A Machine Learning-Based Ultra-Wideband Microstrip Antenna for Microwave Imaging Applications

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Literature Review

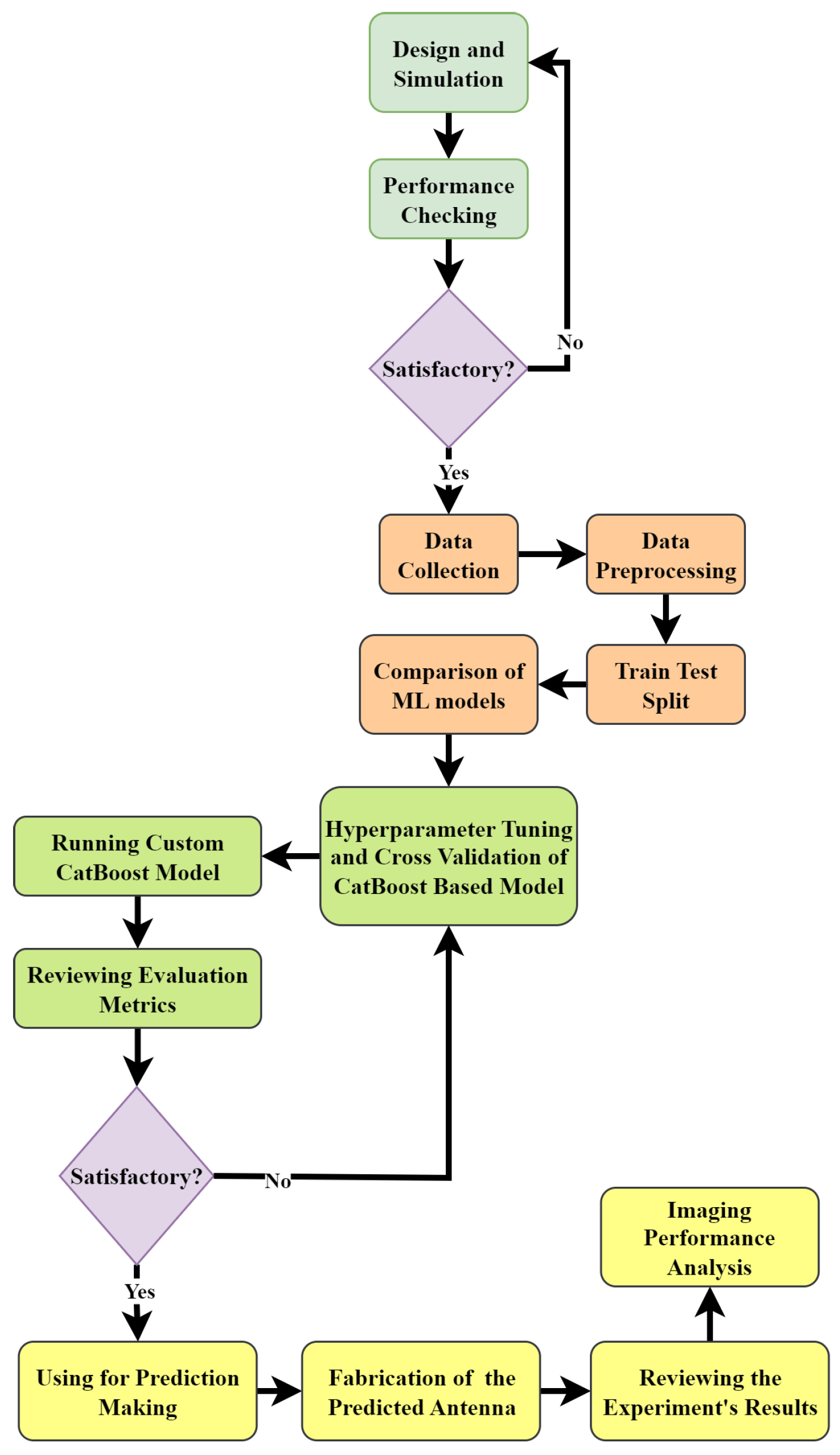

3. Methodology

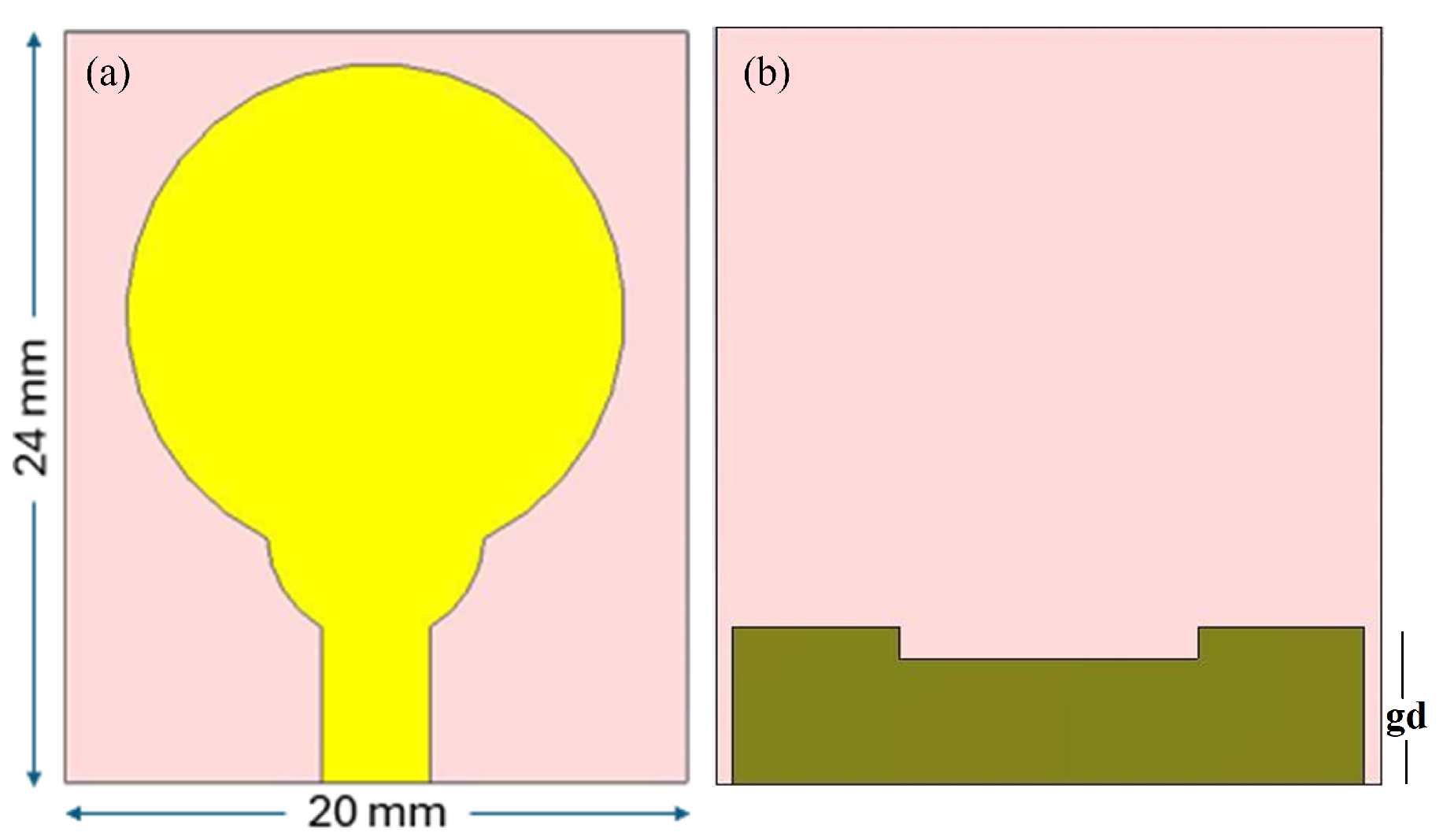

3.1. Antenna Design

3.2. Data Collection and Preprocessing

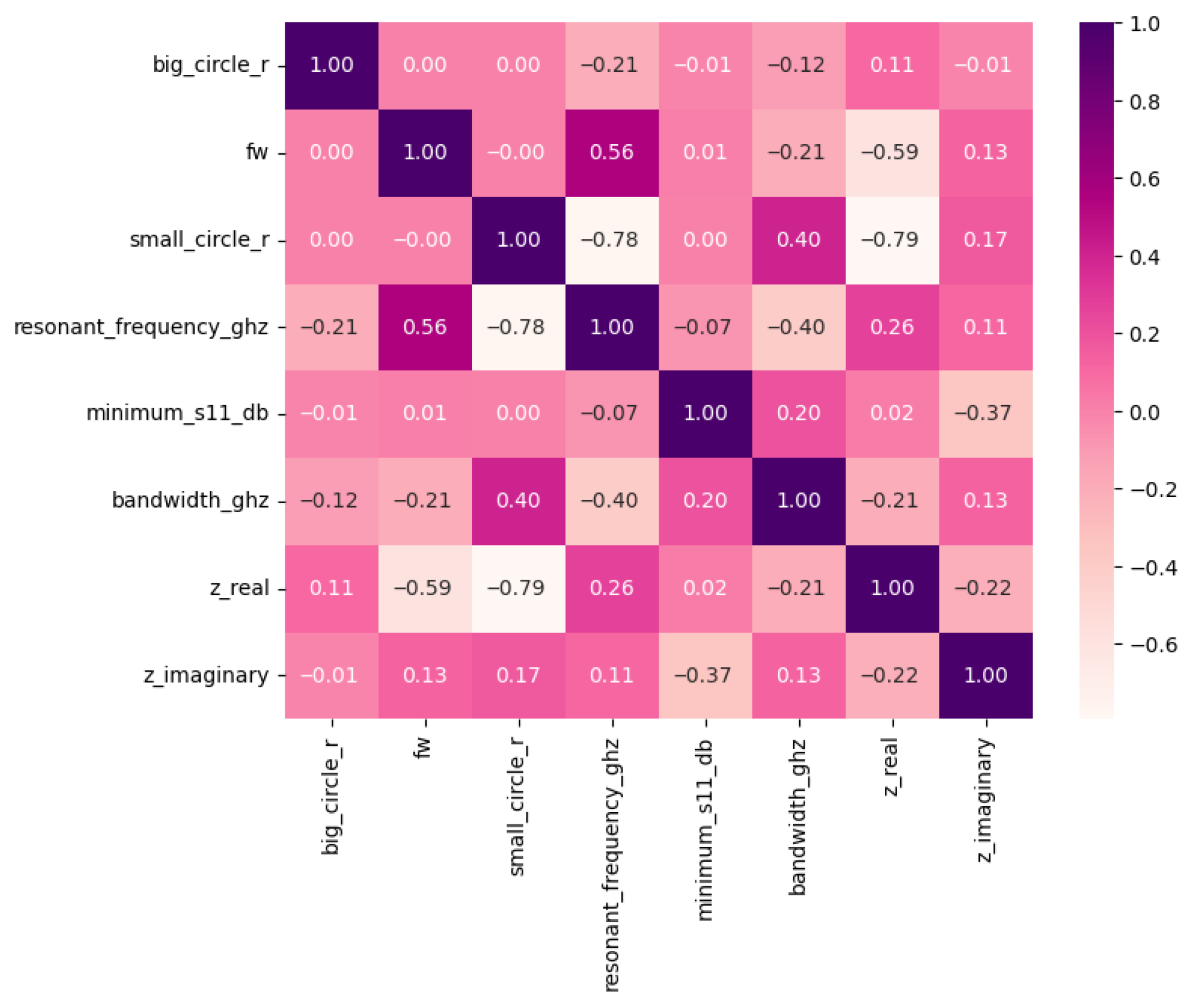

3.3. Correlation Matrix Analysis

3.4. Model Selection and Training

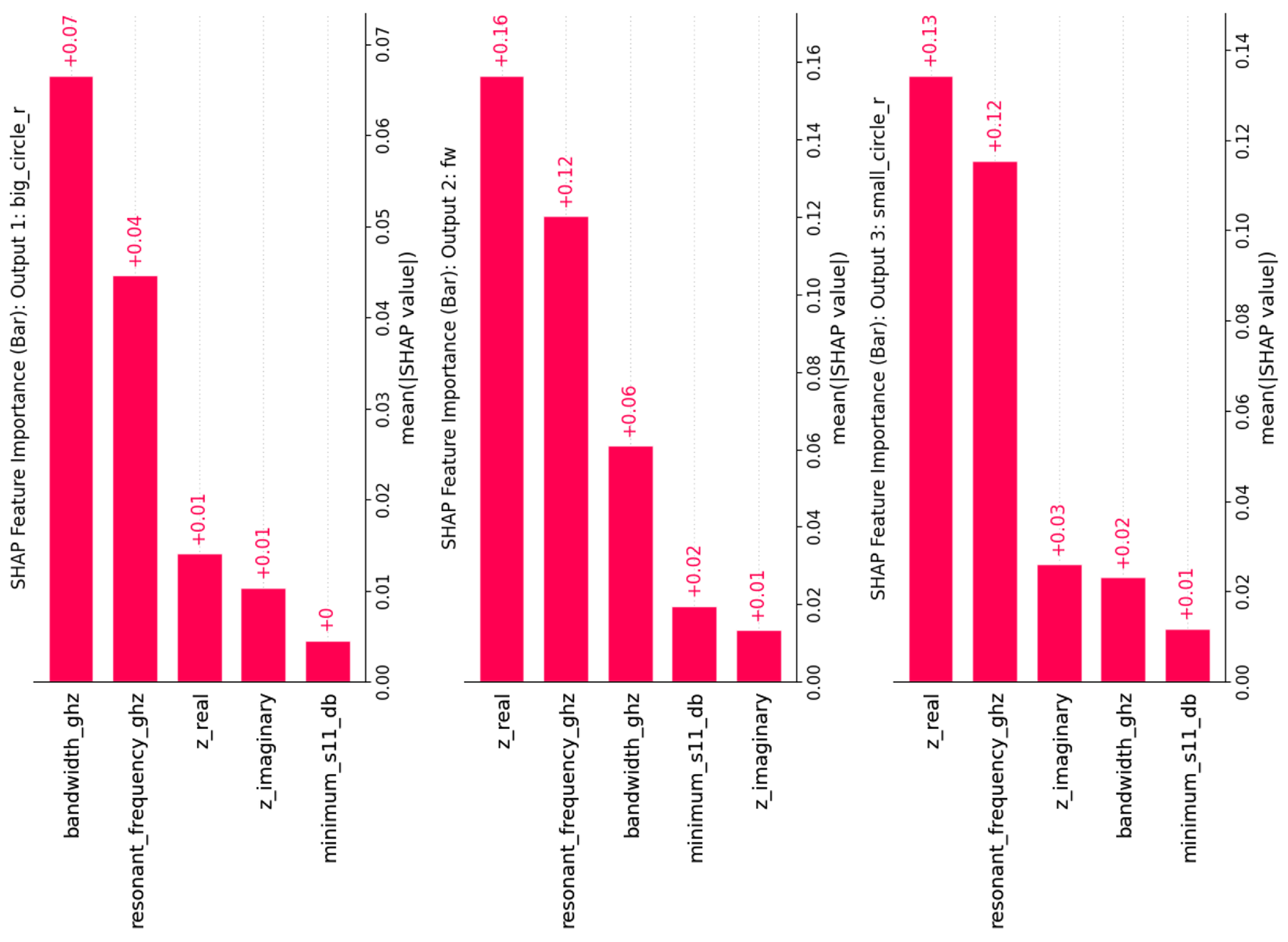

3.5. Explainable AI

4. Results and Discussions

4.1. Performance Metrics

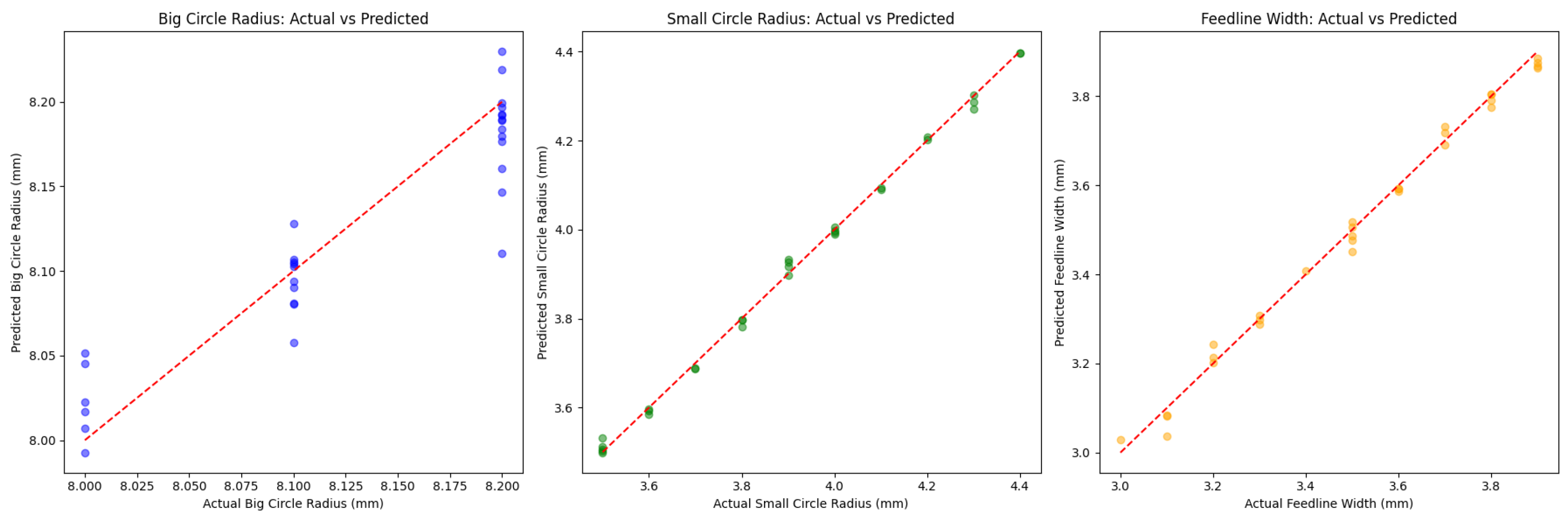

4.2. Quantitative Results

4.3. Comparison with Other Models

4.4. Feature Importance Analysis

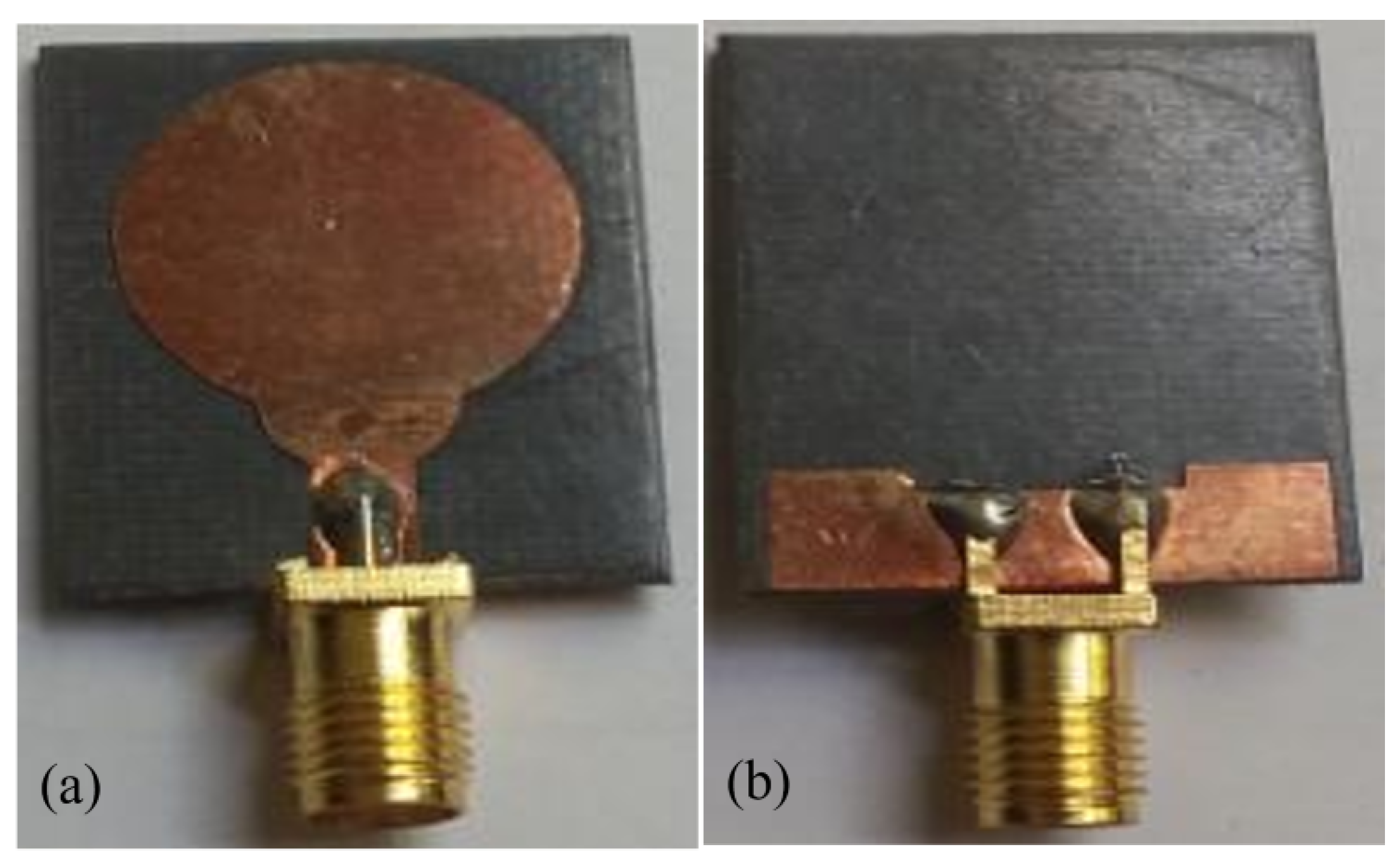

4.5. Fabrication of the Proposed Antenna

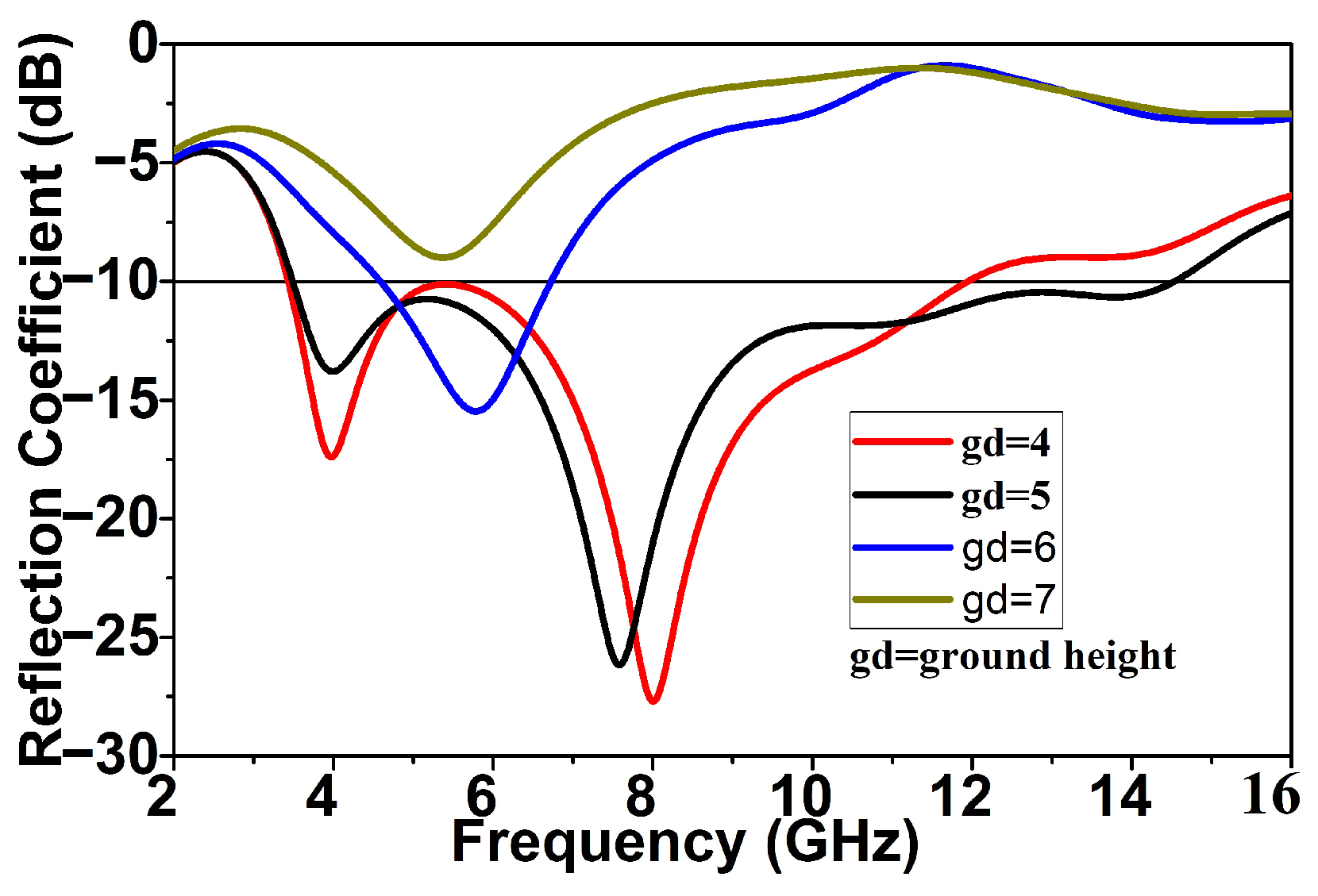

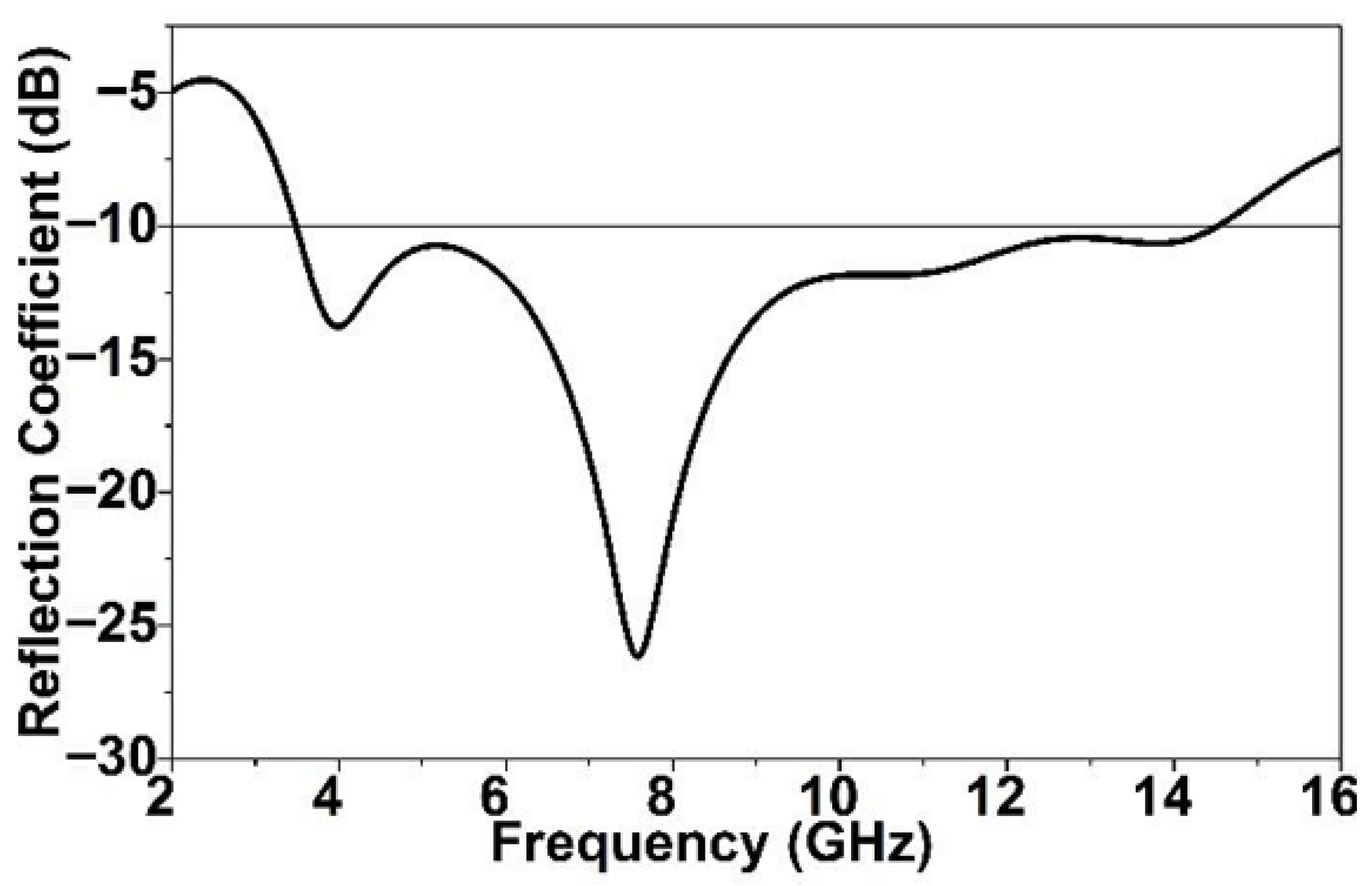

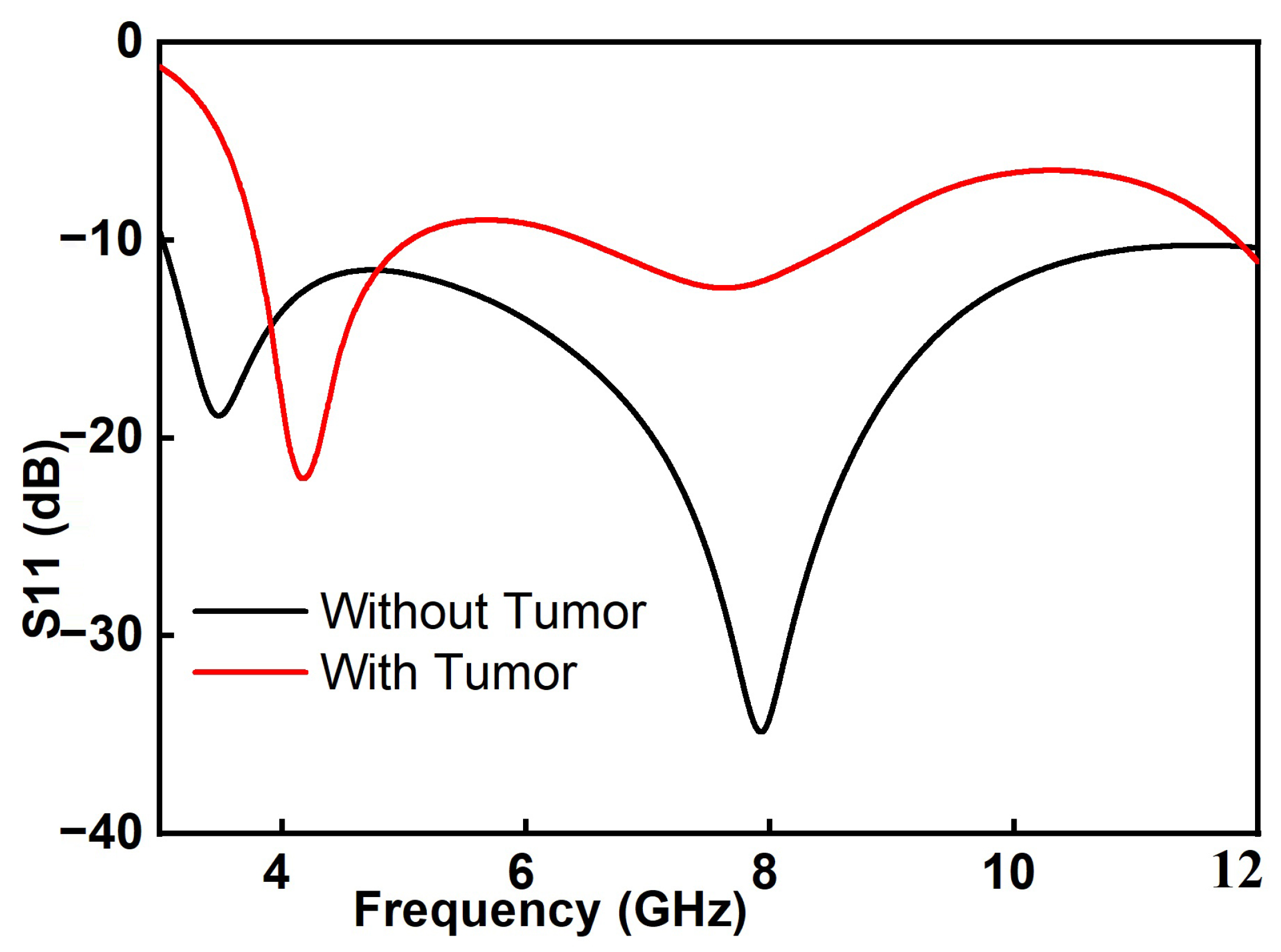

4.5.1. Antenna Reflection Coefficient

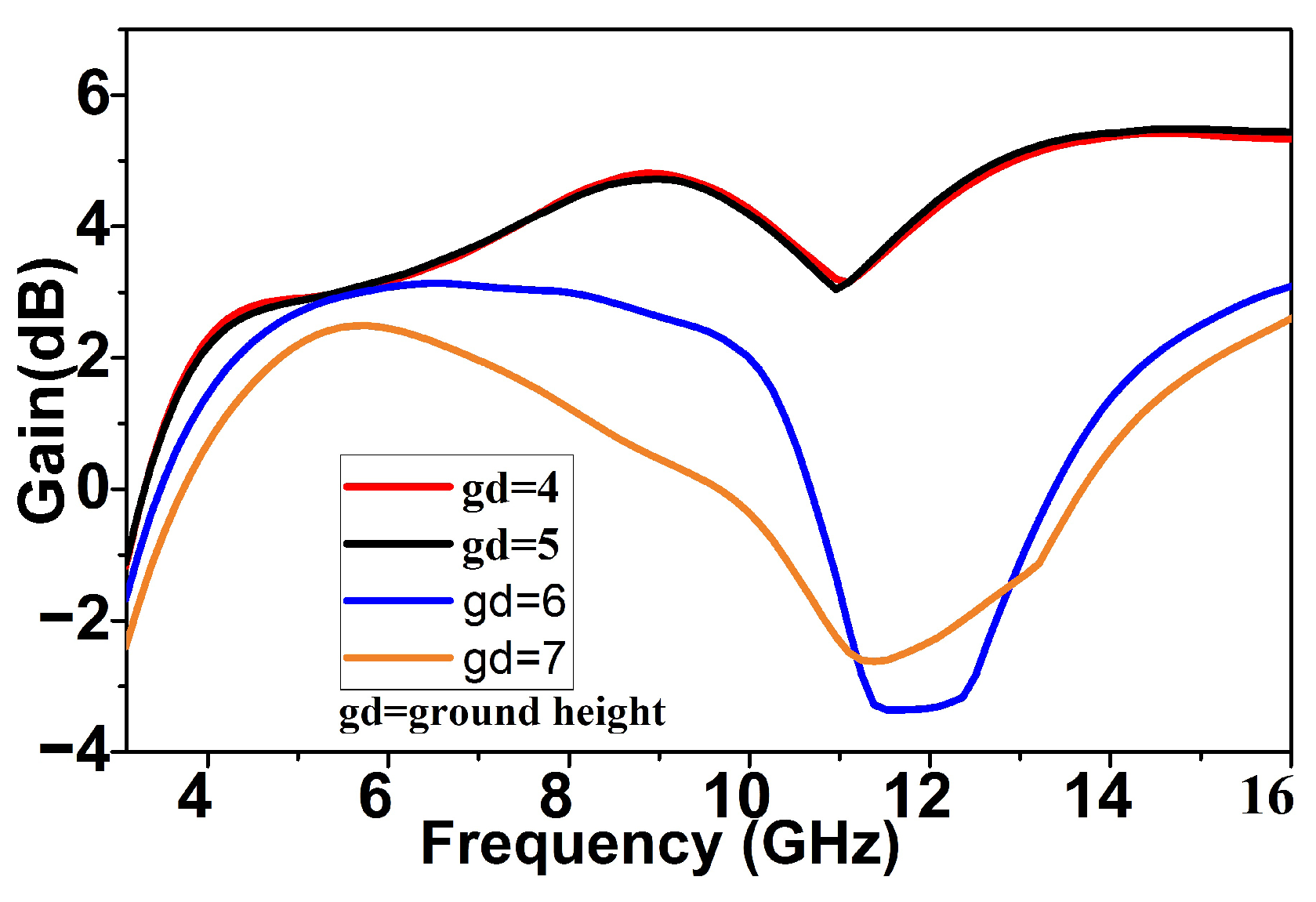

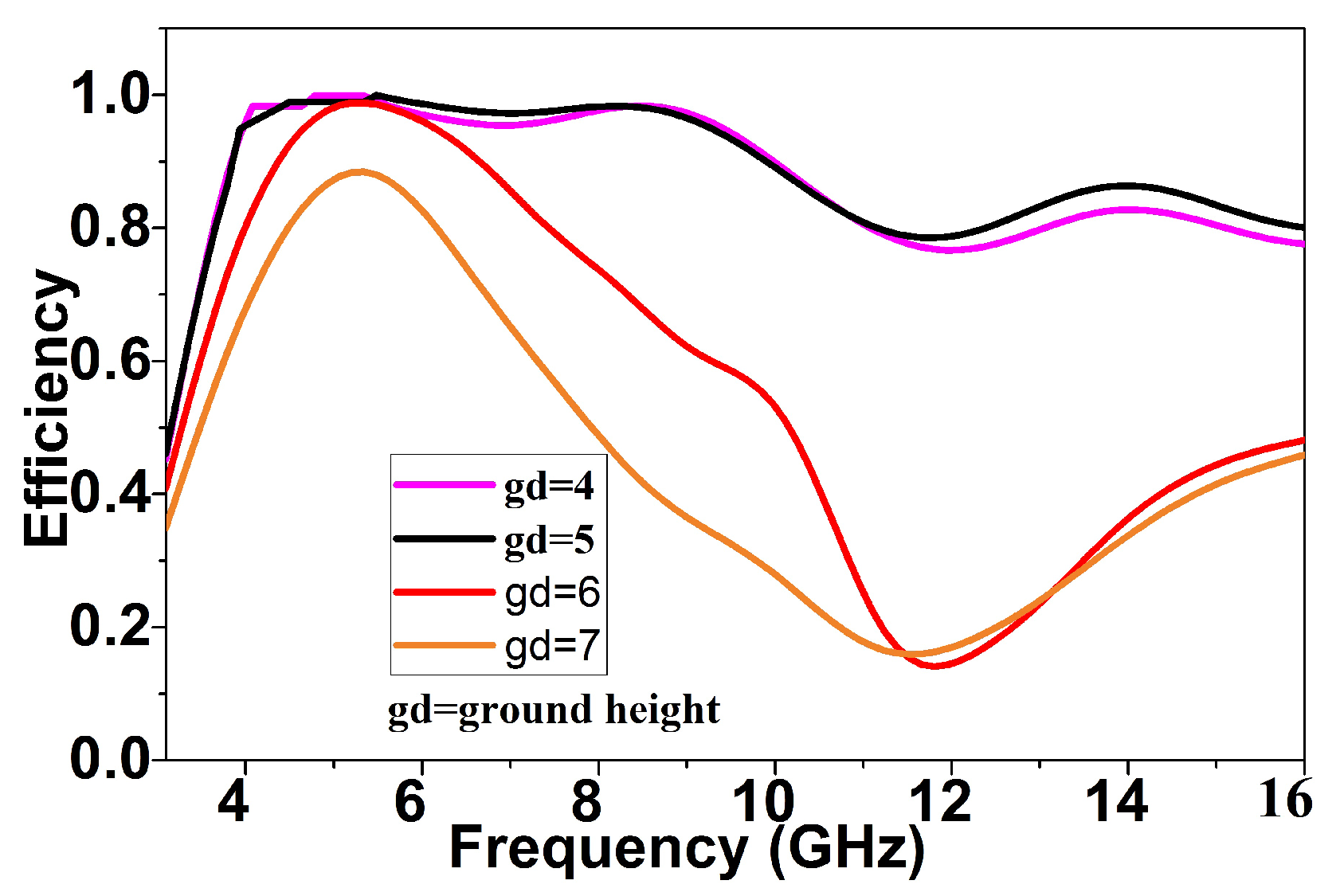

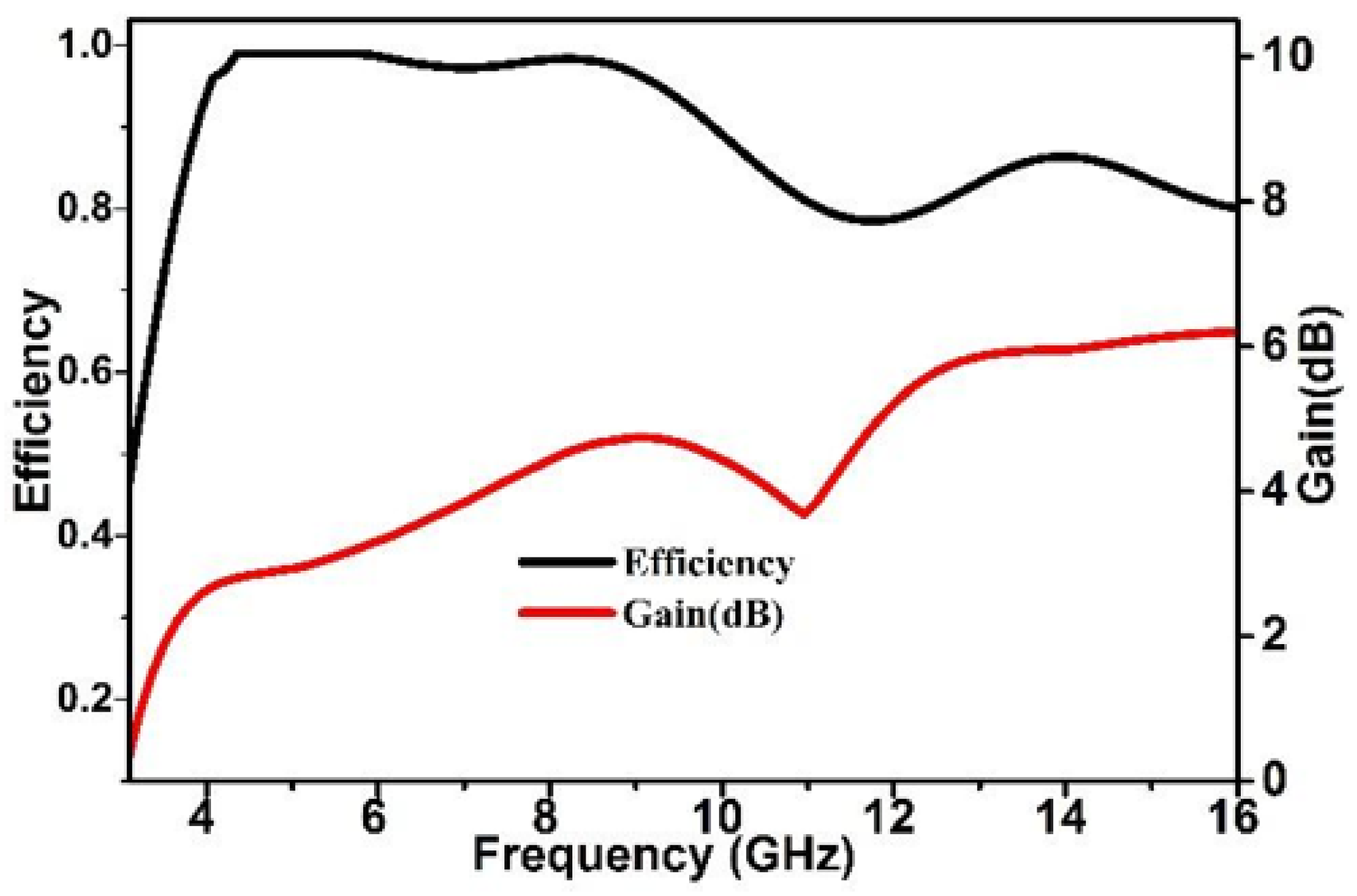

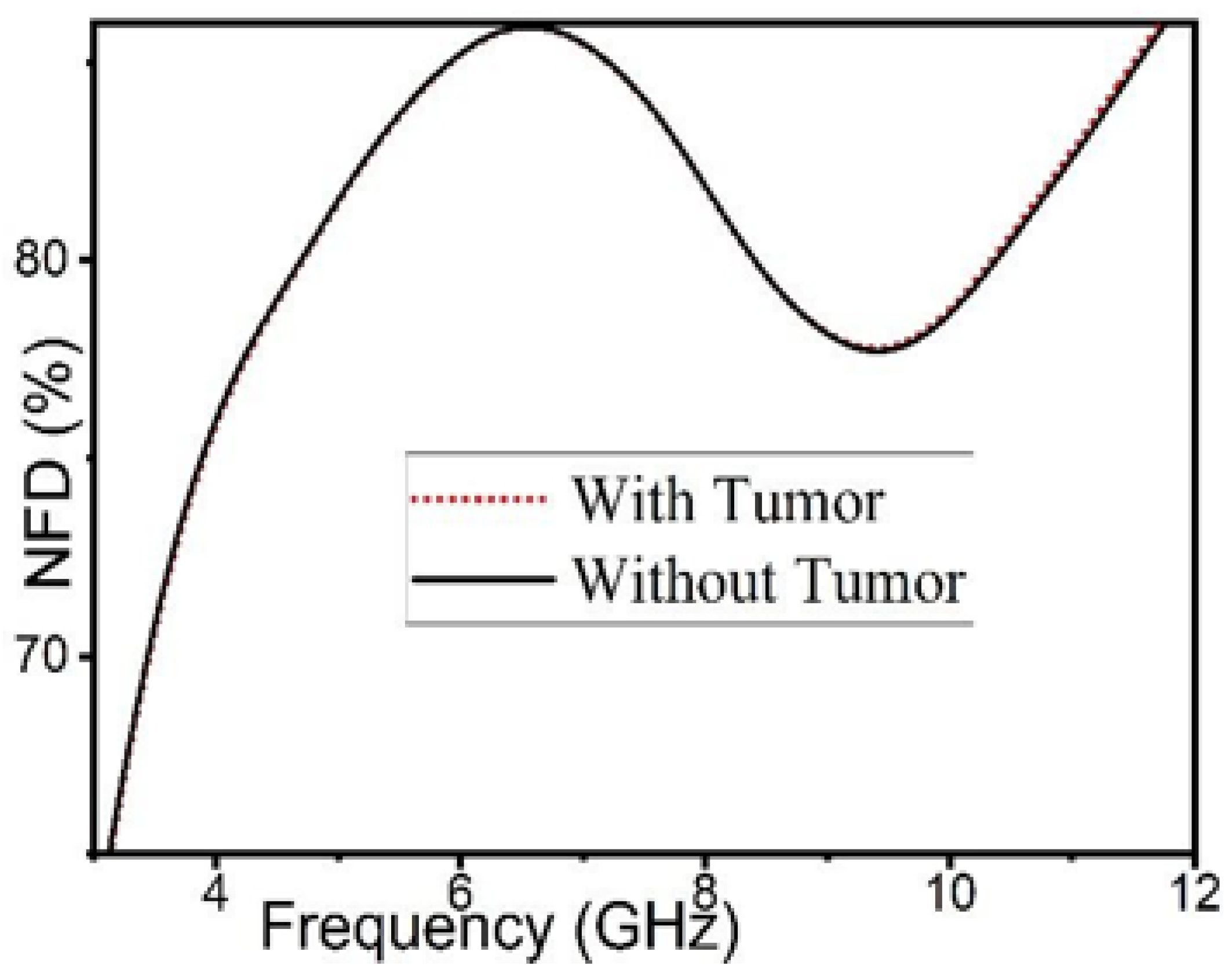

4.5.2. Efficiency and Gain

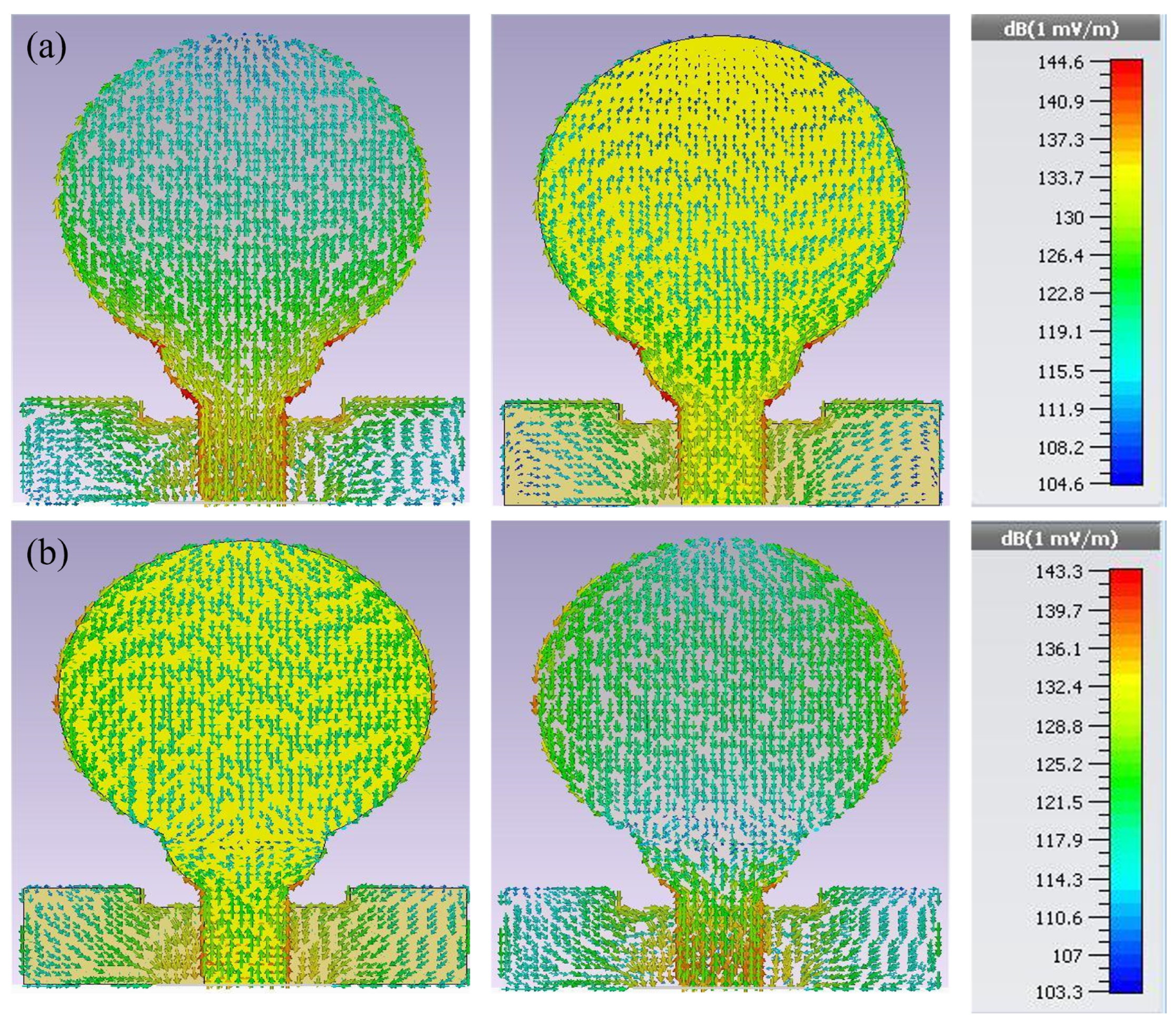

4.5.3. Surface Current Distribution

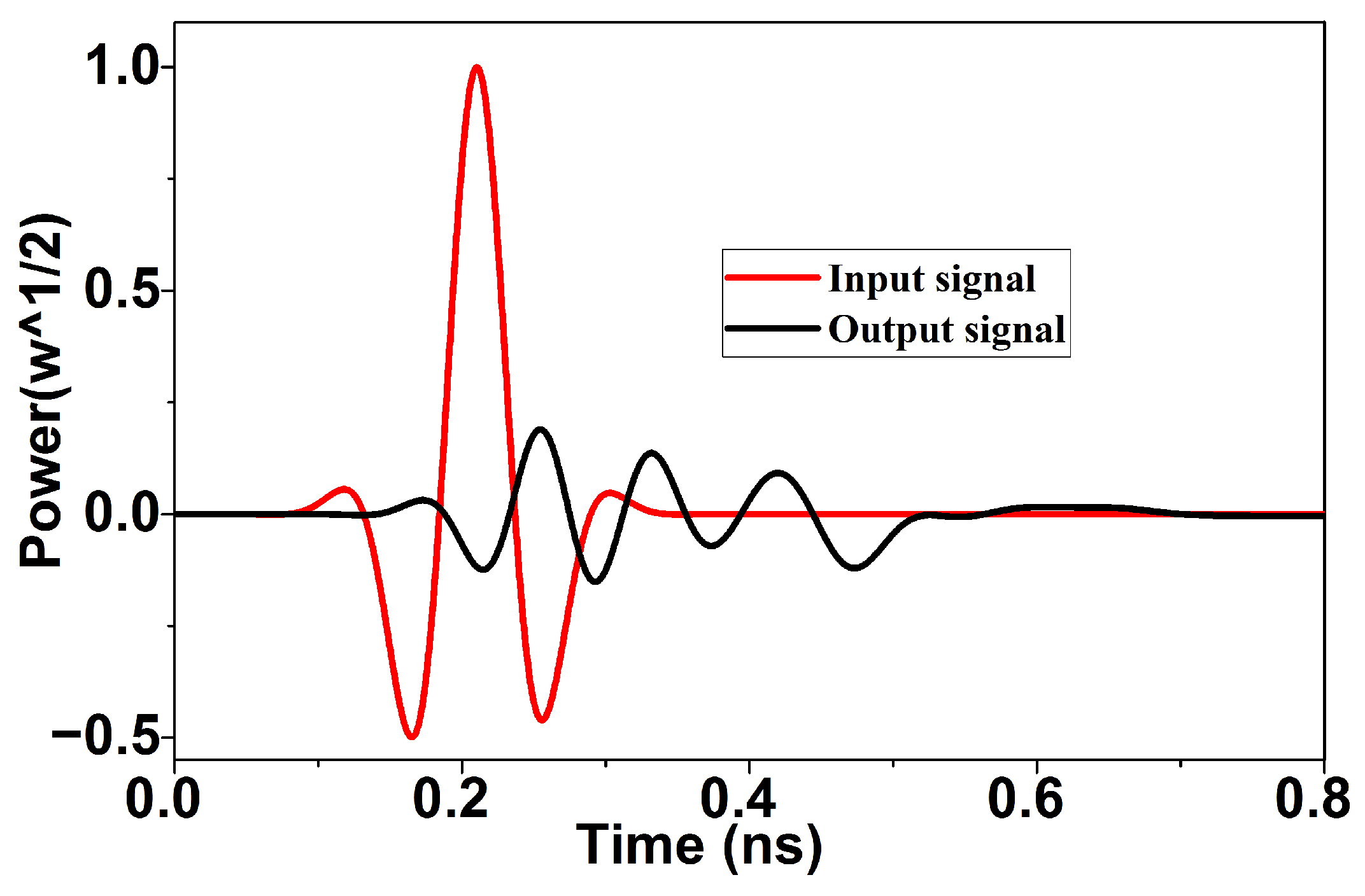

4.5.4. Time Domain Results

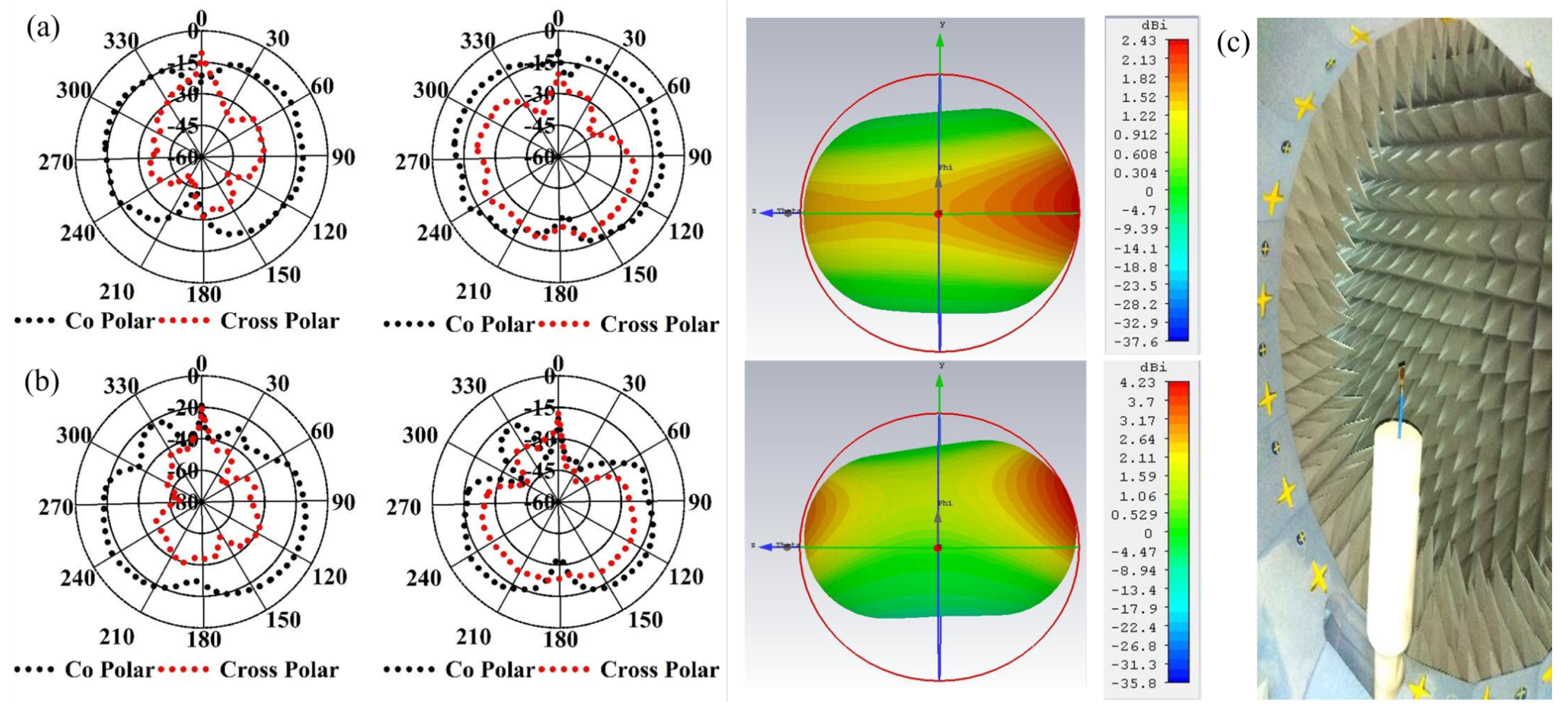

4.5.5. Directivity Analysis

4.5.6. Group Delay

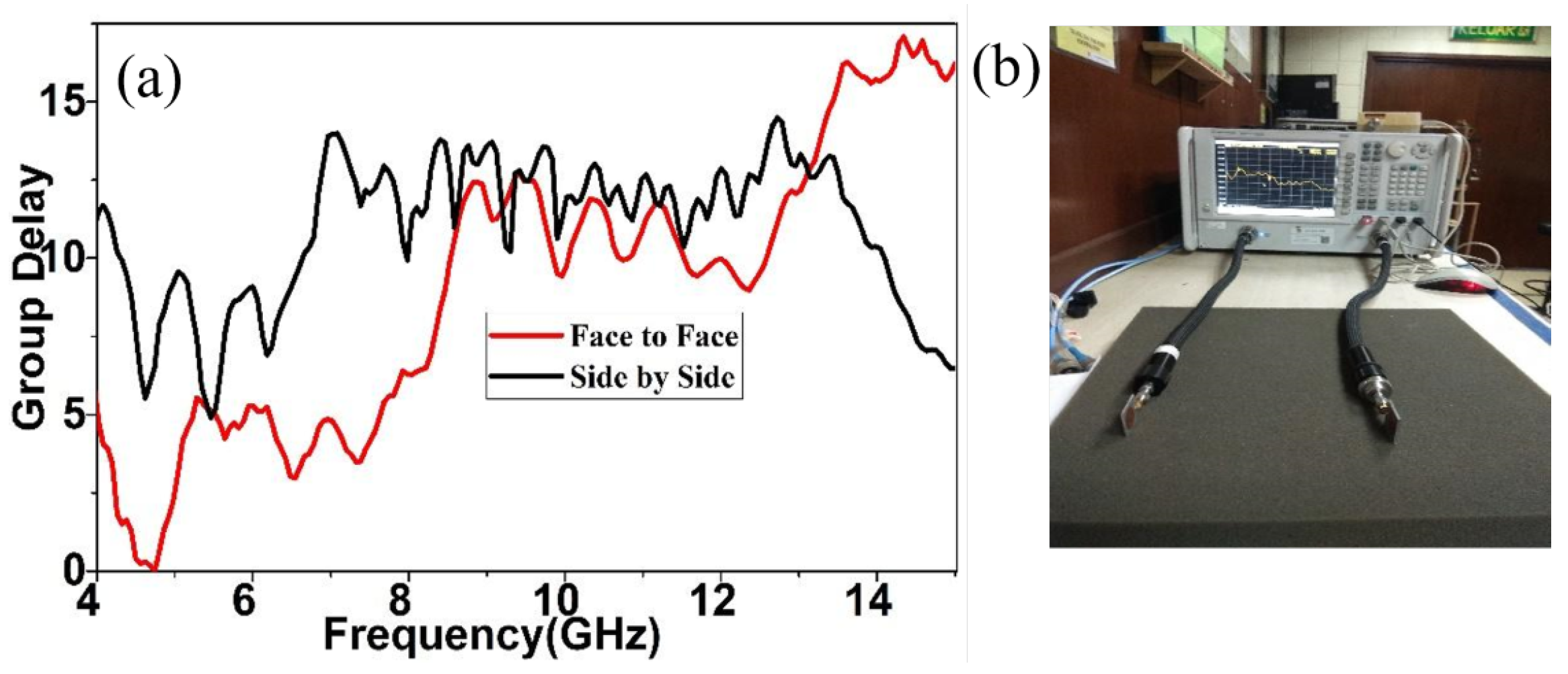

