1. Introduction

With the rapid development of the Internet of Things (IoT), industrial internet, and digital engineering, state monitoring and decision-making analysis for complex physical systems have been transitioning from reliance on single data sources towards multi-source heterogeneous fusion. Multi-view learning, as a paradigm capable of integrating information from different sensors, modalities, or feature spaces (i.e., views), provides a theoretical foundation for building more comprehensive and accurate intelligent systems by exploring the consistency and complementarity among these views. This multi-source fusion technology has been widely applied in fields such as autonomous driving perception, medical image diagnosis, and complex industrial process control. The modern smart grid, for instance, serves as a typical and highly challenging scenario for multi-view data application: to cope with the systemic dynamics introduced by energy structure transformation, power grids are equipped with a massive number of sensing devices, including Phasor Measurement Units (PMUs), SCADA systems, meteorological monitors, and various distributed sensors [

1,

2].

These multi-source heterogeneous data collectively form a multi-dimensional panorama of the system’s operational state, theoretically providing unprecedented information redundancy for critical tasks like fault diagnosis and state estimation. For example, in power grid fault analysis, high-frequency dynamic phasors from PMUs can reveal transient characteristics, while steady-state measurements from SCADA reflect static snapshots. In broader image recognition tasks, color, texture, and shape features describe object attributes from different perspectives. However, achieving efficient and reliable multi-source data fusion, particularly at the decision level, presents a series of severe challenges in practical engineering applications.

The primary challenge lies in the dynamic uncertainty of data quality. In real-world open environments, the data quality generated by sensing devices often exhibits significant time-varying characteristics due to factors such as physical aging, communication environments, and external interference. Again, taking the power system as an example, sensors may experience drift due to aging or harsh weather, communication congestion can lead to data packet loss, and abrupt changes in system operating conditions (e.g., fault occurrence) can cause a sharp decline in the signal-to-noise ratio of partial views [

3,

4]. This implies that no single view can maintain high reliability throughout its entire lifecycle. Traditional static fusion methods, such as simple averaging or early fusion, often implicitly assume that all views are equally important or maintain constant quality. When confronted with isolated strong noise or a single-view failure, these methods are highly susceptible to contamination, leading to a sharp decline in overall decision-making performance [

5].

Furthermore, existing dynamic fusion methods struggle to balance model complexity, interpretability, and robustness [

6]. Methods based on attention mechanisms [

7], while capable of adaptively allocating weights, often involve a black-box weight generation process lacking clear physical or statistical significance. This makes it difficult to meet the stringent demands for decision transparency in high-stakes scenarios like power grid fault handling or medical diagnosis. Advanced frameworks based on evidence theory (e.g., Dempster–Shafer theory) [

8] or derived from generalization bounds [

9], while theoretically sound, often introduce complex evidence modeling processes or additional auxiliary networks, significantly increasing computational overhead and training instability, thus limiting their deployment in real-time systems.

To address the aforementioned challenges, this paper proposes a Consensus-Aware Residual Gating (CARG) mechanism, a decision-level algorithm designed for dynamic quality assessment and multi-feature fusion. The core design philosophy of CARG stems from a key insight: in multi-view systems, consistent predictions shared by the majority of views (i.e., group consensus) typically represent reliable signals, whereas isolated, inconsistent predictions are highly likely to be noise or anomalies. However, such isolated discrepancies may also harbor truly valuable complementary information capable of correcting group biases. Consequently, an ideal fusion strategy must possess two capabilities: first, prioritizing and reinforcing group consensus to suppress isolated noise interference; and second, prudently evaluating and selectively amplifying complementary information verified to be valuable (uniqueness).

Based on this philosophy, CARG constructs a dynamic weight generation module that relies entirely on current sample predictions, requiring no additional parameter learning. Specifically, for each sample under analysis, CARG quantitatively assesses the quality of each data view (feature source) from three interpretable dimensions: (1) Confidence: measures the internal certainty of a single view regarding its own prediction. A high-confidence prediction typically indicates that the view’s features possess strong discriminative power for the given sample. (2) Consensus: measures the group consistency between a single view’s prediction and those of all other views. High consensus indicates that the view’s judgment is widely supported by other feature views, suggesting higher reliability. (3) Uniqueness: measures the informational divergence or complementarity of a single view relative to the average prediction of others. To avoid rewarding meaningless noise fluctuations, CARG employs threshold filtering to focus solely on significant discrepancies.

Subsequently, CARG employs a multiplicative gating structure to integrate these three orthogonal quality metrics into a sample-level gating value. This structure naturally embeds a consensus-first inductive bias: a view’s final weight depends simultaneously on its confidence level, its alignment with the group, and its provision of valuable new information. Even if a view exhibits extremely high self-confidence, its weight will be significantly suppressed if it contradicts the conclusions of all other views (low consensus), effectively preventing a single faulty view from hijacking the entire decision system. Conversely, when a view provides a high-confidence prediction while its uniqueness is verified as beneficial, the introduction of an exponential term appropriately amplifies its contribution. Finally, the fusion weights are obtained via Softmax normalization with logarithmic transformation and temperature scaling, followed by a weighted summation of the output logits from each view.

The main contributions of this paper are summarized as follows:

We propose CARG, a novel and lightweight decision-level fusion framework tailored for multi-source data. The method eliminates the need for complex evidential modeling or additional weight predictors, ensuring ease of implementation and deployment.

We design a three-dimensional dynamic quality assessment system comprising Confidence, Consensus, and Uniqueness. Through multiplicative gating, this system achieves robust suppression of isolated noise and prudent utilization of valuable complementary information, providing high interpretability for fusion decisions.

