Abstract

Mature soybean pods exhibit high homogeneity in color and texture relative to straw and dead leaves, and instances are often densely occluded, posing significant challenges for accurate field segmentation. To address these challenges, this paper constructs a high-quality field-based mature soybean dataset and proposes an adaptive Transformer-based network, PodFormer, to improve segmentation performance under homogeneous backgrounds, dense distributions, and severe occlusions. PodFormer integrates three core innovations: (1) the Adaptive Wavelet Detail Enhancement (AWDE) module, which strengthens high-frequency boundary cues to alleviate weak-boundary ambiguities; (2) the Density-Guided Query Initialization (DGQI) module, which injects scale and density priors to enhance instance detection in both sparse and densely clustered regions; and (3) the Mask Feedback Gated Refinement (MFGR) layer, which leverages mask confidence to adaptively refine query updates, enabling more accurate separation of adhered or occluded instances. Experimental results show that PodFormer achieves relative improvements of 6.7% and 5.4% in mAP50 and mAP50-95, substantially outperforming state-of-the-art methods. It further demonstrates strong generalization capabilities on real-world field datasets and cross-domain wheat-ear datasets, thereby providing a reliable perception foundation for structural trait recognition in intelligent soybean harvesting systems.

1. Introduction

Soybeans are a vital grain and oil crop, and their yield is influenced by key structural traits such as pod number, lowest pod position, and spatial distribution. These traits not only reflect the plant’s yield potential but also serve as essential indicators for assessing harvest losses and optimizing operational parameters [1,2]. However, mature soybean plants typically exhibit a uniform yellowish-brown coloration, resulting in a highly homogeneous background. Pods, senescent leaves, and straw show pronounced similarities in texture and brightness, and densely clustered instances frequently obscure one another. These characteristics hinder manual surveys from efficiently and accurately capturing structural traits, thus failing to meet the high-throughput requirements of breeding phenotyping and field operations [3]. Therefore, there is an urgent need for a visual model capable of robustly identifying and separating individual pod instances in complex field environments, thereby enabling the automated and efficient acquisition of key structural traits in mature soybeans.

Existing studies on automated phenotypic extraction of soybean pods can be broadly classified, based on scene complexity, into three categories: laboratory-controlled environments, potted-plant or single-plant close-up scenarios, and real-world field settings.

In laboratory-controlled environments, researchers commonly employ artificial backgrounds (e.g., black-light-absorbing cloth) to simplify visual processing and primarily focus on improving recognition accuracy. For high-throughput counting of isolated pods, Yu et al. [4] developed the lightweight PodNet, which performs efficient pod counting and localization via an enhanced decoder design. Yang et al. [5] introduced the RefinePod instance segmentation network for estimating seed counts per pod, alleviating fine-grained classification challenges through synthetic data training. To address structural phenotyping and occlusion issues in whole plants, Zhou et al. [6] integrated an attention-enhanced YOLOv5 with an search algorithm to extract traits such as plant height and branch length under black backdrops. Wu et al. [7] proposed the GenPoD framework, incorporating generative data augmentation and multi-stage transfer learning to reduce the impacts of class imbalance and foliage occlusion in on-branch pod detection. However, the stable lighting and uniform backgrounds in laboratory conditions substantially limit the transferability of these methods to complex field scenarios, making them unsuitable for direct application to mature soybean pod analysis in natural environments.

Under potted-plant or close-up single-plant conditions, existing studies primarily aim to improve pod detection and counting performance under relatively simplified backgrounds. Jia et al. [8] proposed YOLOv8n-POD, an enhanced version of YOLOv8n that incorporates a dense-block backbone to better accommodate diverse pod morphologies. Liu et al. [9] introduced SmartPod, integrating a Transformer backbone with an efficient attention mechanism to achieve stable pod detection and counting in single-plant ground-level settings. He et al. [10] embedded coordinate attention into YOLOv5 to enable accurate pod identification across multiple growth stages of potted plants. Building on this, He et al. [11] reformulated pod phenotyping as a human pose estimation task and proposed DEKR-SPrior for seed-level detection and separation of densely occluded pods under white backdrops. Xu et al. [12] developed DARFP-SD for detecting dense pods against black velvet backgrounds, improving counting accuracy in crowded scenes through deformable attention and a recursive feature pyramid. Although these studies enhance plant-structure recognition to some extent, their reliance on controlled backgrounds and relatively low-density plant conditions limits their applicability to real field environments, where mature pods exhibit high-density adhesion and substantial multi-scale variability.

In real-world field environments, existing research has primarily concentrated on object detection and density estimation. Some studies have achieved dynamic field pod detection using multi-scale attention or improved YOLO variants [13,14,15], while others have addressed high-density counting challenges through point supervision and density-map regression [16,17,18]. However, research on instance-level segmentation remains limited. Although Zhou et al. [19] investigated lightweight segmentation networks, they reported that mature soybean plants exhibit homogeneous yellowish-brown textures, weak boundaries, and high-density clustering, all of which severely compromise traditional models, leading to instance coalescence and segmentation omissions. Existing approaches therefore remain centered on detection or counting tasks and exhibit notable limitations in weak-boundary segmentation, instance decoupling in dense regions, and precise mask generation under complex field backgrounds.

Instance segmentation of mature soybean pods still lacks a unified and robust solution capable of operating reliably in complex field environments. The key challenges include (1) weak boundaries arising from the high homogeneity in texture and color among pods, straw, and senescent leaves; (2) pronounced scale and density discrepancies between upper and lower canopy regions; and (3) mask adhesion and instance overlap resulting from natural lighting variations, reflections, and occlusions. These challenges collectively constrain the robustness and reliability of existing methods in real-world field applications.

To address these challenges, this paper proposes PodFormer, an instance segmentation framework specifically designed for real-world field conditions. The main contributions of this work are summarized as follows:

- A high-quality field dataset of mature soybean pods is constructed, covering diverse cultivation patterns and lighting conditions. It provides abundant samples featuring homogeneous backgrounds and densely clustered pods, thereby mitigating the scarcity of data in complex scenarios.

- An Adaptive Wavelet Detail Enhancement (AWDE) module is proposed, which employs attention-weighted wavelet transformations to amplify high-frequency boundary cues and alleviate weak-boundary issues caused by homogeneous textures.

- A Density-Guided Query Initialization (DGQI) module is designed, leveraging multi-scale density priors to modulate query initialization, explicitly model scale and density variations, and improve instance-awareness under non-uniform distributions.

- A Mask Feedback Gated Refinement (MFGR) layer is introduced, which incorporates preceding-layer mask quality as feedback and utilizes a dual-path gating mechanism to adaptively refine queries, enabling precise instance separation under severe occlusion and adhesion.

