A DeepWalk Graph Embedding-Enhanced Extreme Learning Machine Method for Online Gearbox Fault Diagnosis

Abstract

1. Introduction

2. Theoretical Background

2.1. K-Nearest Neighbor Graph Model

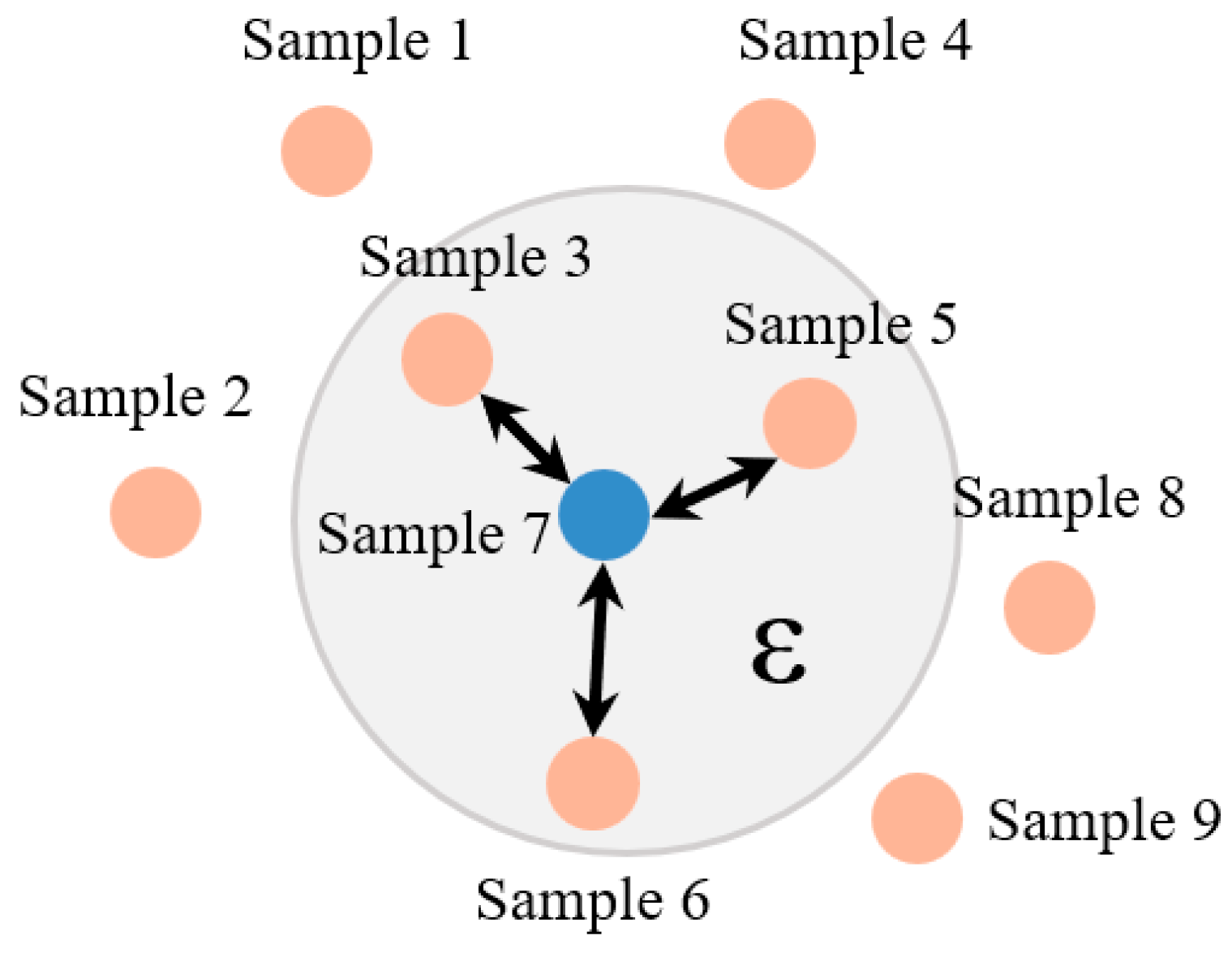

2.2. Radiation Graph

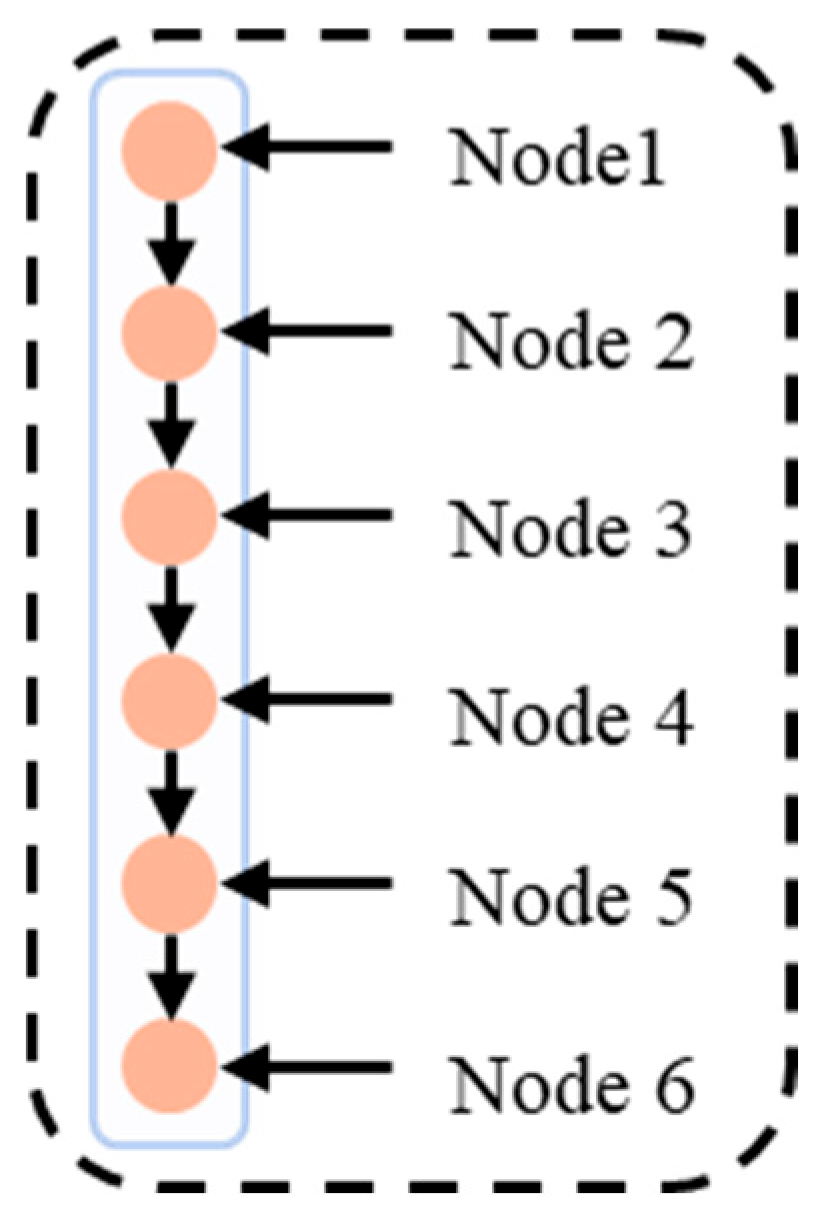

2.3. Path Graph

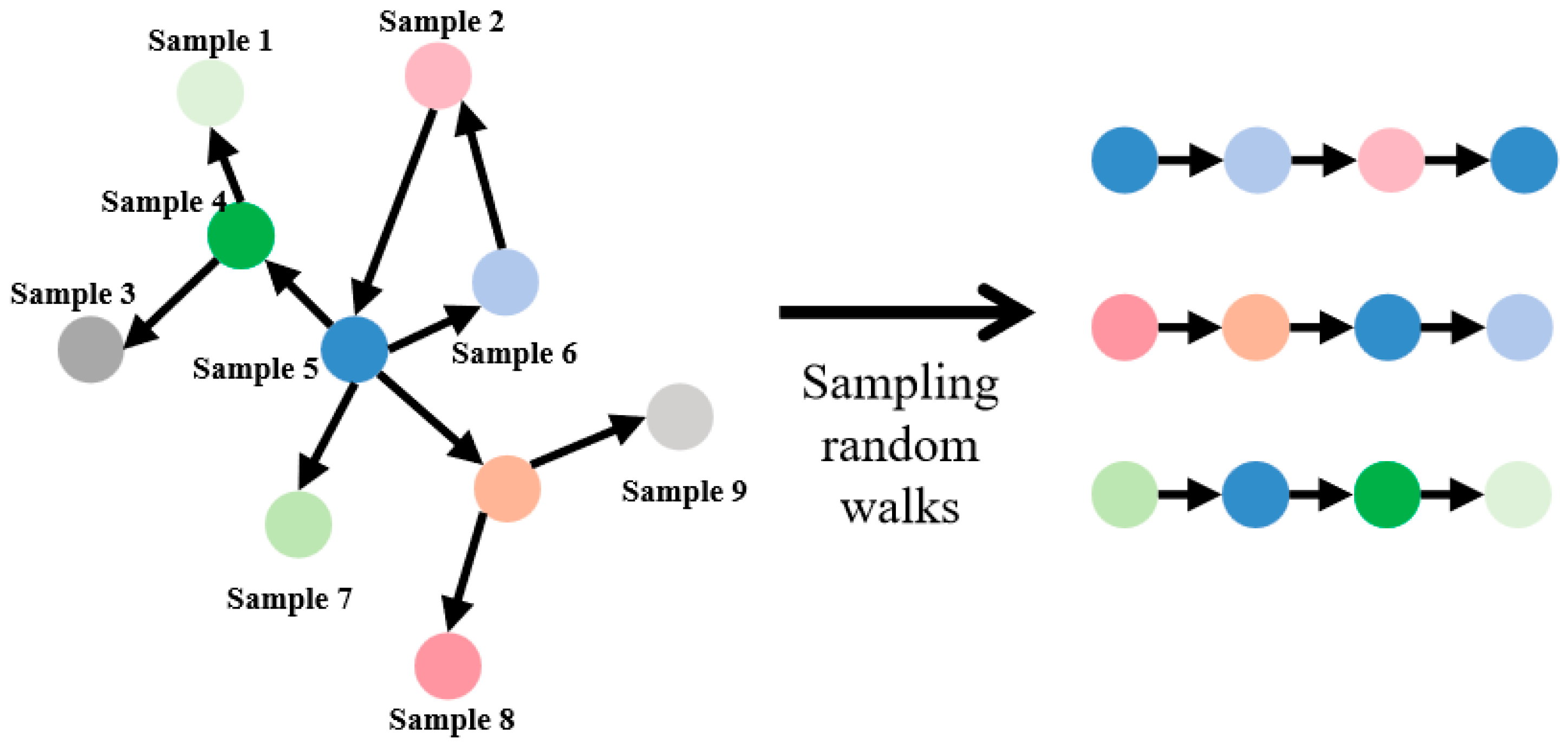

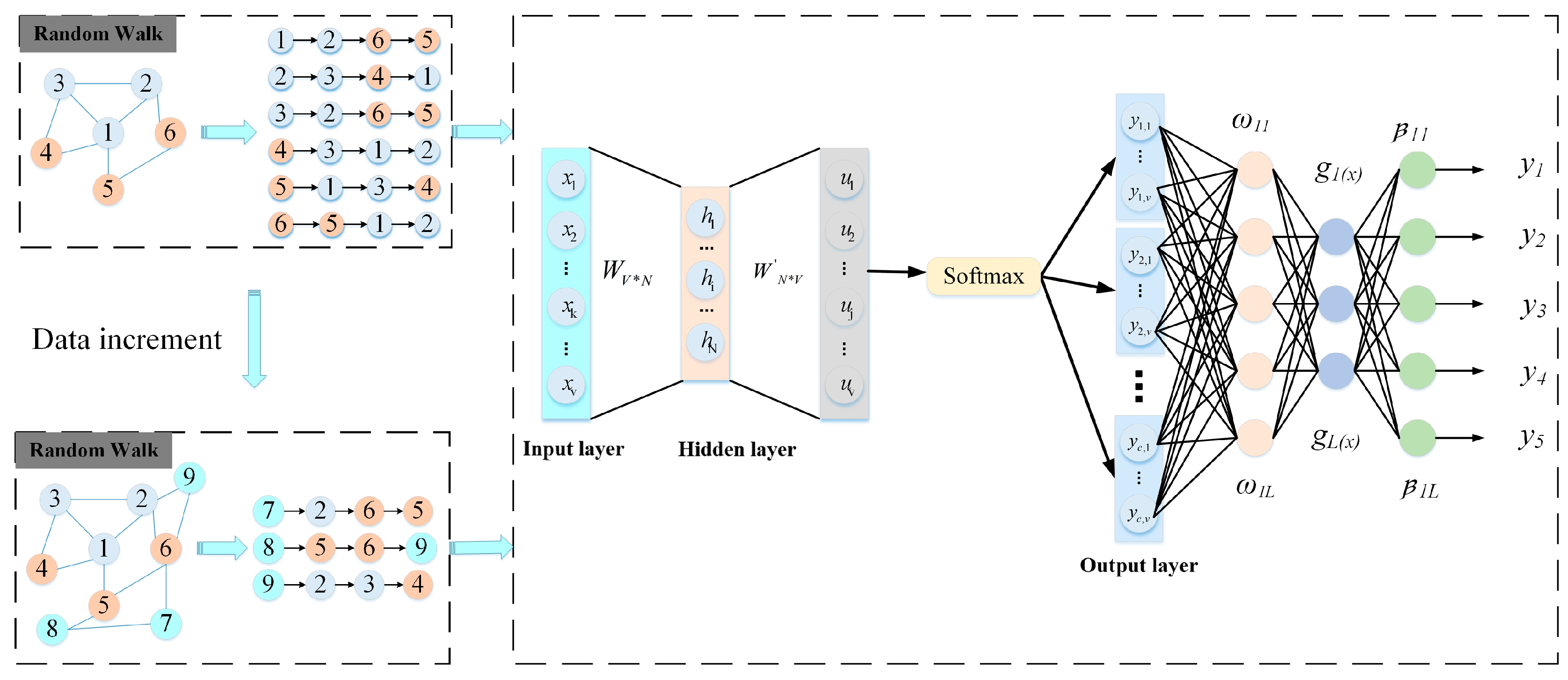

2.4. DeepWalk Algorithm

2.5. Extreme Learning Machine

3. Fault Recognition Method Based on DWELM

3.1. Method

3.2. Model Training Parameter Settings

4. Experiment and Analysis of Results

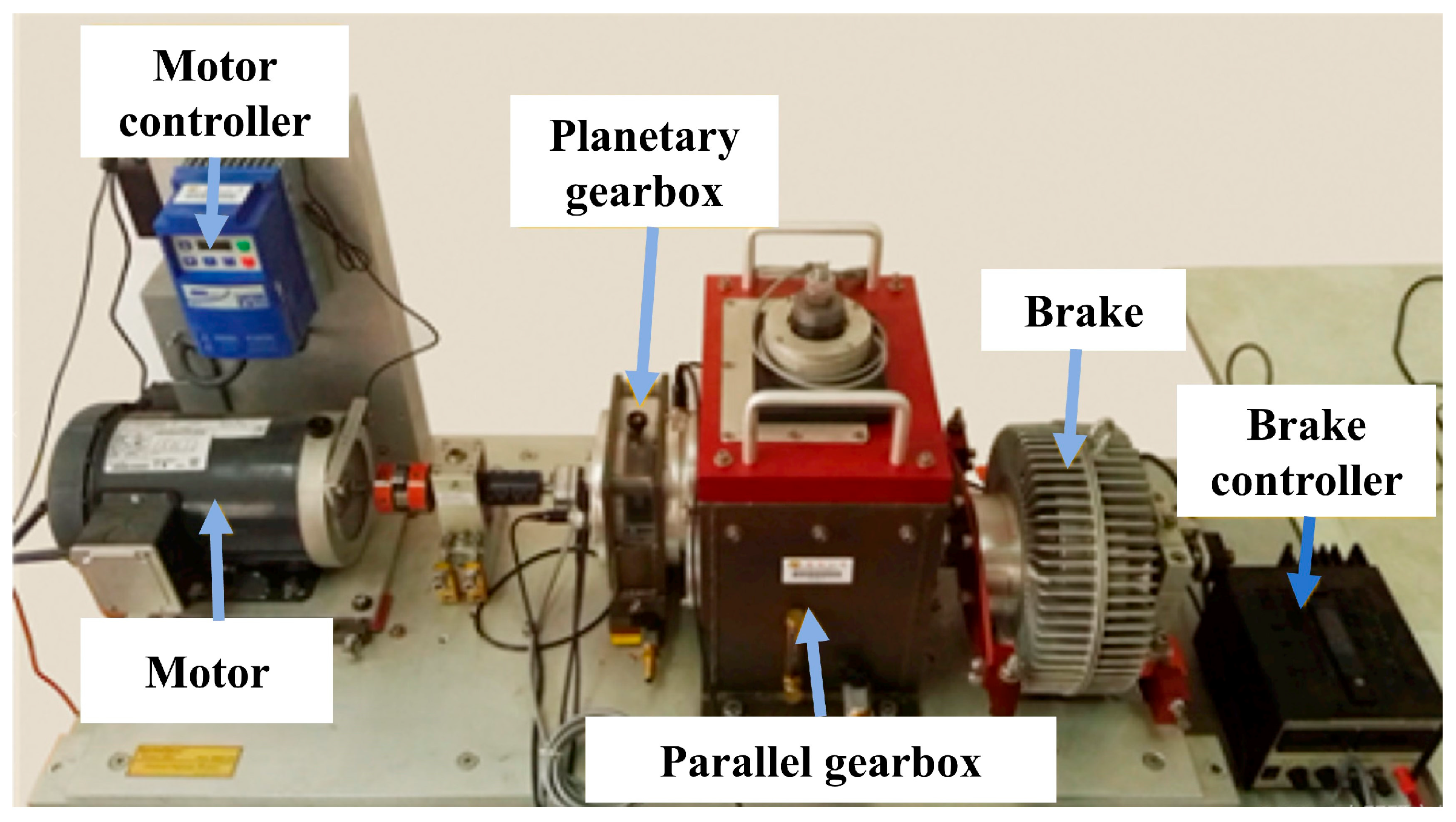

4.1. Description of Southeast University Gearbox Dataset

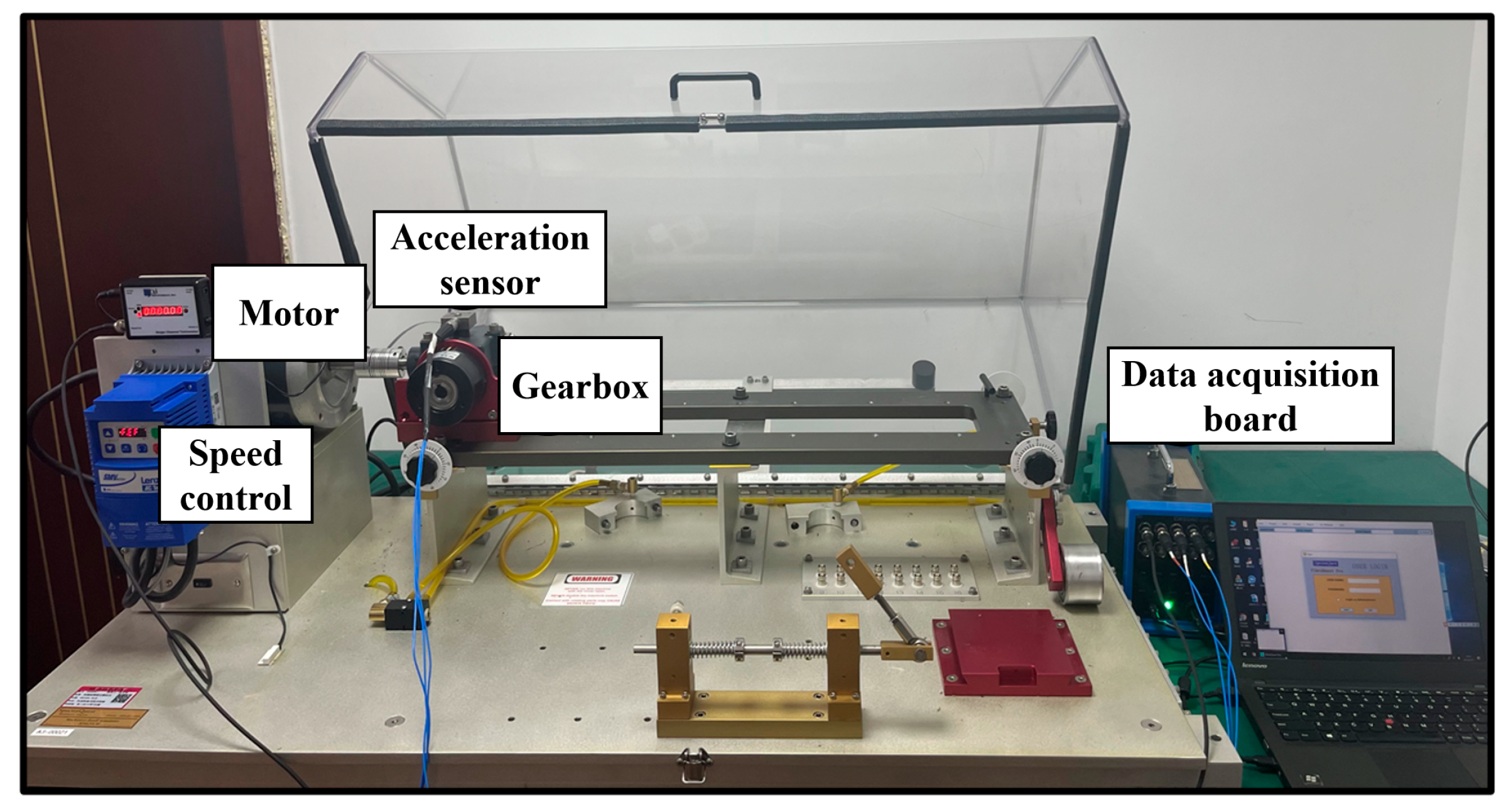

4.2. Description of HUST Gearbox Dataset

4.3. Experimental Sample Division

4.4. Results Analysis and Discussion

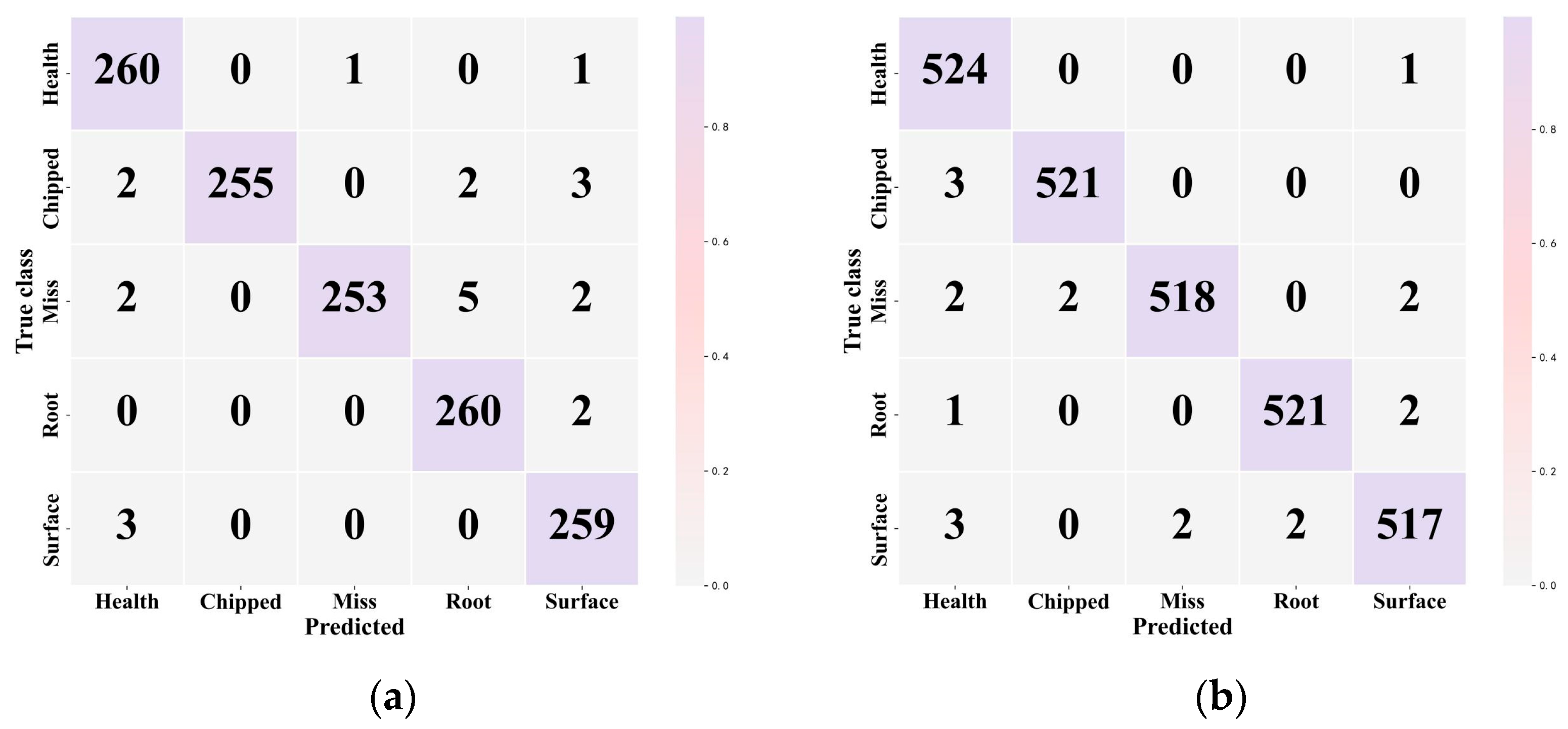

4.4.1. Southeast University Dataset Experimental Results and Analysis

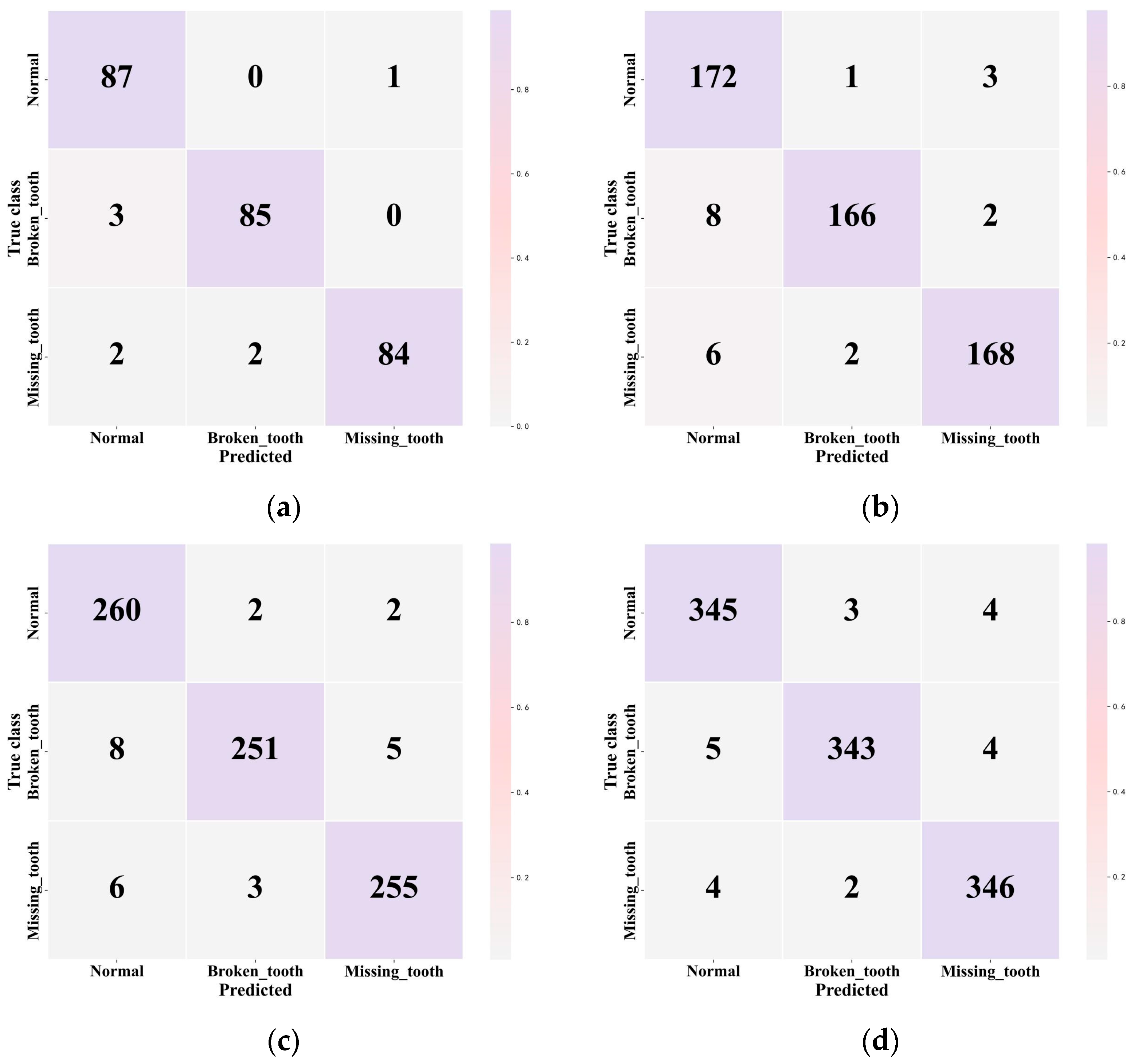

4.4.2. HUST Dataset Experimental Results and Analysis