To verify the effectiveness and generalization capability of the proposed method, we conduct systematic experimental evaluations on multiple public multi-view learning benchmark datasets. The results demonstrate that CARG exhibits significant advantages in classification accuracy, robustness, and interpretability compared to various baseline fusion methods.

2. Related Works

2.1. Multi-View Learning and Fusion

Multi-view learning (MVL) is dedicated to effectively utilizing data acquired from diverse sources or perspectives (i.e., views) regarding the same object [

10]. In applications such as power system situational awareness, these views correspond to different types of sensor data (e.g., PMU, SCADA) or multi-modal information (e.g., time-series measurements, network topology). The fundamental premise of MVL is the existence of consistency and complementarity among views [

11]. Effectively leveraging these two characteristics enables the construction of learning models that are more robust and accurate than any single-view counterpart.

As a pivotal technique for realizing MVL objectives, data fusion is generally categorized into three levels based on the abstraction hierarchy where information integration occurs: data-level, feature-level, and decision-level fusion. Among these, feature-level and decision-level fusion have garnered significant attention due to their flexibility and capability in handling heterogeneous data. Based on the specific stage where fusion takes place, mainstream strategies can be further refined into early fusion, late fusion, and hybrid fusion.

Early fusion, also known as feature-level fusion, integrates features from various views at the initial stage of model training, with feature concatenation being the most prevalent approach [

12]. While this method can directly capture low-level correlations among views, its drawbacks are pronounced: it necessitates strict alignment of data across all views, is prone to the curse of dimensionality, and is highly sensitive to noise or missingness in any single view, as quality issues can directly contaminate the entire feature space.

Late fusion, or decision-level fusion, adopts a divide-and-conquer strategy. It involves first training base models independently for each view and subsequently aggregating their predictions (e.g., logits or probabilities) at the decision layer [

13]. Common aggregation methods include averaging and voting. The modular design of late fusion enables effective handling of heterogeneous and asynchronous data and possesses inherent robustness to view missingness. However, simple aggregation methods (such as averaging) implicitly rely on the overly strong assumption that all views are of equal importance, which often does not hold in real-world scenarios. Consequently, how to dynamically assign weights to each view has become a research focal point. The CARG method proposed in this paper represents an advanced dynamic late fusion approach.

Hybrid fusion strategies attempt to facilitate information interaction at intermediate layers of the model, aiming to combine the merits of both early and late fusion. For instance, deep interaction of feature representations can be achieved through cross-modal attention mechanisms. Theoretically, such methods can more comprehensively mine complex associations among views; however, they are typically accompanied by higher model complexity and computational costs, and often suffer from relatively weak interpretability regarding the fusion process.

2.2. Dynamic Decision-Level Fusion Methods

To address the limitations of simple late fusion, the academic community has proposed various dynamic weighting methods aiming to assign adaptive weights to different views in an instance-specific manner.

The first category comprises confidence-based weighting. This represents the most intuitive approach to dynamic weighting, premised on the notion that models exhibiting higher confidence in their predictions should be assigned greater weight. Confidence is typically quantified by the maximum value of the predicted probability distribution (max-probability) [

14] or by normalized entropy. While simple and effective, this method suffers from a critical drawback: it cannot handle scenarios where a model is confidently incorrect. For a view contaminated by strong noise due to sensor malfunction, the corresponding model might output an erroneous prediction with extremely high confidence. In such cases, confidence-based weighting counterproductively amplifies the negative impact of the noise [

15].

The second category involves attention-based fusion. Attention mechanisms are widely applied in multi-view fusion, constructing an attention network to learn a weight distribution dependent on all view inputs, thereby dynamically focusing on the most critical views for the current sample. The primary advantages of attention mechanisms lie in their powerful fitting capabilities and end-to-end learning paradigms [

16]. However, their downsides are equally prominent: the weight generation process often operates as a black box lacking explicit physical or statistical significance, which fails to meet the transparency requirements of safety-critical scenarios like power systems. Furthermore, weight learning can become unstable when data are limited or when significant conflicts exist between views.

The third category consists of methods based on consistency and evidence theory. These approaches model the relationships between views from a deeper theoretical perspective [

17]. The consistency principle is widely utilized, operating on the fundamental assumption that a consistent conclusion derived from multiple independent sources is more reliable than that from a single source [

18]. Going further, evidence theory—particularly the Dempster–Shafer Theory (DST)—provides a rigorous mathematical framework for handling uncertainty and conflicting information [

19]. Recent works, such as Trusted Multi-view Classification (TMC), integrate DST with deep learning to explicitly model uncertainty by assigning evidence to predictions and rationally adjudicating conflicts. Additionally, methods like Quality-aware Multi-view Fusion (QMF) approach the problem from the perspective of generalization bounds, training additional quality assessment networks to predict weights. While theoretically more complete, these methods often require complex evidential function modeling or the introduction of auxiliary networks. This results in high implementation complexity and computational overhead, limiting their application in resource-constrained or rapid-response scenarios.

In summary, existing dynamic decision fusion methods present a trade-off: simple confidence-based methods lack robustness against complex noise; complex attention-based methods lack interpretability; and methods based on rigorous frameworks like evidence theory suffer from excessive implementation and computational costs. This reveals a clear research gap: there is an urgent need for a decision fusion mechanism that is simultaneously lightweight, highly interpretable, and robust. The CARG method proposed in this paper aims to bridge this gap. By designing interpretable quality metrics derived directly from the sample predictions (Confidence, Consensus, and Uniqueness) and combining them via a structured gating mechanism, CARG seeks to achieve a decision fusion process that requires no additional parameter learning, and is computationally efficient, intuitively interpretable, and robust against isolated noise.

