Abstract

All grid faults can cause significant problems within the power grid, including disconnection or malfunctions of wind energy conversion systems (WECSs) connected to the power grid. This study proposes a comparative analysis of the fault ride-through capability of a WECS-based permanent magnet synchronous generator (PMSG) system. To overcome these issues, active crowbar and capacitive bridge fault current limiter-based machine learning algorithm protection methods are implemented within the WECS system, both separately and in a hybrid. The regression approach is applied for the machine-side converter (MSC) and the grid side converter (GSC) controllers, which involve numerical data. The classification method is employed for protection system controllers, which work with data in distinct classes. These approaches are trained on historical data to predict the optimal control characteristics of the wind turbine system in real time, taking into account both fault and normal operating conditions. The neural network trilayered model has the lowest root mean squared error and mean squared error values, and it has the highest R-squared values. Therefore, the neural network trilayered model can accurately model the nonlinear relationships between its variables and demonstrates the best performance. The neural network trilayered model is selected for the MSC control system in this study. On the other hand, support vector machine regression is selected for the GSC controller due to its superior results. The simulation results demonstrate that the proposed machine learning algorithm performance for WECS based on a PMSG is robustly utilized under different operating conditions during all grid faults.

1. Introduction

The global demand for electricity generated from clean and sustainable energy sources has increased in recent years [1]. The ability of wind turbines to rapidly integrate into modern power grids has led to a gradual increase in the number of wind turbines (WT) [2]. This increase in the number of WT has also brought with it several challenges. The primary challenge for grid-connected wind turbines is maintaining a connection to the power system during a grid fault [3,4]. Every wind turbine must remain connected to the grid in the event of a grid fault [5]. Each country has its own electrical grid regulations to ensure the stability of power grid systems [6]. Furthermore, the type of generator used in wind turbines is also crucial. The permanent magnet synchronous generator (PMSG) has recently become preferred over other generator types for wind turbines due to its high efficiency, compact size, and variable-speed operation. PMSG requires two power converters to connect to the power grid. DC link voltage fluctuations and overcurrent occur during a grid fault. These power converters are highly susceptible to the harmful effects of a grid fault [7,8]. Hardware and software solutions have been suggested in the literature to protect power converters and, at the same time, reduce these harmful effects. The crowbar circuit [9], static compensator (STATCOM) [10], and dynamic voltage restorer [11] are presented to improve the fault ride-through (FRT) performance of PMSG as hardware methods. Additionally, the predictive, adaptive, and nonlinear control are presented to improve the FRT performance of PMSG as software methods.

Recently, the machine learning (ML) algorithms have been applied in many renewable energy fields, especially for control systems of wind energy conversion systems (WECSs). In [12], Silva et al. examine the relationship between WT faults and environmental factors employing an ML methodology. The authors address the decline in performance of wind turbines beyond standard operating circumstances. In [13], Aslam et al. propose the dynamic optimization of recurrent networks on edge devices for wind speed prediction. This study enhances computing efficiency in distributed artificial intelligence systems. In [14], Huang et al. improve the quality of wind power forecasts by applying bias correction technologies to wind speeds derived from a numerical weather prediction model. In [15], Chen et al. developed a multi-class blade icing recognition model using mutual information feature selection and ensemble methods, aiming to mitigate the risks to aerodynamic efficiency and structural integrity associated with icing. In [16], Li et al. propose using frequency-based adversarial learning and cyclic fine-tuning for fault diagnosis of rotating machinery under labeled data constraints. In [17], Zang et al. develop a hybrid deep reinforcement learning method to address deployment and route optimization for unmanned aerial vehicle inspections in large-scale wind farms. In [18], Dheda et al. perform a multi-objective optimization of a grid-connected hybrid renewable energy system using metaheuristic algorithms, encompassing technical, economic, environmental, and social objectives. In [19], Grataloup et al. propose a federated learning-based approach for collaborative turbine and farm condition monitoring while preserving data privacy. In [20], Malik et al. propose a modified fuzzy Q-learning-based model for mechanical fault diagnosis in direct-drive WTs using electrical signals. In [21], Shahbaz et al. evaluate the performance of ML algorithms in diagnosing magnetization degradation faults in PMSGs and it is evaluated using flux and current signals, and the most suitable methods. In Ref. [22], Minaz et al. propose an effective method based on texture-based analysis for the detection of magnetization deterioration faults in axial-flux coreless PMSGs, unlike traditional methods in the literature. In [23], Alsafran et al. introduce a fractional order non-singular terminal sliding-mode control strategy supported by a deep-learning-based Lie-derivative estimator to achieve more reliable maximum power point tracking operation in wind turbine applications. In [24], Hadi et al. perform harmonic prediction of a wind and solar hybrid model using hybrid prediction models based on deep machine learning. In [25], Hernandez et al. present an electromagnetic design optimization of a PMSG using a deep neural network approach, aiming to minimize losses. In [26], Singh et al. perform load balancing and voltage control of a PMSG-based DG set for an independent feeder system using the distribution STATCOM and battery energy storage system. In [27], Suni et al. perform current transients and fault section identification in distribution networks with a doubly fed induction generator and PMSG using artificial neural networks. The above methods in the literature show that ML methods are effective in fault detection of the wind turbine based on PMSG, energy production estimation, and increasing system reliability in WT systems. In addition, these studies are related to the reduction in environmental impacts during energy production and the structural adverse effects of the WT system. However, structural adverse effects of the WT system have a more complex structure than the power grid connection problems of the WECS system. The proposed active crowbar and a capacitive bridge fault current limiter (CBFCL) based on an ML system detect grid faults and provide an active protection system against grid faults, whereas most of the previous methods in the literature are limited to passive monitoring and fault classification. In addition, the proposed active crowbar and CBFCL combination-based ML algorithm extends the operation time of the inverter under low-voltage conditions and strengthens the integration of wind turbine systems to the grid.

