results demonstrate that DIR-YOLOv11 enhances recognition accuracy while reducing model complexity, making it highly suitable for practical individual UAV recognition applications.

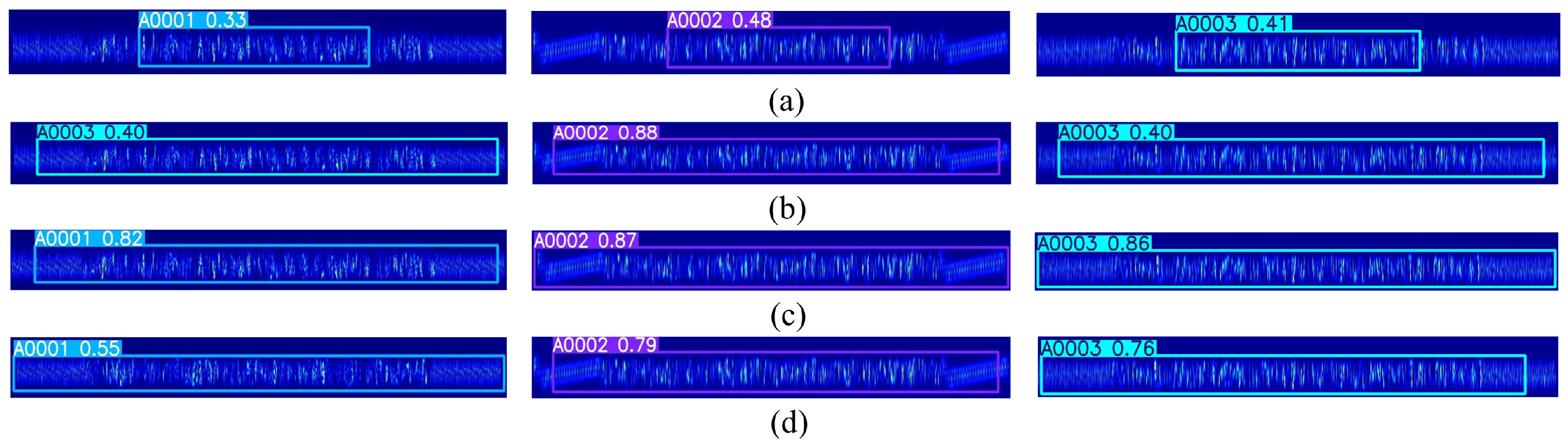

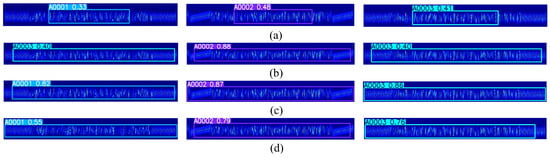

3.5. Visual Recognition Results

To visually illustrate the individual recognition performance of the proposed algorithms, Figure 12 presents partial time–frequency signal recognition results for UAVs using YOLOv11n, YOLOv13, RT-DETR, and DIR-YOLOv11. The images are derived from the preprocessing subsystem output, showing DJI Mavic 3 Pro Individuals 1, 2, and 3 from left to right. Figure 12a shows the recognition results of YOLOv11n on the test image, Figure 12b shows YOLOv13’s results, Figure 12c shows RT-DETR’s results, and Figure 12d shows DIR-YOLOv11’s results. It is evident that the baseline model YOLOv11n focuses only on partial regions when processing complex flight control signal frames, omitting the preamble and postamble codes. This leads to incomplete feature extraction, as reflected in the selected regions and confidence scores. Compared to the baseline, YOLOv13 covers the entire flight control signal frame but still struggles to distinguish individual differences, mistakenly identifying Individual A0001 as A0003. The state-of-the-art RT-DETR model, leveraging its large parameter count and computational capacity, achieves the best performance in both recognition accuracy and individual discrimination. The proposed DIR-YOLOv11 model achieves maximal coverage of flight control signal frames, with confidence scores for each individual increasing by 0.22, 0.31, and 0.35 compared to the baseline. These results demonstrate that DIR-YOLOv11 effectively performs both signal detection and individual recognition tasks, outperforming other models.

Figure 12.