2.3. Distinction from Existing Frameworks

While CARG shares the goal of robust fusion with evidence-based methods like TMC and ETMC, it fundamentally differs in its underlying assumptions and operational mechanism. Evidential methods assume that view uncertainty must be explicitly learned as parameters of a Dirichlet distribution via specialized objectives (e.g., EDL loss), often conflating “low quality” with “high conflict” into a single reduced evidence score. In contrast, CARG operates on the relative geometric relationships of standard posterior probabilities, requiring no modification to the base classifiers’ training paradigm (plug-and-play). Crucially, distinct from “black-box” attention mechanisms or implicit evidential modeling, CARG employs a structured gating mechanism to explicitly decouple conflict into two actionable signals: divergence from group consensus is suppressed as noise via the Consensus metric, while statistically significant divergence is rewarded as complementary information via the Uniqueness metric. This explicit separation allows CARG to achieve a more refined balance between robustness and information gain without relying on auxiliary networks or heavy parametrization.

3. Methods

Confronted with ubiquitous challenges in multi-source data—such as sensor faults, communication packet loss, and dynamic variations in Signal-to-Noise Ratio (SNR)—an ideal decision fusion algorithm must possess the capability to robustly suppress isolated noise while prudently utilizing valuable complementary information. The design of CARG centers precisely on this core objective. Its fundamental rationale is to eschew reliance on complex weight prediction networks that require additional learning; instead, it constructs a self-assessing dynamic weighting framework derived entirely from the prediction results of each view for the current sample.

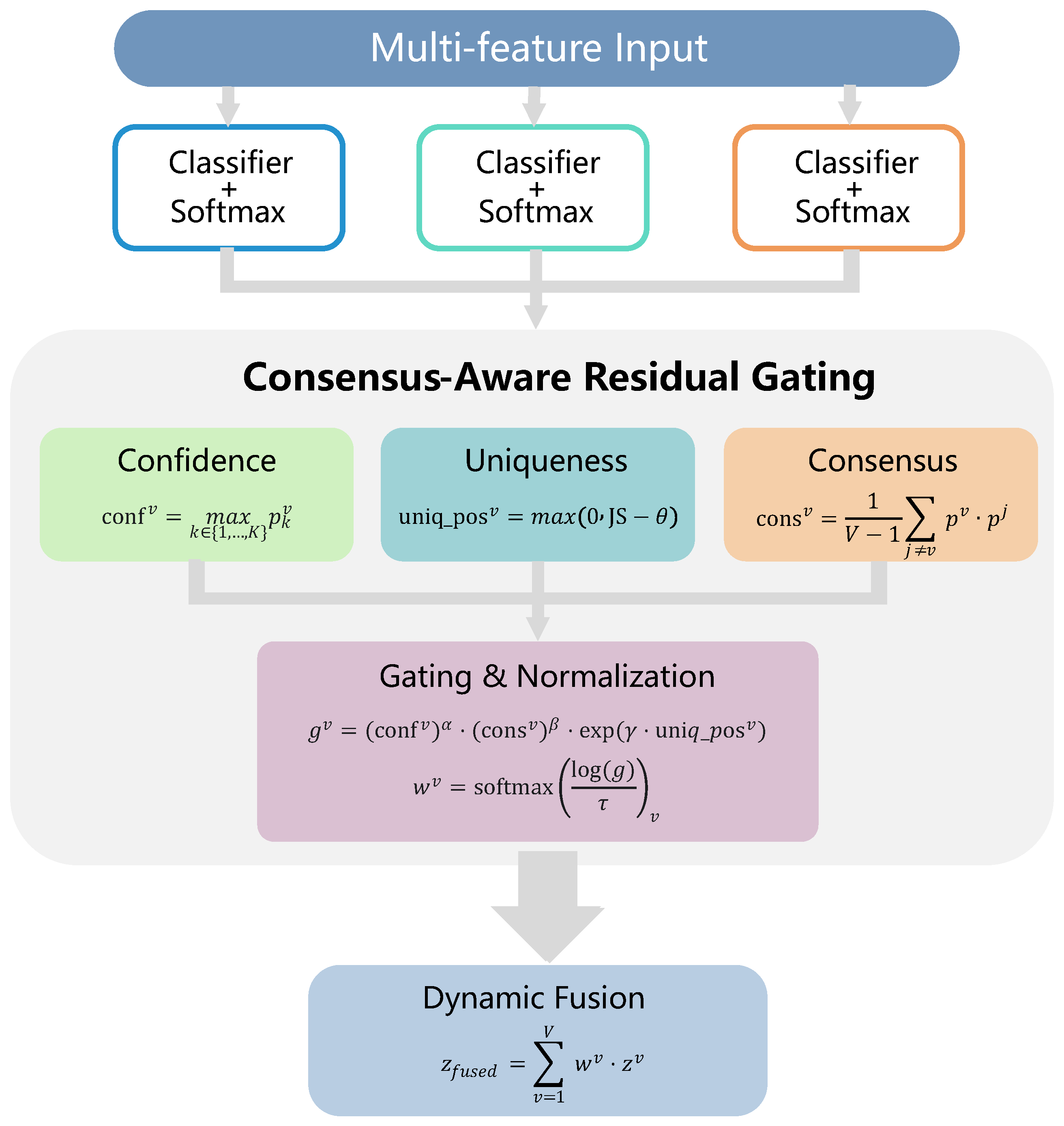

The architecture of the CARG model is illustrated in

Figure 1. Given an input sample, the process begins by obtaining preliminary prediction results (logits) for each view through

V parallel, view-specific independent classifiers. Subsequently, the core of CARG—the Dynamic Quality Assessment module—calculates three interpretable scalar metrics for each view’s prediction: Confidence, Consensus, and Uniqueness. These metrics characterize the decision quality of the respective view for the current sample from distinct dimensions. Finally, the Consensus-Aware Residual Gating module synthesizes these metrics through a meticulously designed multiplicative gating structure. Following a Log-Softmax transformation, it generates a set of normalized, sample-level fusion weights. These weights are ultimately utilized to perform a weighted summation of the logits from each view, yielding the final fused prediction. The entire process is end-to-end differentiable, allowing for joint optimization alongside the base classifiers.