Most prior research in the literature has employed traditional control methods to enhance the fault ride-through capabilities of a WT based on a PMSG system. In this study, the FRT performance of a 1.5 MVA wind energy system based on PMSG is comparatively investigated using active crowbar (ACTcrw), CBFCL, and a combination of both (ACTcrw + CBFCL) protection methods, all based on an ML algorithm. This article contributes to the field in the following aspects:

- Machine learning algorithms have been extensively applied to improve FRT performance in a wind turbine based on a PMSG system. Two basic approaches to machine learning are used: classification and regression.

- More than 20 classifiers for each approach to machine learning have been systematically compared. The ensemble boosted tree classifier has the highest F1-score (99.39%) and accuracy (98.8%) for both protection methods.

- Three-phase symmetrical, two-phase asymmetrical, and single-phase asymmetrical faults are analyzed in this study. This comprehensive comparison reveals the performance behavior of protection and controller systems under different grid fault scenarios.

- The hybrid protection method reduces the Vdc oscillations by 25% during a three-phase symmetrical fault. The ML control method has illustrated exceptional capability in accurately detecting grid faults and dynamically adjusting ACTcrw and CBFCL to protect a wind turbine based on the PMSG system under all grid fault scenarios.

- The simulation results in this study demonstrate that the hybrid protection method based on an ML algorithm provides lower amplitude transient responses and quicker recovery times for both electrical and mechanical parameters compared to other protection methods.

2. Mechanical Drive and Mathematical Model of Wind Energy Conversion System

A variable-speed wind energy conversion system is modeled using a PMSG. The PMSG is connected to the grid using a machine-side converter (MSC), a DC-link capacitor, and a grid-side converter (GSC).

A standard WT model is used in this study. The following equation obtains the mechanical power derived from a WT [28].

Cp depicts power coefficient, which varies with blade pitch angle (β) and tip speed ratio (λ), A represents a swept area of a rotor, Vw represents wind speed, and ρ represents air density.

In this study, the PMSG is modeled using the standard mathematical model in the d-q synchronous reference frame. The following equations represent an electrical mathematical model of the PMSG [29,30,31]:

where Lq and Ld depict inductances, iq and id represent stator current, vd and vq are stator voltage, Rs depicts the stator resistance, λm depicts the flux linkage due to permanent magnets, and ωe represents the electrical angular speed.

3. Power Converter Topology and Control Method of WECS

Electrical parameters of the GSC, electrical parameters of the GSC, and electrical and mechanical parameters of the PMSG are given in Table 1, Table 2, and Table 3, respectively. An electrical equivalent circuit of a T-type converter is shown in Figure 1a. A T-type converter is utilized in both a GSC and an MSC structure. A T-type converter is preferred due to its lower total harmonic distortion value compared to the conventional two-level converter. Additionally, three-phase T-type converters produce higher output voltage levels. The switching signals of a T-type converter are obtained using a sinusoidal pulse width modulation. This modulation generates a square wave switching signal by comparing a carrier and reference waves. A carrier and reference signals are triangular waves and sine waves, respectively. An output voltage value of a single phase, corresponding to the switching states, is given in Table 4. According to table, the output voltage has three different values: Vdc/2, 0, and −Vdc/2. The switches are in the zero and one states, corresponding to the cut-off and on states, respectively.

Table 1.

Electrical parameters of the grid-side converter.

Table 2.

Aerodynamic characteristics of the wind turbine.

Table 3.

Electrical and mechanical parameters of the PMSG.

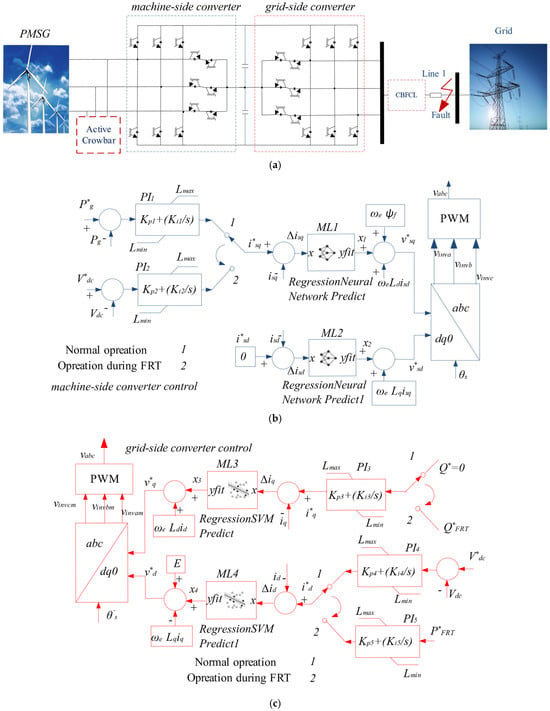

Figure 1.

Overall control architecture of PMSG based on WECS: (a) PMSG and converters; (b) machine-side converter-based ML control loop; (c) grid-side converter-based ML control loop.

Table 4.

Switch states and output voltage levels of T-type converter for single phase.

Traditional controllers have fixed parameters. Therefore, traditional controllers show limited adaptability in changing and complex systems, such as power grids. In contrast, the ML technique in this study is trained on a wide range of operating scenarios, including three-phase fault, two-phase fault, single-phase fault, and normal operation conditions. Unlike traditional control systems, the machine learning algorithm provides data-driven, fast responses without the need for continuous recalibration. Moreover, the machine learning algorithm addresses the complex relationships between DC voltage behavior, grid faults, and FRT requirements. In conclusion, machine learning algorithms are preferred because they have advantages over traditional control techniques, especially under nonlinear and rapidly changing grid conditions, as mentioned above.

3.1. Control Algorithm of MSC

An MSC and a GSC are used in the wind turbine system. Separate controllers for each converter are designed based on the ML algorithm. The MSC controller consists of two loops and a d-q synchronous reference frame, as illustrated in Figure 1b. An input to the q loop of the MSC is P*g in normal operation. During normal operation, power is continuously measured, and the measured power is compared with the reference power value. The result of this comparison is the input signal of PI1. This signal converts the i*sq current via PI1. During normal operation, isq current is continuously measured, and the measured isq current is compared with the i*sq current value. The result of this comparison is the ∆isq current. The ∆isq current is the input of the ML1 algorithm. The ML1 algorithm generates an appropriate x1 output value for each input value. The ML1 algorithm then generates the appropriate x1 output for each ∆isq value. Its output signal (x1) is combined with other signals ωeLdisd and ωeψf to produce the necessary voltage (v*sq) for switching.