2. Materials and Methods

2.1. Field-Mature Soybean Dataset

2.1.1. Field Experiment Design

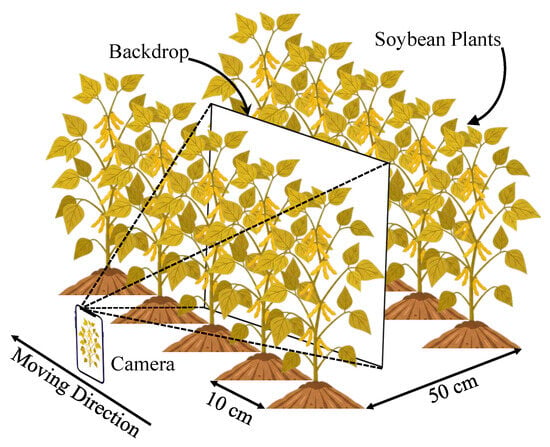

Data collection for this study was conducted in the demonstration field of Henan University of Science and Technology in Xinxiang County, Xinxiang City, Henan Province ( E, N), using the salt-tolerant soybean cultivar “Qihuang 34.” To ensure data diversity and robustness, the experiment included six nitrogen fertilizer treatments and two cropping systems: a pure soybean system consisting of 16 soybean rows, and a mixed cropping system consisting of two corn rows and two soybean rows. In the pure soybean system, the row spacing was 50 cm and the plant spacing was 10 cm. In the mixed cropping system, the soybean–corn row spacing was 50 cm, with plant spacings of 20 cm for corn and 10 cm for soybean. All experiments adopted a three-replicate randomized design to ensure balanced and representative data across the different treatment conditions.

2.1.2. Image Acquisition Method

This study employed a Xiaomi 13 smartphone to capture individual soybean plants using a m × m white background panel as an isolation screen. This setup effectively isolated adjacent crop rows in dense field environments, thereby reducing background homogeneity interference and enhancing target-plant separability. All images were collected during the maturity stage (late September) under overcast, drizzly, and sunny conditions and across early-morning, midday, and late-afternoon light periods to enhance the model’s robustness to illumination variability. During image acquisition, operators photographed plants from the side of the crop rows, positioning the background panel behind the target plants and adjusting the shooting distance to ensure complete plant coverage, as illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Schematic diagram of field soybean image acquisition.

During image acquisition, a portable white background board was deliberately positioned behind the target plants to enhance dataset quality and model reliability. This experimental design physically isolates the Region of Interest (ROI) from complex, unstructured field backgrounds—such as weeds and overlapping foliage—thus substantially improving target contrast. Furthermore, the uniform background creates distinct object boundaries, which facilitates high-precision pixel-level annotation for ground-truth generation and reduces environmental interference, thereby compelling the network to focus on intrinsic morphological features rather than overfitting to background noise.

To ensure data diversity and reduce the risk of overfitting, the data acquisition process followed three guiding principles: (1) Diversity: collect 50 images per nitrogen fertilizer treatment and planting method; (2) Representativeness: sample plants from both middle and edge rows within pure soybean planting patterns; and (3) Independence: photograph each plant only once to avoid duplicate sampling. Ultimately, a total of 1800 high-resolution RGB images were collected, all stored at a uniform resolution of pixels to preserve fine textural details.

2.1.3. Image Screening and Instance Annotation

Prior to annotation, all 1800 original images were manually screened, and low-quality samples with compromised subject information—caused by motion blur, focus failure, or severe occlusion from non-target objects—were removed. Ultimately, 1510 images were retained for subsequent annotation. Although the total number of images is moderate, each high-resolution sample () contains a high density of pod instances—ranging from dozens to hundreds—thereby contributing to a large volume of instance-level training targets. Furthermore, the dataset’s broad coverage of diverse lighting conditions, cropping patterns, and growth treatments ensures substantial feature variability, enabling the model to learn robust representations and reducing the risk of overfitting. Pixel-level instance annotation of soybean pods was performed using the open-source tool X-AnyLabeling [20], in combination with the prompt-based segmentation capability of the Segment Anything Model (SAM) [21] to enhance annotation efficiency. The annotation workflow consisted of two main steps: (1) generating candidate masks using SAM-derived prompt points, and (2) manually refining each mask to correct boundary drift, misclassification, and recover omitted pod instances. Finally, the annotated dataset was divided into training, validation, and test sets in a 7:2:1 ratio for training and evaluating the proposed PodFormer model.

2.2. PodFormer

To address segmentation challenges arising from homogeneous backgrounds, scale and density inhomogeneities, and severe occlusion and adhesion in mature soybean fields, this paper proposes PodFormer—a lightweight, robust, and highly generalizable instance segmentation network built upon the Mask2Former [22] framework. By optimizing backbone feature extraction, query initialization, and Transformer decoding, the model achieves end-to-end prediction from raw RGB images to instance masks.

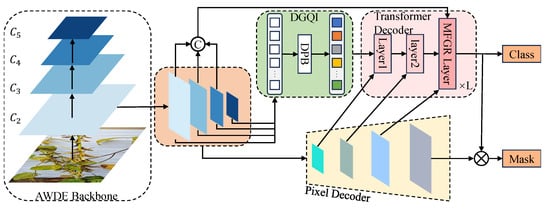

As illustrated in Figure 2, PodFormer integrates three key modules into the original backbone, pixel decoder, and Transformer decoder architecture: the Adaptive Wavelet Detail Enhancement (AWDE) module, the Density-Guided Query Initialization (DGQI) module, and the Mask Feedback Gated Refinement (MFGR) layer. Specifically, AWDE enhances edge details through attention-weighted wavelet transforms; DGQI fuses multi-scale features with density predictions to inject explicit scale and density priors into the queries; and MFGR refines the queries using a dual-path gating mechanism guided by the previous layer’s mask, thereby improving instance discrimination under occlusion and adhesion. The refined queries are subsequently fed into the prediction head to generate high-quality classification scores and instance masks.

Figure 2.

Overview of the Network Architecture.

2.2.1. Adaptive Wavelet Detail Enhancement (AWDE)

In field-based instance segmentation of mature soybean pods, the strong homogeneity between targets and background makes pods nearly indistinguishable from dry straw in both color and texture, resulting in extremely weak and ambiguous boundaries. Traditional convolutional networks rely on max pooling for spatial downsampling and receptive field expansion, but such operations inevitably discard critical high-frequency information—particularly edges and fine-grained textures—making it difficult for models to reconstruct clear and complete pod contours during decoding. To improve boundary discriminability, this paper proposes the Adaptive Wavelet Detail Enhancement (AWDE) module. The module replaces fixed pooling with a learnable wavelet transform and applies an attention mechanism to high-frequency subbands. This design adaptively amplifies edge-related high-frequency details while suppressing homogeneous background noise, thereby enhancing weak-boundary segmentation performance from the earliest stage of feature extraction.

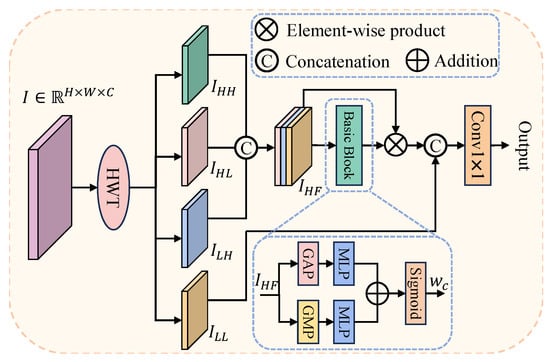

The detailed structure of the AWDE module is illustrated in Figure 3. The AWDE module is used exclusively to replace the initial max-pooling layer in the ResNet-50 [23] backbone, which is located after the convolutional layer and before the beginning of Stage 1. The subsequent downsampling stages (Stages 2, 3, 4) continue to use the standard ResNet convolutional blocks.

