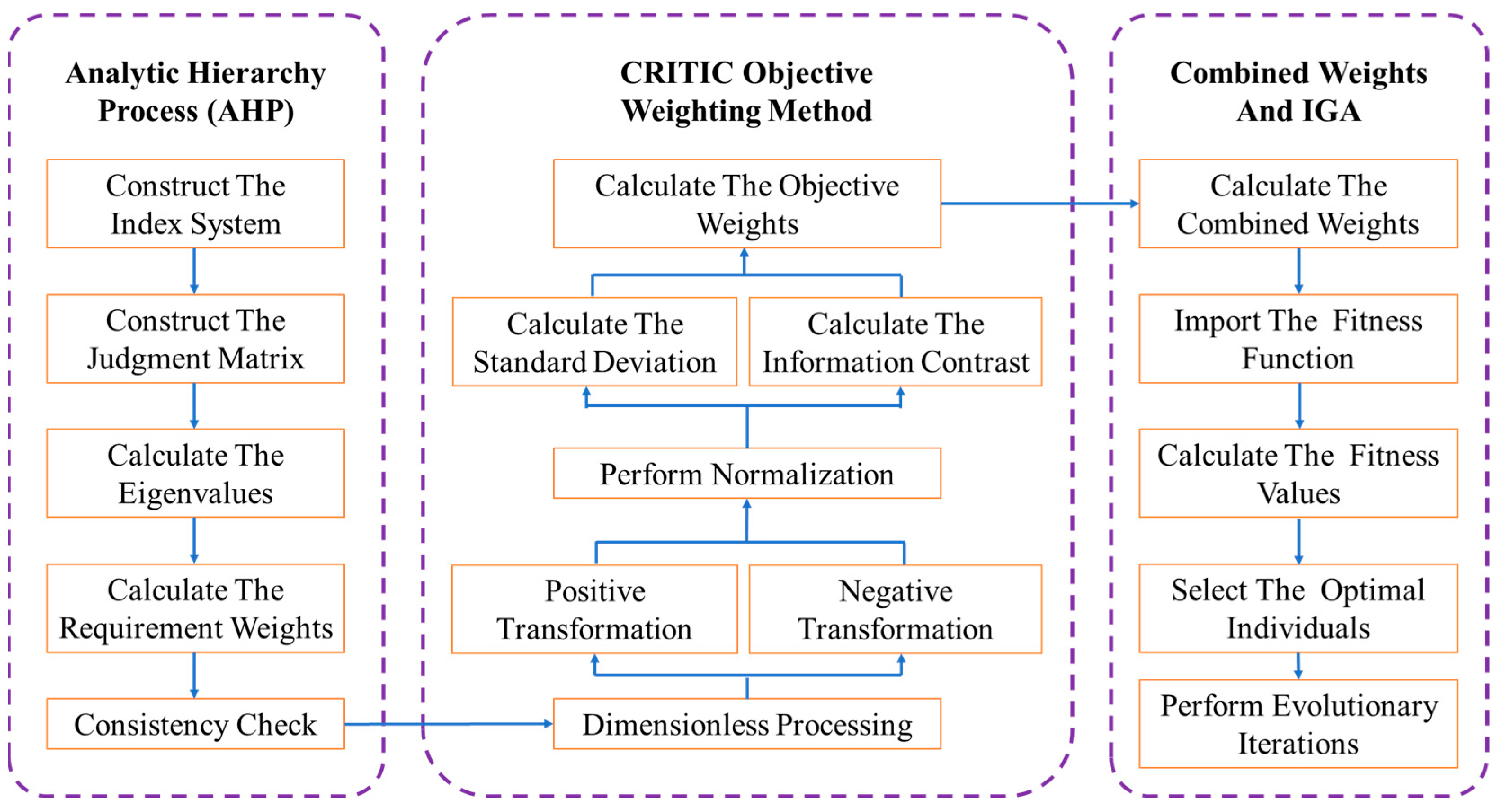

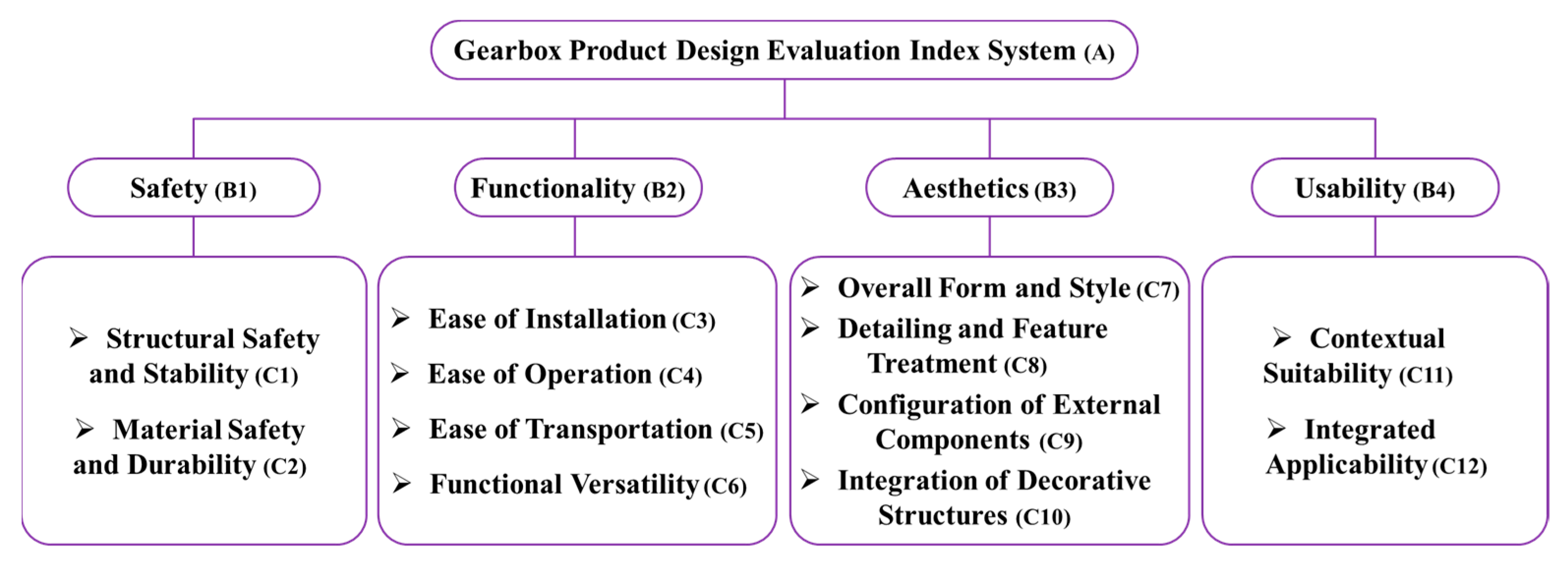

4.3.2. AHP-Based Requirement Weight Calculation

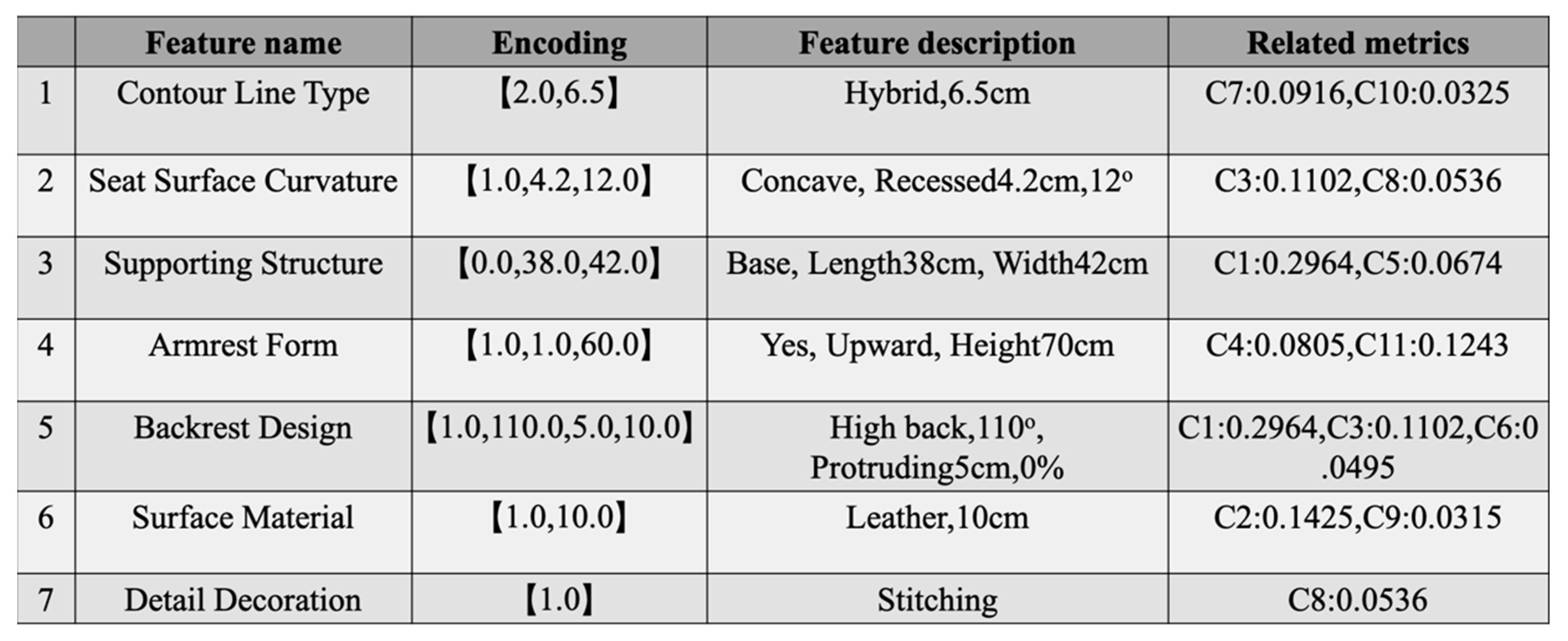

Based on the evaluation index system for the armchair product, the indicator layer comprises 12 criteria, resulting in a judgment matrix of order

n = 12 in the AHP framework. The 1–9 scale method was applied for pairwise comparisons according to the established scoring system. The numerical meanings of the 1–9 scale are presented in

Table 1, while the importance level scale for the judgment matrix indicators is shown in

Table 2.

Table 1 shows the random consistency index (RI) values corresponding to the Saaty 1–9 scale method, which will be used for subsequent consistency testing (Formula (3)). The magnitude of the RI value is related to the order

n of the judgment matrix.

Table 2 defines the scale values and their semantics used to construct the AHP judgment matrix, providing a unified quantitative basis for pairwise comparisons among users in this study.

The calculated AHP weight data are provided in

Table 3,

Table 4,

Table 5,

Table 6,

Table 7 and

Table 8.

