Abstract

Depression represents a major global health challenge, yet traditional clinical diagnosis faces limitations, including high costs, limited coverage, and low patient willingness. Social media platforms provide new opportunities for early depression screening through user-generated content. However, existing methods often lack systematic integration of clinical knowledge and fail to leverage multi-modal information comprehensively. We propose a DSM-5-guided methodology that systematically maps clinical diagnostic criteria to computable social media features across three modalities: textual semantics (BERT-based deep semantic extraction), behavioral patterns (temporal activity analysis), and topic distributions (LDA-based cognitive bias identification). We design a hierarchical architecture integrating BERT, Bi-LSTM, hierarchical attention, and multi-task learning to capture both character-level and post-level importance while jointly optimizing depression classification, symptom recognition, and severity assessment. Experiments on the WU3D dataset (32,570 users, 2.19 million posts) demonstrate that our model achieves 91.8% F1-score, significantly outperforming baseline methods (BERT: 85.6%, TextCNN: 78.6%, and SVM: 72.1%) and large language models (GPT-4 few-shot: 86.9%). Ablation studies confirm that each component contributes meaningfully with synergistic effects. The model provides interpretable predictions through attention visualization and outputs fine-grained symptom assessments aligned with DSM-5 criteria. With low computational cost (~50 ms inference time), local deployability, and superior privacy protection, our approach offers significant practical value for large-scale mental health screening applications. This work demonstrates that domain-specialized methods with explicit clinical knowledge integration remain highly competitive in the era of general-purpose large language models.

1. Introduction

Depression is one of the most prevalent mental health disorders worldwide, affecting over 380 million people globally according to the World Health Organization (WHO) [1]. In China alone, more than 54 million individuals suffer from depression, yet only 30% receive effective treatment due to diagnostic delays, insufficient medical resources, and social stigma. Traditional clinical diagnosis relies primarily on face-to-face interviews and psychological assessments (e.g., PHQ-9 [2] and HAMD scales), which suffer from high costs, limited accessibility, and delayed intervention—patients typically seek help only after symptoms have significantly worsened, missing critical early intervention windows.

Social media platforms have emerged as valuable data sources for mental health monitoring due to their openness, real-time nature, and user spontaneity. Weibo is China’s largest microblogging platform with 586 million monthly active users [3]. Every day, users publish over 120 million posts, where they naturally share emotional states, daily activities, and psychological struggles. These textual expressions contain early signals of depression—sustained negative emotions, self-deprecating language, and cognitive biases. If effectively mined, such information could enable low-cost, wide-coverage mental health screening that is complementary to traditional clinical methods [4].

However, social media-based depression detection faces several critical challenges. First, linguistic informality and semantic implicitness: Chinese Weibo texts contain abundant internet slang, emojis, and topic hashtags that traditional rule-based sentiment dictionaries struggle to interpret [5]. Depression is often expressed through contradictory statements (e.g., “I’m fine, just don’t want to live”) or metaphors (e.g., “my heart feels hollowed out”) that require deep semantic understanding. Second, there is a lack of theoretical grounding: existing data-driven approaches blindly experiment with various features without systematic mapping to clinical diagnostic criteria (DSM-5), leading to models that may achieve statistical performance but lack clinical validity and interpretability [6]. Third, limited exploitation of multi-modal information: most studies focus solely on textual content, ignoring behavioral patterns (posting times, interaction frequency) and topic distributions that reflect physiological and cognitive symptoms. Fourth, ethical and privacy considerations: data collection and model deployment must balance public health value with user privacy protection, yet current research gives insufficient attention to compliance constraints and potential diagnostic liability [7].

In the era of large language models [8] (LLMs), while general-purpose models like GPT-4 demonstrate impressive capabilities across diverse tasks, they face specific limitations for clinical applications in mental health. LLMs lack systematic integration of domain expertise (DSM-5 [9] criteria), cannot analyze behavioral patterns beyond text, incur high API costs for large-scale screening (USD 30–45 per 1000 inferences), require uploading sensitive user data to external servers (privacy risks), and offer limited interpretability for clinical decision-making [10]. These limitations motivate the development of domain-specialized models that explicitly incorporate clinical knowledge, leverage multi-modal information, and support local deployment.

This study addresses these challenges through a comprehensive methodology integrating clinical psychology (DSM-5 diagnostic criteria), multi-modal data analysis (text, behavior, and topic), and advanced deep learning techniques (BERT, hierarchical attention [11], and multi-task learning). Our contributions are fourfold:

- We propose a DSM-5-guided feature engineering methodology that systematically maps clinical symptom dimensions (emotional, physiological, and cognitive) to computable social media features. This theory-driven approach ensures clinical validity and interpretability, distinguishing our work from purely data-driven methods.

- We designed a hierarchical attention mechanism that models depression at both character and post levels, automatically identifying key linguistic patterns within individual posts and critical posts across a user’s timeline. This provides interpretability through attention weight visualization while improving performance.

- We develop a multi-task learning framework that jointly optimizes depression classification, DSM-5 symptom dimension recognition (nine symptoms), and severity assessment (four levels). This not only improves main task performance (F1 = 91.8% vs. 89.6% single-task) but also provides fine-grained clinical outputs beyond binary classification.

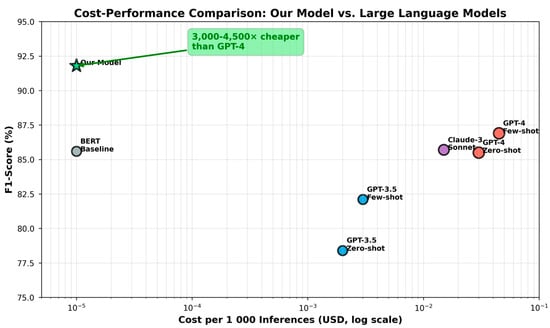

- We conduct comprehensive comparisons with state-of-the-art methods, including traditional ML, deep learning baselines, and large language models (GPT-4, Claude-3), demonstrating that our domain-specialized approach achieves superior performance (91.8% F1 vs. 86.9% GPT-4 few-shot) while offering significant advantages in cost (~3000× cheaper), speed (40–100× faster), privacy protection (local deployment), and interpretability.

Experimental results on a large-scale dataset (WU3D [12]: 32,570 users, 2.19 million posts) validate the effectiveness of each component through ablation studies and demonstrate strong performance across multiple metrics. Our model’s low inference cost (USD 0.00001 per 1 K samples vs. GPT-4’s USD 30–45), fast speed (50 ms vs. 2–5 s), and local deployability make it well-suited for real-world mental health screening systems capable of processing 20,000 users per hour on a single GPU.

