Abstract

The transformer architecture and its attention-based modules have become quite popular recently and are used for solving most computer vision tasks. However, there have been attempts to explore whether other modules can perform equally well with lower computational costs. In this paper, we introduce a nonlinear convolution structure composed of learnable polynomial and Fourier features, which allows better spectral representation with fewer parameters. The solution we propose is in principle feasible for many CNN application fields, and we present its theoretical motivation. Next, to demonstrate the performance of our architecture, and we exploit it for a paradigmatic task: image translation in driving-related scenarios such as deraining, dehazing, dark-to-bright, and night-to-day transformations. We use specific benchmark datasets for each task and standard quality parameters. The results show that our network provides acceptable or better performances when compared to transformer-based architectures, with a major reduction in the network size due to the use of such a nonlinear convolution block.

1. Introduction

Algorithms for improving the quality of digital images, as perceived by humans or exploited by image understanding algorithms, have been the subject of intense research for many years. However, only in the last decade deep learning (DL)-based image processing has been shown to outperform traditional approaches, albeit at a very high training cost. The use of highly complex transformer-based networks with suitable prompts has recently become popular [1]. These networks generate suitable features via multihead attention mechanisms, which are further used for reconstruction [2]. Despite achieving very strong results on synthetic data, there is still room for improvement in real scenarios in terms of image quality and object detection. This limitation arises primarily from their reliance on supervised training with synthetic data. Additional challenges stem from the network size and the very large number of training parameters, which hinder their deployment on edge devices. The use of appropriate features that generalize better, even with fewer parameters, is hence one of the challenges that need to be solved. To address this, we introduce NLCNet (NonLinear Convolution Network), a lightweight architecture that integrates polynomial and Fourier basis functions into an encoder–decoder architecture. Through our experiments, we show that if the network is efficiently formulated, reducing the number of parameters does not result in a significant performance drop. The study therefore pursues two primary objectives:

- Motivate and demonstrate the performance gains achieved by incorporating trainable polynomial and Fourier features into the selected deep learning architecture;

- Design a versatile, lightweight architecture trained in an unsupervised manner that effectively enhances images captured under diverse environmental conditions, with a focus on challenging driving-related outdoor scenarios.

Environmental conditions play a crucial role in the quality of captured images. Fog, haze, and rain can severely impair object visibility, while rain in particular introduces additional complications as it interacts with a vehicle’s windshield or the camera’s optics at varying intensities and speeds. At night or twilight, these problems are compounded by the combination of scarce global illumination and intense local artificial light sources. In recent years, deep learning operators have been proposed to address such challenging cases, as will be discussed in Section 2.

The aforementioned contributions are original:

- Merging universal function approximation in an image translation task to substantially reduce parameter size;

- Introducing learnable polynomial and Fourier features to better represent features for high dimension reconstructions;

- Introducing the first lightweight architecture trained with an unsupervised technique that can effectively handle multiple adverse imaging conditions, including atmospheric haze, rain, low illumination, and night-to-day transformations, while maintaining strong performance in both image quality and object detection.

We have demonstrated that the same architecture can be used for dehazing (Section 4.1), deraining (Section 4.2), dark-to-bright (Section 4.3), as well as night-to-day tasks (Section 4.4), and that it shows promising results in each case. The theoretical motivation—that the choice of learnable basis functions at the beginning of the network generates suitable features that would otherwise require several layers to learn, thereby allowing the network to converge faster with fewer parameters—is verified across different tasks (Tables 10 and 13). Experiments show that adding learnable polynomial and Fourier features improves network performance even with a 50% reduction in network size (achieved via layer reduction). Overall, the architecture is capable of outperforming larger, fully supervised architectures in scene-understanding tasks such as object detection in hazy or rainy environments (Table 7). We wish to underscore that we use unsupervised training for our architecture. As better discussed in Section 4, standard supervised training often implies using synthetic images, which affect the generalization ability of the network to real-world images.

The rest of the paper is organized as follows. We begin by providing a motivation for the proposed approach in Section 1. Section 2 presents related background on image restoration techniques as well as adaptive activation functions. The network structure and complete training details are described in Section 3. Experimental results for dehazing, deraining, low-light enhancement, and night-to-day translation are presented in Section 4, with ablation studies included in Section 5. Finally, Section 6 concludes the paper.

A Motivation for the Proposed Approach

The success of neural networks and their various variants in solving nonlinear processing problems stems from their property of being universal approximators [3]. By increasing the number of neurons or the number of hidden layers, these networks can approximate any nonlinear function arbitrarily well. The property of being a universal approximator is not exclusive to neural networks but is shared by many families of functions. The Stone–Weierstass theorem states the following:

“Let be an algebra of real continuous functions on a compact set K. If separates points on K and if vanishes at no point of K, then the uniform closure of consists of all real continuous functions on K”.

According to this theorem, any algebra of real continuous functions on a compact set that both separates points and does not vanish at any point can serve as a universal approximator. An algebra, in this context, refers to a set of functions closed under addition, multiplication, and scalar multiplication. This means that (i) , (ii) , and (iii) for , , and any real constant c. Examples of algebras that meet the conditions of the Stone–Weierstrass theorem include the monomials , with , and their linear combinations, i.e., polynomials. Another example consists of the functions x, , and , with a and b real constants, their products, and their linear combinations. While monomials are very sensitive to the input signal amplitude, trigonometric functions exhibit lower sensitivity and greater robustness to variations in signal amplitude. It is worth noting that polynomials and trigonometric functions are at the basis of functional link artificial neural networks, which were introduced in the 1980s [4], and remain widely used in applications due to their simplicity. They are also at the basis of the popular Volterra filters [5] and of the Fourier nonlinear filters [6], used in signal processing applications. Trigonometric functions have been used as activation functions in neural networks, as shown in [7,8,9,10], by applying sine or cosine functions to all layers of the network, sometimes in combination with other non-periodic activation functions. Fourier Neural Networks, composed of a single hidden layer with a trigonometric or other orthogonal activation function, have been proposed in [11]. This manuscript explores the utilization of the universal approximation capabilities of sine and cosine functions to enhance the performance of convolutional deep neural networks. We hold the conviction that, particularly when the neural network features a limited number of hidden layers, introducing a nonlinear expansion of the input data can significantly elevate its capacity for function approximation. This intuition has been affirmed within the context of the specific applications at hand. In this context, the nonlinear expansion is achieved by incorporating input data denoted as x, along with , , and their cross-products. This set provides a rich collection of nonlinear basis functions that are linearly combined in the first stage of the network. Consequently, we can interpret the resulting neural network as actively processing nonlinear functions of the input data, all of which are optimized in conjunction with the network itself. Concerning the selection of the constants a, and b, we conducted a systematic trial-and-error procedure to determine their optimal values for the specific application. Notably, the results demonstrated that the outcomes are robust with respect to the choice of such values. Experiments with different coefficients are demonstrated later in Section 5.

2. Related Work

In this section, a brief review of the works related to this research is provided. In particular, the first subsection deals with NNs for image restoration, while the second subsection discusses adaptive activation functions that employ sine and cosine functions, similar to those adopted in this work.

2.1. Image Restoration Networks

Image enhancement goals are achieved with neural networks, which vary depending on their baseline architecture (e.g., U-Net-based, transformer-based), and their attention mechanisms and loss functions. Over the last few years traditional convolution operations along with skip connections have been augmented with different operations like channel attention, depthwise convolutions, simple gate operations replacing nonlinear ReLU and GeLU. A few relevant architectures demonstrating the above are discussed here. Most of these networks demonstrate different enhancing tasks such as deraining, deblurring, denoising, and dehazing. Some of these are also applied to low-light images to perform a dark-to-bright light processing task. Ref [12] utilizes a transformer-based network with gated depthwise convolutions and a multihead depthwise convolution-based attention map. Ref. [2] introduces a Multi-AXIs gated MLP (MAXIM) architecture that uses spatial projections in a local and global manner with block-based and grid-based arrangements to extract features. Ref. [13] introduced MPRNet, a network that utilizes a multi-stage approach, where each stage consists of a restoration block and a fusion block. Another transformer-based technique, Uformer [14], introduces locally-enhanced non-overlapping window-based attention along with a multiscale restoration modulator. Some researchers use a gated context aggregation module that adaptively aggregates contextual information [15] or multi-scale feature extraction, fusion and feature attention network [16] for dehazing restoration tasks. Some authors utilized the channel attention mechanism to enhance feature learning across various levels. One example includes a ChaIR dehazing algorithm [17] using a channel attention mechanism in both frequency and spatial domains. Some other examples of frequency and wavelet domain include [18,19]. The former uses a supervised cyclegan to refine a dark channel prior based transmission map in the Fourier domain for hazy image restoration while the later uses both spatial and frequency features to train an enhancement network. Ref. [20] applies multiple wavelet feature based normalization blocks for training an enhancement network. While majority of the networks discussed above use a supervised learning technique, attention has also been paid to unsupervised learning techniques using GANs or diffusion strategies [21,22,23,24,25]. Finally, multiple prompt-based studies [1,19,26,27] have attracted significant attention in recent years. These networks generate a prompt from the input image and use it to regulate the type of translation to be applied. They are typically trained on combinations of hazy, rainy, and noisy data and can thereby produce suitable enhancements for a wide range of input images. Most of these networks require a lot of learnable parameters and their generalization ability across different scenes is uncertain. Solutions involve considering learnable function approximators or adaptive activation functions.