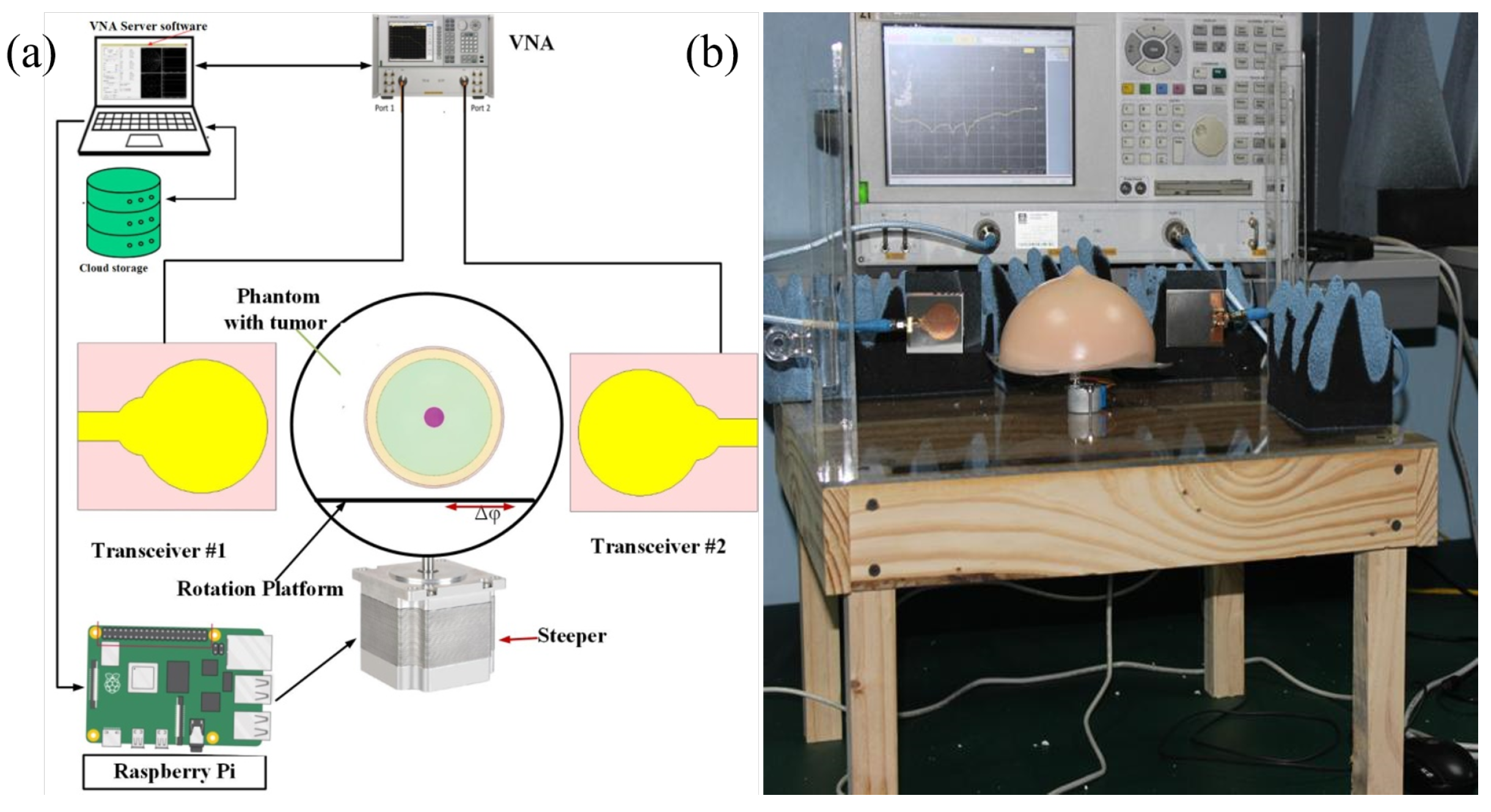

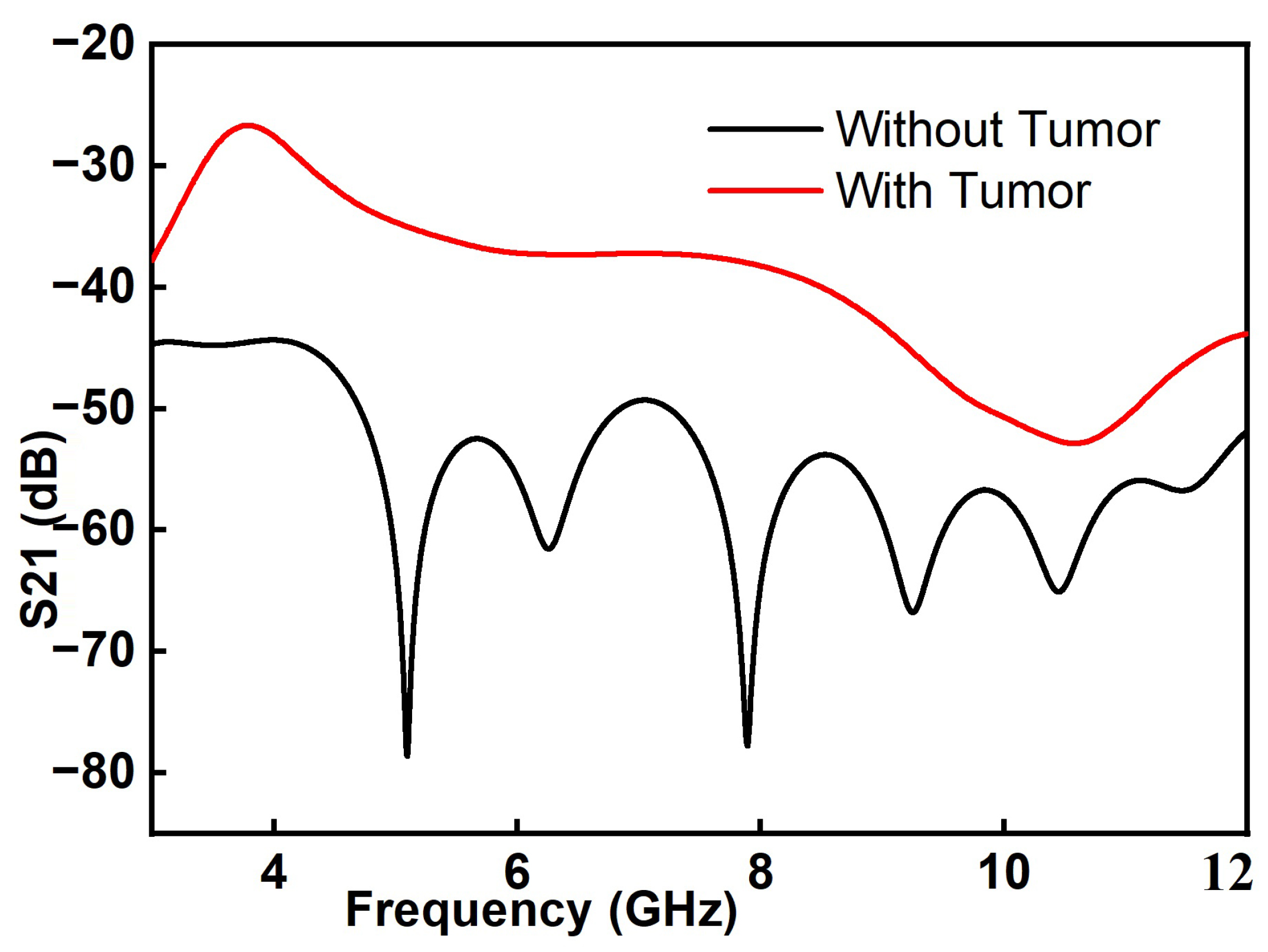

4.6. Imaging Performance Analysis

5. Conclusions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

References

- Al’Habsi, S.; Al’Ruzaiqi, T.; Gopinathan, S.T. Development of antenna for microwave imaging systems for breast cancer detection. J. Mol. Imaging Dyn. 2016, 6, 2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafique, U.; Pisa, S.; Cicchetti, R.; Testa, O.; Cavagnaro, M. Ultra-wideband antennas for biomedical imaging applications: A survey. Sensors 2022, 22, 3230. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Othman, A.; Shaari, N.I.S.; Zobilah, A.M.; Shairi, N.A.; Zakaria, Z. Design of compact ultra wideband antenna for microwave medical imaging application. Indones. J. Electr. Eng. Comput. Sci. (IJEECS) 2019, 15, 1197–1202. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Saeidi, T.; Mahmood, S.N.; Saleh, S.; Timmons, N.; Al-Gburi, A.J.A.; Razzaz, F. Ultra-wideband (UWB) antennas for breast cancer detection with microwave imaging: A review. Results Eng. 2025, 25, 104167. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uddin, S.; Mohibullah, M.; Hasan, M. Design of Ultra-Wideband (UWB) Microstrip Patch Antenna for Biomedical Telemetry Applications. ICCK Trans. Mob. Wirel. Intell. 2025, 1, 11–18. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Abdulla, F.A.A.; Demirkol, A. A novel textile-based UWB patch antenna for breast cancer imaging. Phys. Eng. Sci. Med. 2024, 47, 851–861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chaurasia, A.S.; Shankhwar, A.; Gupta, R. Design and analysis of UWB patch antenna for breast cancer detection. J. Integr. Sci. Technol. 2024, 12, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Azim, R.; Islam, M.T.; Misran, N. Compact tapered-shape slot antenna for UWB applications. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2011, 10, 1190–1193. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, H.-W.; Yang, C.-F. Miniature hook-shaped monopole antenna for UWB applications. Electron. Lett. 2010, 46, 265–266. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, Z.; Chang, L.; Cui, Y.; Zhang, A. Miniaturized and wideband metasurface antenna sensor for breast tumor detection. Sens. Actuators A Phys. 2025, 394, 116973. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Naik, K.; Ketavath, K. In-Vitro Test of Miniaturized CPW-Fed Implantable Conformal Patch Antenna at ISM Band for Biomedical Applications. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 43547. [Google Scholar]

- Samsuzzaman, M.; Islam, M.T. A semicircular shaped super wideband patch antenna with high bandwidth dimension ratio. Microw. Opt. Technol. Lett. 2015, 57, 445–452. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yıldız, Ş.; Kurt, M.B. Breast cancer detection using a high-performance ultra-wideband Vivaldi antenna in a radar-based microwave breast cancer imaging technique. Appl. Sci. 2025, 15, 6015. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, M.; Islam, M.T.; Samsuzzaman, M.; Kibria, S.; Misran, N. Design and parametric investigation of directional antenna for microwave imaging application. IET Microw. Antennas Propag. 2016, 11, 770–778. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fear, E.C.; Hagness, S.C.; Meaney, P.M.; Okoniewski, M.; Stuchly, M.A. Enhancing breast tumor detection with near-field imaging. IEEE Microw. Mag. 2002, 3, 48–56. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, S.; Lau, R.W.; Gabriel, C. The dielectric properties of biological tissues: III. Parametric models for the dielectric spectrum of tissues. Phys. Med. Biol. 1996, 41, 2271–2293. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lazebnik, A.; Converse, M.C.; Booske, S.H.; Okoniewski, M.S. Ultra-wideband electromagnetic characterization of normal, benign, and malignant breast tissues: Human and animal studies. Phys. Med. Biol. 2007, 52, 6093–6115. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Islam, M.T.; Mahmud, M.Z.; Misran, N.; Takada, J.-I.; Cho, M. Microwave breast phantom measurement system with compact side-slotted directional antenna. IEEE Access 2017, 5, 5321–5330. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahdi, R.H.; Alsudani, A.; Abdalrazak, M.Q.; Abdulnabi, H.A. Design of defective ground plane modified microstrip patch antenna for ultra-wideband applications. TELKOMNIKA Telecommun. Comput. Electron. Control 2024, 22, 34–41. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, M.; Kibria, S.; Samsuzzaman, M.; Misran, N.; Islam, M.T. A New High Performance Hibiscus Petal Pattern Monopole Antenna for UWB Applications. Appl. Comput. Electromagn. Soc. J. 2016, 31, 373–380. [Google Scholar]

- Gautam, A.K.; Yadav, S.; Kanaujia, B.K. A CPW-fed compact UWB microstrip antenna. IEEE Antennas Wirel. Propag. Lett. 2013, 12, 151–154. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fiser, O.; Hruby, V.; Vrba, J.; Drizdal, T.; Tesarik, J.; Vrba, J., Jr.; Vrba, D. UWB bowtie antenna for medical microwave imaging applications. IEEE Trans. Antennas Propag. 2022, 70, 5357–5367. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, G.; Xiao, X.; Lu, M.; Zang, X.; Zhang, X.; Kikkawa, T. Ultra-wideband microwave imaging for breast tumor screening using step recovery diode-based pulse generator. Int. J. Circuit Theory Appl. 2024, 52, 1607–1620. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Särestöniemi, M.; Reponen, J.; Sonkki, M.; Myllymäki, S.; Pomalaza-Raez, C.; Tervonen, O.; Myllylä, T. Breast cancer detection feasibility with UWB flexible antennas on wearable monitoring vest. In Proceedings of the 2022 IEEE International Conference on Pervasive Computing and Communications Workshops and other Affiliated Events (PerCom Workshops), Pisa, Italy, 21–25 March 2022; pp. 751–756. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mir, F.; Kouhalvandi, L.; Matekovits, L. Deep neural learning based optimization for automated high performance antenna designs. Sci. Rep. 2022, 12, 16801. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Kurniawati, N. Predicting Rectangular Patch Microstrip Antenna Dimension Using Machine Learning. J. Commun. 2021, 16, 394–399. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakare, V.; Singhal, P.K. Artificial Intelligence in the Estimation of Patch Dimensions of Rectangular Microstrip Antennas. Circuits Syst. 2011, 2, 330–337. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gabriel, S.; Lau, R.; Gabriel, C. The dielectric properties of biological tissues: II. Measurements in the frequency range 10 Hz to 20 GHz. Phys. Med. Biol. 1996, 41, 2251. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mahmud, M.Z.; Islam, M.T.; Rahman, M.N.; Alam, T.; Samsuzzaman, M. A miniaturized directional antenna for microwave breast imaging applications. Int. J. Microw. Wirel. Technol. 2017, 9, 2013–2018. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Amineh, R.K.; Trehan, A.; Nikolova, N.K. TEM horn antenna for ultra-wide band microwave breast imaging. Prog. Electromagn. Res. 2009, 13, 59–74. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Parameter | Symbol | Number of Values | Range (mm) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Big circle radius | R | 3 | 8 to 8.2 |