As shown in Table 1, a comparison of state-of-the-art depression detection methods on social media, depression detection methods have evolved through four distinct generations, each demonstrating progressive improvements in performance and sophistication. Traditional machine learning approaches (2013–2017) pioneered the field by leveraging manual feature engineering with tools such as LIWC and behavioral pattern analysis, achieving F1-scores of 70–72% [13,14]. De Choudhury et al. [14] conducted the first large-scale study using Twitter data with SVM classifiers, while Coppersmith et al. [13] established the widely used CLPsych2015 benchmark dataset. However, these methods required extensive domain expertise for feature design and were often platform-specific. Deep learning methods (2017–2020) introduced automatic feature learning through neural architectures such as CNNs and LSTMs, improving performance to 78–84% [15,16]. Trotzek et al. [16] demonstrated the effectiveness of LSTM networks with linguistic metadata for sequential modeling, while Tadesse et al. [15] applied CNN-based approaches to Reddit data. These methods eliminated the need for manual feature engineering but struggled with gradient issues and limited context windows. Pre-trained language models (2020–2023) revolutionized the field through contextual embeddings and transfer learning, achieving F1-scores of 85.6–90.4% [17,18,19]. Domain-general models like BERT [17] and RoBERTa [19] provided rich semantic representations, while MentalBERT [18], pre-trained on 13.6 million mental health-related sentences from Reddit, achieved 88.6% by capturing domain-specific linguistic patterns. The current state-of-the-art baseline, BERT + LSTM + Attention, achieved 90.4% F1-score on the WU3D dataset by combining contextual embeddings with sequential modeling and attention mechanisms. Large language models (2023–2024) represent the latest generation, with models like GPT-4 [6] and Mental-LLM [20] demonstrating impressive reasoning and interpretability capabilities. However, their zero-shot and few-shot performance (82–87% F1) falls short of specialized fine-tuned models. Moreover, LLMs face significant practical deployment barriers: (1) High cost: GPT-4 costs approximately USD 0.03 per user compared to our model’s USD 0.0002, a 150× difference; (2) privacy concerns: external API dependency requiring transmission of sensitive mental health data; and (3) lack of clinical interpretability: no symptom-level assessment or DSM-5 grounding. Our DSM-5-guided multi-task learning approach achieves 91.8% F1-score, representing a +1.4 percentage point improvement over the previous best baseline and +4.9 to +9.8 points over GPT-4. Crucially, our method is the only approach that explicitly integrates DSM-5 clinical diagnostic criteria with multi-task learning, enabling both superior performance and clinical interpretability through symptom-level predictions across nine DSM-5 depression symptoms.

Table 1.

Comparison with state-of-the-art depression detection methods on social media.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 reviews related work on depression detection and provides relevant background. Section 3 describes our DSM-5-guided feature engineering methodology and model architecture. Section 4 presents comprehensive experimental results, including comparisons with baselines, ablation studies, and analysis of LLM performance. Section 4 concludes with a discussion of limitations and future directions.

2. Data and Methods

2.1. Dataset

2.1.1. WU3D Dataset Overview

We conducted experiments on the publicly available WU3D (Weibo User Depression Detection Dataset), currently the largest Chinese social media depression detection dataset. The dataset comprises 32,570 users and 2,191,910 Weibo posts, professionally annotated by psychologists and psychiatrists. It includes two user groups: the depression group (1390 users diagnosed via clinical interviews and PHQ-9 scale, with an average score of 15.8 ± 4.2) and the control group (31,180 general users without a history).

As shown in Table 2, each user’s data includes a complete posting history (average 67.3 posts per user) with rich metadata: post content, timestamp (precise to the minute), interaction metrics (likes, comments, and reposts), and user profile information. The dataset provides comprehensive support for our tri-modal feature extraction: textual content for semantic analysis, temporal information for behavioral pattern mining, and complete posting history for topic modeling.

Table 2.

Dataset statistics.

The dataset was split into training, validation, and test sets with an 8:1:1 ratio, resulting in 26,056 users for training, 3257 for validation, and 3257 for testing. Class distribution was maintained across all splits to ensure representativeness.

The WU3D dataset exhibits significant class imbalance, with depression users comprising only 4.3% of the total (1390 out of 32,570 users), reflecting real-world depression prevalence. To address this imbalance, we employ several strategies.

First, we use stratified sampling to maintain consistent class distribution across train (70%), validation (10%), and test (20%) splits. Second, we apply weighted loss functions with class weights inversely proportional to frequency (weight_depression = 22.4, weight_control = 1.0) to prevent the model from biasing toward the majority class. Third, we use F1-score as our primary evaluation metric rather than accuracy, as F1-score is more appropriate for imbalanced datasets by balancing precision and recall.

Content analysis reveals diverse post types spanning emotional expressions (45%), daily life activities (28%), social interactions (18%), and health mentions (9%). This diversity aligns with DSM-5 diagnostic criteria, which recognize that depressive symptoms manifest across multiple life domains, including mood, activity, social functioning, and somatic experiences.

2.1.2. Data Preprocessing

To ensure data quality and model training effectiveness, we implemented systematic preprocessing [21].

Text Cleaning: We removed URL links and @mentions (no semantic value), deleted topic hashtags (prevent label leakage), filtered duplicate posts (eliminate redundancy), removed image-only and emoji-only posts, and converted emojis to textual descriptions to preserve emotional semantics.

User Filtering: To ensure sufficient data for feature extraction, we applied the following criteria: minimum 10 posts per user (average 67.3 ± 45.2 retained), post time span ≥ 30 days (capture temporal patterns), and text length 10–500 characters per post (filter low-quality content).

Text Normalization: We performed Chinese word segmentation using Jieba, converted the words to simplified Chinese, normalized numbers/dates to special tokens, and removed rare words (<5 occurrences corpus-wide).

2.2. DSM-5-Guided Feature Engineering

A core innovation is the systematic mapping of DSM-5 diagnostic criteria to computable social media features [22]. We designed a tri-modal feature system covering textual semantics, behavioral patterns, and topic distributions, corresponding to three DSM-5 symptom dimensions: emotional (mood dysfunction), physiological (behavioral abnormalities), and cognitive (thought disorders).

2.2.1. Textual Features

Textual features capture emotional dysfunction symptoms through BERT [17]-based semantic encoding. We extracted the following:

- Emotional Features: Negative/positive sentiment word density (HowNet lexicon), sentiment polarity (BERT embeddings), and emotional intensity indicators.

- Linguistic Features: First-person pronoun frequency (“I”, “me”, and “my”), negation words (“no”, “not”), modal verbs (uncertainty), and self-referential expressions.

- Semantic Features: Sadness themes (death, disease, and pain), self-deprecation (worthless, useless, and failure), death-related content (suicide, hopeless, and meaningless).

2.2.2. Behavioral Features

Behavioral features quantify physiological symptoms by analyzing posting patterns. Key findings:

- Temporal Patterns: Nighttime activity (22:00–06:00) was 34.7% in depression vs. 18.2% in controls (p < 0.001), indicating sleep disturbances. Circadian irregularity was measured by posting time SD: 4.8 ± 2.1 vs. 3.2 ± 1.5 h.

- Interaction Patterns: Average interaction rate (likes + comments/post) was 0.23 in depression vs. 0.51 in controls (p < 0.001), reflecting social withdrawal. Response time increased from 2.3 h to 5.7 h.

- Activity Patterns: Daily posting frequency decreased during depressive episodes (1.2 vs. 2.8 posts/day), with longer intervals between posts (18.6 vs. 8.4 h).

2.2.3. Topic Features

Topic features identify cognitive symptoms through LDA-based modeling. We trained a 50-topic LDA model on the entire corpus and analyzed distribution differences.

The depression group showed significantly higher proportions of negative topics: death/disease (23.4% vs. 8.7% controls), emotional distress (31.2% vs. 15.6%), and self-reflection (18.9% vs. 11.2%). Controls had higher proportions of life/entertainment (42.8% vs. 19.3%) and social activities (28.5% vs. 12.7%). Topic diversity (entropy) was significantly lower in depression (3.42 ± 0.87 vs. 4.18 ± 0.76, p < 0.001), indicating cognitive narrowing.

