Abstract

Quantum communication presents new opportunities for overcoming the limitations of classical wireless systems, particularly those associated with noise, fading, and interference. Building upon the principles of classical orthogonal frequency division multi-plexing (OFDM), this work proposes a quantum OFDM architecture tailored for video transmission. In the proposed system, video sequences are first compressed using the versatile video coding (VVC) standard with different group of pictures (GOP) sizes. Each GOP size is processed through a channel encoder and mapped to multi-qubit states with various qubit configurations. The quantum-encoded data is converted from serial-to-parallel form and passed through the quantum Fourier transform (QFT) to generate mutually orthogonal quantum subcarriers. Following reserialization, a cyclic prefix is appended to mitigate inter-symbol interference within the quantum channel. At the receiver, the cyclic prefix is removed, and the signal is restored to parallel before the inverse QFT (IQFT) recovers the original quantum subcarriers. Quantum decoding, classical channel decoding, and VVC reconstruction are then employed to recover the videos. Experimental evaluations across different GOP sizes and channel conditions demonstrate that quantum OFDM provides superior resilience to channel noise and improved perceptual quality compared to classical OFDM, achieving peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR) up to 47.60 dB, structural similarity index measure (SSIM) up to 0.9987, and video multi-method assessment fusion (VMAF) up to 96.40. Notably, the eight-qubit encoding scheme consistently achieves the highest SNR gains across all channels, underscoring the potential of quantum OFDM as a foundation for future high-quality video transmission.

1. Introduction

Video has emerged as the most critical medium for communication, sensing, and interaction in modern digital systems, supporting applications ranging from autonomous driving and remote healthcare to industrial monitoring, immersive augmented reality (AR) [1] and virtual reality (VR) [2] environments. These applications rely on continuous, high-quality video streams to make accurate, real-time decisions, making reliable video transmission an essential requirement rather than a mere convenience [3]. Transmitting compressed video, however, is far more challenging than delivering images or uncompressed data. Modern video codecs such as versatile video coding (VVC) [4] achieve high compression ratios by exploiting temporal and spatial redundancies across multiple frames, which introduces strong inter-frame dependencies. As a result, even a single corrupted reference frame can propagate errors across many subsequent frames within the same group of pictures (GOP), significantly degrading perceptual quality. The reduced redundancy in compressed video makes it highly sensitive to channel impairments such as noise, fading, and packet loss, while real-time applications impose strict timing constraints that leave little tolerance for retransmissions or delays. Furthermore, higher resolutions and frame rates, combined with low-latency requirements, substantially increase the volume of data to be transmitted, placing immense pressure on conventional communication systems. Collectively, these factors make compressed video transmission one of the most demanding challenges for modern wireless networks, highlighting the urgent need for robust, efficient, and adaptive transmission technologies capable of maintaining visual quality under dynamic channel conditions.

Contemporary wireless systems have implemented a range of advanced physical-layer techniques to accommodate the increasing volume of video traffic while ensuring the reliable delivery and high perceptual fidelity of transmitted content under dynamic and often adverse channel conditions. Among these, orthogonal frequency division multiplexing (OFDM) [5] has become a foundational approach due to its ability to convert a frequency-selective fading channel into multiple parallel flat-fading subchannels. By doing so, OFDM enables efficient spectrum utilization and robust performance in multipath environments, making it a key enabler of large-scale high-definition video delivery in standards such as 4G, 5G, and Wi-Fi. Despite its widespread adoption, classical OFDM exhibits several limitations. It suffers from high peak-to-average power ratio (PAPR), which can reduce power efficiency; it is sensitive to synchronization errors, which can cause inter-carrier interference (ICI); and it accumulates noise and interference across subcarriers, potentially degrading compressed video quality under adverse channel conditions. These intrinsic drawbacks make classical OFDM less suitable for next-generation applications that demand higher reliability, ultra-low latency, and increased data rates, motivating exploration of novel communication paradigms that extend beyond conventional communication techniques.

In response, quantum communication [6] offers a fundamentally different paradigm for information processing. By exploiting unique quantum-mechanical phenomena such as superposition [7] and entanglement [8], quantum systems can encode and manipulate information in ways that have no classical counterpart. Superposition allows quantum bits (qubits) to represent multiple states simultaneously, enabling inherent parallelism and higher information density per symbol. Entanglement provides correlations between qubits that can be leveraged for error detection, synchronization, or information redundancy in ways impossible in classical systems. These quantum properties open new avenues for robust, high-capacity communication, including novel approaches to error mitigation and signal resilience. While quantum communication technologies are still maturing, rapid progress in quantum hardware, quantum key distribution (QKD) [9], teleportation protocols [10], and compatible quantum error-correction (QEC) [11] techniques has made it feasible to explore quantum-enhanced transmission schemes that could eventually support practical multimedia services.

One promising quantum approach is quantum OFDM [12], which extends the classical concept of multicarrier modulation into the quantum domain. Quantum OFDM leverages the quantum Fourier transform (QFT) [13] to generate mutually orthogonal quantum subcarriers, analogous to the orthogonal subchannels of classical OFDM. This quantum approach seeks to combine the spectral-efficiency and multipath-resilience benefits of OFDM with the inherent robustness and parallelism of quantum information. Although early theoretical studies have examined aspects of quantum multicarrier communication, there remains a significant gap in the literature: comprehensive, end-to-end frameworks for practical video transmission using quantum OFDM have not yet been developed. Given the increasing prevalence of high-resolution and high-frame-rate video, developing such frameworks is critical for demonstrating the potential of quantum communication in real-world multimedia applications.

Although quantum OFDM provides a promising framework for quantum-enhanced multicarrier transmission [14], integrating it with practical video delivery presents unique challenges. Video transmission introduces additional complexities compared to static image transmission. Modern codecs such as VVC rely on hierarchical frame structures and temporal prediction to achieve high compression efficiency. While effective for reducing bitrates, these techniques amplify error propagation: a corrupted I-frame or key reference frame can affect all dependent P-frames and B-frames within the same GOP, resulting in cascading visual artifacts [15]. Furthermore, real-time video applications impose stringent timing requirements: excessive processing or retransmission delays degrade motion smoothness and can disrupt interactive or immersive experiences. Therefore, any quantum or classical transmission scheme for video must minimize error rates while maintaining latency and throughput within strict bounds. These requirements emphasize the importance of designing modulation, coding, and quantum encoding strategies that are robust to noise, channel fading, and interference while being efficient enough to handle large, compressed video bitstreams.

To address these challenges, we propose a novel and comprehensive quantum OFDM architecture for video communication. The system begins with video sequences compressed using the VVC standard, which are segmented into GOP blocks of sizes 8, 16, and 32 to balance compression efficiency and temporal error resilience. Each GOP block undergoes classical channel encoding using polar codes, enhancing robustness against transmission errors, before being mapped into quantum states via multi-qubit encoding with variable qubit configurations. This quantum encoding step leverages the parallelism and superposition properties of qubits to represent multiple bits per quantum state, enabling efficient utilization of the quantum channel. Following serial-to-parallel conversion, the QFT is applied to generate mutually orthogonal quantum subcarriers, effectively emulating classical multicarrier OFDM in the quantum domain. A cyclic prefix is appended prior to transmission to mitigate inter-symbol interference (ISI) and to provide resilience against quantum channel decoherence and noise.

The quantum channel model incorporates both decoherence effects and fading-like phenomena, capturing realistic wireless impairments and environmental noise. At the receiver, the cyclic prefix is removed, parallel quantum subcarriers are recovered, and the inverse QFT (IQFT) restores the encoded quantum states. The quantum decoder then reconstructs a classical bitstream, which passes through the classical channel decoder and the VVC decoder to recover the transmitted video frames. The proposed framework is evaluated under different multi-qubit encoding granularities, allowing an analysis of the trade-off between encoding complexity and video fidelity. For benchmarking, quantum OFDM performance is compared against a bandwidth equivalent classical OFDM system employing standard modulation schemes. Experimental results demonstrate that quantum OFDM provides significant improvements in perceptual video quality and error resilience, especially under challenging noisy-channel conditions. These findings underscore the potential of quantum OFDM as a practical, quantum-enhanced multicarrier solution capable of delivering robust, low-latency, and high-quality video transmission for next-generation multimedia applications.

The main contributions of this paper are threefold:

- 1.

- We introduce a full, end-to-end quantum OFDM framework for compressed video transmission, integrating VVC encoding, multi-qubit mapping, QFT-based modulation, and complete receiver-side processing.

- 2.

- We analyze the impact of different qubit-encoding sizes and channel-noise conditions on video-quality metrics and communication performance.

- 3.

- We compare the quantum OFDM architecture against bandwidth equivalent classical OFDM under near equivalent channel models to quantify gains in perceptual video quality and error resilience.

The structure of this manuscript is arranged to guide the reader through the key ideas and findings. In Section 2, we examine prior studies and position our contribution within the existing body of research. Section 3 then introduces the developed quantum OFDM framework along with the channel conditions considered in this work. Section 4 follows with the simulation results and corresponding discussion. The paper closes in Section 5, where we summarize the main insights and highlight potential avenues for future exploration.

2. Related Works

The following subsections provide a structured overview of prior research on classical OFDM, recent developments in quantum communication, applications of the QFT, quantum OFDM-based systems, and the key research gaps addressed by this study.