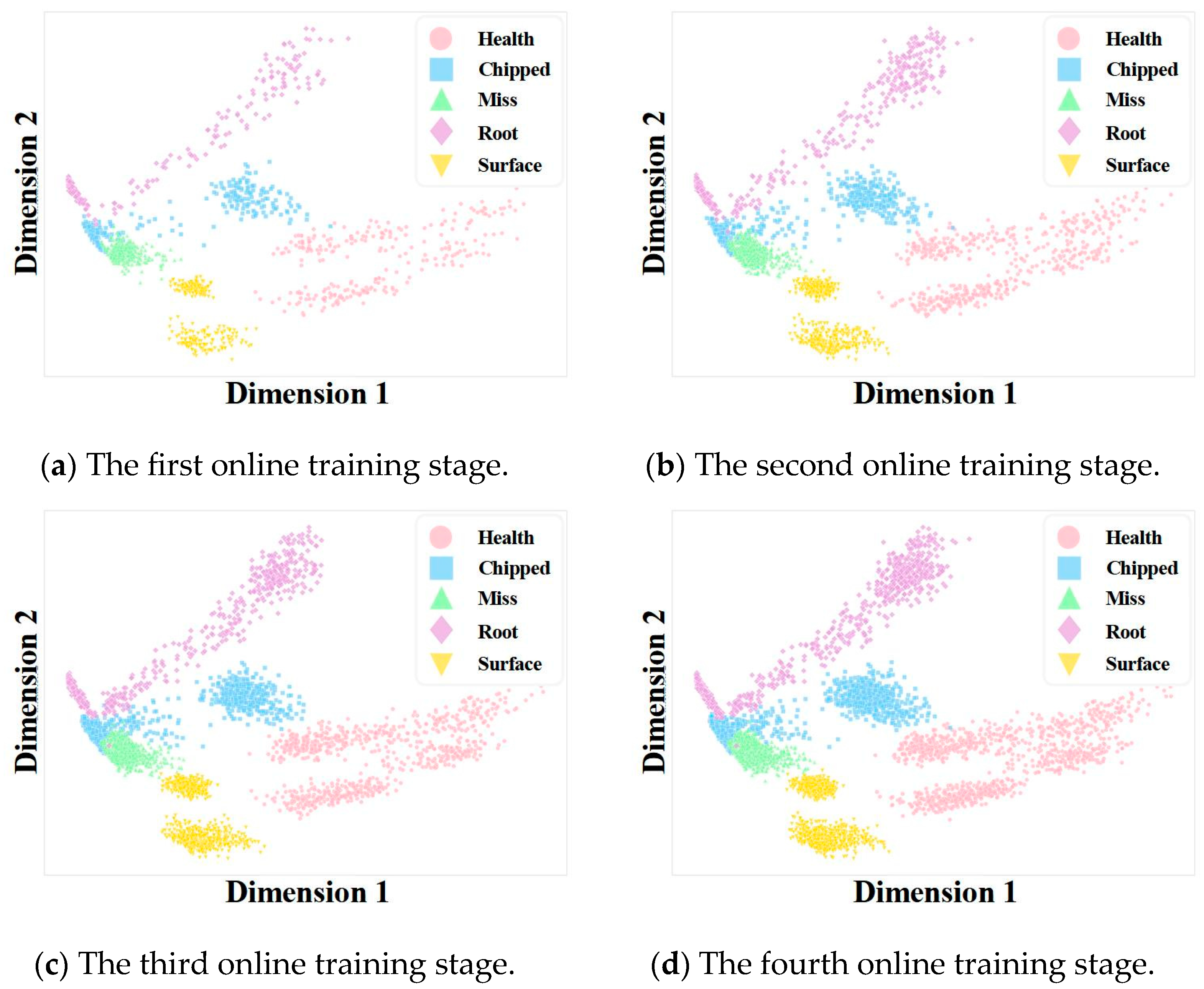

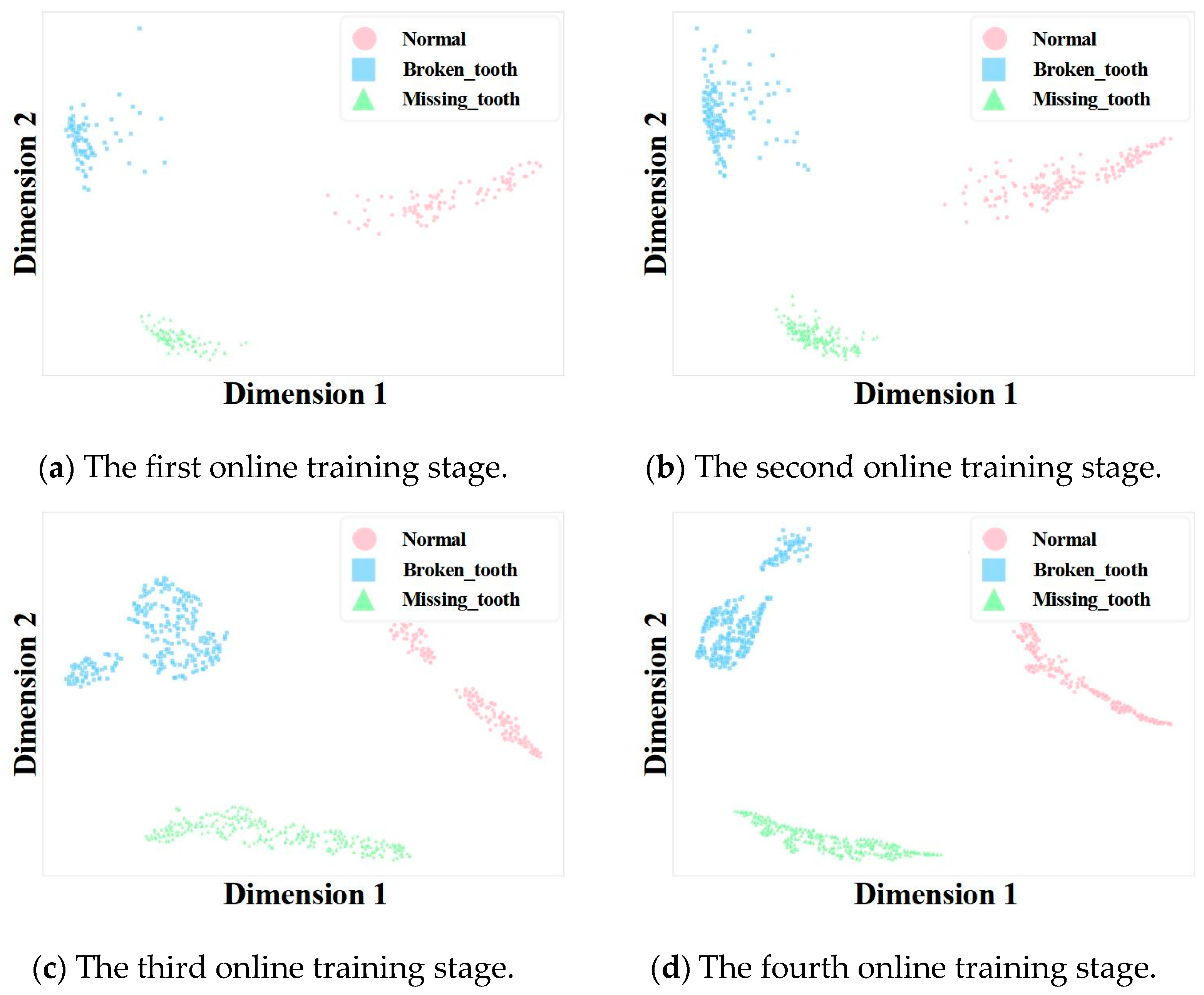

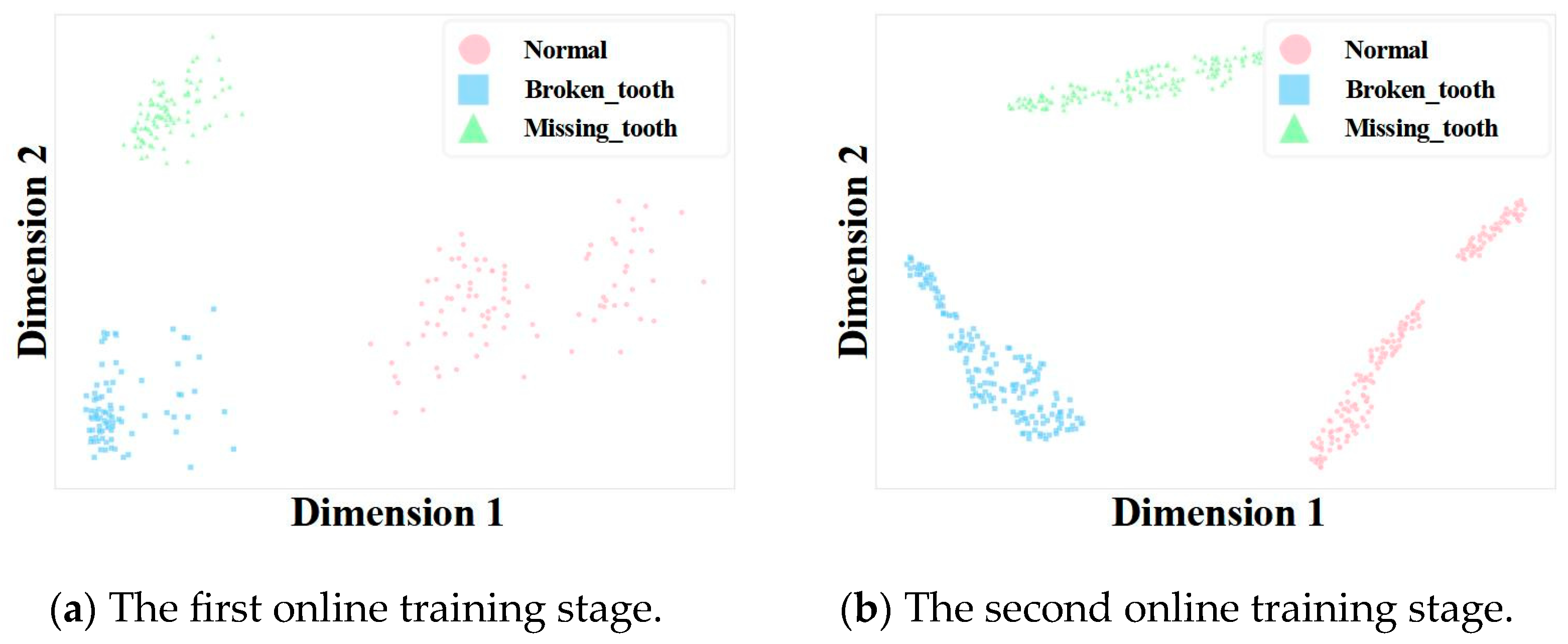

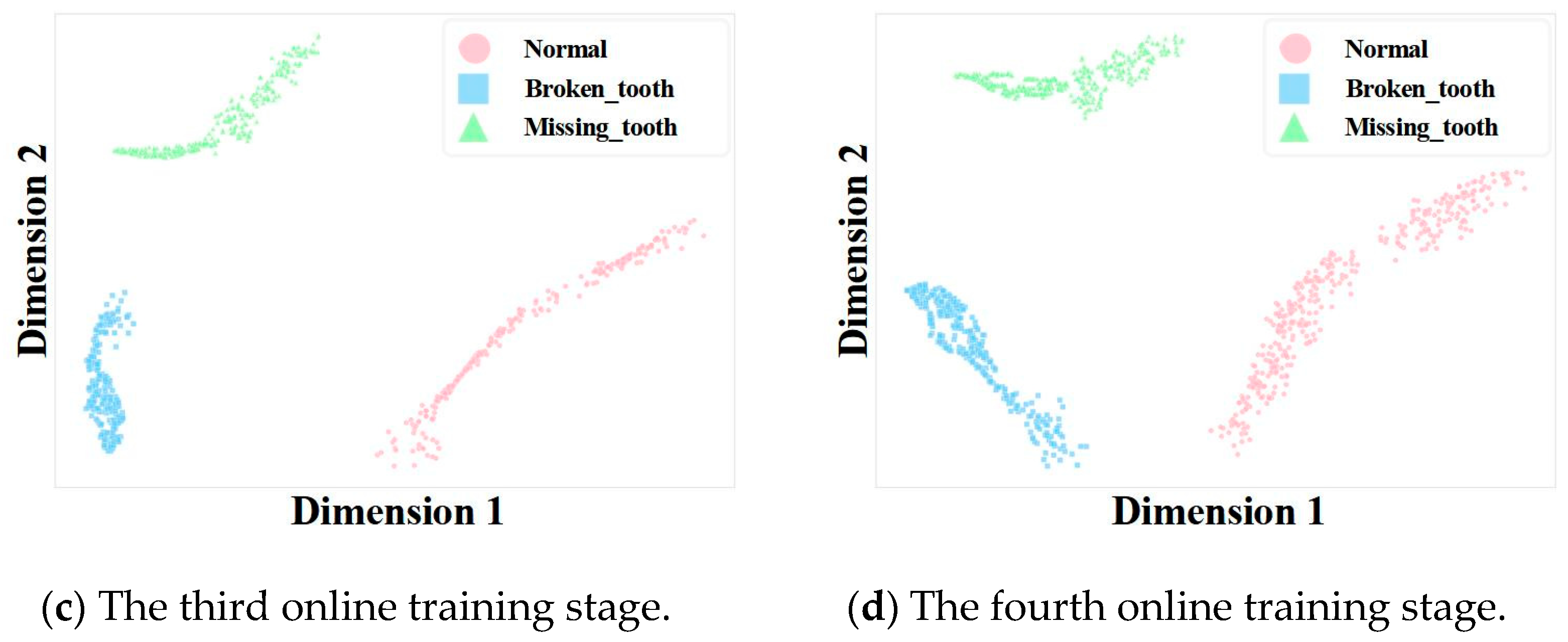

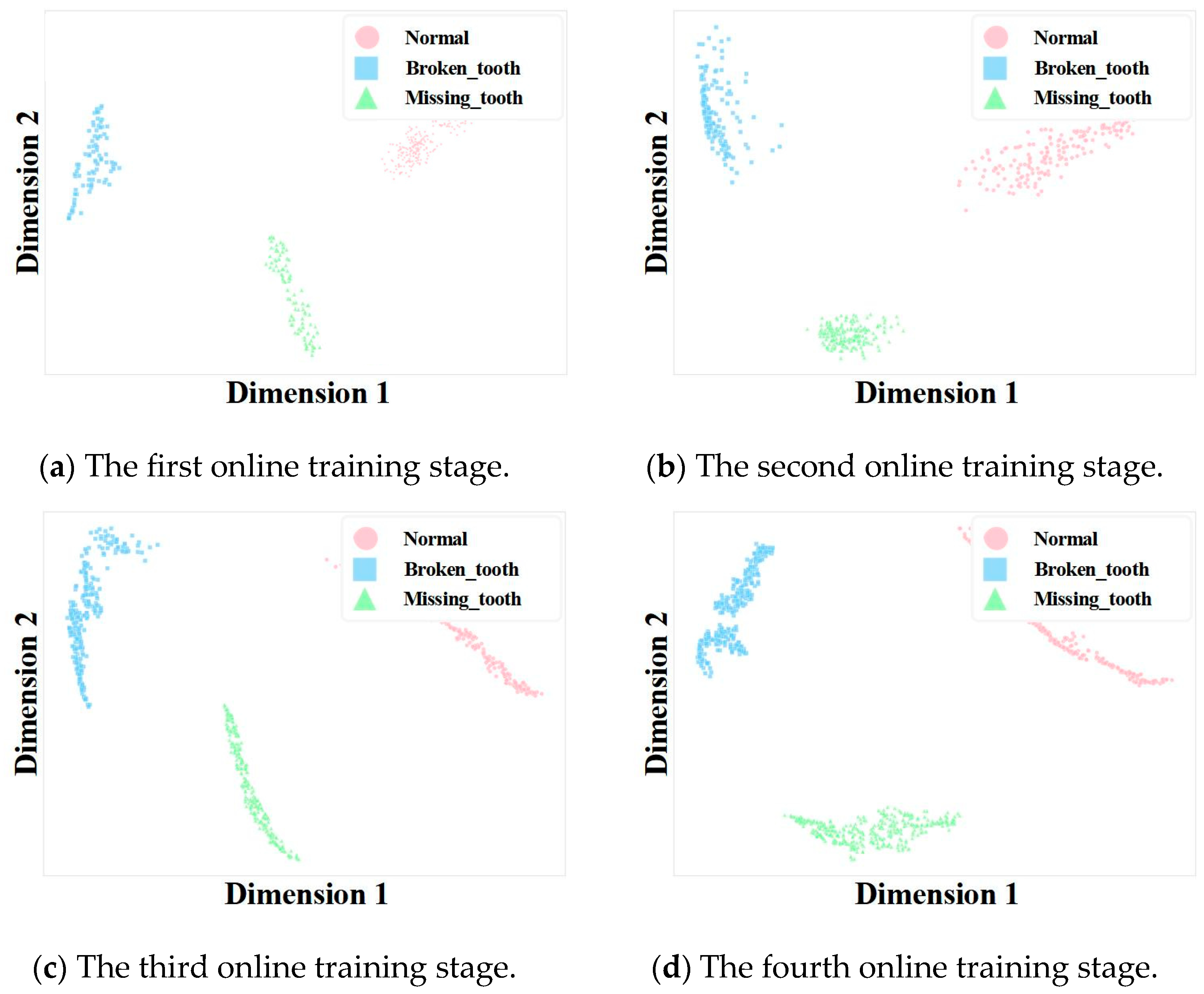

4.4.3. Visualization Analysis

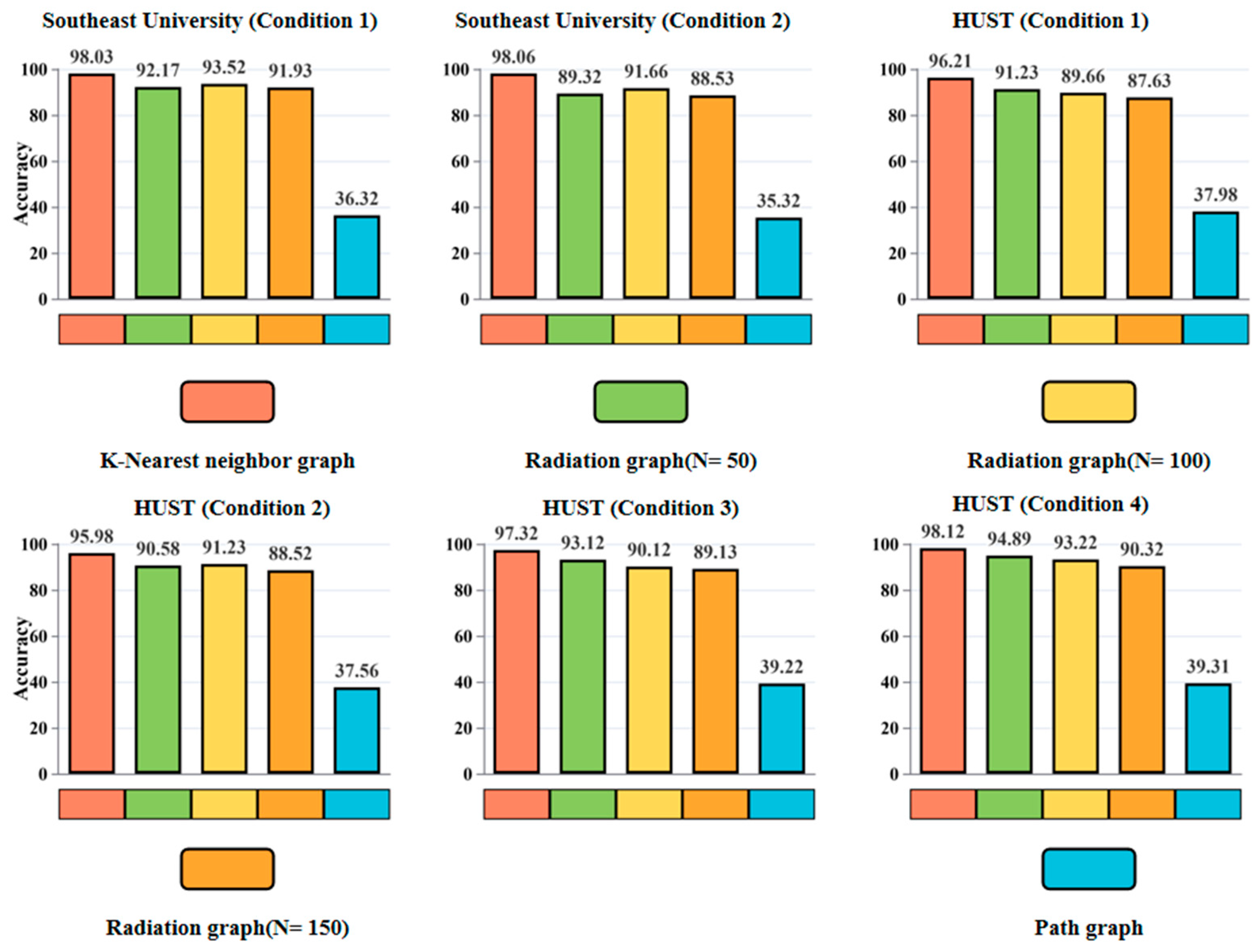

4.4.4. Graph Construction Analysis

4.4.5. Analysis of Classification Performance Metrics

- (1)

- Analysis for the Southeast University Dataset

- (2)

- Analysis for the HUST Dataset

5. Conclusions

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Conflicts of Interest

Abbreviations

| ELM | Extreme Learning Machine |

| DWELM | DeepWalk Graph Embedding-Enhanced Extreme Learning Machine |

| SLFN | Single-Hidden-Layer Feedforward Network |

| CNN | Convolutional Neural Network |

| RNN | Recurrent Neural Network |

| GNN | Graph Neural Network |

| LSTM | Long Short-Term Memory Network |

References