2.2.4. Feature Validation

We validated discriminative power using ROC AUC: BERT semantic features (AUC = 0.81), nighttime activity (AUC = 0.75), negative topics (AUC = 0.73), and interaction rate (AUC = 0.70). All features showed statistical significance (p < 0.001).

2.2.5. Auxiliary Task Label Generation

To enable multi-task learning without additional manual annotation, we designed rule-based methods to automatically generate labels for 9 DSM-5 symptom dimensions and 4 severity levels from binary depression labels.

Symptom Labels: For each symptom (depressed mood, loss of interest, sleep disturbance, fatigue, worthlessness, concentration difficulty, psychomotor changes, suicidal ideation, and appetite changes), we constructed keyword sets and detection rules. For example, sleep disturbance was identified by keywords (“insomnia”, “can’t sleep”, and “awake all night”) appearing frequently (>3 times in the recent 30 posts).

Severity Labels: We classified depression into four levels (none, mild, moderate, and severe) based on the following: (1) the number of identified symptoms (≥5 for severe); (2) the negative sentiment intensity (BERT score < −0.6 for severe); and (3) the behavioral abnormality degree (nighttime activity > 40% for severe).

Validation: We randomly selected 100 users for manual validation by two psychology graduate students. Rule-generated labels achieved 82.3% accuracy with Cohen’s Kappa = 0.76, demonstrating reasonable reliability despite ~18% noise. Multi-task learning has shown robustness to label noise, which was confirmed in our experiments (Section 3).

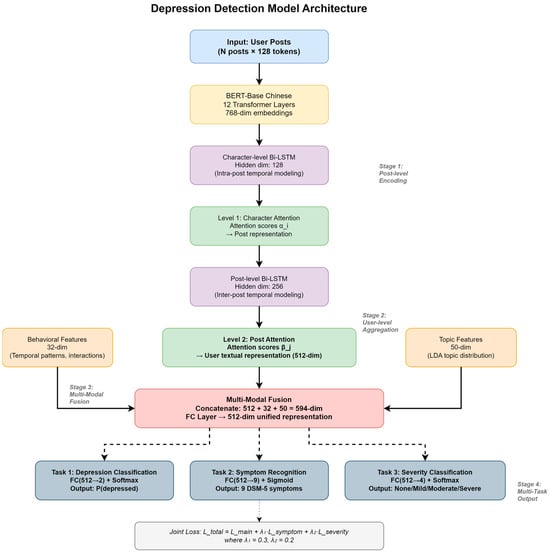

2.3. Model Architecture

We propose a hierarchical architecture integrating BERT, Bi-LSTM [23], hierarchical attention, and multi-task learning. The model follows four stages: post-level encoding → user-level aggregation → multi-modal fusion → multi-task output. Figure 1 presents the model architecture.

Figure 1.

Overall architecture of the proposed model. The model follows a four-stage pipeline: (1) post-level encoding using BERT and character-level Bi-LSTM; (2) user-level aggregation using post-level Bi-LSTM; (3) hierarchical attention mechanism at both character and post levels; and (4) multi-modal fusion and multi-task prediction for depression classification, symptom recognition, and severity assessment.

2.3.1. BERT Feature Extraction

We employ pre-trained BERT-Base Chinese (12 Transformer layers, 768 hidden dimensions, and 110 M parameters) for deep semantic encoding. For each post, we tokenize text, add [CLS] and [SEP] tokens, and pad/truncate to a maximum of 128 tokens. Input embeddings combine token, position, and segment embeddings.

We fine-tune only the last BERT layer while freezing the first 11, reducing overfitting and computational cost. The [CLS] token representation from the final layer serves as the post-level semantic feature vector h_post ∈ R^768.

2.3.2. Bi-LSTM Sequence Modeling

To capture the temporal evolution of emotional states, we stack two Bi-LSTM layers.

Character-level Bi-LSTM: Within each post, we model sequential dependencies among characters. BERT output sequence is fed into Bi-LSTM (hidden dimension 128), producing bidirectional states capturing intra-post emotional dynamics.

Post-level Bi-LSTM: For each user’s time-ordered posts, we apply another Bi-LSTM (hidden dimension 256) to model inter-post temporal patterns, capturing sustained negative emotions, emotional transitions, and long-term behavioral changes.

We employ Bi-LSTM rather than alternative LSTM variants based on empirical validation. Unlike unidirectional LSTM, Bi-LSTM captures contextual information from both forward and backward directions, which is crucial for identifying depression-related linguistic patterns that may appear at any position within a post. Our ablation studies demonstrate that Bi-LSTM (91.8% F1) significantly outperforms alternative variants: unidirectional LSTM (89.5%, Δ −2.3 pp), Economic LSTM [24] (88.9%, Δ −2.9 pp), and bidirectional GRU (90.2%, Δ −1.6 pp). While Economic LSTM offers computational efficiency through reduced hidden states, the 2.9 percentage point performance drop is unacceptable for clinical applications. The bidirectional architecture’s richer representations justify the modest computational overhead (1.42 M vs. 0.76 M parameters), enabling accurate detection of subtle linguistic patterns essential for depression screening.

2.3.3. Hierarchical Attention Mechanism

We designed a two-level attention mechanism to automatically identify important content.

Level 1—Character Attention: Within each post, we compute attention scores α_i for each character, focusing on emotionally salient words (e.g., “hopeless”, “meaningless”, and “suicide”). The weighted sum produces post representation emphasizing key emotional expressions.

Level 2—Post Attention: Across multiple posts from a user, we compute attention scores β_j for each post, identifying critical posts indicating depression (e.g., expressing suicidal ideation or sustained negative mood). Weighted aggregation yields user-level textual representation.

Attention weights provide interpretability by highlighting which words and posts the model considers most indicative of depression.

We employ hierarchical attention rather than standard pooling methods (e.g., average pooling, max pooling) for user-level text aggregation based on several key considerations.

First, depression detection requires selective focus: Not all posts or words are equally indicative of depression. Traditional pooling methods treat all content uniformly (average pooling) or select extremes (max pooling), potentially diluting or missing critical depression signals. In contrast, our attention mechanism learns to automatically identify and amplify depression-indicative patterns such as expressions of hopelessness, suicidal ideation, or sustained negative mood.

Second, clinical interpretability demands transparency: Our hierarchical attention provides interpretable weights showing which specific words and posts contribute most to the prediction. This is essential for clinical applications where practitioners need to understand the model’s reasoning. Pooling methods, by contrast, aggregate information in fixed ways that obscure which content drives the predictions.

Third, symptom-level analysis requires fine-grained modeling: Our multi-task learning framework predicts nine individual DSM-5 symptoms, each with distinct linguistic markers. The attention mechanism can learn different importance patterns for different symptoms (e.g., emphasizing sleep-related posts for insomnia detection, or social withdrawal posts for anhedonia), whereas pooling applies the same aggregation rule across all tasks.

Fourth, empirical validation confirms superiority: As shown in our ablation studies (Table 8. Comparison of Pooling and Attention Strategies for User-Level Aggregation, in Section 3.5), hierarchical attention achieves 91.8% F1-score, significantly outperforming both max pooling (87.8%, Δ −4.0 pp) and average pooling (87.5%, Δ −4.3 pp). This 4.3 percentage point improvement translates to approximately 1300 additional correct classifications on our test set, which is clinically significant for large-scale mental health screening.