Figure 3.

Architecture of the Adaptive Wavelet Detail Enhancement (AWDE) Module.

Given an input feature map , the AWDE module first applies the Haar wavelet transform [24] to losslessly decompose it into four subbands of size : (low-frequency component retaining contour information), (horizontal high-frequency), (vertical high-frequency), and (diagonal high-frequency). The three high-frequency subbands capture edge and texture details, providing fine-grained structural cues for subsequent processing.

The standard wavelet transform cannot discriminate between informative high-frequency components (e.g., pod edges) and noise-induced high-frequency responses (e.g., background textures). To address this limitation, we introduce a lightweight attention-gating mechanism termed High-Frequency Adaptive Gating. Specifically, the three high-frequency subbands , , and are concatenated along the channel dimension to form a high-frequency feature group . Subsequently, inspired by the channel-attention branch of the Shuffle Attention (SA) module [25], we aggregate spatial information using global average pooling and global max pooling. A shared MLP then generates a channel-weight vector :

where denotes global average pooling, refers to a multi-layer perceptron with shared weights, and represents the sigmoid activation function. The weighted high-frequency features are then obtained via element-wise, channel-wise multiplication:

where ⊗ denotes element-wise multiplication.

Finally, we concatenate the attention-filtered, enhanced high-frequency features with the low-frequency component . The concatenated features are then passed through a convolutional layer for cross-channel information fusion and dimensionality reduction (from to ), yielding the final downsampled output feature map .

This design enables the AWDE-enhanced backbone to adaptively strengthen pod-edge texture features during downsampling while simultaneously suppressing noise from homogeneous backgrounds. Compared with standard backbones, the module outputs sharper boundary representations and stronger semantic discriminability at the early backbone stages, thereby supplying higher-quality feature inputs to subsequent pixel decoders and query generators.

2.2.2. Density-Guided Query Initialization (DGQI)

Soybean pods in field environments exhibit substantial non-uniformity in both scale and spatial density. A single image may contain pods with large size variations and complex spatial distributions ranging from sparse to highly clustered. Traditional query initialization methods struggle to model multi-scale features and spatial density priors simultaneously, which often results in missed detections or false positives under extreme scale or density variations and ultimately compromises model convergence. To address these limitations, this paper proposes a Density-Guided Query Initialization (DGQI) module. Building upon context-aware multi-scale query initialization, the module introduces a parallel Density Prediction Branch (DPB) that modulates multi-scale features with predicted density priors. This design produces query representations capable of simultaneously encoding both scale and density cues.

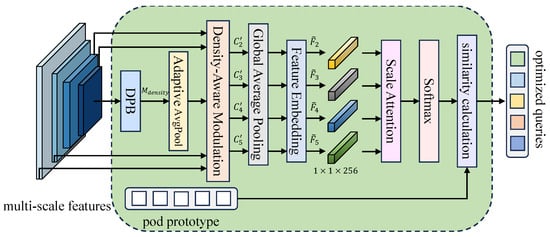

The detailed structure of DGQI is illustrated in Figure 4. The module’s inputs consist of (1) a set of learnable pod prototypes and (2) multi-scale backbone feature maps .

Figure 4.

Architecture of the Density-Guided Query Initialization (DGQI) Module.

First, to obtain the spatial density prior, the highest-resolution backbone feature map (resolution ) is fed into a lightweight DPB to generate a single-channel density heatmap . This heatmap is then downsampled to the resolutions of , , and via adaptive pooling and element-wise multiplied with all feature maps from through , yielding the density-modulated feature maps :

Subsequently, the four density-modulated feature maps are fed into the query generator. Although not explicitly shown in the diagram, all feature-map channels are first projected to 256 dimensions. Then, each feature map undergoes global average pooling, followed by flattening, to unify its dimensions and prepare for subsequent scale embedding. This operation can be expressed as follows:

Global average pooling (GAP) unifies feature maps of different spatial resolutions while preserving global contextual information across scales. Adding scale embeddings enables the model to distinguish and effectively utilize information from different scales, thereby enhancing feature representation capability. Here, denotes the learnable embedding associated with each scale. The Flatten operation converts from a spatial tensor into a 256-dimensional feature vector.

Subsequently, to compute the global attention weights that allow the model to evaluate the relative importance of each scale feature, we stack the four independent multi-scale feature vectors obtained in the previous step along a new dimension, forming a unified aggregated feature tensor :

Subsequently, the model uses the aggregated tensor to learn the attention weights through a linear layer, which compresses each C-dimensional feature vector into a single scalar, followed by a softmax function applied along the scale dimension. These weights determine the relative importance of each scale i during the final feature-fusion process.

Then, using the learned weights , we perform a weighted summation over the raw multi-scale feature vectors obtained in Equation (5) to obtain the final feature representation , which integrates both multi-scale information and density priors.

Finally, the similarity S is computed between the fused feature representation and the learnable pod prototype P, yielding the final query representation , which is enriched with both multi-scale characteristics and density-aware information:

where denotes the initial pod prototype, and represents the similarity scaling factor. The similarity computation S evaluates the matching degree between the initial prototype and the fused feature representation, thereby guiding the direction of subsequent query updates.

The context-aware initialization mechanism of DGQI integrates multi-scale representations with density priors, ultimately producing query embeddings that encode both hierarchical feature information and spatial priors. This design enriches the query’s prior knowledge, allowing for more effective interaction with pixel-decoder features and enhancing its capacity to capture discriminative target cues. Furthermore, initializing queries with feature-informed embeddings accelerates model convergence during training.

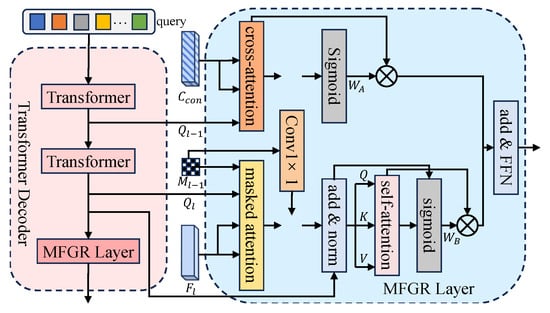

2.2.3. Mask Feedback Gated Refinement (MFGR)

In real-world field conditions, soybean pods often grow in dense clusters, with instances severely occluded and tightly adhered, which makes instance-level segmentation particularly challenging. The multi-layer Transformer decoder in standard Mask2Former is susceptible to interference from neighboring targets during query updates, resulting in cumulative feature contamination and causing multiple adhered pods to be incorrectly merged into a single instance. To address this problem, we propose the Mask-Feedback Gated Refinement (MFGR) layer. Building upon the dual-path gated architecture of GQT [26], MFGR incorporates the previous layer’s mask quality as an explicit confidence signal. This transforms query updates from indiscriminate iteration into adaptive refinement driven by segmentation quality, thereby substantially improving the model’s ability to distinguish occluded or fused instances.