2.2. Adaptive Activation Functions

The use of activation functions for better convergence is a common practice. A neural network with a sine activation function was first proposed in [7]. Compared to sigmoid activation functions, sine activation functions have been shown to improve accuracy and reduce training [8]. In [28], it is demonstrated that sinusoidal activation functions enable NNs to model fine details and high-frequency components with higher accuracy. The combination of sinusoidal and other activation functions has been proposed in [9]. Trigonometric activation functions are also used in the so-called Rowdy-Net, a particular case of the Kronecker neural network [10], which provides a general framework for neural networks with adaptive activation functions. In Rowdy-Nets, sine or cosine expansions are combined with a regular activation function at each layer to introduce highly fluctuating, irregular, or noisy terms in an adaptive activation function. According to [10], ‘the purpose of choosing such fluctuating terms is to inject bounded but highly non-monotonic, noisy effects to remove the saturation regions from the output of each layer in the network.’ Since the expansion is applied in each layer, the number of adapted parameters inevitably increases. Even though it does not apply trigonometric functions, it is worth mentioning that [29] also considers an adaptive activation function. Specifically, it modifies the traditional sigmoid activation function using exponents and logarithms with different bases and achieves better classification results thanks to its tuning flexibility.

3. Methodology

We have two goals in mind when proposing the image translation architecture: making it lightweight and unsupervised.

To this end we propose NLCNet, a lightweight unsupervised image translation model. It extends a standard ten-block Encoder-Decoder (EnDec) with an input nonlinear basis expansion layer, enabling training on unpaired images through cycle loss [30], as in style transfer tasks. The design demonstrates that suitable polynomial and Fourier function approximators can provide strong performance even with a simple architecture and can be applied to other backbones as well.

It should be noted that the approaches in Section 2.2 differ significantly from the one we propose here. Instead of using adaptive activations, we apply nonlinear expansions and their cross-products to the inputs. We leverage the universal approximation property of these functions to enhance the network’s approximation capacity, thereby reducing the number of layers and parameters considerably. We observe that the network optimizes better when the basis functions are applied on selected layers. The choice of basis functions and their application procedure in our translation task differ from the other existing adaptive activation functions enabling them to approximate low and high frequencies simultaneously, providing better feature representations. Furthermore, unlike architectures which directly use a wavelet transform or cosine transform as the network input, the current approach uses learnable coefficients to determine optimal interactions among the channels representing different basis functions. Compared to architecturally heavy transformer networks, which require more storage space and computational resources, the same or even better performance and generalization is obtained with fewer number of parameters.

The use of an encoder–decoder baseline for image translation tasks in low light environments is demonstrated in [31] using a geometric consistency loss and a contextual loss to ensure structural and semantic consistency in the generated image along with cycle reconstruction and adversarial loss. In the current work, we aim to demonstrate the effectiveness of using polynomial and Fourier basis with any baseline. We validate that these components can perform the intended tasks, as anticipated in Section 1, and, more importantly, that such nonlinearities at the beginning of the network can provide substantial feature-space transformations. Such transformations enable the network to perform reconstruction tasks such as dehazing and deraining even with fewer layers compared to a standard CNN. In fact, for dehazing, both nonlinear intensity transformations and oscillatory patterns—such as edges and textures—can be represented more effectively using a combination of polynomial and Fourier bases. Similarly, for deraining, the polynomial terms model the smooth background, while the Fourier terms capture the rain streaks.

In a conventional CNN approach, the output of layer k using filter weights and bias from layer input is given by Equation (1):

In contrast, adaptive activation functions are shown in Equation (2),

where the single activation of Equation (1) is replaced with a weighted sum of n different activation functions using a scale factor . Some common choices of are relu, sine, etc. While Equations (1) and (2) represent fixed and adaptive activations, our model is depicted in Equation (4):

and shows the use of P different basis functions to approximate before applying and bias . As discussed before, we use a mixture of polynomial and Fourier bases. A few sample bases are also shown in Equation (4). In order to capture nonlinear interactions, we further obtain the products , , etc. These can also be extended to higher orders.

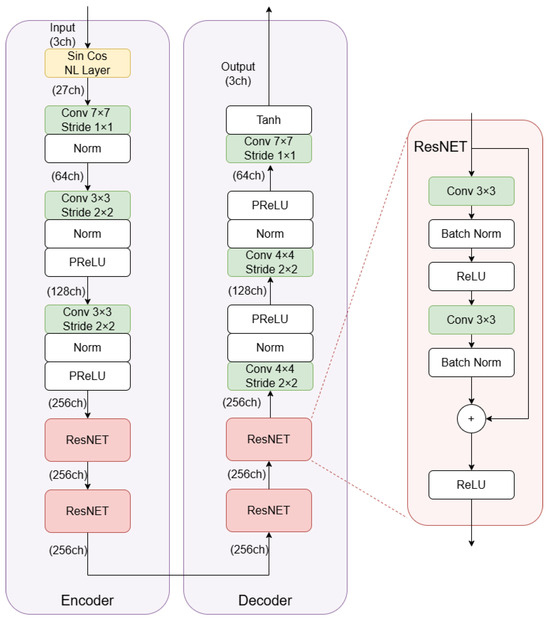

A detailed view of the NLCNet architecture is provided in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Encoder–decoder network structure of NLCNet.

3.1. The Encoder/Decoder Modules

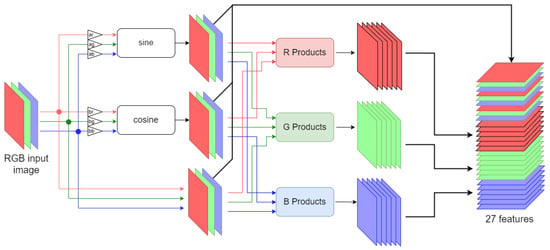

The first block of each encoder/decoder pair is the novel nonlinear convolution module that we propose in this paper (Figure 2). We discuss a simplified implementation adopted in this work. Its input, which is also the input of the complete network, is an image I of size with c colors channels, I ∈ , which is first transformed to a space composed by the original image data together with their channel-wise sine and cosine transforms. More precisely, each color component x of the image is multiplied by the factors and before applying the sine and cosine operators, respectively, such that the actual operations performed are and , with if the RGB color representation is used. The default value for such parameters is 1. Values in the space are further processed by computing all the possible products between the outputs of the sine/cosine functions and the pixels of the original image: , , etc., including also the quadratic terms , , , but without considering any cross-products between data obtained from different chromatic channels. In the most common case in which the image is composed of three channels, the sin-cos block outputs 27 features, which consist of the image itself (3 features, the R, G, B components), the sine and cosine functions applied to the chromatic channels (6 features, ), and the various cross products of all of them ( features, , , , , , , etc.). All these features (resumed in Table 1) can now be used to create an arbitrary number of tone-mapped functions of the original image’s R, G, B channels. Indeed, these can be considered as the basis for approximating any nonlinear function by using a suitable convolution operation. This operation however can be easily combined with the first layer of the CNN adopted in the encoder–decoder architecture. The nonlinear expanded data feed the subsequent layer, producing a stack of features having size . This is actually the first convolutional layer depicted in Figure 1. Such a layer adopts an core dimension to produce f different features (in Figure 1, ). For our application fields, experiments showed that the value of l can be varied in the range 7–11 depending upon the neighborhood size to be considered. For example, in a deraining task where large raindrops are present a 9–11 sized window proves to be more efficient compared to small 3–5 windows.

Figure 2.

Versatile input nonlinear layer. R Products denote rows 4–9 of column R in Table 1. Similarly, G and B Products depict 4–9 rows of column G and B, respectively.

Table 1.

Set of 24 nonlinear expanded features (8 per color channel) + 3 original ones (R,G,B).