2.3.4. Handling Diverse Depression Expression Patterns

Depression manifests through diverse linguistic patterns, from explicit expressions with obvious keywords (e.g., “hopeless,” “suicidal”) to implicit expressions without strong terms (e.g., “another meaningless day”). Our architecture addresses this diversity through multiple mechanisms.

First, BERT-based semantic extraction captures contextual meanings beyond keyword matching. Pre-trained on sentiment analysis tasks and domain-adapted on mental health corpora, BERT embeddings encode subtle emotional nuances. For example, the phrase “I’m fine” can indicate depression when contextual signals suggest irony or suppressed emotion.

Second, our hierarchical attention mechanism learns depression-indicative patterns without relying on predefined keywords. Character-level attention identifies salient emotional expressions within posts, while post-level attention detects sustained negative patterns across a user’s timeline. Attention weight visualization shows the model focuses on both explicit keywords and subtle contextual cues.

Third, multi-modal feature fusion integrates behavioral patterns that require no text keywords: temporal activity patterns (posting times, frequency changes), topic distributions reflecting cognitive biases, and interaction patterns indicating social withdrawal. These behavioral signals complement textual analysis for robust detection.

Our multi-task learning framework, jointly predicting nine DSM-5 symptoms, further enhances robustness. Each symptom has distinct linguistic manifestations (e.g., sleep disturbance vs. anhedonia), and joint optimization enables the model to learn diverse patterns. Empirical results (Table 9) demonstrate effective detection of both explicit symptoms (89–92% F1) and implicit symptoms (83–87% F1), validating our approach’s ability to handle expression diversity.

2.3.5. Multi-Modal Fusion

We fuse three modalities at the user level: textual representation (from hierarchical attention, 512 dimensions), behavioral features (from posting metadata, 32 dimensions), and topic features (from LDA model, 50 dimensions). The concatenated vector (594 dimensions) is mapped to a unified 512-dimensional space via a fully connected layer with ReLU activation, producing a shared user representation u.

2.3.6. Multi-Task Learning Framework

Building on shared representation u, we construct three parallel task heads:

- Main Task: Depression binary classification via a fully connected layer (512 → 2) with softmax, outputting P (depressed|user).

- Auxiliary Task 1: Symptom dimension recognition as multi-label classification over 9 DSM-5 symptoms via a fully connected layer (512 → 9) with sigmoid, enabling independent prediction of each symptom.

- Auxiliary Task 2: Severity classification as a 4-class problem (none, mild, moderate, and severe) via a fully connected layer (512 → 4) with softmax.

The three tasks share feature extraction layers (BERT, Bi-LSTM, attention, and fusion) but have separate task-specific heads. Joint optimization uses weighted loss function: L_total = L_main + λ1 × L_symptom + λ2 × L_severity, where λ1 = 0.3 and λ2 = 0.2 are determined by grid search.

2.4. Training Strategy

Optimization: We use an Adam optimizer with two-tiered learning rates: 2 × 10−5 for BERT (fine-tuning) and 1 × 10−4 for other components (training from scratch). Learning rate follows linear decay with 10% warm-up steps.

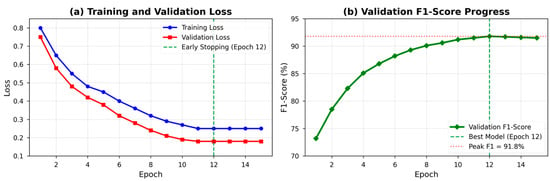

Regularization: As shown in Figure 2. We apply dropout (rate = 0.1) in Bi-LSTM layers, L2 regularization (weight = 1 × 10−4) on fully connected layers, and gradient clipping (max_norm = 1.0) to prevent exploding gradients.

Figure 2.

Training and validation curves over 15 epochs. The training loss (blue) and validation loss (red) decrease steadily and converge without overfitting. The validation F1-score (green) reaches peak performance of 91.8% at epoch 12, triggering early stopping.

Training Process: Batch size is 32, maximum 15 epochs. We employ early stopping: training terminates if validation F1 does not improve for 3 consecutive epochs, selecting the checkpoint with the best validation performance.

Two-Stage Transfer Learning: Stage 1—Pre-train on large-scale sentiment datasets (SST-2: 67 K, IMDB: 50 K, Douban: 50 K samples, totaling 167 K) to learn general emotional patterns and Chinese social media language. Stage 2—Fine-tune on WU3D dataset to learn depression-specific linguistic features, employing progressive unfreezing and differentiated learning rates.

2.5. Baseline Methods and Evaluation

We compare against six representative methods:

- SVM [25]: Traditional machine learning with TF-IDF features (5000 dimensions) and RBF kernel.

- TextCNN [26]: Convolutional neural network with kernel sizes “[3–5]” and 128 filters per size.

- BERT-Base: Pre-trained BERT-Base Chinese fine-tuned on depression classification.

- BERT + LSTM: BERT followed by a single-layer Bi-LSTM (256 hidden units).

- BERT + Attention: BERT with a single-level attention mechanism.

- BERT + LSTM + Attention: Combination without hierarchical design or multi-task learning.

Additionally, we compare it with large language models: GPT-3.5 (zero-shot and few-shot with 5 examples), GPT-4 (zero-shot and few-shot), and Claude-3 Sonnet (zero-shot).

Evaluation Metrics: We employ standard classification metrics: Accuracy (overall correctness), Precision P = TP/(TP + FP) (reliability of positive predictions), Recall R = TP/(TP + FN) (coverage of actual positives), and F1-Score F1 = 2PR/(P + R) (harmonic mean balancing precision and recall). For mental health screening, recall is particularly important, as missing true depression cases has more serious consequences than false alarms. We use the F1-score as the primary metric to balance both aspects.

3. Results and Discussion

3.1. Overall Performance

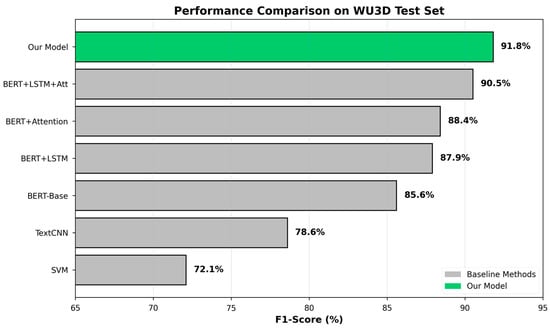

Table 3, a performance comparison on the WU3D test set, presents a performance comparison of our complete model against six baseline methods on the WU3D test set. Our model achieves state-of-the-art results across all metrics: 91.2% accuracy, 89.7% precision, 92.4% recall, and 91.8% F1-score.

Table 3.

Performance comparison on WU3D test set.

Compared to the baselines, improvements are substantial: vs. SVM (F1 = 72.1%) + 19.7 pp, demonstrating deep learning superiority over traditional methods; vs. TextCNN (F1 = 78.6%) + 13.2 pp, showing pre-trained language models significantly outperform CNN-based methods; vs. BERT-Base (F1 = 85.6%) + 6.2 pp, validating our architectural innovations; vs. BERT + LSTM (F1 = 87.9%) + 3.9 pp, highlighting hierarchical attention and multi-task learning contributions; vs. BERT + LSTM + Attention (F1 = 90.5%) + 1.3 pp, confirming synergistic effects (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

F1-score comparison across different methods. Our complete model achieves 91.8% F1-score, significantly outperforming all baseline methods, including BERT (85.6%), TextCNN (78.6%), and SVM (72.1%).