During a grid fault, the switch shifts from position 1 to position 2. The V*dc value serves as input to the MSC controller’s q-loop. This reference V*dc is compared to the actual Vdc. The result of this comparison is the input signal of PI2. This signal converts the i*sq current via PI2. During grid fault operation, isq current is continuously measured, and the measured isq current is compared with the i*sq current value. The result of this comparison is the ∆isq current. The ∆isq current is an input of ML1. An ML1 then generates an appropriate x1 output for each ∆isq value. Its output signal (x1) is combined with other signals ωeLdisd and ωeψf to produce the necessary voltage (v*sq) for switching.

Under both normal and fault operation conditions, the i*sd value, used as input to the MSC controller’s d loop, is continuously measured and compared with its reference i*sd, which is zero. The result of this comparison is the ∆isd current. The difference yields the ∆isd current, feeding into the ML2 algorithm, which produces a suitable x2 output value for each input value. The ML2 output signal (x2) is combined with other signals ωeLqisq to determine the voltage (v*sd) needed for switching signals. To enhance transient response, the reference voltages (v*sd and v*sq) of an MSC system are added, as shown below.

3.2. Control Algorithm of GSC

The reference voltages (v*q and v*d) of GSC have been added to increase the transient response, which is expressed as follows.

The GSC controller consists of two loops and a d-q synchronous reference frame, as illustrated in Figure 1c. The input to the q loop of the GSC is Q in normal operation. The reference value of Q is set to zero. This value converts the i*q current via PI3. During normal operation, iq current is continuously measured, and the measured iq current is compared with the i*q current value. The result of this comparison is the ∆iq current. The ∆iq current serves as an input to ML3. An ML3 algorithm generates an appropriate x3 output value for each input value. The output signal (x3) of the ML3 algorithm is summed with ωeLdid to produce the required voltage (v*q) for switching signals.

During a grid fault, the switch moves from position 1 to position 2. The input to the GSC controller’s q-loop becomes Q*FRT. The i*q current is obtained via the PI3 controller. During a grid fault, iq current is continuously measured, and the measured iq current is compared with the i*q current value. The result of this comparison is the ∆iq current. This ∆iq current is again fed into the ML3 algorithm, which generates a suitable x3 output for each input. The output signal (x3) of the ML3 algorithm is summed with ωeLdid to produce the required voltage (v*q) for switching signals.

A GSC controller comprises two loops and the d-q synchronous reference frame. An input to a d loop of the GSC controller is V*dc during normal operating conditions. The V*dc reference value is compared with the measured Vdc. The result of this comparison is the input signal of PI4. This signal converts the i*d current via PI4. During normal operation, id current is continuously measured, and the measured id current is compared with the i*d current value. The result of this comparison is the ∆id current. The ∆id current is an input to ML4. An ML4 technique generates an appropriate x4 output for each ∆id value. The output signal (x4) from the ML4 algorithm is summed with E and −ωeLqiq to determine the required voltage (v*d) for switching signals.

During a grid fault, the switch moves from position 1 to position 2. The input to the q-loop of the GSC controller is P*FRT. The i*d current is obtained via the PI controller. During normal operation, id current is continuously measured, and the measured id current is compared with the i*d current value. The result of this comparison is the ∆id current. The ∆id current then feeds into the ML4 algorithm. The ML4 algorithm generates an appropriate x4 output for each input. The output signal (x4) from the ML4 algorithm is summed with E and −ωeLqiq to determine the required voltage (v*d) for switching signals [32].

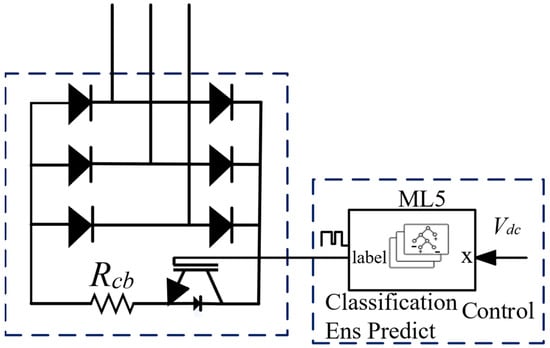

4. Structure and Control of Protection Methods

The structure of an active crowbar using the ML method is given in Figure 2. The active crowbar comprises a three-phase half-wave rectifier circuit, a controllable semiconductor switching component, and a resistor. Under normal operating conditions, the active crowbar remains inactive. During a grid fault, the active crowbar remains active. An ML algorithm has been incorporated into the control system of the active crowbar. The input to the ML algorithm is Vdc, which is continuously measured. The active crowbar sends a switching signal to the gate of a controllable semiconductor switching component based on the measured value. When a fault occurs in a power grid, the overvoltage generated in the WECS system is converted to heat through the resistor and safely discharged. A conventional crowbar remains permanently active, causing energy loss. However, an active crowbar is activated and deactivated in a controlled manner. After a grid fault, the parameters of a WT return to normal values, and an active crowbar is deactivated. The wind turbine continues to generate normal power and remains connected to the grid. An active crowbar resistor of 0.4 Ω, an anti-parallel diode rated at 3 kV/800 A, and a high-power IGBT rated at 2.5 kV/800 A are selected in this study due to the fact that the DC-link voltage level reaches approximately 2000 V during a grid fault.

Figure 2.

Structure of an active crowbar using ML method.

