Abstract

In the context of small, battery-powered systems, a lightweight, reusable architecture is needed for integrated measurement, visualization, and cloud telemetry that minimizes hardware complexity and energy footprint. Existing solutions require high resources. This limits their applicability in Internet of Things (IoT) devices with low power consumption. The present work demonstrates the process of design, implementation and experimental evaluation of a single-cell lithium-ion battery monitoring prototype, intended for standalone operation or integration into other systems. The architecture is compact and energy efficient, with a reduction in complexity and memory usage: modular architecture with clearly distinguished responsibilities, avoidance of unnecessary dynamic memory allocations, centralized error handling, and a low-power policy through the usage of deep sleep mode. The data is stored in a cloud platform, while minimal storage is used locally. The developed system combines the functional requirements for an embedded external battery monitoring system: local voltage and current measurement, approximate estimation of the State of Charge (SoC) using a look-up table (LUT) based on the discharge characteristic, and visualization on a monochrome OLED display. The conducted experiments demonstrate the typical U(t) curve and the triggering of the indicator at low charge levels (LOW − SoC ≤ 20% and CRITICAL − SoC ≤ 5%) in real-world conditions and the absence of unwanted switching of the state near the voltage thresholds.

1. Introduction

The miniaturization of hardware and the development of modern wireless communications have introduced a large number of applications in which compact measuring devices are powered by small lithium cells [1,2,3,4,5,6]. Such devices often operate continuously and perform monitoring tasks—environmental monitoring, device status monitoring, and key energy indicators, with a severely limited energy budget [2,7,8]. Lithium batteries are characterized by a nonlinear dependence of voltage on charge level and degrade over time. In [9,10], an estimation of lithium-ion battery State of Health is conducted using the methods of artificial intelligence. Inaccurate estimation of State of Charge (SoC) can lead to premature shutdown, data loss, or inefficient energy planning [2].

In the context of small, battery-powered systems, a lightweight, reusable architecture is needed for integrated measurement, visualization, and cloud telemetry that minimizes hardware complexity and energy footprint [11]. Existing solutions often rely on complex algorithms such as Extended Kalman Filter (EKF), which are accurate but require high resources [12]. This limits their applicability in Internet of Things (IoT) devices with low power consumption [7].

The literature review dedicated on battery State of Charge estimation shows that control observer-based [13] techniques are very useful and of great importance. The low computational complexity and reliability of control observers make them one of the most promising methods for the state estimation of Li-ion batteries (LIBs) in commercial applications and electrical vehicles.

With a small battery monitoring system built with a simplified architecture, static buffers, overwriting of the last measurement, and a look-up table (LUT)-based algorithm for SoC estimation, it is possible to achieve sufficient accuracy for applications requiring time-based monitoring with minimal hardware and power consumption [12]. The use of deep sleep mode [14] and reliable Wi-Fi connectivity [7] further optimize battery life and system maintenance. A new type of cyberattack [15] is the Energy Depletion Attack, which is a sub-type of attacks, targeting the battery of the IoT device. Information provided from the SoC estimation can be used in order to prevent this type of attack [16].

The objectives of present paper are given below:

- Design of a hardware configuration for measuring current and voltage with low self-energy consumption [17,18];

- Development of a software, driver, and control layer with clear interfaces [19];

- Implementation of an energy-efficient deep sleep mode and transition criteria [14];

- Qualitative compliance of the SoC with the typical lithium-ion shape of the voltage–time curve (U(t)) [20,21];

- Preparation of a methodological framework for future additions of SoC algorithm refinement.

2. Methodology and Requirements

The development follows an iterative methodological approach typical for embedded systems and IoT solutions [2,3,7]. The main stages include the following:

- Requirements definition—extraction of functional and non-functional criteria based on target scenarios, hardware constraints, and analysis of existing solutions;

- Architectural design—design of a modular architecture with clearly defined interfaces between hardware and software components;

- Modular implementation—development of individual drivers, services, and tasks in accordance with coding standards and documentation [19];

- Experimental evaluation—phased testing of the prototype with the possibility of dynamic configuration and optimization of parameters (measurement period, and energy consumption policy).

The requirements were collected through scenario analysis for Li-ion battery monitoring with periodic readings and cloud connectivity and good practices for low energy consumption [3,11]. Table 1 summarizes the functional requirements (F1–F8) for an embedded external battery monitoring system.

Table 1.

Functional requirements for an embedded external battery monitoring system.

Table 2 summarizes the non-functional requirements for an embedded external battery monitoring system.

Table 2.

Non-functional requirements for an embedded external battery monitoring system.

3. Hardware Topology and Implementation

3.1. Key Elements Selection

The present development covers current and voltage measurement, visualization, telemetry, and basic energy policy. Battery charging and long-term degradation are not taken into consideration. Thermal compensation is also not included [1,2]. Security is limited to Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure (HTTPS) protocol without mutual authentication and certificates [11].

The following assumptions are made in the presentation:

- A single-cell LIR2032 lithium-ion battery is used [1];

- The operation temperature is between 20 and 30 °C;

- A stable Wi-Fi connection to “Ubidots” is available [11];

- Battery parameters are pre-configured (Cutoff Voltage and maximum charge);

- No individual calibration of the INA219 is performed; nominal values are used [17,22].

The system has the following limitations:

- The SoC algorithm is LUT-based [12];

- No offline buffering and data resending [11] is conducted;

- There is no cryptographic protection of the local configuration;

- Latency depends on the Wi-Fi network [11,14].

These frameworks motivate the choice of the main components (ESP32-C6, INA219, and SSD1306) and the architectural trade-offs that are justified in the following sections.

The choice of hardware and software components is the result of a balance of accuracy, energy efficiency, implementation complexity, and future expansion [2,3,7]. The main components are as follows:

- ESP32-C6-DevKitC-1—a development board with a RISC-V core and integrated Wi-Fi 6 and Bluetooth Low Energy modules. The chip supports flexible power management [13] and provides sufficient hardware resources for processing and connectivity [18];

- INA219 current and power monitor—offers 12-bit accuracy and bidirectional current and voltage measurement via an I2C (Inter-Integrated Circuit) interface [17,22];

- SSD1306 OLED display (128 × 32)—a small, energy-efficient display for local data visualization [23];

- LIR2032 lithium-ion battery—a compact, rechargeable cell (~32 mAh), suitable for power-constrained IoT devices [1];

- “Ubidots” cloud platform—chosen for its integrated visualizations and telemetry API [11].