Individual recognition experiment results. (a) YOLOv11 recognition results. (b) YOLOv13 recognition results. (c) RT-DETR recognition results. (d) DIR-YOLOv11 recognition results.

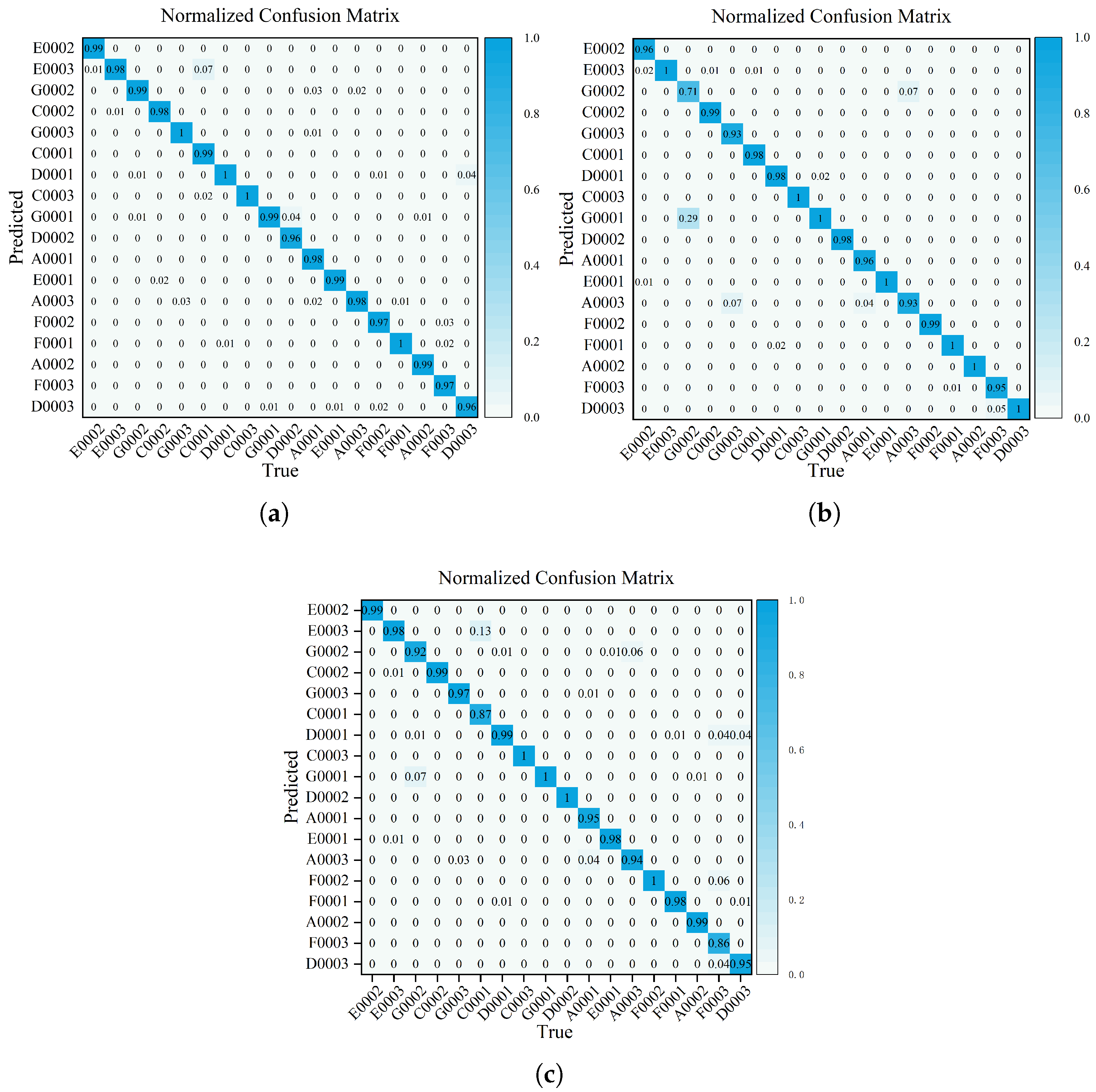

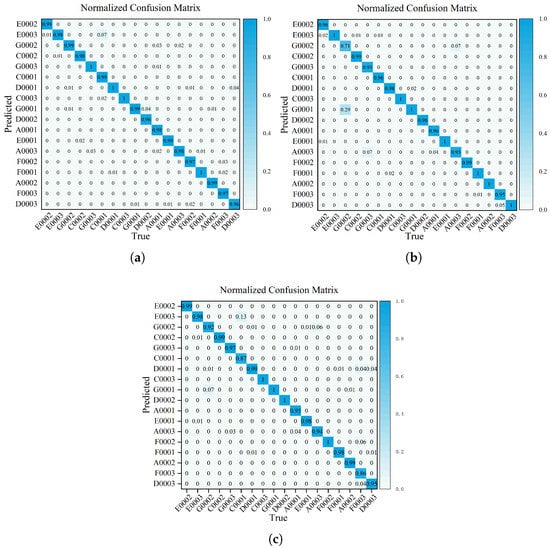

Figure 13 presents the confusion matrices for the three models used in individual UAV recognition when evaluated on the same dataset. Compared to the other two advanced models, this model demonstrates superior performance in distinguishing most UAV types and achieves results closest to those of the state-of-the-art RT-DETR model. However, the confusion matrix indicates that the model still makes misclassifications in certain individual cases. Detailed analysis shows that the confusion between C0001 (DJI Mini 2 SE) and E0003 (DJI Mini 3) mainly arises from their similar model identifiers, identical communication protocols, and narrow flight control signal bandwidths. These factors lead to highly similar time–frequency domain contour features, making it difficult for the model to distinguish between these closely related targets. In addition, slight confusion was observed between the DJI Air 3 models F0003 and F0002. Further examination of their flight control signal frame structures revealed a high degree of similarity in their preamble and postamble codes, which is the primary reason the model struggled to effectively differentiate between them.

Figure 13.

Visual experiment confusion matrices. (a) RT-DETR. (b) YOLOv13. (c) DIR-YOLOv11.

3.6. Comparison with Other Methods

We compared the proposed method with existing UAV RF identification approaches in terms of time–frequency resolution, frame extraction strategies, feature fusion mechanisms, target tasks, and accuracy. The comparison results are summarized in Table 6.

Table 6.

Summary of comparison.

Existing methods, such as RF-YOLO and YOLOv5-7.0, mainly focus on drone model recognition, achieving accuracies between 92.13% and 99.29%. In contrast, this study enables joint identification of both model and individual within a single framework. This is achieved by improving the resolution of the time–frequency map and optimizing the neck network and feature extraction modules. While maintaining high recognition accuracy (96.8%), the approach extends identification to the finer granularity of individual drones, offering a more comprehensive solution for drone identity authentication and control.

