Abstract

Phishing and spam emails continue to pose a serious cybersecurity threat, leading to financial loss, information leakage, and reputational damage. Traditional email filtering approaches struggle to keep pace with increasingly sophisticated attack strategies, particularly those involving malicious content and deceptive attachments. This study proposes a dual-layer deep learning architecture designed to enhance email security by improving the detection of phishing and spam messages. The first layer employs deep learning models, including LSTM- and transformer-based classifiers, to analyze email content and structural features across legitimate, phishing, and spam emails. The second layer focuses on spam emails containing attachments and applies advanced transformer models, such as GPT-2 and XLM-RoBERTa, to assess contextual and semantic patterns associated with malicious attachments. By integrating textual analysis with attachment-level inspection, the proposed architecture overcomes limitations of single-layer approaches that rely solely on email body content. Experimental evaluation using accuracy and F1-score demonstrates that the dual-layer framework achieves a minimum F1-score of 98.75 percent in spam–ham classification and attains an attachment detection accuracy of up to 99.46 percent. These results indicate that the proposed approach offers a reliable and scalable solution for enhancing real-world email security systems.

1. Introduction

With the widespread adoption of digital communication, email has become a primary target for cyberattacks. Phishing and spam emails pose serious threats to individuals and organizations, potentially leading to financial losses, data breaches, and reputational damage. These malicious emails frequently rely on social engineering techniques to deceive recipients into disclosing sensitive information or accessing harmful links. As attack strategies continue to evolve, traditional email filtering systems struggle to maintain effective protection, highlighting the need for more advanced detection mechanisms. Several studies have explored machine learning and deep learning approaches for phishing and spam detection. In particular, the authors in [1] introduced a dual-layer strategy aimed at improving classification accuracy while addressing class imbalance. Their approach employs two sequential classification stages, where the first layer focuses on identifying fraudulent emails and the second layer categorizes unsolicited messages. While effective, this approach primarily emphasizes email content analysis and does not explicitly examine attachment-level characteristics or complex spam scenarios involving embedded files. In parallel with these developments, recent advances in large language models (LLMs) have further influenced cybersecurity research, enabling improved semantic understanding in tasks such as phishing detection, spam filtering, malware analysis, and program inspection. At the same time, emerging studies have highlighted new security challenges associated with LLMs, including adversarial misuse, prompt manipulation, and backdoor vulnerabilities. This dual role of LLMs—as both powerful analytical tools and potential attack vectors—underscores the importance of controlled and task-aware integration of deep semantic models within security-critical systems. Consequently, architectures that selectively apply advanced language models, rather than relying on uniform and computationally intensive deployment, are increasingly viewed as a practical direction for real-world email security applications [2,3]. Motivated by these observations and the limitations of existing approaches, this study proposes an enhanced dual-layer deep learning framework that extends beyond content-based analysis by incorporating attachment-level inspection. Unlike [1], the proposed architecture is designed to separately process mixed email streams and spam emails containing attachments. The first layer analyzes the content and structural features of emails using deep learning models trained on a diverse dataset of legitimate, phishing, and spam messages. The second layer performs a focused analysis on spam emails with attachments, employing advanced deep learning models to capture contextual and semantic patterns associated with malicious files. This separation allows the framework to address class imbalance more effectively while improving detection accuracy for complex spam scenarios. By integrating insights from both textual content and attachment analysis, the proposed framework provides a more comprehensive understanding of email threats. Compared with single-layer models and prior dual-layer approaches, this design enhances robustness against sophisticated phishing attempts that rely on deceptive attachments or indirect malicious cues. The main contributions of this study can be summarized as follows:

- Identification and evaluation of effective feature representations for phishing and spam email detection.

- Comparative analysis of multiple machine learning and deep learning models within single-layer and dual-layer settings.

- Development and validation of a dual-layer framework capable of improving detection performance under imbalanced data conditions.

- Empirical evaluation of the proposed approach using standard performance metrics, including accuracy, precision, recall, and F1-score.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews related work and highlights existing limitations. Section 3 describes the dataset, preprocessing steps, feature extraction methods, and the proposed model architecture. Section 4 presents the experimental results and comparative performance analysis. Finally, Section 5 concludes the paper and outlines directions for future research.

2. Related Works

This study [4] analyzed 63 phishing emails generated using artificial intelligence models, specifically GPT-4o, to examine the effectiveness of widely used email services such as Gmail, Outlook, and Yahoo in filtering malicious communications. The findings revealed that Gmail and Outlook allowed a notable portion of AI-generated phishing emails to bypass their filtering mechanisms, highlighting structural weaknesses in current email security systems when confronted with linguistically sophisticated attacks. To address these limitations, the authors employed 60 stylometric features across four machine learning classifiers, namely Logistic Regression, Support Vector Machine, Random Forest, and XGBoost. Among these, XGBoost demonstrated superior performance, achieving an accuracy of 96 percent and an AUC of 99 percent, indicating the effectiveness of feature-driven approaches in controlled scenarios while also exposing their dependency on handcrafted representations. In a related direction, the authors in [5] extracted 56 features using natural language processing techniques, organizing them into five categories: headers, textual content, attachments, URLs, and protocols. The Spam Email Risk Classification (SERC) dataset combined private and public sources, enabling both binary classification and regression-based risk estimation. Although Random Forest achieved strong results, particularly an F1-score of 0.914, the study relied on static feature extraction, which may limit adaptability when facing evolving phishing strategies or complex email structures. Several studies have explored content-based and URL-focused phishing detection techniques. In [6], domain-based and lexical URL features were analyzed to identify phishing websites, while [7] introduced an optimized deep learning framework for spam and fake email screening using a multi-stage classifier. Similarly, PDGAN was proposed in [8] and recalled in [8], combining LSTM-based URL generation with CNN-based maliciousness assessment. These approaches demonstrate the potential of deep learning in capturing sequential patterns; however, their scope remains largely restricted to URLs or isolated content segments rather than comprehensive email analysis. Transformer-based and embedding-driven approaches have gained increasing attention. In [9], transformer-based embeddings combined with vector similarity search were used to detect phishing websites in real time, achieving high accuracy across multiple datasets. While such methods enhance semantic representation, they primarily focus on similarity matching and require external vector databases, which may introduce deployment complexity in large-scale email systems. Ensemble and hybrid learning strategies have also been extensively investigated. The HELPFED framework proposed in [10] combined ensemble learning with hybrid content and linguistic features to improve phishing detection. Other studies, such as [11,12], explored heuristic-based and LSTM-driven models, respectively, demonstrating improved detection capabilities but often requiring extensive feature engineering or sample augmentation. Additional works [13,14] integrated deep learning architectures, including graph convolutional networks and fully connected neural networks, to enhance detection accuracy, yet these methods typically address isolated aspects of phishing or spam detection rather than unified processing pipelines. Spam-specific detection has been addressed in [15,16], where hybrid deep learning models and ensemble classifiers were applied to publicly available datasets. Although these approaches achieved competitive results, their reliance on single-layer architectures limits their ability to differentiate between structurally simple and complex email instances. Comprehensive reviews in [8,17] further emphasized the need for adaptive feature selection and robust classifiers capable of handling diverse phishing patterns. Recent studies [18,19] expanded the scope to multilingual datasets, clustering-based spam categorization, and real-time phishing analysis, underscoring the growing complexity of email-based threats. Notably, ref. [20] introduced a fully automated ensemble system analyzing multiple email components, including headers, bodies, and attachments, demonstrating that multi-component analysis can outperform partial inspection methods. However, such systems often increase computational overhead by uniformly applying complex models to all email instances. Table 1 indicates that prior research consistently reports improved email classification and language analysis performance when deep learning approaches are applied.

Table 1.

Summary of prior research publications related to email phishing and spam detection.

As summarized in Table 1, existing studies on phishing and spam detection employ diverse algorithms and datasets, which predominantly rely on single-stage classification pipelines. Most approaches focus on either content-based or feature-driven analysis and are often evaluated on datasets with limited structural or linguistic variability. While acceptable performance is reported, these designs generally lack mechanisms to address heterogeneous email characteristics, such as attachment-bearing messages or pronounced class imbalance. This landscape underscores a methodological gap and motivates the adoption of multi-stage architectures that separate coarse-grained filtering from deeper semantic and structural analysis, thereby providing a more flexible foundation for complex email security scenarios.