2.1. Classical OFDM for Video Transmission

OFDM has become a foundational technique in modern broadband wireless systems due to its ability to handle channels affected by delay spread and variations across the frequency band [16,17,18]. Instead of pushing a single high-rate signal through a fading environment, OFDM restructures the transmission into many slow-moving components, each mapped to a distinct orthogonal tone. This strategy naturally reduces the impact of multipath-induced interference, uses the available spectrum efficiently, and provides strong resilience to frequency-selective channel impairments. This capability has facilitated the widespread use of OFDM in multimedia applications, including 4G, 5G, and Wi-Fi networks, supporting high-definition image and video delivery [19,20]. Various extensions of classical OFDM, such as MIMO-OFDM, adaptive OFDM, and low-PAPR techniques, have further improved data throughput, energy efficiency, and resistance to synchronization errors [21,22,23]. These enhancements enable reliable performance in applications ranging from mobile video streaming and immersive AR/VR experiences to real-time monitoring and intelligent surveillance systems. However, despite these benefits, classical OFDM faces inherent challenges, including high PAPR requirements that stress power amplifiers, susceptibility to synchronization errors across subcarriers, and cumulative noise that can compromise signal integrity [24].

2.2. Quantum Communication Developments

Quantum communication has been viewed as a fundamental departure from classical information transfer, since the process is governed by quantum phenomena such as superposition and entanglement [25,26]. Through these properties, quantum states are able to represent information in forms that cannot be reproduced by classical systems, and higher information density, parallel state evolution, and improved robustness to disturbances have been enabled. Historically, the first major progress in this domain was achieved in the context of security. The concept of quantum key distribution (QKD) was introduced as a method by which cryptographic keys could be exchanged with security guaranteed by quantum mechanics [9,27]. In protocols such as BB84 [28] and E91 [29], security is ensured because any attempt to measure or copy the transmitted quantum states alters them, in accordance with measurement collapse and the no-cloning theorem. As a result, these protocols have been established as the foundation on which quantum-secure communication systems have been built.

Following the developments in QKD, the concept of quantum teleportation [30,31] has been introduced as a mechanism through which an unknown quantum state can be reproduced at a distant location without requiring the physical transport of the original particle. Teleportation relies on pre-shared entangled states between sender and receiver, combined with classical communication channels to transmit measurement results. While teleportation does not allow faster-than-light communication, it provides a mechanism for high-fidelity state transfer that is resistant to certain types of channel noise. These foundational techniques have catalyzed extensive research into broader quantum communication applications, including secure quantum networks, distributed quantum computing, and entanglement-assisted error correction.

Recent developments have begun to explore quantum-assisted multimedia transmission, extending quantum principles beyond purely secure communications to high-dimensional media such as images and video [32,33,34]. High-fidelity transmission is achieved using single-qubit superposition encoding, where each bit value is represented by one qubit [35]. Good reconstruction quality is obtained because the quantum states are kept simple and are affected less by channel noise [36]. However, the method is limited, since a very large number of qubits is required for high-resolution images and long video sequences with low error resilience. The use of full QEC is restricted as well, because very high resource overhead is needed [37,38]. To address these limits, multi-qubit encoding is introduced [39], where several classical bits are stored in a single quantum state. In this way, transmission efficiency is increased and higher-resolution media are supported. Even so, multi-qubit states are still affected by noise and decoherence, so their reliability is reduced in practical channels.

2.3. QFT and Quantum OFDM

In the pursuit of more reliable and resource-efficient quantum processing of multimedia signals, the QFT has been adopted as an essential operation [40]. Through the QFT, quantum information is re-expressed in the frequency domain, where the structure of the data often becomes significantly more compact. This transformation allows sparsity patterns to be exposed and facilitates highly efficient representations of complex media content [41,42]. This frequency-domain representation facilitates compression by concentrating the essential information into a smaller number of significant components, thereby reducing the total number of qubits required for storage and transmission. While the QFT has been widely explored for quantum image processing [43], demonstrating that frequency-domain transformations can significantly improve resource efficiency and maintain reconstruction fidelity, its application for quantum communication and transmission remains largely unexplored and experimental. Conceptual studies have suggested its potential in quantum modulation schemes, including applications in QKD [44] and quantum teleportation protocols [45]. Additionally, several preliminary studies have explored hybrid quantum–classical OFDM schemes, entanglement-assisted transmission strategies, and early realizations of quantum OFDM for basic data transmission tasks [14,46,47,48]. However, these works are largely limited to circuit-level demonstrations, simplified quantum state transfer models, or proof-of-concept analyses. In particular, they do not present comprehensive end-to-end system models that incorporate realistic quantum channel impairments, such as noise, decoherence, and fading effects. Consequently, the cumulative impact of quantum errors across the complete transmission chain remains insufficiently characterized. Moreover, existing studies [12] do not address the challenges associated with high-dimensional multimedia content, such as video data, which demands both high fidelity and robustness to channel impairments. This highlights an open research gap in the development of quantum OFDM-based communication frameworks capable of supporting practical, high-quality video transmission over noisy quantum channels.

2.4. Key Research Gaps and Motivation

While quantum OFDM has been discussed in prior literature, the present work is novel in several key aspects. Unlike previous studies that focus primarily on circuit-level analysis or abstract quantum state transmission, this paper develops a complete end-to-end framework for compressed video communication, integrating modern VVC encoding, multi-qubit quantum encoding, quantum OFDM modulation, realistic noisy channel modeling, decoding, and full reconstruction. The proposed framework supports scalable multi-qubit encoding from 1 to 8 qubits, enabling a systematic exploration of the trade-off between quantum resource utilization, system complexity, and video reconstruction quality. Furthermore, the work evaluates performance using perceptual video quality metrics rather than relying solely on bit error rate or quantum state fidelity, providing a more meaningful measure of user-perceived quality. Finally, the framework conducts bandwidth-equivalent comparisons with classical OFDM systems, ensuring a fair and rigorous assessment of the advantages and limitations of quantum OFDM in realistic multimedia communication scenarios. Collectively, these contributions advance quantum OFDM research from isolated circuit demonstrations to practical, system-level analysis for high-fidelity video transmission.

These gaps are outlined as follows:

- Scalability for high-resolution video: Current single-qubit encoding approaches are insufficient for long-duration or high-resolution video sequences. Multi-qubit encoding has shown promise, yet its potential for video-specific applications remains largely unexplored.

- End-to-end quantum OFDM frameworks: Existing studies do not offer a complete architecture that addresses the challenges posed by temporally correlated video. Critical components such as GOP structure management, multi-qubit encoding, and quantum subcarrier allocation have yet to be integrated in a unified framework.

- Realistic quantum channel modeling: Most research neglects key channel impairments such as decoherence, amplitude damping, phase damping, and fading effects. These impairments are particularly important because errors in early frames can propagate to dependent frames, affecting overall video quality.

- Perceptual video quality evaluation: Evaluation has been mostly limited to bit-level metrics. There is a lack of comprehensive assessment using video-specific metrics such as PSNR, SSIM, and VMAF, leaving the perceptual impact of quantum transmission largely unquantified.

- Trade-offs in multi-qubit encoding: The effect of different qubit encoding sizes on transmission efficiency, noise resilience, and reconstruction quality remains under-investigated, making it difficult to determine optimal configurations.

- Comparisons with classical OFDM: No studies are conducted that directly benchmark quantum OFDM against classical OFDM under realistic noisy conditions for video, leaving its practical advantages unverified.

Addressing these gaps is essential for developing scalable, robust, and high-fidelity quantum video transmission systems. A well-designed quantum OFDM framework, leveraging multi-qubit encoding, QFT-based subcarrier generation, and realistic channel modeling, can provide both resilience to noise and efficient utilization of quantum resources, enabling high-quality video delivery in future quantum networks.

3. System Model

This section presents the proposed quantum OFDM system, developed for end-to-end video transmission to a single receiver. To assess its performance, the quantum OFDM framework is evaluated and compared with a conventional OFDM system using the same bandwidth. The following subsections outline both systems and emphasize their main distinctions. The first subsection briefly reviews the classical OFDM system to provide a reference point, whereas the second subsection presents a thorough and approachable description of the proposed quantum OFDM approach.

3.1. Classical OFDM System

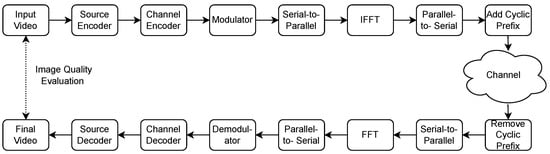

In the classical OFDM system, as illustrated in Figure 1, the transmission process begins with the input video. To comprehensively evaluate system performance, three video sequences with varying spatial and temporal complexity are selected. These include a high-motion video [49] featuring rapid movements and frequent scene changes, a medium-motion video [50] with moderate motion and intermediate structural and temporal information, and a low-motion video [51] with limited motion while retaining structural details. Each video is available at three spatial resolutions (, , and ) and at frame rates of 20, 30, and 50 frames per second (fps) to account for different temporal dynamics. It is important to note that both the classical OFDM and the proposed quantum OFDM systems can accommodate any input video content, regardless of its format, resolution, complexity, or frame rate.

Figure 1.

Classical OFDM framework for video transmission.

