Group Counterfactual Explanations: A Use Case to Support Students at Risk of Dropping Out in Online Education

Abstract

1. Introduction

- RQ1: Is it feasible to generate successful group counterfactuals for the problem of recovering students at risk of failing in a reasonable time?

- RQ2: What is the performance of group counterfactual explanations compared to individual counterfactuals according to standard indicators in this problem?

2. Background

2.1. Counterfactual Explanations

2.2. Counterfactuals in Education

2.3. Group Counterfactuals

- Identification of key features: For each instance, multiple individual counterfactual explanations are generated using DiCE. They then analyze the differences in features that produce the classification change in these individual counterfactuals, identifying those features that are most effective in altering the model’s prediction. These features are candidates for inclusion in the group counterfactuals.

- Sampling of feature values: Once the key features have been identified, values for these features are sampled from data points in the counterfactual class. These sampled values are more likely to generate valid counterfactual transformations, as they come from real data points.

- Counterfactual candidate generation: Key feature values, obtained from sampling in the counter class, are substituted into the original instances to generate candidate counterfactuals for the group. These modifications are counterfactual transformations that could potentially change the classification of the entire group.

- Selection of the best explanation: Finally, the feature value substitutions in the candidate counterfactuals are evaluated for validity and coverage. Validity refers to whether changes in features effectively alter the classification of instances to the opposite class, while coverage assesses whether this change applies to all instances in the group. The counterfactual with the highest coverage is selected as the best explanation for the group.

- (a)

- The criteria used to define potential groups of individuals for which a group counterfactual can be built;

- (b)

- The assignment of individuals from a whole population into groups by means of a clustering process;

- (c)

- The selection of the main features to be modified in the group counterfactuals;

- (d)

- The efficient selection of individuals to be used to build the group counterfactual for each group.

3. Materials and Methods

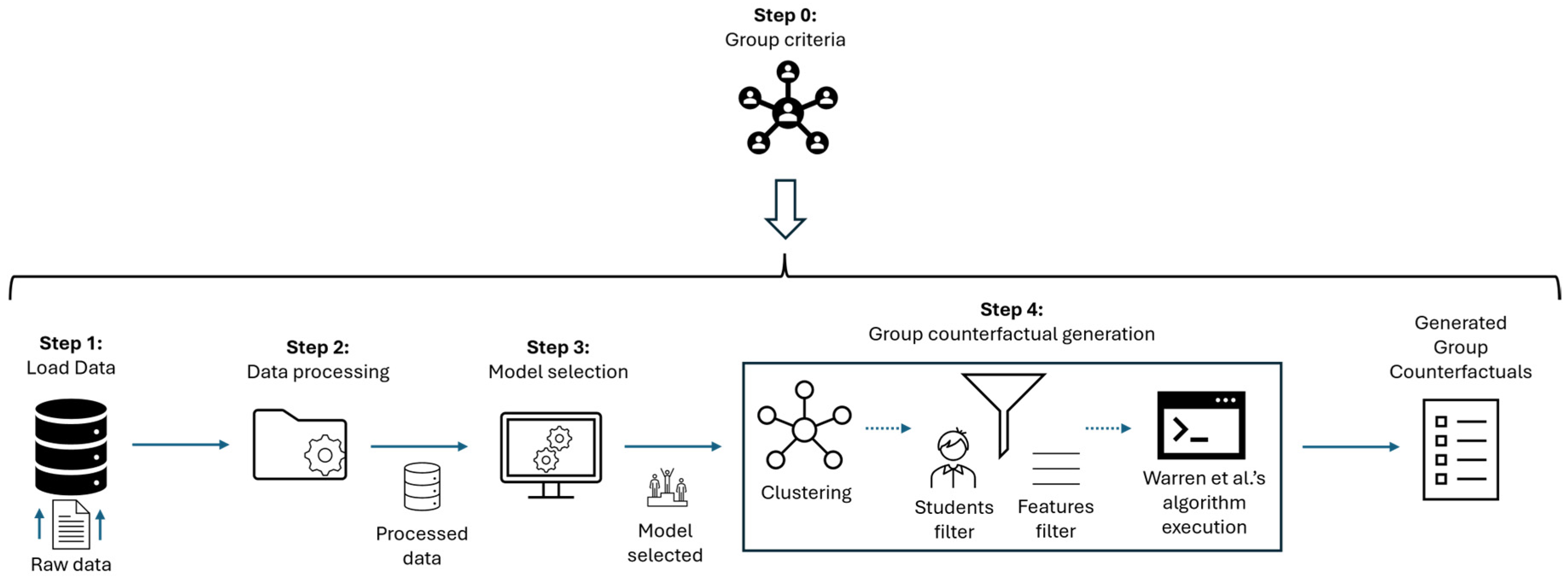

- Data loading (step 1): Data are loaded into the pipeline.

- Data processing (step 2): Data are conveniently processed so that machine learning algorithms can obtain predictive models from them.

- Model selection (step 3): The best model is selected based on the results obtained.