3. Dataset Structuring and Proposed Model

3.1. Dataset

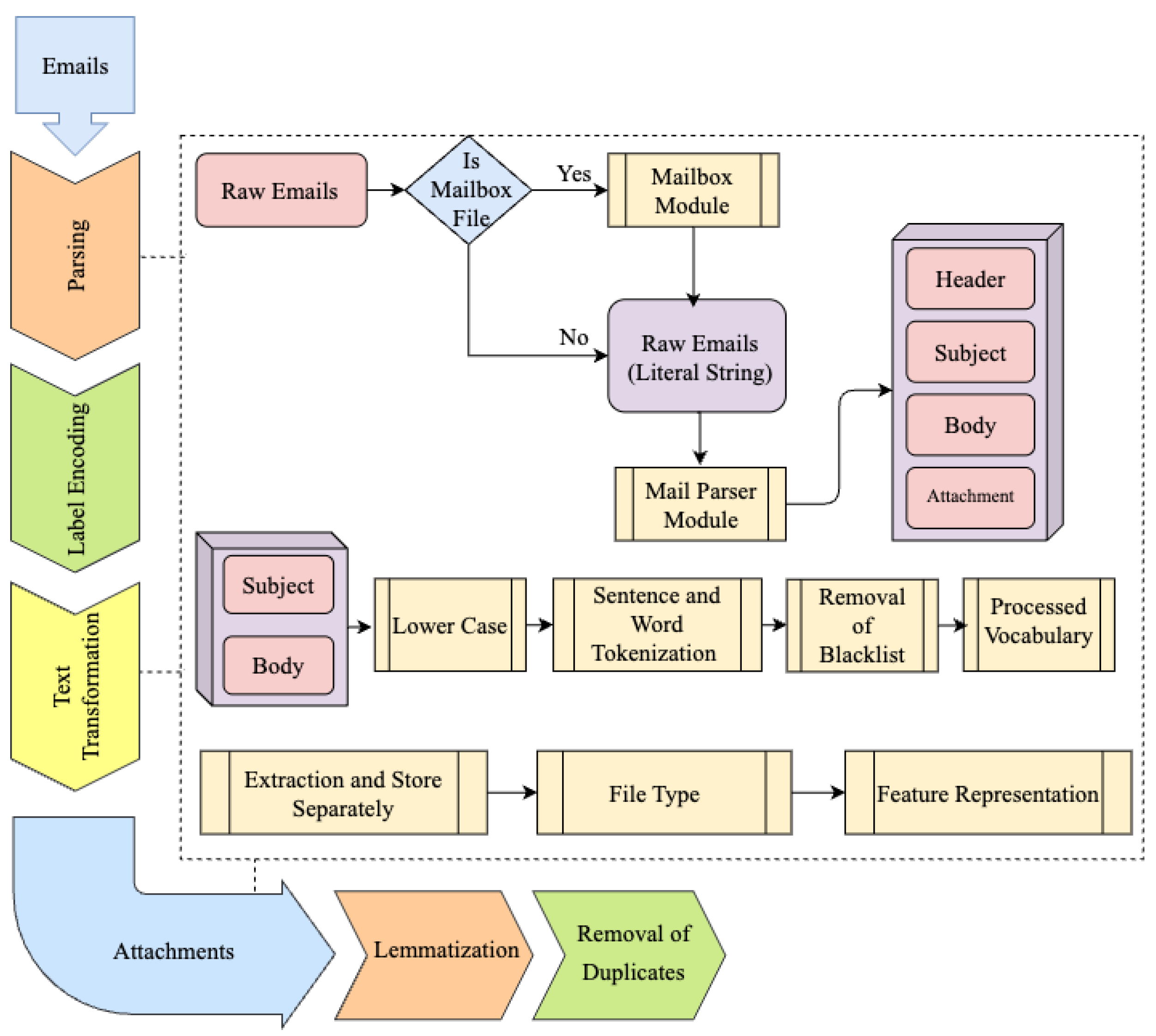

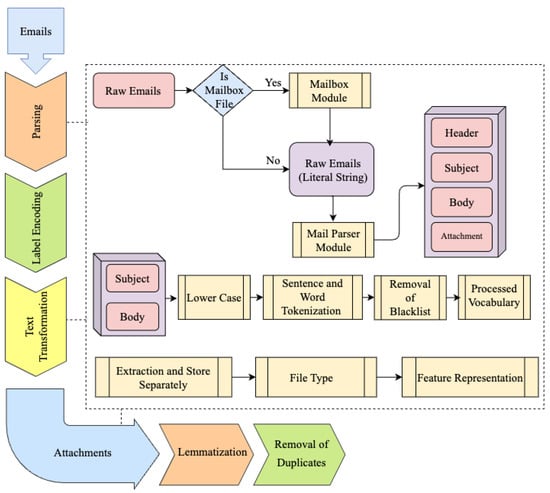

This study integrates four hybrid datasets composed of real-world phishing, spam, and legitimate emails, including messages with and without attachments. The data were collected from multiple sources to enhance representativeness and realism, including the first author’s corporate email server (last updated in 2024), Shantanu’s publicly available phishing corpus (2022), and the SpamAssassin dataset (2021). The consolidated dataset comprises 19,087 email instances. From a class distribution perspective, phishing emails constitute 15,949 samples (83.3 percent), forming the majority class, while spam emails account for 3138 samples (16.7 percent), representing the minority class. To further enhance dataset diversity and improve generalization capability, additional real-world spam emails written in Turkish and Arabic were incorporated. These multilingual samples were systematically distributed across the training and validation splits to enable the model to capture cross-lingual spam patterns, operate across different writing systems (Latin and Arabic), and remain effective in multilingual environments. This multilingual extension was essential for examining the generalization ability of the proposed dual-layer framework, as the second layer employs pretrained multilingual transformer models that learn semantic representations independent of specific languages. To minimize potential dataset bias and information leakage, a strict data curation process was applied prior to model training. Duplicate emails and near-duplicate messages, including repeated campaign templates and forwarded conversations, were removed using hash-based and content similarity checks. Labeling was performed at the email instance level and verified across sources to ensure consistency between public corpora and enterprise data. Training, validation, and test splits were constructed to prevent overlap of structurally similar messages across partitions. In addition, emails containing attachments were treated as independent analysis units in the second layer, reducing the risk of shared content influencing both training and evaluation stages. Figure 1 illustrates the preprocessing pipeline that converts raw email data into a structured format suitable for machine learning-based spam, ham, and phishing detection. The preprocessing workflow begins with parsing raw email files to distinguish between mailbox archives and individual messages. Emails extracted from mailbox files are processed accordingly, while standalone emails are handled directly. Each email is decomposed into its core components, including subject, body content, and attachments. Text preprocessing involves standardization through lowercasing, followed by sentence and word tokenization. Noise reduction is achieved by removing stop words, and lemmatization is applied to normalize lexical variations. These steps support consistent and informative feature extraction. For textual representation, feature vectors are generated using Term Frequency–Inverse Document Frequency (TF-IDF) or Bag-of-Words (BoW) techniques in the first layer, selected for their computational efficiency and suitability for large-scale pre-filtering tasks. Depending on the classification stage, semantic embeddings may also be employed to capture contextual information. Attachment handling is performed through a dedicated processing module. Attachments are extracted, stored separately, and categorized by file type. Feature extraction for attachments follows a similar preprocessing logic, focusing on metadata attributes, structural properties, and content-related indicators relevant to malicious behavior. Data cleaning procedures, including duplicate removal and missing value handling, are applied to enhance data integrity. Overall, this dataset structuring strategy ensures consistent treatment of textual content, attachments, and metadata, resulting in a well-prepared dataset that supports robust training and evaluation of the proposed dual-layer phishing and spam detection framework.

Figure 1.

Dataset refinement and preprocessing pipeline. Different colors indicate successive preprocessing stages applied to email content and attachments.

3.2. Extracting Key Attributes

The most important and useful characteristics must be identified and selected from a dataset to extract key features, which may be used to train a model and make predictions. After preprocessing the dataset, various attributes of the emails were used to extract features that including the sender and receiver email addresses, subjects, header, plain text, anchor tags, and attachments. This is an essential phase in the classification process because it improves the model’s accuracy and efficiency by reducing data complexity and removing unnecessary or duplicate features.

3.2.1. Bag-of-Words and N-Gram Features

The BoW system is a straightforward and efficient method for converting text into numerical information. This process involves converting a written document into a multi-dimensional vector, where each dimension corresponds to a unique word in the dictionary. Each dimension in the text corresponds to the corresponding phrase’s frequency. N-grams are continuous repetitions of N words inside a particular text. They document word usages and syntactic connections, providing greater contextual information compared to bag-of-words (BoW) models. Bag-of-words (BoW) and N-grams are crucial techniques for encoding text in machine learning. Although they are straightforward, they provide crucial information for several NLP tasks. To provide a more comprehensive depiction of features, bag-of-words (BoW) and N-grams are used. This approach can improve the model’s performance by capturing the frequencies of individual words as well as word combinations.

3.2.2. TF-IDF Vectorization

Term frequency–inverse document frequency (TF-IDF) is a commonly used method in natural language processing (NLP) to convert textual inputs into numerical representations that are suitable for machine learning algorithms. It calculates a word’s importance in a text by comparing its frequency across a group of papers. In this study, a document is defined as a distinct email. Word frequency is determined by measuring the frequency of a given word in a document. Although TF provides information on the relevance of a word within a document, it does not consider the term’s overall value throughout the collection of documents (corpus). The (IDF) allocates weights to terms according to their occurrence within the content of the corpus. In accordance with Equation (1), the term refers to the number of times the term t appears in document d, denotes the total number of terms in document d, D represents the total number of documents in the corpus, and indicates the number of documents containing the term t. In the process of feature extraction, the TFIDF vector is obtained from the content of

TF-IDF continues to be a significant tool for NLP professionals because it offers a fundamental approach for converting text input into a numerical representation that is suitable for machine learning algorithms.

3.3. Evaluation Metrics

Given the naturally imbalanced distribution of the email dataset, overall accuracy alone is insufficient to provide a reliable assessment of model performance. Accordingly, multiple evaluation metrics were applied to capture different aspects of classification behavior. Precision and recall were used to examine the model’s effectiveness in identifying minority-class emails while controlling false-positive and false-negative errors, which is particularly critical in phishing and attachment-based detection scenarios where misclassifications costs are asymmetric. The F1-score was adopted to balance precision and recall, offering a more informative measure under skewed class distributions. Beyond overall accuracy, the evaluation emphasizes these class-sensitive metrics to ensure that the reported performance is not dominated by the majority class. The reported results reflect consistent behavior across both spam/ham classification and attachment-specific detection tasks, indicating that the observed gains are attributable to balanced predictive performance rather than majority-class bias. Accuracy was reported as a general reference metric to facilitate comparison with prior studies. Together, these metrics provide a comprehensive evaluation framework that supports a robust assessment of the proposed model under class imbalance conditions. The formula for calculating classification accuracy is illustrated in Equation (2).

Precision measures the proportion of correctly identified spam emails among all emails classified as spam, reflecting the system’s ability to control false positives. Its formulation is given in Equation (3):

Recall quantifies the proportion of actual spam emails successfully detected by the system, indicating its effectiveness in intercepting unauthorized messages. Equation (4) defines this metric:

The F1-score represents the harmonic mean of precision and recall, providing a balanced performance measure under class imbalance conditions. The corresponding definition is shown in Equation (5):

3.4. Proposed Model

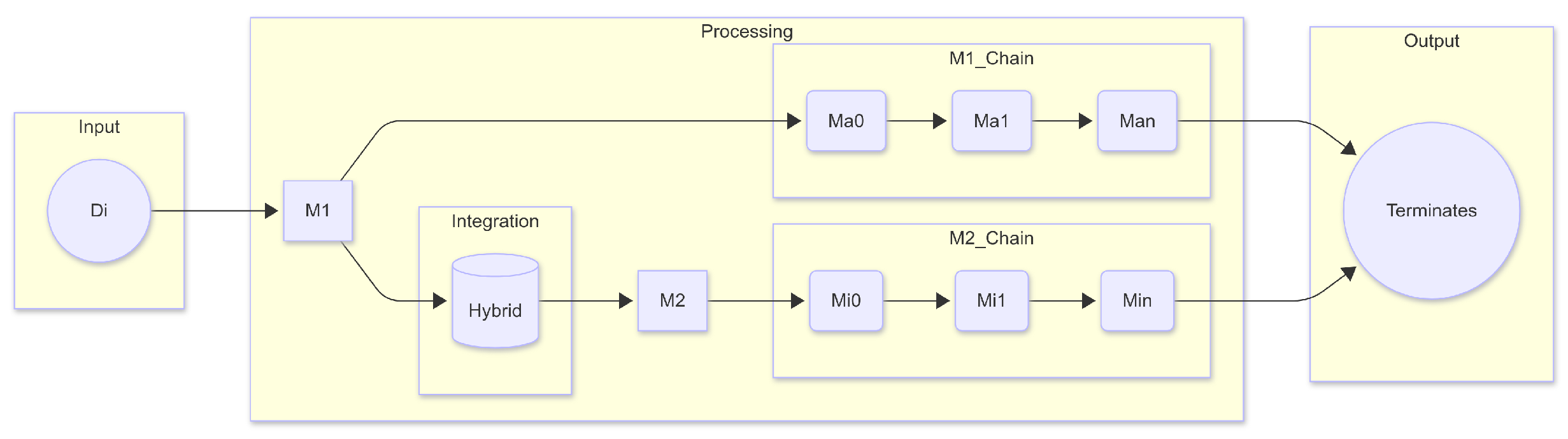

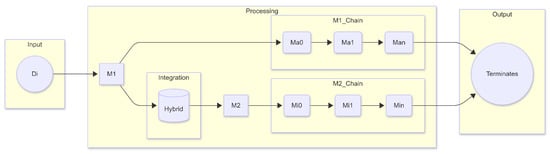

The proposed dual-layer framework consists of a two-stage classification mechanism. The first layer contains model 1 denoted as (M1) and the second layer contains model 2 denoted as (M2), designed to improve the detection precision for both majority (ham) and minority (spam with attachments) email categories. In this architecture, M1 performs an initial general classification over the full dataset, forwarding samples identified as complex or uncertain (primarily minority class instances) to the second stage using a hybrid integration module. M2, optimized through tailored feature sets and model tuning, provides an in-depth classification of these cases. This structure enables targeted handling of class imbalance while preserving the computational efficiency. Figure 2 illustrates the data flow and decision logic of the proposed dual-layer framework. This modular structure ensures each classifier is specialized to its data domain, enhancing both generalization and robustness. These models have shown higher effectiveness in comparison to traditional techniques. This is explained in greater detail in the “Results” section. The categorization process for freshly collected instances in the dual-layer approach is as follows: If the first layer classifies the datasets as belonging to the mixed category (i.e., unwanted messages with and/or without attachments), these samples will be sent to Layer 2, where they will be further separated into one of the minority classifications. In the event that the data samples are classified as belonging to one of the majority groups at Layer 1 (that is, Ham emails), then they will not be sent to Layer 2. The computed label will be acknowledged as the one that corresponds to the predicted class for that particular data instance. According to this technique, the algorithms that have been taught or trained in the past at Layer 1 and Layer 2 are denoted by the letters M1 and M2, respectively. The fresh instance Di must first be fed into Layer 1 of the model M1 before it can be classified with the other instances. M1 will classify Di into either a majority class (Ma0, Ma1,…, Man) or a hybrid class, depending on the qualities that are entered into it. In the event that Di belongs to a majority class, which is denoted by the term Ma1, the label that is expected to be assigned to Di will be Ma1; M1 determines this at the first layer. If Di is identified as a hybrid class by M1, it will be sent to the model M2 at the second layer, which will be categorized into any of the minority classes (Mi0, Mi1,…, Min). In the event that Di is assigned the number Mi1, this classification will be considered to be the final predicted classification for Di.

Figure 2.

Overview of the proposed dual-layer architecture.