The nonlinear expanded data feeds the encoder, which, through a succession of convolutional layers, normalizations, and nonlinearities, reduces the spatial dimensions of the data layer by layer, while increasing their depth in terms of the number of features. The decoder then does exactly the opposite, eventually producing an image that has the same dimensions as the original image. In the transition between the encoder and the decoder, four Residual blocks have also been placed, which are useful to directly process the deepest features.

3.2. Training the Overall Structure

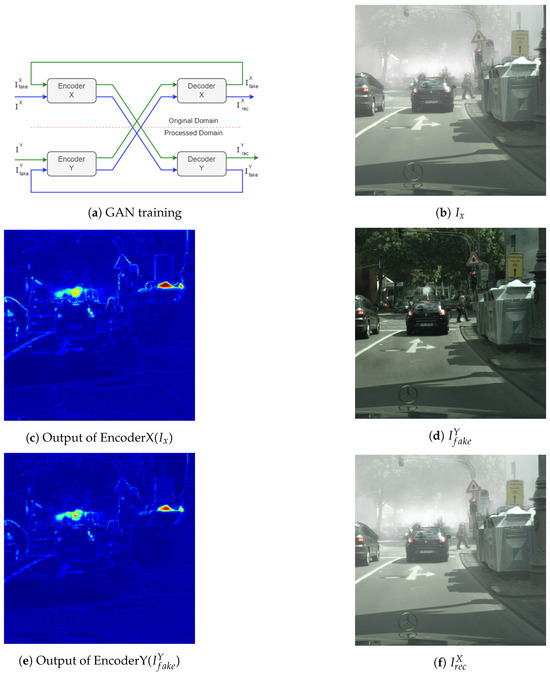

A cycle GAN as depicted in Figure 3 is used to train the model, where, in addition to a GAN loss, a cycle reconstruction loss is used. To minimize false structure generation during the unsupervised training process, a latent feature loss and a geometric consistency loss are used. A real image I in domain X is processed by encoder and decoder to generate a fake image in domain Y:

The cycle reconstruction loss is computed by processing to generate a fake image reconstruction in X domain, . This process is repeated, exchanging the domains to compute a second reconstruction loss :

The latent feature loss is computed from the encoders in both domains. This constraint ensures that both encoders learn only features from the images, regardless of the domain. Hence, the encoded features of from should be the same as encoded features . Losses are computed for both domains:

The geometric consistency loss is defined in Equations (7). It is composed of the sum of two contributions. The former is the L1 loss between the fake image and the rectified version obtained at the decoder output when a rotated version of the image is provided at the encoder input. This term is justified since a geometrically rotated image should generate the same rotated fake in the other domain independently of the considered domain, hence ensuring fake structures are not added during the image translation. The latter contribution is the semantic loss computed using features extracted from any other deep CNN like Alexnet or VGG.

Figure 3.

The figure illustrates the input and output at each step for a single path, as depicted in subfigures (b–f), corresponding to the blue path shown in subfigure (a).

Consequently, we consider

where is the rotated version of I and denotes the inverse of such rotating operation, while denotes the deep features extracted using the VGG network. The geometric consistency loss can be applied to the fake domain, as shown above. Alternatively, it is also feasible to apply it on the reconstructed domain, and . The GAN loss is an average obtained from three discriminators, which cover the color (Gaussian blurred color image to avoid fine features), edge (2 channel input with horizon and vertical gradients) and texture features (gray image input) individually.

4. Experimental Results and Discussion

In this section we demonstrate the performance of our network for different enhancement tasks. For each of the cases, we provide comparisons with benchmark State of the Art (SoA) techniques using visual results. All training dataset links can be found in the project repository: github.com/jhilikb/NLCUNet (https://github.com/jhilikb/NLCUNet/tree/main/, accessed on 17 December 2025). When ground truth data are not available, No-Reference Image Quality Assessment (NRIQA) tools are used, such as PIQE [32], NIQE [33], BRISQE [34].

The end application for all translation tasks is driving assistance systems or surveillance systems. The scope of the current work is to validate if the nonlinear convolution function added at the beginning of the network provides comparable results with a reduced number of layers. We report results for image quality analysis (visual and objective) after performing the respective task, i.e., dehazing, deraining, etc. Some object detection comparisons for rainy and hazy images are also provided, even if a detailed analysis is avoided due to space constraints. It should be noted that, although most of the literature on dehazing, deraining, and low-light enhancement relies on supervised training, we demonstrate the use of unsupervised training. Specifically, during training, a degraded sample and a clean sample from the respective degraded and clean distributions are selected randomly at each iteration. These samples are never the same image. We argue that generating real image pairs is difficult for hazy, rainy, low light or night-to-day scenarios. Although synthetic image generation is possible for the first three cases, generation of a synthetic night image given a day image requires the use of image generation networks (GANs).