As shown in Figure 5, the Transformer decoder comprises three decoding layers. The first two layers employ a standard masked-attention Transformer architecture, performing self-attention and cross-attention updates on the initial queries. The third layer introduces the proposed MFGR layer, replacing the traditional decoder-update mechanism. At the decoder layer l, the inputs to the MFGR module include the query output from the previous layer, the prediction mask from the previous layer, the current-layer query output , the aggregated feature , and the current scale feature .

Figure 5.

Architecture of the Mask Feedback Gated Refinement (MFGR) Layer.

Among these inputs, the current-scale feature is produced by the pixel decoder and corresponds to the input scale of the l-th Transformer-decoder layer. It captures local spatial structures and boundary information, serving as the primary input for the cross-attention operation. To enhance the global semantic representation used in the refinement path, we spatially align and channel-compress the multi-layer features extracted from the ResNet-50 backbone before concatenating them along the channel dimension to construct the aggregated feature :

(1) Dual-path processing within the decoder layer. The MFGR module adopts a dual-path architecture, generating two candidate query representations in parallel.

Feature Refinement Path (A). Cross-attention is performed between and the aggregated feature to obtain the candidate query , which aims to inherit and refine the feature representation from the previous decoder layer.

Feature Correction Path (B). The current-layer query undergoes standard mask-attention and self-attention operations with the current-scale feature to produce the candidate query , aiming to correct or recover information from the current layer’s feature representation.

(2) Mask-confidence encoding. We use the binary mask predicted at the previous decoder layer as the basis for estimating the query’s confidence level. The mask is encoded by a lightweight encoder (implemented as a convolution) to produce a compact confidence feature vector , where C denotes the query’s channel dimension:

In particular, the vector implicitly encodes the quality of the segmentation results produced by the previous decoder layer.

(3) Mask-guided gating. We concatenate the confidence vector with the candidate queries and from the two paths and compute the corresponding gating signals and using a linear transformation:

Subsequently, the final gating weights and are obtained by applying the sigmoid activation function :

(4) Gated fusion. Finally, we perform a weighted summation of the two candidate queries, producing the combined query :

where ⊗ denotes element-wise multiplication, and ⊕ denotes element-wise addition. The combined query is subsequently fed into the feed-forward network (FFN) to generate the final query output for decoder layer l.

The introduction of enhances the GQT gating mechanism by enabling adaptive adjustment of the fusion strategy based on the mask quality predicted by the previous decoder layer. When the mask quality is high, the model assigns a larger gating weight to the refinement path . Conversely, when the mask quality is low—such as under severe occlusion—the model places greater emphasis on the correction path to recover lost or corrupted features. This mechanism substantially improves segmentation accuracy in scenarios characterized by tight inter-pod adhesion and severe occlusion.

3. Experiments

This chapter aims to systematically evaluate the performance of the proposed PodFormer on the task of instance segmentation for mature soybean pods in real-world field settings. We first describe the experimental setup, including the training environment, implementation details, and evaluation metrics. Subsequently, we validate the independent contributions of each module through a series of ablation studies. We then conduct a comprehensive comparison with representative mainstream instance segmentation methods. Finally, we assess the model’s generalization capabilities in real-world field scenarios and across different crop domains.

3.1. Experimental Setup

3.1.1. Experimental Environment and Parameter Settings

The experimental hardware environment for this study comprises an AMD EPYC 7282 processor with 250 GB of memory, running the Ubuntu 18.04.6 LTS operating system. Training utilized an NVIDIA A100 GPU (80 GB, PCIe) with CUDA version 11.3. The model was implemented using Python 3.8 and the PyTorch 2.0 deep learning framework, with all input images uniformly resized to . Additional training parameters are detailed in Table 1.

Table 1.

Training Model Parameters.

To ensure a rigorous and reliable evaluation, the experiments were conducted using the self-constructed dataset described in Section 2.1.3. This dataset comprises 1510 images, which were randomly partitioned into training, validation, and test sets using a 7:2:1 split. In total, it contains approximately 55,000 annotated instances, providing a diverse and representative basis for comprehensive model evaluation.

3.1.2. Evaluation Metrics

In the instance-segmentation task for mature soybean pods in the field, this study employed a series of evaluation metrics, including Precision, Recall, and localization accuracy (mAP50 and mAP50–95). In image-segmentation tasks, accurately assessing model performance through visual inspection alone is often challenging due to the subtle differences between segmentation results. Consequently, these metrics provide a clearer and more objective quantitative assessment of model performance. The formulas for computing these metrics are as follows:

among which denotes the number of true positive predictions, denotes the number of false positive predictions, and denotes the number of false negative predictions.

mAP (mean Average Precision) represents the mean of the Average Precision (AP) values computed for all categories, providing an overall measure of detection accuracy. denotes the AP computed at a fixed Intersection over Union (IoU) threshold of 0.5. mAP50–95 computes the mean AP across IoU thresholds ranging from 0.5 to 0.95 at increments of 0.05, enabling a more fine-grained evaluation of model performance under varying degrees of overlap. The formula for computing mAP is as follows:

where denotes the area under the precision–recall curve and N represents the total number of categories.

3.2. Ablation Study

To quantitatively evaluate the effectiveness of each innovative module in PodFormer, this section presents a series of ablation experiments. Mask2Former is adopted as the baseline model, and we systematically analyze the impact of different module combinations on field pod instance segmentation performance by progressively incorporating the Adaptive Wavelet Detail Enhancement (AWDE) module, the Density-Guided Query Initialization (DGQI) module, and the Mask Feedback Gated Refinement (MFGR) layer. All ablation experiments were conducted on the self-built field-mature soybean dataset using the same training parameters and evaluation metrics as those employed in the comparative experiments. The results are summarized in Table 2, where a “✓” indicates that the corresponding module is enabled in the current configuration.

Table 2.

Ablation Performance Comparison of Different Module Combinations.

As shown in Table 2, the baseline model Mask2Former (Group A) provides basic segmentation capability but achieves the lowest performance across all metrics (mAP50 = 0.728, mAP50–95 = 0.342). This result indicates that standard models struggle to handle homogeneous backgrounds, uneven density distributions, and severe occlusions in real field environments.

After introducing each module individually (Groups B, C, and D), the model exhibits performance improvements to varying degrees. AWDE (Group B) increases mAP50 to 0.740 and mAP50–95 to 0.355, demonstrating that enhancing high-frequency boundary cues through wavelet transformation and attention mechanisms effectively suppresses false detections arising from homogeneous backgrounds such as fallen leaves and straw. DGQI (Group C) further improves mAP50 to 0.745 and substantially increases recall from 0.646 to 0.670, indicating that incorporating density priors enables better detection of pods in both sparse and densely clustered regions. MFGR (Group D) yields the highest gain among individual modules, raising mAP50 to 0.750 and mAP50–95 to 0.360, as mask-quality feedback and gated refinement mitigate feature contamination caused by adhesion and occlusion.