- Group counterfactual generation (step 4): From the model obtained and the dataset itself, a process is conducted to obtain a group counterfactual for each of the groups defined in our problem. As illustrated, this step begins with a clustering process to divide the population according to the criteria defined in step 0. It also defines values for some parameters related to the features to be used and the students to consider in each cluster, before finally applying Warren’s algorithm.

| Algorithm 1: Group counterfactual generation |

| Input: RD //Raw dataset Output: GC //Group counterfactuals 1: Load(RD) //Load data onto the pipeline 2: PD ← Data_Processing(RD) //PD denotes processed data 3: BM ← Model_Selection(PD) //BM denotes best model 4: C = {Ci} ← Clustering(PD), I = 1..k //Ci denotes each of the obtained clusters; k = n. clusters 5: Determine %f and %st //% of features and students to be considered 6: Determine m //m is the most suitable method of selecting students 7: For each i 8: C’i ← Subset(PD,Ci,%st,m) //We select only %st of students 9: GCi ← Warren_Alg(PD,BM,C’i,%f) //See [5] for all details of Warren et al.’s algorithm 10: Return GC = {GCi}, I = 1..k |

3.1. Data Loading

3.2. Data Processing

3.3. Model Selection

3.4. Group Counterfactual Generation

- The split of the whole population into groups, for which we will use clustering techniques;

- The selection of features to be modified by the group counterfactuals;

- The selection of the instances (students) of each group from whom we will build the group counterfactual.

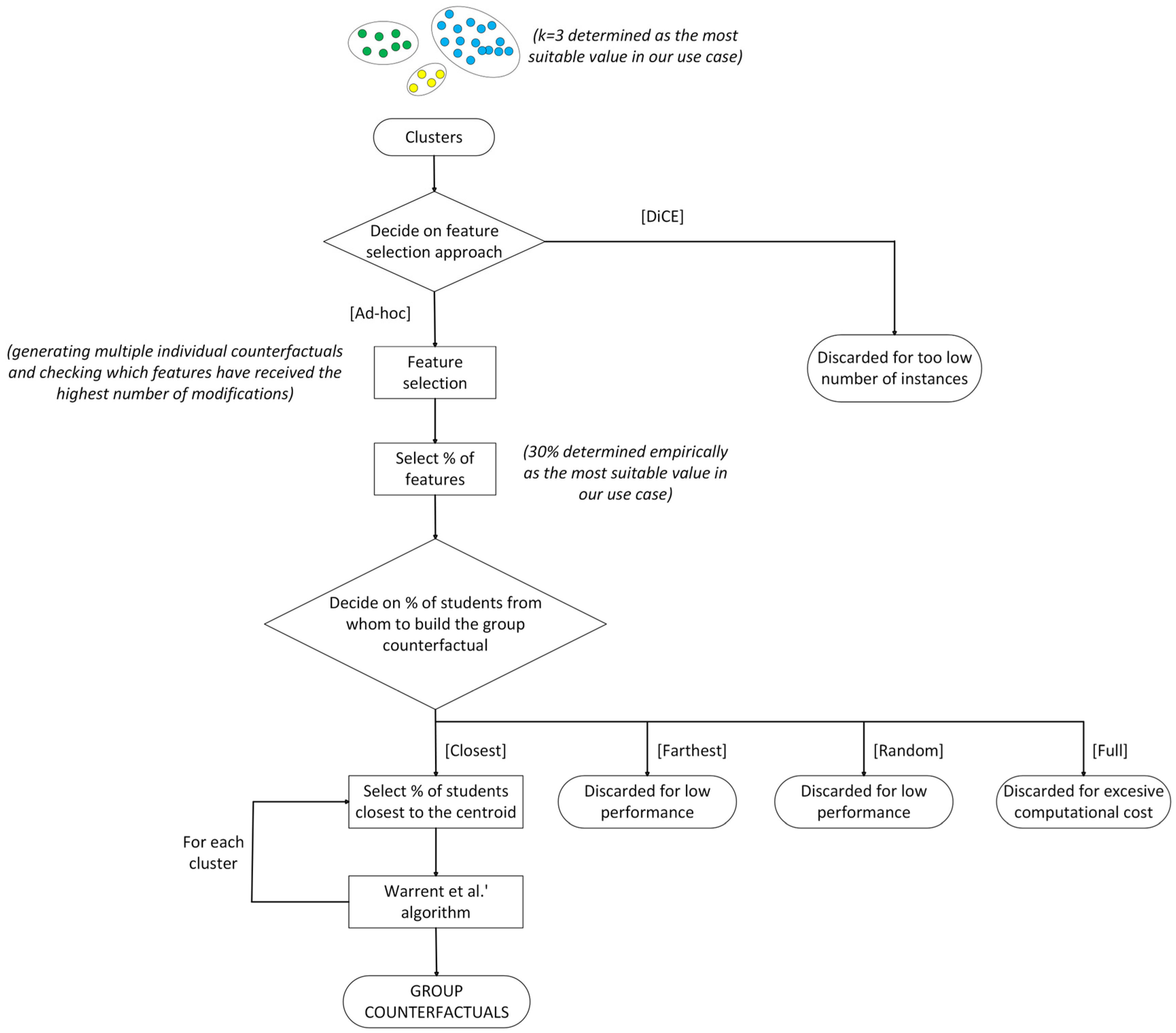

3.4.1. Clustering

- Cluster 0 is the most represented cluster, with 499 individuals. It is formed by those students who have had less interaction throughout the academic year, since most attributes have relatively low values in comparison with other clusters.