3.2. State of Charge Method

The chosen State of Charge (SoC) method is a look-up table (LUT) method based on the voltage–charge relationship [12,20]. It does not require per-instance calibration, complex temperature models, or current integration, which significantly reduces the computational cost and energy consumption—a key factor for energy-constrained IoT devices.

The chosen method is vulnerable to sensor measurement errors. Alternatives such as the Extended Kalman Filter (EKF) or the Coulomb Counter provide higher accuracy, but require significant computational resources and periodic calibration [20,24]. A combination of the approach used here with EKF, Coulomb Counter, and/or a simple PI/PID observer could minimize error drift, but computational resources will be needed and the power consumption will increase, which is critical for IoT devices.

The following sections discuss the system architecture and its physical development, with an emphasis on the functional connectivity between components, energy efficiency, and the ability to reliably calculate electrical parameters.

3.3. Architecture of the Developed System

The core of the system is the ESP32-C6 microcontroller, which manages communication and data processing. It exchanges information with two peripheral modules via the I2C interface:

- -

- Adafruit INA219 FeatherWing—a voltage measurement module that calculates current and power based on the voltage drop across the integrated shunt resistor and the bus voltage [17,22].

- -

- OLED SSD1306 display—visualizes the measured values and system states [23].

All components share a common ground (GND), and communication is carried out via a shared I2C bus for the INA219 and the OLED display. For communication stability in the current configuration, the built-in pull-up resistors of the ESP32-C6 DevKitC-1 are used. The tests performed show stable communication at a frequency of 200 kHz.

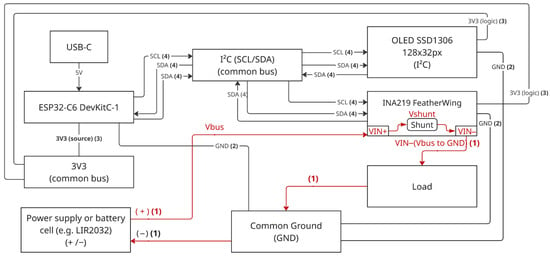

Figure 1 shows the connection of the ESP32-C6 DevKitC-1 with an OLED display and an INA219 sensor for measuring current, voltage, and power (in real time) in a high-side measurement.

Figure 1.

Block diagram of the developed IoT system.

The communication between the ESP32-C6 DevKitC-1, the INA219 FeatherWing [17,22], and the OLED SSD1306 display [23] is conducted via a common I2C bus, which minimizes pin assignment and simplifies wiring. In this configuration, the ESP32-C6 acts as a controller device, initiating data exchange and managing communication with the peripheral devices (INA219 and OLED display), which function as target devices.

The devices have the following factory I2C addresses:

- INA219: 0x40 hex [17];

- OLED SSD1306: 0x3C hex [23].

In Table 3, the hardware realization of the developed system and more specifically the connections toward the ESP32-C6 DevKitC-1 GPIO and the INA219 FeatherWing and the OLED SSD1306 display are shown.

Table 3.

Hardware and GPIO connections of the developed system.

Additionally, because the I2C lines are short, two 100 nF capacitors near sensor and display modules decouple the power circuit.

4. Software Design

The software design of the system follows a modular architecture with logical layering and clearly defined interfaces, with minimal interdependencies. The main goal is to achieve scalability, energy efficiency, and reliability when operating in resource-constrained IoT scenarios.

4.1. Architecture Overview

The software is implemented on ESP-IDF v5.4. for ESP32-C6 and uses FreeRTOS tasks and primitives for synchronization and data exchange [19]. Each functional block is encapsulated in a separate module with a public API (in the header file) and internal static functions (in the source file), which facilitates reuse and testing.

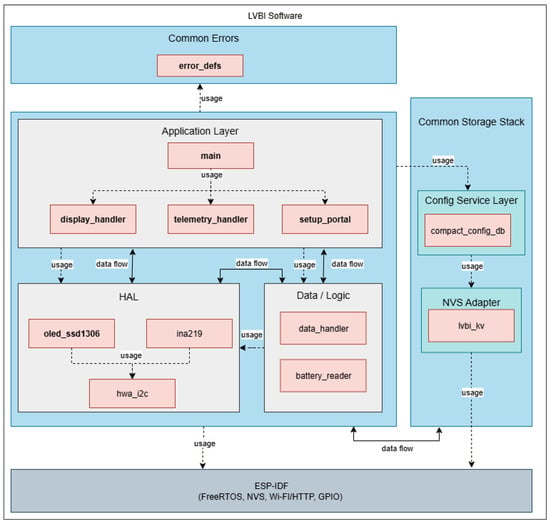

The architecture is logically divided into the following layers:

- Application Layer—main, display_handler, telemetry_handler, setup_portal;

- Data/Logic—data_handler, battery_reader;

- HAL (Hardware Abstraction Layer)—ina219, oled_ssd1306, hwa_i2c;

- Common Storage Stack:

- o Config Service—compact_config_db

- o NVS Adapter—lvbi_kv

- Common Errors—common definitions of flags/states: error_defs.

Data exchange between tasks is conducted via two FreeRTOS FIFO queues:

- A central sample queue with depth 1 and no stale data is accumulated, respectively; and there is a minimal RAM footprint;

- A separate display queue with limited depth for text/status messages and last valid sample;

The dependencies between modules are summarized in Figure 2.

Figure 2.

Simplified software layered architecture.

Initialization of INA219

For minimizing the complexity of the prototype, during the startup, the ina219 driver reads the calibration parameters (e.g., shunt_ohms) via compact_config_db and raises a flag in error_defs in case of missing/invalid values. This Hardware Abstraction Layer (HAL) → Config/Errors dependency is strictly limited to the initialization phase: after a successful startup, the parameters are kept locally in the driver and only measurements are performed in the runtime. This approach avoids additional parameter routing through intermediate layers, reduces code, and does not use cyclic dependencies or “runtime” access to Non-Volatile Storage (NVS).

4.2. Modular Organization of the Programming Code

The developed source code is provided in an author’s repository [25]. The project is organized modularly, with each functional block implemented as a separate component in the LVBI/components directory. Each component contains its own *.c and *.h files and a configuration file CMakeLists.txt, which defines the way the code is compiled, including directories and dependencies to other components. The main component of the application (main) is located in a separate directory LVBI/main/, outside of components, and serves as the entry point to the system.