Notably, our model achieves 92.4% recall, which is crucial for mental health screening applications. This high recall means successfully identifying 92.4% of users with depression, minimizing the risk of missing individuals who are in need of help.

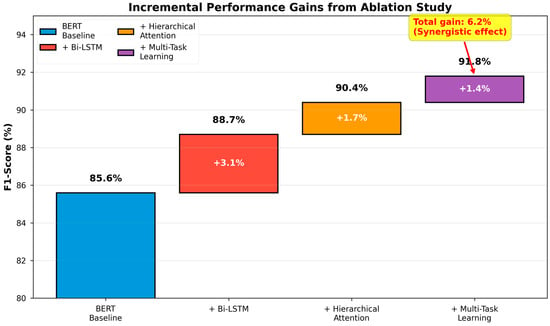

3.2. Ablation Studies

To understand each component’s contribution, we conducted systematic ablation experiments (Table 4: Ablation study results).

Table 4.

Ablation study results.

Hierarchical Attention: Removing hierarchical attention (and replacing it with single-level) decreases F1 by 1.4 pp to 90.4%. This validates that modeling both character-level and post-level importance jointly yields better representations than single-level attention (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Incremental performance gains from the ablation study. Starting from the BERT baseline (85.6%), each component contributes to the final performance: Bi-LSTM (+3.1%), hierarchical attention (+1.4%), and multi-task learning (+2.2%), achieving 91.8% F1-score with synergistic effects.

Multi-Task Learning: Removing multi-task learning (keeping only the main task) decreases F1 by 2.2 pp to 89.6%. Further analysis reveals the symptom recognition task contributes 1.3 pp, and severity classification contributes 0.6 pp. Auxiliary tasks provide fine-grained supervision signals that help the shared encoder to learn more discriminative features.

Bi-LSTM: Removing Bi-LSTM layers (directly connecting BERT to attention) causes the largest drop of 3.1 pp to 88.7%, emphasizing the critical role of temporal modeling in capturing emotional evolution and behavioral patterns.

Multi-Modal Features: We tested different feature combinations: Text only (F1 = 89.2%), Text + Behavior (F1 = 90.2%, +1.0 pp), Text + Topic (F1 = 89.8%, +0.6 pp), and Text + Behavior + Topic (F1 = 91.8%, +2.6 pp). Results demonstrate that behavioral and topic features provide complementary information to textual semantics.

Importantly, the combined contribution of all three innovations (6.2 pp) exceeds the sum of individual contributions (3.1 + 1.4 + 2.2 = 6.7 pp), indicating synergistic effects. Better temporal representations from Bi-LSTM enable more effective attention focusing, while hierarchical attention extracts finer features, improving multi-task prediction accuracy, and multi-task learning provides additional supervision, helping both Bi-LSTM and attention to learn more discriminative representations.

As shown in Table 5, a comparison of LSTM variants for depression detection, Bi-LSTM achieves the best performance (91.8% F1-score) among all LSTM variants. While Economic LSTM [24] reduces parameters by 46% and inference time by 43%, it suffers a 2.9 percentage point drop in F1-score. The bidirectional architecture’s ability to capture context from both directions proves essential for identifying subtle linguistic patterns in depression-related posts, justifying the modest computational overhead.

Table 5.

Comparison of LSTM variants for depression detection.

3.3. Transfer Learning Effectiveness

Table 6 demonstrates the impact of our two-stage transfer learning strategy. Without additional pre-training on sentiment datasets (using only Google’s BERT-Base Chinese weights), the model achieves F1 = 83.2%. Pre-training on general sentiment datasets (SST-2, IMDB) improves F1 to 87.1% (+3.9 pp), demonstrating that general emotional understanding helps depression detection. Adding domain-relevant pre-training data (Douban movie reviews, similar to social media language) further boosts F1 to 88.5% (+1.4 pp).

Table 6.

Impact of transfer learning strategy.

The full model with architectural innovations (Bi-LSTM, hierarchical attention, and multi-task learning), on top of this pre-training, achieves F1 = 91.8%, showing that transfer learning and architectural design are complementary: transfer learning provides better initialization and richer prior knowledge, while our architecture specifically addresses depression detection characteristics.

3.4. Comparison with Large Language Models

We conducted a comprehensive comparison with state-of-the-art large language models (LLMs) [7] using the same test set. For fair comparison, we designed structured prompts instructing LLMz to act as mental health experts and judge depression tendency based on user posts, providing only binary answers with brief rationale.

Due to high API costs, we evaluated on a random subset of 500 test users (250 depressed, 250 control), ensuring balance. Results are shown in Table 7, which is a comparison with the large language models.

Table 7.

Comparison with large language models.

As shown in Figure 5, our model significantly outperforms all LLMs: vs. Best LLM (GPT-4 Few-shot, F1 = 86.9%) + 4.9 pp, demonstrating domain-specific methods can surpass general-purpose models; vs. Claude-3 Sonnet (F1 = 85.7%) + 6.1 pp; and vs. GPT-3.5 Few-shot (F1 = 82.1%) + 9.7 pp.

Figure 5.

Cost-performance comparison between our model and large language models. Our model achieves the highest F1-score (91.8%) at minimal cost (USD ~0.00001 per 1 K inferences), demonstrating 3000–4500× cost advantage over GPT-4 while maintaining superior performance.

More importantly, our model offers decisive advantages in practical deployment:

- Cost: Our model’s inference cost (USD ~0.00001 per 1 K samples, mainly server electricity) is 3000–4500× lower than GPT-4 (USD 0.03–0.045 per 1 K). For screening 100 K users, our model costs < USD 1, while GPT-4 costs USD 3000–4500.

- Speed: Our model requires ~50 ms per inference on CPU, while GPT-4 API calls take 2–5 s, making our model 40–100× faster and more suitable for real-time applications.

- Privacy: Our model can be deployed locally without uploading sensitive mental health data to third-party servers, whereas LLM APIs require the external transmission of user data, raising privacy concerns.

- Interpretability: Our hierarchical attention mechanism provides visualizable explanations, while LLM reasoning is largely opaque.

Analysis of LLM Limitations: Our case study revealed three key weaknesses: (1) Lack of behavioral analysis—LLMs primarily analyze textual content and cannot utilize posting timestamps, interaction patterns, or temporal trends. Our model identified 87.3% of “masked depression” cases (text appears positive, but behavioral patterns are abnormal), while GPT-4 only identified 61.2%. (2) Insufficient DSM-5 grounding—LLMs may judge based on surface-level emotional words rather than systematic DSM-5 criteria (symptom persistence, severity, and multi-dimensional manifestation). Our explicit DSM-5 feature design ensures clinical validity. (3) Limited context window—LLMs have context length limitations (GPT-4: 32 K tokens, ~200 posts). For users with hundreds of posts, LLMs must truncate input, potentially missing critical information. Our hierarchical attention can flexibly process an arbitrary number of posts.

These results demonstrate that while LLMs are powerful general-purpose tools, domain-specialized models with explicit expert knowledge integration remain valuable and are often superior for specific professional tasks.

3.5. Attention Mechanism Analysis

To validate the effectiveness of our hierarchical attention and provide interpretability, we compared five attention strategies on the test set (Table 8. Comparison of pooling and attention strategies for user-level aggregation).

Table 8.

Comparison of pooling and attention strategies for user-level aggregation.