3.5. Theoretical Justification of the Dual-Layer Architecture

The proposed dual-layer design is grounded in the principles of hierarchical classification and task-specific learning, providing a systematic solution to challenges related to class imbalance and feature heterogeneity in email spam detection. Conventional single-layer classifiers often struggle to maintain consistent performance across diverse data distributions, as they attempt to learn global decision boundaries that simultaneously encompass both majority (HAM) and minority (SPAM) classes within a unified framework. While such architectures may perform adequately on balanced datasets, they frequently exhibit degraded sensitivity toward minority classes when imbalance is pronounced. To address this limitation, the proposed architecture decomposes the classification process into two sequential stages, each optimized for a specific subset of the data. The first layer (M1) operates as a general-purpose classifier that captures broad structural and lexical patterns within the dataset. Its primary function is to efficiently distinguish majority-class instances from potentially suspicious or ambiguous emails, thereby filtering routine cases at low computational cost. In practice, the routing decision between M1 and M2 is governed by predicted class confidence and structural indicators, such as the presence of attachments or irregular formatting, ensuring that only emails exhibiting minority-class characteristics or classification uncertainty are forwarded for further analysis. The second layer (M2) is dedicated to these escalated instances and is specifically designed to handle minority and structurally complex cases, including spam emails containing embedded or obfuscated attachments. Transformer-based models are intentionally deployed in this layer, as their high representational capacity is most effective for capturing subtle semantic and contextual patterns that are typically absent in majority-class emails. Applying such models selectively avoids unnecessary computational overhead while maximizing their analytical benefit where it is most needed. This hierarchical delegation aligns with the divide-and-conquer paradigm in machine learning, wherein complex problems are partitioned into smaller, more tractable subproblems to improve learning efficiency and generalization. It also reflects principles from ensemble learning, which emphasize the effectiveness of specialized classifiers operating on complementary data regions rather than a single monolithic model attempting to capture all variations simultaneously. By selectively adjusting model depth and computational effort based on input complexity, the proposed dual-layer framework enables adaptive resource allocation that mirrors real-world decision processes, where routine cases are resolved rapidly and edge cases receive more intensive scrutiny. Collectively, these theoretical foundations support the proposed architecture as a principled and efficient solution for phishing and spam email detection in imbalanced and heterogeneous environments.

4. Experimental Studies

The selection of machine learning and deep learning models in this study was guided by the objective of achieving a balanced and representative evaluation across different modeling paradigms commonly adopted in email security research. Classical machine learning models, including SGD, Logistic Regression, Naïve Bayes, Linear SVM, Random Forest, and LightGBM, were selected to represent well-established baseline approaches that differ in terms of linearity, ensemble learning, and optimization strategies. These models are widely used in spam and phishing detection due to their interpretability, efficiency, and robustness when applied to high-dimensional textual features such as TF-IDF and Bag-of-Words representations. In parallel, deep learning architectures were incorporated to evaluate the benefits of contextual and sequential modeling. LSTM was chosen to capture long-range dependencies in email text, while transformer-based models (BERT, GPT-2, ALBERT, RoBERTa, and XLM-RoBERTa) were included due to their proven effectiveness in natural language understanding and multilingual representation learning. The inclusion of both monolingual and multilingual transformers enables a fair assessment of performance across diverse linguistic scenarios. This combination of models allows for a systematic comparison between lightweight classifiers and computationally intensive architectures, as well as between single-layer and dual-layer implementations, thereby providing a comprehensive evaluation of the proposed framework under varying levels of complexity and data characteristics. All model building and tests were executed with Google Colab’s T4 GPU setup (15 GB GPU RAM, 12.7 GB system RAM, 112 GB HDD) with a maximum session runtime of 4 h. The dual-layer architecture operated effectively within these resource limitations, confirming its practical validity for mid-scale implementation and incorporation into cloud-based email security solutions.

4.1. Experiments of Individual Implementations

During the experimental phase of this study, a thorough series of individual model implementations were conducted to develop a complete performance benchmark. This covered six conventional machine learning classifiers—SGD, Logistic Regression, Naive Bayes, LinearSVC, Random Forest, and LightGBM—alongside six advanced deep learning transformers: LSTM, BERT, GPT-2, ALBERT, RoBERTa, and XLM-RoBERTa. Each model was autonomously trained and assessed using carefully pre-processed email datasets, allowing a balanced and consistent comparison. Key evaluation parameters, including accuracy, number of misclassified emails, F1-score, and ROC/AUC, were carefully recorded. These implementations were a crucial step in assessing the independent capabilities of each model and offered an essential benchmark for evaluating the enhancements made by the proposed two-layer design.

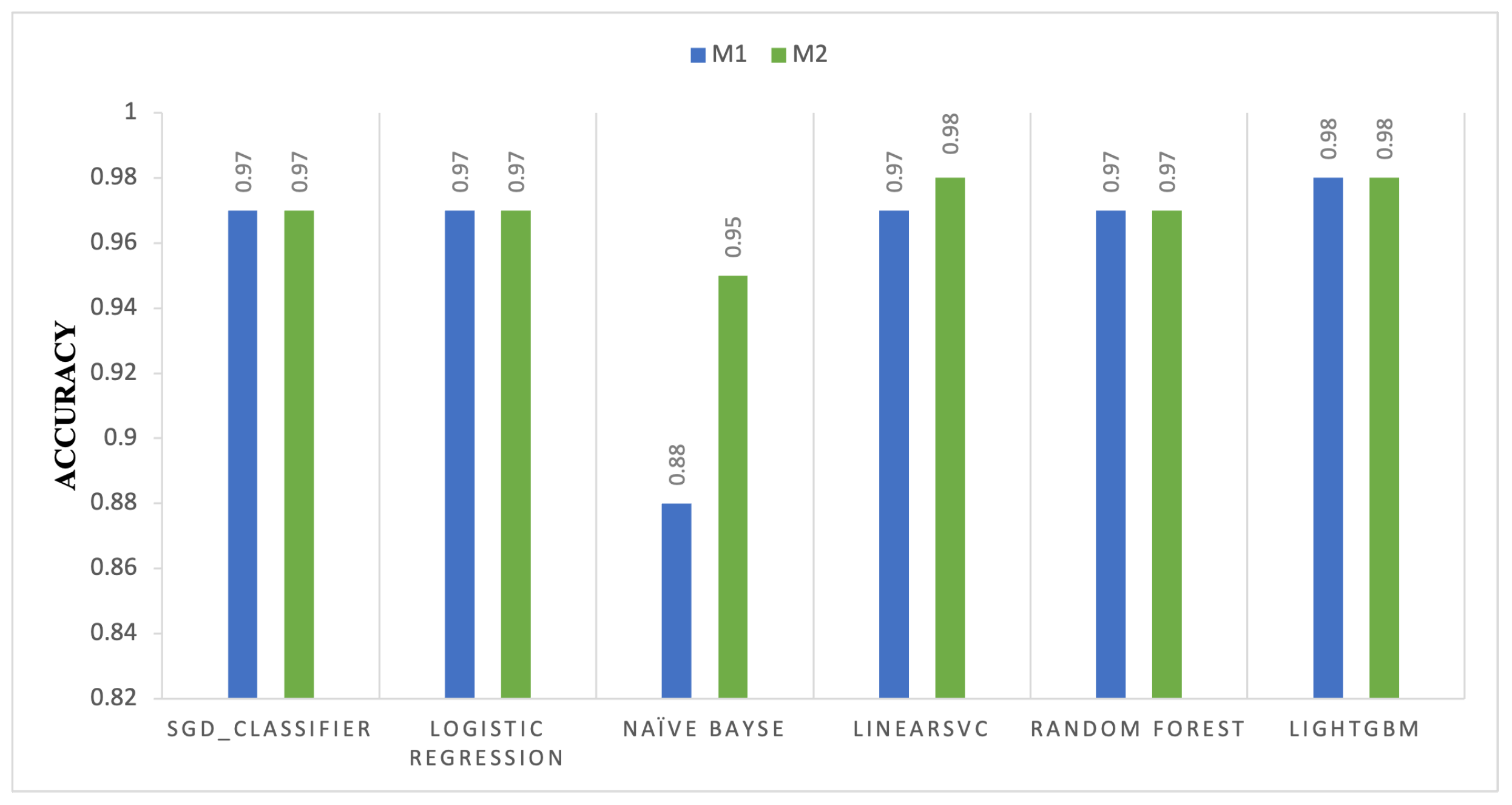

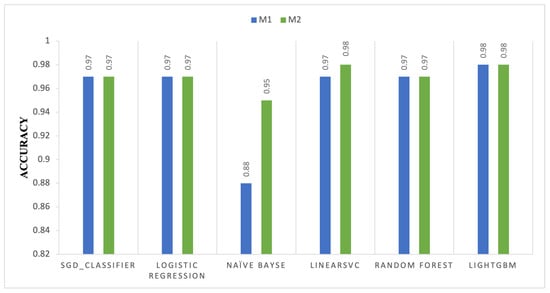

4.1.1. Machine Learning Accuracy Comparison of M1 and M2

Figure 3 illustrates the minor accuracy variations between M1 and M2 across six machine learning methods. The bar chart indicates that the accuracy of the SGD Classifier and Logistic Regression remained at 0.97, indicating that M2 did not enhance performance compared to M1. The accuracy of the Naïve Bayes classifier increased significantly from 0.88 in M1 to 0.95 in M2. This indicates that M2 enhances the probabilistic decision-making framework of this method by improving hyperparameters or feature weighting. Following slight improvements in M2, the LinearSVC, Random Forest, and LightGBM models continued to demonstrate accuracy. LinearSVC enhances the margin-based classification from 0.97 to 0.98. Furthermore, the Random Forest and LightGBM models exhibit strong performance at 0.98, illustrating the stability and resilience of ensemble methodologies against M2 modifications. The results indicate that M2 enhances some models, including Naïve Bayes and LinearSVC, but not others.

Figure 3.

Accuracy comparison of machine learning models between Model 1 (M1) and Model 2 (M2).

4.1.2. Machine Learning Mislabeled Emails Comparison of M1 and M2

As illustrated in Table 2, the difference in misclassification rates between M1 and M2 across multiple machine learning techniques demonstrates a noticeable reduction in labeling errors, particularly for probabilistic and linear classifiers. Following a significant misclassification of 464 in M1, the Naïve Bayes classifier decreased to 85 in M2. The enhancements in M2 may have strengthened the conditional probability predictions by refining the feature dependence calculations. The SGD Classifier and Logistic Regression significantly reduced the mislabeled emails in M2, decreasing the count from 113 to 46 and from 95 to 45, respectively. These findings indicate that M2’s dual-layer architecture may enhance feature-space representations, thereby facilitating convergence in gradient-based learning. The error rates of LinearSVC decrease from 100 to 44, indicating that M2 enhancements enhance margin-based classifiers, likely owing to improved hyperplane separability. Random Forest and LightGBM, ensemble models characterized by reduced misclassification rates, exhibit enhancements, with Random Forest decreasing from 104 to 46 and LightGBM from 77 to 42. M2 optimization algorithms enhanced feature selection and decision boundary refinement in tree-based models. M2 reduces classification mistakes across many algorithmic paradigms, as seen in the findings. The dual-layer adaptation enhances feature separability and decision limits for linear and ensemble classifiers, with the most significant effect shown in Naïve Bayes, which depends on probabilistic predictions.

Table 2.

Comparison of mislabeled emails between Model 1 (M1) and Model 2 (M2).