This structure facilitates the maintenance, code reuse, and independent testing of each component, while providing clarity and control over the system build process.

Table 4 summarizes the roles and file structure (including the header-only components).

Table 4.

Description of the software components and files in the LVBI project.

The compact_config_db and error_defs components intentionally do not have .c files because they do not have their own state—they contain constants, types, bitmasks, and small static inline functions (bitwise operations and validation) or wrapper macros that the compiler embeds directly into the code for greater efficiency.

4.2.1. Software Component Compact_Config_Db

The compact_config_db software component is a facade to lvbi_kv (an NVS adapter) that centralizes the management of configuration keys and provides lightweight read/write interfaces without introducing additional dependencies when linking object files. This architecture allows efficient integration and simplifies access to configuration data. Both macro aliases and static inline helper functions are defined in the component, with each of the two techniques having their own purpose. Macros are used for direct 1:1 mapping to functions from lvbi_kv. This approach does not introduce additional overhead when linking object files and allows easy redirection to alternative internal logic when needed. On the other hand, static inline helper functions are used in cases where additional logic is needed—for example, setting default values, normalizing input data, checking for NULL values, and combining several operations into one. This approach provides type safety, single argument evaluation, ability to set breakpoints, and typically does not introduce any real execution overhead thanks to the direct inlining by the compiler.

4.2.2. Software Component Error_Defs

The error_defs software component provides a unified error notation used across all layers of the system. It defines a set of bit flags via an enum that describe various error and warning states specific to the subsystems—battery voltage, communication, sensors, display, and configuration. In addition, the component contains three compact static inline helper functions that are used when dealing with errors: setting (err_set), clearing (err_clear), and checking (err_test), implemented by bitwise operations on variables of type err_flag_t.

4.3. Tasks and Communication

The software architecture uses several tasks implemented in FreeRTOS that exchange data via queues and direct notifications with low latency. For transmitting measurements, the “last sample wins” strategy is applied, implemented using FIFO queues with depth 1. This allows eliminating the accumulation of stale data and optimizes RAM usage.

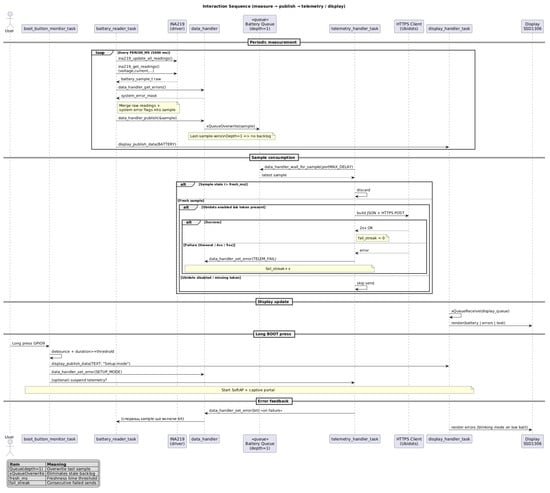

A simplified sequence of tasks and communication flows is graphically depicted in Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Simplified task sequence and communication flows in the LVBI project.

battery_reader_task—periodically calls the function ina219_update_all_readings(), retrieves a sample with measurements via ina219_get_readings(), and saves it in an appropriate structure that is with type battery_sample_t, containing the following elements: voltage_V, current_mA, power_mW, shunt_voltage_mV, soc_percent, errors, and timestamp. battery_reader_task also aggregates the system flags via data_handler_get_errors() and publishes the sample to the central monitor via data_handler_publish(&s). In parallel, it also sends a message of type DISPLAY_MSG_BATTERY to the display via display_publish_data(&msg).

telemetry_handler_task—blockingly waits for a new sample that is retrieved form the function data_handler_wait_for_sample(&rx, portMAX_DELAY). It discards “stale” samples by time (fresh_ms = 1000) and then packages and passes the data to the HTTPS Ubidots client. Failed attempts are counted (local fail_streak counter) and are handled via the data_handler_set_error(…) function.

display_handler_task—reads messages from its own queue (s_display_queue), which is filled by calling the display_publish_data(…) function and then displays the message on the OLED (SSD1306). This task supports logic for “refreshing” the data on the display (periodic switching of the text displayed on the display between two main types of messages—for text (including system errors) and for battery data).

boot_button_monitor_task—monitors for prolong holding of the “BOOT” button on the EPS32-C6-DevKitC-1 and, when pressed for a long time (more than 3 s), starts the device configuration mode (SoftAP + captive portal).

4.4. Power Management and Sleep Policy

The ESP32-C6 works in a cyclic way and has the following states: wakeup → measure → process → visualize/telemetry → deep sleep.

The data_handler_check_and_sleep(…) function in the data_handler component enables entering in a deep-sleep mode only if there are no active errors in the system and the condition (errors | s_system_errors) != 0 is met. Through compact_config_db, it reads from the Non-Volatile Storage (NVS) whether sleep is enabled in the configuration (sleep_en flag) and if so, reads the time interval (sleep_sec) during which the system should be in deep sleep mode. Also, it writes a flag that the display can be turned off, stops the Wi-Fi, and configures the internal RTC counter, through the esp_sleep_enable_timer_wakeup() function, using the read value (sleep_sec parameter), and calls the esp_deep_sleep_start() function. If the deep sleep mode is not enabled in the configuration, the system continues working in normal mode.

Power consumption in sleep mode is minimized by turning off the display and stopping the Wi-Fi [16]. For the developed system, a measurement of the deep sleep current has been conducted and the result shows the current is 8.2 µA.

Waking-up is performed via the internal Real-Time Clock (RTC).

Power consumption in normal mode (with the OLED display turned on and Wi-Fi enabled) is measured and the results show that the current for the ESP32-C6 is ~25 mA. The current for the OLED while streaming data and displaying text is ~21 mA and for the INA219, is ~1 mA. Therefore, the total current for the developed system is ~47 mA.

Keeping in mind that the power supply is 3.3 V, the evaluation of the energy-saving performance shows that the power consumption for normal mode is 155 mW and for the deep sleep mode, is 0.027 mW.

4.5. Error Handling

The error handling logic is centralized and implemented in the data_handler component. Each time the data_handler_publish(…) function is called, the data_handler merges current system flags (s_system_errors) with the current errors in each sample. The data_handler_get_errors() function provides s_system_errors to the calling components (telemetry_handler and display_handler) so that the display and telemetry reflect a consistent status.