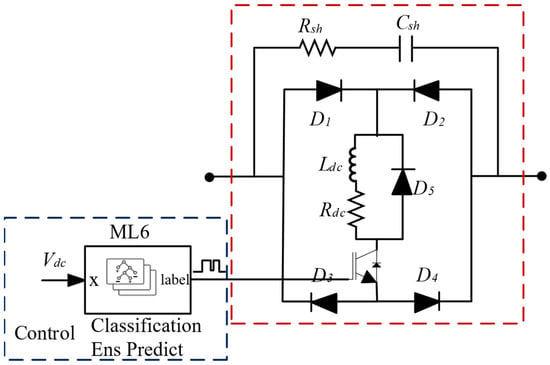

The structure of a CBFCL using the ML method is given in Figure 3. A CBFCL consists of a bridge structure and a series resistor–capacitor arrangement connected in parallel with it. Under normal operating conditions, the semiconductor switch is correctly activated, and the bridge remains continuously operational. Due to the low bridge resistance, it does not adversely affect the wind turbine system’s operation. The power flow of a WT continues normally. When a grid system fault occurs, an overcurrent arises in the grid system. A CBFCL control system detects a grid overcurrent and interrupts a switching signal of a semiconductor switching element. A bridge is disabled, and a series resistor–capacitor is engaged. Therefore, a high impedance is introduced into the grid system during a fault, preventing the harmful effects of overcurrent. This protects the semiconductor switches of the converter and the generator of the wind turbine from overcurrent and overvoltage. After a grid fault is cleared, the system parameters return to normal values, and a series resistor–capacitor is deactivated. The wind turbine continues to generate normal power and remains connected to the grid. A capacitive bridge fault current limiter series capacitor (Csh) and resistor (Rsh) of 50 µF and 10 Ω, a damping inductor (Ldc) and resistor (Rdc) of 0.001 H and 0.001 Ω, respectively, an bridge diode rated at 3 kV/800 A, and a high-power IGBT rated at 2.5 kV/800 A are selected in this study due to the fact that the DC-link voltage level reaches approximately 2000 V during a grid fault.

Figure 3.

Structure of a CBFCL using ML method.

5. Simulation Results

An ML algorithm is employed to enhance the FRT capability of a PMSG-based WT system in this study. There are two main approaches in ML: classification and regression. The regression approach is suitable for estimating continuous (numerical) variables, while the classification method is used to separate data into distinct classes. The regression approach is applied for MSC and GSC controllers, which involve numerical values. The classification method is employed for the active crowbar and CBFCL controllers.

The training dataset used in this study is generated entirely from simulations of MATLAB 2024b/Simulink, which is the WECS-based PMSG under a wide range of operating conditions, including single-phase, two-phase, three-phase grid fault, and normal operation. A total of 1501 labeled samples are collected by recording the electrical and mechanical characteristics of the WECS-based PMSG during different grid faults and normal operating conditions. In addition, key hyperparameters for the best-performing ML model are added to ensure reproducibility. The dataset is partitioned into 70% training, 15% validation, and 15% testing sets. Before training, all variables are processed using min–max normalization to eliminate scale imbalance. Furthermore, the interquartile range approach is used to eliminate outliers.

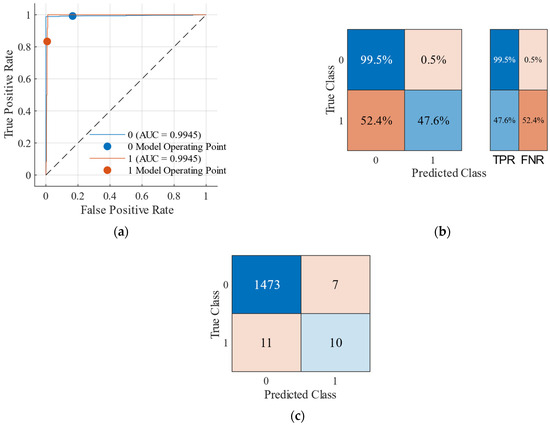

The classification accuracy curves of the ML system using the ensemble boosted trees classifier for a WT are illustrated in Figure 4. A receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve is positioned quite close to the top-left corner in Figure 4a. The values of a false negative rate (FNR) and true positive rate (TPR) in Figure 4b indicate that the classifier demonstrates excellent sensitivity and a low false-negative rate. There are 1501 observations in Figure 4c. A sufficient number of datasets are utilized to train the model in this study, enabling it to produce positive outcomes under various operating conditions. Therefore, the ensemble boosted trees classifier is selected for the active crowbar and CBFCL protection systems, and it is employed for control of the hybrid protection system.

Figure 4.

Performance evaluation of the classification model using an ensemble boosted tree: (a) receiver operating characteristic, (b) true-positive and false-negative rate comparison, and (c) distribution of sample counts.

The classification performance of different ML algorithms for the CBFCL protection system is presented in Table 5. The boosted tree algorithm has an accuracy rate of approximately 98.8% and an F1 score of around 99.39%. These algorithms in the CBFCL protection system have the best values for accuracy, TPR, recall, and F1-score. Therefore, the boosted trees algorithm is the most reliable classifier for detecting faults and identifying normal operation conditions. The Cubic SVM model has the lowest accuracy value of only 39.9%, while the fine tree and medium tree classifiers also have relatively high accuracy rates of approximately 98.3%. This shows that the kernel parameters of Cubic SVM are not chosen appropriately for the datasets.

Table 5.

Accuracy for the CBFCL protection system using various classifiers.

The inputs of ML algorithm-based regression (ML1–ML4) are selected as the stator current components (id and iq) due to their strong influence on the dynamic behavior of both an MSC and GSC during normal and fault operation conditions. In this study, the regression neural network model for the ML1 algorithm of the MSC control is chosen due to the fact that it had the lowest RMSE value. The training dataset used in this study is generated from detailed time–domain simulations of MATLAB 2024b/Simulink, which is the PMSG-based WECS under a wide range of normal and fault operation conditions. The dataset contains 1501 samples with each representing the instantaneous electrical and mechanical characteristics of the WECS-based PMSG during normal and fault operation conditions. The dataset is partitioned into 70% training, 15% validation, and 15% testing sets. Before training, all variables are processed using min–max normalization to eliminate scale imbalance. Furthermore, the interquartile range approach is used to eliminate outliers.