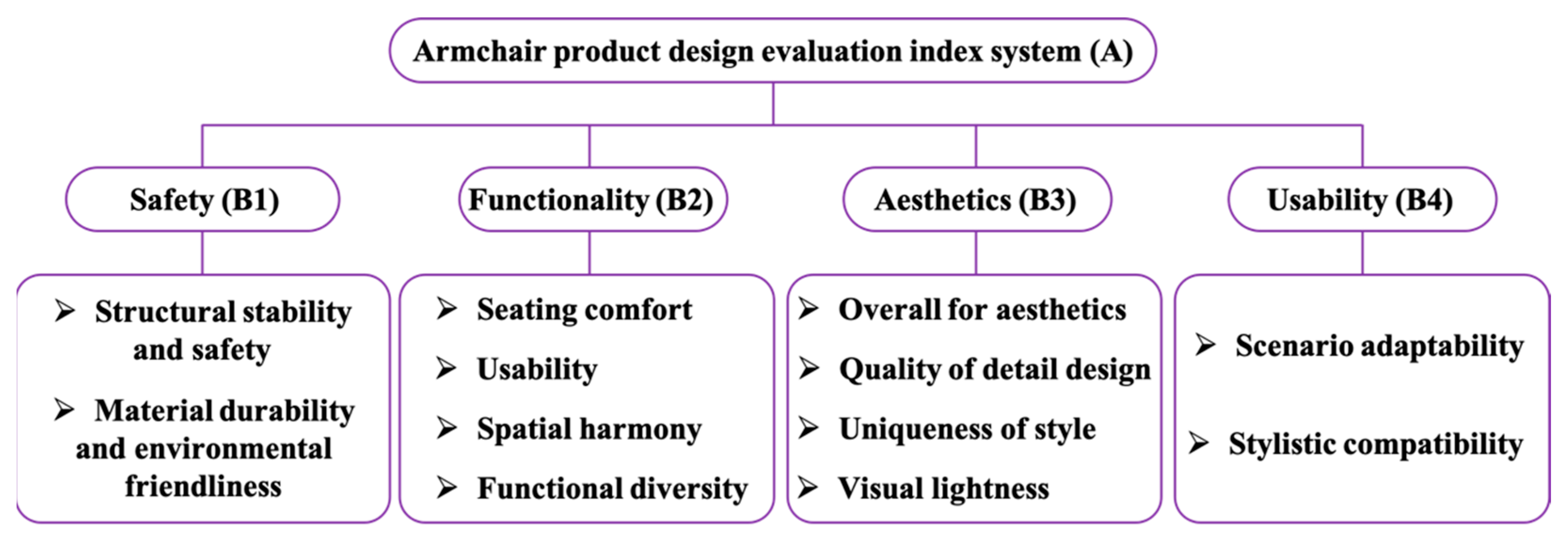

Table 3 presents the pairwise comparison judgment matrix and calculated weights for four criteria (B

1 safety, B

2 functionality, B

3 aesthetics, B

4 usability) under the target layer (A: armchair product design evaluation index system). The weight results show that users consider “aesthetics (B

3, weight 0.466)” and “functionality (B

2, weight 0.320)” to be the two most critical aspects in armchair design, while the relative importance of “usability (B

4, weight 0.057)” is relatively low.

Table 4 shows the judgment matrices of two sub-criteria under the “safety (B

1)” criterion. Users consider “structural stability and safety (C

1)” to be significantly more important than “material durability and environmental protection (C

2)” (scale 3:1), with weights of 0.75 and 0.25, respectively.

Table 5 shows the judgment matrix for the “Functional (B

2)” criterion. Among them, “sitting comfort (C

3)” has the highest weight (0.465) and is considered a core functional attribute; The weight of “functional diversity (C

6)” is the lowest (0.097).

Table 6 shows that under the criterion of “Aesthetics (B

3)”, “Overall Aesthetics (C

7)” is considered the most important sub-criterion (weight 0.456), followed by “Detail Design Quality (C

8, weight 0.293)”.

Table 7 shows the judgment matrix of the “usability (B

4)” criterion, indicating that users value “scene adaptability (C

11, weight 0.667)” more than “style compatibility (C

12, weight 0.333)”.

Table 8 summarizes the final weights and rankings of all secondary and tertiary criteria. From the overall ranking of the three-level criteria, “sitting comfort (C

3)”, “structural stability and safety (C

1)”, and “overall aesthetics (C

7)” rank among the top three, which is consistent with the core demands of furniture design that focus on comfort, safety, and aesthetics. This weight system provides subjective weight vectors for subsequent mixed weighting.