- Cluster 1 is the least represented cluster, with only 12 individuals. It is formed by those students who have interacted the most but still ended up failing.

- Cluster 2 is formed by 165 students who had more interaction than the students in cluster 0 but still exhibited a low level of interaction.

3.4.2. Selection of Features

- Choosing the features based on the importance provided by DiCE—note that DiCE orders features according to their relevance;

- An ad hoc approach consisting of generating multiple individual counterfactuals and checking which features have received the highest number of modifications.

3.4.3. Selection of Students

- Selecting the % of students closest to the centroid (named ‘closest’ throughout the remainder of the paper);

- Selecting a % of students farther away from the centroid (‘farthest’);

- Selecting a random % of students (‘random’);

- Selecting all students in the cluster (‘full’).

3.4.4. Execution of Warren’s Algorithm

- The counterfactual for cluster 0 indicates that it would be useful for students of this type (those who failed, having very low interaction levels) to have more clicks (higher activity) on three types of resources: external quizzes, collaboration (although not explicitly explained in the dataset, we presume that these are clicks on collaborative tasks), and resources—see all details in [38].

- For cluster 1 (students with high levels of activity, but still failing), the counterfactual appears to recommend fewer interactions, which seems paradoxical. This is likely to indicate that there are too few students in this cluster, and it is challenging to obtain a valuable general recovery pattern. In this case, other personalized interventions could be more useful. For instance, in small and potentially unstable clusters like this, where unrealistic counterfactuals may be obtained, it would be interesting to integrate simple monotonicity constraints or even individual-level counterfactuals.

- For cluster 2 (students with moderately low interaction levels), there is a recommendation to increase the activity, particularly in glossaries, as well as homepages and resources.

4. Results and Discussion

4.1. Group Counterfactual Success (RQ1)

- Validity: This represents a success rate that reflects the relationship between the number of instances in a group that have changed class by using a certain counterfactual with respect to the total instances of that group, according to Equation (1), as formally defined in Mothilal et al., 2020 [14]. In the context of this section, it represents the percentage of students that have transitioned from failing to passing by using the group counterfactual obtained for this cluster, with respect to the total number of students in the cluster.

- Execution time: This measures the time (in seconds) to generate a certain counterfactual. In the context of this section, it represents the time needed to generate a group counterfactual for a certain cluster.

4.2. Comparison of Group and Individual Counterfactuals (RQ2)

- Sparsity: This measures the relationship between the number of features modified in a counterfactual and the total amount of features in the original instance, as formally defined in Equation (2), according to Mothilal et al. [14].

- Proximity: This measures the average of the feature-wise distances between the counterfactual and the original instance, as formally described in Equation (3), according to Mothilal. Note that the formula used is only valid for continuous features such as the ones used in our use case and would need to be adapted in problems with categorial features [14].

- Regarding validity, as expected, all students are successfully recovered with individual counterfactuals (validity = 1.0), since each student has been provided with a concrete, customized counterfactual, which has been specifically built for him/her. However, the group counterfactuals do not lag behind and also reach a 1.0 validity value in clusters 0 and 1, as well as 0.98 in cluster 2. Note that this is a very positive result considering that only one counterfactual has been used to recover all students in each cluster.

- With respect to sparsity, it is observed that individual counterfactuals change fewer variables on average (higher sparsity). Although the number of features to be changed is an aspect that can be adjusted as a parameter, in this case, more variables need to be changed in the group counterfactuals in comparison to individual ones to obtain similar validity values. This is also expectable behavior, because it is easier to find a combination of actionable features for a particular individual rather than a combination of features that work for all individuals in a cluster.

- Regarding proximity, it is observed that group counterfactuals have values closer to 0, which indicates that, although they modify more variables on average than individual counterfactuals, the changes in terms of the features’ values (clicks) are lighter and less abrupt. Therefore, the variations suggested by the counterfactual explanations seem more feasible compared to individual counterfactuals.

- Finally, it can be observed that less time is required (within a factor of 3 to 4) to generate a group counterfactual for all instances of a cluster than to generate an individual counterfactual for each learner in the cluster.

5. Limitations

6. Conclusions and Future Work

Future Work

- The main idea for further research is the proposal of new ways for creating a certain group counterfactual from a given set of instances in a particular cluster. The current solution opts for an instance-based approach, in which explanations are created by modifying the original instances in a uniform way, applying the same counterfactual transformation repeatedly (i.e., substituting the same target value in several predictive instances). However, there are other possible alternatives; for example, counterfactual groups could be formed by showing ranges of values or generalizations of feature differences computed from sets of similar instances.

- A promising line would be to add simple monocity constraints for the features to be included in the counterfactuals or even use individual-level counterfactuals, particularly when small clusters are generated, in order to gain plausibility.

- In this research, we have used K-means for the clustering of instances. It could be interesting to try other clustering approaches, such as rule-based clustering analysis, using neural networks to improve instance clustering, or even simply applying other clustering tools such as DBSCAN. In particular, DBSCAN seems interesting since it permits us to capture the density of the population and obtain groups of similar instances with no need to specify the number of clusters. Regardless of the clustering approach used, it would also be interesting to improve the approach presented by providing the functionality to perform clustering sensitivity analyses, so that the user is aware of the quality of the clusters generated.