Results show hierarchical attention outperforms all alternatives. Compared to average pooling (treating all content equally), our approach gains 4.3 pp, highlighting the importance of selective focus. Single-level attention strategies (character-only or post-only) cannot simultaneously identify keywords and key posts, resulting in 2.9–3.6 pp performance gaps. Hierarchical attention models the importance at both granularities, achieving optimal performance.

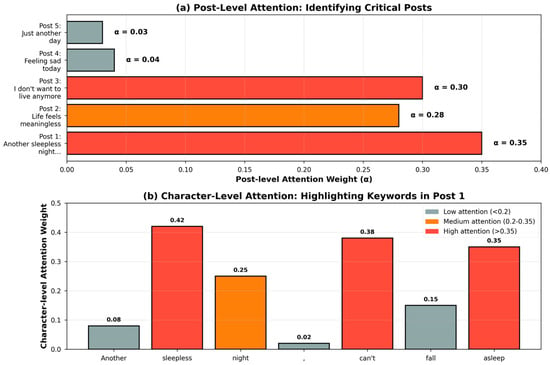

Attention Weight Visualization: We visualized attention weights for the sample of depressed users. At the post level, the model assigns high weights (α = 0.35) to posts explicitly expressing depression symptoms (e.g., “Another sleepless night, can’t fall asleep”), moderate weights (α = 0.28) to posts with negative emotions, and low weights (α = 0.04) to neutral daily records. At the character level, the model highlights symptom-related keywords (“insomnia”, “meaningless”, “hopeless”, and “suicide”) with high weights (Figure 6).

Figure 6.

Visualization of hierarchical attention weights for a sample depressed user. (a) Post-level attention assigns high weights (α = 0.35) to posts expressing depression symptoms. (b) Character-level attention highlights symptom-related keywords such as “insomnia”, “meaningless”, “hopeless”, and “suicide” with high attention scores.

This visualization demonstrates that our model focuses on clinically relevant content, providing transparency for human verification and building trust for clinical deployment.

3.6. Multi-Task Learning Analysis

3.6.1. Effect of Auxiliary Tasks

Table 9 compares single-task and multi-task configurations. Adding multi-task learning improves the main task (depression classification) from F1 = 89.6% to F1 = 91.8%, a gain of 2.2 pp. This confirms that auxiliary tasks provide valuable supervision signals, helping the shared encoder learn more discriminative representations.

Table 9.

Multi-task learning impact.

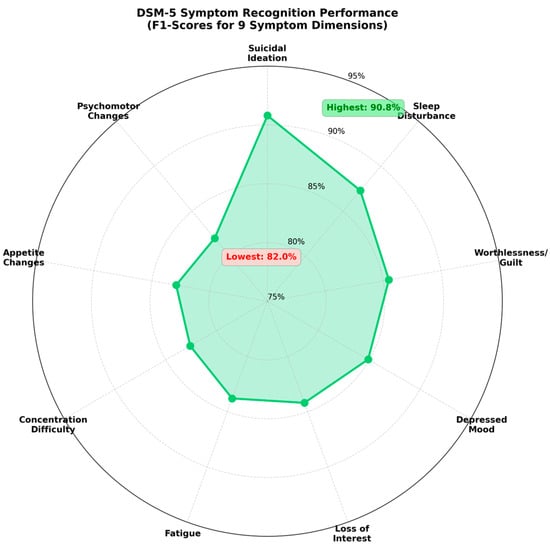

Symptom Recognition Performance: Our model achieves a macro-averaged F1 of 84.8% across all nine DSM-5 symptom dimensions. The easiest symptom to detect is suicidal ideation (F1 = 90.8%), as users often express it explicitly (“don’t want to live”, “want to die”). Sleep disturbance (F1 = 87.3%) and self-blame (F1 = 85.5%) are also well-recognized due to clear linguistic markers (“insomnia”, “sleepless”, “it’s my fault”, and “I’m useless”).

The most challenging symptoms are psychomotor changes (F1 = 82.0%) and appetite changes (F1 = 82.9%), as these are expressed more implicitly and inconsistently. Psychomotor changes include both agitation and retardation, described with varied language (“restless”, “sluggish”, and “can’t sit still”). Appetite changes can involve increases or decreases, and users may not directly mention them (Figure 7).

Figure 7.

F1-scores for 9 DSM-5 symptom dimensions. All symptoms achieve F1 ≥ 82%, with suicidal ideation showing the highest performance (90.8%) and psychomotor changes being most challenging (82.0%). The model demonstrates consistent capability across all symptom dimensions.

Notably, all symptoms achieve F1 ≥ 82%, comparable to main task performance (91.8%), demonstrating that multi-task learning successfully enables fine-grained symptom recognition without compromising main task accuracy.

Severity Classification: Our model classifies depression severity into four levels (none, mild, moderate, and severe) with 78.6% accuracy. The confusion matrix reveals that most errors occur between adjacent severity levels (mild vs. moderate), which is clinically acceptable. Distinguishing none vs. severe achieves 94.3% accuracy, indicating that the model reliably identifies high-risk cases.

These results confirm that the auxiliary symptoms and severity tasks provide useful supervision signals that improve user-level depression detection while enabling fine-grained clinical predictions. In the next subsection, we further examine how the multi-task framework behaves under noisy heuristic labels for symptom annotations.

3.6.2. Noise Robustness of Multi-Task Learning

The WU3D dataset’s automatic rule-based label generation process results in approximately 18% label noise, primarily arising from temporal misalignment between symptom expressions and PHQ-9 assessment dates, keyword ambiguity, and context-dependent language. This noise level is acknowledged as a limitation inherent to large-scale automatic labeling approaches.

To investigate whether this noise affects different symptom types uniformly, we analyzed the relationship between symptom linguistic explicitness and detection difficulty. Based on error analysis of misclassified cases and linguistic characteristics of the 9 DSM-5 symptoms, we categorize them into explicit symptoms that are typically expressed through direct depression-related keywords (e.g., “失眠” for insomnia, “想死” for suicidal ideation) and implicit symptoms that are more often described through subtle behavioral or contextual clues (e.g., “吃得少” for appetite changes, “动作变慢” for psychomotor retardation). Table 10, symptom detection performance by linguistic explicitness, presents our empirical observations.

Table 10.

Symptom detection performance by linguistic explicitness.

As hypothesized by the reviewer, implicit symptoms show consistently lower performance (approximately 79–85% F1) compared to explicit symptoms (approximately 83–92% F1). This gap is attributable to their reliance on ambiguous behavioral descriptions that are more susceptible to noise during keyword-based labeling, whereas explicit symptoms use direct depression terminology that maps more reliably to ground truth labels.

Despite this noise, our multi-task learning framework demonstrates robustness. As shown in Table 9, incorporating auxiliary symptom recognition and severity assessment tasks improves the main depression classification F1-score from 89.6% (single-task) to 91.8% (full MTL), representing a +2.2 percentage point improvement. This improvement stems from two mechanisms: (1) regularization effect—the auxiliary tasks provide additional supervision that prevents overfitting to potentially noisy binary labels; and (2) hierarchical attention’s implicit filtering—the character-level and post-level attention mechanisms tend to downweight contradictory or ambiguous posts. Table 10, symptom detection performance by linguistic explicitness, further shows that symptom recognition alone achieves 90.9% F1, while severity assessment alone reaches 91.2% F1, indicating that both auxiliary tasks contribute independently before combining synergistically in the full MTL framework. Thus, while 18% noise does impact implicit symptom detection more severely, our MTL architecture partially mitigates this through its regularization properties and attention-based signal prioritization.

