Abstract

Voltage monitoring circuits are a fundamental block in energy-harvesting-powered applications, as typically the system operation has to be enabled only after a certain supply voltage is reached after a cold start or intermediate voltage levels have to be detected during start-up. The voltage values of interest vary depending on the specific system; hence, a versatile voltage monitoring circuit scheme that can be easily adapted for the desired voltage is particularly appealing. Furthermore, in energy-harvesting-powered applications, special care must be paid to power consumption minimization, in order to ensure self-sustainability of the system, and to area occupation, thus enabling a small form factor and low cost. To address these requirements, this paper proposes a novel, highly versatile voltage-monitoring circuit for energy-harvesting-powered applications that minimizes power consumption and area occupation. Indeed, the proposed voltage monitor implementation, relying on cascaded PMOS-based and NMOS-based voltage detectors, can be easily adapted to any desired voltage level, also achieving high voltage levels to be detected by adding (multiple) diode-connected transistors in the first stage while maintaining the voltage monitor output rail-to-rail and avoiding static power consumption from the cascaded digital gates. The proposed solution, targeting a 800 mV voltage level to be detected, was designed in a 180 nm CMOS triple-well technology and extensively validated through simulations in Cadence Virtuoso. Furthermore, it was bench-marked with an implementation in the same process based on the standard voltage monitor scheme (including the necessary cascaded logic gates for achieving a rail-to-rail output) available in literature, showcasing a reduction up to about 1700× in power consumption and 3.87× in area occupation, considering a preliminary area estimation, when triple-well devices are employed, whereas, when relying only on standard devices, although no significat area benefit is obtained, a reduction of up to about 400× in power consumption is achieved.

1. Introduction

In recent years, Internet of Things (IoT) distributed wireless sensor networks, smart home sensor applications, and wearable biomedical and healthcare devices have become widespread [1,2,3,4]. These types of systems typically require minimizing form factor and cost, as well as ensuring self-sustained operation with a prolonged lifetime; hence, the need for energy harvesting from environmental sources as a way to enable battery-free solutions has emerged [5]. The employed energy sources are various: light [3,4,6,7,8], heat [2,9,10,11,12], mechanical vibrations [13,14,15,16,17], radio-frequency [18,19], and bio-fuel cells [20]. Independent of the used energy type, however, all systems require reaching a predetermined voltage before fully starting up the device and/or to detect intermediate voltage levels during cold start: typically, such voltage levels fall within the 250 mV–1 V range [1,2,3,8,9,11,12,21]. A voltage monitor, also known as a level or voltage detector, is therefore required for determining when the desired voltage level has been reached.

Conventional voltage monitoring circuits employ a temperature-independent voltage reference and a comparator [22,23,24]: such solutions, however, are not suitable for ultra-low-power energy harvesting systems, as they would feature a significant power consumption in the range of tens or hundreds of nW. Indeed, in energy-harvesting-powered solutions, special care must be paid to power consumption minimization in order to make the system self-sustainable. Moreover, as many applications target room temperature use (e.g., wearable or implantable healthcare devices, smart home sensor networks), the temperature-insensitivity requirement can be relaxed. Hence, specific voltage monitoring circuits, usually based on a simple two-transistor (2T) structure [21], have been developed for energy harvesting systems [1,2,3,21]. Such structures, however, face limitations when the voltage level to be detected falls within the higher half of the 250 mV–1 V range. This paper instead provides a highly versatile voltage monitoring circuit solution, which can be adapted to any required voltage level while overcoming the issues of the voltage monitors available in the literature. Indeed, the proposed voltage monitoring circuit, by cascading PMOS-based and NMOS-based voltage monitors, enables also implementing high voltage levels while minimizing area and power consumption. Indeed, the proposed solution allows adding (multiple) diode-connected transistors to the 2T structure, thus achieving high voltage levels to be detected while maintaining the voltage monitor output rail-to-rail and avoiding static power consumption from the cascaded digital gates.

This paper is organized as follows: Section 2 describes the voltage monitor solutions for energy harvesting systems available in the literature and their drawbacks; Section 3 illustrates the proposed voltage monitoring circuit; Section 4 provides a design example, employing a 180 nm CMOS technology, of the proposed voltage monitor, benchmarking it with the standard state-of-the-art solution; Section 5 concludes the paper.

2. State-of-the-Art Overview

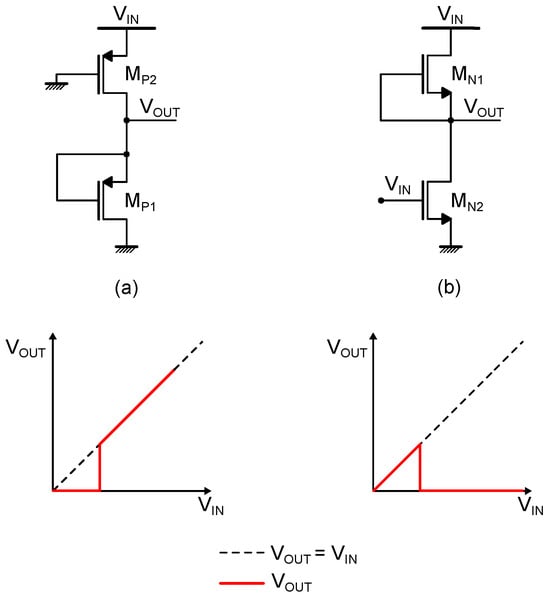

Voltage monitoring circuits in energy harvesting applications typically require providing a zero-voltage output for input voltages lower than a predetermined threshold and a voltage output equal to the supply voltage for input voltages above the threshold. The threshold or trigger voltage constitutes the required minimum voltage for full start-up or for transitioning from one start-up phase to the following one. The simplest voltage monitoring circuit is composed of two transistors of the same type [1,21]: the PMOS-based implementation is illustrated in Figure 1a, whereas the NMOS-based one is shown in Figure 1b. The principle of operation for both realizations is analogous: the only difference is given by the fact that the resulting logic is complementary. In particular, contrary to the PMOS-based implementation, the NMOS-based solution outputs a voltage equal to the input voltage for input voltages lower than the trigger voltage and a zero voltage for input voltages higher than the trigger. Hence, an additional inverter in the NMOS-based case is required in order to maintain the same logic. When the input voltage is very low, however, the case when the output voltage is equal to the input voltage might not be correctly discriminated from the one where the output voltage is zero, since input voltages lower than the MOS devices threshold would be unable to correctly operate the logic gates: for this reason, only PMOS-based voltage monitoring circuits are found in the literature. Nevertheless, as will be seen in the next section, also relying on NMOS-based solutions might be of interest.