- While our validation used only OULAD, this remains the most widely used and recognized benchmark in educational data mining, with countless studies relying on it for dropout prediction, engagement analysis, and explainable AI research [57]. Nonetheless, it would be interesting to generalize to diverse datasets from other domains in order to confirm the preliminary results obtained in our use case or even to identify some improvable aspects in our approach. In particular, it would be interesting to focus on more complex datasets with more features and instances so as to assess the scalability of the proposal presented in this paper.

- Following on from the previous point, the used dataset’s quality may impact the results obtained when generating counterfactuals. For this reason, it would be interesting to implement a mechanism to automatically inform the user about different aspects depending on the dataset used in each case, such as model reliability, uncertainty quantification, significance, and confidence intervals in data splits so as to assess robustness, stability when small clusters appear, and sensitivity for parameters. It would also be useful to apply fine-tuning mechanisms for parameters.

- Moreover, it would be interesting to determine whether group counterfactuals can substitute or have to co-exist with individual counterfactuals in certain domains, particularly those that are critical, such as education, medicine, or safety. It would also be interesting to perform a large-scale study in each of these domains to clearly measure the impact of group counterfactuals in the decision-making process.

- An additional direction for future work is to complement the current algorithmic evaluation with human-centered or pedagogical evaluation. Although we measured the validity, sparsity, proximity, and execution time, these metrics do not capture how instructors interpret the explanations or whether the suggested changes are meaningful in real teaching contexts. User studies with tutors and students, or small-scale classroom pilots, would allow us to evaluate the clarity, usefulness, and practical relevance of group counterfactuals and better understand how they can support decision making in authentic educational settings.

Supplementary Materials

Author Contributions

Funding

Data Availability Statement

Acknowledgments

Conflicts of Interest

Appendix A. Quantitative Validation Statistical Tests

- That the group method does not perform better than the individual method in terms of sparsity (individual > group), since the group method requires a higher number of altered variables.

- That the group method performs better than the individual method in terms of proximity (group > individual), since the distance between each student and their altered equivalent instance is smaller in the case of the group counterfactual, which indicates smaller changes.

- That the group method performs better than the individual method in terms of time per student (individual > group), since the group method requires less time per student to construct the counterfactual.

| H0 | H1 | n | Z | r | p-Value | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sparsity | Individual ≤ Group | Individual > Group | 499 | 19.96 | 0.89 | <0.001 | H0 rejected |

| Proximity | Group ≤ Individual | Group > Individual | 499 | −18.57 | 0.85 | <0.001 | H0 rejected |

| Execution time (s) (per student) | Individual ≤ Group | Individual > Group | 499 | 19.36 | 0.87 | <0.001 | H0 rejected |

| H0 | H1 | n | Z | r | p-Value | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sparsity | Individual ≤ Group | Individual > Group | 12 | 3.15 | 0.91 | 0.001 | H0 rejected |

| Proximity | Group ≤ Individual | Group > Individual | 12 | −2.9 | 0.84 | 0.002 | H0 rejected |

| Execution time (s) (per student) | Individual ≤ Group | Individual > Group | 12 | 3.06 | 0.88 | 0.001 | H0 rejected |

| H0 | H1 | n | Z | r | p-Value | Result | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Sparsity | Individual ≤ Group | Individual > Group | 165 | 11.15 | 0.87 | <0.001 | H0 rejected |

| Proximity | Group ≤ Individual | Group > Individual | 165 | −8.4 | 0.67 | <0.001 | H0 rejected |

| Execution time (s) (per student) | Individual ≤ Group | Individual > Group | 165 | 11.14 | 0.87 | <0.001 | H0 rejected |

References

- Ahani, N.; Andersson, T.; Martinello, A.; Teytelboym, A.; Trapp, A.C. Placement Optimization in Refugee Resettlement. Oper. Res. 2021, 69, 1468–1486. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Guidotti, R. Counterfactual Explanations and How to Find Them: Literature Review and Benchmarking. Data Min. Knowl. Disc. 2024, 38, 2770–2824. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cavus, M.; Kuzilek, J. The Actionable Explanations for Student Success Prediction Models: A Benchmark Study on the Quality of Counterfactual Methods. In Proceedings of the Human-Centric Explainable AI in Education Workshop (HEXED 2024), Atlanta, GA, USA, 14 June 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Wachter, S.; Mittelstadt, B.; Russell, C. Counterfactual Explanations without Opening the Black Box: Automated Decisions and the GDPR. Harv. J. Law Technol. 2017, 31, 841. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Warren, G.; Delaney, E.; Guéret, C.; Keane, M.T. Explaining Multiple Instances Counterfactually: User Tests of Group-Counterfactuals for XAI. In Proceedings of the Case-Based Reasoning Research and Development: 32nd International Conference, ICCBR 2024, Merida, Mexico, 1–4 July 2024; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2024; pp. 206–222. [Google Scholar]

- Keane, M.T.; Smyth, B. Good Counterfactuals and Where to Find Them: A Case-Based Technique for Generating Counterfactuals for Explainable AI (XAI). In Case-Based Reasoning Research and Development, Proceedings of the 30th International Conference, ICCBR 2022, Nancy, France, 12–15 September 2022; Watson, I., Weber, R., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 163–178. [Google Scholar]

