Abstract

Metaphor is ubiquitous in daily communication and makes language expression more vivid. Identifying metaphorical words, known as metaphor detection, is crucial for capturing the real meaning of a sentence. As an important step of metaphorical understanding, the correct interpretation of metaphorical words directly affects metaphor detection. This article investigates how to use metaphor interpretation to enhance metaphor detection. Since previous approaches for metaphor interpretation are coarse-grained or constrained by ambiguous meanings of substitute words, we propose a different interpretation mechanism that explains metaphorical words by means of gloss-based interpretations. To comprehensively explore the optimal joint strategy, we go beyond previous work by designing diverse model architectures. We investigate both classification and sequence labeling paradigms, incorporating distinct component designs based on MIP and SPV theories. Furthermore, we integrate Part-of-Speech tags and external knowledge to further refine the feature representation. All methods utilize pre-trained language models to encode text and capture semantic information of the text. Since this mechanism involves both metaphor detection and metaphor interpretation but there is a lack of datasets annotated for both tasks, we have enhanced three datasets with glosses for metaphor detection: one Chinese dataset (PSUCMC) and two English datasets (TroFi and VUA). Experimental results demonstrate that the proposed joint methods are superior to or at least comparable to state-of-the-art methods on the three enhanced datasets. Results confirm that joint learning of metaphor detection and gloss-based interpretation makes metaphor detection more accurate.

1. Introduction

Metaphor, as a way of thinking and expression, makes language expression more vivid and plays an important role in daily communication. Metaphors arise when words are used to express another concept by mapping from their original concept [1,2]. Metaphors are frequently used in daily language, almost one in every three natural language sentences, which is evidenced by existing research on metaphor [1,3]. Therefore, metaphor detection, which targets identifying all metaphorical words in given texts, is considered as a significant task in Natural Language Processing (NLP). Additionally, to better understand metaphor, it is also necessary to study metaphor interpretation which aims at capturing meanings of metaphorical words, that is, using straightforward language that preserve the original meanings of provided texts to explain the metaphorical expressions [4].

Metaphor detection has attracted growing interest in recent years, prompting the development of various models for metaphor detection [5,6,7,8,9,10]. Among them, a considerable amount of work is based on Selectional Preference Violation (SPV) theory and Metaphor Identification Procedure (MIP) theory.

Both SPV theory [11] and MIP theory [3,12] are linguistic theories related to metaphor. SPV theory decides the metaphor of the target word by judging whether there is a semantic disparity between its literal meaning and its contextual semantic. While MIP theory is based on the contrast between the literal meaning of the target word and its practical meaning in context. Capturing contextual semantics more accurately can help identify metaphors better. However, existing works simply use the hidden layer encoding vector output by the encoder (Transformer, etc.) as the context semantic representation of the target word [6,13], but it is not enough to obtain the semantics only from the encoding vector. Therefore, it is necessary to obtain more semantic information and the metaphor interpretation may be an appropriate choice. This article simultaneously focuses on learning metaphor detection and interpretation to enhance the efficacy of identifying metaphors.

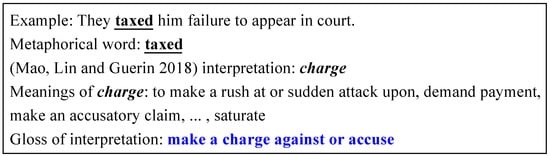

Present techniques in metaphor interpretation mainly concentrate on transferred attribute extraction, the production of literal substitute paraphrases, or underlying conceptual correlations detection [14]. However, these approaches remain constrained by the coarse-grained nature of metaphorical properties or the ambiguous connotations of the metaphorical substitute terms. As illustrated in Figure 1, taxed is a metaphorical term. While prior work [4] interprets taxed as charge, WordNet [15] assigns 25 distinct meanings to the latter. This semantic multiplicity makes it difficult to pinpoint the precise intended sense of taxed. As noted by [12], there is a critical distinction between the basic meaning of a word and its meaning in context. Specifically, the gloss-based interpretation of taxed shown in Figure 1—make a charge against or accuse—contrasts sharply with its basic meaning, levy a tax on. Unlike direct substitution, which can be ambiguous, the dictionary gloss provides a clearer interpretation that effectively distinguishes the contextual sense from the basic one. Consequently, the task of metaphor detection can be augmented by employing the technique of gloss-based metaphor interpretation.

Figure 1.

An example for metaphor detection and interpretation. Interpretation from the work [4] and interpretation based on glosses for the metaphorical word taxed are shown. nterpretation by a substitute word (highlighted in bold) is computed by [4]. Gloss as interpretation (highlighted in blue) is picked from the Merriam Webster dictionary.

In light of the above insights, we propose to explain metaphorical words by means of gloss-based interpretations. Specifically, we formulate the metaphor interpretation to select the optimal gloss from candidates. We utilize modern Word Sense Disambiguation (WSD) [16] methods for the metaphor interpretation, where WSD is a widely used technique to detect the right meaning of a target word. In addition to utilizing gloss interpretation, this article also introduces the part-of-speech (POS) tagging and external knowledge like ConceptNet to improve metaphor detection.

The work [5] formally divides the problem of metaphor detection into two types of tasks, classification and sequence labeling. Classification aims to determine if a particular word is metaphorical within a specific context, whereas sequence labeling aims to identify the metaphorical nature of each word in the provided sentence. Viewing metaphor detection as a classification task amplifies the characteristic of the target word. However, it is difficult to detect the continuous metaphorical expression, while it is more accurate for models with sequence labeling. Therefore, in order to explore the impact of gloss-based metaphor interpretation on metaphor detection, we design two different types of joint learning models for metaphor detection and interpretation, classification and sequence labeling.

The joint classification models focus on the given word, converting metaphor interpretation into a binary classification task, and carry out metaphor detection and interpretation simultaneously in the same context. Metaphor detection and interpretation tasks share semantic representation through the encoder. In practice, we design Pair-MIP and Pair-SPV based on the theories MIP and SPV, respectively. Additionally, there is also a model named Pair-MIP-SPV, which applies both theories. Unlike joint classification models, the joint sequence labeling models perceive metaphor detection as a sequence labeling problem and metaphor interpretation as a task that selects the most fitting gloss from candidates. Metaphor interpretation directly provides an interpretation semantic vector for metaphor detection and enhances the contextual semantics of words, which is quite consistent with MIP theory. Therefore, SEQ-MIP proposed in this article is a sequence-labeling model based on MIP theory. On account of the structure of SEQ-MIP, a two-stage joint model, SEQ-MIP-TSD, is proposed.

This work involves both metaphor detection and metaphor interpretation but there is a lack of datasets annotated for both tasks. To investigate whether gloss-based interpretation aids in metaphor detection, we improve three bench datasets: TroFi, VUA, and PSUCMC. We build a collection of candidate words for each dataset, and utilize glosses extracted from the dictionary to annotate these words. Experimental results on the aforementioned three improved dataset indicate that the metaphor detection is facilitated by gloss-based metaphor interpretation. On the VUA dataset and PSUCMC dataset, the joint sequence labeling models achieve the best experimental results, and on the TroFi dataset, the joint classification models achieve the best performance.

We summarize the main contributions in the following points.

- We propose a different interpretation mechanism that explains metaphorical words by means of gloss-based interpretations.

- We develop two types of joint learning models for metaphor detection and gloss-based interpretation: classification and sequence labeling, which empirically show that the joint learning of metaphor detection and gloss-based metaphor interpretation can improve the performance of metaphor detection.

- Three metaphor detection datasets are supplemented with additional annotations that include glosses for metaphorical words.

In contrast to our previous conference version [17], which only proposed a single sequence labeling model, this article extensively explores both classification and sequence labeling paradigms for the joint task. We go beyond simply changing the task formulation; we also investigate diverse model architectures and component designs based on MIP and SPV theories to capture metaphorical mechanisms from different perspectives. Furthermore, we incorporate Part-of-Speech tags and external knowledge to enhance the feature representation. Our experiments demonstrate that the gloss-based interpretation module effectively assists in improving the performance of metaphor detection.

The remainder of this paper is organized as follows. Section 2 provides an overview of relevant theories and existing approaches. In Section 3, we detail the architecture and working principles of the proposed joint learning models. Section 4 describes the experimental setup, including the enhanced datasets and evaluation metrics, followed by a discussion of the results, an ablation study, and case studies. Finally, Section 5 summarizes the paper and outlines directions for future work.

2. Related Work

2.1. Theories of Metaphor

There are three linguistic theories related to metaphor, including Selectional Preference Violation (SPV), Conceptual Metaphor, and Metaphor Identification Procedure (MIP) theory.