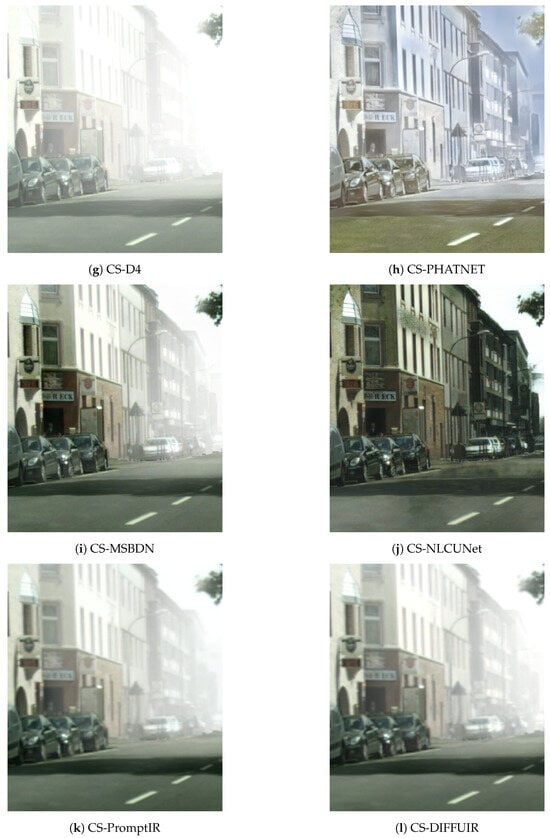

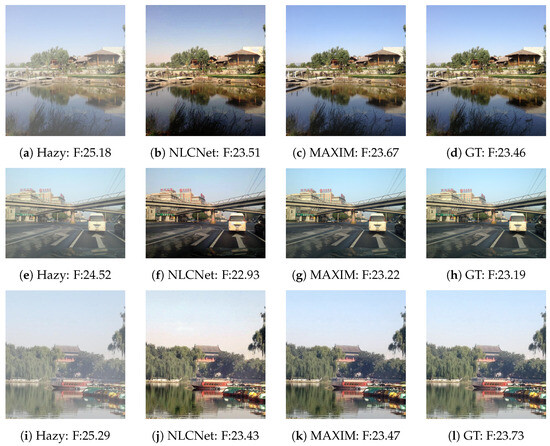

4.1. Dehazing

This subsection presents objective and visual analysis of dehazed images using our proposed method and benchmark methods. We used Cityscape-original (2950 images) and hazy (8850 images) [35,36], RESIDE: Real-world-Task-driven-testing-set (RESIDE) (2591 images) and RESIDE: Outdoor Training Set (OTS) (313,950 from V0), Synthetic Objective Testing Set (SOTS)-Outdoor (500 images) [37], Dawn-Haze (300 images). The hazy Cityscape is synthetically generated from the original images using attenuation coefficients 0.01, 0.02 and 0.005. Alternatively, 313,950 synthetic images of the OTS are also used for training for a fair comparison, as all SoA dehazing techniques use the same. The combination of the above datasets has been carefully designed to ensure that there are no superpositions among the training and testing sets in any application case or experiment. For example, we used a network trained with OTS while testing RESIDE and DawnHaze. We have used the SUN dataset with synthetic haze to show Cityscape results. The real-time hazy RESIDE images and Dawn hazy images are used for testing only. We provide PSNR and SSIM for the Cityscape dataset, while the NRIQA indices PIQE (P), NIQE (N), and BRISQUE (B), are used for the datasets without a ground truth. Lower values of P, N, and B indicate higher image quality. We provide the NRIQA results in Table 2 for dehazed images of the RESIDE dataset, Cityscape-Hazy dataset, and Dawn-Haze dataset using our proposed method NLCNet and fourteen other benchmark methods: AOD [38], MAXIM [2], Dehazeformer (DHF) [39], FFA [16], GCANet [15], MSBDN [40], ChaIR [17], PromptIR [26], FDTANET [19], CAPTNET [27], DIFFUIR [1], D4 [21], D4+ [22] and PHATNET [41]. We have included some older baselines along with the more recent prompt-based techniques to show that some of these older techniques actually provide better generalization on real datasets, even if their scores on synthetic datasets are much lower. We observe that for all three datasets, i.e., Cityscape, RESIDE, and Dawn-Haze, NLCNet has the lowest P, N, and B scores, indicating that our proposed method generates higher-quality images. It was also interesting to note (in Table 2) that PHATNET, which uses a haze transfer algorithm to learn the haze pattern of the target set before applying dehazing on unpaired datasets, performed comparatively well on the Cityscape dataset in terms of NRIQ. This is not very prominent on real images as learning real haze patterns is comparatively harder compared to synthetic ones. Figure 4 and Figure 5 and provide a visual result of a sample image from the Cityscapes dataset along with the quality scores. All original Cityscapes sample images used for visualization are provided in the project repository:github.com/jhilikb/NLCUNet (https://github.com/jhilikb/NLCUNet/tree/main/example, accessed on 17 December 2025). The annotated unprocessed hazy image highlights some areas for better clarity. The red annotation represents the region with missing data in the original image. It is seen that, other than DHF and NLCNet, no other networks are able to reconstruct the region. Also, the reconstruction with NLCNet is slightly better. The pink rectangle highlights the area that provides fair dehazing with all the networks. It is observed that the dehazing of this region is best for NLCNet. While MSBDN, FFA and GCANet provide average dehazing with visible shop boards, the diffusion and transformer architectures (MAXIM, DIFFUIR, PrompIR, CaptNet, FDTANet) provide worse dehazing with very poor resolution. Similarly, very little dehazing is obtained for the diffusion and transformer networks for the violet region. The green rectangle depicts the vanishing-point road region that is left as is by all networks, excluding DHF. It is seen that DHF tends to generate weird structures in far regions for most images. Overall, it can be stated that the objective image scores shown in Figure 4 reflect the overall scores of Table 2, giving an approximate idea about the obtained score quality. It is also noted that PHATNET is able to maintain the overall structure of the image with moderate luminance, hence generating good no-reference scores even if the reference score is poor due to the texture discrepancy in the far end of the image. This is dealt better by NLCUNet, which provides the best PSNR along with acceptable image quality. The PSNR and SSIM scores are provided in Table 3. The PSNR and SSIM values are seen to be considerably higher for NLCNet with the Cityscape dataset. MAXIM and DHF are seen to perform very well on SOTS-Outdoor (referred as SOTS-O) in terms of both PSNR and SSIM, even if they generalize poorly on Cityscapes, another synthetic haze dataset. It is already observed from Table 2 that the objective no-reference quality score for MAXIM for real datasets like Dawnhaze and RTTS (RESIDE) are very poor. The same is also observed later for other types of degradations like rainy. The PSNR score for NLCNet is slightly less than that of MAXIM and DHF for SOTS-O. Although NLCNet is almost one-third the size of MAXIM, we emphasize that, instead of the smaller size, the main reason for the drop in PSNR is the unsupervised training procedure. It should be noted that all other results reported use supervised training, unlike ours, and it is seen that the similarity in the type of images between the training (OTS) and testing (SOTS-O) dataset is very high. Table 3 lists the number of parameters for all the methods. The last row shows the same information for the proposed approach, NLCNet. As can be seen, some of the older methods have fewer parameters than NLCNet, but they perform significantly worse. Conversely, all methods—whether transformer- or diffusion-based—that achieve performance comparable to or approaching that of NLCNet are considerably more computationally demanding. It is observed, that the generated images using NLCNet (Figure 6) perform adequate dehazing, which, in fact, is the actual goal. The PSNR drop in case of SOTS-O is due to the color variations in the sky or other homogeneous regions and is not important for practical applications. We have provided Fog Aware Density Evaluator (FADE) scores, which particularly measure fog. Lower scores are obtained for clearer images. Figure 6 shows that both NLCNet and MAXIM have lower scores compared to the foggy image. In some cases, NLCNet even obtains a better (lower) score compared to MAXIM. In Table 4, we present the objective scores of SOTS-O using unsupervised training techniques D4, D4+, ODCR [42], UME-Net [23] and UR2P [24]. We notice that the performances of these are lower compared to supervised techniques. NLCNet infact provides a significant gain compared to other unpaired techniques. A further experiment is presented later, where we discuss object detection results of different SoA techniques along with their parameter sizes. This verifies whether the presented nonlinear convolution network without attention mechanisms and a reduced parameter set is capable of scene understanding tasks for poor visibility images. We observe that NLCNet in spite of having the minimum number of parameters is able to provide the maximum detection precision compared to other networks.

Table 2.

Hazy Images—NRIQA Results. Red, green, and blue colors denote the top 3 scores, respectively.

Figure 4.

Sample image from Cityscapes dataset enhanced with the proposed approach NLCNet (shown in (h)) and with other techniques. P,N,R denote the PIQE, NIQE and PSNR scores.

Figure 5.

Visualization of cropped sample of Figure 4, for the proposed approach NLCNet (shown in (h)) and other techniques.

Table 3.

PSNR and SSIM on Cityscape and SOTS-O) images along with model params (Par) in MB. Red, green, and blue colors, respectively, denote the top three scores.

Figure 6.

Sample images from SOTS-O dataset processed using different methods. F indicates the Fog Aware Density Evaluator (FADE) metrics.

Table 4.

PSNR and SSIM on SOTS-O images for unpaired training. Red denotes the top performance score.

We reiterate that training performed on synthetic image pairs often fails to generalize well to real images. A typical example is a dehazing network trained via a supervised technique using a synthetic outdoor dataset. In synthetic datasets, generated haze provides an overall whitening to the image. When this is used with supervised training, very high quality dehazed images are obtained. This ensures the high PSNR and SSIM values reported by the authors. However, when used on real hazy images, the network automatically assumes that it needs to remove the extra whitening effect. This results in dark processed images. This undesired effect is avoided by unsupervised techniques. Overall, we observe that NLCNet performs satisfactorily with respect to large diffusion and transformer architectures. Also, our baseline model reports slightly worse results when the NLC unit is replaced with different attention modules. It is further observed that NLCNet is able to generalize better compared to much larger diffusion models and prompt-based models. It should be noted that NLCNet never makes use of supervised training, even in cases where synthetic image pairs are available. Considering we ultimately focus on applying the network for real-time image processing in driving scenarios, we mostly carry out our tests on real hazy/rainy images to evaluate the output quality in a realistic context.

All results discussed so far particularly belong to day haze. In Table 5 we demonstrate the application of dehazing using the NHR dataset belonging to the synthetic nighthaze category. For fair comparison we used the same settings for computing PSNR and SSIM as reported in [43]. We used [44,45,46,47] for reporting the comparison results and observe that our model performs extremely well on NHR.

Table 5.

Objective comparisons of nighttime dehazing methods on NHR dataset. Red denotes the top performance score.

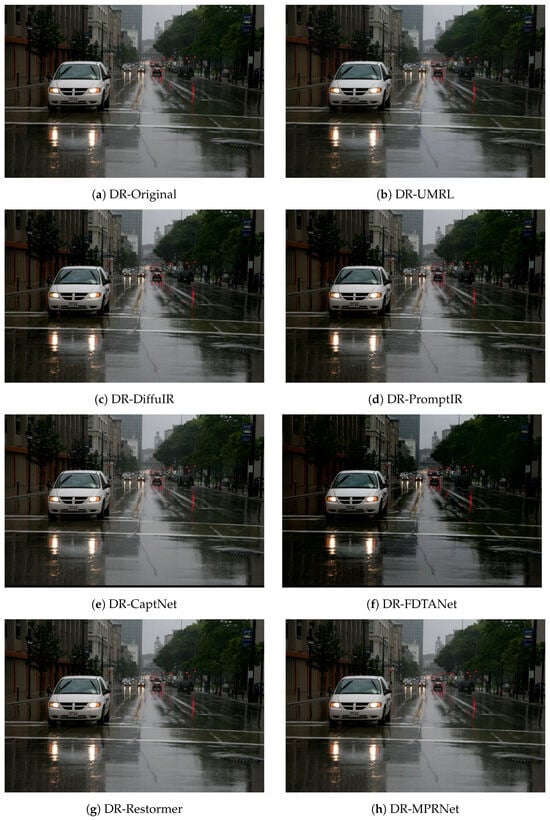

4.2. Deraining

The deraining task is trained with Raindrop (861 pairs) (for “pair” we mean two samples selected at random from the clean and degraded set, respectively; the scene shown by each sample in the pair is never the same) [48], as well as the Rain Image Dataset (SRID-12,000 images) [49,50], for comparing with SoA techniques. RIS (2285 images) [51] and the Dawn-Rain dataset (200 images) [52] are used for testing. The objective analysis of the enhanced rainy images using our proposed method NLCNet and twelve other benchmarks Deraindrop [48], DIDMDN [53], Restormer [12], MAXIM [2], MPRNet [13], MSPFN [54], PRENet [55], M3SNet [56], UMRL [57], PromptIR [26], FDTANET [19], CAPTNET [27], and DIFFUIR [1] are presented. We calculated P, N, and B scores for all the processed images and reported the resulting scores in Table 6. Among all the methods, the NLCNet method resulted in the lowest score for the RIS and Dawn-Rain datasets, showing that the resulting images are of better quality. The images generally show better clarity avoiding dark regions (as also observed in Figure 7), smoothing raindrops without extra blurring. PromptIR, FDTANet, PRENet, and DIDMDN show a darker effect in that area. Some sample images are shown in Figure 7.