The compressed video bitstream is first generated by the source encoder, which in this case uses the VVC standard, and is subsequently processed by the channel encoder. In this work, polar codes [52] with a code rate of 1/2 are employed. Using a code rate of 1/2 provides a practical balance between error-correcting performance and bandwidth utilization. Unlike other classical error-correcting codes such as LDPC [53] or turbo codes [54], polar codes are highly scalable and can approach the theoretical channel capacity limits while remaining relatively simple to implement. This makes them particularly suitable for communication channels with fluctuating reliability.

Once the data has been channel-encoded, it is mapped onto complex modulation symbols using schemes such as binary phase shift keying (BPSK), quadrature phase shift keying (QPSK), and 16-quadrature amplitude modulation (16-QAM). The resulting symbols are then rearranged from a serial sequence into multiple parallel streams, forming the input for subsequent OFDM modulation.

The OFDM modulation is performed by applying an inverse fast Fourier transform (IFFT) to each parallel symbol block. The IFFT converts frequency-domain subcarrier symbols into time-domain samples , as shown in Equation (1).

Here, N represents the number of OFDM subcarriers, which divides the total available bandwidth B into equally spaced subcarriers with spacing , as expressed in Equation (2).

In this study, is selected to match the highest subcarrier configuration of the quantum OFDM system and to ensure a fair comparison. Choosing N as a power of 2 maintains subcarrier orthogonality and prevents ICI, balancing computational complexity and spectral resolution.

To combat ISI caused by multipath effects, each OFDM symbol is prefixed with a cyclic extension. This is created by taking the last 25% of the IFFT-generated samples () and attaching them to the front of the symbol, providing a guard interval that preserves the orthogonality of the subcarriers. This extends the OFDM symbol duration () as described in Equation (3).

The serialized OFDM signal is then transmitted through communication channels. In this work, both Rayleigh fading and additive white Gaussian noise (AWGN) channels are considered. The Rayleigh fading channel accurately represents multipath effects common in urban and indoor environments, whereas the AWGN channel models random noise with a constant power spectral density and Gaussian amplitude distribution. These channel models provide a realistic baseline for evaluating the system’s performance.

At the receiver, the cyclic prefix is removed, and the signal is converted back into parallel form. The fast Fourier transform (FFT) is then applied to recover the transmitted subcarrier symbols, as given in Equation (4).

Here, denotes the received time-domain samples, represents the recovered frequency-domain subcarrier symbols, N is the number of subcarriers, and n and k are the time and subcarrier-index variables, respectively. The recovered symbols are then converted from parallel to serial format, demodulated according to the original modulation scheme, and passed through the polar channel decoder to correct any transmission errors. The channel-decoded bitstream is subsequently used to reconstruct the VVC-compressed video sequence.

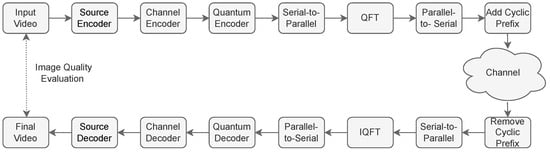

3.2. Proposed Quantum OFDM System

As shown in Figure 2, the proposed quantum OFDM system builds on the classical OFDM framework by incorporating quantum principles. The initial processing steps, up to channel encoding, follow the classical OFDM procedure. The key differences between classical OFDM (Figure 1) and quantum OFDM (Figure 2) lie in the quantum encoder and QFT/IQFT modules, which enable multi-qubit encoding, superposition, and orthogonal quantum subcarriers. These modules represent the main innovation of the proposed system and are directly responsible for improved video transmission performance. All other components remain the same, ensuring that observed benefits are solely due to the quantum processing modules. Video compression and quantum transmission serve separate purposes in the system. VVC compresses raw video into a binary bitstream at the source coding layer, while quantum OFDM transmits that bitstream over a quantum channel using quantum states and QFT-based orthogonal subcarriers. The system is independent of the source codec, so any method that produces a binary bitstream can be used without modification. VVC is selected in this work as a modern, state-of-the-art codec to generate realistic, highly compressed test data for evaluating the performance of the quantum transmission system.

Figure 2.

Quantum OFDM framework for video transmission.

Once channel encoding is complete, the resulting bitstream is transformed into quantum bits using the quantum encoder. These quantum bits are then reorganized from a serial to a parallel format and processed through the QFT to create orthogonal subcarriers for OFDM transmission. The parallel quantum subcarriers are subsequently converted back into a serial stream, and a cyclic prefix is appended to each subcarrier before transmission over the quantum channel. At the receiver side, the operations are performed in reverse order: the cyclic prefix is removed, the serial stream is converted to parallel form, and the IQFT reconstructs the time-domain signal from the orthogonal subcarriers. Finally, the quantum decoder translates the quantum states back into classical bits, which are then decoded by the channel decoder to recover the original video bitstream, allowing for video reconstruction.

For a better comprehension of the system’s functioning, the key quantum processing modules depicted in Figure 2 are described in detail in the subsequent sections.

3.2.1. Quantum Encoder/Decoder and QFT/IQFT

Once channel encoding is complete, the classical bitstream is transformed into quantum representations. Specifically, each bit with a value of 0 is represented by the quantum state defined in Equation (5), and each bit with a value of 1 is represented by the quantum state defined in Equation (6).

The qubit stream is subsequently divided into subgroups according to the quantum encoding size (n), which ranges from 1 to 8. While the system can accommodate a larger number of qubits, this study limits the analysis to eight-qubit encoding to match the standard 8-bit pixel representation commonly used in image or video encoding. Each subgroup is then mapped to its corresponding quantum state using the fundamental single-qubit representations in Equations (5) and (6).

For the single-qubit encoding (), these basic quantum states are sufficient for direct quantum encoding. For multi-qubit systems, composite quantum states are constructed through tensor products of individual qubits, resulting in a quantum state of size , where n is the number of qubits. For a two-qubit system (), the four possible quantum basis states can be constructed using the tensor-product operation, as shown in Equations (7)–(10).

Once the quantum states are prepared, the QFT is applied to generate orthogonal subcarriers. In classical OFDM, subcarrier orthogonality is established by converting modulated frequency-domain symbols into time-domain signals using the IFFT, producing sinusoids that do not interfere with each other. quantum OFDM, in contrast, encodes information in quantum computational-basis states rather than conventional numerical symbols, making the direct use of the IFFT or its quantum counterpart, the IQFT, non-feasible. At the transmitter, the QFT maps each basis state into a superposition over all possible states, with carefully controlled phases that ensure the resulting quantum subcarriers are mutually orthogonal. This approach leverages quantum superposition and parallelism to encode information across multiple qubits at once, distributing energy evenly and maintaining orthogonality across the entire quantum signal. Unlike classical systems, this method inherently preserves the total probability amplitude, enabling robust and efficient transmission in the quantum domain.

For quantum OFDM encoding, the QFT matrix [55] must match the dimension of the input quantum state vector. For an input of size , the QFT matrix is , defined as in Equation (11).

where and .

The QFT maps each computational basis state into a superposition of all basis states as described in Equation (12).

Here, denotes a computational basis state of the input quantum vector, is the N-dimensional QFT matrix, represents the computational basis states in the superposition, N is the total number of basis states, and x and k are the indices of the input and output states, respectively.

For instance, consider a two-qubit system (). The corresponding QFT operation can be explicitly represented by the matrix shown in Equation (13), which transforms each computational-basis state into a superposition of all four possible states with carefully assigned phase factors.

Applying to the two-qubit basis states through (Equations (7)–(10)) yields the transformed states through in Equations (14)–(17).

The orthogonality of the transformed vectors is confirmed by evaluating the Hermitian inner products, as illustrated in Equation (18).

This calculation confirms that and are mutually orthogonal. Similar computations for all remaining pairs verify the mutual orthogonality of all transformed states, which is fundamental for minimizing ICI in quantum OFDM systems. The relationship between the original states through and the transformed states through is expressed in Equations (19) through (22).

This shows that every output quantum state incorporates information from all four input basis states, with each contribution weighted by specific phase factors. The resulting superpositions remain mutually orthogonal, effectively replicating the function of OFDM subcarriers within the quantum framework while avoiding inter-subcarrier interference.

At the receiver, the IQFT, defined as the Hermitian adjoint of the QFT operator in Equation (23), reverses the transformation.

For an N-dimensional system, applying the IQFT to a computational basis state reconstructs the original time-domain quantum state , as shown in Equation (24).

This process enables the accurate recovery of the encoded quantum states and, subsequently, the original classical bitstream after quantum decoding. The IQFT is therefore a crucial step in quantum OFDM systems, ensuring proper retrieval of information distributed across orthogonal quantum subcarriers.

In the proposed quantum OFDM framework, the total system bandwidth B is divided among N subcarriers, with each subcarrier separated by a frequency interval given by Equation (25).

Here, n denotes the number of qubits encoded in each quantum system.

3.2.2. Cyclic Prefix for ISI Mitigation in Quantum OFDM

In quantum OFDM systems, ISI can occur, as in classical OFDM, due to channel dispersion and delay spread. This interference occurs when the end of a preceding quantum OFDM symbol overlaps with the current symbol, potentially disrupting the orthogonality of the quantum subcarriers and causing errors during quantum decoding. To mitigate ISI, a cyclic prefix (QCP) is introduced for each quantum OFDM symbol. The QCP is created by copying the final portion of the quantum OFDM symbol and placing it at the symbol’s beginning. This ensures that any channel-induced delays are absorbed by the QCP, preserving the orthogonality of the main symbol and protecting the integrity of quantum subcarrier transmission.