- SPV Theory Wilks [11] first proposed the SPV theory, which adds contextual information to the Selectional Preference model to judge the metaphor of the target word. A target word is metaphorical if there is a semantic difference between its literal meaning and its context, whereas the word is literal and non-metaphorical [11,18].

- Conceptual Metaphor Theory Lakoff and Johnson [19] proposed Conceptual Metaphor theory (CMT), which considers metaphors are words or other linguistic expressions that represent another concept from a more specific conceptual field. It posits that knowledge is transferred from a specific domain to an abstract domain, establishing a mapping between them.

- MIP Theory Similar to SPV theory, metaphor identification procedure theory is also based on contextual semantic [3,12]. If the literal meaning of a word contrasts with its meaning within the context, the word is considered metaphorical.

2.2. Metaphor Detection

Researches on metaphor detection have evolved significantly, ranging from feature-based methods to modern deep learning architectures. To clearly position our work among these diverse approaches, we summarize key studies in Table 1, comparing their formulations, features, and utilization of interpretation.

Table 1.

Summary of key approaches for metaphor detection.

- Methods Based on Semantic Features Early studies [25] suggested that the metaphoricity of words is related to their comprehension within sentences and their literal meanings, primarily based on the linguistics theories. Subsequently, a lot of semantic features were incorporated to enhance the performance of metaphor detection [26,27,28]. The work [29] investigated the dynamics of topic transition between the metaphorical word and its surrounding context. In the realm of multi-modal information processing, the study [30] integrated both word embeddings and visual embeddings for metaphor detection.

- Methods Based on Statistics Ref. [20] assumed that there is a special semantic pattern between metaphor and its dependence, constructed a metaphor tree based on the dependency relationship between ontology and metaphor body, and identified the metaphor by finding out the differences of trees based on statistical models. Ref. [21] proposed a classification method for metaphor detection based on conditional random field.

- Methods Based on Neural Models The advent of deep learning has significantly advanced metaphor detection. Wu et al. [13] introduced a model combining Bidirectional Long Short-Term Memory (Bi-LSTM) and Convolutional Neural Networks (CNNs), using Word2Vec for encoding and incorporating POS tags and word clusters. Ref. [5] categorized detection into classification and sequence labeling formulations. Building on this, Ref. [6] designed Bi-LSTM models utilizing GloVe and ELMo embeddings based on MIP and SPV. More recent work has explored complex architectures. Ref. [8] re-conceptualized detection as a reading comprehension task using pre-trained language models, while ref. [7] employed graph convolutional networks over dependency trees to leverage Word Sense Disambiguation knowledge. Ref. [9] proposed a linguistics-enhanced network, and ref. [10] introduced an explainable method focusing on token-level verb detection based on conceptual mappings.

- Methods on Chinese Datasets The research on metaphor detection in Chinese emerged relatively late, but a lot of achievements have been made. A metaphor sentiment labeling model [31] is proposed to construct a corpus of Chinese implicit emotion, which provides data support for automatic metaphor recognition in Chinese.

2.3. Metaphor Interpretation

Metaphor interpretation is a complex task, and deciphering the meanings conveyed by metaphorical expressions poses a significant challenge [14]. The existing approaches can be divided into three categories.

- Transferred Property Extraction The study [32] has formulated the problem of metaphor interpretation as an issue of attribute transfer extraction. It extracts intuitive attributes in both the source and target domains, and then extend these extracted attributes using synonymy relations from WordNet to search for metaphorical explanations.

- Re-conceptualization For the second category of approaches, metaphor interpretation is defined as the identification of latent conceptual mappings, with a primary focus on the reconceptualization of target domain concepts [33]. The work [34] provided certain contextual cues (such as the appearance of target domain concepts) and relevant metaphorical expressions for the interpretation of metaphors.

- Substitute Generation The final category formalizes interpretation as explaining metaphorical words via literal substitutes [4]. Studies [35] have employed corpus-parsed substitutes, hypernyms, or synonyms as candidates. The optimal explanation is typically selected as the candidate with the highest cosine similarity to the target word.

Due to the coarse granularity of metaphor interpretation or ambiguous explanations, the aforementioned methods are inadequate in precisely capturing the contextual meaning of metaphor. To address this issue, we propose an innovative explanation mechanism that utilizes glosses for metaphor interpretation.

2.4. Word Sense Disambiguation

The goal of word sense disambiguation is to determine the exact meaning of a word as it is used in a specific context [36]. This process is crucial for various NLP tasks, including information extraction [37] and machine translation [38].

- Knowledge-based WSD Knowledge-based methods [39,40,41] take advantage of the architectural features of semantic networks like BabelNet [42], or WordNet [43]. Knowledge-based methods, while offering comprehensive coverage in WSD, generally exhibit lower accuracy compared to other techniques.

- Traditional supervised WSD Traditional supervised WSD methods [44] utilize the manually engineered feature to train a special classifier for each polysemous word, i.e., word expert. Subsequent work also integrates word embeddings into this classifier [45]. However, these methods could be confused by the manually engineered features and training dataset.

- Neural-based WSD Neural-based WSD methods leverage encoders to achieve superior feature extraction [46,47]. BEM [48], which served as the inspiration for our proposed models, jointly encoded the target word along with its surrounding context and corresponding glosses by a bi-encoder. To consider semantic relation knowledge such as hypernyms, EWISER [49] and ESR [50] were proposed. More recently, more hybrid supervised and knowledge-based methods [51,52] greatly improves the performance of WSD.

3. The Proposed Joint Models

This section details the two main model classes we propose for metaphor detection and interpretation. Section 3.1 presents the joint classification models, while Section 3.2 describes the joint sequence labeling models.

3.1. The Joint Classification Models

Given a sentence s consisting of n words , , …, and a corresponding sequence of all candidate glosses for , the purpose of metaphor detection is to judge whether the word is metaphorical or literal in s. Additionally, we focus on identifying whether each gloss in can interpret the intended meaning of correctly for metaphor interpretation. The joint classification models convert both metaphor detection and interpretation into classification tasks. Therefore, we modify each example as sextuples . Clearly, s represents the given sentence, is the given word in s and is the part-of-speech of , and is the metaphor label of . Additionally, represents the j-th gloss in and if explains the contextual meaning of correctly, , and otherwise. The reason why POS tagging is introduced is that metaphor phenomenon appears more frequently in keywords of the text, and the part of speech of these keywords are verbs, nouns and adjectives in many existing cases.

Taking into account the established effectiveness of the pre-trained language model BERT [53] in various natural language processing tasks, we have chosen to employ the BERT model as our encoder. For each , we generate the input sequence as the following combination template:

where “[CLS]” and “[SEP]” are special tokens introduced in BERT. The sequence begins with the sentence context ss followed by the and the target word , providing the model with the syntactic and semantic environment of the metaphor candidate. The trigger word “means” acts as a bridge to prompt the model to predict the definition. The candidate gloss is placed after the “[SEP]” token, which allows the model to compute the attention score between the context and the gloss, thereby determining if the gloss is the correct interpretation of in the given context. An example is composed of the input sequence and the metaphor label , and the interpretation label . If a target word is metaphorical, then the metaphor label is metaphorical for all samples for .

3.1.1. Pair-MIP

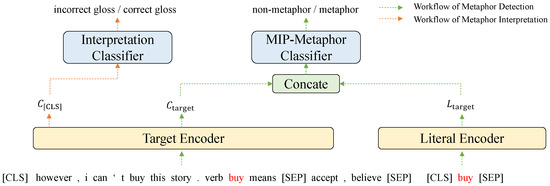

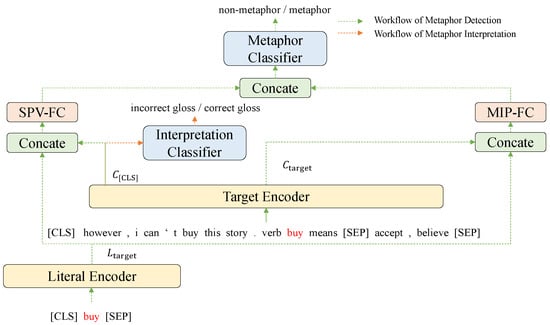

As shown in Figure 2, Pair-MIP is a joint metaphor detection and interpretation classification model based on the MIP theory. It is composed of two encoders and two classifiers. Both encoders are based on the pre-trained BERT. Additionally, both classifiers include a fully connected layer and a normalized exponential function decoder.

Figure 2.

The architecture of Pair-MIP joint model.