When modules are combined in pairs (Groups E, F, and G), performance improves across all metrics. Notably, DGQI + MFGR (Group G) achieves strong recall (0.700) and improved fine-grained segmentation performance (mAP50–95 = 0.380), demonstrating that jointly modeling density cues and occlusion refinement enhances recognition in highly clustered regions.

Finally, when all three modules are integrated (Group H, i.e., PodFormer), the model achieves the best overall performance (mAP50 = 0.795, mAP50–95 = 0.396), with improvements of 6.7% and 5.4% over the baseline, respectively. In summary, the ablation experiments validate the effectiveness and complementary roles of the three modules: AWDE addresses homogeneous backgrounds and weak boundaries, DGQI models scale and density variations, and MFGR mitigates occlusion and adhesion effects. Their synergistic interaction substantially enhances the model’s robustness and segmentation accuracy in complex field environments.

3.3. Comparative Experiments

To comprehensively validate PodFormer’s performance advantages in mature soybean pod instance segmentation, this study compares it with several representative instance segmentation methods, including YOLOv8-Seg [27], YOLOv11-Seg [28], Mask R-CNN [29], SegFormer [30], and Mask2Former [22] as the baseline model. All models were trained and evaluated under identical experimental settings on the self-built dataset, and their performance was measured using four metrics: Precision, Recall, mAP50, and mAP50–95. The detailed performance results for each method are summarized in Table 3.

Table 3.

Performance Comparison of Models on Field-Mature Soybean Pod Instance Segmentation (Optimal: Bold).

As shown in Table 3, the traditional instance segmentation model Mask R-CNN exhibits moderate performance, achieving an mAP50 of 0.722. Its mAP50–95 remains low at 0.331, indicating limited capability for fine-grained segmentation at higher IoU thresholds. The Transformer-based SegFormer performs even worse, attaining an mAP50 of only 0.715. YOLOv8-Seg provides a slight improvement (mAP50 = 0.726), while its enhanced variant YOLOv11-Seg reaches 0.784; however, it still underperforms in high-precision segmentation, with an mAP50–95 of 0.380. Mask2Former, adopted as the baseline model, achieves mAP50 and mAP50–95 scores of 0.728 and 0.342, respectively, but its recall (0.646) remains relatively low, reflecting persistent limitations in high-IoU segmentation quality.

Building upon this baseline, PodFormer integrates three key modules—AWDE, DGQI, and MFGR. AWDE strengthens high-frequency boundary cues, DGQI injects scale and density priors to enhance instance detection, and MFGR improves instance separation under occlusion and adhesion. Benefiting from the synergistic interaction of these modules, PodFormer achieves a Precision of 0.837, a Recall of 0.718, an mAP50 of 0.795, and an mAP50–95 of 0.396, outperforming all comparison models. Compared with Mask2Former, PodFormer improves mAP50 and mAP50–95 by 6.7% and 5.4%, respectively, demonstrating substantial performance gains.

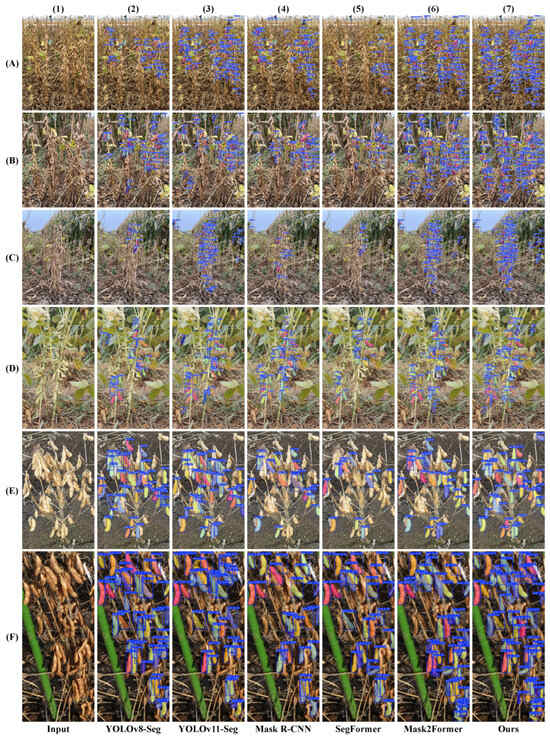

To visually illustrate the segmentation differences among models, Figure 6 presents representative prediction results on typical field images. Under two major challenges—homogeneous background interference and instance occlusion/adhesion—PodFormer consistently achieves more complete boundary reconstruction and clearer instance separation, demonstrating superior segmentation accuracy and robustness.

Figure 6.

Visual Comparison of Prediction Results for Field-Mature Soybean Pod Instance Segmentation. Panels (a–d) represent the subgraphs corresponding to (A–D), respectively.

In homogeneous background scenarios (Figure 6b,d), mature pods share high similarity in color and texture with dead leaves, straw, and soil, leading to widespread false detections in contrast-dependent models. For example, YOLOv8-Seg and Mask R-CNN frequently misidentify color-similar background textures as pods due to their limited boundary modeling capability. In contrast, PodFormer (Figure 6), equipped with AWDE to adaptively enhance high-frequency edge details, achieves more accurate discrimination between pods and homogeneous backgrounds, producing cleaner mask contours and substantially reducing false detections.

In dense occlusion scenarios (Figure 6a,c), pods frequently overlap and form tightly adhered clusters, presenting highly challenging segmentation cases. All comparison models exhibit missed detections and instance mergers, particularly in heavily occluded or densely clustered regions. For instance, in Figure 6a, only PodFormer successfully identifies and separates the occluded pod, and in Figure 6c the comparison models suffer from severe missed detections. Although PodFormer does not achieve perfect segmentation under extreme density, it separates more instances with higher accuracy and substantially outperforms other methods. This advantage primarily arises from the density priors introduced by DGQI and the mask-feedback refinement of MFGR, enabling stronger instance discrimination under extreme adhesion.

In summary, both quantitative and qualitative results demonstrate that PodFormer exhibits clear advantages in feature representation and instance-level consistency modeling, particularly in challenging field scenarios such as weak boundaries, high-density clusters, and severe occlusions. These strengths provide a reliable technical foundation for precise phenotyping analysis and yield estimation based on pod-level instance segmentation.

3.4. Generalization Ability Evaluation

To further evaluate the adaptability and generalization capability of the proposed PodFormer architecture across different scenarios, two sets of generalization experiments were conducted: validation in real field settings and cross-domain evaluation on a novel wheat-ear dataset.