In the proposed framework, the QCP length () is set to 25% of the total number of quantum subcarriers N for each qubit size, as given by Equation (26).

Here, denotes the total number of quantum subcarriers determined by the qubit size n. Including the QCP, the overall quantum symbol duration () is given by Equation (27).

This design ensures that consecutive quantum symbols remain orthogonal despite multipath effects, effectively reducing ISI while maintaining reliable quantum subcarrier transmission.

3.2.3. Intrinsic Quantum Noise and Channel Modeling

In practical quantum communication systems, transmitted quantum symbols are influenced not only by classical channel impairments but also by intrinsic quantum noise resulting from decoherence. To accurately emulate these effects, the simulation framework incorporates extended AWGN and Rayleigh fading channels into the quantum environment, alongside quantum noise mechanisms [16,36,56]. The AWGN channel represents thermal noise and background interference, serving as a baseline for system performance evaluation. In contrast, the Rayleigh fading channel captures multipath propagation effects commonly encountered in urban and indoor environments, providing a realistic model of the time-varying amplitude and phase distortions that affect quantum symbol transmission.

Quantum noise originates from environmental interactions causing decoherence, which alters qubit states. This study considers five primary noise mechanisms: bit-flip, phase-flip, depolarizing, amplitude damping, and phase damping [55]. These are represented using the operator , acting on the density matrix of the transmitted quantum state.

The bit-flip channel, with probability , flips the qubit state to and vice versa, as defined in Equation (28).

where X is the Pauli-X operator.

Phase-flip noise, occurring with probability , introduces a relative phase change, as shown in Equation (29).

with Z the Pauli-Z operator.

Depolarizing noise, occurring with probability , partially randomizes the qubit state, as defined in Equation (30).

where Y is the Pauli-Y operator.

Amplitude damping, characterized by the damping probability , models energy loss, as defined in Equation (31), with the corresponding Kraus operators given in Equation (32).

Phase damping, characterized by the probability , induces decoherence in the relative phase, as defined in Equation (33).

where the corresponding Kraus operators are defined in Equation (34).

To construct the overall decoherence channel, we define a convex combination of these canonical noise channels together with an explicit identity (no-error) component. The total noise channel acting on a density matrix is given by Equation (35).

where is defined in the Equation (36).

To relate the noise to classical signal quality, the signal-to-noise ratio (SNR) in decibels is defined as in Equation (37).

where corresponds to the transmitted quantum signal power and is the noise power. The total noise probability then decreases as SNR increases, as in Equation (38).

Random variables drawn from a uniform distribution are used to dynamically distribute the noise among the five channels, as in Equation (39).

The individual error probabilities are scaled according to Equation (40).

This randomized allocation is sufficient to analyze the impact of physical noise channels in the considered quantum system. By varying the contribution from each individual noise type across simulation runs while controlling the overall noise level via SNR, the approach captures signal-dependent and heterogeneous decoherence effects typical of practical quantum communication environments [12,37,39,56,57].

3.2.4. Layered Quantum Channel Representation

The quantum channel is modeled through three distinct evaluations [57], each integrating environmental propagation effects with intrinsic quantum decoherence.

- Indoor Rayleigh Fading with Quantum Decoherence: Models indoor multipath channels with delays , gains dB, and a Doppler shift of Hz, along with intrinsic quantum errors modeled by the bit-flip, phase-flip, depolarizing, amplitude damping, and phase damping channels in Equations (28)–(34). The total noise channel is represented by Equation (35), with individual probabilities dynamically scaled according to Equations (39) and (40).

- Urban Rayleigh Fading with Quantum Decoherence: Captures multipath fading in urban environments. The channel has four path delays , gains dB, and a Doppler shift of Hz. Quantum decoherence is applied simultaneously as described above.

- AWGN with Quantum Decoherence: The simplest scenario, where transmitted quantum states are subjected to AWGN as defined in Equation (37), along with the full quantum decoherence effects.

Moreover, in the proposed quantum OFDM framework, channel distortions are compensated following the application of the IQFT, assuming ideal conditions with perfect channel state information (CSI) for equalization. In real-world scenarios, CSI can be obtained using quantum pilot signals, where pre-defined qubit states are sent through the channel and measured at the receiver to assess and characterize the channel properties.

3.3. Simulation Setup

The simulation setup used for the evaluation of classical and quantum OFDM systems is summarized in Table 1. All key parameters are consolidated to ensure clarity and reproducibility of the experiments. Simulations are conducted in MATLAB R2025a with the Quantum Computing Toolbox (v2.1) and Communications Toolbox, and are executed on a system equipped with an Intel Core i5-1345U CPU (1.60 GHz, Intel Corporation, Santa Clara, CA, USA) and 16 GB of RAM. Random number generators are initialized with fixed seeds, which are rotated across Monte Carlo runs to capture stochastic variability while maintaining reproducibility. Three video sequences with low, medium, and high motion characteristics are selected. Each sequence is tested at multiple spatial resolutions and frame rates, and GOP sizes of 8, 16, and 32 are applied to investigate the effect of temporal prediction and error propagation. Classical OFDM parameters, including subcarrier count, cyclic prefix, modulation schemes, and polar code rate, are configured to reflect typical communication system settings. AWGN, indoor Rayleigh, and urban Rayleigh fading channels are modeled with realistic multipath delays, path gains, and Doppler shifts. Quantum OFDM simulations are performed with multi-qubit encoding (1–8 qubits), and QFT/IQFT operations are applied. Quantum noise is introduced via five standard channels: bit-flip, phase-flip, depolarizing, amplitude damping, and phase damping. The total noise level is controlled by SNR and is distributed proportionally among the individual noise types. Monte Carlo simulations are executed with 100 runs per SNR point. The performance of the proposed quantum OFDM-based communication system is evaluated using quantitative metrics that capture end-to-end video quality, including peak signal-to-noise ratio (PSNR), structural similarity index measure (SSIM) [58], and video multi-method assessment fusion (VMAF) [59]. These metrics are chosen because they account for temporal and spatial dependencies in compressed video streams, providing a more meaningful assessment of perceptual quality than raw physical-layer metrics such as bit error rate (BER). The reported results represent average values computed across all tested image resolutions and frame rates, providing a comprehensive assessment of system performance under varying operational conditions. These metrics capture both the fidelity of reconstructed quantum-encoded video and the preservation of perceptual quality after transmission. Standard deviations computed at representative SNR points indicate that the reported averages are statistically robust. Both classical and quantum OFDM systems are evaluated under identical total bandwidth and normalized bit energy conditions, with all transmitted symbols normalized to unit average power. The SNR is calculated as the ratio of signal to noise power, ensuring fair, bandwidth-equivalent comparisons. This setup guarantees that any observed performance differences are due to quantum encoding and QFT-based subcarrier design, not differences in spectral or energy resources.

Table 1.

Simulation setup for classical and quantum OFDM systems.

In addition, the classical OFDM baseline is configured to be fully equivalent to the proposed QOFDM framework. Both systems use a maximum of subcarriers, normalized bandwidth B, subcarrier spacing , symbol duration, and a cyclic prefix length of . All subcarriers are used for data transmission except for one DC subcarrier, and no pilot subcarriers are employed, as perfect channel knowledge is assumed in both systems. Identical indoor and urban Rayleigh multipath profiles, including delays, gains, and Doppler shifts, are applied uniformly to both classical and quantum systems. Therefore, performance comparisons are conducted using normalized bandwidth and effective spectral efficiency, ensuring a fair and rigorous evaluation.

4. Results and Discussion

The performance of classical and quantum OFDM systems is evaluated under equivalent bandwidth conditions. Quantum OFDM, employing multi-qubit encoding and QFT-based subcarrier processing, preserves high video quality across all tested scenarios despite channel impairments and quantum noise. The results are analyzed for different channel models, video resolutions, and GOP configurations. PSNR, SSIM, and VMAF metrics are reported to quantify reconstruction quality, and observed trends are used to assess the robustness and advantages of the proposed quantum framework relative to classical systems.

In this section, the performance improvement is expressed in terms of channel SNR gain, which indicates how much lower the SNR can be for the proposed quantum communication system compared to the baseline system while still achieving the same target image quality. This concept is mathematically expressed as in Equation (41).

Here, and denote the channel SNR values required by the baseline and quantum systems, respectively, to achieve the same quality level Q. A positive SNR gain indicates that the same video quality can be achieved at a lower SNR using the quantum system. Thresholds widely used in video quality literature are adopted: , , and . The SNR gain is calculated from the average performance across three representative video sequences covering low, medium, and high motion, including all tested resolutions and frame rates, using the corresponding representative figures. This definition provides a clear metric for quantifying the performance advantage offered by the quantum transmission approach.

The following subsection presents a detailed description of each scenario, evaluated under different channel conditions and GOP configurations.