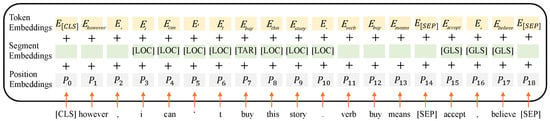

The target encoder serves both metaphor detection and metaphor interpretation. Taking the example in Figure 2, “buy” is the given target word. The input sequence of the target encoder is represented by the sum of three embeddings, including token embeddings, segment embeddings and position embeddings, as shown in Figure 3. Token embeddings and position embeddings are kept the same as BERT. Different from the setting of BERT, new tags are introduced in segment embeddings. To emphasize the target word, the tag for target words “[TAR]” is inserted into the embeddings [24]. The local context is a comma-separated clause containing the target word which is utilized in existing work [8,24]. In this paper, we also add the tag of local context “[LOC]” to enhance the semantic characteristics of the context. Additionally, the “[GLS]” tag is added to indicate the gloss corresponding to the word.

Figure 3.

The input embedding representation of Pair-MIP.

is the hidden vector of the token “[CLS]” from the last layer of the target encoder and , which corresponds to the hidden size of the encoder model used in this article. For metaphor interpretation, Pair-MIP utilizes to judge whether the gloss given in the input sequence is the correct contextual meaning of the target word. is passed through a fully connected layer, which is then followed by a softmax classifier. Then, the probability distribution of the interpretation classifier is obtained, and is formally defined as follows.

where and are learnable parameters. , where the predicted probability that the provided gloss is incorrect is denoted by , while represents the probability that the given gloss is correct.

The Pair-MIP model is designed based on MIP theory which involves two relevant meanings, contextual semantics and literal semantics. The literal encoder in Figure 2 is mainly used to produce a literal semantic representation. The input of the literal encoder is the target word. The target word T may be split into multiple tokens and we obtain a sequence of vector , where , through the literal encoder. By the mean-pooling method, the literal semantic vector is defined as follows:

The target encoder produces the context semantic representation of the target word in the same way with . Then, we concatenate and and put them into the MIP-metaphor classifier. The probability distribution is calculated as follows.

where and are learnable parameters. can be written as , where represents the probability that the target word is literal and represents the metaphorical probability.

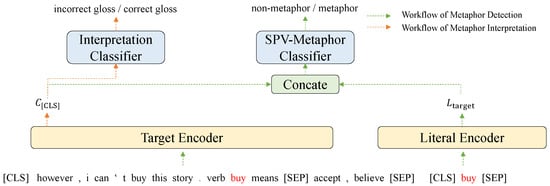

3.1.2. Pair-SPV

Pair-SPV based on the SPV theory has the same input and output as Pair-MIP. The core point of SPV theory is that there is a clear semantic contrast between the context and the literalness of the metaphorical word. As shown in Figure 4, instead of using , Pair-SPV directly uses to represent the concextual meaning. The difference between the framework of Pair-MIP and Pair-SPV is the input of metaphor classifier which is the basis of metaphor identification. Therefore, the metaphor probability distribution is defined as follows.

where and are learnable parameters. The processing of pair-SPV on metaphor interpretation is consistent with that of pair-MIP.

Figure 4.

The architecture of Pair-SPV joint model.

3.1.3. Pair-MIP-SPV

Figure 5 shows the basic structure of Pair-MIP-SPV. The interpretation classification of Pair-MIP-SPV is consistent with the two models mentioned above, while the metaphor detection task integrates information from both MIP theory and SPV theory. Both MIP-FC and SPV-FC are made up of a fully connected layer, defined as follows, respectively.

where , , , and are trainable parameters, , , and , .

Figure 5.

The architecture of Pair-MIP-SPV joint model.

Thus we utilize the vector and calculated from SPV-FC and MIP-FC to classify the metaphor. Similarly, we concatenate the two vectors, and then input them into metaphor classifier. We obtain the probability distribution .

where and are learnable parameters. is also composed of two dimensions.

3.1.4. Loss Function

The three joint classification models introduced in this section all accomplish two tasks simultaneously. Thus the optimization objective of the joint models also includes these two tasks. Due to both tasks are binary classification tasks, the design of the loss function is based on binary cross-entropy. Pair-MIP, Pair-SPV, and Pair-MIP-SPV differ only in model details, and their output remains exactly the same.

For i-th sample , the metaphor classification loss , where PMD refers to the metaphor detection task in the proposed Pair-MIP, Pair-SPV, and Pair-MIP-SPV models, is defined as follows:

where is the correct label, if the target word in i-th sample is literal or if the target word is metaphorical. , corresponding to the first dimension in , and , denotes the probability that the target word is literal. Additionally, is the second dimension in , and , is the probability that the target word is metaphorical.

The metaphor interpretation loss —where refers to the metaphor interpretation task in the proposed Pair-MIP, Pair-SPV, and Pair-MIP-SPV models—is defined as follows:

where is the correct label, if the gloss in i-th sample is incorrect for the target word or if the gloss is correct. Additionally, in the three joint classification models, each represents the probability that the gloss is wrong and , respectively represents the probability that the gloss is correct.

The total loss functionis defined as follows:

where q represents the number of samples. The models are trained on the candidate set built according to the glosses. Only samples belonging to the candidate set will be calculated for the loss value of metaphor interpretation. Indicator function if X is true and otherwise.

3.2. The Joint Sequence Labeling Models

Given a sentence s consisting of n words and a corresponding sequence of all candidate glosses , for any word and a gloss list with the length of for , for metaphor detection, we target on judging whether the word is metaphorical or literal in s, whereas metaphor interpretation focuses on acquiring the intended meaning of thorough choosing a gloss from .

Detecting metaphor generates a sequence of metaphor labels with the length of n, and each metaphor label represents the metaphorical prediction result of the corresponding word. Similarly, the output of metaphor interpretation is a sequence of glosses with the length of n, each of which corresponds to a predicted gloss of a word. This article proposes to jointly learn the metaphor interpretation task and metaphor detection task, which is actually to enhance the model’s capability to capture the semantics of words in specific contexts. The core idea of MIP theory is that there exists a huge difference between the semantic of words in context and their basic literal semantics. Therefore, the models proposed in this section are mainly designed based on MIP theory.

3.2.1. SEQ-MIP

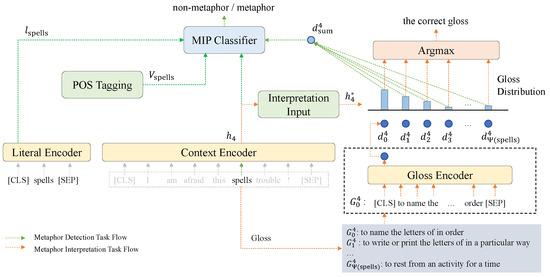

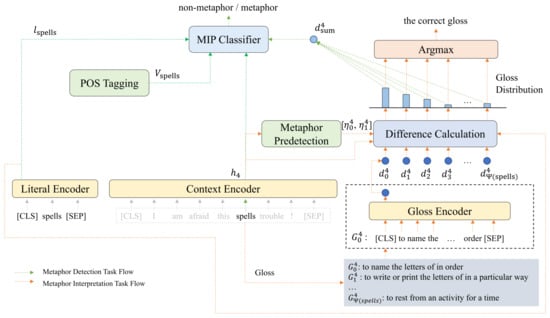

SEQ-MIP based on the MIP theory is a sequence labeling model shown in Figure 6. The underlying structure consists of three encoders, which encode context, gloss and word literal semantic, respectively.

Figure 6.

Overall structure of SEQ-MIP model. The gray text indicates the candidate glosses for the word “spell”.

According to the direction of the data flow, the results of metaphor detection are affected by the context, gloss, literal semantic, and part-of-speech tagging of the word, while metaphor interpretation is only affected by the context and gloss. In addition to the context semantic representation vector and literal semantic representation vector for metaphor detection based on the MIP theory, the interpretation semantic vector based on glosses, in Figure 6, is introduced to enhance context semantics. Additionally, metaphor interpretation and metaphor detection share a context encoder, which makes the semantics affected by the metaphor interpretation task also affect the metaphor detection task. Meanwhile, the correct gloss depends on context semantic representation vector of the word and gloss encoding vectors of the word. For each word in the input sentence, both metaphor detection and metaphor interpretation tasks should be carried out simultaneously.

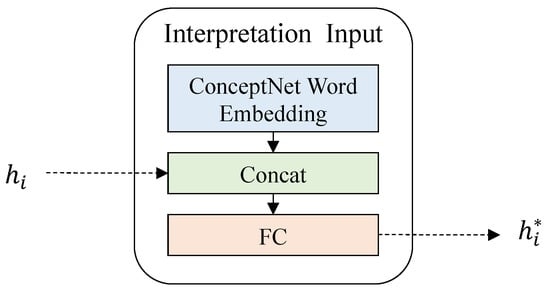

If we suppose in sentence s, then we denote the hidden vector of in the last layer as the context semantic representation vector of . There may be a few tokens for a word after tokenizing, the context semantic representation vector of can be obtained through mean-pooling processing, here as . The interpretation input module processes to produce the contextual semantic representation vector . There are two ways about the interpretation input module:

- = , that is, without any processing.