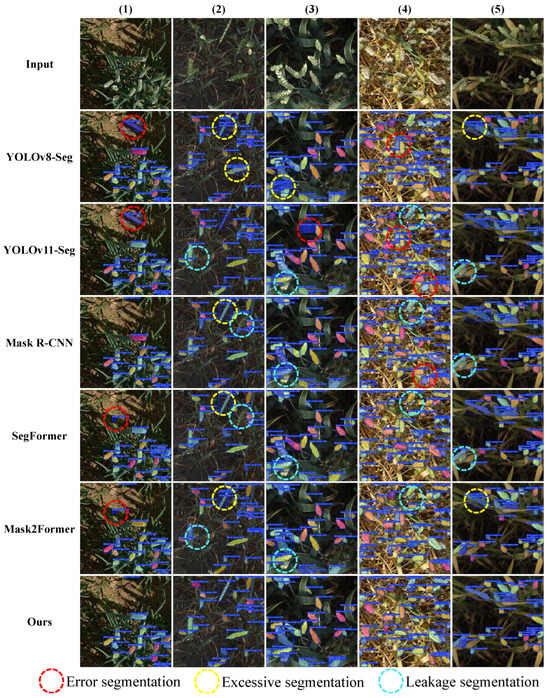

3.4.1. Real-World Field Scenario Generalization Testing

To evaluate the model’s robustness under real-world field conditions with variable illumination and complex backgrounds, this experiment extends beyond the controlled training environment that utilized a white background board. Multiple sets of unseen images were selected for evaluation (Figure 7), including self-collected field images without background boards (Figure 7A–D) and samples from two public datasets (Figure 7E,F). In these scenes, pods exhibit strong similarity in color and texture to withered branches, soil, weeds, and adjacent crop rows. The degree of background interference and occlusion far exceeds that of the training set, posing a rigorous challenge to the model’s robustness and domain-adaptation capability.

Figure 7.

Segmentation results of different models on field images without background panels. Panels (A–D) present self-collected field images, (E) shows an image from the 2021 dataset [8], and (F) displays an image from the P2PNet-Soy dataset [17].

To ensure fair evaluation, all comparison models (YOLOv8-Seg [27], YOLOv11-Seg [28], Mask R-CNN [29], SegFormer [30], and Mask2Former [22]) were directly applied using weights trained on the white-background dataset. Qualitative results for each method are presented in Figure 7.

As shown in Figure 7, the performance of all comparison models deteriorates markedly in highly challenging real-world field scenarios. Mask R-CNN (Figure 7(4)) and SegFormer (Figure 7(5)) fail almost entirely, producing numerous misclassifications caused by complex background textures. Although YOLOv8-Seg (Figure 7(2)), YOLOv11-Seg (Figure 7(3)), and Mask2Former (Figure 7(6)) can identify some pod instances, they still generate substantial false positives, false negatives, and severe instance merging in homogeneous or densely clustered regions (Figure 7C,E,F).

In contrast, PodFormer (Figure 7(7)) demonstrates the strongest generalization capability and stability across all tested images. AWDE enhances high-frequency boundary cues and effectively suppresses complex background noise; DGQI incorporates density priors that support robust localization in extremely dense regions (Figure 7A–C,F); and MFGR mitigates feature contamination caused by occlusions, enabling clearer separation of adhered pods.

To complement the qualitative comparison, Table 4 presents the quantitative performance of all models on real-world field images without background panels. As shown in the table, all methods exhibit varying degrees of performance degradation relative to the white-background evaluation, underscoring the substantial challenges posed by heterogeneous textures, illumination variations, and severe occlusions in natural field scenes. YOLOv8-Seg and YOLOv11-Seg maintain the highest inference speeds, but their mAP50–95 scores decline markedly due to their limited boundary modeling capability. Mask R-CNN, SegFormer, and Mask2Former likewise exhibit lower Recall and reduced fine-grained segmentation accuracy, indicating that conventional models struggle to maintain robustness under complex background interference.

Table 4.

Performance Comparison of Models on Real-World Field Images Without Background Panels (Optimal: Bold).

In contrast, PodFormer achieves the highest overall accuracy, improving mAP50 and mAP50–95 by 6.4% and 3.9%, respectively, over Mask2Former, while maintaining a competitive inference speed of 72.158 FPS. These results confirm that AWDE, DGQI, and MFGR effectively enhance boundary discrimination, density-aware instance detection, and occlusion resolution. Therefore, PodFormer demonstrates strong generalization capability and stable segmentation performance, even in challenging real-world field environments.

In summary, the generalization results demonstrate that PodFormer does not overfit to the white-background training conditions but instead exhibits strong cross-domain adaptability. By leveraging AWDE, DGQI, and MFGR, PodFormer maintains stable and accurate pod-level instance segmentation performance in real field environments, laying a solid foundation for practical deployment in agricultural applications.

3.4.2. Cross-Domain Generalization Testing

This experiment aims to evaluate whether PodFormer possesses cross-crop universality, specifically its ability to transfer to targets with completely different morphologies and background characteristics. To this end, a publicly available wheat-ear image dataset [31] was selected for cross-domain instance segmentation evaluation, comprising 760 images (523 for training, 160 for validation, and 77 for testing). This dataset imposes higher demands on the model. Wheat ears exhibit elongated, densely clustered strip-like structures that differ markedly from the clustered morphology of soybean pods. The background—comprising green leaves and dark soil—introduces substantial color and texture interference, and occlusion and adhesion between wheat ears and leaves are similarly severe. These factors jointly challenge the model’s capability in detail modeling, texture representation, and occlusion handling.

To ensure consistent evaluation, all comparison models (YOLOv8-Seg [27], YOLOv11-Seg [28], Mask R-CNN [29], SegFormer [30], and Mask2Former [22]) and the proposed PodFormer were trained and evaluated independently on the wheat-ear dataset using the same training hyperparameters described in Section 3.1. Precision, Recall, mAP50, and mAP50–95 were used to assess performance, and the results are summarized in Table 5.

Table 5.

Performance Comparison of Models on Wheat-Ear Instance Segmentation (Optimal: Bold).

As shown in Table 5, the clearer boundaries and more uniform structural characteristics of wheat ears lead all models to exhibit substantially better performance on this dataset compared with their results on the self-built soybean dataset. In this relatively easier cross-domain task, PodFormer continues to achieve the best performance, demonstrating stable generalization capability.

Among the comparison methods, the Transformer-based SegFormer performs the weakest (mAP50–95 = 0.645), indicating limited capability in modeling instance-level local details. YOLOv8-Seg, YOLOv11-Seg, and Mask R-CNN achieve comparable accuracy but still underperform in boundary refinement. Mask2Former, as the baseline model, leverages its query-driven mechanism to achieve an mAP50–95 of 0.682 on the wheat-ear dataset, outperforming the other comparison methods and illustrating the strong foundational capability of Transformer-based frameworks.

PodFormer achieves the best performance across all key metrics, attaining an mAP50 of 0.971 and an mAP50–95 of 0.706, corresponding to a 2.4% improvement over Mask2Former in mAP50–95. These results indicate that the AWDE, DGQI, and MFGR modules—originally designed for soybean field segmentation—exhibit strong task independence. Their capabilities in boundary enhancement, density modeling, and occlusion separation remain effective for wheat-ear instance segmentation, enabling PodFormer to achieve optimal cross-domain performance.

To visually illustrate the performance differences among models in the wheat-ear segmentation task, Figure 8 presents representative test samples along with the corresponding segmentation outputs of each method. The visual comparison reveals pronounced differences when handling occlusions and complex background textures. In regions obscured by leaves or containing complex background patterns (red dashed circles), YOLOv8-Seg and SegFormer exhibit noticeable false negatives. In regions affected by wheat-awn interference or densely clustered ears (yellow dashed circles), Mask R-CNN and YOLOv11-Seg frequently produce inaccurate boundaries or merge multiple instances. The baseline Mask2Former (cyan dashed circles) detects most wheat ears but still suffers from missed detections and boundary coalescence in high-density areas.