The core advantage of this design lies in its embedded structural inductive bias: a strategy of consensus-first, prudent innovation. By establishing Consensus as a critical multiplicative factor within the gating mechanism, CARG naturally tends to suppress isolated views that contradict the group opinion, thereby effectively resisting interference from single-point failures or strong noise. Simultaneously, by applying an exponential reward to threshold-filtered Uniqueness information, CARG retains the capability to amplify—when necessary—truly valuable complementary information capable of correcting group biases, thus achieving a unification of robustness and flexibility.

3.1. Problem Definition

Consider a

K-class classification problem with

V distinct data views

. Let

represent the feature vector from the

v-th view, where its dimension is

. Each view

v is associated with an independent base classifier

, which consists of a neural network parameterized by

. For an input feature

, the classifier outputs a

K-dimensional logits vector

. This logits vector can be converted into the corresponding posterior probability distribution

over the

K categories using the Softmax function:

represents the probability that the

v-th view predicts the sample to belong to class

k. The goal of CARG is to design a fusion function that computes a fused logits vector

from all the logits

or probabilities

of the views and makes the final classification prediction.

3.2. Dynamic Quality Assessment

The core of CARG is its dynamic, real-time assessment of the decision quality of each view for each sample. The assessment system consists of three complementary metrics. Confidence aims to quantify the internal certainty or self-confidence of a view in its own prediction. Intuitively, if the prediction probability distribution of a view is highly concentrated on a certain class, it suggests that the features of this view have strong discriminative power for this sample, and its prediction is relatively more reliable.

We use maximum probability as the confidence measure:

This value lies between

and 1, with higher values indicating greater confidence. An alternative definition is based on the normalized Shannon entropy. Entropy measures the uncertainty of a probability distribution, and lower entropy implies less uncertainty and higher confidence. Its formula is as follows:

To map it to the range

and interpret it as confidence, we normalize and invert as follows:

where

is the maximum entropy of a uniform distribution. Compared to max probability, the entropy-based definition more comprehensively considers the shape of the entire probability distribution. In this study, we adopt the computationally more efficient max probability definition. We find a clear limitation in the confidence metric: the model may confidently make mistakes, such as when the input is severely noisy. To address this issue, we introduce consensus degree to measure the agreement between a single view’s prediction and the predictions of all other views. This directly reflects the consensus-aware concept. The basic assumption is that conclusions with consensus from multiple independent sources are more reliable than any isolated conclusions. We use the dot product between probability distributions to measure the similarity between the predictions of two views, as it is simple to compute and effectively reflects the overlap between the distributions. The consensus degree for view v

is defined as the average dot product between its probability distribution

and the probability distributions of all other views

(

):

The consensus degree ranges is in the range of

. When view

v’s prediction strongly agrees with the other views, the value

approaches 1; conversely, if the prediction significantly diverges from others, the value decreases. This metric provides strong support for identifying and suppressing potentially isolated abnormal views.

While emphasizing consensus, a robust fusion system must also be able to recognize and leverage truly valuable complementary information. A view’s prediction may disagree with the group, not because it is noisy, but because it captures crucial information overlooked by the other views, which could correct the group’s erroneous judgment. The uniqueness metric is designed to quantify this beneficial difference. To measure the difference between view

v and the rest of the views, we first compute the average probability distribution

of all views excluding

v:

Next, we use Jensen–Shannon Divergence (JSD) to measure the difference between

and

. JSD is a symmetric, smoothed version of Kullback–Leibler (KL) divergence, with a range of

, and is well-suited for measuring the distance between two probability distributions

P and

Q. The JSD formula is as follows:

Therefore, the original uniqueness score

for view

v is as follows:

However, directly rewarding all differences is dangerous, as it may amplify meaningless random noise. To address this, we introduce a tunable threshold

to retain only significant differences above the threshold, filtering out small fluctuations likely caused by noise. The processed effective uniqueness

is as follows:

This simple yet effective design embodies the core principle of CARG: only consider rewarding a view if it provides sufficiently novel and distinct information.

3.3. Consensus-Aware Residual Gating

After computing the three quality metrics, the next step is how to combine them effectively into the final fusion weight. CARG uses a novel multiplicative gating structure. We combine the three quality metrics of each view

v into a raw gating value:

where

,

, and

are three non-negative hyperparameters controlling the relative importance of confidence, consensus, and uniqueness. The multiplication ensures a logical AND relationship between these metrics. Specifically, consensus plays a gatekeeping role: even if a view has high confidence, if it severely disagrees with the group, the entire gating value will be pulled toward zero, thus effectively suppressing its weight in the final fusion. This is a structured realization of the consensus-first strategy. The use of an exponential function for effective uniqueness is to give truly valuable complementary information a non-linear, strong reward. When Effective Uniqueness

is zero, it has no effect; when

increases, its contribution grows exponentially with the adjustment of

. This carefully magnifies beneficial new information. By adjusting

,

, and

, the fusion strategy can be customized based on the specific characteristics of the task.