4. Discussion

This study proposes a lightweight recognition method for individual UAV identification. By integrating traditional signal preprocessing techniques with a lightweight model suitable for practical deployment, the approach demonstrates excellent performance in recognition tasks. Experimental results show that, compared to the baseline YOLOv11n model, the improved DIR-YOLOv11 achieves significant gains on our self-built dataset: mean average precision at 50% (mAP50) increases by 21.27%, classification accuracy improves by 4.41%, model parameters are reduced by 12.1%, and computational cost (GFLOPs) decreases by 4.7%. Compared with other advanced algorithms, DIR-YOLOv11 also demonstrates superior overall performance. The core design principle of this study is to use high-resolution time–frequency representations to preserve detailed physical-layer information in RF signals. At the same time, multi-scale fingerprint features are dynamically fused using a data-driven weighting mechanism. By combining the interpretability of signal processing with the adaptability of deep learning, this approach creates a direct link between physical signal characterization and feature learning. As a result, subtle and time-varying discriminative features can be captured more effectively. The key idea—high-fidelity physical representation combined with adaptive feature weighting—is broadly applicable to recognition and diagnostic tasks that rely on weak or time-varying physical characteristics. Typical examples include wireless device authentication, communication emitter fingerprinting, and mechanical vibration fault diagnosis, where stable identifiers must be extracted from non-stationary data. The proposed methodology is suitable for various real-world surveillance scenarios. For example, in airport airspace management, it can distinguish authorized UAVs from suspicious aircraft. During large-scale events, it enables rapid identification and counting of on-site UAVs. In border patrol and traffic monitoring, it assists in detecting low-altitude UAV activity.