4.6. Captive Portal and Wi-Fi Communication

A captive portal is a network mechanism in which newly connected clients to a Wi-Fi network are automatically directed to a local web page before being given access to the Internet or another service. Typically, the redirection is implemented through a local Domain Name System (DNS) response, where all domains are resolved to a single IP address, and/or through a Hypertext Transfer Protocol (HTTP) redirection, so that no matter which address or domain the user enters as destination, the configuration page is loaded. Most operating systems (Android, iOS, and Windows) often recognize such networks and display a built-in “Sign-in to network” window.

The current development does not automatically implement captive interception by the operating system: no local DNS is started with capturing all responses and no HTTP redirection is applied to the gateway. Therefore, Android, iOS, Windows, and macOS will usually not automatically open a captive window. The configuration page is accessed directly through a browser by the device address (e.g., http://192.168.4.1).

Wi-Fi Communication in Normal Operating Mode

The Wi-Fi communication [26] logic is implemented in the main component. After successful configuration, the Wi-Fi stack operates in Station (STA) mode, managed by the standard event cycle of the ESP-IDF platform. Registered handlers monitor the events WIFI_EVENT_STA_START, WIFI_EVENT_STA_CONNECTED, WIFI_EVENT_STA_DISCONNECTED, and IP_EVENT_STA_GOT_IP, and in case of connectivity loss, a limited number of retries are performed to obtain IP address via Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol (DHCP). If an IP address is obtained successfully, the HTTPS client for telemetry to the cloud is launched. If the failure continues, the device remains in local mode and displays a single error message, then proceeds to displaying data and other more critical errors. To save energy between transfers, a low-power Wi-Fi mode (Power Save) is activated, and communication to the cloud is protected via Transport Layer Security (TLS) by the built-in certificate package.

4.7. Drivers and Hardware Abstraction Layer

The hardware abstraction layer (HAL) is implemented through the hwa_i2c, oled_ssd1306, and ina219 modules. They provide robust public interfaces to the system bus, display, and measurement chip, so that the application logic does not work with addresses, registers, and timing parameters, but only with clear functions and structured data.

4.7.1. hwa_i2c Module

At the lowest level, hwa_i2c creates a single point of access to the Inter-Integrated Circuit (I2C) bus. In the current implementation, the I2C bus operates at a frequency of 200 kHz, using the General Purpose Input/Output (GPIO) pins of the ESP32-C6 microcontroller: pin GPIO5 for Serial Clock Line (SCL) and pin GPIO4 for Serial Data line (SDA). The choice of specific pins is consistent with the hardware configuration and the board layout.

The hwa_i2c module maintains a register of the devices by their name (e.g., “ina219” and “oled”) and associates them with their specific bus addresses—0x40 for INA219 and 0x3C for SSD1306. The implementation uses safe data access via FreeRTOS semaphore, retries for temporary errors, and unified error codes for the esp_err_t. In the event of a series of failures, the driver performs a controlled reinitialization to avoid locking up the system.

4.7.2. oled_ssd1306 Module

The driver for the oled_ssd1306 module encapsulates the control of a 128 × 32 OLED display on an SSD1306 controller at address 0x3C. The implementation includes an initialization sequence, clear and draw operations, and a sleep mode that is used before the system enters the deep sleep mode.

The driver operates in a direct data display mode, which does not use a global buffer. Instead of maintaining the entire screen content in RAM, pixel data is addressed and sent directly to the controller via I2C (pages and columns).

In the oled_ssd1306_init() function, the device registration is implemented via hwa_i2c_register_device(“oled”, OLED_ADDR) and also in the sending of a sequence of data for initialization of the display.

The oled_ssd1306_clear() function goes through all pages and before each one sets the address of a page/column, then sends a buffer of zeros (the first byte is a control byte 0x40 for data flow.

The oled_ssd1306_draw_text(uint8_t x, uint8_t y, const char *text) function positions the cursor (page/column) and for each valid character, extracts the 6-byte glyph from font6x8, forms a small buffer (control byte—0x40 + 6 bytes of data), and sends it via the hwa_i2c_write function. In case of an unsupported character, a warning is registered and a space is drawn. After each character, the x coordinate is shifted by six pixels.

The oled_ssd1306_sleep(bool enable) function sends a short command sequence to turn off and is on the panel and the built-in voltage converter.

For single commands, the internal oled_ssd1306_send_command(uint8_t cmd) is used, which forms an I2C packet with a control byte 0x00 (command stream). All transmissions go through the HAL layer: hwa_i2c_write(…) function.

4.7.3. ina219 Module

The INA219 driver communicates over I2C via hwa_i2c and provides initialization, calibration, and voltage/current reading functions. The device has an I2C address 0x40 and six main read/write registers according to the official documentation [17].

The initialization begins with registering the device via the hwa_i2c component and setting a standard configuration in REG_CONFIG (for 32 V range and 12-bit ADC mode). Then, dynamic calibration is performed according to the value of the shunt resistor R_shunt and the expected maximum current I_max.

The calibration register REG_CALIBRATION (0x05) is calculated by the formula:

where

is the resistance of the shunt,

is the current least significant bit, defined by (2)

Here, 0.04096 is an internal constant defined in the official documentation [17], ensuring correct scaling.

The current least significant bit is calculated by the formula:

where

is the maximum expected current,

n is the resolution of an analog-to-digital converter,

For the used ADC mode, n = 12.

The voltage on the shunt is calculated by the formula, multiplying by

where

is the value of REG_SHUNT_VOLTAGE register (0x01),

LSB (least significant bit) is the voltage of the least significant bit,

For the used mode, LSB = 10 µV.

The bits in the REG_BUS_VOLTAGE register (0x02) are not aligned according to the right alignment convention. To calculate the bus voltage value in volts, the value of the REG_BUS_VOLTAGE register must be shifted to the right by three bits. This shift places the BD0 bit in the LSB position so that the values can be multiplied by the for the bus voltage of 4 mV.

The driver uses the value from REG_SHUNT_VOLTAGE and applies Ohm’s law to calculate the current in amperes:

where

is the voltage on the shunt resistor,

is the value of the shunt resistor in Ohms.