| Small circle radius | r | 10 | 3.1 to 3.9 |

| Feedline width | fw | 10 | 3.5 to 4.4 |

| Hyperparameter | Value |

|---|---|

| Learning Rate | 0.01 |

| Max Depth | 4 |

| Iterations | 4500 |

| L2 Leaf Regularization | 0.5 |

| Subsample Ratio | 0.6 |

| Column Sampling by Level | 0.8 |

| Metric | Value |

|---|---|

| Mean Squared Error (MSE) | 0.0005 |

| Mean Absolute Error (MAE) | 0.0166 |

| Root Mean Squared Error (RMSE) | 0.0228 |

| Average R2 Score | 0.9513 |

| Explainable Variance Score | 0.9528 |

| Model | Train R2 | Train MSE | Train MAE | Train EVS | Test R2 | Test MSE | Test MAE | Test EVS |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| XGBoost | 0.9999 | 1.3755 | 0.0008 | 0.9999 | 0.8894 | 0.0021 | 0.0324 | 0.9036 |

| Random Forest | 0.9828 | 0.0003 | 0.0134 | 0.9828 | 0.9058 | 0.0016 | 0.0313 | 0.9144 |

| LightGBM | 0.9617 | 0.0005 | 0.0154 | 0.9617 | 0.9215 | 0.0015 | 0.0296 | 0.9235 |

| Gradient Boosting | 0.9826 | 0.0003 | 0.0123 | 0.9827 | 0.9209 | 0.0013 | 0.0275 | 0.9274 |

| HistGradientBoosting | 0.9624 | 0.0005 | 0.0149 | 0.9624 | 0.9222 | 0.0015 | 0.0301 | 0.9238 |

| DecisionTree | 1.0000 | 3.5 × 10−31 | 2.5 × 10−16 | 1.000000 | 0.6478 | 0.0059 | 0.0455 | 0.6507 |

| KNN | 0.8239 | 0.0026 | 0.0347 | 0.8241 | 0.7113 | 0.0084 | 0.0520 | 0.7377 |