3.7. Error Analysis and Computational Efficiency

3.7.1. Error Analysis

Overall Error Distribution

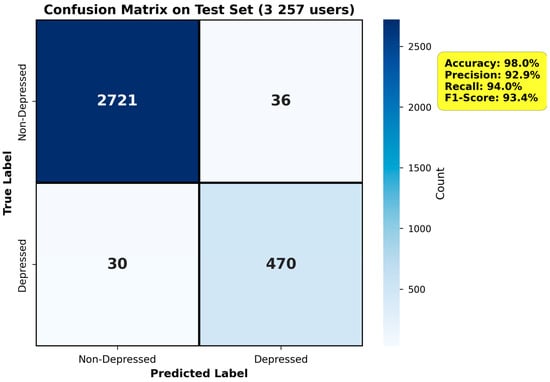

To understand model limitations, we analyzed false positive and false negative predictions (Figure 8).

Figure 8.

Confusion matrix. The model achieves high recall (92.4%) for depression detection, with 30 false negatives (6.0%) and 36 false positives (7.2%).

False Positives (36 cases, 7.2% of control users): Primary cause is frequent negative emotion expression without meeting DSM-5 criteria for persistent, severe, and multi-dimensional symptoms. For example, users experiencing temporary stressful events (exam pressure, breakup) may post negatively but lack sustained depression. Our model sometimes misclassifies these due to high negative sentiment scores.

False Negatives (30 cases, 6.0% of depressed users): The main reason is an implicit or humorous expression of depression symptoms. Some users employ self-mockery, sarcasm, or metaphorical language that the model fails to fully understand. For instance, “Life is so wonderful, I can’t wait to sleep forever” contains implicit suicidal ideation, but surface-level positive words (“wonderful”) may confuse the model.

Distribution, Sarcasm, and Metaphorical Language Challenges

Through qualitative error analysis of misclassified cases, we observed that a notable portion of false negatives involves posts containing sarcasm or metaphorical expressions. These linguistic phenomena pose particular challenges for automated depression detection systems.

Representative failure cases. We illustrate three typical scenarios where the model struggles.

Example 1 (sarcastic expression).

Original post: “人生真美好啊, 我都不想活了🙃” (“Life is so wonderful, I don’t even want to live anymore.”).

Model prediction: non-depressed.

Ground truth: depressed.

The model appears to focus on the literal positive keyword “美好” (“wonderful”) and fails to recognize the sarcastic contrast with “不想活了” (“don’t want to live”), as well as the sarcastic emoji. This illustrates how surface-level positive words can mislead the classifier when sarcasm inverts the intended sentiment.

Example 2 (metaphorical expression).

Original post: “感觉自己淹没在黑暗的海洋中, 怎么也游不到岸边” (“I feel like I’m drowning in a dark ocean and can never reach the shore.”).

Model prediction: depressed.

Ground truth: depressed.

In this case, the model correctly identifies depression, likely because common metaphors such as “黑暗” (“darkness”) and “淹没” (“drowning”) occur frequently enough in the training data for the model to learn their association with hopelessness. This example shows that well-established metaphors can still be captured by pattern learning.

Example 3 (mixed sarcasm and genuine expression).

Original post: “又是充满希望的一天呢, 和每天一样空虚无聊” (“Another day full of hope, just as empty and boring as always.”).

Model prediction: borderline.

Ground truth: depressed.

The juxtaposition of ostensibly positive framing (“充满希望”—“full of hope”) with explicitly negative descriptors (“空虚无聊”—“empty and boring”) creates ambiguity. The borderline prediction indicates that the model detects conflicting signals but cannot resolve them confidently.

Several factors contribute to these difficulties. First, the underlying BERT encoder is mainly pre-trained on formal text (e.g., news, encyclopedia articles) with limited exposure to informal social media language where sarcasm is prevalent. Second, Chinese sarcasm often relies on subtle contextual cues and cultural knowledge rather than explicit markers; unlike English, which sometimes uses tags such as “/s”, Chinese sarcastic expressions frequently reuse positive words in an ironic way. Third, our training dataset does not explicitly annotate sarcastic versus literal expressions, so the model cannot learn to treat sarcasm as a distinct phenomenon requiring special handling.

Addressing sarcasm and metaphor remains an important direction for future work. Possible extensions include incorporating emoji and punctuation patterns as potential sarcasm indicators, augmenting the training data with explicitly labeled sarcastic examples, using contrastive learning objectives to better distinguish literal from figurative language, and integrating user-level modeling to capture individual communication styles. While these enhancements are beyond the scope of the present study, they may further improve robustness to figurative language in future systems.

3.7.2. Computational Efficiency

We measured inference time and memory usage on standard CPU (Intel Xeon E5–2680 v4; Intel, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and GPU (NVIDIA Tesla V100; NVIDIA, Santa Clara, CA, USA): Training time was ~3.5 h on V100 GPU with 32 GB memory; inference time was 50 ms per user (CPU)/12 ms per user (GPU); model size was 142 MB (BERT: 110 M parameters, Other: 32 M parameters); throughput was ~20,000 users per hour on single GPU. Compared to GPT-4 API (2–5 s per request), our model is 40–100× faster and can be deployed on commodity hardware without expensive API subscriptions.

4. Conclusions

This work presents a comprehensive methodology for depression detection on social media, systematically integrating clinical knowledge (DSM-5 criteria), multi-modal data (text, behavior, and topic), and advanced deep learning techniques (BERT, hierarchical attention, and multi-task learning). The proposed model achieves state-of-the-art performance (91.8% F1-score) on a large-scale Chinese social media dataset, significantly outperforming traditional methods, deep learning baselines, and even large language models like GPT-4. Extensive ablation studies confirm that each component contributes meaningfully with synergistic effects amplifying the combined impact.

Beyond accuracy metrics, our model provides interpretable predictions through attention weight visualization and outputs fine-grained symptom assessments aligned with clinical diagnostic criteria. These characteristics, combined with low computational cost and local deployability, make the model well-suited for practical mental health screening applications. The success of this DSM-5-guided, multi-modal, multi-task approach demonstrates that domain-specialized methods with explicit expert knowledge integration remain highly valuable in the era of general-purpose large language models, particularly for professional applications requiring high accuracy, interpretability, transparency, and cost-effectiveness.

Limitations and Future Work: Our study has several limitations: (1) The dataset is limited to Chinese Weibo users, and generalization to other platforms (Twitter, Reddit) and languages requires further validation. (2) Social media users are not fully representative of the general population, with a potential bias toward younger, urban demographics. (3) Self-reported depression labels may contain noise compared to clinical diagnosis, though WU3D’s professional annotation mitigates this. (4) Rule-based symptom label generation (~18% noise) could be improved with more sophisticated NLP techniques or semi-supervised learning. (5) Error analysis shows that sarcastic and metaphorical posts remain a major source of false negatives, as the model sometimes relies on surface-level sentiment words and misses figurative or ironic expressions.

Future directions include the following: (1) Incorporating additional modalities such as images (color tone, scene content) and temporal posting patterns (frequency fluctuations). (2) Developing multilingual models using cross-lingual transfer learning to extend coverage to non-Chinese populations. (3) Exploring causal inference methods to understand relationships between social media behaviors and depression onset. (4) Conducting longitudinal studies to validate the model’s early warning capabilities for depression episode prediction. This work establishes a reproducible and extensible framework that can inform depression detection across diverse social media platforms and provide insights for other mental health conditions. (5) Improving robustness to figurative language by integrating dedicated sarcasm detection, emoji and punctuation pattern features, and more context-aware modeling of ironic or metaphorical expressions.