Figure 1.

Schematic representation of the basic (a) PMOS-based and (b) NMOS-based 2T voltage monitoring circuits.

Considering the two-transistor (2T) PMOS-based solution, the trigger voltage is determined by the comparison between the currents of transistors and . Both transistors operate in the subthreshold region, as is biased with zero gate-to-source voltage; thus, supposing that the transistor is saturated (its source-to-drain voltage is larger than four times the thermal voltage), the source-to-drain current flowing through is given by

where is the transistor source-to-gate voltage, its threshold voltage, k the Boltzmann constant, q the elementary charge, T the temperature expressed in Kelvin degrees, and n is the subthreshold slope coefficient.

- The term is equal towhere is the carrier’s (in this case holes) mobility, is the gate oxide capacitance per unit area, and W and L are the width and length, respectively, of the transistor.

- Hence, the current can be expressed aswhere is the input voltage, acting as supply for the 2T voltage monitoring circuit.

- Analogously, the source-to-drain current of is given byCurrent is constant and only depends on the transistor aspect ratio. The threshold or trigger voltage , corresponding to the detected level, is defined as the input voltage when the output voltage changes from low to high, which corresponds to the input voltage when and are equal. From Equations (3) and (4), the value of is derived:

- Hence, the trigger voltage depends on the thermal voltage and on the sizes of transistors and . The temperature dependency is not critical, as many energy harvesting applications (e.g., body-wearable devices, smart home sensor networks, and indoor solar cells) target room temperature use.

If two transistors with different threshold voltages [3] are used, the trigger voltage will become

where and are the threshold voltages of and , respectively. For simplicity, the same subthreshold slope coefficient n has been considered for the two transistor types, but they could differ; however, since the variation would be small, Equation (6) represents a good approximation.

It is evident from Equations (5) and (6) that in order to obtain relatively large trigger voltages, on the order of a few hundred mV, very large transistor ratios, which are not suitable or practical for implementation, are required.

The same derivations can be carried out in the case of NMOS-based voltage monitoring circuits by substituting with and with , and defining as when changes from high to low, which still corresponds to when and are equal.

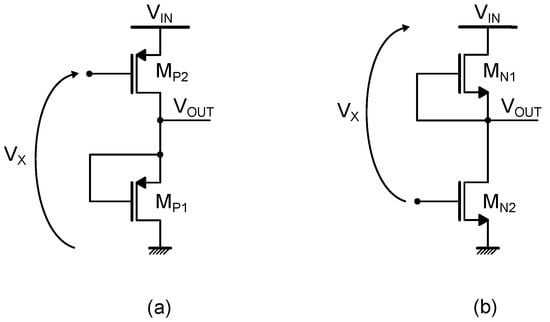

In order to increase the trigger voltage, a possibility is supplying an additional bias to transistor (or ) [4,9], as illustrated in Figure 2, which shows the PMOS-based implementation and the dual NMOS-based realization. In this way, carrying out the same derivation as for the previous case, the trigger voltage becomes

Voltage is typically provided by some crude voltage reference (e.g., 2T or 3T voltage references [25]). However, implementing large values of is again not practical with two-transistor or three-transistor architectures, and using more complex structures may not be feasible or would dramatically increase the power consumption.

Figure 2.

Schematic representation of the basic (a) PMOS-based and (b) NMOS-based 2T voltage monitoring circuits with additional voltage biasing.

Another possibility to increase the trigger voltage is going from the 2T circuit of Figure 1 to the three-transistor (3T) structure of Figure 3 by adding a diode-connected transistor (or ), which features the same size as () [1,21]. Since and share the same size and the same current flows through them, from Equation (1), their source-to-gate voltages, and , are the same, so

where is the voltage found at the source of .

Figure 3.

Schematic representation of the (a) PMOS-based and (b) NMOS-based voltage monitoring circuits with an additional diode-connected transistor.

- Therefore, the trigger voltage becomeswhich is twice the trigger voltage of a 2T voltage monitoring circuit with the same and sizes. To implement the same trigger voltage, therefore, a significant reduction of the transistor sizes is enabled. The price to pay for the trigger voltage increase is the fact that the output voltage for input voltages larger than the threshold is no longer equal to : indeed, it becomes equal to minus the diode-connected transistor voltage drop, which is equal to , as derived from Equations (8)–(9). In order to restore the full dynamic, two inverters, supplied between ground and , must be cascaded to amplify the voltage swing. The same issue arises also in the NMOS-based implementation, where the output voltage for input voltages larger than the trigger voltage is not equal to zero but to the diode-connected transistor voltage drop (i.e., ). As the cascaded inverter will feature an input voltage different from its positive or negative supply, it will exhibit a non-zero static power consumption, which can constitute a significant drawback in systems supplied through energy harvesting.

In principle, it is possible to stack multiple diode-connected transistors in order to obtain a trigger voltage that is three times or higher than that of the 2T architecture. However, as the output voltage would become minus the diode voltage drops (for the PMOS-based solution), if the resulting output voltage is too low, it would fail to be properly detected as being at a high level by the cascaded inverter. The dual problem (the output voltage not recognized as low level) would arise in the NMOS-based implementation. Hence, in practice, only one diode-connected transistor can be added.