- The ConceptNet information [54] is integrated with the context semantic representation vector to obtain as shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7. The diagram of interpretation input module integrated with ConceptNet word embedding. The module FC denotes a fully connected layer.

Figure 7. The diagram of interpretation input module integrated with ConceptNet word embedding. The module FC denotes a fully connected layer.

The second approach integrates the external knowledge. In order to better understand the relationships between the target word and other words, we consider to utilize ConceptNet to build a more comprehensive and richer semantic representation. It calculates through combining with the ConceptNet word embeddings learnt from knowledge graph and distributed word representation vectors, which is defined as follows:

where represents the ConceptNet word embedding of , , and are learnable parameters and and .

In addition to , we utilize the gloss encoder to encode each gloss in and denote the vector of “[CLS]” as the semantic representation vector of the gloss . Thus, the set of gloss representation vectors are calculated. For different words, the size of their gloss set and the selection of glosses are different. Attention mechanism is a viable solution to such problem.Thus, we choose a gloss with the highest semantic relevance with the given context semantic of in metaphor interpretation. We define as the query and both keys and values correspond to the set of the gloss representation vectors.

According to the contextual semantic vector , we calculate the attention distribution of the gloss representation vectors, and denote it as the probability distribution of the correct gloss. Additionally, the probability that the gloss corresponding to is correct, is defined as follows.

The sum of all the correct probability of is 1. The gloss with the highest probability is considered as the correct gloss in metaphor interpretation module. Then, we obtain the interpretation semantic vector as follows.

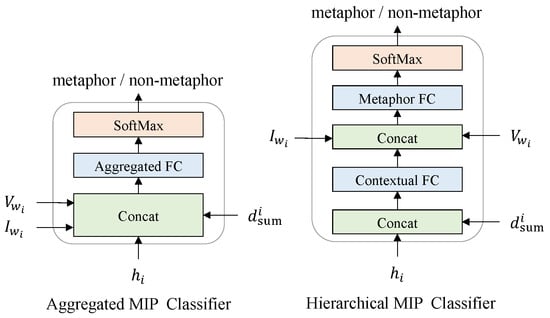

denotes the implicit semantic representation of interpretation, which can enhance the semantic information of the context. Thus, the proposed model can discriminate metaphor according to MIP theory. In Figure 6, the proposed SEQ-MIP introduces the part-of-speech tagging (POS tagging). POS tagging vectors are randomly initialized and each specific POS corresponds to a specific vector. Furthermore, all POS tagging vectors remain unchanged during model training. In this article, two simple implementations of MIP classifier are proposed, as Figure 8 shows.

Figure 8.

The structures of aggregated MIP classifier and hierarchical MIP classifier.

The first is an aggregated MIP classifier. We concatenate all inputs into a single, unified vector, which is subsequently fed through an aggregated fully connected layer for processing. The implementation process of aggregated MIP classifier can be summarized as follows.

where and where represents the length of the POS tagging vector. and are trainable parameters.

As shown in Figure 8, hierarchical MIP classifier first processes and to get an enhanced vector . Then is input into a full connection layer together with and . The process is defined as follows.

where , , , and are trainable parameters.

The metaphor probability distribution and are both two-dimensional. The first dimension represents the probability that is not metaphorical, while the second dimension represents the probability that is metaphorical.

The loss function of SEQ-MIP consists of two parts, metaphor detection and metaphor interpretation. For a word in s, its loss of metaphor detection is defined as follows.

where denotes the metaphor detection task of SEQ-MIP and the is the real label. Additionally, is corresponding to the first dimension of and , and is on behalf of the second dimension.

For the task of metaphor interpretation, the loss of is formulated as follows.

where signifies the metaphor interpretation task of SEQ-MIP and denotes the correct gloss of in s. SEQ-MIP is trained by minimizing the loss function of two tasks. Thus, the total loss of SEQ-MIP can be expressed as follows.

where n represents the number of words, and is the candidate set constructed for the interpretation task. Only words in need to be considered in the interpretation task training.

3.2.2. SEQ-MIP-TSD

Based on SEQ-MIP, we propose a two-stage joint model which is called SEQ-MIP-TSD. As Figure 9 shows, the part of metaphor detection basically remains unchanged compared with SEQ-MIP. The main difference exists in the interpretation task. In SEQ-MIP-TSD, the metaphor interpretation module is also directly affected by the metaphor pre-detection results, which makes two tasks closer.

Figure 9.

Overall structure of SEQ-MIP-TSD model.

There are two stages of metaphor detection, respectively, from metaphor pre-detection and MIP classifier in SEQ-MIP-TSD. Identification in the first metaphor detection stage only depends on the word and its given context.In SEQ-MIP-TSD, the interpretation task is directly affected by the results of metaphor pre-detection which is different from the traditional WSD. To refer to MIP theory that the meaning of a metaphor in a specific context is quite different from its literal meaning, this article proposes the following hypotheses:

- The representation vector corresponding to the correct gloss of a metaphor word diverges significantly from its literal semantic representation vector.

- The representation vector corresponding to the correct gloss of a non-metaphorical word exhibits a lesser degree of difference when compared to its literal semantic representation vector.

However, differences between vectors are difficult to describe numerically. Therefore, SEQ-MIP-TSD projects gloss representation vectors and literal semantic representation vectors into a specific vector space, such that the following is true:

- There exists the biggest difference between the representation vectors corresponding to a metaphor word’s correct gloss and its literal semantic representation vector.

- There exists the least difference between the representation vectors corresponding to a non-metaphorical word’s correct gloss and its literal semantic representation vector.

We can see that the biggest and least are related to the results of metaphor detection, which introduces a metaphor pre-detection module defined as follows.

where is of the form where represents the predicted probability that is to be interpreted literally, and denotes the probability that is metaphorical. and are learnable parameters. represents is metaphorical while represents is literal.

Because there are two situations corresponding to the biggest difference and the least difference, respectively, this article unifies the problems into the form of finding the biggest difference. The unification is realized by the difference calculation module which is composed of a coefficient function and a difference function through utilizing . The definition of is as follows.

where and are two hyper-parameters which used for scaling the value of the coefficient function and is a tiny constant. x equals . Due to , whether is positive or not is consistent with x.

In the hypothesis proposed in this article, the gloss and literal vectors need to be projected into a specific vector space. Metaphor is context-specific, and we utilize the vector from context encoder to project, which is formulated as follows.

where is the projection matrix, is the independent variable, and ∘ represents element-wise multiplication. Thus we can apply projection function to each gloss encoding vector and literal vector . After obtaining the projection vectors, the difference calculation module calculates the difference through the coefficient of function as Formula (24) shows. Formula (25) then normalizes the difference scores for all candidate glosses into the range [0, 1], representing the probability of each being the correct interpretation. Consequently, regardless of whether the target word is metaphorical or non-metaphorical, the gloss with the highest difference score is considered the most likely correct interpretation.

During training, the objective is to maximize the normalized difference score for the correct gloss. In the prediction stage, the correct gloss is with the highest normalized difference value. Taking the normalized difference value as the weight, the interpretation semantic vector is defined as follows.

The other parts of SEQ-MIP-TSD keep the same as SEQ-MIP and the MIP classifier produces the final results of metaphor detection, which is denoted as .

For in s, the loss function of SEQ-MIP-TSD consists of three parts: the loss function of metaphor detection , the loss function of metaphor interpretation and the loss function of consistency between two metaphor detection . The calculation of , where denotes the metaphor detection task of SEQ-MIP-TSD, defined as follow, is similar to .

where and are the output of MIP classifier.

Compared to in SEQ-MIP, ,where denotes the metaphor interpretation task of SEQ-MIP-TSD, maximizes the difference value between the projection vector of the correct gloss and the literal semantic , which is calculated as follows.

The SEQ-MIP-TSD model has two stages of metaphor detection. To ensure the consistency of the two stages of metaphor detection results, we compute as follows.

It is important to note that only when the results of the two stages of metaphor detection is not consistent, namely , will be considered. The SEQ-MIP-TSD model is trained by minimizing three loss function values, and the total loss function is shown in Formula (30) and denotes the two-stage joint model SEQ-MIP-TSD.

4. Experiments

In this section, we first introduce the datasets for evaluation and describe the process for enhancing them to support the gloss-based metaphor interpretation. By carrying out experiments on three augmented datasets, our proposed models outperform the existing model in metaphor detection on all datasets, proving that gloss-based interpretation can indeed help improve metaphor detection. Additionally, experimental results can also achieve considerable performance on the task of metaphor interpretation. In addition, we compare and analyze the influence of different types of models and different components on metaphor detection and metaphor interpretation.