- Liu, R.; Yang, B.; Zio, E.; Chen, X. Artificial intelligence for fault diagnosis of rotating machinery: A review. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2018, 108, 33–47. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Meng, X.; Wang, Q.; Shi, C.; Zeng, Q.; Zhang, Y.; Zhang, W.; Wang, Y. Deep Ensemble Learning Based on Multi-Form Fusion in Gearbox Fault Recognition. Sensors 2025, 25, 4993. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiang, Z.; Han, Q.; Xu, X. Fault diagnosis of planetary gearbox based on motor current signal analysis. Shock Vib. 2020, 2020, 8854776. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mohd Amiruddin, A.A.A.; Zabiri, H.; Taqvi, S.A.A.; Tufa, L.D. Neural network applications in fault diagnosis and detection: An overview of implementations in engineering-related systems. Neural Comput. Appl. 2020, 32, 447–472. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, J.; Zhao, M.; Lin, J.; Liang, K. A comprehensive review on convolutional neural network in machine fault diagnosis. Neurocomputing 2020, 417, 36–63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Y.; Zhou, T.; Huang, X.; Cao, L.; Zhou, Q. Fault diagnosis of rotating machinery based on recurrent neural networks. Measurement 2021, 171, 108774. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, J.; Cao, X.; Chen, R.; Zhang, X.; Huang, X.; Qu, Y. Graph neural network architecture search for rotating machinery fault diagnosis based on reinforcement learning. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2023, 202, 110701. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Park, P.; Di Marco, P.; Shin, H.; Bang, J. Fault detection and diagnosis using combined autoencoder and long short-term memory network. Sensors 2019, 19, 4612. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Zhu, J.; Jiang, Q.; Shen, Y.; Qian, C.; Xu, F.; Zhu, Q. Application of recurrent neural network to mechanical fault diagnosis: A review. J. Mech. Sci. Technol. 2022, 36, 527–542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hou, J.; Lu, X.; Zhong, Y.; He, W.; Zhao, D.; Zhou, F. A comprehensive review of mechanical fault diagnosis methods based on convolutional neural network. J. Vibroeng. 