The different regression mode results for the MSC control are presented in Table 6. The root mean square error (RMSE) value of Gaussian exponential GPR is 0.0075355, and the RMSE value of ensemble bagged trees is 0.0077577. These values signify that the learning process is effective. On the other hand, the RMSE value of Cubic SVM is 0.31355, representing the highest RMSE value. This value indicates that the learning process is not successful. According to the results in Table 6, the neural network trilayered model has the lowest RMSE and mean square error (MSE) values, and it has the highest R2 values. Therefore, the neural network trilayered model can model the nonlinear relationships between its variables with high accuracy and demonstrates the best performance. The neural network trilayered model for the MSC control system is selected in this study. On the other hand, SVM regression is selected for the GSC controller because it has the best results.

Table 6.

The different regression mode results for the MSC control.

5.1. Scenario 1

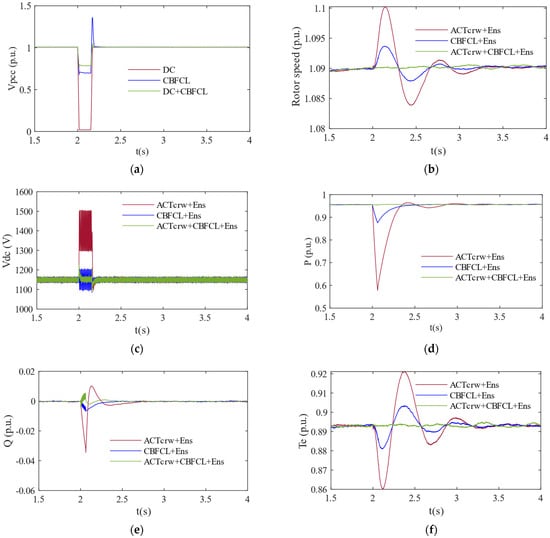

Figure 5 illustrates the dynamic responses of a 1.5 MVA WT-based PMSG system during a three-phase symmetrical grid fault, employing ACTcrw, CBFCL, and ACTcrw + CBFCL. Each protection method employs the ensemble boosted trees algorithm separately, referred to as ACTcrw-based Ens, CBFCL-based Ens, and ACTcrw + CBFCL-based Ens, respectively. The fault lasts for 150 ms in this study. A three-phase symmetrical grid fault is introduced at t = 2.0 s and is cleared at t = 2.15 s.

Figure 5.

Time–domain behavior of a 1.5 MVA wind turbine-based PMSG system during a three-phase symmetrical grid fault. (a) PCC voltage waveform, (b) rotor speed, (c) DC-link voltage, (d) active power response, (e) reactive power response, and (f) electromagnetic torque dynamics.

Figure 5a demonstrates the voltage (p.u.) change at a PCC. A PCC voltage value drops to approximately 0.0193 p.u. with ACTcrw protection during a three-phase fault. A PCC voltage value drops to approximately 0.7824 p.u. with hybrid protection based on ACTcrw + CBFCL. The hybrid protection technique restores the voltage to its nominal value more rapidly. Figure 5b illustrates the rotor speed change. Rotor speed value is 1.09 p.u. during normal operation. A rotor speed with protection-based ACTcrw varied between 1.1 and 1.083 p.u, whereas the rotor speed with CBFCL remained between 1.093 and 1.088 p.u during the grid fault. The hybrid protection technique exhibits a more stable voltage amplitude within 1.09 p.u. compared to both ACTcrw and CBFCL. After a grid fault, a rotor speed with a hybrid protection system quickly reaches its nominal value, while the rotor speed with the protection-based ACTcrw continues to fluctuate. This demonstrates that hybrid protection significantly improves mechanical stability. A DC-link voltage variation is illustrated in Figure 5c. A Vdc value employing the hybrid protection method fluctuates between 1218 V and 1018 V during grid fault, and a Vdc value fluctuates between 1505 V and 1296 V using the ACTcrw protection method. A Vdc value of the ACTcrw protection method exhibits significant fluctuations during a grid fault. In contrast, a Vdc value of a hybrid protection method remains relatively stable within the nominal range. Figure 5d illustrates the variation in active power (p). The p dip value of the ACTcrw protection method is 0.577 p.u. during a grid fault, while a p dip value of a CBFCL protection system is 0.876 p.u. A p value of a hybrid protection system is 0.955 p.u., which is the nominal value during a grid fault. Figure 5e illustrates a reactive power (Q) response. The Q value of an ACTcrw protection method is −0.034 p.u., and the Q value of a hybrid protection method is 0.005 p.u. during a grid fault. After a grid fault, the maximum positive value of Q of an ACTcrw protection method is 0.01 p.u., while the Q value of a hybrid protection system is 0 p.u., which is the nominal value. The variation in electromagnetic torque (Te) is observed in Figure 5f. The Te value using the hybrid protection method is 0.893 p.u., which is the nominal value during a grid fault, and the Te value fluctuates between 0.92 p.u. and 0.86 p.u. using the ACTcrw protection method. After a grid fault, the Te of an ACTcrw protection method exhibits significant fluctuations, while the Te of the hybrid protection method remains relatively stable within the nominal range.

5.2. Scenario 2

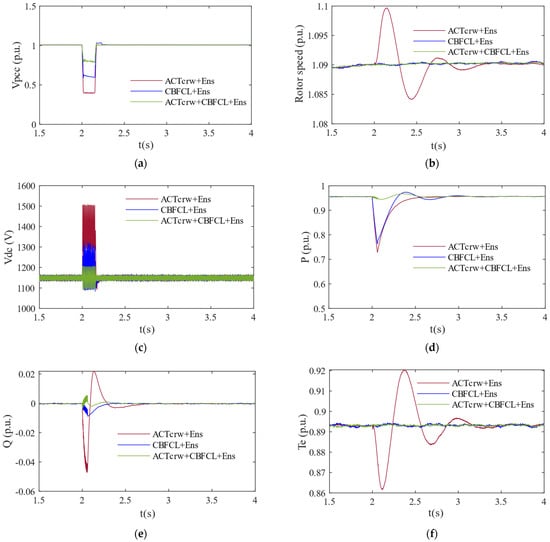

Figure 6 illustrates the dynamic responses of a 1.5 MVA WT-based PMSG system during a two-phase asymmetrical grid fault, employing ACTcrw, CBFCL, and ACTcrw + CBFCL. The fault lasts for 150 ms in this study. A two-phase asymmetrical grid fault is introduced at t = 2.0 s and is cleared at t = 2.15 s.