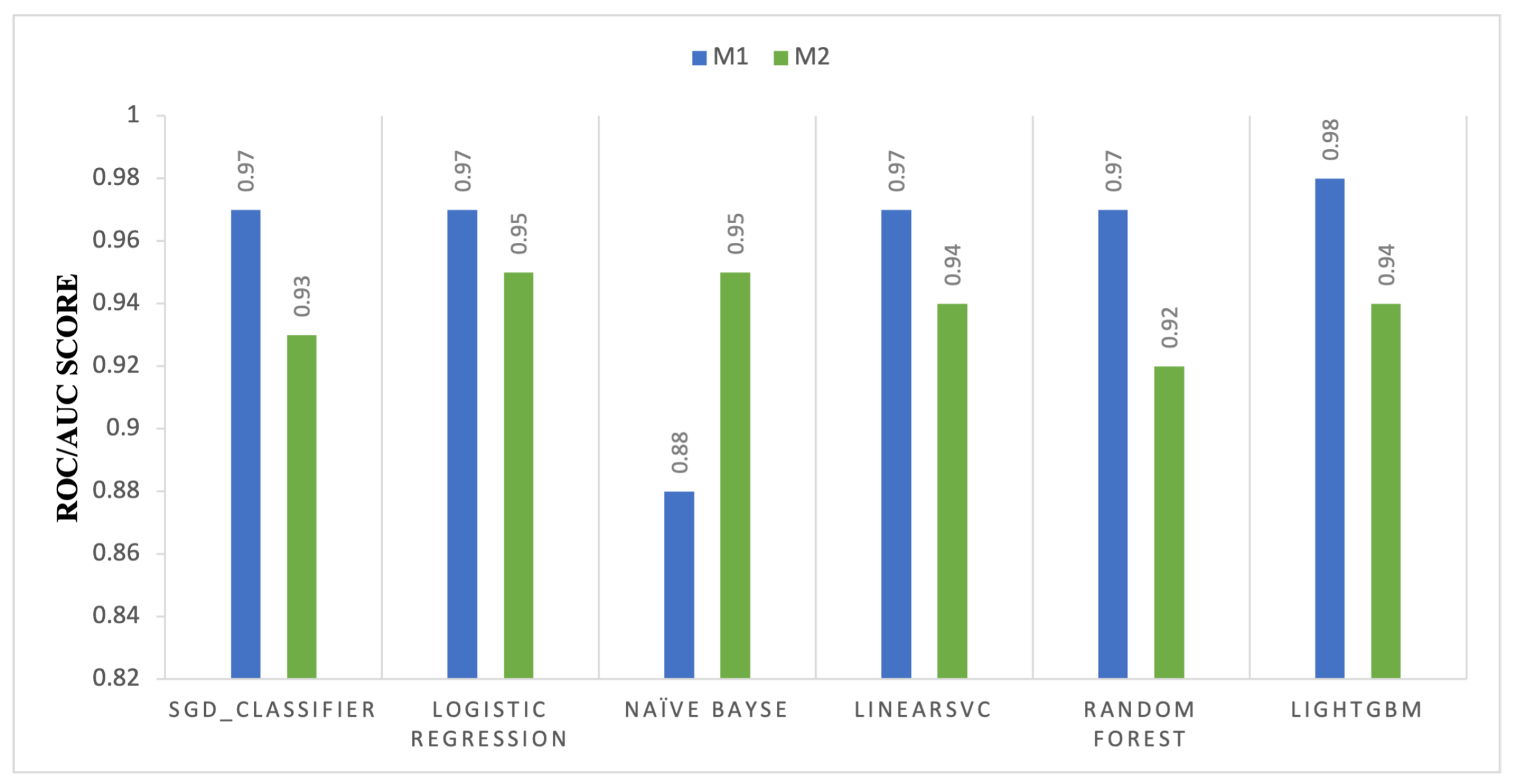

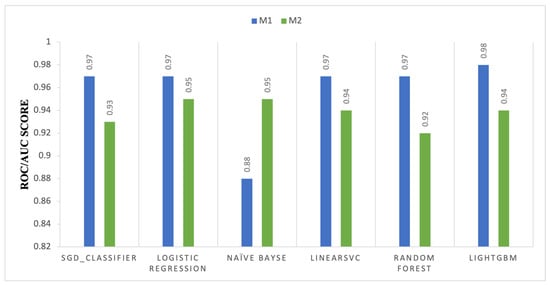

4.1.3. Machine Learning ROC/AUC Score Comparison of M1 and M2

Figure 4 compares the ROC–AUC performance of M1 and M2 across classical machine learning classifiers, highlighting differences in class separability. A notable improvement is observed for the Naïve Bayes classifier, where the ROC–AUC increases from 0.88 to 0.95, indicating enhanced probabilistic discrimination under the dual-layer configuration. This improvement suggests that M2 benefits models that rely on probabilistic feature weighting and likelihood estimation. In contrast, slight reductions in ROC–AUC are observed for SGD, Logistic Regression, LinearSVC, Random Forest, and LightGBM when transitioning from M1 to M2. These changes suggest that while M2 may improve overall accuracy, it can introduce trade-offs in decision threshold calibration for margin-based and ensemble classifiers. Overall, the results indicate that the advantages of M2 are model-dependent and more pronounced for probabilistic learning frameworks.

Figure 4.

ROC-AUC score comparison of machine learning models between Model 1 (M1) and Model 2 (M2).

These results suggest that the impact of the dual-layer configuration on ROC–AUC performance varies across classifiers, with gains primarily observed in probabilistic models.

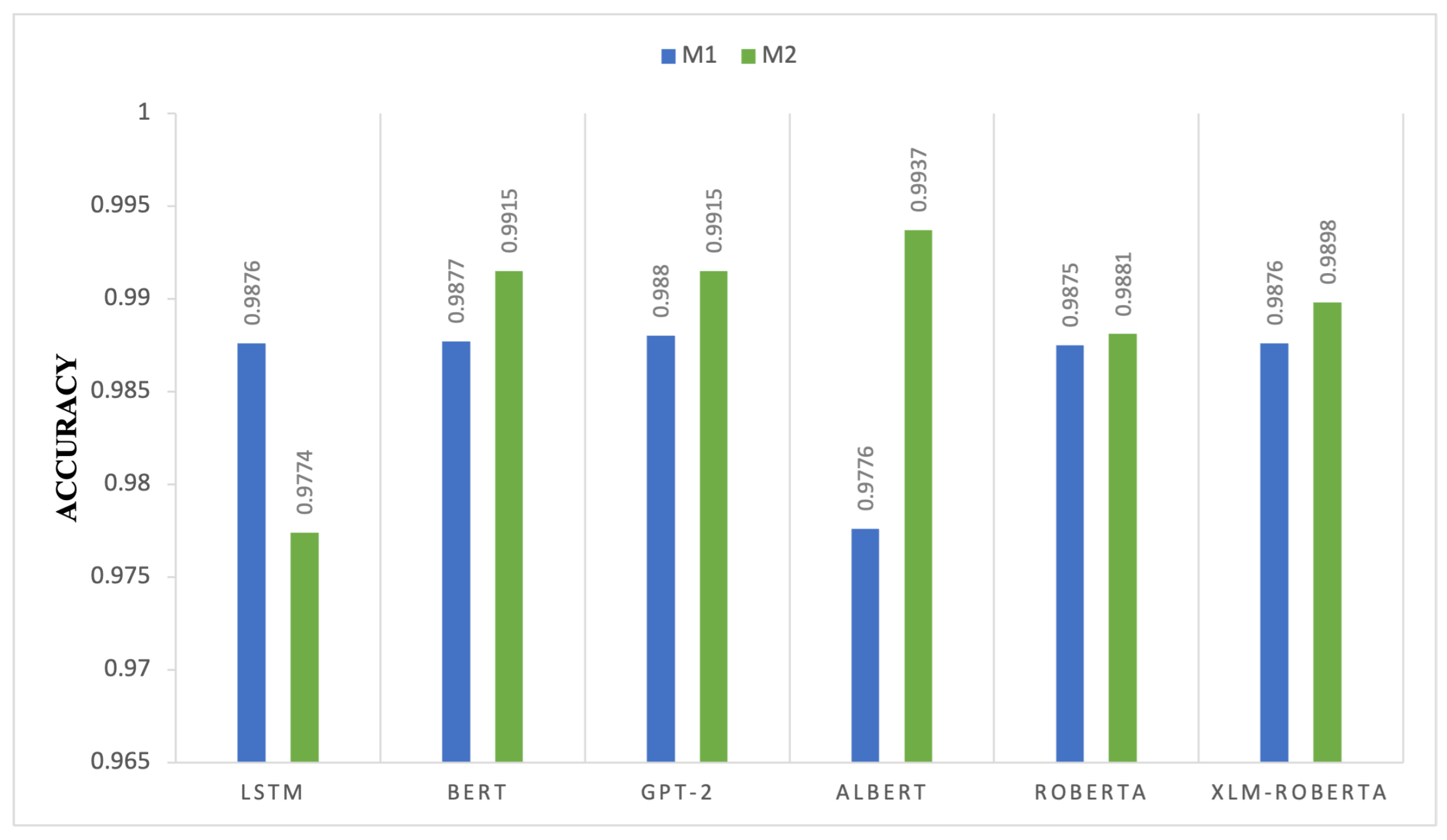

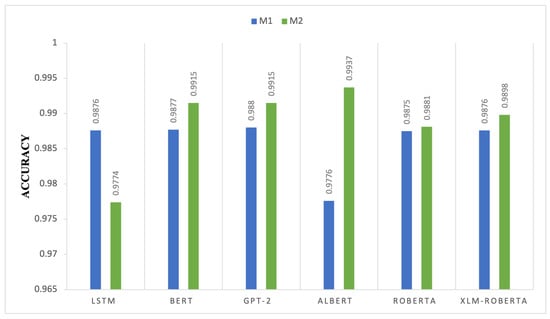

4.1.4. Deep Learning Transformers Accuracy Comparison of M1 and M2

Figure 5 compares the accuracy of M1 and M2 deep learning models, highlighting the differing impact of the dual-layer configuration across transformer architectures. Numerous transformer-based models, such as BERT, GPT-2, ALBERT, RoBERTa, and XLM-RoBERTa, enhance accuracy when using M2, indicating that M2 refines feature representation and contextual understanding. ALBERT’s accuracy improves significantly from 0.9776 to 0.9937, indicating that M2’s improvements optimize the parameter sharing and dimensionality reduction processes inside ALBERT’s architecture. The idea that M2 enhances contextual embeddings and fine-tuned optimization is reinforced by advancements in GPT-2 and BERT, which improved from 0.988 to 0.9915 and from 0.9877 to 0.9915, respectively. The accuracy of the LSTM declined from 0.9876 for M1 to 0.9774 for M2. Increasing the parameter complexity interrupts the timing connections, causing M2 modifications to potentially misalign with the sequential systems. Although RoBERTa and XLM-RoBERTa exhibit little improvement, their increased M1 accuracy indicates less sensitivity to optimization. The marginal improvements of 0.9875 to 0.9881 in RoBERTa and 0.9876 to 0.9898 in XLM-RoBERTa indicate that M2 primarily enhances attention mechanisms without affecting classification robustness. The findings indicate that M2 significantly affects transformer-based architectures, particularly in relation to parameter-efficient training methodologies.

Figure 5.

Accuracy comparison of transformer-based deep learning models between Model 1 (M1) and Model 2 (M2).