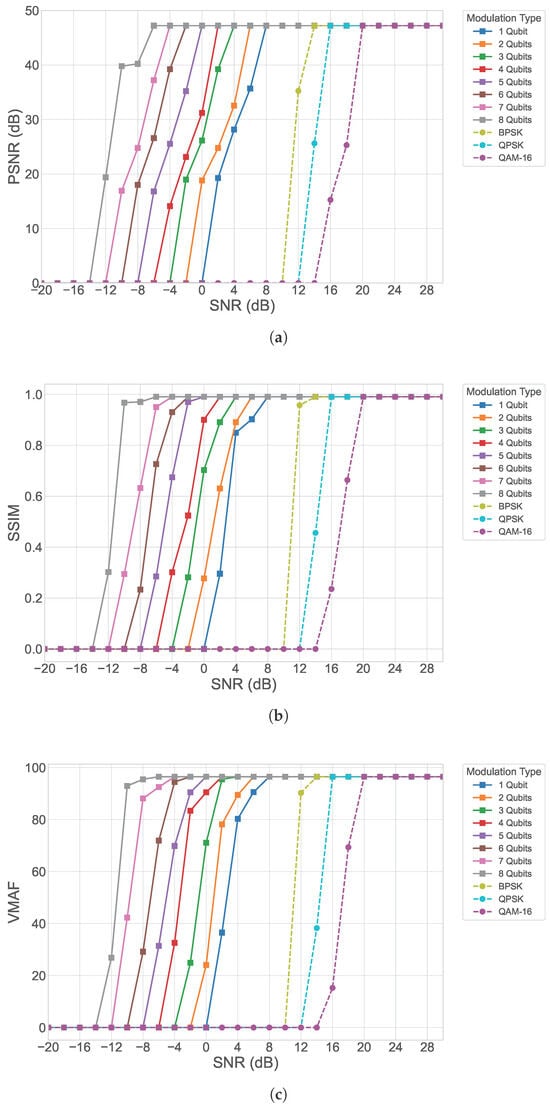

4.1. Performance Evaluation of the Proposed Quantum OFDM System in Indoor Rayleigh Fading Environments

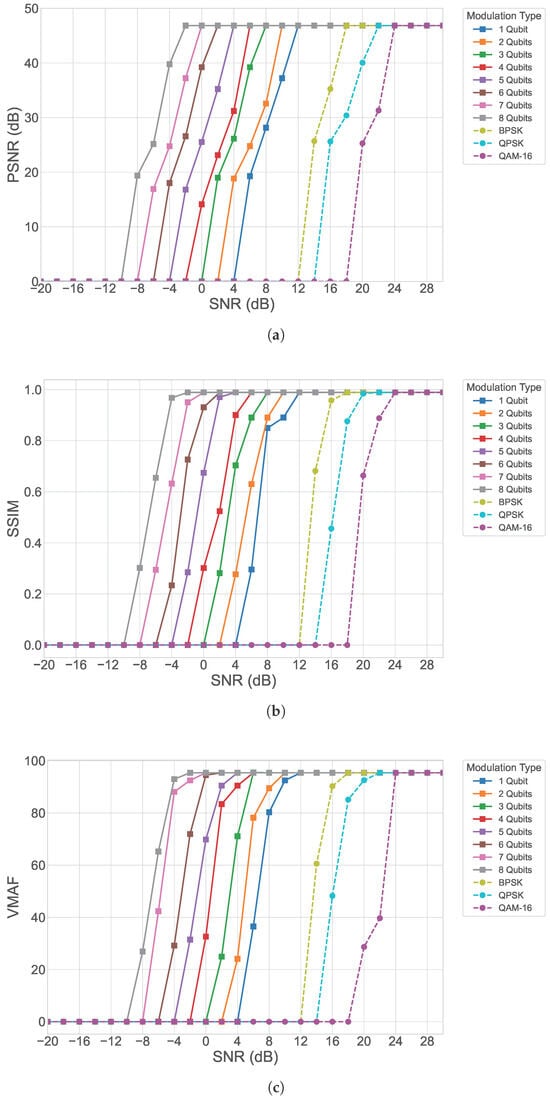

As illustrated in Figure 3, the proposed quantum OFDM video transmission system demonstrates consistently strong performance when transmitting GOP8 video sequences over indoor Rayleigh fading channels. The PSNR values, as shown in Figure 3a, increase steadily with the qubit encoding size, highlighting the scalability and efficiency of the quantum encoding. Higher qubit configurations produce quantum states of larger dimensionality, increasing the number of effective subcarriers and allowing each transmitted symbol to carry and safeguard more information. This reduces the susceptibility of the transmitted video frames to amplitude and phase distortions caused by Rayleigh fading. As a result, even under lower SNR conditions, quantum OFDM maintains significantly higher PSNR levels compared to classical OFDM schemes such as BPSK, QPSK, and 16-QAM. The superior performance is especially evident in low-to-moderate SNR regions, where quantum encoding more effectively preserves the quality of the frames within the GOP structure, leading to smoother temporal consistency across video playback.

Figure 3.

Performance analysis of the proposed quantum OFDM system for GOP8 in indoor Rayleigh fading channels (a) PSNR, (b) SSIM, and (c) VMAF.

The structural similarity results in Figure 3b provide further evidence of the enhanced visual fidelity offered by the quantum OFDM framework. Unlike PSNR, which measures pixel-level reconstruction accuracy, SSIM captures structural and luminance correlations across blocks of each frame. Higher SSIM values for quantum OFDM indicate that the proposed system not only minimizes pixel errors but also preserves edges, textures, and spatial relationships between objects across consecutive frames. This is especially important for GOP8 sequences, where the degradation of an early frame can propagate across dependent P-frames. The results show that quantum OFDM maintains higher SSIM scores across all SNRs and qubit sizes, demonstrating effective mitigation of error propagation and improved robustness in reconstructing motion-dependent content.

Further validation of perceptual quality is provided through the VMAF results in Figure 3c. VMAF incorporates detail preservation, blockiness, blurriness, and temporal smoothness, factors that correlate directly with human subjective viewing experience. The quantum OFDM system achieves noticeably higher VMAF scores compared to classical OFDM across the entire SNR range. This improvement becomes particularly prominent at medium SNR levels, where classical OFDM begins to suffer from visible temporal artifacts such as flickering, motion blur, and frame inconsistencies. In contrast, quantum OFDM maintains a more stable perceptual score, benefiting from the quantum-encoded frequency components and the enhanced energy distribution provided by the QFT. This allows the decoder to recover higher-quality reference frames, which subsequently improves the quality.

Overall, the combined PSNR, SSIM, and VMAF results indicate that the proposed quantum OFDM system significantly improves video transmission quality for GOP8 sequences. As the qubit encoding size increases, the performance gap between quantum OFDM and classical OFDM widens, demonstrating that quantum encoding provides enhanced robustness not only at the individual frame level but also across the temporal structure of the video. Among classical modulation schemes, BPSK achieves the best performance; however, even single-qubit quantum OFDM encoding substantially outperforms it, highlighting the intrinsic advantage of quantum-based information representation. These results confirm that quantum OFDM effectively preserves both signal fidelity and perceptual video quality, highlighting its potential for next-generation communication systems in indoor environments with low fading.

For GOP 16, as shown in Figure 4, and GOP 32, as shown in Figure 5, the overall performance trends remain consistent with those observed for GOP8, but the effects of temporal dependency become more pronounced. Across all SNR levels, the proposed quantum OFDM system continues to outperform classical OFDM schemes in terms of PSNR, SSIM, and VMAF. This consistent superiority demonstrates that the benefits of quantum encoding are preserved even as the temporal span between reference I-frames increases. The higher-dimensional quantum states used in quantum OFDM provide improved robustness against channel impairments, enabling the decoder to reconstruct more reliable reference frames, which in turn enhances the quality of the dependent P-frames within the GOP.

Figure 4.

Performance analysis of the proposed quantum OFDM system for GOP16 in indoor Rayleigh fading channels (a) PSNR, (b) SSIM, and (c) VMAF.

Figure 5.

Performance analysis of the proposed quantum OFDM system for GOP32 in indoor Rayleigh fading channels (a) PSNR, (b) SSIM, and (c) VMAF.

As the GOP size increases, the number of inter-coded frames grows, and these frames rely heavily on motion prediction and compensation from both intra and previously decoded inter frames. This results in a longer prediction chain, making the video stream more sensitive to distortions introduced during transmission. Any error occurring in the early or middle stages of the GOP can propagate across multiple subsequent frames, amplifying visual degradation such as blurring, temporal flicker, and block propagation. This increased vulnerability leads to the gradual performance decline observed across all systems as the GOP size increases from 8 to 16 and 32. Consequently, the video quality curves shift toward higher SNR values, indicating that higher channel quality is required to maintain the same reconstruction fidelity. This behavior reflects the cumulative effect of error propagation, where perceptual quality deteriorates at lower SNR levels and can only be preserved when channel conditions improve.

Despite this natural degradation associated with longer GOP structures, the quantum OFDM system consistently maintains a clear performance advantage over classical OFDM. Even at GOP sizes of 16 and 32, quantum OFDM provides higher reconstruction fidelity and more stable perceptual quality, as reflected by its consistently higher PSNR, SSIM, and VMAF scores across the entire SNR range. This resilience highlights the scalability and robustness of the proposed quantum-based encoding scheme, showing that quantum OFDM can effectively suppress error propagation and preserve both spatial details and temporal consistency, even under extended prediction horizons and fading-prone wireless conditions.