4.1. Three Enhanced Datasets

The metaphor detection datasets TroFi and VUA, both in English, and PSUCMC, in Chinese, have been enhanced.

- Verb metaphors are labeled in TroFi [55]. Going along with the study [6], we consider unmarked words as literal words when training.

- The VU Amsterdam Metaphor Corpus (VUA) [3] is composed of fragments drawn from the British National Corpus. It annotates every word within the corpus in accordance with MIP theory. Our evaluation of models encompasses both the VUA ALL POS track and the VUA-Verb track.

- The PSU Chinese Metaphor Corpus (PSUCMC) [56,57] is composed of text samples from the Lancaster Mandarin Chinese Corpus that have been annotated for words related to metaphor based on MIPVU [3]. Every word within the PSUCMC is labeled, and we conduct our model assessments on the PSUCMC ALL POS track.

These datasets have been refined to aid in the task of metaphor interpretation with glosses. We utilize candidate set to term the words that require interpretation. In the TroFi dataset, all verbs that have been labeled are included in the candidate set. For the VUA dataset, the candidate set is compiled by randomly selecting verbs. In the PSUCMC dataset, a candidate set is constructed by randomly selecting words and then removing those that lack meaning. Human annotators have annotated the words in the candidate set.

For TroFi and VUA, annotators are directed to consult the Merriam–Webster dictionary https://www.merriam-webster.com/dictionary/ (accessed on 7 January 2026) to acquire the glosses for words in the candidate For PSUCMC, word glosses are obtained from the Baidu Dictionary https://dict.baidu.com (accessed on 7 January 2026). To ensure the quality of the annotations, we enlisted four annotators for each dataset. The annotators consist of linguistics experts, ensuring a solid understanding of semantic nuances. The annotation task involved selecting the most suitable gloss that reflects the contextual meaning of the target word. Each expert was required to annotate all instances across the three datasets. The entire annotation process was completed over a period of three weeks. The annotation process followed a strict quality-control procedure. First, the annotators independently annotated the assigned data. Following their individual annotations, they convened to discuss any discrepancies and finalized the annotations through consensus. To quantitatively assess the consistency of the annotations, we computed the kappa-score, a well-established metric in computational linguistics for evaluating inter-annotator agreement [58]. As shown in Table 2, the kappa-scores for each dataset indicate a high level of annotation reliability, confirming the dependability of our data. The samples are randomly allocated into training, validation, and test sets in a proportion of 8:1:1 for PSUCMC and TroFi. In the case of VUA, we still utilize data partitions provided by [6]. Table 3 provides an overview of the statistical information for all the datasets used in the experimental setup.

Table 2.

Kappa-score computed to assess the agreement of annotations within each dataset.

Table 3.

The statistics for the enhanced datasets are as follows. #sentences, #tokens, and #glosses denote the count of sentences, words that require detection, and samples that include gloss annotations, respectively; %M denotes the percentage of metaphors relative to the detected words.

4.2. Experimental Setup

4.2.1. Model Architectures and Pre-Trained Backbones

The models proposed in this article are built upon pre-trained language models. Specifically The Pair-MIP, Pair-SPV and Pair-MIP-SPV models proposed in this article all have a target encoder and a literal encoder, while SEQ-MIP and SEQ-MIP-TSD have three encoders: context encoder, annotation encoder and literal encoder. The above listed encoders are all based on the pre-trained language model. In practice, this article uses three basic pretrained language models: bert-base-uncased [53] and roberta-base [59] on the English datasets, and bert-base-chinese is used on PSUCMC dataset. In the same model, all the encoders adopt the same pretrained language model to ensure that different encoders are in the same semantic space before fine-tuning.

4.2.2. Model Variants

There are many different variants of the model proposed in this article. There are six variants of the joint classification model: Pair-MIP-R, Pair-MIP-B, Pair-SPV-R, Pair-SPV-B, Pair-MIP-SPV-R, and Pair-MIP-SPV-B, where R and B represent that encoders utilize roberta-base and bert-base-uncased, respectively. As for the joint sequence labeling model, there exist twelve variants according to different pre-trained models and different structures of interpretation input modules and MIP classifiers: SEQ-MIP-EQ(CNet)-Hie(Agg)-R(B) and SEQ-MIP-TSD-Hie(Agg)-R(B) where EQ and CNet represent the type of interpretation input module, Hie and Agg represent the type of MIP classifier.

4.2.3. Dataset Sampling Strategy for the Joint Classification Models

The dataset of the joint classification models is constructed according to the gloss set, which causes a large amount of data in the training set and the unbalanced distribution of labels. We randomly sample in all samples of each target word and select at most seven samples. If the target word is metaphorical, the sample that correctly interprets the target word must be included. The validation set and test set are not randomly selected. In the testing phase, each target word corresponds to multiple samples, and the strategy to decide whether a target word is metaphorical is: as long as the prediction result is metaphorical in one of the sample sets corresponding to the target word, the target word is metaphorical.

4.2.4. Training Settings

The POS tagging vectors in Equations (14) and (16) were randomly generated, and their dimension size is 100. The values of , and in Equation (21) were 1, 2, and , respectively. For training, we configured the learning rate at for PSUCMC and TroFi, and for VUA. We trained the models using a maximum of 5 epochs. A dropout probability of 0.2 was applied to the fully connected layer. Additionally, the maximum sequence length was established at 256 tokens. For the classification models, the batch size is for glosses, which was set to 512 in all three datasets. For the sequence models, the batch size refers to the number of samples, which was 32. Specifically, the model checkpoint that achieves the highest F1 score for metaphor detection on the validation set is preserved. This optimal model is subsequently used to evaluate performance on the test set.

4.2.5. Evaluation Metric

For the metaphor detection task, we utilize precison (P), recall (R), F1 score (F1), and accuracy (Acc) as our evaluation metrics. Additionally, we use Acc as the sole evaluation metric for metaphor interpretation. The sequence labeling model uses the accuracy I-Acc to evaluate the effect of metaphor interpretation. I-ACC represents the proportion of the number of samples that are correctly predicted to the number of samples that need to be explained. Since the metaphor interpretation of joint classification model is a binary classification mode, the evaluation metrics are consistent with that metaphor detection adopts. All reported numbers are expressed in percentages. We evaluate each word in the test set for metaphor detection. Though we can generate each word with glosses, metaphor interpretation is only evaluated for the words that are marked in the test dataset.

4.3. Compared Methods

For the purpose of comparative analysis, our proposed method is evaluated against the following previous approaches.

- CNN + RNNens [13] is a CNN-BiLSTM model. It uses Word2Vec to encode the text and CNN to encode the part-of-speech tag, word clustering and the word vector.

- SEQ [5] concatenates ELMo embeddings and GloVe embeddings into a Bi-LSTM network to to obtain contextual representations for each word.

- RNN_HG [6] is a sequence labeling model based on BiLSTM, designed according to the MIP theory. The model utilize ELMo and GloVe embeddings as input as well.

- RNN_MHCA [6] designs the model according to the SPV theory. It concatenates the vectors obtained from the multi-head attention mechanism with the contextual representation vectors.

- MUL_GCN [7], a graph convolutional neural network based on sentence dependency trees, constructs a multi-task learning framework for metaphor detection and WSD tasks.

- DeepMet [8] incorporates features such as POS tags and surrounding text into its input through utilizing RoBERTa [59]. For a fair comparison, we only match our models against DeepMet’s single model.

- ExampleBERT [22] is a model based on SPV theory. It first learns the general context information of the target word to fine-tune the metaphor detection.

- DefinitionBERT [22] is a classification model based on MIP theory, which introduces all glosses of target words to represent the literal meaning, and fuses the literal meaning with context representation vector.

- MrBERT [23] transforms the problem of metaphor detection into a problem of relation extraction. It models the target verb and its context, and resolves the relationship through Standford Dependency Parser [60].

- MelBERT [24] combines sentences and the POS tags as input samples and utilizes different position tags. The metaphor classification results of target words are obtained by combining MIP theory and SPV theory.

- BEM [48] is a WSD model that comprises two independent encoders. Both encoders are initialized from BERT based on the Transformer architecture.

- MDGI-Joint and MDGI-Joint-S [17] are models proposed in our previous conference version.

- MisNet [9] proposes a linguistics enhanced network inspired by MIP and SPV.

- WPDM [10] concentrates on the detection of metaphorical expressions at the token level and introduces an innovative explainable method called Word Pair based Domain Mining, which is influenced by conceptual metaphor theory.