In order to avoid the power consumption increase in the 3T architecture, a cross-coupled voltage monitoring circuit, delivering a full-swing output, was proposed in [2]. It consists of one PMOS-based and one NMOS-based structure connected in a cross-coupled fashion, implementing a positive feedback, which enhances the switching speed. In this case, however, the trigger voltage expression becomes extremely complex, with multiple conditions, which should be simultaneously satisfied, imposed on the transistor sizes, as both PMOS and NMOS voltage detectors should share the same trigger voltage as well. With this type of structure, therefore, proper sizing of the transistors to obtain the desired trigger voltage value cannot be done by hand and requires instead several iterations and relying on numerical simulation methods.

3. Proposed Voltage Monitoring Circuit

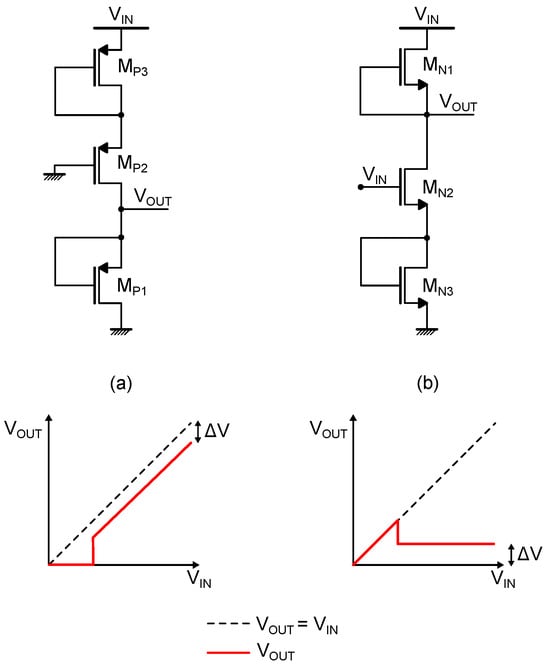

There exists, therefore, no voltage monitoring circuit in the literature simultaneously satisfying small-area, minimized power consumption and easy tunability requirements. This paper instead proposes a highly versatile solution, which can implement any desired trigger voltage while minimizing both area and power consumption. The foundation for this novel type of voltage detector lies in two main considerations: (i) the fact that the output of a 2T structure is rail-to-rail and therefore would ensure no static power consumption for any cascaded logic gate and (ii) the characteristics of generalized PMOS and NMOS voltage detector circuits, which are illustrated schematically in Figure 4a and Figure 4b, respectively.

Figure 4.

Schematic representation of the generalized (a) PMOS-based and (b) NMOS-based voltage monitoring circuits.

A generalized voltage monitoring circuit, either PMOS-based or NMOS-based, is constituted by the core 2T structure ( or ), with the addition of a biasing voltage to the transistor (or ) and to n diode-connected (or ) transistors sharing (or ) size. As seen in Figure 2, the biasing voltage in the case of a PMOS solution must be a fixed voltage with respect to the ground, whereas in the dual case of an NMOS device, it must be a fixed voltage with respect to . The output voltage of a generalized PMOS-based voltage detector, for input voltages larger than the trigger voltage, is a fixed voltage , determined by the diode drops, with respect to ; the of a generalized NMOS-based voltage monitoring circuit, instead, for input voltages larger than the trigger voltage, is a fixed voltage , determined by the diode drops, with respect to the ground. The output voltage, for input voltages larger than the trigger voltage, of a PMOS-based solution, therefore, meets exactly the requirements for the biasing voltage of an NMOS-based implementation (and vice versa). When the input voltage is lower than the trigger voltage, the in the case of an NMOS-based solution is ; if applied as biasing voltage of a PMOS-based voltage monitor, it would bias with a negative , and therefore the output voltage would be zero. Conversely, when the input voltage is lower than the trigger voltage, in the case of a PMOS-based solution is zero; if applied as biasing voltage of an NMOS-based voltage monitor, it would bias with a negative and therefore the output voltage would be . Hence, when the input voltage is below the trigger voltage in the PMOS-based solution and is used as the biasing voltage of an NMOS-based implementation, the output voltage of the NMOS-based circuit is compliant with the fact that the input voltage is below the PMOS-based voltage detector threshold. The same holds true also when considering the output voltage of an NMOS-based solution applied as biasing the voltage to a PMOS-based voltage detector.

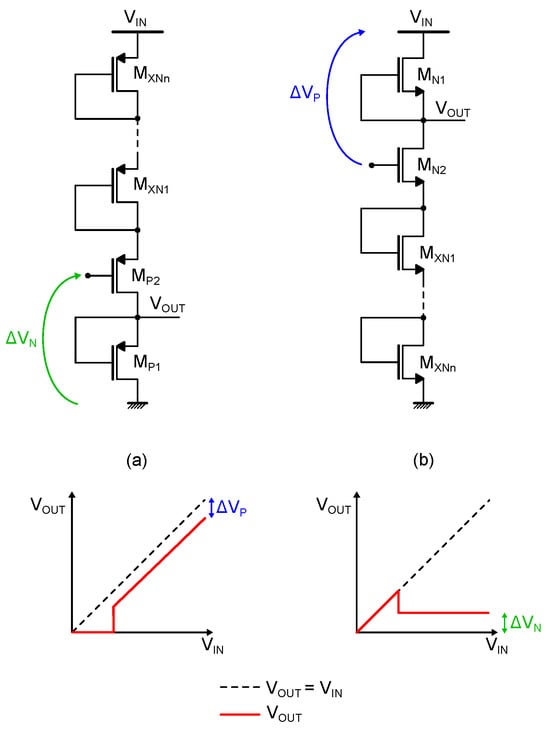

Hence, it becomes apparent that cascading PMOS and NMOS-based solutions (and vice versa) is possible. Furthermore, if the last stage of the cascade is a 2T device, the output would be rail-to-rail, and no static power consumption issue would arise for any cascaded logic gate. This allows employing freely multiple stacked diode-connected transistors in stages different from the last, thus facilitating the implementation of relatively large trigger voltages.