In practical deployment, the system should choose between offline and online processing modes based on the application scenario. For real-time monitoring tasks, millisecond-level inference latency requires edge devices with high computational and energy efficiency. Therefore, software-defined radio (SDR) is typically used for signal acquisition, and lightweight models are deployed at the edge to balance recognition accuracy and computational cost. In environments with limited communication or strong interference, offline processing can be used as a complementary approach. In addition, the integration of SDR and edge computing modules must be carefully optimized to ensure efficient data flow from signal sampling and preprocessing to inference, thereby preventing data throughput from becoming a bottleneck in real-time system performance.

Despite its advantages, the proposed method still has several limitations in practical applications. First, under low signal-to-noise ratio conditions, similar aircraft models may exhibit highly similar flight control signal textures, which can cause recognition confusion and reduce robustness in complex electromagnetic environments. Second, the current coarse-grained frame segmentation strategy, which uses fixed time durations, cannot always preserve the structural integrity of signal frames. When the SNR fluctuates or the signal is non-stationary, extraction errors may occur, leading to missed detections. In addition, the algorithm depends on prior knowledge of complete signal structures and detailed time–frequency analysis. As a result, it is sensitive to frame synchronization and time–frequency resolution during preprocessing. This sensitivity may limit scalability and real-time performance in continuous monitoring and large-scale parallel UAV identification. Finally, the method follows a closed-set assumption, which makes it difficult to recognize UAV signals that are not included in the database. Therefore, the proposed high-precision individual UAV recognition method is currently applicable only to scenarios with sufficient annotated data. Under stable electromagnetic conditions and typical flight states, such as hovering or normal cruising, the proposed method shows strong generalization performance. Nevertheless, identification accuracy may decrease significantly if the target UAV operates in a heavily jammed environment or if its communication protocol is substantially modified.

Future research will focus on several key directions. First, we will study feature enhancement and adaptive signal frame extraction methods under low signal-to-noise ratio conditions to improve robustness in complex electromagnetic environments. Second, we will explore lightweight parallel processing architectures to enhance system scalability for large-scale, real-time monitoring. Third, we will address the limitations of closed-set recognition by introducing open-set recognition strategies to improve the detection and classification of unknown UAV types. Fourth, to overcome the limited number of individual samples in current datasets, we plan to build larger and more comprehensive datasets. We will also study recognition methods for small-sample scenarios and cross-dataset generalization. Fifth, in response to increasingly complex UAV operating environments, we will investigate joint recognition and authorization methods under adversarial or strong interference conditions to support practical security applications.

5. Conclusions

Individual identification based on UAV radio-frequency (RF) signals faces challenges such as co-channel interference, large data volumes, and limited accuracy of classical algorithms. To address these issues, this paper proposes a systematic solution. First, a frame-based smoothing pseudo-Wigner–Ville distribution (FFS-SPWVD) method is employed to generate high-resolution time–frequency maps of UAV flight control signals, and an individual UAV identification image dataset is constructed using the DroneRFb-DIR dataset. Second, an MA-MFFAN module is designed to fuse multi-scale features, mitigating information loss caused by downsampling. Finally, the PSFSC module is introduced to focus on target regions while reducing computational complexity, forming the final model, DIR-YOLOv11. Experimental results show that the proposed method can independently extract flight control signal frames while preserving high-resolution time–frequency characteristics. In individual recognition tasks, it achieves an accuracy of 0.9617, an mAP50 of 0.9782, and a recall of 0.9529. These results indicate that the model precisely captures key signal features and maintains a low misrecognition rate, even in complex signal environments. Overall analysis shows that the proposed method outperforms other advanced algorithms by achieving a better balance between recognition accuracy and resource consumption.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, M.Q. and J.Y.; methodology, M.Q. and J.Y.; validation, M.Q., J.Y. and L.H.; formal analysis, J.Y., Y.Z. and S.L.; writing—original draft preparation, M.Q. and J.Y.; writing—review and editing, M.Q. and J.Y.; visualization, J.Y., J.J. and L.H.; supervision, M.Q.; project administration, M.Q.; funding acquisition, M.Q. and J.Y. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported in part by National Science Foundation grant 62261051 and Mianyang Science Foundation grant 2025ZYDF095.