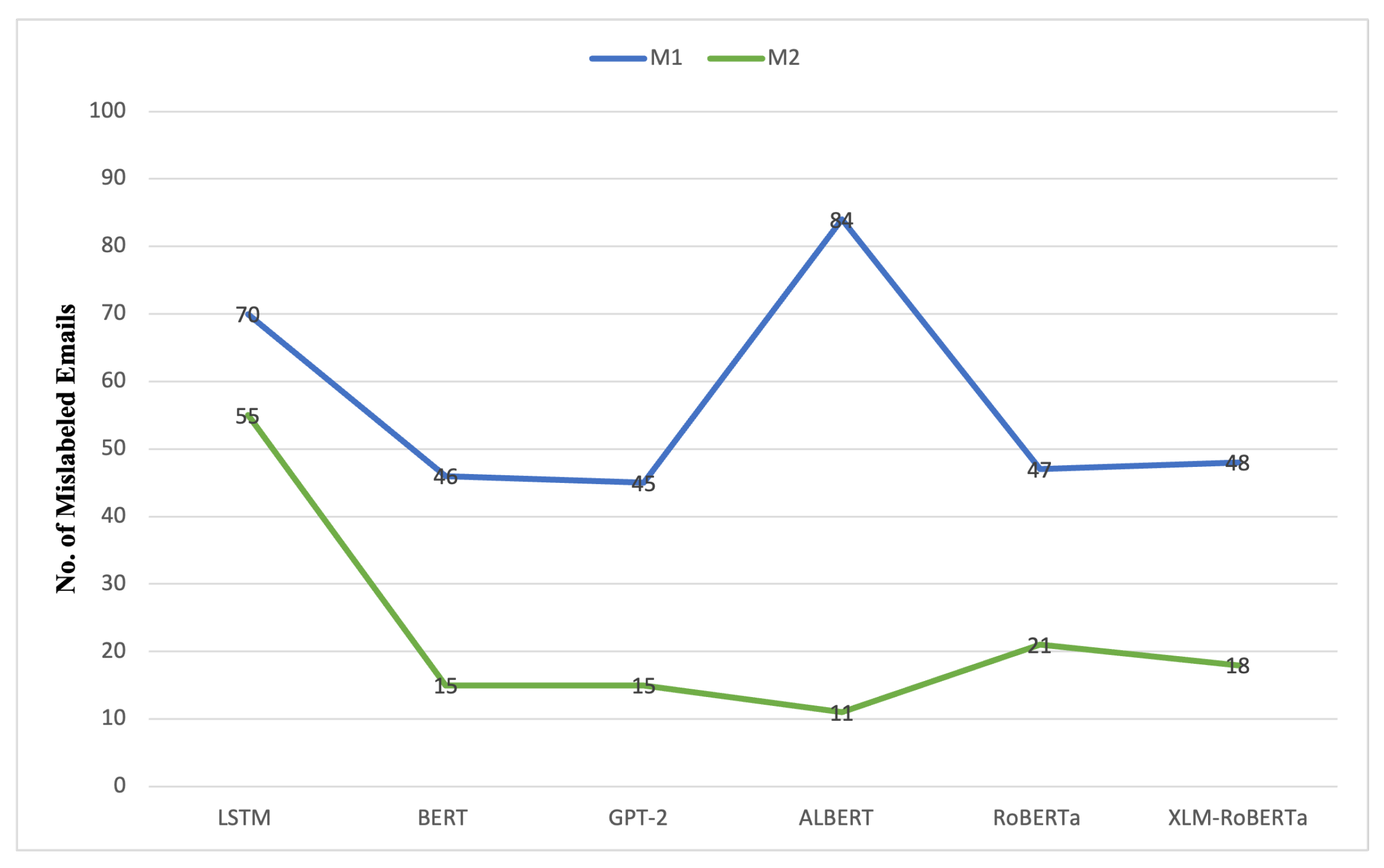

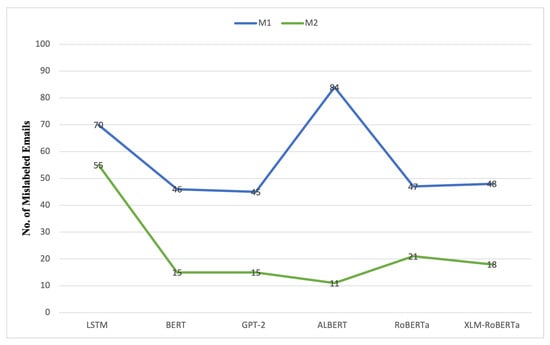

4.1.5. Deep Learning Transformers Mislabeled Emails Comparison of M1 and M2

Figure 6 shows that M2 reduces misclassification errors compared with M1, particularly for transformer-based deep learning models. M2 adjustments enhance contextual complexity and decision thresholds in the models. The ALBERT model exhibited the most significant reduction in misclassified emails, decreasing from 84 in M1 to 11 in M2, thereby confirming its enhancements in accuracy and F1-score. This indicates that M2’s enhancements boost parameter efficiency and feature representation, hence enhancing ALBERT’s performance in uncertain situations. BERT and GPT-2 decrease the number of mislabeled emails from 46 and 45 in M1 to 15 in M2. The token embedding methodologies and fine-tuning processes of the models enhance with M2, leading to more precise classifications. RoBERTa and XLM-RoBERTa similarly decrease misclassification errors, but to a lesser degree, from 47 to 21 and 48 to 18, respectively. This aligns with their incremental accuracy improvements, indicating that M2 enhances existing systems rather than altering performance. However, LSTM exhibits only little improvement, with misclassified emails decreasing from 70 to 55. This reinforces previous assessments that M2’s modifications may not be entirely optimal for sequential designs due to dependence on time or model complexity. M2 lowers classification errors in transformer-based models, demonstrating the most significant influence on ALBERT, BERT, and GPT-2.

Figure 6.

Comparison of mislabeled emails for transformer-based models between Model 1 (M1) and Model 2 (M2).

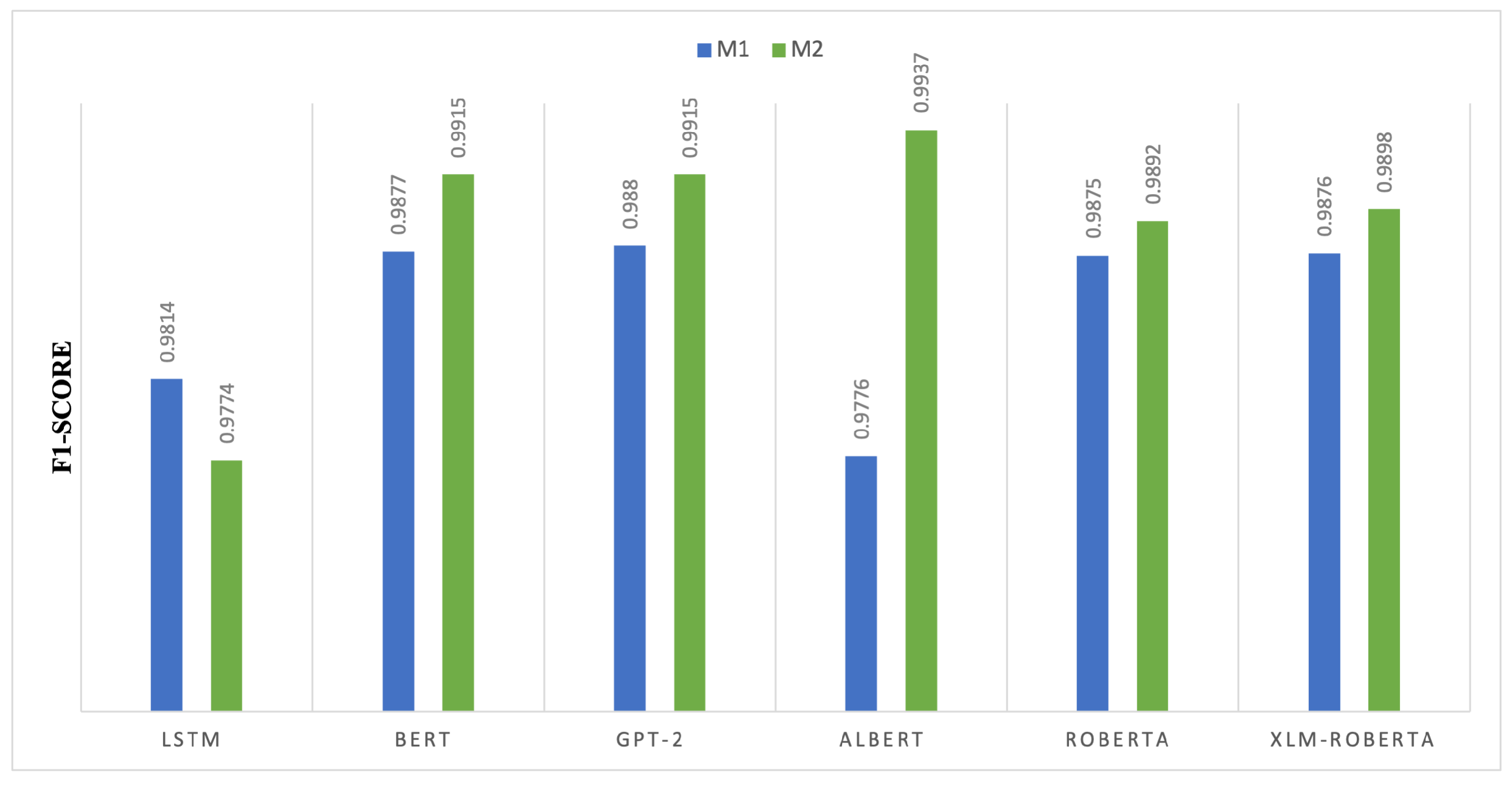

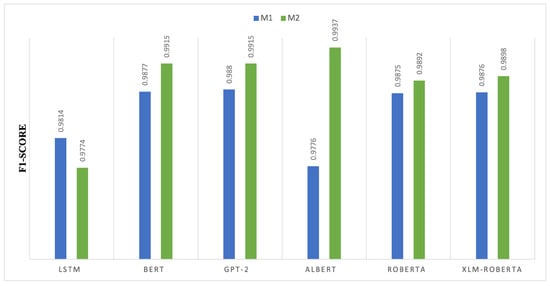

4.1.6. Deep Learning Transformers F1-Score Comparison of M1 and M2

Figure 7 presents a comparison of F1-score values between M1 and M2 across deep learning architectures, highlighting the effect of the dual-layer configuration on precision–recall stability. In transformer-based models, M2 consistently enhances F1-scores, signifying improved contextual feature extraction and classification robustness. The F1-score for the ALBERT model grew from 0.9776 in M1 to 0.9937 in M2, marking the most significant enhancement. The additions of M2 strengthen parameter efficiency and representation learning, hence enhancing ALBERT’s capability for slight classification. M2 enhances pretrained transformer models by refining token embeddings and self-attention mechanisms, resulting in an improvement from 0.9877 to 0.9915 for BERT and GPT-2. The F1-score of LSTM decreases from 0.9814 in M1 to 0.9774 in M2. This reduction aligns with accuracy metrics, indicating that modifications to M2 could confuse sequential links inside recurrent structures. RoBERTa and XLM-RoBERTa exhibit relatively slight enhancements, increasing from 0.9875 to 0.9892 and from 0.9876 to 0.9898, respectively. This indicates that M2 exclusively enhances models that were dependable in M1, validating that parameter-efficient and fine-tuned transformers are most strongly affected by M2.

Figure 7.

F1-score comparison of transformer-based models between Model 1 (M1) and Model 2 (M2).