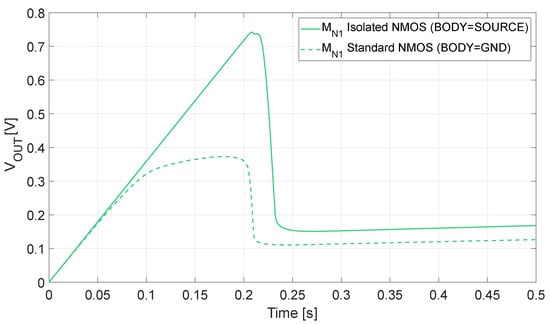

In principle, any number of stages could be used, provided that PMOS and NMOS based structures are alternated and that the last stage is a 2T structure. However, in order to minimize area and power consumption, minimizing the number of stages is required. As explained previously, a PMOS-based voltage monitor is preferable with respect to an NMOS one when it has to interface any logic gate, hence a PMOS-based 2T output stage should be selected. Moreover, it must be taken into account that the illustrated output voltage shapes for the various voltage detectors are obtained only provided that the transistors ( and in particular, considering an NMOS or a PMOS stage, respectively) do not suffer from body effect. Ensuring that no PMOS transistor suffers from body effect is possible in any technology by shorting the transistor body and source terminals, however the same does not hold true for NMOS devices, as the process used for the implementation must support the realization of triple-wells. When suffers from body effect, does no longer feature a sharp shape: Figure 5 illustrates an NMOS voltage detector output waveform when a triple-well NMOS (without body effect) or a standard NMOS (suffering from body effect), maintaining the same width and length, are employed for in a 3T structure. The results are obtained by means of a transient simulation in Cadence Virtuoso, increasing the voltage in a ramp fashion. The fact that in the standard NMOS case becomes almost flat, before going to the diode voltage drop after reaching the designed trigger voltage, limits the performance of the proposed voltage monitoring circuit, obtained by cascading PMOS- and NMOS- based voltage detectors. The details of the limitations and how to possibly overcome them will be discussed later on.

Figure 5.

Simulated output voltage of an NMOS voltage detector when employing isolated (triple-well) or standard NMOS devices for .

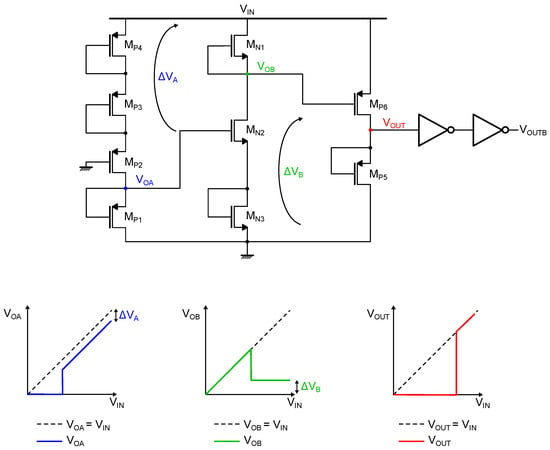

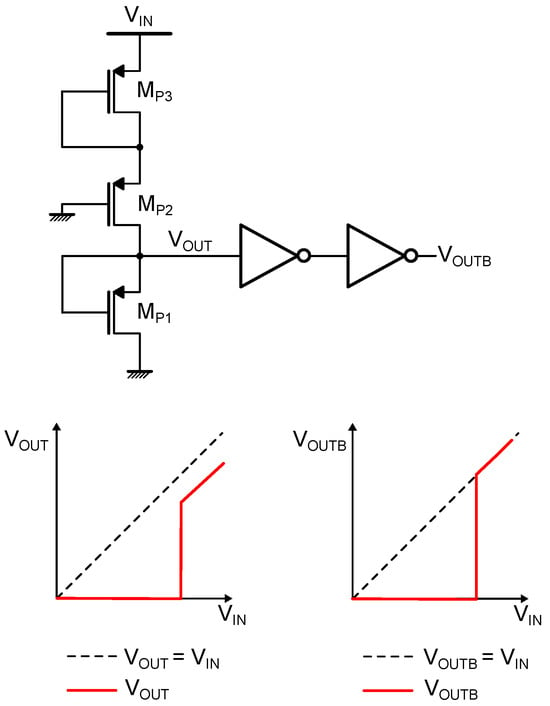

These considerations led to the definition of the proposed voltage monitoring circuit, illustrated in Figure 6. It consists of three stages: a PMOS-based first stage, an NMOS-based second stage, and a PMOS-based output stage. The first stage does not feature any extra biasing (the gate of is connected to ground) and includes multiple additional diode-connected transistors in order to implement a rather large trigger voltage. The second stage exploits the first-stage output as extra biasing and, featuring an additional diode-connected transistor, implements the third-stage voltage biasing. The third and final stage is implemented through a PMOS-based 2T structure, ensuring full rail-to-rail output swing. Eventually, two cascaded inverters can be added to act as a digital buffer and drive any logic gate. The proposed solution targets an 800 mV trigger voltage and therefore employs two diode-connected transistors in the first stage; however, by adjusting the number of diodes in the first stage and the transistor sizes, any output voltage could be implemented. As the employed technology allows it, the proposed implementation uses an NMOS device in a triple-well for realizing , thus shorting its body terminal to its source, while other NMOS transistors are standard devices with the body connected to the ground. All PMOS transistors feature body and source terminals shorted together.

Figure 6.

Schematic representation of the proposed voltage monitoring circuit.

We now consider the operation of the proposed circuit and how to size it to realize the desired trigger voltage. At first, when the input voltage is below the trigger voltage of the first stage, (i.e., the first stage output) is zero, is equal to , and is zero. When exceeds the trigger voltage of the first stage, becomes equal to , thus providing the biasing for in the second stage. As long as the trigger voltage of the second stage is not exceeded, then stays equal to and stays at zero. When exceeds the trigger voltage of the second stage, switches to and provides the biasing for the third stage. When exceeds the trigger voltage of the third stage as well, becomes equal to . Since one voltage detector cannot change its output until the previous voltage detector stage has reached its trigger voltage, a sequential operation takes place.