Data Availability Statement

This study utilizes the DroneRFb-DIR dataset of radio-frequency signals for non-cooperative drone individual identification, released by Zhejiang University in China, as experimental data, which can be accessed at https://www.scidb.cn/detail?dataSetId=84cf9101e739402784b1396783881202 (accessed on 29 December 2025).

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| RT-DETR | Real-Time Detection Transformer |

| FFS-SPWVD | Frame-by-Frame Search-Based Smoothing Pseudo-Wigner–Ville Distribution |

| JTFA | Joint Time–Frequency Analysis |

| MAFPN | Multi-Branch Assisted Feature Pyramid Network |

| MFM | Modulation Fusion Module |

| PConv | Partial Convolution |

| SFS-Conv | Space–Frequency Selective Convolutions |

| TFS | Time–Frequency dynamic Spectrum |

References

- Wang, G.; Zhan, Y.; Zou, Y. Uav recognition algorithm for ground military targets based on improved Yolov5n. Comput. Meas. Control 2024, 32, 189–197. [Google Scholar]

- Rao, J.; Xiang, C.; Xi, J.; Chen, J.; Lei, J.; Giernacki, W.; Liu, M. Path planning for dual UAVs cooperative suspension transport based on artificial potential field-A* algorithm. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2023, 277, 110797. [Google Scholar]

- George Jain, A. In/visibilities. Eur. J. Int. Law. 2024, 35, 971–978. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bhadra, S.; Sagan, V.; Sarkar, S.; Braud, M.; Mockler, T.C.; Eveland, A.L. PROSAIL-Net: A transfer learning-based dual stream neural network to estimate leaf chlorophyll and leaf angle of crops from UAV hyperspectral images. ISPRS J. Photogramm. Remote Sens. 2024, 210, 1–24. [Google Scholar]

- Duo, C.; Li, Y.; Gong, W.; Li, B.; Qi, G.; Zhang, J. UAV-aided distribution line inspection using double-layer offloading mechanism. IET Gener. Transm. Distrib. 2024, 18, 2353–2372. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, M.; Gu, G.; Qian, W.; Ren, K.; Maldague, X.; Chen, Q. Unmanned aerial vehicle video-based target tracking algorithm using sparse representation. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 6, 9689–9706. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alzahrani, M.Y. Enhancing drone security through multi-sensor anomaly detection and machine learning. SN Comput. Sci. 2024, 5, 651. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warnakulasooriya, K.; Segev, A. Attacks, Detection, and Prevention on Commercial Drones: A Review. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Image Processing and Robotics (ICIPRoB), Colombo, Sri Lanka, 9–10 March 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mekdad, Y.; Aris, A.; Babun, L.; Fergougui, A.; Conti, M.; Lazzeretti, R.; Uluagac, A. A survey on security and privacy issues of uavs. arXiv 2021, arXiv:2109.14442. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Haugstvedt, H. Still Aiming at the Harder Targets. Perspect. Terror. 2024, 18, 132–143. [Google Scholar]

- Yasmine, G.; Maha, G.; Hicham, M. Survey on current anti-drone systems: Process, technologies, and algorithms. Int. J. Syst. Syst. Eng. 2022, 12, 235–270. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jurn, Y.N.; Mahmood, S.A.; Aldhaibani, J.A. Anti-drone system based different technologies: Architecture, threats and challenges. In Proceedings of the 2021 11th IEEE International Conference on Control System, Computing and Engineering (ICCSCE), Penang, Malaysia, 27–28 August 2021; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021; pp. 114–119. [Google Scholar]