- Karalar, H.; Kapucu, C.; Gürüler, H. Predicting Students at Risk of Academic Failure Using Ensemble Model during Pandemic in a Distance Learning System. Int. J. Educ. Technol. High. Educ. 2021, 18, 63. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Adejo, O.; Connolly, T. An Integrated System Framework for Predicting Students’ Academic Performance in Higher Educational Institutions. Int. J. Comput. Sci. Inf. Technol. 2017, 9, 149–157. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Helal, S.; Li, J.; Liu, L.; Ebrahimie, E.; Dawson, S.; Murray, D.J.; Long, Q. Predicting Academic Performance by Considering Student Heterogeneity. Knowl.-Based Syst. 2018, 161, 134–146. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ajjawi, R.; Dracup, M.; Zacharias, N.; Bennett, S.; Boud, D. Persisting Students’ Explanations of and Emotional Responses to Academic Failure. High. Educ. Res. Dev. 2020, 39, 185–199. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nkhoma, C.; Dang-Pham, D.; Hoang, A.-P.; Nkhoma, M.; Le-Hoai, T.; Thomas, S. Learning Analytics Techniques and Visualisation with Textual Data for Determining Causes of Academic Failure. Behav. Inf. Technol. 2020, 39, 808–823. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- van Vemde, L.; Donker, M.H.; Mainhard, T. Teachers, Loosen up! How Teachers Can Trigger Interpersonally Cooperative Behavior in Students at Risk of Academic Failure. Learn. Instr. 2022, 82, 101687. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gagaoua, I.; Brun, A.; Boyer, A. A Frugal Model for Accurate Early Student Failure Prediction. In Proceedings of the LICE—London International Conference on Education, London, UK, 4–6 November 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Mothilal, R.K.; Sharma, A.; Tan, C. Explaining Machine Learning Classifiers through Diverse Counterfactual Explanations. In Proceedings of the 2020 Conference on Fairness, Accountability, and Transparency, Barcelona, Brazil, 27 January 2020; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2020; pp. 607–617. [Google Scholar]

- Garcia-Zanabria, G.; Gutierrez-Pachas, D.A.; Camara-Chavez, G.; Poco, J.; Gomez-Nieto, E. SDA-Vis: A Visualization System for Student Dropout Analysis Based on Counterfactual Exploration. Appl. Sci. 2022, 12, 5785. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Tsiakmaki, M.; Ragos, O. A Case Study of Interpretable Counterfactual Explanations for the Task of Predicting Student Academic Performance. In Proceedings of the 2021 25th International Conference on Circuits, Systems, Communications and Computers (CSCC), Platanias, Greece, 19–22 July 2021; pp. 120–125. [Google Scholar]

- Reichardt, C.S. The Counterfactual Definition of a Program Effect. Am. J. Eval. 2022, 43, 158–174. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Allan, V.; Ramagopalan, S.V.; Mardekian, J.; Jenkins, A.; Li, X.; Pan, X.; Luo, X. Propensity Score Matching and Inverse Probability of Treatment Weighting to Address Confounding by Indication in Comparative Effectiveness Research of Oral Anticoagulants. J. Comp. Eff. Res. 2020, 9, 603–614. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Callaway, B. Difference-in-Differences for Policy Evaluation. In Handbook of Labor, Human Resources and Population Economics; Springer: Berlin/Heidelberg, Germany, 2023; pp. 1–61. [Google Scholar]

- Cattaneo, M.D.; Titiunik, R. Regression Discontinuity Designs. Annu. Rev. Econ. 2022, 14, 821–851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Matthay, E.C.; Smith, M.L.; Glymour, M.M.; White, J.S.; Gradus, J.L. Opportunities and Challenges in Using Instrumental Variables to Study Causal Effects in Nonrandomized Stress and Trauma Research. Psychol. Trauma Theory Res. Pract. Policy 2023, 15, 917–929. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dandl, S.; Molnar, C.; Binder, M.; Bischl, B. Multi-Objective Counterfactual Explanations. In Proceedings of the Parallel Problem Solving from Nature—PPSN XVI; Bäck, T., Preuss, M., Deutz, A., Wang, H., Doerr, C., Emmerich, M., Trautmann, H., Eds.; Springer International Publishing: Cham, Switzerland, 2020; pp. 448–469. [Google Scholar]

- Kim, B.; Khanna, R.; Koyejo, O.O. Examples Are Not Enough, Learn to Criticize! Criticism for Interpretability. In Proceedings of the Advances in Neural Information Processing Systems, Barcelona, Spain, 5–10 December 2016; Curran Associates, Inc.: New York, NY, USA, 2016; Volume 29. [Google Scholar]

- Duong, M.; Luchansky, J.B.; Porto-Fett, A.C.S.; Warren, C.; Chapman, B. Developing a Citizen Science Method to Collect Whole Turkey Thermometer Usage Behaviors. Food Prot. Trends 2019, 39, 387–397. [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B.I.; Chimedza, C.; Bührmann, J.H. Individualized Help for At-Risk Students Using Model-Agnostic and Counterfactual Explanations. Educ. Inf. Technol. 2022, 27, 1539–1558. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Smith, B.I.; Chimedza, C.; Bührmann, J.H. Global and Individual Treatment Effects Using Machine Learning Methods. Int. J. Artif. Intell. Educ. 2020, 30, 431–458. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afrin, F.; Hamilton, M.; Thevathyan, C. Exploring Counterfactual Explanations for Predicting Student Success. In Proceedings of the 23rd International Conference on Computational Science, Prague, Czech Republic, 3–5 July 2023; Mikyška, J., de Mulatier, C., Paszynski, M., Krzhizhanovskaya, V.V., Dongarra, J.J., Sloot, P.M.A., Eds.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2023; pp. 413–420. [Google Scholar]