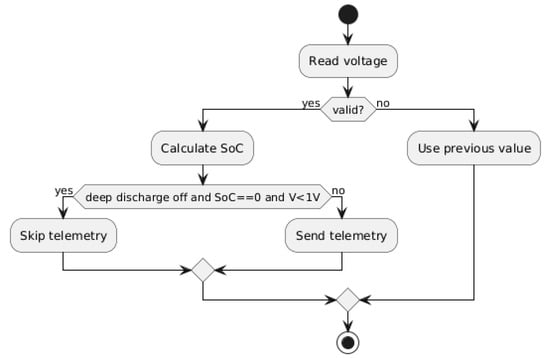

4.8. State of Charge (SoC) Evaluation Method

The State of Charge (SoC) evaluation is implemented based on the measured battery voltage and a look-up table (LUT) with linear interpolation.

The flow for the evaluation is shown in Figure 4. The driver reads the voltage from the INA219 and validates the conversion. If the result is invalid, the last value is used. The SoC is calculated, and telemetry publishing can be skipped depending on the user configuration (with the “deep discharge” option disabled/enabled). This sequence is implemented in ina219_read_voltage(…) and ina219_voltage_to_percent(…) and provides a lightweight, energy-efficient algorithm suitable for cyclical measurement tasks.

Figure 4.

Processing flow: read voltage → SoC evaluation → telemetry.

Reading and validating the voltage is conducted by checking the CNVR/OVF bits from the official documentation [17] and quick iterations. If the result is not valid, the previous value is kept. After a successful reading, a removed battery detection is activated and a software glitch filter is applied against single spikes in the measured values.

The SoC calculation is encapsulated in the ina219_voltage_to_percent() function. First, the input voltage is limited in the range from batt_cutoff to batt_full: at V ≤ batt_cutoff, the SoC result is 0%, and at V ≥ batt_full, the SoC result is 100%. If a valid LUT profile is available, CUSTOM or GENERIC (common profile for lithium-ion batteries) is selected. If the configured limits (batt_cutoff and batt_full) differ from (lut_min and lut_max), the voltage is scaled to the range of the table and then is linearly interpolated between adjacent points. If there is an absence of a valid table, a linear approximation between batt_cutoff and batt_full is used. The final SoC is constrained to the interval [0, 100] and rounded to the nearest integer.

The interpolation in the LUT is linear between adjacent points and returns an integer in percentage: when the CUSTOM profile is selected, the curve is specified as a string of “voltage–percentage” (V:P) pairs separated by commas (e.g., “3.30:0, 3.70:50, and 4.20:100”). The string is parsed in real time. For each pair, it removes the commas, extracts the numbers, and checks if the voltage is in the range [2.50, 4.35] V and the SoC is in the range [0, 100] %. The string must contain a mandatory increasing voltage and at least two valid points.

4.9. Low Battery Indicator

The low battery indicator is implemented as a three-state logic driven by the SoC (soc_percent) evaluated from the measured battery voltage. The three possible states are OK, LOW, and CRITICAL, with the current implementation using two fixed SoC thresholds: LOW level (at SoC ≤ 20%) and CRITICAL level (at SoC ≤ 5%). With each new measurement sample, the soc_percent is calculated and the indicator flags are immediately updated according to the current value. The indication uses two channels. Locally, a warning message is displayed on the OLED display for the LOW and CRITICAL battery states. Remotely, the states are published in the form of flags to Ubidots, which ensures monitoring and recording of events from a remote system. The flag definitions are centralized and type-safe, which allows uniform and compact handling in the individual modules (measurement, visualization, and telemetry).

The stabilization of the input data in the driver is conducted by a glitch filter (a filter for short-term disturbances and reaction to battery removal), which helps the stabilization of the indication at low and critically low battery charge. It is implemented in the ina219_read_voltage(…) function.

5. Experiments and Results

The experiments described in this section aim to validate the correct operation of the developed low charge indicator, the stability of the measurements, and the integration with cloud telemetry. A setup with a single-cell lithium-ion battery (LIR2032) was used to monitor the discharge behavior in real time.

The software measures the battery voltage via an Adafruit INA219 FeatherWing, validates the conversion (CNVR/OVF), and applies a glitch filter and logic for detecting a removed battery (after a series of low voltage samples). The SoC value is obtained from the voltage using a look-up table (LUT) method with linear interpolation. The indicator has two thresholds: LOW at SoC ≤ 20% and CRITICAL at SoC ≤ 5%. The flags are updated immediately according to the current sample. The states are visualized locally on the OLED display, and remotely (published to Ubidots) as numeric variables and flags. A single configuration was used for all experiments via the web portal “LVBI-Setup”.

The device is connected to the Wi-Fi network with the corresponding SSID and the password.

In the Ubidots section, a valid Token and Device Label, battery, are set so that the data is published to the same device in the cloud.

The following configuration was conducted via the web portal: in Sensor Calibration, Battery Voltage Range = 5.0 V, Max Expected Current = 50 mA, and Shunt Resistance = 0.1 Ω are selected. Max Expected Current and Shunt Resistance determine the calibration (CurrentLSB) of the INA219 and provide stable readings at low currents, while leaving sufficient margin within the permissible limits of the chip (bus voltage up to 32 V, shunt voltage, ±320 mV). The Battery Voltage Range parameter is only for visualization/scaling in the application layer and does not participate in the hardware calibration of the chip.

In Battery Parameters, a predefined Battery Type—GENERIC (1S Li-Ion) with the following voltages is used as follows: Full Voltage (V) = 4.2 V, Nominal Voltage (V) = 3.6 V and Cutoff Voltage (V) = 3.3 V. The capacity is set to 32 mAh. The Internal Resistance (Rint) field is 0 Ω; therefore, Open-Circuit Voltage (OCV) compensation is disabled. The Custom LUT field is empty and the SoC calculation uses the built-in GENERIC LUT with linear interpolation between the reference points. The Allow Deep Discharge Telemetry option is enabled, i.e., at deep discharge and very low voltage, data publishing is allowed for testing purposes. In Sleep Settings, the sleep mode is configurable and for the displayed measurements, it is set to disabled to ensure a continuous flow of samples to the display and to the cloud.

Both experiments discussed below are conducted at standard temperature conditions −25 °C (see Charge and Discharge Characteristics below) in order to validate the results with results [20] achieved by other authors.

5.1. Experiment 1: Battery Discharge and Error Triggering Mechanism

The purpose of this experiment is to demonstrate the typical U(t) curve and the triggering of the indicator at low charge levels (LOW − SoC ≤ 20% and CRITICAL − SoC ≤ 5%) in real-world conditions.