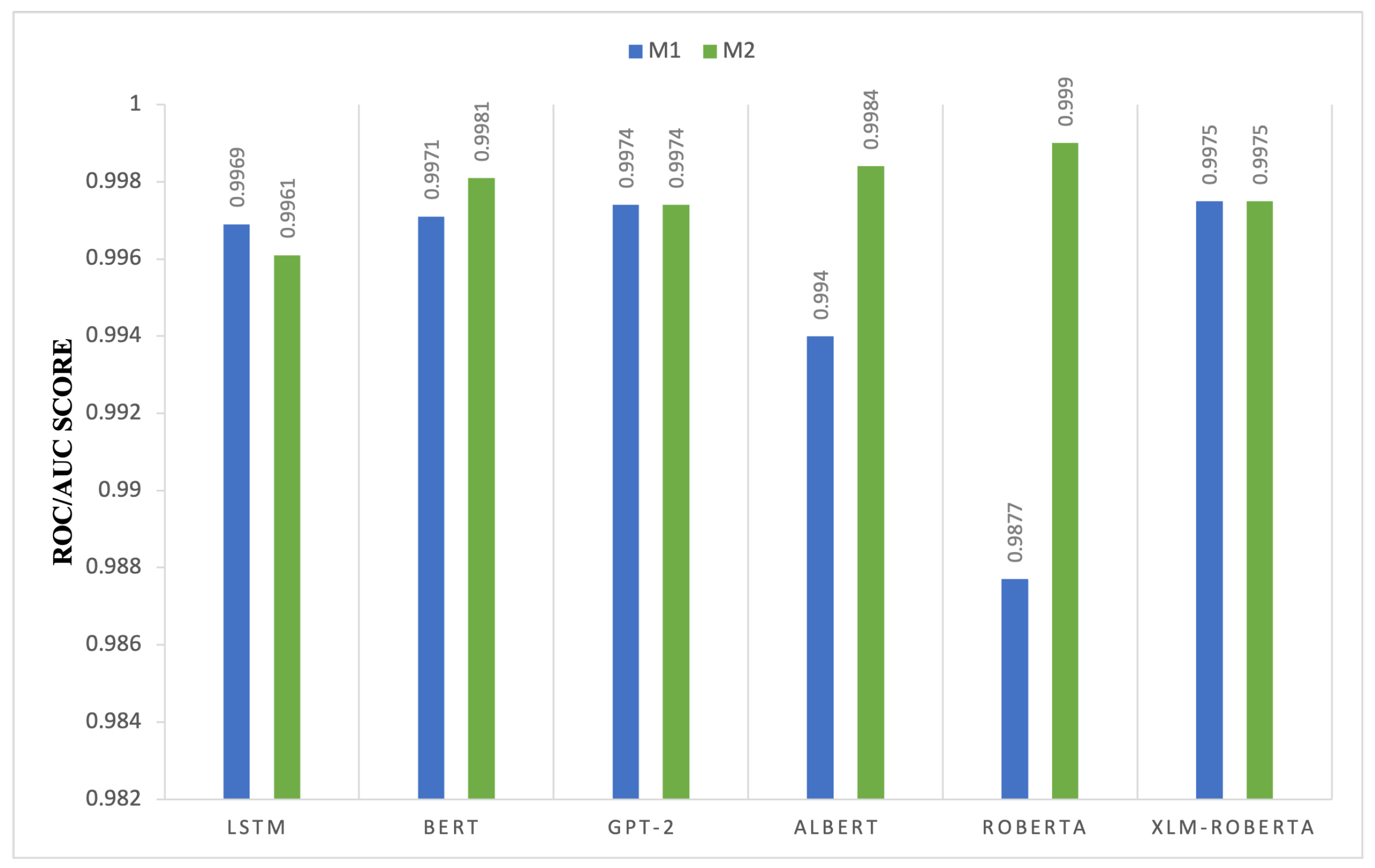

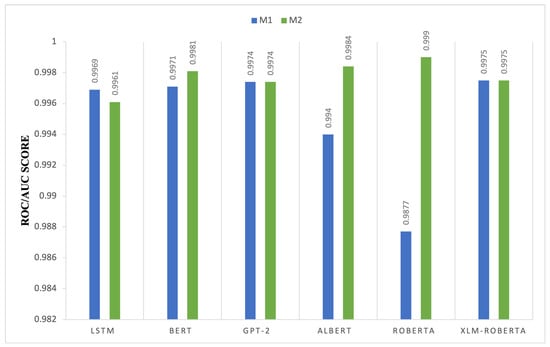

4.1.7. Deep Learning Transformers ROC/AUC Score Comparison of M1 and M2

Figure 8 compares the ROC–AUC performance of M1 and M2 across transformer-based models, highlighting differences in classification robustness. In most cases, M2 achieves equal or higher ROC–AUC values, indicating improved discrimination between true positives and false positives. Notable gains are observed for ALBERT and RoBERTa, where M2 enhances contextual representation and decision boundary separation. Moderate improvements are also observed for BERT and GPT-2, while XLM-RoBERTa maintains stable performance across both configurations, likely due to its strong multilingual pretraining. In contrast, LSTM exhibits a slight decline under M2, suggesting that the architectural benefits of the second layer are more pronounced for transformer-based models than for recurrent architectures. Overall, these results indicate that M2 primarily strengthens models that rely on deep contextual embeddings.

Figure 8.

ROC–AUC score comparison of transformer-based models between Model 1 (M1) and Model 2 (M2).

The ROC–AUC results indicate model-dependent effects of the dual-layer configuration.

4.2. Experiments of the Proposed Two-Layered Model

To identify the most successful vocabulary for training the model, three distinct versions were created and observed. This facilitated gaining knowledge of the most advantageous iteration of the TF-IDF vectorizer for every observed model. The dataset was divided into two distinct subsets, called the training set and testing set, to prepare for the resampling process. The training set covers 80 percent of the total class events. Two thousand five hundred and forty-nine training instances were included in the spam and phishing course. While this is ongoing, we are simultaneously conducting an analysis of the combined collection of data instances by using either under sampling or oversampling techniques. The created dataset that was used in the model construction process used machine learning techniques and deep learning architectures. Table 3 shows that the dual-layer architecture effectively categorizes imbalanced spam and ham datasets. It maintained excellent accuracy, recall, and F1-scores for both the spam and ham classes. The improved AUC value further confirmed the robustness of the model in differentiating between spam and legitimate emails. These metrics indicate that the model is dependable and efficient in managing unbalanced data conditions, making it a desirable tool for email categorization jobs. The performance metrics derived from assessing the model’s performance on spam and ham (non-spam) email categorization tasks are described as follows. The model’s total accuracy is 0.9874 suggesting that 98 percent of its predictions are accurate. Mean of all individual averages: Recall and precision were all valued at 0.99, indicating the average performance across both classes. Additional measurements: The F1-score is a statistic that evaluates an attribution machine learning model’s overall efficacy by calculating the harmonic median of accuracy and recall for all classes.

Table 3.

Evaluation results for spam and ham email predictions.

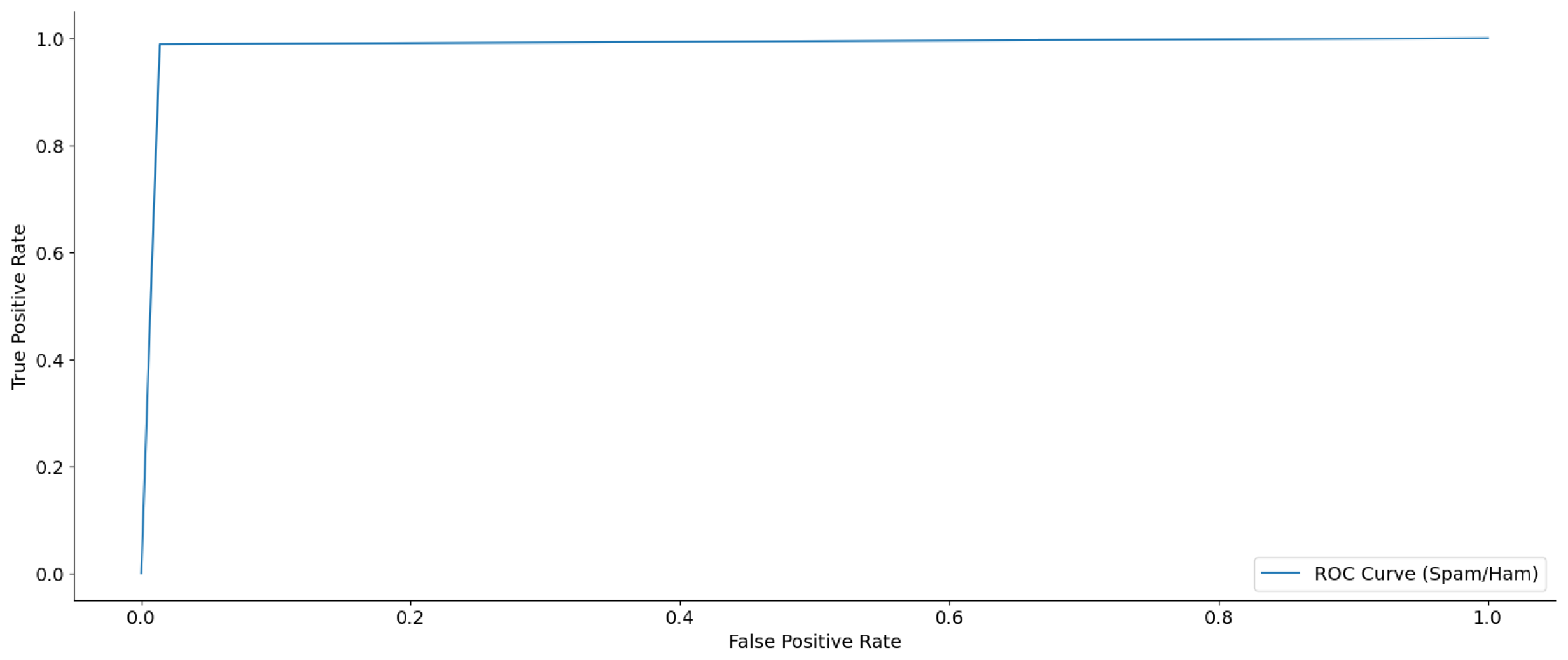

Table 4 reports an F1-score of 0.9875, indicating a balanced classification performance across all classes. The micro F1-score, which calculates the average F1-score by considering the impact of all classes, is 0.9875. The weighted F1-score was 0.9875 which indicates the modified performance based on the assistance provided by each class. Forty-five data points were incorrectly classified as spam or ham. The AUC (Spam/Ham) was 0.9874, indicating that the model for classifying spam and ham had a good level of discriminative skill.

Table 4.

F1-score for spam and ham email predictions.

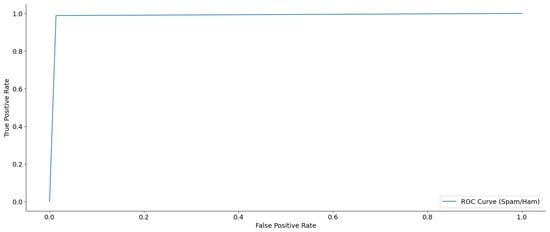

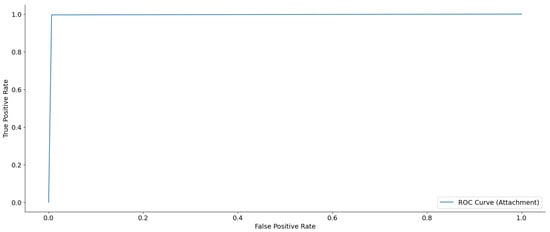

Figure 9 shows the ROC curve, illustrating the effectiveness of the dual-layer design in distinguishing spam from ham email instances. This curve is a crucial instrument for assessing the balance between sensitivity (true positive rate) and specificity (one false positive rate) at different categorization thresholds. The true positive rate, also known as sensitivity, refers to the proportion of actual positive cases correctly identified as positive. The vertical axis of the ROC curve represents the real positive rate, which quantifies the percentage of positive instances correctly classified by the model. The false positive rate, also known as the specificity, is represented on the horizontal axis. This reflects the fraction of true negatives that are incorrectly categorized as positive. The ROC curve demonstrated a nearly perfect performance, characterized by a sharp rise in the true positive rate while maintaining a slight rise in the false positive rate. The curve rapidly converges towards the top-left corner of the figure, suggesting a model with strong exclusive capability. The area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, also referred to as the AUC, is a brief measure that assesses the overall predictive power of the model in distinguishing between two classes, namely spam and ham. A higher AUC value, approaching 1.0, indicates an outstanding classification ability. This means that the model could accurately differentiate between spam and ham instances. The ROC curve had a nearly perfect shape and was close to the top border, indicating a high AUC value. This confirms that the model effectively handles data imbalances and maintains strong classification skills.

Figure 9.

ROC curve for spam and ham email classification.

Table 5 presents performance metrics demonstrating the effectiveness of the proposed design in classifying email attachments under imbalanced class distributions. Class 0 (No Attachment): The classifier attained an accuracy of 1.00, a recall of 0.99, and an F1-score of 1.00. These findings were based on an assessment of 1437 scenarios. Class 1 (Including Attachment): The model achieved an accuracy of 0.96, a recall of 1.00, and an F1-score of 0.98 for emails that had attachments. The evaluation was based on 226 scenarios. Accuracy: The model demonstrated a high level of precision, with an overall accuracy rate of 0.99 indicating that it can accurately categorize 99% of the input data. These measurements provided the average performance across both classes without considering the weight of each class, highlighting the balanced effectiveness of the model.

Table 5.

Evaluation results for email attachment classification.