The trigger voltage of the first stage as a stand-alone, considering that two diode-connected transistors are employed, is

The trigger voltage of the second stage as a stand-alone when the first stage is providing the additional bias is

where

The trigger voltage of the third and last stage as a stand-alone when the second stage provides the additional bias is

where

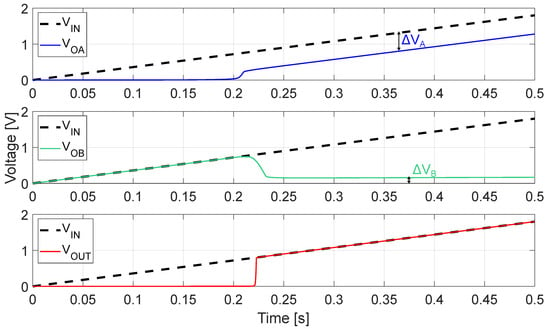

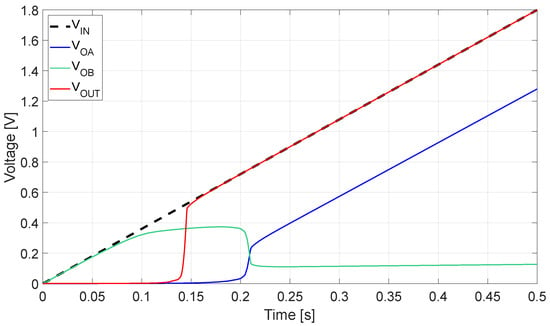

As explained previously, however, the sequential nature of the operation must be taken into account for deriving the trigger voltage of the overall voltage monitoring circuit. Indeed, it must be remembered that one stage cannot be triggered until the previous one has. Hence, the overall voltage monitoring circuit’s effective trigger voltage is the largest among , and . Exploiting this property, it is therefore possible to set the desired output trigger voltage solely by adjusting , provided that the stand-alone trigger voltage of the successive stages is lower. Alternatively, it is also possible to exploit the following stages to increase the resulting overall output trigger voltage by realizing cascaded voltage detector stages with increasingly larger stand-alone trigger voltages. The simulated voltage waveforms found at the various nodes of the proposed voltage monitoring circuit in typical conditions are shown in Figure 7.

Figure 7.

Simulated node voltages as a function of time for the proposed voltage monitoring circuit in nominal conditions.

The illustrated operation description is valid provided that, in addition to the PMOS devices, transistor also does not suffer from a body effect, and it is therefore implemented through a triple-well device. If instead a standard NMOS device is used, the flat shape shown in Figure 6 and found at affects the sequential operation: indeed, without the sharp shape, there is no longer a clear discrimination at the NMOS stage output between the cases when is below or above the trigger voltage. This results in a lower trigger voltage at the overall voltage monitoring circuit’s output. In order to increase the trigger voltage, the aspect ratio of should be increased, the ratio of should be decreased, and/or the number of diode-connected transistors should be increased. Also, increasing the stand-alone trigger voltage of the last stage, and thus increasing (decreasing) the aspect ratio of (), can help. Intervening in the first stage, instead, is not useful, as changing its trigger voltage has no significant effect on the resulting flat shape. Employing isolated (triple-well) NMOS devices, when possible, is therefore clearly preferable. Alternatively, it is possible to implement the proposed circuit only with standard devices, but at the cost of increasing the area occupation. The simulated voltage waveforms found at the various nodes of the proposed voltage monitoring circuit when employing a standard NMOS device for are shown in Figure 8. It is evident that, by maintaining the same transistor size when employing only standard devices, a lower trigger voltage is determined with respect to the case when a triple-well device is used for .

Figure 8.

Simulated node voltages as a function of time for the proposed voltage monitoring circuit in nominal conditions when employing a standard NMOS device for implementing .

It should be noted that the response speed of voltage monitoring circuits for energy-harvesting-powered applications is not critical: indeed, the input voltage typically rises slowly (the rise time is on the order of hundreds of ms) as the charging of a large input storage capacitance is involved. Hence, when considering the evolution of the nodes with respect to time, considering a 500 ms rise time for the input voltage is reasonable.

4. Design Example

The proposed voltage monitoring circuit, implementing an 800 mV trigger voltage in nominal conditions, was designed in a 180 nm CMOS process supporting triple-well implementation. The selected transistor sizes are reported in Table 1. Each transistor features a modular structure, where the total width is given by the multiplicity times the reported W value. All transistors are realized with standard devices, with the exception of , which is implemented in a triple-well. All PMOS transistors and feature the body shorted to the source, whereas and have the body connected to ground.

Table 1.

Employed Transistor Sizes for the Proposed Voltage Monitoring Circuit Solution.

In order to be able to provide a fair comparison (the same technology, same desired trigger voltage) with the state-of-the-art voltage detector structures, a 3T PMOS-based voltage monitor was designed as well for benchmarking. This topology was selected as it represents the go-to solution for the targeted trigger voltage value. The designed standard voltage detector, including the cascaded digital buffer for restoring the full output swing, is illustrated in Figure 9. The selected transistor sizes are reported in Table 2.

Figure 9.

Schematic representation of the standard voltage monitoring circuit used for benchmarking.

Table 2.

Employed Transistor Sizes for the Standard Voltage Monitoring Circuit Used for Benchmarking.

For both the proposed and standard structures, the inverters were implemented with an NMOS featuring nm, nm and , and a PMOS featuring nm, nm and .

Both the proposed and the reference standard solutions were characterized through extensive simulations in Cadence Virtuoso.