Figure 8.

Comparison of prediction results across models on the wheat-head instance-segmentation task. Red, yellow, and cyan dashed circles highlight representative errors produced by different models.

In contrast, PodFormer achieves the most accurate and consistent segmentation results across all challenging scenarios. By leveraging AWDE’s boundary enhancement capability, it effectively distinguishes wheat ears from leaves and soil backgrounds. Meanwhile, DGQI and MFGR further improve instance separation in dense and occluded regions, enabling PodFormer to generate the most complete masks with the clearest boundaries, closely aligning with ground-truth annotations.

In summary, PodFormer demonstrates clear performance advantages in cross-domain wheat-ear segmentation. These results not only validate its strong performance in soybean pod segmentation but also confirm that its core modules (AWDE, DGQI, and MFGR) possess strong generalizability and transferability. This architecture holds substantial practical value for addressing common challenges in agricultural vision tasks, including homogeneous backgrounds, uneven density, and severe occlusions.

4. Discussion

4.1. Effectiveness of the Proposed Modules

The integration of the AWDE, DGQI, and MFGR modules into the Mask2Former framework effectively addresses the primary challenges of mature soybean pod segmentation. AWDE amplifies high-frequency boundary cues while suppressing background-induced texture noise, enabling more accurate delineation of pods with weak contrast. DGQI incorporates multi-scale features and density priors into the query initialization process, thereby stabilizing instance detection across substantial scale variations and densely clustered regions. MFGR further refines mask predictions via confidence-guided feedback, enhancing instance separation under severe occlusion. Results from ablation and generalization experiments consistently validate the effectiveness of these modules. The improvements remain stable across controlled-background, real-world field, and cross-domain wheat-ear settings, highlighting the robustness and task-agnostic transferability of the proposed design.

4.2. Analysis of Model Performance

Compared with both CNN-based and Transformer-based baselines, PodFormer demonstrates significantly superior performance in accuracy, boundary preservation, and robustness to complex backgrounds. Quantitative metrics (Table 4) and qualitative visualizations (Figure 7 and Figure 8) show that the model produces more complete and consistent instance masks, reduces false merging in dense regions, and maintains stable performance under heterogeneous field textures.

A practical consideration concerns the use of high-resolution images (). While such high-resolution inputs preserve fine structural details essential for annotating mature pods, they inevitably increase memory consumption and computational cost. PodFormer maintains competitive inference speed despite this burden, indicating that the proposed modules enhance feature-level efficiency and reduce representational redundancy. These characteristics are particularly valuable for downstream deployment in precision agricultural machinery.

Importantly, real-field generalization results demonstrate that the model does not overfit to the artificial white-background acquisition setting used during training. Instead, it learns transferable structural and boundary cues that remain effective under natural field conditions. This validates the experimental strategy and confirms that controlled-background acquisition does not compromise—and may even enhance—real-world applicability.

4.3. Limitations and Future Work

Several limitations warrant further investigation. First, although the use of a white background board is effective for ensuring annotation consistency and mitigating extreme pod–background homogeneity, it inevitably introduces a degree of environmental control. Expanding the training dataset with a greater volume of natural-background field images will help narrow potential domain gaps and further enhance real-world robustness.

Second, although PodFormer achieves acceptable inference speed, the computational burden introduced by high-resolution inputs and the multi-branch decoding design may restrict real-time deployment on resource-constrained agricultural machinery. Future research will therefore explore lightweight variants of the proposed modules, model compression strategies, and hardware-efficient architectures to improve deployment feasibility.

Third, despite the improvements introduced by MFGR, scenarios involving extremely dense clusters or fully overlapped pods remain challenging. Incorporating richer structural priors—such as morphological constraints, hierarchical refinement, or topological instance reasoning—may further improve segmentation performance under such extreme occlusions.

Future research will focus on (1) developing lightweight architectures suitable for embedded agricultural devices; (2) expanding real-field training datasets without background boards; (3) exploring data-efficient and weakly supervised learning paradigms to reduce annotation costs; and (4) integrating PodFormer into intelligent harvesting systems for real-time phenotyping and autonomous control.

5. Conclusions

This paper addresses the challenge of instance segmentation for mature soybean pods under field conditions characterized by homogeneous backgrounds, scale and density inhomogeneity, and severe occlusion. We propose PodFormer, an enhanced architecture built upon Mask2Former, incorporating three key modules: Adaptive Wavelet Detail Enhancement (AWDE), Density-Guided Query Initialization (DGQI), and Mask Feedback Gated Refinement (MFGR). These modules respectively tackle weak boundaries, scale and density variations, and adhesion-induced occlusions, thereby substantially strengthening feature representation and instance separation.

On our self-built field-mature soybean dataset, PodFormer achieves state-of-the-art performance across multiple evaluation metrics, including mAP50 and mAP50–95. It also demonstrates strong robustness and generalization capability on real-world field images without background boards and on a cross-domain wheat-ear dataset, validating both the universality of the proposed modules and the effectiveness of the overall architecture.

Despite these improvements, the model still depends on white-background images during training and exhibits relatively high computational complexity. Future work will focus on model lightweighting and the development of more complex, background-free field datasets to enhance its end-to-end applicability in real agricultural environments.

Overall, PodFormer provides a robust, efficient, and generalizable solution for precise instance segmentation in complex agricultural scenarios, laying a solid foundation for intelligent soybean harvesting and agronomic trait extraction.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, L.C. and X.S.; methodology, L.C.; software, X.S.; validation, L.C. and X.S.; formal analysis, L.C.; investigation, L.C.; resources, L.C.; data curation, X.S.; writing—original draft preparation, L.C.; writing—review and editing, L.C. and X.S.; supervision, L.C.; project administration, L.C.; funding acquisition, L.C. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was funded by the Key Research and Development Project of Henan Province (241111110200), the Zhongyuan Science and Technology Innovation Leadership Talent Programme (254200510043), and the National Scientific and Technological Innovation Teams of Universities in Henan Province (25IRTSTHN018).

Institutional Review Board Statement

Not applicable.

Informed Consent Statement

Not applicable.