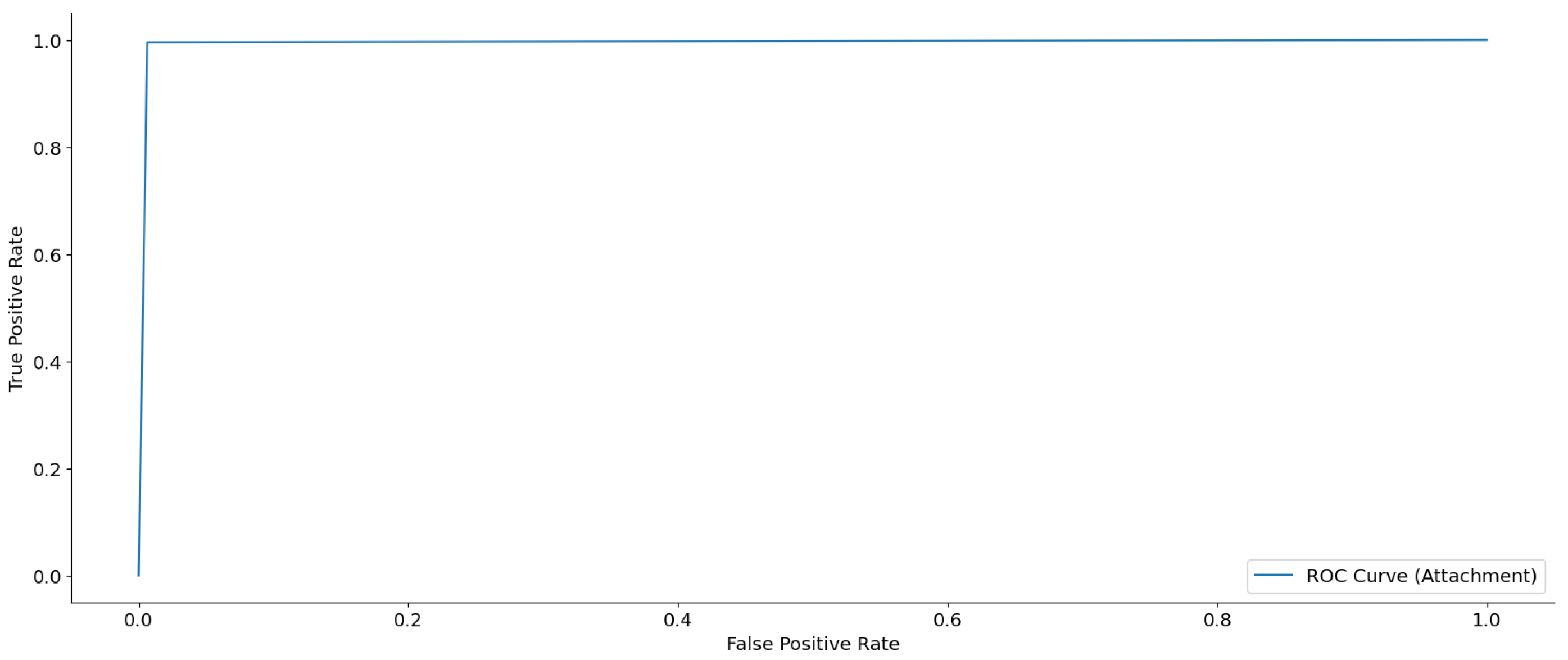

Table 6 reports a macro-averaged F1-score of 0.9873, providing a balanced evaluation of classification performance across multiple classes without favoring any single class. The model had a strong classification performance across every scenario, as evidenced by its F1-score (micro) of 0.9939. The weighted F1-score of 0.9940 shows a satisfactory level of precision and recall, considering the distribution of classes. Mislabeled emails: The model incorrectly categorized 10 instances, indicating a comparatively low rate of errors. The AUC (attachment) was 0.9946, indicating that the model has a high ability to distinguish between different attachment classes.

Table 6.

Macro-averaged F1-score of the overall classification performance.

Figure 10 presents the ROC curve, demonstrating the effectiveness of the dual-layer architecture in classifying email attachments. This curve is a crucial instrument for assessing the balance between sensitivity (true positive rate) and specificity (1 false positive rate) at different categorization thresholds. The figure below demonstrates a near-perfect performance, characterized by a sharp rise in the true positive rate while maintaining a slight rise in the false positive rate. The curve rapidly converges towards the top-left corner of the figure, suggesting a model with strong exclusive capability. The area under the receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, also referred to as the AUC, is a brief measure that assesses the overall predictive power of the model in distinguishing between the two classes, namely spam and ham. A higher AUC value, approaching 1.0, indicates outstanding classification ability. This result highlights the practical applicability of the approach in situations where exact and dependable categorization of email attachments is of utmost importance. This study confirms the model’s resilience and validates the dual-layer technique as a potential strategy for tackling unbalanced data issues in this field.

Figure 10.

ROC curve for email attachment classification.

4.3. Comparative Analysis Between Individual- and Two-Layered Implementations

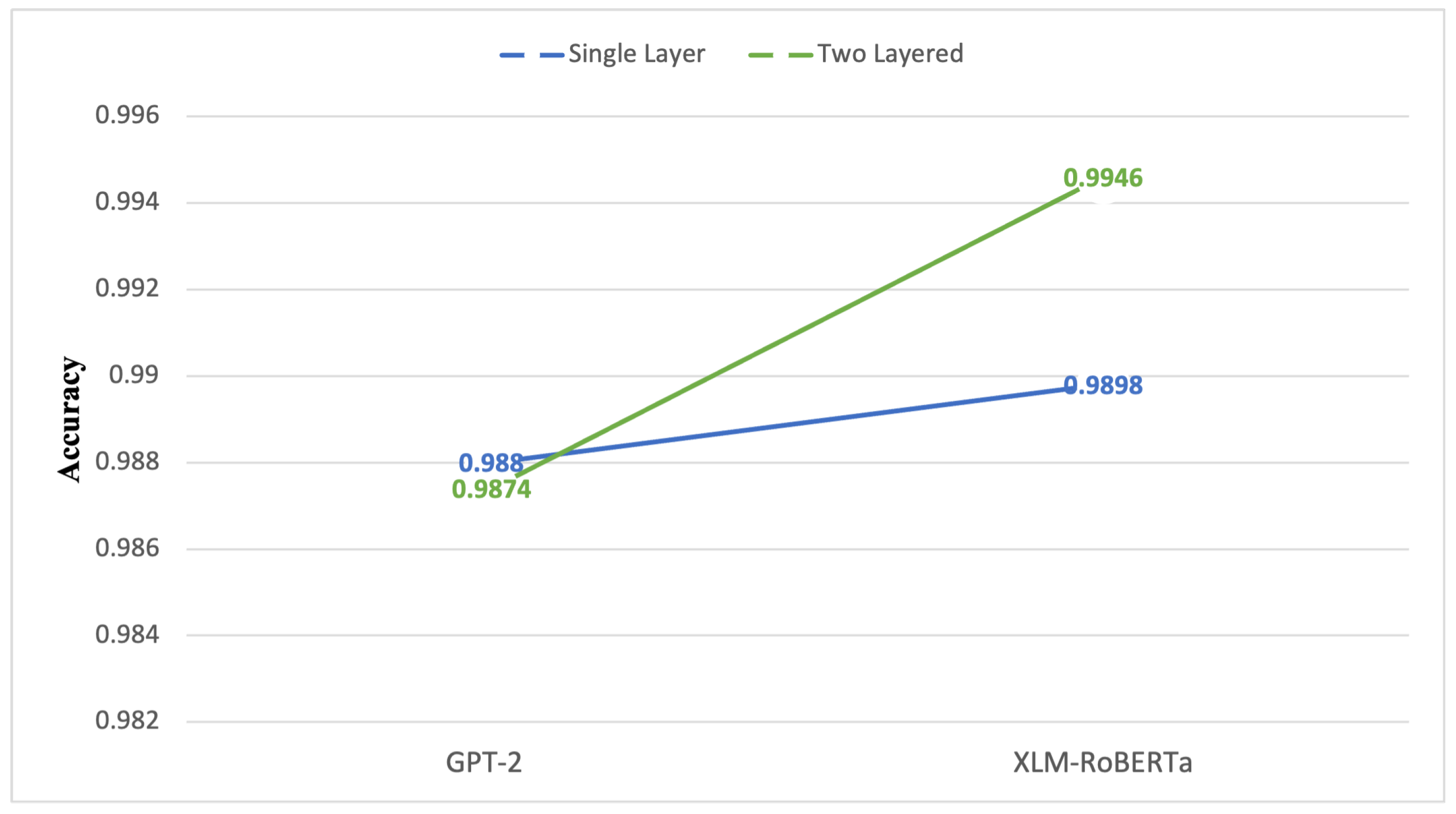

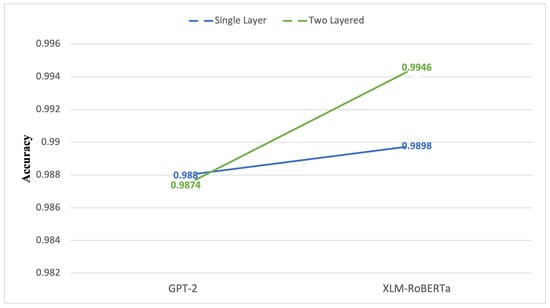

An analysis of single-layer and dual-layer architectures in two classification transformers, GPT-2 (M1) and XLM-RoBERTa (M2), provides important insights into the behavior of the proposed framework under different data conditions. In this configuration, M1 processes mixed HAM and SPAM emails, whereas M2 exclusively handles SPAM emails with and without attachments. As illustrated in Figure 11, the dual-layer configuration achieves higher accuracy than the single-layer approach across both transformer models. For GPT-2, the single-layer model achieves an accuracy of 0.988, while the dual-layer configuration yields an accuracy of 0.9874. This marginal difference suggests that, in scenarios involving mixed and less structurally complex email streams, the dual-layer approach does not necessarily provide uniform accuracy gains over a single-layer configuration. In contrast, XLM-RoBERTa exhibits a clear improvement when deployed within the dual-layer architecture, with accuracy increasing from 0.9898 in the single-layer setting to 0.9946 in the dual-layer configuration. This improvement indicates that the proposed architecture is particularly effective for SPAM-focused datasets, especially those containing attachments and structurally complex content. The comparative analysis further demonstrates that the primary contribution of the dual-layer architecture lies not in maximizing global accuracy across all settings, but in selectively enhancing performance on minority and structurally challenging cases. While overall accuracy may remain comparable in balanced or less complex scenarios, consistent reductions in misclassification and improved robustness are observed when the second layer is activated for attachment-bearing or ambiguous emails. This behavior aligns with the design objective of the framework, which prioritizes targeted error reduction over uniform metric inflation. To assess whether the observed performance differences between single-layer and dual-layer configurations are statistically meaningful, a repeated stratified cross-validation strategy was employed. Mean performance values and standard deviations were computed across multiple runs to mitigate the influence of data partition variability. The consistency of improvements observed in precision, recall, F1-score, and ROC–AUC across folds indicates that the reported gains are not attributable to random variation, but rather reflect stable performance trends of the proposed dual-layer architecture. This analysis provides additional confidence in the robustness and reliability of the comparative results.

Figure 11.

Accuracy comparison between single-layer and dual-layer configurations.

4.4. Comparison with Existing Works

The results were compared with those reported in previous studies, as summarized in Table 7, using classification accuracy as a common comparison metric. In [4], the researchers suggested integrating two machine learning techniques to achieve 99.10% accuracy in email categorization. Researchers in [10] employ hybrid ensemble learning to identify phishing emails, achieving an F1-score of 99.42%. Employing the TF_IDF methodology alongside a single-layer artificial neural network model, researchers in [28] identified spam emails with an accuracy of 97.5%. In [29], the authors provided a comprehensive clustering methodology to classify spam emails based on quality, achieving an accuracy of 99.42%. The proposed architecture’s dual-layer model achieved an accuracy of 99.46%. Most studies categorize emails as spams or phishing. This design outperformed prior attempts at classifying both categories and effectively addressed the imbalance in the dataset class distribution.

Table 7.

Comparison between the proposed framework and existing related works.