The raw gating value is normalized to a set of weights summing to 1. We first take the logarithm of

to improve numerical stability and turn the multiplicative relationship into an additive one in log space. Then, a temperature parameter

is introduced, and the final per-sample weight

is obtained through the Softmax function:

The final fused logits are obtained by weighted summation of the logits from each view:

The fused probability distribution is obtained by

.

3.4. Training Objective

To enable the entire model to learn end-to-end, we design the following loss functions.

The primary fusion loss is the main source of supervised learning, optimizing the prediction performance of the entire fusion framework. We use the standard cross-entropy loss function:

where

y is the one-hot true label of the sample.

The auxiliary view loss ensures that each independent base classifier learns meaningful feature representations and makes reasonable predictions, which is a prerequisite for the validity of the quality assessment metrics. For each view’s output, we also compute a cross-entropy loss and average them as an auxiliary loss:

This auxiliary loss plays a deep supervision and regularization role, preventing the base classifiers from degrading.

An optional calibration loss can be introduced in some applications where we want the mean fusion weights to align with macro quality metrics, such as the average confidence, enhancing the model’s interpretability and calibration. This can be carried out by introducing a lightweight Mean Squared Error (MSE) loss:

where

is the confidence metric after normalization.

The total loss is the weighted sum of the above components:

, and

are hyperparameters controlling the importance of corresponding loss component.

4. Experiments

4.1. Experimental Setup

We conduct experiments on seven widely used multi-view classification benchmark datasets, which encompass diverse sample sizes, category counts, numbers of views, and feature types, thereby enabling a comprehensive evaluation of the algorithm’s performance and generalization capability. Detailed statistics for each dataset are presented in

Table 1, with specific descriptions provided below: (1) PIE: A facial image dataset containing 68 different individuals. It consists of three views extracted from images captured under varying poses, illumination conditions, and expressions. The dataset comprises a total of 680 samples, with the task being face recognition. (2) Scene: A scene classification dataset containing 4485 images drawn from 15 scene categories. This dataset provides three views representing different feature levels, such as color, texture, and layout of the images. (3) Leaves: A plant leaf classification dataset containing 1600 samples from 100 different species. Each sample is provided with three views, corresponding to features extracted from leaf shape, texture, and margin information. (4) NUS-WIDE: A subset of a large-scale real-world web image dataset originating from Flickr. The version used in our experiments contains 2400 samples across 12 categories. Each sample is described by five views of features, including color histograms, texture, and edge direction. (5) MSRC: The Microsoft Research Cambridge Object Recognition Image Database (Version 1), containing 210 images across 7 categories (e.g., cows, airplanes, bicycles). Each image provides five views of features covering color, texture, and spatial structure information. (6) Fashion-MV: A multi-view dataset constructed based on Fashion-MNIST. It contains 1000 samples across 10 fashion product categories. Three views are generated using three distinct image processing methods, with each view having a dimensionality of 784. (7) Caltech: A widely used benchmark dataset for object recognition. The version employed in this study comprises 2386 samples across 20 categories and provides 6 views generated via various feature extraction algorithms (e.g., LBP, GIST, SIFT).

To comprehensively validate the performance of CARG, we select several representative late fusion methods and multiple state-of-the-art (SOTA) algorithms proposed in recent years as comparative baselines. These methods cover advanced concepts such as evidence theory and uncertainty modeling: (1) TMC [

8]: Trusted Multi-view Classification: This method integrates deep learning with the Dempster–Shafer Theory (DST) of evidence. It assigns evidence to the predictions of each view and utilizes evidence combination rules to fuse conflicting information, thereby explicitly modeling uncertainty. (2) ETMC [

20]: Enhanced Trusted Multi-view Classification: As an improved version of TMC, this method optimizes the generation and combination of evidence, aiming to further enhance fusion performance and robustness in complex scenarios. (3) DUANets [

21] (Deep Uncertainty-Aware Networks): This method separately models aleatoric uncertainty and epistemic uncertainty, utilizing these uncertainty metrics to guide the dynamic fusion of multi-view information. (4) ECML [

22] (Evidential Contrastive Multi-view Learning): This method innovatively combines evidential deep learning with contrastive learning. It aims to learn high-quality feature representations capable of both capturing inter-view consistency and quantifying prediction uncertainty, thereby serving downstream fusion tasks. (5) TMNR [

23] (Trusted Multi-view Noise Refinement): Focusing on identifying and mitigating noise in multi-view data, this method constructs a trustworthiness assessment mechanism to reduce the negative impact of noisy views on the overall decision. It represents an advanced approach oriented towards noise robustness.

To evaluate the classification performance of all methods comprehensively and fairly, we employ classification accuracy (ACC) and F1-score as the evaluation metrics in our experiments. Our experiments are conducted on the PyTorch framework (2.5.1) with an Nvidia RTX 2080 Ti GPU. For all datasets, followed by [

24], we use 80% of the samples for training, and 20% for testing. And the average accuracy and standard deviation with five random seeds is reported. The training epoch is set as 500. The learning rate is selected in the range of

. The hyperparameters

,

,

,

,

, and

are set as 1.0, 1,0, 2.0, 0.02, 0.6 and 1.0 respectively. And Adam is used as the optimizer.

4.2. Comparison Results

To validate the effectiveness of the CARG algorithm, we conduct a comprehensive performance comparison against five state-of-the-art (SOTA) multi-view fusion methods across seven benchmark datasets. Drawing from the experimental results presented in

Table 2, we can derive the key observations and analyses below.

First, the proposed CARG method achieved the highest classification accuracy across all seven test datasets, providing compelling evidence of its superior performance and robust generalization capabilities. Whether applied to datasets with fewer views (e.g., PIE, Scene, Leaves) or those with a larger number of views (e.g., NUS-WIDE, MSRC, Caltech), CARG consistently outperformed all comparative advanced methods.