For the VUA dataset, we present the results as reported in the published papers of the methods being compared. In the case of evaluating on the TroFi and PSUCMC, we utilize the publicly available code for certain compared methods. It is important to highlight that all the compared methods are designed exclusively for the English language domain. To facilitate the evaluation on PSUCMC, we employ ELMo embeddings that have been trained on the Xinhua portion of the Chinese Gigawords corpus https://github.com/HIT-SCIR/ELMoForManyLangs, (accessed on 7 January 2026) a resource released by Che et al. [61] and Fares et al. [62]. Additionally, we leverageword embeddings trained on the Chinese Wikipedia (zh-wiki) corpus https://dumps.wikimedia.org/zhwiki/latest/ (accessed on 7 January 2026) to replace the GloVe embeddings.

4.4. Experimental Results

4.4.1. Results for Metaphor Detection

- Comparison with previous approaches. Table 4 shows the result for metaphor detection. F1 score comprehensively reflects the false detection and missed detection of metaphor detection. Our proposed model achieves the highest F1 on all the datasets except for VUA ALL POS, which demonstrates the introduction of glosses improves the performance of metaphor detection. Although the integration of relational semantic features in MrBERT decreases the number of false detections, it simultaneously undermines the association of the target word with its surrounding context, resulting in a lower F1 score.

Table 4. Evaluation on the metaphor detection task. ‘-’ indicates no testing on that dataset. Bold indicates the best result for this metric.

Table 4. Evaluation on the metaphor detection task. ‘-’ indicates no testing on that dataset. Bold indicates the best result for this metric. - Analysis of Model Variants. The results of different variants proposed in this article are shown in Table 4. In our proposed different variants, the best F1 of the sequence labeling models is higher than that of the classification models on most datasets, which indicates sequence labeling models can better capture the connection between the target word and the context. The classification models carry out metaphor detection with each word as the center, thus obtaining a high recall rate. Additionally, for the classification models, RoBERTa performs better, while for the sequence labeling model, BERT performs better. For the sequence labeling models, the metric F1 of SEQ-MIP is superior to SEQ-MIP-TSD. Although the two-stage metaphor detection models can enhance the connection between metaphor detection and metaphor interpretation tasks, they will also cause error accumulation. What’s more, models without processing the input of metaphor interpretation don’t perform as well as models that incorporate ConceptNet embeddings in most cases, suggesting that models that incorporated ConceptNet knowledge perform better on the metaphor detection task. In addition, different structures of MIP classifiers have little effect on the overall performance.

4.4.2. Results for Metaphor Interpretation

- Comparison with previous approaches. Table 5 exhibits the experimental results of the joint sequence labeling models. We can conclude that the more complex the metaphor interpretation part of the model is, the worse the performance becomes. The worst performance is the two-stage joint model which introduces too many assumptions related to metaphor. However, the performance of the model with a relatively simple structure, such as the SEQ-MIP-EQ-AGG-B, is similar to that of the word sense disambiguation model BEM. The reason why models proposed in this article are worse than MDGI-Joint-S is that we pay more attention to using metaphor interpretation to improve metaphor detection, which reduces the performance of metaphor interpretation to some extent.

Table 5. Evaluation of the joint sequence labeling models on metaphor interpretation task. Bold indicates the best result for this metric.

Table 5. Evaluation of the joint sequence labeling models on metaphor interpretation task. Bold indicates the best result for this metric. - Analysis of Model Variants. Table 6 shows the results of the metaphor interpretation task in the joint classification models. From the results in the three data sets, the recall is much higher than the precision, which indicates that incorrect glosses are selected slightly more often than correct glosses are missed. According to the empirical results, the difficulty of the metaphor interpretation task in the VUA dataset is greater than that in the other two datasets. Pair-MIP-R achieves an F1 value of 37.8 on VUA, and Pair-MIP-SPV-B was the best model on PSUCMC dataset with the highest performance of all evaluation indicators. The pair-SPV-R is the best metaphor interpretation model on TroFi dataset. On both the VUA and PSUCMC datasets, the models with the best performance on the metaphor interpretation task are also the models with the best performance on the metaphor detection task in the joint classification models. As can be seen from Table 5, in the joint sequence labeling models, the performance of the models based on RoBERTa is significantly lower than those of BERT. Additionally, the models using hierarchical classifiers perform better than the models using aggregate classifiers on the interpretation task, which indicates that initial fusion processing of the contextual representation and the enhanced contextual semantic representation can reduce the impact on metaphor interpretation.

Table 6. Evaluation of the joint classification models on metaphor interpretation task. Bold indicates the best result for this metric.

Table 6. Evaluation of the joint classification models on metaphor interpretation task. Bold indicates the best result for this metric.

4.5. Ablation Study

To explore whether the different semantic features or model structures have a significant impact, we perform an ablation study on the PSUCMC dataset.

Table 7 shows the experimental results of the ablation on two semantic features, part-of-speech tags and [LOC] tags, of the joint classification models. The metaphor interpretation performance of Pair-MIP-B and Pair-SPV-B slightly has been improved after the POS tags are removed, while Pair-MIP-SPV-B significantly decreased. The Pair-MIP-SPV-B model decreases more on metaphor detection after removing the POS tags input than the other two models, which means that POS tags play a greater role in models that apply both theories simultaneously. As for the [LOC] tag, the performance of metaphor detection and metaphor interpretation of Pair-MIP-B and Pair-MIP-SPV-B models are significantly decreased after removing it. However, the performance of metaphor detection of Pair-SPV-B is slightly improved because the SPV theory pays more attention to the semantics of the global context. Emphasizing the local context weakens the semantic information of the global context. The last row gives the results of MelBERT. MelBERT, which applies MIP and SPV theories but excludes the metaphor interpretation task, can serve as a contrast to the classification joint models. Except that Pair-SPV-B is equal to MelBERT, the Pair-MIP-B and Pair-MIP-SPV-B models are better than MelBERT in metaphor detection, which implies that the metaphor interpretation does assist metaphor detection.

Table 7.

Ablation study of the joint classification models. P, R, F1 and Acc represent the metrics on metaphor detection. Additionally, I-P, I-R, I-F1 and I-Acc represent the metrics of the metaphor interpretation, respectively.

Table 8 shows the necessity of POS tags and the interpretation vectors in the joint sequence labeling models. After reducing the POS tags, the performance of metaphor detection of all models decreased significantly and the performance of metaphor interpretation task for all models improved slightly, except for SEQ-MIP-TSD-Hie-B. The coarse-grained POS tagging will bring some bias, which may bring errors to the more elaborate metaphor interpretation task. As observed from Table 8, the performance on metaphor detection decreases significantly after is discarded, which illustrates the importance of interpretation fusion representation vectors. As for the metaphor interpretation, except for the two-stage model SEQ-MIP-TSD-Hie-B, the performance of the other models does not increase or decrease significantly. What’s more, the last row of Table 8 presents the metaphor detection results of the SEQ-MIP-B model. SEQ-MIP-B is a model that completely removes the metaphor interpretation task; it concatenates the context representation vector obtained from the context decoder, the literal semantic representation vector obtained from the literal encoder, and the part-of-speech tagging vector. These are then input into a fully connected layer, where the classification results for metaphor detection are finally decoded via the Softmax function. As shown in Table 8, incorporating the metaphor interpretation task into the sequence labeling model for joint learning significantly improves the performance of metaphor detection, thereby verifying the necessity of the motivation proposed in this article.

Table 8.

Ablation study of joint sequence labeling models.

4.6. Case Study

The effectiveness and shortcomings of the two models proposed in this article are analyzed using three cases from the VUA dataset, as detailed in Table 9. There are no metaphorical words in the texts of case#2 and case#3, while there are three metaphorical words in the text of case #1, which are “stand”, “outside” and “this”. For comparison, we selected three cases that all contain the word “stand”. To provide a comprehensive view, we analyze and report the results of all the model variants in Table 10 for each case.

Table 9.

Three cases. Blue indicates metaphors or words explained in the gloss.

Table 10.

Case analysis results. Red represents errors.

According to the results of the case#1 in Table 10, under that the metaphor interpretation of all joint classification models are correct, the other five models can correctly predict all the metaphor words except Pair-MIP-R. Among the sequence labeling models that successfully predicted the metaphoricity of “stand”, most predicted the interpretation as “to take up or maintain a specified position or posture”. Since the interpretation differs significantly from the literal meaning of “stand”, these models were able to identify its metaphoricity. In contrast, the models that failed to predict “stand” as metaphorical all predicted the interpretation as “to support oneself on the feet in an erect position”, which is a literal interpretation. This indicates that the accuracy of interpretation prediction has a significant impact on metaphor detection. Additionally, both SEQ-MIP-CNet-Agg-B and SEQ-MIP-CNet-Hie-B incorrectly identified “with” as a metaphor. Observations from previous experimental results show that these two models have relatively high recall rates; therefore, the abundance of metaphorical words in the surrounding context may have influenced them, leading to the misclassification of “with” as metaphorical.