Table 6.

Rainy images—NRIQA results. Red, green, and blue colors, respectively, denote the top three scores.

Figure 7.

Deraining sample images. The best clarity in the top-right region (below the tree) is obtained using NLCNet. PromptIR, FDTANet, PRENet, and DIDMDN show a darker effect in that area.

Along with visual results and objective quality measurements, we also show how the SoA technique performs for object detection tasks. Table 7 presents the object detection results obtained with SpineNet96 when applied to the enhanced images in each case. Cityscapes, RESIDE and DawnHaze are used for generating detection mAP for dehazed images while RIS, RID and DawnRain are used for computing mAP from derained images. This highlights that despite being the smallest network, NLCNet provides the best average object detection scores on both Rainy as well as Hazy datasets. The network can thus be an optimal choice for automated detection and surveillance tasks.

Table 7.

Object detection performance and parameter count of different networks trained for multiple tasks. The best score is marked in red.

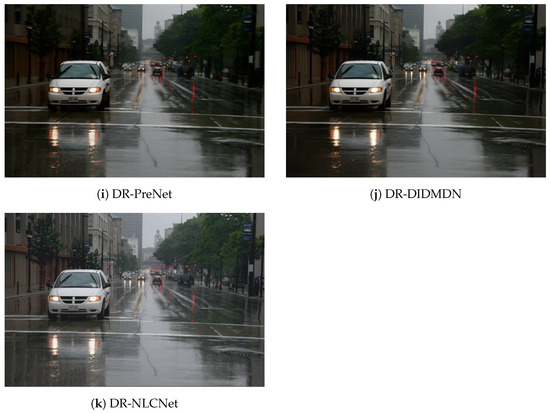

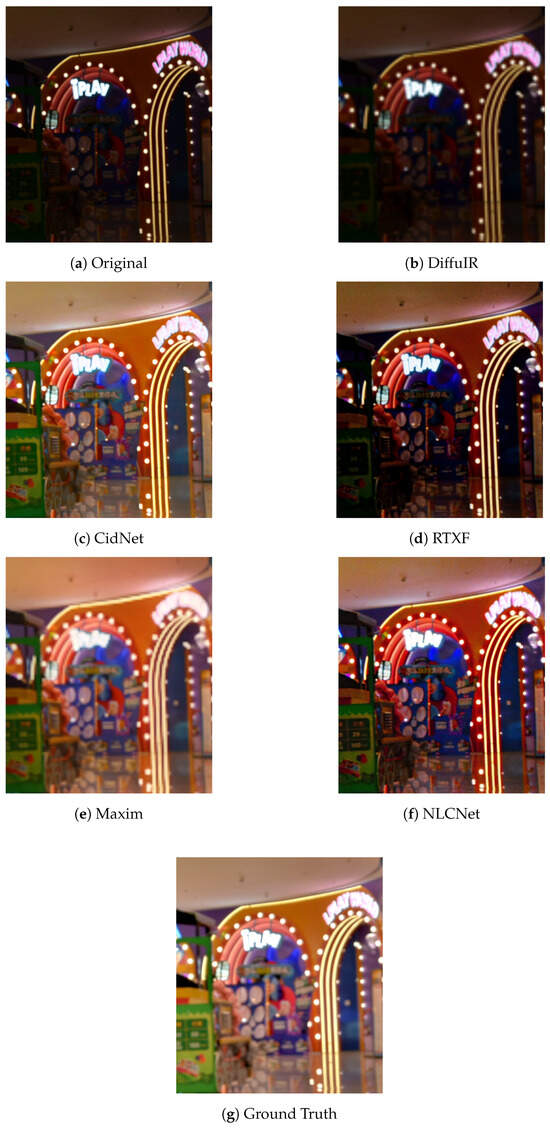

4.3. Dark to Bright

We train the network with selected images from the Adobe dataset (2k pairs). Evaluation results are shown on the DPAIR (LOL) in Table 8, NITRE [58] as well as Berkeley Driving Dataset (BDD) [59]. Previously in [31] it was shown that the unsupervised technique gives the best PSNR and SSIM scores on DPAIR compared to other benchmarks. In this work, we demonstrate that the network provides far better scores even with half the number of blocks, once we add the nonlinearity at the beginning of the network.

Table 8.

PSNR and SSIM on LOL and NTIRE. Red, green, and blue colors, respectively, denote the top three scores.

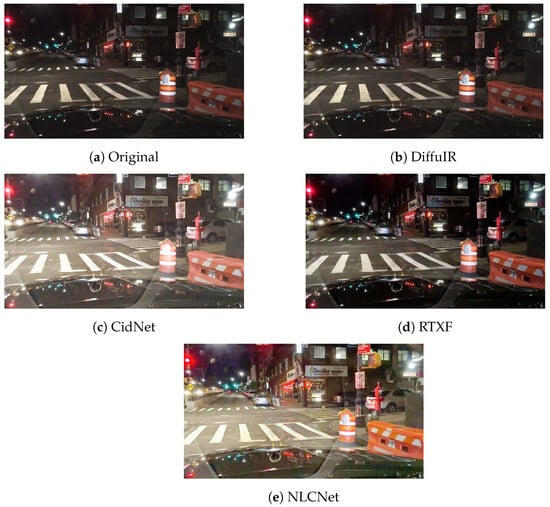

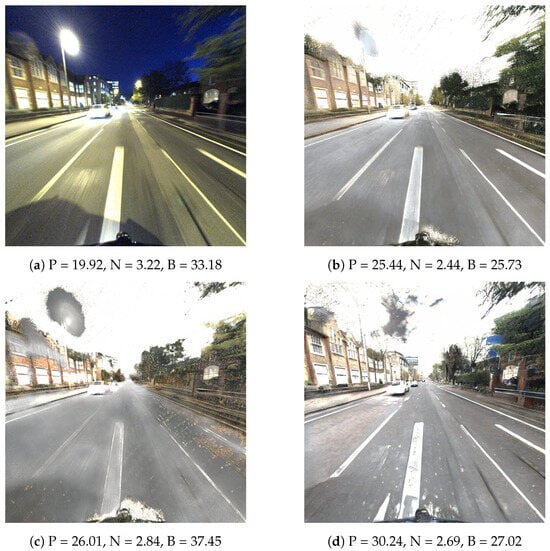

It is observed that DiffuIR obtains a much higher SSIM compared to the other top two techniques: Maxim and NLCNet. To verify the generalizability of the different top performing networks, we perform another experiment where we use the NITRE 2025 low light challenge dataset for testing with the pretrained networks. It is observed (Table 8) that both DiffuIR and RetinexFormer (RTXF) [60] provide very poor images. Comparatively, Maxim, Cidnet [61] and NLCNet are able to generate better enhancements. Overall, NLCNet maintains a higher average PSNR and SSIM on different datasets. For further clarity, we show some visual results from the NITRE and BDD datasets in Figure 8 and Figure 9. DiffuIR shows no improvement in the images in both cases, while RTXF shows minor changes in illumination. While Maxim, CidNet and NLCNet shows considerable changes in illumination, Maxim generates poor resolution (as better observed from the zoomed versions here (https://github.com/jhilikb/NLCUNet/tree/main/examplell, accessed on 17 December 2025)). CidNet provides a more uniform illumination in the case of NITRE while both CIDNet and NLCNet provide similar results in the case of BDD.

Figure 8.

Sample image from NITRE 2025 Challenge.

Figure 9.

Sample images from the BDD dataset.