Second, the advantage is significantly pronounced on complex datasets. CARG’s superiority is particularly evident when handling challenging real-world datasets. For instance, on the Scene dataset, CARG achieved an accuracy of 77.37%, surpassing the second-best method, ECML (73.20%), by over 4.1 percentage points, and demonstrating a substantial performance lead of nearly 10% to 26% over other methods such as TMC and DUANets. Similarly, on the NUS-WIDE dataset, which is characterized by high view heterogeneity and rich semantic information, CARG attained an accuracy of 43.46%, significantly outperforming the runner-up ECML (41.21%) and far exceeding other baselines. These results suggest that CARG’s consensus-first mechanism effectively addresses issues of uneven view quality and severe noise interference inherent in real-world scenarios, filtering out unreliable predictions by reinforcing group consistency.

Next, in comparison with evidence theory-based methods, TMC and its enhanced version, ETMC, serve as formidable baselines that manage inter-view conflicts and uncertainty through complex evidential modeling. Although ETMC performed exceptionally well on datasets like Leaves (98.44%), CARG still maintained a slight edge with an accuracy of 99.12%. This indicates that the dynamic quality assessment system employed by CARG—comprising Confidence, Consensus, and Uniqueness—while more lightweight in implementation than evidence theory, achieves or even surpasses the latter’s capability in discriminating information quality and resolving conflicts.

Compared with the latest methods, ECML leverages contrastive learning to acquire high-quality representations, showing strong performance across multiple datasets, while TMNR focuses on identifying noisy views. Nevertheless, CARG consistently surpassed both across all datasets. Notably, on the Caltech dataset, CARG (95.94%) achieved an improvement of over 3.5 percentage points compared to ECML (92.30%) and TMNR (92.38%). This fully underscores the unique superiority of CARG’s design philosophy. It not only implicitly identifies potential noisy views via consensus but also retains the ability to amplify beneficial complementary information through its uniqueness gating (a feature achieved only indirectly by representation learning methods like ECML). Consequently, CARG strikes a superior balance between robustness and information utilization efficiency.

In summary, the experimental results demonstrate that CARG not only outperforms a variety of existing advanced multi-view fusion methods in terms of performance but also exhibits strong adaptability and stability across varying data characteristics, thereby validating its value as a novel and efficient fusion framework.

4.3. Ablation Study

To investigate the practical contribution of each core component within the CARG framework, we design a set of ablation experiments. Specifically, our objective is to validate the necessity of the three dynamic quality assessment metrics in the final fusion decision-making process.

Based on the experimental results presented in

Table 3, we can draw the following conclusions: First, the Confidence module is effective. Upon removing the Confidence module, both the accuracy and F1-score of the model exhibited a decline. This indicates that the confidence metric, which gauges the internal certainty of a single view, indeed provides beneficial auxiliary information for weight assignment. It facilitates the model’s inclination towards views that are more decisive in their judgment for the current sample, thereby playing an effective role in fine-tuning the fusion process.

Second, the Consensus module is equally effective. Compared to the removal of the Confidence module, the exclusion of the Consensus module resulted in a distinct degradation in performance, with both accuracy and F1-score decreasing to varying degrees. This result corroborates the validity of the consensus-first principle. As a pivotal metric for measuring inter-view consistency, Consensus serves as the core safeguard enabling CARG to effectively suppress isolated noise and withstand single-view failures. Without this module, the model loses the ability to effectively identify and dampen outlier predictions that contradict group opinion, making it more susceptible to being misled by low-quality views and consequently leading to a deterioration in overall decision-making performance.

Third, the Uniqueness module plays a critical role in unlocking the peak performance of the fusion framework. As evidenced by the experimental data, the removal of the Uniqueness metric (w/o Uniq) precipitated the most severe decline in performance among all ablation settings, with accuracy plummeting to 75.26% and the F1-score to 74.42%. While Consensus ensures the system’s stability by filtering noise, the Uniqueness metric is responsible for capturing novel, non-redundant features that may be held by only a minority of views but are essential for correcting group biases. Without this module, the fusion strategy risks degenerating into a conservative majority voting scheme, losing the capability to leverage specific, high-value distinct information required to accurately classify complex or ambiguous samples.

4.4. Calibration Analysis

Table 4 illustrates the performance differences between individual base classifiers (View 0–2) and the final calibrated fusion results on the Leaves and PIE datasets. A key observation is the significant fluctuation in single-view quality. For instance, on the Leaves dataset, View 1 exhibited an extremely low accuracy of only 46.88%, acting as a significant noise source, whereas View 2 performed relatively well (85.00%). Despite such extreme performance imbalance and the presence of a weak learner, the calibrated (i.e., CARG fusion) result achieved a remarkable accuracy of 99.12%. This represents an improvement of over 14 percentage points compared to the best-performing single view. Similarly, on the PIE dataset, the fused result (94.71%) significantly outperformed the best single view (79.63% for View 2). These results empirically demonstrate that CARG does not rely on the assumption that all base classifiers must be high-performing or perfectly calibrated. Instead, through its dynamic quality assessment mechanism, CARG effectively suppresses interference from unreliable views (such as View 1 in Leaves) and synergistically integrates local information from other views to refine the final decision, thereby achieving a calibration effect at the decision level.