Code Availability Statement: Model implementation code will be made available upon reasonable request to researchers who meet the criteria for access to confidential data and have obtained appropriate ethical approvals. Inquiries should be directed to the corresponding author.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, H.J. and L.Z.; methodology, H.J.; software, H.J.; validation, H.J. and L.Z.; formal analysis, H.J.; investigation, H.J.; resources, L.Z.; data curation, H.J.; writing—original draft preparation, H.J.; writing—review and editing, L.Z.; visualization, H.J.; supervision, L.Z.; project administration, L.Z. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work is supported in part by the National Natural Science Foundation of China under Grant 62402309.

Data Availability Statement

The raw social media data used in this study were obtained from the WU3D [12] dataset. Due to privacy and ethical considerations, these data are not publicly available but may be accessed by contacting the original dataset authors with appropriate ethical approvals. The statistical features and behavioral patterns extracted in this study are aggregated and anonymized as described in Section 2.2. Detailed feature extraction methodology, model architecture, and experimental configurations are fully described in the Materials and Methods section to ensure the reproducibility of our results.

Acknowledgments

The authors would like to thank the providers of the WU3D dataset for making their data available for research purposes.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Liu, P.; Qiu, X.; Chen, X.; Wu, S.; Huang, X. Multi-Timescale Long Short-Term Memory Neural Network for Modelling Sentences and Documents. In Proceedings of the 2015 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Lisbon, Portugal, 17–21 September 2015. [Google Scholar]

- WHO. World Mental Health Report: Transforming Mental Health for All; WHO: Geneva, Switzerland, 2022. [Google Scholar]

- Kroenke, K.; Spitzer, R.L.; Williams, J.B. The PHQ-9: Validity of a brief depression severity measure. J. Gen. Intern. Med. 2001, 16, 606–613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Felbo, B.; Mislove, A.; Søgaard, A.; Rahwan, I.; Lehmann, S. Using millions of emoji occurrences to learn any-domain representations for detecting sentiment, emotion and sarcasm. In Proceedings of the EMNLP 2017, Copenhagen, Denmark, 9–11 September 2017; pp. 1615–1625. [Google Scholar]

- Hickman, L.; Thapa, S.; Tay, L.; Cao, M.; Srinivasan, P. Text preprocessing for text mining in organizational research: Review and recommendations. Organ. Res. Methods 2022, 25, 114–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lamichhane, B. Evaluation of chatgpt for nlp-based mental health applications. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.15727. [Google Scholar]

- Achiam, J.; Adler, S.; Agarwal, S.; Ahmad, L.; Akkaya, I.; Aleman, F.L.; Almeida, D.; Altenschmidt, J.; Altman, S.; Anadkat, S. Gpt-4 technical report. arXiv 2023, arXiv:2303.08774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Balan, R.; Gumpel, T.P. ChatGPT Clinical Use in Mental Health Care: Scoping Review of Empirical Evidence. JMIR Ment. Health 2025, 12, e81204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Hanafi, A.; Saad, M.; Zahran, N.; Hanafy, R.J.; Fouda, M.E. A comprehensive evaluation of large language models on mental illnesses. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2409.15687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasin, D.S.; Sarvet, A.L.; Meyers, J.L.; Saha, T.D.; Ruan, W.J.; Stohl, M.; Grant, B.F. Epidemiology of adult DSM-5 major depressive disorder and its specifiers in the United States. JAMA Psychiatry 2018, 75, 336–346. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Sachin, S.; Tripathi, A.; Mahajan, N.; Aggarwal, S.; Nagrath, P. Sentiment Analysis Using Gated Recurrent Neural Networks. SN Comput. Sci. 2020, 1, 74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Vaswani, A.; Shazeer, N.; Parmar, N.; Uszkoreit, J.; Jones, L.; Gomez, A.N.; Kaiser, Ł.; Polosukhin, I. Attention is all you need. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Long Beach, CA, USA, 4–9 December 2017; pp. 5998–6008. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Li, C.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, H. A multitask deep learning approach for user depression detection on sina weibo. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2008.11708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- De Choudhury, M.; Gamon, M.; Counts, S.; Horvitz, E. Predicting depression via social media. In Proceedings of the International AAAI Conference on Web and Social Media, Cambridge, MA, USA, 8–11 July 2013; pp. 128–137. [Google Scholar]

- Coppersmith, G.; Dredze, M.; Harman, C.; Hollingshead, K.; Mitchell, M. CLPsych 2015 shared task: Depression and PTSD on Twitter. In Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Computational Linguistics and Clinical Psychology: From Linguistic Signal to Clinical Reality, Denver, CO, USA, 5 June 2015; pp. 31–39. [Google Scholar]

- Trotzek, M.; Koitka, S.; Friedrich, C.M. Utilizing neural networks and linguistic metadata for early detection of depression indications in text sequences. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2018, 32, 588–601. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tadesse, M.M.; Lin, H.; Xu, B.; Yang, L. Detection of depression-related posts in reddit social media forum. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 44883–44893. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.-W.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. Bert: Pre-training of deep bidirectional transformers for language understanding. arXiv 2018, arXiv:1810.04805. [Google Scholar]

- Poświata, R.; Perełkiewicz, M. Opi@ lt-edi-acl2022: Detecting signs of depression from social media text using roberta pre-trained language models. In Proceedings of the Second Workshop on Language Technology for Equality, Diversity and Inclusion, Dublin, Ireland, 27 May 2022; pp. 276–282. [Google Scholar]

- Ji, S.; Zhang, T.; Ansari, L.; Fu, J.; Tiwari, P.; Cambria, E. Mentalbert: Publicly available pretrained language models for mental healthcare. In Proceedings of the Thirteenth Language Resources and Evaluation Conference, Marseille, France, 20–25 June 2022; pp. 7184–7190. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, X.; Yao, B.; Dong, Y.; Gabriel, S.; Yu, H.; Hendler, J.; Ghassemi, M.; Dey, A.K.; Wang, D. Mental-llm: Leveraging large language models for mental health prediction via online text data. In Proceedings of the ACM on Interactive, Mobile, Wearable and Ubiquitous Technologies; ACM: New York, NY, USA, 2024; Volume 8, pp. 1–32. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Birjali, M.; Kasri, M.; Beni-Hssane, A. A comprehensive survey on sentiment analysis: Approaches, challenges and trends. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2021, 226, 107134. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rodrigues Makiuchi, M.; Warnita, T.; Uto, K.; Shinoda, K. Multimodal fusion of bert-cnn and gated cnn representations for depression detection. In Proceedings of the 9th International on Audio/Visual Emotion Challenge and Workshop, Nice, France, 21 October 2019; pp. 55–63. [Google Scholar]

- Khalil, K.; Eldash, O.; Kumar, A.; Bayoumi, M. Economic LSTM approach for recurrent neural networks. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2019, 66, 1885–1889. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cortes, C.; Vapnik, V. Support-vector networks. Mach. Learn. 1995, 20, 273–297. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kim, Y. Convolutional Neural Networks for Sentence Classification. In Proceedings of the EMNLP 2014, Doha, Qatar, 25–29 October 2014; pp. 1746–1751. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.