To ensure data consistency during the construction of the evaluation matrix and to validate the effectiveness of the weights within the original indicator matrix

B, a consistency check must be conducted for the indicator weights in the judgment matrix. Each element of the matrix is normalized to obtain the average weight values

ωi, the weight vector, and the maximum eigenvalue of the judgment matrix

λmax. Consistency verification is then performed using these results, where the consistency index (

CI) and the consistency ratio (

CR) are computed accordingly.

Among them,

λmax is the maximum eigenvalue of the judgment matrix,

B is the judgment matrix,

W is the weight vector, and

ωi is the

i-th component of the weight vector.

n is the order of the matrix (i.e., the number of comparison indicators).

CI is the consistency index, used to measure the degree to which a judgment matrix deviates from consistency. The closer the

CI value is to 0, the better the consistency.

RI is the random index, the value of which is related to

n.

CR is the consistency ratio.

RI denotes the random consistency index, with its corresponding values listed in

Table 9. When

CR < 0.1, the judgment matrix is considered to have passed the consistency test. The consistency test results are shown in

Table 9, indicating that all

CR values in the armchair product evaluation model are below 0.1, thus meeting the consistency requirement.

The scoring data provided by the three experts during the construction of the AHP evaluation hierarchy for the 12 indicators are presented in

Table 10. The averaged values were then incorporated into the objective weighting formula to calculate the variability, conflict intensity, information content, and objective weights of the evaluation indicators. The evaluation process considers

Y assessment objects, each characterized by H evaluation indicators.

Since the original indicator matrix contains negative-oriented indicators, nondimensionalization is required. After this transformation, b denotes the normalized indicator value.

In the formula, bij represents the original expert rating value of the i-th evaluation object on the j-th indicator; max(bj) and min(bj) represent the maximum and minimum values of the j-th indicator among all evaluation objects, respectively; bij′ is the standardized rating value after negative and dimensionless processing.

Indicator variability calculation: The standard deviation reflects the degree of fluctuation within the indicator’s internal data.

Indicator conflict calculation:

represents the Pearson correlation coefficient between indicators

i and

k.

Information content calculation: The information content

reflects the magnitude of the data associated with indicator

i.

Objective weight calculation: The objective weight

is computed according to the formula shown in Equation (8).

For Equations (5)–(8), Y is number of evaluation objects. H is the total number of evaluation indicators (12 in this example). Bij’ is the standardized value of the i-th object on the j-th indicator (see Formula (4)). bj’ is the average standardized value of the j-th indicator. σj is the standard deviation of the j-th indicator, representing the variability of the data for that indicator (Formula (5)). rik is the Pearson correlation coefficient between the i-th and k-th indicators, used to measure the correlation between indicators (Formula (6)). Cj is the amount of information contained in the j-th indicator and is determined by the product of its variability and its conflict with other indicators (Formula (7)). The larger the amount of information, the greater the role of this indicator in distinguishing design advantages and disadvantages. ϖj is the objective weight calculated by the CRITIC method for the j-th indicator, which is determined by the proportion of its information content to the total information content of all indicators (Formula (8)).

The results of the objective weight calculation are presented in

Table 11.

Table 11 shows that certain indicators—such as C

3 and C

4, as well as C

5 and C

6—exhibit identical weight values. This outcome arises from the computational principles of the CRITIC method, in which the weight is determined by both indicator variability and conflict intensity. The similar expert-assigned mean scores for C

3 and C

4 indicate that the degree of dispersion in expert evaluations for these two indicators is nearly the same. Moreover, the results reveal that C

3 and C

4 share highly similar patterns of correlation with the other indicators, leading to identical conflict indices. Consequently, their objective weight values are equal.