4.4. Night to Day

The Robocar dataset (7796 pairs) [30], which consists of unpaired day and night images captured from a moving car, is used to demonstrate the night to day translation using the network. It can be observed from Figure 10 that the night images are quite noisy and blurry; hence, the day images depict noise and blur too. However, the results show that acceptable quality day images are generated using the proposed network. The main objective of generating day images from their night counterparts is to check the possibility of performance improvement for object detection tasks or scene localization tasks in the day images compared to the night ones. There are two main reasons for this: first, the night images may be too poor for any understanding task; second, the scene localization model may have been developed using day images. As the main goal of the current work is to demonstrate the capability of the newly introduced nonlinear network for different image translation tasks with a lower number of layers, we currently use only visual results along with NRIQA scores of night to day conversions and leave the comparisons for scene localization performances out of this scope. Visual results and NRIQA scores for GCGAN [62] and ToDAYGAN [30] are also shown as a baseline to represent how similar works, reported in the literature, perform.

Figure 10.

Night-to-day images from the Robocar dataset. (a–d) denote the night image and day images generated using NLCNet, GCGAN, and ToDayGAN, respectively.

Although night to day translation networks are not widely available in the literature, a more recent contribution includes TurboGAN [63]. The network is trained with BDD images and performs a good job in generating a day image, given a night BDD image. However, it was surprising to note that the network does not provide any results when used on other images. Given a night image from the Robocar dataset, it generated the same night image as output. The same is not true for networks like TodayGAN or GCGAN. It should be noted that the color distributions of BDD and Robocar are very different; hence, given a BDD image, a ToDAYGAN model trained with the Robocar dataset generates a poor quality image, but nevertheless a day image. In order to compare results with TurboGAN, we trained our NLCNet with BDD (10K day and night). We use the metrics FID and DINO reported in TurboGAN to observe our network performance. FID provides a measure of how similar the color distribution of generated images are, when compared to the day images used for training. DINO measures the consistency in the structure of the images (the original night and the generated day). We expect a low FID and DINO score. We observe that the structures of generated day images are well preserved in NLCNet, in fact, even better than TurboGAN (Table 9). However, the color quality of the images can be improved. It is observed that a NLCNet with more layers (denoted as ) is capable of generating better color distribution. The results for shown in Table 9 are obtained using nine residual blocks instead of four used in NLCNet.

Table 9.

FID and DINO structural scores on BDD night to day images. The top score is marked in red.

5. Ablation and Other Experiments

In this section, we discuss various ablation-like experiments to depict the impact of the nonlinear module (Table 10), different types of coefficient usages in the module (Table 11) and various loss functions (Table 12). We used the Raindrop dataset for presenting the results in terms of PSNR and SSIM scores in Table 10. The base network EnDec without any nonlinear module and nine residual blocks is trained using the dataset. The same network with only four residual blocks (without the nonlinear module), , shows lower performance. NLCNet outperforms its simplified versions, confirming that the nonlinear module improves performance even when the network size is reduced by half. In another experiment, we verify that using the polynomial Fourier basis, the network converges with fewer parameters. To demonstrate this we train a EnDec with 15 blocks without using any polynomial Fourier basis. We use EnDec with 15 blocks to test the attention modules. denotes a 15-block EnDec with channel attention in 9 blocks. has spatial attention in 9 blocks, while has channel and spatial attention in 9 blocks. The results are shown in Table 13. It should be noted that our EnDec with the NLC module has a total 10 blocks. It is observed that the EnDec with NLC block, i.e., NLCNet, obtains better performance with less than half the number of parameters. We have also tested further compression of our network (5.83 M params with 42.7 G FLOPS) to evaluate the rate in which the performance drops. We have used NHR dataset and tested PSNR and SSIM for lowlight images for low to bright task. We observe that we obtain a PSNR and SSIM of and , respectively, (this is same upto the second decimal place in the original network) when we reduce our network to parameters with FLOPS. A PSNR and SSIM of and , respectively, is obtained with parameters with FLOPS. These initial experiments indicate that the network can be compressed to a much smaller size without significant loss in performance.

Table 10.

Results with different amounts of residual blocks and with and without the nonlinear block. Boldface indicates best result.

Table 11.

Results with several variants of the Nonlinear Block (see text). Boldface indicates best result.

Table 12.

PSNR and SSIM of Cityscapes images when using different loss functions for training NLCNet. Boldface indicates best result.

Table 13.

PSNR and SSIM on SOTS-O images with and without attention modules. Boldface indicates best result.

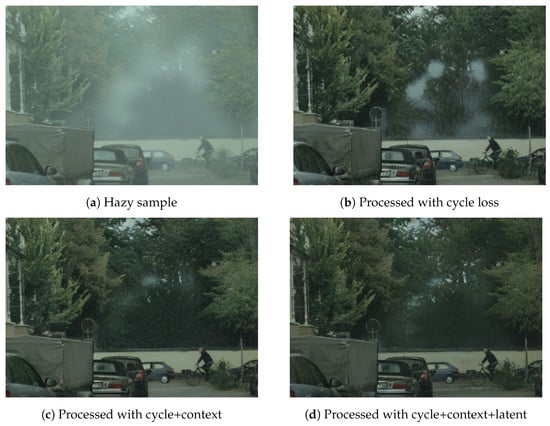

We further show the impact of using different loss functions in Table 12. It is seen that a significant gain in SSIM is obtained when latent and contextual loss is added to the basic cycle loss. This is also verified from the sample image shown in Figure 11.

Figure 11.

Sample zoomed image with networks trained with different loss function.

In another set of experiments, we consider the nonlinear block based on the sine–cosine transformation. We use an input range of to 1 for the RGB images; scaling this range by and introduces strong nonlinearity while preserving stable gradients. This is the most theoretically optimal choice, as confirmed by our experiments. We could choose different fixed values for the coefficients and . We explored various possibilities, but two are the most significant: i. , which is the simplest possible solution (denoted as V1); ii. and , as in the Fourier nonlinear filters of [6] mentioned in the Introduction (denoted as V2). We could use only cosine coefficients in both (i) and (ii) since the sine function behaves similarly to the linear term, which is already included in the network. This generates V3 and V4, respectively. Learning the coefficients a in the transformation depends heavily on the initialization and is theoretically unstable: a small a may result in an underscaled, nearly linear representation, while a larger a can lead to noisy outputs. This behavior is not the same as learning . We verified this by learning the coefficients and during training to optimize their values (denoted as V5). To generalize even further, these coefficients could be replaced with a linear layer applied before the sine and cosine terms (V6). V6 is the most general network, since the coefficients a and b are replaced by a learnt transformation matrix that introduces further degrees of freedom. We evaluate the use of different coefficient types in the nonlinear layer and their impact on PSNR and SSIM performance on the DPAIR dataset (Table 11). Unlike the other reported results, which use the format, all values in this table are computed with floating-point images. Optimal outcomes are achieved by V1 and V2. V2 excels in terms of PSNR, while V1 excels with SSIM, albeit the difference from V2 is marginal. Specifically, V1 introduces a lower degree of nonlinear expansion compared to V2, suggesting the advantageous nature of the full nonlinear expansion provided by V2. Analysis on V3 and V4 shows that cosine terms play a crucial role in ensuring optimal network performance, although their significance is slightly lower than that of sine terms. Although there is a slight decrease in performance with V2 and V3 compared to V1 and V2, respectively, this reduction is significantly less compared to utilizing solely linear terms. As expected, in practice, the incorporation of an additional layer formed by coefficients in V5, and a complete linear layer in V6, leads to inferior performance, suggesting the network’s struggle to adapt these linear terms preceding the sine/cosine nonlinearities. This is because a very small coefficient value compresses the input range, leading to weaker gradients and making it difficult for the network to converge. Although the results vary with different network initializations, using coefficients in the ranges for the sine terms and for the cosine terms appears to yield the best performance.

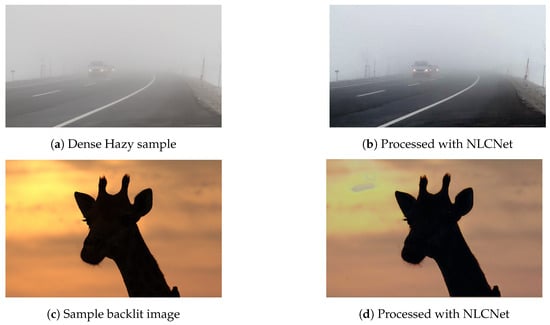

Limitations

All the translation tasks discussed in this paper are critical for scene understanding in autonomous vehicles. Achieving reliable enhancement under dense haze, low-light, and backlit conditions, so that downstream detection performs well, remains challenging. Although we demonstrate improvements in object detection for real hazy scenes, performance could likely be further increased by incorporating physical priors. Our network also does not perform well on backlit images, as can be seen from the images in Figure 12.

Figure 12.