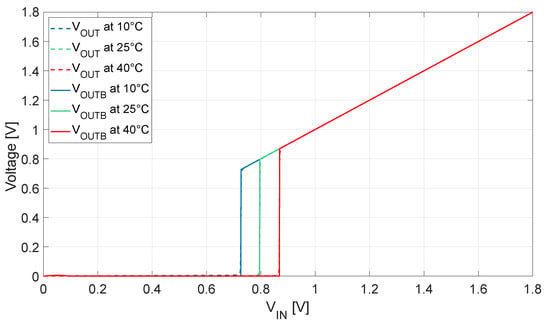

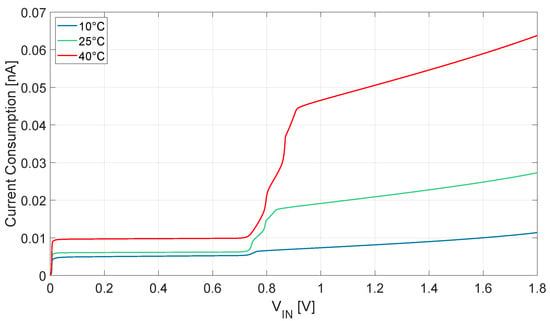

The proposed voltage monitoring output voltages and (before and after the digital buffer, respectively), under typical process conditions, as a function of the input voltage are reported in Figure 10. The current consumption, excluding the inverters as they should feature zero power consumption, as a function of , is illustrated instead in Figure 11. As expected, a difference in the trigger voltage is found at different temperatures: as the variation is ±100 mV between 10 °C and 40 °C, this is in line with the state of the art and acceptable for energy-harvesting-powered applications targeting room temperature use. It can be noticed that the current consumption, directly determined by the leakage of the transistors with zero voltage, increases with both temperature and . In order to assess the proposed and standard circuit current consumption, therefore, the case for = 1.8 V (i.e., the maximum transistor voltage rating) will be considered as it represents the worst possible case.

Figure 10.

Simulated output voltages (pre- and post-inverters) as a function of the input voltage for the proposed voltage monitoring circuit in nominal conditions.

Figure 11.

Simulated current consumption (excluding inverters) as a function of the input voltage for the proposed voltage monitoring circuit in nominal conditions.

The proposed voltage monitoring circuit performance was also verified against process and mismatch variations, considering 500 Monte Carlo runs. The simulated trigger voltage values are illustrated in Table 3. The current consumption for the worst input voltage case are reported instead in Table 4. Although zero static power consumption is expected for the inverters, a slight increase in current consumption is found when taking them into account: this is due to their leakage current.

Table 3.

Simulated Trigger Voltage for the Proposed Voltage Monitoring Circuit (500 Monte Carlo runs for each temperature).

Table 4.

Simulated Current Consumption for the Proposed Voltage Monitoring Circuit (500 Monte Carlo runs for each temperature).

As was explained previously, the response speed of the voltage monitoring circuit is not critical. Nevertheless, the proposed voltage detector response time has been evaluated through simulations by applying a voltage step (from 0 to 1.8 V) as input voltage and considering the time required by the node for switching to 1.8 V after the application of the input voltage step: in this way, an equivalent propagation delay time was derived and it was found equal to 3.06 in typical conditions. This time is several orders of magnitude smaller than the typical rise time of the supply voltage in energy-harvesting-powered systems, so it does not affect the operation in such applications.

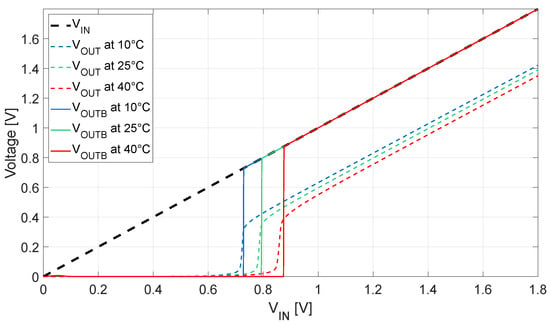

The standard reference solution was characterized as well. The standard 3T voltage detector output voltages and (before and after the digital buffer, respectively), under typical process conditions, as a function of the input voltage are reported in Figure 12. The same variation with temperature as with the proposed solution is found. As expected, for input voltage larger than the trigger voltage is equal to minus the diode-connected transistor voltage drop. The simulated trigger voltages against process and mismatch variations, considering 500 Monte Carlo runs, are reported in Table 5. As the inverters implementing the digital buffer are necessary for restoring the full output swing and are therefore an integral part of the voltage detector, only the current consumption with the inverters is of actual interest. The simulated current consumption for the worst case input voltage, considering 500 Monte Carlo runs including both process and mismatch, is reported in Table 6.

Figure 12.

Simulated output voltages (pre and post inverters) as a function of the input voltage for the standard voltage monitoring circuit in nominal conditions.

Table 5.

Simulated Trigger Voltage for the Standard 3T Voltage Monitoring Circuit (500 Monte Carlo runs for each temperature).

Table 6.

Simulated Current Consumption for the Standard Voltage Monitoring Circuit (500 Monte Carlo runs for each temperature).

Furthermore, the response speed of the standard voltage detector was evaluated analogously as for the proposed voltage monitoring circuit and a propagation delay equal to 11.3 in typical conditions was found, which, although 3.69 times larger than the one of the proposed voltage monitor, is still several orders of magnitude smaller than the typical rise time of the supply voltage in energy-harvesting-powered systems and therefore not critical.

For completeness, the proposed voltage monitoring circuit was also designed using only standard devices. In this case, in order to obtain a nominal 800 mV trigger voltage, three additional diode-connected NMOS were added in the second stage, and the sizes of , and were adjusted accordingly. In particular, featured a 7.2 width, a 180 nm length and a multiplicity equal to 24; featured a 1.8 width, a 250 nm length, and a multiplicity equal to 48; and featured a 440 nm width, a 8.8 length, and a multiplicity equal to 1. The simulated trigger voltage and current consumption for the proposed standard-devices-only voltage monitoring circuit are reported in Table 7 and Table 8, respectively. The obtained trigger voltage spread is analogous to the one of the solution with a triple-well device implementing , but the current consumption is larger: this is expected as larger size devices were employed, thus giving rise to increased leakage. Nevertheless, the current consumption is still significantly reduced with respect to the standard solution.

Table 7.

Simulated Trigger Voltage for the Proposed Voltage Monitoring Circuit When Employing Only Standard Devices (500 Monte Carlo runs for each temperature).