4.5. Parameter Sensitivity Analysis

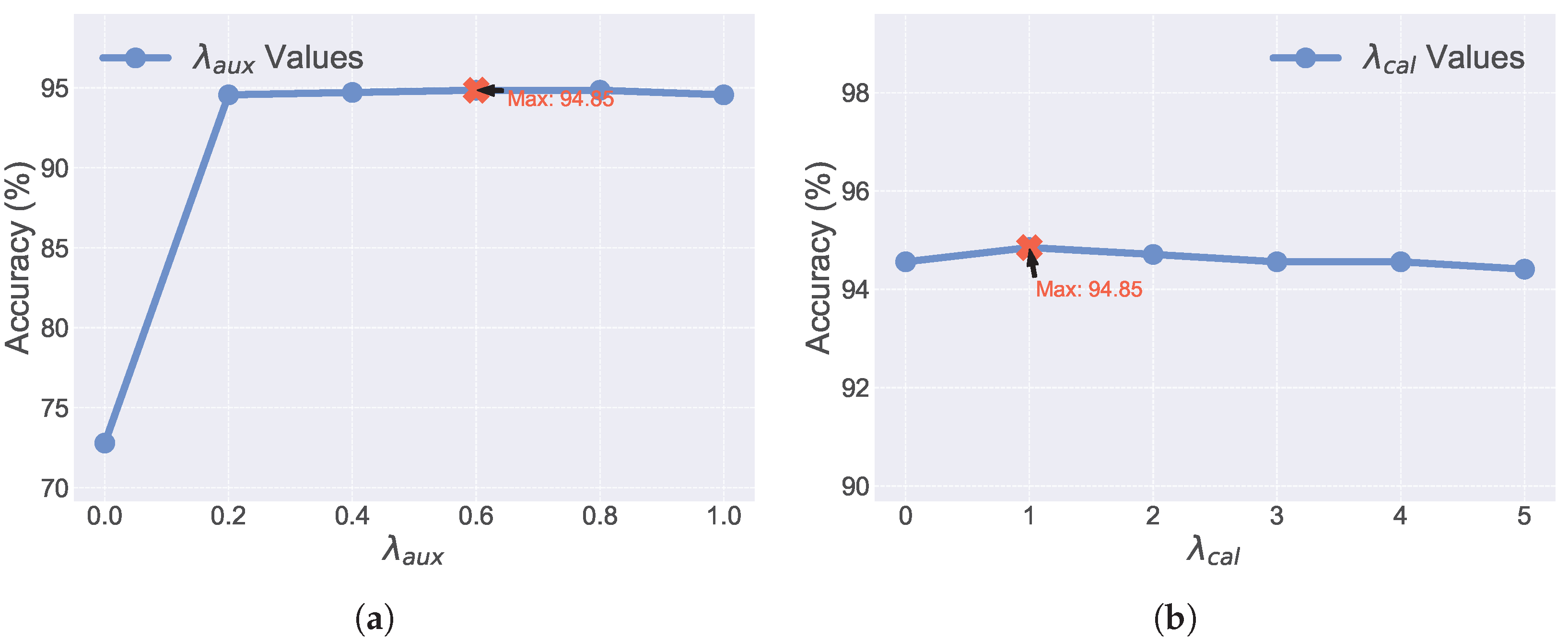

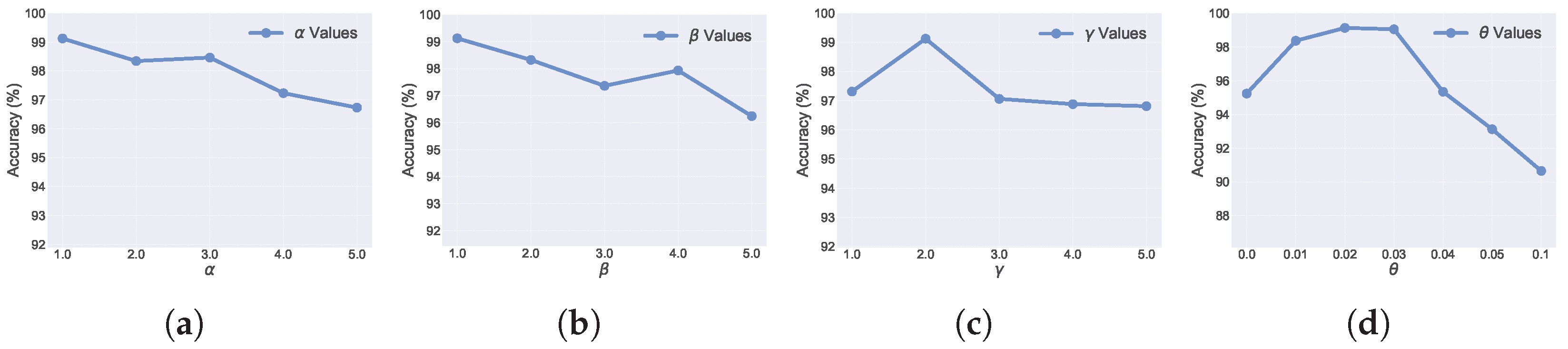

To assess the CARG model’s stability and robustness, we conduct a parameter sensitivity analysis on PIE and Leaves. From

Figure 2 and

Figure 3, the following observations emerge:

Firstly, the following is observed for : Model accuracy initially rises, stabilizes, then slightly declines. Optimal performance (94.05% accuracy) is observed around , with stability extending to 0.8. Excessively large may overemphasize individual view performance, diminishing fusion benefits. Overall, CARG demonstrates good robustness to variations within a reasonable range, ensuring stable performance and practical deployability.

Secondly, the following is observed for : Model accuracy increases with , peaking around (94.85% accuracy) and remaining high and stable up to . This indicates that calibration loss effectively enhances model interpretability and alignment. Overly large can also lead to minor accuracy drops, suggesting the importance of balanced parameter tuning.

Third, we validate that our settings for the values of , , , and are correct. It is noteworthy that the best performance is often achieved when and , which suggests that distinctiveness plays a more significant role in discriminating between different types of information. Furthermore, experiments conducted on not only demonstrate its effectiveness but also confirm the rationality of its value setting.