Method: The system monitors the continuous discharge of the LIR2032 from full charge to a value slightly lower than the Cutoff Voltage. In Ubidots, the voltage [V], current [mA], and SoC [%] are visualized over time and the moments of triggering of the indicator at low charge levels are marked.

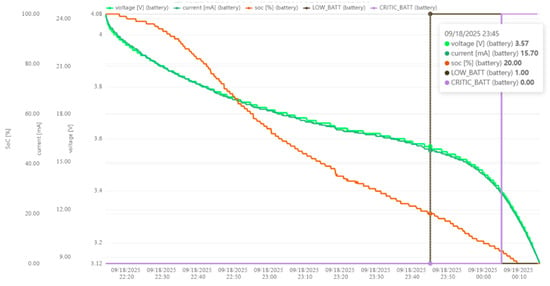

Figure 5 shows the graphical visualization of the complete discharge curve. The elements of the figure are as follows:

Figure 5.

Full discharge curve from Ubidots.

- Voltage [V] (light green);

- Current [mA] (green);

- SoC [%] (orange);

- Vertical marker (black line) indicating the moment of triggering the indicator at low charge level (LOW);

- Vertical marker (purple line) indicating the moment of triggering the indicator at critically low charge level (CRITICAL).

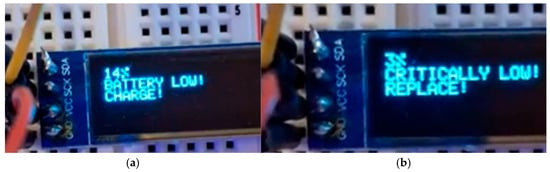

When the Low Voltage event occurs (SoC ≤ 20%), a warning message is displayed on the OLED display, and when the Critically Low Voltage event occurs, when SoC ≤ 5%, a warning message is displayed on the OLED display as shown in Figure 6.

Figure 6.

Warnings, displayed on the OLED: (a) Low Voltage event; (b) Critically Low Voltage.

Table 5 summarizes the main events of the experiment, with time of occurrence and the corresponding values of the included parameters.

Table 5.

Key events during the discharge.

5.2. Experiment 2: Stability near the Voltage Threshold Values

The objective of this experiment is to verify that the implemented threshold logic does not exhibit spurious or “unwanted” state switching in the vicinity of the low voltage limits. In this context, an unwanted switching event is defined as a repeated transition of the state flags back and forth across the same threshold (e.g., LOW → NORMAL → LOW) while the battery is operated in a quasi-static discharge regime.

In the proposed firmware, the state flags are driven exclusively by the state of charge (SoC) estimate exposed by the INA219 driver. The SoC is obtained from the measured terminal voltage via a strictly monotonic LUT (with linear interpolation as mentioned above) optionally combined with a bounded internal resistance compensation. On the measurement side, the INA219 is configured in an averaging ADC mode and augmented by a driver level glitch filter that rejects abrupt voltage steps larger than 0.15 V between consecutive samples. The sampling period in this experiment is 5 s, and the load current is approximately constant, so the underlying cell voltage evolves smoothly and predominantly in one direction.

The threshold logic in the battery reader component is therefore simple and transparent as follows: for SoC ≤ 5%, the CRITICALLY LOW flag is set and the LOW flag is cleared; for 5% < SoC ≤ 20%, the LOW flag is set and the CRITICAL LOW flag is cleared; for SoC > 20%, both flags are cleared. Under the above measurement and operating conditions, the filtered SoC trajectory becomes effectively monotonic, so each threshold (≈20% and ≈5%) is crossed at most once during the discharge.

Table 6 summarizes the main events observed in this experiment. During the time interval when the SoC passes through the Low Voltage region (≈20%, ~23:35–23:55) and subsequently through the Critically Low Voltage region (≈5%, ~23:55–00:10), the measured count of unwanted switching events remains zero for both thresholds. This confirms that, for the intended application regime (slowly varying load without aggressive dynamic current profiles), the combination of ADC averaging, voltage glitch filtering, and monotonic SoC mapping is sufficient to prevent chattering around the defined voltage thresholds.

Table 6.

Stability near the voltage thresholds (changing of the states).

In contrast, the count of unwanted switching could become non-zero under operating conditions that significantly violate the above quasi-static assumptions. For example, if the battery is subjected to highly dynamic current profiles with rapid charge/discharge steps near 20% or 5% SoC, the terminal voltage may oscillate around the corresponding LUT points, causing the estimated SoC to cross the thresholds multiple times. Similarly, a poorly conditioned or non monotonic user-defined SoC look-up table, or a measurement setup with substantial unfiltered electrical noise, could introduce artificial jitter in the SoC estimate around the threshold regions and thus lead to repeated LOW/NORMAL or CRITICAL/NORMAL transitions.

6. Discussion

The U(t) curve observed in the first experiment (see Figure 5) demonstrates the typical profile for a single-cell lithium-ion battery [27]: a long plateau in the middle range of the SoC, followed by a sharp drop in voltage when reaching low SoC values. This behavior is well documented for both LIR2032 type cells used in the conducted experiment and cylindrical energy cells such as 18,650 [28,29]. The official documentation of the LIR2032 [21,30] presents two main types of discharge process graphs: voltage versus time at standard temperature conditions (Charge and Discharge Characteristics, 25 °C) and voltage versus discharged capacity at different C-rates (Discharge Characteristics by Rate). In both cases, a plateau is observed, characteristic of the stable discharge phase, as well as a distinct transition zone—a transition point to an accelerated voltage drop, signaling the approach of the end of the useful capacity.

The results of the conducted experiment for discharging confirm the expected behavior of the developed indicator for low voltage: the low charge indication (LOW) is triggered at SoC ≈ 20% and V ≈ 3.57 V, while the indication for critical low charge (CRITICAL) is triggered at SoC ≈ 5% and V ≈ 3.40 V. Also, the experiment showed that at the Cutoff Voltage ≈ 3.30 V, the SoC reaches 0%. False alarms are not observed and this is in line with the validation and suppression of single voltage spikes in the driver. The duration between key moments (≈1 h 25 min to LOW, ≈20 min to CRITICAL, ≈4 min to 0%) are consistent with the expected dynamics of the LIR2032 at the specified load. The visualization in Ubidots provides clear traceability and correctly marks the moments of the alarms both in the graphs and in the published flags.