- Swamy, V.; Radmehr, B.; Krco, N.; Marras, M.; Käser, T. Evaluating the Explainers: Black-Box Explainable Machine Learning for Student Success Prediction in MOOCs. In Proceedings of the 15th International Conference on Educational Data Mining, Durham, UK, 24–27 July 2022; pp. 98–109. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Nilforoshan, H.; Gaebler, J.D.; Shroff, R.; Goel, S. Causal Conceptions of Fairness and Their Consequences. In Proceedings of the International Conference on Machine Learning, Vancouver, BC, Canada, 28 June 2022; pp. 16848–16887. [Google Scholar]

- Suffian, M.; Kuhl, U.; Alonso-Moral, J.M.; Bogliolo, A. CL-XAI: Toward Enriched Cognitive Learning with Explainable Artificial Intelligence. In Software Engineering and Formal Methods, Proceedings of the SEFM 2023 Collocated Workshops, Eindhoven, The Netherlands, 6–10 November 2023; Aldini, A., Ed.; Springer Nature: Cham, Switzerland, 2024; pp. 5–27. [Google Scholar]

- Alhossaini, M.; Aloqeely, M. Counter-Factual Analysis of On-Line Math Tutoring Impact on Low-Income High School Students. In Proceedings of the 2021 20th IEEE International Conference on Machine Learning and Applications (ICMLA), Pasadena, CA, USA, 13–16 December 2021; pp. 1063–1068. [Google Scholar]

- Li, Y.; Xu, M.; Miao, X.; Zhou, S.; Qian, T. Prompting Large Language Models for Counterfactual Generation: An Empirical Study. In Proceedings of the 2024 Joint International Conference on Computational Linguistics, Language Resources and Evaluation (LREC-COLING 2024), Torino, Italy, 20–25 May 2024. [Google Scholar]

- Alqahtani, H.; Kavakli-Thorne, M.; Kumar, G. Applications of Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs): An Updated Review. Arch. Comput. Methods Eng. 2021, 28, 525–552. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Afzaal, M.; Zia, A.; Nouri, J.; Fors, U. Informative Feedback and Explainable AI-Based Recommendations to Support Students’ Self-Regulation. Technol. Know Learn. 2024, 29, 331–354. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramaswami, G.; Susnjak, T.; Mathrani, A. Supporting Students’ Academic Performance Using Explainable Machine Learning with Automated Prescriptive Analytics. Big Data Cogn. Comput. 2022, 6, 105. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cui, J.; Yu, M.; Jiang, B.; Zhou, A.; Wang, J.; Zhang, W. Interpretable Knowledge Tracing via Response Influence-Based Counterfactual Reasoning. In Proceedings of the 2024 IEEE 40th International Conference on Data Engineering (ICDE), Utrecht, The Netherlands, 13–17 May 2024; pp. 1103–1116. [Google Scholar]

- Afzaal, M.; Nouri, J.; Zia, A.; Papapetrou, P.; Fors, U.; Wu, Y.; Li, X.; Weegar, R. Automatic and Intelligent Recommendations to Support Students’ Self-Regulation. In Proceedings of the 2021 International Conference on Advanced Learning Technologies (ICALT), Tartu, Estonia, 12–15 July 2021; pp. 336–338. [Google Scholar]

- Kuzilek, J.; Hlosta, M.; Zdrahal, Z. Open University Learning Analytics Dataset. Sci. Data 2017, 4, 170171. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Chawla, N.V.; Bowyer, K.W.; Hall, L.O.; Kegelmeyer, W.P. SMOTE: Synthetic Minority Over-Sampling Technique. J. Artif. Intell. Res. 2002, 16, 321–357. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lemaître, G.; Nogueira, F.; Aridas, C.K. Imbalanced-Learn: A Python Toolbox to Tackle the Curse of Imbalanced Datasets in Machine Learning. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2017, 18, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Erickson, N.; Mueller, J.; Shirkov, A.; Zhang, H.; Larroy, P.; Li, M.; Smola, A. AutoGluon-Tabular: Robust and Accurate AutoML for Structured Data. arXiv 2020, arXiv:2003.06505. [Google Scholar]

- Çorbacıoğlu, Ş.K.; Aksel, G. Receiver operating characteristic curve analysis in diagnostic accuracy studies: A guide to interpreting the area under the curve value. Turk. J. Emerg. Med. 2023, 23, 195–198. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Lloyd, S. Least Squares Quantization in PCM. IEEE Trans. Inform. Theory 1982, 28, 129–137. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- MacQueen, J. Some Methods for Classification and Analysis of Multivariate Observations. In Proceedings of the Fifth Berkeley Symposium on Mathematical Statistics and Probability, Volume 1: Statistics; University of California Press: Oakland, CA, USA, 1967; Volume 5.1, pp. 281–298. [Google Scholar]