Figure 6.

Time–domain behavior of a 1.5 MVA wind turbine-based PMSG system during a two-phase symmetrical grid fault: (a) PCC voltage waveform, (b) rotor speed (c) DC-link voltage profile, (d) active power response, (e) reactive power response, and (f) electromagnetic torque dynamics.

The voltage (p.u.) change at the PCC is illustrated in Figure 6a. The PCC voltage value drops to approximately 0.398 p.u. hybrid protection based on ACTcrw + CBFCL. The PCC voltage value drops to approximately 0.609 p.u. with protection based on CBFCL during a two-phase grid fault. The PCC voltage value drops to approximately 0.796 p.u. with protection based on ACTcrw during a two-phase grid fault. During a two-phase asymmetrical fault, significant asymmetric drops are observed in the PCC voltage with ACTcrw. On the other hand, the hybrid controller restricts a voltage imbalance at a PCC point and keeps it near a nominal value. The rotor speed change is illustrated in Figure 6b. A rotor speed with hybrid protection remained at nominal rotor speed value, while the rotor speed with protection-based ACTcrw varied between 1.099 and 1.084 p.u. during the grid fault. The hybrid protection system maintained mechanical stability by limiting rotor speed fluctuation close to the nominal rotor speed value. The variation in Vdc value is shown in Figure 6c. The Vdc value fluctuates within 1506–1092 V using the ACTcrw protection method, and the Vdc value using the hybrid protection method fluctuates within 1203–1090 V during a grid fault. During a grid fault, the Vdc of the ACTcrw protection method exhibits significant fluctuations. In contrast, the hybrid protection method provides a controlled energy balance by keeping the Vdc value within a narrower range. The variation in the p value is illustrated in Figure 6d. A p value of a hybrid protection system is nearer to 0.955 p.u., which is a nominal value, and a p dip value of the ACTcrw protection method is 0.728 p.u. during a grid fault. The hybrid protection system distributes active power more effectively than the ACTcrw protection system. The variation in Q is illustrated in Figure 6e. A Q value of an ACTcrw protection method fluctuates between −0.047 p.u. and 0.028 p.u. In contrast, the Q value of a hybrid protection method is 0.005 p.u., which is the nominal value during a grid fault. The variation in Te is observed in Figure 6f. A Te value using a hybrid protection method is 0.893 p.u. which is the nominal value during a grid fault. In contrast, a Te value fluctuates between 0.8616 p.u. and 0.92 p.u. using the ACTcrw protection method.

5.3. Scenario 3

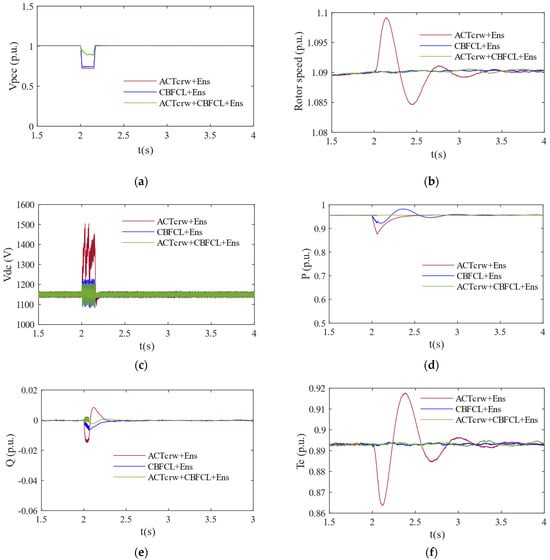

Figure 7 illustrates the dynamic responses of a 1.5 MVA WT-based PMSG system during a single-phase asymmetrical grid fault, employing ACTcrw, CBFCL, and ACTcrw + CBFCL. The fault lasts for 150 ms in this study. A single-phase asymmetrical grid fault is introduced at t = 2.0 s and is cleared at t = 2.15 s.

Figure 7.

Time–domain behavior of a 1.5MVA wind turbine-based PMSG system during a single-phase symmetrical grid fault: (a) PCC voltage waveform, (b) rotor speed, (c) DC-link voltage response, (d) active power response, (e) reactive power response, and (f) electromagnetic torque dynamics.

Figure 7a demonstrates the voltage (p.u.) change at a PCC. During a single-phase grid fault, the PCC voltage amplitude drops to 0.719 p.u. with ACTcrw protection. The PCC voltage amplitude drops to 0.741 p.u. with CBFCL protection. The PCC voltage amplitude decreases to 0.894 p.u. with hybrid protection. A PCC voltage sag with hybrid protection is more limited than with ACTcrw protection. Figure 7b shows the rotor speed change. During a single-phase grid fault, the rotor speed fluctuates between 1.099 and 1.084 p.u. with ACTcrw protection, while it remains a nominal rotor speed value under hybrid protection. Figure 7c illustrates the Vdc value change. During a single-phase grid fault, the Vdc voltage value fluctuates widely between 1502 V and 1194 V with ACTcrw protection, while it remains stable within the 1176–1122 V range under the hybrid protection method. The hybrid protection system illustrates an exceptional ability to minimize Vdc voltage fluctuations. Figure 7d demonstrates the p value change. During a single-phase grid fault, the p dip value for ACTcrw protection is 0.875 p.u., while the p value for hybrid protection stays closer to the nominal value. This results in more stable active power delivery to a power grid. A variation in Q is illustrated in Figure 7e. The Q value of an ACTcrw protection method fluctuates between −0.014 p.u. and 0.008 p.u. In contrast, the Q value of a hybrid protection method remains 0.005 p.u. during a grid fault. A variation in Te is observed in Figure 7f. The Te value using a hybrid protection method is 0.893 p.u., which is the nominal value under grid fault. In contrast, the Te value fluctuates between 0.863 p.u. and 0.917 p.u. using the ACTcrw protection method.