2024, 26, 44–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jiao, C.; Zhang, D.; Fang, X.; Miao, Q. Ensemble of simplified graph wavelet neural networks for planetary gearbox fault diagnosis. IEEE Trans. Instrum. Meas. 2023, 72, 3529910. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Wu, J.; Yu, Z.; Hu, J.; Zhou, Q. A structurally re-parameterized convolution neural network-based method for gearbox fault diagnosis in edge computing scenarios. Eng. Appl. Artif. Intell. 2023, 126, 107091. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, H.; Liu, Z.; Li, M.; Dai, X.; Wang, R.; Shi, L. A gearbox fault diagnosis method based on graph neural networks and Markov transform fields. IEEE Sens. J. 2024, 24, 25186–25196. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.; Li, Y.; Wang, K.; Zuo, M.J. An automatic speed adaption neural network model for planetary gearbox fault diagnosis. Measurement 2021, 171, 108784. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lei, Y.; Yang, B.; Jiang, X.; Jia, F.; Li, N.; Nandi, A.K. Applications of machine learning to machine fault diagnosis: A review and roadmap. Mech. Syst. Signal Process. 2020, 138, 106587. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, W.; Peng, G.; Li, C.; Chen, Y.; Zhang, Z. A new deep learning model for fault diagnosis with good anti-noise and domain adaptation ability on raw vibration signals. Sensors 2017, 17, 425. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Zhang, W.; Ding, Q. Cross-domain fault diagnosis of rolling element bearings using deep generative neural networks. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2018, 66, 5525–5534. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, A.; Li, S.; Cui, Y.; Yang, W.; Dong, R.; Hu, J. Limited data rolling bearing fault diagnosis with few-shot learning. IEEE Access 2019, 7, 110895–110904. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sehri, M.; Varejão, I.; Hua, Z.; Bonella, V.; Santos, A.; Boldt, F.D.A.; Dumond, P.; Varejão, F.M. Towards a Universal Vibration Analysis Dataset: A Framework for Transfer Learning in Predictive Maintenance and Structural Health Monitoring. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2504.11581. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zachariades, C.; Xavier, V. A Review of Artificial Intelligence Techniques in Fault Diagnosis of Electric Machines. Sensors 2025, 25, 5128. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Lei, Y.; Lin, J.; Zuo, M.J.; He, Z. Condition monitoring and fault diagnosis of planetary gearboxes: A review. Measurement 2014, 48, 292–305. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xu, X.; Huang, X.; Bian, H.; Wu, J.; Liang, C.; Cong, F. Total process of fault diagnosis for wind turbine gearbox, from the perspective of combination with feature extraction and machine learning: A review. Energy AI 2024, 15, 100318. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, R.; Wang, S.; Zhu, F.; Huang, J. Adaptive graph convolutional neural networks. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New Orleans, LA, USA, 2–7 February 2018; Volume 32. [Google Scholar]