- Shi, C.; Wei, B.; Wei, S.; Wang, W.; Liu, H.; Liu, J. A quantitative discriminant method of elbow point for the optimal number of clusters in clustering algorithm. EURASIP J. Wirel. Commun. Netw. 2021, 2021, 31. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Herdiana, I.; Kamal, M.A.; Triyani; Estri, M.N. A More Precise Elbow Method for Optimum K-means Clustering. arXiv 2025, arXiv:2502.00851. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Pedregosa, F.; Varoquaux, G.; Gramfort, A.; Michel, V.; Thirion, B.; Grisel, O.; Blondel, M.; Prettenhofer, P.; Weiss, R.; Dubourg, V.; et al. Scikit-Learn: Machine Learning in Python. J. Mach. Learn. Res. 2011, 12, 2825–2830. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rousseeuw, P.J. Silhouettes: A Graphical Aid to the Interpretation and Validation of Cluster Analysis. J. Comput. Appl. Math. 1987, 20, 53–65. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Davies, D.L.; Bouldin, D.W. A Cluster Separation Measure. IEEE Trans. Pattern Anal. Mach. Intell. 1979, PAMI-1, 224–227. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Caliński, T.; Harabasz, J. A Dendrite Method for Cluster Analysis. Commun. Stat. 1974, 3, 1–27. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Borna, M.R.; Saadat, H.; Hojjati, A.T.; Akbari, E. Analyzing click data with AI: Implications for student performance prediction and learning assessment. Front. Educ. 2024, 9, 1421479. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Barocas, S.; Selbst, A.D. Big Data’s Disparate Impact. Calif. Law Rev. 2016, 104, 671. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Steele, C.M.; Aronson, J. Stereotype threat and the intellectual test performance of African Americans. J. Pers. Soc. Psychol. 1995, 69, 797–811. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Rosenthal, R.; Jacobson, L. Pygmalion in the classroom. Urban. Rev. 1968, 3, 16–20. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Holstein, K.; McLaren, B.M.; Aleven, V. Co-Designing a Real-Time Classroom Orchestration Tool to Support Teacher–AI Complementarity. Learn. Anal. 2019, 6, 27–52. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Winfield, A.F.T.; Jirotka, M. Ethical governance is essential to building trust in robotics and artificial intelligence systems. Phil. Trans. R. Soc. A 2018, 376, 20180085. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef] [PubMed]

- Alhakbani, H.A.; Alnassar, F.M. Open Learning Analytics: A Systematic Review of Benchmark Studies using Open University Learning Analytics Dataset (OULAD). In Proceedings of the 2022 7th International Conference on Machine Learning Technologies (ICMLT 22), Rome, Italy, 11–13 March 2022; Association for Computing Machinery: New York, NY, USA, 2022; pp. 81–86. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Cohen, J. Statistical Power Analysis for the Behavioral Sciences, 2nd ed.; LEA: Hillsdate, NJ, USA, 1988. [Google Scholar]

| Model | F2-Score |

|---|---|

| ExtraTrees_r4_BAG_L1 | 0.688 |

| RandomForest_r34_BAG_L1 | 0.683 |

| ExtraTrees_r172_BAG_L1 | 0.675 |

| ExtraTrees_r126_BAG_L1 | 0.668 |

| ExtraTrees_r178_BAG_L1 | 0.663 |

| RandomForest_r15_BAG_L1 | 0.649 |

| RandomForestGini_BAG_L1 | 0.645 |

| RandomForest_r166_BAG_L1 | 0.645 |

| RandomForest_r39_BAG_L1 | 0.642 |

| RandomForest_r127_BAG_L1 | 0.641 |

| 0 | n_Students | n_Clicks_Externalquiz | n_Clicks_Forumng | n_Clicks_Glossary | n_Clicks_Homepage | n_Clicks_Oucollaborate | n_Clicks_Oucontent | n_Clicks_Ouwiki | n_Clicks_Resource | n_Clicks_Subpage | n_Clicks_Url | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 499 | mean | 3.5 | 59.38 | 4.53 | 92.75 | 3.35 | 86.57 | 11.85 | 22.3 | 58.76 | 7.02 |

| stdev | 4.8 | 59.9 | 13.41 | 61.16 | 6.84 | 78.56 | 24 | 19.44 | 51.43 | 7.9 | ||

| 1 | 12 | mean | 20.91 | 1239.41 | 11.08 | 978.83 | 29.75 | 215.41 | 130.25 | 114.41 | 491.75 | 52.16 |

| stdev | 13.48 | 607.38 | 19.2 | 332.84 | 21.61 | 168.3 | 105.75 | 56.66 | 261.24 | 30.7 | ||

| 2 | 165 | mean | 10.02 | 302.52 | 8.66 | 293.34 | 13.67 | 186.01 | 59.81 | 70.97 | 217.37 | 29.6 |

| stdev | 10.24 | 164.73 | 36.57 | 112.15 | 17 | 131.97 | 60.56 | 62.9 | 130.58 | 28.42 |