7. Conclusions

The present work demonstrates the process of design, implementation, and experimental evaluation of a single-cell lithium-ion battery monitoring prototype, intended for standalone operation or integration into other systems. The project integrates ESP32-C6-DevKitC-1, INA219 current and power monitor, and SSD1306 OLED display in a compact modular architecture with configurable parameters and a deep sleep mode, which is crucial for energy-constrained IoT scenarios [31]. The architectural solutions and the modular division of the software (HAL/drivers, services, error handling, and Wi-Fi/HTTP) are presented, respectively, in the hardware topology and implementation and software design sections.

The developed system combines the functional requirements for an embedded external battery monitoring system (according to the requirements in Table 1):

- Local voltage and current measurement;

- Approximate estimation of the State of Charge (SoC) using a look-up table (LUT) based on the discharge characteristic (voltage → SoC);

- Visualization on a monochrome OLED display (128 × 32, controller: SSD1306);

- Sending telemetry data to the “Ubidots” cloud platform via Wi-Fi.

The architecture is compact and energy efficient, with a reduction in complexity and memory usage: modular architecture with clearly distinguished responsibilities, avoidance of unnecessary dynamic memory allocations, centralized error handling, and a low-power policy through the usage of deep sleep mode. The data is stored in the “Ubidots” cloud platform, while a minimal storage is used locally for the “key-value” pairs for saving the configuration. No relational database is used.

Within the article, a limited qualitative assessment was performed, focusing on the basic concept and the operability of the system: qualitative compliance of the SoC with the typical lithium-ion voltage curve. The observations show sufficient accuracy for monitoring over time and a solid basis for subsequent improvement in accordance with the defined goals and constraints. The method for assessing the SoC is LUT-based (voltage → SoC) with linear interpolation, which allows for a simple and reliable implementation under limited resources. On top of this assessment, a two-state indicator with clearly defined thresholds is implemented as follows: LOW at SoC ≤ 20% and CRITICAL at SoC ≤ 5%, with the states being displayed both locally (on the OLED display) and remotely (telemetry data in the “Ubidots” cloud platform).

The development is applicable both for potential practical exploitation and for experimental and educational purposes—it provides tools for data interpretation (SoC assessment, telemetry, and visualization) and allows for subsequent analysis using the exported records in Comma-Separated Values (CSV), in accordance with usability and maintainability requirements.

The experimental part (real-world discharge) confirmed the expected behavior: correct triggering of LOW/CRITICAL states when reaching the thresholds and consistent visualization of telemetry in Ubidots. The obtained observations are within the target qualitative assessment and show sufficient suitability for monitoring over time.

As a future work, improvements could be conducted as follows:

- -

- Repeated experiments will be conducted in order to determine threshold stability and to verify it;

- -

- Repeated experiments will be conducted in order to validate the discharge curve as well as to estimate statistical errors;

- -

- Temperature compensation;

- -

- A combined SoC estimation algorithm (voltage + Coulomb Counter);

- -

- Secure over-the-air (OTA) software updates

- -

- Adaptive sampling profile; and,

- -

- Quality assessment.

Additionally, experiments will be conducted for acquiring more results against more dynamic scenarios, like some DST or FUDS, etc., and statistics will be created in order to estimate RMSE and MaxAE. The information about the State of Charge will be collected in order to be used by a machine learning algorithm [32], which will be used to prevent Energy Depletion cyberattacks. Also, the strongly nonlinear SoC conversion curve will be linearly compensated [33]. This would improve the accuracy, robustness, and usability without compromising the simplicity of the underlying architecture.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.V.H., R.I.T. and D.G.; methodology, A.V.H., R.I.T. and J.P.; software, D.G. and J.P.; validation, A.V.H., J.P. and D.G.; formal analysis, A.V.H. and D.G.; investigation, A.V.H. and J.P.; resources, D.G., R.I.T. and J.P.; data curation, A.V.H., J.P. and D.G.; writing—original draft preparation, A.V.H. and J.P.; writing—review and editing, A.V.H., J.P. and D.G.; visualization, A.V.H. and J.P.; supervision, D.G. and R.I.T.; project administration, A.V.H., R.I.T. and D.G.; funding acquisition, R.I.T. and D.G. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research is realized and funded under the scientific-research project № KΠ-06-ΠH97/47 “Exploring the possibilities of using artificial intelligence and simulation models to increase energy efficiency” by the contract KΠ-06-H97/11 with Bulgarian National Science Fund.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SoC | State of Charge |

| EKF | Extended Kalman Filter |

| LUT | Look-up Table |

| HTTPS | Hypertext Transfer Protocol Secure |

| I2C | Inter-Integrated Circuit |

| HAL | Hardware Abstraction Layer |

| NVS | Non-Volatile Storage |

| RTC | Real-Time Clock |

| DNS | Domain Name System |

| HTTP | Hypertext Transfer Protocol |

| DHCP | Dynamic Host Configuration Protocol |

| TLS | Transport Layer Security |

| GPIO | General Purpose Input/Output |

| SCL | Serial Clock Line |

| SDA | Serial Data line |

| LSB | Least Significant Bit |

| OCV | Open-Circuit Voltage |

| CSV | Comma-Separated Values |

References

- Espressif Systems. ESP32-C6 Technical Reference Manual. Available online: https://www.espressif.com/sites/default/files/documentation/esp32-c6_technical_reference_manual_en.pdf (accessed on 28 October 2025).

- Espressif Systems. ESP32-C6-DevKitC-1 Schematic v1.4. Espressif Systems. Available online: https://dl.espressif.com/dl/schematics/esp32-c6-devkitc-1-schematics_v1.4.pdf (accessed on 29 October 2025).

- Texas Instruments. Zerø-Drift, Bi-Directional Current/Power Monitor with I2C™ Interface. Available online: https://www.ti.com/lit/ds/symlink/ina219.pdf (accessed on 16 October 2025).

- Solomon Systech. SSD1306 OLED Display Controller Datasheet. Available online: https://cdn-shop.adafruit.com/datasheets/SSD1306.pdf#:~:text=SSD1306%20is%20a%20single-chip%20CMOS%20OLED%2FPLED%20driver%20with,is%20designed%20for%20Common%20Cathode%20type%20OLED%20panel (accessed on 20 October 2025).