- Perozzi, B.; Al-Rfou, R.; Skiena, S. Deepwalk: Online learning of social representations. In Proceedings of the 20th ACM SIGKDD International Conference on Knowledge Discovery and Data Mining, New York, NY, USA, 24–27 August 2014; pp. 701–710. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Jin, M.; Pan, S.; Zhou, C.; Zheng, Y.; Xia, F.; Yu, P. Graph self-supervised learning: A survey. IEEE Trans. Knowl. Data Eng. 2022, 35, 5879–5900. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Liu, X.; Zhang, Z.; Meng, F.; Zhang, Y. Fault diagnosis of wind turbine bearings based on CNN and SSA–ELM. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 2023, 11, 3929–3945. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afia, A.; Gougam, F.; Rahmoune, C.; Touzout, W.; Ouelmokhtar, H.; Benazzouz, D. Gearbox fault diagnosis using remd, eo and machine learning classifiers. J. Vib. Eng. Technol. 2024, 12, 4673–4697. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Maaten, L.; Hinton, G. Visualizing data using t-SNE. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2008, 9, 2579–2605. [Google Scholar]

- Khoshraftar, S.; An, A. A survey on graph representation learning methods. ACM Trans. Intell. Syst. Technol. 2024, 15, 1–55. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xia, F.; Sun, K.; Yu, S.; Aziz, A.; Wan, L.; Pan, S.; Liu, H. Graph learning: A survey. IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 2021, 2, 109–127. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Zhang, H.; Lu, G. Graph entropy-based early change detection in dynamical bearing degradation process. IEEE Internet Things J. 2024, 11, 23186–23195. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, Z.; Li, K.; Lu, G. Local mean decomposition enhanced graph spectrum analysis for condition monitoring of rolling element bearings. Meas. Sci. Technol. 2025, 36, 026121. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, K.; Wang, M.J.; Yuan, M.J.; Zhang, H.S.; Yuan, K.Y.; Lu, G.L. Early fault detection for rolling bearings based on one-dimensional structure graph entropy. China Mech. Eng. 2025, 36, 1–13. (In Chinese) [Google Scholar]

- Jeyaraj, R.; Balasubramaniam, T.; Balasubramaniam, A.; Paul, A. DeepWalk with Reinforcement Learning (DWRL) for node embedding. Expert Syst. Appl. 2024, 243, 122819. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, Y.; Cui, L.; Zhang, Y. Improving skip-gram embeddings using BERT. IEEE/ACM Trans. Audio Speech Lang. Process. 2021, 29, 1318–1328. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wang, J.; Lu, S.; Wang, S.H.; Zhang, Y.D. A review on extreme learning machine. Multimed. Tools Appl. 2022, 81, 41611–41660. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shao, S.; McAleer, S.; Yan, R.; Baldi, P. Highly accurate machine fault diagnosis using deep transfer learning. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inform. 2018, 15, 2446–2455. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhao, C.; Zio, E.; Shen, W. Domain generalization for cross-domain fault diagnosis: An application-oriented perspective and a benchmark study. Reliab. Eng. Syst. Saf. 2024, 245, 109964. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kia, S.H.; Henao, H.; Capolino, G.A. A high-resolution frequency estimation method for three-phase induction machine fault detection. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2007, 54, 2305–2314. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

| Algorithm Name | |

|---|---|

| Input: | Graph data:

Window Size: Embedding Size: Steps: Walk Length per vertex: |

| Output: | Node embedding matrix: 1. Initialize: Sample 2. Build a binary tree from V 3. to do 4. 5. do 6. 7. 8. end for 9. end for |

| Algorithm Name | |

|---|---|

| Output: | 1. for each do 2. for each do 3. 4. 5. end for 6. end for |

| Parameter | Value | Parameter Description |

|---|---|---|

| Number of random walk sequences | 30 | The number of random walk paths that started from each node, affecting the coverage and sampling sufficiency of node sequences. |

| Maximum length of random walk sequences | 15 | The maximum number of steps in each random walk path, controlling the trade-off between local and global structural information. |

| Sliding window size | 15 | The context window size used in the Skip-Gram model, influencing the model’s ability to capture local node relationships. |

| Node embedding dimension | 128 | The length of the node embedding vector, determining the dimensionality and expressive power of the feature representation. |

| ELM hidden layer number | 400 | The number of neurons in the hidden layer of the extreme learning machine, affecting the model’s nonlinear fitting capability and classification performance. |

| Fault Status | Condition 1 | Condition 2 |

|---|---|---|

| Health | 1200 rpm and 0 Nm | 1800 rpm and 7.32 Nm |

| Chipped | ||

| Miss | ||

| Root | ||

| Surface |

| Fault Status 1 | Fault Status 2 | Load | Rotate Speed |

|---|---|---|---|

| Broken tooth | Missing tooth | 0.113 Nm 0.226 Nm 0.339 Nm 0.452 Nm | 1500 rpm 1800 rpm 2100 rpm 2400 rpm |

| Dataset | Fault Status | Label | Number of Samples | Total |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Southeast University | Health | 0 | 1048 | 5240 |

| Chipped | 1 | 1048 | ||

| Miss | 2 | 1048 | ||

| Root | 3 | 1048 | ||

| Surface | 4 | 1048 | ||

| HUST | Normal | 0 | 262 | 786 |

| Broken_tooth | 1 | 262 | ||

| Missing_tooth | 2 | 262 |

| Fault State | Condition 1 (%) | Condition 1–2 (%) | Condition 1–3 (%) | Condition 1–4 (%) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Precision/Recall/F1 | Precision/Recall/F1 | Precision/Recall/F1 | Precision/Recall/F1 | |

| Health | 99.2/99.5/99.3 | 98.8/99.1/99.0 | 99.0/99.3/99.1 | 99.2/99.4/99.3 |

| Broken_tooth | 95.1/94.3/94.7 | 93.8/92.5/93.1 | 96.2/95.8/96.0 | 97.5/97.0/97.2 |

| Missing_tooth | 94.8/95.2/95.0 | 92.5/91.8/92.1 | 95.8/96.1/95.9 | 96.8/97.2/97.0 |

| Root crack | 96.2/95.8/96.0 | 94.9/95.2/95.0 | 97.1/96.8/96.9 | 98.0/97.6/97.8 |

| Surface wear | 95.5/96.0/95.7 | 94.1/94.5/94.3 | 96.5/96.9/96.7 | 97.8/98.1/97.9 |

| Fault State | Condition 1 (%) | Condition 1–2 (%) |

|---|---|---|

| Precision/Recall/F1 | Precision/Recall/F1 | |

| Normal | 99.5/99.2/99.4 | 99.6/99.3/99.4 |

| Broken_tooth | 97.8/97.5/97.6 | 98.0/97.8/97.9 |

| Missing_tooth | 97.5/97.9/97.7 | 97.7/98.1/97.9 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Wei, C.; Xu, T.; Yu, G.; Li, B.; Zhang, X. A DeepWalk Graph Embedding-Enhanced Extreme Learning Machine Method for Online Gearbox Fault Diagnosis. Electronics 2026, 15, 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010079

Wei C, Xu T, Yu G, Li B, Zhang X. A DeepWalk Graph Embedding-Enhanced Extreme Learning Machine Method for Online Gearbox Fault Diagnosis. Electronics. 2026; 15(1):79. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010079

Chicago/Turabian StyleWei, Chenglong, Tongming Xu, Gang Yu, Bozhao Li, and Xu Zhang. 2026. "A DeepWalk Graph Embedding-Enhanced Extreme Learning Machine Method for Online Gearbox Fault Diagnosis" Electronics 15, no. 1: 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010079

APA StyleWei, C., Xu, T., Yu, G., Li, B., & Zhang, X. (2026). A DeepWalk Graph Embedding-Enhanced Extreme Learning Machine Method for Online Gearbox Fault Diagnosis. Electronics, 15(1), 79. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010079