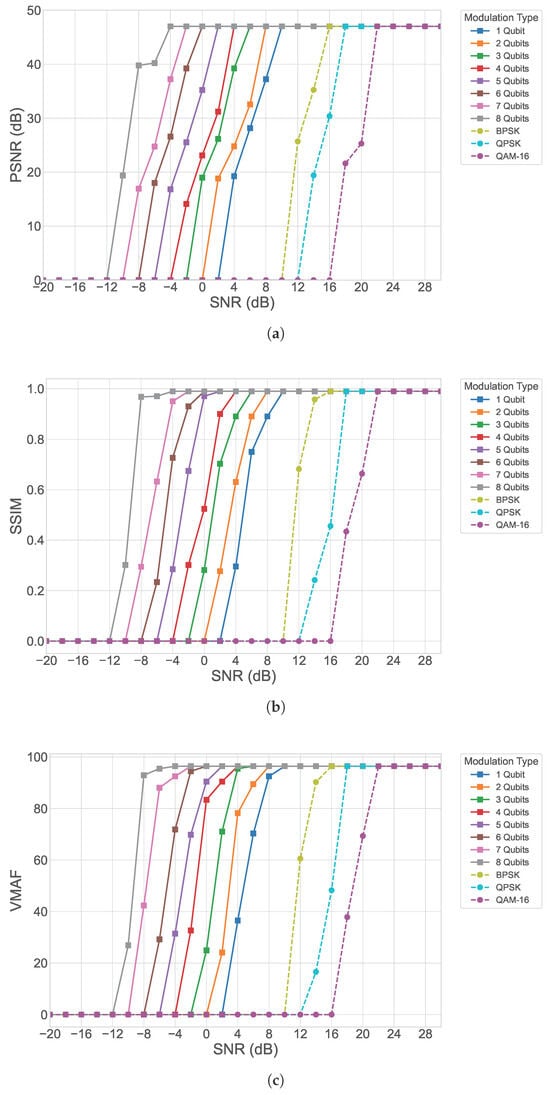

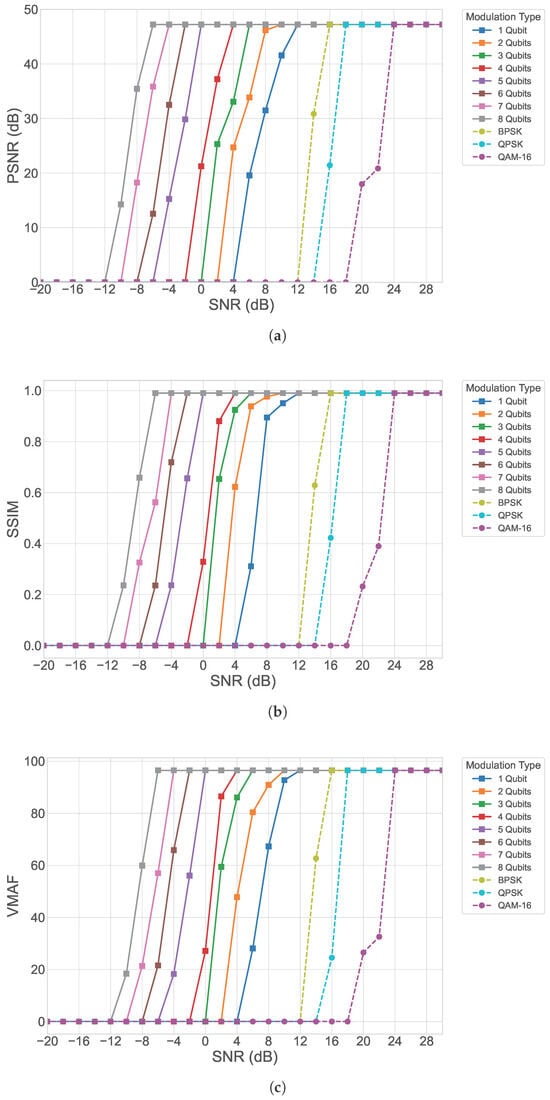

4.2. Performance Evaluation of the Proposed Quantum OFDM System in Urban Rayleigh Fading Environments

To further assess the robustness of the proposed quantum OFDM system, its performance under urban Rayleigh fading is evaluated using GOP8 video sequences, as shown in Figure 4. PSNR results (Figure 6a) show that increasing the qubit encoding size consistently improves reconstruction quality, demonstrating the scalability and efficiency of the quantum encoding approach. However, under severe fading, error resilience is lower compared to low-fading indoor environments. Higher qubit encoding forms higher-dimensional quantum states, allowing the system to encode and protect more information per symbol. This enhanced representation reduces the impact of amplitude and phase distortions typical of urban fading, resulting in higher PSNR values even at low-to-moderate SNRs. Compared with classical OFDM schemes such as BPSK, QPSK, and 16-QAM, quantum OFDM provides consistently better frame fidelity, with the performance advantage becoming more pronounced at low-to-medium SNR levels. These results suggest that quantum encoding preserves the integrity of I- and P-frames, ensuring smoother temporal consistency across the GOP despite challenging urban channels.

Figure 6.

Performance analysis of the proposed quantum OFDM system for GOP8 in urban Rayleigh fading channels (a) PSNR, (b) SSIM, and (c) VMAF.

The SSIM metrics (Figure 6b) further confirm the visual superiority of quantum OFDM. Higher SSIM values across all qubit sizes and SNR levels show that quantum OFDM preserves edges, textures, and inter-frame structural relationships. The results demonstrate that quantum OFDM substantially reduces this error propagation, maintaining both spatial and temporal coherence even under fast-varying urban fading conditions. VMAF-based perceptual analysis (Figure 6c) reinforces the benefits of the proposed quantum OFDM framework. Across the evaluated SNR range, quantum OFDM consistently outperforms classical OFDM, with the performance gap widening as the encoding qubit size increases.

Together, the PSNR, SSIM, and VMAF results demonstrate that quantum OFDM significantly enhances video transmission quality for GOP8 sequences in urban Rayleigh fading channels. The increasing performance gains with higher qubit sizes confirm that quantum encoding improves resilience both at the frame level and across temporal structures, highlighting quantum OFDM as a promising approach for next-generation video communications in urban environments.

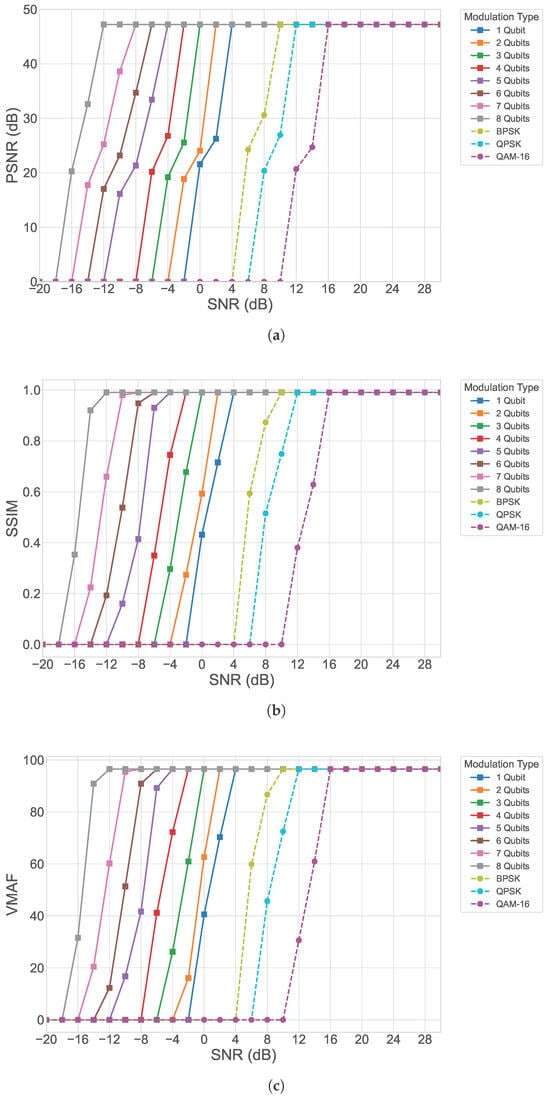

4.3. Performance Evaluation of the Proposed Quantum OFDM System in AWGN Channels

To evaluate the performance of the proposed quantum OFDM system under an AWGN channel, GOP8 video sequences are transmitted and analyzed. Unlike Rayleigh fading, AWGN introduces only AWGN noise without multipath or rapid channel variations, providing a baseline scenario to assess the inherent robustness of quantum encoding. The PSNR results, shown in Figure 7a, indicate that increasing the qubit encoding size enhances reconstruction quality. Increasing the qubit encoding size produces higher-dimensional quantum states and a greater number of quantum subcarriers, thereby enabling each transmitted symbol to carry more information. This reduces the impact of noise on the transmitted frames, resulting in consistently higher PSNR values compared to classical OFDM schemes such as BPSK, QPSK, and 16-QAM, particularly at low-to-moderate SNR levels.

Figure 7.

Performance analysis of the proposed quantum OFDM system for GOP8 in AWGN channels (a) PSNR, (b) SSIM, and (c) VMAF.

SSIM analysis, presented in Figure 7b, shows that quantum OFDM effectively preserves structural details, edges, and textures across frames, maintaining strong spatial and temporal consistency within each GOP. The system mitigates error propagation, ensuring smoother video playback even under noisy conditions. Perceptual evaluation using VMAF, as shown in Figure 7c, further highlights the advantages of quantum OFDM. Across the SNR range, it achieves higher scores than classical OFDM. Overall, the PSNR, SSIM, and VMAF results demonstrate that quantum OFDM substantially improves both objective and perceptual video quality for GOP8. Performance continues to improve with higher qubit sizes, underscoring the efficiency and robustness of quantum encoding even in noise-limited scenarios.