- Espressif Systems. ESP32-C6-DevKitC-1 User Guide (Incl. Hardware Reference). Available online: https://docs.espressif.com/projects/esp-dev-kits/en/latest/esp32c6/esp32-c6-devkitc-1/user_guide.html (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Adafruit Industries. INA219 FeatherWing Product Documentation. Available online: https://learn.adafruit.com/adafruit-ina219-current-sensor-breakout (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Espressif Systems. ESP-IDF Programming Guide. Espressif Systems. Available online: https://docs.espressif.com/projects/esp-idf/en/latest/esp32/ (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Panasonic Industrial Devices. Technical Handbook—Lithium Batteries (Industrial Batteries for Professionals, Lithium). Available online: https://energy.panasonic.com/dam/master/pdf/eu/material/old/Panasonic_Batteries_Lithium-Handbook_2025.pdf (accessed on 15 October 2025).

- Chen, Y.; Huang, X.; He, Y.; Zhang, S.; Cai, Y. Edge–cloud collaborative estimation lithium-ion battery SOH based on MEWOA-VMD and Transformer. J. Energy Storage 2024, 99, 113388. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Y.; Duan, W.; He, Y.; Wang, S.; Fernandez, C. A hybrid data driven framework considering feature extraction for battery state of health estimation and remaining useful life prediction. Green Energy Intell. Transp. 2024, 3, 100160. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ubidots. Ubidots for Education—API Documentation. Available online: https://docs.ubidots.com/reference/welcome (accessed on 30 October 2025).

- Rasool, F.; Drieberg, M.; Badruddin, N.; Sebastian, P.; Qian, C. Electrical battery modeling for applications in wireless sensor networks and internet of things. Bull. Electr. Eng. Inform. 2021, 10, 1793–1802. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeed, M.; Khalatbarisoltani, A.; Deng, Z.; Liu, W.; Altaf, F.; Lu, S.; Hu, X. Comparative Analysis of Control Observer-Based Methods for State Estimation of Lithium-Ion Batteries in Practical Scenarios. IEEE/ASME Trans. Mechatron. 2024, 30, 3697–3709. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Iurilli, P.; Brivio, C.; Carrillo, R.; Wood, V. EISMOD: A DRT-based modelling framework for Li-ion cells. arXiv 2022, arXiv:2203.08515. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martínez, B.; Adelantado, F.; Bartoli, A.; Vilajosana, X. Exploring the Performance Boundaries of NB-IoT. IEEE Internet Things J. 2019, 6, 5702–5712. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hussein, H.; Aghmadi, A.; Abdelrahman, M.; Rafin, S.; Mohammed, O. A review of battery state of charge estimation and management systems: Models and future prospective. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. Energy Environ. 2024, 13, e507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Del-Valle-Soto, C.; Mex-Perera, C.; Nolazco-Flores, J.A.; Velázquez, R.; Rossa-Sierra, A. Wireless Sensor Network Energy Model and Its Use in the Optimization of Routing Protocols. Energies 2020, 13, 728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gupta, C.P.; Kumar, A. Wireless Sensor Networks: A Review. Int. J. Sens. Wirel. Commun. Control. 2013, 3, 25–36. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guangzhou Markyn Battery Co., Ltd. Li-ion Rechargeable Button Cell Specification. Available online: https://www.gmbattery.com/dl/cp11/li-ion/Button/LIR2032.pdf (accessed on 23 October 2025).

- Shenzhen Xingke Prof. Li-ion Battery Co., Ltd. LIR2032—Charge & Discharge Characteristics (25 °C), Discharge Characteristics (Rate), Discharge Characteristics in Different Temperature. Available online: https://nostris.ee/pdf/LIR2032.pdf (accessed on 25 October 2025).

- Kopylov, E.; Mizrah, E.; Fedchenko, A.; Lobanov, D. Study of a lithium-ion battery charge-discharge test unit characteristics. In Proceedings of the IOP Conference Series: Materials Science and Engineering, Surakarta, IN, USA, 18–19 October 2016. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lygte-Info, Battery Test 18650, Common Curves for All Tested Batteries. Available online: https://lygte-info.dk/review/batteries2012/Common18650CurvesAll%20UK.html (accessed on 27 October 2025).

- Hristov, A.; Vakadinova, V.; Trifonov, T. Using Arduino for Prototyping an Alarm System; CAx Technologies: Sofia, Bulgaria, 2016; pp. 27–31. ISSN 1314-9628. [Google Scholar]

- Saeed, M.; Lu, S.; Song, Z.; Hu, X. Integrated Framework for Accurate State Estimation of Lithium-ion Batteries Subject to Measurement Uncertainties. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2024, 39, 8813–8823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristov, V.; Hristov, A. Optimizing Packet Transmission Mechanism with Multipath Technologies. In Proceedings of the International Scientific Conference “Computer Science’2022”, Sofia, Bulgaria, 30 May–2 June 2022. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Butun, I.; Akyildiz, I. Low-Power Wide-Area Networks: Opportunities, Challenges, Risks and Threats; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hristov, A. Development of laboratory exercise “Cybersecurity of IIoT protocols”. In Proceedings of the 60th International Scientific Conference on Information, Communication and Energy Systems and Technologies—ICEST 2025, Ohrid, North Macedonia, 26–28 June 2025. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hinov, N. From Energy Efficiency to Energy Intelligence: Power Electronics as the Cognitive Layer of the Energy Transition. Electronics 2025, 14, 4673. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Stanchev, P.; Hinov, N. Comparative Techno-Economic and Life Cycle Assessment of Stationary Energy Storage Systems: Lithium-Ion, Lead-Acid, and Hydrogen. Batteries 2025, 11, 382. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nakov, O.; Lazarova, M.; Hinov, N. Advanced Technologies and Applications in Computer Science and Engineering. Electronics 2025, 14, 753. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Petrovic, J. LVBI (Low Voltage Battery Instrumentation). Available online: https://github.com/jpetrovic95/LVBI (accessed on 20 December 2025).

- Hristov, V.; Doichev, M.; Ismailov, A.; Pepedzhiev, D. Performance Analysis of Classical vs. Machine Learning-Based Image Segmentation Algorithms in a Java Web Environment. In Proceedings of the 2025 9th International Symposium on Multidisciplinary Studies and Innovative Technologies (ISMSIT), Ankara, Turkiye, 14–16 November 2025; pp. 1–8. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Woodward, S. Nonlinearities of Darlington Airflow Sensor and VFC Compensate Each Other. Available online: https://www.radiolocman.com/shem/schematics.html?di=659405 (accessed on 15 December 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.