Data Availability Statement

The data presented in this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the editors and reviewers for their valuable comments and suggestions.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SAM | Segment Anything Model |

| AWDE | Adaptive Wavelet Detail Enhancement |

| DGQI | Density-Guided Query Initialization |

| MFGR | Mask Feedback Gated Refinement |

| SA | Shuffle Attention |

| DPB | Density Prediction Branch |

| GAP | Global average pooling |

| GQT | Gated-enhanced queries transformer decoder |

References

- Riera, L.G.; Carroll, M.E.; Zhang, Z.; Shook, J.M.; Ghosal, S.; Gao, T.; Singh, A.; Bhattacharya, S.; Ganapathysubramanian, B.; Singh, A.K.; et al. Deep multiview image fusion for soybean yield estimation in breeding applications. Plant Phenom. 2021, 2021, 9846470. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Uzal, L.C.; Grinblat, G.L.; Namías, R.; Larese, M.G.; Bianchi, J.S.; Morandi, E.N.; Granitto, P.M. Seed-per-pod estimation for plant breeding using deep learning. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2018, 150, 196–204. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Yan, Z.; Guo, Y.; Su, X.; Cao, Y.; Jiang, B.; Yang, F.; Zhang, Z.; Xin, D.; Chen, Q.; et al. SPM-IS: An auto-algorithm to acquire a mature soybean phenotype based on instance segmentation. Crop J. 2022, 10, 1412–1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yu, Z.; Wang, Y.; Ye, J.; Liufu, S.; Lu, D.; Zhu, X.; Yang, Z.; Tan, Q. Accurate and fast implementation of soybean pod counting and localization from high-resolution image. Front. Plant Sci. 2024, 15, 1320109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, S.; Zheng, L.; Wu, T.; Sun, S.; Zhang, M.; Li, M.; Wang, M. High-throughput soybean pods high-quality segmentation and seed-per-pod estimation for soybean plant breeding. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2024, 129, 107580. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, W.; Chen, Y.; Li, W.; Zhang, C.; Xiong, Y.; Zhan, W.; Huang, L.; Wang, J.; Qiu, L. SPP-extractor: Automatic phenotype extraction for densely grown soybean plants. Crop J. 2023, 11, 1569–1578. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wu, K.; Wang, T.; Rao, Y.; Jin, X.; Wang, X.; Li, J.; Zhang, Z.; Jiang, Z.; Shao, X.; Zhang, W. Practical framework for generative on-branch soybean pod detection in occlusion and class imbalance scenes. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2025, 139, 109613. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jia, X.; Hua, Z.; Shi, H.; Zhu, D.; Han, Z.; Wu, G.; Deng, L. A Soybean Pod Accuracy Detection and Counting Model Based on Improved YOLOv8. Agriculture 2025, 15, 617. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, F.; Wang, S.; Pang, S.; Han, Z.; Zhao, L. SmartPod: An Automated Framework for High-Precision Soybean Pod Counting in Field Phenotyping. Agronomy 2025, 15, 791. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, H.; Ma, X.; Guan, H.; Wang, F.; Shen, P. Recognition of soybean pods and yield prediction based on improved deep learning model. Front. Plant Sci. 2023, 13, 1096619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- He, J.; Weng, L.; Xu, X.; Chen, R.; Peng, B.; Li, N.; Xie, Z.; Sun, L.; Han, Q.; He, P.; et al. DEKR-SPrior: An efficient bottom-up keypoint detection model for accurate pod phenotyping in soybean. Plant Phenom. 2024, 6, 0198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, C.; Lu, Y.; Jiang, H.; Liu, S.; Ma, Y.; Zhao, T. Counting crowded soybean pods based on deformable attention recursive feature pyramid. Agronomy 2023, 13, 1507. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, K.; Li, J.; Shi, W.; Qi, L.; Yu, C.; Zhang, W. Field-based soybean flower and pod detection using an improved YOLOv8-VEW method. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1423. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, T.; Blok, P.M.; Burridge, J.; Kaga, A.; Guo, W. Multi-Scale Attention Network for Vertical Seed Distribution in Soybean Breeding Fields. Plant Phenom. 2024, 6, 0260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fu, X.; Li, A.; Meng, Z.; Yin, X.; Zhang, C.; Zhang, W.; Qi, L. A dynamic detection method for phenotyping pods in a soybean population based on an improved yolo-v5 network. Agronomy 2022, 12, 3209. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Magar, R.T.; Chen, D.; Lin, F.; Wang, D.; Yin, X.; Zhuang, W.; Li, Z. SoybeanNet: Transformer-based convolutional neural network for soybean pod counting from Unmanned Aerial Vehicle (UAV) images. Comput. Electron. Agric. 2024, 220, 108861. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, J.; Kaga, A.; Yamada, T.; Komatsu, K.; Hirata, K.; Kikuchi, A.; Hirafuji, M.; Ninomiya, S.; Guo, W. Improved field-based soybean seed counting and localization with feature level considered. Plant Phenom. 2023, 5, 0026. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhuang, Y.; Li, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, Z.; Zhao, J.; Li, D.; Gao, Y. SPCN: An Innovative Soybean Pod Counting Network Based on HDC Strategy and Attention Mechanism. Agriculture 2024, 14, 1347. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhou, S.; Sun, Q.; Zhang, N.; Chai, X.; Sun, T. PodNet: Pod Real-time Instance Segmentation in Pre-harvest Soybean Fields. Plant Phenom. 2025, 7, 100052. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, W. Advanced Auto Labeling Solution with Added Features. 2023. Available online: https://github.com/CVHub520/X-AnyLabeling (accessed on 27 August 2025).

- Kirillov, A.; Mintun, E.; Ravi, N.; Mao, H.; Rolland, C.; Gustafson, L.; Xiao, T.; Whitehead, S.; Berg, A.C.; Lo, W.Y.; et al. Segment anything. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision, Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023; pp. 4015–4026. [Google Scholar]

- Cheng, B.; Misra, I.; Schwing, A.G.; Kirillov, A.; Girdhar, R. Masked-attention mask transformer for universal image segmentation. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 1290–1299. [Google Scholar]

- He, K.; Zhang, X.; Ren, S.; Sun, J. Deep residual learning for image recognition. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 770–778. [Google Scholar]

- Xu, G.; Liao, W.; Zhang, X.; Li, C.; He, X.; Wu, X. Haar wavelet downsampling: A simple but effective downsampling module for semantic segmentation. Pattern Recognit. 2023, 143, 109819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.L.; Yang, Y.B. Sa-net: Shuffle attention for deep convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the ICASSP 2021-2021 IEEE International Conference on Acoustics, Speech and Signal Processing (ICASSP), Toronto, ON, Canada, 6–11 June 2021; pp. 2235–2239. [Google Scholar]

- Lin, C.W.; Lin, Y.; Zhou, S.; Zhu, L. Gateinst: Instance segmentation with multi-scale gated-enhanced queries in transformer decoder. Multimed. Syst. 2024, 30, 252. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Swathi, Y.; Challa, M. YOLOv8: Advancements and innovations in object detection. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Smart Computing and Communication, Bali, Indonesia, 25–27 July 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 1–13. [Google Scholar]

- Khanam, R.; Hussain, M. Yolov11: An overview of the key architectural enhancements. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2410.17725. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- He, K.; Gkioxari, G.; Dollár, P.; Girshick, R. Mask r-cnn. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 2961–2969. [Google Scholar]

- Xie, E.; Wang, W.; Yu, Z.; Anandkumar, A.; Alvarez, J.M.; Luo, P. SegFormer: Simple and efficient design for semantic segmentation with transformers. Adv. Neural Inf. Process. Syst. 2021, 34, 12077–12090. [Google Scholar]

- Wheat Heads. Wheat Heads Dataset. 2024. Available online: https://universe.roboflow.com/wheat-heads/wheat-heads-afhjy (accessed on 14 November 2025).

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.