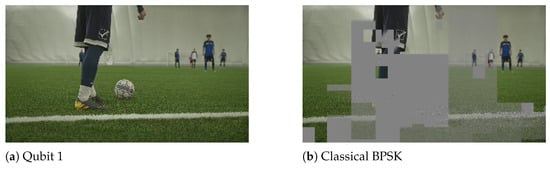

As shown in Figure 8, the images depict sample decoded video frames obtained from the proposed quantum OFDM system for a GOP of 8 under an urban Raleigh fading channel at SNR 13 dB. The first frame corresponds to a single-qubit configuration, while the second frame illustrates the decoded result for the classical BPSK system. The visual comparison of these frames is consistent with the objective quality evaluations, confirming the system’s reliable performance under severe fading conditions. The results further indicate that even with a single-qubit configuration, the proposed quantum OFDM system outperforms the best classical OFDM implementation, demonstrating its superior performance in terms of reconstructed video quality under the given channel conditions.

Figure 8.

Sample decoded video frames for GOP8 sequences under urban Rayleigh fading channel at SNR 13 dB.

We further evaluate the proposed quantum OFDM system for three different motion types and video resolutions, namely , , and , and compare its performance against a classical BPSK-modulated OFDM system, as summarized in Table 2. The results indicate that the SNR gains are generally consistent across all motion types and resolutions, suggesting that the proposed system operates independently of the input video resolution. The channel SNR gains observed for different motion types and video resolutions are near similar because noise affects both the quantum OFDM and classical BPSK-OFDM systems in the same manner; therefore, the relative SNR improvement provided by quantum OFDM remains consistent across motions and resolutions. In all cases, increasing the qubit encoding size leads to progressively higher SNR improvements, demonstrating the scalability, robustness, and effectiveness of the proposed quantum OFDM approach across different motion types and spatial resolutions.

Table 2.

Maximum SNR gains of quantum OFDM over classical BPSK for urban Rayleigh fading channel across different qubit sizes, video resolutions, and motion types (in dB).

4.4. Discussion

The proposed quantum OFDM framework offers significant advantages over classical OFDM schemes, making it highly suitable for high-fidelity video transmission. Its strength lies in the exploitation of fundamental quantum mechanical properties, such as superposition and high-dimensional Hilbert spaces, to encode information. Unlike classical modulation, where each subcarrier is assigned a fixed amplitude and phase, quantum OFDM allows multiple logical states to coexist simultaneously within a single qubit or qubit block. This capability enables the system to carry more information per transmitted symbol and provides inherent robustness against channel impairments.

Another key advantage of quantum OFDM is its enhanced error resilience. By using multi-qubit encoding, data is represented in higher-dimensional quantum states that are less susceptible to noise and fading. When combined with QFT-based subcarrier mapping, the encoded information is distributed across orthogonal quantum subcarriers, further reducing the impact of channel impairments. Errors are thus probabilistically spread across the quantum superposition and subcarriers, minimizing the likelihood of error propagation between dependent frames in GOP sequences. This approach ensures that both spatial and temporal consistency is preserved, even under challenging indoor and urban Rayleigh fading conditions.

Power efficiency is also a notable strength of quantum OFDM. Classical OFDM schemes such as BPSK, QPSK, and 16-QAM suffer from high PAPR, typically in the range of 10–12 dB, which can cause signal distortion and inefficient power usage. In contrast, quantum OFDM employs normalized quantum states and unitary QFT operations, ensuring that the total energy is evenly distributed across all quantum subcarriers. As a result, the instantaneous power equals the average power, resulting in a PAPR of 0 dB. This eliminates the high-power spikes observed in classical modulation schemes and significantly improves transmission efficiency, making quantum OFDM particularly advantageous for energy-constrained and high-fidelity video transmission scenarios.

Quantum OFDM is highly scalable and flexible. The system can be configured with different qubit sizes depending on the desired trade-off between performance and computational complexity. Larger qubit blocks improve reconstruction fidelity and robustness, while smaller blocks offer manageable complexity and lower latency. This adaptability allows the system to support different video resolutions, frame rates, and real-time application requirements.

The framework also demonstrates superior temporal and spatial fidelity. Quantum encoding reduces error propagation and preserves correlations between subcarriers, enabling higher-quality frame reconstruction compared to classical OFDM. This is especially important for GOP-based video sequences, where errors in early frames can propagate to subsequent P-frames. Additionally, the QFT enables efficient frequency-domain representation, which improves spectral utilization and reduces inter-subcarrier interference, further enhancing the robustness of the transmission.

4.4.1. Computation Complexity Analysis

The computational efficiency of the proposed quantum OFDM system is primarily determined by the QFT, which is used to encode and decode information across multiple qubits. For an input of size , the QFT requires only quantum gates, significantly lower than the operations required for a classical FFT/IFFT implementation. This quadratic scaling enables efficient implementation for small to medium-sized qubit systems, while still supporting high-dimensional encoding for improved robustness.

As the number of qubits increases, the system complexity grows due to additional quantum gate operations and deeper circuits. Specifically, each qubit requires one Hadamard gate, while the number of controlled phase gates scales as . Consequently, the total gate count increases roughly quadratically with the number of qubits, and the circuit depth grows approximately linearly with . Table 3 summarizes the estimated gate counts and circuit depths for representative qubit sizes. These values are approximate, as the final implementation depends on compiler optimizations, hardware-specific constraints, and the possible omission of SWAP gates.

Table 3.

Estimated QFT Resource Requirements for Different Qubit Sizes.

Overall, the QFT provides a significant computational advantage over classical Fourier transforms, especially for high-dimensional quantum encoding. While the complexity increases with qubit count, the quadratic scaling and relatively shallow circuit depth make quantum OFDM feasible for small and medium-scale quantum communication systems. This efficiency is crucial for supporting real-time video transmission and other high-throughput applications within practical hardware constraints.

4.4.2. Scalability and Future Applications

The proposed quantum OFDM framework exhibits strong scalability, allowing it to adapt to varying system requirements and application scenarios. By adjusting the number of qubits per block, the system can balance performance and computational complexity. Higher qubit encodings improve information density, error resilience, and reconstruction fidelity, making them suitable for high-resolution video or demanding multimedia applications. Smaller qubit encoding, on the other hand, reduce circuit depth and computational overhead, enabling lower latency and efficient operation for real-time streaming or resource-constrained hardware. This flexibility allows quantum OFDM to support different video resolutions, frame rates, and quality-of-service requirements, while maintaining robust performance across varying channel conditions.

Based on the evaluation, quantum OFDM is particularly well-suited for next-generation multimedia and communication applications. Its low PAPR, energy-efficient quantum encoding, and robust error resilience make it ideal for real-time video streaming, AR/VR environments, interactive gaming, and smart surveillance systems. The system’s inherent ability to preserve both spatial and temporal fidelity ensures smooth playback even in challenging wireless channels, including fading-prone indoor and urban environments. Moreover, as quantum hardware matures, quantum OFDM can be integrated with hybrid classical-quantum architectures, enabling high-throughput, low-latency multimedia processing in practical deployment scenarios.

The framework also offers potential for future extensions beyond video transmission. For example, quantum OFDM can be adapted to multi-user communication, large-scale sensor networks, or high-speed quantum data links where energy efficiency, low error rates, and robust performance are critical. Its scalability and modularity allow researchers to explore higher-dimensional quantum encodings, advanced error-correcting codes, and integration with emerging quantum communication protocols, paving the way for next-generation quantum-enhanced communication systems.

4.4.3. Simulation Nature and Hardware Feasibility

The results presented in this work are obtained through comprehensive simulation studies, which allow detailed evaluation of the proposed quantum OFDM system under controlled channel conditions. Simulations provide a flexible platform to analyze the impact of different qubit sizes and GOP structures on video quality metrics such as PSNR, SSIM, and VMAF. They also enable exploration of various SNR levels and resolution settings without the constraints imposed by current quantum hardware limitations. By isolating specific system parameters, the simulation studies provide valuable insights into the fundamental behavior and performance trends of quantum OFDM. This approach aligns with the standard practice in early-stage communication system research, where simulations serve as a foundation for guiding experimental design and subsequent optimization.

Despite the promising simulation results, practical implementation of quantum OFDM is currently limited by existing quantum hardware capabilities. Key challenges include restricted qubit counts, short coherence times, imperfect gate fidelities, and limited quantum memory, which impact the precision and scalability of essential operations such as QFT and IQFT. Additionally, integrating quantum modules with classical control and decoding units requires careful synchronization and low-latency interfacing, which remains a significant engineering challenge. However, rapid advancements in quantum hardware, including error-corrected qubits, improved gate fidelity, and scalable architectures, are steadily closing these gaps. The simulation results serve as a theoretical benchmark and proof-of-concept, demonstrating the system’s potential performance and providing guidance for future experimental validation. As quantum technologies mature, these insights will facilitate the transition from simulation-based evaluation to practical, real-time implementations of high-fidelity quantum video transmission systems.