| Ridge | 0.6836 | 0.0040 | 0.0490 | 0.6836 | 0.5931 | 0.0049 | 0.0543 | 0.6313 |

| BayesianRidge | 0.6827 | 0.0040 | 0.0491 | 0.6827 | 0.5979 | 0.0049 | 0.0541 | 0.6381 |

| LinearRegression | 0.6836 | 0.0040 | 0.0490 | 0.6836 | 0.5926 | 0.0049 | 0.0543 | 0.6307 |

| SVR | 0.6342 | 0.0049 | 0.0583 | 0.6364 | 0.5984 | 0.0045 | 0.0554 | 0.6445 |

| Proposed Model | 0.9984 | 2.27 × 10−5 | 0.0036 | 0.9984 | 0.9513 | 0.0005 | 0.0166 | 0.9528 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2026 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Mahmud, M.Z. A Machine Learning-Based Ultra-Wideband Microstrip Antenna for Microwave Imaging Applications. Electronics 2026, 15, 455. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020455

Mahmud MZ. A Machine Learning-Based Ultra-Wideband Microstrip Antenna for Microwave Imaging Applications. Electronics. 2026; 15(2):455. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020455

Chicago/Turabian StyleMahmud, Md. Zulfiker. 2026. "A Machine Learning-Based Ultra-Wideband Microstrip Antenna for Microwave Imaging Applications" Electronics 15, no. 2: 455. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020455

APA StyleMahmud, M. Z. (2026). A Machine Learning-Based Ultra-Wideband Microstrip Antenna for Microwave Imaging Applications. Electronics, 15(2), 455. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15020455