Sample images for dense haze and backlit conditions, which can be improved.

Another important aspect is the network’s compression capability. We observed that dehazing, deraining, and low-light enhancement tasks can still perform effectively even with a significantly smaller network (Table 10 and Table 13). However, the same level of compression is not achievable for the night-to-day task due to the complexity of the underlying mapping (Table 9). It is also worth investigating whether similar reductions in model size could be applied to other diffusion-based or larger transformer architectures when using a polynomial Fourier basis.

6. Conclusions

We have proposed a novel sine/cosine-based input module that executes a nonlinear convolution of the source data, enabling the designer to reduce the depth of the subsequent CNN without compromising the quality of the results. We demonstrated that such a network, when trained using an unsupervised training technique, can generalize better on different tasks, outperforming diffusion and attention-based models. Future work will be devoted to demonstrating the effects of placing the nonlinear layer at different depths of the network.

Author Contributions

Conceptualization, A.C.; methodology, J.B., A.C., S.M. and G.R.; software, J.B.; formal analysis, J.B. and S.M.; investigation, J.B.; writing—original draft preparation, J.B., A.C., S.M. and G.R.; funding acquisition, J.B. and G.R. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This research was supported in part by Department of Science and Technology, Ministry of Science and Technology, India & by Ministero degli Affari Esteri (MAE), Italy (INT/Italy/P-33/2022(ER)).

Data Availability Statement

All data used in the research are publicly available. It can also be found at https://github.com/jhilikb/NLCUNet/tree/main/, accessed on 17 December 2025.

Acknowledgments

A.C., S.M. and G.R. gratefully acknowledge the support of the University of Trieste.

Conflicts of Interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest. The funders had no role in the design of the study; in the collection, analyses, or interpretation of data; in the writing of the manuscript, or in the decision to publish the results.

References

- Zheng, D.; Wu, X.M.; Yang, S.; Zhang, J.; Hu, J.F.; Zheng, W.S. Selective Hourglass Mapping for Universal Image Restoration Based on Diffusion Model. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 25445–25455. [Google Scholar]

- Tu, Z.; Talebi, H.; Zhang, H.; Yang, F.; Milanfar, P.; Bovik, A.; Li, Y. Maxim: Multi-axis MLP for image processing. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 5769–5780. [Google Scholar]

- Hornik, K.; Stinchcombe, M.; White, H. Multilayer feedforward networks are universal approximators. Neural Netw. 1989, 2, 359–366. [Google Scholar]

- Pao, Y. Adaptive Pattern Recognition and Neural Networks; Addison-Wesley Publishing Co., Inc.: Reading, MA, USA, 1989. [Google Scholar]

- Mathews, V.J.; Sicuranza, G.L. Polynomial Signal Processing; Wiley: New York, NY, USA, 2000. [Google Scholar]

- Carini, A.; Sicuranza, G.L. Fourier nonlinear filters. Signal Process. 2014, 94, 183–194. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lapedes, A.; Farber, R. Nonlinear Signal Processing Using Neural Networks: Prediction and System Modelling; Technical Report; Los Alamos National Laboratory: Los Alamos, NM, USA, 1987. [Google Scholar]

- Sopena, J.M.; Romero, E.; Alquezar, R. Neural networks with periodic and monotonic activation functions: A comparative study in classification problems. In Proceedings of the 1999 Ninth International Conference on Artificial Neural Networks ICANN 99, Edinburgh, UK, 7–10 September 1999. [Google Scholar]

- Gashler, M.S.; Ashmore, S.C. Modeling time series data with deep Fourier neural networks. Neurocomputing 2016, 188, 3–11. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Jagtap, A.D.; Shin, Y.; Kawaguchi, K.; Karniadakis, G.E. Deep Kronecker neural networks: A general framework for neural networks with adaptive activation functions. Neurocomputing 2022, 468, 165–180. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rafajłowicz, E.; Pawlak, M. On function recovery by neural networks based on orthogonal expansions. Nonlinear Anal. Theory Methods Appl. 1997, 30, 1343–1354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zamir, S.W.; Arora, A.; Khan, S.; Hayat, M.; Khan, F.S.; Yang, M.H. Restormer: Efficient transformer for high-resolution image restoration. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 5728–5739. [Google Scholar]

- Zamir, S.W.; Arora, A.; Khan, S.; Hayat, M.; Khan, F.S.; Yang, M.H.; Shao, L. Multi-stage progressive image restoration. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Nashville, TN, USA, 20–25 June 2021; pp. 14821–14831. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Cun, X.; Bao, J.; Zhou, W.; Liu, J.; Li, H. Uformer: A General U-Shaped Transformer for Image Restoration. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recogn. (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 17683–17693. [Google Scholar]

- Chen, D.; He, M.; Fan, Q.; Liao, J.; Zhang, L.; Hou, D.; Yuan, L.; Hua, G. Gated context aggregation network for image dehazing and deraining. In Proceedings of the 2019 IEEE Winter Conference on Applications of Computer Vision (WACV), Waikoloa Village, HI, USA, 7–11 January 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA 2019; pp. 1375–1383. [Google Scholar]

- Qin, X.; Wang, Z.; Bai, Y.; Xie, X.; Jia, H. FFA-Net: Feature fusion attention network for single image dehazing. In Proceedings of the AAAI Conference on Artificial Intelligence, New York, NY, USA, 7–12 February 2020; Volume 34, pp. 11908–11915. [Google Scholar]

- Cui, Y.; Knoll, A. Exploring the potential of channel interactions for image restoration. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2023, 282, 111156. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dwivedi, P.; Chakraborty, S. FrTrGAN: Single image dehazing using the frequency component of transmission maps in the generative adversarial network. Comput. Vis. Image Underst. 2025, 255, 104336. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gao, H.; Ma, B.; Zhang, Y.; Yang, J.; Yang, J.; Dang, D. Frequency domain task-adaptive network for restoring images with combined degradations. Pattern Recognit. 2025, 158, 111057. [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, S.; Zhang, X.; Shen, L.; Wan, S.; Ren, W. Wavelet-based physically guided normalization network for real-time traffic dehazing. Pattern Recognit. 2026, 172, 112451. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, C.; Liu, R.; Zhang, L.; Guo, X.; Tao, D. Self-Augmented Unpaired Image Dehazing via Density and Depth Decomposition. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), New Orleans, LA, USA, 18–24 June 2022; pp. 2037–2046. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, Y.; Wang, C.; Guo, X.; Tao, D. Robust Unpaired Image Dehazing via Density and Depth Decomposition. Int. J. Comput. Vis. 2024, 132, 1557–1577. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sun, H.; Luo, Z.; Ren, D.; Du, B.; Chang, L.; Wan, J. Unsupervised Multi-Branch Network with High-Frequency Enhancement for Image Dehazing. Pattern Recognit. 2024, 156, 110763. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xue, M.; Fan, S.; Palaiahnakote, S.; Zhou, M. UR2P-Dehaze: Learning a Simple Image Dehaze Enhancer via Unpaired Rich Physical Prior. Pattern Recognit. 2026, 170, 111997. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lan, Y.; Cui, Z.; Luo, X.; Liu, C.; Wang, N.; Zhang, M.; Su, Y.; Liu, D. When Schrödinger Bridge Meets Real-World Image Dehazing with Unpaired Training. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Honolulu, HI, USA, 19–23 October 2025; pp. 8756–8765. [Google Scholar]

- Potlapalli, V.; Zamir, S.W.; Khan, S.; Khan, F.S. PromptIR: Prompting for All-in-One Blind Image Restoration. In Proceedings of the 37th International Conference on Neural Information Processing Systems, New Orleans, LA, USA, 10–16 December 2023; Volume 36. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, H.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, N.; Yang, J.; Dang, D. Prompt-based Ingredient-Oriented All-in-One Image Restoration. IEEE Trans. Circuits Syst. Video Technol. 2024, 34, 9458–9471. [Google Scholar]

- Sitzmann, V.; Martel, J.N.P.; Bergman, A.W.; Lindell, D.B.; Wetzstein, G. Implicit Neural Representations with Periodic Activation Functions; Curran Associates Inc.: Red Hook, NY, USA, 2020; NIPS ’20. [Google Scholar]

- Ranjan, P.; Khan, P.; Kumar, S.; Das, S.K. log-Sigmoid Activation-Based Long Short-Term Memory for Time-Series Data Classification. IEEE Trans. Artif. Intell. 2024, 5, 672–683. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Anoosheh, A.; Sattler, T.; Timofte, R.; Pollefeys, M.; Van Gool, L. Night-to-day image translation for retrieval-based localization. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Robotics and Automation (ICRA), Montreal, QC, Canada, 20–24 May 2019; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2019; pp. 5958–5964. [Google Scholar]