- Park, S.; Kim, H.T.; Lee, S.; Joo, H.; Kim, H. Survey on anti-drone systems: Components, designs, and challenges. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 42635–42659. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, Y.; He, Z. Radio Frequency Signal-Based Drone Classification with Frequency Domain Gramian Angular Field and Convolutional Neural Network. Drones 2024, 8, 511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nie, W.; Han, Z.C.; Zhou, M.; Xie, L.B.; Jiang, Q. UAV detection and identification based on WiFi signal and RF fingerprint. IEEE Sens. J. 2021, 21, 13540–13550. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nguyen, P.; Truong, H.; Ravindranathan, M.; Nguyen, A.; Han, R.; Vu, T. Matthan: Drone presence detection by identifying physical signatures in the drone’s RF communication. In Proceedings of the 15th Annual International Conference on Mobile Systems, Applications, and Services, Niagara Falls, NY, USA, 19–23 June 2017; pp. 211–224. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, C.; Chen, B.; Liu, Y.; He, F.; Song, H. RF fingerprint measurement for detecting multiple amateur drones based on STFT and feature reduction. In Proceedings of the 2020 Integrated Communications Navigation and Surveillance Conference (ICNS), Herndon, VA, USA, 8–10 September 2020; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2020; p. 4G1-1. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, J.; Yu, N.; Zhou, C.; Shi, Z.; Chen, J. DroneRFb-DIR: An RF signal dataset for non-cooperative drone individual identification. J. Electron. Inf. Technol. 2025, 47, 573–581. [Google Scholar]

- Huynh-The, T.; Pham, Q.V.; Nguyen, T.V.; Da Costa, D.B.; Kim, D.S. RF-UAVNet: High-performance convolutional network for RF-based drone surveillance systems. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 49696–49707. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medaiyese, O.O.; Ezuma, M.; Lauf, A.P.; Guvenc, I. Wavelet transform analytics for RF-based UAV detection and identification system using machine learning. Pervasive Mob. Comput. 2022, 82, 101569. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kumbasar, N.; Kılıç, R.; Oral, E.A.; Ozbek, I.Y. Comparison of spectrogram, persistence spectrum and percentile spectrum based image representation performances in drone detection and classification using novel HMFFNet: Hybrid Model with Feature Fusion Network. Expert Syst. Appl. 2022, 206, 117654. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, S.; Rajendran, S.; Pollin, S.; Scheers, B. Combined RF-based drone detection and classification. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Commun. Netw. 2021, 8, 111–120. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Delleji, T.; Slimeni, F. RF-YOLO: A modified YOLO model for UAV detection and classification using RF spectrogram images. Telecommun. Syst. 2025, 88, 33. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Y.; Lv, W.; Xu, S.; Wei, J.; Wang, G.; Dang, Q.; Liu, Y.; Chen, J. DETRs beat yolos on real-time object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 16965–16974. [Google Scholar]

- Lv, W.; Zhao, Y.; Chang, Q.; Huang, K.; Wang, G.; Liu, Y. Rt-detrv2: Improved baseline with bag-of-freebies for real-time detection transformer. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2407.17140. [Google Scholar]

- Pan, Z.; Li, C.; Zhou, X.; Deng, F.; Li, T. Combined SPWVD and WVD for high-resolution time-frequency analysis of fault traveling waves. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE 8th International Electrical and Energy Conference (CIEEC), Changsha, China, 16–18 May 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 3575–3580. [Google Scholar]