In case#2 and case#3, “stand” is used literally. However, the sentence length of case#2 is short, so there are certain challenges to detection. Four RoBERTa-based models Pair-MIP-R, SEQ-MIP-CNet-Hie-R, SEQ-MIP-CNet-Agg-R and SEQ-MIP-TSD-Agg-R all incorrectly detect “stand” as a metaphor. However, SEQ-MIP-CNet-Hie-R and SEQ-MIP-CNet-Hie-B models with the same model structure both detect “up” as a metaphor, indicating that in the case of short texts, the RoBERTa model-based models and the hierarchical model SEQ-MIP-CNet-Hie-R and SEQ-MIP-CNet-Hie-B that absorb ConceptNet word embeddings are more likely to misdetect metaphorical words.

In case#3, only two sequence labeling models, SEQ-MIP-EQ-Hie-R and SEQ-MIP-EQ-Hie-B, incorrectly identified ‘stand’ as a metaphorical word, whereas the other sequence labeling models accurately classified “stand” as literal. The reason why the classification-based joint models and the remaining sequence labeling joint models misidentified “at” as metaphorical is that “at” rarely appears in similar contextual contexts. Consequently, these models mistakenly classified it as metaphorical. This also demonstrates the effectiveness of the other sequence labeling models in this scenario.

The above three cases confirm the effectiveness of the proposed models in metaphor detection, and analyze the false detection situation of the models in short texts and that the performance of the detection task is affected by the imprecision of the interpretation task.

5. Conclusions and Future Work

Metaphor detection holds significant importance across various NLP applications. Considering metaphor interpretation can capture meanings of metaphorical words, we enhance metaphor detection through utilizing gloss-based metaphor. The innovation primarily resides in our interpretation methodology, which involves using glosses to explain metaphors. Accordingly, we propose different joint classification and sequence labeling models for metaphor detection and interpretation based on MIP and SPV theory. Furthermore, we have enriched three datasets within the metaphor detection to facilitate a comprehensive evaluation of our proposed joint models. Experimental results show that the combined model of metaphor detection and metaphor interpretation proposed in this article is superior to or similar to the state-of-the-art models, which indicates that the joint learning with gloss-based metaphor interpretation can improve the performance of metaphor detection.

Despite the promising results, our approach faces constraints regarding the scope of available gloss resources, as the model is restricted to selecting the best interpretation from a fixed dictionary set. While effective for conventional metaphors, this presents challenges for novel metaphors where the correct interpretation may not yet be recorded; future work could address this by integrating multiple external resources to expand the candidate gloss set. Additionally, our current training relies solely on annotated glosses, leaving unannotated data underutilized; we plan to explore semi-supervised learning to leverage this information.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, Y.L. and J.L.; methodology, Y.L., H.W. and J.L.; software, Y.L.; validation, Y.L., H.W. and J.L.; formal analysis, Y.L. and J.L.; investigation, Y.L.; resources, Y.L.; data curation, Y.L. and J.L.; writing—original draft preparation, Y.L.; writing—review and editing, Y.L., H.W. and J.L.; visualization, Y.L. and J.L. supervision, H.W.; project administration, H.W.; funding acquisition, H.W. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This article was supported by National Natural Science Foundation of China (No. 62276284, 62502554), Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation of Guangdong Province (No. 2023A1515011470, 2022A1515011355), Guangzhou Science and Technology Project (No. 202201011699), Shenzhen Science and Technology Program (KJZD2023092311405902).

Data Availability Statement

Data and code are available upon request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

Our experiments were conducted on an RTAI cluster, which is supported by School of Computer Science and Engineering as well as Institute of Artificial Intelligence in Sun Yat-sen University.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- Kövecses, Z. Metaphor: A Practical Introduction; Oxford University Press: Oxford, UK, 2002. [Google Scholar]

- Lagerwerf, L.; Meijers, A. Openness in metaphorical and straightforward advertisements: Appreciation effects. J. Advert. 2008, 37, 19–30. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steen, G.J.; Dorst, A.J.; Herrmann, J.B.; Kaal, A.A.; Krennmayr, T.; Pasma, T. A Method for Linguistic Metaphor Identification: From MIP to MIPVU; John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2010; Volume 14. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, R.; Lin, C.; Guerin, F. Word embedding and wordnet based metaphor identification and interpretation. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Melbourne, Australia, 15–20 July 2018; pp. 1222–1231. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, G.; Choi, E.; Choi, Y.; Zettlemoyer, L. Neural Metaphor Detection in Context. arXiv 2019, arXiv:1808.09653. [Google Scholar]

- Mao, R.; Lin, C.; Guerin, F. End-to-End Sequential Metaphor Identification Inspired by Linguistic Theories. In Proceedings of the 57th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Florence, Italy, 28 July–2 August 2019; pp. 3888–3898. [Google Scholar]

- Le, D.; Thai, M.; Nguyen, T. Multi-Task Learning for Metaphor Detection with Graph Convolutional Neural Networks and Word Sense Disambiguation. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020; pp. 8139–8146. [Google Scholar]

- Su, C.; Fukumoto, F.; Huang, X.; Li, J.; Wang, R.; Chen, Z. DeepMet: A Reading Comprehension Paradigm for Token-level Metaphor Detection. In Proceedings of the 2nd Workshop on Figurative Language Processing, Online, 9 July 2020; pp. 30–39. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Liu, Y. Metaphor Detection via Linguistics Enhanced Siamese Network. In Proceedings of the 29th International Conference on Computational Linguistics (COLING), Gyeongju, Republic of Korea, 12–17 October 2022; pp. 4149–4159. [Google Scholar]

- Tian, Y.; Zhang, R.; Xu, N.; Mao, W. Bridging Word-Pair and Token-Level Metaphor Detection with Explainable Domain Mining. In Proceedings of the 62nd Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Bangkok, Thailand, 11–16 August 2024; pp. 13311–13325. [Google Scholar]

- Wilks, Y. A Preferential, Pattern-Seeking, Semantics for Natural Language Inference. Artif. Intell. 1975, 6, 53–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Group, P. MIP: A Method for Identifying Metaphorically Used Words in Discourse. Metaphor. Symb. 2007, 22, 1–39. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, C.; Wu, F.; Chen, Y.; Wu, S.; Huang, Y. Neural Metaphor Detecting with CNN-LSTM Model. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Figurative Language Processing, New Orleans, LA, USA, 6 June 2018; pp. 110–114. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, S.; Chakraverty, S. A survey on computational metaphor processing. Acm Comput. Surv. 2020, 53, 1–37. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Miller, G.A. WordNet: A lexical database for English. Commun. ACM 1995, 38, 39–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kilgarriff, A. How Dominant Is the Commonest Sense of a Word? In Proceedings of the International Conference on Text, Speech and Dialogue, Brno, Czech Republic, 8–11 September 2004; Volume 3206, pp. 103–112. [Google Scholar]

- Wan, H.; Lin, J.; Du, J.; Shen, D.; Zhang, M. Enhancing Metaphor Detection by Gloss-based Interpretations. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistic: ACL-IJCNLP, Online, 1–6 August 2021; pp. 1971–1981. [Google Scholar]

- Wilks, Y. Making Preferences More Active. Artif. Intell. 1978, 11, 197–223. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lakoff, G.; Johnson, M. Metaphors We Live By; University of Chicago Press: Chicago, IL, USA, 1980. [Google Scholar]

- Hovy, D.; Shrivastava, S.; Jauhar, S.K.; Sachan, M.; Goyal, K.; Li, H.; Sanders, W.E.; Hovy, E.H. Identifying Metaphorical Word Use with Tree Kernels. In Proceedings of the First Workshop on Metaphor in NLP, Atlanta, GA, USA, 13 June 2013; pp. 52–56. [Google Scholar]

- Rai, S.; Chakraverty, S.; Tayal, D.K. Supervised Metaphor Detection using Conditional Random Fields. In Proceedings of the Fourth Workshop on Metaphor in NLP, San Diego, CA, USA, 17 June 2016; pp. 18–27. [Google Scholar]

- Su, C.; Wu, K.; Chen, Y. Enhanced Metaphor Detection via Incorporation of External Knowledge Based on Linguistic Theories. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: ACL-IJCNLP, Online, 1–6 August 2021; pp. 1280–1287. [Google Scholar]

- Song, W.; Zhou, S.; Fu, R.; Liu, T.; Liu, L. Verb Metaphor Detection via Contextual Relation Learning. In Proceedings of the 59th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics and the 11th International Joint Conference on Natural Language Processing, Online, 1–6 August 2021; pp. 4240–4251. [Google Scholar]

- Choi, M.; Lee, S.; Choi, E.; Park, H.; Lee, J.; Lee, D.; Lee, J. MelBERT: Metaphor Detection via Contextualized Late Interaction using Metaphorical Identification Theories. In Proceedings of the 2021 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Online, 6–11 June; pp. 1763–1773.