6. Conclusions

In this study, the FRT performance of a 1.5 MVA wind energy system based on PMSG is comparatively investigated using ACTcrw, CBFCL, and ACTcrw +CBFCL protection methods, all based on a machine learning algorithm. The PCC voltage, active power, DC-link voltage, electromagnetic torque, and rotor speed characteristics of a wind turbine system are analyzed under three-phase symmetrical, two-phase asymmetrical, and single-phase asymmetrical fault conditions.

During a single-phase grid fault, the p value for ACTcrw protection ranges from 0.85 p.u. to 1.25 p.u., while for hybrid protection, it varies between 0.95 p.u. and 1.10 p.u. The p value recovers more quickly and approaches the nominal value with the hybrid protection system. The Vdc value fluctuates between 1092 V and 1506 V under the ACTcrw protection method, while under the hybrid protection method, it varies between 1090 V and 1203 V during a two-phase asymmetrical fault. During this fault, the Vdc value of the ACTcrw protection method exhibits significant fluctuations. In contrast, the hybrid protection maintains a controlled energy balance by keeping the Vdc value within a narrower range. During a three-phase symmetrical fault, the Vdc value for the ACTcrw protection method ranges from 1296 V to 1505 V, while the Vdc value for the hybrid protection method is measured between 1018 V and 1218 V. The hybrid protection method reduces the Vdc oscillations by 25% during this fault. The ML control method has illustrated exceptional capability in accurately detecting grid faults and dynamically adjusting ACTcrw and CBFCL to protect a WT based on the PMSG system under all grid fault scenarios. The simulation results in this study demonstrate that the hybrid protection method based on an ML algorithm provides lower amplitude transient responses and quicker recovery times for both electrical and mechanical parameters compared to other protection methods.

The simulation results show that machine learning can be practically implemented for control and protection methods in wind turbine systems due to the average inference time of 0.34 ms and approximately 48 kB of memory on a TI TMS320C2000-class DSP. A TI TMS320C2000 class DSP operates well within the limitations of the standard control loops of the converter of the wind turbine.

Funding

This study was carried out without any dedicated financial support from governmental, industrial, or non-profit funding bodies.

Data Availability Statement

All data used in this study are fully provided within the main text of the article.

Conflicts of Interest

The author declares that there are no conflicts of interest related to this research.

Abbreviations

The following abbreviations are used in this manuscript:

| SVM | Support Vector-based Classification/Regression Technique |

| SPWM | Sinusoidal PWM Modulation Strategy |

| MSE | Mean Squared Error Metric |

| FNR | Rate of False–Negative Decisions |

| TPR | True Positive Identification Ratio |

| ROC | Receiver–Operating Curve |

| D-STATCOM | Distribution-Level Static Compensator |

| STATCOM | Static Synchronous Compensator |

| GSC | Converter Connected to the Grid Side |

| MSC | Machine-Side Converter |

| PMSG | Permanent-Magnet Synchronous Generator |

| WECS | Wind Energy Conversion Systems |

| FRT | Fault Ride-Through |

| ML | Machine learning |

| CBFCL | Capacitive-Bridge-Type Fault Current Limiter |

References

- Palanimuthu, K.; Mayilsamy, G.; Lee, S.R.; Jung, S.Y.; Joo, Y.H. Fault Ride-Through for PMVG-Based Wind Turbine System Using Coordinated Active and Reactive Power Control Strategy. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2023, 70, 5797–5807. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zheng, Z.; Xie, Q.; Huang, C.; Xiao, X.; Li, C. Superconducting Technology Based Fault Ride Through Strategy for PMSG-Based Wind Turbine Generator: A Comprehensive Review. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2021, 31, 5403106. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dai, T.; Xiao, X.; Xie, Q.; Ren, J.; Zheng, Z. Hybrid Grid-Forming and Grid Following PMSG-SMES Architecture with Enhanced FRT Capability. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2024, 34, 5402304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Xiao, X.; Dai, T.; Ren, J.; Xu, B. Synchronization Stability Constrained SFCL-Based Fault Ride-Through Strategy for PMSG. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2024, 34, 5601905. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Xie, Q.; Zheng, Z.; Huang, C.; Dai, T. Coordinated Fault Ride Through Method for PMSG-Based Wind Turbine Using SFCL and Modified Control Strategy. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2021, 31, 5402805. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Kinnunen, P.; Lindh, P.; Zadorozhniuk, D.; Pyrhönen, J.; Parviainen, A. Parameter Selection Guidelines for Direct-on-Line Permanent Magnet Generators Contemplating Fault-Ride-Through Capability. IEEE Access 2022, 10, 128166–128176. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Sheng, Y.; Li, C.; Jia, H.; Liu, B.; Li, B.; Coombs, T.A. Investigation on FRT Capability of PMSG-Based Offshore Wind Farm Using the SFCL. IEEE Trans. Appl. Supercond. 2021, 31, 5604704. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ramachandran, V.; Pitchaimuthu, R.; Selvan, M.P. Systematized Active Power Control of PMSG-Based Wind-Driven Generators. IEEE Syst. J. 2020, 14, 708–717. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, Q.; He, J.; Xu, Y.; Hong, Z.; Chen, Y.; Strunz, K. Average-Value Modeling of Direct-Driven PMSG-Based Wind Energy Conversion Systems. IEEE Trans. Energy Convers. 2022, 37, 264–273. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Peng, Y.; Li, Y.; Lee, K.Y.; Tan, Y.; Cao, Y.; Wen, M. Coordinated Control Strategy of PMSG and Cascaded H-Bridge STATCOM in Dispersed Wind Farm for Suppressing Unbalanced Grid Voltage. IEEE Trans. Sustain. Energy 2021, 12, 349–359. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Ranjan, S.; Das, D.C.; Latif, A.; Sinha, N.; Hussain, S.M.S.; Ustun, T.S. Maiden Voltage Control Analysis of Hybrid Power System with Dynamic Voltage Restorer. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 60531–60542. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Silva, T.C.; Antunes, F.A.S.; Teixeira, J.C.; Contreras, R.C. Correlation Between Wind Turbine Failures and Environmental Conditions: A Machine Learning Approach. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 50043–50058. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Aslam, L.; Zou, R.; Awan, E.S.; Hussain, S.S.; Asim, M.; Chelloug, S.A. Dynamic Optimization of Recurrent Networks for Wind Speed Prediction on Edge Devices. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 114520–114541. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Huang, C.L.; Wu, Y.K.; Phan, Q.T.; Tsai, C.C.; Hong, J.S. Enhancing Wind Power Forecasts via Bias Correction Technologies for Numerical Weather Prediction Model. IEEE Trans. Ind. Appl. 2025, 61, 5406–5419. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Chen, T.; Yang, C.; Xiao, Y.; Yan, C.; Lei, M.; Photong, C. Energy-Efficient Wind Turbine Operation via Multi-Class Blade Icing Recognition Using Mutual-Information Feature Selection and Ensemble Methods. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 156008–156020. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Li, X.; Cheng, C.; Peng, Z. Frequency-Assisted Contrastive Learning With Cyclic Fine-Tuning for Rotating Machinery Fault Diagnosis Under Limited Labeled Data. IEEE Trans. Inst. Meas. 2025, 74, 3510611. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Zhang, X.Y.; Yu, H.; Zheng, X.; Wang, H.; Mu, C.; Guo, P. Hybrid Deep Reinforcement Learning for UAV Inspection in Large-Scale Wind Farms: Deployment and Routing Optimization. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 2025, 21, 9011–9021. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Dheda, D.; Albertyn, J.; Adetunji, K.; Liu, Z.; Mahfouz, A.M.A.; Cheng, L. Techno-Economic, Environmental, and Social Multi-Objective Optimization of a Grid-Connected Hybrid Renewable Energy System Using Metaheuristic Algorithms. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 164859–164882. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Grataloup, A.; Jonas, S.; Meyer, A. Wind Turbine Condition Monitoring Based on Intra- and Inter-Farm Federated Learning. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 146617–146629. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Malik, H.; Almutairi, A. Modified Fuzzy-Q-Learning (MFQL)-Based Mechanical Fault Diagnosis for Direct-Drive Wind Turbines Using Electrical Signals. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 52569–52579. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Shahbaz, N.; Chen, Y.; Liang, F.; Zhang, S.; Zhao, S.; Ma, Y. Diagnosis of Demagnetization Faults in PMSGs Based on Performance Evaluation of Machine Learning Algorithms Through Flux and Current Signals. IEEE Trans. Instr. Meas. 2025, 74, 2505110. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Minaz, M.R.; Akcan, E. An Effective Method for Detection of Demagnetization Fault in Axial Flux Coreless PMSG With Texture-Based Analysis. IEEE Access 2021, 9, 17438–17449. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Alsafran, A.S.; Ullah, S.; Ullah, A.; Hafeez, G.; Babar, M.Z.; Alghamdi, B. A Robust Fractional-Order Nonsingular Terminal Sliding Mode Control With Deep Learning-Based Lie Derivative Estimation for Maximum Power Point Tracking in Wind Turbine. IEEE Access 2025, 13, 127423–127435. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hadi, F.M.A.; Aly, H.H.; Little, T. Harmonics Forecasting of Wind and Solar Hybrid Model Based on Deep Machine Learning. IEEE Access 2023, 11, 100438–100457. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hernandez, C.; Campos, B.; Diaz, L.; Lara, J.; Arjona, M.A. Electromagnetic Design Optimization of a PMSG Using a Deep Neural Network Approach. IEEE Trans. Magn. 2025, 61, 8100304. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Singh, B.; Niwas, R.; Dube, S.K. Load Leveling and Voltage Control of Permanent Magnet Synchronous Generator-Based DG Set for Standalone Supply System. IEEE Trans. Ind. Inf. 2014, 10, 2034–2043. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Suni, J.C.P.; Paredes, M.G.S.P.; Paula, M.V.; Filho, E.R.; Velasco, J.A.M. Fault Section Identification in Distribution Networks with DFIG and PMSG Generators Using Current Transients. IEEE Lat. Am. Trans. 2025, 23, 487–496. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Hong, C.M.; Chen, C.H.; Tu, C.S. Maximum power point tracking based control algorithm for PMSG wind generation system without mechanical sensors. Energy Convers. Manag. 2013, 69, 58–67. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Yao, J.; Yu, M.; Gao, W.; Zeng, X. Frequency regulation control strategy for PMSG wind-power generation system with flywheel energy storage unit. IET Renew. Power Gener. 2017, 11, 1082–1093. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Eltamaly, A.M.; Farh, H.M. Maximum power extraction from wind energy system based on fuzzy logic control. Electr. Power Syst. Res. 2013, 97, 144–150. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Prado, A.C.; Alepuz, S.; Bordonau, J.; Cortes, P.; Rodriguez, J. Predictive control of a back-to-back NPC converter-based wind power system. IEEE Trans. Ind. Electron. 2016, 63, 4615–4627. [Google Scholar] [CrossRef]

- Gencer, A. Analysis of fault ride through capability improvement of the permanent magnet synchronous generator based on WT using a BFCL. In Proceedings of the 2019 1st Global Power, Energy and Communication Conference (GPECOM), Nevsehir, Turkey, 12–15 June 2019; pp. 353–357. [Google Scholar]

Disclaimer/Publisher’s Note: The statements, opinions and data contained in all publications are solely those of the individual author(s) and contributor(s) and not of MDPI and/or the editor(s). MDPI and/or the editor(s) disclaim responsibility for any injury to people or property resulting from any ideas, methods, instructions or products referred to in the content. |

© 2025 by the author. Licensee MDPI, Basel, Switzerland. This article is an open access article distributed under the terms and conditions of the Creative Commons Attribution (CC BY) license.