Table 8.

Simulated Current Consumption for the Proposed Voltage Monitoring Circuit When Employing Only Standard Devices (500 Monte Carlo runs for each temperature).

Comparing the performance of the proposed and standard solution, although their implemented trigger voltage and its variation with temperature, process, and mismatch are roughly the same, as expected, the proposed voltage monitoring circuit clearly outperforms the standard voltage detector in terms of power consumption by orders of magnitude. Indeed, when considering the worst case for a 1.8 V , the standard solution features a 3534 nA current consumption, whereas the proposed solution offers 2.035 nA and 8.268 nA for the triple-well and standard-devices-only implementations, respectively, thus featuring 1736× and a 427× power savings, respectively. The reported power consumption values take into account the inverter’s static power consumption, as the voltage monitor output needs to interface the system control logic and therefore requires being restored to rail-to-rail; hence, the inverter’s power consumption is a direct consequence of the voltage monitor implementation and of its output. Only static power consumption is considered, as the voltage monitor switching event in energy harvesting systems typically happens only during start-up and therefore very rarely; hence, the dynamic power consumption is negligible.

Furthermore, an area estimation (excluding the cascaded inverters) was performed relying on the Cadence LayoutXL dedicated tool, supposing 60% area utilization: the standard 3T structure featured a 75 × 75 area, whereas the proposed voltage detector circuit employing a triple-well device for resulted in a 38.1 × 38.1 area occupation, thus featuring a 3.87× reduction; the proposed voltage monitor circuit realized only with standard devices, instead, resulted in a 74.1 × 74.1 area, only slightly smaller than the standard solution case.

The proposed novel voltage monitor, as well as the standard solution, are compared with the state-of-the-art in Table 9. Typical conditions are considered, as the other reported works do not provide an assessment under process/mismatch and temperature variations. The proposed solution is outperformed in terms of power consumption only by [2], which, however, does not feature the same versatility of the proposed voltage monitoring circuit: indeed, as explained in Section 2, reference [2] requires performing several iterations of numerical simulations in order to properly size the transitors, whereas the transistors’ sizing for the proposed voltage detector can be implemented relying on simple closed-form expressions.

Table 9.

State-Of-The-Art Comparison.

The proposed design example implemented a 800 mV trigger voltage, but any trigger voltage up to the employed transistors voltage rating can be implemented when relying on a triple-well device for realizing : it is sufficient to stack as many diode-connected MOSs in the first stage as required, provided that the obtained trigger voltage does not excess the voltage rating under temperature, process and/or mismatch variations. If only standard devices are used, then the maximum achievable trigger voltage is imposed by the maximum desired area occupation, as the only way to counteract the degradation due to the body effect on is to increase the transistor sizes and/or increase the number of diode-connected transistors in the second stage.

5. Conclusions

This paper has featured a detailed overview of the state of the art for voltage detector circuits used in energy-harvesting-powered applications, highlighting their limitations. In order to address the drawbacks of solutions currently available in the literature, this paper has proposed a novel voltage monitoring circuit solution, relying on cascading PMOS-based and NMOS-based voltage detectors. The proposed voltage monitoring circuit enables power consumption minimization and allows implementing a wide range of trigger voltages, supporting easy tunability without requiring several iterations of numerical simulations. With respect to a standard 3T voltage monitor with the same trigger voltage, the designed 800 mV voltage detector employing a triple-well device exhibits up to a 1736× power consumption reduction while featuring 3.87× less area occupation (considering a preliminary area estimation), whereas the proposed standard-devices-only solution does not offer a significant area advantage but allows reducing the power consumption up to 427 times. The proposed voltage monitoring solution thus clearly outperforms the state of the art when considering ultra-low-power energy harvesting applications.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, E.M.; methodology, E.M.; investigation, E.M.; data curation, E.M.; writing—original draft preparation, E.M.; writing—review and editing, A.C., A.T., E.B. and P.M.; supervision, A.C., E.B. and P.M. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research received no external funding.

Data Availability Statement

The original contributions presented in this study are included in the article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Conflicts of Interest

Author Andrea Tellatin was employed by the company Wasi Srl. The remaining authors (Elisabetta Moisello, Alessandro Cabrini, Edoardo Bonizzoni, Piero Malcovati) declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