| Name | Explanation | Value | Interpretation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Silhouette [48] | It takes values between −1 and 1; the closer to 1, the better. It evaluates the quality of the clusters by indicating how well each data point within its own cluster compares to other clusters. Values close to 1 indicate that the points in the cluster are similar to each other, while a value close to −1 indicates that the points are closer to a different cluster than the one that was initially assigned. | 0.49 | This value indicates that the clusters are moderately well defined. While most points seem reasonably assigned to their clusters, some overlap between clusters might be present. |

| Davies–Bouldin [49] | It takes values greater than or equal to 0, with the lowest value being the best. It evaluates the quality of the clusters by focusing on the relationship between the dispersion within clusters (intra-cluster) and the separation between clusters (inter-cluster). It is constructed as the quotient of both values. Thus, when the clusters are separated and compact, the value of this index is minimized. A value close to 0 indicates good separation between clusters, while high values indicate an overlap between clusters. | 0.65 | This suggests that the clusters have moderate internal dispersion and that the separation between clusters may not be very distinct, pointing to a less compact cluster structure. |

| Calinski–Harabasz [50] | It takes values greater than or equal to 0; the higher, the better. It evaluates the quality of clusters based on the ratio of intra-cluster dispersion to inter-cluster dispersion. A high value indicates better-defined clusters, where the points within each cluster are more grouped and the clusters are well separated from each other, while a lower value suggests worse quality, with high intra-cluster dispersion. | 494.16 | This score suggests that the clusters exhibit moderate cohesion and separation. A higher score typically indicates better-defined clusters, while this value points to somewhat looser cluster formation. |

| Cluster | n_Clicks_Externalquiz | n_Clicks_Forumng | n_Clicks_Glossary | n_Clicks_Homepage | n_Clicks_Oucollaborate | n_Clicks_Oucontent | n_Clicks_Ouwiki | n_Clicks_Resource | n_Clicks_Subpage | n_Clicks_Url |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 13 | - | - | - | 27 | - | - | 281 | - | - |

| 1 | 17 | 788 | - | - | 25 | - | - | - | - | - |

| 2 | - | - | 182 | 498 | - | - | - | 76 | - | - |

| % Features | Validity | Execution Time |

|---|---|---|

| 10 | 0.953 | 232.24 |

| 20 | 0.963 | 32.39 |

| 30 | 0.993 | 30.33 |

| 40 | 0.993 | 19.86 |

| 50 | 0.996 | 28.01 |

| Technique | % Students | Validity | Average Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Closest | 1.0% | 0.969 | 4.37 |

| 5.0% | 0.966 | 18.3 | |

| 10.0% | 0.962 | 35.35 | |

| 15.0% | 0.922 | 22.67 | |

| 20.0% | 0.986 | 44.43 | |

| 25.0% | 0.993 | 92.13 | |

| 50.0% | 1.0 | 192.8 | |

| Farthest | 1.0% | 0.959 | 7.91 |

| 5.0% | 0.963 | 36.05 | |

| 10.0% | 0.957 | 58.64 | |

| 15.0% | 0.990 | 34.54 | |

| 20.0% | 0.980 | 44.22 | |

| 25.0% | 0.999 | 112.18 | |

| 50.0% | 1.0 | 204.17 | |

| Random | 1.0% | 0.937 | 4.51 |

| 5.0% | 0.967 | 38.05 | |

| 10.0% | 0.987 | 42.49 | |

| 15.0% | 0.977 | 32.86 | |

| 20.0% | 0.984 | 44.54 | |

| 25.0% | 1.0 | 117.32 | |

| 50.0% | 1.0 | 189.27 | |

| Full | 100.0% | 1.0 | 364.18 |

| Cluster | Cluster Students | Counterfactual Type | Validity | Sparsity | Proximity | Execution Time (s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 0 | 499 | Individual | 1.0 | 0.816 | −21.93 | 239.50 |

| Group | 1.0 | 0.7 | −10.748 | 62.94 | ||

| 1 | 12 | Individual | 1.0 | 0.848 | −9.814 | 5.77 |

| Group | 1.0 | 0.7 | −0.914 | 1.58 | ||

| 2 | 165 | Individual | 1.0 | 0.848 | −5.835 | 79.85 |

| Group | 0.98 | 0.7 | −0.781 | 26.46 |

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the authors. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.

Share and Cite

Buñay-Guisñan, P.; Cano, A.; Anguera, A.; Lara, J.A.; Romero, C. Group Counterfactual Explanations: A Use Case to Support Students at Risk of Dropping Out in Online Education. Electronics 2026, 15, 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010051

Buñay-Guisñan P, Cano A, Anguera A, Lara JA, Romero C. Group Counterfactual Explanations: A Use Case to Support Students at Risk of Dropping Out in Online Education. Electronics. 2026; 15(1):51. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010051

Chicago/Turabian StyleBuñay-Guisñan, Pamela, Alberto Cano, Aurea Anguera, Juan A. Lara, and Cristóbal Romero. 2026. "Group Counterfactual Explanations: A Use Case to Support Students at Risk of Dropping Out in Online Education" Electronics 15, no. 1: 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010051

APA StyleBuñay-Guisñan, P., Cano, A., Anguera, A., Lara, J. A., & Romero, C. (2026). Group Counterfactual Explanations: A Use Case to Support Students at Risk of Dropping Out in Online Education. Electronics, 15(1), 51. https://doi.org/10.3390/electronics15010051