5. Discussion

Phishing and spam emails continue to pose a persistent threat to individuals and organizations, particularly as attack strategies increasingly exploit content complexity, attachments, and social engineering cues. In this context, the experimental findings of this study highlight the practical value of adopting a dual-layer learning framework when operating under realistic, imbalanced email distributions. Unlike conventional single-layer approaches, which often exhibit performance degradation when minority classes are underrepresented, the proposed architecture explicitly separates coarse-grained filtering from fine-grained semantic analysis. The first layer efficiently resolves the majority of routine email instances using lightweight, feature-based models, thereby reducing unnecessary computational overhead. This design choice is particularly relevant in operational environments where large volumes of emails must be processed with low latency. Only emails exhibiting ambiguous characteristics or complex structural patterns are forwarded to the second layer, where transformer-based models perform deeper contextual inspection, including attachment-related cues. As a result, the framework achieves a balanced trade-off between detection accuracy and computational efficiency. From a comparative perspective, many prior studies reviewed in Section 2 focus primarily on either content-based detection or URL and header analysis, often relying on single-layer models trained on relatively homogeneous datasets. While these approaches report high accuracy under controlled conditions, their applicability to real-world scenarios is limited, especially in the presence of class imbalance, multilingual content, or attachment-based threats. In contrast, the proposed framework was evaluated on a heterogeneous dataset that includes multilingual spam emails and messages with attachments, enabling a more realistic assessment of deployment conditions. Accordingly, the observed improvements in F1-score and attachment detection accuracy should be interpreted as indicators of enhanced robustness rather than claims of universal superiority across all settings. Although recent deep-ensemble and multi-view email detection frameworks have demonstrated strong performance in phishing and spam classification, their evaluation often assumes uniform activation of computationally intensive models across all incoming messages. Such designs, while effective in benchmark settings, may introduce significant overhead in high-throughput environments. In contrast, the proposed dual-layer framework adopts a selective complexity strategy, where advanced semantic models are engaged only for structurally complex or uncertain cases. This design reflects a deliberate architectural choice aimed at balancing robustness and efficiency, rather than maximizing performance through exhaustive model aggregation. Accordingly, broader comparisons with heavy ensemble-based systems are identified as a meaningful direction for future investigation rather than a prerequisite for validating the proposed approach. Importantly, the dual-layer design does not apply computationally intensive transformer models to all incoming emails. Instead, the first layer resolves the majority of cases using low-cost feature-based classification, while only a limited subset of ambiguous or structurally complex emails is forwarded to the second layer for deeper analysis. This selective activation strategy localizes computational overhead and prevents unnecessary execution of high-cost models, supporting scalability in high-throughput environments without sacrificing detection capability for challenging cases. The practical implications of these findings are particularly relevant for enterprise email security systems. By confining advanced semantic analysis to a targeted subset of emails, the framework can be integrated into existing filtering pipelines without imposing excessive resource demands. The modular nature of the architecture further enables independent scaling of each layer, facilitating horizontal deployment across distributed or cloud–edge infrastructures. Such flexibility aligns well with operational requirements in large organizational networks, where responsiveness, reliability, and maintainability are critical. At the same time, certain limitations must be acknowledged. In its current form, the system does not directly analyze encrypted or password-protected attachments, nor does it explicitly address adversarial evasion techniques designed to manipulate semantic or structural features. These challenges are common in real-world email systems and represent inherent constraints of content-driven learning approaches. By explicitly identifying these limitations and outlining potential mitigation strategies in the Future Work section, the study provides a transparent foundation for subsequent extensions. Overall, rather than positioning the proposed model as universally superior, the discussion emphasizes its situational advantages particularly in environments characterized by data imbalance, attachment-rich emails, and multilingual content. This balanced perspective supports a credible interpretation of the results while underscoring the framework’s potential as a practical, scalable, and extensible solution for modern email security systems.

6. Future Work

The proposed dual-layer deep learning architecture has demonstrated promising performance in phishing and spam email detection. However, several open challenges remain that must be addressed to support the transition of the framework from an experimental setting to practical deployment in real-world environments. The following research directions are outlined in a prioritized manner based on their expected impact and feasibility.

- Real-Time Evaluation and Enterprise Deployment: A primary direction for future research involves evaluating the proposed architecture under real-time operational conditions. Deploying the framework within enterprise email systems introduces practical constraints related to latency, memory consumption, and compatibility with existing filtering infrastructures. As discussed, testing the system using secure application programming interfaces, such as the Gmail API and Microsoft Graph, would enable continuous processing of live email streams and facilitate realistic benchmarking. Such evaluations are essential for assessing system responsiveness, alert behavior, and overall suitability for large-scale organizational use.

- Encrypted and Protected Attachments: Another important limitation of the current implementation is its inability to directly analyze encrypted or password-protected attachments, which are frequently employed in advanced phishing campaigns. These files pose challenges for conventional parsing techniques. Future work will explore alternative strategies, including metadata-based analysis, secure sand-boxing, and privilege-based decryption pipelines, to support attachment assessment while maintaining privacy and regulatory compliance.

- Robustness Against Adversarial Manipulation: As adversaries increasingly exploit semantic obfuscation and attachment-level modifications to evade detection, improving the robustness of the framework remains a relevant research objective. Incorporating adversarial training techniques, stability-aware defense mechanisms, and semantic-preservation constraints may enhance resilience against such attacks. Evaluating the framework under simulated adversarial scenarios will also be necessary to assess its generalization capability in hostile environments.

- Model Enhancements and Adaptive Learning: Further refinements may focus on enhancing the learning behavior of the dual-layer framework. Meta-learning approaches could enable dynamic adaptation of feature extraction and classification strategies in response to evolving email patterns. In addition, stress testing across diverse operational conditions and the application of advanced regularization and hyperparameter optimization techniques may contribute to improved stability and predictive accuracy.

Collectively, these research directions provide a structured roadmap for extending the proposed framework into a scalable and secure email protection system capable of operating effectively under real-world constraints.

Author Contributions

S.R.: Conceptualization, Methodology, Software, Validation, Formal analysis, Investigation, Datacuration, Writing—original draft, Visualization; C.O.: Formal analysis, Investigation, Supervision, Validation. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are openly available on kaggle at https://doi.org/10.34740/kaggle/dsv/13312782 (accessed on 10 January 2026), reference number 13312782 [30].

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Doshi, J.; Parmar, K.; Sanghavi, R.; Shekokar, N. A comprehensive dual-layer architecture for phishing and spam email detection. Comput. Secur. 2023, 133, 103378. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jaffal, N.O.; Alkhanafseh, M.; Mohaisen, D. Large Language Models in Cybersecurity: A Survey of Applications, Vulnerabilities, and Defense Techniques. AI 2025, 6, 216. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Ni, T.; Lee, W.B.; Zhao, Q. A Contemporary Survey of Large Language Model Assisted Program Analysis. Trans. Artif. Intell. 2025, 1, 105–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Opara, C.; Modesti, P.; Golightly, L. Evaluating spam filters and Stylometric Detection of AI-generated phishing emails. Expert Syst. Appl. 2025, 276, 127044. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jáñez-Martino, F.; Alaiz-Rodríguez, R.; González-Castro, V.; Fidalgo, E.; Alegre, E. Spam email classification based on cybersecurity potential risk using natural language processing. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2025, 310, 112939. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aljabri, M.; Mirza, S. Phishing Attacks Detection using Machine Learning and Deep Learning Models. In Proceedings of the 2022 7th International Conference on Data Science and Machine Learning Applications (CDMA); IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magdy, S.; Abouelseoud, Y.; Mikhail, M. Efficient spam and phishing emails filtering based on deep learning. Comput. Netw. 2022, 206, 108826. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Al-Ahmadi, S.; Alotaibi, A.; Alsaleh, O. PDGAN: Phishing Detection with Generative adversarial networks. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 42459–42468. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Patra, C.; Giri, D.; Nandi, S.; Das, A.K.; Alenazi, M.J. Phishing email detection using vector similarity search leveraging transformer-based word embedding. Comput. Electr. Eng. 2025, 124, 110403. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bountakas, P.; Xenakis, C. HELPFED: Hybrid Ensemble Learning PHIshing Email Detection. J. Netw. Comput. Appl. 2023, 210, 103545. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barraclough, P.A.; Fehringer, G.; Woodward, J. Intelligent cyber-phishing detection for online. Comput. Secur. 2021, 104, 102123. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, Q.; Cheng, M.; Wang, J.; Sun, B. LSTM Based Phishing Detection for Big Email Data. IEEE Trans. Big Data 2020, 8, 278–288. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alhogail, A.; Alsabih, A. Applying machine learning and natural language processing to detect phishing email. Comput. Secur. 2021, 110, 102414. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rawla, A.; Singh, S.; Dubey, M.; Dubey, P. Detection of Phishing Attacks in PhiUSIIL Dataset using Deep Learning. Procedia Comput. Sci. 2025, 259, 543–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nasreen, G.; Khan, M.M.; Younus, M.; Zafar, B.; Hanif, M.K. Email spam detection by deep learning models using novel feature selection technique and BERT. Egypt. Inform. J. 2024, 26, 100473. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Innab, N.; Osman, A.A.F.; Ataelfadiel, M.A.M.; Abu-Zanona, M.; Elzaghmouri, B.M.; Zawaideh, F.H.; Alawneh, M.F. Phishing Attacks Detection Using Ensemble Machine Learning Algorithms. Comput. Mater. Contin. 2024, 80, 1325–1345. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Medelbekov, M.; Nurtas, M.; Altaibek, A. Machine learning methods for phishing attacks. J. Probl. Comput. Sci. Inf. Technol. 2023, 1. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Palanichamy, N.; Murti, Y.S. Improving Phishing Email Detection Using the Hybrid Machine Learning Approach. J. Telecommun. Digit. Econ. 2023, 11, 120–142. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Muralidharan, T.; Nissim, N. Improving malicious email detection through novel designated deep-learning architectures utilizing entire email. Neural Netw. 2022, 157, 257–279. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nicholas, N.N.; Nirmalrani, V. An enhanced mechanism for detection of spam emails by deep learning technique with bio-inspired algorithm. e-Prime-Adv. Electr. Eng. Electron. Energy 2024, 8, 100504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Salahdine, F.; El Mrabet, Z.; Kaabouch, N. Phishing Attacks Detection A Machine Learning-Based Approach. In Proceedings of the 2021 IEEE 12th Annual Ubiquitous Computing, Electronics & Mobile Communication Conference (UEMCON); IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohamed, G.; Visumathi, J.; Mahdal, M.; Anand, J.; Elangovan, M. An Effective and Secure Mechanism for Phishing Attacks Using a Machine Learning Approach. Processes 2022, 10, 1356. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ojewumi, T.O.; Ogunleye, G.O.; Oguntunde, B.O.; Folorunsho, O.; Fashoto, S.G.; Ogbu, N. Performance evaluation of machine learning tools for detection of phishing attacks on web pages. Sci. Afr. 2022, 16, e01165. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ayo, F.E.; Ogundele, L.A.; Olakunle, S.; Awotunde, J.B.; Kasali, F.A. A hybrid correlation-based deep learning model for email spam classification using fuzzy inference system. Decis. Anal. J. 2024, 10, 100390. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alazaidah, R.; Al-Shaikh, A.; Al-Mousa, M.; Khafajah, H.; Samara, G.; Alzyoud, M.; Almatarneh, S. Website Phishing Detection Using Machine Learning Techniques. J. Stat. Appl. Probab. 2024, 13, 119–129. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alshingiti, Z.; Alaqel, R.; Al-Muhtadi, J.; Haq, Q.E.U.; Saleem, K.; Faheem, M.H. A Deep Learning-Based Phishing Detection System Using CNN, LSTM, and LSTM-CNN. Electronics 2023, 12, 232. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulraheem, R.; Odeh, A.; Al Fayoumi, M.; Keshta, I. Efficient Email phishing detection using Machine learning. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE 12th Annual Computing and Communication Workshop and Conference (CCWC); IEEE: Las Vegas, NV, USA, 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bansal, C.; Sidhu, B. Machine learning based hybrid approach for email spam detection. In Proceedings of the 2021 9th International Conference on Reliability, Infocom Technologies and Optimization (ICRITO); IEEE: Noida, India, 2021; pp. 1–4. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venugopal, I.V.S.; Bhaskari, L.; Seetaramanath, M. Detection of severity-based email spam messages using adaptive threshold driven clustering. Int. J. Adv. Comput. Sci. Appl. 2022, 13. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rashed, S. Ham and Spam Emails with Attachments, 2025. Available online: https://www.kaggle.com/datasets/rashedsarad/ham-and-spam-emails-with-attachments (accessed on 10 January 2026).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.