References

- Fuketa, H.; O’uchi, S.i.; Matsukawa, T. Fully Integrated, 100 mV Minimum Input Voltage Converter with Gate-Boosted Charge Pump Kick-Started by LC Oscillator for Energy Harvesting. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. II Express Briefs 2017, 64, 392–396. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dezyani, M.; Ghafoorifard, H.; Sheikhaei, S.; Serdijn, W.A. A 60 mV Input Voltage, Process Tolerant Start-Up System for Thermoelectric Energy Harvesting. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2018, 65, 3568–3577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ferro, E.; Brea, V.M.; López, P.; Cabello, D. Micro-Energy Harvesting System Including a PMU and a Solar Cell on the Same Substrate With Cold Startup From 2.38 nW and Input Power Range up to 10 μW Using Continuous MPPT. IEEE Trans. Power Electron. 2019, 34, 5105–5116. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chakraborty, A.; Maity, A. A Time-to-Voltage Converter-Based MPPT with 440 μs Online Tracking Time, 99.7% Tracking Efficiency for a Battery-Less Harvesting Front-End with Cold-Startup and Over-Voltage Protection. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2024, 71, 4499–4511. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gogolou, V.; Noulis, T.; Pavlidis, V.F. Multi-Source Energy Harvesting Systems Integrated in Silicon: A Comprehensive Review. Electronics 2025, 14, 1951. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Basu, J.; Fassio, L.; Ali, K.; Alioto, M. Picowatt-Power Super-Cutoff Analog Building Blocks and 78-pW Battery-Less Wake-Up Receiver for Light-Harvested Near-Always-On Operation. IEEE J.-Solid-State Circuits 2024, 59, 1038–1049. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cabello, D.; Ferro, E.; Pereira-Rial, O.; Martinez-Vazquez, B.; Brea, V.M.; Carrillo, J.M.; Lopez, P. On-Chip Solar Energy Harvester and PMU with Cold Start-Up and Regulated Output Voltage for Biomedical Applications. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2020, 67, 1103–1114. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tran-Dinh, T.; Pham, H.M.; Pham-Nguyen, L.; Lee, S.G.; Le, H.P. Power Management IC with a Three-Phase Cold Self-Start for Thermoelectric Generators. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2021, 68, 103–113. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, S.; Anand, T.; Johnston, M.L. Integrated Cold Start of a Boost Converter at 57 mV Using Cross-Coupled Complementary Charge Pumps and Ultra-Low-Voltage Ring Oscillator. IEEE J.-Solid-State Circuits 2019, 54, 2867–2878. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chou, T.H.; Yu, S.; Bose, S.; Cook, J.; Park, J.; Johnston, M.L. Wireless, Multi-Sensor System-on-Chip for pH and Amperometry Powered by Body Heat. IEEE Trans. Biomed. Circuits Syst. 2023, 17, 782–794. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Liu, L.; Xing, Y.; Huang, W.; Liao, X.; Li, Y. A 10 mV-500 mV Input Range, 91.4% Peak Efficiency Adaptive Multi-Mode Boost Converter for Thermoelectric Energy Harvesting. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. I Regul. Pap. 2022, 69, 609–619. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Bose, S.; Anand, T.; Johnston, M.L. A 3.5 mV Input Single-Inductor Self-Starting Boost Converter with Loss-Aware MPPT for Efficient Autonomous Body-Heat Energy Harvesting. IEEE J.-Solid-State Circuits 2021, 56, 1837–1848. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Muscalu, G.; Firtat, B.; Anghelescu, A.; Moldovan, C.; Dinulescu, S.; Brasoveanu, C.; Ekwinska, M.; Szmigiel, D.; Zaborowski, M.; Zajac, J.; et al. Piezoelectric MEMS Energy Harvester for Low-Power Applications. Electronics 2024, 13, 2087. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Wakshume, D.G.; Placzek, M.L. Optimizing Piezoelectric Energy Harvesting from Mechanical Vibration for Electrical Efficiency: A Comprehensive Review. Electronics 2024, 13, 987. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Fortunati, A.; Moisello, E.; Mozzorecchia, E.; Quartieri, E.; Aprile, A.; Bonizzoni, E.; Malcovati, P. A Class-AB Slew Rate-Enhanced OTA for Triboelectric Sensing Interfaces in Smart Textiles. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE International Symposium on Circuits and Systems (ISCAS), London, UK, 25–28 May 2025; pp. 1–5. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gundu, A.K.; Fassio, L.; Alioto, M. E-Textile Battery-Less Walking Step Counting System with <23 pW Power, Dual-Function Harvesting from Breathing, and No High-Voltage CMOS Process. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE Symposium on VLSI Technology and Circuits (VLSI Technology and Circuits), Honolulu, HI, USA, 16–20 June 2024; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jung, H.; Sharma, Y.; Zuo, L. Digitally Controlled Power Management Circuit with Dual-Functioned Single-Stage Power Converter for Vibration Energy Harvesting. IEEE J. Emerg. Sel. Top. Power Electron. 2022, 10, 3873–3882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Privitera, M.; Ballo, A.; Ali, K.; Dario Grasso, A.; Alioto, M. Sub- μW Battery-Less and Oscillator-Less Wi-Fi Backscattering Transmitter Reusing RF Signal for Harvesting, Communications, and Motion Detection. IEEE J.-Solid-State Circuits 2025, 60, 1947–1958. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sung, G.M.; Chen, S.H.; Choppa, V.; Yu, C.P. Hybrid Radio-Frequency-Energy- and Solar-Energy-Harvesting-Integrated Circuit for Internet of Things and Low-Power Applications. Electronics 2025, 14, 2192. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Talkhooncheh, A.H.; Yu, Y.; Agarwal, A.; Kuo, W.W.T.; Chen, K.C.; Wang, M.; Hoskuldsdottir, G.; Gao, W.; Emami, A. A Biofuel-Cell-Based Energy Harvester with 86% Peak Efficiency and 0.25-V Minimum Input Voltage Using Source-Adaptive MPPT. IEEE J.-Solid-State Circuits 2021, 56, 715–728. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, P.H.; Ishida, K.; Ikeuchi, K.; Zhang, X.; Honda, K.; Okuma, Y.; Ryu, Y.; Takamiya, M.; Sakurai, T. Startup Techniques for 95 mV Step-Up Converter by Capacitor Pass-On Scheme and VTH-Tuned Oscillator with Fixed Charge Programming. IEEE J.-Solid-State Circuits 2012, 47, 1252–1260. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Savanth, A.; Weddell, A.; Myers, J.; Flynn, D.; Al-Hashimi, B. A 50nW Voltage Monitor Scheme for Minimum Energy Sensor Systems. In Proceedings of the 2017 30th International Conference on VLSI Design and 2017 16th International Conference on Embedded Systems (VLSID), 2017, Hyderabad, India, 7–11 January 2017; pp. 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kamakshi, D.A.; Patel, H.N.; Roy, A.; Calhoun, B.H. A 28 nW CMOS supply voltage monitor for adaptive ultra-low power IoT chips. In Proceedings of the 2017 IEEE SOI-3D-Subthreshold Microelectronics Technology Unified Conference (S3S), Burlingame, CA, USA, 16–19 October 2017; pp. 1–2. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Christmann, J.; Beigné, E.; Condemine, C.; Piguet, C. Event-driven asynchronous voltage monitoring in energy harvesting platforms. In Proceedings of the 10th IEEE International NEWCAS Conference, Montreal, QC, Canada, 17–20 June 2012; pp. 457–460. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Moisello, E.; Bonizzoni, E.; Malcovati, P. MOSFET-Based Voltage Reference Circuits in the Last Decade: A Review. Micromachines 2024, 15, 1504. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.