- Shutova, E.; Sun, L.; Korhonen, A. Metaphor Identification Using Verb and Noun Clustering. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Beijing, China, 23 August 2010; pp. 1002–1010. [Google Scholar]

- Turney, P.D.; Neuman, Y.; Assaf, D.; Cohen, Y. Literal and Metaphorical Sense Identification Through Concrete and Abstract Context. In Proceedings of the 2011 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Edinburgh, Scotland, UK, 27–31 July 2011; pp. 680–690. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, H.; Moon, S.; Jo, Y.; Rosé, C.P. Metaphor Detection in Discourse. In Proceedings of the 16th Annual Meeting of the Special Interest Group on Discourse and Dialogue, Prague, Czech Republic, 2–4 September 2015; pp. 384–392. [Google Scholar]

- Bulat, L.; Clark, S.; Shutova, E. Modelling metaphor with attribute-based semantics. In Proceedings of the 15th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Valencia, Spain, 3–7 April 2017; pp. 523–528. [Google Scholar]

- Jang, H.; Jo, Y.; Shen, Q.; Miller, M.; Moon, S.; Rosé, C.P. Metaphor Detection with Topic Transition, Emotion and Cognition in Context. In Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Berlin, Germany, 7–12 August 2016; pp. 216–225. [Google Scholar]

- Shutova, E.; Kiela, D.; Maillard, J. Black Holes and White Rabbits: Metaphor Identification with Visual Features. In Proceedings of the 2016 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, San Diego, CA, USA, 12–17 June 2016; pp. 160–170. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, D.; Lin, H.; Yang, L.; Zhang, S.; Xu, B. Construction of a Chinese Corpus for the Analysis of the Emotionality of Metaphorical Expressions. In Proceedings of the 56th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Melbourne, Australia, 15–20 July 2018; pp. 144–150. [Google Scholar]

- Su, C.; Tian, J.; Chen, Y. Latent semantic similarity based interpretation of Chinese metaphors. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2016, 48, 188–203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Semino, E. Descriptions of pain, metaphor, and embodied simulation. Metaphor. Symb. 2010, 25, 205–226. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Martin, J.H. A corpus-based analysis of context effects on metaphor comprehension. Trends Linguist. Stud. Monogr. 2006, 171, 214. [Google Scholar]

- Shutova, E.; Van de Cruys, T.; Korhonen, A. Unsupervised metaphor paraphrasing using a vector space model. In Proceedings of the COLING 2012: Posters, Mumbai, India, 8–15 December 2012; pp. 1121–1130. [Google Scholar]

- Navigli, R. Word sense disambiguation: A survey. Acm Comput. Surv. 2009, 41, 1–69. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ciaramita, M.; Altun, Y. Broad-coverage sense disambiguation and information extraction with a supersense sequence tagger. In Proceedings of the 2006 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Sydney, Australia, 22–23 July 2006; pp. 594–602. [Google Scholar]

- Gonzales, A.R.; Mascarell, L.; Sennrich, R. Improving word sense disambiguation in neural machine translation with sense embeddings. In Proceedings of the Second Conference on Machine Translation, Copenhagen, Denmark, 7–11 September 2017; pp. 11–19. [Google Scholar]

- Bevilacqua, M.; Maru, M.; Navigli, R. Generationary or “How We Went beyond Word Sense Inventories and Learned to Gloss”. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Online, 16–20 November 2020; pp. 7207–7221. [Google Scholar]

- Scozzafava, F.; Maru, M.; Brignone, F.; Torrisi, G.; Navigli, R. Personalized PageRank with Syntagmatic Information for Multilingual Word Sense Disambiguation. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics: System Demonstrations, Online, 5–10 July 2020; pp. 37–46. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, M.; Wang, Y. A Synset Relation-enhanced Framework with a Try-again Mechanism for Word Sense Disambiguation. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing (EMNLP), Online, 16–20 November 2020; pp. 6229–6240. [Google Scholar]

- Navigli, R.; Ponzetto, S.P. BabelNet: The automatic construction, evaluation and application of a wide-coverage multilingual semantic network. Artif. Intell. 2012, 193, 217–250. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Magnini, B.; Strapparava, C.; Pezzulo, G.; Gliozzo, A.M. The role of domain information in Word Sense Disambiguation. Nat. Lang. Eng. 2002, 8, 359–373. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shen, H.; Bunescu, R.C.; Mihalcea, R. Coarse to Fine Grained Sense Disambiguation in Wikipedia. In Proceedings of the Second Joint Conference on Lexical and Computational Semantics (*SEM), Volume 1: Proceedings of the Main Conference and the Shared Task: Semantic Textual Similarity, Atlanta, GA, USA, 13–14 June 2013; pp. 22–31. [Google Scholar]

- Iacobacci, I.; Pilehvar, M.T.; Navigli, R. Embeddings for Word Sense Disambiguation: An Evaluation Study. In Proceedings of the 54th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Berlin, Germany, 7–12 August 2016. [Google Scholar]

- Kågebäck, M.; Salomonsson, H. Word Sense Disambiguation using a Bidirectional LSTM. In Proceedings of the Workshop on Cognitive Aspects of the Lexicon, Osaka, Japan, 11–17 December 2016; pp. 51–56. [Google Scholar]

- Raganato, A.; Bovi, C.D.; Navigli, R. Neural sequence learning models for word sense disambiguation. In Proceedings of the 2017 Conference on Empirical Methods in Natural Language Processing, Copenhagen, Denmark, 7–11 September 2017; pp. 1156–1167. [Google Scholar]

- Blevins, T.; Zettlemoyer, L. Moving Down the Long Tail of Word Sense Disambiguation with Gloss Informed Bi-encoders. In Proceedings of the 58th Annual Meeting of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Online, 5–10 July, 2020; pp. 1006–1017. [Google Scholar]

- Bevilacqua, M.; Navigli, R. Breaking Through the 80% Glass Ceiling: Raising the State of the Art in Word Sense Disambiguation by Incorporating Knowledge Graph Information. In Proceedings of the Conference-Association for Computational Linguistics, Online, 5–10 July 2020; pp. 2854–2864. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; Ong, X.C.; Ng, H.T.; Lin, Q. Improved Word Sense Disambiguation with Enhanced Sense Representations. In Proceedings of the Findings of the Association for Computational Linguistics: EMNLP, Online, 7–11 November 2021; pp. 4311–4320. [Google Scholar]

- Conia, S.; Navigli, R. Framing Word Sense Disambiguation as a Multi-Label Problem for Model-Agnostic Knowledge Integration. In Proceedings of the 16th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Main Volume, Online, 19–23 April 2021; pp. 3269–3275. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, G.; Lu, W.; Peng, X.; Wang, S.; Kan, B.; Yu, R. Word Sense Disambiguation with Knowledge-Enhanced and Local Self-Attention-based Extractive Sense Comprehension. In Proceedings of the COLING, Gyeongju, Republic of Korea, 12–17 October 2022; pp. 4061–4070. [Google Scholar]

- Devlin, J.; Chang, M.; Lee, K.; Toutanova, K. BERT: Pre-training of Deep Bidirectional Transformers for Language Understanding. In Proceedings of the 2019 Conference of the North American Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics: Human Language Technologies, Minneapolis, MN, USA, 2–7 June 2019; pp. 4171–4186. [Google Scholar]

- Speer, R.; Chin, J.; Havasi, C. ConceptNet 5.5: An Open Multilingual Graph of General Knowledge. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, San Francisco, CA, USA, 4–9 February 2017; pp. 4444–4451. [Google Scholar]

- Birke, J.; Sarkar, A. A Clustering Approach for Nearly Unsupervised Recognition of Nonliteral Language. In Proceedings of the 11th Conference of the European Chapter of the Association for Computational Linguistics, Trento, Italy, 24–29 March 2006; pp. 329–336. [Google Scholar]

- Lu, X.; Wang, B.P. Towards a metaphor-annotated corpus of Mandarin Chinese. Lang. Resour. Evaluation 2017, 51, 663–694. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nacey, S.; Dorst, A.; Krennmayr, T.; Reijnierse, W. Metaphor Identification in Multiple Languages: MIPVU Around the World; John Benjamins Publishing Company: Amsterdam, The Netherlands, 2019; Volume 22. [Google Scholar]