5. Conclusions

This work introduces a quantum OFDM framework for high-fidelity video transmission over various channel conditions, with conclusions derived from the SNR gain metric explicitly conditioned on the simulation assumptions, including perfect CSI, and the evaluated video sequences. By combining multi-qubit encoding, the QFT, and classical channel coding with VVC-compressed video sequences, the system effectively mitigates the effects of noise, fading, and interference. Experimental evaluations across multiple GOP sizes (8, 16, and 32) demonstrate that quantum OFDM consistently outperforms classical OFDM schemes. The proposed system achieves PSNR up to 47.60 dB, SSIM up to 0.9987, and VMAF up to 96.40, with the eight-qubit configuration providing the largest SNR gains, approximately 22 dB under urban Rayleigh fading channel compared to classical baselines. This performance gain arises from quantum OFDM’s use of higher-dimensional quantum states and QFT-generated orthogonal subcarriers, which enable more efficient spectral usage, improved noise averaging, and enhanced resilience to amplitude and phase distortions. The results highlight quantum OFDM’s ability to maintain spatial and temporal consistency in video frames, reduce error propagation, and deliver superior perceptual quality under both stationary and rapidly varying channel conditions. These findings confirm that quantum OFDM is a highly promising approach for next-generation quantum video communication.

Future work will focus on enhancing both the practicality and performance of the quantum OFDM framework. The first objective will be to develop low-complexity QEC schemes specifically optimized for quantum OFDM, improving resilience to noise and fading while keeping computational demands reasonable. In parallel, adaptive qubit allocation strategies will be investigated to dynamically assign qubits according to video complexity and latency requirements, thereby optimizing transmission efficiency and perceptual video quality. Unlike the current study, which assumes perfect CSI, these future extensions will incorporate imperfect CSI, obtained through quantum pilot-assisted estimation, to better reflect practical channel conditions. Finally, the advanced quantum OFDM system, integrating QEC, adaptive qubit allocation, and realistic CSI, will be extended to high-dimensional MIMO-OFDM scenarios, enabling multi-user, high-throughput quantum video transmission with maximized spectral efficiency and robustness. Collectively, these developments aim to transition quantum OFDM from a simulation-based proof-of-concept toward a scalable, practical solution capable of delivering high-fidelity video over realistic quantum communication channels.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, U.J.; methodology, U.J.; software, U.J.; validation, U.J. and A.F.; formal analysis, A.F.; investigation, A.F.; resources, U.J.; data curation, U.J.; writing—original draft preparation, U.J.; writing—review and editing, A.F.; visualization, U.J.; supervision, A.F.; project administration, A.F. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original data presented in the study are openly available at https://www.pexels.com (accessed on 1 December 2025) under the Creative Commons Zero (CC0) license, which allows free use, distribution, and modification without attribution.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

| CSI | Channel State Information |

| CP | Cyclic Prefix |

| GOP | Group of Pictures |

| ICI | Inter Carrier Interference |

| IQFT | Inverse Quantum Fourier Transform |

| ISI | Inter Symbol Interference |

| LDPC | Low-Density Parity-Check |

| MIMO | Multi-Input Multi-Output |

| OFDM | Orthogonal Frequency-Division Multiplexing |

| PSNR | Peak Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| QEC | Quantum Error Correction |

| QFT | Quantum Fourier Transform |

| QKD | Quantum Key Distribution |

| SI | Structural Information |

| SNR | Signal-to-Noise Ratio |

| SSIM | Structural Similarity Index Measure |

| TI | Temporal Information |

| VMAF | Video Multi-Method Assessment Fusion |

| VVC | Versatile Video Coding |

References

- Kim, J.; Jun, H. Vision-based location positioning using augmented reality for indoor navigation. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2008, 54, 954–962. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosedale, P. Virtual reality: The next disruptor: A new kind of world wide communication. IEEE Consum. Electron. Mag. 2017, 6, 48–50. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Lin, C.; Wei, X. Enabling on-demand internet video streaming services to multi-terminal users in large scale. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2009, 55, 1988–1996. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bross, B.; Wang, Y.K.; Ye, Y.; Liu, S.; Chen, J.; Sullivan, G.J.; Ohm, J.R. Overview of the Versatile Video Coding (VVC) Standard and its Applications. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2021, 31, 3736–3764. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Qian, L.P.; Wang, C.; Wang, Q.; Wu, M.; Wu, Y.; Yang, X. OFDM Receiver Design with Learning-Driven Automatic Modulation Recognition. IEEE Trans. Cogn. Commun. Netw. 2024, 10, 429–441. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Parmar, S.J.; Parmar, V.R.; Verma, J.; Roy, S.; Bhattacharya, P. Quantum Computing: Exploring Superposition and Entanglement for Cutting-Edge Applications. In Proceedings of the 2023 16th International Conference on Security of Information and Networks (SIN), Barcelona, Spain, 13–17 March 2023; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sridhar, G.T.; P, A.; Tabassum, N. A Review on Quantum Communication and Computing. In Proceedings of the 2023 2nd International Conference on Applied Artificial Intelligence and Computing (ICAAIC), Salem, India, 4–6 May 2023; pp. 1592–1596. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Leong, W.Y.; Leong, Y.Z.; Leong, W.S. Quantum Consumer Technology: Advancements in Coherence, Error Correction, and Scalability. In Proceedings of the 2024 International Conference on Consumer Electronics—Taiwan (ICCE-Taiwan), Taichung, Taiwan, 9–11 July 2024; pp. 79–80. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singamaneni, K.K.; Muhammad, G.; Ali, Z. A Novel Multi-Qubit Quantum Key Distribution Ciphertext-Policy Attribute-Based Encryption Model to Improve Cloud Security for Consumers. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2024, 70, 1092–1101. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hosseiny, S.; Seyed-Yazdi, J.; Norouzi, M. Quantum teleportation via a hybrid channel and investigation of its success probability. Sci. Rep. 2024, 14, 26033. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Thakur, V.S.; Kumar, A.; Das, J.; Dev, K.; Magarini, M. Quantum Error Correction Codes in Consumer Technology: Modeling and Analysis. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2024, 70, 7102–7111. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jayasinghe, U.; Fernando, A. A Quantum OFDM Framework for High-Fidelity Image Transmission. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2025, 71, 9628–9636. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.S.; Loke, T.; Izaac, J.A.; Wang, J.B. Quantum Fourier transform in computational basis. Quantum Inf. Process. 2017, 16, 82. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sabaawi, A.; Almasaoodi, M.; Imre, S. Exploiting OFDM method for quantum communication. Quantum Inf. Process. 2024, 23, 256. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ochoa Dominguez, H.; Rao, K.R. Versatile Video Coding, 1st ed.; eBook published 1 September 2022; River Publishers: New York, NY, USA, 2018; p. 458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, C.; Sung, C.H.; Kuo, C.H.; Yen, M.H.; Chen, S.J. Design and implementation of a low-power OFDM receiver for wireless communications. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2012, 58, 739–745. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jha, S.; Ahmad, S.; Abdeljaber, H.A.M.; Othman, N.A.; Nazeer, J.; Yadav, K.; Alkhayyat, A.H. Enabling Resilient Wireless Networks: OFDMA-Based Algorithm for Enhanced Survivability and Privacy in 6G IoT Environments. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2024, 70, 3810–3819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ko, S.W.; Kim, J.H.; Yoon, J.S.; Song, H.K. Cooperative OFDM system for high throughput in wireless personal area networks. IEEE Trans. Consum. Electron. 2010, 56, 458–462. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, H.; Shao, Y.; Mikolajczyk, K.; Gündüz, D. Channel-Adaptive Wireless Image Transmission with OFDM. IEEE Wirel. Commun. Lett. 2022, 11, 2400–2404. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Costa, T.; Macedo, A.; Matos, E.; Castro, B.; Farias, F.; Cardoso, C.; Cavalcante, G.; Barros, F. A Temporal Methodology for Assessing the Performance of Concatenated Codes in OFDM Systems for 4K-UHD Video Transmission. Appl. Sci. 2024, 14, 3581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Hu, L.; Xu, W.; Wang, L. Design of an OFDM-based Differential Cyclic-Shifted DCSK System for Underwater Acoustic Communications. In Proceedings of the 2021 26th IEEE Asia-Pacific Conference on Communications (APCC), Kuala Lumpur, Malaysia, 11–13 October 2021; pp. 304–309. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Elsayed, E.E. Investigations on OFDM UAV-based free-space optical transmission system with scintillation mitigation for optical wireless communication-to-ground links in atmospheric turbulence. Opt. Quantum Electron. 2024, 56, 837. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cai, X.; Xu, W.; Wang, L.; Kaddoum, G. Joint Energy and Correlation Detection Assisted Non-Coherent OFDM-DCSK System for Underwater Acoustic Communications. IEEE Trans. Commun. 2022, 70, 3742–3759. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Paul, S.P.; Vetrithangam, D. A Thorough Assessment on Orthogonal Frequency Division Multiplexing (OFDM) based Wireless Communication: Challenges and Interpretation. In Proceedings of the 2023 International Conference on Sustainable Computing and Smart Systems (ICSCSS), Coimbatore, India, 14–16 June 2023; pp. 1145–1151. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hasan, S.R.; Chowdhury, M.Z.; Sayem, M.; Jang, Y.M. Quantum Communication Systems: Vision, Protocols, Applications, and Challenges. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 15855–15877. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shafique, M.A.; Munir, A.; Latif, I. Quantum Computing: Circuits, Algorithms, and Applications. IEEE Access 2024, 12, 22296–22314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]