4.6. Efficiency Analysis

In addition to classification accuracy, computational efficiency is a critical factor determining whether a model can be practically deployed in resource-constrained IoT or industrial scenarios.

Table 5 presents a comparative analysis of the model parameter count (#Params) and inference time for various methods on the Leaves dataset. CARG demonstrates a significant advantage in terms of model complexity, requiring only 20 K parameters. This presents a stark contrast to TMNR, which requires up to 48 M parameters, and is also considerably lighter than ETMC (88K). This lightweight characteristic directly translates into superior inference speed, with CARG achieving the fastest inference time of 0.03544 s, outperforming both ETMC (0.04234 s) and TMNR (0.04066 s). These results validate the high efficiency of our design philosophy: by deriving fusion weights directly from the statistical properties of predictions (confidence, consensus, uniqueness), rather than relying on heavy auxiliary networks or complex evidential modules, CARG achieves minimal computational overhead while maintaining high performance, making it particularly suitable for time-sensitive application scenarios.

4.7. Feature Visualization

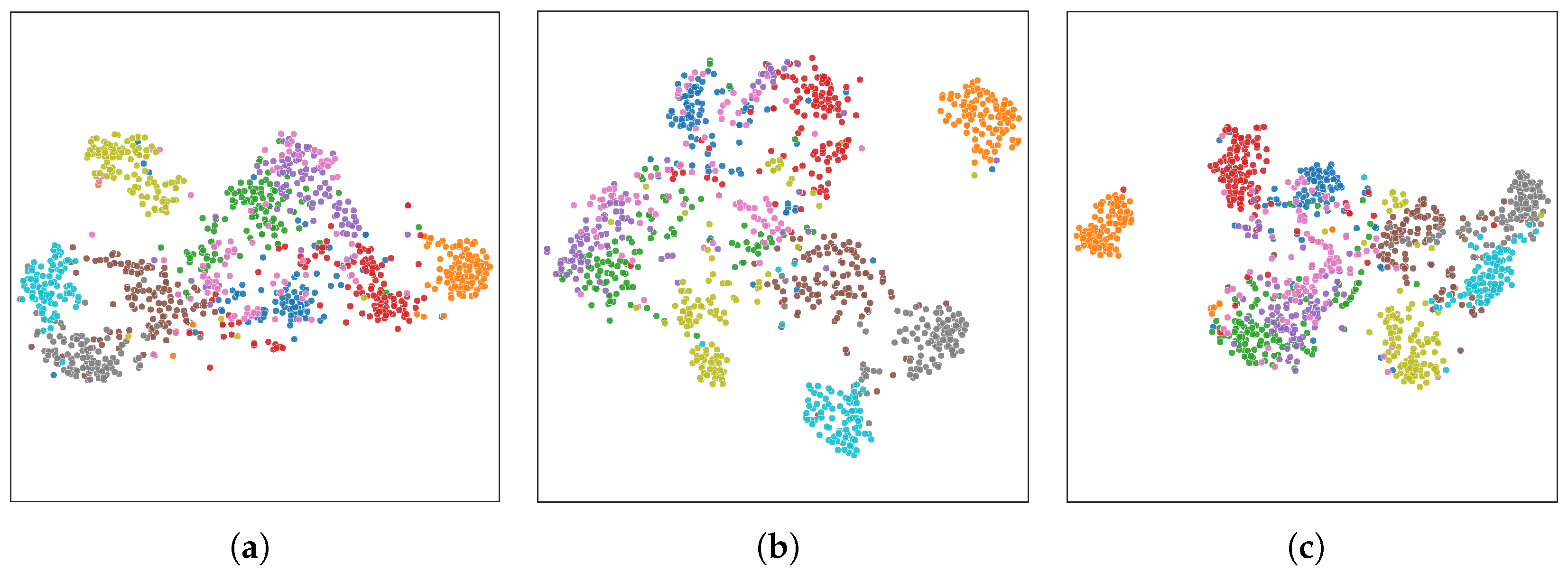

We employ the t-distributed Stochastic Neighbor Embedding (t-SNE) dimensionality reduction technique to analyze the feature representations learned by the model on the Fashion dataset. Specifically, we extract the high-dimensional feature vectors output by the three view-specific classifiers within the CARG framework (situated prior to the logits layer) and projected them onto a two-dimensional space for visualization. In the resulting plots, each point represents an individual sample, with the color denoting its ground-truth class label.

Upon examining the three visualization subplots in

Figure 4, we arrive at the following observations: First, from a global perspective, the feature representations of all three views exhibit a distinct clustering structure within the two-dimensional space. Samples belonging to the same class are largely aggregated to form relatively independent clusters, while a distinct separation is maintained between clusters of different classes. This provides compelling evidence that each base classifier within the CARG framework has successfully learned highly discriminative feature representations, enabling effective differentiation among samples of different classes. This serves as the fundamental basis ensuring the superior performance of the entire fusion framework.

Second, regarding the relationship between feature distribution and CARG mechanisms, when a sample point is situated deeply within a high-density, homogeneous cluster in the feature space of a specific view, the classifier for that view is highly likely to yield a correct prediction with high confidence. If such a sample is mapped to the core region of the corresponding class across multiple views, the predictions of these views will exhibit high consistency, thereby garnering a high consensus score. Conversely, for hard samples located at cluster boundaries or within overlapping regions, different views may yield divergent predictions. In such scenarios, CARG’s consensus mechanism effectively identifies this divergence, while the uniqueness module prudently evaluates whether a specific view offers pivotal information capable of resolving the ambiguity.