- Bhattacharya, J.; Modi, S.; Gregorat, L.; Ramponi, G. D2BGAN: A Dark to Bright Image Conversion Model for Quality Enhancement and Analysis Tasks Without Paired Supervision. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 57942–57961. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Venkatanath, N.; Praneeth, D.; Bh, M.C.; Channappayya, S.S.; Medasani, S.S. Blind image quality evaluation using perception based features. In Proceedings of the 2015 21st National Conference on Communications (NCC), Mumbai, India, 27 February–1 March 2015; IEEE: New York, NY, USA, 2015; pp. 1–6. [Google Scholar]

- Mittal, A.; Soundararajan, R.; Bovik, A.C. Making a “completely blind” image quality analyzer. IEEE Signal Process. Lett. 2012, 20, 209–212. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Mittal, A.; Moorthy, A.K.; Bovik, A.C. No-reference image quality assessment in the spatial domain. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2012, 21, 4695–4708. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cordts, M.; Omran, M.; Ramos, S.; Rehfeld, T.; Enzweiler, M.; Benenson, R.; Franke, U.; Roth, S.; Schiele, B. The cityscapes dataset for semantic urban scene understanding. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Las Vegas, NV, USA, 27–30 June 2016; pp. 3213–3223. [Google Scholar]

- Sakaridis, C.; Dai, D.; Hecker, S.; Van Gool, L. Model Adaptation with Synthetic and Real Data for Semantic Dense Foggy Scene Understanding. In Proceedings of the European Conference on Computer Vision (ECCV), Munich, Germany, 8–14 September 2018; pp. 707–724. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Ren, W.; Fu, D.; Tao, D.; Feng, D.; Zeng, W.; Wang, Z. Reside: A benchmark for single image dehazing. arXiv 2017, arXiv:1712.04143. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B.; Peng, X.; Wang, Z.; Xu, J.; Feng, D. Aod-net: All-in-one dehazing network. In Proceedings of the IEEE International Conference on Computer Vision, Venice, Italy, 22–29 October 2017; pp. 4770–4778. [Google Scholar]

- Song, Y.; He, Z.; Qian, H.; Du, X. Vision transformers for single image dehazing. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2023, 32, 1927–1941. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dong, H.; Pan, J.; Xiang, L.; Hu, Z.; Zhang, X.; Wang, F.; Yang, M.H. Multi-scale boosted dehazing network with dense feature fusion. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 2157–2167. [Google Scholar]

- Tsai, F.J.; Peng, Y.T.; Lin, Y.Y.; Lin, C.W. PHATNet: A Physics-guided Haze Transfer Network for Domain-adaptive Real-world Image Dehazing. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Honolulu, HI, USA, 19–25 October 2025; pp. 5591–5600. [Google Scholar]

- Wang, Z.; Zhao, H.; Peng, J.; Yao, L.; Zhao, K. ODCR: Orthogonal Decoupling Contrastive Regularization for Unpaired Image Dehazing. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 25479–25489. [Google Scholar]

- Liu, Y.; Wang, X.; Hu, E.; Wang, A.; Shiri, B.; Lin, W. VNDHR: Variational Single Nighttime Image Dehazing for Enhancing Visibility in Intelligent Transportation Systems via Hybrid Regularization. IEEE Trans. Intell. Transp. Syst. 2025, 26, 10189–10203. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cong, X.; Gui, J.; Zhang, J.; Hou, J.; Shen, H. A Semi-Supervised Nighttime Dehazing Baseline with Spatial-Frequency Aware and Realistic Brightness Constraint. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 16–22 June 2024; pp. 2631–2640. [Google Scholar]

- Jin, Y.; Lin, B.; Yan, W.; Yuan, Y.; Ye, W.; Tan, R.T. Enhancing Visibility in Nighttime Haze Images Using Guided APSF and Gradient Adaptive Convolution. In Proceedings of the 31st ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Ottawa, ON, Canada, 29 October–3 November 2023; pp. 2446–2457. [Google Scholar]

- Yang, C.H.; Lin, Y.H.; Lu, Y.C. A Variation-Based Nighttime Image Dehazing Flow with a Physically Valid Illumination Estimator and a Luminance-Guided Coloring Model. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 50153–50166. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, J.; Cao, Y.; Zha, Z.J.; Tao, D. Nighttime Dehazing with a Synthetic Benchmark. In Proceedings of the 28th ACM International Conference on Multimedia, Seattle, WA, USA, 12–16 October 2020; pp. 2355–2363. [Google Scholar]

- Qian, R.; Tan, R.T.; Yang, W.; Su, J.; Liu, J. Attentive generative adversarial network for raindrop removal from a single image. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 2482–2491. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, X.; Huang, J.; Zeng, D.; Huang, Y.; Ding, X.; Paisley, J. Removing rain from single images via a deep detail network. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Honolulu, HI, USA, 21–26 July 2017; pp. 3855–3863. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, X.; Huang, J.; Ding, X.; Liao, Y.; Paisley, J. Clearing the skies: A deep network architecture for single-image rain removal. IEEE Trans. Image Process. 2017, 26, 2944–2956. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, S.; Araujo, I.B.; Ren, W.; Wang, Z.; Tokuda, E.K.; Junior, R.H.; Cesar-Junior, R.; Zhang, J.; Guo, X.; Cao, X. Single image deraining: A comprehensive benchmark analysis. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June2019; pp. 3838–3847. [Google Scholar]

- Kenk, M.A.; Hassaballah, M. DAWN: Vehicle detection in adverse weather nature dataset. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2008.05402. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, H.; Patel, V.M. Density-aware single image de-raining using a multi-stream dense network. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Salt Lake City, UT, USA, 18–23 June 2018; pp. 695–704. [Google Scholar]

- Jiang, K.; Wang, Z.; Yi, P.; Chen, C.; Huang, B.; Luo, Y.; Ma, J.; Jiang, J. Multi-scale progressive fusion network for single image deraining. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Seattle, WA, USA, 13–19 June 2020; pp. 8346–8355. [Google Scholar]

- Ren, D.; Zuo, W.; Hu, Q.; Zhu, P.; Meng, D. Progressive image deraining networks: A better and simpler baseline. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 3937–3946. [Google Scholar]

- Gao, H.; Yang, J.; Zhang, Y.; Wang, N.; Yang, J.; Dang, D. A novel single-stage network for accurate image restoration. Vis. Comput. 2024, 40, 7385–7398. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yasarla, R.; Patel, V.M. Uncertainty guided multi-scale residual learning-using a cycle spinning cnn for single image de-raining. In Proceedings of the IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 8405–8414. [Google Scholar]

- Pavao, A.; Guyon, I.; Letournel, A.C.; Tran, D.T.; Baro, X.; Escalante, H.J.; Escalera, S.; Thomas, T.; Xu, Z. CodaLab Competitions: An Open Source Platform to Organize Scientific Challenges. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2023, 24, 9525–9530. [Google Scholar]

- Yu, F.; Chen, H.; Wang, X.; Xian, W.; Chen, Y.; Liu, F.; Madhavan, V.; Darrell, T. BDD100K: A Diverse Driving Dataset for Heterogeneous Multitask Learning. In Proceedings of the 2020 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Seattle, WA, USA, 12–19 June 2020; pp. 2633–2642. [Google Scholar]

- Cai, Y.; Bian, H.; Lin, J.; Wang, H.; Timofte, R.; Zhang, Y. Retinexformer: One-stage Retinex-based Transformer for Low-light Image Enhancement. In Proceedings of the 2023 IEEE/CVF International Conference on Computer Vision (ICCV), Paris, France, 1–6 October 2023. [Google Scholar]

- Yan, Q.; Feng, Y.; Zhang, C.; Pang, G.; Shi, K.; Wu, P.; Dong, W.; Sun, J.; Zhang, Y. HVI: A New Color Space for Low-light Image Enhancement. In Proceedings of the 2025 IEEE/CVF Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition (CVPR), Nashville, TN, USA, 10–17 June 2025; pp. 5678–5687. [Google Scholar]

- Fu, H.; Gong, M.; Wang, C.; Batmanghelich, K.; Zhang, K.; Tao, D. Geometry-consistent generative adversarial networks for one-sided unsupervised domain mapping. In Proceedings of the IEEE Conference on Computer Vision and Pattern Recognition, Long Beach, CA, USA, 15–20 June 2019; pp. 2427–2436. [Google Scholar]

- Parmar, G.; Park, T.; Narasimhan, S.; Zhu, J.Y. One-Step Image Translation with Text-to-Image Models. arXiv 2024, arXiv:2403.12036. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.