- Zhou, C.; Gu, Y.; Shi, Z.; Haardt, M. Structured Nyquist correlation reconstruction for DOA estimation with sparse arrays. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2023, 71, 1849–1862. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, H.; Zhou, C.; Shi, Z.; Gu, Y.; Zhang, Y.D. Coarray tensor direction-of-arrival estimation. IEEE Trans. Signal Process. 2023, 71, 1128–1142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fan, Y.; Tan, Z.; Yang, G.; Wang, R. Doppler Frequency Shift and SNR Estimation using Improved STFT-based method for mmWave Wind Profiler Radar. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE International Students’ Conference on Electrical, Electronics and Computer Science (SCEECS), Bhopal, India, 24–25 February 2024; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2024; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Huo, S.; Nie, J.; Tang, X.; Wang, F. Minimum energy block technique against pulsed and narrowband mixed interferers for single antenna GNSS receivers. IEEE Commun. Lett. 2015, 19, 1933–1936. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Wu, Z.; Chen, X.; Shi, L. Defect Location Analysis of CFRP plates Based on Morphological Filtering Technique. IEEE Access 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qin, M.W.; Tang, R.; Zhou, Y.H.; Lan, C.J.; Fu, W.H.; Wang, H.; Hou, B.L.; Abidin, Z.B.Z.; Ping, J.S.; Yang, W.J.; et al. Noise Reduction Method for Radio Astronomy Single Station Observation Based on Wavelet Transform and Mathematical Morphology. Res. Astron. Astrophys. 2025, 25, 075014. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Truong, C.; Oudre, L.; Vayatis, N. Selective review of offline change point detection methods. Signal Process. 2020, 167, 107299. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Luo, C.; Tang, H.; Li, S.; Wan, G.; Chen, W.; Guan, J. YOLOv11s-CD: An Improved YOLOv11s Method for Catenary Dropper Fault Detection. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2025, 74, 5043410. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Z.; Guan, Q.; Zhao, K.; Yang, J.; Xu, X.; Long, H.; Tang, Y. Multi-branch auxiliary fusion yolo with re-parameterization heterogeneous convolutional for accurate object detection. In Proceedings of the Chinese Conference on Pattern Recognition and Computer Vision (PRCV), Urumqi, China, 18–20 October 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 492–505. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, S.; Li, H. Depth information assisted collaborative mutual promotion network for single image dehazing. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 2846–2855. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, J.; Kao, S.h.; He, H.; Zhuo, W.; Wen, S.; Lee, C.H.; Chan, S.H.G. Run, don’t walk: Chasing higher FLOPS for faster neural networks. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 17–24 June 2023; pp. 12021–12031. [Google Scholar]

- Li, K.; Wang, D.; Hu, Z.; Zhu, W.; Li, S.; Wang, Q. Unleashing channel potential: Space-frequency selection convolution for SAR object detection. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 17323–17332. [Google Scholar]

- Zheng, Y.; Ai, X.; Yang, Y.; Zhao, F.; Xiao, S. Detection method of forward-scatter signal based on Rényi entropy. J. Syst. Eng. Electron. 2023, 35, 865–873. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chattopadhyay, A.; Selvan, S.E.; Amato, U. A derivative-free Riemannian Powell’s method, minimizing Hartley-entropy-based ICA contrast. IEEE Trans. Neural Netw. Learn. Syst. 2015, 27, 1983–1990. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suguro, T. Shannon’s inequality for the Rényi entropy and an application to the uncertainty principle. J. Funct. Anal. 2022, 283, 109566. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Baraniuk, R.G.; Flandrin, P.; Janssen, A.J.; Michel, O.J. Measuring time-frequency information content using the Rényi entropies. IEEE Trans. Inf. Theory 2002, 47, 1391–1409. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, N.; Mao, S.; Zhou, C.; Sun, G.; Shi, Z.; Chen, J. DroneRFa: A large-scale dataset of drone radio frequency signals for detecting low-altitude drones. J. Electron. Inf. Technol. 2023, 45, 1–9. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, C.Y.; Yeh, I.H.; Mark Liao, H.Y. Yolov9: Learning what you want to learn using programmable gradient information. In European Conference on Computer Vision; Springer: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 1–21. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Ye, Q.; Doermann, D. Yolov12: Attention-centric real-time object detectors. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.12524. [Google Scholar]

- Lei, M.; Li, S.; Wu, Y.; Hu, H.; Zhou, Y.; Zheng, X.; Ding, G.; Du, S.; Wu, Z.; Gao, Y. YOLOv13: Real-Time Object Detection with Hypergraph-Enhanced Adaptive Visual Perception. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2506.17733. [Google Scholar]

- Li, M.; Hao, D.; Wang, J.; Wang, S.; Zhong, Z.; Zhao, Z. Intelligent identification and classification of small UAV remote control signals based on improved yolov5-7.0. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 41688–41703. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhu, G.; Briso, C.; Liu, Y.; Lin, Z.; Mao, K.; Li, S.; He, Y.; Zhu, Q. An Intelligent Passive System for UAV Detection and Identification in Complex Electromagnetic Environments via Deep Learning. Drones 2025, 9, 702. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basak, S.; Becquaert, M. An Enhanced End-to-End Framework for Drone RF Signal Classification. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Mediterranean Conference on Communications and Networking (MeditCom), Nice, France, 7–10 July 2025; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2025; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.